- All Solutions

- Audience measurement

- Media planning

- Marketing optimization

- Content metadata

- Nielsen One

- All Insights

- Case Studies

- Perspectives

- Data Center

- The Gauge TM – U.S.

- Top 10 – U.S.

- Top Trends – Denmark

- Top Trends – Germany

- Women’s World Cup

- Men’s World Cup

- News Center

Client Login

Insights > Sports & gaming

On different playing fields: the case for gender equity in sports, 6 minute read | stacie de armas, svp, diverse insights & initiatives | march 2021.

Women make up more than half of the U.S. population, but they are still fighting for equality in the world of sports, where gender-based discrimination is all too common. Recently, we saw a very public and painful example, during Women’s History Month no less, of the stark inequity in the treatment of female versus male athletes in the NCAA Basketball Tournament. It’s difficult to understand how neglecting to supply female student-athletes with the proper equipment and facilities—especially during the largest tournament of their sport—can still happen today. Unfortunately, it seems that sexism in sports is ingrained from the time our children are in youth sports. This inequity is also institutionalized—from how we define what qualifies as a sport to the imagery used to represent female athletes, disparities in the facilities, and support for female athletes.

As superstar athlete and World Cup champion Megan Rapinoe testified to Congress, “One cannot simply outperform inequality or be excellent enough to escape discrimination of any kind.” As a mother of a son and a daughter, this inequality hit very close to home just last week. Up until two weeks ago, in my state of California, all youth sports, which were prohibited for nearly a year, were permitted to return. All sports, that is, except for one female-dominated sport: cheer. While my son was able to get back on the field and enjoy his sport, I, alongside many other concerned parents, had to continue to advocate at the state level for equity for cheer athletes. We were successful, but why did we even have to fight for recognition and equal treatment for these athletes? Women and girls in sports should not be an afterthought.

It is disheartening to see that the fight for equality for women’s sports continues beyond grade school, as collegiate athletes in the NCAA Women’s Basketball Tournament recently experienced firsthand. Like many of you, I recently saw the viral video from University of Oregon sophomore forward Sedona Prince showing the weight room facilities provided for the female players at the basketball tournament compared with the facilities provided for the men. The women’s weight room consisted of a single set of dumbbells and some yoga mats, while the men’s weight room was stocked with state-of-the-art training equipment, rows of weights, and workout machines. Her TikTok video was further socialized on Instagram and Twitter and now has more than 20 million views.

The outrage was swift, as many people were quick to criticize the blatant inequities for these female athletes, but the brands stepped in even faster. Not only did the outcry to correct the situation come from celebrities, sports journalists, and fans, but companies weighed in, too. Fitness and retail brands like Orange Theory, Dick’s Sporting Goods and Tonal responded to support these women athletes (who don powerful social media influence) with equipment the very next day and offered to make appropriate training facilities available. Shortly thereafter, the NCAA acknowledged this terrible error in judgment and installed a fully functional women’s weight room coupled with an apology.

These brands understand the power of the moment and of female athletes. Research from Nielsen Sports illustrates the power female athletes hold as social media endorsers. Fans like to buy products and services that their favorite athletes endorse on social media. When brands partner with athletes to embrace their power and advocate for equity, they can enact change as well as accountability in sports institutions. That’s a winning play for brands—fully embracing the power of female athletes, while proactively building equity in women’s sports and not just in response to a crisis.

There are several fundamental truths here that brands need to embrace: social media is powerful; female athletes are powerful influencers; and consumers are asking more from brands when it comes to social responsibility. For example, a global Nielsen Fan Insights study reveals that 47.5% of respondents have a greater interest in brands that have been socially responsible and “do good.” The good news is that some brands are taking notice and recalibrating business and marketing models to meet consumers’ changing needs in a new era of sports sponsorship . The brands stepping in to act on the values they espouse as an organization are a perfect example. Brands, including leagues, teams, owners, and even school districts, must address changing consumer and social demands and their female athletes’ needs by operating with equity in women’s sports.

More opportunity leads to more audience

The weight room in San Antonio isn’t the only place where we need to see change. While we’re seeing progress in how women are represented on television in scripted content, we have not seen the same visibility in women’s sports. This isn’t for lack of women’s sporting events or even viewer interest, but rather the relative lack of access to women’s team sporting events being broadcast and promoted on TV compared with men’s events. We know this needs to change, but it is a catch 22. Far fewer women’s sports are being broadcast, and when they are, games are often carried on difficult to find, smaller outlets, and are under-promoted, naturally resulting in smaller audiences. This overall lack of investment and promotion on television negatively affects audience draw, and therefore ROI for advertisers and sponsors. This lower brand investment is being used to justify disparities in resources for women’s sports. And the cycle continues.

The good news is that there seems to be a change in tide. Coverage for the NCAA Women’s Basketball Tournament this year is one of the broadest in its history thanks to ESPN’s expanding coverage—a move that has so far doubled the audience reach of the first round of the women’s tournament compared with the one in 2019.

Along with the gripping game play, the increase in reach is most likely attributed to the number of games actually being aired. Round 1 of the tournament in 2019 was exclusively broadcast on ESPN2, which aired just nine game windows. This year’s NCAA women’s games have been on ABC, ESPN, ESPN2 and ESPNU, and every single one of the 32 games has been aired in round 1. When audiences have access to women’s sports, they tune in. Female athletes deserve the facilities, equipment and support they need to thrive. While the men’s tournament has seen multi-network coverage since 2011, the women’s tournament is finally seeing increased coverage, with 2021 marking the first time the women’s tournament has been on network TV—and not just on cable—in decades. Because that viewing opportunity exists, more people are watching. It is time women’s sports get the investment, coverage and support they deserve. Advertisers should take note: A growing fan base means a bigger audience.

It has been nearly 50 years since Title IX legislation granted women equal opportunities to play sports. But the legislation also mandates the equal treatment of female and male student-athletes from equipment to competitive facilities to publicity and promotions and more. As more and more brands champion equity for women’s sports and female athletes become more influential as brand endorsers, it is my hope that we will see fewer disparities in playing time, facilities, brand partnerships, and coverage of women’s sports on screen. And that for future female athletes, equity for women’s sports will be a slam dunk.

Related tags:

Related insights

Continue browsing similar insights.

Evolving the measurement of sports events

Nielsen worked with World Athletics on new measurements of success for hosting major sports events.

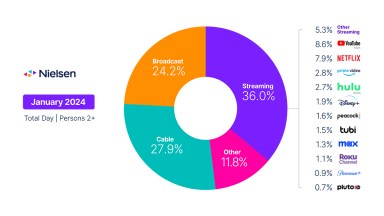

Colder weather and NFL playoffs drive increased TV usage in January

Chilly weather, coupled with the excitement of the NFL playoffs, helped boost total TV viewership 3.7% in January.

Black audiences are looking for relevant representation in advertising and content

Dimensions of diversity are numerous, spanning well beyond skin tone and narrative location.

Find the right solution for your business

In an ever-changing world, we’re here to help you stay ahead of what’s to come with the tools to measure, connect with, and engage your audiences.

How can we help?

