Art for Art's Sake

Summary of Art for Art's Sake

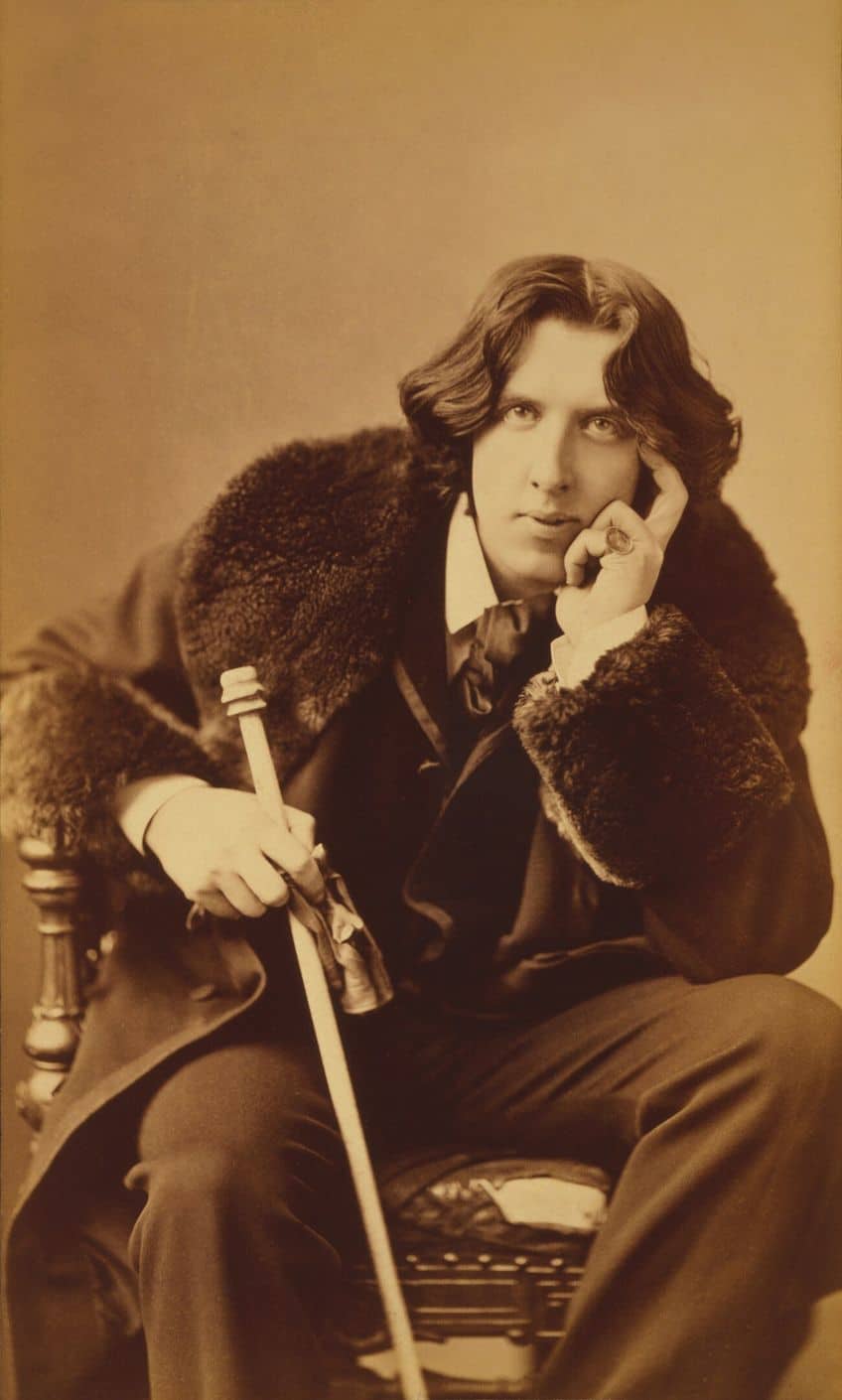

Taken from the French, the term "l'art pour l'art," (Art for Art's Sake) expresses the idea that art has an inherent value independent of its subject-matter, or of any social, political, or ethical significance. By contrast, art should be judged purely on its own terms: according to whether or not it is beautiful, capable of inducing ecstasy or revery in the viewer through its formal qualities (its use of line, color, pattern, and so on). The concept became a rallying cry across nineteenth-century Britain and France, partly as a reaction against the stifling moralism of much academic art and wider society, with the writer Oscar Wilde perhaps its most famous champion. Although the phrase has been little used since the early twentieth century, its legacy lived on in many twentieth-century ideas concerning the autonomy of art, notably in various strains of formalism .

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The idea of Art for Art's sake has its origins in nineteenth-century France, where it became associated with Parisian artists, writers, and critics, including Théophile Gautier and Charles Baudelaire . These figures and others put forward the idea that art should stand apart from all thematic, moral, and social concerns - a significant break from the post- Renaissance artistic tradition represented by contemporary academic painting , which favored historical and mythical scenes, and held that art should have a clear ethical message often connected to religion or state power.

- Although Art for Art's Sake withdrew from all political and ideological concerns, it was nonetheless radical in rejecting the moralizing standards of its day. Artists such as Aubrey Beardsley delighted in shocking polite taste through images which had sexual or grotesque overtones. In this regard, Art for Art's Sake was often implicitly radical, and its program of seeking scandal informed the more politically charged activities of subsequent movements such as Dada and Futurism .

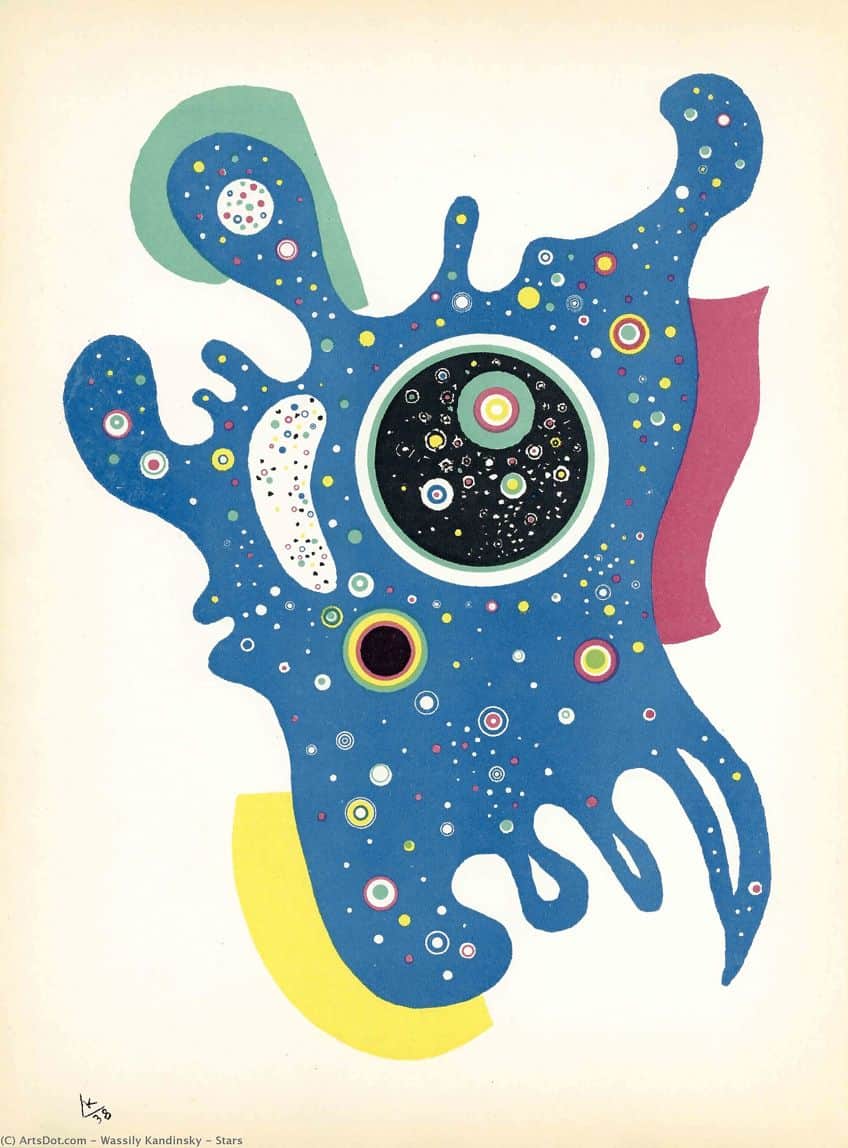

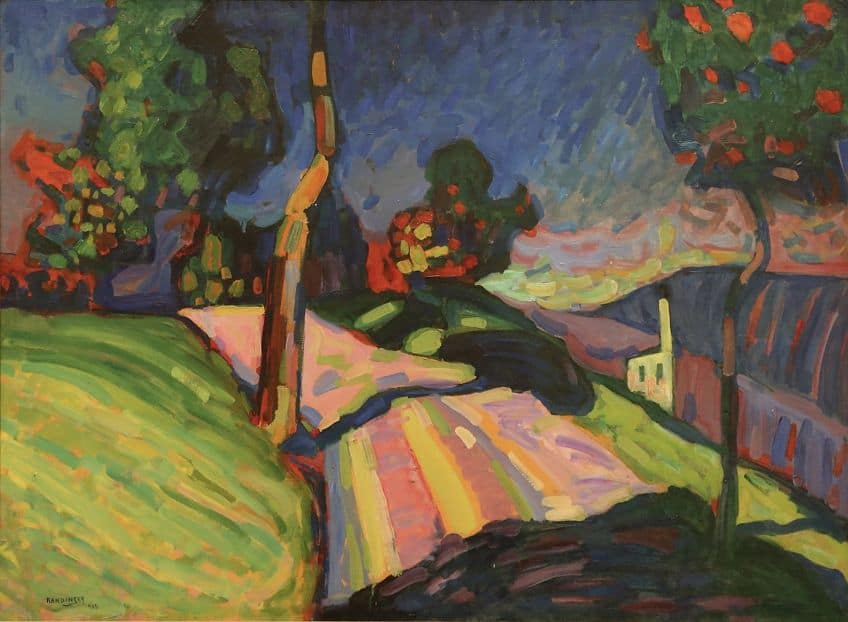

- Although the term Art for Art's Sake fell out of favor by the end of the nineteenth century, the idea it stood for - that art had a value which stood apart from subject-matter, purely connected to formal qualities such as line, color, and tone - remained highly significant. Some such notion is at the basis of all abstraction abstraction , for example. Art for Art Sake can thus be seen to have predicted the work of artists such as Wassily Kandinsky , for example, as well as the work of the Abstract Expressionists .

