There are plenty of moral reasons to be vaccinated – but that doesn’t mean it’s your ethical duty

Director of the Master of Bioethics degree program at the Berman Institute of Bioethics, Johns Hopkins University

Disclosure statement

Travis N. Rieder does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

With the news that all U.S. adults are now eligible to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, the holy grail of infectious disease mitigation – herd immunity – feels tantalizingly close. If enough people take the vaccine, likely at least 70% of the population, disease prevalence will slowly decline and most of us will safely get back to normal. But if not enough people get vaccinated, COVID-19 could stick around indefinitely.

The urgency of reaching that milestone has led some to claim that individuals have a civic duty or moral obligation to get vaccinated.

As a moral philosopher who has written on the nature of obligation in other contexts, I want to explore how the seemingly straightforward ethics of vaccine choice is in fact rather complex.

The simple argument

The discussion of whether or not one should take the COVID-19 vaccine is often framed in terms of individual self-interest: The benefits outweigh the risk, so you should do it.

That’s not a moral argument.

Most people likely believe that others have wide latitude in determining how they care for their own health, so it can be permissible to engage in risky activities – such as motorcycling or base jumping – even when it’s not in one’s interest. Whether one should get vaccinated, however, is a moral issue because it affects others, and in a couple of ways.

First, effective vaccines are expected to decrease not only rates of infection but also rates of virus transmission . This means that getting the vaccine can protect others from you and contribute to the population reaching herd immunity.

Second, high disease prevalence allows for more genetic mutation of a virus, which is how new variants arise. If enough people aren’t vaccinated quickly, new variants may develop that are more infectious, are more dangerous or evade current vaccines.

The straightforward ethical argument, then, says: Getting vaccinated isn’t just about you. Yes, you have the right to take risks with your own safety. But as the British philosopher John Stuart Mill argued in 1859, your freedom is limited by the harm it could do to others. In other words, you do not have the right to risk other people’s health, and so you are obligated to do your part to reduce infection and transmission rates.

It’s a plausible argument. But the case is rather more complicated.

Individual action, collective good

The first problem with the argument above is that it moves from the claim that “My freedom is limited by the harm it would cause others” to the much more contentious claim that “My freedom is limited by very small contributions my action might make to large, collective harms.”

Refusing to be vaccinated does not violate Mill’s harm principle , as it does not directly threaten some particular other with significant harm. Rather, it contributes a very small amount to a large, collective harm.

Since no individual vaccination achieves herd immunity or eliminates genetic mutation, it is natural to wonder: Could we really have a duty to make such a very small contribution to the collective good?

A version of this problem has been well explored in the climate ethics literature, since individual actions are also inadequate to address the threat of climate change. In that context, a well-known paper argues that the answer is “no”: There is simply no duty to act if your action won’t make a meaningful difference to the outcome.

Others, however, have explored a variety of ways to rescue the idea that individuals must not contribute to collective harms.

One strategy is to argue that small individual actions may actually make a difference to large collective effects, even if it’s difficult to see.

For instance: Although it appears that an individual getting vaccinated doesn’t make a significant difference to the outcome, perhaps that is just the result of uncareful moral mathematics. One’s chance of saving a life by reducing infection or transmission is very small, but saving a life is very valuable. The expected value of the outcome, then, is still high enough to justify taking it to be a moral requirement.

Another strategy concedes that individual actions don’t make a meaningful difference to large, structural problems, but this doesn’t mean morality must be silent with regard to those actions. Considerations of fairness , virtue and integrity all might recommend taking individual action toward a collective goal – even if that action did not by itself make a difference.

In addition, these and other considerations can provide reasons to act , even if they don’t imply an obligation to act.

The contours of obligation

There is yet another challenge in justifying an obligation to get vaccinated, which has to do with the very nature of obligations.

Obligations are requirements on actions, and, as such, those actions often seem demandable by members of the moral community. If a person is obligated to donate to charity, then other members of the community have the moral standing to demand a percentage of their income. That money is owed to others.

The relevant question here, then, is: Are there moral grounds to demand another person get vaccinated?

Philosopher Margaret Little has argued that very intimate actions, such as sex and gestation – the continuation of a pregnancy – are not demandable. In my own work, I’ve suggested that this is also true for deciding how to form a family – for example, adopting a child versus procreating. The intimacy of the actions, I argue, make it the case that no one is entitled to them. Someone can ask you for sex, and there are good reasons to adopt rather than procreate; but no one in the community has the moral standing to demand that you do either. These sorts of examples suggest that particularly intimate actions are not the appropriate targets of obligation.

Is getting vaccinated intimate? While it may not appear so at first blush, it involves having a substance injected into your body, which is a form of bodily intimacy. It requires allowing another to puncture the barrier between your body and the world. In fact, most medical procedures are the sort of thing that it seems inappropriate to demand of someone, as individuals have unilateral moral authority over what happens to their bodies.

The argument presented here objects to intimate duties because they seem too invasive. However, even if members of the moral community don’t have the standing to demand that others vaccinate, they are not required to stay silent; they may ask, request or entreat, based on very good reasons. And of course, no one is required to interact with those who decline.

I am certainly not trying to convince anyone that it’s OK not to get vaccinated. Indeed, the arguments throughout indicate, I think, that there is overwhelming reason to get vaccinated. But reasons – even when overwhelming – don’t constitute a duty, and they don’t make an action demandable.

Acting as though the moral case is straightforward can be alienating to those who disagree. And minimizing the moral stakes when we ask others to have a substance injected into their body can be disrespectful. A much better way, I think, is to engage others rather than demand from them, even if the force of reason ends up clearly on one side.

[ Explore the intersection of faith, politics, arts and culture. Sign up for This Week in Religion. ]

- Vaccination

- John Stuart Mill

- Ethical question

- Everyday ethics

Biocloud Project Manager - Australian Biocommons

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Deputy Editor - Technology

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

An Overview of the Vaccine Debate

Looking at Both Sides of the Argument

There is a wealth of research demonstrating the efficacy and safety of vaccines —including how some have virtually eradicated infectious diseases that once killed millions. However, this has done little to sway those who believe that untold harms are being hidden from the American public.

The vaccine debate—including the argument as to whether vaccines are safe, effective, or could cause conditions like autism —has received a lot of attention from the media in recent years. With so much conflicting information being publicized, it can be a challenge to discern what is true and what is not. Therefore, it is important to learn the facts before making health decisions.

Claims and Controversy

Those who are part of the anti-vaccination movement include not only non-medical professionals but several scientists and healthcare providers who hold alternative views about vaccines and vaccination in general.

Some notable examples include:

- British healthcare provider Andrew Wakefield, who in 1998 published research linking the MMR vaccine and autism . That study has since been retracted, and he was later removed from the medical registry in the United Kingdom for falsifying scientific data.

- Pediatrician Bob Sears, who wrote the bestseller "The Vaccine Book: Making the Right Decision for your Child ," which suggested that many essential childhood vaccines were "optional." However, he was subsequently put on probation by the Medical Review Board of California in 2018 for alleged medical negligence and the inappropriate writing of medical exemptions for vaccinations.

- Dr. Jane M. Orient, director of the Association of American Healthcare Providers and Surgeons, who was among the leading opponents of the COVID-19 vaccine and one of the leading proponents of using hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19 during the pandemic.

These opposing views and claims, along with other information promoted by the news and social media, have led some people to question whether they know everything they need to know about vaccines.

Common Concerns Regarding Vaccines

The arguments made against vaccines are not new and have been made well before the first vaccine was developed for smallpox back in the 18th century.

The following are some of the common arguments against vaccines:

- Vaccines contain "toxic" ingredients that can lead to an assortment of chronic health conditions such as autism.

- Vaccines are a tool of "Big Pharma," in which manufacturers are willing to profit off of harm to children.

- Governments are "pharma shills," meaning they are bought off by pharmaceutical companies to hide cures or approve drugs that are not safe.

- A child’s immune system is too immature to handle vaccines , leading the immune system to become overwhelmed and trigger an array of abnormal health conditions.

