What is the Essay Method for Performance Appraisals?

While some would label it as the “grandfather” of performance appraisal methods, the essay method is still a commonly used appraisal method in a variety of business models. The essay method, sometimes known as the “free-form method,” is a performance review system where a superior creates a written review of the employee’s performance.

These essays are meant to describe and record an employee’s strengths and weaknesses in job performance, identifying problem areas and creating a plan of action to remedy them. Whether the essay is written by the appraiser alone, or in collaboration with the appraisee, essays provide supervisors the opportunity to assess behaviors and performance with greater complexity and attention to detail.

There are many reasons that the essay method--which was one of the first methods used to evaluate performance--is still effective today.

One of the most noteworthy aspects of essay appraisals is their free-form approach to performance reviews. Whereas some employers can feel limited by rigid performance appraisal criteria, the essay method takes a far less structured stance than typical rating scale methods. In so doing, the appraiser is able to examine any relevant issue or attribute of performance that is pertinent to an employee’s job description or overall company growth.

The essay method assumes that not all employee traits and behaviors can be neatly analyzed, dissected, and rated--instead, it allows appraisers to place varied degrees of emphasis on certain qualities, issues, or attributes that are appropriate. Rather than being locked into a fixed system, this open-ended method gives supervisors the freedom of expression and critical thought. For appraisers, there exist special services such as StudyCrumb , which help in writing accurate essays.

When preparing an essay, a supervisor may consider any of the following factors of an employee as they relate to the company and employee relationship: potential and job knowledge, understanding of the company’s policies, relationships with peers and supervisors, planning and organization, and general attitudes and perceptions. This thorough, non-quantitative assessment provides a good deal more information about an employee than most other performance appraisal techniques.

However, as with all performance appraisal methods, there are a few limitations that the essay method suffers from that are worth examining.

One of the major drawbacks of the essay method is its highly subjective nature--they are often subject to bias, and it can be difficult to separate the assessment of the employee from the bias of the evaluator. While the essay can provide a good deal of information about the employee, it tends to tell more about the evaluator than the one being evaluated.

Another element that essays leave out (that other appraisal methods rely heavily on) is comparative results. Instead of utilizing standardized, numeric questions, these appraisals rely only on open-ended questions. While the essay method gives managers the ability to provide detailed and circumstantial information on a specific employee’s performance, it removes the component of comparing performance with other employees. This often makes it difficult for HR to distinguish top performers.

Overall, the appraisal method’s greatest advantage--the freedom of expression for the evaluator--can also serve as its greatest handicap. Even the actual writing of the reviews can upset or distort the process of employee appraisals, as the introduction of inconsistent, unorganized, or poor writing styles can distort and upset the review process. An employee may be unfairly helped or harmed by an evaluator’s writing ability. An evaluator can also find themselves lacking sufficient time to prepare the essay, and can write an essay hurriedly without accurately assessing an employee’s performance.

What is the essay method best used for?

Appraisal by essay is generally most effective in performance reviews for employees with atypical job descriptions or non-numerical goals. While other appraisals work well in analyzing performance for jobs that are subject to goals based on numbers, essays offer a more subjective analysis of performance for employees with managerial or customer service positions.

When analyzing production, the essay method is most effective in combination with another appraisal method. Using a graphic rating scale along with essay appraisals allows one method to focus solely on numbers, while the essay portion can be used to analyze other performance goals.

Doing essay appraisals right

Here are 3 things to strive for in order to set your company up for success in essay performance appraisals:

- Consistency.

Keeping a standard for style and length of essay appraisals can make the biggest difference in ensuring that your reviews are effective. Essays that are unstructured and unnecessarily complex can be detrimental to an employee’s rating, as well as using unspecific, flowery language that is not relevant to the employee’s performance. In order to remain efficient and effective, today’s evaluators should focus on making appraisal essays short and specific, ensuring that the entire review reflects the performance of the employee.

The appraiser should also ensure that they are making sufficient time in their schedule to prepare the essay. A busy evaluator may compromise an employee’s performance rating by writing a hurried essay, or running out of time to thoroughly assess employee performance. It’s important for all participants of essay appraisals to take enough time to write a consistent, accurate, and succinct review in order to set employees up for success.

2. Proficiency.

If you’ve chosen to use essay appraisals in your organization, it’s important to ensure that your appraisers possess the ability to write well. Even if an essay contains detailed, circumstantial information, it becomes difficult to extract valuable data from a poorly written essay. To ensure that nothing stands between an HR professional’s ability to assess an employee’s performance, evaluators should be trained as well-equipped writers.

Giving writing assistant tools or tips to supervisors can make all the difference in the accuracy and efficiency of an employee’s performance review.

2. Objectivity.

Subjectivity is both a strength and a weakness in essay appraisals. Not only are essays themselves often biased, but the misinterpretation of essays can even further distance the main evaluator from an accurate portrayal of an employee’s performance. Including objective standards in a performance review results in a more balanced and productive review process, and helps to eliminate the forming of incorrect conclusions about an employee’s behavior and performance.

Organizations often implement this goal by pairing essay appraisals with another appraisal method, such as graphic scale ratings, to draw more accurate conclusions and performance data. In so doing, evaluators can utilize all of the free expression and open-ended characteristics of an essay appraisal, while still maintaining accurate, easily translated results that are effective for the overall organization.

The tools to streamline your performance management process.

Bring your performance management to life.

.jpeg)

The 2024 HR Guide to the Skip Level Meeting

5 Steps to Deliver Positive Feedback to an Employee

Behavioral Observation Scales | Definition, Tips and Examples

The Essay Method of Performance Appraisal

by Danielle Smyth

Published on 9 Aug 2019

The question of how to effectively gauge an employee’s performance on the job has been answered many times in many different ways, but there’s certainly no one agreed-upon method recommended by the human resources industry. Most experts agree that performance management is a critical part of having a successful business in today’s world and that effectively managing, developing and evaluating employees leads to a more efficient workforce and better company culture.

However, it’s deciding how to implement it within a certain company structure that can be challenging, and implementation is key to keeping the process effective rather than disruptive. The essay method of performance appraisal can be a great choice due to its thorough, thoughtful and unobtrusive nature.

Secrets to Effective Performance Appraisals

The truth is that effective performance appraisals take time. They take up the manager’s time, the employee’s time and the time of human resources, and they can potentially take up the time of teammates and co-workers who are asked about projects and collaboration.

For them to mean something, the process needs to be taken seriously, but that always must be balanced against the forward motion of the company and the day-to-day workloads of the employees in question.

Methods of Performance Appraisal

There are a number of methods used in today’s industries to evaluate employees. All of them require some sort of performance standard to be set at first and then an evaluation over a set period of time against that standard.

Some methods of review can be more effective than others, but some also require more dedicated time and thought from the manager or other evaluator. Some of the more common methods include the checklist method, the comparison or forced distribution method and the essay method.

Checklist Method of Performance Appraisal

With the checklist method, an employee is judged against a list of criteria. The criteria have been developed for the level or job of the employee, and usually all employees at similar levels are evaluated against it.

- Yes/no checklists simply ask the evaluator to determine whether the employee exhibits the behavior defined in each criterion: for example, “comes to work on time,” “frequently contributes to group discussions” or “meets daily safety requirements.” It’s important to make sure that all criteria are phrased so that a "yes" is the desired answer because it can be very easy to confuse an evaluation when this isn’t the case. This provides a very simple and straightforward way of judging performance but won’t get into much nuance of individual strengths and weaknesses and may not do much to differentiate one employee from another.

- Leveled checklists ask the evaluator to rate the employee on some sort of scale for each criterion. This could be a scale from one to five where five is optimal, or it could be a verbal scale with levels like “needs improvement,” “meets expectations” and “exceeds expectations.” Criteria might be “completes work within the timeline,” “collaborates with other departments” or “shows technical expertise.” These scaled ratings provide more nuance into each individual employee and should help highlight strengths as well as areas for improvement, but they require the manager to take more time to understand the performance within the department.

Comparison or Forced Distribution Methods

Comparison or forced distribution methods rate employees comparatively and against each other. This can be done in cases where an organization is rather flat, and it makes sense to compare a collection of employees together. The downside is that it can create a false sense of competition within employee groups or can result in bad attitudes.

- Paired evaluations give the evaluator a set of employee comparisons and asks him to choose who is the better employee. This is normally done within a department. For example, a department of four employees would end up with six pairs for comparison, and the evaluator (or team) would then select the best employee within each pair. For larger departments, this can be time consuming for the evaluators.

- Rankings simply ask the evaluator to rank employees from best to worst. This method is fully based on the perception of the evaluator and is not entirely popular because it is not systematic and can be easily affected by undiscovered bias on the part of the evaluator. It is, however, relatively easy to do for any manager who knows the team well.

- Forced distribution methods focus on the fact that most evaluators tend to rate their employees well. It requires the evaluators to meet a set distribution within their evaluations such that each evaluation finds poor performers as well as excellent ones. While this can be a way to identify areas for improvement, it can also be read as having to meet a quota with ratings, which can lead to dissent.

Essay Evaluation Method

The essay method is a fairly straightforward approach in which the manager or evaluator writes a descriptive essay about each employee. The essay would cover the employees' achievements throughout the evaluation period as well as their strengths and weaknesses. The essay format gives the evaluators the flexibility to focus on whatever they personally find important about the individual’s performance.

