- About Project

- Testimonials

Business Management Ideas

Essay on Obesity

List of essays on obesity, essay on obesity – short essay (essay 1 – 150 words), essay on obesity (essay 2 – 250 words), essay on obesity – written in english (essay 3 – 300 words), essay on obesity – for school students (class 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 standard) (essay 4 – 400 words), essay on obesity – for college students (essay 5 – 500 words), essay on obesity – with causes and treatment (essay 6 – 600 words), essay on obesity – for science students (essay 7 – 750 words), essay on obesity – long essay for medical students (essay 8 – 1000 words).

Obesity is a chronic health condition in which the body fat reaches abnormal level. Obesity occurs when we consume much more amount of food than our body really needs on a daily basis. In other words, when the intake of calories is greater than the calories we burn out, it gives rise to obesity.

Audience: The below given essays are exclusively written for school students (Class 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 Standard), college, science and medical students.

Introduction:

Obesity means being excessively fat. A person would be said to be obese if his or her body mass index is beyond 30. Such a person has a body fat rate that is disproportionate to his body mass.

Obesity and the Body Mass Index:

The body mass index is calculated considering the weight and height of a person. Thus, it is a scientific way of determining the appropriate weight of any person. When the body mass index of a person indicates that he or she is obese, it exposes the person to make health risk.

Stopping Obesity:

There are two major ways to get the body mass index of a person to a moderate rate. The first is to maintain a strict diet. The second is to engage in regular physical exercise. These two approaches are aimed at reducing the amount of fat in the body.

Conclusion:

Obesity can lead to sudden death, heart attack, diabetes and may unwanted illnesses. Stop it by making healthy choices.

Obesity has become a big concern for the youth of today’s generation. Obesity is defined as a medical condition in which an individual gains excessive body fat. When the Body Mass Index (BMI) of a person is over 30, he/ she is termed as obese.

Obesity can be a genetic problem or a disorder that is caused due to unhealthy lifestyle habits of a person. Physical inactivity and the environment in which an individual lives, are also the factors that leads to obesity. It is also seen that when some individuals are in stress or depression, they start cultivating unhealthy eating habits which eventually leads to obesity. Medications like steroids is yet another reason for obesity.

Obesity has several serious health issues associated with it. Some of the impacts of obesity are diabetes, increase of cholesterol level, high blood pressure, etc. Social impacts of obesity includes loss of confidence in an individual, lowering of self-esteem, etc.

The risks of obesity needs to be prevented. This can be done by adopting healthy eating habits, doing some physical exercise regularly, avoiding stress, etc. Individuals should work on weight reduction in order to avoid obesity.

Obesity is indeed a health concern and needs to be prioritized. The management of obesity revolves around healthy eating habits and physical activity. Obesity, if not controlled in its initial stage can cause many severe health issues. So it is wiser to exercise daily and maintain a healthy lifestyle rather than being the victim of obesity.

Obesity can be defined as the clinical condition where accumulation of excessive fat takes place in the adipose tissue leading to worsening of health condition. Usually, the fat is deposited around the trunk and also the waist of the body or even around the periphery.

Obesity is actually a disease that has been spreading far and wide. It is preventable and certain measures are to be taken to curb it to a greater extend. Both in the developing and developed countries, obesity has been growing far and wide affecting the young and the old equally.

The alarming increase in obesity has resulted in stimulated death rate and health issues among the people. There are several methods adopted to lose weight and they include different diet types, physical activity and certain changes in the current lifestyle. Many of the companies are into minting money with the concept of inviting people to fight obesity.

In patients associated with increased risk factor related to obesity, there are certain drug therapies and other procedures adopted to lose weight. There are certain cost effective ways introduced by several companies to enable clinic-based weight loss programs.

Obesity can lead to premature death and even cause Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Cardiovascular diseases have also become the part and parcel of obese people. It includes stroke, hypertension, gall bladder disease, coronary heart disease and even cancers like breast cancer, prostate cancer, endometrial cancer and colon cancer. Other less severe arising due to obesity includes osteoarthritis, gastro-esophageal reflux disease and even infertility.

Hence, serious measures are to be taken to fight against this dreadful phenomenon that is spreading its wings far and wide. Giving proper education on benefits of staying fit and mindful eating is as important as curbing this issue. Utmost importance must be given to healthy eating habits right from the small age so that they follow the same until the end of their life.

Obesity is majorly a lifestyle disease attributed to the extra accumulation of fat in the body leading to negative health effects on a person. Ironically, although prevalent at a large scale in many countries, including India, it is one of the most neglect health problems. It is more often ignored even if told by the doctor that the person is obese. Only when people start acquiring other health issues such as heart disease, blood pressure or diabetes, they start taking the problem of obesity seriously.

Obesity Statistics in India:

As per a report, India happens to figure as the third country in the world with the most obese people. This should be a troubling fact for India. However, we are yet to see concrete measures being adopted by the people to remain fit.

Causes of Obesity:

Sedentary lifestyle, alcohol, junk food, medications and some diseases such as hypothyroidism are considered as the factors which lead to obesity. Even children seem to be glued to televisions, laptops and video games which have taken away the urge for physical activities from them. Adding to this, the consumption of junk food has further aggravated the growing problem of obesity in children.

In the case of adults, most of the professions of today make use of computers which again makes people sit for long hours in one place. Also, the hectic lifestyle of today makes it difficult for people to spare time for physical activities and people usually remain stressed most of the times. All this has contributed significantly to the rise of obesity in India.

Obesity and BMI:

Body Mass Index (BMI) is the measure which allows a person to calculate how to fit he or she is. In other words, the BMI tells you if you are obese or not. BMI is calculated by dividing the weight of a person in kg with the square of his / her height in metres. The number thus obtained is called the BMI. A BMI of less than 25 is considered optimal. However, if a person has a BMI over 30 he/she is termed as obese.

What is a matter of concern is that with growing urbanisation there has been a rapid increase of obese people in India? It is of utmost importance to consider this health issue a serious threat to the future of our country as a healthy body is important for a healthy soul. We should all be mindful of what we eat and what effect it has on our body. It is our utmost duty to educate not just ourselves but others as well about this serious health hazard.

Obesity can be defined as a condition (medical) that is the accumulation of body fat to an extent that the excess fat begins to have a lot of negative effects on the health of the individual. Obesity is determined by examining the body mass index (BMI) of the person. The BMI is gotten by dividing the weight of the person in kilogram by the height of the person squared.

When the BMI of a person is more than 30, the person is classified as being obese, when the BMI falls between 25 and 30, the person is said to be overweight. In a few countries in East Asia, lower values for the BMI are used. Obesity has been proven to influence the likelihood and risk of many conditions and disease, most especially diabetes of type 2, cardiovascular diseases, sleeplessness that is obstructive, depression, osteoarthritis and some cancer types.

In most cases, obesity is caused through a combination of genetic susceptibility, a lack of or inadequate physical activity, excessive intake of food. Some cases of obesity are primarily caused by mental disorder, medications, endocrine disorders or genes. There is no medical data to support the fact that people suffering from obesity eat very little but gain a lot of weight because of slower metabolism. It has been discovered that an obese person usually expends much more energy than other people as a result of the required energy that is needed to maintain a body mass that is increased.

It is very possible to prevent obesity with a combination of personal choices and social changes. The major treatments are exercising and a change in diet. We can improve the quality of our diet by reducing our consumption of foods that are energy-dense like those that are high in sugars or fat and by trying to increase our dietary fibre intake.

We can also accompany the appropriate diet with the use of medications to help in reducing appetite and decreasing the absorption of fat. If medication, exercise and diet are not yielding any positive results, surgery or gastric balloon can also be carried out to decrease the volume of the stomach and also reduce the intestines’ length which leads to the feel of the person get full early or a reduction in the ability to get and absorb different nutrients from a food.

Obesity is the leading cause of ill-health and death all over the world that is preventable. The rate of obesity in children and adults has drastically increased. In 2015, a whopping 12 percent of adults which is about 600 million and about 100 million children all around the world were found to be obese.

It has also been discovered that women are more obese than men. A lot of government and private institutions and bodies have stated that obesity is top of the list of the most difficult and serious problems of public health that we have in the world today. In the world we live today, there is a lot of stigmatisation of obese people.

We all know how troubling the problem of obesity truly is. It is mainly a form of a medical condition wherein the body tends to accumulate excessive fat which in turn has negative repercussions on the health of an individual.