- Natural immunity is best , suggesting that a natural infection that causes disease is "better" than receiving a vaccine that may cause mild side effects.

- Vaccines are not tested properly , suggesting a (highly unethical) approach in which one group of people is given a vaccine, another group is not, and both are intentionally inoculated with the same virus or bacteria.

- Infectious diseases have declined due in part to improved hygiene and sanitation , suggesting that hand-washing and other sanitary interventions are all that are needed to prevent epidemics.

- Vaccines cause the body to "shed" virus , a claim that is medically true, although the amount of shed virus is rarely enough to cause infection.

The impact of anti-vaccination claims has been profound. For example, it has led to a resurgence of measles in the United States and Europe, despite the fact that the disease was declared eliminated in the U.S. back in 2000.

Studies have suggested that the anti-vaccination movement has cast doubt on the importance of childhood vaccinations among large sectors of the population. The added burden of the COVID-19 pandemic has led to further declines in vaccination rates.

There is also concern that the same repercussions may affect COVID-19 vaccination rates—both domestically and abroad. Ultimately, vaccine rates must be high for herd immunity to be effective.

According to a study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the rate of complete recommended vaccination among babies age 5 months has declined from 66.6% in 2016 to 49.7% by May 2020. Declines in vaccination coverage were seen in other age groups as well.

Benefits of Vaccination

Of the vaccines recommended by the CDC, the benefits of immunization are seen to overwhelmingly outweigh the potential risks. While there are some people who may need to avoid certain vaccines due to underlying health conditions, the vast majority can do so safely.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, there are five important reasons why your child should get the recommended vaccines:

- Immunizations can save your child’s life . Consider that polio once killed up to 30% of those who developed paralytic symptoms. Due to polio vaccination, the disease is no longer a public health concern in the United States.

- Vaccination is very safe and effective . Injection site pain and mild, flu-like symptoms may occur with vaccine shots. However, serious side effects , such as a severe allergic reaction, are very rare.

- Immunization protects others . Because respiratory viruses can spread easily among children, getting your child vaccinated not only protects your child but prevents the further spread of disease.

- Immunizations can save you time and money . According to the non-profit Borgen Project, the average cost of a measles vaccination around the world is roughly $1.76, whereas the average cost of treating measles is $307. In the end, the cost of prevention is invariably smaller than the cost of treatment.

- Immunization protects future generations . Smallpox vaccinations have led to the eradication of smallpox . Rubella (German measles) vaccinations have helped eliminate birth defects caused by infection of pregnant mothers in the developed world. With persistence and increased community uptake, measles could one day be declared eliminated (again) as well.

A Word From Verywell

If you have any questions or concerns about vaccinations, do not hesitate to speak with your healthcare provider or your child's pediatrician.

If a vaccine on the immunization schedule has been missed, speak to a healthcare provider before seeking the vaccination on your own (such as at a pharmacy or clinic). In some cases, additional doses may be needed.

Vaccines Healthcare Provider Discussion Guide

Get our printable guide for your next healthcare provider's appointment to help you ask the right questions.

Sign up for our Health Tip of the Day newsletter, and receive daily tips that will help you live your healthiest life.

Thank you, {{form.email}}, for signing up.

There was an error. Please try again.

Eggerton L. Lancet retracts 12-year-old article linking autism to MMR vaccines . CMAJ . 2010 Mar 9; 182(4):e199-200. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-3179

Park A. Doctor behind vaccine-autism link loses license . Time .

Offit PA, Moser CA. The problem with Dr Bob's alternative vaccine schedule . Pediatrics. 2009 Jan;123 (1):e164-e169. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2189

Before the Medical Board of California, Department of Consumer Affairs, State of California. In the Matter of the Accusation Against Robert William Sears, M.D., Case No. 800-2015-012268 .

Stolberg SG. Anti-vaccine doctor has been invited to testify before Senate committee . The New York Times.

Wolfe RM, Sharp LK. Anti-vaccinationists past and present . BMJ. 2002;325(7361):430-2. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7361.430

Agley J, Xiao Y. Misinformation about COVID-19: Evidence for differential latent profiles and a strong association with trust in science . BMC Public Health. 2021;21:89. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-10103-x

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles history .

Hussain A, Ali S, Ahmed M, Hussain S. The anti-vaccination movement: a regression in modern medicine . Cureus . 2018;10(7): e2919. doi:10.7759/cureus.2919

Bramer CA, Kimmins LM, Swanson R, et al. Decline in child vaccination coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic — Michigan Care Improvement Registry, May 2016–May 2020 . MMWR. 2020 May;69(20):630-1. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6920e1

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Why vaccinate .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Poliomyelitis .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Making the vaccine decision .

Borgen Project. What is the cost of measles in the developed world? .

By Vincent Iannelli, MD Vincent Iannelli, MD, is a board-certified pediatrician and fellow of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Dr. Iannelli has cared for children for more than 20 years.

Opinion: Why COVID-19 Vaccines Should Not Be Required for All Americans

- Previous: Intro: Is It Time to Require COVID-19 Vaccines?

- Next: Yes, Nobody Has the Right to Infect Others

Should the COVID-19 Vaccine Be Required for All Americans?

As covid-19 vaccine mandates spark controversy, two public health experts debate blanket requirements..

Editor’s note: This set of commentaries was originally published in 2021. It has been republished as part of The Forum, a U.S. News series that examines multiple viewpoints on key issues. The new versions include changes to headlines and some minor text updates.

Once again, coronavirus cases are climbing nationwide. Primarily among the unvaccinated. Some 90 million eligible Americans still haven't gotten their first dose. Fueled by the highly contagious delta variant coupled with factors like vaccine hesitancy, fresh viral surges are causing renewed concern.

Vaccine mandates are sparking fierce controversy around the world. Recently President Biden announced new vaccine requirements for federal civilian workers, comprising more than 2 million Americans. Because his plan relies on the honor system – not proof of vaccination – some experts fear these steps will not be enough to curb the spread. This week, New York City went further, becoming the first major city in the country to require proof of vaccination to enter many indoor public spaces, like gyms and restaurants.

Michael Ciaglo | Getty Images

A health worker holds a dose of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine in Aurora, Colorado.

In this edition of The Forum, a U.S. News series examining opinions about key issues, two prominent public health doctors explore the question of whether all Americans should now be required to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

America 2024

Dr. Marty Makary: I’m pro-vaccine but blanket requirements outside of health care go too far.

COVID-19 vaccine mandates have become a hotly contested issue, as coronavirus cases and hospitalizations rebound nationwide, driven by the highly contagious delta variant and unswerving vaccine hesitancy. New York City will soon be the first major U.S. city to require proof of vaccination to enter restaurants, gyms and other indoor public spaces. Dr. Marty Makary, a professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and editor in chief of MedPage Today, argues that mandating vaccines for "every living, walking American" is, as of now, not well-supported by science. Moreover Makary, author of "The Price We Pay: What Broke American Health Care—and How to Fix It," has concerns about the two-dose vaccine regimen for young people.

As told to Lindsay Lyon as part of The Forum, a U.S. News series examining opinions about key issues. Responses have been edited for length and clarity.

U.S. News: Should all Americans be required to get the COVID-19 vaccine?

Dr. Marty Makary: No. As a physician with a lot of experience dealing with patients who don't follow what we ask them to do, I believe you win more bees with honey than fire.

The vaccines are so good at protecting against death from COVID-19 that those who are immune can feel good about living life without having to worry about becoming severely ill. Vaccines downgrade the infection to a mild seasonal virus – one we must learn to live with for years to come.

Scott Eisen | Getty Images

Anti-vaccine activists protest in front of the Massachusetts State House in Boston, Massachusetts.

Those who choose not to get vaccinated are making a poor health decision at their own individual risk. They pose no public health threat to those already immune. Would we be so stern toward people making similar or worse health choices to smoke, drink alcohol or not wear a helmet when riding a bike? Over 85,000 Americans die annually from alcohol, yet we don't have the same public health fervor or requirements to save those lives. Let's encourage vaccination rather than activate the personal liberty culture wars that result in people becoming more entrenched in their opposition.

