‘The Word Is Camp’: What to Know About the Inspiration for This Year’s Met Gala, as Explained in 1964

T he annual benefit for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute is as high-fashion as fashion gets — but this year’s Met Gala, on Monday night, will bring a heavy dose of low culture to the red carpet. After all, the gala’s theme celebrates the opening of its exhibition Camp: Notes on Fashion , and that interaction of high and low is key to camp’s spirit.

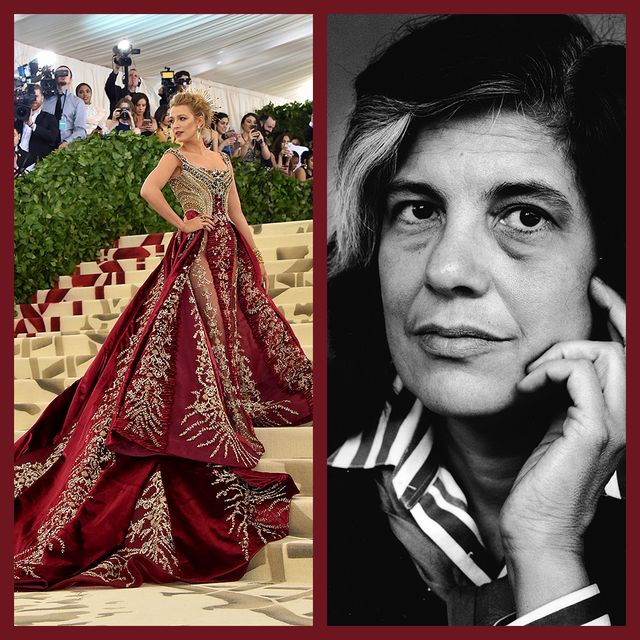

While the origins of camp can be traced back to the reign of the French King Louis XIV, the inspiration for this show is much more recent. The modern camp aesthetic was solidified in the 1964 Partisan Review essay “Notes on ‘Camp'” by the American critic Susan Sontag .

The essay first appeared that fall, and didn’t take long to grab mainstream attention. Case in point: That December, TIME’s “Modern Living” section explained to readers why everyone was suddenly talking about camp:

Where are the dandies these days? Not the mere fops and mannered exhibitionists, but the lovers and arbiters of style for style’s sake, the cherishers and curators of what’s amusing (as opposed to what’s serious) — a predilection that is one of the luxuries of affluent societies. They thrived in Socrates’ Athens and at the Roman courts of emperors and Popes. The 18th century shone with them, and the 19th century produced the dandy of all time, Oscar Wilde. Wilde rebutted the industrial revolution with flowing locks and velvet suits; he warded off its fumes with a long-stemmed flower. The modern dandy, on the other hand, revels detachedly and deliciously in the vulgarity of mass culture. And the word is not dandyism any more. According to one of Manhattan’s brightest young intellectuals, Novelist Susan Sontag, the word is “Camp.” The essence of Camp, writes Miss Sontag in the Partisan Review , is “its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.” Tiffany lamps are Camp, she says by way of illustration, and so is a fondness for Scopitone films and the lurid pseudo journalism of the weekly New York National Enquirer. Turn-of-the-century postcards are Camp; so is enthusiasm for the ballet Swan Lake and the 1933 movie King Kong . Dirty movies are Camp — provided one gets no sexual kick out of them — and so are the ideas of the French playwright Jean Genet, an ex-thief and pederast who boasts about it. “Genet’s statement that ‘the only criterion of an act is its elegance’ is virtually interchangeable, as a statement, with Wilde’s ‘In matters of great importance, the vital element is not sincerity, but style.'” In matters sexual, according to Miss Sontag, Camp goes against the grain, cherishing either the androgynous, swoony girl-boys and boy-girls of pre-Raphaelite painting or the plangent supersexiness of Jayne Mansfield or Victor Mature. In art, Camp’s exaggeration must proceed from passion and naiveté. “When something is just bad (rather than Camp),” she writes “it’s often because the artist hasn’t attempted to do anything really outlandish. ‘It’s too much,’ ‘It’s fantastic,’ ‘It’s not to be believed,’ are standard phrases of Camp enthusiasm.” Click here to read the full story from 1964 in the TIME Vault

The essay launched Sontag’s career as a literary critic, in which “she argued for a more sensuous, less intellectual approach to art,” TIME noted in her obituary , when she died in 2004 at the age of 71. “It was an irony lost on no one, except perhaps her, that she made those arguments in paragraphs that were marvels of strenuous intellection.”

“Notes on ‘Camp'” not only launched her career, but also it launched a new way of thinking. It fit right in with the spirit of the ’60s, an era known for new ideas and the breaking down of taboos. As TIME noted in 1964, when it came to camp, this phenomenon was particularly true in terms of sexuality. Camp was not gender or sexuality specific, Sontag argued, but the aesthetic had been embraced by the LGBTQ community as a way to “neutralize moral indignation” by promoting a playful approach to that which others took seriously.

Which was not to say Sontag didn’t take camp seriously.

“Seriousness was one of Sontag’s lifelong watchwords, but what she sometimes dared to take seriously were matters that educated opinion, as it emerged from the cramped quarters of the 1950s, dismissed as trivia,” TIME wrote in her obituary. “At a time when the barriers between high-and lowbrow were absolute, she argued for a genuine openness to the pleasures of pop culture.”

At the time, however, some were worried that coverage in a mainstream publication like TIME would spell the closing of camp’s fun. “By publishing your recent analysis of ‘Camp,’ you have ensured that Camp will no longer be Camp, if you see what I mean,” one reader argued in a letter to the editor, while another argued that “‘Camp’ is here to stay.” Fifty-five years later, on camp’s big night, it’s clear that the latter was right.

