- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

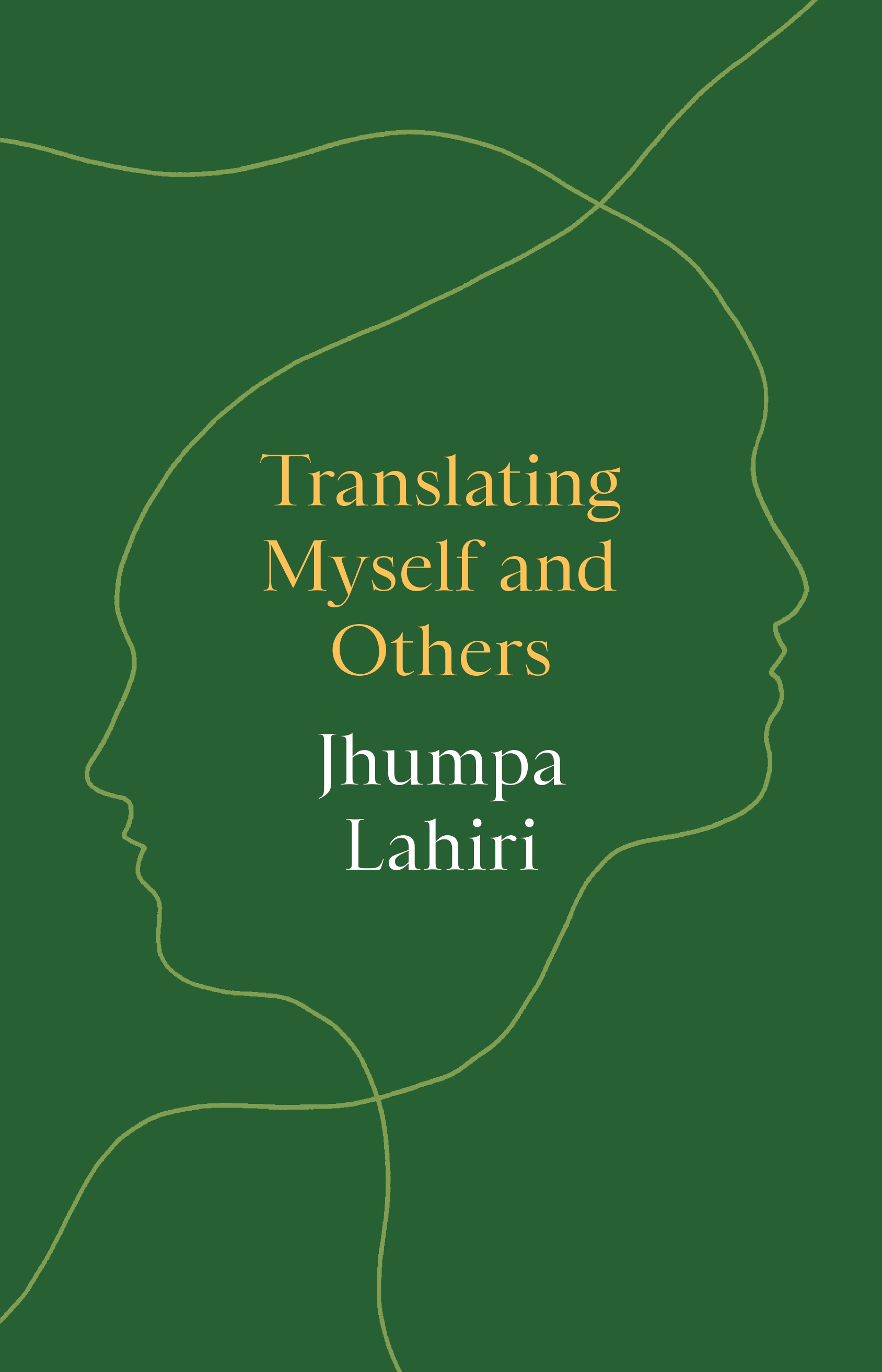

Translating Myself and Others

- Jhumpa Lahiri

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: Princeton University Press

- Copyright year: 2022

- Main content: 208

- Keywords: Writing ; Literature ; Essay ; Self-translation ; Verb ; Poetry ; Antonio Gramsci ; Writer ; Author ; Contraction (grammar) ; Noun ; Italo Calvino ; Translation ; Prose ; Afterword ; Publication ; Grammar ; Language ; Grammatical mood ; Storytelling ; Creative writing ; Adjective ; Dictionary ; Short story ; Clothing ; Allusion ; Thought ; Lingua (play) ; Linguistic system ; Analogy ; Romance languages ; Metaphor ; Interpreter of Maladies ; Preposition and postposition ; Cultural translation ; Idem ; Measurement ; Adverb ; Newspaper ; Phrase (music) ; Leonora Carrington ; Cosmopolitanism ; Sentence (linguistics) ; Listening ; Explanation ; Epigraph (literature) ; Conceit ; Dialect ; Jhumpa Lahiri ; Humour ; National language ; Spoken language ; Typesetting ; Lingua (journal) ; Scrutiny (journal) ; The Other Hand ; Audiobook ; Genre ; Glossary ; Joseph McElroy ; Literary Hub ; Illustration ; Puebloan peoples ; Novelist ; Reading (process) ; Mr. Palomar ; Dialectic ; G. K. Chesterton ; Disciplina ; Participle

- Published: May 17, 2022

- ISBN: 9780691238609

Translating Myself and Others

Jhumpa lahiri.

208 pages, Hardcover

First published May 17, 2022

About the author

Ratings & Reviews

What do you think? Rate this book Write a Review

Friends & Following

Community reviews.

“Writing in another language reactivates the grief of being between two worlds, of being on the outside. Of feeling alone and excluded.”

Writing is a way to salvage life, to give it form and meaning. It exposes what we have hidden, unearths what we have neglected, misremembered, denied. It is a method of capturing, of pinning down, but it is also a form of truth, of liberation.

Confronting a foreign language as an adult is considerable challenge. And yet, the many doors I've had to open in Italian have flung wide, opening onto a sweeping, splendid view. The Italian language did not simply change my life; it gave me a second life, an extra life.

Join the discussion

Can't find what you're looking for.

- Translating Myself and Others

In this Book

- Jhumpa Lahiri

- Published by: Princeton University Press

Luminous essays on translation and self-translation by an award-winning writer and literary translator Translating Myself and Others is a collection of candid and disarmingly personal essays by Pulitzer Prize–winning author Jhumpa Lahiri, who reflects on her emerging identity as a translator as well as a writer in two languages. With subtlety and emotional immediacy, Lahiri draws on Ovid’s myth of Echo and Narcissus to explore the distinction between writing and translating, and provides a close reading of passages from Aristotle’s Poetics to talk more broadly about writing, desire, and freedom. She traces the theme of translation in Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks and takes up the question of Italo Calvino’s popularity as a translated author. Lahiri considers the unique challenge of translating her own work from Italian to English, the question “Why Italian?,” and the singular pleasures of translating contemporary and ancient writers. Featuring essays originally written in Italian and published in English for the first time, as well as essays written in English, Translating Myself and Others brings together Lahiri’s most lyrical and eloquently observed meditations on the translator’s art as a sublime act of both linguistic and personal metamorphosis.

Table of Contents

- Title page, Copyright

- In Memoriam

- pp. vii-viii

- Introduction

- (1) Why Italian?