The notion that we have to vaccinate every living, walking American – and eventually every newborn – in order to control the pandemic is based on the false assumption that the risk of dying from COVID-19 is equally distributed in the population. It's not. We have always known that it's very hard for the virus to hurt someone who is young and healthy. And that's still the case. While vaccine requirements for health care workers make sense, we would never extend those requirements outside of health care for, say, the flu shot. We'd simply state to the public: Those who avoid the flu shot do so at their own risk.

Also: Some people already have ' natural immunity ' – that is, immunity from prior COVID infection. During every month of this pandemic, I've had debates with other public researchers about the effectiveness and durability of natural immunity. I've been told that natural immunity could fall off a cliff, rendering people susceptible to infection. But here we are now, over a year and a half into the clinical experience of observing patients who were infected, and natural immunity is effective and going strong. And that's because with natural immunity, the body develops antibodies to the entire surface of the virus, not just a spike protein constructed from a vaccine. The power of natural immunity was recently affirmed in an Israeli study , which found a 6.7 times greater level of protection among those with natural immunity vs. those with vaccinated immunity.

Requiring the vaccine in people who are already immune with natural immunity has no scientific support. While vaccinating those people may be beneficial – and it's a reasonable hypothesis that vaccination may bolster the longevity of their immunity – to argue dogmatically that they must get vaccinated has zero clinical outcome data to back it. As a matter of fact, we have data to the contrary: A Cleveland Clinic study found that vaccinating people with natural immunity did not add to their level of protection.

So instead of talking about the vaccinated and the unvaccinated, we should be talking about the immune and the non-immune. Immunity is something people can test for with a simple antibody test. I would never recommend that anyone intentionally acquire the infection in order to get natural immunity, but vaccine passports and proof-of-vaccine documents should recognize it.

Now, if someone does not have natural immunity from prior infection, then they should immediately go out and get the vaccine. I'm pro-vaccine. But the issue of the appropriate clinical indication of the vaccine is not an all-or-nothing phenomenon, as we frequently see in American culture and politics.

I'm perplexed at the vitriol directed at folks who are reluctant to get vaccinated. For some, the biggest driver of their hesitancy is the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which has failed to issue the long-overdue full approval of the COVID-19 vaccines due to stability testing which has nothing to do with safety.

The goal of our pandemic response should be to reduce death, illness and disability, but instead what you're seeing is a movement that has morphed from being pro-vaccine to vaccine fanaticism at all costs.

We have very strong population immunity in most parts of the U.S. – and these areas are resilient to the delta variant that's driving severe illness right now. This stems from a combination of natural immunity and vaccinated immunity. Roughly a third to half of Americans who are unvaccinated have natural immunity, based on an analysis of California residents. So it does change the outlook.

For example: One study conducted by the state of California this spring found that 38% of Californians and 45% of Los Angeles residents had natural immunity. And this was at a time when vaccine rollout was still too early to account for those numbers. So we're potentially talking about a large portion of the U.S. population who may be immune to COVID and not know it. They should be tested to find out, and we should concentrate our vaccination efforts on people who are not immune.

Right now, we do have a group of susceptible, non-immune Americans among whom the delta variant is raging. That's where we need to focus our attention. We have to work on making the vaccine more available – and easily available – to the non-immune in the U.S. That means going to them: Having walk-up vaccination appointments at routine points of American life.

When it comes to vaccinating healthy kids – and you could argue young people up to 25 – there is a case for vaccination but it's not strong. The COVID-19 death risk is clustered among kids with a comorbid condition, like obesity. Of the more than 330 COVID-19 deaths in kids under age 25, there's good preliminary data suggesting that most or nearly all appear to be in kids with a pre-existing condition. For kids with concurrent medical conditions, the case for vaccination is compelling. But for healthy kids?

The risk of hospitalization from COVID-19 in kids ages 5 to17 is 0.3 per million for the week ending July 24, 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. We also know that the risk of hospitalization after the second vaccine dose due to myocarditis , or inflammation of the heart muscle, is about 50 per million in that same age group.

It may be that the standard two-dose regimen is a dose too high and is inducing a strong inflammatory response causing these complications. A single dose of the vaccine may be highly effective in kids, as reported by Tel Aviv University . Researchers there found that one dose was 100% effective in kids ages 12 to 15. For now, until we get better data, I recommend one dose for healthy kids who have not already had COVID-19 in the past.

I'm concerned the CDC hasn't considered whether one dose of the two-dose shots would be sufficient – and safer – for young people. The agency's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has vigorously recommended the two-dose vaccine regimen for all children ages 12 and up regardless of whether kids already have immunity. I take issue with that. The data the CDC used on which to base its recommendation is incomplete at best. The agency is using the Yelp of vaccine complications as a data source: a self-reported database of vaccine complications, which haven't been fact-checked by authorities. So the agency may not be fully capturing the extent of vaccine complications from the second dose in some young people.

I wish the CDC would tell us more about the deaths of Simone Scott , 19, and Jacob Clynick , 13, both of whom died shortly after getting a second vaccine dose and developed heart inflammation. There have been 19 other deaths in youth under age 25, according to the CDC. Since the clinical trials were not powered sufficiently to detect rare events like these, I want to know more about those deaths before making blanket recommendations.

Researching these events is important when issuing broad guidance about vaccinating healthy kids, including students, who already have an infinitesimally small risk of dying from COVID-19.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Debate on mandatory COVID-19 vaccination

Since January 2020, worldwide public health has been threatened by COVID-19, for which vaccines have been adopted from December 2020.

Although vaccines demonstrate effectiveness against this disease, vaccine hesitancy reveals concerns towards short-term and long-term side effects or adverse reactions such as post-inoculation death. Mandatory vaccination is used to provide herd immunity, but is refutable due to infringement of human rights and autonomy. Furthermore, the evidence testifies that vaccination cannot guarantee prevention of infection or re-infection, resulting in public resentment against this coercive measure, whilst post-inoculation anxiety continues.

Perspective

This discussion suggests a holistic approach, involving the collective efforts of governments, medical experts and individuals, through basic preventive measures and alternative therapy to live with COVID-19 in a healthy and resourceful manner.

An abrupt pandemic

Cases of an unknown pneumonia in Wuhan were reported on December 31, 2019, following which a novel coronavirus was identified on January 7, 2020. This new virus was officially named COVID-19 (representing corona-virus-disease-2019) on February 11, 2020, by the World Health Organisation [1] . It was determined to be a public health emergency on January 30, and then a pandemic on March 11. The first imported case of this person-to-person infectious disease, even feasibly by asymptomatic carriers, was confirmed in Thailand by a Wuhan traveller on January 13, after which it spread abroad to Japan, Korea, Nepal, Malaysia, Hong Kong, the Philippines, India, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, the United Arab Emirates, the USA, France, Germany, the UK, Sweden, Spain and Russia inside of January [2] , showing its high transmissibility. Although COVID-19 causes most infected patients to experience mild or moderate respiratory illness, such as cough, fever, headache and sore throat, a growing number of life-threatening cases occupies intensive care units, which imposes unanticipated burdens on medical resources and public health systems. Such severity pressures related authorities (including governments, health institutions, research centres, medicine companies) to urgently acquire effective solutions, among which vaccines have rapidly been developed since early 2020 and the one offered by Pfizer (an American multinational bio pharmaceutical corporation) with BioNTech (a German biotech firm) was first approved for emergency use authorisation on December 2 [3] , and its Biologics License Application (BLA) for COMIRNATY® was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration on August 23, 2021, for individuals 16 years old or above [4] .

The main function of the COVID-19 vaccine serves to develop antibodies and an immune response in order to lessen infection and transmission of this virus. Scholars conceive that once a minimum of 60% [5] of the population achieved immunity, either by vaccination or having been infected, we will reach herd immunity for protecting individuals and other people around them, hopefully ending the pandemic. However, the vaccination coverage required is increasing because of mutations [6] . Also, the available vaccines can reduce severe symptoms, which will minimise complications, morbidity and mortality, and alleviate the tremendous needs of intensive care units to safeguard the healthcare system. Thus, getting vaccinated has become a public health priority; whereas prevalent vaccine hesitancy [7] , [8] on the one hand causes psychological indecision, under-vaccination and uptake delay, while on the other hand causing herd immunity to be a more remote hope. Mandatory vaccination is continually discussed to mitigate hesitation or refusal, yet this practice is controversial.