For more current examples of “camp,” see TIME’s illustrated guide .

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Passengers Are Flying up to 30 Hours to See Four Minutes of the Eclipse

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Essay: The Complicated Dread of Early Spring

- Why Walking Isn’t Enough When It Comes to Exercise

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at [email protected]

You May Also Like

Why Susan Sontag Would Have Hated a Camp-Themed Met Gala

Sontag's 1964 essay "Notes on Camp" is the theme of this year's Costume Institute fundraiser. Here, her biographer weighs in.

Every item on this page was chosen by a Town & Country editor. We may earn commission on some of the items you choose to buy.

Susan Sontag would have loved the Met Gala. (I'll get to the hate in a moment.)

This year it's inspired (at least in part) by her. Since its beginnings as a fundraiser for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, the gala has become perhaps the most paparazzied evening in the fashion calendar, with each year’s celebration putting the spotlight on a different theme. This year, it pays homage to Sontag’s essay “Notes on ‘Camp.’”

.css-4rnr1w:before{margin:0 auto 1.875rem;width:60%;height:0.125rem;content:'';display:block;background-color:#9a0500;color:#fff;} .css-gcw71x{color:#030929;font-family:NewParis,NewParis-fallback,NewParis-roboto,NewParis-local,Georgia,Times,serif;font-size:1.625rem;line-height:1.2;margin:0rem;}@media(max-width: 64rem){.css-gcw71x{font-size:2.25rem;line-height:1.1;}}@media(min-width: 48rem){.css-gcw71x{font-size:2.625rem;line-height:1.1;}}@media(min-width: 64rem){.css-gcw71x{font-size:2.8125rem;line-height:1.1;}}.css-gcw71x b,.css-gcw71x strong{font-family:inherit;font-weight:bold;}.css-gcw71x em,.css-gcw71x i{font-style:italic;font-family:inherit;} Sontag would have been thrilled by any partygoers who stayed true to the fighting, mocking, winking, outsiders’ spirit of camp.

Published in 1964 in the Partisan Review , a legendary literary and political quarterly, the essay made Sontag famous. It was daring, naughty. “Many things in the world have not been named,” she wrote, “and many things, even if they have been named, have never been described.”

She, and then her legions of imitators, were determined to name these unnamed things and filled libraries with writing on subjects that serious people hadn’t written about—or hadn’t written about seriously, before.

One such subject was a particular flavor of homosexual taste called camp. An early draft of Sontag's essay was called “Notes on Homosexuality,” and the piece, later published as part of her collection Against Interpretation , can be read as a codification of gay taste. "The essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration," wrote Sontag. "And Camp is esoteric—something of a private code, a badge of identity even, among small urban cliques."

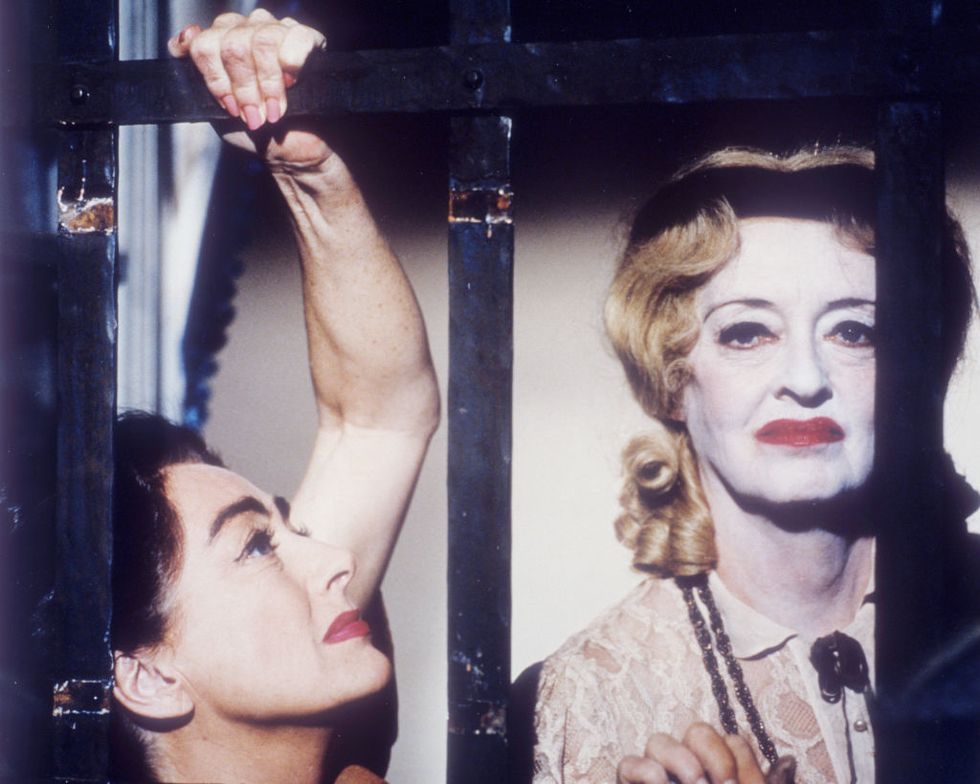

Sontag patiently explains why Cocteau is camp but not Gide; Strauss but not Wagner. Caravaggio and “much of Mozart” are grouped, in her ranking, with Jayne Mansfield and Bette Davis; John Ruskin effortlessly sidles up alongside Mae West. The true “aristocrats of taste,” she wrote, were homosexuals, whose “aestheticism and irony,” alongside “Jewish moral seriousness,” made up the modern sensibility.