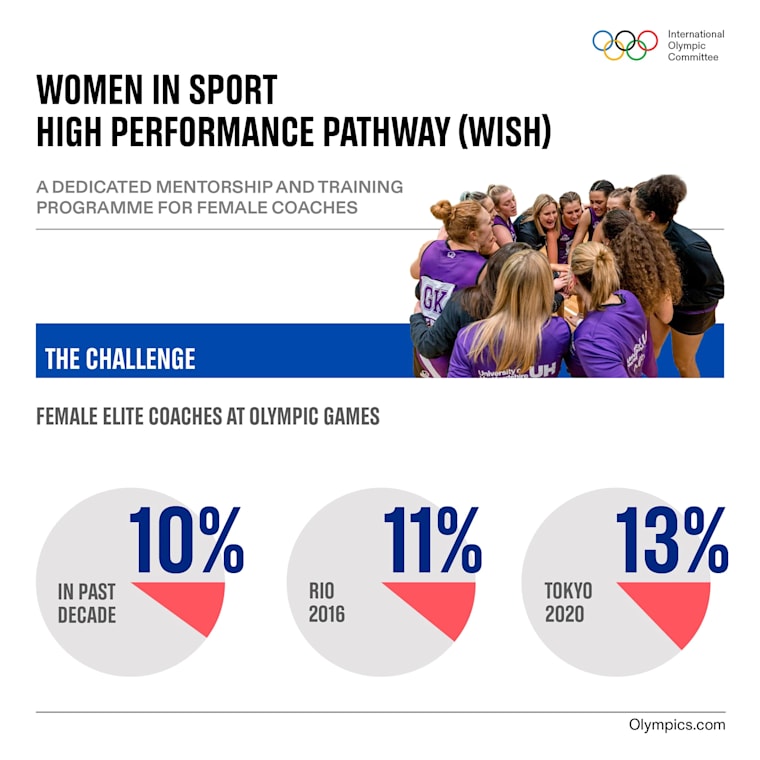

Women in sport are changing the game

Date: Thursday, 22 July 2021

As the Tokyo 2020 Olympics kick-off on 23 July 2021, almost 49 per cent of participating athletes will be women, making it the most gender-balanced Games in history. All 206 National Olympic Committees also have at least one female and one male athlete representative. This marks a landmark for gender balance in sport – a powerful means of empowering women and girls .

Sport mobilizes the global community and speaks to youth. It unites across national barriers and cultural differences. It teaches women and girls the values of teamwork, self-reliance and resilience; has a multiplier effect on their health, education and leadership development; contributes to self-esteem; builds social connections; and challenges harmful gender norms.

To celebrate women in sport, here are just a few inspirational women breaking down gender barriers all around the world.

Malak Abdelshafi, a Paralympic swimming champion from Egypt

Malak Abdelshafi is a 17-year-old Egyptian Paralympic swimming champion who qualified for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. When she was 10 months old, she suffered severe spinal cord injuries from an accident that left her partially paralysed.

“I started swimming as hydrotherapy, since wheelchair-users usually need to maintain blood circulation,” says Abdelshafi . “I did not plan to swim professionally. During my hydrotherapy sessions, my trainer said I was talented and pushed me to compete.”

“My first championship was in 2012 with my club and I won a silver medal. I was 9 years old then and the youngest among the participants. We were all surprised and did not expect it at all. Since then, I decided to pursue a professional track in swimming. I joined the national team in 2014.” Abdelshafi has since won 39 national and six international medals.

“Nothing can stop us because we’re girls. We’re all human and there’s no difference between a girl or a boy. One of my favourite quotes is: ‘There’s always another way’. When you find out that the way to your goal is blocked, don’t give up. Try to find another way and you’ll reach your goal with your persistence.”

“I believe that sports can influence our behaviour and help us have a positive impact on others. I hope I can do this one day and be an inspirational model.”

Kathely Rosa, an aspiring soccer coach from Brazil

When Kathely Rosa,19, first shared her dream of becoming a professional football player, people around her said football was for boys. When she tried to play with the boys, they refused and would only allow her to watch. Her brother, four years younger, had a completely different experience, and took football lessons from an early age.

“He had a ball, a complete uniform, the opportunity to train at a club, money to participate in championships and selection processes. I got nothing,” says Rosa .

Rosa decided to coach herself, watching videos online to learn the tactics and practiced alone. One day, she was searching various ways of dribbling and found a video showing Brazilian football player and UN Women Goodwill Ambassador Marta Vieira da Silva scoring a goal 20 different ways.

“I learned football mainly from male figures, because women’s football is not that visible,” says Rosa. “I was just fascinated when I saw what Marta could do with a ball.”

In February 2020, Rosa, along with 15 girls from One Win Leads to Another (OWLA), a joint programme with UN Women and the International Olympic Committee that provides weekly sport practice and life skills sessions for adolescent girls, fulfilled another dream – she met Marta in person in Rio.

“Marta told me that if I truly believe in what I want to do, nothing is impossible,” says Rosa. “It may sound like an obvious advice, but I needed to hear that from her.”

“I will graduate, become a coach and create a female’s football team with girls from the favela . There are a lot of girls with so much talent. They just need to be properly trained,” says Rosa. In the meantime, Rosa continues to lead by example in her community, as the only girl who plays on the boys’ team.

Anita Karim, Pakistan’s first professional mixed martial arts fighter

Anita Karim, 24, is the only woman among the more than 300 professional mixed martial arts (MMA) fighters in Pakistan.

“I understand how significant confidence and knowledge of self-defence are for girls,” says Karim . “I started training in mixed martial arts and I wanted to become an example for other girls to encourage them to join a sport like MMA that makes individuals healthy and active.”

Karim comes from a family of MMA fighters and trains at an MMA training centre founded by her brothers in Islamabad. Her first professional fight was in 2018. “My family always supported me and encouraged my enthusiasm towards MMA, which is why I have accomplished so.” says Karim.

“We get the message from our society that women and girls can't commute on their own or can only work in particular areas. We are taught to fear, and there is a perception that girls are weak and vulnerable, which makes it difficult for us to move forward. When we go out and encounter harassment, we get frightened and are unable to react. MMA has taught me confidence and also made me strong enough to compete at a global level. It has taught me strategies for protecting myself in any kind of difficult situation.”

Khadija Timera, a lawyer and boxer from Senegal

Khadija Timera, 35, was raised in a working-class district in Paris. She won a scholarship to study business law at the University of California, Berkeley, and has worked in one of the world’s top law firms.

“After graduating, I felt that I had achieved a challenge,” says Timera . “I wanted to create my own company to support high-level sportswomen, specifically soccer players.” Now, Timera runs a London-based business and investments consultancy for professional athletes and is also a boxer, who advocates against gender-based violence. She narrowly missed out on qualifying for the Tokyo Olympics.

“I made my first selection in 2019. We went to the African championship in Cabo Verde and I won the gold medal for Senegal,” says Timera.

“Violence against women is regrettable. Women and children in Senegal are vulnerable and should therefore be protected.”

“People need to become [more] aware that women and men are equal and complementary. I also think that women themselves have to realize that they have a real power that they send out; they have to learn to trust themselves.”

“Boxing can help to build confidence,” Timera adds. “There should be many more associations and action to help women recognize their personal value and learn self-development.”

To women, Timera says: “you are enough.”

Aizhan Alymbai Kyzy, a chess champion from Kyrgyzstan

Aizhan Alymbai Kyzy is a 26-year-old chess champion from Kyrgyzstan. She has been a member of the national team since she was 15 years old, and came third place in the Asian Rapid Chess Championship.

“In Kyrgyzstan, as in the rest of the world, chess is mostly male dominated,” says Kyzy . “Monetary awards for women at the Kyrgyz championships are almost half of what men are offered and mostly men participate in these tournaments. The situation is changing for the better now.”

Kyzy believes the world is heading towards equality and that families have a significant role to play in supporting their daughters.

“We can be the ones to push the boundaries of what is possible,” says Kyzy. “At chess academy, where I was teaching, we demanded equal performance both from girls and boys. But parents urged teachers to be less harsh on girls. We need to raise awareness on ensuring quality education for girls and encourage families to support their daughters.”

“In the modern world, creative thinking and analytics are highly valued, and this is exactly what chess can offer. I want to be a role model for other girls. Playing chess is empowering, self-fulfilling, and makes you realize that everything is possible. Our society needs to create an enabling environment for women’s empowerment in sports and beyond. I call on all women and girls to challenge gender stereotypes, smash the boundaries and keep realizing their dreams!”