- (2) Containers: Introduction to Ties by Domenico Starnone

- (3) Juxtaposition: Introduction to Trick by Domenico Starnone

- (4) In Praise of Echo: Reflections on the Meaning of Translation

- (5) An Ode to the Mighty Optative: Notes of a Would-be Translator

- (6) Where I Find Myself: On Self-Translation

- (7) Substitution: Afterword to Trust by Domenico Starnone

- (8) Traduzione (stra)ordinaria / (Extra)ordinary Translation: On Gramsci

- (9) Lingua /Language

- pp. 131-140

- (10) Calvino Abroad

- pp. 141-146

- (Afterword) Translating Transformation: Ovid

- pp. 147-156

- Acknowledgments

- pp. 157-158

- Notes on the Essays

- pp. 159-160

- (Appendix) Two Essays in Italian

- pp. 161-181

- Selected Bibliography

- pp. 182-190

- pp. 191-198

Additional Information

Project MUSE Mission

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Translating Myself and Others by Jhumpa Lahiri review – the sanctuary of language

The novelist’s collection of essays on translation only hint at what led her to take refuge in Italian

T here aren’t many writers who radically remake their style over the course of their life: we might think of Joyce’s revolutions, Woolf’s renewals, or what Jeanette Winterson called the “furnace work” that Eliot undertook on his mature style for Four Quartets .

Rarer still are those who change the language they write in, but to names such as Beckett and Nabokov we can add Jhumpa Lahiri. At the turn of the millennium, Lahiri was a young star of American literature, winning a Pulitzer prize for her debut, Interpreter of Maladies . She could have carried on like that, but little over a decade later, after publication of her novel The Lowland in 2013, she stopped writing in English and took up Italian.

The results so far have been rewarding: the account of her language shift, In Other Words (2016); her extraordinary novel Whereabouts (2021); and her selections, translations and annotations for The Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories (2019), the best anthology of its kind I’ve read.

Now we have Translating Myself and Others , a collection of essays on translation. As Lahiri notes, “I was a translator before I was a writer”: her mother tongue is Bengali, and in In Other Words she wrote of the “continuous sense of estrangement” this gave her in America. Her move to Italian was perhaps a form of taking control, of choosing her own estrangement.

She writes of the appeal and challenges of writing in Italian. She feels like an impostor, a sense not alleviated when Italians ask her why she is writing “in our language”, or when a newspaper refers to her work as “my ‘Italian’ poems”. (“Why ‘Italian’ in scare quotes? Is it because I write in an Italian that’s false, spurious, slanted, nonexistent?”) She vents frustration on translation being seen as “imitative as opposed to imaginative”, and is persuasive on the difficulty of translating your own work: “There are no rules to obey when the only authority is oneself.” These self-appraisals are more interesting than the rather technical essays on other writers (three of which are on her friend Domenico Starnone’s novels).

Lahiri writes in Italian to “feel free” but also values how it makes her slow down – “I knocked on this door quite late, and it creaks a little” – and think differently, like a modernist painter who restricts herself to two colours to learn how it makes her see. A new language, she writes, is a form of blindness, but “I believe I’m blind even in English, only in reverse. Familiarity, dexterity and ease with a language can confer another form of blindness.”

That is not the only blind spot in a book that shows too little of the “myself” in the title. The hole that runs throughout is the answer to why Lahiri moved to Italy, and to Italian, in the first place. She didn’t answer it in In Other Words and she doesn’t here. Is it simply that, as Leopardi put it, “no language has enough words and phrases to correspond to and express all the infinite subtleties of thought”?

No. To return to Winterson on Eliot: “It is clear that [his] stylistic development, from The Waste Land to Four Quartets , is an emotional development of a profound order.” It is equally clear that Lahiri’s is too. But we get only hints of this momentous change: she had “run away” to Italy, “taking refuge in the Italian language in search of freedom and happiness”. One piece is written “during a particularly challenging year of my life”. Why provoke curiosity you won’t satisfy? Without seeing the input that led to the output, we feel as she does in her essay on Gramsci’s prison letters: “We experience only a single strand of a double thread.”

There is, however, a switch right at the end, in an afterword where Lahiri returns to the book best suited to any writer in the business of transformation: the Metamorphoses . “Ovid’s great poem, for me, is the sun.” She recounts the story of her mother’s decline in health, and death, in 2021, when Lahiri derives consolation from Ovid’s lines. “My soul stirs to speak of forms changed into new bodies.” Suddenly, when it is almost too late, this cool, detached book bristles with life and love.

- Jhumpa Lahiri

- The Observer

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Try unlimited access Only $1 for 4 weeks

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital.

Today's FT newspaper for easy reading on any device. This does not include ft.com or FT App access.

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- Videos & Podcasts

- FT App on Android & iOS

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Premium newsletters

- Weekday Print Edition

Essential digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Everything in Print

- Everything in Premium Digital

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

- Fairs & Events

- Watch & Listen

- Editorial Content

- Frieze Magazine

- Issue Archive

- Frieze New Writers

A free art-writing course for aspiring critics which takes place in Glasgow in the summer, supported by Frieze membership

- Frieze London

- Frieze Masters

- Frieze Los Angeles

- Frieze New York

- Frieze Seoul

- Frieze Viewing Room

- EXPO CHICAGO

- The Armory Show

- No. 9 Cork Street

- Exhibitions

- Visitor Information

- Gallery Applications

- Event Space Hire

- Frieze 91 Events

- Shows to See

- Find a Gallery

The fair returns to the Shed in New York this year with a new curator for Focus , more than 60 galleries from 25 countries and a extensive program of events and activations

- Collaborations

‘Translating Myself and Others’ Looks at Unspoken Aspects of the Practice

Released this month, jhumpa lahiri's new book explores her relationship with the italian language as a writer and translator .

Written in Italian, Jhumpa Lahiri’s 2016 book In Other Words was the first time the American author (the London-born daughter of first-generation Bengali immigrants, and brought up in Rhode Island) moved away from writing in English. Translated by Ann Goldstein, the book is a series of essays about writing in a new language; together they form a stirring meditation on the condition of departing from a long-known language or mother tongue and venturing into uncharted linguistic territory. In Other Words also masked Lahiri’s vulnerabilities: in not translating the essays herself, she denied herself a chance to interact with her adopted language in a deeper way that translation would have offered. While in Italian she was ‘a tougher, freer writer’, she did not want to know, yet, how she would fare as a translator.

Lahiri was in love with Italian, and exuberantly so. Did her ideas translate well in Italian? Did the people of Italy accept her writing a book in their mother tongue? Six years on, in the author’s latest book, Translating Myself and Others (2022), released this month, she says she wasn’t surprised to learn that they had not: ‘“ Lahiri scrive nella nostra lingua ” (‘Lahiri writes in our language’) – means that Italian remains, by definition, the language of others as opposed to my own.’ In the otherwise understated and graceful prose of this new book, there is remorse, even traces of dejection.

A collection of ten personal essays on translation and self-translation (Lahiri translated the majority of the book’s content herself, having broken out of her self-imposed exile from English), Translating Myself and Others explores the often unspoken aspects of translation as a discipline; through the course of the book, we see the writer’s interaction with Italian change and intensify. She goes beyond surface-level musings, describing both the grammatical contours of a new language and the challenges of writing in it. Lahiri explains that In Other Words was inspired by ‘the realization that I am a writer without a true mother tongue’, and after the book was published, the number of people asking ‘Why Italian?’ increased. Lahiri’s short answer: ‘I write in Italian to feel free.’

Lahiri has lived in Rome on and off for almost a decade, and learned Italian through reading the works of Italian writers, in particular Lalla Romano and Elena Ferrante, whom she cites as inspirations. In Translating Myself and Others she writes about learning the word innesto, meaning ‘graft’ (in the horticultural sense), from Ferrante’s third novel La figlia oscura (‘The Lost Daughter’ , 2006); Ferrante uses innesto against the word’s dictionary meaning, so not to denote hard work, but to indicate ‘an imperfect joint, a failure’. Lahiri explores the use of ‘graft’ not just as a literary device within the context of the novel, but as a form of toil. ‘It explains why each one of us searches for something else, something more,’ she says.