Thanks to Sontag, camp came to symbolize the new, liberal attitude toward sexuality, politics, and society that we associate with the 1960s. Today, when we read “Notes on ‘Camp,’” it seems fun, funny—and not a little dated. But when it was published, many people responded with outrage. As the birth-control pill threatened male supremacy and the black civil rights movement threatened white supremacy, “Notes on ‘Camp’” was a threat to heterosexual supremacy. “Notes on ‘Camp’” was part of a broader movement to overthrow established hierarchies.

Camp was resistance.

Homosexual taste had always been an undercurrent in art, but it had rarely been named as such: to do so would have been to shove it into a ghetto, whose denizens were widely assumed, at the time, to be sick, deranged, and perverted. Sontag would have loved seeing this outsider’s sensibility embraced in a temple of the establishment like the Metropolitan Museum.

Susan Sontag would also have hated the Met Gala.

“I am strongly drawn to Camp,” she wrote in her essay, “and almost as strongly offended by it.” She was well aware that one risk of opening up critical hierarchies too much was that they would be replaced by an even more powerful hierarchy: the one whose measure is dollars and cents.

Sontag was a lifelong champion of difficult art, the kind of art that rewarded years of patient study, the kind of art that was constantly threatened by a society that prized glitz and gloss. She was deeply uncomfortable with the idea of celebrity—the reduction of a person to the image of a person—and would have been nervous about an event that celebrates tabloid fame so unironically.

In a world where gay people are murdered every day, she would have been alarmed to see a profound critique of mainstream society appropriated for an event that symbolizes the insider realm from which gay people have been excluded. And in a country where people beg for insulin on Craigslist, she, a lifelong activist for social justice, would have been disgusted an event with a $30,000 per person ticket, and by the obscene sums attendees spend on clothes and jewelry.

In gay aesthetics, she saw “a criticism of society,” a “protest against bourgeois expectations.” And so Sontag would have been thrilled by any partygoers who—at this most bourgeois event, in this most establishment of venues—stayed true to the fighting, mocking, winking, outsiders’ spirit of camp.

@media(min-width: 40.625rem){.css-1jdielu:before{margin:0.625rem 0.625rem 0;width:3.5rem;-webkit-filter:invert(17%) sepia(72%) saturate(710%) hue-rotate(181deg) brightness(97%) contrast(97%);filter:invert(17%) sepia(72%) saturate(710%) hue-rotate(181deg) brightness(97%) contrast(97%);height:1.5rem;content:'';display:inline-block;-webkit-transform:scale(-1, 1);-moz-transform:scale(-1, 1);-ms-transform:scale(-1, 1);transform:scale(-1, 1);background-repeat:no-repeat;}.loaded .css-1jdielu:before{background-image:url(/_assets/design-tokens/townandcountrymag/static/images/diamond-header-design-element.80fb60e.svg);}}@media(min-width: 64rem){.css-1jdielu:before{margin:0 0.625rem 0.25rem;}} Fashion @media(min-width: 40.625rem){.css-128xfoy:before{margin:0.625rem 0.625rem 0;width:3.5rem;-webkit-filter:invert(17%) sepia(72%) saturate(710%) hue-rotate(181deg) brightness(97%) contrast(97%);filter:invert(17%) sepia(72%) saturate(710%) hue-rotate(181deg) brightness(97%) contrast(97%);height:1.5rem;content:'';display:inline-block;background-repeat:no-repeat;}.loaded .css-128xfoy:before{background-image:url(/_assets/design-tokens/townandcountrymag/static/images/diamond-header-design-element.80fb60e.svg);}}@media(min-width: 64rem){.css-128xfoy:before{margin:0 0.625rem 0.25rem;}}

Queen Letizia Wears the Perfect Red Leather Pants

The Weekly Covet : Spring Shoes

The Knit Polo That Is an Off-Duty Essential

The Best Women's Sneakers to Wear to Work

The Best Pink Dresses to Wear to the Kentucky Oaks

The Best Kentucky Derby Hats

Kentucky Derby Outfit Inspiration

The Best White Wide Leg Jeans of the Season

Meghan Markle's Style Evolution

Alejandra Alonso Rojas Launches a New Bridal Line

'90s-Era Thong Sandals Are Back & Chicer Than Ever

- The Inventory

Support Quartz

Fund next-gen business journalism with $10 a month

Free Newsletters

Susan Sontag’s 54-year-old essay on “camp” is essential reading

What do Swan Lake , Tiffany lamps, and “ Broccoli ” feauring Lil Yachty all have in common? Ostensibly, nothing. But a thread runs through them all: the cultural trope known as “camp.”