However, the essay method can be time consuming for the manager, and it requires a certain level of writing skill for the evaluation to be meaningful. It also is unlikely to be systematic, which can make it difficult to compare evaluations from person to person.

Performance Appraisal Essays

The performance evaluation essay is maybe the most interesting of the methods, as it allows a manager to genuinely express thoughts about the employee in question rather than having to work with a template or list of criteria or comparisons.

There are advantages to this, mainly in allowing the appraisers to focus on what they feel is important for each individual whom they are evaluating. The downside of this apparent freedom is because the entire essay is subjective based on the evaluator’s approach, it becomes difficult to obtain any big-picture conclusions about the department, and it can be difficult to compare employees within a certain group.

The key to a successful performance appraisal essay is the writing skills of the person assembling it . Her attention to basic essay structure and her descriptions of the behaviors on which she focuses will determine whether the right message will get across during the evaluation, both to the employee and to the team of other managers and human resources employees who may be involved with ratings, promotions and improvement plans. Some attention to basic essay-writing principles should help the evaluator construct an essay that will be meaningful to all parties involved.

" id="basic-essay-writing " class="title"> Basic Essay Writing

The following are essential to the writing of an effective performance appraisal essay:

- Preparation: For any essay, the first step is to gather information about the topic at hand. In this case, the manager should take the time to review past performance, current expectations and future needs for each employee whom he intends to evaluate. Review the employee’s achievements this year and examine reports and project records to get a full picture of performance.

- Evaluation: Once the information is at hand, it’s important to spend time connecting the dots to figure out what story the essay needs to tell about the employee’s performance. Identify any changes in the employee’s performance over the evaluation period and establish a list containing the behaviors that have been commendable and in which areas the employee could use improvement.

- Creation: Construct the essay in a manner that suits the manager’s writing style. Be sure to use professional, fair language and describe in words the successes and challenges of the employee’s work over this time period.

Writing the Essay

The essay should open with an introduction summarizing the work completed by the employee during the evaluation period. Be sure to note key projects and pay attention to ongoing work as well as completed jobs. This is the time to discuss what the employee has done and recognize his overall contribution to the business. For example:

Jon successfully supported the infrastructure team, the McAce project and the office renovations project with technical drawings and materials lists as requested. He personally was able to complete the ventilation upgrade project, which ran over schedule but came in under budget. He submitted all monthly reports on time and took a training course this year to improve his skills at AutoCAD.

Highlight Employee Successes

The next portion of the essay should highlight some real successes for the employee. Mention his strengths and any areas where he has shown visible improvement over past performance. In this portion, focus less on what was done and more on how it was done. To continue the example:

Jon’s skill at estimation has improved greatly over the past year, with only one of his personal projects running over budget (as compared to at least 50 percent the previous year). This makes it much easier for the department to manage our overall budget appropriately and is greatly appreciated. Jon has been described as “friendly” and “personable” by his teammates, who have no problem approaching him when they need a drawing or have a question. He also had huge success with his contributions to the McAce project, which would have fallen behind schedule without his work.

Outline Areas for Improvement

After calling out successes, take some time to consider areas in which the employee needs improvement. For employees currently meeting all expectations, consider their future career path: Are there areas they need to develop in order to move into a new position? For employees whose performance may not be up to par, try to address it fairly and be straightforward and logical.

A number of Jon’s projects ran over schedule this year. It appears that Jon’s technical understanding of the work at hand could perhaps use some development. One such corrective action might be making sure to check with operators and maintenance personnel before launching a new project concept to make sure the problem at hand is actually being solved. Also, while Jon’s open personality makes him approachable, it can also lead to Jon taking extra-long breaks for conversation throughout the day, which can disturb some employees from their work.

Note that the criticisms are couched calmly in specific language that isn’t accusatory or angry and that the behaviors described correlate to an undesirable outcome. In some cases, a corrective action should be suggested. In other cases, it’s best to wait until the final step and develop a path forward with the employee in question.

" id="create-a-forward-plan " class="title"> Create a Forward Plan

The essay should end with a forward plan for the employee, involving any additional training or development she may need to meet current expectations as well as some sort of idea of the next step in her career.

The final step in the performance assessment essay is, of course, reviewing the essay with each employee. It’s best to give the employee a chance to read the evaluation and then open the floor to any questions the employee might have about what’s been written.

If an employee wants to challenge an assertion, she can be encouraged to write a short essay in return discussing why she might disagree with the essay. It’s important to discuss the successes and give recognition where it’s due as well as the challenges in order to ensure the employee understands.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.2 Appraisal Methods

Learning objective.

- Be able to describe the various appraisal methods.

It probably goes without saying that different industries and jobs need different kinds of appraisal methods. For our purposes, we will discuss some of the main ways to assess performance in a performance evaluation form. Of course, these will change based upon the job specifications for each position within the company. In addition to industry-specific and job-specific methods, many organizations will use these methods in combination, as opposed to just one method. There are three main methods of determining performance. The first is the trait method , in which managers look at an employee’s specific traits in relation to the job, such as friendliness to the customer. The behavioral method looks at individual actions within a specific job. Comparative methods compare one employee with other employees. Results methods are focused on employee accomplishments, such as whether or not employees met a quota.

Within the categories of performance appraisals, there are two main aspects to appraisal methods. First, the criteria are the aspects the employee is actually being evaluated on, which should be tied directly to the employee᾿s job description. Second, the rating is the type of scale that will be used to rate each criterion in a performance evaluation: for example, scales of 1–5, essay ratings, or yes/no ratings. Tied to the rating and criteria is the weighting each item will be given. For example, if “communication” and “interaction with client” are two criteria, the interaction with the client may be weighted more than communication, depending on the job type. We will discuss the types of criteria and rating methods next.