Lahiri is at her best when she writes about the Italian words that she found particularly difficult to translate – words with overlapping or multiple meanings, the kind that lead to the struggles over choice that are all-too known to every writer. The way out of this, she writes is ‘…to enter, instead, into a more profound relationship with words; we must descend with them to a deeper realm, uncovering layers of alternatives. The only way to even begin to understand language is to love it so much that we allow it to confound us, to torment us, until it threatens to swallow us whole.’ Lahiri also recounts instances when she has directly mistranslated something, and in doing so creates an honest and comprehensive portrait of a translator at work. She uses the myth of Echo and Narcissus from Ovid’s Metamorphoses as a tool to reflect on self-translation, and to unearth what it teaches us about identity, originality and finding one’s voice.

In Translating Myself and Others, Lahiri writes about how translating other people’s work out of Italian prompted her to realize that she is not only translating herself, but that she is also insecure about not being as fluent in Italian as a native speaker. However, this latest set of essays proves her skill lies in the craft of experimenting with what language can do, both in Italian and English, and both as a writer and as a translator. In a New York Times article, published this year, about the need for increased recognition in the publishing industry of the labour and skill of translators, Lahiri states that, ‘Translation requires creativity, it requires ingenuity, it requires imagination. So often, you must radically rework the text, and if that isn’t the work of imagination, I don’t know what is.’

Jhumpa Lahiri's Translating Myself and Others is available from 17 May from Princeton University Press .

Main image: Jhumpa Lahiri; photograph: Liana Miuccio

Anandi Mishra is an essayist and critic, who has worked as a reporter for The Times of India and The Hindu. Her essays and reviews have appeared in Public Books, Electric Literature, LitHub, Virginia Quarterly Review, Popula, The Brooklyn Rail and Al Jazeera.

Jhumpa Lahiri

Translation.

In her debut novel, The Extinction of Irena Rey, the writer experiments with form whilst interrogating literary theory and the politics of language

At the Hepworth Wakefield, the artist’s large-scale compositions and intimate miniatures on book covers conjure a subtle and imaginative realm

To celebrate the recent release of her memoir, The Lives of Artists, the author shares a list of literary works that have inspired her

From Greer Lankton to Cindy Sherman, Sam Moore looks at works that have subverted the doll’s sexless femininity

Gina Gammell and Riley Keough’s directorial debut showcases the grim truth of reservation life in the US

A new memoir by Alexandra Auder delves into life with her parents, Warhol superstar Viva and artist Michel Auder

Christopher Nolan explores his own political and moral uncertainties in this year’s most soul-searching blockbuster

The writer's debut novel, set in an English boarding school, explores desire, gender identity and charged dynamics

Works from the poet’s forthcoming book Listen to the Golden Boomerang Return take on a life of their own

Her new record, I Inside the Old Year Dying , looks away from present terrors to the reassurance of past mythologies

A look at the artists and activist groups caring for the social ecologies of the city

Representing the UAE at the Biennale, the artist is considered a founding member of the Emirati avant-garde of the 1980s and ’90s

Carola Grahn invited me to recreate her evolving sculpture at Bergen Kunsthall. Here’s what she taught me about reappraising the self

A conversation celebrating the release of Any Day Now: Toward a Black Aesthetic introduces the prolific writer and essayist to a new generation

© FRIEZE 2020 Cookie Settings | Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- 2023 Exhibitors

- 2024 Exhibitors

- Seoul City Guide

"> img('logo-tagline', [ 'class'=>'full', 'alt'=>'Words Without Borders Logo' ]); ?> -->

- Get Started

- About WWB Campus

- Ottaway Award

- In the News

- Submissions

Outdated Browser

For the best experience using our website, we recommend upgrading your browser to a newer version or switching to a supported browser.

More Information

Where I Find Myself

On self-translation.

Having written my novel Dove mi trovo in Italian, I was the first to doubt that it could transform into English. Naturally it could be translated; any text can, to greater or lesser degrees of success. I was not apprehensive when translators began turning the novel into other languages—into Spanish or German or Dutch, for example. Rather, the prospect gratified me. But when it came to replicating this particular book, conceived and written in Italian, into the language that I knew best—the language I had emphatically stepped away from in order for it to be born in the first place—I was of two minds.

As I was writing Dove mi trovo , the thought of it being anything other than an Italian text felt irrelevant. While writing, one must keep one’s eyes on the road, straight ahead, and not contemplate or anticipate driving down another. The dangers, for the writer as for the driver, are obvious.

And yet, even as I was writing, I felt shadowed by two questions: 1) when would the text be turned into English and 2) who would translate it? These questions rose from the fact that I am also, and was for many years exclusively, a writer in English. And so, if I choose to write in Italian, the English version immediately rears its head, like a bulb that sprouts too early in mid-winter. Everything I write in Italian is born with the simultaneous potential—or perhaps destiny is the better word here—of existing in English. Another image, perhaps jarring, comes to mind: that of the burial plot of a surviving spouse, demarcated and waiting.

The responsibility of translation is as grave and as precarious as that of a surgeon who is trained to transplant organs, or to redirect the blood flow to our hearts, and I wavered at length over the question of who would perform the surgery. I thought back to other authors who had migrated into different languages. Had they translated their own work? And if so, where did translation taper off, and the act of rewriting take over? I was wary of betraying myself. Beckett had notably altered his French when translating himself into English. Brodsky, too, took great liberties when translating his Russian poetry into English. Juan Rodolfo Wilcock, an Argentine whose major works were composed in Italian, had been more “faithful” when rendering his texts into Spanish. Another Argentine, Borges, who had grown up bilingual in Spanish and English, translated numerous works into Spanish, but left the English translation of his own work to others. Leonora Carrington, whose first language was English, had also left the messy business of translating many of her French and Spanish stories to someone else, as had the Italian writer Antonio Tabucchi in the case of Requiem , the great novel he wrote in Portuguese.

When an author migrates into another language, the subsequent crossing into the former language might be regarded, by some, as a crossing back, an act of return, a coming home. This idea is false, and it was also not my objective. Even before I decided to translate Dove mi trovo myself, I knew that the idea of “coming home” was no longer an option. I had gone too deep into Italian, and so English no longer represented the reassuring, essential act of coming up for air. My center of gravity had shifted; or at least, it had begun to shift back and forth.

I began writing Dove mi trovo in the spring of 2015. I had been living in Italy for three years, but I had already made the anguished decision to return to the United States. As with most projects, in the beginning, I had no sense that the words I was scribbling in a notebook would develop into a book. When I left Rome in August of that year, I took the notebook with me. It languished in my study in Brooklyn, though in retrospect “hibernated” is the apt term, for when I returned to Rome that winter, I found myself turning back to the notebook, which had traveled with me, and adding new scenes. The following year I moved to Princeton, New Jersey. But every two months or so I flew to Rome, either for short stays or for the summer, always with the notebook in my carry-on suitcase, and by 2017, once the notebook was full, I began to type out the contents.

In 2018, on sabbatical, I was able to move back to Rome for an entire year for the book’s publication. When asked about the English version, I said that it was still too soon to think about it. In order to undertake a translation, or even to evaluate a translation someone else has done, one must understand the particulars of the book in question, just as the surgeon, ideally, needs to study her patient’s organism before entering the operating room. I knew that I needed time—a great deal of it—to pass. I needed to gain distance from the novel, answer questions about it, hear responses from my Italian readers. For though I’d already written the book, I felt the way perhaps my own immigrant parents felt as they were raising me: the author of an inherently foreign creature, both recognizable and unrecognizable, born from my flesh and blood.

Regarding the eventual English translation, two camps quickly formed. Members of the first camp were those who urged me to translate the book myself. Their opponents urged me, with equal vehemence, to steer clear of the operation. To return to my analogy of the surgeon, I sometimes said, to members of the first camp, What surgeon, in need of an operation, would take the scalpel to herself? Wouldn’t she entrust the procedure to another pair of hands?