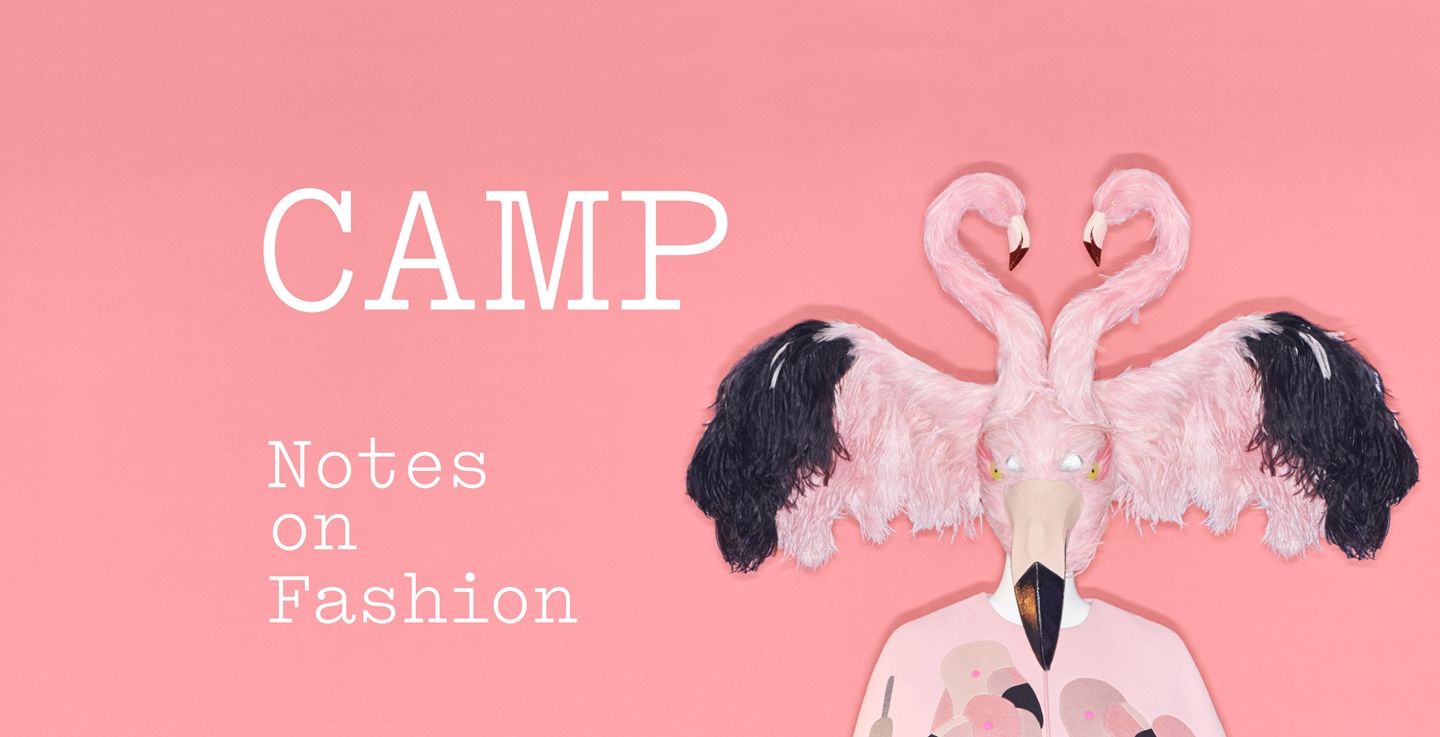

Camp also happens to be the theme of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s much-anticipated costume exhibition, the New York City museum announced this week. “ Camp: Notes on Fashion ” will be unveiled on May 6 at the annual Met Gala, an event underwritten by Gucci and led by Vogue editor-in-chief and Condé Nast artistic director Anna Wintour. The gala will be co-chaired this year by the singer and actress Lady Gaga, the tennis star Serena Williams, Gucci creative director Alessandro Michele, and singer Harry Styles (who recently posed in a very camp livestock-filled Gucci campaign ).

Andrew Bolton, head curator of the Met’s Costume Institute, will explore how the “camp sensibility” can be traced back to the French court under Louis XIV, who gathered the decorated Parisian nobility at Versailles. In that palace of high camp, “everything was pose and performance,” as Hamish Bowles puts it in Vogue . And Bolton told the New York Times that we live now in the midst of another camp explosion: “Whether it’s pop camp, queer camp, high camp or political camp—Trump is a very camp figure—I think it’s very timely.”

The exhibition is inspired and informed largely by Susan Sontag’s brilliant 1964 essay, “Notes on ‘Camp,'” a treatise written over 50 years ago that managed to predict the bizarre features of today’s cultural scene to an uncanny degree.

What is “camp,” anyhow? Let Susan Sontag explain

The essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.

This is probably most-cited definition of Camp in Sontag’s essay, and it is how she introduces her readers to the elusive “Camp sensibility.”

Though in modern usage “camp” is often used as synonymous to “kitschy” or “flamboyant.” Sontag’s definition is far more nuanced. ”Camp is esoteric,” she explains, “something of a private code, a badge of identity even, among small urban cliques… I am strongly drawn to Camp, and almost as strongly offended by it.”

Sontag’s “random examples of items which are part of the canon of Camp” are illustrative of the aesthetic, and worth reading in full, but they include Tiffany lamps, “the old Flash Gordon comics,” Swan Lake , and “stag movies seen without lust.”

Of Sontag’s 58 “jottings” on the topic, here are a few that feel especially useful today:

25. The hallmark of Camp is the spirit of extravagance. Camp is a woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers.

24. When something is just bad (rather than Camp), it’s often because it is too mediocre in its ambition. The artist hasn’t attempted to do anything really outlandish. (“It’s too much,” “It’s too fantastic,” “It’s not to be believed,” are standard phrases of Camp enthusiasm.)