- ‘One Woman’ – The UN Women song

- UN Under-Secretary-General and UN Women Executive Director Sima Bahous

- Kirsi Madi, Deputy Executive Director for Resource Management, Sustainability and Partnerships

- Nyaradzayi Gumbonzvanda, Deputy Executive Director for Normative Support, UN System Coordination and Programme Results

- Guiding documents

- Report wrongdoing

- Programme implementation

- Career opportunities

- Application and recruitment process

- Meet our people

- Internship programme

- Procurement principles

- Gender-responsive procurement

- Doing business with UN Women

- How to become a UN Women vendor

- Contract templates and general conditions of contract

- Vendor protest procedure

- Facts and Figures

- Global norms and standards

- Women’s movements

- Parliaments and local governance

- Constitutions and legal reform

- Preguntas frecuentes

- Global Norms and Standards

- Macroeconomic policies and social protection

- Sustainable Development and Climate Change

- Rural women

- Employment and migration

- Facts and figures

- Creating safe public spaces

- Spotlight Initiative

- Essential services

- Focusing on prevention

- Research and data

- Other areas of work

- UNiTE campaign

- Conflict prevention and resolution

- Building and sustaining peace

- Young women in peace and security

- Rule of law: Justice and security

- Women, peace, and security in the work of the UN Security Council

- Preventing violent extremism and countering terrorism

- Planning and monitoring

- Humanitarian coordination

- Crisis response and recovery

- Disaster risk reduction

- Inclusive National Planning

- Public Sector Reform

- Tracking Investments

- Strengthening young women's leadership

- Economic empowerment and skills development for young women

- Action on ending violence against young women and girls

- Engaging boys and young men in gender equality

- Sustainable development agenda

- Leadership and Participation

- National Planning

- Violence against Women

- Access to Justice

- Regional and country offices

- Regional and Country Offices

- Liaison offices

- UN Women Global Innovation Coalition for Change

- Commission on the Status of Women

- Economic and Social Council

- General Assembly

- Security Council

- High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development

- Human Rights Council

- Climate change and the environment

- Other Intergovernmental Processes

- World Conferences on Women

- Global Coordination

- Regional and country coordination

- Promoting UN accountability

- Gender Mainstreaming

- Coordination resources

- System-wide strategy

- Focal Point for Women and Gender Focal Points

- Entity-specific implementation plans on gender parity

- Laws and policies

- Strategies and tools

- Reports and monitoring

- Training Centre services

- Publications

- Government partners

- National mechanisms

- Civil Society Advisory Groups

- Benefits of partnering with UN Women

- Business and philanthropic partners

- Goodwill Ambassadors

- National Committees

- UN Women Media Compact

- UN Women Alumni Association

- Editorial series

- Media contacts

- Annual report

- Progress of the world’s women

- SDG monitoring report

- World survey on the role of women in development

- Reprint permissions

- Secretariat

- 2023 sessions and other meetings

- 2022 sessions and other meetings

- 2021 sessions and other meetings

- 2020 sessions and other meetings

- 2019 sessions and other meetings

- 2018 sessions and other meetings

- 2017 sessions and other meetings

- 2016 sessions and other meetings

- 2015 sessions and other meetings

- Compendiums of decisions

- Reports of sessions

- Key Documents

- Brief history

- CSW snapshot

- Preparations

- Official Documents

- Official Meetings

- Side Events

- Session Outcomes

- CSW65 (2021)

- CSW64 / Beijing+25 (2020)

- CSW63 (2019)

- CSW62 (2018)

- CSW61 (2017)

- Member States

- Eligibility

- Registration

- Opportunities for NGOs to address the Commission

- Communications procedure

- Grant making

- Accompaniment and growth

- Results and impact

- Knowledge and learning

- Social innovation

- UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women

- About Generation Equality

- Generation Equality Forum

- Action packs

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

- Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Gender and cultural diversity in sport, exercise, and performance psychology.

- Diane L. Gill Diane L. Gill University of North Carolina at Greensboro

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.148

- Published online: 26 April 2017

Gender and cultural diversity are ever-present and powerful in sport, exercise, and performance settings. Our cultural identities affect our behaviors and interactions with others. As professionals, we must recognize and value cultural diversity. Gender and culture are best understood within a multicultural framework that recognizes multiple, intersecting identities; power relations; and the action for social justice. Physical activity participants are culturally diverse in many ways, but in other ways cultural groups are excluded from participation, and especially from power (e.g., leadership roles).

Sport, exercise, and performance psychology have barely begun to address cultural diversity, and the limited scholarship focuses on gender. Although the participation of girls and women has increased dramatically in recent years, stereotypes and media representations still convey the message that sport is a masculine activity. Stereotypes and social constraints are attached to other cultural groups, and those stereotypes affect behavior and opportunities. Race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and physical characteristics all limit opportunities in physical activity settings. People who are overweight or obese are particularly subject to bias and discrimination in sport and physical activity. Cultural competence, which refers to the ability to work effectively with people of a different culture, is essential for professionals in sport, exercise, and performance psychology. Not only is it important for individuals to develop their own cultural awareness, understanding, and skills, but we must advocate for inclusive excellence in our programs and organizations to expand our reach and promote physical activity for the health and well-being of all.

- cultural competence

- stereotypes

- weight bias

Introduction

Cultural diversity is a hallmark of society and a powerful influence in sport, exercise, and performance psychology. Participants are diverse in many ways, and physical activity takes place in a culturally diverse world. People carry their gender and cultural identities everywhere. Importantly, culture affects our behaviors and interactions with others. Thus, it is essential that professionals recognize and value cultural diversity.

This article takes a broad view of culture, including gender and extending beyond race, ethnicity, and social class to include physicality (physical abilities and characteristics). The article begins with a guiding framework, then reviews scholarship on gender and culture, and concludes with guidelines for cultural competence.

Culture: Basics and a Guiding Framework

This first section draws from psychology and cultural studies to provide a guiding framework for understanding culture and moving toward cultural competence in professional practice. Culture , however, is complex and not easily defined. Narrow definitions emphasize ethnicity, but we will adopt the common practice and broaden the definition to shared values, beliefs, and practices of an identifiable group of people . Thus, culture includes gender as well as race and ethnicity, and extends to language, spirituality, sexuality, physicality, and so on. Multicultural psychology further emphasizes intersections of identities and the totality of cultural experiences and contexts, which leads to the guiding framework for this article.

Psychology, cultural studies, and related areas all emphasize multiple, intersecting cultural identities; highlight power relations; and call for social action and advocacy. First, we all have multiple, intersecting cultural identities . The mix of identities is unique to each person. For example, two young women may both identify as black, Christian women athletes. One may very strongly identify as a Christian athlete, whereas the other more strongly identifies as a black woman. Moreover, the salience of those identities may vary across contexts. For example, religious identity may be salient in family gatherings but not in athletics. Also, when you are the only person with your identity (e.g., the only girl on the youth baseball team, the only athlete in class), that aspect of your identity is more salient.

The second theme of our framework involves power relations . Culture is more than categories; culture is relational, and cultural relations involve power and privilege. That is, one group has privilege, and other groups are oppressed. Privilege refers to power or institutionalized advantage gained by virtue of valued social identities. Oppression refers to discrimination or systematic denial of resources to those with inferior or less valued identities. Given that we all have many cultural identities, most people have some identities that confer privilege and other identities that lead to oppression. If you are white, male, heterosexual, educated, or able-bodied, you have privilege in that identity; you are more likely to see people who look like you in positions of power and to see yourself in those roles. At the same time, you likely have other identities that lack privilege. Most of us find it easier to recognize our oppression and more difficult to recognize our own privilege.

Recognizing privilege is a key to understanding cultural relations, and that understanding leads to the third theme— action and advocacy . Action and advocacy calls for professionals to develop their own cultural competencies and to work for social justice in our programs and institutions.

Understanding cultural diversity and developing cultural competence is not easy. As well as recognizing multiple, intersecting cultural identities, power relations and action for social justice, sport, exercise, and performance psychologists also must retain concern for the individual. The importance of individualizing professional practice is rightfully emphasized. Cultural competence involves contextualizing professional practice and specifically recognizing cultural context. The ability to simultaneously recognize and consider both the individual and the cultural context is the essence of cultural competence.

Gender and Cultural Diversity in Sport and Physical Activity

Physical activity participants are diverse, but not as diverse as the broader population. Competitive athletics are particularly limited in terms of cultural diversity. School physical education and community sport programs may come closer to reflecting community diversity, but all sport and physical activities reflect cultural restrictions. Gender is a particularly visible cultural influence, often leading to restrictions in sport, exercise and performance settings.