Following the advice of Gioia Guerzoni, an Italian translator friend who belonged to the second camp, I sought out the translator Frederika Randall, who worked out of Italian into English. Frederika was an American based in Rome for decades, not far from where I lived: the very part of the city where my book, loosely speaking (though I never specify this), is set. When she said she was willing to translate the first dozen or so pages, so that we could both get a feel for how her translation would sound, I was relieved. I was convinced that she was the ideal person to translate my novel, not only because she was an extremely skilled translator, but because she knew the setting and atmosphere of the book far better than I did.

I thought that perhaps, once she’d finished the translation, I could weigh in on one or two matters, and that my role would be respectfully collaborative. Grandmotherly, which was how I felt when Mira Nair had turned one of my other novels into a film. Perhaps this time I would be a slightly more involved grandmother than I had been to Ann Goldstein’s translation of In Other Words ( produced at a time when I was wary of any reconnection with English, and did not relish the role of being a grandmother at all). Deep down, however, I was convinced that when I saw the English version, it would reveal, brusquely and definitively, the book’s failure to function in English, not due to any fault of Frederika, but because the book itself, inherently flawed, would refuse to comply, like a potato or an apple that, decayed within, must be set aside once it is cut open and examined, and cannot lend itself to any other dish.

Italian translation, for me, has always been a way to maintain contact with the language I love when I am far away from it.

Instead, when I read the pages she prepared for me, I found that the book was intact, that the sentences made sense, and that the Italian had enough sap to sustain another text in another language. At this point a surprising thing happened. I switched camps and felt the urge to take over, just as, watching my daughter turn somersaults underwater this past summer, I, too, was inspired to learn how. Of course, that discombobulating act of flipping over, the idea of which had always terrified me until the day I finally figured out, thanks to my daughter, how to execute the maneuver, was exactly what my own book had to do. Frederika, who had lived astride English and Italian for so very long, was bipartisan to the core. She had understood, initially, why I’d been reluctant to translate the book myself, and when I told her I was having a change of heart, she wasn’t surprised. Like my daughter, she encouraged me. As is often the case when crossing a new threshold, it had taken her example, just like my daughter’s, to show me that it could be done.

I was still in Rome—a place where I feel no inspiration to work out of Italian into English—when I came to my decision. When living and writing in Rome, I have an Italian center of gravity. I needed to move back to Princeton, where I am surrounded by English, where I miss Rome. Italian translation, for me, has always been a way to maintain contact with the language I love when I am far away from it. To translate is to alter one’s linguistic coordinates, to grab on to what has slipped away, to cope with exile.

I began translating at the start of the fall semester in 2019. I didn’t look at Frederika’s sample pages; in fact, I hid them away. The book consists of forty-six relatively brief chapters. I aimed to tackle one at each sitting, two or three sittings per week. I approached the text and it greeted me like certain neighbors—if not warmly, politely enough. As I felt my way back into the book, and pressed through it, it yielded discreetly. There were roadblocks now and then, and I stopped to ponder them, or I stepped over them, determined, before stopping to think too much about what I was doing, to reach the end.

One obvious roadblock was the title itself. The literal translation, which means “where I find myself,” sounded belabored to me. The book had no English title until, at the end of October, with a few chapters still left to translate, I stepped on a plane to go to Rome. Not long after takeoff, “whereabouts” popped into my brain. A word as inherently English, and as fundamentally untranslatable, as the expression dove mi trovo is in Italian. Somewhere in the air, over the waters that separate my English and Italian lives, the original title recognized itself—dare I say found itself—in another language.

Once I finished the first draft, I circulated it to a small group of readers who did not read Italian, who knew me well, and only, as a writer in English. Then I waited, anxiously, even though the book had already been born over a year before, and was already living, not only in Italian but, as previously mentioned, in other languages as well. It was only after these readers told me the book had spoken to them that I believed that the foolhardy operation I had performed on myself had not been in vain.

As Dove mi trovo was turning into Whereabouts , I naturally had to keep referring back to the original book I’d written. I began to notice a few repetitions in the Italian I wished I’d caught. Certain adjectives I was relying on too heavily. A few inconsistencies. I had miscounted the number of people at a dinner party, for example. I began to mark the Italian book with adhesive arrows, and then to keep a list to send to my Italian editors at Guanda, so that certain changes could be made in subsequent editions of the book. In other words, the second version of the book was now generating a third: a revised Italian text that was stemming from my self-translation. When translating oneself, each and every flaw or weakness in the former text becomes immediately and painfully apparent. Keeping to my medical metaphors, I would say that self-translation is like one of those radioactive dyes that enable doctors to look through our skin to locate damage in the cartilage, unfortunate blockages, and other states of imperfection.

Some people insist that there is no such thing as self-translation.

As discomfiting as this process of revelation was, I felt a parallel gratitude for the very ability to isolate these problems, to be aware of them and to find new solutions. The brutal act of self-translation frees oneself, once and for all, from the false myth of the definitive text. It was only by self-translating that I finally understood what Valéry meant when he said that a work of art was never finished, only abandoned. The publication of any book is an arbitrary act; there is no ideal phase of gestation, nor of birth, as is the case for living creatures. A book is done when it seems done, when it feels done, when the author is sick of it, or is eager to publish it, or when the editor wrests it away. All of my books, in retrospect, feel premature. The act of self-translation enables the author to restore a previously published work to its most vital and dynamic state—that of a work-in-progress—and to repair and recalibrate as needed.

Some people insist that there is no such thing as self-translation, and that it necessarily becomes an act of rewriting or emphatically editing—read: improving—the first go-around. This temptation attracts some and repels others. I personally was not interested in altering my Italian book in order to arrive at a more supple, elegant, and mature version of it in English. My aim was to respect and reproduce the novel I had originally conceived, but not so blindly as to reproduce and perpetuate certain infelicities.

As Whereabouts moved through copyediting to typeset pages, with different editors and proofreaders weighing in, so did the changes to Dove mi trovo continue to accumulate—I repeat, all relatively minor, but nevertheless significant to me. The two texts began to move forward in tandem, each on its own terms. When the paperback of Dove mi trovo eventually comes out in Italian—at the time of writing, it hasn’t yet—I will consider it the definitive version, at least for now, given that I have come to think of any “definitive text” largely the same way that I think of a mother tongue, at least in my case: an inherently debatable, perpetually relative concept.

The first day I sat down with the page proofs of Whereabouts , during the autumn of the coronavirus pandemic, I went to Firestone Library, at Princeton, booking a seat and taking my place at a round white marble table. I was masked and many feet away from the other three people allowed in a room that could easily hold one hundred. I realized that day, when pausing to question something in the English text, that I had left my battered copy of Dove mi trovo at home. The translator side of me, focused on bringing the book into English, was already subconsciously distancing and disassociating from the Italian. Of course, it is always strange, and also crucial, at the last stage of looking at a translation, to all but disregard the text in the original language. The latter cannot be hovering, as I did when my children first went off to school, somewhere in the building, alert to cries of protest. A true separation, as false as that is, must occur. In the final stages of reviewing a translation, either of one’s own work or someone else’s, one achieves a level of concentration that is akin to focusing purely on the quality and sensations of the water when one is swimming in the sea, as opposed to admiring elements that float through it or collect on the seabed. When one is so focused on language, a selective blindness sets in, and along with it, a form of X-ray vision.

Reading over the page proofs of Whereabouts in English, I began reflecting in my diary, in Italian, on the process of having translated it. In fact, the text you are now reading, which I’ve written in English, is a product of notes taken in Italian. In some sense, this is the first piece of writing that I have conceived bilingually, and so the subject, self-translation, feels especially appropriate. Here, in translation, are some of the notes I took:

1. The profoundly destabilizing thing about self-translation is that the book threatens to unravel, to hurtle toward potential annihilation. It seems to annihilate itself. Or am I annihilating it? No text should sustain that level of scrutiny; at a certain point, it cedes. It’s the reading and the scrutinizing, the insistent inquiry implicit in the act of writing and translating, that inevitably jostles the text.