55. Camp taste is, above all, a mode of enjoyment, of appreciation—not judgment. Camp is generous. It wants to enjoy.

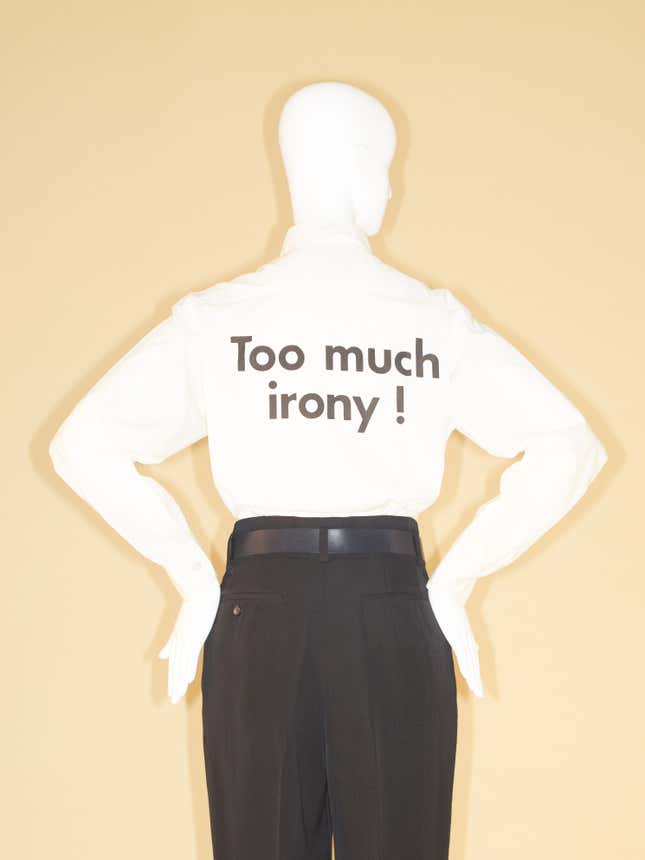

38. Camp is the consistently aesthetic experience of the world. It incarnates a victory of “style” over “content,” “aesthetics” over “morality,” of irony over tragedy.

41. The whole point of Camp is to dethrone the serious. Camp is playful, anti-serious. More precisely, Camp involves a new, more complex relation to “the serious.” One can be serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious.

27. What is extravagant in an inconsistent or an unpassionate way is not Camp. Neither can anything be Camp that does not seem to spring from an irrepressible, a virtually uncontrolled sensibility. Without passion, one gets pseudo-Camp–what is merely decorative, safe, in a word, chic.

58. The ultimate Camp statement: it’s good because it’s awful… Of course, one can’t always say that. Only under certain conditions.

While Sontag is the main inspiration for the exhibit, the Met will not restrict itself entirely to her definitions. Failed seriousness is a major theme, but it’s important to note that not all examples of camp are supposed to be serious; indeed, as Bolton told the Times, “when [something] is ‘campy,’ it is more self-conscious, but we are going to look at both.”

Is camp another way of saying “gay”?

“[T]he history of Camp taste is part of the history of snob taste,” Sontag writes. “But since no authentic aristocrats in the old sense exist today to sponsor special tastes, who is the bearer of this taste?”

What arose in the absence of true aristocrats, Sontag wrote in 1964, was “an improvised self-elected class, mainly homosexuals, who constitute themselves as aristocrats of taste.”

Indeed, considering the level of vitriol around homosexuality in the 1960s, it’s easy to imagine the appeal of camp, which embraces a kind of performance of identity. But the association of camp with gay culture led to the over-simplification of the term, which eventually fell out of favor after it began to mean “flamboyant” or even was used to mean “gay-seeming” in a derogatory way.

While the Met exhibit is presenting the more nuanced definition of camp that Sontag outlines, the term still has a demeaning connotation to some, even among the connoisseurs and creators of camp. Just last year, writer Amelia Abraham described an interview she did with the unquestionably camp filmmaker John Waters in Vice: “I mentioned the word ‘camp’ offhand and he sounded shocked. ‘Camp!’ he exclaimed—’I don’t know anyone that would ever say the word camp out loud, it’s like an 80-year-old gay man in a 1950s antique shop under a Tiffany lampshade.'”

Fashion is camp

Today’s most prevalent trends—from the rise of ugly footwear to the downright freaky ensembles that designers have sent down the catwalk over the past several years—reek of camp. “Camp is art that proposes itself seriously, but cannot be taken altogether seriously because it is ‘too much,'” Sontag writes.

Some of the most consistent over-the-top fashion is coming from Balenciaga under Demna Gvasalia and Gucci under Michele, and both will be represented in the Met exhibit. Balenciaga—with its platform crocs, fanny packs, and Comic Sans-printed dresses —is openly subversive, so much so it has been accused of “trolling” consumers.

Likewise, in an ode to the absurd, Gucci sent models down the runway holding their own severed heads in 2017:

Alessandro Michele also presented an aesthetically campy collection this year:

Camp’s irony tenant is also exemplified by Virgil Abloh for Off-White, with his use of quotation marks, which allow him “ to operate in a mode of ironic detachment , ” the designer explained in a 2017 interview in 032 magazine:

John Galliano, the iconic camp-maker now at Margiela, was busy doing camp at Dior 15 years ago:

As Riccardo Slavik wrote for Collectible Dry in 2017, Galliano’s spring 2004 collection was “a perfect example of Fashion Camp, a show that fused Ancient Egypt, extreme volumes, Cleopatra-in-space drag queen makeup and total impracticality in an iconic way, totally disregarding any thought of sales or wearability… it is camp because it both succeeds and fails so spectacularly .”

Other designers in the exhibit include Charles Frederick Worth and Miuccia Prada, as well as Rei Kawakubo for Comme des Garçons (who was herself the subject of the Costume Institute’s exhibit and gala two years ago).

Donald Trump is camp

With his lurid golden bathrooms, bombastic reality TV persona, gaudy properties, and affinity for trashy celebrity, Donald Trump was a caricature long before he became US president. As Bolton suggests in calling Trump a “very camp figure,” his mannerisms, vulgarity, and personal style have infused our times.

Indeed, Sontag could have had the current US president in mind when she wrote these lines in 1964: “The new-style dandy, the lover of Camp, appreciates vulgarity. Where the dandy would be continually offended or bored, the connoisseur of Camp is continually amused, delighted. The dandy held a perfumed handkerchief to his nostrils and was liable to swoon; the connoisseur of Camp sniffs the stink and prides himself on his strong nerves.”

Music is camp

The picture of Lady Gaga in her infamous “meat dress” is a study in camp, and just as high camp was the pop star’s recent water-taxi arrival at the Venice Film Festival to promote A Star is Born— as a “platinum Aphrodite borne on the waves, black stilettos skimming the sea foam,” according to the New York Times . The pop star and actress carries off these performances with a devastatingly deadpan delivery, recalling again Sontag’s words: “In naïve, or pure, Camp, the essential element is seriousness, a seriousness that fails.”