In the United States, the 1972 passage of Title IX prohibiting sex discrimination in educational institutions marked the beginning of a move away from the early women’s physical education model toward the competitive women’s sport programs of today. Participation of girls and women in youth and college sport has exploded in the last generation, particularly in the United States and western European nations. Still, the numbers of female and male participants are not equal. Sabo and Veliz ( 2012 ), in a nationwide study of U.S. high schools, found that overall boys have more sport opportunities than girls, and furthermore, progress toward gender equity, which had advanced prior to 2000 , had reversed since then, resulting in a wider gender gap. Following a 2013 conference in Europe ( http://ec.europa.eu/sport/news/2014/gender_equality_sport_en.htm ), a group of experts developed the report: Gender Equality in Sport: Proposal for Strategic Actions 2014–2020 ( http://ec.europa.eu/sport/events/2013/documents/20131203-gender/final-proposal-1802_en.pdf ).

In considering cultural diversity, it is important to go beyond participation numbers to consider power and privilege. Richard Lapchick’s Racial and Gender Report Card shows racial and gender inequities with little progress. For example, the 2015 report card (Lapchick, 2015 ) indicates that African Americans are slightly overrepresented in U.S. Division I athletics, but other racial and ethnic minorities are very underrepresented (see more statistics and reports at the Institute for Diversity and Ethnics in Sport website: www.tidesport.org ). Reports also show clear power relations. Before Title IX ( 1972 ), more than 90 percent of women’s athletic teams in the United States were coached by women and had a woman athletic director. Today less than half of women’s teams are coached by women (Acosta & Carpenter, 2014 ). White men dominate coaching, even of women’s teams, and administration remains solidly white male. The 2015 racial report card indicated that whites hold 90 percent of the athletic director positions, and less than 10 percent are women.

Although data are limited, the international coaching trends are similar (Norman, 2008 ) and suggest even fewer women coaches at the youth level than at the collegiate and elite levels (Messner, 2009 ). The 2012 London Olympics showcased women athletes and also demonstrated intersecting cultural relations. The United States sent more female than male athletes to London, but women were vastly underrepresented in several delegations; coaching positions are heavily dominated by men, and Olympic officials are not as diverse as the athletes.

Considering exercise, recreation, and the wider range of activities, we see more diversity, but all physical activity is limited by gender, race, socioeconomic status, and especially physical attributes. Lox, Martin Ginis, and Petruzzello ( 2014 ) summarized research and large national surveys on physical activity trends from several countries, predominantly in North America and Europe, noting that evidence continues to show that physical activity decreases across the adult life span, with men more active than women, while racial and ethnic minorities and low-income groups are less active. Physical activity drops dramatically during adolescence, more so for girls than boys, and especially for racial or ethnic minorities and lower income girls (Kimm et al., 2002 ; Pate, Dowda, O’Neill, & Ward, 2007 ).

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2014 ) identifies physical inactivity as a global health problem, noting that about 31 percent of adults are insufficiently active. Inactivity rates are higher in the Americas and Eastern Mediterranean and lowest in Southeast Asia, and men are more active than women in all regions. Abrasi ( 2014 ) reviewed research on barriers to physical activity with women from unrepresented countries, as well as immigrants and underrepresented minorities in North America and Europe. Social responsibilities (e.g., childcare, household work), cultural beliefs, lack of social support, social isolation, lack of culturally appropriate facilities, and unsafe neighborhoods were leading sociocultural barriers to physical activity. Observing others in the family or neighborhood participating had a positive influence.

Despite the clear influence of gender and culture on physical activity behavior, sport, exercise and performance psychology has been slow to recognize cultural diversity. Over 25 years ago, Duda and Allison ( 1990 ) called attention to the lack of research on race and ethnicity, reporting that less than 4 percent of published papers considered race or ethnicity, and most of those were sample descriptions. In an update, Ram, Starek, and Johnson ( 2004 ) reviewed sport and exercise psychology journal articles between 1987 and 2000 for both race and ethnicity and sexual orientation content. They confirmed the persistent void in the scholarly literature, finding only 20 percent of the articles referred to race/ethnicity and 1.2 percent to sexual orientation. Again, most were sample descriptions, and Ram et al. concluded that there is no systematic attempt to include the experiences of marginalized groups.

Considering that conference programs might be more inclusive than publications, Kamphoff, Gill, Araki, and Hammond ( 2010 ) surveyed the Association for Applied Sport Psychology (AASP) conference program abstracts from the first conference in 1986 to 2007 . Only about 10 percent addressed cultural diversity, and most of those focused on gender differences. Almost no abstracts addressed race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, social class, physical disabilities, or any other cultural diversity issue.

Just as publications and conference programs reflect little diversity, our journal editorial boards and professional organizations have been dominated by men, with few women leaders until very recently. The International Society of Sport Psychology (ISSP), which was the first organization founded in 1965 , had all men presidents for over 25 years. AASP began in 1985 with John Silva as president, followed by seven male presidents before Jean Williams became president in 1993 . Similarly, APA Division 47 (Exercise & Sport Psychology) had all male presidents from 1986 until Diane Gill became president more than 10 years later. Nearly all of those presidents have been North American or European and white.

An additional consideration is that our major journals have little international reach. Papaioannou, Machaira, and Theano ( 2013 ) found that the vast majority (82 percent) of articles over 5 years in six major journals were from English-speaking countries, and the continents of Asia, Africa, and South America combined had less than 4 percent. Papaionnau et al. noted a high correlation between continents’ representation on editorial boards and publications, suggesting possible systematic errors or bias in the review process.

The International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology (IJSEP) recently (Schinke, Papaioannou, & Schack, 2016 ) addressed this issue with a special issue on sport psychology in emerging countries. Sørensen, Maro, and Roberts ( 2016 ) reported on gender differences in an HIV/AIDS education intervention through soccer in Tanzania. The program is community-based and delivered by young peer coaches. Their findings highlight cultural intersections and the importance of considering gender along with local culture in programs. Other articles in that special issue report on Botswana’s active sport psychology in both educational programs and with national teams (Tshube & Hanrahan, 2016 ), and the established and continuing sport psychology in Brazil, which includes major research programs on physical activity and well-being as well as applied sport psychology (Serra de Queiroz, Fogaça, Hanrahan, & Zizzi, 2016 ).

Gender Scholarship in Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology

In reviewing the scholarship on cultural diversity, we first focus on gender, which is especially prominent in sport and physical activity, and thus, particularly relevant for sport, exercise, and performance psychology. Gender scholarship in psychology has shifted from early research on sex differences to more current social perspectives emphasizing intersecting identities and cultural relations.

Sex Differences

In their classic review of the early psychology research on sex differences, Maccoby and Jacklin ( 1974 ) concluded that few conclusions could be drawn from the literature on sex differences. Ashmore ( 1990 ) later concluded that average differences are elusive, and the evidence does not support biological dichotomous sex-linked connections. More recent reviews confirm those conclusions.

Hyde ( 2005 ) reviewed 46 meta-analyses of the extensive literature on sex differences and concluded that results support the gender similarities hypothesis. That is, males and females are more alike than different on psychological variables, and overstated claims of gender differences cause harm and limit opportunities. Zell, Krizan, and Teeter ( 2015 ) used metasynthesis to evaluate the many meta-analyses on sex differences. They found that the vast majority of differences were small and constant across age, culture, and generations, and concluded that the findings provide compelling support for the gender similarities hypothesis.

Social Perspectives and Stereotypes

Today, most psychologists look beyond the male–female dichotomy to social-cognitive models and cultural relations. As sociologist Bernard ( 1981 ) proposed over 30 years ago, the social worlds for females and males are different even when they appear similar. Today, the social worlds are still not the same for girls and boys in youth sport, male and female elite athletes, or women and men in exercise programs.

Gender stereotypes are particularly pervasive in sport and physical activity. Metheny ( 1965 ) identified gender stereotypes in her classic analysis, concluding that it was not appropriate for women to engage in activities involving bodily contact, force, or endurance. Despite women’s increased participation, those gender stereotypes persist 50 years later. Continuing research (e.g., Hardin & Greer, 2009 ; Riemer & Visio, 2003 ) confirms that expressive activities (e.g., dancing, gymnastics) are seen as feminine; combative, contact sports as masculine; and other activities (e.g., tennis, swimming) as neutral.