2. This task is not for the faint of heart. It forces you to doubt the validity of every word on the page. It casts your book—already published, between covers, sold on shelves in stores—into a revised state of profound uncertainty. It is an operation that feels doomed from the start, even contrary to nature, like the experiments of Victor Frankenstein.

3. Self-translation is a bewildering, paradoxical going backward and moving forward at once. There is ongoing tension between the impulse to plow ahead undermined by a strange gravitational force that holds you back. One feels silenced in the very act of speaking. Those two dizzying tercets from Dante come to mind, with their language of doubling and their contorted logic: “Qual è colui che suo dannaggio sogna, / che sognando desidera sognare, / sì che quel ch’è, come non fosse, agogna, / tale me fec’io, non posando parlare, / che disiava scusarmi, e scusava / me tuttavia, e nol mi credea fare.” (Like one asleep who dreams himself in trouble / and in his dream he wishes he were dreaming, / longing for that which is, as if it were not, / just so I found myself: unable to speak, / longing to beg for pardon and already / begging for pardon, not knowing what I did.” (Inferno XXX, 136-141) 1

4. Reading the English, every sentence that felt off, that had gone astray in the translation, always led me back to a misreading of myself in Italian.

5. Whereabouts will emerge on its own, without the Italian text on the facing page, as was the case with In Other Words . But if anything, the absence of the Italian reinforces, for me, the bond between these two versions, one of which I wrote, and one of which I translated. These two versions have entered into a tennis match. But in fact, it’s the ball that represents both texts, volleyed from one side of the net over the other and back again.

6. Self-translation means prolonging your relationship to the book you’ve written. Time expands and the sun still shines when you expect things to go dark. This disorienting surplus of daylight feels unnatural, but it also feels advantageous, magical.

7. Self-translation affords a second act for a book, but in my opinion, this second act pertains less to the translated version than to the original, which is now readjusted and realigned thanks to the process of being dismantled and reassembled.

8. What I altered in Italian was what, in hindsight, still felt superfluous to my view. The stringent quality of English forced the Italian text, at times, to tighten its belt as well.

In some sense the book remains Italian in my head in spite of its metamorphosis into English.

9. I suppose the exhilarating aspect of translating myself was being constantly reminded, as I changed the words from one language to another, that I myself had changed so profoundly, and that I was capable of such change. I realized that my relationship to the English language, thanks to my linguistic graft, had also been irrevocably altered.

10. Whereabouts will never be an autonomous text in my mind, nor will the paperback of Dove mi trovo , which is now indebted to the process of first translating and then revising Whereabouts . They share the same vital organs. They are conjoined twins, though, on the surface, they bear no resemblance to one another. They have nourished and been nourished by the other. Once the translation was in progress, I almost felt like a passive bystander as they began sharing and exchanging elements between themselves.

11. I believe I began writing in Italian to obviate the need to have an Italian translator. As grateful as I am to those who have rendered my English books into Italian in the past, something was driving me, in Italian, to speak for myself. I have now assumed the role I had set out to eliminate, only in the inverse. Becoming my own translator in English has only lodged me further inside the Italian language.

12. In some sense the book remains Italian in my head in spite of its metamorphosis into English. The adjustments I made in English were always in service to the original text.

In reviewing the proofs of Whereabouts , I noticed a sentence I’d skipped entirely in the English. It has to do with the word portagioie, which, in the Italian version, the protagonist considers the most beautiful word in the Italian language. But the sentence only carries its full weight in Italian. The English equivalent of portagioie , “jewelry box,” doesn’t contain the poetry of portagioie, given that joys and jewels are not the same thing in English. I inserted the sentence into the translation, but had to alter it. This is probably the most significantly reworked bit of the book, and I added a footnote for clarification. I had hoped to avoid footnotes, but in this case, the me in Italian and the me in English had no common ground.

The penultimate chapter of the novel is called Da nessuna parte . I translated it as “Nowhere” in English, which breaks the string of prepositions in the Italian. An Italian reader pointed this out, suggesting I translate it more literally as “In no place.” I considered making the change, but in the end my English ear prevailed, and I opted for an adverb which, to my satisfaction, contains the “where” of the title I’d come up with.

There was one instance of grossly mistranslating myself. It was a crucial line, and I only caught the error in the final pass. As I was reading the English proofs aloud for the last time, without referring back to the Italian, I knew the sentence was wrong, and that I had completely, unintentionally mangled the meaning of my own words.

It also took several readings to correct an auxiliary verb in English that the Italian side of my brain, in the act of translating, had rendered sloppily. In English one takes steps, but in Italian one makes them. Given that I read and write in both languages, my brain has developed blind spots. It was only by looking again and again at the English that I saved a character in Whereabouts from “making steps.” Having said this, in English, it is possible to make missteps.

In the end, the hardest thing about translating Whereabouts were the lines written not by me but by two other writers: Italo Svevo—whom I cite in the epigraph—and Corrado Alvaro, whom I cite in the body of the text. Their words, not mine, are the ones I feel ultimately responsible for, and have wrestled with most. These are the lines I will continue to fret over even when the book goes to press. The desire to translate—to press up as closely as possible to the words of another, to cross the threshold of one’s consciousness—is keener when the other remains inexorably, incontrovertibly out of reach.

I believe it was important to have gained experience translating other authors out of Italian before confronting Dove mi trovo. The upsetting experience of trying to translate myself early on in the process of writing in Italian, which I briefly touched upon in In Other Words , had a lot to do with the fact that I had yet to translate out of Italian. All my energy back then was devoted to sinking deeper into the new language and avoiding English as much as possible. I had to establish myself as a translator of others before I could achieve the illusion of being another myself.

As someone who dislikes looking back at her work, and prefers not to reread it if at all possible, I was not an ideal candidate to translate Dove mi trovo , given that translation is the most intense form of reading and rereading there is. I have never reread one of my books as many times as Dove mi trovo . The experience would have been deadening had it been one of my English books. But working with Italian, even a book that I have myself composed slips surprisingly easily in and out of my hands. This is because the language resides both within me and beyond my grasp. The author who wrote Dove mi trovo both is and is not the author who translated them. This split consciousness is, if nothing else, a bracing experience.

Self-translation led to a deep awareness of the book I’d written, and therefore, to one of my past selves.

For years I have trained myself, when asked to read aloud from my work, to approach it as if it had been written by someone else. Perhaps my impulse to separate radically from my former work, book after book, was already conditioning me to recognize the separate writers who have always dwelled inside me. We write books in a fixed moment in time, in a specific phase of our consciousness and development. That is why reading words written years ago feels alienating. You are no longer the person whose existence depended on the production of those words. But alienation, for better or for worse, establishes distance, and grants perspective, two things that are particularly crucial to the act of self-translation.

Self-translation led to a deep awareness of the book I’d written, and therefore, to one of my past selves. As I’ve said, once I write my other books, I tend to walk away as quickly as possible, whereas I now have a certain residual affection for Dove mi trovo , just as I do for its English counterpart—an affection born from the intimacy that can only be achieved by the collaborative act of translating as opposed to the solitary act of writing.

I also feel, toward Dove mi trovo , a level of acceptance that I have not felt for the other books. The others still haunt me with choices I might have made, ideas I ought to have developed, passages that should have been further revised. In translating Dove mi trovo , in writing it a second time in a second language and allowing it to be born, largely intact, a second time, I feel closer to it, doubly tied to it, whereas the other books represent a series of relationships, passionate and life-altering at the time, that have now cooled to embers, having never strayed beyond the point of no return.

