25 Great Nonfiction Essays You Can Read Online for Free

Alison Doherty

Alison Doherty is a writing teacher and part time assistant professor living in Brooklyn, New York. She has an MFA from The New School in writing for children and teenagers. She loves writing about books on the Internet, listening to audiobooks on the subway, and reading anything with a twisty plot or a happily ever after.

View All posts by Alison Doherty

I love reading books of nonfiction essays and memoirs , but sometimes have a hard time committing to a whole book. This is especially true if I don’t know the author. But reading nonfiction essays online is a quick way to learn which authors you like. Also, reading nonfiction essays can help you learn more about different topics and experiences.

Besides essays on Book Riot, I love looking for essays on The New Yorker , The Atlantic , The Rumpus , and Electric Literature . But there are great nonfiction essays available for free all over the Internet. From contemporary to classic writers and personal essays to researched ones—here are 25 of my favorite nonfiction essays you can read today.

“Beware of Feminist Lite” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The author of We Should All Be Feminists writes a short essay explaining the danger of believing men and woman are equal only under certain conditions.

“It’s Silly to Be Frightened of Being Dead” by Diana Athill

A 96-year-old woman discusses her shifting attitude towards death from her childhood in the 1920s when death was a taboo subject, to World War 2 until the present day.

“Letter from a Region in my Mind” by James Baldwin

There are many moving and important essays by James Baldwin . This one uses the lens of religion to explore the Black American experience and sexuality. Baldwin describes his move from being a teenage preacher to not believing in god. Then he recounts his meeting with the prominent Nation of Islam member Elijah Muhammad.

“Relations” by Eula Biss

Biss uses the story of a white woman giving birth to a Black baby that was mistakenly implanted during a fertility treatment to explore racial identities and segregation in society as a whole and in her own interracial family.

“Friday Night Lights” by Buzz Bissinger

A comprehensive deep dive into the world of high school football in a small West Texas town.

“The Case for Reparations” by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Coates examines the lingering and continuing affects of slavery on American society and makes a compelling case for the descendants of slaves being offered reparations from the government.

“Why I Write” by Joan Didion

This is one of the most iconic nonfiction essays about writing. Didion describes the reasons she became a writer, her process, and her journey to doing what she loves professionally.

“Go Gentle Into That Good Night” by Roger Ebert

With knowledge of his own death, the famous film critic ponders questions of mortality while also giving readers a pep talk for how to embrace life fully.

“My Mother’s Tongue” by Zavi Kang Engles

In this personal essay, Engles celebrates the close relationship she had with her mother and laments losing her Korean fluency.

“My Life as an Heiress” by Nora Ephron

As she’s writing an important script, Ephron imagines her life as a newly wealthy woman when she finds out an uncle left her an inheritance. But she doesn’t know exactly what that inheritance is.

“My FatheR Spent 30 Years in Prison. Now He’s Out.” by Ashley C. Ford

Ford describes the experience of getting to know her father after he’s been in prison for almost all of her life. Bridging the distance in their knowledge of technology becomes a significant—and at times humorous—step in rebuilding their relationship.

“Bad Feminist” by Roxane Gay

There’s a reason Gay named her bestselling essay collection after this story. It’s a witty, sharp, and relatable look at what it means to call yourself a feminist.

“The Empathy Exams” by Leslie Jamison

Jamison discusses her job as a medical actor helping to train medical students to improve their empathy and uses this frame to tell the story of one winter in college when she had an abortion and heart surgery.

“What I Learned from a Fitting Room Disaster About Clothes and Life” by Scaachi Koul

One woman describes her history with difficult fitting room experiences culminating in one catastrophe that will change the way she hopes to identify herself through clothes.

“Breasts: the Odd Couple” by Una LaMarche

LaMarche examines her changing feelings about her own differently sized breasts.

“How I Broke, and Botched, the Brandon Teena Story” by Donna Minkowitz

A journalist looks back at her own biased reporting on a news story about the sexual assault and murder of a trans man in 1993. Minkowitz examines how ideas of gender and sexuality have changed since she reported the story, along with how her own lesbian identity influenced her opinions about the crime.

“Politics and the English Language” by George Orwell

In this famous essay, Orwell bemoans how politics have corrupted the English language by making it more vague, confusing, and boring.

“Letting Go” by David Sedaris

The famously funny personal essay author , writes about a distinctly unfunny topic of tobacco addiction and his own journey as a smoker. It is (predictably) hilarious.

“Joy” by Zadie Smith

Smith explores the difference between pleasure and joy by closely examining moments of both, including eating a delicious egg sandwich, taking drugs at a concert, and falling in love.

“Mother Tongue” by Amy Tan

Tan tells the story of how her mother’s way of speaking English as an immigrant from China changed the way people viewed her intelligence.

“Consider the Lobster” by David Foster Wallace

The prolific nonfiction essay and fiction writer travels to the Maine Lobster Festival to write a piece for Gourmet Magazine. With his signature footnotes, Wallace turns this experience into a deep exploration on what constitutes consciousness.

“I Am Not Pocahontas” by Elissa Washuta

Washuta looks at her own contemporary Native American identity through the lens of stereotypical depictions from 1990s films.

“Once More to the Lake” by E.B. White

E.B. White didn’t just write books like Charlotte’s Web and The Elements of Style . He also was a brilliant essayist. This nature essay explores the theme of fatherhood against the backdrop of a lake within the forests of Maine.

“Pell-Mell” by Tom Wolfe

The inventor of “new journalism” writes about the creation of an American idea by telling the story of Thomas Jefferson snubbing a European Ambassador.

“The Death of the Moth” by Virginia Woolf

In this nonfiction essay, Wolf describes a moth dying on her window pane. She uses the story as a way to ruminate on the lager theme of the meaning of life and death.

You Might Also Like

Nonfiction Essay

While escaping in an imaginary world sounds very tempting, it is also necessary for an individual to discover more about the events in the real world and real-life stories of various people. The articles you read in newspapers and magazines are some examples of nonfiction texts. Learn more about fact-driven information and hone your essay writing skills while composing a nonfiction essay.

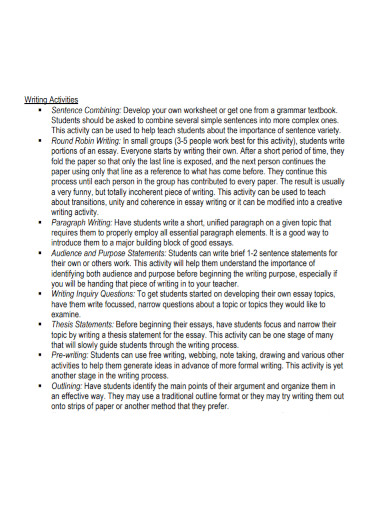

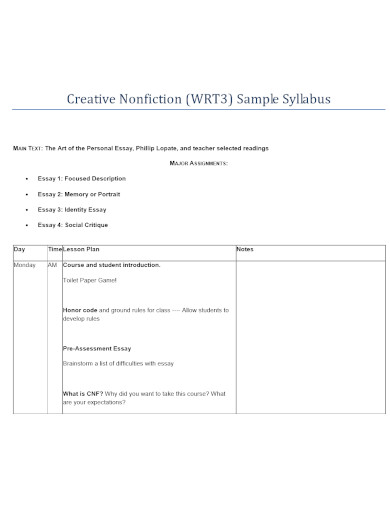

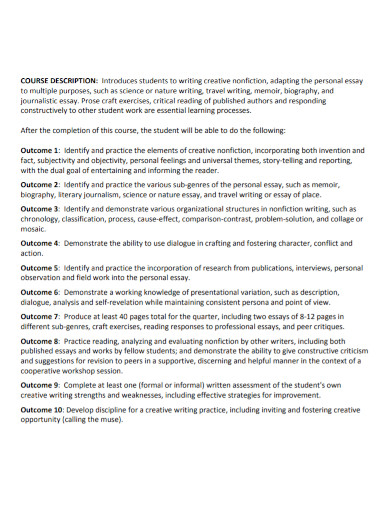

10+ Nonfiction Essay Examples

1. creative nonfiction essay.