Given the current lifestyle and dietary style, it has become more common than ever. More and more people are being diagnosed with obesity. Such is its prevalence that it has been termed as an epidemic in the USA. Those who suffer from obesity are at a much higher risk of diabetes, heart diseases and even cancer.

In order to gain a deeper understanding of obesity, it is important to learn what the key causes of obesity are. In a layman term, if your calorie consumption exceeds what you burn because of daily activities and exercises, it is likely to lead to obesity. It is caused over a prolonged period of time when your calorie intake keeps exceeding the calories burned.

Here are some of the key causes which are known to be the driving factors for obesity.

If your diet tends to be rich in fat and contains massive calorie intake, you are all set to suffer from obesity.

Sedentary Lifestyle:

With most people sticking to their desk jobs and living a sedentary lifestyle, the body tends to get obese easily.

Of course, the genetic framework has a lot to do with obesity. If your parents are obese, the chance of you being obese is quite high.

The weight which women gain during their pregnancy can be very hard to shed and this is often one of the top causes of obesity.

Sleep Cycle:

If you are not getting an adequate amount of sleep, it can have an impact on the hormones which might trigger hunger signals. Overall, these linked events tend to make you obese.

Hormonal Disorder:

There are several hormonal changes which are known to be direct causes of obesity. The imbalance of the thyroid stimulating hormone, for instance, is one of the key factors when it comes to obesity.

Now that we know the key causes, let us look at the possible ways by which you can handle it.

Treatment for Obesity:

As strange as it may sound, the treatment for obesity is really simple. All you need to do is follow the right diet and back it with an adequate amount of exercise. If you can succeed in doing so, it will give you the perfect head-start into your journey of getting in shape and bidding goodbye to obesity.

There are a lot of different kinds and styles of diet plans for obesity which are available. You can choose the one which you deem fit. We recommend not opting for crash dieting as it is known to have several repercussions and can make your body terribly weak.

The key here is to stick to a balanced diet which can help you retain the essential nutrients, minerals, and, vitamins and shed the unwanted fat and carbs.

Just like the diet, there are several workout plans for obesity which are available. It is upon you to find out which of the workout plan seems to be apt for you. Choose cardio exercises and dance routines like Zumba to shed the unwanted body weight. Yoga is yet another method to get rid of obesity.

So, follow a blend of these and you will be able to deal with the trouble of obesity in no time. We believe that following these tips will help you get rid of obesity and stay in shape.

Obesity and overweight is a top health concern in the world due to the impact it has on the lives of individuals. Obesity is defined as a condition in which an individual has excessive body fat and is measured using the body mass index (BMI) such that, when an individual’s BMI is above 30, he or she is termed obese. The BMI is calculated using body weight and height and it is different for all individuals.

Obesity has been determined as a risk factor for many diseases. It results from dietary habits, genetics, and lifestyle habits including physical inactivity. Obesity can be prevented so that individuals do not end up having serious complications and health problems. Chronic illnesses like diabetes, heart diseases and relate to obesity in terms of causes and complications.

Factors Influencing Obesity:

Obesity is not only as a result of lifestyle habits as most people put it. There are other important factors that influence obesity. Genetics is one of those factors. A person could be born with genes that predispose them to obesity and they will also have difficulty in losing weight because it is an inborn factor.

The environment also influences obesity because the diet is similar in certain environs. In certain environments, like school, the food available is fast foods and the chances of getting healthy foods is very low, leading to obesity. Also, physical inactivity is an environmental factor for obesity because some places have no fields or tracks where people can jog or maybe the place is very unsafe and people rarely go out to exercise.

Mental health affects the eating habits of individuals. There is a habit of stress eating when a person is depressed and it could result in overweight or obesity if the person remains unhealthy for long period of time.

The overall health of individuals also matter. If a person is unwell and is prescribed with steroids, they may end up being obese. Steroidal medications enable weight gain as a side effect.

Complications of Obesity:

Obesity is a health concern because its complications are severe. Significant social and health problems are experienced by obese people. Socially, they will be bullied and their self-esteem will be low as they will perceive themselves as unworthy.

Chronic illnesses like diabetes results from obesity. Diabetes type 2 has been directly linked to obesity. This condition involves the increased blood sugars in the body and body cells are not responding to insulin as they should. The insulin in the body could also be inadequate due to decreased production. High blood sugar concentrations result in symptoms like frequent hunger, thirst and urination. The symptoms of complicated stages of diabetes type 2 include loss of vision, renal failure and heart failure and eventually death. The importance of having a normal BMI is the ability of the body to control blood sugars.

Another complication is the heightened blood pressures. Obesity has been defined as excessive body fat. The body fat accumulates in blood vessels making them narrow. Narrow blood vessels cause the blood pressures to rise. Increased blood pressure causes the heart to start failing in its physiological functions. Heart failure is the end result in this condition of increased blood pressures.

There is a significant increase in cholesterol in blood of people who are obese. High blood cholesterol levels causes the deposition of fats in various parts of the body and organs. Deposition of fats in the heart and blood vessels result in heart diseases. There are other conditions that result from hypercholesterolemia.

Other chronic illnesses like cancer can also arise from obesity because inflammation of body cells and tissues occurs in order to store fats in obese people. This could result in abnormal growths and alteration of cell morphology. The abnormal growths could be cancerous.

Management of Obesity:

For the people at risk of developing obesity, prevention methods can be implemented. Prevention included a healthy diet and physical activity. The diet and physical activity patterns should be regular and realizable to avoid strains that could result in complications.

Some risk factors for obesity are non-modifiable for example genetics. When a person in genetically predisposed, the lifestyle modifications may be have help.

For the individuals who are already obese, they can work on weight reduction through healthy diets and physical exercises.

In conclusion, obesity is indeed a major health concern because the health complications are very serious. Factors influencing obesity are both modifiable and non-modifiable. The management of obesity revolves around diet and physical activity and so it is important to remain fit.

In olden days, obesity used to affect only adults. However, in the present time, obesity has become a worldwide problem that hits the kids as well. Let’s find out the most prevalent causes of obesity.

Factors Causing Obesity:

Obesity can be due to genetic factors. If a person’s family has a history of obesity, chances are high that he/ she would also be affected by obesity, sooner or later in life.

The second reason is having a poor lifestyle. Now, there are a variety of factors that fall under the category of poor lifestyle. An excessive diet, i.e., eating more than you need is a definite way to attain the stage of obesity. Needless to say, the extra calories are changed into fat and cause obesity.

Junk foods, fried foods, refined foods with high fats and sugar are also responsible for causing obesity in both adults and kids. Lack of physical activity prevents the burning of extra calories, again, leading us all to the path of obesity.

But sometimes, there may also be some indirect causes of obesity. The secondary reasons could be related to our mental and psychological health. Depression, anxiety, stress, and emotional troubles are well-known factors of obesity.

Physical ailments such as hypothyroidism, ovarian cysts, and diabetes often complicate the physical condition and play a massive role in abnormal weight gain.

Moreover, certain medications, such as steroids, antidepressants, and contraceptive pills, have been seen interfering with the metabolic activities of the body. As a result, the long-term use of such drugs can cause obesity. Adding to that, regular consumption of alcohol and smoking are also connected to the condition of obesity.

Harmful Effects of Obesity:

On the surface, obesity may look like a single problem. But, in reality, it is the mother of several major health issues. Obesity simply means excessive fat depositing into our body including the arteries. The drastic consequence of such high cholesterol levels shows up in the form of heart attacks and other life-threatening cardiac troubles.

The fat deposition also hampers the elasticity of the arteries. That means obesity can cause havoc in our body by altering the blood pressure to an abnormal range. And this is just the tip of the iceberg. Obesity is known to create an endless list of problems.

In extreme cases, this disorder gives birth to acute diseases like diabetes and cancer. The weight gain due to obesity puts a lot of pressure on the bones of the body, especially of the legs. This, in turn, makes our bones weak and disturbs their smooth movement. A person suffering from obesity also has higher chances of developing infertility issues and sleep troubles.

Many obese people are seen to be struggling with breathing problems too. In the chronic form, the condition can grow into asthma. The psychological effects of obesity are another serious topic. You can say that obesity and depression form a loop. The more a person is obese, the worse is his/ her depression stage.

How to Control and Treat Obesity:

The simplest and most effective way, to begin with, is changing our diet. There are two factors to consider in the diet plan. First is what and what not to eat. Second is how much to eat.