The Important Artists and Works of Art for Art's Sake

La Ghirlandata

Artist: Dante Gabriel Rossetti

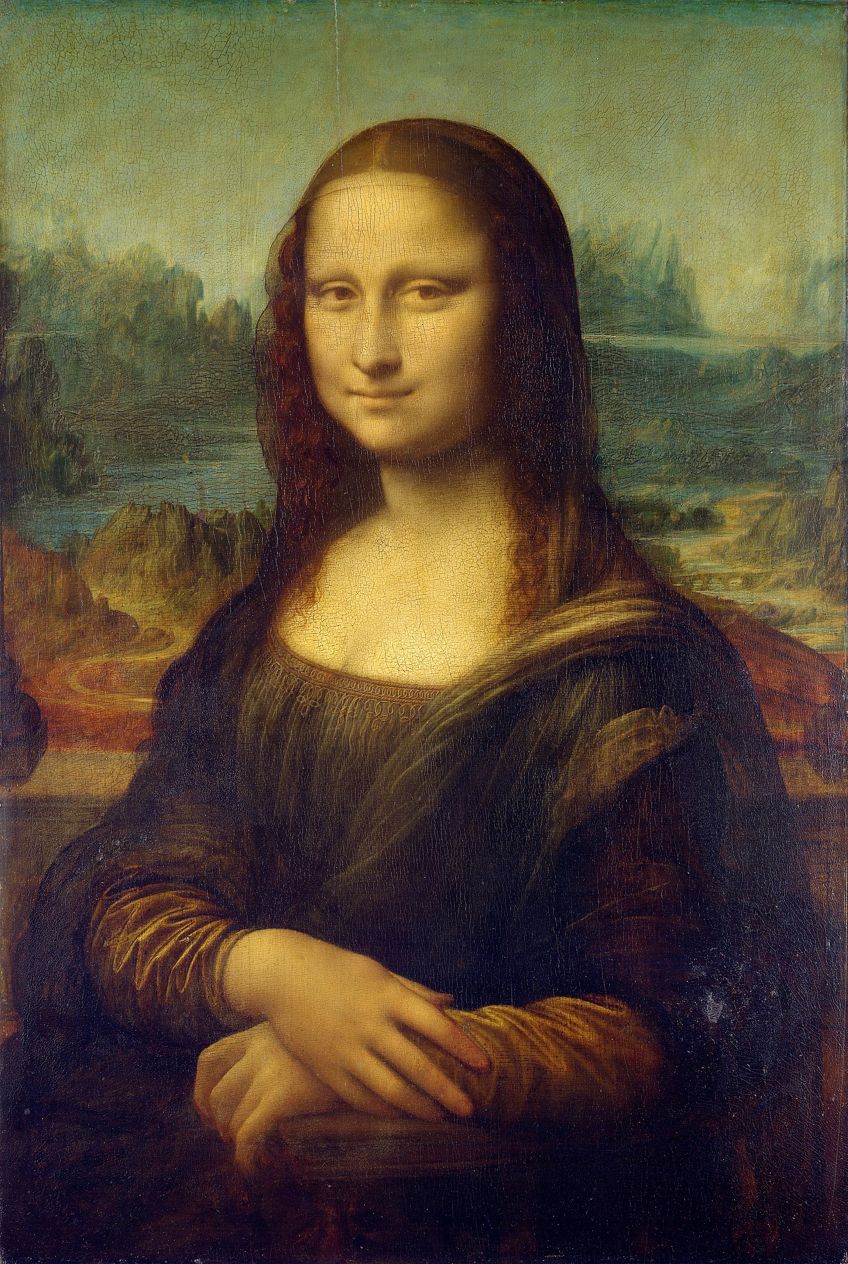

A woman delicately plays a harp while two angels circle pensively above her head. The rich velvet of the woman's green dress flows into the luxurious vegetation that surrounds her, her striking red hair echoed by the garland of flowers and the angels' auburn locks. William Michael Rossetti, the brother of the artist, translated this work's as "The Garlanded Lady" or "Lady of the Wreath," with Alexa Wilding, the model depicted in the center of the work, portrayed as the ideal of love and beauty. This is a painting by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a British artist associated with both Aestheticism and the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, and known for his tempestuous and often exploitative romantic relationships with female models and artists. This work's title, along with the idealized treatment of subject matter, may be intended to evoke the spirit of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa (c. 1503-19), then often known as La Giaconda ("the happy one" or "the jocund one"), and revered by critics associated with Art for Art's Sake such as Theophile Gautier and Walter Pater. In effect, Rossetti may have meant his idealized beauty to become an icon for the Aesthetic movement just as the Mona Lisa had become an icon of Renaissance art. In its guide to the work, the Guildhall Art Gallery notes that the painting ushered in "a new aesthetic of painting," as every element contributed to the elevation of beauty. William Michael Rossetti wrote that his brother's intent was to "to indicate, more or less, youth, beauty, and the faculty for art worthy of a celestial audience, all shadowed by mortal doom." In this respect, the painting summed up the "Cult of Beauty" for which the Pre-Raphaelites stood, and represents an important contribution to the principles of Art for Art's Sake.

Oil on canvas - Guildhall Art Gallery, London

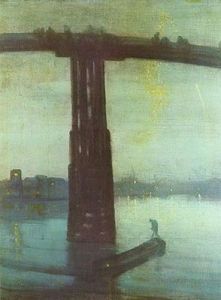

Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket

Artist: James Abbott McNeill Whistler

This iconic painting depicts a firework display at Cremorne Gardens in London. A few shadowy figures can be discerned in the foreground, depicting the shore of the Thames River, but most of the canvas is given over to the black night sky, lit up by the rocket's falling gold sparks and the explosive smoke from the firework battery on the horizon. With its dreamy wash of color and abstracted figures, this painting represented the emergence of a new approach within painting which emphasized the artist's freedom to represent a mood or emotion at the expense of representational accuracy. This painting, the last in Whistler's series of so-called "nocturnes," became important talismans of the idea of Art for Art's Sake, with the artist stating that "[a]rt should be independent of all clap-trap - should stand alone, and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear." Color and mood were crucial to Whistler's work, with his paintings often bordering on abstraction, while his titles often used musical terms such as "nocturne" and "harmony" to insist on painting's relationship to other artforms, particularly music, which had a 'pure' aesthetic quality not connected to themes or symbolism. No work is a better example of Whistler's artistic stance. Perhaps for that reason, it became the subject of legal dispute after Whistler sued the noted critic John Ruskin for attacking the painting as worthless and poorly executed. While Whistler won the case, he received only a single farthing in settlement, and his legal fees contributed to his subsequent bankruptcy. Despite this Pyrrhic victory, Whistler's defense played a key role in establishing the principles of art as an entirely liberated pursuit disconnected from all conventions of society, politics, or morality, which would be important to the development of modernism. Art critic James Jones notes that Whistler described a painting as "an arrangement of light, form and colour," an emphasis which predicts, for example, the movement of Abstract Expressionism in the mid-twentieth century.

Oil on panel - The Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, Michigan

Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room

Artist: James Whistler

The concept of Art for Art's Sake, via the Aesthetic movement, had a transformative effect on interior design and architecture. As art critic Fiona MacCarthy writes, "[o]ne of the main tenets of aestheticism was that art was not confined to painting and sculpture and the false values of the art market. Potential for art is everywhere around us, in our homes and public buildings, in the detail of the way we choose to live our lives." This photograph depicts the famous Peacock Room, named for the turquoise, gold, and blue murals featuring a peacock motif and designed by James Abbott McNeill Whistler for the home of the shipping magnate Frederick Leyland. Leyland's centerpiece for his dining room was Whistler's painting The Princess from the Land of Porcelain (1863-65), while the interior design embodied Whistler's enthusiasm for Japonism, a style based on western perceptions of Japanese art and design. Whistler described his working process in the room as spontaneous and intuitive: "I just painted on. I went on - without design or sketch - it grew as I painted. And toward the end I reached [...] a point of perfection." He said the finished interior was a "harmony in blue and gold," in effect transforming the space into an artwork and elevating design to a fine art that existed for its own sake. Whistler's design was enormously influential, informing the development of both the Anglo-Japanese style and the Aesthetic movement, which included all realms of design within its dictum. In a wider sense, the decoration of this room encapsulates the idea so important to exponents of Art for Art's Sake that, by surrounding themselves with beautiful things - not just artworks but walls, tables, chairs, and so on - the artist or art lover could become beautiful themselves.

Oil paint and gold leaf on canvas, leather, and wood - Freer Gallery of Art, Washington DC

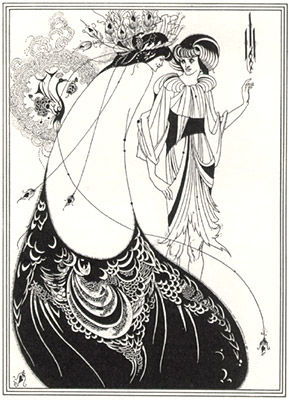

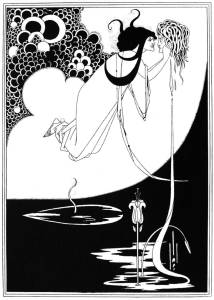

The Peacock Skirt

Artist: Aubrey Beardsley

Aubrey Beardsley's stylish ink sketch depicts the Biblical figure of Salome, whose failed seduction of John the Baptist leads to his beheading. Salome was the subject of Oscar Wilde's eponymous one-act tragedy, written in French in 1891. When the English translation was published in 1894, it contained ten woodblock illustrations based on ink sketches by Beardsley, of which The Peacock Skirt is the second. Depicting the figure of Salome to the left in a long, elaborately patterned dress, with a peacock veil and headdress, the work embodies the qualities of elaborate beauty and luxury which Beardsley and other Art-for-Art's-Sake artists promoted. At the same time, the sinister figure to the right, whose made-up face and feminine dress contrasts with their hairy legs, embraces the ideas of androgyny and sexual fluidity with which the movement was (often disapprovingly) associated. The origins of Beardsley's Salome series are in a single illustration depicting the anti-heroine kissing the severed head of John the Baptist, printed in 1893. Upon seeing the image, Wilde recognized an artistic affinity and invited Beardsley to illustrate the entire narrative. The illustration was heavily influenced by Whistler's decorations for the peacock room, as well as the stylized lines of Japanese woodblock prints; the resultant long, sinuous depiction of bodies anticipates the work of Gustave Klimt and other Art Nouveau artists. Beardsley contributed much to the Art for Art's Sake approach, in particular developing its connections with Japonism and the decorative arts. At the same time, the Salome series reflects Beardsley's interest in courting and exacerbating the scandal which the Art for Art's Sake movement was already attracting. Salome is perhaps the original femme fatale , ordering John the Baptist killed by her father Herod - himself incestuously infatuated with his daughter - after the Christian prophet refuses her sexual advances. She and her story thus represent a number of themes, such as sexual transgression, incest, and female lust, which scandalized the patriarchal, puritanical Victorian public. In focusing on her as a worthy subject of drama, Wilde and Beardsley were quite deliberately courting controversy, while promoting lifestyle choices such as plurality of gender and sexual freedom.

