Stephen King Revisited

Essays, memories, and even a little history…, what we talk about when we talk about horror by bev vincent.

After losing his job at Doubleday, Bill Thompson moved to Everest House, but he and King remained good friends, going to lunch and attending baseball games together. In November 1978, Thompson approached King about the possibility of doing a book about horror in movies, television and radio over the previous thirty years. Since it would be a work of non-fiction, King wouldn’t have to offer it to his fiction publisher, NAL.

The concept intrigued King, but he wasn’t enthusiastic about the project at first. It intimidated him. It was easier to tell lies in fiction than write the truth in non-fiction, he thought. It wouldn’t be his first time writing about the nature of fear and why people want to be scared by something entertaining, though. He’d prepared a long forward on the subject in Night Shift , for example.

Thompson was persistent and persuasive. He asked King how often he had been asked why he wrote horror and why people read horror. If he wrote this book, King would never have to answer those kinds of questions again, Thompson argued. All he’d have to do is say, “I wrote this book.” It would be his “Final Statement” on the matter.

The timing was right, too. The night of Thompson’s call, he was working on the syllabus for a class called “Themes in Supernatural Literature” he would be teaching the next semester. The class gave him the ideal platform to work out some of his ideas on the topic, with his students challenged his thinking on some subjects. He was also influenced by a lecture given by his former University of Maine professor, Burton Hatlen, on Stoker and Dracula , a book that King admitted had occupied his mind while on vacation in St. Thomas that winter.

King said later that he found it a very difficult book to write. It involved a lot of research, but he didn’t want it to look that way in the final product. He interviewed—by letter—the authors whose novels he focused on in the chapter on Horror Fiction. Some of the material was “repurposed” from previously published writing, including the essays “The Fright Report” ( Oui ) and “The Third Eye” ( The Writer ), introductions to Night Shift , and an omnibus edition of classic horror novels, and an article about Ramsey Campbell from Whispers magazine.

The topic could take years to explore if he included the origins of horror in the earliest writings, he realized, so together he and Thompson decided to limit the scope to the previous thirty years or so, ending in 1980. He chose the fifties as his starting point because there were no horror books or movies to speak of in the forties. The fifties also was the beginning of his personal experience as someone appreciating the genre.

One aspect of the book that surprised people is the “annoying autobiographical pause,” the first time King had written about himself at length. This part came about because of the inevitable Freudian questions about what happened in his childhood to make him the way he was.

The list of books and films at the end of Danse Macabre came about as a result of a late-night drinking session at the U.N. Plaza Hotel [1] in New York and another at a pub in North Lovell, Maine with his agent, Kirby McCauley.

Danse Macabre was published in April 1981 with a first printing of 60,000 copies. There was also a numbered edition signed by King, limited to 250 copies.[2]

[1] A location that should be familiar to Dark Tower fans: it’s where Mia went to await a call from Richard Sayre in Song of Susannah .

[2] King subsequently asked Dennis Etchison to comb the published book for errors, which were corrected in the 1983 paperback version, along with any mistakes reported by hundreds of readers. This edition also contains a new “Forenote to the Paperback Edition.” The 2010 edition of the book has both introductions and an additional essay entitled “What’s Scary” that originally appeared in Fangoria magazine.

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

15 comments

I love this book. Probably the one I dip into the most. I’ve been trying to watch the film list for years, but some of the films have been tricky to track down.

I got this book right after it came out and have read it at least 4 times. I love it!

Bev, Any idea on how many copies of Dance Macabre have been sold to date?

No, sorry — I don’t keep track of such things. I doubt anyone really does.

I discovered so many great horror fiction novels by reading Danse Macabre! Loved King’s in-depth discussions on Harlan Ellison, Richard Matheson; and two of my all-time favorite novels, “The Haunting of Hill House, and “The House Next Door.” I’ve read my paperback edition of “Danse Macabre” to tatters.

Mark me down as a lover of this book too! It’s a great history of the horror genre and a good reference guide for those new to it.

I’m also doing going though Stephen King Re-visited this year. (Currently on ‘It.’) Danse and On Writing are the only two King books I hadn’t previously read. Didn’t care much for Danse – perhaps because most of the fiction talked about I am too young to appreciate?

in DANSE MACABRE King wrote about a television episode written by William Hope Hodgson called “THE THING IN THE WEEDS” of which there is no mention on IMDB. But i am still intrigued, wondering if anyone knows how to find this

He mentioned an adaptation of the WHH story, which you can find here. http://www.strangeark.com/cryptofiction/thing-weeds.html Some of WHH’s stories were in Alfred Hitchock Presents… anthologies — King may have misremembered the details in this case.

I’m a big fan of this book, too. I’ve been trying to collect the film list at the back off and on for about twenty years with moderate success. I love his observations about terrible movies. The Robot Monster anecdote is hilarious!

I’ve only been able to see some of them recently thanks to YouTube. I can’t imagine trying to collect them!

Ebay has been a big help. Some are only available on old used VHS copies. There are a handful that I’ve had no luck whatsoever in tracking down.

Great Essay Again BEV! would you by chance have the ISBN # of the first paperback edition with the corrected errors/changes? now i have to have that copy, along with my signed limited and first first hardback (flatsigned).

Keep up the excellent work!

I believe it’s 042506462X

Another great essay BEV! My paperback edition of “Danse Macabre” is still in pretty good shape, and it is a wonderful history of horror genre. I love it!!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

According to Stephen King, This Is Why We Crave Horror Movies

The horror king breaks down our obsession with the macabre.

Stephen King and horror are synonymous. Are you really able to call yourself a fan of horror if one of his novels or film adaptations isn't among your top favorites? The Maine-born writer is hands down the most successful horror writer and one of the most beloved and prolific writers ever whose legacy spans generations. Without King, we might not be as terrified of clowns and or think twice about bullying the shy girl in school. One could say that King has earned the moniker, "the King of Horror." In addition to all he's written, King has also had over 60 adaptations of his work for television and the big screen and has written, produced, and starred in films and shows as well. He has fully immersed himself in the genre of horror from all sides, and it's unlikely that we will ever have anyone else like Stephen King. But did you know that King wrote an essay that was published in Playboy magazine about horror movies?

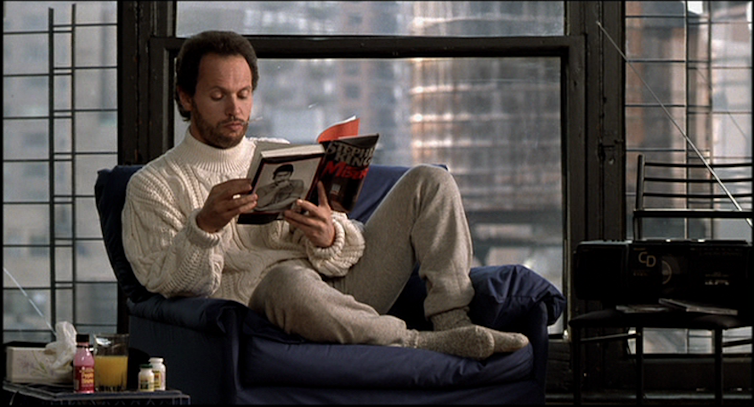

In 1981, King's essay titled " Why We Crave Horror Movies " was published in Playboy magazine as a variation of the chapter " The Horror Movie As Junk Food" in Danse Macabre . Danse Macabre was published in 1981 and is one of the non-fiction books in which that wrote about horror in media and how our fears and anxieties have been influencing the horror genre. The full article that was published is no longer online, but there is a shortened four-page version of it that can be found.