If you really want to get rid of obesity, include more and more green vegetables in your diet. Spinach, beans, kale, broccoli, cauliflower, asparagus, etc., have enough vitamins and minerals and quite low calories. Other healthier options are mushrooms, pumpkin, beetroots, and sweet potatoes, etc.

Opt for fresh fruits, especially citrus fruits, and berries. Oranges, grapes, pomegranate, pineapple, cherries, strawberries, lime, and cranberries are good for the body. They have low sugar content and are also helpful in strengthening our immune system. Eating the whole fruits is a more preferable way in comparison to gulping the fruit juices. Fruits, when eaten whole, have more fibers and less sugar.

Consuming a big bowl of salad is also great for dealing with the obesity problem. A salad that includes fibrous foods such as carrots, radish, lettuce, tomatoes, works better at satiating the hunger pangs without the risk of weight gain.

A high protein diet of eggs, fish, lean meats, etc., is an excellent choice to get rid of obesity. Take enough of omega fatty acids. Remember to drink plenty of water. Keeping yourself hydrated is a smart way to avoid overeating. Water also helps in removing the toxins and excess fat from the body.

As much as possible, avoid fats, sugars, refined flours, and oily foods to keep the weight in control. Control your portion size. Replace the three heavy meals with small and frequent meals during the day. Snacking on sugarless smoothies, dry fruits, etc., is much recommended.

Regular exercise plays an indispensable role in tackling the obesity problem. Whenever possible, walk to the market, take stairs instead of a lift. Physical activity can be in any other form. It could be a favorite hobby like swimming, cycling, lawn tennis, or light jogging.

Meditation and yoga are quite powerful practices to drive away the stress, depression and thus, obesity. But in more serious cases, meeting a physician is the most appropriate strategy. Sometimes, the right medicines and surgical procedures are necessary to control the health condition.

Obesity is spreading like an epidemic, haunting both the adults and the kids. Although genetic factors and other physical ailments play a role, the problem is mostly caused by a reckless lifestyle.

By changing our way of living, we can surely take control of our health. In other words, it would be possible to eliminate the condition of obesity from our lives completely by leading a healthy lifestyle.

Health , Obesity

Get FREE Work-at-Home Job Leads Delivered Weekly!

Join more than 50,000 subscribers receiving regular updates! Plus, get a FREE copy of How to Make Money Blogging!

Message from Sophia!

Like this post? Don’t forget to share it!

Here are a few recommended articles for you to read next:

- Essay on Cleanliness

- Essay on Cancer

- Essay on AIDS

- Essay on Health and Fitness

No comments yet.

Leave a reply click here to cancel reply..

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Billionaires

- Donald Trump

- Warren Buffett

- Email Address

- Free Stock Photos

- Keyword Research Tools

- URL Shortener Tools

- WordPress Theme

Book Summaries

- How To Win Friends

- Rich Dad Poor Dad

- The Code of the Extraordinary Mind

- The Luck Factor

- The Millionaire Fastlane

- The ONE Thing

- Think and Grow Rich

- 100 Million Dollar Business

- Business Ideas

Digital Marketing

- Mobile Addiction

- Social Media Addiction

- Computer Addiction

- Drug Addiction

- Internet Addiction

- TV Addiction

- Healthy Habits

- Morning Rituals

- Wake up Early

- Cholesterol

- Reducing Cholesterol

- Fat Loss Diet Plan

- Reducing Hair Fall

- Sleep Apnea

- Weight Loss

Internet Marketing

- Email Marketing

Law of Attraction

- Subconscious Mind

- Vision Board

- Visualization

Law of Vibration

- Professional Life

Motivational Speakers

- Bob Proctor

- Robert Kiyosaki

- Vivek Bindra

- Inner Peace

Productivity

- Not To-do List

- Project Management Software

- Negative Energies

Relationship

- Getting Back Your Ex

Self-help 21 and 14 Days Course

Self-improvement.

- Body Language

- Complainers

- Emotional Intelligence

- Personality

Social Media

- Project Management

- Anik Singal

- Baba Ramdev

- Dwayne Johnson

- Jackie Chan

- Leonardo DiCaprio

- Narendra Modi

- Nikola Tesla

- Sachin Tendulkar

- Sandeep Maheshwari

- Shaqir Hussyin

Website Development

Wisdom post, worlds most.

- Expensive Cars

Our Portals: Gulf Canada USA Italy Gulf UK

Privacy Overview

- Second Opinion

Obesity in Teens

What is obesity in teens?

Obesity is when a teen has too much body fat. Obesity is a serious, long-term disease.

What causes obesity in a teen?

In many ways, childhood obesity is a puzzling disease. Doctors do not fully understand how the body controls weight and body fat. On one hand, the cause seems simple. If a person takes in more calories than he or she uses for energy, then he or she will gain weight.

But a teen's obesity can be caused by a combination of things. It can be linked to:

- Socioeconomic issues

- How the body turns food into energy (metabolism)

- Not getting enough sleep

- Lifestyle choices

Some endocrine disorders, diseases, and medicines may also have a strong effect on a child’s weight.

Which teens are at risk for obesity?

Things that may put your teen at risk for obesity are:

- Genes. Obesity may be passed down through families. Having even one obese parent may raise a child’s risk for it. Experts are looking at the link between genes, the ever-changing environment, and obesity.

- Metabolism. Each person’s body uses energy differently. Metabolism and hormones don’t affect everyone the same way. They may play a role in weight gain in children and teens.

- Socioeconomic factors. There is a strong tie between economic status and obesity. Obesity is more common among low-income people. In some places, people may have limited access to affordable healthy foods. Or they may not have a safe place to exercise.

- Lifestyle choices. Overeating and an inactive lifestyle both contribute to obesity. A diet full of sugary, high-fat, and refined foods can lead to weight gain. So can a lack of regular exercise. In children, watching TV and sitting at a computer can play a part.

What are the symptoms of obesity in a teen?

Too much body fat is the main symptom of obesity. But it’s hard to directly measure body fat. A guideline called the body mass index (BMI) is used to estimate it. The BMI uses a teen’s weight and height to come up with a result. The result is then compared with standards for children of the same gender between the ages of 2 and 20.

A teen who is overweight has a BMI between the 85th and 95th percentile for age and gender. He or she is obese if the BMI is greater than the 95th percentile for age and gender.

How is obesity diagnosed in a teen?

Obesity is diagnosed by a healthcare provider. BMI is often used to define obesity in teens. It has 2 categories:

- BMIs at the 95th percentile or more for age and gender, or BMIs of more than 30, whichever is smaller. BMI findings in this category mean the child should have a full health checkup.

- Family history of cardiovascular disease, high cholesterol, diabetes, and obesity

- High blood pressure

- Total cholesterol level

- Large gains in BMI from year to year

- Concerns about weight, including the child’s own concerns about being overweight

How is obesity treated in a teen?

Treatment depends on your teen’s symptoms, age, and health. It also depends on how severe the condition is.

Treatment for obesity may include:

- Diet counseling

- Changes to diet and amount of calories eaten

- More physical activity or an exercise program

- Behavior changes

- Individual or group therapy that focuses on changing behaviors and facing feelings linked to weight and normal developmental issues

- Support and encouragement for making changes and following recommended treatments

Treatment often involves the help of a nutritionist, mental health professionals, and an exercise specialist. Your teen’s treatment goals should be realistic. They should focus on a modest cutting back of calories, changing eating habits, and adding more physical activity.

What are possible complications of obesity in a teen?

Obesity can affect your teen’s health in a number of ways. These include:

- High blood pressure and high cholesterol. These are risk factors for heart disease.

- Diabetes. Obesity is the major cause of type 2 diabetes. It can cause resistance to insulin, the hormone that controls blood sugar. When obesity causes insulin resistance, blood sugar becomes higher than normal.

- Joint problems, such as osteoarthritis. Obesity can affect the knees and hips because of the stress placed on the joints by extra weight.

- Sleep apnea and breathing problems. Sleep apnea causes people to stop breathing for brief periods. It interrupts sleep throughout the night and causes sleepiness during the day. It also causes heavy snoring. The risk for other breathing problems such as asthma is higher in an obese child.

- Psychosocial effects. Modern culture often sees overly thin people as the ideal in body size. Because of this, people who are overweight or obese often suffer disadvantages. They may be blamed for their condition. They may be seen as lazy or weak-willed. Obese children can have low self-esteem that affects their social life and emotional health.

What can I do to help prevent obesity in a teen?