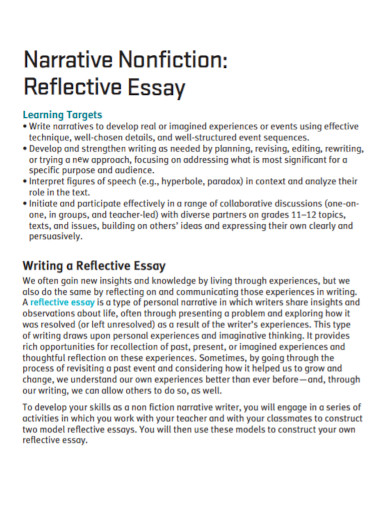

2. Narrative Nonfiction Reflective Essay

Size: 608 KB

3. College Nonfiction Essay

Size: 591 KB

4. Non-Fiction Essay Writing

Size: 206 KB

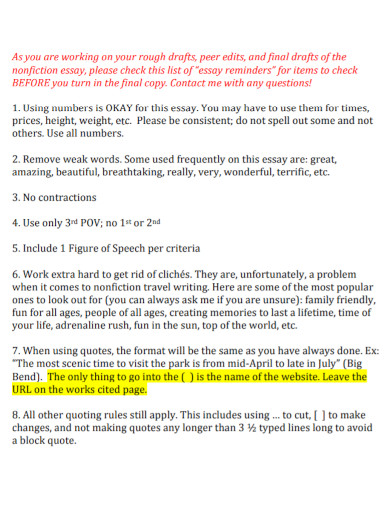

5. Nonfiction Essay Reminders

Size: 45 KB

6. Nonfiction Essay Template

Size: 189 KB

7. Personal Nonfiction Essay

Size: 51 KB

8. Teachers Nonfiction Essay

Size: 172 KB

9. Creative Nonfiction Assignment Essay

Size: 282 KB

10. Nonfiction Descriptive Essay

11. Literary Arts Nonfiction Essay

Size: 93 KB

What Is a Nonfiction Essay?

Nonfiction essay refers to compositions based on real-life situations and events. In addition, it also includes essays based on one’s opinion and perception. There are different purposes for writing this type of essay. Various purposes use different approaches and even sometimes follow varying formats. Educational and informative essays are some examples of a nonfiction composition.

How to Compose a Compelling Nonfiction Essay

When you talk about creative writing, it is not all about creating fictional stories. It also involves providing a thought-provoking narrative and description of a particular subject. The quality of writing always depends on how the writers present their topic. That said, keep your readers engaged by writing an impressive nonfiction paper.

1. Know Your Purpose

Before you start your essay, you should first determine the message you want to deliver to your readers. In addition, you should also consider what emotions you want to bring out from them. List your objectives beforehand. Goal-setting will provide you an idea of the direction you should take, as well as the style you should employ in writing about your topic on your essay paper.

2. Devise an Outline

Now that you have a target to aim for, it is time to decide on the ideas you want to discuss in each paragraph. To do this, you can utilize a blank outline template. Also, prepare an essay plan detailing the structure and the flow of the message of your essay. Ensure to keep your ideas relevant and timely.

3. Generate Your Thesis Statement

One of the most crucial parts of your introduction is your thesis statement . This sentence will give the readers an overview of what to expect from the whole document. Aside from that, this statement will also present the main idea of the essay content. Remember to keep it brief and concise.

4. Use the Appropriate Language

Depending on the results of your assessment in the first step, you should tailor your language accordingly. If you want to describe something, use descriptive language. If you aim to persuade your readers, you should ascertain to use persuasive words. This step is essential to remember for the writers because it has a considerable impact on achieving your goals.

What are the various types of nonfiction articles?

In creatively writing nonfiction essays, you can choose from various types. Depending on your topic, you can write a persuasive essay , narrative essay, biographies, and even memoirs. In addition, you can also find nonfiction essay writing in academic texts, instruction manuals, and even academic reports . Even if most novels are fiction stories, there are also several nonfictions in this genre.

Why is writing nonfiction essays necessary?

Schools and universities use nonfiction essays as an instrument to train and enhance their students’ skills in writing. The reason for this is it will help them learn how to structure paragraphs and also learn various skills. In addition, this academic essay can also be a tool for the teachers to analyze how the minds of their students digest situations.

How can I write about a nonfiction topic?

A helpful tip before crafting a nonfiction essay is to explore several kinds of this type of writing. Choose the approach and the topic where you are knowledgeable. Now that you have your lesson topic, the next step is to perform intensive research. The important part is to choose a style on how to craft your story.

Each of us also has a story to tell. People incorporate nonfiction writing into their everyday lives. Your daily journal or the letters you send your friends all belong under this category of composition. Writing nonfiction essays are a crucial outlet for people to express their emotions and personal beliefs. We all have opinions on different events. Practice writing nonfiction articles and persuade, entertain, and influence other people.

Nonfiction Essay Generator

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Write about the influence of technology on society in your Nonfiction Essay.

Discuss the importance of environmental conservation in your Nonfiction Essay.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a narrative essay | Example & tips

How to Write a Narrative Essay | Example & Tips

Published on July 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A narrative essay tells a story. In most cases, this is a story about a personal experience you had. This type of essay , along with the descriptive essay , allows you to get personal and creative, unlike most academic writing .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is a narrative essay for, choosing a topic, interactive example of a narrative essay, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about narrative essays.

When assigned a narrative essay, you might find yourself wondering: Why does my teacher want to hear this story? Topics for narrative essays can range from the important to the trivial. Usually the point is not so much the story itself, but the way you tell it.

A narrative essay is a way of testing your ability to tell a story in a clear and interesting way. You’re expected to think about where your story begins and ends, and how to convey it with eye-catching language and a satisfying pace.

These skills are quite different from those needed for formal academic writing. For instance, in a narrative essay the use of the first person (“I”) is encouraged, as is the use of figurative language, dialogue, and suspense.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Narrative essay assignments vary widely in the amount of direction you’re given about your topic. You may be assigned quite a specific topic or choice of topics to work with.

- Write a story about your first day of school.

- Write a story about your favorite holiday destination.

You may also be given prompts that leave you a much wider choice of topic.

- Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself.

- Write about an achievement you are proud of. What did you accomplish, and how?

In these cases, you might have to think harder to decide what story you want to tell. The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to talk about a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

For example, a trip where everything went according to plan makes for a less interesting story than one where something unexpected happened that you then had to respond to. Choose an experience that might surprise the reader or teach them something.

Narrative essays in college applications

When applying for college , you might be asked to write a narrative essay that expresses something about your personal qualities.

For example, this application prompt from Common App requires you to respond with a narrative essay.

In this context, choose a story that is not only interesting but also expresses the qualities the prompt is looking for—here, resilience and the ability to learn from failure—and frame the story in a way that emphasizes these qualities.

An example of a short narrative essay, responding to the prompt “Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself,” is shown below.

Hover over different parts of the text to see how the structure works.

Since elementary school, I have always favored subjects like science and math over the humanities. My instinct was always to think of these subjects as more solid and serious than classes like English. If there was no right answer, I thought, why bother? But recently I had an experience that taught me my academic interests are more flexible than I had thought: I took my first philosophy class.