Arguments regarding compulsory and voluntary jabs

Advocates consider herd immunity to be a common good and an altruistic procedure [9] , which justifies the exercise of mandatory injections. It is not only a public health concern, but also a social issue associated with the economic and societal burdens, socioeconomic disparities and health inequalities [10] induced by this pandemic [11] . According to the fundamental principles of medical ethics, which include autonomy, non-maleficence (not harming the well-being of the patient), beneficence (promoting the well-being of the patient) and justice [12] , pressure on healthcare frontline workers is particularly harsh since they, as role models [13] , have an obligation to protect vulnerable patients [14] . Nevertheless, dissenters blame mandatory vaccination as a coercive means used to deprive individuals of freedom. In a nutshell, compulsory vaccination raises the debate between collectivism and individualism, whereas the former inclines towards social benefits and a strong sense of community while the latter focuses more upon self-concerns and autonomy.

Savulescu [15] suggests four conditions for mandatory vaccination: first, the disease is a stern threat to public health; second, the vaccines are safe and effective; third, mandatory vaccination proves a convincing cost-benefit profile compared with other alternatives; and lastly, the level of coercion is proportionate. Similarly, experts [16] propose seven principles to make rational and transparent decisions, including three basic medical ethics (justice, autonomy and harm avoidance), public trust, solidarity and reciprocity, population health maximisation, and protection of the vulnerable. These discourses, from both practical and ethical perspectives, are used to evaluate the use of coercive jabs to combat COVID-19, which has caused more than 4.3 million deaths worldwide, among 210 million confirmed cases in the first 20 months [17] , and remains ongoing.

Justice is manifested through fairly sharing the benefits, risks and costs, resulting in a defence of mandatory vaccination as part of the civic responsibility in this pandemic. Mill's harm principle [18] allows authorities to meddle with freedom and autonomy to prevent harm to others. “No jab, no pay” and “no jab, no play” tactics seem reasonable although they affect everyone from adults to children in workplace and school. Notwithstanding, opponents argue that these exercises incur financial sanctions and social exclusion, restricting individual interests and violating human rights. They persist that the principles of justice also support individuals in refusing vaccination [19] .

Religious exemption [20] , [21] is allowed when adherents show reluctance in that vaccination deviates from their belief tenets, despite the simultaneous existence of opposite and permissive views among Hindu, Protestant, Buddhist, Muslim and Jewish communities [22] . Doubts have been raised as to whether freedom of religion is acceptable [23] , and whether the issue of body integrity should be ratified to protect individual rights to decide what is done to one's own body [24] . In this sense, compulsory injection is then unfair to others who are not granted this exemption.

On the other hand, if compulsory inoculation is seen as necessary and sufficient , the decision is a more practical one: whether a shot is the single most effective vehicle, and whether it is a stand-alone method.

Is vaccination the only intervention?

Clinical data testify to the effectiveness, efficacy and safety of available COVID-19 vaccines [25] , [26] , [27] , although short-term side effects or adverse reactions have presented themselves; for instance, fever, fatigue, pain and tenderness [28] , and even worse, post-inoculation death [29] . Based on the prediction that the benefits of vaccination are greater than the risks such as COVID-related death [30] , even for cancer patients [31] , medical experts recommend vaccination to attain herd immunity. However, vaccine-hesitant people worry about possible future and long-term effects induced by the fast development of these vaccines [32] , especially for new vaccine technology such as mRNA and viral vector [33] , when developing a vaccine takes 15 years on average [34] . Such post-injection anxiety [35] has not yet received an appropriate response. Additionally, these vaccines had only obtained emergency use authorisation without full approval [36] prior to August 2021 for COMIRNATY®, for which they bypassed the animal studies used to understand the action mechanism and the ability of the virus to resist the vaccine [37] , [38] . They directly used controlled human infection with limited geographical and ethnical disparities, which affects the safety, tolerability and efficacy of the vaccine. The race for emergency use and mass production may impact long-term vaccine safety and infection decline. Therefore, vaccine antagonists perceive that vaccination is not necessarily the sole intervention for fighting this disease. They promote basic methods, involving public mask usage, which effectively curbs the spread of coronavirus when properly worn [39] , [40] ; personal hygiene behaviour [41] , [42] such as frequent hand-washing and alcohol-based hand sanitizers; physical distancing [43] , [44] (maintaining a distance of 1–2 meters from each other and avoiding crowded places); and social distancing [45] , [46] (limiting gatherings). These instruments were evidently capable before vaccine use and the vaccine is not the only way to cope with COVID-19 for protecting oneself and others around us.

Is mere vaccination sufficient?

The evidence has forced medical personnel to acknowledge that reinfection occurs among vaccinated people or patients who have recovered from COVID-19 [47] , [48] due to the decreasing durability of antibodies [49] , [50] and to incessant variants [51] . Specialists suggest a booster dose [52] , especially for vulnerable groups [53] , [54] . The facts imply that achieving herd immunity to fully prevent contagion is unrealistic [55] to protect against infection and reinfection. This undesirable outcome reflects that vaccination, as a stand-alone method, is not strong enough to prevent outbreaks. Thereupon, even fully vaccinated people need to continuously undertake basic protective measures [56] , including masking [57] , [58] , personal hygiene [59] , physical distancing [60] and social distancing [61] . Regarding healthcare workers, there is no substantial evidence to show higher risks of infection if they are provided with sufficient and proper personal protective equipment, enough rest, and adequate hospital ventilation [62] .

Coercion or voluntary shot?

Without fulfilling these factors ( necessary and sufficient ), mandatory vaccination is a gravely refutable proposition. Coercion is a top-down approach, encompassing threats, resulting in weakening trust in government and in the integrity of the medical system. A coercive measure which infringes on personal freedoms in order to protect public health may be imposed only if it can meet three conditions [63] , particularly since a vaccine is an invasive precaution: first, it must be the most effective, sole and incontestable method; second, it must be necessary; and third, it should be proportionate. The above elaboration indicates that the available vaccines are unlikely to satisfy these requirements. Moreover, the World Health Organisation [64] emphasises that mandatory vaccination is not unconditionally compulsory; rather, criminal sanctions should not be used to penalise non-compliance and shots should not be a condition of international travel by national authorities and transportation operators. A vaccine passport is a certificate, which enables vaccinated people to travel restriction-free, albeit scientific, ethical and legal challenges are encountered [65] . It not only exhibits discrimination against unvaccinated people and impedes their freedom of movement [66] , but unwelcomingly restricts domestic and international traveller flow, economic recovery, interpersonal communication, and cultural exchange.

Instead, voluntary participation can ease tensions between public interests and individual freedom because in this case individualism does not act against collectivism, in that it involves the interdependent self with shared interests [67] . The individual self is an essential component of the collective self, and these are not necessarily mutually exclusive. It simply means that an individual protects oneself before protecting the community; and taking care of oneself during this pandemic is beneficial to society. Even when vaccine-hesitant people resist the injection for fear of the unfamiliar, uncertain long-standing side effects, if they undergo proper preventive measures, they are carrying out their civic duty. In contrast, a compulsory shot ignores their fears and unreasonably pushes them to sacrifice their personal safety along physical and psychological dimensions: this is tantamount to collective bullying. Indeed, forcing them in name of civic responsibility is moral bullying. Mandatory vaccination is a presentation of misuse of governmental power, resulting not only in jeopardising solidarity, but also in expanding tensions between public health and individual health. Hence, decision-makers should be cautious about such an arguable policy.

A holistic approach

Medical experts warn that COVID-19 has become endemic and its potency is gradually lessening [68] . Preventive measures are dispensable [69] , for which governments, the medical community and individuals are collectively responsible for tackling this disease. Such a holistic approach [70] will be a long-lasting approach to living with COVID-19 [71] .