RELATED: The Iconic Horror Movie You Won't Believe Premiered at Cannes

Stephen King Believes We Are All Mentally Ill

The essay starts out guns blazing, the first line reading "I think that we're all mentally ill; those of us outside the asylums only hide it a little bit better." From here, he describes the general behaviors of people we know and how mannerisms and irrational fears are not different between the public and those in asylums. He points out that we pay money to sit in a theater and be scared to prove a point that we can and to show that we do not shy away from fear. Some of us, he states, even go watch horror movies for fun, which closes the gap between normalcy and insanity. A patron can go to the movies, and watch someone get mutilated and killed, and it's considered normal, everyday behavior. This, as a horror lover, feels very targeted. I absolutely watch horror movies for fun and I will do so with my bucket of heart-attack-buttered popcorn and sip on my Coke Zero. The most insane thing about all of that? The massive debt accumulated from one simple movie date.

Watching Horror Movies Allows Us to Release Our Insanity

King states that we use horror movies as a catharsis to act out our nightmares and the worst parts of us. Getting to watch the insanity and depravity on the movie screen allows us to release our inner insanity, which in turn, keeps us sane. He writes that watching horror movies allows us to let our emotions have little to no rein at all, and that is something that we don't always get to do in everyday life. Society has a set of parameters that we must follow with regard to expressing ourselves to maintain the air of normalcy and not be seen as a weirdo. When watching horror movies, we see incredibly visceral reactions in the most extreme of situations. This can cause the viewer to reflect on how they would react or respond to being in the same type of situation. Do we identify more with the victim or the villain? This poses an interesting thought for horror lovers because sometimes the villain is justified. Are we wrong for empathizing with them instead?

Let's take a look at one of the more popular horror movies of recent years. Mandy is about a woman who is murdered by a crazed cult because she is the object of the leader's obsession. This causes Red ( Nicolas Cage ) to ride off seeking revenge for the love of his life being murdered. There are also movies like I Spit On Your Grave and The Last House On The Left where the protagonist becomes the murderer in these instances because of the trauma they experienced from sexual assault. Their revenge makes audiences a little more willing to side with the murderer because they took back their power and those they killed got what was deserved. This is where that Lucille Bluth meme that says "good for her" is used. I'll die on the hill that those characters were justified and if that makes me mentally ill then King might be right!

What Does Stephen King Mean When He Tells Us to "Keep the Gators" Fed?

At the end of the essay, King mentions he likes to watch the most extreme horror movies because it releases a trap door where he can feed the alligators. The alligators he is referring to are a metaphor for the worst in all humans and the morbid fantasies that lie within each of us. The essay concludes with "It was Lennon and McCartney who said that all you need is love, and I would agree with that. As long as you keep the gators fed." From this, we can deduce that King feels we all have the ability to be institutionalized, but those of us that watch horror movies are less likely because the sick fantasies can be released from our brains.

With that release, we can walk down the street normally without the bat of an eye from walkers-by. Perhaps this is why the premise for movies like The Purge came to fruition. A movie where for 24 hours all crime, including murder, is decriminalized couldn't have been made by someone who doesn't get road rage or scream into the void. It was absolutely made by someone who waited at the DMV for too long or has had experience working in retail around Black Friday. With what King is saying, The Purge is a direct reflection of that catharsis. Not only are you getting to watch a crazy horror movie where everyone is shooting everyone and everything is on fire, but it's likely something you've had a thought or two about. You can consider those gators fed for sure.

Do Horror Movies Offer Us True Catharsis or Persuasive Perspective?

Catharsis as a concept was coined by the philosopher Aristotle . He explained that the performing arts are a way to purge negative types of emotions from our subconscious, so we don't have to hold onto them anymore. This viewpoint further perpetuates what King is trying to explain. With that cathartic relief, the urgency to act on negative emotion is less likely to happen because there is no build-up of negativity circling the drain from our subconscious to our reality. However, some who read the essay felt like King was just being persuasive and using fancy imagery rather than identifying an actual reason why horror is popular. Some claim the shock and awe factor of his words and his influence on horror would cause some readers to believe they are mentally ill deep down. I have to say, as a millennial who rummages through the ends of social media multiple times a day, everyone on the internet thinks they're mentally ill, and we all have the memes to prove it. It is exciting and fascinating to watch a horror movie after working a 9-5 job where the excitement is low. Watching Ghostface stalk Sidney Prescott ( Neve Campbell ) in Scream isn't everyone's idea of winding down, but for the last 20-something years, it has been my comfort movie when I'm feeling sad or down. The nostalgia of Scream is what makes it feel cathartic to me and that's free therapy!

What is the Science Behind Loving Horror Movies?

Psychology studies will tell us that individuals who crave and love horror are interested in it because they have a higher sensation-seeking trait . This means they have a higher penchant for wanting to experience thrilling and exciting situations. Those with a lower level of empathy are also more likely to enjoy horror movies as they will have a less innate response to a traumatic scene on screen. According to the DSM-V , a severe lack of empathy could potentially be a sign of a more serious psychological issue, however, the degree of severity will vary. I do love rollercoasters, but I also cry when I see a dog that is just too cute, so horror lovers aren't necessarily the unsympathetic robots that studies want us to be. Watching horror films can also trigger a fight-or-flight sensation , which will boost adrenaline and release endorphins and dopamine in the brain. Those chemicals being released make the viewers feel accomplished and positive, relating back to the idea that watching horror movies is cathartic for viewers.

Anyone who reads and studies research knows that correlation does not imply causation, but whether King's perspective is influenced by his position in the horror genre or not, psychology and science can back up the real reasons why audiences love horror movies. As a longtime horror lover and a pretty above-average horror trivia nerd, I have to wonder if saying we are mentally ill is an overstatement and could maybe be identified more as horror lovers seeking extreme stimulus. Granted, this essay was written over 40 years ago, so back then liking horror wasn't as widely accepted as it is today. It's possible that King felt more out of place for his horror love back then and the alienation of a fringe niche made him feel mentally ill. Is King onto something by assuming that everyone has mental illness deep down, or is this a gross overestimation of the human psyche? The answer likely falls somewhere in between, but those that love horror will continue to release that catharsis through the terrifying and the unknown because it's a scream, baby!

Friday essay: in praise of the ‘horror master’ Stephen King

Lecturer in Communications and Media, University of Notre Dame Australia

Disclosure statement

Ari Mattes does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The University of Notre Dame Australia provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

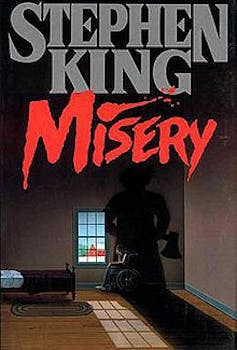

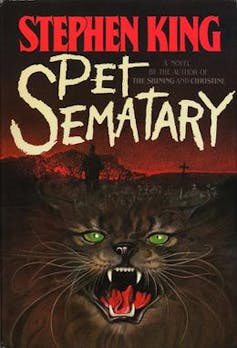

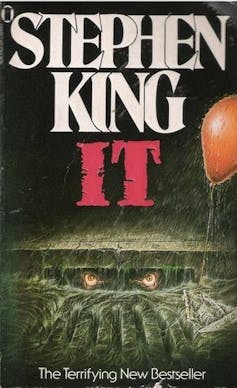

Growing up in the 1980s, the name Stephen King was synonymous with macabre, terrifying, apparently taboo (though ubiquitous) book covers. They seemed to appear everywhere: bookstores, to be sure; but also newsagents, supermarkets, cinemas, airports and libraries. They always seemed to be spinning in some library carousel, looking tattered, like they’d been borrowed 100,000 times.

Like a kid from a King novel, I was obsessed with the forbidden. I would spend hours staring at these book covers, thinking about the horrors that might lie within.

A giant, bloody salivating dog. A freakish pair of eyes looking out of a drain. A silhouette of a figure with an axe eclipsing someone in a wheelchair. Hell, they looked more like movie posters than book covers. I’d go to bed and imagine one of these figures coming alive and creeping towards the house from the backyard.