Woodblock Print - Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge MA.

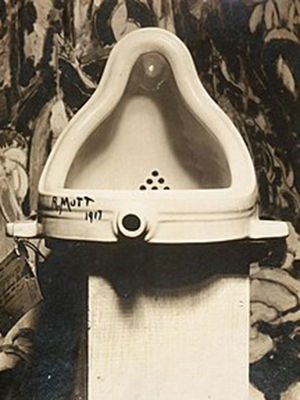

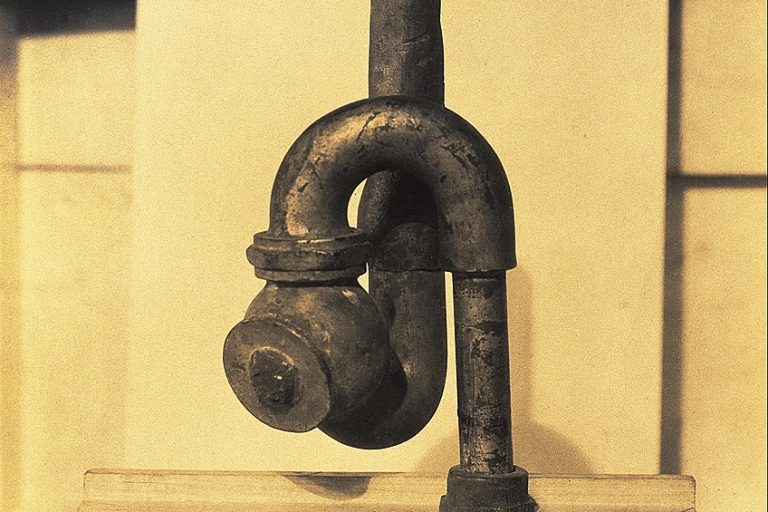

Artist: Marcel Duchamp

Duchamp's famous artwork - consisting of a mass-manufactured urinal placed on its back and signed with the artist's pseudonym R. Mutt - powerfully challenged the idea of Art for Art's Sake, while also carrying it into new realms. Fountain was submitted to the 1917 Society for Independent Artists and should have been included in the Society's annual exhibition, since membership alone granted the right to exhibit. However, the work was rejected on the grounds of immorality (proving that, despite assumptions to the contrary, other judgments - in this case, morality - did indeed inform aesthetic judgment.) This work bore almost no trace of the artist's input or - so it seemed - creative vision or skill, thus subverting the notion foundational to Art for Art's Sake that a painting or sculpture should have an inherent aesthetic or formal value. Paradoxically, however, the work's supporters did employ a version of the notion of Art for Art's Sake to defend the object, arguing that Duchamp's mere presentation the urinal imbued it with special significance, as an artwork which he had created. So, if the controversy demonstrated the fading importance of Art for Art's Sake in the 20th century, it also showed the concept's tenacity, as it became part of the foundation of modern art. As contemporary art historian Peter Bürger wrote, "the autonomy of art is a category of bourgeois society...The relative dissociation of the work of art from the praxis of life in bourgeois society thus becomes transformed into the (erroneous) idea that the work of art is totally independent of society." Bürger noted how "Duchamp's provocation not only unmasks the art market where the signature means more than the quality of the work; it radically questions the very principle of art in bourgeois society according to which the individual is considered the creator of the work of art."

Found object

Full Fathom Five

Artist: Jackson Pollock

Full Fathom Five was among the first drip paintings Jackson Pollock completed. Its surface is clotted with an assortment of detritus, from cigarette butts to coins and a key. The uppermost layers were created by pouring lines of black and shiny silver house paint, though a large part of the paint's crust was applied by brush and palette knife, creating an angular counterpoint to the weaving lines. Pollock's drip paintings have been interpreted in numerous ways, some seeing them as inventing a new abstract language for the unconscious, others suggesting that they evoke the night sky, or in this case, the depths of the ocean. However, the critic Clement Greenberg, who was Pollock's most powerful supporter, insisted that their value lay purely in their formal elements, as he believed in the inherent value of abstract art, arguing that it offered the only means by which to say something new in a world increasingly full of conventional, representational images. He also believed that formal analysis held the key to aesthetic evaluation and that discussion of all other matters - such as theme and subject matter - was irrelevant. As art historian Anna Lovatt states, "the notion of the self-reflexive, autonomous medium propounded by modernist critics - most notably Clement Greenberg," became a leading trend in the twentieth century. In effect, while the idea of Art for Art's Sake had nominally fallen out of fashion by the early twentieth century, it continued to inform trends in modern art, and its emphasis on the value of art as disconnected from all thematic concerns, became the grounds for Greenberg's concepts of medium specificity, as well as his definition of the avant-garde and his arguments in favor of abstract art. As Lovatt adds, "[b]y emphasizing the opacity and autonomy of each 'medium', Greenberg disengaged the word from its relational and communicative connotations. Thus isolated, the modernist 'medium' was objectified and reified as a thing-in-itself, abstracted from the broader conditions of artistic production and reception."

Oil on canvas, with nails, buttons, tacks, key, coins, cigarettes, matches, etc. - The Museum of Modern Art, New York City

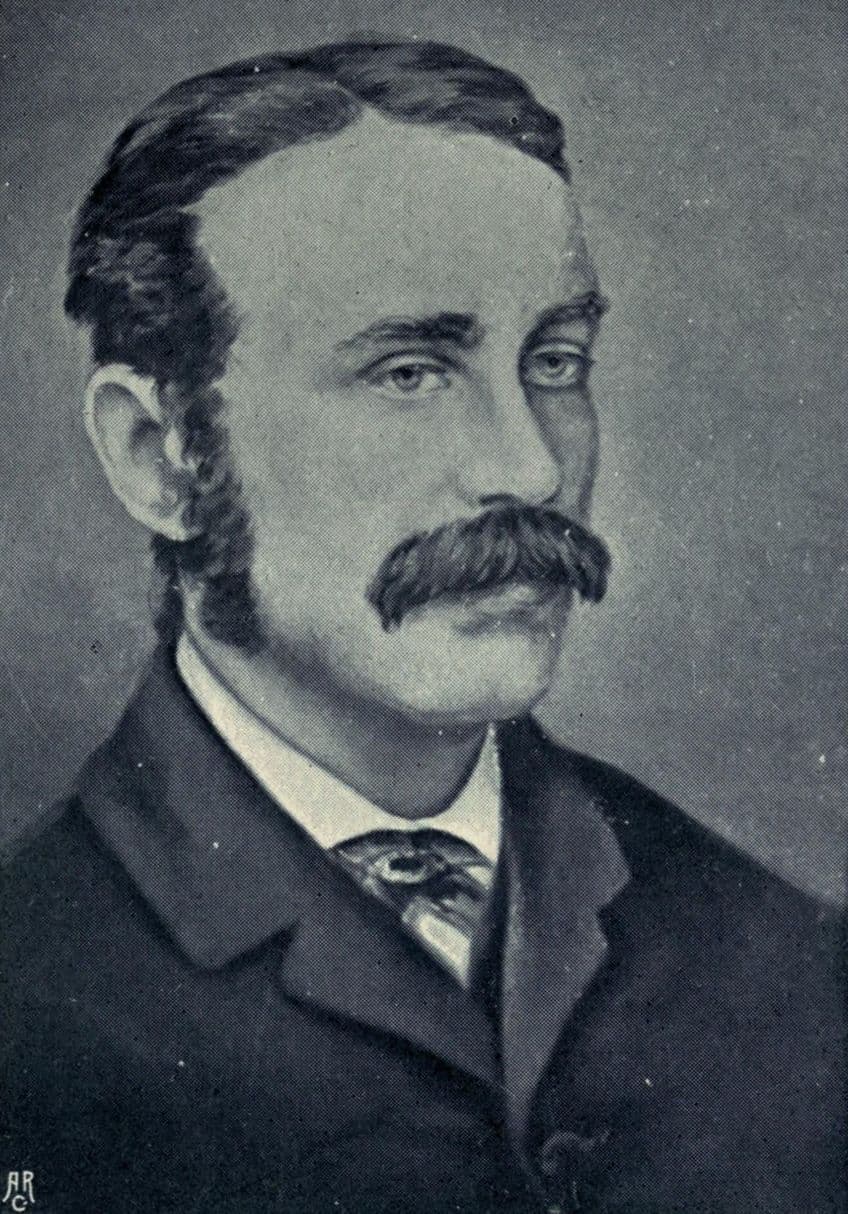

The Literary World and Théophile Gautier

The Swiss writer Benjamin Constant is thought to have been the first person to use the phrase "art for art's sake," in an 1804 diary entry. But the term is most often credited to the French philosopher Victor Cousin, who publicized it in his lectures of 1817-18. The idea of Art for Art's Sake - that art should not be judged on its relationship to social, political, or moral values, but purely for its formal and aesthetic qualities, first became popular amongst writers, encouraged by the French novelist Théophile Gautier. In the preface to his novel Mademoiselle de Maupin (1835), Gautier wrote that "nothing is really beautiful unless it is useless; everything useful is ugly."