Both autotune and mumble-rap have been raked over the coals by serious vocalists and lyricists. But excessive autotune (like that of the rapper T-Pain) is perfectly camp: grave in its attempt but intentionally absurd in its execution.

Similarly camp is the anthem “Believe” by Cher, who arguably pioneered the use of autotune:

Meanwhile mumble-rap, a style of rap marked by its incomprehensible—literally “mumbled”—lyrics has been derided for its lack of serious content. But arguably, by prioritizing style over content, mumble-rap becomes “so-bad-it’s-good” camp.

The singer and entrepreneur Rihanna also deserves an honorable mention in the pantheon of camp musicians, particularly for her Met Gala looks of the past several years:

Sneakers are camp

Fashion’s recent embrace of gleefully, garishly ugly sneakers is a triumph of camp. The trend began around 2015 and took serious hold in early 2017, when Vetements released a hideous $650 version of Reebok’s Instapump Fury.

Today, most high-end designers have released their own takes on the absurd, chunky sneaker, from Louis Vuitton to Prada to Margiela.

But the undisputed king of the ugly sneakers is Balenciaga’s Triple S:

Sontag might as well have had a pair of these monstrosities laced to her feet when she wrote: “The discovery of the good taste of bad taste can be very liberating… Here Camp taste supervenes upon good taste as a daring and witty hedonism.”

📬 Sign up for the Daily Brief

Our free, fast, and fun briefing on the global economy, delivered every weekday morning.

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

A Very This-Season Guide to Susan Sontag’s Essay “Notes on Camp”

By Steff Yotka

This year’s Met Gala and corresponding Costume Institute exhibit, “Camp: Notes on Fashion,” are themed around the idea of camp as it’s defined in Susan Sontag’s 1964 essay “Notes on Camp.” Not familiar? Not to worry. Sontag’s easily Google-able essay is broken down into 58 bullet points that explain what she sees as the camp sensibility. First note: Camp is a sensibility, not an idea.

Some of the 58 points have gone more viral than others. It’s likely that in the lead-up to this year’s gala you’ve come across No. 38: “Camp is the consistently aesthetic experience of the world. It incarnates a victory of “style” over “content,” “aesthetics” over “morality,” of irony over tragedy. Or maybe you’ve gotten a whiff of No. 8, which declares camp to be “the love of the exaggerated, the ‘off,’ of things-being-what-they-are-not.”

But what about 27? “Without passion, one gets pseudo-Camp—what is merely decorative, safe, in a word, chic.” Or 56? “Camp is a tender feeling.” Or 9 and 14, which outline the canon of camp figures and fantasies over time?

With a month to go before the Met Gala, we’ve taken it upon ourselves here at Vogue Runway to celebrate some excerpts from Sontag’s “Notes on Camp” alongside looks from the Fall 2019 runways. Met Gala guests, take note.

25. “Camp is a woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers.”

Marc Jacobs Fall 2019

9. “The androgyne is certainly one of the great images of Camp sensibility.”

Thom Browne Fall 2019

31. “So many of the objects prized by Camp are old-fashioned, out-of-date, demodé . . . What was banal can, with the passage of time, become fantastic.”

Moschino Fall 2019

By Alexandra Macon

By Hannah Jackson

By Audrey Noble

10. “Camp sees everything in quotation marks.”

Off-White Fall 2019

13. “The relation of Camp taste to the past is extremely sentimental.”

Gucci Fall 2019

41. “The whole point of Camp is to dethrone the serious. Camp is playful, anti-serious.”

Christopher Kane Fall 2019

4. “Random examples of items which are part of the canon of Camp [include] … Swan Lake.”

Maison Margiela Fall 2019

Vogue Runway

By signing up you agree to our User Agreement (including the class action waiver and arbitration provisions ), our Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement and to receive marketing and account-related emails from Architectural Digest.. You can unsubscribe at any time. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

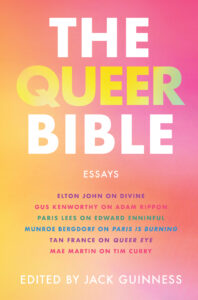

“Camp is a Sensibility.” On Susan Sontag, Extravagance, and Sexuality

Amelia abraham considers a queer icon.

I have a memory. I think I was about 13 years old—probably wearing dungarees, or at least, that’s how I like to imagine my proto-lesbian self. I was kneeling in my parents’ living room and slotting a VHS into the recorder. The film was called The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert , a nineties cult classic about two drag queens and a Transgender woman who go on a road trip across the Australian outback. It was the first time I had watched the film and I remember the opening scene distinctly: a drag queen in a big blonde wig pads onto the stage in a dingy club and starts doing a number, a lip sync to a dramatic seventies ballad. “What the hell is this?” I thought—I had never seen drag before, but I was instantly hooked. The film’s strapline, which was printed across the VHS box, seemed appropriate: “Drag is the drug,” it read.

Looking back now, there’s one moment that really stands out in my mind from Priscilla , and that’s when Guy Pearce’s character, Felicia, sits atop the giant silver stiletto that’s fixed to the roof of the tour bus the queens are traveling in, and performs a stellar lip sync to a song from the opera Madame Butterfly . First, we’re given a close-up of the beauty look—high, arched eyebrows painted rudely onto Pearce’s face—before the camera slowly pans outward to the reveal: the outfit, a glistening silver-sequined catsuit, then that ridiculous giant shoe, then the vast expanse of the Australian desert. The final touch, although I wouldn’t quite clock it until I rewatched the film years later, is the graffiti that was sprayed onto the side of the bus in a previous scene: “AIDS fuckers go home.” Horribly homophobic, yes, but Pearce’s performance steals the shot, as if to say: “Whatever insult you throw at me, I’ll always be fabulous.”

