Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, historic document, federalist 37 (1788).

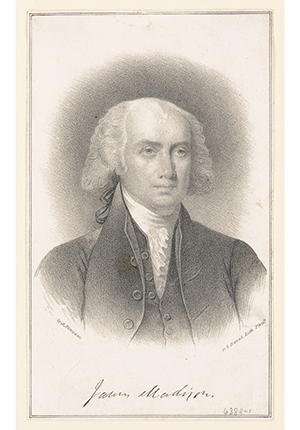

James Madison | 1788

In this installment of The Federalist Papers , James Madison emphasized the enormous challenges that the Constitutional Convention had faced in drafting the Constitution. He did so, in particular, to counter the popular Anti-Federalist criticism that the proposed Constitution had been written in purposely ambiguous language. Madison did not deny that the Constitution featured its share of indeterminacy, but rather explained, through a sophisticated meditation on the relationship between language, constitutionalism, and practice, why this feature was neither avoidable nor a defect. It was not avoidable because human language was incapable of delineating novel, complex objects like those the Framers had sought to outline with absolute precision. But nor was it a defect for whatever remained uncertain or ambiguous in the proposed constitutional system could be worked out in practice.

Selected by

William B. Allen

Emeritus Dean of James Madison College and Emeritus Professor of Political Science at Michigan State University

Jonathan Gienapp

Associate Professor of History at Stanford University

With equal readiness will it be perceived, that besides these inducements to candor, many allowances ought to be made for the difficulties inherent in the very nature of the undertaking referred to the convention. …

Not less arduous must have been the task of marking the proper line of partition between the authority of the general and that of the State governments. Every man will be sensible of this difficulty, in proportion as he has been accustomed to contemplate and discriminate objects extensive and complicated in their nature. The faculties of the mind itself have never yet been distinguished and defined, with satisfactory precision, by all the efforts of the most acute and metaphysical philosophers. Sense, perception, judgment, desire, volition, memory, imagination, are found to be separated by such delicate shades and minute gradations that their boundaries have eluded the most subtle investigations, and remain a pregnant source of ingenious disquisition and controversy. The boundaries between the great kingdom of nature, and, still more, between the various provinces, and lesser portions, into which they are subdivided, afford another illustration of the same important truth. The most sagacious and laborious naturalists have never yet succeeded in tracing with certainty the line which separates the district of vegetable life from the neighboring region of unorganized matter, or which marks the termination of the former and the commencement of the animal empire. A still greater obscurity lies in the distinctive characters by which the objects in each of these great departments of nature have been arranged and assorted.

When we pass from the works of nature, in which all the delineations are perfectly accurate, and appear to be otherwise only from the imperfection of the eye which surveys them, to the institutions of man, in which the obscurity arises as well from the object itself as from the organ by which it is contemplated, we must perceive the necessity of moderating still further our expectations and hopes from the efforts of human sagacity. Experience has instructed us that no skill in the science of government has yet been able to discriminate and define, with sufficient certainty, its three great provinces the legislative, executive, and judiciary; or even the privileges and powers of the different legislative branches. Questions daily occur in the course of practice, which prove the obscurity which reins in these subjects, and which puzzle the greatest adepts in political science.

The experience of ages, with the continued and combined labors of the most enlightened legislatures and jurists, has been equally unsuccessful in delineating the several objects and limits of different codes of laws and different tribunals of justice. The precise extent of the common law, and the statute law, the maritime law, the ecclesiastical law, the law of corporations, and other local laws and customs, remains still to be clearly and finally established in Great Britain, where accuracy in such subjects has been more industriously pursued than in any other part of the world. The jurisdiction of her several courts, general and local, of law, of equity, of admiralty, etc., is not less a source of frequent and intricate discussions, sufficiently denoting the indeterminate limits by which they are respectively circumscribed. All new laws, though penned with the greatest technical skill, and passed on the fullest and most mature deliberation, are considered as more or less obscure and equivocal, until their meaning be liquidated and ascertained by a series of particular discussions and adjudications. Besides the obscurity arising from the complexity of objects, and the imperfection of the human faculties, the medium through which the conceptions of men are conveyed to each other adds a fresh embarrassment. The use of words is to express ideas. Perspicuity, therefore, requires not only that the ideas should be distinctly formed, but that they should be expressed by words distinctly and exclusively appropriate to them. But no language is so copious as to supply words and phrases for every complex idea, or so correct as not to include many equivocally denoting different ideas. Hence it must happen that however accurately objects may be discriminated in themselves, and however accurately the discrimination may be considered, the definition of them may be rendered inaccurate by the inaccuracy of the terms in which it is delivered. And this unavoidable inaccuracy must be greater or less, according to the complexity and novelty of the objects defined. When the Almighty himself condescends to address mankind in their own language, his meaning, luminous as it must be, is rendered dim and doubtful by the cloudy medium through which it is communicated.

Explore the full document

Modal title.