Vaccine hesitancy is not the same thing as anti-vaccination. Whereas the former presents worries about newly developed vaccines, the latter denies this pandemic per se [72] . Findings uphold that vaccination is one of a number of effective interventions, but not an exclusive one. Mandatory vaccination is likely a force that will accelerate vaccination rates; however, coercion is unlikely to be successful in promoting vaccine uptake [73] and lowering hesitancy. Aside from risk calculation and collective obligation [74] , [75] , Razai et al. [76] add confidence (importance, safety and efficacy of vaccines), complacency (perception of low risk and low disease severity), convenience (access issues dependent on the context, time and specific vaccine being offered), communications (sources of information), and context (sociodemographic characteristics, such as ethnicity, religion, occupation, social class). These conditions rely on the governmental effectiveness.

Having greater responsibilities for creating factors needed to strengthen notions of solidarity and reciprocity, official authorities must consolidate efforts to fight the pandemic. They must respect informed self-determination, personal autonomy and individual choice under the governmental role of informing, educating, recommending and providing incentives for vaccination [77] . They have to give an apolitical presentation, and pertinent measures should focus on public health and individual well-being [78] . Governments should also enhance regulatory and humanitarian elements to offer open and qualifying resources for building confidence and creating a positive perception of vaccination [79] . Simultaneously, monitoring is useful to fend off outbreaks, including rapid screening, quick testing [80] and contact-tracing [81] . Relevant departments should maintain environmental hygiene in public facilities and clinical settings [82] , [83] , [84] ; for instance, indoor ventilation [85] and ultraviolet disinfection systems [86] .

Medical veterans are accountable for disclosing transparent science-based data [87] and discreet surveillance for vaccine efficacy against mutations [88] . In addition to developing mutation-resistant vaccines, antibody medicines [89] and curative and rehabilitative treatments [90] , [91] , [92] are critical for immune enhancement, antiviral response, and anti-inflammation or immune modulation. Researchers may investigate alternative medicines to augment the horizon of prevention and cure; for example, Chinese herbs [93] , traditional herbal medicines [94] and essential oils [95] .

As for the individual aspect, people need to cultivate community health awareness [96] and should keep up with masking, personal hygiene, crowd avoidance, physical distancing [97] , and household cleaning [98] to reduce environmental risks [99] . They may also adopt diversified means to ameliorate physiological and psychological wellness [100] , [101] . Physical exercise [102] , [103] can enhance the immune system, physical and mental health, and well-being; for instance, yoga for prevention [104] and rehabilitation [105] , meditation [106] , [107] or music [108] or gardening [109] to soothe stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms and harmful emotional effects, diet and nutrition to strengthen the immune system and maintain a good mental state [110] , [111] , [112] , together with appropriate lifestyle, including sufficient sleep and rest, stopping smoking, limitation of alcohol consumption and weight control [113] .

Vaccination is an intrusive intervention; thus, safety must be its first priority. Vaccine hesitancy, in contrast to vaccine refusal, reveals personal worries about short-term and long-term side effects or adverse reactions, and post-inoculation death, particularly for vaccines, which have been developed in just a few months and are weak in building herd immunity. People have the right to protect themselves and secure their own lives, which downplays the role of individualism versus collectivism. This discussion suggests a comprehensive approach involving multi-faceted cooperation and interdisciplinary effort through governments, professional bodies and individuals through basic preventive measures and complementary therapy, to deal with physical and mental health during this pandemic.

Disclosure of interest

The author declares that she has no competing interest.

Source of funding support

Preparation of this article did not receive any funding.

Original work

This study is the author's original work. Its findings have not been published previously, and this manuscript is not being concurrently submitted elsewhere.

- Open access

- Published: 09 November 2023

To vaccinate or not to vaccinate? The interplay between pro- and against- vaccination reasons

- Marta Caserotti 1 ,

- Paolo Girardi 2 ,

- Roberta Sellaro 1 ,

- Enrico Rubaltelli 1 ,

- Alessandra Tasso 3 ,

- Lorella Lotto 1 &

- Teresa Gavaruzzi 4

BMC Public Health volume 23 , Article number: 2207 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1898 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

By mid 2023, European countries reached 75% of vaccine coverage for COVID-19 and although vaccination rates are quite high, many people are still hesitant. A plethora of studies have investigated factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, however, insufficient attention has been paid to the reasons why people get vaccinated against COVID-19. Our work aims to investigate the role of reasons in the decision to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in a representative sample of 1,689 adult Italians (March–April 2021) balanced in terms of age, gender, educational level and area of residence.

Through an online questionnaire, we asked participants to freely report up to three reasons for and against COVID-19 vaccination, and the weight each had in the decision to get vaccinated. We first investigated the role of emotional competence and COVID-19 risk perception in the generation of both reasons using regression models. Next, we studied the role that the different reasons had in the vaccination decision, considering both the intention to vaccinate (using a beta regression model) and the decision made by the participants who already had the opportunity to get vaccinated (using a logistic regression model). Finally, two different classification tree analyses were carried out to characterize profiles with a low or high willingness to get vaccinated or with a low or high probability to accept/book the vaccine.

