Anxiety Disorders and Depression Essay (Critical Writing)

Introduction, description section, feelings section, action plan, reference list.

Human beings become anxious in different situations that are uncertain to them. Depression and anxiety occur at a similar time. Anxiety is caused due to an overwhelming fear of an expected occurrence of an event that is unclear to a person. More than 25 million people globally are affected by anxiety disorders. People feel anxious in moments such as when making important decisions, before facing an interview panel, and before taking tests. Anxiety disorders are normally brained reactions to stress as they alert a person of impending danger. Most people feel sad and low due to disappointments. Feelings normally overwhelm a person leading to depression, especially during sad moments such as losing a loved one or divorce. When people are depressed, they engage in reckless behaviors such as drug abuse that affect them physically and emotionally. However, depression manifests in different forms in both men and women. Research shows that more women are depressed compared to men. This essay reflects on anxiety disorders and depression regarding from a real-life experience extracted from a publication.

“Every year almost 20% of the general population suffers from a common mental disorder, such as depression or an anxiety disorder” (Cuijpers et al. 2016, p.245). I came across a publication by Madison Jo Sieminski available who was diagnosed with depression and anxiety disorders (Madison 2020). She explains how she was first diagnosed with anxiety disorders and depression and how it felt unreal at first. She further says that she developed the need to get a distraction that would keep her busy so that she won’t embrace her situation. In her case, anxiety made her feel that she needed to do more, and everything needed to be perfect.

Madison further said that the struggle with anxiety is that it never seemed to happen, but it happened eventually. She always felt a feeling of darkness and loneliness. She could barely stay awake for more than 30 minutes for many days. Anxiety and depression made her question herself if she was good enough, and this resulted in tears in her eyes due to the burning sensation and overwhelmed emotions. In her own words, she said, “Do I deserve to be here? What is my purpose?” (Madison 2020). Anxiety made her lose confidence in herself and lowered her self-esteem. She could lay in bed most of the time and could not take any meal most of the days.

Madison said that since the sophomore year of high school, all was not well, and she suddenly felt someone in her head telling her to constantly worry and hold back from everything. She could wake up days when she could try a marathon to keep her mind busy. However, she sought help on 1 January 2020, since she felt her mental health was important, and she needed to be strong. She was relieved from her biggest worries, and what she thought was failure turned into a biggest achievement. She realized that her health needed to be her priority. Even after being diagnosed with depression disorders, she wanted to feel normal and have a normal lifestyle like other people.

Madison was happy with her decision to seek medical help even though she had her doubts. She was happy that she finally took that step to see a doctor since she was suffering in silence. She noted that the background of her depression and anxiety disorders was her family. It was kind of genetic since her mom also struggled with depression and anxiety disorders. Her mom was always upset, and this broke her heart. She said it took her years to better herself, but she still had bad days. Madison decided to take the challenge regarding her mother’s experience. Also, Madison said she was struggling to get over depression since her childhood friends committed suicide, and it affected her deeply. She also told the doctor how she often thought of harming herself. The doctor advised her on the different ways she could overcome her situation after discovering she had severe depression and anxiety disorders.

After going through Madison’s story, I was hurt by the fact that he had to go through that for a long time, and something tragic could have happened if she had not resorted to medical help. I felt emotional by the fact that she constantly blamed herself due to her friends who committed suicide, and she decided to accumulate all the pain and worries. The fact that I have heard stories of how people commit suicide due to depression and anxiety disorders made me have a somber mood considering her case. In this case, you will never know what people are going through in their private lives until they decide to open up. We normally assume every person is okay, yet they fight their demons and struggle to look okay. Hence, it won’t cost any person to check up on other people, especially if they suddenly change their social characters.

Madison’s story stood out for me since she had struggled since childhood to deal with depression and anxiety disorders. In her case, she was unable to seek help first even when she knew that she was suffering in silence (Madison 2020). However, most people find it hard to admit they need help regardless of what they are going through, like Madison. People who are depressed cannot work as they lack the motivation to do anything. In my knowledge, depression affects people close to you, including your family and friends. Depression also hurts those who love someone suffering from it. Hence, it is complex to deal with. Madison’s situation stood out for me since her childhood friends committed suicide, and she wished silently she could be with them. Hence, this leads to her constant thoughts of harming herself. Childhood friends at one point can become your family even though you are not related by blood due to the memories you share.

Depression and Anxiety disorders have been common mental health concerns globally for a long time. Depression and anxiety disorders create the impression that social interactions are vague with no meaning. It is argued by Cuijpers (2016, p.245) that people who are depressed normally have personality difficulties as they find it hard to trust people around them, including themselves. In this case, Madison spent most of her time alone, sleeping, and could not find it necessary to hang around other people. Negativity is the order of the day as people depressed find everything around them not interesting.

People who are depressed find it easy to induce negativity in others. Hence, they end up being rejected. Besides, if someone is depressed and is in a relationship, he/she may be the reason for ending the relationship since they would constantly find everything offensive. Research shows that people who are clinically depressed, such as Madison, prefer sad facial expressions to happy facial expressions. Besides, most teenagers in the 21 st century are depressed, and few parents tend to notice that. Also, most teenagers lack parental love and care since their parents are busy with their job routines and have no time to engage their children. Research has shown that suicide is the second cause of death among teenagers aged between 15-24 years due to mental disorders such as suicide and anxiety disorders.

Despite depression being a major concern globally, it can be controlled and contained if specific actions are taken. Any person needs to prioritize their mental health to avoid occurrences of depression and anxiety orders. Emotional responses can be used to gauge if a person is undergoing anxiety and depression. The best efficient way to deal with depression and anxiety is to sensitize people about depression through different media platforms (Cuijpers et al. 2016). A day in a month should be set aside where students in colleges are sensitized on the symptoms of depression and how to cope up with the situation. Some of the basic things to do to avoid anxiety and depression include; talking to someone when you are low, welcoming humor, learning the cause of your anxiety, maintaining a positive attitude, exercising daily, and having enough sleep.

Depression and anxiety disorders are different forms among people, such as irritability and nervousness. Most people are diagnosed with depression as a psychiatric disorder. Technology has been a major catalyst in enabling depression among people as they are exposed to many negative experiences online. Besides, some people are always motivated by actions of other people who seem to have given up due to depression. Many people who develop depression normally have a history of anxiety disorders. Therefore, people with depression need to seek medical attention before they harm themselves or even commit suicide. Also, people need to speak out about what they are going through to either their friends or people they trust. Speaking out enables people to relieve their burden and hence it enhances peace.

Cuijpers, P., Cristea, I.A., Karyotaki, E., Reijnders, M. and Huibers, M.J., 2016. How effective are cognitive behavior therapies for major depression and anxiety disorders? A meta‐analytic update of the evidence . World Psychiatry 15(3), pp. 245-258.

Madison, J. 2020. Open Doors .

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, June 16). Anxiety Disorders and Depression. https://ivypanda.com/essays/anxiety-disorders-and-depression/

"Anxiety Disorders and Depression." IvyPanda , 16 June 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/anxiety-disorders-and-depression/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Anxiety Disorders and Depression'. 16 June.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Anxiety Disorders and Depression." June 16, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/anxiety-disorders-and-depression/.

1. IvyPanda . "Anxiety Disorders and Depression." June 16, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/anxiety-disorders-and-depression/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Anxiety Disorders and Depression." June 16, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/anxiety-disorders-and-depression/.