Very occasionally, this was actually scary – but mostly it was just fun.

Why we love horror

Why do we gravitate towards subject matter that, if it existed in the real world, would be at best supremely unpleasant? There are many theories regarding why people love horror film and literature.

Perhaps it’s cathartic. Maybe it reflects Freud’s “ death drive ,” or what Edgar Allan Poe described, in a titular short story, as the “imp of the perverse,” (suggesting we all have self-destructive tendencies). Or maybe it simply reflects our fascination with extreme experiences, a desire to be overwhelmed by the sublime, which Edmund Burke defined as a mixture of fear and excitement, terror and awe. Perhaps horror thus manifests a desire to re-enchant the world with magic in a controlled and safe context, physically activating the body and its response mechanisms in an environment that only simulates real peril.

Friedrich Nietzsche wrote about the collective pleasure of inflicting pain on others through punishment. Does our fascination for horror channel this? Or, as Julia Kristeva ’s theory suggests, does art help us manage our abject horror at the breakdown between self and other – most pointedly captured in our confrontations with corpses?

Literary theorist René Girard ’s ideas are equally compelling. Perhaps we’re attracted to images of violence because of its anthropological function in the earliest periods of community formation. A victim – the scapegoat – would be chosen to bear the violence that would otherwise be destructively directed towards other members of the community. This idea is beautifully rendered in Drew Godard’s The Cabin in the Woods , a horror film about the origins of horror films in ritual and sacrifice.

In a broader cultural sense, our modern interest in horror, the supernatural and the weird has grown in direct proportion to industrialisation, and the parallel shrinking of the world’s magic and mysteries (captured in the term “globalisation”).

In a post-sacred era of intense scientific rationalism and technological development, the aesthetics of the weird, supernatural and horrific – in all their wondrous irrationality – allow us to occupy an alternate, imaginary space removed from the horror of things as they really are: mass industrial wars of attrition, precarious states of living, pandemic disease and global warming.

Read more: Friday essay: scary tales for scary times

My first King

When I finally had the autonomy (and my own money) to pick the books I wanted to read, it was with mixed feelings of shame and excitement that I went to buy my first Stephen King novel.

I still remember the suburban bookstore and the sardonic frown of its middle-aged clerk as she looked down at my ten-year-old self when I placed Pet Sematary on the counter and got 12 bucks out of my wallet. I remember blushing when she intimated (or was it actually a question?) I must have been buying this for an older relative.

The novel follows what happens to a doctor and his family when they discover, in the woods, a children’s pet cemetery that reanimates whatever is buried there. It lived up to the promise of its cover, offering splashes of superlative gore, a handful of genuinely terrifying moments (the sequences involving Rachel’s sick sister Zelda still get to me) and a plethora of new words. Not swear words, mind you – any self-respecting kid knows all of these by seven or eight – but terms like “cuckold”, about which I had to consult my mum.

For the next two years, I spent most of my reading time dedicated to King. I quickly got through the pantheon – massive tomes like The Stand , Needful Things and It ; more moderately sized ones like Carrie , The Shining and Salem’s Lot ; and short, explosive ones like The Running Man , published under King’s pseudonym, Richard Bachman. And then I started with the new releases (there was at least one every year – like 1994’s Insomnia ), generally available from Kmart in hardback.

I found in King an interlocutor who spoke with gusto and enthusiasm about all kinds of things – old age, domestic abuse, natural and supernatural horrors of the mind and closet. But, more than anything else, he seemed not only to write stories that often featured young characters, but to accurately dramatise what it actually felt like to be a kid.

Short stories like The Sun Dog , novels like Cycle of the Werewolf and the monumental It – not to mention more obvious outings like The Body, the basis of the massively successful nostalgia film Stand By Me – captured the peculiar melancholic excitement, both intense and slightly wistful, of being near the beginning of life in that delirious halcyon era just before puberty sets in.

Then I grew up – and stopped reading King. Through writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Jane Austen, I was introduced to prose worlds that seemed to be richer: both more concentrated and more expansive, certainly more nuanced. King gradually disappeared from my field of vision.

I forgot about the “gypsy” curse on Billy Halleck (the basis of Thinner ) and about Arnie and Dennis from Christine , as they struggle to overcome the eponymous evil car. Like one of the children of It – who forget their childhoods, until they reunite as adults to confront them – I forgot about my horror master, erasing my childhood experiences from memory. When I was 15, as a gag, I tried reading Firestarter and found it garish, gross, infantile. A few years earlier, King’s novel about a pyrokinetic child being hunted by a government who want to weaponise her would have seemed thrilling, maybe even insightful.

But the King was dead.

Read more: 'Supp'd full with horrors': 400 years of Shakespearean supernaturalism

Literary snobs and good writers

Perhaps the only thing worse than the literary snob who looks down on everyone who doesn’t read Joyce’s Ulysses on loop is the literary snob of the populist variety, the one who scowls at everyone who doesn’t read the kind of fiction that ord’nary folks like.

When outspoken literary critic and professor Harold Bloom described the 2003 awarding of the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters to Stephen King as “another low in the shocking process of dumbing down our cultural life,” it was easy to dislike Bloom as an example of the former. Listening to King discuss his writing, it is almost as easy to dismiss him as the latter.

What makes a good writer? According to King,

If you wrote something for which someone sent you a check, if you cashed the check and it didn’t bounce, and if you then paid the light bill with the money, I consider you talented.

So is King, as Bloom writes, “an immensely inadequate writer on a sentence-by-sentence, paragraph-by-paragraph, book-by-book basis”? King does, after all, describe his own work as “the literary equivalent of a Big Mac and a large fries from McDonald’s”. And there are numerous passages throughout his work – probably most pronouncedly in the words of writer Bill Denbrough in It – in which King expresses a serious disdain for academic knowledge and scholarship.

As Bloom would probably argue, consistency in style and tone, and complexity of form, are key elements underpinning any kind of aesthetic mastery. And it’s undeniable that King has produced a not-inconsiderable volume of poorly written and inconsistent work. Sometimes his novels warrant criticisms of pretentiousness, hackneyed style and tediously repetitive prose.

King may or may not be a great, or even good, writer. His more self-consciously serious stuff sometimes seems intolerable to me: kitsch is only fun if the attitude is fun. And some of his work ( Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption and Dolores Claiborne , for example) feels heavy-handed to the point of being virtually unreadable. Never mind – these works are frequently adapted into incredibly popular and incredibly dull films.

In any case, the debate continues to play out, with critics intermittently arguing for and against King’s writing. Dwight Allen, for example, wrote in the Los Angeles Review of Books that King creates one-dimensional characters in dull prose. In the same publication, Sarah Langan responded :

All of [King’s] novels, even the stinkers, have resonance. […] his fiction isn’t just reflective of the current culture, it casts judgement. […] No one except King challenges [Americans] so relentlessly, to be brave. To kill our monsters.

King is, undeniably, a juggernaut of commercial literary production – an industry unto himself, a literary and cinematic brand – who has written a handful of genuine horror genre masterpieces throughout his career.

Perhaps it’s in part this combination of prolific volume and intermittent brilliance that keeps me, like an addict, coming back for more.

Ultimately, though, I would suggest I like reading King for the same reason so many others do, a reason that accounts for his enduring popularity when better horror stylists (King’s contemporaries Clive Barker and Peter Straub , for example) have fallen by the wayside. And that’s his unprecedented capacity to tap into nostalgia.

Returning to King-world

Nearly 20 years after I gave up on Stephen King, in one of those random nostalgic moments that seem to populate his fictional world, my brother gave me Revival for Christmas.

King’s Frankensteinian novel, published in 2014, is about the aftermath of an encounter between a young boy and a Methodist minister fascinated by electricity. After years of mainly reading what is sometimes pretentiously called “literary” fiction, and mostly avoiding anything written after the 19th or very early 20th centuries, I returned to King-world.