Young people often become overweight or obese because they have poor eating habits and aren’t active enough. Genes also play a role.

Here are some tips to help your teen stay at a healthy weight:

- Focus on the whole family. Slowly work to change your family’s eating habits and activity levels. Don’t focus on a child’s weight.

- Be a role model. Parents who eat healthy foods and are physically active set an example. Their child is more likely to do the same.

- Encourage physical activity. Children should get at least 60 minutes of physical activity each day.

- Limit screen time. Cut your teen’s screen time to less than 2 hours a day in front of the TV and computer.

- Have healthy snacks on hand. Keep the refrigerator stocked with fat-free or low-fat milk instead of soft drinks. Offer fresh fruit and vegetables instead of snacks high in sugar and fat.

- Aim for 5 or more. Serve at least 5 servings of fruits and vegetables each day.

- Drink more water. Encourage teens to have water instead of drinks with added sugar. Limit your child’s intake of soft drinks, sports drinks, and fruit juice drinks.

- Get enough sleep. Encourage teens to get more sleep every night. Earlier bedtimes have been found to decrease rates of obesity.

Key points about obesity in teens

- Obesity is a long-term disease. It’s when a teen has too much body fat.

- Many things can lead to childhood obesity. These include genes and lifestyle choices.

- Body mass index (BMI) is used to diagnose obesity. It’s based on a child’s weight and height.

- Treatment may include diet counseling, exercise, therapy, and support.

- Obesity can lead to many other health problems. Some of these are heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and joint problems.

- Obesity can be prevented with healthy lifestyle choices like being more physically active and eating more fruits and vegetables.

Tips to help you get the most from a visit to your child’s healthcare provider:

- Know the reason for the visit and what you want to happen.

- Before your visit, write down questions you want answered.

- At the visit, write down the name of a new diagnosis, and any new medicines, treatments, or tests. Also write down any new instructions your provider gives you for your child.

- Know why a new medicine or treatment is prescribed and how it will help your child. Also know what the side effects are.

- Ask if your child’s condition can be treated in other ways.

- Know why a test or procedure is recommended and what the results could mean.

- Know what to expect if your child does not take the medicine or have the test or procedure.

- If your child has a follow-up appointment, write down the date, time, and purpose for that visit.

- Know how you can contact your child’s provider after office hours. This is important if your child becomes ill and you have questions or need advice.

Related Links

- The Center for Healthy Weight

- Adolescent Bariatric Surgery

- Adolescent Medicine

- Pediatric Cardiology

- Our Services

- Chiari Malformation Center at Stanford Medicine Children's Health

Related Topics

A Chubby Baby Is Not a Sign of Future Obesity

Connect with us:

Download our App:

- Leadership Team

- Vision, Mission & Values

- The Stanford Advantage

- Government and Community Relations

- Get Involved

- Volunteer Services

- Auxiliaries & Affiliates

© 123 Stanford Medicine Children’s Health

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 18 May 2023

Child and adolescent obesity

- Natalie B. Lister ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9148-8632 1 , 2 ,

- Louise A. Baur ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4521-9482 1 , 3 , 4 ,

- Janine F. Felix 5 , 6 ,

- Andrew J. Hill ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3192-0427 7 ,

- Claude Marcus ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0890-2650 8 ,

- Thomas Reinehr ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4351-1834 9 ,

- Carolyn Summerbell 10 &

- Martin Wabitsch ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6795-8430 11

Nature Reviews Disease Primers volume 9 , Article number: 24 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

33k Accesses

31 Citations

250 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Paediatric research

The prevalence of child and adolescent obesity has plateaued at high levels in most high-income countries and is increasing in many low-income and middle-income countries. Obesity arises when a mix of genetic and epigenetic factors, behavioural risk patterns and broader environmental and sociocultural influences affect the two body weight regulation systems: energy homeostasis, including leptin and gastrointestinal tract signals, operating predominantly at an unconscious level, and cognitive–emotional control that is regulated by higher brain centres, operating at a conscious level. Health-related quality of life is reduced in those with obesity. Comorbidities of obesity, including type 2 diabetes mellitus, fatty liver disease and depression, are more likely in adolescents and in those with severe obesity. Treatment incorporates a respectful, stigma-free and family-based approach involving multiple components, and addresses dietary, physical activity, sedentary and sleep behaviours. In adolescents in particular, adjunctive therapies can be valuable, such as more intensive dietary therapies, pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery. Prevention of obesity requires a whole-system approach and joined-up policy initiatives across government departments. Development and implementation of interventions to prevent paediatric obesity in children should focus on interventions that are feasible, effective and likely to reduce gaps in health inequalities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Unraveling Complexity about Childhood Obesity and Nutritional Interventions: Modeling Interactions Among Psychological Factors

Keith Feldman, Gisela M. B. Solymos, … Nitesh V. Chawla

Pediatric weight management interventions improve prevalence of overeating behaviors

Stephanie G. Harshman, Ines Castro, … Lauren Fiechtner

Parent and child characteristics associated with treatment non-response to a short- versus long-term lifestyle intervention in pediatric obesity

Sarah Woo, Hong Ji Song, … Kyung Hee Park

Introduction

The prevalence of child and adolescent obesity remains high and continues to rise in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) at a time when these regions are also contending with under-nutrition in its various forms 1 , 2 . In addition, during the COVID-19 pandemic, children and adolescents with obesity have been more likely to have severe COVID-19 requiring hospitalization and mechanical ventilation 3 . At the same time, the pandemic was associated with rising levels of childhood obesity in many countries. These developments are concerning, considering that recognition is also growing that paediatric obesity is associated with a range of immediate and long-term negative health outcomes, a decreased quality of life 4 , 5 , an increased presentation to health services 6 and increased economic costs to individuals and society 7 .

Body weight is regulated by a range of energy homeostatic and cognitive–emotional processes and a multifactorial interplay of complex regulatory circuits 8 . Paediatric obesity arises when multiple environmental factors — covering preconception and prenatal exposures, as well as broader changes in the food and physical activity environments — disturb these regulatory processes; these influences are now widespread in most countries 9 .

The treatment of obesity includes management of obesity-associated complications, a developmentally sensitive approach, family engagement, and support for long-term behaviour changes in diet, physical activity, sedentary behaviours and sleep 10 . New evidence highlights the role, in adolescents with more severe obesity, of bariatric surgery 11 and pharmacotherapy, particularly the potential for glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) receptor agonists 12 .

Obesity prevention requires a whole-system approach, with policies across all government and community sectors systematically taking health into account, avoiding harmful health impacts and decreasing inequity. Programmatic prevention interventions operating ‘downstream’ at the level of the child and family, as well as ‘upstream’ interventions at the level of the community and broader society, are required if a step change in tackling childhood obesity is to be realized 13 , 14 .

In this Primer, we provide an overview of the epidemiology, causes, pathophysiology and consequences of child and adolescent obesity. We discuss diagnostic considerations, as well as approaches to its prevention and management. Furthermore, we summarize effects of paediatric obesity on quality of life, and open research questions.

Epidemiology

Definition and prevalence.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines obesity as “abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to health” 15 . Paediatric obesity is defined epidemiologically using BMI, which is adjusted for age and sex because of the physiological changes in BMI during growth 16 . Global prevalence of paediatric obesity has risen markedly over the past four decades, initially in high-income countries (HICs), but now also in many LMICs 1 .

Despite attempts to standardize the epidemiological classification, several definitions of paediatric obesity are in use; hence, care is needed when comparing prevalence rates. The 2006 WHO Child Growth Standard, for children aged 0 to 5 years, is based on longitudinal observations of multiethnic populations of children with optimal infant feeding and child-rearing conditions 17 . The 2007 WHO Growth Reference is used for the age group 5–19 years 18 , and the 2000 US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Growth Charts for the age group 2–20 years 19 . The WHO and CDC definitions based on BMI-for-age charts are widely used, including in clinical practice. By contrast, the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) definition, developed from nationally representative BMI data for the age group 2–18 years from six countries, is used exclusively for epidemiological studies 20 .