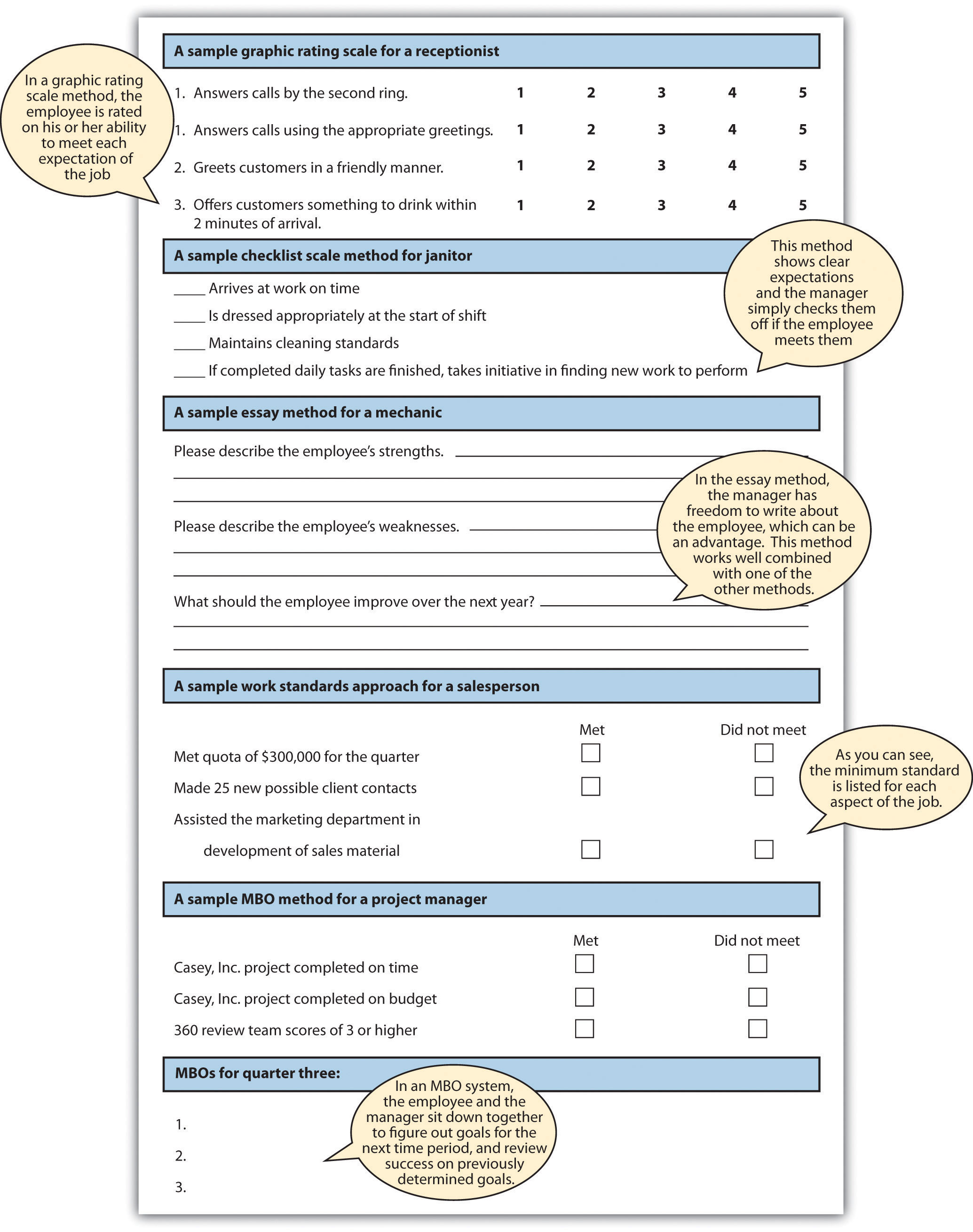

Graphic Rating Scale

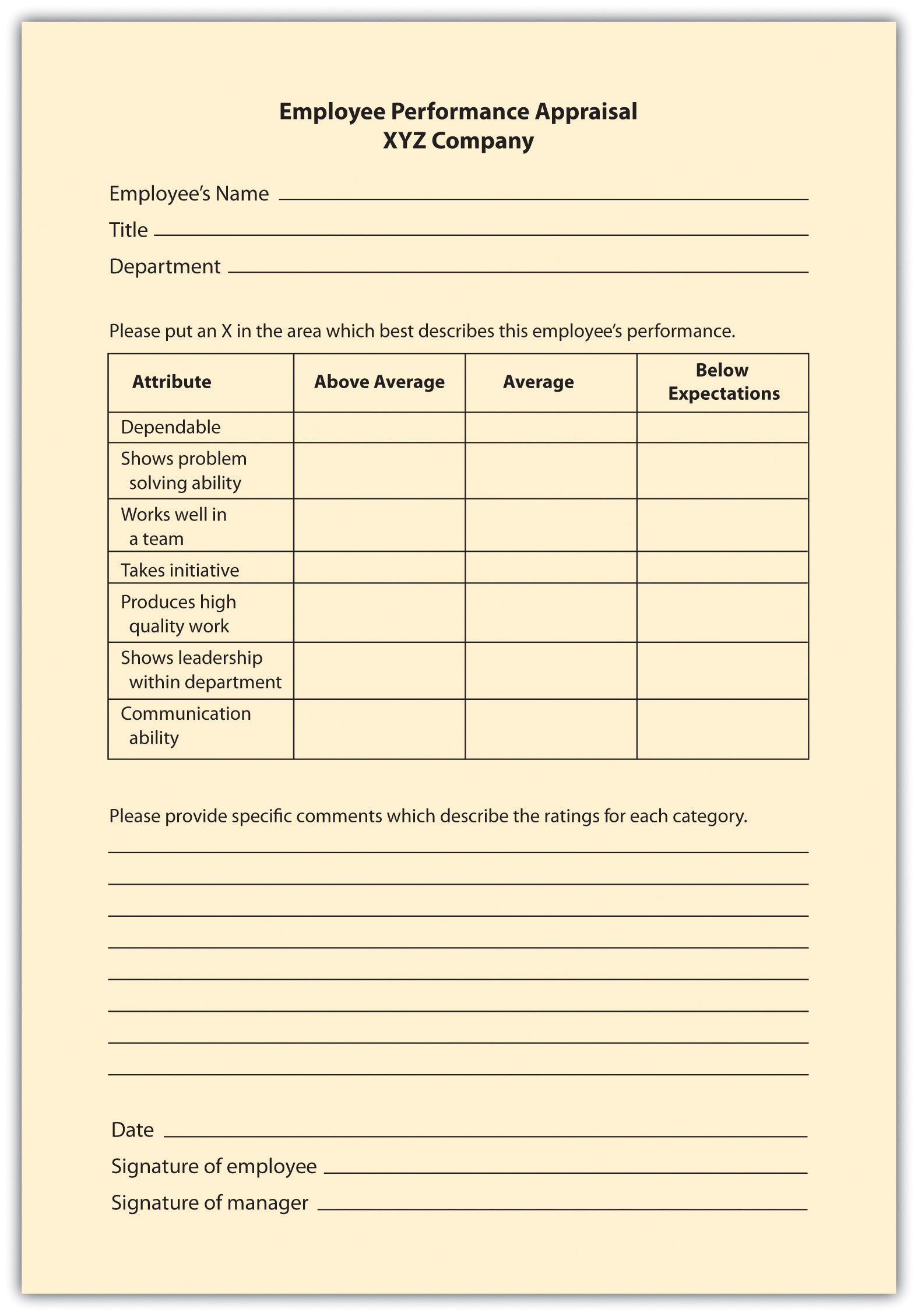

The graphic rating scale , a behavioral method, is perhaps the most popular choice for performance evaluations. This type of evaluation lists traits required for the job and asks the source to rate the individual on each attribute. A discrete scale is one that shows a number of different points. The ratings can include a scale of 1–10; excellent, average, or poor; or meets, exceeds, or doesn’t meet expectations, for example. A continuous scale shows a scale and the manager puts a mark on the continuum scale that best represents the employee’s performance. For example:

The disadvantage of this type of scale is the subjectivity that can occur. This type of scale focuses on behavioral traits and is not specific enough to some jobs. Development of specific criteria can save an organization in legal costs. For example, in Thomas v. IBM , IBM was able to successfully defend accusations of age discrimination because of the objective criteria the employee (Thomas) had been rated on.

Many organizations use a graphic rating scale in conjunction with other appraisal methods to further solidify the tool’s validity. For example, some organizations use a mixed standard scale , which is similar to a graphic rating scale. This scale includes a series of mixed statements representing excellent, average, and poor performance, and the manager is asked to rate a “+” (performance is better than stated), “0” (performance is at stated level), or “−” (performance is below stated level). Mixed standard statements might include the following:

- The employee gets along with most coworkers and has had only a few interpersonal issues.

- This employee takes initiative.

- The employee consistently turns in below-average work.

- The employee always meets established deadlines.

An example of a graphic rating scale is shown in Figure 11.1 “Example of Graphic Rating Scale” .

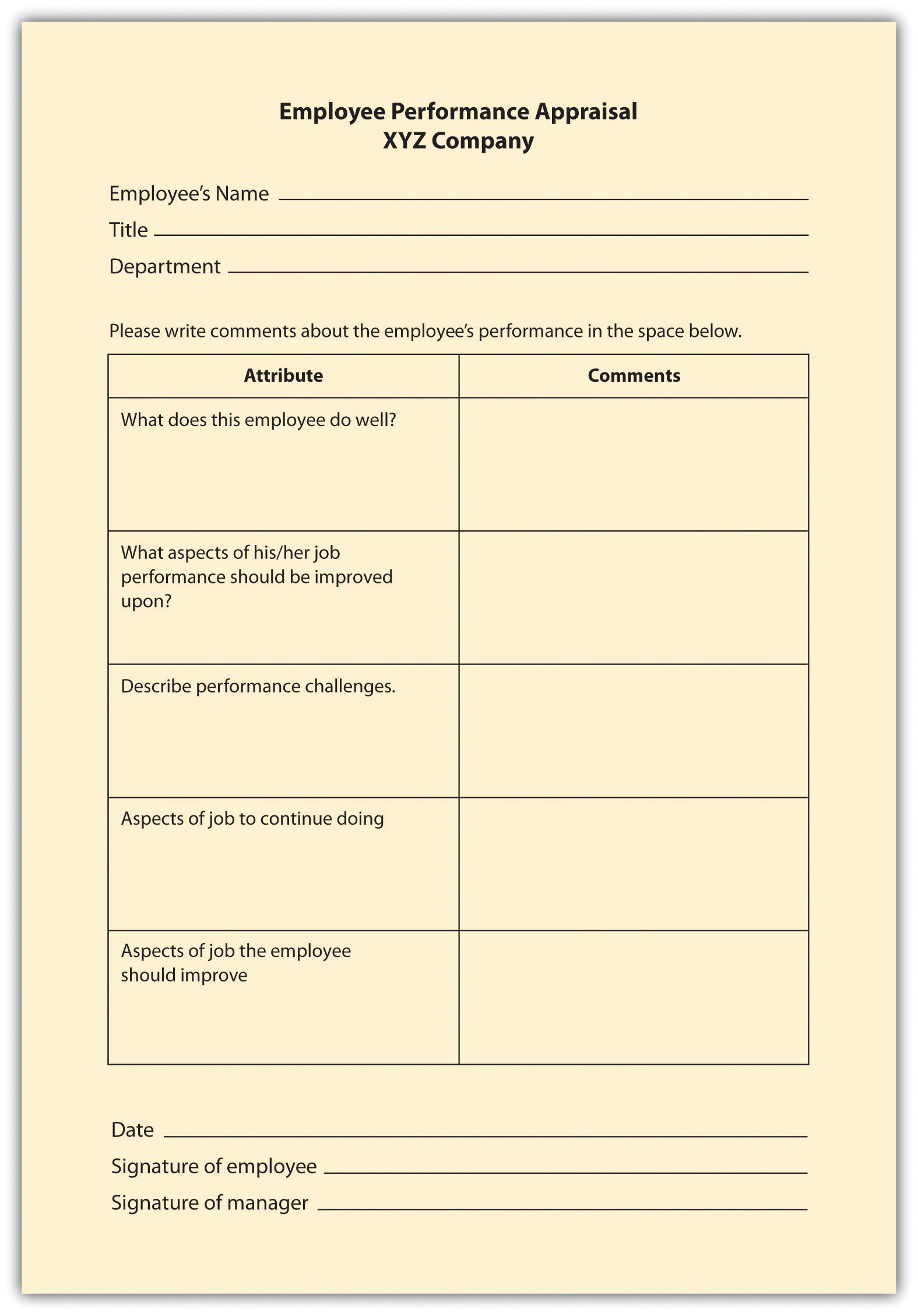

Essay Appraisal

In an essay appraisal , the source answers a series of questions about the employee’s performance in essay form. This can be a trait method and/or a behavioral method, depending on how the manager writes the essay. These statements may include strengths and weaknesses about the employee or statements about past performance. They can also include specific examples of past performance. The disadvantage of this type of method (when not combined with other rating systems) is that the manager’s writing ability can contribute to the effectiveness of the evaluation. Also, managers may write less or more, which means less consistency between performance appraisals by various managers.