Before I entered the classroom, I was skeptical. I waited outside with the other students and wondered what exactly philosophy would involve—I really had no idea. I imagined something pretty abstract: long, stilted conversations pondering the meaning of life. But what I got was something quite different.

A young man in jeans, Mr. Jones—“but you can call me Rob”—was far from the white-haired, buttoned-up old man I had half-expected. And rather than pulling us into pedantic arguments about obscure philosophical points, Rob engaged us on our level. To talk free will, we looked at our own choices. To talk ethics, we looked at dilemmas we had faced ourselves. By the end of class, I’d discovered that questions with no right answer can turn out to be the most interesting ones.

The experience has taught me to look at things a little more “philosophically”—and not just because it was a philosophy class! I learned that if I let go of my preconceptions, I can actually get a lot out of subjects I was previously dismissive of. The class taught me—in more ways than one—to look at things with an open mind.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

If you’re not given much guidance on what your narrative essay should be about, consider the context and scope of the assignment. What kind of story is relevant, interesting, and possible to tell within the word count?

The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to reflect on a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

Don’t worry too much if your topic seems unoriginal. The point of a narrative essay is how you tell the story and the point you make with it, not the subject of the story itself.

Narrative essays are usually assigned as writing exercises at high school or in university composition classes. They may also form part of a university application.

When you are prompted to tell a story about your own life or experiences, a narrative essay is usually the right response.

The key difference is that a narrative essay is designed to tell a complete story, while a descriptive essay is meant to convey an intense description of a particular place, object, or concept.

Narrative and descriptive essays both allow you to write more personally and creatively than other kinds of essays , and similar writing skills can apply to both.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write a Narrative Essay | Example & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved April 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/narrative-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an expository essay, how to write a descriptive essay | example & tips, how to write your personal statement | strategies & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Additional menu

The Creative Penn

Writing, self-publishing, book marketing, making a living with your writing

How To Write Narrative Non-Fiction With Matt Hongoltz-Hetling

posted on August 24, 2020

Podcast: Download (Duration: 1:04:14 — 52.2MB)

Subscribe: Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

What is narrative non-fiction and how do you write a piece so powerful it is nominated for a Pulitzer? In this interview, Matt Hongoltz-Hetling talks about his process for finding stories worth writing about and how he turns them into award-winning articles.

In the intro, I talk about Spotify (possibly) getting into audiobooks and Amazon (possibly) getting into podcasts as reported on The Hotsheet , and the New Publishing Standard . David Gaughran's How to Sell Books in 2020 ; a college student who used GPT3 to reach the top of Hacker News with an AI-generated blog post [ The Verge ]; and ALLi on Is Copyright Broken? Artificial Intelligence and Author Copyright . Plus, synchronicity in book research, and my personal podcast episode on Druids, Freemasons, and Frankenstein: The Darker Side of Bath, England (where I live!)

Matt Hongoltz-Hetling is a Pulitzer finalist and award-winning investigative journalist. He's also the author of A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear .

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript below.

- From writing for pennies an article to writing a Pulitzer – nominated article

- What is narrative non-fiction?

- How does narrative non-fiction differ from fiction?

- Where ideas come from and how to begin forming a story idea

- The necessity of being respectful of the real lives being examined and written about

- Portraying interview subjects with shades of grey

- Turning hours of source material into something coherent

- Finding the balance between story structure and meaning

- Knowing when an idea is appropriate for a book

You can find Matt Hongoltz-Hetling at matt-hongoltzhetling.com and on Twitter @hh_matt

Transcript of Interview with Matt Hongoltz-Hetling

Joanna: Matt Hongoltz-Hetling is a Pulitzer finalist and award-winning investigative journalist. He's also the author of A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear . Welcome, Matt.

Matt: Hey, thanks for having me on, Joanna.

Joanna: It's great to have you on the show.

First up, tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing.

Matt: I got into writing when I was eight years old and I wrote this amazing book. I don't want to brag, but I wrote this book about an elf that was fighting in a dungeon, and this elf had some items of a magical persuasion and used them to defeat all sorts of monsters. So, that was pretty awesome. And I've been writing stuff ever since.

I grew up knowing that I wanted to write, loving to read, all that. And then my career path never really seemed to go that way. I actually started a student newspaper when I was in college in the hopes that that would be primarily a writing occupation, but I found very quickly that it was more small business skills that were needed.

I was selling advertisements much more so than writing to fill the newspaper sadly. And so, at some point I had just got the pile of rejection slips that I think we're all familiar with. I just didn't really know how to go about getting into the industry.

I was literally writing articles for, like, 25 cents an article, these, like, ‘How do you fix an engine?' or not even an engine, nothing that complicated, but, ‘How do you clean a window?'

Joanna: Content farms.

Matt: Yes, right. Content farms. Yes. Thank you. But I was writing.

My wife encouraged me to submit an article for my local weekly newspaper in a small town in the state of Maine. And that led to me being able to write more articles, still for very small amounts, 30 bucks an article. And that led to me getting a full-time job as a journalist at a weekly newspaper in rural Maine.

And even though that was fantastically exciting for me, I always knew that I wanted to do more. And so, I was always pushing, looking for that next level that would allow me to write more of the stuff that I wanted to write. And so, that led to larger newspapers, and then magazine opportunities, and then magazine opportunities led to a book opportunity. Now, I'm happy that I am just on the cusp of publishing my first book. I'm very excited about that.

Joanna: We're going to get into that in a second, but I just wonder because this is so fascinating.

How many years was it between writing for a content farm to being a Pulitzer finalist?

Matt: That was actually the shortest journey that you can imagine. Within, let's say, two years of my first newspaper article. I wrote the article that led to my highest-profile resume point which was that Pulitzer finalist status. And that article was about substandard housing conditions in the federal Section 8 program. It's federally subsidized housing and it's meant to be kept up to a certain standard, and the article which I wrote with a writing partner demonstrated that it was not and that there were a lot of people at fault.

What really elevated that article, it was a good article and all of that, but what really got it that level of recognition was that it also turned out to be an impactful article. It happened to come at a time when other people were looking at the housing authority for various reasons. It really struck a nerve and our Senator, Republican Susan Collins of Maine, she took a very avid interest in our reporting and was motivated to encourage reforms of the national Section 8 system.

She was in a political position to do that because she held the purse strings for the housing authorities. And so, it happened to have this very disproportionate impact and because it led to a positive change for the Section 8 housing program in the United States.

I think the people in the Pulitzer committee must've loved the idea that this tiny little rural weekly newspaper where we had three reporter desks, one of which was perennially vacant, had managed to write a story that was really relevant to the national scene.

Joanna: Absolutely fascinating. And I hope that encourages people listening who might feel that they're in a place in their writing career where they're not feeling very successful and yet you bootstrapped your way up there to something really impactful, as you say.

We're going to come back to the craft of writing, but let's just define ‘narrative nonfiction.' Your book, A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear , which is a great title.

What is narrative nonfiction and where's the line between that and fiction or straight nonfiction?

Matt: Narrative nonfiction, the way that I think of it is i t's basically just like any other fiction book, or novel, or piece that you might pick up except for the events described in it actually happened .

When I think of the difference, it just seems, to me, to be such a small, tiny little difference between fiction and nonfiction because when you write fiction, you're starting with an infinite number of possible events to write about. And when you're writing nonfiction, you're starting with a universe of events.

You're starting with everything that ever happened in the entire universe. That's the material that you can draw on. It is so close to infinite that really, it's just a method of curation. You're going to select some of these facts and arrange them in an order that will create the same exact experience as a powerful piece of fiction writing.