Gautier had first studied painting before turning to literature and, subsequently, he became a leading art critic, so that he influenced both the literary and visual-art worlds. The poet Charles Baudelaire , a famous art critic in his own right, dedicated his groundbreaking poetry collection Les Fleurs du Mal (1857) to Gautier, whom he called "a perfect magician of French letters." In 1862 Gautier was elected chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (National Society of Fine Arts) by a board that included Édouard Manet , Eugène Delacroix , and Gustave Doré among others. Gautier's view that aesthetic beauty was central to the value of art, and that thematically suggestive or didactic work often lacked this quality, became widely influential in securing the reputation of the Aesthetic movement.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

The American painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler is generally credited with pioneering the concept of Art for Art's Sake within the visual arts. In his idiosyncratic art manifesto "The Red Rag" (1878) he wrote that "[a]rt should be independent of all clap-trap - should stand alone [...] and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear, without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism and the like."

Whistler's assertion that visual art should not promote any particular subject-matter led him to compare it to the purely abstract domain of music. With reference to his "nocturnes," such as Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Old Battersea Bridge (c. 1872-75), he described painting as "pure music," noting that "Beethoven and the rest wrote music [...] they constructed celestial harmonies [...] pure music."

In emphasizing the value of art for its own sake, Whistler helped to establish both the Aesthetic movement and Tonalism , the former movement having great currency in Britain, the latter in North America. In 1893, the critic George Moore, in his book Modern Painting , wrote that, "[m]ore than any other painter, Mr. Whistler's influence has made itself felt on English art. More than any other man, Mr Whistler has helped to purge art of the vice of subject and belief that the mission of the artist is to copy nature."

Aesthetic Movement

By 1860 the Aesthetic movement had emerged, coalescing around the influential idea of Art for Art's Sake, with its base in the United Kingdom. Informed by Whistler's pioneering work and Gautier's criticism, the movement became associated particularly with images of female beauty set against the decadence of the classical world, as exemplified by the work of artists such as Albert Joseph Moore and Lawrence Alma-Tadema.

Aestheticism also overlapped with the worldview of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood , including Dante Gabriel Rossetti , Edward Burne-Jones , and William Morris . These artists were wrapped up with what has been dubbed the "Cult of Beauty," a concept closely connected to the ideals of Art for Art's Sake, and suggesed that the formal power of the art work mattered above all else. However, many Pre-Raphaelites, such as Morris, were also invested in utopian politics, informed by an idealistic notion of the social structures of the medieval era. This suggests that the ideas of Art for Art's sake informed a slightly wider range of artistic philosophies than is sometimes imagined.

The canonical art critic Walter Pater became a leading proponent of Aestheticism. In his influential book The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry (1873) he stated that "art comes to you proposing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality of your moments as they pass, and simply for these moments' sake." In so doing, he extended the concept of Art for Art's Sake to define the kind of experience that a viewer should derive from a particular artwork, rather than merely applying it to the artist's intentions.

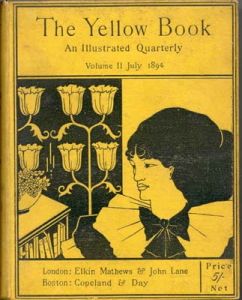

The illustrator and pen-and-ink artist Aubrey Beardsley , who died in 1898 at the age of just 25, played several important roles in the development of Aestheticism - beyond his connection with the more famous Oscar Wilde . Beardsley's sketches, critical commentaries, and editorship of The Yellow Book , a literary magazine published in London from 1894 to 1897, all left their mark on the emergence of formalistic and Decadent strains during the British fin-de-siècle (the end of the nineteenth century). In fact, the literary content of The Yellow Book often represented fairly traditional veins within art criticism, while in terms of visual layout, as the art historian Linda Dowling writes, "[the] asymmetrically placed titles, lavish margins, abundance of white space, and relatively square page declare The Yellow Book 's specific and substantial debt to Whistler." Nonetheless, the journal's garish color - which associated it with illicit French novels - and Beardsley's often uncanny and grotesque illustrations, made the journal widely influential and ensured its scandalous reputation.

Decadent Movement

The Decadent movement, which began in the 1880s, developed alongside the Aesthetic movement and shared roots in the mid-nineteenth, with Beardsley a significant figure in both schools. The Decadent movement, however, was particularly associated with France, notably with the work of the French-based Belgian artist Félicien Rops. Rops was a peer of Charles Baudelaire, who had proudly declared himself a "decadent" in his Les Fleurs du Mal ("The Flowers of Evil") (1857), after which time the term became synonymous with a rejection of nineteenth-century banality, puritanism, and sentimentality. In 1886, the publication of the magazine Le Décadent in France gave the Decadent movement its name.

Théophile Gautier, for his part, saw the principles of decadence as reflecting a point of advanced aesthetic and cultural evolution - not to say fatigue and decay - within Western societies. "Art [has] arrived at that point of extreme maturity that determines civilizations which have grown old; ingenious, complicated, clever, full of delicate hints and refinements [...] listening to translate subtle confidences, confessions of depraved passions, and the odd hallucinations of a fixed idea turning to madness." In the Decadent movement, Art for Art's Sake meant not so much an emphasis on pure formal beauty as an ostentatious rejection or mockery of the ideologies and social positions for which art might have been expected to stand.

The Decadents, arguably led by Aubrey Beardsley in Britain - who was also central to the Aesthetic movement - emphasized the erotic, the scandalous, and the disturbing. The Yellow Book pioneered the trend of decadence in art, with Beardsley's drawings rumored in the press to be filled with hidden (or not so hidden) erotic and lewd references, emphasizing his defiance of Victorian moralism. As the art historian Sabine Doran writes, "from the moment of its conception, The Yellow Book presents itself as having a close relationship with the culture of scandal; it is, in fact, one of the progenitors of this culture."

The art of Tonalism , mainly based in North America, held no truck with the scandal-seeking decadence of Beardsley and his peers. However, with their glowing, mist-filled, atmospheric landscapes, the Tonalists pioneered a style that was, in its own way, equally committed to the notion of Art for Art's Sake.

Whistler was a lodestar for these artists. As the art historian David Adams Cleveland notes, Tonalism's "emphasis on balanced design, subtle patterning, and a kind of otherworldly equipoise came directly out of the Aesthetic movement and the work and artistic philosophy of Art for Art's Sake promoted by its greatest exponent, James McNeil Whistler." In works such as Nocturne: The River at Battersea (1878), Whistler emphasized mood and atmosphere while exploring a simplified, almost abstract landscape in terms of its color tonalities.

Art critic Grace Glueck describes Tonalism as "not really a movement, but a mix of tendencies that began to drift together around 1870." "[I]t remained a style without a name," she adds, "until the mid-1890s." Tonalism became a touchstone within US art, associated in particular with the North-American painters George Inness and Albert Pinkham Ryder , as well as the photographer Edward Steichen .

Whistler vs. Ruskin

Many of the principles of Art for Art's Sake were publicly exclaimed by James Abbott McNeill Whistler during a famous libel case, which pitted his views against those of the Victorian art critic John Ruskin . The roots of the dispute were in the founding of the Grosvenor gallery in London in 1877. The gallery promoted the Aesthetic movement, and, as Fiona MacCarthy notes, became a "fashionable talking shop. The gallery's proximity to the Royal Academy polarized opinion about the techniques and purposes of art."

It was this polarization of opinion which led Ruskin, a proponent of more traditional technical and moral values within art, to dismiss Whistler's Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1875), shown in the first Grosvenor exhibition, as the equivalent of "flinging a pot of paint in the public's face." Never shy of publicity, Whistler sued Ruskin for libel, and the case came to court in 1878.

During the legal proceedings, Ruskin used a portrait of Vincenzo Catena's Portrait of the Doge, Andrea Gritti (1523-31), then thought to be painted by Titian , as an example of "real art" meant to counter Whistler's painting. By arguing his right to freedom from pre-imposed artistic standards, Whistler won the case. However, he was awarded only a single farthing in damages, and his legal expenses and the public controversy which the episode had caused severely impacted on his career, to the extent that he was forced to declare bankruptcy, subsequently moving to Paris.

Oscar Wilde and the Aesthetic Movement Teapot

Following Whistler's trial, the British public, as well as a number of powerful cultural figures, turned against the Aesthetic movement, and what they perceived as the indulgence and immorality of Art for Art's Sake. In 1881, the English dramatist W.S. Gilbert premiered Patience , a musical satirizing the leading Aesthetes, while cartoons lampooning Aestheticism appeared frequently in Punch , the leading British magazine of satire and humor.

Oscar Wilde, by this time already an established writer and a cultural celebrity, was often the target for attacks with homophobic overtones. As the art historian Sally-Anne Huxtable writes, he was "the most famous Aesthete of them all [...] at that time dressing in velvet breeches, lecturing on the topic of Art and supposedly quipping that he was 'finding it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue and white china'." In 1882, playing off the success of W.S. Gilbert's Patience , which had included a character based on Wilde called Bunthorne, the designer James Hadley, employed at the famous Royal Worcester Porcelain Factory, created his so-called Aesthetic Movement Teapot.

This piece mocks the ideals of aestheticism, particularly what was seen as its blurring of traditional gender roles. On the base of the pot appears the phrase "Fearful Consequences Through The Laws of Natural Selection & Evolution of Living up to One's Teapot," an allusion to Wilde's comment and to the idea - inferred by the public - that the Aesthetes thought they could make themselves beautiful by surrounding themselves with beautiful objects. (The line also mocks Darwin's recently published and not yet accepted theory of natural selection.) As Huxtable notes, the message of the work embodied "the self-styled 'sensible' and 'manly' world of the Victorian mainstream press", which "saw Aesthetes as effete poseurs." However, she also adds that the work became "the most iconic design object associated with British Aestheticism."

This said, the artistic debate that Hadley alluded to, masked an uglier hostility towards the homosexual tendencies seen to be wrapped up in ideas of Art for Art's Sake. Presenting a young man on one side and a young woman on the other, the teapot suggests the erosion of the traditional masculine and feminine qualities, encapsulating what Huxtable calls "the hysterical fears circulating in the 1880s about the effects that effeminacy and the blurring of gender roles might have on the future British population." These fears placed figures like Wilde in the spotlight, and in 1895, after two trials and much public scandal, he was sentenced to prison and two years' hard labor after being convicted of "gross indecency" for homosexual acts.