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

- Mission & Strategy

- About Jack Miller

- Board of Directors

- Academic Advisory Council

- National Civics Council

- Now Hiring: Director of Development

- Now Hiring: Teacher Programs Manager for the Midwest

- JMC Reports

- Sign up for our newsletter

- American Political Tradition Project

- Constitution Day

- K-12 Education

- Academic Opportunities

- The American Arc Blog

- For scholars and teachers

- JMC in the News

- Upcoming Events: Spring 2024

- Constitution Day 2023

October 27 marks the publication of Federalist 1 in 1787. Written by Alexander Hamilton under the pseudonym Publius, it was the first of a series of seventy-seven articles appearing in The Independent Journal and The New York Packet. These seventy-seven articles, along with eight additional articles, became The Federalist .

Federalist No. 1 served as an introduction and provided the purpose of the Papers : to ensure the ratification of the new Constitution and, as Publius stated, “the safest course for your liberty, your dignity, and your happiness.” Although he was not shy in promoting his federalist viewpoint, above all, Publius’ arguments were designed to focus on truth and the very real concerns of the average antifederalist.

The subsequent body of work became what Thomas Jefferson deemed “the best commentary on the principles of government, which ever was written.” Long after the ratification of the Constitution, citizens referred to The Federalist as an authority when discerning the true meaning of the Framers and even in contemporary times, scholars return to The Federalist while studying American political theory. Political scientist Clinton Rossiter echoed Jefferson in calling The Federalist “the most important work in political science that has ever been written, or is likely ever to be written in the United States.”

Below is a collection of resources recognizing this enduring piece of American political thought and its meaning, the men behind it, the men against it, and contemporary commentary. Browse these resources or jump from section to section by clicking the links below:

Full text of Federalist No. 1

Relevant resources from the first amendment library.