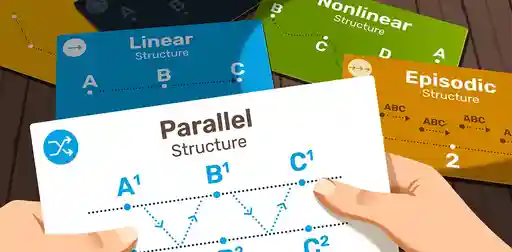

A narrative piece emphasizes the same things that a fiction story would in terms of there's character arcs, there are transformations, there's setting. We want a climax, we want everything that you would want when you're writing a fiction piece.

Joanna: Interesting. And you said at the beginning that it's a tiny difference between fiction and nonfiction. And I'm like, ‘No, surely, this is the biggest separation.' So, I feel like people would have quite a different view on that, but it's interesting because you said there, ‘a method of curation,' and you select the facts, whereas with fiction, obviously, you make it up.

How can you curate truth in a way that serves your story but doesn't distort what really happened?

Matt: That's an excellent question. And I think you do have to be careful to keep things in perspective.

So, I was thinking, ‘What if I was writing about someone in the aeronautics industry or who was an astronaut or maybe someone else within the industry who is motivated by this idea that people want to,' or yeah, ‘that he would like people to colonize the stars?' That's, I think, a very common sci-fi-type theme, and it's also very apparent in the people who go into those fields.

And so, you might take a set of facts. I would ask that person, ‘What are some of the seminal moments in your career? What were the turning points? What were the important things that shaped you as a person?' And this was just an idea that I had, I would look at the amount of cosmic matter in our atmosphere. So, every time a meteor hits the atmosphere, we know it burns up, dust rains down on the earth and that dust becomes part of us. We breathe it in.

Then I would try to draw a timeline between some natural spike in the amount of cosmic dust in the air that might've gone into our subject's body, and that person's decision to get into aeronautics. So, you maybe get to describe that this fantastic spectacular event of a comet the size of a blue whale entering the atmosphere, burning up, raining dust down on, let's say, North America.

And this aeronautics person is 12 years old at the time, he's thinking about baseball, but then he goes to a museum two weeks later and he's breathing in more cosmic dust on that day than he would on an average day, and then he decides to become an astronaut.

You can paint a very poetic scene with that, but it's also very important that you're not actually suggesting or theorizing that the cosmic dust had anything to do with that person's decision.

It's a way to wax poetically about this character and to maybe access a greater idea which is that we all want to go colonize the stars to some extent. That's a very human thing. It appears in our very earliest writings on both fictional and non-fictional.

And you can talk about this amazing spectacular event, you can talk about this person's decision, and if you do it right, the audience will understand that you've just used this as a jumping-off point to explore some of these bigger concepts and cool narrative opportunities without actually saying in a false way that cosmic dust is what makes us want to go out there. So, I'm just saying that you can arrange those events in a way that gives it life, and vibrancy, and maybe some creativity.

Joanna: I like that example. And you brought up so many things that I'm thinking about there.

First of all is using the individual to highlight the universal. If you wrote a piece about how big the universe is or whatever, that's not narrative nonfiction. That might be one of your how-to articles back in the day. So, you've used someone's experience to highlight something universal.

Where do you start? Because this is a question that fiction writers think about all the time. Do you start with the theme of, say, space? Do you start with a character, say you met someone and you want to interview them, or are you starting with, in your case, I guess, a commission or are you starting with just your own curiosity and following where it goes? So, I guess, as you said, that you could write about anything in the whole world.

How do you decide what to write?

Matt: I've spent a lot of my freelance writing career trying to craft pitches that will convince editors to give me a green light and offer me compensation in exchange for a piece of writing. And so, that undergirding structure allows for all those sorts of scenarios that you posit.

I'm always keeping my eye out for things when something interests me and lights me up, then I try to think about how I can make that subject or person who has just lit me up into a pitch that is marketable. I saw a freestyle street rapper a few weeks ago and I was really into what he was doing. I just thought he was amazing because his shtick was that he would incorporate things about the world around him into his rhymes really seamlessly.

I thought, ‘Oh, this guy has got this really amazing talent.' And so then you start thinking like, ‘Is this something that I would pitch to maybe a magazine about rhyme and rhyme structure or is this something that might be more like…is this a cognitive or a neurological skill that he's developed and how might that fit into maybe more of a neuroscience type magazine or is this just a guy who's got the great American story of, he developed a skill on the streets as it were, and then launched it into a career, in which case, we have maybe more of a universal story that could appear in any major market magazine?'

I suppose usually what sparks my interest is a person but it's not at all uncommon for my interest to also be sparked by just a topic. And then I'm searching for those characters who can exemplify that topic.

Joanna: Your writing does focus very much on people and all characters, as you say, but I'm wondering where do you take it from then? How do you tease out the story? Do you interview them?

And again, when you have this material about that person, how do you highlight your story, but also respect the person because you might say that, so, you've got the pitch with the neurological aspect. So, you think, ‘Okay. I want to write about how his brain works differently to someone else, how he can do that,' but then you find out some awful thing and you think that, ‘Okay. How do I respect this person, but how do I also deliver on my pitch?'

How do we ask the right questions to make our characters real, but also be respectful, because this is real life you're writing about?

Matt: My own inclination and approach is typically to just jump in and that's often great because it allows me to maintain forward momentum and use real wishful positive thinking to just hope that everything's going to pan out.

But sometimes its failing is that I will go very confidently striding down what turns out to be a dead end. And so, maybe I pitch this thing as a neurological sciencey story, and then a magazine editor says, ‘Yes, let's do this.' And so then I go back to the subject and I say, ‘I'd like to interview you,' and tell them what's going on.

And in the course of the interview, it turns out that they are not at all representative of the category of box that I want to put them into. And then I've suddenly got this big, awkward problem where I am looking for a different subject to satisfy the magazine editor and trying to get value out of my initial subject and my interview with him by placing him into something that is more appropriate for him. But when I get to that interview phase, I typically like to already have a commission in place before I do that because it's quite a time investment.

When I do interview someone, I like to make them very lengthy, in-depth interviews. Rarely do I talk to someone for less than two or three hours. And in the course of that two or three hours, my interview style is to not necessarily focus too much on asking the right questions so much as just unlocking how they see themselves and what is important to them, and get them talking about what lights them up.

And by not having a very firm idea of where I want to lead a subject, and being flexible in what they can say, what I find is that I often wind up with a really interesting story that maybe doesn't quite fit the mold precisely for where I thought it would go, but it's close enough that I can bridge that gap and the narrative is so compelling and good that nobody cares if there's maybe a slight sidetrack, a slight departure.

And as far as what if you find out something bad about someone while you're in the course of that interview? You're interviewing a person and they suddenly put the interview on pause and speak very sharply or meanly to their spouse or child and suddenly you get the feeling like, ‘You know what, this isn't really actually a very good person.' So, what do you do there?

I think it is very important to acknowledge the bad in people. And it's almost a necessary component. If I am not writing something both bad and good about a person that I'm writing about, then I know I'm not really doing a very good job because I don't know any people who are 100% good and I don't know any people who are 100% bad.

Oftentimes, if I'm talking to someone who we might think of as the hero of a narrative, they're doing good work, we're spotlighting them because of some amazing accomplishment they've done, I think it's really important to throw in a couple of negative character traits or details that will add a note of reality to your writing.

And conversely, if I'm interviewing someone who has committed murder or if I'm interviewing them because they're a bad person, then I'm always really looking for that redeeming quality because some murderers have just had a very bad day or gone through a very bad period in their life and maybe had some disadvantages in the first place.

Even though they've done this terrible, awful thing, there's still some context that you can provide that humanizes them. I think that most of my subjects, I think, appreciate that. Certainly, I've written about some people who've been very unhappy with how they've been portrayed. But I think most people appreciate it when you portray enough facets of their character that their true personality comes through.