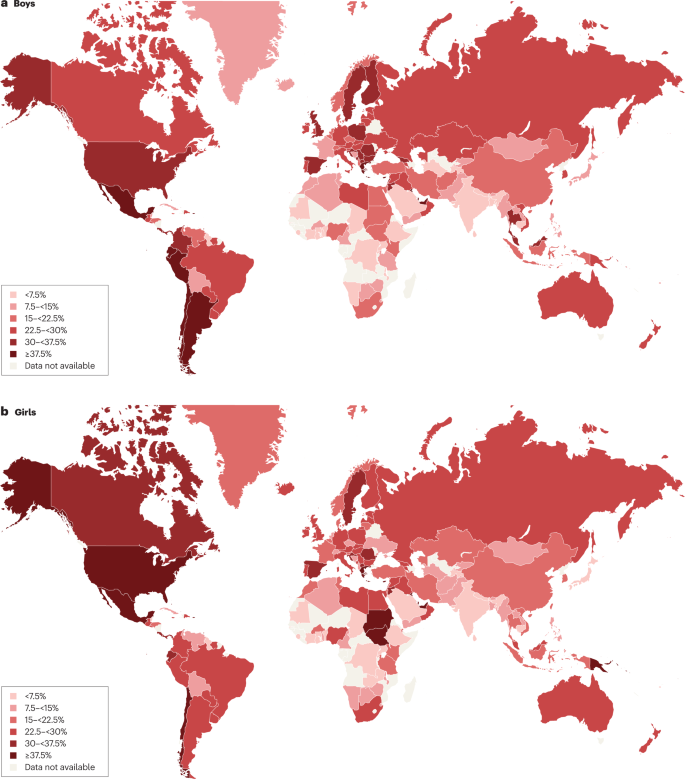

For the age group 5–19 years, between 1975 and 2016, the global prevalence of obesity (BMI >2 standard deviations (SD) above the median of the WHO growth reference) increased around eightfold to 5.6% in girls and 7.8% in boys 1 . Rates have plateaued at high levels in many HICs but have accelerated in other regions, particularly in parts of Asia. For the age group 2–4 years, between 1980 and 2015, obesity prevalence (IOTF definition, equivalent to an adult BMI of ≥30 kg/m 2 ) increased from 3.9% to 7.2% in boys and from 3.7% to 6.4% in girls 21 . Obesity prevalence is highest in Polynesia and Micronesia, the Middle East and North Africa, the Caribbean and the USA (Fig. 1 ). Variations in prevalence probably reflect different background levels of obesogenic environments, or the sum total of the physical, economic, policy, social and cultural factors that promote obesity 22 . Obesogenic environments include those with decreased active transport options, a ubiquity of food marketing directed towards children, and reduced costs and increased availability of nutrient-poor, energy-dense foods. Particularly in LMICs, the growth of urbanization, new forms of technology and global trade have led to reduced physical activity at work and leisure, a shift towards Western diets, and the expansion of transnational food and beverage companies to shape local food systems 23 .

Maps showing the proportions of children and adolescents living with overweight or obesity (part a , boys; part b , girls) according to latest available data from the Global Obesity Observatory . Data might not be comparable between countries owing to differences in survey methodology.

The reasons for varying sex differences in prevalence in different countries are unclear but may relate to cultural variations in parental feeding practices for boys and girls and societal ideals of body size 24 . In 2016, obesity in the age group 5–19 years was more prevalent in girls than in boys in sub-Saharan Africa, Oceania and some middle-income countries in other regions, whereas it was more prevalent in boys than in girls in all HICs, and in East and South-East Asia 21 . Ethnic and racial differences in obesity prevalence within countries are often assumed to mirror variations in social deprivation and other social determinants of obesity. However, an independent effect of ethnicity even after adjustment for socioeconomic status has been documented in the UK, with Black and Asian boys in primary school having higher prevalence of obesity than white boys 25 .

Among individuals with obesity, very high BMI values have become more common in the past 15 years. The prevalence of severe obesity (BMI ≥120% of the 95th percentile (CDC definition), or ≥35 kg/m 2 at any age 26 , 27 ) has increased in many HICs, accounting for one-quarter to one-third of those with obesity 28 , 29 . Future health risks of paediatric obesity in adulthood are well documented. For example, in a data linkage prospective study in Israel with 2.3 million participants who had BMI measured at age 17 years, those with obesity (≥95th percentile BMI for age) had a much higher risk of death from coronary heart disease (HR 4.9, 95% CI 3.9–6.1), stroke (HR 2.6, 95% CI 1.7–4.1) and sudden death (HR 2.1, 95% CI 1.5–2.9) compared with those whose BMI fell between the 5th and 24th percentiles 30 .

Causes and risk factors

Early life is a critical period for childhood obesity development 9 , 31 , 32 , 33 . According to the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease framework, the early life environment may affect organ structure and function and influence health in later life 34 , 35 . Meta-analyses have shown that preconception and prenatal environmental exposures, including high maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and, to a lesser extent, gestational weight gain, as well as gestational diabetes and maternal smoking, are associated with childhood obesity, potentially through effects on the in utero environment 33 , 36 , 37 , 38 . Paternal obesity is also associated with childhood obesity 33 . Birthweight, reflecting fetal growth, is a proxy for in utero exposures. Both low and high birthweights are associated with later adiposity, with high birthweight linked to increased BMI and low birthweight to central obesity 33 , 39 .

Growth trajectories in early life are important determinants of later adiposity. Rapid weight gain in early childhood is associated with obesity in adolescence 32 . Also, later age and higher BMI at adiposity peak (the usual peak in BMI around 9 months of age), as well as earlier age at adiposity rebound (the lowest BMI reached between 4 and 7 years of age), are associated with increased adolescent and adult BMI 40 , 41 . Specific early life nutritional factors, including a lower protein content in formula food, are consistently associated with a lower risk of childhood obesity 42 , 43 . These also include longer breastfeeding duration, which is generally associated with a lower risk of childhood obesity 42 . However, some controversy exists, as these effects are affected by multiple sociodemographic confounding factors and their underlying mechanisms remain uncertain 44 . Some studies comparing higher and lower infant formula protein content have reported that the higher protein group have a greater risk of subsequent obesity, especially in early childhood 41 , 42 ; however, one study with a follow-up period until age 11 years found no significant difference in the risk of obesity, but an increased risk of overweight in the high protein group was still observed 42 , 43 , 45 . A high intake of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated with childhood obesity 33 , 46 .

Many other behavioural factors are associated with an increased risk of childhood obesity, including increased screen time, short sleep duration and poor sleep quality 33 , 47 , reductions in physical activity 48 and increased intake of energy-dense micronutrient-poor foods 49 . These have been influenced by multiple changes in the past few decades in the broader social, economic, political and physical environments, including the widespread marketing of food and beverages to children, the loss of walkable green spaces in many urban environments, the rise in motorized transport, rapid changes in the use of technology, and the move away from traditional foods to ultraprocessed foods.

Obesity prevalence is inextricably linked to relative social inequality, with data suggesting a shift in prevalence over time towards those living with socioeconomic disadvantage, and thus contributes to social inequalities. In HICs, being in lower social strata is associated with a higher risk of obesity, even in infants and young children 50 , whereas the opposite relationship occurs in middle-income countries 51 . In low-income countries, the relationship is variable, and the obesity burden seems to be across socioeconomic groups 52 , 53 .

Overall, many environmental, lifestyle, behavioural and social factors in early life are associated with childhood obesity. These factors cannot be seen in isolation but are part of a complex interplay of exposures that jointly contribute to increased obesity risk. In addition to multiple prenatal and postnatal environmental factors, genetic variants also have a role in the development of childhood obesity (see section Mechanisms/pathophysiology).

Comorbidities and complications

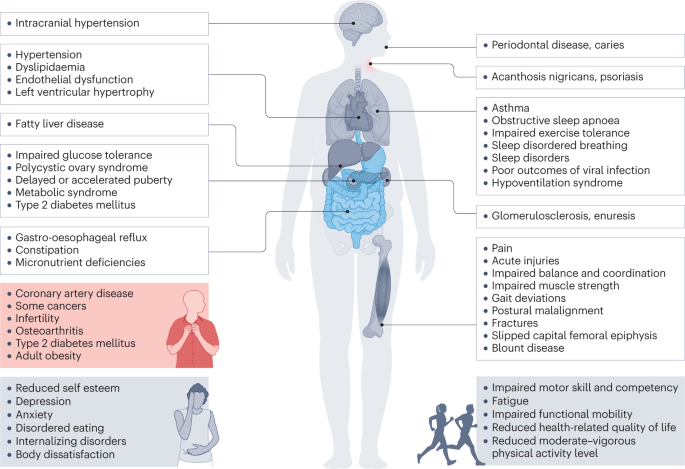

Childhood obesity is associated with a wide range of short-term comorbidities (Fig. 2 ). In addition, childhood obesity tracks into adolescence and adulthood and is associated with complications across the life course 32 , 41 , 54 , 55 .