Concepts and Trends

The idea of aesthetic experience that informed Art for Art's Sake arguably has its roots in the work of eighteenth-century philosopher Immanuel Kant, who held that the true appreciation of art was a process disconnected from all worldly concerns. Subsequent eighteenth- and nineteenth-century artists and thinkers, including Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, and Thomas Carlyle, built upon Kant's ideas. Schiller's Briefe über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen (1795) ("On the Aesthetic Education of Man"), inspired by Kant, developed the idea that appreciating art took the viewer away from social, political, or otherwise 'non-artistic' concerns: "beauty cajoles from [man] a delight in things for their own sake." As a result, when Benjamin Constant first used the phrase "art for art's sake" in 1804, he was coining a memorable phrase that captured an already important philosophical trend.

Art Criticism

A number of nineteenth-century art critics, particularly Théophile Gautier and Walter Pater, did much to establish the ideas of Art for Art's Sake. Pater famously described the possession of an artistic sensibility as meaning "[t]o burn always with [a] hard, gem-like flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life." As art historian Rachel Gurstein writes, "[s]uch an elevated, if extravagant, ideal of art demanded a new kind of criticism that would match, and even surpass, the intensity of the impressions that a painting evoked in the sensitive viewer, and the aesthetic critic responded with ardent prose poems of his own." She adds that "proper Victorians thought such a view of art and criticism immoral and irreligious. They were appalled by what they perceived as its decadence."

Effect on Art History

With their passionate criticism, Gautier and Pater influenced the evaluation not just of contemporary art but also of the Renaissance and classical work that influenced it. Rejecting the story-telling style and moral subject-matter of classical history painting, exemplified by Raphael and favored by the traditional academies, these two critics rediscovered the work of artists such as Botticelli . Additionally, as Rochelle Gurstein writes of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa (c. 1503-19), "[a]lthough many writers associated with the art-for-art's sake movement in France and England paid enthusiastic tribute to the painting, Theophile Gautier and Walter Pater are now best known for launching it on its modern path to what is now inelegantly called 'iconicity.'"

Gautier described the "strange, almost magic charm which the portrait of Mona Lisa has for even the least enthusiastic natures." In his book The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry (1873), Pater called Mona Lisa "the symbol of the modern idea," in a lyrical passage that continues to inform our idea of what the painting represents. As Rachel Gurstein notes, "[i]n an incantatory paragraph, Pater portrayed the Mona Lisa in language that eclipsed Gautier's rhapsody and would relegate Giorgio Vasari to history. Indeed, this single passage so completely formed the imagination and the vision of art lovers who read it that no one - from Oscar Wilde to Bernard Berenson to Kenneth Clark - could speak of the Mona Lisa without uttering in the same breath that he, like everyone else of his generation, had committed Pater's luminous words to memory."

Opponents of Art for Art's Sake

From the beginning, the idea that art should be judged solely on a set of isolated aesthetic or formal criteria was opposed by a range of creatives and thinkers. Academic painters rejected the work associated with Art for Art's Sake as frivolous, lacking the moral purpose offered by the classical subjects which the Academy favored. Ruskin's criticism of Whistler's work encapsulates some aspects of this position.

Just as it was criticized by traditionalists, Art for Art's Sake also gradually fell afoul of emerging avant-garde trends in the arts. Gustave Courbet , the pioneer of Realism , generally seen as the first modern art movement, consciously distanced his aesthetic approach from Art for Art's Sake in 1854, while also rejecting the standards of the academy, presenting them as two sides of the same coin: "I was the sole judge of my painting [...] I had practiced painting not in order to make Art for Art's Sake, but rather to win my intellectual freedom."

Courbet's position anticipated that of many forward-thinking artists who felt, as the novelist George Sand wrote in 1872, that "Art for art's sake is an empty phrase. Art for the sake of truth, art for the sake of the good and the beautiful, that is the faith I am searching for." Modernism and Avant-Garde trends in art increasingly became associated not with a mere decadent rejection of academic and Victorian morals, but with the proposition of alternative social, political, and ethical ideals.

Later Developments

According to the Victoria and Albert Museum, "[t]he Aesthetic project finally ended following the scandal of the trial, conviction and imprisonment of Oscar Wilde for homosexuality in 1895. The fall of Wilde effectively discredited the Aesthetic Movement with the general public, though many of its ideas and styles remained popular into the 20th century." With the decline of the Aesthetic movement, the phrase "art for art's sake" fell out of fashion, though it continued to exert a presence, often notably, in other countries.

In St. Petersburg in 1899 Sergei Diaghilev , along with Léon Bakst and Alexandre Benois, founded the magazine Mir iskusstva ("World of Art"). The magazine was allied with a group of young artists in St. Petersburg which had formed the World of Art movement the preceding year. Promoting Art for Art's Sake and artistic individualism, the group had perhaps its greatest impact through the formation of the groundbreaking Ballets Russes, which Diaghilev founded in 1907, and which operated until 1927.

The idea of Art for Art's Sake had a profound if somewhat paradoxical influence on avant-garde art. As art historian Doug Singsen notes, "the avant-garde was not simply a negation of l'art pour l'art but rather both a negation and continuation of it." Many leading twentieth-century artists dismissed it. Pablo Picasso stated "[t]his idea of art for art's sake is a hoax," while Wassily Kandinsky wrote that "[t]his neglect of inner meanings, which is the life of colours, this vain squandering of artistic power is called 'art for art's sake.'" Nonetheless, the concept was often met with ambiguity. Kandinsky empathized with the concept to a limited extent, describing it as "an unconscious protest against materialism, against the demand that everything should have a use and practical value."

The leading art critic Clement Greenberg , who promoted Abstract Expressionism in the post-World War II era, build his concepts of medium specificity and formalism upon the groundwork of Art for Art's Sake. As art historian Anna Lovatt writes, "Greenberg expanded the concept of art's autonomy as he developed his concept of medium specificity." Contemporary art historian Paul Bürger described the concept of Art for Art's Sake as fundamental to the evolution of the avant-garde and modernism in his influential 1974 text Theory of the Avant-Garde : "the autonomy of art is a category of bourgeois society. It permits the description of art's detachment from the context of practical life as a historical development."

Social historian Rochelle Gurstein notes that "Pater's style was a harbinger of modernity." His influence continued into the twentieth century, particularly among noted critics and writers. Contemporary critic Denis Donoghue describes Pater's influence as "a shade or trace in virtually every writer of significance from [Gerard Manley] Hopkins and [Oscar] Wilde to [John] Ashbery." During the era of postmodernism in literary studies, many critics also took an interest in Pater's worldview as a precursor to modern ideas of "deconstruction." In 1991, scholar Jonathan Loesberg argued in Aestheticism and Deconstruction: Pater, Derrida, and de Man that aestheticism and modern deconstruction produced similar forms of philosophical knowledge and political effect through a process of self-questioning or "self-resistance," and through the internal critique and destabilization of hegemonic truths.

In 2011 the Victoria & Albert Museum held The Cult of Beauty exhibition on the aesthetic movement. As curator Stephen Calloway noted, "the idea of looking at an art movement where, consciously, beauty and quality are central ideas, seems to me extraordinarily timely," suggesting that Art for Art's Sake is an idea with ongoing currency in the information and opinion-saturated contemporary world.

Useful Resources on Art for Art's Sake

- Art for Art's Sake: Aestheticism in Victorian Painting Our Pick By Elizabeth Prettejohn

- The Aesthetic Movement By Lionel Lambourne

- Art for Art's Sake & Literary Life (Stages) By Gene H. Bell-Villada

- Aestheticism 1868-1900 Our Pick Google Arts and Culture

- The Theory of the Avant-Garde By Peter Bürger

- Aesthetics By Thomas Munro et al.

- The American Avant-Garde By Clement Greenberg

- Towards a Newer Laocoön Clement Greenberg

- The Mystic Smile Our Pick By Rochelle Gurstein / The New Republic / July 22,2002

- Kant and the Autonomy of Art By Casey Haskins / The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism / Vol. 47, no. 1, 1989, pp. 43-54

- The pre-Raphaelites: Art for art's sake: V&A to celebrate aesthetic movement By Mark Brown / The Guardian / September 14, 2010

- Kandinsky on "art for art's sake" By Elena Maslova-Levin / sonnetsincolour.org / December 25, 2014

- The Aesthetic Movement Our Pick By Fiona MacCarthy / The Guardian / March 26, 2011

- Art vs. aestheticism: the case of Walter Pater Our Pick By Roger Kimball / New Criterion / May 1995

- What Is Tonalism? (12 Essential Characteristics) By David Adams Cleveland / Artsy / July 10, 2015

- The Misty Mood of the Tonalists By Grace Glueck / New York Times / April 25, 1997

- Pure Art, Pure Desire: Changing Definitions of 'L'art Pour L'art' from Kant to Gautier By Margueritte Murphy / Studies in Romanticism / Bol. 47, no. 2, 2008, pp. 147-160.

- The Beginnings of l'Art Pour l'Art By John Wilcox / The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism / Vol. 11, no. 4, 1953, pp. 360-377

- INDIVIDUALISM: Art for Art's Sake, or Art for Society's Sake? By Suzi Gablik

- Ideas in Transmission: LeWitt's Wall Drawings and the Question of Medium By Anna Lovatt / Tate Papers / No.14, Autumn 2010

- The Red Rag By James McNeill Whistler / Obelisk / 1878

- Artists v critics, round one By Jonathan Jones / The Guardian / June 26, 2003

- The Historical Avant-Garde from 1830 to 1939: l'art pour l'art, blague, and Our Pick By Doug Singsen / Gesamtkunstwerk / August 30, 2020

- Théophile Gautier: Posthuman Decadence and the Philosophy of Closure Dr. Rinaldi's Horror Cabinet / August 30, 2015

- Living Up To One's Teapot: Oscar Wilde, Aestheticism and Victorian Satire Our Pick By Dr. Sally-Anne Huxtable / National Museums Scotland / March 23, 2021

- An Introduction to the Aesthetic Movement Victoria and Albert Museum

- Dangerous Ideas By Tom Ball / telos tv / October 27, 2017

- The Aesthetic Movement 1860-1900 Our Pick Victoria and Albert Museum / March 26, 2019

Related Artists

Related Movements & Topics

Content compiled and written by Rebecca Seiferle

Edited and revised, with Summary and Accomplishments added by Greg Thomas

Art for Art’s Sake – The Meaning of Art for its Own Sake

What is the meaning of art for art’s sake? Creating art for the sake of art refers to making “true” art that is not based on any practical function or tied to any specific social values. This concept has permeated several movements and styles, leaving a significant mark on the world of art through the years. Below, we explore all there is to know about the concept of art for the sake of art!