Selected online resources

Commentary and articles from JMC fellows

Federalist 1 To the People of the State of New York: After an unequivocal experience of the inefficiency of the subsisting federal government, you are called upon to deliberate on a new Constitution for the United States of America. The subject speaks its own importance; comprehending in its consequences nothing less than the existence of the union , the safety and welfare of the parts of which it is composed, the fate of an empire in many respects the most interesting in the world. It has been frequently remarked that it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force. If there be any truth in the remark, the crisis at which we are arrived may with propriety be regarded as the era in which that decision is to be made; and a wrong election of the part we shall act may, in this view, deserve to be considered as the general misfortune of mankind. This idea will add the inducements of philanthropy to those of patriotism, to heighten the solicitude which all considerate and good men must feel for the event. Happy will it be if our choice should be directed by a judicious estimate of our true interests, unperplexed and unbiased by considerations not connected with the public good. But this is a thing more ardently to be wished than seriously to be expected. The plan offered to our deliberations affects too many particular interests, innovates upon too many local institutions, not to involve in its discussion a variety of objects foreign to its merits, and of views, passions and prejudices little favorable to the discovery of truth. Among the most formidable of the obstacles which the new Constitution will have to encounter may readily be distinguished the obvious interest of a certain class of men in every State to resist all changes which may hazard a diminution of the power, emolument, and consequence of the offices they hold under the State establishments; and the perverted ambition of another class of men, who will either hope to aggrandize themselves by the confusions of their country, or will flatter themselves with fairer prospects of elevation from the subdivision of the empire into several partial confederacies than from its union under one government. It is not, however, my design to dwell upon observations of this nature. I am well aware that it would be disingenuous to resolve indiscriminately the opposition of any set of men (merely because their situations might subject them to suspicion) into interested or ambitious views. Candor will oblige us to admit that even such men may be actuated by upright intentions; and it cannot be doubted that much of the opposition which has made its appearance, or may hereafter make its appearance, will spring from sources, blameless at least, if not respectable–the honest errors of minds led astray by preconceived jealousies and fears. So numerous indeed and so powerful are the causes which serve to give a false bias to the judgment, that we, upon many occasions, see wise and good men on the wrong as well as on the right side of questions of the first magnitude to society. This circumstance, if duly attended to, would furnish a lesson of moderation to those who are ever so much persuaded of their being in the right in any controversy. And a further reason for caution, in this respect, might be drawn from the reflection that we are not always sure that those who advocate the truth are influenced by purer principles than their antagonists. Ambition, avarice, personal animosity, party opposition, and many other motives not more laudable than these, are apt to operate as well upon those who support as those who oppose the right side of a question. Were there not even these inducements to moderation, nothing could be more ill-judged than that intolerant spirit which has, at all times, characterized political parties. For in politics, as in religion, it is equally absurd to aim at making proselytes by fire and sword. Heresies in either can rarely be cured by persecution. And yet, however just these sentiments will be allowed to be, we have already sufficient indications that it will happen in this as in all former cases of great national discussion. A torrent of angry and malignant passions will be let loose. To judge from the conduct of the opposite parties, we shall be led to conclude that they will mutually hope to evince the justness of their opinions, and to increase the number of their converts by the loudness of their declamations and the bitterness of their invectives. An enlightened zeal for the energy and efficiency of government will be stigmatized as the offspring of a temper fond of despotic power and hostile to the principles of liberty. An over-scrupulous jealousy of danger to the rights of the people, which is more commonly the fault of the head than of the heart, will be represented as mere pretense and artifice, the stale bait for popularity at the expense of the public good. It will be forgotten, on the one hand, that jealousy is the usual concomitant of love, and that the noble enthusiasm of liberty is apt to be infected with a spirit of narrow and illiberal distrust. On the other hand, it will be equally forgotten that the vigor of government is essential to the security of liberty; that, in the contemplation of a sound and well-informed judgment, their interest can never be separated; and that a dangerous ambition more often lurks behind the specious mask of zeal for the rights of the people than under the forbidden appearance of zeal for the firmness and efficiency of government. History will teach us that the former has been found a much more certain road to the introduction of despotism than the latter, and that of those men who have overturned the liberties of republics, the greatest number have begun their career by paying an obsequious court to the people; commencing demagogues, and ending tyrants. In the course of the preceding observations, I have had an eye, my fellow-citizens, to putting you upon your guard against all attempts, from whatever quarter, to influence your decision in a matter of the utmost moment to your welfare, by any impressions other than those which may result from the evidence of truth. You will, no doubt, at the same time, have collected from the general scope of them, that they proceed from a source not unfriendly to the new Constitution. Yes, my countrymen, I own to you that, after having given it an attentive consideration, I am clearly of opinion it is your interest to adopt it. I am convinced that this is the safest course for your liberty, your dignity, and your happiness. I affect not reserves which I do not feel. I will not amuse you with an appearance of deliberation when I have decided. I frankly acknowledge to you my convictions, and I will freely lay before you the reasons on which they are founded. The consciousness of good intentions disdains ambiguity. I shall not, however, multiply professions on this head. My motives must remain in the depository of my own breast. My arguments will be open to all, and may be judged of by all. They shall at least be offered in a spirit which will not disgrace the cause of truth. I propose, in a series of papers, to discuss the following interesting particulars: The utility of the union to your political prosperity; the insufficiency of the present confederation to preserve that union; the necessity of a government at least equally energetic with the one proposed, to the attainment of this object; the conformity of the proposed constitution to the true principles of republican government; its analogy to your own state constitution; and lastly, the additional security which its adoption will afford to the preservation of that species of government, to liberty, and to property. In the progress of this discussion I shall endeavor to give a satisfactory answer to all the objections which shall have made their appearance, that may seem to have any claim to your attention. It may perhaps be thought superfluous to offer arguments to prove the utility of the union , a point, no doubt, deeply engraved on the hearts of the great body of the people in every State, and one, which it may be imagined, has no adversaries. But the fact is, that we already hear it whispered in the private circles of those who oppose the new Constitution, that the thirteen States are of too great extent for any general system, and that we must of necessity resort to separate confederacies of distinct portions of the whole. This doctrine will, in all probability, be gradually propagated, till it has votaries enough to countenance an open avowal of it. For nothing can be more evident, to those who are able to take an enlarged view of the subject, than the alternative of an adoption of the new Constitution or a dismemberment of the Union. It will therefore be of use to begin by examining the advantages of that Union, the certain evils, and the probable dangers, to which every State will be exposed from its dissolution. This shall accordingly constitute the subject of my next address. Publius From Yale’s Avalon Project

From JMC’s First Amendment Library:

The Federalist

The Federalist is the title given to a series of essays by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay defending the Constitution to New Yorkers in an effort to promote its ratification. The Federalist stands as the most comprehensive and systematic articulation by the Founders of the reasoning behind the design of the United States Constitution. The second to last essay in the Federalist (No. 84) offers a defense of the Constitutional Convention’s unpopular decision to omit a bill of rights, and therefore not to recognize explicitly the freedom of speech or press.

Read more about the Federalist in the First Amendment Library >>

Selected Online Resources

Selected online resources on The Federalist :

Yale’s Avalon Project

Yale Law School’s Avalon Project has created a collection of digital documents relevant to the fields of Law, History, Economics, Politics, Diplomacy and Government. These texts, including The Federalist Papers have been enhanced with links to supporting documents expressly referred to in the body of the text.

Visit Yale’s Avalon Project >>

Carol Highsmith

The Federalist Papers : A Library of Congress Research Guide

The Library of Congress provides several primary documents responding to The Federalist Papers . Included in the collection is a letter from George Washington to Alexander Hamilton predicting that the Papers would be “always interesting to mankind so long as they shall be connected in Civil Society.”

Explore the Library of Congress research guide >>

Federalism Lecture Series with Matthew Post

The Liberty and Learning Fellowship has collaborated with University of Dallas professor Matthew Post to produce a 10-part series on federalism and its philosophical foundations, constitutional basis, history, and current practice.