Joanna: I've not done this kind of writing. So, I find it fascinating. I've been doing this podcast for 12 years and I have many, many, many hours and a lot of transcripts of material and I've thought many times, ‘It'd be great if I could go through and find all these snippets and turn this into something.' Working with transcripts is really hard. You just mentioned, you have a three-hour interview. So, presumably, you're recording this and you're taking notes as well.

How do you turn all this source material into an article? What's your curation and what's that process?

Matt: I am the kind of person who hates to throw things out. My wife will tell you that that can drive her nuts. And the same is true of my writing. I like to start with everything that has been said, even in a three-hour interview, and then just slowly apply criteria that squeezed some things out.

I always wind up with more material than will fit in the space that I have allotted. And then that encourages me to try to cram more words and more facts into smaller spaces and that results in this real efficient distillation. I think that's another good thing maybe about not being too goal-oriented when you write.

What I typically do is I'll interview someone, we'll have the three-hour interview. I've got copious notes, I got an audio transcript. If I am feeling up to it, I will transcribe every word of that audio interview which is grueling. Sometimes I will use one of those online programs that will convert it and spit out a transcript for you. And that transcript is never perfect, but you can make it perfect by listening and going through. And then I just slowly go through and clean it up.

Often, it's not like writing at all. It's like just fixing things. I might go through it and just correct all the typos in my transcription. And then I might go through and remove all the garble and then I might go through and anything that seems like a cohesive thought, I might put quotation marks around and put on the, ‘he said,' or the, ‘she said.'

Then I will maybe strip out, I'll say, ‘Oh, here, this person talked for 10 minutes about their mother and they were actually quite redundant, but here, this one time they said it, it was the most striking of the eight times they said the same thing.' And so, I will move those other seven iterations down to a notes section at the bottom.

And in this way, I am slowly shrinking and squeezing the text that is there. And if there are things that they've said, points they've made that are important, but that they didn't say it particularly well, then I might write a paraphrase and put the originals down in my notes section.

And then at some point, I will create a series of categories that represent different areas of the story, and then I will sort all of their quotes into those different categories. And all of this stuff that I've just talked about is very mechanical. So, even if you're not feeling particularly inspired, you can go through this rote, brute-force process and nibble away, and nibble away, and nibble away.

What you find at the end is that you actually have the bones of a story.

Often, the story will also involve going through the same process with multiple people and other sources of information, but once you've arranged all that stuff under the subheadings, and then you start to rearrange things within those sections, you find that you are suddenly, magically two-thirds of the way there.

Joanna: That's fascinating. I want to ask about this Pulitzer thing because I know everyone's so interested. And really, this is one of those prizes that is, for many people, a life goal, and you've actually won other awards. You're a multi-award-winning writer.

What's interesting to me is you talked about a story that made an impact. Substandard housing conditions is not the most inspirational thing for most people, but it's interesting. Presumably, you're not winning these prizes for your beautiful sentence structure.

For those authors who obsess with grammar and exact sentences, where's the line between that and story and meaning?

Matt: I think it is all-important including the sentence structure. I always take the position that grammar, and grammar is not really all that important other than in the service of making points very clearly. I really tend to take these very esoteric grammar points and just chuck them out the window because I want somebody to be able to understand what I'm saying.

Oftentimes, adhering very strictly to the rules of grammar impedes the knowledge of the layperson who I want to be able to read, and digest, and appreciate my article . I don't want to poo-poo sentence structure too much. I think there are so many articles written that you're trying to break through the noise of, and stand out in some way. I think the stories that I've been awarded from various organizations and for various things, they've all gone through the same basic process as many of my stories that have not been so recognized and have not turned out necessarily all that good.

But for whatever reason, there was a perfect alignment where the person that I happened to be talking to happened to exemplify that issue just right and the setting happened to work out and the climax of their personal story… there's a lot of just happenstance, I suppose, in that once you've been commissioned to write a story, you're writing that story.

And sometimes the material will support a real cracker-jack breakout story. What's more often is that as you go through the process, you hit an obstacle that you have to smooth over in some way and you turn in a very serviceable, perfectly good story.

But the things that I think really allow it to break through and get head and shoulders above tend to be things that are out of your control. You're going to do your very best job of research, you're going to do your very best job of writing, you're going to use all the good phrases, you're going to exert full control of your mastery of time and space, you're going to jump around in the narrative if that's in the timeline rather, if that's what the narrative calls for.

If you want to focus on the beating of a fly's wings, for some reason, you will do that. If you want to jump back into prehistory, you'll do that. And after you've employed all of those tricks and techniques to craft the very best story that you possibly can from the material, sometimes the material itself will just harmonize perfectly and get you to that place to achieve that potential that you hoped that you could. It's a little bit of luck and magic, I suppose. We can't always summon it or bottle it.

Joanna: Coming to the book, A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear , which, again, I love the title. It's great. What was it about this idea that made you decide to turn this story into a book-length project rather than a long-form article?

How did you know, ‘Right, I'm going to write a book about this?'

Matt: I was first commissioned for an article on the same topic. The story for those who don't know, it's about a group of libertarians which is a fringe political movement within the United States and their emphasis is on personal freedoms and personal rights.

This national group of libertarians decided to come to one small town, and just take over the town, and turn it into their utopia. Soon after they tried to enact this kind of crazy heist of the town, the town started experiencing bear problems. And so, the book is about how those things are connected.

I was initially commissioned to write an article based on the unusual bear activity that was seen in that town. I was interviewing a woman for my local newspaper about her difficulties in accessing VA benefits. And she was what we stereotype as a crazy cat lady. She was a little bit of a shut-in, she had a bunch of cats milling around, and I asked her about her cats because it's a good icebreaker, and I like cats.

She said, ‘I used to let them outside, but that was before the bears came.' I was like, ‘Oh, well, that sounds really interesting. Forget about the VA. Tell me about bears.' She just started talking about how a bear had eaten two of her cats and how the bears had become very bold and aggressive and were doing weird things.

I started asking around town, asking other people if they had also had bear experiences that seemed unusual. And when I had a feeling for what was going on in that town, I pitched the magazine article and I was really excited to get this magazine article. I really wanted to do a great job on it because ‘The Atavist Magazine' is a good platform and I knew that it would help me to make the case to other magazines that I could write really good narrative stuff.

I went back to town and went through all the interview process and all of that. And when I wrote my first draft for that magazine article, it was 32,000 words. And they would have accepted 4,000 words. So, the article, which I was very happy with, was still very much of a compromise of what I wanted to say about this bizarre situation involving libertarians and bears in this town.

I got in a couple of the best anecdotes including a situation where a bear fights a llama, but there was so much left unsaid, so many colorful things. In that case, I just had this massive trove of colorful materials sitting in my pocket. I knew that there was a very large narrative there because I had already written probably half of the book-length on it. So, it just seemed very natural to write a book about it.

Joanna: Is it a comedy?

Matt: I would call it a dark comedy. There is a lot of very funny stuff, I think, and I do stray into the comedic quite a bit. But there are also some very, kind of, weighty issues. A woman gets attacked by a bear. That's not funny, but there's also just all sorts of goofy stuff.

The llama thing is great. There's one situation where there are two old women who live next door to each other on a hill, and one of them is absolutely terrified of bears. Every time she cooks steak inside, she won't go outside for a day because she's afraid that the bears will smell the steak on her. And meanwhile, her neighbor has been feeding the bears doughnuts for 20 years and has a crowd of bears sitting outside her home waiting for her to come out with doughnuts and buckets of grain twice a day.

There's just a lot of really absurd situations that I was privy to. And I milk them for all I've got.