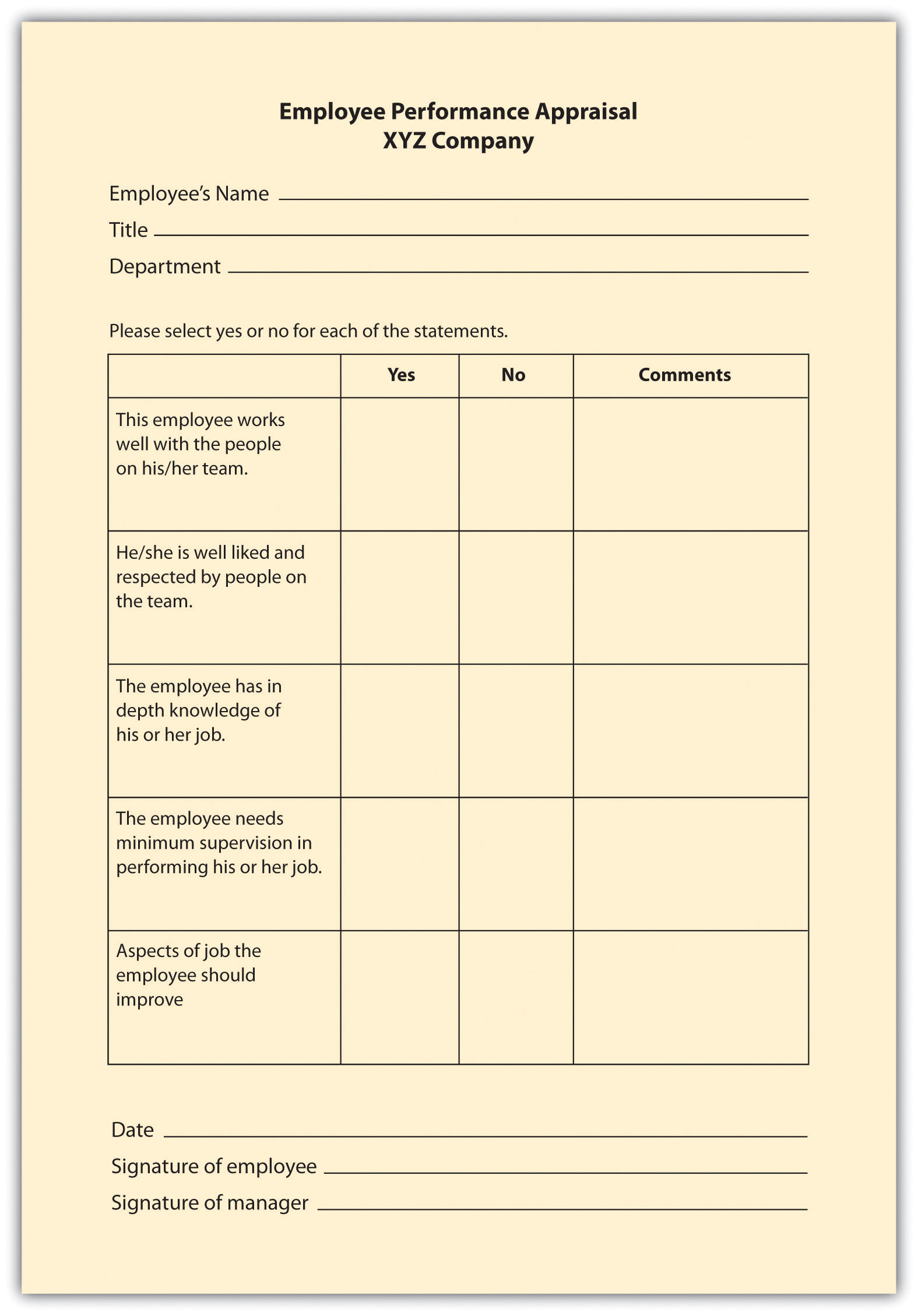

Checklist Scale

A checklist method for performance evaluations lessens the subjectivity, although subjectivity will still be present in this type of rating system. With a checklist scale , a series of questions is asked and the manager simply responds yes or no to the questions, which can fall into either the behavioral or the trait method, or both. Another variation to this scale is a check mark in the criteria the employee meets, and a blank in the areas the employee does not meet. The challenge with this format is that it doesn’t allow more detailed answers and analysis of the performance criteria, unless combined with another method, such as essay ratings. A sample of a checklist scale is provided in Figure 11.3 “Example of Checklist Scale” .

Figure 11.1 Example of Graphic Rating Scale

Figure 11.2 Example of Essay Rating

Figure 11.3 Example of Checklist Scale

Critical Incident Appraisals

This method of appraisal, while more time-consuming for the manager, can be effective at providing specific examples of behavior. With a critical incident appraisal , the manager records examples of the employee’s effective and ineffective behavior during the time period between evaluations, which is in the behavioral category. When it is time for the employee to be reviewed, the manager will pull out this file and formally record the incidents that occurred over the time period. The disadvantage of this method is the tendency to record only negative incidents instead of postive ones. However, this method can work well if the manager has the proper training to record incidents (perhaps by keeping a weekly diary) in a fair manner. This approach can also work well when specific jobs vary greatly from week to week, unlike, for example, a factory worker who routinely performs the same weekly tasks.

Work Standards Approach

For certain jobs in which productivity is most important, a work standards approach could be the more effective way of evaluating employees. With this results-focused approach, a minimum level is set and the employee’s performance evaluation is based on this level. For example, if a sales person does not meet a quota of $1 million, this would be recorded as nonperforming. The downside is that this method does not allow for reasonable deviations. For example, if the quota isn’t made, perhaps the employee just had a bad month but normally performs well. This approach works best in long-term situations, in which a reasonable measure of performance can be over a certain period of time. This method is also used in manufacuring situations where production is extremely important. For example, in an automotive assembly line, the focus is on how many cars are built in a specified period, and therefore, employee performance is measured this way, too. Since this approach is centered on production, it doesn’t allow for rating of other factors, such as ability to work on a team or communication skills, which can be an important part of the job, too.

Ranking Methods

In a ranking method system (also called stack ranking), employees in a particular department are ranked based on their value to the manager or supervisor. This system is a comparative method for performance evaluations.The manager will have a list of all employees and will first choose the most valuable employee and put that name at the top. Then he or she will choose the least valuable employee and put that name at the bottom of the list. With the remaining employees, this process would be repeated. Obviously, there is room for bias with this method, and it may not work well in a larger organization, where managers may not interact with each employee on a day-to-day basis.

To make this type of evaluation most valuable (and legal), each supervisor should use the same criteria to rank each individual. Otherwise, if criteria are not clearly developed, validity and halo effects could be present. The Roper v. Exxon Corp case illustrates the need for clear guidelines when using a ranking system. At Exxon, the legal department attorneys were annually evaluated and then ranked based on input from attorneys, supervisors, and clients. Based on the feedback, each attorney for Exxon was ranked based on their relative contribution and performance. Each attorney was given a group percentile rank (i.e., 99 percent was the best-performing attorney). When Roper was in the bottom 10 percent for three years and was informed of his separation with the company, he filed an age discrimination lawsuit. The courts found no correlation between age and the lowest-ranking individuals, and because Exxon had a set of established ranking criteria, they won the case (Grote, 2005).

Another consideration is the effect on employee morale should the rankings be made public. If they are not made public, morale issues may still exist, as the perception might be that management has “secret” documents.

Fortune 500 Focus

Critics have long said that a forced ranking system can be detrimental to morale; it focuses too much on individual performance as opposed to team performance. Some say a forced ranking system promotes too much competition in the workplace. However, many Fortune 500 companies use this system and have found it works for their culture. General Electric (GE) used perhaps one of the most well-known forced ranking systems. In this system, every year managers placed their employees into one of three categories: “A” employees are the top 20 percent, “B” employees are the middle 70 percent, and “C” performers are the bottom 10 percent. In GE’s system, the bottom 10 percent are usually either let go or put on a performance plan. The top 20 percent are given more responsibility and perhaps even promoted. However, even GE has reinvented this stringent forced ranking system. In 2006, it changed the system to remove references to the 20/70/10 split, and GE now presents the curve as a guideline. This gives more freedom for managers to distribute employees in a less stringent manner 1 .