Click here to view the entire playlist on YouTube >>

The Anti-Federalist Papers

The Gilder Lehrman Institute has gathered together excerpts from some of the most-widely read arguments made against the ratification of the Constitution. Collectively, these writings have come to be known as the Anti-Federalist Papers and contain warnings that the proposed Constitution did not adequately provide against the danger of tyranny.

Read excerpts from the Anti-Federalist Papers at the Gilder Lehrman website >>

* If you are a JMC fellow who’s published on The Federalist or its history and development, and would like your work included here, send it to us at [email protected] .

Commentary and articles from JMC fellows:

William Allen, “ Federal Representation: The Design of the Thirty-fifth Federalist Paper .” ( Publius: The Journal of Federalism 6.3 , Summer 1976)

Sotirios Barber, “ Judicial Review and The Federalist .” ( University of Chicago Law Review 55, 1988)

Matthew Brogdon, “ Federalist Constitutionalism and Judicial Independence .” ( Readings in American Government , 2013)

James Ceaser, “ Fame and the Federalist .” ( The Noblest Minds , Rowman & Littlefield, 1999)

Charles Kesler (editor), The Federalist Papers . (Penguin-Putnam, 1999)

Charles Kesler, “ Responsibility in The Federalist .” ( Educating the Prince: Essays in Honor of Harvey Mansfield , Rowman & Littlefield, 2000)

William Kristol, “ The Problem of the Separation of Powers: Federalist 47-51 .” ( Saving the Revolution: The Federalist Papers and the American Founding , The Free Press, 1987)

Thomas Pangle, “The Federalist Papers’ Vision of Civic Health and the Tradition Out of Which That Vision Emerges.” ( Western Political Quarterly 39.4, 1986)

Colleen Sheehan, “Publius’s Constitution, Now More than Ever.” ( Liberty Law Talks , July 15, 2020)

James Stoner, “ Constitutionalism and Judging in The Federalist .” ( Saving the Revolution: The Federalist Papers and the American Founding , The Free Press, 1987)

James Stoner, “ The New Constitutionalism of Publius .” ( History of American Political Thought , Lexington Books, 2003)

Gregory Weiner, “ After Federalist No. 10 .” ( National Affairs , Fall 2017)

Jean Yarbrough, “ Rethinking The Federalist’s View of Federalism .” ( Publius: The Journal of Federalism 15.1, Winter 1985)

Jean Yarbrough, “ Thoughts on The Federalist’s View of Representation .” ( Polity XII.1, Autumn 1979)

Michael Zuckert, “ The Virtuous Polity, the Accountable Polity: Freedom and Responsibility in The Federalist .” ( Publius 22.1, Winter 1992)

Michael Zuckert, “ Who was Publius? “ ( Enlightening Revolutions: Essays in Honor of Ralph Lerner , Lexington Books, 2006)

The Federalist and Contemporary Commentary/Government

Jeremy Bailey, “ The Traditional View of Hamilton’s Federalist No. 77 and an Unexpected Challenge: A Response to Seth Barrett Tillman .” ( Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy 33.1, 2010)

Sotirios Barber, “ The Federalist and the Anomalies of New Right Constitutionalism .” ( Northern Kentucky Law Review 15, 1988)

Michael Faber, Our Federalist Constitution: The Founders’ Expectations and Contemporary Government . (LFB Scholarly Publishing, 2010)

Michael Zuckert, “ The Federalist at 200—What’s It to Us.” ( Constitutional Commentary 7.1, Winter 1990)

The Men Behind The Federalist

Jeremy Bailey, “ Was James Madison ever for the bill of rights? “ ( Perspectives on Political Science 41.2, 2012)

Clement Fatovic, “ Reason and Experience in Alexander Hamilton’s Science of Politics .” ( American Political Thought: A Journal of Ideas, Institutions, and Culture 2.1, Spring 2013)

Peter Onuf, “ Federalist Republican: Michael Zuckert’s James Madison .” ( American Political Thought 8.2, Spring 2019)

David Siemers, “ Theories about Theory: Theory-Based Claims about Presidential Performance from the Case of James Madison .” ( Presidential Studies Quarterly 38.1, 2008)

George Thomas, The Madisonian Constitution . (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008)

Michael Zuckert, “ James Madison in The Federalist: Elucidating ‘The Particular Structure of this Government .'” ( A Companion to James Madison and James Monroe , Wiley Blackwell, 2013)

The Anti-Federalists

William Allen (co-author), The Essential Antifederalist: Second Edition . (Rowman & Littlefield, 2002)

Michael Faber, “ Democratic Anti-Federalism: Rights, Democracy, and the Minority in the Pennsylvania Ratifying Convention .” ( Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 138.2, 2014)

Michael Faber, “ The Union Paradigm of 1788: Three Anti-Federalists Who Changed Their Minds .” ( American Political Thought 4.4, Fall 2015)

David Siemers, “ The Electoral Dynamics of Ratification: Federalist and Antifederalist Strength and Cohesion, 1787-1803 .” ( The House and the Senate in the 1790s: Petitioning, Lobbying, and Institutional Development , Ohio University Press, 2002)

David Siemers, “ Publius and the Antifederalists: ‘A Satisfactory Answer to all the Objections’? “ ( Cambridge Companion to the Federalist , Cambridge University Press, 2019)

Want to help the Jack Miller Center transform higher education? Donate today.