Joanna: That's so funny. It's so funny there because, of course, the truth can sometimes be stranger than fiction. And I guess that's what you're doing with narrative nonfiction is you are finding these stories.

We're almost out of time, but I do want to ask you because in your original email to me, you said, ‘I think a lot of writers start off like I started out, isolated and bereft of helpful connections and not the person who is going to schmooze at an event or something.'

How you have managed to do these things and even interview these people and get over those initial issues?

Matt: I think for most of my life, even while being very passionate about writing, I never felt like I was plugged into the writing community. I feel like everyone who went to get an advanced degree in writing, their professor could hook them up and their former colleagues would go out and join the industry and in places that would be helpful to them.

I just felt, like, really locked out of all of that. And schmoozing is definitely helpful, but, Joanna, I know that there's a certain component of your audience that is never going to schmooze because it's not their thing, and if they try really hard to force themselves to schmooze, they will sound like they're someone who's trying really hard to schmooze, right? It's just not going to be in everyone's nature and it wasn't in my nature.

I think even though the non-schmoozers have a disadvantage relative to the schmoozers, the non-schmoozers can get by on the basis of purely professional relationships which is what I did. As a journalist, I did develop a certain skill set in talking to people, but I've never been the guy at the cocktail party of other writers and editors who is like, ‘Hey, hire me for your next opportunity.'

I think for me, the key was to always I started small, I started writing for newspapers. I sent endless pitches and queries with different ideas and I slowly got better at sending those pitches . And every time a story of mine turned out that was something that I was proud of, that turned out pretty good, I added that to my portfolio.

And when one editor gives you a chance, lends you that sympathetic ear and gives you a chance to write for the next tier of publication that you're interested in, if you satisfy that editor, you may not have schmoozed them, but you have a working relationship with them. If they're happy with your work, that's all you need.

If you don't have the ability to schmooze your way into that, you still have an editor that you're working with. And perhaps you can ask that editor if they have other people in the industry who might also be willing to look favorably upon a submission from you where you're not just in the slush pile.

And you go through that process 100 or 1,000 times, and if you pay attention while you do it, you walk out of it with a group of a dozen editors that you can send a pitch to who have some idea of who you are and whether or not they like your work and your writing. And you're just always working to increase that circle of editors who look on you favorably.

Over the years, what I found and was very happy about was that those editors also bounce around from one position to another. Every time someone you know moves from one publication to the other, you want to try to maintain some contact with their initial publication and approach them in their new position and see if that might allow you to expand your horizons a little bit.

It's an iterative, slow process. It's not as easy as going to a cocktail party or a bar and palling around with the people who hold the reins to these publications, but it does get you there.

Joanna: That's great advice because I know I'm an introvert, many people listening are introverts, and knowing that the long-term professional approach is great. I think that's true if it's people submitting to short stories or if people want to get into traditional publishing, then all of that's quite true.

Where can people find you and your work and everything you do online?

Matt: Oh, thank you so much for asking. You can find me on Twitter @hh_matt . If you Google my name, you'll get to my website at matt-hongoltzhetling.com , and you can find my book, A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear , on Amazon, any major online retailer, and through the publisher which is PublicAffairs, a subsidiary of Hachette.

Joanna: Fantastic. Well, thanks so much for your time, Matt. That was great.

Matt: Joanna, thank you so much. This has been fantastic.

Reader Interactions

August 24, 2020 at 4:19 am

You always ask great questions Joanna but you outdid yourself this time on a topic I knew nothing about. That bear book sounds fascinating!

August 24, 2020 at 8:47 am

Thanks, Julie! Glad you found it interesting 🙂

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Connect with me on social media

Sign up for your free author blueprint.

Thanks for visiting The Creative Penn!

The Finest Narrative Non-Fiction Essays

Narrative essays that I consider ideal models of the medium

- Linguistics

Perhaps you're the same kind of non- Writer writer. The playful amateur kind who uses it to explore and communicate ideas, rather than making the medium part of your identity. But even amateurs want to be good. I certainly want to get good.

Knowing what you like is half the battle in liking what you create. In that spirit, I collect narrative non-fiction essays that I think are exceptional. They're worth looking at closely – their opening moves, sentence structure, turns of phrase, and narrative arcs.

The only sensible way to improve your writing is by echoing the work of other writers. Good artists copy and great artists steal quotes from Picasso.

You may want to start your own collection of lovely essays like this. There will certainly be some Real Writers who find my list trite and full of basic, mainstream twaddle. It probably is. I've done plenty of self-acceptance work and I'm okay with it.

Twaddle aside, the essays below are worth your attention.

by Paul Ford

Paul Ford explains code in 38,000 words and somehow makes it all accessible, technically accurate, narratively compelling, and most of all, culturally insightful and humanistic.

I have unreasonable feelings about this essay. It is, to me, perfect. Few essays take the interactive medium of the web seriously, and this one takes the cake. There is a small blue cube character, logic diagrams, live code snippets to run, GIFs, tangential footnotes, and a certificate of completion at the end.

by David Foster Wallace – Published under the title 'Shipping Out'

Forgive me for being a David Foster Wallace admirer. The guy had issues, but this account of his 7-day trip on a luxury cruiseliner expresses an inner monologue that is clarifying, rare and often side-splittingly hilarious.

He taught me it is 100% okay to write an entire side-novel in your footnotes if you need to.

by David Graeber

Graeber explores play and work from an anthropological perspective. He's a master of moving between the specific and the general. Between academic theory and personal storytelling. He's always ready with armfuls of evidence and citations but doesn't drown you in them.

by Malcolm Gladwell

This piece uses a typical Gladwellian style. He takes a fairly dull question – Why had ketchup stayed the same, while mustard comes in dozens of varieties? – and presents the case in a way that makes it reasonably intriguing. He's great at starting with specific characters, times and places to draw you in. There are always rich scenes, details, personal profiles, and a grand narrative tying it all together.

Some people find the classic New Yorker essay format overdone, but it relies on storytelling techniques that consistently work.

by Mark Slouka

by Joan Didion

When writers set down the facts of their lives into a compelling story , they’re writing a narrative essay. Personal narrative essays explore the events of the writer’s own life, and by crafting a nonfiction piece that resonates as storytelling, the essayist can uncover deeper truths in the world.

Narrative essays weave the author’s factual lived experiences into a compelling story.

So, what is a narrative essay? Whether you’re writing for college applications or literary journals , this article separates fact from fiction. We’ll look at how to write a narrative essay through a step-by-step process, including a look at narrative essay topics and outlines. We’ll also analyze some successful narrative essay examples.

Learn how to tell your story, your way. Let’s dive into this exciting genre!

What is a Narrative Essay?

The narrative essay is a branch of creative nonfiction . Also known as a personal essay, writers of this genre are tasked with telling honest stories about their lived experiences and, as a result, arriving at certain realizations about life.

Think of personal narrative essays as nonfiction short stories . While the essay and the short story rely on different writing techniques, they arrive at similar outcomes: a powerful story with an idea, theme , or moral that the reader can interpret for themselves.

Now, if you haven’t written a narrative essay before, you might associate the word “essay” with high school English class. Remember those tedious 5-paragraph essays we had to write, on the topic of some book we barely read, about subject matter that didn’t interest us?

Don’t worry—that’s not the kind of essay we’re talking about. The word essay comes from the French essayer , which means “to try.” That’s exactly what writing a narrative essay is: an attempt at organizing the real world into language—a journey of making meaning from the chaos of life.

Narrative essays work to surface meaning from lived experience.

Narrative Essay Example

A great narrative essay example is the piece “Flow” by Mary Oliver, which you can read for free in Google Books .