- James Madison’s Leadership Qualities

- Madison PLC: Funding and Management

- James Madison’s Political Theory

- Madison Consultancy Group: Ethics and Conduct Program

- James Madison's Life, Service and Conduct

- James Madison and the United States Constitution

- Constitution and James Madison’s Influence on It

- Concept Care Plan Mapping: Eva Madison

- The United States Supreme Court: Marbury vs. Madison

- Federalist Paper Number 10

- Cerebral Palsy: Epidemiology and Etiology

- Neurological System Disorder of Falling Asleep

- Migraine Headache and Tension Headache Compared

- Neurodevelopmentally at‐Risk Infants

- Migraine Without Aura Treatment Plan

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 4 CURRENT ISSUE pp.255-346

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 3 pp.171-254

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 2 pp.83-170

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 1 pp.1-82

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

The Critical Relationship Between Anxiety and Depression

- Ned H. Kalin , M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

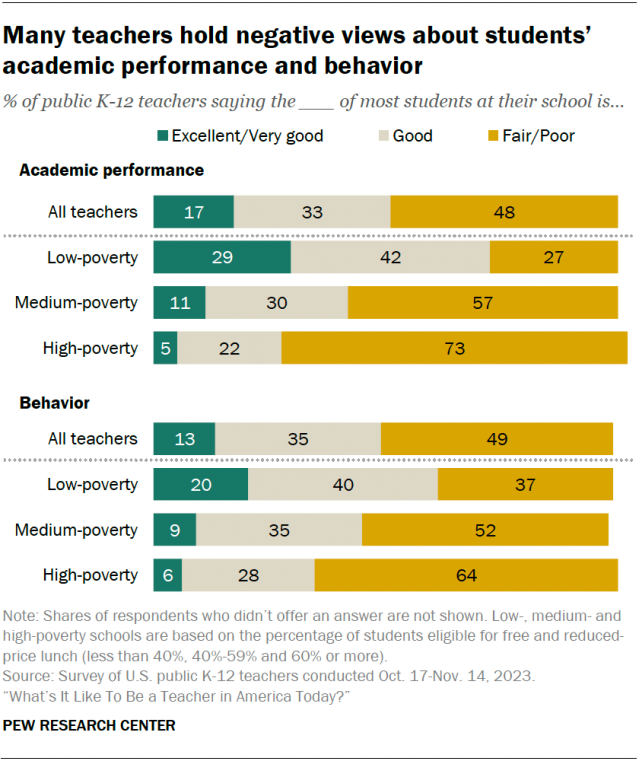

Anxiety and depressive disorders are among the most common psychiatric illnesses; they are highly comorbid with each other, and together they are considered to belong to the broader category of internalizing disorders. Based on statistics from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the 12-month prevalence of major depressive disorder in 2017 was estimated to be 7.1% for adults and 13.3% for adolescents ( 1 ). Data for anxiety disorders are less current, but in 2001–2003, their 12-month prevalence was estimated to be 19.1% in adults, and 2001–2004 data estimated that the lifetime prevalence in adolescents was 31.9% ( 2 , 3 ). Both anxiety and depressive disorders are more prevalent in women, with an approximate 2:1 ratio in women compared with men during women’s reproductive years ( 1 , 2 ).

Across all psychiatric disorders, comorbidity is the rule ( 4 ), which is definitely the case for anxiety and depressive disorders, as well as their symptoms. With respect to major depression, a worldwide survey reported that 45.7% of individuals with lifetime major depressive disorder had a lifetime history of one or more anxiety disorder ( 5 ). These disorders also commonly coexist during the same time frame, as 41.6% of individuals with 12-month major depression also had one or more anxiety disorder over the same 12-month period. From the perspective of anxiety disorders, the lifetime comorbidity with depression is estimated to range from 20% to 70% for patients with social anxiety disorder ( 6 ), 50% for patients with panic disorder ( 6 ), 48% for patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) ( 7 ), and 43% for patients with generalized anxiety disorder ( 8 ). Data from the well-known Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study demonstrate comorbidity at the symptom level, as 53% of the patients with major depression had significant anxiety and were considered to have an anxious depression ( 9 ).

Anxiety and depressive disorders are moderately heritable (approximately 40%), and evidence suggests shared genetic risk across the internalizing disorders ( 10 ). Among internalizing disorders, the highest level of shared genetic risk appears to be between major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Neuroticism is a personality trait or temperamental characteristic that is associated with the development of both anxiety and depression, and the genetic risk for developing neuroticism also appears to be shared with that of the internalizing disorders ( 11 ). Common nongenetic risk factors associated with the development of anxiety and depression include earlier life adversity, such as trauma or neglect, as well as parenting style and current stress exposure. At the level of neural circuits, alterations in prefrontal-limbic pathways that mediate emotion regulatory processes are common to anxiety and depressive disorders ( 12 , 13 ). These findings are consistent with meta-analyses that reveal shared structural and functional brain alterations across various psychiatric illnesses, including anxiety and major depression, in circuits involving emotion regulation ( 13 ), executive function ( 14 ), and cognitive control ( 15 ).

Anxiety disorders and major depression occur during development, with anxiety disorders commonly beginning during preadolescence and early adolescence and major depression tending to emerge during adolescence and early to mid-adulthood ( 16 – 18 ). In relation to the evolution of their comorbidity, studies demonstrate that anxiety disorders generally precede the presentation of major depressive disorder ( 17 ). A European community-based study revealed, beginning at age 15, the developmental relation between comorbid anxiety and major depression by specifically focusing on social phobia (based on DSM-IV criteria) and then asking the question regarding concurrent major depressive disorder ( 18 ). The findings revealed a 19% concurrent comorbidity between these disorders, and in 65% of the cases, social phobia preceded major depressive disorder by at least 2 years. In addition, initial presentation with social phobia was associated with a 5.7-fold increased risk of developing major depressive disorder. These associations between anxiety and depression can be traced back even earlier in life. For example, childhood behavioral inhibition in response to novelty or strangers, or an extreme anxious temperament, is associated with a three- to fourfold increase in the likelihood of developing social anxiety disorder, which in turn is associated with an increased risk to develop major depressive disorder and substance abuse ( 19 ).

It is important to emphasize that the presence of comor‐bid anxiety symptoms and disorders matters in relation to treatment. Across psychiatric disorders, the presence of significant anxiety symptoms generally predicts worse outcomes, and this has been well demonstrated for depression. In the STAR*D study, patients with anxious major depressive disorder were more likely to be severely depressed and to have more suicidal ideation ( 9 ). This is consistent with the study by Kessler and colleagues ( 5 ), in which patients with anxious major depressive disorder, compared with patients with nonanxious major depressive disorder, were found to have more severe role impairment and more suicidal ideation. Data from level 1 of the STAR*D study (citalopram treatment) nicely illustrate the impact of comorbid anxiety symptoms on treatment. Compared with patients with nonanxious major depressive disorder, those 53% of patients with an anxious depression were less likely to remit and also had a greater side effect burden ( 20 ). Other data examining patients with major depressive disorder and comorbid anxiety disorders support the greater difficulty and challenge in treating patients with these comorbidities ( 21 ).

This issue of the Journal presents new findings relevant to the issues discussed above in relation to understanding and treating anxiety and depressive disorders. Drs. Conor Liston and Timothy Spellman, from Weill Cornell Medicine, provide an overview for this issue ( 22 ) that is focused on understanding mechanisms at the neural circuit level that underlie the pathophysiology of depression. Their piece nicely integrates human neuroimaging studies with complementary data from animal models that allow for the manipulation of selective circuits to test hypotheses generated from the human data. Also included in this issue is a review of the data addressing the reemergence of the use of psychedelic drugs in psychiatry, particularly for the treatment of depression, anxiety, and PTSD ( 23 ). This timely piece, authored by Dr. Collin Reiff along with a subgroup from the APA Council of Research, provides the current state of evidence supporting the further exploration of these interventions. Dr. Alan Schatzberg, from Stanford University, contributes an editorial in which he comments on where the field is in relation to clinical trials with psychedelics and to some of the difficulties, such as adequate blinding, in reliably studying the efficacy of these drugs ( 24 ).