Jack Miller Center 3 Bala Plaza West, Suite 401 Bala Cynwyd, PA 19004

- Resource Center

©2024 Jack Miller Center.

All rights reserved.

Web Design by Push10 Design

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Federalist Papers

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 22, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays written in the 1780s in support of the proposed U.S. Constitution and the strong federal government it advocated. In October 1787, the first in a series of 85 essays arguing for ratification of the Constitution appeared in the Independent Journal , under the pseudonym “Publius.” Addressed to “The People of the State of New York,” the essays were actually written by the statesmen Alexander Hamilton , James Madison and John Jay . They would be published serially from 1787-88 in several New York newspapers. The first 77 essays, including Madison’s famous Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 , appeared in book form in 1788. Titled The Federalist , it has been hailed as one of the most important political documents in U.S. history.

Articles of Confederation

As the first written constitution of the newly independent United States, the Articles of Confederation nominally granted Congress the power to conduct foreign policy, maintain armed forces and coin money.

But in practice, this centralized government body had little authority over the individual states, including no power to levy taxes or regulate commerce, which hampered the new nation’s ability to pay its outstanding debts from the Revolutionary War .

In May 1787, 55 delegates gathered in Philadelphia to address the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation and the problems that had arisen from this weakened central government.

A New Constitution

The document that emerged from the Constitutional Convention went far beyond amending the Articles, however. Instead, it established an entirely new system, including a robust central government divided into legislative , executive and judicial branches.

As soon as 39 delegates signed the proposed Constitution in September 1787, the document went to the states for ratification, igniting a furious debate between “Federalists,” who favored ratification of the Constitution as written, and “Antifederalists,” who opposed the Constitution and resisted giving stronger powers to the national government.

The Rise of Publius

In New York, opposition to the Constitution was particularly strong, and ratification was seen as particularly important. Immediately after the document was adopted, Antifederalists began publishing articles in the press criticizing it.

They argued that the document gave Congress excessive powers and that it could lead to the American people losing the hard-won liberties they had fought for and won in the Revolution.

In response to such critiques, the New York lawyer and statesman Alexander Hamilton, who had served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, decided to write a comprehensive series of essays defending the Constitution, and promoting its ratification.

Who Wrote the Federalist Papers?

As a collaborator, Hamilton recruited his fellow New Yorker John Jay, who had helped negotiate the treaty ending the war with Britain and served as secretary of foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation. The two later enlisted the help of James Madison, another delegate to the Constitutional Convention who was in New York at the time serving in the Confederation Congress.

To avoid opening himself and Madison to charges of betraying the Convention’s confidentiality, Hamilton chose the pen name “Publius,” after a general who had helped found the Roman Republic. He wrote the first essay, which appeared in the Independent Journal, on October 27, 1787.

In it, Hamilton argued that the debate facing the nation was not only over ratification of the proposed Constitution, but over the question of “whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”

After writing the next four essays on the failures of the Articles of Confederation in the realm of foreign affairs, Jay had to drop out of the project due to an attack of rheumatism; he would write only one more essay in the series. Madison wrote a total of 29 essays, while Hamilton wrote a staggering 51.

Federalist Papers Summary

In the Federalist Papers, Hamilton, Jay and Madison argued that the decentralization of power that existed under the Articles of Confederation prevented the new nation from becoming strong enough to compete on the world stage or to quell internal insurrections such as Shays’s Rebellion .

In addition to laying out the many ways in which they believed the Articles of Confederation didn’t work, Hamilton, Jay and Madison used the Federalist essays to explain key provisions of the proposed Constitution, as well as the nature of the republican form of government.

'Federalist 10'

In Federalist 10 , which became the most influential of all the essays, Madison argued against the French political philosopher Montesquieu ’s assertion that true democracy—including Montesquieu’s concept of the separation of powers—was feasible only for small states.

A larger republic, Madison suggested, could more easily balance the competing interests of the different factions or groups (or political parties ) within it. “Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests,” he wrote. “[Y]ou make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens[.]”

After emphasizing the central government’s weakness in law enforcement under the Articles of Confederation in Federalist 21-22 , Hamilton dove into a comprehensive defense of the proposed Constitution in the next 14 essays, devoting seven of them to the importance of the government’s power of taxation.

Madison followed with 20 essays devoted to the structure of the new government, including the need for checks and balances between the different powers.