Sport studies scholars have continued that research, with emphasis on sport media. Early research (e.g., Messner, Duncan, & Jensen, 1993 ) showed that female athletes receive much less and different coverage, with the emphasis on athletic ability and accomplishments for men and on femininity and physical attractiveness for women. Despite the increased participation of girls and women at all levels, the media coverage has not changed much. In the most recent update of a 25-year longitudinal study, Cooky, Messner, and Musto ( 2015 ) found televised coverage of women’s sport “dismally low” with no progress. Media representations are a major source of stereotypes, and evidence indicates that all forms of the media send the message that sport is for men.

Stereotypes are a concern because we act on them, restricting opportunities for everyone. Fredericks and Eccles ( 2004 , 2005 ) found that parents held gender-stereotyped beliefs and provided more opportunities and encouragement for sons than for daughters. Chalabaev, Sarrazin, and Fontayne ( 2009 ) found that stereotype endorsement (girls perform poorly in soccer) negatively predicted girls’ performance, with perceived ability mediating the relationship.

Chalabaev, Sarrazin, Fontayne, Boiche, and Clément-Guillotin ( 2013 ) reviewed the literature on gender stereotypes and physical activity, confirming the persistent gender stereotypes in sport and the influence of stereotypes on participation and performance. They further suggested that stereotypes may influence participation and behavior even if they are not internalized and believed. We know the stereotypes, and when situations call attention to the stereotype (e.g., there are only three girls on the co-ed team), it is especially likely to affect us. Beilock, Jellison, Rydell, McConnell, and Carr ( 2006 ) showed that telling male golfers the females performance better on a golf-putting task decreased their performance, and a follow-up study (Stone & McWhinnie, 2008 ) found females similarly susceptible to stereotype threat.

Gender and Physical Self-Perceptions . As part of Eccles’s continuing developmental research on gender and achievement, Eccles and Harrold ( 1991 ) confirmed that gender influences children’s sport achievement perceptions and behaviors and that these gender differences reflect gender-role socialization. Gender differences are larger in sport than in other domains, and as Eccles and Harold noted, even in sport the perceived gender differences are much larger than actual gender differences in sport-related skills.

Considerable research also shows that self-perceptions affect sport and physical activity behavior. For example, Jensen and Steele ( 2009 ) found that girls who experienced weight criticism and body dissatisfaction engaged in less vigorous physical activity. No similar results were found for boys, and so the researchers concluded that body dissatisfaction is important in girls’ physical activity. Slater and Tiggemann ( 2011 ) looked at gender differences in teasing, body self-perceptions, and physical activity with a large sample of adolescents and concluded that teasing and body image concerns may contribute to girls’ lower rates of participation in physical activity.

Physical activity also has the potential to enhance girls’ and women’s physical self-perceptions and activity. Several studies (e.g., Craft, Pfeiffer, & Pivarnik, 2003 ) confirm that exercise programs can enhance self-perceptions, and Hausenblas and Fallon’s ( 2006 ) meta-analysis found that physical activity leads to improved body image. Greenleaf, Boyer, and Petrie ( 2009 ) looked at the relationship of high school sport participation to psychological well-being and physical activity in college women. They found that body image, physical competence, and instrumentality mediated the relationship for both activity and well-being, suggesting that benefits accrue as a result of more positive self-perceptions.

Related research suggests that sport and physical activity programs can foster positive youth development, particularly for girls. A report for the Women’s Sports Foundation— Her Life Depends on It III (Staurowsky et al., 2015 )—updated previous reports and confirmed that physical activity helps girls and women lead healthy, strong, and fulfilled lives. That report, which reviewed over 1500 studies, documented the important role of physical activity in reducing the risk of major health issues (e.g., cancer, coronary heart disease, dementias) as well as depression, substance abuse, and sexual victimization. The report further concluded that all girls and women are shortchanged in realizing the benefits of physical activity and that females of color or with disabilities face even greater barriers.

Sexuality and Sexual Prejudice

Sexuality and sexual orientation are often linked with gender, but biological sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation are not necessarily related. Furthermore, male–female biological sex and homosexual–heterosexual orientations are not the clear, dichotomous categories that we often assume them to be. Individuals’ gender identities and sexual orientations are varied and not necessarily linked. Gender identity is one’s internal sense of being male or female. For transgender people, gender identity is not consistent with their biological sex (Krane & Mann, 2014 ).

Sexual orientation refers to one’s sexual or emotional attraction to others and is typically classified as heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual. Herek ( 2000 ) suggests that sexual prejudice is the more appropriate term for discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, but related scholarship typically refers to homophobia . As Krane and Mann ( 2014 ) point out, heterosexism , which refers to privilege of heterosexual people, is common in sport—we assume people are heterosexual, and we discriminate against those who do not fit heterosexist stereotypes. Also, we clearly discriminate on the basis of gender identity against transgender people.

Messner ( 2002 ) argues that homophobia leads boys and men to conform to a narrow definition of masculinity and bonds men together as superior to women. We expect to see men, but not women, take active, dominant roles expected of athletes. Despite the visibility of a few prominent gay and lesbian athletes and the very recent expansion of civil rights, sexual prejudice persists. Anderson ( 2011 ) suggests that men, and particularly gay men, have more latitude in sports today, but sport is still a space of restricted masculinity and sexual prejudice.

The limited data-based research confirms that sport is a hostile climate for lesbian/gay/bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people. In one of the few empirical studies, Morrow and Gill ( 2003 ) reported that both physical education teachers and students witnessed high levels of homophobic and heterosexist behaviors in public schools. Gill, Morrow, Collins, Lucey, and Schultz ( 2006 ) subsequently examined attitudes toward racial and ethnic minorities, older adults, people with disabilities, and sexual minorities. Overall, attitudes were markedly more negative for both gay men and lesbians than for other minority groups, with males especially negative toward gay men. Vikki Krane ( 2001 ) (Barber & Krane, 2005 ; Krane & Barber, 2003 ; Krane & Mann, 2014 ; Krane & Symons, 2014 ) have done much of the related work in sport and exercise psychology, and that research indicates that sexual prejudice is common in sport at all levels. Most of that research is from North America and Europe, but hostile climates have been reported around the world. For example, Shang and Gill ( 2012 ) found the climate in Taiwan athletics hostile for those with nonconventional gender identity or sexual orientation, particularly for male athletes.

In a review of research on LGBT issues in sport psychology, Krane, Waldron, Kauer, and Semerjian ( 2010 ) found no articles focused on transgender athletes. Lucas-Carr and Krane ( 2011 ) noted that transgender athletes are largely hidden. Hargie, Mitchell, and Somerville ( 2015 ) interviewed 10 transgender athletes and found common themes of intimidation, alienation, fear of public spaces, and overall effects of being deprived of the social, health, and well-being aspects of sport. As Lucas-Carr and Krane concluded, creation of safe and compassionate sport settings for all athletes, including trans athletes, is an ethical responsibility. On a promising note, Krane and Symons ( 2014 ) described several programs that promote inclusive sport climates, including Fair go, sport! an Australian social inclusion project focusing on gender and sexual diversity.

Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment, which has clear gender and sexuality connotations, has received considerable attention in psychology (e.g., Koss, 1990 ). Kari Fasting and Celia Brackenridge have led much of the related research and programs on sexual harassment in sport. The related scholarship indicates that the sport climate fosters sexual harassment and abuse; that young, elite female athletes are particularly vulnerable; that neither athletes nor coaches have education or training about the issues; and that both research and professional development are needed in sport and exercise psychology to address the issues (Brackenridge, 2001 ; Brackenridge & Fasting, 2002 ; Fasting, Brackenridge, & Sundgot-Borgen, 2004 ; Fasting, Brackenridge, & Walseth, 2007 ). That research comes from several European countries and Australia. Rodriguez and Gill ( 2011 ) subsequently reported similar findings with former Puerto Rican women athletes.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC, 2007 ) recognizes the problem and defines sexual harassment as “behavior towards an individual or group that involves sexualized verbal, non-verbal or physical behavior, whether intended or unintended, legal or illegal, that is based on an abuse of power and trust and that is considered by the victim or a bystander to be unwanted or coerced” (p. 3). Fasting ( 2015 ) recently reviewed the research and suggested building on the recent policies of major organizations such as the IOC to curb harassment, as well as continued research to advance systematic knowledge.