In an article by McTeague et al. ( 25 ), the authors use meta-analytic strategies to understand the neural alterations that are related to aberrant emotion processing that are shared across psychiatric disorders. Findings support alterations in the salience, reward, and lateral orbital nonreward networks as common across disorders, including anxiety and depressive disorders. These findings add to the growing body of work that supports the concept that there are common underlying factors across all types of psychopathology that include internalizing, externalizing, and thought disorder dimensions ( 26 ). Dr. Deanna Barch, from Washington University in St. Louis, writes an editorial commenting on these findings and, importantly, discusses criteria that should be met when we consider whether the findings are actually transdiagnostic ( 27 ).

Another article, from Gray and colleagues ( 28 ), addresses whether there is a convergence of findings, specifically in major depression, when examining data from different structural and functional neuroimaging modalities. The authors report that, consistent with what we know about regions involved in emotion processing, the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala were among the regions that showed convergence across multimodal imaging modalities.

In relation to treatment and building on our understanding of neural circuit alterations, Siddiqi et al. ( 29 ) present data suggesting that transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) targeting can be linked to symptom-specific treatments. Their findings identify different TMS targets in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex that modulate different downstream networks. The modulation of these different networks appears to be associated with a reduction in different types of symptoms. In an editorial, Drs. Sean Nestor and Daniel Blumberger, from the University of Toronto ( 30 ), comment on the novel approach used in this study to link the TMS-related engagement of circuits with symptom improvement. They also provide a perspective on how we can view these and other circuit-based findings in relation to conceptualizing personalized treatment approaches.

Kendler et al. ( 31 ), in this issue, contribute an article that demonstrates the important role of the rearing environment in the risk to develop major depression. Using a unique design from a Swedish sample, the analytic strategy involves comparing outcomes from high-risk full sibships and high-risk half sibships where at least one of the siblings was home reared and one was adopted out of the home. The findings support the importance of the quality of the rearing environment as well as the presence of parental depression in mitigating or enhancing the likelihood of developing major depression. In an accompanying editorial ( 32 ), Dr. Myrna Weissman, from Columbia University, reviews the methods and findings of the Kendler et al. article and also emphasizes the critical significance of the early nurturing environment in relation to general health.

This issue concludes with an intriguing article on anxiety disorders, by Gold and colleagues ( 33 ), that demonstrates neural alterations during extinction recall that differ in children relative to adults. With increasing age, and in relation to fear and safety cues, nonanxious adults demonstrated greater connectivity between the amygdala and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex compared with anxious adults, as the cues were being perceived as safer. In contrast, neural differences between anxious and nonanxious youths were more robust when rating the memory of faces that were associated with threat. Specifically, these differences were observed in the activation of the inferior temporal cortex. In their editorial ( 34 ), Dr. Dylan Gee and Sahana Kribakaran, from Yale University, emphasize the importance of developmental work in relation to understanding anxiety disorders, place these findings into the context of other work, and suggest the possibility that these and other data point to neuroscientifically informed age-specific interventions.

Taken together, the papers in this issue of the Journal present new findings that shed light onto alterations in neural function that underlie major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. It is important to remember that these disorders are highly comorbid and that their symptoms are frequently not separable. The papers in this issue also provide a developmental perspective emphasizing the importance of early rearing in the risk to develop depression and age-related findings important for understanding threat processing in patients with anxiety disorders. From a treatment perspective, the papers introduce data supporting more selective prefrontal cortical TMS targeting in relation to different symptoms, address the potential and drawbacks for considering the future use of psychedelics in our treatments, and present new ideas supporting age-specific interventions for youths and adults with anxiety disorders.

Disclosures of Editors’ financial relationships appear in the April 2020 issue of the Journal .

1 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA): Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 18-5068, NSDUH Series H-53). Rockville, Md, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, SAMHSA, 2018. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHFFR2017/NSDUHFFR2017.htm Google Scholar

2 Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. : Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication . Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005 ; 62:617–627, correction, 62:709 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

3 Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et al. : Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) . J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010 ; 49:980–989 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

4 Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. : Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey . Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994 ; 51:8–19 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

5 Kessler RC, Sampson NA, Berglund P, et al. : Anxious and non-anxious major depressive disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys . Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2015 ; 24:210–226 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

6 Dunner DL : Management of anxiety disorders: the added challenge of comorbidity . Depress Anxiety 2001 ; 13:57–71 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

7 Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al. : Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey . Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995 ; 52:1048–1060 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

8 Brawman-Mintzer O, Lydiard RB, Emmanuel N, et al. : Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with generalized anxiety disorder . Am J Psychiatry 1993 ; 150:1216–1218 Link , Google Scholar

9 Fava M, Alpert JE, Carmin CN, et al. : Clinical correlates and symptom patterns of anxious depression among patients with major depressive disorder in STAR*D . Psychol Med 2004 ; 34:1299–1308 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

10 Hettema JM : What is the genetic relationship between anxiety and depression? Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2008 ; 148C:140–146 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

11 Hettema JM, Neale MC, Myers JM, et al. : A population-based twin study of the relationship between neuroticism and internalizing disorders . Am J Psychiatry 2006 ; 163:857–864 Link , Google Scholar

12 Kovner R, Oler JA, Kalin NH : Cortico-limbic interactions mediate adaptive and maladaptive responses relevant to psychopathology . Am J Psychiatry 2019 ; 176:987–999 Link , Google Scholar

13 Etkin A, Schatzberg AF : Common abnormalities and disorder-specific compensation during implicit regulation of emotional processing in generalized anxiety and major depressive disorders . Am J Psychiatry 2011 ; 168:968–978 Link , Google Scholar

14 Goodkind M, Eickhoff SB, Oathes DJ, et al. : Identification of a common neurobiological substrate for mental illness . JAMA Psychiatry 2015 ; 72:305–315 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

15 McTeague LM, Huemer J, Carreon DM, et al. : Identification of common neural circuit disruptions in cognitive control across psychiatric disorders . Am J Psychiatry 2017 ; 174:676–685 Link , Google Scholar

16 Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS : Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V . Psychiatr Clin North Am 2009 ; 32:483–524 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

17 Kessler RC, Wang PS : The descriptive epidemiology of commonly occurring mental disorders in the United States . Annu Rev Public Health 2008 ; 29:115–129 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

18 Ohayon MM, Schatzberg AF : Social phobia and depression: prevalence and comorbidity . J Psychosom Res 2010 ; 68:235–243 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

19 Clauss JA, Blackford JU : Behavioral inhibition and risk for developing social anxiety disorder: a meta-analytic study . J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012 ; 51:1066–1075 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

20 Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, et al. : Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report . Am J Psychiatry 2008 ; 165:342–351 Link , Google Scholar

21 Dold M, Bartova L, Souery D, et al. : Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of patients with major depressive disorder and comorbid anxiety disorders: results from a European multicenter study . J Psychiatr Res 2017 ; 91:1–13 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

22 Spellman T, Liston C : Toward circuit mechanisms of pathophysiology in depression . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:381–390 Link , Google Scholar

23 Reiff CM, Richman EE, Nemeroff CB, et al. : Psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:391–410 Link , Google Scholar

24 Schatzberg AF : Some comments on psychedelic research (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:368–369 Link , Google Scholar

25 McTeague LM, Rosenberg BM, Lopez JW, et al. : Identification of common neural circuit disruptions in emotional processing across psychiatric disorders . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:411–421 Link , Google Scholar

26 Caspi A, Moffitt TE : All for one and one for all: mental disorders in one dimension . Am J Psychiatry 2018 ; 175:831–844 Link , Google Scholar

27 Barch DM : What does it mean to be transdiagnostic and how would we know? (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:370–372 Abstract , Google Scholar

28 Gray JP, Müller VI, Eickhoff SB, et al. : Multimodal abnormalities of brain structure and function in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:422–434 Link , Google Scholar

29 Siddiqi SH, Taylor SF, Cooke D, et al. : Distinct symptom-specific treatment targets for circuit-based neuromodulation . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:435–446 Link , Google Scholar

30 Nestor SM, Blumberger DM : Mapping symptom clusters to circuits: toward personalizing TMS targets to improve treatment outcomes in depression (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:373–375 Abstract , Google Scholar

31 Kendler KS, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J, et al. : The rearing environment and risk for major depression: a Swedish national high-risk home-reared and adopted-away co-sibling control study . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:447–453 Abstract , Google Scholar

32 Weissman MM : Is depression nature or nurture? Yes (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:376–377 Abstract , Google Scholar

33 Gold AL, Abend R, Britton JC, et al. : Age differences in the neural correlates of anxiety disorders: an fMRI study of response to learned threat . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:454–463 Link , Google Scholar

34 Gee DG, Kribakaran S : Developmental differences in neural responding to threat and safety: implications for treating youths with anxiety (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:378–380 Abstract , Google Scholar

- Cited by None

- Neuroanatomy

- Neurochemistry

- Neuroendocrinology

- Other Research Areas

Personal Stories

We want to hear your story.