'Federalist 51'

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” Madison wrote memorably in Federalist 51 . “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

After Jay contributed one more essay on the powers of the Senate , Hamilton concluded the Federalist essays with 21 installments exploring the powers held by the three branches of government—legislative, executive and judiciary.

Impact of the Federalist Papers

Despite their outsized influence in the years to come, and their importance today as touchstones for understanding the Constitution and the founding principles of the U.S. government, the essays published as The Federalist in 1788 saw limited circulation outside of New York at the time they were written. They also fell short of convincing many New York voters, who sent far more Antifederalists than Federalists to the state ratification convention.

Still, in July 1788, a slim majority of New York delegates voted in favor of the Constitution, on the condition that amendments would be added securing certain additional rights. Though Hamilton had opposed this (writing in Federalist 84 that such a bill was unnecessary and could even be harmful) Madison himself would draft the Bill of Rights in 1789, while serving as a representative in the nation’s first Congress.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Ron Chernow, Hamilton (Penguin, 2004). Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (Simon & Schuster, 2010). “If Men Were Angels: Teaching the Constitution with the Federalist Papers.” Constitutional Rights Foundation . Dan T. Coenen, “Fifteen Curious Facts About the Federalist Papers.” University of Georgia School of Law , April 1, 2007.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Teacher Opportunities

- AP U.S. Government Key Terms

- Bureaucracy & Regulation

- Campaigns & Elections

- Civil Rights & Civil Liberties

- Comparative Government

- Constitutional Foundation

- Criminal Law & Justice

- Economics & Financial Literacy

- English & Literature

- Environmental Policy & Land Use

- Executive Branch

- Federalism and State Issues

- Foreign Policy

- Gun Rights & Firearm Legislation

- Immigration

- Interest Groups & Lobbying

- Judicial Branch

- Legislative Branch

- Political Parties

- Science & Technology

- Social Services

- State History

- Supreme Court Cases

- U.S. History

- World History

Log-in to bookmark & organize content - it's free!

- Bell Ringers

- Lesson Plans

- Featured Resources

Lesson Plan: The Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers

Boston College professor Mary Sarah Bilder gives a brief overview backgrounding the Federalist Papers

Description

An introductory overview of The Federalist Papers and their impetus, authorship, and enduring significance

Introductory Discussion Question/Writing Prompt:

Knowing that the Framers were fearful of the potential tyranny of governmental power and most early Americans felt far stronger senses of state identity than national identity, list three aspects of the Constitution that you think would have caused trepidation when it was first proposed in the United States and explain why they may have been of concern.

VIDEO CLIPS:

Video Clip 1: Background of The Federalist Papers (1:46)

Video Clip 2: A Look at Some Actual Federalist Papers (2:58)

- Video Clip 3: Who is Publius? (2:12)

Discussion Questions/Writing Prompts:

Both Amy Pickard and Mary Sara Bilder discussed the fact that the Federalist Papers have been revisited over and over through the centuries and used to help ascertain the rationale for various elements of the Constitution. Why is it important or potentially necessary to continue to attempt to determine what the Constitution meant and guaranteed in the eyes of the Founding Fathers?

Why might Thomas Jefferson have claimed to Dugald Stewart that “the greater parts of papers in this collection were written by Mr. Madison”? Why might he not have wanted that claim written down?

Revisit the list of three “Constitutional Concerns” that you surmised early Americans might have had. Look at the list of Federalist Papers and see whether or not those concerns became the subject of any of them! If your concerns do not appear on that list, do you think it was an oversight on the part of Publius? Why or why not? If they do appear, which Federalist Papers most directly relate to them? Identify two of the most prominently featured topics among the 85 Federalist Papers.

What are some concerns that Americans today have about the federal government? From the master list of concerns identified by yourself and your classmates, choose one that you personally don’t feel is warranted. Write your own Modern Federalist Paper refuting that concern. Then read your classmates’ Federalist Papers, find one with which you disagree, and write an Anti-Federalist paper in response.

- How do you suppose historians went about determining authorship of each of the Federalist Papers? Does it matter which Framer wrote which ones? Why or why not?

Extension Activity Options:

Federalist ePapers: If the equivalent of the Federalist Papers were going to be published today with the intent of reaching the widest possible audience, they might take the form of essays in the newspaper, but more likely would probably appear somewhere on the Internet. Working in a group of three friends as “New Millenium Publius,” determine the forum you would use to spread your message and create a defense of some aspect of the Constitution appropriate to that forum (modeling your content on one of the original Federalist papers )

Federalist Slam Poetry: Take one of the original Federalist papers and reimagine it as a spoken-word document intended to be read aloud. Excerpt about a minute of it to perform for the class.