And I was dazzled by what I found there, realising what I must have known as a kid: King is a superb storyteller. Much of his work is characterised by an infectiously energetic prose style, governed by a flair for simple but satisfying plotting and a supremely inventive imagination.

And – yep – I was stunned by his capacity to precisely render in prose, perhaps more acutely than any other contemporary writer, the confusing, often hokey and melodramatic, but always exciting images, emotions, and sensibilities of youth.

I realised there’s something brilliant, and totally inimitable, about King. Despite his work’s sometimes kitsch silliness (a hazard of the horror genre), despite the not uncommon misfires – and despite the absurdly voluminous output - King is able to authentically generate an atmosphere of nostalgia that taps into something at the very core of the pleasure of reading.

Read more: Frankenstein: how Mary Shelley's sci-fi classic offers lessons for us today about the dangers of playing God

It: a masterpiece of nostalgia

His novel It is a case in point: a masterclass in narrative development through a nostalgic structure.

It – for anyone who hasn’t read it, or seen one of the three film adaptations – cuts between the adult lives and childhoods of a group of misfits, the “ Losers Club ”, who collectively band together to fight the evil of their town, Derry. That evil takes the form of a shape-shifting clown, Pennywise.

The Losers Club battled and banished Pennywise as kids, but now “it” has come back. The club members return from around the world to live up to their childhood promise: that if “it” ever returns, they, too, will return to fight “it”. The narrative cuts between characters, en route to Derry, as they recall forgotten passages from their childhood “it’s” return has forced them to remember.

So, the novel is structured around a nostalgic trope: adults literally remembering and reconstructing their childhood in the present. At the same time, the town Derry is developed by King according to a quintessentially nostalgic image of the American small town, recalling peak 1950s Americana. Think Grease : soda fountains, switchblades and quiffs. But behind closed doors, fathers abuse daughters, mothers keep their children sick, and a monster that assumes the form of whatever demon most terrifies you stalks the streets, killing and eating children.

The narrative architecture is starkly simple, sustaining a profound sense of dread in the reader. The characters remember a dreadful past, in a present-future they wish had never materialised. Perhaps nostalgia always contains shades of the dreadful, given its suggestion that one’s future is foreclosed, that all we have are memories of a better time: memories that only exist as memories.

In some of King’s work – Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption, for example – nostalgia acts mainly as window dressing, functioning primarily as an aesthetic. But in It, nostalgia is neither incidental nor benign: it’s a way of exploring the impossibility of having to remember trauma .

Memory appears inevitably nostalgic, because it involves, for the characters, narrative reconstruction of childhood in the present. In the Derry library, for town librarian Mike Hanlon – the only Loser to remain in Derry as an adult (and the only one who didn’t battle It in the sewers as a child) - for example. Or for Ben Hanscom, an internationally successful architect, once the fat kid of the group, who flies back to Derry, drunk and asleep in first-class.

In this way, the novel functions as a kind of treatise on narrative itself. A grab bag of clichés from the horror playbook become legitimately terrifying for the children in the novel - they’re kids after all, and the cultural worlds of kids are often constructed around clichés – from mass-produced popular figures like the Wolf Man, to figures associated with the characters’ nightmarish personal traumas.

It’s a “coming of age” story with a vengeance - a metatext on the horrors of youth, of fitting in, metamorphosing into adulthood, and breaking free of one’s parents - and it inherently explores the ways we use horror stories (like fairytales) to come to terms with this.

As Adrian Daub, revisiting the novel on its 30-year anniversary, wrote in the Los Angeles Review of Books in 2016:

Anamnesis — remembering — is the central structuring device of It’s parallel plots: characters have to find out what they once did, and confront what on some level they already know. […] Perhaps all the kids who devoured It in the ’80s sensed that King had made their pre-adolescent mode of experiencing the world — that unique combination of vivid clarity and forgetfulness — its formal principle. […] All the friends, events, images, and feelings that we ever-so-gently cover in sand as we stumble into adulthood can startle us when we come face to face with them again, and these are the true source of It’s terror. What else have we hidden back there, we wonder uneasily?“

In It’s truly weird (over)length, in It’s oscillating moments of genius and stupidity, in It’s ambition – as King’s horror book about horror, the horror book to end all horror books – it is an American masterpiece. It captures everything incisive, deluded, cruel and sentimental about the popular American literary imagination.

Read more: Why do we find it so hard to move on from the 80s?

Reading as escape and connection

So why is nostalgia such a powerful affect in It, and in King’s work in general?

I think it taps into something at the heart of the process of reading novels. We sit with a novel and retreat from the world: an intensely solipsistic act. A novel sweeps us up into a fantasy image of things (no matter how distant or close to reality) and makes us feel, in our solitude, excitement about what’s to come – but also a faint melancholy in remembering we will soon have to leave this world.

It’s no surprise many people cry at the end of novels: we’ve made such a personal investment, then that world simply disappears, and all we’re left with are our memories of it. In our desire to return to this pleasurable state, we may feel compelled to borrow – or buy – another book.

But while reading a novel feels like a private act (as opposed to going to a movie or concert), there’s also always a sense we are connected to (and connecting with) some kind of cultural and historical continuum.

We read Dickens in our solitude, yet imagine we’re in Victorian England, connected across 150-odd years. Time and space seem collapsed into a vibrant, active present. Dickens speaks to us, but more significantly, the zeitgeist addresses us in a moving presence – perhaps we can cheat death, after all?

The structure of It (and much of King’s other work) reproduces what attracts many of us to reading fiction in the first place – an escape into a present that is at the same time a kind of memory-fantasy, governed by lingering nostalgia.

For Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch , literature offers a utopian space in which we can transcend and transform the past and future, captured in the figure of heimat (meaning homeland – and appropriated in opposition to the term’s German nationalist use). Literature allows us to return to a mythic-nostalgic image of "home” – which we know has never actually existed. This nostalgic space opens the possibility of a better collective present and future.

Read more: The psychology behind why clowns creep us out

Long live the King!

There are definitely better, more controlled stylists than King in popular horror fiction. But their work is somehow more forgettable. King’s perpetual presence - as ringmaster, as media conglomerate, as relentless worker – is always in performance in his work.

You may find his style annoying, or his narratives hokey, but you will always recognise them as Stephen King. He has a flavour, and it ties his work together, good and bad. Much of it emanates from the man himself and his sheer love of writing and reading – dare I say it, of “literature”.

This is evident in his publishing history, but also in the forewords and reviews, and endorsements, he writes for writers he loves. The revival of interest in noir master Jim Thompson , for example, who had vanished into obscurity, seems to be at least in part down to King’s forewords to several of his books. And one wonders how much the Hard Case Crime imprint, which publishes hard-boiled crime novels in the flavour of those of the 1950s and 60s, relies on the success of King’s original crime novels written for them. How many forgotten masterpieces of noir literature have been brought back into print because King publishes with Hard Case? How many books have moved because a line from King is featured on the cover?

No other living horror writer has enjoyed King’s longevity. There’s no one whose monsters have lingered quite as long in the popular imagination, and in the imaginations of countless readers like me.

The literature we read as children and adolescents has a profound effect on our cultural and personal formation, shaping our becoming as adults. King’s worlds, where children struggle to shape their futures, draw upon our own, personal nostalgia. But they also tap into a kind of nostalgia that lies at the heart of novelistic pleasure itself.

Horror films and novels situate us in precarious situations - we identify with victims, sense their isolation as monsters attack, and feel their glory when and if the monsters are defeated.

We creep through the worlds of horror, watchful, alert, before returning to the safety of our bedrooms, but we’re always a little sad when we come back: that world may have been dominated by killer birds , or by hellish blood-sucking fiends , but it was an exciting, atmospheric - and beautifully solitary – place.