The advantages of a forced ranking system include that it creates a high-performance work culture and establishes well-defined consequences for not meeting performance standards. In recent research, a forced ranking system seems to correlate well with return on investment to shareholders. For example, the study (Sprenkel, 2011) shows that companies who use individual criteria (as opposed to overall performance) to measure performance outperform those who measure performance based on overall company success. To make a ranking system work, it is key to ensure managers have a firm grasp on the criteria on which employees will be ranked. Companies using forced rankings without set criteria open themselves to lawsuits, because it would appear the rankings happen based on favoritism rather than quantifiable performance data. For example, Ford in the past used forced ranking systems but eliminated the system after settling class action lawsuits that claimed discrimination (Lowery, 2011). Conoco also has settled lawsuits over its forced ranking systems, as domestic employees claimed the system favored foreign workers (Lowery, 2011). To avoid these issues, the best way to develop and maintain a forced ranking system is to provide each employee with specific and measurable objectives, and also provide management training so the system is executed in a fair, quantifiable manner.

In a forced distribution system, like the one used by GE, employees are ranked in groups based on high performers, average performers, and nonperformers. The trouble with this system is that it does not consider that all employees could be in the top two categories, high or average performers, and requires that some employees be put in the nonperforming category.

In a paired comparison system, the manager must compare every employee with every other employee within the department or work group. Each employee is compared with another, and out of the two, the higher performer is given a score of 1. Once all the pairs are compared, the scores are added. This method takes a lot of time and, again, must have specific criteria attached to it when comparing employees.

Human Resource Recall

How can you make sure the performance appraisal ties into a specific job description?

Management by Objectives (MBO)

Management by objectives (MBOs) is a concept developed by Peter Drucker in his 1954 book The Practice of Management (Drucker, 2006). This method is results oriented and similar to the work standards approach, with a few differences. First, the manager and employee sit down together and develop objectives for the time period. Then when it is time for the performance evaluation, the manager and employee sit down to review the goals that were set and determine whether they were met. The advantage of this is the open communication between the manager and the employee. The employee also has “buy-in” since he or she helped set the goals, and the evaluation can be used as a method for further skill development. This method is best applied for positions that are not routine and require a higher level of thinking to perform the job. To be efficient at MBOs, the managers and employee should be able to write strong objectives. To write objectives, they should be SMART (Doran, 1981):

- Specific. There should be one key result for each MBO. What is the result that should be achieved?

- Measurable. At the end of the time period, it should be clear if the goal was met or not. Usually a number can be attached to an objective to make it measurable, for example “sell $1,000,000 of new business in the third quarter.”

- Attainable. The objective should not be impossible to attain. It should be challenging, but not impossible.

- Result oriented. The objective should be tied to the company’s mission and values. Once the objective is made, it should make a difference in the organization as a whole.

- Time limited. The objective should have a reasonable time to be accomplished, but not too much time.

Setting MBOs with Employees

(click to see video)

An example of how to work with an employee to set MBOs.

To make MBOs an effective performance evaluation tool, it is a good idea to train managers and determine which job positions could benefit most from this type of method. You may find that for some more routine positions, such as administrative assistants, another method could work better.

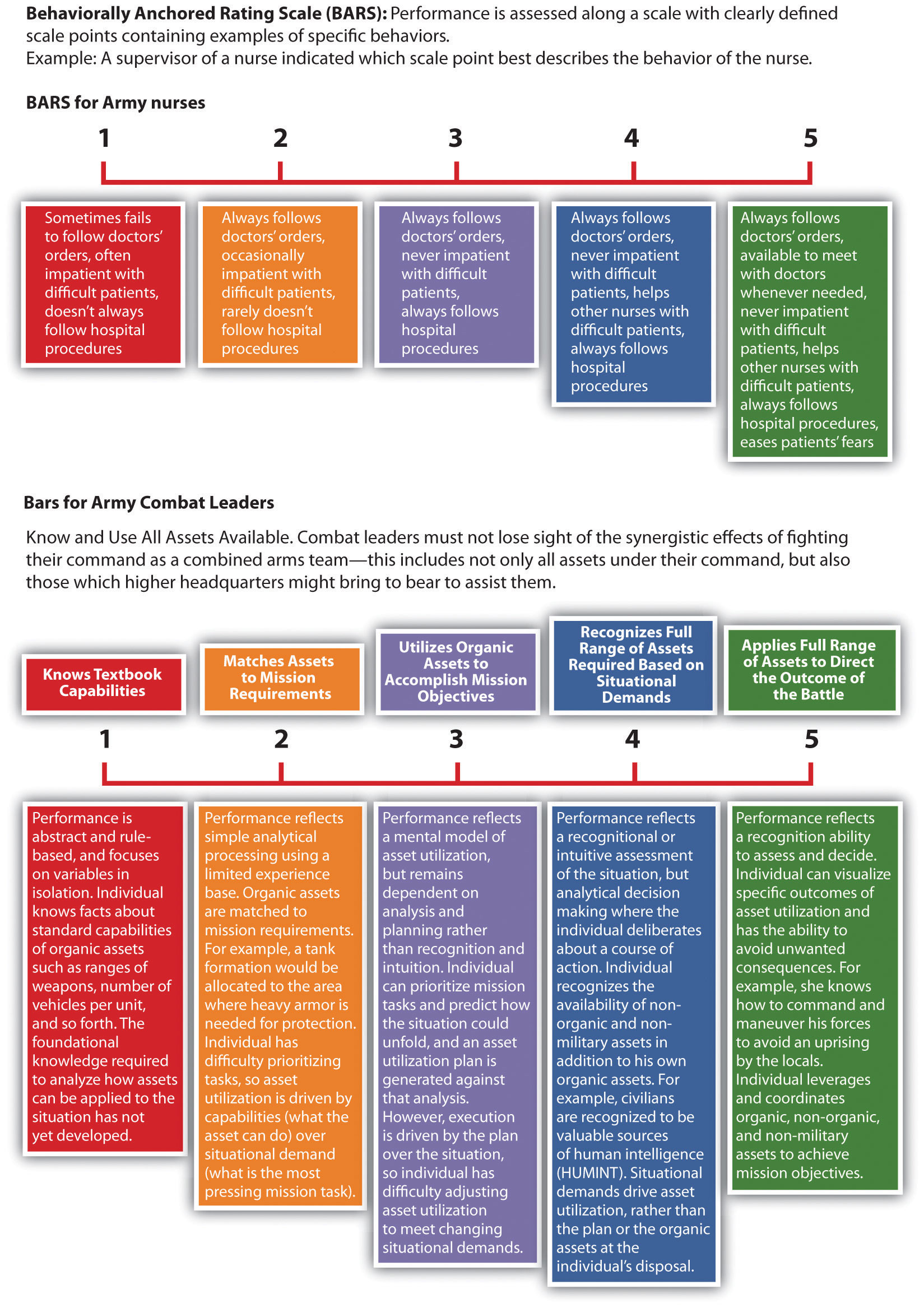

Behaviorally Anchored Rating Scale (BARS)

A BARS method first determines the main performance dimensions of the job, for example, interpersonal relationships. Then the tool utilizes narrative information, such as from a critical incidents file, and assigns quantified ranks to each expected behavior. In this system, there is a specific narrative outlining what exemplifies a “good” and “poor” behavior for each category. The advantage of this type of system is that it focuses on the desired behaviors that are important to complete a task or perform a specific job. This method combines a graphic rating scale with a critical incidents system. The US Army Research Institute (Phillips, et. al., 2006) developed a BARS scale to measure the abilities of tactical thinking skills for combat leaders. Figure 11.4 “Example of BARS” provides an example of how the Army measures these skills.

Figure 11.4 Example of BARS

Figure 11.5 More Examples of Performance Appraisal Types

How Would You Handle This?

Playing Favorites

You were just promoted to manager of a high-end retail store. As you are sorting through your responsibilities, you receive an e-mail from HR outlining the process for performance evaluations. You are also notified that you must give two performance evaluations within the next two weeks. This concerns you, because you don’t know any of the employees and their abilities yet. You aren’t sure if you should base their performance on what you see in a short time period or if you should ask other employees for their thoughts on their peers’ performance. As you go through the files on the computer, you find a critical incident file left from the previous manager, and you think this might help. As you look through it, it is obvious the past manager had “favorite” employees and you aren’t sure if you should base the evaluations on this information. How would you handle this?

Table 11.3 Advantages and Disadvantages of Each Performance Appraisal Method

Key Takeaways

- When developing performance appraisal criteria, it is important to remember the criteria should be job specific and industry specific.

- The performance appraisal criteria should be based on the job specifications of each specific job. General performance criteria are not an effective way to evaluate an employee.

- The rating is the scale that will be used to evaluate each criteria item. There are a number of different rating methods, including scales of 1–5, yes or no questions, and essay.

- In a graphic rating performance evaluation, employees are rated on certain desirable attributes. A variety of rating scales can be used with this method. The disadvantage is possible subjectivity.

- An essay performance evaluation will ask the manager to provide commentary on specific aspects of the employee’s job performance.

- A checklist utilizes a yes or no rating selection, and the criteria are focused on components of the employee’s job.

- Some managers keep a critical incidents file . These incidents serve as specific examples to be written about in a performance appraisal. The downside is the tendency to record only negative incidents and the time it can take to record this.

- The work standards performance appraisal approach looks at minimum standards of productivity and rates the employee performance based on minimum expectations. This method is often used for sales forces or manufacturing settings where productivity is an important aspect.

- In a ranking performance evaluation system, the manager ranks each employee from most valuable to least valuable. This can create morale issues within the workplace.

- An MBO or management by objectives system is where the manager and employee sit down together, determine objectives, then after a period of time, the manager assesses whether those objectives have been met. This can create great development opportunities for the employee and a good working relationship between the employee and manager.