My copy of Dove mi trovo in Italian is a now dog-eared volume, underlined and marked with Post-its indicating the various corrections and clarifications to make. It has transformed from a published text to something resembling a set of bound galleys. I would never have thought to make those changes had I not translated the book out of the language in which I conceived and created it. Only I was capable of accessing and altering both texts from the inside. Now that the book is about to be printed in English, it has traded places with the finished Italian copy, which has lost its published patina, at least from the author’s point of view, and resumed the identity of a work still in its final stages of becoming a published text. As I write this, Whereabouts is being sewn up for publication, but Dove mi trovo needs to be opened up again for a few discreet procedures. That original book, which now feels incomplete to me, stands in line behind its English-language counterpart. Like an image viewed in the mirror, it has turned into the simulacrum, and both is and is not the starting point for what rationally and irrationally followed.

© 2021 by Jhumpa Lahiri. By arrangement with the author. All rights reserved.

Jhumpa Lahiri

Jhumpa Lahiri is a Pulitzer Prize–winning writer and translator.

In Praise of Echo

Literary border-crossings in iran, reclaiming memories: returning to kashmir.

Translating Myself: Adventures in Self-Translation at the Iowa Translation Workshop

Posted on September 14, 2015 in Essays

It was my second time presenting work in the translation workshop. The story was called “The Grey Quarter,” and I’d just written it just a few months before, for my fiction workshop in the Spanish Creative Writing MFA. Now I was presenting it into English. Our workshop professor, Aron Aji, said it was a double opportunity for the story to be workshopped: for once, I was both author and translator.

Aron had assured me months before—when I said I wanted to embark upon a selfish and egotistical enterprise in the translation workshop—that self-translation was a viable element of translation as a whole. There was theory about it and (perhaps more importantly, and reassuringly), it was practiced all the time.

The translation workshop began with questions for the translator/author (me). Aron started by asking the narrator’s age. How old is she when she’s telling the story? It should have been an easy question. I—the author, the “expert”—should have known the answer, but I could only reply I knew she was older than I was but was probably, maybe, I wasn’t sure, younger than thirty?

I hadn’t needed more to write the story in Spanish. A sense of her age and her circumstances in relation to my own, an inkling of where she was, and what had happened to her so my unconscious could transform those notions into a voice in Spanish—that was enough. I never thought I would need to know more to translate the story.

In revising my translation I realized how much of my writing happens unconsciously, thoughtlessly, just notched forward by a certain feelings: I felt she was older than me. This is probably to be expected. I’m still getting to know most of the aspects of my own writing. In this exercise of self-translation I understood that while I’m totally obsessed with planning every detail of the plot, I let my characters come to me as sensations, half-formed people whom I get to know little by little as I write.

The greatest virtue I have as a translator of my own work might also be my biggest downfall. I know the text better than anyone else. I’m so close to it that I know exactly what the author was thinking as she wrote it, why she used certain words, how that street looked, how the night felt, even the way the boys on that other street were smirking. But I will never be able to read one of my stories as a reader could.

I’ll always be too close, too attached. I need to step back to recognize the strengths that appear without the slightest plan, as a whim. While trying to translate myself, sometimes I had to recreate the frame of mind I had while writing, before revising, before repeated workshops deconstructed it. I had to return to those first impulses, and ask myself why I had made this or that decision. How old is she? Why is she telling the story now? How does she feel about what happened?

During the translation workshop, and in my own exercises in self-translation, I realized something else: I don’t know if I’ll ever have the same relationship with English that I have with Spanish. Maybe this should have been obvious from the start, but I had convinced myself that my English was finally good enough, and I had forgotten how sometimes writing feels like a love affair with language. I have gotten to know Spanish with age: its taste in my mouth, its beautiful sounds, its bad sounds, its great words, its horrible words, its quirks, its difficulties, its flexibilities, its strange habits.

But above everything else, I trust Spanish in I way I don’t trust English. Perhaps this is just a matter of familiarity, but during the translation workshop I felt as if I lacked a certain sensitivity that I had no idea how to gain. I have to admit that without an editor—in this case my close-reading peers in the translation workshop—the story would never have ended up as it did.

Self-translation was a great experiment and I wish to continue with it and to continue building my relationship with English. I like having to think about the words I used, the sentences I created, and the reasons behind a story that sometimes are lost in the act of writing it. It was challenging and insightful to recreate the genesis of a story, how it came to be, what the answers to questions I’d never actually asked myself might be. I grew closer to the story and to my own instincts as a writer when I was forced to take a step back and to look at them from afar.

Tagged as: Spanish Creative Writing , Spanish , workshop , Aron Aji , self-translation , fiction

More from Exchanges

- Translators Note: Exchanges Audio

- Briefly Mentioned

- World Literature in the Making

Recommendations for the 30th Anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall

Review: Greek Lessons

Teaching Translation: Rosanna Warren

Tweets from Sri Lanka

Toward a Surprisingly Similar Yet Different Form of Imagination

Related posts, graphic novels in translation, amber brian and the native archive, review: sor juana & other monsters, prizewinning russian minimalism, new mfa director, catcher in the rye in russian.

Privacy Information Nondiscrimination Statement Accessibility UI Indigenous Land Acknowledgement

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- World Languages

How to Describe Yourself in French

Last Updated: September 9, 2022 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Language Academia . Language Academia is a private, online language school founded by Kordilia Foxstone. Kordilia and her team specialize in teaching foreign languages and accent reduction. Language Academia offers courses in several languages, including English, Spanish, and Mandarin. There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 439,017 times.

Describing yourself is an important skill personally and professionally. You may wish to meet or date someone, get to know a friend better, or present yourself in a professional context. The rules for describing yourself in French are similar to how you would do it in English, but there are a few distinctions to be aware of. Using these guidelines you will have a basic structure that you can expand on to provide a more personalized description of yourself.

Describing your Personality

- The French word for first name is “prenom” (prey–nom). You could say “Mon prénom est...” (mon prey-nom ey) which means “my first name is...”

- The French word for surname is “nom de famille” (nohm dhe fah-mee). In a professional or commercial transaction if someone asks for your "nom" be sure to provide your last name rather than your first.

- Consult a dictionary to find pronunciations of specific numbers.

- You can also describe your age group more generally using the phrase “je suis” (zhe swee) followed by an adjective. “Jeune” (zhuhn) means young. “Vieux” (vee-euh) indicates an elderly man, while “vieille” (vee-ay) indicates an elderly woman. “Je suis jeune” means “I am young.”

- You can also say “my hair is...” followed by a color. The phrase for this is “Mes cheveux sont...” (meh chuh-vuh son). Consult a dictionary for the appropriate color.

- The same construction works to describe your eye color. You would say “Mes yeux sont ...” (mehz-yuh son) which means "my eyes are..." Note that in this case you pronounce the s at the end of “mes” because the next word begins with a vowel.

- “Fort” (for) means strong, while “faible” (febl) means weak.

- “Petit” (petee) for men or “petite” (peteet) for women means small or short.

- “Grand” (grahn) for men or “grande” (grahnd) for women means large or tall.

- Content (cohn-tahn) means happy, while triste (treest) means sad. You would say "je suis triste" to convey "I am sad."

- Fatigué (fah-tee-gay) means tired. You would say “je suis fatigué” to convey "I am tired."

Describing Your Activities

- Male occupations that end with “eur” (euhr) often change to “euse” (euhz) for women. For example, a massage therapist would be either a masseur or a masseuse.

- Male occupations that end in “ier” (ee-ay) often add an extra e to become ière (ee-ehr) for women. A farmer would be either a fermier or a fermière.

- Male occupations that end in a consonant may add an extra e to become feminine. For example, a male student is an “étudiant” (ay-tood-eeon) while a female student is an "étudiante" (ay-tood-eeont). Note that the final consonant is pronounced only in the female form.