- Sigmund Freud

- Friday essay

- Edmund Burke

- Stephen King

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Friedrich Nietzsche

- Horror fiction

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Initiative Tech Lead, Digital Products COE

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Consider This from NPR

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Stephen King Has Ruled The Horror Genre For 50 Years. But Is It Art?

A still from 2015, Carrie The Musical , one of the many adaptations from Stephen King's iconic novel which turns 50 this year. Publicity handout from Carrie The Musical hide caption

A still from 2015, Carrie The Musical , one of the many adaptations from Stephen King's iconic novel which turns 50 this year.

Even if you have never read the book, Carrie , you might recognize the bloodbath prom scene from the movie. Published 50 years ago this spring, Carrie was the first novel by Stephen King. Fame, films and devoted fans were quick to follow.

With over 70 novels and 200 short stories to his credit and countless screen adaptations (plus a couple of plays), it's hard to argue that King is a preeminent force in popular fiction. But does he belong on a list of the greatest American writers?

NPR's Scott Detrow speaks with Tony Magistrale, an English professor who has brought King's work into the realm of academia.

For sponsor-free episodes of Consider This, sign up for Consider This+ via Apple Podcasts or at plus.npr.org .

Email us at [email protected] .

This episode was produced by Marc Rivers. It was edited by Jeanette Woods. Our executive producer is Sami Yenigun.

Screen Rant

What scares stephen king the horror author's biggest fears explained.

Stephen King is often asked in interviews what scares him, but his biggest fears are laid out in his work, evolving from childhood fears to dementia.

Stephen King is often asked in interviews what scares him. It's one of those questions that he seems to answer rather grudgingly, despite the fact that he writes horror. Still, his biggest fears are laid out in his work, as well as how they have evolved over the years.

Stephen King has been a popular author of horror since his first novel was published. Carrie came out in 1974 and struck a chord with people. It revolves around a young high school girl with mysterious telekinetic powers. 'Salem's Lot , King's second novel, came out shortly after that, and was about vampires in a small town. This was followed by The Shining , which firmly established King in the horror genre. At the time, his agent warned him about being typecast as a horror writer, but King considered it a compliment and kept writing horror.

Related: The Stephen King Adaptation The Author Should Direct Himself

Over the years, Stephen King has sometimes strayed from the horror genre with his forays into fantasy, science fiction, and mystery. However, his work almost always contains some elements of horror. He has dipped his toes in almost every standard horror trope in some way—such as 'Salem's Lot for vampires, The Stand for apocalyptic fiction, and It for small-town horror —sometimes shaping certain types of horror so that future stories evolve directly from his work. King, as a horror writer, is a master at expressing his fears on the page. As such, to answer the question of what scares Stephen King, looking through his work is a good place to start.

Bad Things Happening To Children

It would be easy to point to King's novel It and say that the horror novelist is afraid of clowns. While it's true he certainly recognizes how scary clowns can be, the real fear he explores in a novel like It is how vulnerable children are and how easily they can succumb to tragedy. In exploring this theme, King was one of the first to point out how children were afraid of clowns, despite what adults might think. In fact, the novel is really about how adults often ignore children and how, ultimately, they are forced to stand up to the horrors of the world on their own.

Bad things happen to children in a lot of King's work. They often have dangerous and unexplained powers, such as Danny Torrance's shine ( The Shining ) that awakens and enhances the evil spirits around him, and Charlie McGee's pyrokinetic powers ( Firestarter ). Inevitably, the attention these powers provoke from the adult world leads to bad times for the children, whether it's the psychotic break of a parent or a shady government agency like The Shop .

Small Town Paranoia

In many of King's works, small-town ignorance and paranoia run rampant, leading to all sorts of problems. Small towns are isolated places and when something happens there, everyone tends to be involved. In 'Salem's Lot , for instance, the master vampire Barlow is able to get away with killing and nearly taking over the community because he now resides in a small town.

Related: Stephen King Theory: Kubrick's Movie Is About The Apollo 11 Moon Landing

In It , the town of Derry is filled with people who are willfully ignorant of the horrible string of murders that take place every 27 years. Another small town featured in several King stories is Castle Rock , which is often beset by supernatural horrors. For instance, in Needful Things shop owner Leland Gaunt manipulates everyone in town until they turn against each other in hurtful and violent ways.

A Global Pandemic

Although King usually explores horror in isolated locations, be it a small town or an empty snowed-in hotel, he did write about horror on a more global scale. The Stand features a flu-like disease that spreads across the United States until the vast majority of the population is dead. King writes in vivid detail about loved ones getting sick and dying to the helpless horror of the Super Flu's few survivors. The Stand is one of King's most important and well-known novels. It also happens to be one of his most relevant in the current global environment with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Being Struck By A Vehicle

Oddly, this may be one of Stephen King's biggest fears. Although it might not seem obvious, there is a theme of vehicular murder running through his work. In the 80s, he wrote his novel, Christine , about a 1958 Plymouth Fury possessed by supernatural forces that goes on a killing spree. That same decade, King wrote and directed Maximum Overdrive , an admittedly terrible movie about killer trucks with a mind of their own.

Related: Why Stephen King Bought The Van That Nearly Killed Him

However, those are the obvious ones. Stephen King's novella, The Body , is about finding a boy's body that's been struck by a train. Similarly, Pet Semetary features one of King's most heartbreaking scenes when a young Gage is hit and killed by a semi. Part of this fear may stem from an event that happened during King's childhood in which a friend of his was hit and killed by a train. Nevertheless, the vehicular horror continued to plague King when he was struck by a van while out on one of his walks and was nearly killed in 1999.

Crazy Fans And Success

As King's horror writing career developed, he began to grow a fear of success. This fear is particularly evident in his 90s work, such as in The Dark Half and Misery . The Dark Half is about a writer's dark pseudonym that comes to life, murdering everyone in his way so the violent novels he writes will continue to be produced. Similarly, Misery features a fan so obsessed with author Paul Sheldon's romance novels that she kidnaps him and forces him to write for her.

Isolation, A Broken Mind, And Dementia

Perhaps one of Stephen King's biggest fears is going crazy and losing his mind. Early in his career, he often wrote about how isolation drove people mad, such as Jack Torrance in The Shining . Similar things happen to various characters through his work as his career progresses, such as Beverly Marsh's father in It . King is aware that sometimes good and well-intentioned people lose themselves and do horrible things.

These days, this fear has grown for King. Now, at 72 years old, his biggest fear is losing his mind to dementia and Alzheimer's. He's spoken about how since he's a writer, he needs a sharp mind. His biggest fear is not being able to create and share his work. As Stephen King told NPR a few years ago, " That's the boogeyman in the closet now. I'm afraid of losing my mind ".

Next: Stephen King Theory: Every Character That Has The Shine

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Stephen King — Analysis of ‘Why We Crave Horror Movies’ by Stephen King

Analysis of 'Why We Crave Horror Movies' by Stephen King

- Categories: Stephen King

About this sample

Words: 1020 |

Published: Apr 8, 2022

Words: 1020 | Pages: 2 | 6 min read

Stephen King's essay, "Why We Crave Horror Movies," delves into the intriguing phenomenon of why people are drawn to horror films. King explores the idea that individuals enjoy challenging fear and demonstrate their bravery by willingly subjecting themselves to scary movies. He suggests that humans have an inherent desire to experience fear and that society has built norms around the acceptable ways to do so, with horror movies being one of those sanctioned outlets.

King ultimately argues that horror movies serve as a release valve for the darker aspects of our psyche, allowing us to maintain a sense of normalcy and societal conformity. He suggests that by indulging in controlled madness within the confines of a movie theater, we can better appreciate the positive emotions and values of our everyday lives.