Race, Ethnicity, and Social Class

Race and ethnicity are just as salient as gender in sport and physical activity but have largely been ignored in our literature. As noted in the earlier section on gender and cultural diversity in sport and exercise psychology, there is a striking void in our journals on race and ethnicity, and virtually no research has been published on social class in sport, exercise, and performance psychology.

Although race and ethnicity are often conflated, they are not the same, and race is not a clear, biologically determined category. As Markus ( 2008 ) argued, race and ethnicity are not objective, identifying characteristics, but the meanings that we associate with those characteristics carry power or privilege. The psychology scholarship on race and ethnicity most relevant to sport, exercise, and performance psychology involves health disparities and stereotypes.

Race, Ethnicity, and Health Disparities

Health disparities are well documented, showing that racial and ethnic minorities and low-income people receive suboptimal health care (see 2011 National Health Quality and Disparities Reports; available at www.ahrq.gov ). Health disparities are relevant to sport, exercise, and performance psychology in that physical activity is a key health behavior.

Few studies have looked at race and ethnicity or social class disparities in relation to sport and physical activity. Heesch, Brown, and Blanton ( 2000 ) examined exercise barriers with a large sample of women over age 40, including African American, Hispanic, Native American, and white women. They found several common barriers, but they also reported variations by racial and ethnic group, and cautioned that their results and specific community needs precluded definitive guidelines for interventions. Crespo ( 2005 ) outlined the cultural barriers to physical activity for minority populations, including those with lower socioeconomic status, and called for professionals to consider unique needs and cultural constraints when giving advice on exercise. Ethnicity and social class are particularly relevant when considering migrant and refugee populations in Western countries. For example, Frisby ( 2011 ) interviewed Chinese immigrant women in Canada to better understand barriers and guidance for promising inclusion practices in sport and recreation. Promising practices included promoting citizen engagement, working from a broader social ecological framework, improving access policies, and fostering community partnerships to facilitate cross-cultural connections.

Stereotypes and Stereotype Threat

Steele’s ( 1997 ; Steele, Spencer, & Aronson, 2002 ) extensive research on stereotype threat , which is the fear of confirming negative stereotypes, has been extended to sport. Steele’s research indicates that stereotype threat particularly affects those minority group members who have abilities and are motivated to succeed. Steele also suggests that simple manipulations (e.g., telling students test scores are not related to race) can negate the effects. Beilock and McConnell ( 2004 ) reviewed the stereotype threat in sport literature, concluding that negative stereotypes are common in sport and lead to performance decrements, especially when the performers are capable and motivated.

Racial and ethnic stereotypes are well documented. For example, Devine and Baker ( 1991 ) found that the terms unintelligent and ostentatious were associated with black athlete , and Krueger ( 1996 ) found that both black and white participants perceived black men to be more athletic than white men. Johnson, Hallinan, and Westerfield ( 1999 ) asked participants to rate attributes of success in photos of black, white, Hispanic, and composite male athletes. Success for the black athlete was attributed to innate abilities, but the white athlete’s success was reported to come from hard work and leadership ability. Interestingly, no stereotyping was evident for the Hispanic athlete.

More important, these stereotypes affect behavior. When Stone, Perry, and Darley ( 1997 ) had people listen to a college basketball game and evaluate players, they found that both white and black students rated black players as more athletic and white players as having more basketball intelligence. Stone, Lynch, Sjomeling, and Darley ( 1999 ) found that black participants performed worse on a golf task when told the test was of sport intelligence, whereas white participants performed worse when told the test was of natural ability.

Although much of the work on stereotype threat involves race and ethnicity, gender and athlete stereotype threat effects have also been found. Heidrich and Chiviacowsky ( 2015 ) found that female participants in the stereotype threat condition (they were told women do worse than men) had lower self-efficacy and performed worse on a soccer task than those in the nonstereotype threat condition. Feltz, Schneider, Hwang, and Skogsberg ( 2013 ) found that student-athletes perceive stereotype threat in the classroom, and those with higher athletic identity perceived more threat. They also found that perceived coach’s regard for their academic ability affected athletes’ susceptibility and could serve as a buffer to stereotype threat.

Physicality and Weight Bias

Sport, exercise, and performance are physical activities, and thus physical characteristics are prominent. Moreover, opportunity is limited by physical abilities, skills, size, fitness, and appearance. Exclusion on the basis of physicality is nearly universal in sport and physical activity, and this exclusion is a public health and social justice issue.

Physical Abilities and Disabilities . Rimmer ( 2005 ) notes that people with physical disabilities are one of the most inactive segments of the population, and argues that organizational policies, discrimination, and social attitudes are the real barriers. Gill, Morrow, Collins, Lucey, and Schultz ( 2010 ) examined the climate for minority groups (racial and ethnic minorities, LGB people, older adults, and people with disabilities) in organized sport, exercise, and recreational settings. Notably, the climate was rated as most exclusionary for people with disabilities.

Semerjian ( 2010 ), one of the few scholars who has addressed disability issues in sport and exercise psychology, highlights the larger cultural context as well as the intersections of race, gender, and class with physicality. Physical skill, strength, and fitness, or more correctly, the lack of skill, strength, and fitness, are key sources of restrictions and overt discrimination in sport and exercise. Physical size, particularly obesity, is a prominent source of social stigma, and weight bias is a particular concern.

Obesity and Weight Bias

Considerable research (e.g., Brownell, 2010 ; Puhl & Heuer, 2011 ) has documented clear and consistent stigmatization and discrimination of the obese in employment, education, and health care. Obese individuals are targets for teasing, more likely to engage in unhealthy eating behaviors, and less likely to engage in physical activity (Faith, Leone, Ayers, Heo, & Pietrobelli, 2002 ; Puhl & Wharton, 2007 ; Storch et al., 2007 ). Check the Rudd Center website ( www.uconnruddcenter.org ) for resources and information on weight bias in health and educational settings.

Weight discrimination is associated with stress and negative health outcomes. Sutin, Stephan, and Terracciano ( 2015 ), using data from two large U.S. national studies, found that weight discrimination was associated with increased mortality risk and that the association was stronger than that between mortality and other forms of discrimination. Vartanian and Novak ( 2011 ) found experiences with weight stigma had negative impact on body satisfaction and self-esteem, and importantly, weight stigma was related to avoidance of exercise.

Exercise and sport science students and professionals are just as likely as others to hold negative stereotypes. Chambliss, Finley, and Blair ( 2004 ) found a strong anti-fat bias among exercise science students, and Greenleaf and Weiller ( 2005 ) found that physical education teachers held anti-fat bias and believed obese people were responsible for their obesity. O’Brien, Hunter, and Banks ( 2007 ) found that physical education students had greater anti-fat bias than students in other health areas, and also had higher bias at year 3 than at year 1; this finding suggests that their bias was not countered in their pre-professional programs. Robertson and Vohora ( 2008 ) found a strong anti-fat bias among fitness professionals and regular exercisers in England. Donaghue and Allen ( 2016 ) found that personal trainers recognized that their clients had unrealistic weight goals but still focused on diet and exercise to reach goals.

Weight Stigma and Health Promotion

Anti-fat bias and weight discrimination among professionals has important implications for physical activity and health promotion programs. Thomas, Lewis, Hyde, Castle, and Komesaroff ( 2010 ) conducted in-depth interviews with 142 obese adults in Australia about interventions for obesity. Participants supported interventions that were nonjudgmental and empowering, whereas interventions that were stigmatizing or blamed and shamed individuals for being overweight were not viewed as effective. They called for interventions that supported and empowered individuals to improve their lifestyle. Hoyt, Burnette, and Auster-Gussman ( 2014 ) reported that the “obesity as disease” message may help people feel more positive about their bodies, but they are less likely to engage in health-promoting behaviors. More positive approaches that take the emphasis off weight and highlight health gains are more promising.

Cultural Competence

Cultural competence, which refers to the ability to work effectively with people who are of a different culture, takes cultural diversity directly into professional practice. Culturally competent professionals act to empower participants, challenge restrictions, and advocate for social justice.