Table of Contents

- 1 The Meaning of Art for Art’s Sake

- 2.1 Important Figures

- 3 Critics of Art for Art’s Sake

- 4.1 The Aesthetic Movement

- 4.2 The Decadent Movement

- 4.3 Tonalism

- 5 Art for Art’s Sake’s Effect on Art History

- 6 The Later Developments of Art for Art’s Sake

- 7.1 Impact on Art Mediums and Art Theory

- 8.1 What Is the Meaning of Art for Art’s Sake?

- 8.2 Is Art for the Sake of Art Still Relevant Today?

The Meaning of Art for Art’s Sake

Art for the sake of art is the belief held by certain artists that art has intrinsic worth irrespective of any political, social, or ethical relevance. They believe that art should be assessed only on its own merits: whether it is aesthetically pleasing or not, and capable of creating a sense of awe in the observer through its formal features.

This idea became a rallying cry across 19th-century France and Britain, partially in response to the suffocating moralism that characterized much academic art and broader culture, with writer Oscar Wilde arguably its most prominent defender. Although the expression has seldom been employed since the early 20th century, its impact and legacy can be observed in a number of 20th-century ideas about art’s autonomy, particularly in different kinds of formalism.

The Origins of the Concept of Art for the Sake of Art

This concept can be traced back to the European Romantic movement , notably in Germany and England, when artists and intellectuals started advocating for the idea that art should be appreciated for its intrinsic characteristics rather than for any external or utilitarian role. Prior to this change, art was often considered a way of communicating certain political, religious, or moral ideas, or as a kind of social commentary. Artists were required to follow particular rules and regulations, and their artwork was judged based on its ability to represent certain concepts or ideals.

As the Romantic movement gained traction, however, there was a rising desire for artistic freedom that would break away from these restraints and enable art to exist and be enjoyed solely for its visual and emotional impact.

Important Figures

One of the significant individuals involved with the formation of the notion of art for the sake of art was Immanuel Kant, the German philosopher. Kant asserted in his important book The Critique of Judgment (1790) that the ultimate goal of art was to offer an enjoyable experience independent of any utilitarian or moral concerns. He stressed the autonomous nature of aesthetic judgments, implying that the significance and value of art lay in its ability to elicit pleasure in the observer.

Another significant individual who believed in art for art’s sake was Samuel Taylor Coleridge, a critic, and poet from England. He asserted that the essential goal of art was to provoke and communicate emotions, arguing that art should be independent of any external aim or message. Coleridge’s opinions, like those of other Romantic writers like John Keats and William Wordsworth, contributed to the emerging movement that valued art for its own inherent merits. In the 19th century, the idea of art for art’s sake continued to expand and gain popularity, notably through the works of French figures such as Charles Baudelaire, Walter Pater, and Théophile Gautier.

In his prologue to the book of poems Émaux et Camées (1852), Gautier famously wrote, “Art for art’s sake”, demonstrating how popular the idea had grown.

Being artistically inclined, according to Pater, is “to shine constantly with a hard, gem-like fire, and to preserve this ecstasy, is an accomplishment in life”. As one historian put it, “Such a heightened, if excessive, ideal of art sought a new kind of critique that would meet, and even exceed, the power of the impressions that a work of art stirred in the responsive audience, and the aesthetic critic answered with passionate poems of his own. Proper Victorians considered such a vision of art and criticism to be sinful and irreligious. They were horrified by what they considered to be debauchery”.

Critics of Art for Art’s Sake

Many artists and intellectuals have challenged the notion that art should be evaluated purely on a set of discrete aesthetic or formal standards from the start. Academic artists disagreed with the Art for Art’s Sake movement because they argued that it lacked the moral significance that the Academy’s preferred classical topics provided. Certain aspects of this perspective are expressed in Ruskin’s critique of Whistler’s artwork. Art for art’s sake was derided by the new avant-garde movements in the arts, similar to how traditionalists condemned it, despite both movements being on the extreme opposite sides of the art spectrum.

In 1854, Gustave Courbet, the founder of Realism, widely regarded as the first modern art movement , intentionally made a distinction between his aesthetic philosophy and art for art’s sake and rejected the academy’s standards, portraying them as two opposing sides of essentially the same coin: “I was the sole judge of my artwork. In order to gain my intellectual independence, I had been practicing painting, not creating art for the sake of creating art”. Courbet’s perspective mirrored that of numerous other forward-thinking artists who believed, as author George Sand said in 1872, that “art for art’s sake is a meaningless term. That is the faith I seek: art for truth’s sake, art created for the sake of the beautiful and the good”.

Avant-Garde and Modernism art movements became more closely associated with the advancement of alternative political, social, and ethical values, rather than just a hedonistic disdain of academic and Victorian standards.

Art Movements Associated with Art for Art’s Sake

Benjamin Constant, the Swiss writer, is considered to have first used the term “art for art’s sake” in a diary entry from 1804. The concept was popularized among authors, largely thanks to Théophile Gautier, the novelist from France. James Abbott McNeill Whistler , the renowned artist from the States is often considered the forefather of the idea of art for art’s sake in the visual arts. Whistler’s stance that visual art should not be used for representing a certain theme led him to equate it to the abstract sphere of music. Whistler contributed to the development of both the Aesthetic movement and Tonalism by highlighting the significance of art for the sake of art.

The Aesthetic Movement

The Aesthetic movement had begun to emerge by 1860, based in the United Kingdom, and focused on the essential principles of art for art’s sake. The movement came to be associated with depictions of feminine beauty juxtaposed against the decadent nature of the classical world, as represented by the works of painters such as Lawrence Alma-Tadema and Albert Joseph Moore, who were influenced by Whistler’s pioneering work and Gautier’s critique. Aestheticism also intersected with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s worldview, which included Edward Burne-Jones, Dante Gabriel Rossetti , and William Morris.

These artists became consumed by the “Cult of Beauty”, a concept significantly related to the principles of art for the sake of art that suggested that the formal force of the art piece was more important than anything else.

Yet, many Pre-Raphaelites, like Morris, were also involved in utopian politics, driven by an idealized view of medieval social institutions. This indicates that the concepts of art for art’s sake influenced a wider variety of artistic ideologies than is often assumed. Walter Pater rose to prominence as a strong proponent of Aestheticism. He remarked in his works that art comes to one offering openly to provide nothing but the finest qualities to one’s passing moments, merely for the sake of these moments.

In doing so, Pater broadened the idea to describe the sort of experience that someone looking at it should have from a certain artwork, instead of simply applying it to the intentions of the artist. Aubrey Beardsley, an illustrator, was also influential in the development of the Aestheticism movement. Beardsley’s editorship, drawings, and critical commentary in The Yellow Book , a literary journal published from 1894 to 1897, all had an impact on the formation of formalistic and Decadent tendencies around the turn of the century in Britain.

The Decadent Movement

Emerging in the 1880s, the Decadent movement flourished alongside the Aesthetic movement and shared its origins in the mid-19th century, with Beardsley playing an important role in both movements. The Decadent movement, though, was mostly associated with France, particularly with the artwork of Félicien Rops, a Belgian artist who lived in France. Rops was a contemporary of Charles Baudelaire, who proudly called himself a “decadent” in 1857, and the phrase grew to be associated with a rejection of 19th-century puritanism, dreariness, and sentimentality. Art for art’s sake, as defined by the Decadent movement, was an apparent rejection or mocking of the philosophies and societal positions for which art would have been expected to represent. The Decadents focused on the sexual, disturbing, and scandalous.

Beardsley’s illustrations in The Yellow Book were reported in the press to be laden with concealed erotic references, demonstrating his rejection of Victorian moralism.

Tonalism, which was mostly practiced in North America, had nothing to do with the scandal-seeking decadent nature of Beardsley and his contemporaries. The Tonalists, however, established a style that was equally dedicated to the concept of art for the sake of art, with their misty and glowing atmospheric landscapes. The Tonalism movement’s emphasis on delicate patterning, balanced design, and otherworldliness arose directly from the Aesthetic movement and the works and creative philosophies of art for the sake of art championed by its most prominent advocate, James McNeil Whistler.

He focused on mood and ambiance while experimenting with a simpler, almost abstract world in terms of color tonality. Tonalism, according to some art critics, was a collection of trends that began to converge about 1870, and was not really a unified movement. It stayed an unnamed style until the mid-1890s. Tonalism became a significant influence in American art, particularly in the work of North American artists Albert Pinkham Ryder and George Inness, in addition to Edward Steichen, the photographer.

Art for Art’s Sake’s Effect on Art History

Pater and Gautier’s intense critique affected not just the evaluation of contemporary artwork, but also of the classical and Renaissance artwork that preceded it. Rejecting the story-telling technique and ethical subject matter of classical history art, as illustrated by Raphael and celebrated by conventional academies, these two critics reexamined the works of artists like Botticelli.

Furthermore, according to Rochelle Gurstein, “while numerous authors associated with the Art for the Sake of Art movement in England and France paid enthusiastic respect to the artwork, Pater and Gautier have become most recognized for launching it on its current path to what is now inelegantly referred to as iconicity”.

Gautier emphasized the peculiar, almost magical allure that the Mona Lisa possesses for even the greatest skeptics. Pater dubbed the Mona Lisa “the emblem of the modern idea”, in a poetic statement that continues to shape our understanding of what the painting signifies. In fact, no one – from Bernard Berenson to Oscar Wilde – could speak of the painting without referring to Pater’s illuminated words, which many of them had committed to memory.

The Later Developments of Art for Art’s Sake

Following the controversy of Oscar Wilde’s trial, conviction, and incarceration in 1895 for homosexuality, the Aesthetic movement came to an end. Oscar Wilde’s fall from public grace largely discredited the Aesthetic Movement in the eyes of the people in general, but many of its concepts and forms persisted into the 20th century. With the demise of the Aesthetic movement, the expression “art for art’s sake” fell out of favor, yet it remained prominent in other countries. Léon Bakst, Sergei Diaghilev, and Alexandre Benois launched the periodical Mir Iskusstva in St. Petersburg in 1899. The journal was affiliated with the World of Art movement, which was founded the previous year by a group of young painters in St. Petersburg.