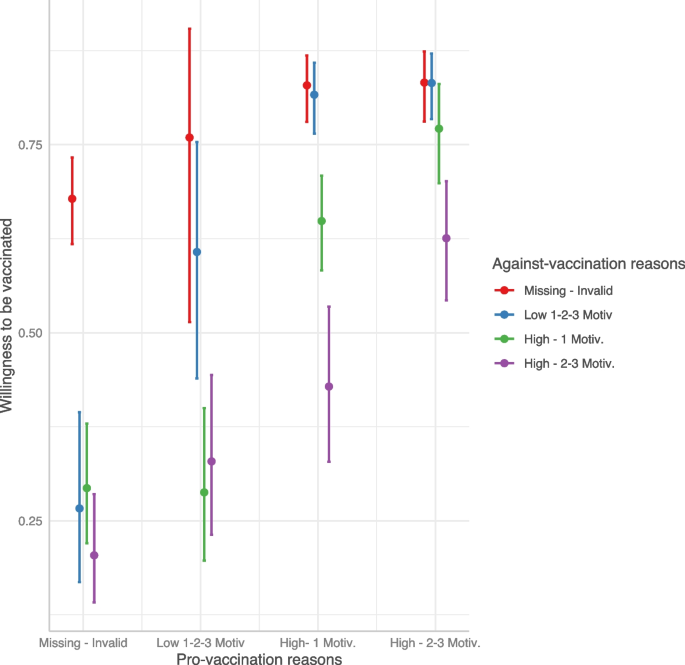

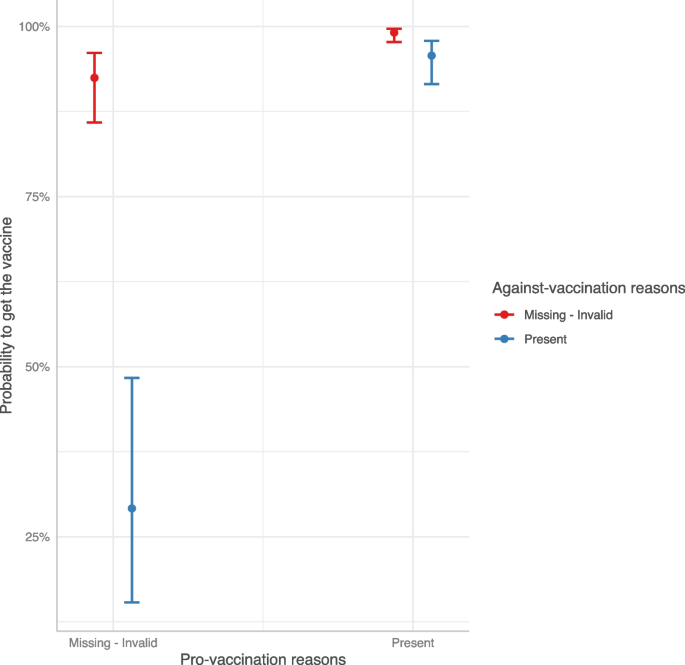

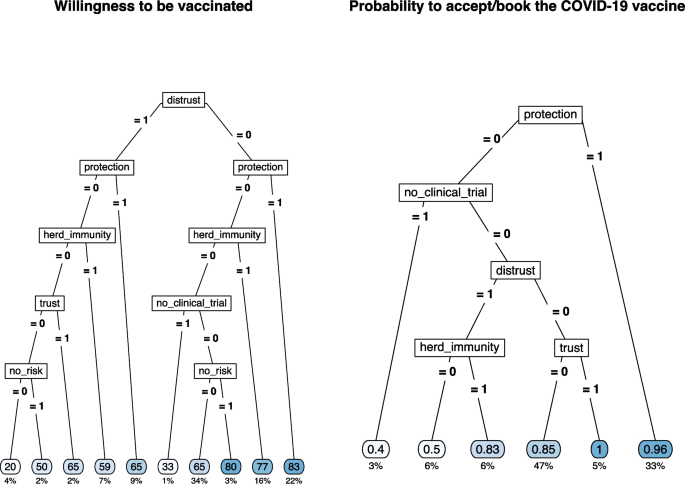

High emotional competence positively influences the generation of both reasons (ORs > 1.5), whereas high risk perception increases the generation of positive reasons (ORs > 1.4) while decreasing reasons against vaccination (OR = 0.64). As pro-reasons increase, vaccination acceptance increases, while the opposite happens as against-reasons increase (all p < 0.001). One strong reason in favor of vaccines is enough to unbalance the decision toward acceptance of vaccination, even when reasons against it are also present ( p < 0.001). Protection and absence of distrust are the reasons that mostly drive willingness to be vaccinated and acceptance of an offered vaccine.

Conclusions

Knowing the reasons that drive people’s decision about such an important choice can suggest new communication insights to reduce possible negative reactions toward vaccination and people's hesitancy. Results are discussed considering results of other national and international studies.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

By mid 2023 the European Union reached nearly 75% vaccine coverage for the primary vaccine cycle against COVID-19, with countries such as Croatia, Slovakia, and Poland falling short of 60% and others such as France, Portugal, and Italy close to 90% [ 1 ]. Although vaccination rates are, on average, quite high, many people are still hesitant. Vaccine hesitancy indicates the delay or refusal of a vaccine despite availability in vaccine services [ 2 , 3 ] and is a multidimensional construct, resulting from the interaction between individual, social, and community aspects [ 4 ]. In the last two years, a plethora of studies have investigated factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy showing, for example, that vaccine hesitancy is higher in women [ 5 , 6 ], in young people [ 5 , 7 , 8 ], in people with low education [ 8 , 9 ], low trust in authorities [ 10 , 11 ], and strong conspiracy beliefs [ 5 , 12 , 13 ]. However, to the best of our knowledge no one has investigated the interplay that pro- and against- vaccination reasons may play in the choice to get vaccinated, namely what happens when a person has both pro- and against-vaccine considerations. Trying to fill this gap in the literature, our work aims to investigate how different reasons and the importance people place on them are likely to influence the decision to get vaccinated against COVID-19.

In line with the vaccine hesitancy continuum defined by SAGE [ 2 ], while extremely pro-vax people are likely to express only reasons pro-vaccination and extremely no-vax people are likely to express only reasons against vaccination, individuals who fall between the two extreme end-points are likely to feel some doubts. This large number of people offer us the unique opportunity to assess which category of reasons (pro- vs. against- vaccination) is more impactful in driving people's vaccination decisions. As it is reasonable to imagine, among the reasons for choosing to get (or not) vaccinated some reasons are more rational, while others are more related to affect. For example, there are people who rationally recognize the importance of vaccines but at the same time are frightened by the side effects. Thus, the decision to get (or not) vaccinated is the result of a complex process, in which costs and benefits are weighed more or less rationally. Indeed, while several studies have pointed out that the decision to vaccinate is due to cognitive rather than emotional processes [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ], others have highlighted the role of affect and risk perception in the vaccination decision [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Thus, the intention to accept the vaccine is driven by emotional and affective feelings as much as by cognitive and rational judgments. Particular attention to what people feel and think about vaccine-preventable diseases and vaccination in general is paid in the model developed by the “Measuring Behavioral and Social Drivers of Vaccination” (BeSD), a global group of experts established by the World Health Organization [ 21 ]. This model encompasses two groups of proximal antecedents of vaccination, namely, what people think and feel (e.g., perceived risk, worry, confidence, trust and safety concerns) and social processes (e.g., provider recommendation, social norms and rumors). Antecedents affect vaccination motivation (i.e., vaccination readiness, willingness, intention, hesitancy), which can then be strengthened or weakened by practical issues (such as vaccine availability, convenience and cost but also requirements and incentives), resulting in acceptance, delay or refusal of vaccination (vaccination behavior).

Although some studies have considered whether the cognitive or affective component has greater weight in determining the intention to vaccinate, no one, to the best of our knowledge, has studied the interplay between pro- and against- vaccination reasons, nor the weight these have in the choice to vaccinate. In addition to the drivers already studied in the literature [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 11 , 12 ], we believe that the focus on this interaction may be relevant to better understand the complex phenomena related to vaccine hesitancy. Few recent studies have attempted to investigate the complexity of vaccination choice by studying the reasons why people choose to get (or not) vaccinated against COVID-19. Fieselmann and colleagues [ 22 ] highlighted that among the reasons that reduce adherence to vaccination are a low perception of its benefits, a low perception of the risk of contracting COVID-19, health concerns, lack of information, distrust of the system, and spiritual or religious reasons. Another study, instead, shed light on the reasons that encourage hesitant people to consider vaccination, such as protecting themselves, their family, friends and community from COVID-19, and being able to return to normal life [ 23 ].

In the present study we asked the participants to spontaneously come up with their own reasons to get (or not) vaccinated, without limiting or influencing them with a set of predefined options to choose from, thus aiming to obtain more genuine answers that may better capture the intuitive aspect of people’s opinions (for a similar reasoning see [ 24 ]). The procedure we used has been implemented by Moore et al. [ 23 ], the only study, as far as we know, that asked for reasons with an open-ended question. Critically, in their study, participants were asked to report only reasons in favor of vaccination (e.g., "What are your reasons for getting the COVID-19 vaccine?"), excluding reasons against. By contrast, we asked participants to freely report up to three reasons in favor and up to three reasons against COVID-19 vaccination and to rate on a 5-point Likert scale their weight in the decision about getting (or not) vaccinated.

From a theoretical point of view, the reasons pro- and against vaccination may be seen within the framework of prospect theory [ 25 , 26 ] which suggests that people evaluate the outcome of a choice based on a reference point, against which losses and gains are determined: the former below this point, the latter above this point. Importantly, especially in this specific context, losses and negative consequences are weighted more than gains and benefits, making us hypothesize that if a person has one reason for and one reason against the vaccine, which are of equal importance, they will more likely lean toward choosing not to vaccinate. Consistently, it is known that negative experiences have a greater impact than neutral or positive ones (i.e., the negativity bias [ 27 ]).

Besides delving into the reasons that may influence the choice to get (or not) vaccinated, it would be interesting to also look at the individual differences that may determine the reporting of pro- and against- vaccination reasons and their valence. In this regard, the literature suggests that risk perception and emotion regulation can both have a great impact in the decision to get vaccinated. For instance, studies conducted during H1N1 influenza have shown that perception of disease-related risk is one of the strongest predictors of vaccine adherence [ 28 , 29 ]. Additional insights have been provided by more recent studies investigating the role of COVID-19 risk perception in the decision to get vaccinated against COVID-19. Viswanath and colleagues [ 30 ] showed that people are more willing to vaccinate themselves and those under their care to the extent to which they feel more vulnerable to COVID-19 and rate the consequences of a possible infection as severe. Such a relationship between COVID-19 risk perception and intention to vaccinate was confirmed by another study using a cross-sectional design, which focused on the early months of the pandemic [ 31 ]. This study also examined how risk perception changed during the pandemic phases and showed that during the lockdown, compared to the pre-lockdown phase, also those who reported some hesitancy were more likely to get vaccinated when they perceived a strong COVID-19 risk.