Cultural Sport and Exercise Psychology

A few dedicated scholars have called for a cultural sport psychology in line with our guiding framework (e.g., Fisher, Butryn, & Roper, 2003 ; Ryba & Wright, 2005 ). Schinke and Hanrahan’s ( 2009 ) Cultural Sport Psychology , and Ryba, Schinke, and Tenenbaum’s ( 2010 ) The Cultural Turn in Sport Psychology , brought together much of the initial scholarship. Special issues devoted to cultural sport psychology were published in the International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology (Ryba & Schinke, 2009 ) and the Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology special issue (Schinke & Moore, 2011 ). These works provide a base and call for cultural competence and social justice.

Cultural Competence for Professionals

Cultural competence is a required professional competency in psychology and many health professions, and is essential for anyone working with others, including sport, exercise, and performance psychology professionals. Cultural competence includes understanding and action, at both the individual and organizational level.

Most psychology resources follow Sue’s ( 2006 ) model of cultural competence with three key components: awareness of one’s own cultural values and biases, understanding of other worldviews, and development of culturally appropriate skills . In line with Sue’s model, the American Psychological Association (APA) developed the APA ( 2003 ) multicultural guidelines that call for psychologists to develop awareness of their own cultural attitudes and beliefs, understanding of other cultural perspectives, and culturally relevant skills. Furthermore, the guidelines call for action at the organizational level for social justice.

The ISSP developed a position stand (Ryba, Stambulova, Si, & Schinke, 2013 ) that describes three major areas of cultural competence: cultural awareness and reflexivity , culturally competent communication , and culturally competent interventions . Awareness and reflectivity refers to recognition of between- and within-culture variations as well as reflection on both the client and one’s own cultural background. Culturally competent communication involves meaningful dialogue and shared language. Culturally competent interventions recognize culture while avoiding stereotyping, take an idiosyncratic approach, and stand for social justice.

Cultural Competence and Inclusive Excellence

Cultural competence extends beyond individual competencies to all levels, including instruction, program development, hiring practices, and organizational policies and procedures. The APA multicultural guidelines call for professionals to recognize and value cultural diversity, continually seek to develop their multicultural knowledge and skills, translate those understandings into practice, and extend their efforts to advocacy by promoting organizational change and social justice. Cultural competence at the individual level is a professional responsibility. Inclusive excellence moves cultural competence to the institutional level. That is, we work for changes in organizations and policies that make our programs accessible and welcoming for diverse people. Taking inclusive excellence into sport, exercise, and performance psychology calls for recognizing and valuing diversity and social justice as goals that will enhance our programs and institutions, as well as bring the benefits of physical activity to participants. Therefore, we work not only to develop our individual cultural competencies, but also to effect change at the institutional level to ensure that our programs are inclusive and excellent.

Gender and culture are highly visible and influential in sport, exercise, and performance settings. Gender, race, ethnicity, social class, and physical characteristics often limit opportunities, sometimes through segregation and discrimination, but often through perceptions and stereotype influence. Sport, exercise, and performance psychology research confirms the influence of culture and offers explanations, but sport, exercise and performance psychology has made little progress in promoting cultural competence and social justice.

- Abrasi, I. N. (2014). Socio-cultural barriers to attaining recommended levels of physical activity among females: A review of literature. Quest , 66 , 448–467.

- Acosta, V. R. , & Carpenter, L. J. (2014). Women in intercollegiate sport: A longitudinal, national study thirty-seven year update 1977–2014. Retrieved from http://www.acostacarpenter.org/ .

- American Psychological Association (APA) . (2003). Guidelines on multicultural education, training, research, practice and organizational change for psychologists. American Psychologist , 58 , 377–402.

- Anderson, E. (2011). Masculinities and sexualities in sport and physical culture: three decades of evolving research. Journal of Homosexuality , 58 (5), 565–578.

- Ashmore, R. D. (1990). Sex, gender, and the individual. In L. A. Pervin (Ed.), Handbook of personality theory and research (pp. 486–526). New York: Guilford Press.

- Barber, H. , & Krane, V. (2005). The elephant in the locker room: Opening the dialogue about sexual orientation on women’s sport teams. In M. B. Anderson (Ed.), Sport psychology in practice (pp. 265–285). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Beilock, S. L. , Jellison, W. A. , Rydell, R. J. , McConnell, A. R. , & Carr, T. H. (2006). On the causal mechanisms of stereotype threat: Can skills that don’t rely heavily on working memory still be threatened? . Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 32 , 1059–1071.

- Beilock, S. L. , & McConnell, A. R. (2004). Stereotype threat and sport: Can athletic performance be threatened? Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology , 26 , 597–609.

- Bernard, J. (1981). The female world . New York: Free Press.

- Brackenridge, C. (2001). Spoilsports: Understanding and preventing sexual exploitation in sport . New York: Routledge.

- Brackenridge, C. H. , & Fasting, K . (Eds.). (2002). Sexual harassment and abuse in sport: International research and policy perspectives . London: Whiting and Birch.

- Brownell, K. D. (2010). The humbling experience of treating obesity: Should we persist or desist? Behavior Research and Therapy , 48 , 717–719.

- Chalabaev, A. , Sarrazin, P. , & Fontayne, P. (2009). Stereotype endorsement and perceived ability as mediators of the girls’ gender orientation-soccer performance relationship . Psychology of Sport and Exercise , 10 , 297–299.

- Chalabaev, A. , Sarrazin, P. , Fontayne, P. , Bioche, J. , & Clément-Guillotin, C. (2013). The influence of sex stereotypes and gender roles on participation and performance in sport and exercise: Review and future directions . Psychology of Sport and Exercise , 14 , 136–144.

- Chambliss, H. O. , Finley, C. E. , & Blair, S. N. (2004). Attitudes toward obese individuals among exercise science students. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise , 36 , 468–474.

- Cooky, C. , Messner, M. A. , & Musto, M. (2015). ‘‘It’s dude time!’’: A quarter century of excluding women’s sports in televised news and highlight shows . Communication and Sport , 3 (3), 261–287.

- Craft, L. L. , Pfeiffer, K. A. , & Pivarnik, J. M. (2003). Predictors of physical competence in adolescent girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence , 32 , 431–438.

- Crespo, C. J. (2005). Physical activity in minority populations: Overcoming a public health challenge. The President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports Research Digest , 6 (2).

- Devine, P. G. , & Baker, S. M. (1991). Measurement of racial stereotype subtyping. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 17 (1), 44–50.

- Donaghue, N. , & Allen, M. (2016). “People don’t care as much about their health as they do about their looks”: Personal trainers as intermediaries between aesthetic and health-based discourses of exercise participation and weight management . International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology , 14 (1), 42–56.

- Duda, J. L. , & Allison, M. T. (1990). Cross-cultural analysis in exercise and sport psychology: A void in the field. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology , 12 , 114–131.

- Eccles, J. S. , & Harrold, R. D. (1991). Gender differences in sport involvement: Applying the Eccles’ expectancy-value model. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology , 3 , 7–35.

- Faith, M. S. , Leone, M. A. , Ayers, T. S. , Heo, M. , & Pietrobelli, A. (2002). Weight criticism during physical activity, coping skills, and reported physical activity in children. Pediatrics , 110 (2), e23.

- Fasting, K. (2015). Assessing the sociology of sport: On sexual harassment research and policy. International Review for the Sociology of Sport , 50 (4–5), 437–441.

- Fasting, K. , Brackenridge, C. , & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2004). Prevalence of sexual harassment among Norwegian female elite athletes in relation to sport type. International Review for the Sociology of Sport , 39 (4), 373–386.

- Fasting, K. , Brackenridge, C. , & Walseth, K. (2007). Women athletes’ personal responses to sexual harassment in sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology , 19 (4), 419–433.

- Feltz, D. L. , Schneider, R. , Hwang, S. , & Skogsberg, N. J. (2013). Predictors of Collegiate Student-Athletes’ susceptibility to stereotype threat . Journal of College Student Development , 54 , 184–201.

- Fisher, L. A. , Butryn, T. M. , & Roper, E. A. (2003). Diversifying (and politicizing) sport psychology through cultural studies: A promising perspective. The Sport Psychologist , 17 , 391–405.

- Fredericks, J. A. , & Eccles, J. S. (2004). Parental influences on youth involvement in sports. In M. R. Weiss (Ed.), Developmental sport and exercise psychology: A lifespan perspective . (pp. 145–164). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Fredericks, J. A. , & Eccles, J. S. (2005). Family socialization, gender and sport motivation and involvement. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology , 27 , 3–31.

- Frisby, W. (2011). Promising physical activity inclusion practices for Chinese immigrant women in Vancouver, Canada. Quest , 63 , 135–147.

- Gill, D. L. , Morrow, R. G. , Collins, K. E. , Lucey, A. B. , & Schultz, A. M. (2006). Attitudes and sexual prejudice in sport and physical activity. Journal of Sport Management , 20 , 554–564.

- Gill, D. L. , Morrow, R. G. , Collins, K. E. , Lucey, A. B. , & Schultz, A. M. (2010). Perceived climate in physical activity settings. Journal of Homosexuality , 57 , 895–913.

- Greenleaf, C. , Boyer, E. M. , & Petrie, T. A. (2009). High school sport participation and subsequent psychological well-being and physical activity: The mediating influences of body image, physical competence and instrumentality. Sex Roles , 61 , 714–726.

- Greenleaf, C. , & Weiller, K. (2005). Perceptions of youth obesity among physical educators. Social Psychology of Education , 8 , 407–423.

- Hardin, M. , & Greer, J. D. (2009). The influence of gender-role socialization, media use and sports participation on perceptions of gender-appropriate sports. Journal of Sport Behavior , 32 , 207–226.

- Hargie, O. D. W. , Mitchell, D. H. , & Somerville, I. J. A. (2015, online pub. April 22, 2015). ‘People have a knack of making you feel excluded if they catch on to your difference’: Transgender experiences of exclusion in sport . International Review for the Sociology of Sport , 1–17.

- Hausenblas, H. A. , & Fallon, E. A. (2006). Exercise and body image: a meta-analysis. Psychology and Health , 21 , 33–47.

- Heesch, K. C. , Brown, D. R. , & Blanton, C. J. (2000). Perceived barriers to exercise and stage of exercise adoption in older women of different racial/ethnic groups. Women and Health , 30 , 61–76.

- Heidrich, C. , & Chiviacowsky, S. (2015). Stereotype threat affects learning of sport motor skills. Psychology of sport and Exercise , 18 , 42–46.

- Herek, G. M. (2000). Psychology of sexual prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science , 9 , 19–22.

- Hoyt, C. L. , Burnette, J. L. , & Auster-Gussman, L. (2014). “Obesity is a disease”: Examining the self-regulatory impact of this public-health message . Psychological Science , 25 , 997–1002.

- Hyde, J. S. (2005). The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist , 60 , 581–592.

- International Olympic Committee (IOC) . (2007, February). IOC adopts consensus statement on “sexual harassment and abuse. ” Retrieved from https://www.olympic.org/search?q=sexual+harassment&filter=documents .

- Jensen, C. D. , & Steele, R. G. (2009). Body dissatisfaction, weight criticism, and self-reported physical activity in preadolescent children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 34 , 822–826.

- Johnson, D. L. , Hallinan, C. J. , & Westerfield, R. C. (1999). Picturing success: Photographs and stereotyping in men’s collegiate basketball. Journal of Sport Behavior , 22 , 45–53.

- Kamphoff, C. S. , Gill, D. L. , Araki, K. , & Hammond, C. C. (2010). A content analysis of cultural diversity in the Association for Applied Sport Psychology’s conference programs. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology , 22 , 231–245.

- Kimm, S. Y S , Glynn, N. W , Kriska, A. M , Barton, B. A. , Kronsberg, S. S. , Daniels, S. R. , et al. (2002). Decline in physical activity in Black girls and White girls during adolescence. New England Journal of Medicine , 347 , 709–715.

- Koss, M. P. (1990). The women’s mental health research agenda. American Psychologist , 45 , 374–380.

- Krane, V. (2001). One lesbian feminist epistemology: Integrating feminist standpoint, queer theory, and feminist cultural studies. The Sport Psychologist , 15 (4), 401–411.

- Krane, V. , & Barber, H. (2003). Lesbian experiences in sport: A social identity perspective. Quest , 55 , 328–346.

- Krane, V. , & Mann, M. (2014). Heterosexism, homonegativism, and transprejudice. In R. C. Eklund & G. Tenenbaum (Eds.), Encyclopedia of sport and exercise psychology (pp. 336–338). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Krane, V. , & Symons, C. (2014). Gender and sexual orientation. In A. Papaionnou & D. Hackfort (Eds.), Routledge companion to sport and exercise psychology (pp. 119–135). New York: Routledge.

- Krane, V. , Waldron, J. J. , Kauer, K. J. , & Semerjian, T. (2010). Queering sport psychology. In T. Ryba , R. Schinke , & G. Tennenbaum (Eds.), The cultural turn in sport and exercise psychology (pp. 153–180). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Krueger, J. (1996). Personal beliefs and cultural stereotypes about racial characteristics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 71 , 536–548.

- Lapchick, R. (2015). The 2015 racial and gender report card . Retrieved from http://www.tidesport.org .

- Lox, C. L. , Martin Ginis, K. A. , & Petruzzello, S. J. (2014). The psychology of exercise: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). Scottsdale, AZ: Holcomb Hathaway.

- Lucas-Carr, C. B. , & Krane, V. (2011). What is the T in LGBT? Supporting transgender athletes through sport psychology. The Sport Psychologist , 25 (4), 532–548.

- Maccoby, E. , & Jacklin, C. (1974). The psychology of sex differences . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Markus, H. R. (2008). Pride, prejudice, and ambivalence: Toward a unified theory of race and ethnicity . American Psychologist , 63 (8), 651–670.

- Messner, M. A. (2002). Taking the field: Women, men, and sports . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Messner, M. A. (2009). It’s all for the kids: Gender, families, and youth sports . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Messner, M. A. , Duncan, M. C. , & Jensen, K. (1993). Separating the men from the girls: The gendered language of televised sports. In D. S. Eitzen (Ed.), Sport in contemporary society: An anthology (4th ed., pp. 219–233). New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Metheny, E. (1965). Symbolic forms of movement: The feminine image in sports. In E. Metheny (Ed.), Connotations of movement in sport and dance (pp. 43–56). Dubuque, IA: Brown.

- Morrow, R. G. , & Gill, D. L. (2003). Perceptions of homophobia and heterosexism in physical education. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport , 74 , 205–214.

- Norman, L. (2008). The UK coaching system is failing women coaches. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching , 3 (4), 447–467.

- O’Brien K. S. , Hunter J. A. , & Banks, M. (2007). Implicit anti-fat bias in physical educators: Physical attributes, ideology and socialization. International Journal of Obesity , 31 (2), 308–314.

- Papaioannou, A. G. , Machaira, E. , & Theano, V. (2013). Fifteen years of publishing in English language journals of sport and exercise psychology: authors’ proficiency in English and editorial boards make a difference . International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology , 11 (1), 1–10.

- Pate, R. R. , Dowda, M. , O’Neill, J. R. , & Ward, D. S. (2007). Change in physical activity participation among adolescent girls from 8th to 12th grade. Journal of Physical Activity and Health , 4 , 3–16.

- Puhl, R. , & Heuer, C. A. (2011). Obesity stigma: Important considerations for public health. American Journal of Public Health , 100 , 1019–1028.

- Puhl, R. M. , & Wharton, C. M. (2007). Weight bias: A primer for the fitness Industry. ACSM’s Health and Fitness Journal , 11 (3), 7–11.

- Ram, N. , Starek, J. , & Johnson, J. (2004). Race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation: Still a void in sport and exercise psychology. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology , 26 , 250–268.

- Riemer, B. A. , & Visio, M. E. (2003). Gender typing of sports: an investigation of Metheny’s classification. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport , 74 , 193–204.

- Rimmer, J. H. (2005). The conspicuous absence of people with disabilities in public fitness and recreation facilities: Lack of interest or lack of access? American Journal of Health Promotion , 19 , 327–329.

- Robertson, N. , & Vohora, R. (2008). Fitness vs. fatness: Implicit bias towards obesity among fitness professionals and regular exercisers. Psychology of Sport and Exercise , 9 , 547–557.

- Rodriguez, E. A. , & Gill, D. L. (2011). Sexual harassment perceptions among Puerto Rican female former athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology , 9 , 323–337.