The organization, which promoted art for the sake of art and creative independence, undoubtedly had its biggest influence through the founding of the pioneering Ballets Russes, which Diaghilev formed in 1907 and managed until 1927.

The concept of art for the sake of art had a significant, if sometimes counterintuitive, impact on avant-garde art . The avant-garde was not merely a rejection of art for the sake of art, but also in many senses a continuation of it. Many prominent 20th-century painters ignored it or derided it. Pablo Picasso declared that art for the sake of art was a deception, whereas Wassily Kandinsky argued that art for the sake of art refers to the disregard of underlying meanings, which is the life of colors, and the waste of artistic power.

Despite this, the idea was often greeted with ambiguity. To a certain extent, Kandinsky understood the idea, defining it as an inner reaction against materialism, against the requirement that everything must have a utilitarian function. Clement Greenberg, a famous art critic who advocated Abstract Expressionism after WWII, based his notions of media specificity and formalism on the foundations of art for art’s sake. As he established his idea of media specificity, Greenberg broadened the concept of art’s autonomy. According to historian Paul Bürger, the theory of art for the sake of art was an important factor in the emergence of avant-garde and modernist artworks.

He considered art autonomy to be a characteristic of bourgeois society. Pater’s style foreshadowed modernism. His impact lasted well into the 20th century, especially among notable critics and authors. Many literary critics were interested in Pater’s perspective as a predecessor to current theories of deconstruction during the postmodernism era. Aestheticism and modern deconstruction, according to scholars, developed comparable kinds of philosophical knowledge through the act of self-questioning, as well as internal critique and the disruption of hegemonic beliefs.

The Influence of Art for Art’s Sake in the Modern Era

The concept of appreciating art for its inherent characteristics was fundamental in the development of many movements in the 19th and 20th centuries. Notable art movements such as Symbolism, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism , and Abstract Expressionism, welcomed the concept of art as a vehicle of personal expression and concentrated on examining the formal components of art. These movements stressed the importance of subjective interpretation and experimentation with new creative approaches to the aesthetic experience. It has additionally promoted the concepts of artistic independence and individuality in art.

Modern artists are free to follow their creative visions without any regard for external expectations or obligations.

This artistic liberation has resulted in the exploration of new concepts and materials and an erosion of established aesthetic limitations. The emphasis on aesthetic experience has become a major feature of modern art evaluation. Audiences are invited to interact with art on a far more personal level, examining their intellectual and emotional reactions. As a result, instead of depending on predetermined interpretations or messages, there is now an increased focus on the individual’s perception and experience of art.

Impact on Art Mediums and Art Theory

The idea of appreciating art for the sake of art has inspired artists to experiment with and push beyond the limits of their artistic mediums. As a result, new types of art such as installation art, performance art, video art, and digital art have emerged and flourished. These mediums typically value aesthetic enjoyment and exploration far more than the need for any practical purpose or social commentary.

This idea has spawned various theoretical debates regarding the nature and meaning of art.

It has prompted discussions regarding the importance of aesthetics, artistic autonomy, the connection between art and the society in which it was created, and the significance of artistic expression. The discourse around contemporary art has been fundamentally shaped by these conversations, and it still influences the way we make and critique art today.

Many British, French, and American authors, painters, and supporters of the Aesthetic movement, like Walter Pater, embraced the idea of art for the sake of art. It was seen as a vehement rejection of Victorian-era moralism, as well as the practice of art serving the official religion or state since the Counter-Reformation of the 16th century. The Impressionist movement and contemporary art movement were able to express themselves freely as a result of this change in direction. This idea arose in opposition to those who believed that the intrinsic value of art depended on having some moral objective. The idea of art for the sake of art is still relevant in today’s debates over censorship, as well as the nature of art in general.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the meaning of art for art’s sake.

For much of art history, artworks were produced to serve a specific function in society. They tended to be produced to communicate certain religious and political ideals. The concept of art for the sake of art, however, revolves around the idea that art should first and foremost be created and appreciated for the sheer aesthetic pleasures of art. Many notable French and English authors embraced the idea that art required no justification, that it was not required to fulfill any specific purpose, and that the aesthetic appeal of the fine arts was more than enough reason for exploring them.

Is Art for the Sake of Art Still Relevant Today?

This concept changed the way people both produced and enjoyed art. Today, artists are able to create works that are not required to meet any specific criteria or advocate any specific idea. They can produce art for the pleasure of producing art, and it can be appreciated merely for its intrinsic aesthetic qualities. This is a huge departure from the time when artists were forced to produce work to fulfill commissions from the state or religious institutes. This effectively changed art from a means of spreading propaganda to an expression of the artist’s inner world.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20 th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team .

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Art for Art’s Sake – The Meaning of Art for its Own Sake.” Art in Context. July 10, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/art-for-arts-sake/

Meyer, I. (2023, 10 July). Art for Art’s Sake – The Meaning of Art for its Own Sake. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/art-for-arts-sake/

Meyer, Isabella. “Art for Art’s Sake – The Meaning of Art for its Own Sake.” Art in Context , July 10, 2023. https://artincontext.org/art-for-arts-sake/ .

Similar Posts

Early Renaissance – Exploring the Early Italian Renaissance Art Period

Trench Art – From the Front Lines to Fine Art

What Are Artifacts? – The Historical and Cultural Value of Objects

Readymade Art – The Legacy of Repurposed Art

Post-Minimalism – A Detailed Movement Overview

Pyramids of Giza – Everything About the Great Pyramids of Giza

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Most Famous Artists and Artworks

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors…in all of history!

MOST FAMOUS ARTISTS AND ARTWORKS

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors!

Oscar Wilde on Art for Art's Sake

George p. landow.

[ Victorian Web Home —> Authors —> Aesthetes and Decadents —> Oscar Wilde —> Liteary relations ]

Wilde continues: “It is superbly sterile, and the note of its pleasure is its sterility.” Wilde, as in so much of his writing, here follows John Ruskin , who argued against both didactic art and the commonplace eighteenth-century theory that beauty in art and nature derive from utility. Wilde characteristically continues by asserting that “if the contemplation of a work of art is followed by activity of any kind, the work is either of a very second-rate order, or the spectator has failed to realise the complete artistic impression” (478). Again, one can see that Wilde does not want to function as propaganda or indoctrination, but given that, according to him, art creates a mood, it cannot be sterile, superbly or otherwise.

The sloganeering continues when Wilde adds in his second and last paragraph that “A work of art is useless as a flower is useless. A flower blossoms for its own joy. We gain a moment of joy by looking at it. That is all that is to be said about our relations to flowers. Of course man may sell the flower, and so make it useful to him, but this has nothing to do with the flower. It is not part of its essence. It is accidental, It is a misuse. All this is very obscure. But the subject is a long one” (478-79). Yes, it is, but Wilde here doesn't manage to rise above naive sentimentalism, for flowers do not blossom for their “own joy” — the very notion lapses into what Ruskin called the Pathetic (that is, emotional) Fallacy . In fact, flowers exist in a complex network of relations with their environment that includes other organisms. Throughout their history flowering plants entered into complex symbiotic relationships with insects. Later in their history, millions of years after they first evolved, they engaged human beings who worked hard to cultivate and develop flowers for their beauty. By ignoring these complex relationships, which provide the context of floral beauty, Wilde reveals the essential superficiality of the notion of art for art's sake.

Wilde of course does not really believe in Art for Art's Sake, something he makes in his richer works from “The Decay of Lying” to De Profundis .

Related material

- Aesthetes, Decadents, and the Idea of Art for Art's Sake

Bibliography

Wilde, Oscar. The Complete Letters . Ed. Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis. London: Fourth Estate, 2000.

Last modified 18 November 2017

- Increase Font Size

15 Art for Art’s Sake

Dr. Valiur Rehman

This module defines and characterizes the decadent literary movement and the critical school called Art for Art’s Sake or Aestheticism. It includes a brief literature review, etymology, genesis, and practitioners of Art for Art’s Sake along with their distinct principles and critical reception before 1960 and after.

Introduction

Art for Art’s Sake is a slogan of the literary movement Aestheticism developed in the Decadent period. The opening verse lines of John Keats’s Endymion , “A thing of beauty is a joy for ever / Its loveliness increases / it will never / Pass into nothingness” epitomize the principles represented through the slogan. Keats, therefore, is regarded as progenitor of Aestheticism.

The major pronouncement of Literature produced under the impact of Art for Art’s Sake is that Literature reveals the power of beauty and taste before its readers and audiences. Art for Art’s Sake is the trans-creation of l’art pour l’art , which has expounded the tenets of the Aestheticism. Thus, Art for Art’s Sake and Aestheticism has similar salient features as literary movements. Literally, Aestheticism is concerned with ‘a set of principles, the nature, and appreciation of beauty’ (COED 11th Edition). There are authors and artists who consciously have elevated the art to a position of supreme importance and to an autonomous sphere. Such artists or authors are the Aesthetes. They believe that the art has no social function. They attempt to separate artistry from life-description. The works of Théophile Gautier (1811-72) and his followers in France; the works of Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) and his followers in the America; and the works of Walter Horatio Pater (1839-1894) and his followers in England expounded the Art for Art’s Sake as the literary movement.

J. E. Spingarn’s essay “Art for Art’s Sake: A Query” (1907) reports that the term Art for Art’s Sake is found in Thackeray’s letter written in 1839: “Please God we shall begin, ere long, to love art for art’s sake” ( Chapter From Some Memoirs 1895). However, the literary historians think that the outset of Art for Art’s Sake is firstly observed in Victor Cousin’s series of lectures delivered in 1818, which was published later, entitled Lectures on the True, the Beautiful, and the Good (1854). Cousin mentions in the lecture:

We must have religion for religion’s sake, morality for morality’s sake, as with art for art’s sake . . . the beautiful cannot be the way to what is useful, or to what is good, or to what is holy; it leads only to itself. (Quoted in Stephen Davies et al. Companion to Aesthetics 129)

Dorothy Richardson (1873-1957), in an essay “Saintsbury and Art for Art’s Sake in England” (1944) justifies Saintsbury as the follower of the Art for Art’s Sake and the English aesthetic critic. In this essay she epitomizes the objective of Art for Art’s Sake by illustrating one of Saintsbury’s statements (1895): “The whole end, aim, and object of literature … as of all art … is beauty” (Richardson). Albert Guérard in the essay “Art for Art’s Sake” has also defined it in terms of signifying Literature as the paramount object of beauty:

Art for Art’s Sake means Art Dominant, Life for the Sake of Art, life subordinated to the service of beauty, a pilgrimage to the Land of Esthetic Promise…Art for Art’s Sake is best revealed, not in the impalpably inane, but in clashes with reality. The evangel of Beauty refuses to submit to Science, Business, Morality, the three idols of the modern world.