Throughout the essay, King's thoughts evolve from an exploration of psychological impulses to a nuanced consideration of the ethical and moral dimensions of our fascination with horror. He challenges readers to contemplate the complexities of human nature and the role of horror movies in our society.

Works Cited:

- American Psychological Association. (2021). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.).

- National Geographic. (n.d.). Why we believe in superstitions. http://channel.nationalgeographic.com/channel/taboo/articles/why-we-believe-in-superstitions/

- New World Encyclopedia. (n.d.). Superstition. https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Superstition

- Radford, B. (2016). Superstition: Belief in the age of science. Oxford University Press.

- Rogers, K. (2019). The power of superstition. Scientific American Mind, 30(6), 50-55.

- Sørensen, J. (2014). Superstition in the workplace: A study of a bank in Denmark. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 30(1), 34-42.

- Truzzi, M. (1999). CSIOP Investigates: Superstition and the paranormal. The Scientific Review of Mental Health Practice, 1(1), 174-181.

- Vyse, S. A. (2013). Believing in magic: The psychology of superstition. Oxford University Press.

- Woolfolk, R. L. (2018). Educational psychology: Active learning edition (14th ed.). Pearson.

- Yamashita, K., & Ando, J. (2019). Superstition and work motivation: A field study in Japan. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 49(1), 28-36.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 723 words

3 pages / 1579 words

2 pages / 887 words

6 pages / 2692 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Stephen King

Stephen King is one of the most prolific and successful authors of our time, with over 350 million copies of his books sold worldwide. His writing has influenced countless other authors and has become a staple in the horror and [...]

The name Stephen King is one that needs no introduction, as he is one of the most successful and prolific authors of all time. Born in Maine in 1947, King has been writing professionally since the early 1970s and has published [...]

Stephen King is a prolific writer known for his contributions to the horror genre. One of his most popular short stories, "The Boogeyman," was first published in 1973. This chilling tale has captivated readers for decades and [...]

In Popsy, by Stephen King, irony is used to make a point about human nature. Though this story is unrealistic and somewhat far-fetched, details make it seem realistic until the very end. The story begins with the main [...]

Depicted in the acclaimed short story “The Black Cat” (1843) by master of macabre, Edgar Allan Poe and “The Cat From Hell” (1977) by contemporary horror brilliance, Stephen King is a composition of suspense strategies, which [...]

Stephen King wrote one of his most successful novels, Gerald’s Game in 1992. The novel, much like many of his others, quickly became a New York Times #1 Best Seller. The book has recently been adapted into a very popular Netflix [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Ten things I learned about writing from Stephen King

The novelist James Smythe, who has been analysing the work of Stephen King for the Guardian since 2012 , on the lessons he has drawn from the master of horror fiction

- Stephen King short fiction competition – send us your stories

Stephen King is an All-Time Great, arguably one of the most popular novelists the world has ever seen. And there’s a good chance that he’s inspired more people to start writing than any other living writer. So, as the Guardian and King’s UK publisher Hodder launch a short story competition – to be judged by the master himself – here are the ten most important lessons to learn from his work.

1. Write whatever the hell you like

King might be best known – or, rather, best regarded – as a writer of horror novels, but really, his back catalogue is crammed with every genre you can think of. There are thrillers (Misery, Gerald’s Game), literary novels (Bag Of Bones, Different Seasons), crime procedurals (Mr Mercedes), apocalypse narratives (The Stand), fantasy (Eyes Of The Dragon, The Dark Tower series) … He’s even written what I think of as being one of the greatest Young Adult novels of all time: The Long Walk. Perhaps the only genre or audience he hasn’t really touched so far is comedy, but most of his work features moments that show his deft touch with humour. It’s clear that King does what he wants, when he wants, and his constant readers – the term he calls his, well, constant readers – will follow him wherever he goes.

2. The scariest thing isn’t necessarily what’s underneath the bed

Horror is a curious thing. What scares one person won’t necessarily scare another. And while there might be moments in his horror novels that tread towards the more conventional ideas of what some find terrifying, for the most part, the truly scary aspects are those that deal with humanity itself. Ghosts drive people to madness, telekinetic girls destroy whole towns with their powers, clowns … well, clowns are just bloody terrifying full stop. But the true crux of King’s ability to scare is finding the thing that his readers are actually worried about, and bringing that to the fore. If you’re writing horror, don’t just think about what goes bump in the night; think about what that bump might drive people to do afterwards.

3. Don’t be scared of transparency

One of my favourite things about King’s short story collections are the little notes about each tale that he puts into the text. The history of them, the context for the idea, how the writing process actually worked. They’re not only invaluable material for aspiring writers – because exactly how many drafts does it take to reach a decent story? King knows! – but they’re also brilliant nuggets of insight into King himself. Some people might think that it’s better off knowing nothing about authors when they read their work, but for King, his heart is on his sleeve. In his latest collection, The Bazaar of Broken Dreams, King gets more in-depth than ever, talking about what inspired the stories in such an honest way that it couldn’t have come from another writer’s pen. Which brings us to …

4. Write what you know. Sort of. Sometimes

Write what you know is the most common writing tip you’ll find anywhere. It’s nonsense, really, because if we all did that we’d end up with terribly boring novels about writers staring out of windows waiting for inspiration to hit. (If you like those, incidentally, head straight for the literary fiction section of your nearest bookshop.) But King understands that experience is something which can be channelled into your work, and should be at every opportunity. Aspects of his life – addiction, teaching, his near-fatal car accident, rock and roll, ageing – have cropped up in his work over and over, in ways that aren’t always obvious, but often help to drive the story. That’s something every writer can use, because it’s through these truths that real emotions can be writ large on the page.

5. Aim big. Or small

King’s written some mammoth books, and they’re often about mammoth things. The Stand takes readers into an apocalypse, with every stage of it laid out on the page until the final fantastical showdown. It deals with a horror that hits a group of characters twice in their lives, showing us how years and years of experience can change people. And The Dark Tower is a seven (or eight, or more, if you count the short stories set in its world) part series that takes in so many different genres of writing it’s dizzying. When he needs to, King aims really big, and sometimes that’s what you have to do to tell a story. At the other end of the spectrum, some of King’s most enduring stories – Rita Hayworth & Shawshank Redemption, The Mist – have come from his shorter works. He traps small groups of characters in single locations and lets the story play out how it will. The length of the story you’re telling should dictate the size of the book. Doesn’t matter if it’s forty thousand words or two hundred, King doesn’t waste a word.

6. Write all the time. And write a lot

King’s published – wait for it – 55 novels, 11 collections of stories, 5 non-fiction works, 7 novellas and 9 assorted other pieces (including illustrated works and comic books). That’s over a period of 41 years. That’s an average of two books a year. Which is, I must admit, a pretty giddying amount. That’s years of reading (or rereading, if you’re as foolishly in awe of him as I am). But he’s barely stopped for breath. This year has seen three books published by him, which makes me feel a little ashamed. Still, at my current rate of writing, I might catch up with him sometime next century. And while not every book has found the same critical and commercial success, they’ve all got their fans.

7. Voice is just as important as content

King’s a writer who understands that a story needs to begin before it’s actually told. It begins in the voice of the novel: is it first person, or third? Is it past or present tense? Is it told through multiple narrators, or just the one? He’s a master at understanding exactly why each story is told the way it’s told. Sure, he might dress it up as something simple – the story finding the voice it needs, or vice versa – but through his books you can see that he’s tried pretty much everything, and can see why each voice worked with the story he was telling.

8. And Form is just as important as voice

King isn’t really thought of as an experimental novelist, which is grossly unfair. Some of King’s more daring novels have taken on really interesting forms. Be it The Green Mile’s fragmented, serialised narrative; or the dual publication of The Regulators and Desperation – novels which featured the same characters in very different situations, with unsettling parallels between the stories that unfolded for them; or even Carrie’s mixed-media narrative, with sections of the story told as interview or newspaper extract. All of these novels have played with the way they’re presented on the page to find the perfect medium for telling those stories. Really, the lesson here from King is to not be afraid to play.