- An MBO’s objectives should be SMART: specific, measurable, attainable, results oriented, and time limited.

- A BARS approach uses a rating scale but provides specific narratives on what constitutes good or poor performance.

Review each of the appraisal methods and discuss which one you might use for the following types of jobs, and discuss your choices.

- Administrative Assistant

- Chief Executive Officer

- Human Resource Manager

- Retail Store Assistant Manager

1 “The Struggle to Measure Performance,” BusinessWeek , January 9, 2006, accessed August 15, 2011, http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/06_02/b3966060.htm .

Doran, G. T., “There’s a S.M.A.R.T. Way to Write Management’s Goals and Objectives,” Management Review 70, no. 11 (1981): 35.

Drucker, P., The Practice of Management (New York: Harper, 2006).

Grote, R., Forced Ranking: Making Performance Management Work (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2005).

Lowery, M., “Forcing the Issue,” Human Resource Executive Online , n.d., accessed August 15, 2011, http://www.hrexecutive.com/HRE/story.jsp?storyId=4222111&query=ranks .

Phillips, J., Jennifer Shafter, Karol Ross, Donald Cox, and Scott Shadrick, Behaviorally Anchored Rating Scales for the Assessment of Tactical Thinking Mental Models (Research Report 1854), June 2006, US Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, accessed August 15, 2011, http://www.hqda.army.mil/ari/pdf/RR1854.pdf .

Sprenkel, L., “Forced Ranking: A Good Thing for Business?” Workforce Management, n.d., accessed August 15, 2011, http://homepages.uwp.edu/crooker/790-iep-pm/Articles/meth-fd-workforce.pdf .

Human Resource Management Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Understanding Performance Appraisal

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2023

- pp 12989–12993

- Cite this reference work entry

- Benati Igor 2

12 Accesses

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Aggarwal A, Thakur GSM (2013) Techniques of performance appraisal – a review. Int J Eng Adv Technol 2(3):617–621

Google Scholar

Boudreau JW, Ramstad PM (2007) Beyond HR: the new science of human capital. Harvard Business Press, Boston

Chiang FF, Birtch TA (2010) Appraising performance across borders: an empirical examination of the purposes and practices of performance appraisal in a multi-country context. J Manag Stud 47(7):1365–1393

Daley DM (1992) Performance appraisal in the public sector: techniques and applications. Quorum, Westport

Deb T (2006) Strategic approach to human resource management. Atlantic Publishers & Dist., New Delhi

DeNisi AS, Pritchard RD (2006) Performance appraisal, performance management and improving individual performance: a motivational framework. Manag Organ Rev 2(2):253–277

Article Google Scholar

DeNisi AS, Cafferty TP, Meglino BM (1984) A cognitive view of the performance appraisal process: a model and research propositions. Organ Behav Hum Perform 33(3):360–396

Guthrie JP (2001) High-involvement work practices, turnover, and productivity: evidence from New Zealand. Acad Manag J 44:180–190

Harris H, Brewster C, Sparrow P (2003) International human resource management. CIPD Publishing, London

Ikramullah M, Shah B, Khan S, ul Hassan, F. S., & Zaman, T. (2012) Purposes of performance appraisal system: a perceptual study of civil servants in district Dera Ismail Khan Pakistan. Int J Bus Manage 7(3):142

Johlke MC, Duhan DF (2001) Testing competing models of sales force communication. J Pers Sell Sales Manag 21(4):265–277

Kuvaas B (2008) An exploration of how the employee–organization relationship affects the linkage between perception of developmental human resource practices and employee outcomes. J Manag Stud 45:1–25

Mayer RC, Davis JH (1999) The effect of the performance appraisal system on trust for management: a field quasi-experiment. J Appl Psychol 84:123–136

Pettijohn CE, Pettijohn LS, d’Amico M (2001) Characteristics of performance appraisals and their impact on sales force satisfaction. Hum Resour Dev Q 12(2):127–146

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

CNR – National Research Council of Italy, Torino, Italy

Benati Igor

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Benati Igor .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL, USA

Ali Farazmand

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Igor, B. (2022). Understanding Performance Appraisal. In: Farazmand, A. (eds) Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66252-3_3513

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66252-3_3513

Published : 06 April 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-66251-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-66252-3

eBook Packages : Economics and Finance Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

What you need to know about performance appraisal methods

Wondering what performance appraisal methods are best for your business?

With the increasing shift to remote work and businesses re-inventing themselves to suit modern needs, it’s critical to redefine your performance management strategy.

These new strategies should encourage employees to make the most of the opportunity to work from home and develop processes that help your business grow.

In this article, we’ll discuss everything you need to know about performance appraisal methods. We’ll also discuss why employee performance appraisal is so important for companies.

This Article Contains:

(click on specific links to jump to a particular section of the page)

What is Performance Appraisal?

- Self-Evaluation Method

- Essay Appraisal Method

- The Critical Incident Method

- How to Build an Efficient System of Employee Performance Appraisal

What is the Purpose of Performance Appraisal?

Let’s dive in.

Performance appraisals are a regular process where employers evaluate an employee’s performance against a predetermined, measurable set of objectives.

Usually conducted quarterly or annually, the primary goal of performance evaluation is to determine how well an employee meets the company’s expectations.

Now there are primarily two ways to conduct the performance appraisal process — using the traditional method or the modern method.

The traditional method emphasizes evaluating an employee for their personality traits , such as:

- Dependability

- Integrity

- Leadership potential, etc.

On the other hand, the modern performance appraisal method emphasizes the evaluation of work results (or job achievements) over the employee’s traits.

Top 3 Performance Appraisal Methods for Remote Teams

Let’s look at the top three performance appraisal methods that companies can use for the performance appraisals of remote members:

1. Self-Evaluation Method

This appraisal process allows employees to scrutinize their own performance and give themselves feedback.

The self-appraisal method is especially useful for remote teams as you’ll be able to:

- Gain insights into the employee’s work, performance, and the way they operate.

- Know the employee’s key strengths and weaknesses.

- Determine if your employees take their responsibilities and duties seriously.

Once a remote employee has reviewed themselves, employers can use the ranking method to rate the individual based on their strengths and weaknesses.

How do you go about this method?

You give employees a comprehensive questionnaire along with some open-ended questions about their performance.

Here are a few sample questions:

- What goals would you like to accomplish in the next few months?

- What achievements are you most proud of since the last evaluation?

- What targets were you unable to achieve this past year?

- What would you have done differently to achieve the missed targets?

2. Essay Appraisal Method

The essay appraisal method involves the remote employee’s evaluation by their superiors and other team members.

In this method, you ask the appraiser to:

- Give a detailed description of the employee’s performance and talk about the strengths and weaknesses of the employee’s behavior.

- Provide suitable examples to support the information given in the performance review.

- Use a rating scale (1-10) to evaluate the employee’s attributes such as work ethics, leadership, communication, interpersonal skills, etc.

Why do you need this?

With the essay appraisal method, you get a comprehensive view of how remote employees participate as team members in their work group.

You can also determine if the employees’ behavior might cause issues at the workplace.

For instance, you can identify and prevent negative incidents like a remote employee spreading rumors among coworkers.

3. The Critical Incident Method

The critical incident method helps you determine how remote team members handled themselves during certain stressful situations. This way, you can learn more about their behavior at the workplace.

Here are the steps involved in this method of performance appraisal:

- Note down how an employee reacted to a specific situation (such as missed deadlines, etc.)

- Identify if the remote employee’s behavior was ‘good’ or ‘bad.’

- Assign a score to their performance during those incidents.

The critical incident method helps you and your HR department determine the skills, attitudes, values, and knowledge a remote employee needs to perform well during a crisis.

You can also identify which employees have the potential to be remote team managers based on their conduct.

Other Remote Employee Appraisal Methods

Some other performance appraisal methods that you can use to evaluate your remote team include:

- Human resource cost accounting method: Analyzes the employee’s performance through the monetary benefits they yield to the company.

- Management By Objectives (MBO): Appraises managers and employees’ progress on some pre-set goals.

- Psychological appraisal: Determines employees’ hidden potential with a psychological test and predicts their future performance.

- 360-degree feedback: Evaluates an employee using feedback collected from the employee’s circle of influence — peers, managers, and customers.

- Forced distribution method: Compare remote members against one another over any given performance standard.

- Forced choice method: The reviewer is given a few statements that apply to an employee, and they must decide if the information is true or false.

- Field review method: A HR or administrator observes an employee for a few days and evaluates performance.

- Journaling : An employee writes down all their achievements throughout a year and presents them to the evaluator.

How to Build an Efficient Remote Employee Performance Appraisal System

Since working from home is the new normal, it’s essential to consider how you want to conduct performance evaluations in the future.

With the right performance appraisal method, you can make the whole experience effective and rewarding.

Here’s how you can build an efficient employee performance appraisal system:

1. Reflect on the Purpose of Appraisal

You need to know what you want to achieve with your performance management system.

For most organizations, the company’s pre-pandemic goals are not applicable anymore.

The company goalposts have shifted , and the context has changed.

In a remote environment, you can’t measure employee performance just from the volume of work they do every day.

Instead, you should look at the employees’ resilience, empathy, and adaptability in these tough times. Ideally, you should acknowledge and reward your employees for maintaining proper communication and teamwork.