- Many occupations have only one form, regardless of gender, such as "professeur" which means teacher.

- “I like” is “j’aime” (zhehm). "I love" is “j’adore” (zha-dor). “J’aime lire” (zhehm leer) means “I like to read.”

- The words “ne” and “pas” on either side of the verb negate the phrase, indicating dislike. "I do not like" is “je n’aime pas” (zhe nem pah). “Je n’aime pas chanter” (zhe nem pas chan-tay) means “I do not like to sing.”

- Mon (mohn) or ma (mah) are used as possessives, when you wish to indicate that you like something that belongs to you. Mes (meh) indicates a possessive plural. [5] X Research source

- Mon is used when the noun is masculine, indicated in the dictionary by the letter m. “J’aime mon chat” means "I like my cat." Note that it does not matter if you are male, it matters that cat (chat) is a masculine noun.

- Ma is used when the noun is feminine, indicated in the dictionary by the letter f. “J’aime ma tante” means "I like my aunt." Again, it matters that aunt is a feminine noun, not that you are a man or a woman.

- Mes indicates a possessive plural noun, such as “my aunts” or “my cats.” You would say “j’aime mes tantes” or “j’aime mes chats.” [6] X Research source

- If this is too challenging it may be easier to use the above recommendations for sharing hobbies, simply saying “I like sports” or “j’aime les sports.”

- This construction also works to describe personality traits. For example gentil/gentille (zhantee/zhanteel) means nice. You would say “je suis gentil” if you are a man or "je suis gentille" for a woman.

Printable Phrase Guides

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://omniglot.com/language/phrases/french.php

- ↑ https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zjx947h/articles/z7ftwty

- ↑ https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/frenchcopy/chapter/2-4-the-verb-etre/

- ↑ http://www.languageguide.org/french/grammar/gender/

- ↑ http://www.thefrenchexperiment.com/learn-french/possessive-adjectives.php

- ↑ https://www.lawlessfrench.com/grammar/possessive-adjectives/

- ↑ http://www.languageguide.org/french/grammar/adjectives/

About This Article

To describe yourself in French, start by learning some of the basic French phrases for introducing yourself, like “Je m’appelle” and “Je suis” to tell people your name and something about yourself. For example, “Je suis blonde” tells people that you’re a blonde, while “Je suis fatigué” means “I’m tired!” To talk about your interests, use the word “J’aime” to say that you love or like something! Scroll down to learn how to use the appropriate adjectives for your gender! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Nov 23, 2023

Did this article help you?

Mar 21, 2016

Samuel Adama

Sep 22, 2018

Chern Eunice

Jun 8, 2017

Noyonika Chatterjee

Jul 13, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

Seattle Arts and Lectures

- Subscriptions

- Youth Programs

- Search Icon

- Writers in the Schools

- Youth Poetry Fellowship

- Spotlight Author Visits

- Summer Book Bingo

- Community Access Tickets

- Prowda Award

- The SAL Gala: Words Bloom

- Individual Giving

- Institutional Giving

A Blog of Seattle Arts & Lectures

Myself in Translation: An Essay on Alison Bechdel

November 3, 2015.

By Corinne Manning, WITS Writer-in-Residence

This essay was first published on October 19, 2015 on LitHub , on the occasion of SAL’s program featuring Alison Bechdel in the 2015/16 Literary Arts Series, written by WITS Writer-in-Residence Corinne Manning.

T his is my memory, though it’s technically unconfirmed: my mom had seen this flag that she liked, non denominational, not especially patriotic with stripes of all different colors. On a trip to Tarrytown, New York my mom found an antique store that had a bin of these flags in the back. It was called “An All Seasons Flag” or maybe that was what my mom said it was called. The flag was wrapped in a thick plastic sheath, which my mom discarded once we came home.

“It’s great because we won’t have to keep putting different flags up,” she said as she stuck it into its holder. Maybe she felt like her full self when she looked at the rose bushes outside the house, the trimmed grass, the “All Seasons” flag waving with equal love for every stage of the year. I felt her satisfaction even as she sat on the couch in the living room, reading the paper cover to cover for hours, or just staring out the window, “thinking,” she said, as the flag whipped peacefully in its slot.

“Why does mom have the gay pride flag up?”

This was what my brother asked as we approached the house. He was visiting from art school. In a few years he would come out and tell us that he was a bear, but for now he was just an asexual artist who once made my parents uncomfortable when he gave them a painting of a naked man. This is what I remember.

I found the flag in the trash the next day. When I went up to her room to ask her why I found her lying in bed watching TV. “A wasp got in it,” she said, without taking her eyes away from the screen.

I’ve thought about this moment a lot over the years, but when I think about it now, I picture it in Alison Bechdel’s hand (maximalist detail, minimalist depiction), how Bechdel would capture the fruit basket wallpaper, the pear situated in such a way that it always revealed a clown’s face. Also, the disarray of junk on the desk, even the show my mom was watching. I picture 20/20 , in memory Barbara Walter’s face looms, but it was likely a Sunday, which means it was 60 Minutes . Here again, Bechdel’s attention to detail would keep the scene more factual, more honest.

It took me years to come out—long after my mom and then my brother’s announcement shook the extended family to their born-again breaking point—partially because sexuality is complex, but it’s also possible that I didn’t understand how to construct this narrative. I didn’t know there could be a family where more than half the members were gay. At that time, growing up on the Jersey Shore I hadn’t met any queer women or even seen much representation of one and didn’t realize I could find a place among them.

It’s not that there are stories that are impossible to tell, just complicated—as storytellers we want to capture and express every nuance, to enable the reader, or the person listening to you, to fit something impossible, like the entire state of Washington in their mouth. Not in manageable bites, but the way you had to do it, stretching the skin, the corners of your mouth cracking. But when it is most successful and masterful, as it is in Alison Bechdel’s work, the state—the story—is just suddenly in there, and it’s not just my mouth that’s full, but all of me and it’s a little frightening and beautiful—How did she get all that in there? How did I have room for all of this? How did she?

We can look to Bechdel’s medium for what may be a trite answer: the effect of words and pictures together. But it isn’t just a simple double representation that’s created when Bechdel works, at least not in form, but the way the images and the words often work asymmetrically, allowing for multiple stories, or complex philosophical set ups.

Double representation is actually the phrase I use when I talk about my personal experience of her work. It’s a very nuanced visibility I never expected to see projected: the nature of my family and my own sexuality.

In an early book, The Indelible Alison Bechdel , we can trace the edges of Bechdel’s memoir work—this early process of translation and reflection—as she discusses the development of her comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For . The first of these comics was published in 1983, the year I was born, in the July-August issue of Womanews . Of the genius beginnings of this project, Bechdel demurs:

The quality of the drawing and writing was wildly uneven—more often than not the cartoons weren’t even funny—but lesbians were so desperate to see a reflection of their lives it didn’t seem to matter much.

I’d like to think that my enjoyment of these cartoons is greater than simple desperation or hunger, or need. It is delightful to see elements of my experience that I didn’t think to be experience, that I am used to having be invisible, presented to me, but they are also just really great cartoons. They’re funny, precisely for the reason that makes Bechdel’s work powerful: they are conscious, alive with detail, at once satirical and compassionate. Sudden visibility can be tricky if you are of a group that isn’t used to being depicted—criticism of that depiction is typical. Dykes to Watch Out For wasn’t immune to that, but there is something so gleefully joyful about this particular reflection, where lesbian sexuality or queer female sexuality, or small town politicized gay life (everyone’s a social worker!), gets translated as funny, in a ha ha way rather than funny as pathetic or the butt of a straight guy’s joke.

I’m thinking about the difference between reflection and translation, if one is meant to reveal and the other is meant to express in one language while retaining the original meaning and feel. The relationship between the two words feels closer than the definitions allow, as the result of neither reflection nor translation is exact, there’s always some distortion.