The essay dwells on, as Mary Oliver puts it, the fact that “we live in paradise.” At once both an ode to nature and an urge to love it fiercely, Oliver explores our place in the endless beauty of the world.

Throughout the essay, Oliver weaves in her thoughts about the world, from nature’s noble beauty to the question “What is the life I should live?” Yet these thoughts, however profound, are not the bulk of the essay. Rather, she arrives at these thoughts via anecdotes and observations: the migration of whales, the strings of fish at high tide, the inventive rescue of a spiny fish from the waterless shore, etc.

What is most profound about this essay, and perhaps most amusing, is that it ends with Oliver’s questions about how to live life. And yet, the stories she tells show us exactly how to live life: with care for the world; with admiration; with tenderness towards all of life and its superb, mysterious, seemingly-random beauty.

Such is the power of the narrative essay. By examining the random facts of our lives, we can come to great conclusions.

What do most essays have in common? Let’s look at the fundamentals of the essay, before diving into more narrative essay examples.

Narrative Essay Definition: 5 Fundamentals

The personal narrative essay has a lot of room for experimentation. We’ll dive into those opportunities in a bit, but no matter the form, most essays share these five fundamentals.

- Personal experience

- Meaning from chaos

- The use of literary devices

Let’s explore these fundamentals in depth.

All narrative essays have a thesis statement. However, this isn’t the formulaic thesis statement you had to write in school: you don’t need to map out your argument with painstaking specificity, you need merely to tell the reader what you’re writing about.

Take the aforementioned essay by Mary Oliver. Her thesis is this: “How can we not know that, already, we live in paradise?”

It’s a simple yet provocative statement. By posing her thesis as a question, she challenges us to consider why we might not treat this earth as paradise. She then delves into her own understanding of this paradise, providing relevant stories and insights as to how the earth should be treated.

Now, be careful with abstract statements like this. Mary Oliver is a master of language, so she’s capable of creating a thesis statement out of an abstract idea and building a beautiful essay. But concrete theses are also welcome: you should compel the reader forward with the central argument of your work, without confusing them or leading them astray.

You should compel the reader forward with the central argument of your work, without confusing them or leading them astray

2. Personal Experience

The personal narrative essay is, shockingly, about personal experience. But how do writers distill their experiences into meaningful stories?

There are a few techniques writers have at their disposal. Perhaps the most common of these techniques is called braiding . Rather than focusing on one continuous story, the writer can “braid” different stories, weaving in and out of different narratives and finding common threads between them. Often, the subject matter of the essay will require more than one anecdote as evidence, and braiding helps the author uphold their thesis while showing instead of telling .

Another important consideration is how you tell your story . Essayists should consider the same techniques that fiction writers use. Give ample consideration to your essay’s setting , word choice , point of view , and dramatic structure . The narrative essay is, after all, a narrative, so tell your story how it deserves to be told.

3. Meaning from Chaos

Life, I think we can agree, is chaotic. While we can trace the events of our lives through cause and effect, A leads to B leads to C, the truth is that so much of our lives are shaped through circumstances beyond our control.

The narrative essay is a way to reclaim some of that control. By distilling the facts of our lives into meaningful narratives, we can uncover deeper truths that we didn’t realize existed.

By distilling the facts of our lives into meaningful narratives, we can uncover deeper truths that we didn’t realize existed.

Consider the essay “ Only Daughter ” by Sandra Cisneros. It’s a brief read, but it covers a lot of different events: a lonesome childhood, countless moves, university education, and the trials and tribulations of a successful writing career.

Coupled with Cisneros’ musings on culture and gender roles, there’s a lot of life to distill in these three pages. Yet Cisneros does so masterfully. By organizing these life events around her thesis statement of being an only daughter, Cisneros finds meaning in the many disparate events she describes.

As you go about writing a narrative essay, you will eventually encounter moments of insight . Insight describes those “aha!” moments in the work—places in which you come to deeper realizations about your life, the lives of others, and the world at large.

Now, insight doesn’t need to be some massive, culture-transforming realization. Many moments of insight are found in small interactions and quiet moments.

For example, In the above essay by Sandra Cisneros, her moments of insight come from connecting her upbringing to her struggle as an only daughter. While her childhood was often lonely and disappointing, she realizes in hindsight that she’s lucky for that upbringing: it helped nurture her spirit as a writer, and it helped her pursue a career in writing. These moments of gratitude work as insight, allowing her to appreciate what once seemed like a burden.

When we reach the end of the essay, and Cisneros describes how she felt when her father read one of her stories, we see what this gratitude is building towards: love and acceptance for the life she chose.

5. Literary Devices

The personal narrative essay, as well as all forms of creative writing, uses its fair share of literary devices . These devices don’t need to be complex: you don’t need a sprawling extended metaphor or an intricate set of juxtapositions to make your essay compelling.

However, the occasional symbol or metaphor will certainly aid your story. In Mary Oliver’s essay “Flow,” the author uses literary devices to describe the magnificence of the ocean, calling it a “cauldron of changing greens and blues” and “the great palace of the earth.” These descriptions reinforce the deep beauty of the earth.

In Sandra Cisneros’ essay “Only Daughter,” the author employs different symbols to represent her father’s masculinity and sense of gender roles. At one point, she lists the few things he reads—sports journals, slasher magazines, and picture paperbacks, often depicting scenes of violence against women. These symbols represent the divide between her father’s gendered thinking and her own literary instincts.

More Narrative Essay Examples

Let’s take a look at a few more narrative essay examples. We’ll dissect each essay based on the five fundamentals listed above.

Narrative Essay Example: “Letting Go” by David Sedaris

Read “Letting Go” here in The New Yorker .

Sedaris’ essay dwells on the culture of cigarette smoking—how it starts, the world it builds, and the difficulties in quitting. Let’s analyze how this narrative essay example uses the five fundamentals of essay writing.

- Thesis: There isn’t an explicitly defined thesis, which is common for essays that are meant to be humorous or entertaining. However, this sentence is a plausible thesis statement: “It wasn’t the smoke but the smell of it that bothered me. In later years, I didn’t care so much, but at the time I found it depressing: the scent of neglect.”

- Personal Experience: Sedaris moves between many different anecdotes about smoking, from his family’s addiction to cigarettes to his own dependence. We learn about his moving around for cheaper smokes, his family’s struggle to quit, and the last cigarette he smoked in the Charles de Gaulle airport.

- Meaning from Chaos: Sedaris ties many disparate events together. We learn about his childhood and his smoking years, but these are interwoven with anecdotes about his family and friends. What emerges is a narrative about the allure of smoking.

- Insight: Two parts of this essay are especially poignant. One, when Sedaris describes his mother’s realization that smoking isn’t sophisticated, and soon quits her habit entirely. Two, when Sedaris is given the diseased lung of a chain smoker, and instead of thinking about his own lungs, he’s simply surprised at how heavy the lung is.

- Literary Devices: Throughout the essay, Sedaris demonstrates how the cigarette symbolizes neglect: neglect of one’s body, one’s space, and one’s self-presentation.

Narrative Essay Example: “My Mother’s Tongue” by Zavi Kang Engles

Read “My Mother’s Tongue” here in The Rumpus .

Engles’ essay examines the dysphoria of growing up between two vastly different cultures and languages. By asserting the close bond between Korean language and culture, Engles explores the absurdities of growing up as a child of Korean immigrants. Let’s analyze how this narrative essay example uses the five fundamentals of essay writing.

- Thesis: Engles’ essay often comes back to her relationship with the Korean language, especially as it relates to other Korean speakers. This relationship is best highlighted when she writes “I glowed with [my mother’s] love, basked in the warm security of what I thought was a language between us. Perhaps this is why strangers asked for our photos, in an attempt to capture a secret world between two people.”This “secret world” forms the crux of her essay, charting not only how Korean-Americans might exist in relation to one another, but also how Engles’ language is strongly tied to her identity and homeland.