2. Communicate Proactively

There are several challenges unique to telecommuting , such as,

- Reduced access to managerial support and internal communication.

- No visual cues to understand team response.

- Asynchronous communication due to different time zones, etc.

So it’s critical to have a robust telecommunication policy to overcome these challenges and ensure effective communication.

You must also use video communication tools for a performance appraisal meeting in the remote work environment.

Visual clues like facial expressions allow employees to understand the subtext of the discussion.

Here are some tips you can use to make video appraisals more effective:

- Be as explicit and verbal as possible in the discussion.

- Listen well and encourage back and forth communication.

- Spend time to ensure that things don’t get lost in translation.

- If you need to deliver negative feedback to an employee, reassure them that you’re criticizing their performance and not their self-worth.

3. Practice Empathy

There’s no fixed template when it comes to evaluating job performance — everyone is trying to do their best in these unique circumstances.

Ensure that you make an empathetic assessment that’s flexible and recognize the hardships that your employees may be enduring.

An empathic leadership style can bring your employees closer, increase productivity, morale, and loyalty.

So how can you have a more empathetic appraisal ?

Acknowledge the fact that it’s difficult to cut out emotions and be 100% professional all the time.

Have a narrative assessment that provides an individual employee with specific information. Point out the areas they need to improve and what they’re doing well.

However, remember that even talented employees can go through a rough patch that might impact their actual performance.

In such cases, you must:

- Ensure a positive and supportive work environment for all team members.

- Avoid too much work pressure.

- Respect the contributions of every employee and help them improve their work.

4. Eliminate Any Biases

While managers may strive to be as objective as possible in performance assessments, sometimes implicit biases inevitably creep in.

You must become aware of biases, such as:

- Presenting employees with a good past performance record more favorably.

- Viewing average performers in a more critical light.

- Making assumptions about an employee’s attitude based on their performance.

When you recognize these biases, you can take steps to correct them.

It’ll ensure that you avoid a situation that discourages average employees from improving their performance. On the other extreme, you’ll also avoid encouraging efficient employees into overworking themselves.

Some steps that you can take to counteract your biases can include:

- Gathering feedback from different sources.

- Measuring performance against objective performance metrics .

- Using employee self-evaluations against your perception of their work to eliminate subjectivity, etc.

5. Use Productivity Tools

In a remote work environment, you need to provide specific feedback to your employees.

But that’s not all.

You need to conduct frequent, smaller evaluations such as monthly or quarterly check-ins.

So how can you do that?

By using performance management tools to keep a tab on the work performance of your remote team in real-time.

These tools can track and collect workday data and enable your employees and management with the information needed to make strategic improvements.

Time Doctor is one such tool that can help you manage your employee performance and take steps to improve overall productivity and profitability.

Used by large corporations as well as small and medium businesses, TimeDoctor is a performance management software that can give you insights into your team’s effectiveness.

You can use workday data from Time Doctor to:

- See the total amount of time employees spend on projects and tasks.

- View idle and inactive time with the idle time tracker.

- Get productivity reports broken down by day, week, or months.

- Keep a tab on your employee’s most-used websites and applications.

- See if your employees are actually working with screenshots and screencasts.

- Know how they spend time on daily tasks with the daily timeline overview and more .

Let’s look at why employee performance appraisal is important:

1. Maximizes Employee Potential

Constant feedback on an employee’s performance will help you track their productivity.

You can then take steps to:

- Ensure tasks are assigned based on the employee’s skill and competency.

- Give more training to less efficient employees.

- Encourage employees to maximize their potential.

- Motivate an employee to work towards their career growth.

- Address any behavioral issues that may be affecting team productivity.

2. Boosts Team Management

Effective performance appraisal gives an employee a structured review process.

This allows employees to approach the management for:

- Discussions related to performance, promotions, etc.

- Long term and short term goal setting and achieving targets.

- Clarifying expectations and growth plans for the future.

- Identifying and resolving bottlenecks in the project execution.

With an effective appraisal technique, you also eliminate micromanagement .

Why is this important?

When employees feel that every aspect of their work is under the scrutiny of an evaluator, it may negatively impact their morale.

Eliminating micromanagement will enhance the trust between managers and the employees and do away with the time-consuming task of always monitoring employees.

3. Improves Your Business’ Bottom Line

Performance appraisal system helps the management team :

- Decide the promotions, transfers, and rewards for every employee.

- Enhance decision making in situations that require layoffs or filling job roles internally.

- Optimize efficiency and employee engagement at the workplace.

- Ensure that your staff is not getting paid for hours where they were idle or inactive.

When you take such steps to maximize your team productivity, you’ll increase business output, and ultimately your profits.

Wrapping Up

Remote working may have compelled most companies to revisit how they evaluate employees.

However, it also presents an opportunity to shift towards a more people-focused appraisal system.

Employee performance appraisal isn’t just about dealing with poor performance. It involves setting the right employee expectations and training employees to be more productive.

An employee-centric performance appraisal system allows us to work towards that goal.

Go through the tips we have suggested in the article, and revisit your idea of what an employee performance appraisal should look like.

Book a free demo of Time Doctor

Andy is a technology & marketing leader who has delivered award-winning and world-first experiences.

How to manage toxic employees in a remote workplace

12 excellent employee time clocks for your workplace (digital and biometric), related posts, innovate, adapt, succeed: refining your hr team structure, your guide to the art of organizational change management , engineering team structure essentials: building, evaluating, and improving, the top 5 mistakes in team structure and how to prevent them, 7 steps to building a scalable team structure for growth, building blocks of success: creating a finance team structure that works.

- Performance Appraisal

- Knowledge Hub

- Employee Performance

- What is a performance appraisal?

The purpose of a performance appraisal

- How to organize a performance appraisal process

Performance appraisal examples

- Performance appraisal methods

5 Modern method of performance appraisal

What is a performance appraisal.

A performance appraisal is the periodic assessment of an employee’s job performance as measured by the competency expectations set out by the organization.

The performance assessment often includes both the core competencies required by the organization and also the competencies specific to the employee’s job.

The appraiser, often a supervisor or manager, will provide the employee with constructive, actionable feedback based on the assessment. This in turn provides the employee with the direction needed to improve and develop in their job.

Based on the type of feedback , a performance appraisal is also an opportunity for the organization to recognize employee achievements and future potential.

The purpose of a performance appraisal is two-fold: It helps the organization to determine the value and productivity that employees contribute, and it also helps employees to develop in their own roles.

Benefit for organization

Employee assessments can make a difference in the performance of an organization. They provide insight into how employees are contributing and enable organizations to:

- Identify where management can improve working conditions in order to increase productivity and work quality.

- Address behavioral issues before they impact departmental productivity.

- Encourage employees to contribute more by recognizing their talents and skills

- Support employees in skill and career development

- Improve strategic decision-making in situations that require layoffs, succession planning, or filling open roles internally

Benefit for employee

Performance appraisals are meant to provide a positive outcome for employees. The insights gained from assessing and discussing an employee’s performance can help:

- Recognize and acknowledge the achievements and contributions made by an employee.

- Recognize the opportunity for promotion or bonus.

- Identify and support the need for additional training or education to continue career development.

- Determine the specific areas where skills can be improved.

- Motivate an employee and help them feel involved and invested in their career development.

- Open discussion to an employee’s long-term goals.

How to organize a performance appraisal process

Conducting a performance review with an employee requires skill and training on the part of the appraiser. The negative perception that is often associated with the performance appraisal is due in part to a feeling of being criticized during the process.

A performance appraisal is meant to be the complete opposite. Often, the culprit is in the way the appraisal is conducted via the use of language.

The way the sender of a message uses language determines how the other person interprets the message once received. This can include tone of voice, choice of words, or even body language.

Because a performance appraisal is meant to provide constructive feedback, it is crucial that appropriate language and behavior are used in the process.

Human Resources (HR) are the support system for managers and supervisors to be trained in tactfully handling the appraisal process.

The performance appraisal process:

- The assessment process is usually facilitated by Human Resources, who assist managers and supervisors in conducting the individual appraisals within their departments.

- An assessment method should be established.

- Required competencies and job expectations need to be drafted for each employee.

- Individual appraisals on employee performance are conducted.

- A one on one interview is scheduled between the manager and employee to discuss the review.

- Future goals should be discussed between employee and manager.

- A signed-off version of the performance review is archived.

- Appraisal information is utilized by human resources for appropriate organizational purposes, such as reporting, promotions, bonuses or succession planning.

Let’s take a look at one example of a Manager speaking to an employee during a performance appraisal. Below are three versions of the same example.

Compare the difference in language and behavior and how it can change the end-result:

1. An appropriate appraisal example with mixed feedback

“We can start the review by looking at how each project went for you this quarter. Does that sound OK? First, every project you have worked on in the last four months has met the expected deadline and were all within their budgets. I see one project here was even early. They were all implemented successfully. Well done. You have succeeded in the criteria expected of a Project Manager here at ABC Company. Let’s take a look at a few areas where you might be able to develop your project management skills further. In Project A, B, and C, a few team members expressed that they were unsure what to begin working on in the first few meetings and felt that they were engaging in their tasks a bit late. When they tried to express this in later meetings, they felt there was hostility towards them. For upcoming Projects D, E, and F, is there anything that can be done to get team members up and running more quickly? Could more detailed task planning be completed prior to the project kick-off?”