With regard to emotion regulation, the literature suggests that people react differently to affective stimuli [ 32 ] and that their decisions are influenced by their abilities to regulate emotions [ 33 , 34 ]. Recent works investigating the relationship between hesitancy in pediatric vaccinations and the emotional load associated with vaccinations, have shown that a negative affective reaction is one of the factors leading to lower vaccine uptake [ 35 , 36 ]. Specifically, Gavaruzzi and colleagues [ 36 ] showed that concerns about vaccine safety and extreme views against vaccines are associated with vaccine refusal. Interestingly, they also showed that parents' intrapersonal emotional competences, i.e., their ability to manage, identify, and recognize their own emotions, is critical to vaccine acceptance for their children. Therefore, in our study we measured people's risk perception and emotional competencies to assess their possible role in the production of reasons in favor and against vaccination.

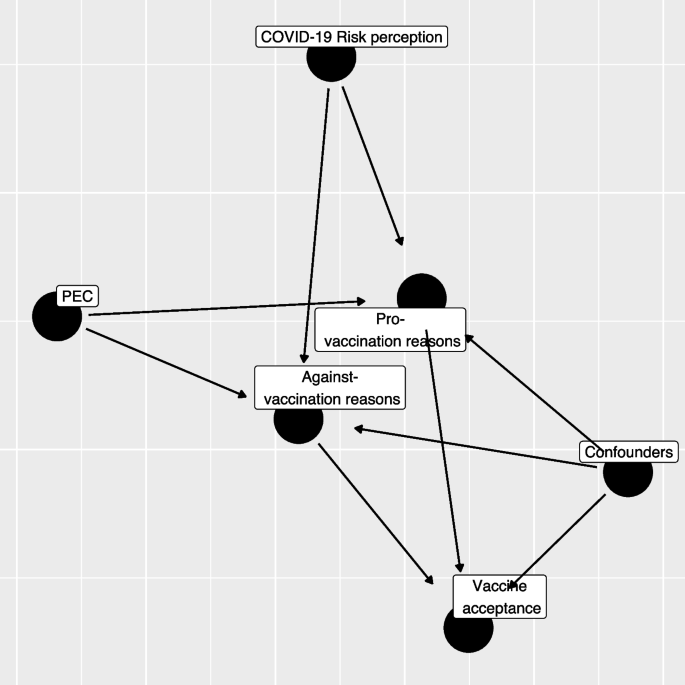

As described in Fig. 1 , the relationship between different domains of interest can be hierarchically structured, using a directed acyclic graph, starting from the risk perception and emotion regulation, to the generation of pro- and against- vaccination reasons and their valence, and finally to the vaccination willingness/adherence. With respect to the mentioned structure, we are interested to investigate the following research hypotheses:

The number and weight associated with reasons pro- and against-vaccination should be influenced by individual differences in the ability to regulate emotions;

The number and weight associated with pro-vaccination reasons should be influenced by individual differences in COVID-19 risk perception;

A higher number of strong (i.e., with high weight) reasons pro- (vs. against-) vaccination should correspond to a more (vs. less) likelihood to accept the vaccination.

Generating an equal number of reasons in favor and against vaccination should lead to a weaker likelihood to accept the vaccination.

Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) between variables considered in the study (PEC: Short Profile of Emotional Competence scale)

As we conducted the study between March and April 2021, a time when vaccinations were being progressively rolled out, we decided to consider the role of personal reasons on both the intention to get vaccinated (for those who had not yet had the opportunity to get vaccinated) and the choice already made (e.g., vaccine received or booked vs. refused).

Finally, through a non-parametric classification analysis, we will explore how specific pro- and against-vaccination reasons impact the decision to get (or not) vaccinated. Specifically, we will investigate the role that different categories of reasons play in the choice to vaccinate.

Participants

Data collection was commissioned to a survey and market research agency (Demetra Opinions.net), with the aim of securing a representative sample of the adult (+ 18) Italian population, estimated at 49.8 million [ 37 ]. The sample was balanced in terms of age, gender, educational level (middle school or lower, high school, degree or higher), and area of residence (North, Center, South, and Islands). The agency distributed via email the survey link to its panelists, who freely decided whether to participate in the study in exchange for financial compensation. Out of 1,833 participants who started the questionnaire, 77 (4%) were excluded because they did not complete the survey and 16 (0.9%) were excluded since they reported offensive content in open-ended questions. Finally, 124 (6.8%) participants were excluded because of missing information. Thus, the final sample consisted of 1,689 participants. The project was approved by the ethical committee for Psychology Research of the University of Padova (Italy), with protocol number 3911/2020 and informed consent was obtained for all participants.

We developed an ad-hoc questionnaire including a series of open-ended and closed questions (see Additional file 1 : Appendix 2 for the full material). We first investigated the vaccination status of the participants, asking whether they already had received at least the first dose, whether they had booked it or were still ineligible, and finally whether they had refused the vaccination. Those not yet eligible were asked to rate how likely they would be to get vaccinated at the time they responded (0 = Not at all likely , 100 = Extremely likely ). Then, we asked participants to report a maximum of three reasons both in favor of the COVID-19 vaccine and against it (in counterbalanced order) and to rate how much each of the reported reasons weighed in their choice to vaccinate or not, on a 5-point likert scale (1 = Not at all , 5 = Extremely ). Due to the sparsity on the rate and the number of provided reasons we re-coded the provided information into two semi-quantitative variables, one for pro- and one for against- vaccination reasons, as following: missing/invalid reasons, low average rating (answers 1–3 on the Likert scale) and 1–3 reasons, high rating (answers 4–5 points on the Likert scale) and 1 reason, and high average rating (answer 4–5 points on the Likert scale) and 2–3 reasons.

The questionnaire also included the 20-item Short Profile of Emotional Competence scale (S-PEC; [ 38 ]) to measure intra- and inter-personal emotional competences separately. The intra-personal scale (10 items) refers to emotional competences related to oneself and it includes items such as "In my life I never make decisions based on my emotions'' or "I don't always understand why I react in a certain way". The inter-personal scale (10 items) refers to emotional competences related to other people and it includes items such as “If I wanted, I could easily make someone feel uneasy” or “Most of the time, I understand why the people feel the way they do”. All items are answered on a 7-point likert scale (1 = Not at all agree , 7 = Completely agree ). The internal consistency of the S-PEC scale, measured by means of Cronbach’s α, was adequate (α = 0.81). Further, we measured participants' risk perception of COVID-19 by asking them to indicate how scared they felt of the virus, how serious they think the disease is, how likely they think they are to get sick, and how worried they feel about the various mutations [ 10 , 31 ]. We then asked participants to report their age, gender, educational level, their occupation (health workers, white-collar workers, entrepreneurs, other non-health-related contract forms, and the unemployed), whether they already had COVID-19 (No or don't know, Yes asymptomatic, Yes with few symptoms, and Yes with severe symptoms). The questionnaire was pilot tested by 30 participants who filled the questionnaire first then were asked to discuss and comment on the comprehension of the wording of questions and answer options. Two questions were slightly reworded to improve clarity.

Scoring of reasons

In the first instance, a bottom-up process from reasons to categories was followed by reading a sample of both types of reasons, with the aim of constructing initial categorizing patterns. Examples of pro-vaccination reasons include protection of personal and public health, return to normality, and civic duty; while reasons against vaccination include fears for one's health, sociopolitical perplexity, and distrust of science and institutions (see Additional file 1 : Appendix 1). At this stage, response information was added to the categorizations indicating whether the responses were valid or missing/invalid. Specifically, valid responses had both a reason and the respective weight; missing/invalid responses were those where reason, weight or both were missing or with utterly unrelated concepts or meaningless strings or letters. Finally, by applying a top-down process, we constructed macro categories by merging specific conceptually assimilated categories, so as to avoid the dispersion of data into too many ramifications (see Table S 5 ).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis.