Obesity in children and adolescents can be accompanied by various other pathologies. In addition, childhood obesity is associated with complications and disorders that manifest in adulthood (red box).

Increased BMI, especially in adolescence, is linked to a higher risk of many health outcomes, including metabolic disorders, such as raised fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), metabolic syndrome and fatty liver disease 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 . Other well-recognized obesity-associated complications include coronary heart disease, asthma, obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (itself associated with metabolic dysfunction and inflammation) 60 , orthopaedic complications and a range of mental health outcomes including depression and low self-esteem 27 , 55 , 57 , 61 , 62 , 63 .

A 2019 systematic review showed that children and adolescents with obesity are 1.4 times more likely to have prediabetes, 1.7 times more likely to have asthma, 4.4 times more likely to have high blood pressure and 26.1 times more likely to have fatty liver disease than those with a healthy weight 64 . In 2016, it was estimated that, at a global level by 2025, childhood obesity would lead to 12 million children aged 5–17 years with glucose intolerance, 4 million with T2DM, 27 million with hypertension and 38 million with fatty liver disease 65 . These high prevalence rates have implications for both paediatric and adult health services.

Mechanisms/pathophysiology

Body weight regulation.

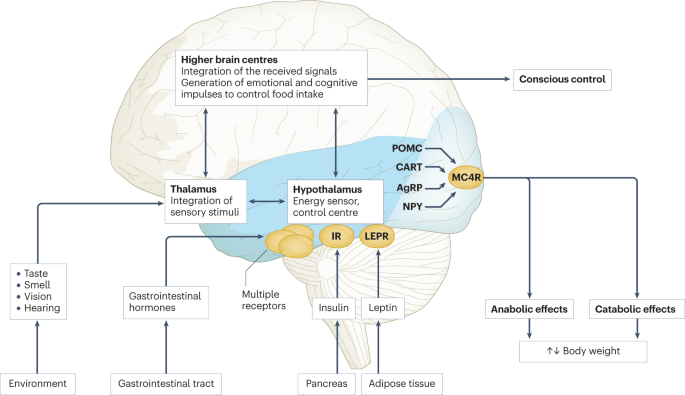

Body weight is regulated within narrow limits by homeostatic and cognitive–emotional processes and a multifactorial interplay of hormones and messenger substances in complex regulatory circuits (Fig. 3 ). When these regulatory circuits are disturbed, an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure leads to obesity or to poor weight gain. As weight loss is much harder to achieve than weight gain in the long term due to the regulation circuits discussed below, the development of obesity is encouraged by modern living conditions, which enable underlying predispositions for obesity to become manifest 8 , 66 .

Body weight is predominantly regulated by two systems: energy homeostasis and cognitive–emotional control. Both homeostatic and non-homeostatic signals are processed in the brain, involving multiple hormone and receptor cascades 217 , 218 , 219 . This overview depicts the best-known regulatory pathways. The homeostatic system, which is mainly regulated by brain centres in the hypothalamus and brainstem, operates on an unconscious level. Both long-term signals from the energy store in adipose tissue (for example, leptin) and short-term hunger and satiety signals from the gastrointestinal tract signal the current nutrient status. During gastric distension or after the release of gastrointestinal hormones (multiple receptors are involved) and insulin, a temporary feeling of fullness is induced. The non-homeostatic or hedonic system is regulated by higher-level brain centres and operates at the conscious level. After integration in the thalamus, homeostatic signals are combined with stimuli from the environment, experiences and emotions; emotional and cognitive impulses are then induced to control food intake. Regulation of energy homeostasis in the hypothalamus involves two neuron types of the arcuate nucleus: neurons producing neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP) and neurons producing pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC). Leptin stimulates these neurons via specific leptin receptors (LEPR) inducing anabolic effects in case of decreasing leptin levels and catabolic effects in case of increasing leptin levels. Leptin inhibits the production of NPY and AgRP, whereas low leptin levels stimulate AgRP and NPY production resulting in the feeling of hunger. Leptin directly stimulates POMC production in POMC neurons. POMC is cleaved into different hormone polypeptides including α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone which in turn activates melanocortin 4 receptors (MC4R) of cells in the nucleus paraventricularis of the hypothalamus, leading to the feeling of satiety. CART, cocaine and amphetamine responsive transcript; IR, insulin receptor.

In principle, there are two main systems in the brain which regulate body weight 8 , 66 (Fig. 3 ): energy homeostasis and cognitive–emotional control. Energy homeostasis is predominantly regulated by brain centres in the hypothalamus and brainstem and operates at an unconscious level. Both long-term signals from the adipose tissue energy stores and short-term hunger and satiety signals from the gastrointestinal tract signal the current nutrient status 8 , 66 . For example, negative energy balance leading to reduced fat mass results in reduced leptin levels, a permanently reduced urge to exercise and an increased feeling of hunger. During gastric distension or after the release of gastrointestinal hormones and insulin, a temporary feeling of fullness is induced 8 , 66 . Cognitive–emotional control is regulated by higher brain centres and operates at a conscious level. Here, the homeostatic signals are combined with stimuli from the environment (sight, smell and taste of food), experiences and emotions 8 , 66 . Disorders at the level of cognitive–emotional control mechanisms include emotional eating as well as eating disorders. For example, the reward areas in the brain of people with overweight are more strongly activated by high-calorie foods than those in the brain of people with normal weight 67 . Both systems interact with each other, and the cognitive–emotional system is strongly influenced by the homeostatic control circuits.

Disturbances in the regulatory circuits of energy homeostasis can be genetically determined, can result from disease or injury to the regulatory centres involved, or can be caused by prenatal programming 8 , 66 . If the target value of body weight has been shifted, the organism tries by all means (hunger, drive) to reach the desired higher weight. These disturbed signals of the homeostatic system can have an imperative, irresistible character, so that a conscious influence on food intake is no longer effectively possible 8 , 66 . The most important disturbances of energy homeostasis are listed in Table 1 .

The leptin pathway

The peptide hormone leptin is primarily produced by fat cells. Its production depends on the amount of adipose tissue and the energy balance. A negative energy balance during fasting results in a reduction of circulating leptin levels by 50% after 24 h (ref. 68 ). In a state of weight loss, leptin production is reduced 69 . In the brain, leptin stimulates two neuron types of the arcuate nucleus in the hypothalamus via specific leptin receptors: neurons producing neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP) and neurons producing pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC). High leptin levels inhibit the production of NPY and AgRP, whereas low leptin levels stimulate AgRP and NPY production. By contrast, leptin directly stimulates POMC production in POMC neurons (Fig. 3 ). POMC is a hormone precursor that is cleaved into different hormone polypeptides by specific enzymes, such as prohormone convertase 1 (PCSK1). This releases α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) which in turn activates melanocortin 4 receptors (MC4R) of cells in the nucleus paraventricularis of the hypothalamus, leading to the feeling of satiety. Rare, functionally relevant mutations in the genes for leptin and leptin receptor, POMC , PCSK1/3 or MC4R lead to extreme obesity in early childhood. These forms of obesity are potential indications for specific pharmacological treatments, for example setmelanotide 70 , 71 . MC4R mutations are the most common cause of monogenic obesity, as heterozygous mutations can be symptomatic depending on the functional impairment and with variable penetrance and expression. Other genes have been identified, in which rare heterozygous pathological variants are also associated with early onset obesity (Table 1 ).