Debrief : This example removes the errors from the first example and puts them in a more constructive light.

- The appraisal begins by involving the employee and making them feel like a valued part of the process.

- The appraiser focuses on measurable outcomes, such as each individual project, instead of broad, baseless generalizations.

- Positives are the focus of the assessment.

- Areas for improvement are offered in a constructive and neutral format by referring to specific events in the employee’s day-to-day tasks.

- The employee is given the opportunity to problem-solve the situation and contribute to their own sense of self-development.

- Constructive solutions are offered so the employee has a clear idea on what they can do better next time.

2. An inappropriate negative appraisal example

“Let’s talk about some of the problems. You are never proactive when it comes to the start of a new project. Things are left too late and there are often complaints. I have heard that your attitude has been less than positive during project meetings. You seem to have things going on at home right now, but they shouldn’t be intruding on your work.”

This example is extreme, but it conveys most of the errors that can occur in a performance review.

- The appraisal begins with a negative. It has been shown that starting with the positives can set the tone for the appraisal and helps employees feel more receptive to feedback.

- The appraiser speaks in a negative, accusatory language and bases the assessment on assumption instead of measured facts. An appraisal needs to be based on measured facts.

- The appraiser makes the discussion personal; a performance review should remain focused on the contributions of the employee to the job and never be about the individual as a person.

- Phrases like “ you are ” or “ you always ” are generalizations about the employee; a performance appraisal needs to be about specific contributions to specific job tasks.

3. An appropriate appraisal example for underperformers

“I wanted to talk to you today about your performance during the last quarter. Looking at the completed project schedules and project debriefs here, I see that each of the five projects was kicked off late. Team members reported having trouble getting the resources and information they needed to start and complete their tasks. Each project was delivered a week or more late and had considerable budget creep. Project A was over by $7000. Project B was over by $9,000, for example. These budget overages were not authorized. I think we really have potential to turn this around and I really want to see you succeed. The role of Project Manager requires you to kick-off projects on-time, make sure your team members have the resources they need, and it’s crucial that any budget issues or delays are discussed with myself or the other Manager. For the upcoming projects this month, I’d like you to draft a project plan one week prior to any project kick-off. We can go over it together and figure out where the gaps might be. Did you have any suggestions on how you might be able to improve the punctuality of your projects or effectiveness of how they are run?”

Debrief : This example deals with an employee who seems to be struggling. The appraiser unfortunately has a lot of negative feedback to work through, but has successfully done so using appropriate language, tone and examples:

- The feedback does not use accusatory language or tone, nor does it focus on the person. This is especially important at the start of a performance review when the topic is being introduced. Being accusatory can make an employee feel uncomfortable, upset or defensive and set the wrong tone for the rest of the review. Comments should remain focused on the employee’s work.

- The comments are constructive and specific. The appraiser uses specific examples with evidence to explain the poor performance and does not make general, unsubstantiated comments. Making general, broad comments like “Your projects have a lot of problems and are always late” are unfair as they cannot be proven. The tone also creates hostility and does not help the employee to solve the problem.

- The appraiser offers a positive comment about improving the situation and also a specific solution to improve the performance. The point of a performance review is to motivate and help an employee, not cut them down.

- The appraiser asks for the input of the employee on how to solve the problem. This empowers the employee to become more involved in their skill development and ends a negative review on a positive note.

4. The inflated appraisal example

“I don’t think we have too much to talk about today as everything seems just fine. Your projects are always done on time and within budget. I’m sure you made the right decisions with your team to achieve all of that. You and I definitely think alike when it comes to project management. Keep up the great work.”

Debrief : This example appears like a perfect performance appraisal, but it’s actually an example of how to inappropriate:

- The feedback glosses over any specifics regarding the employee’s actual work and instead offers vague, inflated comments about everything being great. Feedback needs to refer to specific events.

- Any mention of trouble on the team is ignored. A performance review needs to discuss performance issues before they become serious later on.

- The appraiser compares the employee to himself. This could be referred to as the “halo effect”, where the appraiser allows one aspect of the employee to cloud his or her judgement.

- Nobody is perfect; every appraisal should offer some form of improvement that the employee can work towards, whether it is honing a skill or learning a new skill.

Performance Appraisal Methods

There are many ways an organization can conduct a performance appraisal, owing to the countless different methods and strategies available.

In addition, each organization may have their own unique philosophy making an impact on the way the performance assessment is designed and conducted.

A performance review is often done annually or semi-annually at the minimum, but some organizations do them more often.

There are some common and modern appraisal methods that many organizations gravitate towards, including:

1. Self-evaluation

In a self-evaluation assessment, employees first conduct their performance assessment on their own against a set list of criteria.

The pro is that the method helps employees prepare for their own performance assessment and it creates more dialogue in the official performance interview.

The con is that the process is subjective, and employees may struggle with either rating themselves too high or too low.

2. Behavioral checklist

A Yes or No checklist is provided against a series of traits. If the supervisor believes the employee has exhibited a trait, a YES is ticked.

If they feel the employee has not exhibited the trait, a NO is ticked off. If they are unsure, it can be left blank.

The pro is the simplicity of the format and its focus on actual work-relate tasks and behaviors (ie. no generalizing).

The con is that there is no detailed analysis or detail on how the employee is actually doing, nor does it discuss goals.

3. 360-degree feedback

This type of review includes not just the direct feedback from the manager and employee, but also from other team members and sources.

The review also includes character and leadership capabilities.

The pro is that it provides a bigger picture of an employee’s performance.

The con is that it runs the risk of taking in broad generalizations from outside sources who many not know how to provide constructive feedback .

4. Ratings scale

A ratings scale is a common method of appraisal. It uses a set of pre-determined criteria that a manager uses to evaluate an employee against.

Each set of criteria is weighted so that a measured score can be calculated at the end of the review.

The pro is that the method can consider a wide variety of criteria, from specific job tasks to behavioral traits. The results can also be balanced thanks to the weighting system. This means that if an employee is not strong in a particularly minor area, it will not negatively impact the overall score.

The con of this method is the possible misunderstanding of what is a good result and what is a poor result; managers need to be clear in explaining the rating system.

5. Management by objectives

This type of assessment is a newer method that is gaining in popularity. It involves the employee and manager agreeing to a set of attainable performance goals that the employee will strive to achieve over a given period of time.

At the next review period, the goals and how they have been met are reviewed, whilst new goals are created.

The pro of this method is that it creates dialogue between the employee and employer and is empowering in terms of personal career development.

The con is that it risks overlooking organizational performance competencies that should be considered.

Ivan Andreev

Demand Generation & Capture Strategist

Ivan Andreev is a dedicated marketing professional with a proven track record of driving growth and efficiency in various marketing domains, especially SEO. With a career spanning over a decade, Ivan has developed a deep understanding of marketing strategies, project management, data analysis, and team leadership. His strong commitment to knowledge sharing, passion for process optimization, and turning challenges into opportunities have solidified his reputation as a pivotal player in the marketing team.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.6 Performance Appraisal Methods

In this section, we will discuss some of the main methods used to assess performance. However, before discussing these methods, we must discuss how they approach the assessment of individual performance. Some methods focus on the employee’s specific traits in relation to the job. For these methods, the objective is to capture whether or not the employees possess the KSAO’s required for the job. An example would be to assess whether a salesperson is outgoing or whether the accounts payable clerks are conscientious and pay attention to detail.

Another way to approach the assessment of performance is to look at individual actions within a specific job. This focus on behaviour, for example, would try to measure whether the salesperson uses a certain protocol when approaching customers or whether the accounts payable clerk follows up on her phone calls. The focus is on ‘what employees actually do’ as opposed to ‘who the employee is’ (for the trait methods). Comparative methods compare one employee with other employees. Finally, results methods are focused on objective employee accomplishments. Note that many organizations will use these methods in combination.

Graphic Rating Scale

The graphic rating scale , a trait method, is perhaps the most popular choice for performance evaluations. This type of evaluation lists the traits required for the job and asks the source to rate the individual on each attribute such as dependability and creativity. For example, the ratings can include a scale of 1–10; excellent, average, or poor; or exceeds, meets, or does not meet expectations.

The disadvantage of this type of scale is that it is quite subjective. Thus, many organizations use a graphic rating scale in conjunction with other appraisal methods to further solidify the tool’s validity. For example, some organizations use a mixed standard scale, which is similar to a graphic rating scale. This scale includes a series of mixed statements representing excellent, average, and poor performance, and the manager is asked to rate a “+” (performance is better than stated), “0” (performance is at stated level), or “−” (performance is below stated level). Mixed standard statements might include the following:

- The employee gets along with most coworkers and has had only a few interpersonal issues.

- This employee takes initiative.

- The employee consistently turns in below-average work.

- The employee always meets established deadlines.

Essay Appraisal

In an essay appraisal , the evaluator answers a series of questions about the employee’s performance in essay form. This can be a trait method and/or a behavioural method, depending on how the manager writes the essay. These statements may include strengths and weaknesses about the employee or statements about past performance. They can also include specific examples of past performance. The disadvantage of this type of method (when not combined with other rating systems) is that the manager’s writing ability can contribute to the effectiveness of the evaluation. Also, managers may write less or more, which means less consistency between performance appraisals by various managers.

Checklist Scale