9. You don’t have to be yourself

Some of King’s greatest works in the early years of his career weren’t published by King himself. They were in the name of Richard Bachman, his slightly grislier pseudonym. The Long Walk, Thinner, The Running Man – these are books that dealt with a nastier side of things than King did in his properly attributed work. Because, maybe it’s good to have a voice that allows us to let the real darkness out, with no judgments. (And then maybe, as King eventually did in The Dark Half, it’s good to kill that voice on the page … )

10. Read On Writing. Now

This is the most important tip in the list. In 2000, King published On Writing, a book that sits in the halfway space between autobiography and writing manual. It’s full of details about his process, about how he wrote his books, channelled his demons and overcame his challenges. It’s one of the few books about writing that are actually worth their salt, mainly because it understands that it’s about a personal experience, and readers might find that useful. There’s no universal truths when it comes to writing. One person’s process would be a nightmare for somebody else. Some people spend years labouring on nearly perfect first drafts; some people get a first draft written in six weeks, and then spend the next year destroying it and rebuilding it. On Writing tells you how King does it, to help you to find your own. Even if you’re not a fan of his books, it’s invaluable to the in-development writer. Heck, it’s invaluable to all writers.

- Stephen King

- Horror books

- Creative writing

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Why We Crave Horror Movies

27 pages • 54 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Good Versus Bad Emotions and Their Expression

Emotions serve as an overarching theme in the essay, particularly the more specific emotion of fear. King addresses the difference between “good” and “bad” emotions and how horror movies allow people to experience negative emotions in an imaginary world instead of letting them run rampant in the real world, thus letting inherent “insanity” briefly run free in a controlled setting .

He describes the emotions that polite society allows, such as love and kindness, and how these good emotions are what society and people are supposed to strive for: “When we exhibit these emotions, society showers us with positive reinforcement” (Paragraph 10). On the other hand, “anticivilization,” or “bad,” emotions will always exist and, King posits, require frequent exercise to keep the “dark side” of humanity sated. Otherwise, the danger is that these dark emotions might escape into the real world. He doesn’t name these anticivilization emotions but instead uses a vignette to illustrate them:

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,350+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,950+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Stephen King

Stephen King

Bag of Bones

Billy Summers

Children of the Corn

Different Seasons

Doctor Sleep

Dolores Claiborne

Elevation: A Novel

End of Watch

Firestarter

From a Buick 8

Full Dark, No Stars

Gerald's Game

Gwendy's Button Box

Stephen King, Richard Chizmar

Featured Collections

Books about art.

View Collection

Good & Evil

Read Stephen King’s 2010 Essay on ‘The Blair Witch Project’

The King sure does know his horror.

Released in 1999, Eduardo Sanchez and Daniel Myrick’s The Blair Witch Project completely changed the game, not just making a massive profit on an incredibly low budget and not just kick-starting the found footage movement that’s still going strong today, but also revolutionizing movie marketing and, well, just plain terrifying the entire world. The film is nothing short of one of the most influential horror movies ever made, and though these things are of course totally subjective, it simply has to be considered one of the scariest movies of all time.

How scary? It scared the daylights out of Stephen freakin’ King.

Originally published in 1981, King’s nonfiction book Danse Macabre is, as described on the front cover, an essential overview of the horror genre, and the 2010 reissue of the book included a brand new forenote wherein King shared some opinions on the then-current state of horror cinema. Within that introduction was a short essay on The Blair Witch Project , and with Adam Wingard’s sequel Blair Witch now out there in the world, we wanted to share that with you.

Here’s Stephen King on The Blair Witch Project !

One thing about Blair Witch: the damn thing looks real. Another thing about Blair Witch: the damn thing feels real. And because it does, it’s like the worst nightmare you ever had, the one you woke from gasping and crying with relief because you thought you were buried alive and it turned out the cat jumped up on your bed and went to sleep on your chest. The first time I saw Blair Witch was in a hospital room about twelve days after a careless driver in a minivan smashed the shit out of me on a country road. I was, in a manner of speaking, the perfect viewer: roaring with pain from top to bottom, high on painkillers, and looking at a poorly copied bootleg videotape on a portable TV. (How did I get the bootleg? Never mind how I got it.) Around the time the three would-be filmmakers (Heather Donahue, Joshua Leonard, and Michael Williams, who, coincidentally, happen to be played by Heather Donahue, Joshua Leonard, and Michael Williams) start discovering strange Lovecraftian symbols hanging from the trees, I asked my son, who was watching with me, to turn the damn thing off. It may be the only time in my life when I quit a horror movie in the middle because I was too scared to go on. Some of it was the jerky quality of the footage (shot with a Hi-8 hand-held and 16-millimeter shoulder-mounted camcorders), some of it was the dope, but basically I was just freaked out of my mind. Those didn’t look like Hollywood-location woods; they looked like an actual forest in which actual people could actually get lost. I thought then that Blair Witch was a work of troubling, accidental horror, and subsequent viewings (where I actually finished the film) haven’t changed my mind. The situation is simplicity itself: The three kids, who start out making a documentary about a clearly bogus witch legend, get lost while making their movie. We know they are never going to get out; we’re told on the title card that opens the movie that, to date, they have never been found. Only the jumpy, disconnected, haunting footage they shot remains. The idea is complete genius, and a big budget would have wrecked it. Shot on a shoestring (a ragged one), this docu-horror movie gained its punch not in spite of the fact that the “actors” hardly act at all, but because of it. We become increasingly terrified for these people – even the annoying, overcontrolling Heather, who never shuts up and continues to insist everything is totally OK long after her two male companions (and everybody in the audience) knows it’s not. Her final scene – an excruciating close-up where she takes responsibility as one tear lingers on the lashes of her right eye – packs a punch that few Hollywood films, even those made by great directors, can match. The Fearless Girl Director who confidently proclaimed “I know exactly where we’re going” has been replaced by a terrified woman on the brink of madness. And, sitting in a darkened tent after six nights in the woods, with the Hi-8 camcorder held up to her own face, we understand that she knows it. Blair Witch, it seems to me, is about madness – because what is that, really, except getting lost in the woods that exist even inside the sanest heads? The footage becomes increasingly jerky, the cuts weirder, the conversations increasingly disconnected from reality. As the movie nears the end of its short course (at just eighty minutes and change, it’s like a jury-rigged surface-to-surface missile loaded with dynamite), the video actually disappears for long stretches, just as rationality disappears from the mind of a man or a woman losing his/her grip on the real world. We are left with a mostly dark screen, panting, elliptical lines of dialogue (some we can understand, some we can only guess at), noises from the woods that might or might not be made by human beings, and occasional blurry flashes of image: a tree trunk, a jutting branch, the side of a tent in a close-up so intense that the cloth looks like green skin. “Hungry, cold, and hunted,” Heather whispers. “I’m scared to close my eyes, and I’m scared to open them.” Watching her descent into irrationality, I felt the same way. The movie climaxes when Heather and Michael find a decaying house deep in the woods. Shot almost completely in 16mm black-and-white at this point, the movie confronts us with a series of images that are simultaneously prosaic and almost too awful to bear – the wreckage inside seems to glare. Still carrying the camera, Heather bolts up the stairs. At this point, her two friends seem to be calling from everywhere, and the camera’s randomly shifting eye flows past the handprints of the children who have almost certainly been murdered in this house. There’s no dramatic music here or anywhere else; Blair Witch needs no such cinematic steroids. The only sounds are shuffling footsteps, yelling voices (from everywhere!) and Heather’s escalating moans of terror. Finally, she plunges down to the basement, where one of the hokey stories they were told before their rash entry into the woods turns out to not be bullshit after all. Michael (or is it Josh?) stands in the corner, dumbly waiting for the thing from the woods to do what it will. There is a thud as that unseen thing falls on Heather from behind. The camera drops, showing a blurred nothing. The film ends. And if you’re like me, you watch the credits and try to escape the terrified ten-year-old into whom you have been regresse d.