All the analyses were performed only on respondents with no missing observations on the variables of interest (1,681, 92%) excluding also a limited number of those with a non-valid set of pro- or against-vaccination reasons (Table S 1 ; 0.9%). The study variables were summarized in frequency tables and figures (frequency for categorical variables, median and Interquartile Range (IQR) for continuous variables). Kruskal–Wallis tests were computed to compare the distribution of continuous variables across the categories of vaccine status. Categorical variables were compared using chi-squared or Fisher's exact test where expected frequencies in any combination were less than 10. Statistical significance was assumed at the 5% level.

COVID-19 Perceived risk—exploratory factor analysis

An Exploratory Factorial Analysis (EFA) was performed on groups of variables related to COVID-19 perceived risk: scare, severity, contagiousness, and the likelihood of mutation. Since the presence of limited support (0–100 scale) and non-normal marginal distribution, the EFA was performed using a weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator. We extracted from the EFA only the first factor, which explained the highest percentage of variance (Table S 2 ; 61%). The estimated loadings were then used to calculate the regression factor scores. The number and the name of items included, their internal consistency (Cronbach’s α), the estimated loadings, and the proportion of deviance explained are reported in Table S 2 .

Propensity score weighting

At the time of data collection (March–April 2021), the vaccine offer was not opened to the entire population. To adjust the estimates of the following regression models for the propensity to receive the vaccine, we estimated a logistic regression model in which the dependent variable was the response to the question about a previous vaccination offer (Yes/No), while all the factors that can influence the vaccine proposal served as independent variables: age-class (young ≤ 25, young adult 26–45, adult 46–65, elderly 66–84), gender (male, female), occupational status (health worker, not at work, not health worker-employer, not health worker-entrepreneur, not health worker-other), educational level (low = middle school or lower, medium = high school, high = degree or higher), key worker status (yes, no, I don’t know), past COVID-19 contagion (no, yes asymptomatic, yes low symptoms, yes severe symptoms), and familiar status (single/in a relation, married/cohabitant, divorced/separated/other). The predicted probability was used to estimate the weights for the following regression models using a framework based on an inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW; for further details, see [ 39 ]).

Regression models

Our research questions can be summarized by trying to describe the relationship exploited by the directed acyclic graph in Fig. 1 . The first step regression model aims to assess how S-PEC scores (inter- and intra-personal) and COVID-19 risk perception influenced the reasons pro- and against-vaccination produced by participants while considering the presence of a set of confounders (age-class, gender, occupational status, educational level, key worker status, and familial status).

Since both the pro- and against-vaccination reasons are formed by a categorical variable with 4 levels (missing/invalid, low 1/2/3 reasons, high 1 reason, high 2/3 reasons), we evaluated whether S-PEC and COVID-19 risk perception scores influenced the distribution of pro- and against-vaccination reasons employing two different multinomial regression models including all the previously mentioned variables (S-PEC, COVID-19 risk perception, and confounders). The overall significance of a variable in the model was tested using an analysis of the variance (ANOVA).

The second step in the analyses was taken to investigate whether the generation of pro- and/or against-vaccination reasons affected the willingness to be vaccinated or the vaccine acceptance. Each participant reported their willingness to get vaccinated on a 0–100 scale or, in case a COVID-19 vaccine had been already offered, their vaccination status (done, booked, or refused). For respondents who had not yet been contacted for booking/getting the vaccination, we evaluated whether pro- and/or against vaccination reasons influenced the willingness to be vaccinated by employing a beta regression model in which the respondent variable scale (0–100) was rescaled to be a relative frequency [ 40 ]. The full models included the semi-quantitative pro- and against-vaccination reasons variables and, even if non-statistically significant, all the confounders in order to adjust for age class, gender, educational level, occupational status, familial status, and key worker status. Beta regression coefficients were estimated using a maximum likelihood estimator (MLE). Results were presented in terms of Odds Ratios (ORs) by exponentiating the estimated coefficients and producing a relative 95% Confidence Interval (95% CI).

A further regression analysis was conducted through a logistic regression model to explain which factors influenced vaccine acceptance (done/booked vs. refused) among those who already received the vaccine offers. The full model included the same variables considered in the previous beta regression model, after recoding the variables related to pro- and against-vaccination reasons into a binary form (missing/invalid vs. presence of at least one valid reason) due to low sample size and the sparsity of the response variable. As a consequence, we tested a simplified version of Hypothesis 3, considering the presence (vs. missing/invalid) of pro- or against-vaccination reasons in order to test their influence on the probability of having accepted/booked the vaccination.

Results were reported employing ORs and relative 95% Confidence Interval (95% CI).

Both the beta regression and logistic regression were weighed using an IPTW scheme to take into account the presence of a different probability of a vaccine offer among respondents.

The presence of an interaction between pro- and against-vaccination reasons was tested by means of a likelihood ratio test. The regression models were estimated through the R 4.0 program (R Core Team, 2021), and for the beta regression we employed the betareg package [ 41 ].

Classification tree analysis

Two different classification tree analyses were carried out to characterize profiles with a low or high willingness to get vaccinated (respondents who had not yet been offered a vaccine) or with a low or high probability to accept/book the vaccine (respondents who had already received a vaccine offer).

Although the dependent variables were non-normally distributed (scale 0–100 or binary 0/1), we considered them continuously distributed adopting a splitting criterion based on the analysis of the variance (ANOVA). We tested the inclusion in the model considering the type of pro- or against-vaccination reasons. A tree pruning strategy was adopted to reduce classification tree overfitting considering the overall determination coefficient (R 2 ) as an indicator and fixing that at each classification step in the tree if the R 2 did not increase by 0.5% the tree should be stopped. Classification tree analysis was performed using the rpart package [ 42 ] on R environment [ 43 ].

The main characteristics of the respondents by vaccination status (received, booked, not yet, and refused) were reported in Table 1 . Among respondents, 23.3% were offered the vaccination and, among them, 13.8% refused it (Fig. S 1 ). Among those not yet eligible, willingness to be vaccinated showed a median value of 80 points (average: 68.7). The distribution of gender was almost equal (51% females, 49% male), and the median age was 47 years old (IQR: 34–57 years). Educational level was low in 41% of the sample, while the most represented employment status was not at work (39%) followed by employed (37%), and entrepreneur (9.8%). A quarter (26%) of respondents classified themselves as key workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. The predominance of respondents (63%) were married or living with a partner, while only 9% had had a COVID-19 infection.

COVID-19 risk perception and the S-PEC score (intra- and inter-personal) were categorized into three categories according to empirical tertiles (low:1 st tertile, medium: 2 nd tertile, high: 3 rd tertile). The level of COVID-19 risk perception differed across vaccination status ( p < 0.001). The reasons pro- and against-vaccination have a different distribution according to COVID-19 vaccination status (Table 2 ). The highest frequency of pro-vaccination reasons was reported by those who received the COVID-19 vaccination; conversely the lowest frequency of pro-vaccination reasons was generated by those who refused the vaccine, whereas, intermediate frequencies were shown by people who were not yet offered the vaccination and those who had booked the vaccine, who reported a comparable distribution of the number of pro-vaccination reasons. A reverse pattern was exhibited for against-vaccination reasons, which were generated with the highest percentage by respondents who refused the vaccine (in particular high and multiple reasons). Conversely those who have booked/done the COVID-19 vaccine showed the lowest frequency of reasons against vaccination, while respondents without a vaccine offer reported an intermediate frequency of reasons against vaccination.

The estimated results of the propensity score model for the vaccine offer are shown in Table S 3 . Respondents older than 65 years exhibited a nearly four-fold increase in the probability to be contacted for the vaccination with respect to the reference age-class (≤ 25 years). All non-health employees showed a high drop in the probability of having received the vaccination offer, while the probability increased as the educational level increased. Being a key worker during pandemic resulted in an increased probability of having received the vaccination proposal while no statistical significant influence was observed for the past COVID-19 contagion or for familial status. The distribution of the propensity score by vaccine status obtained by the model is reported in Fig. S 1 , in which it is shown that the distribution is different by vaccine offer, but the two density functions partially overlap. The discriminant power of the propensity score estimated was only discrete (ROC analysis, AUC: 71.8%).