Frank Kermode in Romantic Image (1957) discusses Yeats’ poem “Sailing to Byzantium” in terms of Baudelaire’s concept of artificial paradise and has defined Art for Art’s Sake as the act of self-forgotten artist. Kermode clarifies it saying:

The paradise in which labour and beauty are one, where beauty is self-begotten and costs nothing, is the artificial paradise of a poet deeply disturbed by the cost in labour … The artist himself may be imagined, therefore, a change-less thing of beauty, purged of shapelessness and commonness induced by labour, himself a self-begotten and self- delighting marble or bronze.

R. V. Johnson in Aestheticism (1969) has studied the aestheticism in three different applications:

- “as a view of art,” which applies for the core principle of the literary movement Art for Art’s Sake. It expresses that the art does not produce the effect of other reasons but of its own; and that the artistry makes an object a thing of beauty. Therefore, it is not the content or the subject matter but the art that sublimates a work of art. From this perspective, perhaps, Wilde in his “The Decay of Lying” (1889) has declared that lying is the proper aim of art. ( The Artist as Critic 320)

- “as a practical tendency in literature” which applies on principle that the writer is an artist and he is not a propagandist. He is not a reporter of the lives. Frank Kermode also agrees: “Art for art’s sake is a derisory sentiment, yet questions of the morality of the work will usually be answered in terms of its perfection, not of its ‘message’.” (Kermode 195) In fact, this principle was a reaction stood against artistry for the bourgeois hedonism.

- “as a view of life” for which Johnson has used “contemplative aestheticism” which refers to the art of treating the artist’s experience to represent life through elevated spirit of art that produces the aesthetic enjoyment (p 12). The artist or the writer must have the capacity to beautify his or her experience in such a manner that an experience of light incident can influence the mind of the audience. Poe’s poem, “The Bells” posthumously published in 1849 is a fine example of onomatopoetic artistry. A diacope, or repetition and reverberation of a word “bell” evoke sentiments in the reader.

Development of Art for Art’s Sake

Art for Art’s Sake has its classical root in Alexandrian men of letters; its philosophical root in Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten’s concept of ‘aesthetics’; and its expansion in Kantian philosophy of beauty and taste. The eclectic philosopher of France, Victor Cousin was the first one to introduce l’art pour l’art to literature. The French symbolist poet and critic Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) as an aesthete influenced Walter Pater whom Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) had followed throughout his life and brought out the Aesthetic movement by advocating literature across the dichotomy of good and evil. The notorious words of Walter Pater, “The office of the poet is not that of a moralist” (Pater 1986, 427) echoed in the works of Oscar Wilde. Megan Becker-Leckrone in Julian Wolfreys’s edited book, Modern British and Irish Criticism and Theory writes in this regards, “Like Pater’s, Wilde’s concept of aesthetic autonomy belongs to and raises the stakes of this intellectual current. If art does not primarily ‘copy’ life or nature, then what does it do? Wilde’s provocative response to this question at once severs and reverses this mimetic relationship, proposing instead that ‘Life imitates Art’” (2006, 18). Thus, Walter Pater typified the Art for Art’s Sake as literary movement called Aestheticism in England while Oscar Wilde strengthened it and culminated in it.

Aesthetics is an umbrella term. It has many facets, and multicolored rib tips like aesthetics of action, aesthetics of imitation, aesthetics of imagination, aesthetics of taste, aesthetics of existence and violence etc. etc. For example, Plato’s theory of ‘imitation’ and his paradigm of the cave explore the aesthetics of the composition of Truth. Aristotle’s theory of ‘imitation’ and ‘action’ explore the aesthetics of the catharsis. Plotinus’s theory of esoteric wisdom explores the aesthetics of insulatory description of beauty, and power of the beauty to elevate man from his state of thought to the contemplation of the universe. Thus, Aesthetics as discipline, which studies the nature and appreciation of beauty, may have many dimensions to appreciate the artistic beauty whereas Aesthetic (word without /s/) is used for the literary movement emerged in the Decadent period. Aesthetic movement sublimated art as pure reason and beauty of human existence. The works, written under the impact of the Decadent literary movement, have exemplified the elements of Art for Art’s Sake.

The ideal of Art for Art’s Sake is observed in the work of four of the ablest Alexandrian men of letters who worked as librarians of the famous ancient library—Library of Alexandria, founded by Ptolemy I, the king of Egypt in 3rd BC – Zenodotus, Eratosthenes, Aristophanes of Byzantium, and Aristarchus. “All four approached literary texts as aesthetic experiences to be enjoyed; they show little interest in moralizing or allegorizing, and their one concern was with the integrity of the text.” (Kennedy 205) Nevertheless, Aesthetics could not be popularized as a discipline or a school of thought, nor could even develop the believe: ‘art lives for herself’.

The German philosopher Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten, in his dissertation “Philosophical Considerations of Some Matters Pertaining to the Poem” (1714-68) introduced the term aesthetics in 1835 to mean “a science of how things are to be known by means of the senses.” Four years later, Baumgarten had extrapolated that definition in Metaphysica adding the “logic of the lower cognitive faculty, the philosophy of the graces and the muses, lower gnoseology, the art of thinking beautifully, the art of the analog of reason.” Another decade later, Baumgarten delivered some lectures on aesthetics in Frankfurt in 1742. His Aesthetica (1750- 58), a monumental fragment, contains these lectures. It was the first treatise published under the title of the new subject. He combined his two previous definitions to form his final definition of the subject: “Aesthetics (the theory of the liberal arts, lower gnoseology, the art of thinking beautifully, the art of the analog of reason) is the science of sensitive cognition” He would appreciated ‘form’ as an important element of the beautiful work of art.

Since the Art for Art’s Sake is primarily concerned with taste and beauty, Emanuel Kant’s Critique for Judgment (1790) has its philosophic root. Kant revived A.G. Baumgarten’s term ‘aesthetics’ and experienced art as a sufficient entity of the universe. He considered aesthetics as the realm of disinterested pleasure. It pleases for its own sake. The source of pleasure is the taste of beauty. Victor Cousin elucidated Kant referentially and applied his philosophy of Taste and Beauty as an approach to understanding the art. Theophile Gautier (1811-72) wrote a ‘Preface’ to his novel Mademoiselle du Maupin (1836), formulated the classic expression of one extreme pole in the debate declaring the categorical independence of l’art pour l’art , or the art for art’s sake. Art, in Gautier’s view, is wholly opposed to utility and life.

The American poet Edger Allen Poe’s “The Poetic Principle” (1850) argues for the role and the power of beauty in the composition of the poetry:

I would define, in brief, the Poetry of words as The Rhythmical Creation of Beauty. Its sole arbiter is Taste. With the Intellect or with the Conscience, it has only collateral relations. Unless incidentally, it has no concern whatever either with Duty or with Truth.

… pleasure which is at once the most pure, the most elevating, and the most intense, is derived, I maintain, from the contemplation of the Beautiful. In the contemplation of Beauty we alone find it possible to attain that pleasurable elevation, or excitement, of the soul, which we recognize as the Poetic Sentiment, and which is so easily distinguished from Truth, which is the satisfaction of the Reason, or from Passion, which is the excitement of the heart (“The Poetic Principle”)

This definition of poetry implies poetic autonomy –the poetry does not have any concern with things other than beauty and ‘taste of beauty” which function to elevate reader’s consciousness. The German philosopher Schopenhauer, the French Gautier and American Poe influenced Charles-Pierre Baudelaire’s anti-idealist vision of art and poetry. Baudelaire encouraged symbolist movements. He wrote about the ugliest subjects in the most beautiful manner. He as an aesthetician emphasised on two things: poetic automaton and imagination. But his theory of imagination, unlike Romanticists, refers to the creative faculty of the individual which capacitates him to grasp everything as ‘hieroglyphic’( Paris Spleen & La Fanfarlo, 2008, xxvi). Romantics worshipped nature for her nurseling and nourishing power. The Nature is an inspiring force for the poets of romantic imagination whereas Baudelaire as aesthete looks at Nature as a ‘pitiless enchantress’:

And now the depth of the sky troubles me; its limpidity exasperates me. The indifference of the sea, the immutability of the scene repulses me . . . Oh, must one either suffer eternally, or eternally flee the beautiful? Nature, you pitiless enchantress, you always victorious rival, leave me alone! Stop arousing my desires and my pride! The study of the beautiful is a duel, one that ends with the artist crying out in terror before being vanquished. (“The Artist’s Confiteor” in Paris Spleen & La Fanfarlo 7)

In his “Salon” (1859), he states that “imagination is the queen of truth … affects all the other faculties; it rouses them, it sends them into combat … It is analysis, it is synthesis … It is imagination that has taught man the moral meaning of color, of outline, of sound, and of perfume.” Baudelaire thinks Poe as a true poet who believed that poetry should have no object in view other than itself. He had firm faith that a man of imagination can beautifully write about the ugliest of human life. In his words:

The whole visible universe is but a storehouse of images and signs to which imagination will give a relative place and value; it is a sort of food which the imagination must digest and transform. All the powers of the human soul must be subordinated to the imagination, which commandeers them all at one and the same time.

Baudelaire’s The Flowers of Evil (1857) became the subject of a trial for obscenity in the same year for including some lesbian poems. He never takes care of subjects – high or low, as Shelley and Arnold has instructed to choose the “best thought” expressed with “high seriousness.” The French Symbolism remained an aesthetic movement caused by a reaction against romanticism, realism, and naturalism. Baudelaire, unlike Parnassian poets of France, followed Gautier for his emphasis on independent art as the highest form of human faculty: