Imagination is More Important than Knowledge: Essay Example

Imagination is more important than knowledge: essay introduction, imagination is better than knowledge: essay body, imagination is more important than knowledge: conclusion.

“Imagination is more important than knowledge,” is a famous quote of Albert Einstein. There are only a couple of words in this line, but if we think logically, it encloses the whole world. Imagination is a bequest of life and is indeed far more significant than knowledge. If we have the capability of imagining things, we can craft our world.

Imagination is not significant just for us as individuals but also for the community in general. It can also be interpreted as the fundamental element of theology and can be better articulated through contemplation. There have been great philosophers in the past who imagined the unattainable, and today our societies have certain values that are very relevant.

Simultaneously to be very dominant, imagination is also very risky. It all depends on the direction towards which we orient our imagination. Just like in the case of fire, if it becomes uncontrollable, it spells havocs, but if it is harnessed properly, it contributes to the development and wellbeing of the people. So our imagination should be oriented towards the positive or constructive direction rather than the negative or destructive one.

On the one hand, where positive approach in imagination improves life values, standards and progress, the negative approach is bound to lead the individuals towards fake things and feelings such as panic, intolerance, nervousness, etc. In the negative imagination, people lose their interface with the truth.

All the inventions and developments that have today become inseparable parts of our lives are results of positive imagination only. Some people imagined these things and converted them into reality. Human beings owe the transformation from Stone Age to being civilized to positive imagination. This is what positive imagination can do.

Knowledge is also important because simply by imagining things, one cannot convert them into reality. An intellectual mind is required for such tasks. But without imagination, knowledge would be of no use. We would be stagnant as far as development is concerned.

Like for instance, if Thomas Alva Edison were aware of the light (current) generating system but didn’t have the foresight to make useful things, then today we would not have the so important thing called bulb. Imagination is the foundation of contentment and pleasure in our lives. It provides us with lots of amusement, leisure and above all makes us more lively and humane.

Knowledge can be gained from various textbooks and lectures, but what about innovation? Unless we combine innovation and knowledge, there is no point in studying. Innovation comes from imagination, and imagination cannot be learned at schools or colleges. To put it more strongly, imagination is a revolution – in a good sense – and dominant, whereas knowledge is merely an attained instrument.

It is always good to acquire knowledge, but having the ability to imagine is far more important and inevitable. By acquiring knowledge, we learn things, but my imagination, we learn how to comprehend the things that we have learned. This comprehension further increases our knowledge.

Above all, the knowledge that we acquire is again a result of imagination. We don’t get knowledge out of knowledge but out of imagination that guides us to knowledge. So imagination is a sort of concierge to knowledge. We cannot gain knowledge unless we have imagination. So imagination is more important than knowledge.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2020, April 19). Imagination is More Important than Knowledge: Essay Example. https://studycorgi.com/philosophy-imagination-is-more-important-than-knowledge/

"Imagination is More Important than Knowledge: Essay Example." StudyCorgi , 19 Apr. 2020, studycorgi.com/philosophy-imagination-is-more-important-than-knowledge/.

StudyCorgi . (2020) 'Imagination is More Important than Knowledge: Essay Example'. 19 April.

1. StudyCorgi . "Imagination is More Important than Knowledge: Essay Example." April 19, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/philosophy-imagination-is-more-important-than-knowledge/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Imagination is More Important than Knowledge: Essay Example." April 19, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/philosophy-imagination-is-more-important-than-knowledge/.

StudyCorgi . 2020. "Imagination is More Important than Knowledge: Essay Example." April 19, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/philosophy-imagination-is-more-important-than-knowledge/.

This paper, “Imagination is More Important than Knowledge: Essay Example”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: November 9, 2023 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Essay on Imagination Is More Important Than Knowledge

Students are often asked to write an essay on Imagination Is More Important Than Knowledge in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Imagination Is More Important Than Knowledge

Understanding imagination and knowledge.

Imagination and knowledge are both important. Knowledge is the collection of facts and information, while imagination helps us create new ideas.

Imagination’s Role

Imagination is crucial because it allows us to think beyond what we know. It helps us dream, invent, and solve problems.

Knowledge’s Limitations

Knowledge has limits. It’s confined to what we’ve learned and experienced. It doesn’t allow for new possibilities like imagination does.

While knowledge is important, imagination is more so. It leads us to new discoveries, innovations, and a better future.

250 Words Essay on Imagination Is More Important Than Knowledge

The supremacy of imagination.

Imagination is the driving force behind innovation and advancement. While knowledge is the accumulation of facts and data, imagination transcends the realm of the known, venturing into the universe of possibilities. Albert Einstein famously stated, “Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination encircles the world.”

Limitations of Knowledge

Knowledge, though vital, is inherently restrictive. It is confined to what is already known, discovered, or understood. Our knowledge is based on past experiences and learned information, which, although crucial, can limit our perspective to the existing reality.

Unleashing Potential with Imagination

Contrarily, imagination is boundless. It enables us to envision scenarios beyond the constraints of reality, paving the way for groundbreaking ideas and extraordinary innovations. Imagination fuels creativity, leading to advancements in diverse fields like technology, arts, and science.

The Interplay of Imagination and Knowledge

Despite their disparities, imagination and knowledge are not mutually exclusive. Knowledge serves as a foundation upon which imagination can build. It provides the raw materials that imagination can transform into novel concepts.

In conclusion, while knowledge equips us with the tools to understand and navigate the world, it is imagination that empowers us to reshape it. Emphasizing the importance of imagination doesn’t undermine the value of knowledge; instead, it encourages us to transcend the known and explore the realm of possibilities. Hence, imagination, with its ability to envision, innovate, and inspire, holds a higher pedestal than knowledge.

500 Words Essay on Imagination Is More Important Than Knowledge

The power of imagination.

Imagination is an integral part of human cognition, serving as a catalyst for creativity, innovation, and problem-solving. It is the mental faculty that allows us to transcend the confines of our immediate reality, enabling us to explore limitless possibilities. Albert Einstein once said, “Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution.”

Imagination Versus Knowledge

Knowledge is undoubtedly crucial. It is the accumulation of facts, information, and skills acquired through experience or education. It empowers us to understand the world around us, make informed decisions, and perform various tasks. However, knowledge is fundamentally limited to what is known and understood.

On the other hand, imagination is boundless. It is not confined to the realm of the known but ventures into the unknown, the unexplored, and the yet-to-be-invented. Imagination fuels innovation, pushing us to challenge the status quo and create something new. It is the driving force behind scientific discoveries, technological advancements, and artistic creations.

The Role of Imagination in Progress

Imagination plays a pivotal role in societal and technological progress. The greatest inventors, scientists, and artists were not just knowledgeable; they were imaginative. They dared to envision a different world and then used their knowledge to make it a reality.

Consider the example of the Wright Brothers. Their knowledge of physics and engineering was essential, but it was their imagination that enabled them to conceive the possibility of human flight. Similarly, Einstein’s theory of relativity was a product of his ‘thought experiments’ – a testament to the power of imagination in scientific discovery.

Imagination in Education

In the realm of education, imagination is equally crucial. It fosters curiosity, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills. It encourages students to approach problems from different perspectives, fostering innovative solutions.

While knowledge provides the foundation, imagination allows students to go beyond rote learning and engage in experiential and creative learning. It promotes a deeper understanding of concepts, facilitating the application of knowledge in real-world scenarios.

In conclusion, while knowledge is essential, it is imagination that truly propels us forward. It is the engine of progress, the catalyst for innovation, and the spark that ignites the flame of discovery. As we navigate an increasingly complex and rapidly changing world, imagination – the ability to envision new possibilities and create novel solutions – will be more important than ever. Thus, we should strive to cultivate not just knowledge but also a rich and vibrant imagination.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on A Little Knowledge Is a Dangerous Thing

- Essay on My Train Journey

- Essay on My Favourite Journey

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Albert Einstein: 'Imagination is more important than knowledge.'

Imagination is more important than knowledge.

Imagination is more important than knowledge. These profound words spoken by Albert Einstein encapsulate the essence of human creativity and the limitless possibilities that lie within our minds. At first glance, one might argue that knowledge is the backbone of progress and the fuel for innovation. After all, knowledge provides us with the foundation upon which we build new ideas and make scientific advancements. However, upon closer examination, it becomes apparent that imagination, with its transformative power and ability to transcend conventional boundaries, is what drives us to explore uncharted territories and make groundbreaking discoveries.Knowledge, although undeniably crucial, is inherently limited by the information that we acquire through education, experience, and observation. It serves as the framework that lays the groundwork for our understanding of the world. Without knowledge, we would be lost in a sea of ignorance, unable to comprehend the complex systems and principles that govern our reality. But it is through imagination that we break free from the confines of existing knowledge and venture into uncharted intellectual territory.Imagination is the catalyst for innovation and progress. It enables us to conceive of new ideas, envision things that do not yet exist, and challenge the status quo. Imagination is the driving force behind scientific breakthroughs, technological advancements, and artistic creations. It empowers us to ask "what if" questions and explore the possibilities that lie beyond the boundaries of what is currently known. Without imagination, our knowledge would remain stagnant, and we would be deprived of the marvels that have shaped our world.Now, let us introduce an unexpected philosophical concept to delve deeper into the dynamics between imagination and knowledge: reality. Reality, as we perceive it, is a product of both knowledge and imagination. Our understanding of the world is contingent upon the knowledge we possess, which allows us to interpret and make sense of our surroundings. Yet, it is through imagination that we can challenge the limitations of our current reality and envision alternate possibilities.Consider the concept of time travel, for instance. While our current understanding of the laws of physics may restrict the feasibility of this notion, it is through the power of imagination that we can explore the intricacies of time travel, speculate about its mechanisms, and even delve into the philosophical implications it would have on our existence. Imagination allows us to break free from the constraints of the known, inviting us to question, hypothesize, and push the boundaries of what is perceived as reality.In a sense, imagination is the bridge between what we know and what we aspire to discover. It serves as the creative medium through which knowledge can be expanded. It is the spark that ignites scientific curiosity, artistic expression, and human progress as a whole. Imagination encourages us to embrace unexpected connections, pursue unconventional paths, and challenge the rigidity of established paradigms.In conclusion, Albert Einstein's quote, "Imagination is more important than knowledge," prompts us to acknowledge the paramount role that imagination plays in shaping our world. While knowledge provides us with the foundation upon which progress is built, it is through imagination that we transcend the boundaries of existing knowledge and venture into the realm of possibility. Imagination ignites our curiosity, fuels our creativity, and pushes the boundaries of what we perceive as reality. Embracing our imaginative capacities is not only essential for personal growth and fulfillment but also critical for the advancement of societies as we continue to explore the infinite potential of the human mind.

Charles de Lint: 'I want to touch the heart of the world and make it smile.'

Jerzy kosinski: 'the principles of true art is not to portray, but to evoke.'.

March 20, 2010

Post Perspective

Albert Einstein: “Imagination Is More Important Than Knowledge”

Albert Einstein wants you to know that everything is NOT relative, America is a great country, and he might have been a happy, mediocre fiddler if he hadn't become a genius in physics.

Jeff Nilsson

- Share on Facebook (opens new window)

- Share on Twitter (opens new window)

- Share on Pinterest (opens new window)

Weekly Newsletter

The best of The Saturday Evening Post in your inbox!

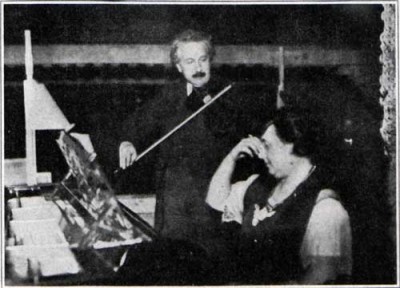

In this 1929 interview with a Post reporter, Albert Einstein discussed the role of relativity, why he thought nationalism was the “measles of mankind,” and how he might have become a happy, mediocre fiddler if he hadn’t become a genius in physics.

When a Post correspondent interviewed Albert Einstein about his thought process in 1929, Einstein did not speak of careful reasoning and calculations. Instead —

“I believe in intuitions and inspirations. I sometimes feel that I am right. I do not know that I am… [but] I would have been surprised if I had been wrong “I am enough of the artist to draw freely upon my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.”

Something else that was circling the globe in that year was Einstein’s reputation. At the time of this interview, his fame had spread across Europe and America. Everywhere he was acclaimed a genius for defining the principles of relativity, though very few people understood what they meant.

Subscribe and get unlimited access to our online magazine archive.

Imagination may have been essential to his breakthrough thinking, but Einstein’s discovery also rested on his vast knowledge of physical science. Knowledge and imagination let him see the relationship between space, time, and energy. Using mathematics, he developed a model for understanding how objects and light behave in extreme conditions — as in the subatomic world, where the old Newtonian principles didn’t appear to work.

Whenever Einstein explained his work to the popular press, though, reporters got lost in his talk of space-time continuum, absolute speed of light, and E=Δmc 2 . So they used their own imaginations to define relativity. One of their misinterpretations was the idea that relativity meant everything is relative. The old absolutes were gone. Nothing was certain anymore.

It was a ridiculous interpretation that could only have made sense if newspaper readers were no bigger than a proton, or could travel near the speed of light.

This misperception was so common that the Post writer used it to start his interview.

“Relativity! What word is more symbolic of the age? We have ceased to be positive of anything. We look upon all things in the light of relativity. Relativity has become the plaything of the parlor philosopher.”

Einstein, as always, patiently clarified his concept.

“‘The meaning of relativity has been widely misunderstood, Philosophers play with the word, like a child with a doll. Relativity, as I see it, merely denotes that certain physical and mechanical facts, which have been regarded as positive and permanent, are relative with regard to certain other facts in the sphere of physics and mechanics. It does not mean that everything in life is relative and that we have the right to turn the whole world mischievously topsy-turvy.'”

The world of the early 20th Century certainly felt like it was being inverted — with or without relativity. Even as Einstein was developing his theory about the space-time continuum and the nature of light, old Europe was dying in record numbers. Just a few weeks before Einstein released his general theory of relativity in 1916, the German Imperial Army began its assault at Verdun. In the ensuing, ten-month battle, France and Germany suffered 800,000 casualties. Four months later, the British launched their catastrophic attack at the Somme and suffered 58,000 casualties in a single day.

The survivors of these debacles were disillusioned by the waste of this war, and the peace that followed. The youth of Europe and America were looking for new truths. The old ones seemed empty and especially lethal to young men. They saw how noble sacrifice could be used for political ends. And they had seen how virtue and faith fared against massed machine guns.

This “Relativity” they read about seemed promising, if it meant that thousands wouldn’t have to die needlessly, of that could live beyond the limiting moral codes of their parents.

Einstein, himself, didn’t indulge in any of this relativism. He was a man of strong beliefs, not equivocations. For instance, his love of music was absolute.

“‘If… I were not a physicist, I would probably be a musician. I often think in music. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music. I cannot tell if I would have done any creative work of importance in music, but I do know that I get most joy in life out of my violin.'” “Einstein’s taste in music is severely classical. Even Wagner is to him no unalloyed feast of the ears. He adores Mozart and Bach. He even prefers their work to the architectural music of Beethoven.”

He disagreed with the traditional Jewish concept of free will.

“I am a determinist. As such, I do not believe in free will. The Jews believe in free will. They believe that man shapes his own life. I reject that doctrine philosophically. In that respect I am not a Jew… Practically, I am nevertheless, compelled to act as if freedom of the will existed. If I wish to live in a civilized community, I must act as if man is a responsible being.”

He never expressed any belief in a personal God, but he believed in the historical Jesus — not the popularized prophet such as appeared in a best-selling biography by Emil Ludwig.

“Ludwig’s Jesus,” Einstein replied, “is shallow. Jesus is too colossal for the pen of phrasemongers, however artful. No man can dispose of Christianity with a bon mot .” “You accept the historical existence of Jesus?” “Unquestionably. No one can read the Gospels without feeling the actual presence of Jesus. His personality pulsates in every word. No myth is filled with such life. How different, for instance, is the impression which we receive from an account of legendary heroes of antiquity like Theseus. Theseus and other heroes of his type lack the authentic vitality of Jesus.”

Einstein was no relativist on the subject of nationalism, which he saw grow violent and intolerant from his Berlin home.

“Nationalism is an infantile disease. It is the measles of mankind.”

It was different in the United States, he believed.

“Nationalism in the United States does not assume such disagreeable forms as in Europe. This may be due partly to the fact that your country is so immense, that you do not think in terms of narrow borders. It may be due to the fact that you do not suffer from the heritage of hatred or fear which poisons the relations of the nations of Europe.”

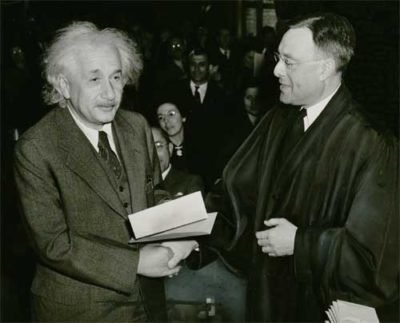

Three years later, Einstein fled Germany to seek asylum in the United States, where he became a citizen in 1940. (Not for the last time, America was enriched by the intolerance of other countries.)

It is interesting to see how Einstein viewed America three years before he made it his new home.

“In America, more than anywhere else, the individual is lost in the achievements of the many. America is beginning to be the world leader in scientific investigation. American scholarship is both patient and inspiring. The Americans show an unselfish devotion to science, which is the very opposite of the conventional European view of your countrymen.

“Too many of us look upon Americans as dollar chasers. This is a cruel libel, even if it is reiterated thoughtlessly by the Americans themselves. It is not true that the dollar is an American fetish. The American student is not interested in dollars, not even in success as such, but in his task, the object of the search. It is his painstaking application to the study of the infinitely little and infinitely large.”

The only criticism Einstein could find for America was its emphasis on homogenizing its citizens into a single type.

“Standardization robs life of its spice. To deprive every ethnic group of its special traditions is to convert the world into a huge Ford plant. I believe in standardizing automobiles. I do not believe in standardizing human beings. Standardization is a great peril which threatens American culture.”

Read “What Life Means to Einstein,” by George Sylvester Viereck. Published October 26, 1929 [PDF].

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Recommended

Mar 11, 2024

American Life , History , Post Perspective

Do Beautiful People Get Away with Murder?

Sep 25, 2023

History , Post Perspective , Travel

Blimps, Dirigibles, and Zeppelins: You Can’t Keep a Good Idea Down

Jul 06, 2023

History , Post Perspective

No Offense: How Americans Became Intolerant of Body Odor

Albert Einstein= AE Elon Musk= EM E=Δmc2 Thus: AE=EM

I can be updated with any new informations regarding Albert Einstein discovery about Physics

Without imagination, there would be no knowledge. If imagination didn’t exist, the computar wouldn’t exist. None of Alberts’ creations would exist. The lightbuld wouldn’t exist, NOTHING would exist. If there was no imagination, everybody would the same, there would be no such thing an opinion. Life would be boring. That’s just the final truth. Goodbye.

Is imagination no longer relative to science?

Just check out the major U.S. search engines (Google, Yahoo, Bing, Ask) for the search term: A concept of space and time You will find the same imagination-based essay at the TOP of each list of many millions of web sites.

Strangely, reference to this same concept has yet been hard to find in any scientific journal. What happened to imagination?

Albert Einstein did theorize Relativity as a fact. And it should come as no surprise That humans seek by thought and act To make the concept fit the way That each one imagines as true. And so the term gets lots of play As all the many think and do, And play with truth as though a toy. In time and space he occupied, What in his life was greatest joy? To which Dr. Einstein replied,

“My sweetest relativity -” “Making music with Mrs. E.”

Not sure what the inclusion of “d” represents regarding Einstein’s mathematical expression of energy’s relationship to matter. The revised formula sounds a lot like a new rap group. Acceptance of the reality of Relativity does not foster moral ambiguity–unless, of course, you believe a hammer is the same thing as a guiding principle. This is one of Nilsson’s better articles–though I’ve always liked all things Einstein. Had a grandfather who resembled the humble genius quite closely.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Imagination Is More Important Than Knowledge

- Essays, Outlines

- Aug 23, 2023

- Noshin Bashir

The statement “Imagination is more important than knowledge” is attributed to Albert Einstein. This reflects the role of creativity and imaginative thinking in the pursuit of understanding and innovation. It is the human imagination that derives innovation, instills creativity, generates hypotheses and theories, and evolves understanding skills.

It is not knowledge but imagination that sparks curiosity, driving scientists to ask questions and explore new areas of research. The statement emphasizes that it’s the ability to think creatively and imagine new scenarios that propel human beings forward in understanding and progress.

To commence, the quote suggests that imagination plays a crucial role in driving innovation and progress. While knowledge provides a foundation, it’s the ability to imagine new possibilities, connections, and solutions that lead to breakthroughs.

Take the example of the invention of smartphones that revolutionized the fields of communication and information. Combining features like a phone, camera, music player, and internet browser into a single device was an imaginative leap that transformed into reality. Also, 3D printing technology that allows for the creation of physical objects from digital designs is yet another creation from an imaginative thought process. This innovation has revolutionized manufacturing.

In addition to that, imagination has the power to transcend existing knowledge and boundaries. It allows individuals to explore ideas and concepts that might not yet be supported by established facts or theories.

Imagination enables creative problem-solving. When faced with challenges, people who can imagine alternative approaches are often better equipped to find unique solutions that may not be immediately apparent through factual knowledge alone. Imagination can help you grasp concepts like rhythm, harmonics, and scales, enhancing your understanding of both math and music.

Apart from that, imagination can inspire a thirst for knowledge. When individuals can envision the possibilities that expanding their knowledge might open up, they are more motivated to learn and explore.

Lastly, scientific discoveries often begin with imaginative ideas about how things might work. Imagination is the driving force behind forming these hypotheses and then testing them through experimentation and observation. Imagination is the driving force behind scientific exploration and innovation.

It encourages scientists to think beyond the known and imagine possibilities that challenge conventional wisdom, resulting in the advancement of human understanding and the improvement of our world. It is the power of imagination that encourages scientists to draw upon knowledge from different fields, fostering interdisciplinary insights and collaborations. Moreover, imagination sparks curiosity, driving scientists to ask questions and explore new areas of research.

In essence, imagination is by far more important than knowledge because without imagination there would be nothing like curiosity, innovation, future predictions, and thoughtful experiments. Someone has rightly said that imagination is the eye of the soul. It is the beginning of creation.

Read Also: The One Who Uses Force Is Afraid Of Reasoning

Share This Post:

Related posts.

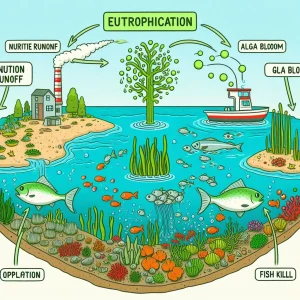

What is Eutrophication?

Indus River

Education System in Pakistan

Matric paper of english bise sargodha, recent posts.

![imagination is more important than knowledge essay outline Artificial Intelligence [AI]](https://globaleak.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Artificial-Intelligence-AI-300x300.webp)

Advantages and Disadvantages of Artificial Intelligence [AI]

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Quote Investigator®

Tracing Quotations

Imagination Is More Important Than Knowledge

Albert Einstein? Apocryphal?

Dear Quote Investigator: Many websites credit Albert Einstein with this statement:

Imagination is more important than knowledge.

I am skeptical. Are these the words of Einstein?

Quote Investigator: This remark apparently was made by Einstein during an interview that was published in “The Saturday Evening Post” in 1929. Here is an excerpt showing the context of his comment. The first paragraph below records Einstein’s words; the next sentence is the interviewer speaking; the final paragraph is Einstein speaking again. Boldface has been added to the following passage and some excerpts further below: [1] 1929 October 26, The Saturday Evening Post, What Life Means to Einstein: An Interview by George Sylvester Viereck, Start Page 17, Quote Page 117, Column 1, Saturday Evening Post Society, … Continue reading

“I believe in intuitions and inspirations. I sometimes feel that I am right. I do not know that I am. When two expeditions of scientists, financed by the Royal Academy, went forth to test my theory of relativity, I was convinced that their conclusions would tally with my hypothesis. I was not surprised when the eclipse of May 29, 1919, confirmed my intuitions. I would have been surprised if I had been wrong.” “Then you trust more to your imagination than to your knowledge?” “I am enough of the artist to draw freely upon my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.”

Here are additional selected citations in chronological order.

In 1931 the book “Cosmic Religion and Other Opinions and Aphorisms” by Albert Einstein was published. This volume contained the same saying, but the surrounding text was phrased somewhat differently: [2] 2009, “Einstein on Cosmic Religion and Other Opinions and Aphorisms” by Albert Einstein, Quote Page 97, Dover Publication, Mineola, New York. (This Dover edition is an unabridged … Continue reading

At times I feel certain I am right while not knowing the reason. When the eclipse of 1919 confirmed my intuition, I was not in the least surprised. In fact, I would have been astonished had it turned out otherwise. Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution. It is, strictly speaking, a real factor in scientific research.

The New York Times reviewed “Cosmic Religion” in March 1931 and the statement about imagination was memorable enough that it was reprinted in the review: [3] 1931 March 8, New York Times, Opinions and Aphorisms of Albert Einstein, Quote Page 66, (Book review of “Cosmic Religion: With Other Opinions and Aphorisms” by Albert Einstein), New York. … Continue reading

He frankly admits that he believes “in intuition and inspiration,” and adds: “At times I feel certain I am right without knowing the reason,” and he declares that “imagination is more important than knowledge.”

In conclusion, evidence indicates that the quotation is accurate, and it appeared in an interview of Albert Einstein conducted by George Sylvester Viereck in 1929.

Economic Sociology & Political Economy

The global community of academics, practitioners, and activists – led by dr. oleg komlik, albert einstein on the power of ideas and imagination in science.

“In nearly every detective novel since the admirable stories of Conan Doyle there comes a time when the investigator has collected all the facts he needs for at least some phase of his problem. These facts often seem quite strange, incoherent, and wholly unrelated. The great detective, however, realizes that no further investigation is needed at the moment, and that only pure thinking will lead to a correlation of the facts collected. So he plays his violin, or lounges in his armchair enjoying a pipe, when suddenly, by Jove, he has it! Not only does he have an explanation for the clues at hand but he knows that certain other events must have happened. Since he now knows exactly where to look for it, he may go out, if he likes, to collect further confirmation for his theory (pp. 4-5)… It is a familiar fact to readers of detective fiction that a false clue muddles the story and postpones the solution (6)… Intuitive conclusions based on immediate observation are not always to be trusted, for they sometimes lead to the wrong clues. But where does intuition go wrong? (7)… In a good mystery story the most obvious clues often lead to the wrong suspects… the most obvious intuitive explanation is often the wrong one (9)… Science must create its own language, its own concepts, for its own use . Scientific concepts often begin with those used in ordinary language for the affairs, of everyday life, but they develop quite differently. They are transformed and lose the ambiguity associated with them in ordinary language, gaining in rigorousness so that they may be applied to scientific thought (14)… Our interest here lies in the first stages of development, in following initial clues, in showing how new… concepts are born in the painful struggle with old ideas. We are concerned only with pioneer work in science, which consists of finding new and unexpected paths of development; with the adventures in scientific thought which create an ever-changing picture of the universe. The initial and fundamental steps are always of a revolutionary character. Scientific imagination finds old concepts too confining, and replaces them by new ones. The continued development along any line already initiated is more in the nature of evolution, until the next turning point is reached when a still newer field must be conquered. In order to understand, however, what reasons and what difficulties force a change in important concepts, we must know not only the initial clues, but also the conclusions which can be drawn (28)… Most of the fundamental ideas of science are essentially simple, and may, as a rule, be expressed in a language comprehensible to everyone. To follow up these ideas demands the knowledge of a highly refined technique of investigation (29)… Nearly every great advance in science arises from a crisis in the old theory, through an endeavour to find a way out of the difficulties created. We must examine old ideas, old theories, although they belong to the past, for this is the only way to understand the importance of the new ones and the extent of their validity. In the first pages of our book we compared the role of an investigator to that of a detective who, after gathering the requisite facts, finds the right solution by pure thinking. In one essential this comparison must be regarded as highly superficial. Both in life and in detective novels the crime is given. The detective must look for letters, fingerprints, bullets, guns, but at least he knows that a murder has been committed. This is not so for a scientist…. For the detective the crime is given, the problem formulated: who killed Cock Robin? The scientist must, at least in part, commit his own crime, as well as carry out the investigation. Moreover, his task is not to explain just one case, but all phenomena which have happened or may still happen (77-8)… Yet we may choose to be conservative and seek a solution [to a result that shakes our belief] within the frame of old ideas. Difficulties of this kind, sudden and unexpected obstacles in the triumphant development of a theory, arise frequently in science. Sometimes a simple generalization of the old ideas seems, at least temporarily, to be a good way out… Very often, however, it is impossible to patch up an old theory, and the difficulties result in its downfall and the rise of a new one (93-4)… The formulation of a problem is often more essential than its solution , which may be merely a matter of… experimental skill. To raise new questions, new possibilities, to regard old problems from a new angle, requires creative imagination and marks real advance in science (95)… Creating a new theory is not like destroying an old barn and erecting a sky scraper in its place. It is rather like climbing a mountain, gaining new and wider views, discovering new connections between our starting point and its rich environment. But the point from which we started still exists and can be seen, although it appears smaller and forms a tiny part of our broad view gained by the mastery of the obstacles on our way up (159)… Science forces us to create new ideas, new theories. Their aim is to break down the wall of contradictions which frequently blocks the way of scientific progress. All the essential ideas in science were born in a dramatic conflict between reality and our attempts at understanding. Here again is a problem for the solution of which new principles are needed (280)… The association of solved problems with those unsolved may throw new light on our difficulties by suggesting new ideas. It is easy to find a superficial analogy which really expresses nothing. But to discover some essential common features, hidden beneath a surface of external differences, to form, on this basis, a new successful theory, is important creative work ” ( Einstein and Infeld 1938: 286-7 ).

*** Join the Economic Sociology and Political Economy community through Facebook / Twitter / LinkedIn / Google+ / Reddit / Tumblr

Share this:

12 comments.

Very interesting topic, from my earlier years of teaching at Universities I was familiar with Albert Einstein’s writings not precisely about physics but many articles in contemporary subjects related to the human thinking, social, political or cultural. His brilliant mind was obviously open to a variety of social or historical contemporary problems of his own time. In my understanding he as scientific did not isolated his own system of though or his dialectical methodology to analysed the human society, ethics and even politics. There is a concatenation in Einstein thinking of the Universo phenomena in which he can be an isolated investigator of the realities, social, physic or natural. Theory then is a system of thought like “…a house which, right after being built and decorated, requieres of its upkeep an effort more or less vigorous but assiduous (depending of the negative effects of the elements). At a certain point in time it is not worth to continuing repairing, and we must take the decision to demolished and started it from cero. In the system of thought then perpetually new house is perpetually maintained by the old one which almost through a feat of magic, persist in the new. In conclusion: mankind system of thinking is as one philosopher approached is a subsequent and unlimited attempts to demolish those truths that are understood implicitly. white others need to be reconsidered and integrated.

it is an outstanding theory.

[…] silent hour of your night: must I write?” // Probably the best “Acknowledgments” ever // Albert Einstein on the power of ideas and imagination in science // The Art of Writing // Overly honest reference: “Should we cite the crappy Gabor paper […]

[…] also: Probably the best “Acknowledgments” ever // Albert Einstein on the power of ideas and imagination in science // The Art of Writing // Academic CV of Failures – a motivational lesson // Theodor Adorno […]

[…] > Albert Einstein on the Power of Ideas and Imagination in Science […]

[…] > Albert Einstein on the power of ideas and imagination in science […]

[…] Albert Einstein on the Power of Ideas and Imagination in Science (by Oleg Komlik, January 8, […]

[…] that the success of the solutions to all the problems is imagination. He put forward various amazing theories just based on his imagination. He clarified the most misunderstood thing, space, and our […]

[…] Albert Einstein on the power of ideas and imagination in science, Economics Sociology & Political Economy, […]

[…] [1] Komlik, Oleg, “Albert Einstein on the Power of Ideas and Imagination in Science”, Economic Sociology (8 Januari 2016), https://economicsociology.org/2016/01/08/albert-einstein-on-the-power-of-ideas-and-imagination-in-sc… ;. […]

[…] — Albert Einstein on the Power of Ideas and Imagination in Science (by Oleg Komlik, January 8, 2016) […]

[…] Einstein: “Imagination is more important than knowledge.” This article from the Economic Sociology & Political Economy website illustrates Einstein’s “take” on the power of ideas and imagination in […]

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Discover more from economic sociology & political economy.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Share on twitter

- Share on facebook

Is imagination more important than knowledge? Einstein

- Share on linkedin

- Share on mail

Berlin, 1929. The poet and journalist George Sylvester Viereck has charmed an interview out of an initially reluctant superstar physicist¹. He asks: "How do you account for your discoveries? Through intuition or inspiration?" Albert Einstein replies:

"Both. I sometimes feel I am right, but do not know it. When two expeditions of scientists went to test my theory I was convinced they would confirm my theory. I wasn't surprised when the results confirmed my intuition, but I would have been surprised had I been wrong. I'm enough of an artist to draw freely on my imagination, which I think is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world."

Knowledge versus imagination. Einstein's aphorism reflects a recurrent theme in human thought. The ancient dichotomy between what we know and what we dream, intuit or sense by instinct is found, in some form, in every field of human intellectual endeavour. It is seen in the contrast between rationalist and mystic interpretations of the world's great religions, between realism and surrealism in the visual arts and between the brutal number-crunching of much experimental physics and the feathery abstractions of superstring and membrane theory.

Artists, geniuses and other rebellious spirits have often claimed imagination as their territory. Knowledge, that dull conviction resulting from a brush with reality, is black-and-white, logical, stable, conservative – the domain of curators and accountants. Your view of which is more important will depend on your personality. The relevant distinction was best captured not by a psychology text but by a history book (of sorts): in their discussion of the English Civil War, Sellars and Yeatman famously described the Cavaliers as "wrong but wromantic" and the Roundheads as "right and repulsive". Who'd be a Roundhead? Who won the Civil War?

Like many dichotomies, this one is an oversimplification. We know that the brilliance of many great artists was grounded in years of hard training; we know some excitingly imaginative museums and some highly creative accountants. Throughout our development as a species we have relied on a blend of imagination and knowledge. Both are valuable. What then is the relationship between them?

Metaphors are plentiful. Knowledge is a stepping stone to imagination; it stands to imagination as honeycomb does to honey; knowledge and imagination are enemies, or independent strands in the web of our mental lives. The Oxford English Dictionary states that imagination involves "forming a mental concept of what is not actually present to the senses". But the full flavour of Einstein's aphorism eludes this definition. I can form a mental concept of what I ate at last week's dinner party, though it is no longer present to any of my senses (even those rarely-discussed but useful ones which signal the state of my bowels). Imagination is something more than memory, something novel: adding a movie star or picturing the guests without their clothes.

Knowledge concerns itself with what is present to the senses, but is also a stored and shared repository of publicly acceptable thoughts, many frozen into physical symbols (written or spoken), transmitted through time and space. Knowledge coded, stored and expressed using symbols can, because of the entrancing flexibility of symbol systems, be broken up and reassembled in a multitude of novel combinations. It is this act of recombination which underlies the power to imagine. Our imagination is and must be grounded in our knowledge. The more memories we accumulate, the more material we have to work with, the richer and stranger are the fruits of our imagination.

Imagination, however, is not just the recombination of stored experiences. Such recombination happens every night even in organisms blessed with much less cortex than human beings. What distinguishes us is our capacity for controlled and wakeful dreaming. This is a useful survival aid, helping us to solve problems, anticipate challenges and conceive alternatives. But we have turned imagination into much more – a good in itself. Like money, sex or drugs, we use it to satisfy our needs, flaunt our wealth and status, tighten our social bonds, or distract us from realities we would rather avoid.

The comparison with drugs implies the risk of addiction, and indeed, our urge to imagine, and to consume the products of other people's imagination, can sometimes become extreme. Reality can be a bleak place, especially for those who lack the essential antidote: love. When depression sets in, an individual may lose the strength to use imagination to counteract the automatic, overwhelmingly negative thoughts characteristic of the condition. The products of others' imaginations provide an alternative.

A best-selling page-turner or fast-paced movie thriller draws us into another world. These fake worlds, from the fantasy of Harry Potter to the horror of Hannibal Lecter, have two ingredients in common which make them attractive to millions. Firstly, they provide an opportunity for "losing" oneself in an absorption where consciousness of self-as-independent-entity disappears: a sweet, safe, temporary death. Secondly, they deny Darwin, confirming Eliot's view that "humankind cannot bear too much reality". In a fake world the hero or heroine is special and recognised as such by others. An uncaring universe cannot destroy them, indeed, they are at its centre; if they die the fake world dies with them. Voldemort focuses on attacking Harry Potter, Lecter on tantalising yet protecting his adversary Clarice Starling. Identifying with a person who interests such potent beings does no harm to the self-esteem. In some individuals such cognitive massage can become an obsession in a world where the public ideal is super-confidence.

Here again we see the complementarity of imagination and knowledge. At both group and individual levels, knowledge facilitates community and continuity, while imagination facilitates change. Knowledge binds us to a sometimes-oppressive existence; imagination helps us escape it. However, imagination evolved as a tool for facilitating survival. Imagining, we take a step beyond what we know into the future or into another world. We see alternatives and possibilities; we work out what we need to reach our goals. Unhooked from reality, imagination no longer serves these life-enhancing purposes. Without new knowledge to feed it and keep it in check, it can become sterile and even dangerous: in Hume's words, "nothing but sophistry and illusion".

Another measurable way of thinking about the balance between imagination and knowledge (the "I/K ratio") is to consider each as private or public, individual or group. Wittgenstein famously argued that language is essentially public, requiring consensus about the use of its symbols in order to maintain consistency in meaning over time. One might say the same about knowledge: it must derive from experience in a way which can in principle be reproduced by others. Imagination is a private thing, the leap of a single brain from established fact to exciting novelty.

Again the dichotomy is too simplistic. Knowledge strengthens group bonding, but the emergence of new knowledge in, for example, the sciences can threaten a group's very existence. Imagination can challenge rules and traditions by putting information together in novel ways; yet shared acts of imagination can also help to strengthen intra-group bonds. Try daydreaming: generate for yourself a coherent story of your own invention, follow it through from beginning to end. Unless you are a professional storyteller you will probably find it extremely difficult to avoid drifting into other thoughts or even falling asleep. We think of ourselves as the only species capable of controlled dreaming, but in fact it is hard to keep control unless we make our dreams public. The greatest acts of imagination – from Bach's Cello Suites or Milan Cathedral to Star Wars or Günther van Hagen's Bodyworlds – require not only creation but admiration: they depend for their impact on being heard, seen and understood within a cultural context built up over hundreds of years by thousands of people.

Was Einstein right? Is imagination more important than knowledge? As our realities become more complex we seem increasingly to prefer imagination, but that preference is culture-dependent. Imagination flourishes when its products are highly valued. Leisure, wealth and a degree of political stability are prerequisites for the freedom essential to creativity and for the use of artistic products as indicators of social status.

When a society feels under threat, shared knowledge, exalted as "culture" or "tradition", may be valued more, lowering the I/K ratio. Resources previously dedicated to artistic creativity may be diverted into attempts to protect the society or to acquire knowledge about the changes it is experiencing, leading to reduced artistic output. Art in Renaissance Florence provides an example. Between the Milanese siege of 1401-2 and the French invasion in 1494 a period of relative political stability was the context for some of the greatest paintings and sculptures of the Renaissance. In the chaos of the early 16th century, as power fluctuated between Medici and republican governments, comparatively little great art was produced. Political theory, however, blossomed, notably with the publication of Machiavelli's The Prince and Discourses .

That the I/K ratio is culture-dependent is surely unsurprising. Even within a single society, the preferred I/K ratio in any given field of intellectual activity will depend on the field in question and on the person making the assessment.

This brings us to another aspect of the complementarity between knowledge and imagination: its dynamic nature. The I/K ratio changes over time. In some cases, a new branch of the sciences, for example, can begin with a few mavericks (high I/K ratio) whose research is initially dismissed as speculative. As their way of thinking gradually wins acceptance, it attracts recruits at an increasing rate until a paradigm shift occurs and allegiances transfer wholesale from the old establishment to the new. A period of growing stability follows in which knowledge is assembled (decreasing I/K ratio) which supports the new ideas. Creative output falls, stagnation gradually sets in. Problems begin to emerge, which are ignored by all but a few ... and so the cycle begins again.

As for science, so for religion. Cults often start with an act of radical imagining, what Anthony Wallace calls a "mazeway resynthesis": elements of current cultural understanding (the "mazeway") are recombined into a new and dramatic form which seems to promise solutions to previously insoluble problems. Yet cult doctrines, born in the fiery freedom of imagination, tend to solidify into the restriction of dogma, leading to the rejection of any information which does not fit. As social psychologists have noted, however, the pattern of growth, stability and attrition seems to be a fundamental one for human groups across many different fields of endeavour.

So is imagination more important than knowledge? It depends on whom you ask, what you ask about, and when.

Kathleen Taylor is a research scientist in the department of physiology at Oxford University. This essay won the THES /Palgrave Humanities and Social Sciences Writing Prize.

¹ The interview was published in the Philadelphia Saturday Evening Post , October 26th, 1929.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login

Reader's comments (2)

Featured jobs.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Imagination

To imagine is to represent without aiming at things as they actually, presently, and subjectively are. One can use imagination to represent possibilities other than the actual, to represent times other than the present, and to represent perspectives other than one’s own. Unlike perceiving and believing, imagining something does not require one to consider that something to be the case. Unlike desiring or anticipating, imagining something does not require one to wish or expect that something to be the case.

Imagination is involved in a wide variety of human activities, and has been explored from a wide range of philosophical perspectives. Philosophers of mind have examined imagination’s role in mindreading and in pretense. Philosophical aestheticians have examined imagination’s role in creating and in engaging with different types of artworks. Epistemologists have examined imagination’s role in theoretical thought experiments and in practical decision-making. Philosophers of language have examined imagination’s role in irony and metaphor.

Because of the breadth of the topic, this entry focuses exclusively on contemporary discussions of imagination in the Anglo-American philosophical tradition. For an overview of historical discussions of imagination, see the sections on pre-twentieth century and early twentieth century accounts of entry on mental imagery ; for notable historical accounts of imagination, see corresponding entries on Aristotle , Thomas Hobbes , David Hume , Immanuel Kant , and Gilbert Ryle ; for a more detailed and comprehensive historical survey, see Brann 1991; and for a sophisticated and wide-ranging discussion of imagination in the phenomenological tradition, see Casey 2000.

1.1 Varieties of Imagination

1.2 taxonomies of imagination, 1.3 norms of imagination, 2.1 imagination and belief, 2.2 imagination and desire, 2.3 imagination, imagery, and perception, 2.4 imagination and memory, 2.5 imagination and supposition, 3.1 mindreading, 3.2 pretense, 3.3 psychopathology.

- Supplement: Puzzles and Paradoxes of Imagination and the Arts

3.5 Creativity

3.6 knowledge, 3.7 figurative language, other internet resources, related entries, 1. the nature of imagination.

A variety of roles have been attributed to imagination across various domains of human understanding and activity ( section 3 ). Not surprisingly, it is doubtful that there is one component of the mind that can satisfy all the various roles attributed to imagination (Kind 2013). Nevertheless, perhaps guided by these roles, philosophers have attempted to clarify the nature of imagination in three ways. First, philosophers have tried to disambiguate different senses of the term “imagination” and, in some cases, point to some core commonalities amongst the different disambiguations ( section 1.1 ). Second, philosophers have given partial taxonomies to distinguish different types of imaginings ( section 1.2 ). Third, philosophers have located norms that govern paradigmatic imaginative episodes ( section 1.3 ).

There is a general consensus among those who work on the topic that the term “ imagination ” is used too broadly to permit simple taxonomy. Indeed, it is common for overviews to begin with an invocation of P.F. Strawson’s remarks in “Imagination and Perception”, where he writes:

The uses, and applications, of the terms “image”, “imagine”, “imagination”, and so forth make up a very diverse and scattered family. Even this image of a family seems too definite. It would be a matter of more than difficulty to identify and list the family’s members, let alone their relations of parenthood and cousinhood. (Strawson 1970: 31)

These taxonomic challenges carry over into attempts at characterization. In the opening chapter of Mimesis as Make-Believe —perhaps the most influential contemporary monograph on imagination—Kendall Walton throws up his hands at the prospect of delineating the notion precisely. After enumerating and distinguishing a number of paradigmatic instances of imagining, he asks:

What is it to imagine? We have examined a number of dimensions along which imaginings can vary; shouldn’t we now spell out what they have in common?—Yes, if we can. But I can’t. (Walton 1990: 19)

Leslie Stevenson (2003: 238) makes arguably the only recent attempt at a somewhat comprehensive inventory of the term’s uses, covering twelve of “the most influential conceptions of imagination” that can be found in recent discussions in “philosophy of mind, aesthetics, ethics, poetry and … religion”.

To describe the varieties of imaginings, philosophers have given partial and overlapping taxonomies.

Some taxonomies are merely descriptive, and they tend to be less controversial. For example, Kendall Walton (1990) distinguishes between spontaneous and deliberate imagining (acts of imagination that occur with or without the one’s conscious direction); between occurrent and nonoccurrent imaginings (acts of imagination that do or do not occupy the one’s explicit attention); and between social and solitary imaginings (episodes of imagining that occur with or without the joint participation of several persons).

One notable descriptive taxonomy concerns imagining from the inside versus from the outside (Williams 1973; Wollheim 1973; see Ninan 2016 for an overview). To imagine from the outside that one is Napoleon involves imagining a scenario in which one is Napoleon. To imagine from the inside that one is Napoleon involves that plus something else: namely, that one is occupying the perspective of Napoleon. Imagining from the inside is essentially first-personal, imagining from the outside is not. This distinction between two modes of imagining is especially notable for its implications for thought experiments about the metaphysics of personal identity (Nichols 2008; Ninan 2009; Williams 1973).

Some taxonomies aim to be more systematic—to carve imaginings at their joints, so to speak—and they, as one might expect, tend to be more controversial.

Gregory Currie and Ian Ravenscroft (2002) distinguishes creative imagination (combining ideas in unexpected and unconventional ways); sensory imagination (perception-like experiences in the absence of appropriate stimuli); and what they call recreative imagination (an ability to experience or think about the world from a perspective different from the one that experience presents). Neil Van Leeuwen (2013, 2014) takes a similar approach to delineate three common uses of “imagination” and cognate terms. First, these terms can be used to refer to constructive imagining , which concerns the process of generating mental representations. Second, these terms can be used to refer to attitude imagining , which concerns the propositional attitude one takes toward mental representations. Third, these terms can be used to refer to imagistic imagining , which concerns the perception-like format of mental representations.

Amy Kind and Peter Kung (2016b) pose the puzzle of imaginative use—on the seeming irreconcilability between the transcendent uses of imagination, which enables one to escape from or look beyond the world as it is, and the instructive uses of imagination, which enables one to learn about the world as it is. Kind and Kung ultimately resolve the puzzle by arguing that the same attitude can be put to these seemingly disparate uses because the two uses differ not in kind, but in degree—specifically, the degree of constraint on imaginings.

Finally, varieties of imagination might be classified in terms of their structure and content. Consider the following three types of imaginings, each illustrated with an example. When one imagines propositionally , one represents to oneself that something is the case. So, for example, Juliet might imagine that Romeo is by her side . To imagine in this sense is to stand in some mental relation to a particular proposition (see the entry on propositional attitude reports ). When one imagines objectually , one represents to oneself a real or make-believe entity or situation (Yablo 1993; see also Martin 2002; Noordhof 2002; O’Shaughnessy 2000). So, for example, Prospero might imagine an acorn or a nymph or the city of Naples or a wedding feast . To imagine in this sense is to stand in some mental relation to a representation of an (imaginary or real) entity or state of affairs. When one imagines X-ing , one simulatively represents to oneself some sort of activity or experience (Walton 1990). So, for example, Ophelia might imagine seeing Hamlet or getting herself to a nunnery . To imagine in this sense is to stand in a first-personal mental relation to some (imaginary or real) behavior or perception.

There are general norms that govern operations of imagination (Gendler 2003).

Mirroring is manifest to the extent that features of the imaginary situation that have not been explicitly stipulated are derivable via features of their real-world analogues, or, more generally, to the extent that imaginative content is taken to be governed by the same sorts of restrictions that govern believed content. For example, in a widely-discussed experiment conducted by Alan Leslie (1994), children are asked to engage in an imaginary tea party. When an experimenter tips and “spills” one of the (empty) teacups, children consider the non-tipped cup to be “full” (in the context of the pretense) and the tipped cup to be “empty” (both within and outside of the context of the pretense). In fact, both make-believe games and more complicated engagements with the arts are governed by principles of generation , according to which prompts or props prescribe particular imaginings (Walton 1990).

Quarantining is manifest to the extent that events within the imagined or pretended episode are taken to have effects only within a relevantly circumscribed domain. So, for example, the child engaging in the make-believe tea party does not expect that “spilling” (imaginary) “tea” will result in the table really being wet, nor does a person who imagines winning the lottery expect that when she visits the ATM, her bank account will contain a million dollars. More generally, quarantining is manifest to the extent that proto-beliefs and proto-attitudes concerning the imagined state of affairs are not treated as beliefs and attitudes relevant to guiding action in the actual world.

Although imaginative episodes are generally governed by mirroring and quarantining, both may be violated in systematic ways.

Mirroring gives way to disparity as a result of the ways in which (the treatment of) imaginary content may differ from (that of) believed content. Imagined content may be incomplete (for example, there may be no fact of the matter (in the pretense) just how much tea has spilled on the table) or incoherent (for example, it might be that the toaster serves (in the pretense) as a logical-truth inverter). And content that is imagined may give rise to discrepant responses , most strikingly in cases of discrepant affect—where, for example, the imminent destruction of all human life is treated as amusing rather than terrifying.

Quarantining gives way to contagion when imagined content ends up playing a direct role in actual attitudes and behavior (see also Gendler 2008a, 2008b). This is common in cases of affective transmission , where an emotional response generated by an imagined situation may constrain subsequent behavior. For example, imagining something fearful (such as a tiger in the kitchen) may give rise to actual hesitation (such as reluctance to enter the room). And it also occurs in cases of cognitive transmission , where imagined content is thereby “primed” and rendered more accessible in ways that go on to shape subsequent perception and experience. For example, imagining some object (such as a sheep) may make one more likely to “perceive” such objects in one’s environment (such as mistaking a rock for a ram).

2. Imagination in Cognitive Architecture

One way to make sense of the nature of imagination is by drawing distinctions, giving taxonomies, and elucidating governing norms ( section 1 ). Another, arguably more prominent, way to make sense of the nature is by figuring out, in a broadly functionalist framework, how it fits in with more well-understood mental entities from folk psychology and scientific psychology (see the entry on functionalism ).

There are two related tasks involved. First, philosophers have used other mental entities to define imagination by contradistinction (but see Wiltsher forthcoming for a critique of this approach). To give an oversimplified example, many philosophers hold that imagining is like believing except that it does not directly motivate actions. Second, philosophers have used other mental entities to understand the inputs and outputs of imagination. To give an oversimplified example, many philosophers hold that imagination does not output to action-generating systems.

Amongst the most widely-discussed mental entities in contemporary discussions of imagination are belief ( section 2.1 ), desire ( section 2.2 ), mental imagery ( section 2.3 ), memory ( section 2.4 ), and supposition ( section 2.5 ). The resolution of these debates ultimately rest on the extent to which the imaginative attitude(s) posited can fulfill the roles ascribed to imagination from various domains of human understanding and activity ( section 3 ).

To believe is to take something to be the case or regard it as true (see the entry on belief ). When one says something like “the liar believes that his pants are on fire”, one attributes to the subject (the liar) an attitude (belief) towards a proposition (his pants are on fire). Likewise, when one says something like “the liar imagines that his pants are on fire”, one attributes to the subject (the liar) an attitude (imagination) towards a proposition (his pants are on fire). The similarities and differences between the belief attribution and the imagination attribution point to similarities and differences between imagining and believing.

Imagining and believing are both cognitive attitudes that are representational. They take on the same kind of content: representations that stand in inferential relationship with one another. On the single code hypothesis , it is the sameness of the representational format that grounds functional similarities between imagining and believing (Nichols & Stich 2000, 2003; Nichols 2004a). As for their differences, there are two main options for distinguishing imagining and believing (Sinhababu 2016).

The first option characterizes their difference in normative terms. While belief aims at truth, imagination does not (Humberstone 1992; Shah & Velleman 2005). If the liar did not regard it as true that his pants are on fire, then it seems that he cannot really believe that his pants are on fire. By contrast, even if the liar did not regard it as true that his pants are on fire, he can still imagine that his pants are on fire. While the norm of truth is constitutive of the attitude of belief, it is not constitutive of the attitude of imagination. In dissent, Neil Sinhababu (2013) argues that the norm of truth is neither sufficient nor necessary for distinguishing imagining and believing.

The second option characterizes their difference in functional terms. One purported functional difference between imagination and belief concerns their characteristic connection to actions. If the liar truly believes that his pants are on fire, he will typically attempt to put out the fire by, say, pouring water on himself. By contrast, if the liar merely imagines that his pants are on fire, he will typically do no such thing. While belief outputs to action-generation system, imagination does not (Nichols & Stich 2000, 2003). David Velleman (2000) and Tyler Doggett and Andy Egan (2007) point to particular pretense behaviors to challenge this way of distinguishing imagining and believing. Velleman argues that a belief-desire explanation of children’s pretense behaviors makes children “depressingly unchildlike”. Doggett and Egan argue that during immersive episodes, pretense behaviors can be directly motivated by imagination. In response to these challenges, philosophers typically accept that imagination can have a guidance or stage-setting role in motivating behaviors, but reject that it directly outputs to action-generation system (Van Leeuwen 2009; O’Brien 2005; Funkhouser & Spaulding 2009; Everson 2007; Kind 2011; Currie & Ravenscroft 2002).

Another purported functional difference between imagination and belief concerns their characteristic connection to emotions. If the liar truly believes that his pants are on fire, then he will be genuinely afraid of the fire; but not if he merely imagines so. While belief evokes genuine emotions toward real entities, imagination does not (Walton 1978, 1990, 1997; see also related discussion of the paradox of fictional emotions in Supplement on Puzzles and Paradoxes of Imagination and the Arts ). This debate is entangled with the controversy concerning the nature of emotions (see the entry on emotion ). In rejecting this purported functional difference, philosophers also typically reject narrow cognitivism about emotions (Nichols 2004a; Meskin & Weinberg 2003; Weinberg & Meskin 2005, 2006; Kind 2011; Spaulding 2015; Carruthers 2003, 2006).

Currently, the consensus is that there exists some important difference between imagining and believing. Yet, there are two distinct departures from this consensus. On the one hand, some philosophers have pointed to novel psychological phenomena in which it is unclear whether imagination or belief is at work—such as delusions (Egan 2008a) and immersed pretense (Schellenberg 2013)—and argued that the best explanation for these phenomena says that imagination and belief exists on a continuum. In responding to the argument from immersed pretense, Shen-yi Liao and Tyler Doggett (2014) argue that a cognitive architecture that collapses distinctive attitudes on the basis of borderline cases is unlikely to be fruitful in explaining psychological phenomena. On the other hand, some philosophers have pointed to familiar psychological phenomena and argued that the best explanation for these phenomena says that imagination is ultimately reducible to belief. Peter Langland-Hassan (2012, 2014) argues that pretense can be explained with only reference to beliefs—specifically, beliefs about counterfactuals. Derek Matravers (2014) argues that engagements with fictions can be explained without references to imaginings.

To desire is to want something to be the case (see the entry on desire ). Standardly, the conative attitude of desire is contrasted with the cognitive attitude of belief in terms of direction of fit: while belief aims to make one’s mental representations match the way the world is, desire aims to make the way the world is match one’s mental representations. Recall that on the single code hypothesis , there exists a cognitive imaginative attitude that is structurally similar to belief. Is there a conative imaginative attitude—call it desire-like imagination (Currie 1997, 2002a, 2002b, 2010; Currie & Ravenscroft 2002), make-desire (Currie 1990; Goldman 2006), or i-desire (Doggett & Egan 2007, 2012)—that is structurally similar to desire?

The debates on the relationship between imagination and desire is, not surprisingly, thoroughly entangled with the debates on the relationship between imagination and belief. One impetus for positing a conative imaginative attitude comes from behavior motivation in imaginative contexts. Tyler Doggett and Andy Egan (2007) argue that cognitive and conative imagination jointly output to action-generation system, in the same way that belief and desire jointly do. Another impetus for positing a conative imaginative attitude comes from emotions in imaginative contexts (see related discussions of the paradox of fictional emotions and the paradoxes of tragedy and horror in Supplement on Puzzles and Paradoxes of Imagination and the Arts ). Gregory Currie and Ian Ravenscroft (2002) and Doggett and Egan (2012) argue the best explanation for people’s emotional responses toward non-existent fictional characters call for positing conative imagination. Currie and Ravenscroft (2002), Currie (2010), and Doggett and Egan (2007) argue that the best explanation for people’s apparently conflicting emotional responses toward tragedy and horror too call for positing conative imagination.

Given the entanglement between the debates, competing explanations of the same phenomena also function as arguments against conative imagination (Nichols 2004a, 2006b; Meskin & Weinberg 2003; Weinberg & Meskin 2005, 2006; Spaulding 2015; Kind 2011; Carruthers 2003, 2006; Funkhouser & Spaulding 2009; Van Leeuwen 2011). In addition, another argument against conative imagination is that its different impetuses call for conflicting functional properties. Amy Kind (2016b) notes a tension between the argument from behavior motivation and the argument from fictional emotions: conative imagination must be connected to action-generation in order for it to explain pretense behaviors, but it must be disconnected from action-generation in order for it to explain fictional emotions. Similarly, Shaun Nichols (2004b) notes a tension between Currie and Ravenscroft’s (2002) argument from paradox of fictional emotions and argument from paradoxes of tragedy and horror.

To have a (merely) mental image is to have a perception-like experience triggered by something other than the appropriate external stimulus; so, for example, one might have “a picture in the mind’s eye or … a tune running through one’s head” (Strawson 1970: 31) in the absence of any corresponding visual or auditory object or event (see the entry on mental imagery ). While it is propositional imagination that gets compared to belief and desire, it is sensory or imagistic imagination that get compared to perception (Currie & Ravenscroft 2002). Although it is possible to form mental images in any of the sensory modalities, the bulk of discussion in both philosophical and psychological contexts has focused on visual imagery.