I didn’t know it yet, but watching this film was a pivotal moment in a long-standing love affair for me. A love affair with all things camp.

I’ve been consuming camp for as long as I can remember, before I learned that there was a word for it. Bands I loved, like the Spice Girls and Steps, were camp; so were the aunts in Sabrina the Teenage Witch , and my favorite childhood film, Hocus Pocus— mostly because it had Bette Midler in it, and anything Bette Midler does is camp. The first cassette single I bought was Cher’s Believe (guilty), which was iconically camp— whether or not it flew under my seven-year-old radar. I loved to watch the high-drama performances on the Eurovision Song Contest, too. And remember that Simpsons episode “Homer’s Phobia,” where the godfather of camp and trash, the filmmaker John Waters, plays Marge’s new gay best friend, the owner of a kitsch bric-a-brac store? Definitely my favorite Simpsons episode, and one of my earliest memories of camp.

A lot of us have camp tastes when we’re children—some of us grow out of them, others grow up to be homosexual. It turned out that I am in the latter group, which meant that, at 19, now more familiar with the word “camp” and newly familiar with my own queerness, I wanted to know more about it. I understood that “camp” was often used as a way to describe someone or something effeminate, usually gay men. It was also a term used to describe a lot of the kind of films, TV shows, and pop music I liked. But what made them camp exactly, I wasn’t sure. In all honesty, I was a little confused by the word. Was it a way of being? Or a way of seeing things? In fact, until I found the writer Susan Sontag’s famous 1964 essay, “Notes on ‘Camp,’ ” I don’t think I could have put it into words.

Sontag’s essay explains that camp is a sensibility, a “mode of aestheticism,” “a private code,” “a badge of identity, even.” The hallmark of camp, she says, is the spirit of extravagance. It can be broad (as disparate as Bette Midler and John Waters are, their camp qualities unite them), but certainly not everything can be camp; in fact, it’s really quite particular. “Indeed the essence of camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration,” Sontag writes, adding that “camp sees everything in quotation marks.” It is something that ties together theatricality, irony, and, sometimes, a certain self-awareness. While the aforementioned director John Waters’s films know themselves to be camp (think a drag queen playing the matriarch of a suburban family), some 1930s musicals, for instance, are camp without meaning to be. Sontag divides it up into two neat categories for us: there is an accidental kind of camp, or “naive camp,” she says, and a more “deliberate camp,” that is aware of itself.

As for the link between camp and homosexuality, “it has to be explained,” muses Sontag (actually, she was going to call the essay “Notes on Homosexuality,” but later changed her mind). The dandy writer Oscar Wilde was an early forerunner of camp, she notes—hence why “Notes on ‘Camp,’ ” is dedicated to him—but of course there are many more examples. “While it’s not true that camp taste is homosexual taste,” writes Sontag, “there is no doubt a particular affinity and overlap.”

Reading Sontag’s essay as a 19-year-old, and one who was grappling with my sexuality, something seemed to slip into place. “Notes on ‘Camp’” not only helped me to grasp the meaning of camp or to explain a lot of my weird cultural tastes, but it gave me something extra. Just months after confronting all of the difficult feelings that came with sleeping with a girl for the first time, in camp, I felt like I had inherited a special gift, a secret language, a very particular kind of humor. Camp felt like a weapon to use against the world when I might find myself up against homophobia—a source of joy in difficult times. But on top of that, I had gained something else. In Sontag, I had found a new queer hero.

After I first read “Notes on ‘Camp,’ ” I went in search of Sontag’s other books, and found that, similarly, they made other intangible ideas feel tangible. They took on nebulous topics I had spent a lot of time thinking about but had struggled to theorize. Against Interpretation , which contains “Notes on ‘Camp’” and which was published in 1966, questions the ways that we are taught to respond to works of art, through thinking and feeling. On Photography (1977) looks at the complex relationship between photography and voyeurism, and Illness as Metaphor (1978) asks how and why we imbue certain illnesses with meaning. As I consumed her always considered, always eloquent writing, I noticed that Sontag seemed to give equal gravitas to what we might consider “high culture” and “low culture,” always keen to analyze the things that the rest of us think of as ordinary. This seemed to me like a good way of looking at the world. As her son, David, famously said of her: “My mother was someone who was interested in everything.”

But it wasn’t just through her writing that I got to know Sontag; it was through photographs, too. Of which there are many that stand out to me. One is the shot of her taken in New York City by Jill Krementz, in 1974, in which she is smoking a long, thin cigarette nonchalantly, and staring directly into the camera, holding our glare. Another is the beautiful and very well-known 1975 Peter Hujar portrait of a youthful-looking Sontag lying on the bed in a ribbed sweater, gazing upward absentmindedly. And then, of course, there are the images of her taken later in life, with her (practically trademarked) thick gray streak of hair jumping out of the frame, many of which were captured by her long-term lover, the renowned photographer Annie Leibovitz. To this day, the only thing that makes me feel OK about my own rapidly graying hair.

Sontag had a string of relationships with both men and women, but her relationship with Leibovitz was arguably her most significant. They met in 1989, when Leibovitz was taking Sontag’s headshot for the book AIDS and Its Metaphors , a follow-up to Illness as Metaphor , that examined the cultural connotations of the HIV virus, which was ravaging the New York City in which Sontag lived at the time. According to Benjamin Moser’s biography, Sontag , Sontag and Leibovitz instantly started a relationship, but when Sontag’s assistant asked her about it, she initially denied it, and bristled at the use of the term “lesbian,” saying that she didn’t like labels, particularly that one. From talking to countless people who knew the couple, Moser describes how Sontag was cruel to Leibovitz, mocking, patronizing, sometimes tormenting her.