Authorship Analysis: Have all students type a paragraph (without restrictions on font choice, margins, spacing, etc.) on a common topic with room for individual variation (such as “Choose a school policy to which some students object but with which you agree and explain why you support the policy.” or “Choose one of the literary or historical works from our school’s required reading list. Explain why you think it’s appropriate to require all students to read that work.”) Students should put their names on the back of their paragraphs rather than on the front. Choose three and place students in small groups to attempt to determine the authorship of each one (provide them with the names of all three authors). Once all groups have made their determination, compare the results, ascertain how many were able to make accurate identifications, and discuss the process each group utilized to reach their conclusions.

Federalist 10 Translation

C-SPAN Bell-Ringer: The Federalist Papers

C-SPAN Bell-Ringer: The Federalist Papers and Constitutional Principles

- C-SPAN Q&A With Professor Robert Scigliano , discussing the new edition of The Federalist , published by Modern Library, which he edited with an introduction.

Additional Resources

- WEBSITE: Federalist Papers: Primary Documents of American History (Virtual Programs & Services, Library of Congress)

- WEBSITE: Introductory Note: The Federalist, [27 October 1787–28 May 1788]

- WEBSITE: Our Documents - Federalist Papers, No. 10 & No. 51 (1787-1788)

- WEBSITE: The Federalist Papers - Congress.gov Resources -

- VIDEO CLIP: Federalist Papers, Sep 14 2010 | Video | C-SPAN.org

- Lesson Plan: Federalist 78

- Lesson Plan: Federalist 51

- Lesson Plan: Federalist 10

- Alexander Hamilton

- Constitution

- Federalist Papers

- James Madison

- Ratification

- Thomas Jefferson

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The Federalist Papers

Item preview.

There Is No Preview Available For This Item

This item does not appear to have any files that can be experienced on Archive.org. Please download files in this item to interact with them on your computer. Show all files

Share or Embed This Item

Flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

3,797 Views

8 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

In collections.

Uploaded by Unknown on March 30, 2016

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Federalist Papers: About

Watch Videos

Learn More Online

Federalist Papers (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Federalist Papers (Constitutional Rights Foundation)

The Federalist Papers (History Channel)

Federalist Papers (Constitution Facts)

Federalist Papers Summarized (Tea Party)

Most Cited Federalist Papers (University of Minnesota Law School)

Federalist Papers Famous Quotes (A to Z Quotes)

About the Authors of the Federalist Papers (Library of Congress)

The Federalist Papers (Yale Law School - Avalon Project)

Federalist Papers Authored by Alexander Hamilton (Founding Fathers)

Federalist Papers Authored by John Jay (Founding Fathers)

Federalist Papers Authored by James Madison (Founding Fathers)

Why are the Federalist Papers Important?

The Federalist, commonly referred to as the Federalist Papers, is a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788. The essays were published anonymously, under the pen name "Publius," in various New York state newspapers of the time.

The Federalist Papers were written and published to urge New Yorkers to ratify the proposed United States Constitution, which was drafted in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787. In lobbying for adoption of the Constitution over the existing Articles of Confederation, the essays explain particular provisions of the Constitution in detail. For this reason, and because Hamilton and Madison were each members of the Constitutional Convention, the Federalist Papers are often used today to help interpret the intentions of those drafting the Constitution.

The Federalist Papers were published primarily in two New York state newspapers: The New York Packet and The Independent Journal. They were reprinted in other newspapers in New York state and in several cities in other states. A bound edition, with revisions and corrections by Hamilton, was published in 1788 by printers J. and A. McLean. An edition published by printer Jacob Gideon in 1818, with revisions and corrections by Madison, was the first to identify each essay by its author's name. Because of its publishing history, the assignment of authorship, numbering, and exact wording may vary with different editions of The Federalist. Continue reading from Library of Congress

Federalist Paper Number One by Alexander Hamilton (1787)

After an unequivocal experience of the inefficiency of the subsisting federal government, you are called upon to deliberate on a new Constitution for the United States of America. The subject speaks its own importance; comprehending in its consequences nothing less than the existence of the UNION, the safety and welfare of the parts of which it is composed, the fate of an empire in many respects the most interesting in the world. It has been frequently remarked that it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force. If there be any truth in the remark, the crisis at which we are arrived may with propriety be regarded as the era in which that decision is to be made; and a wrong election of the part we shall act may, in this view, deserve to be considered as the general misfortune of mankind.

This idea will add the inducements of philanthropy to those of patriotism, to heighten the solicitude which all considerate and good men must feel for the event. Happy will it be if our choice should be directed by a judicious estimate of our true interests, unperplexed and unbiased by considerations not connected with the public good. But this is a thing more ardently to be wished than seriously to be expected. The plan offered to our deliberations affects too many particular interests, innovates upon too many local institutions, not to involve in its discussion a variety of objects foreign to its merits, and of views, passions and prejudices little favorable to the discovery of truth. Continue reading from Library of Congress

The Anti-Federalist Papers

Unlike the Federalist, the 85 articles written in opposition to the ratification of the 1787 United States Constitution were not a part of an organized program. Rather, the essays–– written under many pseudonyms and often published first in states other than New York — represented diverse elements of the opposition and focused on a variety of objections to the new Constitution. In New York, a letter written by “Cato” appeared in the New-York Journal within days of submission of the new constitution to the states, led to the Federalists publishing the “Publius” letters. “Cato”, thought to have been New York Governor George Clinton, wrote a further six letters. The sixteen “Brutus” letters, addressed to the Citizens of the State of New York and published in the New-York Journal and the Weekly Register, closely paralleled the “Publius” newspaper articles. Continue reading from Historical Society of the New York Courts

Check Out a Book from Our Collection...