- Personal Experience: Engles writes about her childhood attachment to both English and Korean, her adolescent fallout with the Korean language, her experiences as “not American enough” in the United States and “not Korean enough” in Korea, and her experiences mourning in a Korean hospital.

- Meaning from Chaos: In addition to the above events, Engles ties in research about language and identity (also known as code switching ). Through language and identity, the essay charts the two different cultures that the author stands between, highlighting the dissonance between Western individualism and an Eastern sense of belonging.

- Insight: There are many examples of insight throughout this essay as the author explores how out of place she feels, torn between two countries. An especially poignant example comes from Engles’ experience in a Korean hospital, where she writes “I didn’t know how to mourn in this country.”

- Literary Devices: The essay frequently juxtaposes the languages and cultures of Korea and the United States. Additionally, the English language comes to symbolize Western individualism, while the Korean language comes to symbolize Eastern collectivism.

Narrative Essay Example: 3 Rules for Middle-Age Happiness by Deborah Copaken

Read “3 Rules for Middle-Age Happiness” here in The Atlantic .

Copaken’s essay explores her relationship to Nora Ephron, the screenwriter for When Harry Met Sally . Let’s analyze how this narrative essay example uses the five fundamentals of essay writing.

- Thesis: This essay hands us the thesis statement in its subtitle: “Gather friends and feed them, laugh in the face of calamity, and cut out all the things—people, jobs, body parts—that no longer serve you.”

- Personal Experience: Copaken weaves two different threads through this essay. One thread is her personal life, including a failing marriage, medical issues, and her attempts at building a happy family. The other is Copaken’s personal relationship to Ephron, whose advice coincides with many of the essay’s insights.

- Meaning from Chaos: This essay organizes its events chronologically. However, the main sense of organization is found in the title: many of the essayist’s problems can be perceived as middle-aged crises (family trouble, divorce, death of loved ones), but the solutions to those crises are simpler than one might realize.

- Insight: In writing this essay, Copaken explores her relationship to Ephron, as well as Copaken’s own relationship to her children. She ties these experiences together at the end, when she writes “The transmission of woes is a one-way street, from child to mother. A good mother doesn’t burden her children with her pain. She waits until it becomes so heavy, it either breaks her or kills her, whichever comes first.”

- Literary Devices: The literary devices in this article explore the author’s relationship to womanhood. She wonders if having a hysterectomy will make her “like less of a woman.” Also important is the fact that, when the author has her hysterectomy, her daughter has her first period. Copaken uses this to symbolize the passing of womanhood from mother to daughter, which helps bring her to the above insight.

How to Write a Narrative Essay in 5 Steps

No matter the length or subject matter, writing a narrative essay is as easy as these five steps.

1. Generating Narrative Essay Ideas

If you’re not sure what to write about, you’ll want to generate some narrative essay ideas. One way to do this is to look for writing prompts online: Reedsy adds new prompts to their site every week, and we also post writing prompts every Wednesday to our Facebook group .

Taking a step back, it helps to simply think about formative moments in your life. You might a great idea from answering one of these questions:

- When did something alter my worldview, personal philosophy, or political beliefs?

- Who has given me great advice, or helped me lead a better life?

- What moment of adversity did I overcome and grow stronger from?

- What is something that I believe to be very important, that I want other people to value as well?

- What life event of mine do I not yet fully understand?

- What is something I am constantly striving for?

- What is something I’ve taken for granted, but am now grateful for?

Finally, you might be interested in the advice at our article How to Come Up with Story Ideas . The article focuses on fiction writers, but essayists can certainly benefit from these tips as well.

2. Drafting a Narrative Essay Outline

Once you have an idea, you’ll want to flesh it out in a narrative essay outline.

Your outline can be as simple or as complex as you’d like, and it all depends on how long you intend your essay to be. A simple outline can include the following:

- Introduction—usually a relevant anecdote that excites or entices the reader.

- Event 1: What story will I use to uphold my argument?

- Analysis 1: How does this event serve as evidence for my thesis?

- Conclusion: How can I tie these events together? What do they reaffirm about my thesis? And what advice can I then impart on the reader, if any?

One thing that’s missing from this outline is insight. That’s because insight is often unplanned: you realize it as you write it, and the best insight comes naturally to the writer. However, if you already know the insight you plan on sharing, it will fit best within the analysis for your essay, and/or in the essay’s conclusion.

Insight is often unplanned: you realize it as you write it, and the best insight comes naturally to the writer.

Another thing that’s missing from this is research. If you plan on intertwining your essay with research (which many essayists should do!), consider adding that research as its own bullet point under each heading.

For a different, more fiction-oriented approach to outlining, check out our article How to Write a Story Outline .

3. Starting with a Story

Now, let’s tackle the hardest question: how to start a narrative essay?

Most narrative essays begin with a relevant story. You want to draw the reader in right away, offering something that surprises or interests them. And, since the essay is about you and your lived experiences, it makes sense to start your essay with a relevant anecdote.

Think about a story that’s relevant to your thesis, and experiment with ways to tell this story. You can start with a surprising bit of dialogue , an unusual situation you found yourself in, or a beautiful setting. You can also lead your essay with research or advice, but be sure to tie that in with an anecdote quickly, or else your reader might not know where your essay is going.

For examples of this, take a look at any of the narrative essay examples we’ve used in this article.

Theoretically, your thesis statement can go anywhere in the essay. You may have noticed in the previous examples that the thesis statement isn’t always explicit or immediate: sometimes it shows up towards the center of the essay, and sometimes it’s more implied than stated directly.

You can experiment with the placement of your thesis, but if you place your thesis later in the essay, make sure that everything before the thesis is intriguing to the reader. If the reader feels like the essay is directionless or boring, they won’t have a reason to reach your thesis, nor will they understand the argument you’re making.

4. Getting to the Core Truth

With an introduction and a thesis underway, continue writing about your experiences, arguments, and research. Be sure to follow the structure you’ve sketched in your outline, but feel free to deviate from this outline if something more natural occurs to you.

Along the way, you will end up explaining why your experiences matter to the reader. Here is where you can start generating insight. Insight can take the form of many things, but the focus is always to reach a core truth.

Insight might take the following forms:

- Realizations from connecting the different events in your life.

- Advice based on your lived mistakes and experiences.

- Moments where you change your ideas or personal philosophy.

- Richer understandings about life, love, a higher power, the universe, etc.

5. Relentless Editing

With a first draft of your narrative essay written, you can make your essay sparkle in the editing process.

Remember, a first draft doesn’t have to be perfect, it just needs to exist.

Remember, a first draft doesn’t have to be perfect, it just needs to exist. Here are some things to focus on in the editing process:

- Clarity: Does every argument make sense? Do my ideas flow logically? Are my stories clear and easy to follow?

- Structure: Does the procession of ideas make sense? Does everything uphold my thesis? Do my arguments benefit from the way they’re laid out in this essay?

- Style: Do the words flow when I read them? Do I have a good mix of long and short sentences? Have I omitted any needless words ?

- Literary Devices: Do I use devices like similes, metaphors, symbols, or juxtaposition? Do these devices help illustrate my ideas?

- Mechanics: Is every word spelled properly? Do I use the right punctuation? If I’m submitting this essay somewhere, does it follow the formatting guidelines?

Your essay can undergo any number of revisions before it’s ready. Above all, make sure that your narrative essay is easy to follow, every word you use matters, and that you come to a deeper understanding about your own life.

Above all, make sure that your narrative essay is easy to follow, every word you use matters, and that you come to a deeper understanding about your own life.

Next Steps for Narrative Essayists