Pathological changes in adipose tissue

Adipose tissue can be classified into two types, white and brown adipose tissue. White adipose tissue comprises unilocular fat cells and brown adipose tissue contains multilocular fat cells, which are rich in mitochondria 72 . A third type of adipocyte, beige adipocytes, within the white adipose tissue are induced by prolonged exposure to cold or adrenergic signalling, and show a brown adipocyte-like morphology 72 . White adipose tissue has a large potential to change its volume to store energy and meet the metabolic demands of the body. The storage capacity and metabolic function of adipose tissue depend on the anatomical location of the adipose tissue depot. Predominant enlargement of white adipose tissue in the visceral, intra-abdominal area (central obesity) is associated with insulin resistance and an increased risk of metabolic disease development before puberty. Accumulation of adipose tissue in the hips and flanks has no adverse effect and may be protective against metabolic syndrome. In those with obesity, adipose tissue is characterized by an increased number of adipocytes (hyperplasia), which originate from tissue-resident mesenchymal stem cells, and by enlarged adipocytes (hypertrophy) 73 . Adipocytes with a very large diameter reach the limit of the maximal oxygen diffusion distance, resulting in hypoxia, the development of an inflammatory expression profile (characterized by, for example, leptin, TNF and IL-6) and adipocyte necrosis, triggering the recruitment of leukocytes. Resident macrophages switch from the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype to a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype, which is associated with insulin resistance, further promoting local sterile inflammation and the development of fibrotic adipose tissue. This process limits the expandability of the adipose tissue for further storage of triglycerides. In the patient, the increase in fat mass in obesity is associated with insulin resistance and systemic low-grade inflammation characterized by elevated serum levels of C-reactive protein and pro-inflammatory cytokines. The limitation of adipose tissue expandability results in storage of triglycerides in other organs, such as the liver, muscle and pancreas 74 .

Genetics and epigenetics in the general population

Twin studies have found heritability estimates for BMI of up to 70% 75 , 76 . In contrast to rare monogenic forms of obesity, which are often caused by a single genetic defect with a large effect, the genetic background of childhood obesity in the general population is shaped by the joint effects of many common genetic variants, each of which individually makes a small contribution to the phenotype. For adult BMI, genome-wide association studies, which examine associations of millions of such variants across the genome at the same time, have identified around 1,000 genetic loci 77 . The largest genome-wide association studies in children, which include much smaller sample sizes of up to 60,000 children, have identified 25 genetic loci for childhood BMI and 18 for childhood obesity, the majority of which overlap 78 , 79 . There is also a clear overlap with genetic loci identified in adults, for example for FTO , MC4R and TMEM18 , but this overlap is not complete, some loci are specific to early life BMI, or have a relatively larger contribution in childhood 78 , 79 , 80 . These findings suggest that biological mechanisms underlying obesity in childhood are mostly similar to those in adulthood, but the relative influence of these mechanisms may differ at different phases of life.

The role of epigenetic processes in childhood and adolescent obesity has gained increasing attention. In children, several studies found associations between DNA methylation and BMI 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , but a meta-analysis including data from >4,000 children identified only minimal associations 85 . Most studies support the hypothesis that DNA methylation changes are predominantly a consequence rather than a cause of obesity, which may explain the lower number of identified (up to 12) associations in children, in whom duration of exposure to a higher BMI is shorter than in adults, in whom associations with DNA methylation at hundreds of sites have been identified 85 , 86 , 87 . In addition to DNA methylation, some specific circulating microRNAs have been found to be associated with obesity in childhood 84 .

The field of epigenetic studies in childhood obesity is relatively young and evolving quickly. Future studies will need to focus on defining robust associations in blood as well as other tissues and on identifying cause-and-effect relationships. In addition, other omics, such as metabolomics and proteomics, are promising areas that may contribute to an improved aetiological understanding or may provide biological signatures that can be used as predictive or prognostic markers of childhood obesity and its comorbidities.

Parental obesity and childhood obesity

There is an established link between increased parental BMI and increased childhood BMI 88 , 89 . This link may be due to shared genetics, shared environment, a direct intrauterine effect of maternal BMI or a combination of these factors. In the case of shared genetics, the child inherits BMI-increasing genetic variants from one or both parents. Shared environmental factors, such as diet or lifestyle, may also contribute to an increased BMI in both parents and child. In addition, maternal obesity might create an intrauterine environment that programmes metabolic processes in the fetus, which increases the risk of childhood obesity. Some studies show larger effects of maternal than paternal BMI, indicating a potential causal intrauterine mechanism of maternal obesity, but evidence showing similar maternal and paternal effects is increasing. The data may indicate that there is only a limited direct intrauterine effect of maternal obesity on childhood obesity; rather, genetic effects inherited from the mother or father, or both, and/or shared environmental factors may contribute to childhood obesity risk 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 .

Diagnosis, screening and prevention

Diagnostic work-up.

The extent of overweight in clinical practice is estimated using BMI based on national charts 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 . Of note, the clinical classification of overweight or obesity differ depending on the BMI charts used and national recommendations; hence, local guidelines should be referred to. For example, the US CDC Growth Charts and several others use the 85th and 95th centile cut-points to denote overweight and obesity, respectively 19 . The WHO Growth Reference for children aged 5–19 years defines cut-points for overweight and obesity as a BMI-for-age greater than +1 and +2 SDs for BMI for age, respectively 18 . For children <5 years of age, overweight and obesity are defined as weight-for-height greater than +2 and +3 SDs, respectively, above the WHO Child Growth Standards median 17 . The IOTF and many countries in Europe use cut-points of 85th, 90th and 97th to define overweight, obesity and extreme obesity 26 .

BMI as an indirect measurement of body fat has some limitations; for example, pronounced muscle tissue leads to an increase in BMI, and BMI is not independent of height. In addition, people of different ethnicities may have different cut-points for obesity risk; for example, cardiometabolic risk occurs at lower BMI values in individuals with south Asian than in those with European ancestry 101 . Thus, BMI is best seen as a convenient screening tool that is supplemented by clinical assessment and investigations.

Other measures of body fat may help differentiate between fat mass and other tissues. Some of these tools are prone to low reliability, such as body impedance analyses (high day-to-day variation and dependent on level of fluid consumption) or skinfold thickness (high inter-observer variation), or are more expensive or invasive, such as MRI, CT or dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, than simpler measures of body composition or BMI assessment.

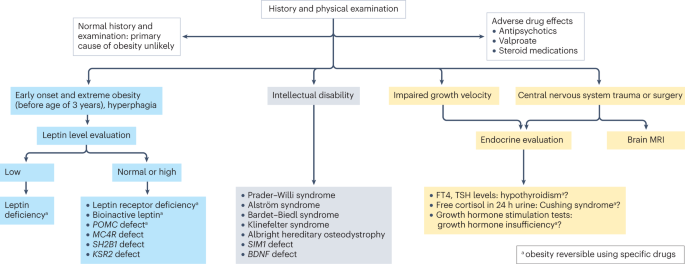

Primary diseases rarely cause obesity in children and adolescents (<2%) 102 . However, treatable diseases should be excluded in those with obesity. A suggested diagnostic work-up is summarized in Fig. 4 . Routine measurement of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is not recommended 96 . Moderately elevated TSH levels (usually <10 IU/l) are frequently observed in obesity and are a consequence, and not a cause, of obesity 103 . In a growing child with normal height velocity, a normal BMI at the age of 2 years and normal cognitive development, no further diagnostic steps are necessary to exclude primary diseases 96 , 104 .

Concerning findings from a detailed medical history and physical examination will lead to further examinations. In individuals with early onset, extreme obesity (before age 3 years) and signs of hyperphagia, serum leptin level should be measured to rule out the extremely rare condition of congenital leptin deficiency. In individuals with normal or high leptin levels, genetic testing is indicated to search for monogenetic obesity. In individuals with intellectual disability, a syndromic disease may be present. Signs of impaired growth velocity or the history of central nervous system trauma or surgery will result in deeper endocrine evaluation and/or brain MRI. BDNF , brain-derived neurotropic factor; FT4, free thyroxin; KSR2 , kinase suppressor of ras 2; MC4R , melanocortin 4 receptor; POMC , pro-opiomelanocortin; SH2B1 , Src-homology 2 (SH2) B adapter protein 1; SIM1 , single-minded homologue 1; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Clinical findings which need no further examination include pseudogynaecomastia (adipose tissue mimicking breast development; differentiated from breast tissue by ultrasonography), striae (caused by rapid weight increase) and a hidden penis in suprapubic adipose tissue (differentiated from micropenis by measurement of stretched penis length while pressing down on the suprapubic adipose tissue) 96 , 105 . Girls with obesity tend to have an earlier puberty onset (usually at around 8–9 years of age) and boys with severe obesity may have a delayed puberty onset (usually at around 13–14 years of age) 106 . Thus, if pubertal onset is slightly premature in girls or slightly delayed in boys, no further endocrine assessment is necessary.

Assessment of obesity-associated comorbidities

A waist to height ratio of >0.5 is a simple tool to identify central obesity 107 , 108 . Screening for cardiometabolic risk factors and fatty liver disease is recommended, especially in adolescents, and in those with more severe obesity or central adiposity, a strong family history of T2DM or premature heart disease, or relevant clinical symptoms, such as high blood pressure or acanthosis nigricans 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 109 . Investigations generally include fasting glucose levels, lipid profile, liver function and glycated haemoglobin, and might include an oral glucose tolerance test, polysomnography, and additional endocrine tests for polycystic ovary syndrome 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 .