In Fun Home Bechdel presents herself and her father as a kind of translation (“as close as a translation can get”) of each other: their sexuality, their appreciation of masculinity, and also their distortions: her father’s hidden life, Bechdel’s revealed life. What I see when I read her work is the murky translation, or maybe transliteration of my own experience. My mother came out later in life, but previous to her coming out my image of her was marked by what I would later understand as repression: her own rages, the passionate fights and eventual disappearance of many female friends, and her obsession with my own sexuality. Let’s imagine a panel: I’m in the family den, lying on a tweedy couch trying to watch TV when my mom calls from the top of the stairs “Are you sure you don’t like girls?” or “There’s nothing wrong with meeting a nice girl” or, during a shakier time, “Doesn’t it disgust you? The thought of two women or two men together? It repulses me.” When I told her I wasn’t repulsed, she said, “So you’re gay.” My answer during this period was always an annoyed no, even though I did wonder if there was something wrong with me, by not being repulsed.

I understand now that for a time, my mom hoped that she could see a reflection of herself in me. That perhaps I could be gay if she couldn’t. But then she came out, and watching her process, our Jersey Italian family’s response to it, repulsed me in its own way and kept me at the edges of my own queerness for years. And when I finally did come out I denied her any recognition or connection. I didn’t want to see myself reflected in her. First my sexuality wasn’t related to my identity, then I was queer and she was gay. Much like the scene in Fun Home of Bechdel and her father in the car, there was no joyous reunion. We were trapped in the Ulysses of our experience: fatherless Stephen and sonless Bloom.

Which is why Are You My Mother? —Bechdel’s exploration of her relationship with her mother and the nature of psychoanalysis and motherhood, is an important piece to my story too, because both books offer me a more complete vision of myself. At the beginning of Fun Home , as we witness the memory of her father bathing her, Bechdel states that the bar is lower for fathers than mothers. Isn’t the nature of mothers and children or mothers and daughters this resistance to recognize each other (you are of me but you are not me) or as the psychoanalyst, Donald Winnicott, posits in the relation between infant and mother: I forget you, but you remember me? It is a bond that must be broken, but both long for a time when, at one point, there was this other truth that Bechdel shares: “two separate beings to be identical… to be one.”

When my mother texted me after the repeal of DOMA—“Congratulations, honey!”—I didn’t respond, out of a kind of disappointment, out of my political stand on it being the wrong fight, out of the desire to not be her. It’s a sad drawing, me holding the phone. She wanted a different panel, a simpler drawing; a congratulations in return, to stand across from each other waving little All Seasons Flags. In a Bechdel version of this story, both panels exist, one reflecting the other. We’re both full of longing. We’re both disappointed. This is where the story starts to stretch my mouth. Maybe this is as close as a translation can get.

–Corinne Manning

Corinne Manning is the founding editor of The James Franco Review , an online journal dedicated to the visibility of underrepresented artists. Her writing has appeared in The Nervous Breakdown, The Oxford American, Arts & Letters, Southern Humanities Review, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, and as a chapbook through alice blue review’s Shotgun Wedding Series.

Posted in Literary Arts Series

The Study Blog

Term Paper Writing Help

If you aren't sure whether you are good at expressing yourself through writing, then if you find it difficult to do so (e.g., when trying to write an english essay), we can help you overcome those obstacles by assisting you in improving your communication through writing. We help students compose essays or other types of papers for their courses. Now is the time to come visit us!

How to Overcome the Complexity of a Nursing Essay

There aren't many alternatives for professional translations. Before writing a good summary of something, you need to know your subject well enough to be able to write an accurate one. A research paper requires mastery of research language, a deep understanding of their subjects to be able to write about them clearly, and a careful consideration of possible problems before proposing solutions. Students often have trouble understanding medical terminology when they first encounter it, because they have never heard of these words before. When writing a cohesive psychology essay, students must be familiar with some psychological concepts. We have a wealth of experience under our belt, so we know where they need help. Although you may be able to find better deals elsewhere, there is no way to tell if these sites offer superior customer service and top-quality results. Read customer reviews before making any online purchases. If you don't think there's a market for them, it's perhaps best to skip them.

Professional Help from Copywriters

If you would like us to write anything from an essay in history to a term paper for you, we’d be happy to oblige. When writing something, there's a precise formula for choosing the best word. You can rest assured that you'll receive an expertly written paper from those who know exactly what they're doing. No need to write anything down today; there are no reasons why you shouldn't let others edit your document for you. Don't waste your time trying to convince them to do it for you, instead, invest it in something more productive! Order term papers online and go there! Founded in a simple belief that we are capable of delivering top-quality content to you, we offer a range of guarantees. Test it out yourself! The results must be presented after all the research has been completed.

Cheap Business Essay Writing Services

Before being accepted into our company, we underwent extensive background checks. Check their credentials to confirm that they have been writing professionally for some time. If they are members of professional associations, check, for instance.

Fun Tips to Spend Orthodox Easter Away from Home

In "Student Life"

Welcome to the New Bloggers

In "Degree Essentials"

Mastering Warwick as a Postgraduate

In "Looking After You"

Comments are closed.

Copyright, 2023

Finished Papers

Jalan Zamrud Raya Ruko Permata Puri 1 Blok L1 No. 10, Kecamatan Cimanggis, Kota Depok, Jawa Barat 16452

Customer Reviews

Customer Reviews

Look up our reviews and see what our clients have to say! We have thousands of returning clients that use our writing services every chance they get. We value your reputation, anonymity, and trust in us.

Gain efficiency with my essay writer. Hire us to write my essay for me with our best essay writing service!

Enhance your writing skills with the writers of penmypaper and avail the 20% flat discount, using the code ppfest20, team of essay writers, the various domains to be covered for my essay writing..

If you are looking for reliable and dedicated writing service professionals to write for you, who will increase the value of the entire draft, then you are at the right place. The writers of PenMyPaper have got a vast knowledge about various academic domains along with years of work experience in the field of academic writing. Thus, be it any kind of write-up, with multiple requirements to write with, the essay writer for me is sure to go beyond your expectations. Some most explored domains by them are:

- Project management

Who are your essay writers?

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

That Viral Essay Wasn’t About Age Gaps. It Was About Marrying Rich.

But both tactics are flawed if you want to have any hope of becoming yourself..

Women are wisest, a viral essay in New York magazine’s the Cut argues , to maximize their most valuable cultural assets— youth and beauty—and marry older men when they’re still very young. Doing so, 27-year-old writer Grazie Sophia Christie writes, opens up a life of ease, and gets women off of a male-defined timeline that has our professional and reproductive lives crashing irreconcilably into each other. Sure, she says, there are concessions, like one’s freedom and entire independent identity. But those are small gives in comparison to a life in which a person has no adult responsibilities, including the responsibility to become oneself.

This is all framed as rational, perhaps even feminist advice, a way for women to quit playing by men’s rules and to reject exploitative capitalist demands—a choice the writer argues is the most obviously intelligent one. That other Harvard undergraduates did not busy themselves trying to attract wealthy or soon-to-be-wealthy men seems to flummox her (taking her “high breasts, most of my eggs, plausible deniability when it came to purity, a flush ponytail, a pep in my step that had yet to run out” to the Harvard Business School library, “I could not understand why my female classmates did not join me, given their intelligence”). But it’s nothing more than a recycling of some of the oldest advice around: For women to mold themselves around more-powerful men, to never grow into independent adults, and to find happiness in a state of perpetual pre-adolescence, submission, and dependence. These are odd choices for an aspiring writer (one wonders what, exactly, a girl who never wants to grow up and has no idea who she is beyond what a man has made her into could possibly have to write about). And it’s bad advice for most human beings, at least if what most human beings seek are meaningful and happy lives.