Tell us how mental illness has affected your life.

Share Your Story

Find Your Local NAMI

Call the NAMI Helpline at

800-950-6264

Or text "HelpLine" to 62640

My Depression in My Life

Depression is something that shows itself differently for everyone. There is no one person, or one story, or one experience that can make someone universally understand truly how depression alters the lives of those of us who suffer from it. I can’t make anyone understand how it is for everyone, but I can tell you how it alters my life, and maybe that will help people understand how all-encompassing it really is.

For me there are two main ways that my depression manifests itself when it breaks through the barriers I have set with the help of years of therapy and medication. There is the gut wrenching loneliness and near constant anxiety and then there is the checking out, the feeling nothing at all, the numbness. Sometimes I don’t know which is worse, but I will try to explain both.

The Loneliness and Anxiety:

In some ways I consider this step one of when my depression spikes because it always seems to come first. But I don’t consider it step one in levels of horribleness. Like I said above I really think that both ways my depression hits me are pretty awful and I couldn’t say which is worse.

You know that feeling you have in your gut when you are about to and/or really need to cry. While that is what it is like. All the time. I could be laughing and having a great time with my friends, which I often am because my friends are great, and yet in the back of my mind I feel more alone than ever and I just want to curl up into fetal position and cry. But I never can. I can’t go home and cry and then feel better, because it’s not like there is something to cry about, or really anything to be sad about. And it isn’t really sadness. It is complete solitude. It’s when my brain tells me that I am alone, that I can’t be loved, that no one really wants me around, and worst of all that no one will understand me.

That is worst of all because at the place I am in my life, no matter what I have been through in the past, or what my depression tries to make me believe I know that I can be loved, that I’m not alone and that I am wanted. And I know that because of the hard work I have done to get to that place in my life, and because of some of the amazing people in my life who make sure that I know that they are there for me, that they love me, and that they want to spend time with me.

But the idea that no one will ever truly understand who I am, or any of that. That is a little harder to dissuade myself from believing. Because as much as I can tell people what I went, and still go through and what goes through my mind, who can really understand me other than me. And that isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but the way my depression tells me it, it is a bad thing.

So there I am surrounded by people, very possibly having some of the best experiences of my life, feeling like I need to bawl, completely unable to, and nearly having an anxiety attack because I just want it to end.

And it is here where two things happen. It is here where I wish for and welcome the numbness because I don’t want to feel the all-encompassing loneliness and anxiety. It is also where I think about cutting.

I have not cut myself in three and a half years. And I know that it doesn’t solve my problems. I know that I shouldn’t and I don’t want to. Even when I want to I don’t want to.

But here, when I am feeling the all-encompassing loneliness which is the very last thing that I want to feel, I think about cutting because it lets me feel something else.

The physical act of cutting gives me something to think about and focus on, something other than that loneliness. And when I am not physically cutting, instead of thinking about how lonely I am and how that feeling will never end I think about the next time I can cut, or the most recent time I did.

And Then The Numbness:

I don’t really know how to explain this numbness. It is simply a period of time where I feel literally nothing. I fake happiness/normal emotion around friends, not always very well, and when I am alone I just don’t care about anything.

This is when my grades often fall because I don’t care about anything, including school, and therefore school work.

And then, sometimes I just want to feel something, anything, and so that is when I think about cutting. I think about cutting because it gives me something to feel, something I can control, but still feel.

The numbness comes because I can’t handle what I’m thinking and feeling, because it is too much for me to deal with, so I shut everything off so I don’t have to feel it.

In some ways, cutting transitions me back into feeling. But again, cutting, NOT A SOLUTION, NOT HEALTHY.

And something that I no longer do.

Now, for the past three and a half years, whenever I think of cutting, which I still do. It is still my first thought in either of these situations, I instead do one of the many things that I have come to know to help me cope.

For example, I force myself to spend more time with my friends, because I know that the loneliness will pass and I can talk myself out of feeling lonely when I am not physically alone.

I read/watch anything romantic. I pretend that I am one of the characters, and then I feel what they feel instead of what I am feeling (or preventing myself from feeling).

I belt along to old school Taylor Swift. Because what is more beautiful than a summer romance in a small country town with Chevy trucks and Tim McGraw?

And though my schoolwork does still sometimes fall through the cracks, I always make myself do some work.

Basically I force myself to live my life, because well, it is my life, and I refuse to live it feeling alone when I’m not, and numb when I could be great.

So even though I do feel those things far more often than I would like it is something that I live with, because I have depression.

Because depression is a disease, and I will always have it.

Because my depression is a part of who I am.

And most of all, because I only have one life, and I want to live it. Because even though when my depression spikes it makes me want to not live sometimes, I refuse.

Because I am the author of my own life and I choose to put a semicolon instead of a period at every point that my depression tells me otherwise.

So that is how my depression affects my life. That is how I deal with it. Like it or not I always will.

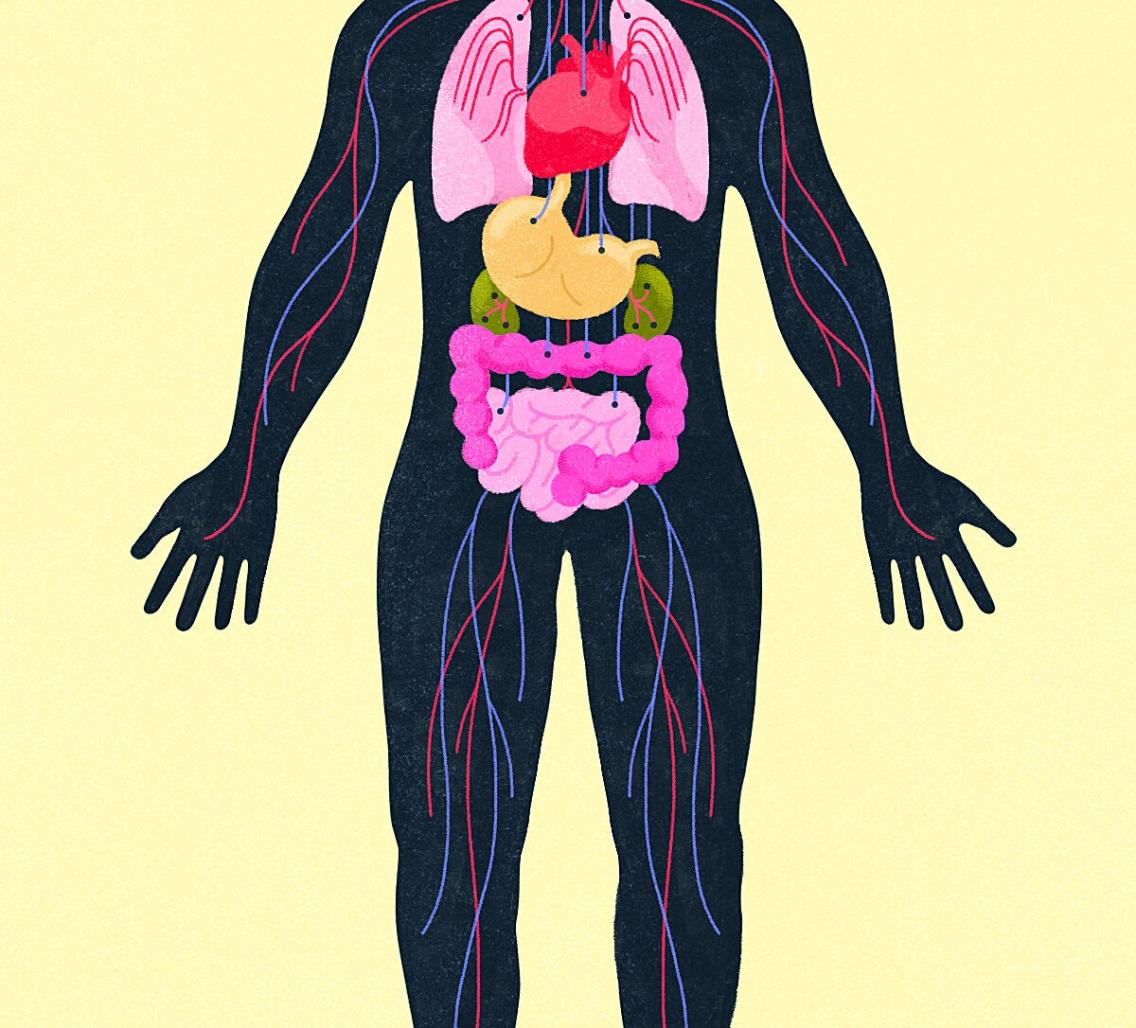

The Devastating Ways Depression and Anxiety Impact the Body

By Jane Brody

It’s no surprise that when a person gets a diagnosis of heart disease, cancer or some other life-limiting or life-threatening physical ailment, they become anxious or depressed. But the reverse can also be true: Undue anxiety or depression can foster the development of a serious physical disease, and even impede the ability to withstand or recover from one. The potential consequences are particularly timely, as the ongoing stress and disruptions of the pandemic continue to take a toll on mental health .

The human organism does not recognize the medical profession’s artificial separation of mental and physical ills. Rather, mind and body form a two-way street. What happens inside a person’s head can have damaging effects throughout the body, as well as the other way around. An untreated mental illness can significantly increase the risk of becoming physically ill, and physical disorders may result in behaviors that make mental conditions worse.

In studies that tracked how patients with breast cancer fared, for example, Dr. David Spiegel and his colleagues at Stanford University School of Medicine showed decades ago that women whose depression was easing lived longer than those whose depression was getting worse. His research and other studies have clearly shown that “the brain is intimately connected to the body and the body to the brain,” Dr. Spiegel said in an interview. “The body tends to react to mental stress as if it was a physical stress.”

Despite such evidence, he and other experts say, chronic emotional distress is too often overlooked by doctors. Commonly, a physician will prescribe a therapy for physical ailments like heart disease or diabetes, only to wonder why some patients get worse instead of better.

Many people are reluctant to seek treatment for emotional ills. Some people with anxiety or depression may fear being stigmatized, even if they recognize they have a serious psychological problem. Many attempt to self-treat their emotional distress by adopting behaviors like drinking too much or abusing drugs, which only adds insult to their pre-existing injury.

And sometimes, family and friends inadvertently reinforce a person’s denial of mental distress by labeling it as “that’s just the way he is” and do nothing to encourage them to seek professional help.

How common are anxiety and depression?

Anxiety disorders affect nearly 20 percent of American adults . That means millions are beset by an overabundance of the fight-or-flight response that primes the body for action. When you’re stressed, the brain responds by prompting the release of cortisol, nature’s built-in alarm system. It evolved to help animals facing physical threats by increasing respiration, raising the heart rate and redirecting blood flow from abdominal organs to muscles that assist in confronting or escaping danger.

These protective actions stem from the neurotransmitters epinephrine and norepinephrine, which stimulate the sympathetic nervous system and put the body on high alert. But when they are invoked too often and indiscriminately, the chronic overstimulation can result in all manner of physical ills, including digestive symptoms like indigestion, cramps, diarrhea or constipation, and an increased risk of heart attack or stroke.

Depression, while less common than chronic anxiety, can have even more devastating effects on physical health. While it’s normal to feel depressed from time to time, more than 6 percent of adults have such persistent feelings of depression that it disrupts personal relationships, interferes with work and play, and impairs their ability to cope with the challenges of daily life. Persistent depression can also exacerbate a person’s perception of pain and increase their chances of developing chronic pain.

“Depression diminishes a person’s capacity to analyze and respond rationally to stress,” Dr. Spiegel said. “They end up on a vicious cycle with limited capacity to get out of a negative mental state.”

Potentially making matters worse, undue anxiety and depression often coexist, leaving people vulnerable to a panoply of physical ailments and an inability to adopt and stick with needed therapy.

A study of 1,204 elderly Korean men and women initially evaluated for depression and anxiety found that two years later, these emotional disorders increased their risk of physical disorders and disability. Anxiety alone was linked with heart disease, depression alone was linked with asthma, and the two together were linked with eyesight problems, persistent cough, asthma, hypertension, heart disease and gastrointestinal problems.

Treatment can counter emotional tolls

Although persistent anxiety and depression are highly treatable with medications, cognitive behavioral therapy and talk therapy, without treatment these conditions tend to get worse. According to Dr. John Frownfelter, treatment for any condition works better when doctors understand “the pressures patients face that affect their behavior and result in clinical harm.”

Dr. Frownfelter is an internist and chief medical officer of a start-up called Jvion. The organization uses artificial intelligence to identify not just medical factors but psychological, social and behavioral ones as well that can impact the effectiveness of treatment on patients’ health. Its aim is to foster more holistic approaches to treatment that address the whole patient, body and mind combined.

The analyses used by Jvion, a Hindi word meaning life-giving, could alert a doctor when underlying depression might be hindering the effectiveness of prescribed treatments for another condition. For example, patients being treated for diabetes who are feeling hopeless may fail to improve because they take their prescribed medication only sporadically and don’t follow a proper diet, Dr. Frownfelter said.

“We often talk about depression as a complication of chronic illness,” Dr. Frownfelter wrote in Medpage Today in July . “But what we don’t talk about enough is how depression can lead to chronic disease. Patients with depression may not have the motivation to exercise regularly or cook healthy meals. Many also have trouble getting adequate sleep.”

Some changes to medical care during the pandemic have greatly increased patient access to depression and anxiety treatment. The expansion of telehealth has enabled patients to access treatment by psychotherapists who may be as far as a continent away.

Patients may also be able to treat themselves without the direct help of a therapist. For example, Dr. Spiegel and his co-workers created an app called Reveri that teaches people self-hypnosis techniques designed to help reduce stress and anxiety, improve sleep, reduce pain and suppress or quit smoking.

Improving sleep is especially helpful, Dr. Spiegel said, because “it enhances a person’s ability to regulate the stress response system and not get stuck in a mental rut.” Data demonstrating the effectiveness of the Reveri app has been collected but not yet published, he said.

Jane Brody is the Personal Health columnist, a position she has held since 1976. She has written more than a dozen books including the best sellers “Jane Brody’s Nutrition Book” and “Jane Brody’s Good Food Book.”

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Personal Health

The Devastating Ways Depression and Anxiety Impact the Body

Mind and body form a two-way street.

By Jane E. Brody

It’s no surprise that when a person gets a diagnosis of heart disease, cancer or some other life-limiting or life-threatening physical ailment, they become anxious or depressed. But the reverse can also be true: Undue anxiety or depression can foster the development of a serious physical disease, and even impede the ability to withstand or recover from one. The potential consequences are particularly timely, as the ongoing stress and disruptions of the pandemic continue to take a toll on mental health .

The human organism does not recognize the medical profession’s artificial separation of mental and physical ills. Rather, mind and body form a two-way street. What happens inside a person’s head can have damaging effects throughout the body, as well as the other way around. An untreated mental illness can significantly increase the risk of becoming physically ill, and physical disorders may result in behaviors that make mental conditions worse.

In studies that tracked how patients with breast cancer fared, for example, Dr. David Spiegel and his colleagues at Stanford University School of Medicine showed decades ago that women whose depression was easing lived longer than those whose depression was getting worse. His research and other studies have clearly shown that “the brain is intimately connected to the body and the body to the brain,” Dr. Spiegel said in an interview. “The body tends to react to mental stress as if it was a physical stress.”

Despite such evidence, he and other experts say, chronic emotional distress is too often overlooked by doctors. Commonly, a physician will prescribe a therapy for physical ailments like heart disease or diabetes, only to wonder why some patients get worse instead of better.

Many people are reluctant to seek treatment for emotional ills. Some people with anxiety or depression may fear being stigmatized, even if they recognize they have a serious psychological problem. Many attempt to self-treat their emotional distress by adopting behaviors like drinking too much or abusing drugs, which only adds insult to their pre-existing injury.

And sometimes, family and friends inadvertently reinforce a person’s denial of mental distress by labeling it as “that’s just the way he is” and do nothing to encourage them to seek professional help.

How common are anxiety and depression?

Anxiety disorders affect nearly 20 percent of American adults . That means millions are beset by an overabundance of the fight-or-flight response that primes the body for action. When you’re stressed, the brain responds by prompting the release of cortisol, nature’s built-in alarm system. It evolved to help animals facing physical threats by increasing respiration, raising the heart rate and redirecting blood flow from abdominal organs to muscles that assist in confronting or escaping danger.

These protective actions stem from the neurotransmitters epinephrine and norepinephrine, which stimulate the sympathetic nervous system and put the body on high alert. But when they are invoked too often and indiscriminately, the chronic overstimulation can result in all manner of physical ills, including digestive symptoms like indigestion, cramps, diarrhea or constipation, and an increased risk of heart attack or stroke.

Depression, while less common than chronic anxiety, can have even more devastating effects on physical health. While it’s normal to feel depressed from time to time, more than 6 percent of adults have such persistent feelings of depression that it disrupts personal relationships, interferes with work and play, and impairs their ability to cope with the challenges of daily life. Persistent depression can also exacerbate a person’s perception of pain and increase their chances of developing chronic pain.

“Depression diminishes a person’s capacity to analyze and respond rationally to stress,” Dr. Spiegel said. “They end up on a vicious cycle with limited capacity to get out of a negative mental state.”

Potentially making matters worse, undue anxiety and depression often coexist, leaving people vulnerable to a panoply of physical ailments and an inability to adopt and stick with needed therapy.

A study of 1,204 elderly Korean men and women initially evaluated for depression and anxiety found that two years later, these emotional disorders increased their risk of physical disorders and disability. Anxiety alone was linked with heart disease, depression alone was linked with asthma, and the two together were linked with eyesight problems, persistent cough, asthma, hypertension, heart disease and gastrointestinal problems.

Treatment can counter emotional tolls

Although persistent anxiety and depression are highly treatable with medications, cognitive behavioral therapy and talk therapy, without treatment these conditions tend to get worse. According to Dr. John Frownfelter, treatment for any condition works better when doctors understand “the pressures patients face that affect their behavior and result in clinical harm.”

Dr. Frownfelter is an internist and chief medical officer of a start-up called Jvion. The organization uses artificial intelligence to identify not just medical factors but psychological, social and behavioral ones as well that can impact the effectiveness of treatment on patients’ health. Its aim is to foster more holistic approaches to treatment that address the whole patient, body and mind combined.

The analyses used by Jvion, a Hindi word meaning life-giving, could alert a doctor when underlying depression might be hindering the effectiveness of prescribed treatments for another condition. For example, patients being treated for diabetes who are feeling hopeless may fail to improve because they take their prescribed medication only sporadically and don’t follow a proper diet, Dr. Frownfelter said.

“We often talk about depression as a complication of chronic illness,” Dr. Frownfelter wrote in Medpage Today in July . “But what we don’t talk about enough is how depression can lead to chronic disease. Patients with depression may not have the motivation to exercise regularly or cook healthy meals. Many also have trouble getting adequate sleep.”

Some changes to medical care during the pandemic have greatly increased patient access to depression and anxiety treatment. The expansion of telehealth has enabled patients to access treatment by psychotherapists who may be as far as a continent away.

Patients may also be able to treat themselves without the direct help of a therapist. For example, Dr. Spiegel and his co-workers created an app called Reveri that teaches people self-hypnosis techniques designed to help reduce stress and anxiety, improve sleep, reduce pain and suppress or quit smoking.

Improving sleep is especially helpful, Dr. Spiegel said, because “it enhances a person’s ability to regulate the stress response system and not get stuck in a mental rut.” Data demonstrating the effectiveness of the Reveri app has been collected but not yet published, he said.

Jane Brody is the Personal Health columnist, a position she has held since 1976. She has written more than a dozen books including the best sellers “Jane Brody’s Nutrition Book” and “Jane Brody’s Good Food Book.” More about Jane E. Brody

Jane Brody’s Personal Health Advice

After joining the new york times in 1965, she was its personal health columnist from 1976 to 2022. revisit some of her most memorable writing:.

Brody’s first column, on jogging , ran on Nov. 10, 1976. Her last, on Feb. 21. In it, she highlighted the evolution of health advice throughout her career.

Personal Health has often offered useful advice and a refreshing perspective. Declutter? This is why you must . Cup of coffee? Yes, please.

As a columnist, she has never been afraid to try out, and write about, new things — from intermittent fasting to knitting groups .

How do you put into words the pain of losing a spouse of 43 years? It is “nothing like losing a parent,” she wrote of her own experience with grieving .

Need advice on aging? She has explored how to do it gracefully , building muscle strength and knee replacements .

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Anxiety vs. Depression Symptoms and Treatment

Overlapping and distinguishing features of anxiety and depression

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Deborah-R.-Glasofer-PhD-1000-7cac259d94c641a7b388a605ec430842.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

The terms “anxious” and “depressed” get thrown around a lot in casual conversation—and for good reason. Both are normal emotions to experience, routinely occurring in response to high-stakes or potentially dangerous situations (in the case of anxiety) or disappointing, upsetting circumstances (in the case of depression).

The relationship between these emotions—and their associated clinical conditions, anxiety disorders and mood disorders—is complex and somewhat idiosyncratic.

For one person, anxiety can lead to avoidance and isolation. Isolation can result in a lack of opportunity for pleasurable experiences, which then leads to low mood. For others, the emotions may flow in the opposite direction. Feeling down may zap someone of the energy to do things they typically enjoy, and attempts to re-engage with the world after being out of practice may result in nervousness.

Understanding the distinctions between the two emotions (anxiety vs. depression) and characterizing the severity of the problem can help you to determine how to feel better.

The Relationship Between Anxiety and Depression

Anxiety and depression share a biological basis. Persistent states of anxiety or low mood like those experienced by people with clinical anxiety and mood disorders involve changes in neurotransmitter function. Low serotonin levels are thought to play a role in both, along with other brain chemicals such as dopamine and epinephrine.

While the biological underpinnings of these problems are similar, anxiety and depression are experienced differently. In this way, the two states might be considered two sides of the same coin.

Anxiety and depression can occur sequentially (one in reaction to the other), or they can co-occur. When anxiety and mood problems reach the threshold for clinical diagnosis simultaneously, the specific diagnoses are considered comorbid conditions .

Mental Differences: Anxiety vs. Depression

Anxiety and depression have distinct psychological features. Their mental markers (symptoms or expressions of the condition) are different.

Mental Markers of Anxiety

People with anxiety may:

Worry about the immediate or long-term future

- Have uncontrollable, racing thoughts about something going wrong

- Avoid situations that could cause anxiety so that feelings and thoughts don’t become consuming

- Think about death , in the sense of fearing death due to the perceived danger of physical symptoms or anticipated dangerous outcomes

Depending on the nature of the anxiety, these mental markers can vary. For example, someone with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) may worry about a variety of topics, events, or activities. A person with social anxiety disorder (SAD) , on the other hand, is more apt to fear negative evaluation or rejection by others and to be apprehensive about meeting new people or other socially challenging situations.

Obsessions are unrealistic thoughts or mental impulses (sometimes with a magical quality) that extend beyond everyday worries. They are the hallmark mental manifestation of anxiety in people with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) .

Simply put, people with anxiety are mentally preoccupied with worry to a degree that is disproportionate with actual risk or reality.

Mental Markers of Depression

People with depression may:

- Be hopeless , assuming that nothing positive will happen in the future for themselves, for others, or for the world

- Believe it is not worth trying to think or feel differently, because of this hopelessness

- Feel worthless , as if who they are or what they do is not valuable

- Think about death due to a persistent belief that life is not worth living or that the individual is a burden on others. In cases of moderate to severe depression, more specific suicidal thoughts can be present.

Have uncontrollable, racing thoughts

Avoid situations that could cause anxiety

Think about death due to perceived danger

Feel hopeless about themselves, others, the world

Believe it is not worth trying

Feel worthless

Think about death due to a persistent belief that life is not worth living

In major depressive disorder (MDD), these types of thoughts are persistent most of the day and more days than not for weeks on end. If a person vacillates between a very low and very high mood state, then a diagnosis of bipolar disorder may apply. For any variant of a mood disorder , the low mood state is likely to be characterized by the type of thinking described above.

If you are having suicidal thoughts, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

Physical Differences: Anxiety vs. Depression

The physical symptoms of both anxiety or depression can be exhausting for the afflicted individual.

Physical Signs of Anxiety

The physical state of anxiety can be conceptualized overall as that of heightened arousal . Specific characteristics include:

- Difficulty concentrating due to state of agitation or racing thoughts

- Difficulty falling or staying asleep due to racing thoughts or other physical symptoms

- Gastrointestinal distress (e.g., nausea, diarrhea, or constipation)

- Increased heart rate, blood pressure, sweating

- Muscle tension

- Shortness of breath

Physical Signs of Depression

Depression is primarily characterized by changes in usual physical processes from baseline, such as:

- Difficulty with concentration, focus, and memory due to ruminative thought processes or other physical symptoms

- Lack of energy

- Loss of appetite or a significant increase in appetite

- Moving or talking more slowly than usual

- Physical achiness without cause

- Sleeping much more or much less than is typical due to ruminative thought processes or low energy

Symptom Severity

It is not unusual to experience brief periods of low mood or anxiety, particularly in response to certain life stressors (for example, loss of a loved one, receiving a diagnosis of a physical illness, starting a new job or school, experiencing financial problems, etc.).

To meet the diagnostic threshold of an anxiety disorder, however, symptoms must be persistent (often for several months) and impairing.

Mood disorders are diagnosed when the associated symptoms occur more often than not for at least a couple of weeks.

To assess the severity of your symptoms:

- Ask yourself some key questions about how much the symptoms are getting in the way of your day-to-day functioning. You might also ask trusted friends and family members if they have noticed changes in you and your behavior, and if so, what those changes are.

- Read about typical presentations of mild, moderate, and severe versions of depression or anxiety.

- Track your psychological and physical symptoms for a week or two to get an accurate representation of fluctuations in mood and anxiety.

Treatment for Anxiety and Depression

Even if you decide that your anxiety or mood problem is a low-grade issue for you, it is still worth working on. Consider how much it is interfering with your life, and in what ways, to determine what kinds of interventions might be helpful.

Self-Help Approaches

If your symptoms are mild, tending to ebb and flow, or if you have had formal treatment previously and are concerned about relapse, self-help interventions can be a reasonable place to start.

These approaches can include self-help books and phone apps that adapt evidence-based psychotherapies or offer a way to practice skills that target a symptom (such as mindfulness meditation for anger or anxiety).

If your symptoms are persistent, are impacting your relationships and ability to fulfill various responsibilities, or are clearly noticeable to others, then more formal treatment is worth considering.

Psychotherapy

For depression and/or anxiety problems, there are several types of talk therapy. In structured psychotherapy, like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), the treatment approach for anxiety and depression can vary slightly. For both issues, CBT will teach you how to work with unhelpful thought traps. And, for either problem, CBT is likely to ask that you do more behaviorally.

For anxiety, the goal is to minimize avoidant behavior and to help you disconfirm a feared consequence. For depression, the goal is to help you experience positive emotion, a surge in energy (even if briefly), or another type of pleasant interaction with the world. The theory is that activating behavior, even when—or especially when—your energy or mood is low, can result in some type of positive reward.

In psychodynamic talk therapy , sessions for anxiety and depression may look more alike than different. You will be asked to speak freely about the past and the present in order to become aware of unconscious thoughts and conflicts underlying your symptoms.

Do not despair if you think you are experiencing separate, co-occurring anxiety and mood symptoms. There is an overlap in effective psychotherapies for these problems.

Medications

A group of medications known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) has been shown to be helpful for both anxiety and depression. Other medications that may be used depending on your symptoms include tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and anti-anxiety medications.

How to Seek Help

When seeking more formalized help for anxiety or depression, start by speaking with your primary care physician.

You can also research local referrals via national organizations including:

- The Anxiety and Depression Association of America

- The Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies

- The Association for Contextual Behavioral Science

- The American Psychiatric Association

Bear in mind that while effective treatment for anxiety or depression need not be a long-term commitment, it is likely to require regular, ongoing appointments at least in the short term (say, six to 12 months). Therefore, it is critical to find a professional you trust and with whom you feel comfortable speaking about your symptoms.

It is equally important to make sure that you find a clinician that you can afford. Before making the commitment to ongoing care, you may want to meet with a couple of providers to get a feel for their therapeutic styles and their treatment recommendations. You can then use this information to determine which path forward feels best to you.

Watson D, Naragon-Gainey K. Personality, emotions, and the emotional disorders . Clin Psychol Sci . 2014;2(4):422-442. doi:10.1177/2167702614536162

Deakin J. The role of serotonin in depression and anxiety . Eur Psychiatry. 1998;13 Suppl 2:57s-63s. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(98)80015-1

Otte C, Gold SM, Penninx BW, et al. Major depressive disorder . Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16065. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.65

Cisler JM, Olatunji BO. Emotion regulation and anxiety disorders . Curr Psychiatry Rep . 2012;14(3):182-187. doi:10.1007/s11920-012-0262-2

Bystritsky A, Khalsa SS, Cameron ME, Schiffman J. Current diagnosis and treatment of anxiety disorders . P T . 2013;38(1):30-57.

David D, Cristea I, Hofmann SG. Why cognitive behavioral therapy is the current gold standard of psychotherapy . Front Psychiatry . 2018;9:4. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00004

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition . Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

By Deborah R. Glasofer, PhD Deborah Glasofer, PhD is a professor of clinical psychology and practitioner of cognitive behavioral therapy.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Anxiety and Depression Overlap: Link Between Comorbid Disorders

- How They Feel

- When Treatment-Resistant

Having depression and anxiety at the same time is somewhat common. Research shows that 60% of people with anxiety will also have symptoms of depression. The rate is the same for those who have depression with symptoms of anxiety.

Anxiety and depression are two distinct conditions that can occur at the same time. This can make symptoms more complex. However, the same treatments can address both problems. They can often improve with psychotherapy (talk therapy), drugs, or both.

This article describes the link between anxiety and depression. It also explains their symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment when they occur at the same time.

MementoJpeg / Getty Images

Anxiety and Depression: An Indirect or Direct Link?

The relationship between anxiety and depression is complex. While depression is typically regarded as a low-energy condition and anxiety a high-energy condition, these disorders and their symptoms commonly occur together. The reason they are often linked is well understood, though several potential factors exist.

Many of the same factors that predispose you to anxiety also make you vulnerable to depression. Both are considered internalizing disorders, problems that are developed and maintained to a great extent within the affected person.

Like other internalizing disorders, anxiety and depression are linked to similar factors that include genetic risk and neuroticism (the tendency toward negative thoughts). They are also associated with several shared nongenetic risk factors such as early trauma and current stress.

Anxiety and depression have many overlapping symptoms because they both involve changes in the function of neurotransmitters like serotonin in your brain. Your symptoms may meet the criteria of both disorders.

The relationship between anxiety and depression may not be a situation in which one causes the other, but the fact that they may be two sides of the same coin. Being depressed can often make you feel worried or anxious. Similarly, having an anxiety attack can make you feel hopeless with depression.

Related Causes/Risk Factors

While the exact causes of comorbid depression and anxiety are not known, the following risk factors increase your chances of having these disorders together:

- Lifetime history of anxiety or depression

- Adversity during childhood

- Poor parenting

- Recent major life events

- Current exposure to stress

- High neuroticism

- Substance use disorders

- Family history

How Anxiety and Depression Symptoms Feel

Symptoms of anxiety and depression can vary by individual. However, both disorders can cause symptoms that can interfere with daily life and interpersonal relationships.

Similarities

Symptoms common in both anxiety and depression include:

- Problems with digestion

- Unintended changes in appetite or weight

- Inability to concentrate or make decisions

- Problems sleeping, either too much or too little

- Feeling constantly restless or irritable

Differences

Worrying is normal in some situations. Anxiety differs from normal worrying because it involves excessive fear that can be debilitating. Symptoms that may be characteristic of anxiety include:

- Constantly feeling wound up or restless

- Ongoing excessive worry about the immediate or long-term future

- Focusing on negative outcomes when decision-making

- Uncontrollable, racing thoughts about something going wrong

- Avoiding situations that could cause worry and anxiety

- Feeling a lack of certainty

The key characteristics of depression involve a persistent feeling of extremely low mood and/or loss of interest in activities you once enjoyed. Symptoms that may be characteristic of depression include:

- Feelings of sadness and persistent low mood

- Lack of interest or enjoyment in life experiences

- Loss of energy or extreme fatigue

- Increase in purposeless physical activities such as hand-wringing that is noticeable to others

- Increase in slowed movements or speech that occur often enough to be noticed by others

- Feelings of worthlessness or guilt

- Emphasis on loss or deprivation

- Thoughts of death or suicide

Help Is Available

If you or someone you know is having suicidal thoughts, call or text 988 to contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline and connect with a trained counselor. If you or they are in immediate danger, dial 911 .

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

Anxiety, Depression, or Both: How to Diagnose Symptoms

Many symptoms of anxiety and depression overlap, making it harder to determine which disorder is causing the problem. When anxiety and depression occur together, symptoms tend to be more intense and persistent because they work together. This can make your condition harder to diagnose and more complex to treat.

Diagnosing symptoms of a mental health disorder requires a comprehensive evaluation by a mental health provider. This can help ensure you get an accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Symptoms that might indicate that both anxiety and depression exist include:

- Persistent irrational fears or worries

- Physical symptoms like fatigue, headaches , labored breathing , abdominal pain , or rapid heartbeat

- Persistent feelings of worthlessness or sadness

- Problems going to sleep or staying asleep

- Difficulty remembering or concentrating

- Inability to make decisions

- Loss of interest in hobbies or activities

- Constantly feeling tired and cranky

- Panic attacks or a sense of losing inner control

- Inability to live in the moment and relax

Role of Gut Microbiome

Gut microbiome includes all the microorganisms living in your digestive system. It affects your digestive health as well as your overall health.

Research indicates that there is evidence of a link between gut microbes and depression. It is attributed to the gut and brain connection, called the gut-brain axis. Evidence shows that inflammation caused by gut microbes can influence mood in depression.

How to Cope With Comorbid Anxiety and Depression

There is no single treatment appropriate for every case of comorbid (co-occurring) anxiety and depression. Therapies typically include antidepressant drugs and/or a form of psychotherapy. Self-care can help you maintain your progress.

While research indicates that a combination of medication and therapy can provide the best results, your treatment plan may differ. Depending on your symptoms, you may be advised to start your treatment with either one of these therapies.

Self-care includes behaviors that support your physical and mental well-being. It involves actions that can help manage symptoms of anxiety and/or depression and complement therapy and/or medications.

The following strategies are ways to prioritize self-care:

- Establish and maintain a regular exercise routine with a target of 30 minutes daily. Exercising for smaller amounts of time can also make a difference.

- Follow a diet of nutritious meals and adequate hydration. Limit caffeinated beverages, alcohol, and added sugar.

- Maintain proper sleep hygiene , which involves following a daily sleep schedule and other behaviors supporting a good night's sleep.

- Try activities that involve relaxation, meditation, and breathing exercises to relieve stress and reduce feelings linked with anxiety and depression.

- Remain connected with friends or family members you can count on to provide practical help and emotional support if needed.

- Practice gratitude by journaling to remind yourself of the positive things in your life.

- Establish goals and priorities to avoid taking on new tasks and responsibilities that can overwhelm you.

Therapy is regarded as a key part of treatment for symptoms that involve anxiety and/or depression. Your results and the time it takes to achieve them depend on your symptoms and your unique situation.

The following types of therapy are used to treat anxiety and depression:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) : This type of psychotherapy is considered the gold standard for treating anxiety and depression, among other mental health conditions.

- CBT is a time-limited and goal-oriented therapy. It focuses on changing negative thought patterns by altering negative behaviors and emotions.

- Interpersonal therapy (IPT) : This type of time-limited psychotherapy helps you see emotions as social signals so you can use them to improve interpersonal challenges. Rather than focusing on your past, IPT focuses on communication and current interpersonal relationships and issues you're having related to them.

- Dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) : DBT is a modified version of CBT that focuses on healthy ways to live in the moment, regulate emotions, and improve interpersonal relationships. It integrates mindfulness skills, interpersonal effectiveness, distress tolerance, and emotion regulation into treatment.

- Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) : ACT is a type of psychotherapy that focuses on mindfulness, remaining in the present, and strategies for behavioral changes. It focuses on helping you become psychologically flexible so you can accept difficult thoughts and emotions while committing to meaningful life activities consistent with your goals and values.

With Medication

Medication for anxiety and/or depression works by increasing the activity of neurotransmitters, like serotonin , dopamine , norepinephrine , and gamma-aminobutyric acid ( GABA ). These are the chemical messengers in your brain that affect mood regulation.

The type of medication you receive depends on your symptoms and other factors regarding your overall condition. The following classes of medications are commonly used:

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) : SSRIs are the first-line treatments preferred for treating depression and many comorbid anxiety disorders. They work by increasing serotonin levels.

SSRIs include:

- Celexa ( citalopram )

- Lexapro ( escitalopram )

- Paxil ( paroxetine )

- Prozac ( fluoxetine )

- Zoloft ( sertraline )

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) : SNRIs increase levels of serotonin and norepinephrine. These drugs are also acceptable first-line treatments for comorbid anxiety and depression.

SNRIs include:

- Effexor ( venlafaxine )

- Pristiq ( desvenlafaxine )