T2DM in children and adolescents often occurs in the presence of a strong family history and may not be related to obesity severity 110 . T2DM onset usually occurs during puberty, a physiological state associated with increased insulin resistance 111 and, therefore, screening for T2DM should be considered in children and adolescents with obesity and at least one risk factor (family history of T2DM or features of metabolic syndrome) starting at pubertal onset 112 . As maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) type II and type III are more frequent than T2DM in children and adolescents in many ethnicities, genetic screening for MODY may be appropriate 112 . Furthermore, type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) should be excluded by measurement of autoantibodies in any individual with suspected diabetes with obesity. The differentiation of T2DM from MODY and T1DM is important as the diabetes treatment approaches differ 112 .

Several comorbidities of obesity should be considered if specific symptoms occur 96 , 109 . For polycystic ovary syndrome in hirsute adolescent girls with oligomenorrhoea or amenorrhoea, moderately increased testosterone levels and decreased sex hormone binding globulin levels are typical laboratory findings 113 . Obstructive sleep apnoea can occur in those with more severe obesity and who snore, have daytime somnolence or witnessed apnoeas. Diagnosis is made by polysomnography 114 . Minor orthopaedic disorders, such as flat feet and genu valgum, are frequent in children and adolescents with obesity and may cause pain. Major orthopaedic complications include slipped capital femoral epiphyses (acute and chronic), which manifest with hip and knee pain in young adolescents and are characterized by reduced range of hip rotation and waddling gait; and Blount disease (tibia vara), typically occurring in children aged 2–5 years 105 , 115 . In addition, children and adolescents with extreme obesity frequently have increased dyspnoea and decreased exercise capacity. A heightened demand for ventilation, elevated work of breathing, respiratory muscle inefficiency and diminished respiratory compliance are caused by increased truncal fat mass. This may result in a decreased functional residual capacity and expiratory reserve volume, ventilation to perfusion ratio abnormalities and hypoxaemia, especially when supine. However, conventional respiratory function tests are only mildly affected by obesity except in extreme cases 116 . Furthermore, gallstones should be suspected in the context of abdominal pain after rapid weight loss, which can be readily diagnosed via abdominal ultrasonography 105 . Finally, pseudotumor cerebri may present with chronic headache, and depression may present with flat affect, chronic fatigue and sleep problems 105 .

Obesity in adolescents can also be associated with disordered eating, eating disorders and other psychological disorders 117 , 118 . If suspected, assessment by a mental health professional is recommended.

A comprehensive approach

The 2016 report of the WHO Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity stated that progress in tackling childhood obesity has been slow and inconsistent, with obesity prevention requiring a whole-of-government approach in which policies across all sectors systematically take health into account, avoiding harmful health impacts and, therefore, improving population health and health equity 13 , 119 . The focus in developing and implementing interventions to prevent obesity in children should be on interventions that are feasible, effective and likely to reduce health inequalities 14 . Importantly, the voices of children and adolescents living with social disadvantage and those from minority groups must be heard if such interventions are to be effective and reduce inequalities 120 .

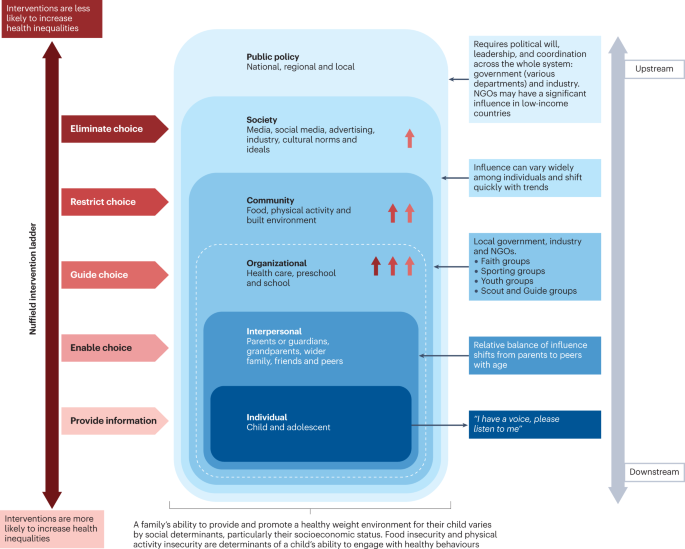

Figure 5 presents a system for the prevention of childhood obesity within different domains of the socioecological model 121 and highlights opportunities for interventions. These domains can be described on a continuum, from (most downstream) individual and interpersonal (including parents, peers and wider family) through to organizational (including health care and schools), community (including food, activity and environment), society (including media and finally cultural norms) and (most upstream) public policy (from local to national level). Interventions to prevent childhood obesity can be classified on the Nuffield intervention ladder 122 . This framework was proposed by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics in 2007 (ref. 122 ) and distributes interventions on the ladder steps depending on the degree of agency required by the individual to make the behavioural changes that are the aim of the intervention. The bottom step of the ladder includes interventions that provide information, which requires the highest agency and relies on a child, adolescent and/or family choosing (and their ability to choose) to act on that information and change behaviour. The next steps of the ladder are interventions that enable choice, guide choice through changing the default policy, guide choice through incentives, guide choice through disincentives, or restrict choice. On the top-most step of the ladder (lowest agency required) are interventions that eliminate choice.

This schematic integrates interventions that were included in a Cochrane review 127 of 153 randomized controlled trials of interventions to prevent obesity in children and are high on the Nuffield intervention ladder 122 . The Nuffield intervention ladder distributes interventions depending on the degree of agency required for the behavioural changes that are the aim of the intervention. The socioecological model 121 comprises different domains (or levels) from the individual up to public policy. Interventions targeting the individual and interpersonal domains can be described as downstream interventions, and interventions within public policy can be described as the highest level of upstream interventions. Within each of these domains, arrow symbols with colours corresponding to the Nuffield intervention ladder category are used to show interventions that were both included in the Cochrane review 127 and that guide, restrict or eliminate choice as defined by the Nuffield intervention ladder 122 . Upstream interventions, and interventions on the top steps of the Nuffield ladder, are more likely to reduce inequalities. NGO, non-governmental organization.

Downstream and high-agency interventions (on the bottom steps of the Nuffield ladder) are more likely to result in intervention-generated inequalities 123 . This has been elegantly described and evidenced, with examples from the obesity prevention literature 124 , 125 . A particularly strong example is a systematic review of 38 interventions to promote healthy eating that showed that food price (an upstream and low-agency intervention) seemed to decrease inequalities, all interventions that combined taxes and subsidies consistently decreased inequalities, and downstream high-agency interventions, especially dietary counselling, seemed to increase inequalities 126 .

Effectiveness of prevention interventions

A 2019 Cochrane review of interventions to prevent obesity in children 127 included 153 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), mainly in HICs (12% were from middle-income countries). Of these RCTs, 56% tested interventions in children aged 6–12 years, 24% in children aged 0–5 years, and 20% in adolescents aged 13–18 years. The review showed that diet-only interventions to prevent obesity in children were generally ineffective across all ages. Interventions combining diet and physical activity resulted in modest benefits in children aged 0–12 years but not in adolescents. However, physical activity-only interventions to prevent obesity were effective in school-age children (aged 5–18 years). Whether the interventions were likely to work equitably in all children was investigated in 13 RCTs. These RCTs did not indicate that the strategies increased inequalities, although most of the 13 RCTs included relatively homogeneous groups of children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The potential for negative unintended consequences of obesity prevention interventions has received much attention 128 . The Cochrane review 127 investigated whether children were harmed by any of the strategies; for example, by having injuries, losing too much weight or developing damaging views about themselves and their weight. Of the few RCTs that did monitor these outcomes, none found any harms in participants.

Intervention levels

Most interventions (58%) of RCTs in the Cochrane review aimed to change individual lifestyle factors via education-based approaches (that is, simply provide information) 129 . In relation to the socioecological model, only 11 RCTs were set in the food and physical activity environment domain, and child care, preschools and schools were the most common targets for interventions. Of note, no RCTs were conducted in a faith-based setting 130 . Table 2 highlights examples of upstream interventions that involve more than simply providing information and their classification on the Nuffield intervention ladder.