- Last Updated: Mar 27, 2024 4:16 PM

- URL: https://westportlibrary.libguides.com/FederalistPapers2

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Full Text of The Federalist Papers - Federalist ... - Library of Congress

The Federalist, commonly referred to as the Federalist Papers, is a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788.The essays were published anonymously, under the pen name "Publius," in various New York state newspapers of the time. The Federalist Papers were written and published to urge New Yorkers to ratify the proposed ...

The Federalist Papers were a series of essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the pen name "Publius." This guide compiles Library of Congress digital materials, external websites, and a print bibliography.

Federalist Papers. "Written in favour of the New Constitution" (in 1787 and 1788), the Federalist Papers explores how the American government might operate. U.S. Constitution, Federalist Papers, Bill of Rights, and 1774-1875 documents and debates.

The Federalist. The Federalist (1788), a book-form publication of 77 of the 85 Federalist essays. Federalist papers, series of 85 essays on the proposed new Constitution of the United States and on the nature of republican government, published between 1787 and 1788 by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay in an effort to persuade New ...

James Madison Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Share. Summary In this installment of The Federalist Papers, James Madison emphasized the enormous challenges that the Constitutional Convention had faced in drafting the Constitution. He did so, in particular, to counter the popular Anti-Federalist criticism that the proposed ...

The Federalist Papers: A Library of Congress Research Guide. The Library of Congress provides several primary documents responding to The Federalist Papers.Included in the collection is a letter from George Washington to Alexander Hamilton predicting that the Papers would be "always interesting to mankind so long as they shall be connected in Civil Society."

The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays written in the 1780s in support of the proposed U.S. Constitution and the strong federal government it advocated. In October 1787, the first in a ...

WEBSITE: Federalist Papers: Primary Documents of American History (Virtual Programs & Services, Library of Congress) WEBSITE: Introductory Note: The Federalist, [27 October 1787-28 May 1788]

The papers of army officer and first U.S. president George Washington (1732-1799) held in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress constitute the largest collection of original Washington papers in the world. They consist of approximately 77,000 items accumulated by Washington between 1745 and 1799, including correspondence, diaries, and financial and military records.

Book from Project Gutenberg: The Federalist Papers. Library of Congress Classification: JK. Note: Essays written 1787-88. Addeddate.

The Federalist Papers; Documents from the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention, 1774-1789; Guide to American Historical Documents Online; Charters of Freedom from the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

Friday, February 8, 1788. MADISON. To the People of the State of New York: FROM the more general inquiries pursued in the four last papers, I pass on to a more particular examination of the several parts of the government. I shall begin with the House of Representatives. The first view to be taken of this part of the government relates to the ...

The Federalist Papers were a series of essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the pen name "Publius." ... is one of 23 presidents whose papers are held in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. The Madison Papers consist of approximately 12,000 items. Selected references to the Federalist Papers ...

United States president, vice president, secretary of state, and senator from New York. Correspondence, drafts of writings, speeches, and messages to Congress, autobiographical material, notes, certificate, legal record book, estate record book, and other papers pertaining to slavery and the antislavery movement, banking and the Second Bank of the United States, party politics in New York ...

The Federalist, commonly referred to as the Federalist Papers, is a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788. The essays were published anonymously, under the pen name "Publius," in various New York state newspapers of the time. The Federalist Papers were written and ...

For example, Madison refused to concur officially in President George Washington's condemnation of [c]ertain self-created societies—political clubs supporting the French Revolution—and he successfully deflected Federalist interest in censuring such societies. I. Brant, James Madison: Father of the Constitution 1787-1800, at 416-20 (1950).

Footnotes Jump to essay-1 2 The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, at 429 (Max Farrand ed., 1911). Jump to essay-2 The Federalist No. 78 (Alexander Hamil to n). Jump to essay-3 U.S. Const. art. III, § 1. Jump to essay-4 See, e.g., United States ex rel. To th v. Quarles, 350 U.S. 11, 16 (1955) (explaining that Article III courts are presided over by judges appointed for life, subject ...

Learn More. The Federalist Papers were originally published as letters in New York newspapers 1787-1788. Use the Research Guide, Federalist Essays in Historic Newspapers to identify holdings of these newspapers in the Library's Newspaper & Current Periodicals Reading Room. See Elliot's Debates in the collection A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and ...