Writer in the horror community since 2008. Editor in Chief of Bloody Disgusting. Owns Eli Roth's prop corpse from Piranha 3D. Has four awesome cats. Still plays with toys.

You may like

Stay Home, Watch Horror: Five Horror Movie Prequels to Stream This Week

5 New Horror Movies Released This Week Including ‘Easter Bloody Easter’

Stephen King’s ‘Joyland’ Is an Emotional Rollercoaster That “Shines” [The Losers’ Club Podcast]

‘April Fool’s Day’ – The Lost Ending Survives in the ’80s Slasher Movie’s Novelization

By now, the outcome of 1986’s April Fool’s Day is well known: an heiress’ guests are misled to believe their party is being picked off by a killer among them. However, had the producers not requested a last-minute change, the film would have turned the tables on the elaborate prank’s orchestrator; she would have died for real. Fans had hoped to see footage from this shot-but-unused ending on Shout! Factory’s Blu-ray . No such luck, unfortunately. And it was likely not for a lack of trying on the distributor’s part, either. Although the final cut of Fred Walton ’s film features no actual deaths, Jeff Rovin ’s novelization was based on an earlier draft of Danilo Bach ’s script. Which means this now out-of-print adaptation used that sought-after “lost” ending.

Before taking a deadly turn, the novelization is not all that different from its cinematic counterpart: Muffy St. John (played by Deborah Foreman on screen) invites family, friends and classmates to her isolated house off the Maine coast. Their weekend getaway falls on April Fool’s, so there are plenty of pranks to witness. These jokes gradually go from harmless to dangerous. Of course, the most considerable and convoluted of these tricks is unbeknownst to everyone, apart from the mastermind and her silent accomplices.

A tremendous key to April Fool’s Day ’s success is its cast. Fresh-faced, well defined and oddly charming, Muffy and her young peers are certainly not the deepest lot in horror history, but what they lack in development they make up for in personality and presence. It could be said, keeping that alternate ending intact runs the risk of removing viewers’ bonding time with the cast; watching them interact during the less life-threatening moments is both amusing and crucial to their likability. Like other novelization authors who explore and flesh out their characters, especially ones who have been streamlined for commercial filmmaking, Rovin exerted himself when translating April Fool’s Day to text. He enhanced the core aspects of their personalities, embellished their way of talking, and expanded on their varied backgrounds.

Pictured: The cast stares in disbelief after Buck is injured in April Fool’s Day .

The element of sex is played up far more in the novelization. In the film, everyone sticks to their designated S.O.; aspiring filmmaker/pornologist Chaz Vyshinski ( Clayton Rohner ) and horny elitist Nikki Brashares ( Deborah Goodrich ) need not look elsewhere for their carnal cravings, and Rob Ferris ( Ken Olandt ) and girlfriend Kit Graham ( Amy Steel ) cling to one another as terror starts to emerge. Rovin does take an opportunity to investigate throwaway details, such as Rob’s open fly. Or in this case, read into them. Rather than allowing the zipper joke to be just that, or maybe even a physical manifestation of Rob’s incompetence, the novelization drums up a backstory about Rob’s fear of commitment. There, his zipper was down because he had recently slept with another woman before reaching the ferry. Meanwhile, the social incest is italicized as Muffy and Nikki trade sexual war stories about their mutual friend-with-benefits and all-around “lousy lay” Arch Cummings ( Thomas F. Wilson ), and Nikki eventually trades Chaz for the film’s clever parody of young Reaganites, Harvey “Hal” Edison, Jr. ( Jay Baker ). The Bruce Springsteen fan is as interested in landing a job as he is a bed partner in the book.

Arguably worse than fooling everyone into thinking there was a killer on the prowl was Muffy planting those highly personalized “fake clues” in her guests’ rooms. The film has Muffy owning up to her lapse in judgment, especially regarding Nan Youngblood ( Leah Pinsent ). With the second twist-ending included in the novelization, though, the origins of those various items were not only more detailed — Nikki’s BDSM gear were like the ones her parents used, and Hal’s newspaper clippings pertain to a fatal car accident he covered up — their existence was owed elsewhere. As Nan confronts Muffy in the book, the host explains she left objects reminding everyone of back home. Copies of The Tennessee Gazette for Hal, steroids for Arch, a vibrator for Nikki, and a party tape for Nan were all replaced. Arch instead received “a stack of syringes and needles, a tightly coiled length of rubber tubing, razor blades” (plus a crack spoon in the film), and Nan was haunted by pre-recorded baby cries in reference to her secret abortion. Muffy pleaded her case, but the damage was done.

Pictured: An excerpt from a revised version of the April Fool’s Day script.

So, who switched all the items? Someone wanting the other characters to have motivation for committing a real murder, that’s who. After Muffy’s self-unmasking in the novelization, her guests all return to the mainland. En route, Skip, who was revealed to be Muffy’s brother rather than her cousin, not so subtly inspires everyone to go back and give his sister a taste of her own medicine. The participants (Kit, Nikki, Chaz and Rob) go forward with their slapdash tit-for-tat without realizing they are actually walking straight into Skip’s trap. Muffy’s brother wanted to be his father’s sole heir, and killing his sister would have ensured that. Then he could frame one of her friends who, some more than others, had incentive to kill Muffy. The scheme did not go as planned, though, and Skip died instead. In the depressing, Prom Night -esque conclusion, the shocked sister cradles her dead brother’s body, unable to process what just happened.

There was another proposed ending that mixed the above version with the one ultimately used in the film: Muffy believes Skip sliced her throat, only to then realize this was part of his and the others’ retributive prank. Later, Skip is shown helping his sister open her murder-mystery inn. Going with Skip as the killer would have given his actor, Griffin O’Neal , more screentime. Especially after Walton vouched for his casting. The as-is cut incidentally underutilized O’Neal, who dipped out of the story once Skip became the first victim of “Buffy St. John.”

Anyone who disliked the film’s rug-pull might prefer the novelization. Removing that original final act from the film, however, was for the best. Producer Frank Mancuso, Jr. wanted to get away from making another straightforward slasher, and Fred Walton , who did not consider himself a fan of horror, wanted to avoid doing the same-old . And by going against the grain, April Fool’s Day wound up being more memorable than many of its contemporaries. The film is an ingenious stab at satirical horror, made well before self-awareness was so widespread in the genre.

Pictured: The purple edition of Jeff Rovin’s April Fool’s Day novelization.

‘Late Night with the Devil’ – When Is the New Horror Movie Streaming at Home?

‘Monster Mash’ Trailer – Michael Madsen Assembles His Own Monster Squad in New Indie Horror Movie

Godzilla: Ranking All 35 Live Action Movies – Including ‘Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire’

“Them: The Scare” Poster Will Haunt Your Nightmares Until Tomorrow’s Trailer Release

‘Fear Street: Prom Queen’ – Meet the Ensemble Cast of Netflix’s Next R.L. Stine Horror Movie [Exclusive]

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- General Hospital

- The Bold and the Beautiful

- Celebrities

- Movie Lists

- Whatever Happened To

- Days of Our Lives

- Young and The Restless

- The Walking Dead

- American Horror Story

A Summary of Stephen King’s Essay “Why We Crave Horror Movies”

A while back, renowned author Stephen King wrote an essay that appeared in a leading magazine entitled “Why We Crave Horror Movies.” In that essay, he tried to explain why people enjoy watching scary movies so much more than virtually any other type of movie out there. The idea he came up with was one that actually surprised a lot of people, and it certainly made them stop and think about how they interact with their own little corner of the world for a minute.