Their relationship was the longest of Sontag’s life, lasting fifteen years, but both women were famously private about it, at least until after Sontag’s death in 2004. Controversially, in the autobiographical book A Photographer’s Life 1990–2005 , Leibovitz published photographs of Sontag naked, as well as images of a vulnerable, brittle Sontag in her hospital bed, not long before cancer (leukemia) took her life in 2004. That Sontag never came out publicly is something that she has been criticized for. But as the incredible New York writer, and Sontag’s friend, Fran Lebowitz says in the documentary Regarding Susan Sontag , “This is an unfair thing to say about anyone, but to me it’s an age thing—for someone my age it is a private thing . . . for someone my age it has to be a secret thing.” The gay American poet and cultural critic Wayne Koestenbaum, who is also in the documentary, takes another approach: “Does the author of ‘Notes on “Camp” ’ have to come out?” he asks.

From Sontag’s writing, it’s clear that she struggled with her own sexuality, but that this struggle drove her passion, her work: “My desire to write is connected to my homosexuality,” she wrote. “I need the identity as a weapon to match the weapon that society has against me. I am just becoming aware of how guilty I feel being queer.” These words have made me question why I have forged a career writing mostly about my own sexual identity as well as LGBTQ+ issues, whether it’s a kind of self-defense mechanism, or a way of owning my own narrative.

Choosing to only write about her sexuality privately suggests that Sontag was perhaps ashamed of this part of herself. Or perhaps she simply felt that her sexuality was no one else’s business. Or perhaps it was more complicated than that; Susan had a son, she was a very public figure, and she was often condescendingly labeled a “woman writer”—she may have felt compromised, or like she was up against enough already. Plus, to put things into perspective, she met Leibovitz at the height of the AIDS epidemic (highly stigmatized and described by some as the “gay disease”), homosexuality itself was still illegal in parts of America until as late as 2003, and Sontag was living in a time when there were very few gay or bisexual women in the public eye. Many people did know about her love life, of course, but for her to discuss it more openly may have impacted her career, her family, her personal relationships.

In many ways, Sontag was a victim of the time in which she lived, a time when same-sex love affairs were often shrouded in secrecy, when a lot of people lived “in the closet.” That David Rieff, Benjamin Moser, and Annie Leibovitz have exposed so much of Sontag’s intimate life since her death brings up ethical questions about a person’s right to privacy when they are no longer with us. But it has also given more of her queer history to the world, and in doing so has allowed people like me to discover her as a (complicated) role model, to think of her in the canon of great LGBTQ+ thinkers along with the likes of James Baldwin and Gertrude Stein. Sontag’s diaries remain a rare and honest testament to what it means to be a young woman falling in love with another woman for the very first time.

__________________________________

Adapted from The Queer Bible: Essays edited by Jack Guinness. Copyright 2021 © Amelia Abraham. To be published on June 15, 2021, by Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Adapted by permission.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Amelia Abraham

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

The Perks of Reading Across Genre as Both Bookseller and Writer

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Camp: Notes on Fashion

Exhibition Catalogue

With stunning new photography and insightful essays, this multifaceted two-volume set reveals how fashion embraces and flaunts the camp sensibility.

Exhibition Overview

Through more than 250 objects dating from the seventeenth century to the present, The Costume Institute's spring 2019 exhibition explores the origins of camp's exuberant aesthetic. Susan Sontag's 1964 essay "Notes on 'Camp'" provides the framework for the exhibition, which examines how the elements of irony, humor, parody, pastiche, artifice, theatricality, and exaggeration are expressed in fashion.

Accompanied by a catalogue .

Please note: Strollers are not allowed in this exhibition. Read about our admissions policy and plan your visit here .

Featured Media

"The historical journey is thoroughly engaging. . . . you don't stop thinking about it. It sticks with you and niggles in the brain." — New York Times

"A high-ceilinged, over-the-rainbow extravaganza" — Wall Street Journal

"The exhibition's expressions of humor and joy are sure to delight" — Washington Post

"Just might top 2018's extravaganza. . . . focused and cleverly thought out, offering an instructive journey. . . . entertaining and educative . . . the attentive visitor will relish in the many sensibilities of camp" — Independent

The exhibition is made possible by

Susan Sontag

(1933-2004)

What Is Susan Sontag Known For?

Susan Sontag was born on January 16, 1933, in New York City. In 1964, she gained recognition for her essay “Notes on Camp.” Sontag became widely known for her nonfiction works including Against Interpretation and Other Essays (1966), On Photography (1976) and Illness as Metaphor (1978), as well as for novels like The Volcano Lover (1992) and In America (2000), for which she won the National Book Award. Sontag died from cancer on December 28, 2004, in New York.

Early Life and Education

Susan Sontag was born on January 16, 1933, in New York, New York to Mildred and Jack Rosenblatt, with the couple later having a second daughter, Judith. Sontag’s father was a fur trader, and her parents lived overseas for his business while Sontag lived with her grandparents in New York. Sontag's father died when she was still a child. Her mother moved the family to milder climates because of Sontag’s asthma and they eventually relocated ato California. In 1945, Mildred married Air Corps captain Nathan Sontag, from whom a pre-teen Sontag would take her surname.

Sontag became an avid reader and learner. She graduated high school at the age of 15 and attended the University of California at Berkeley before transferring to the University of Chicago, where she met lecturer Philip Rieff. The two were married in less than two weeks after meeting and would have a son, David. Upon earning her bachelor’s in philosophy, Sontag went on to earn her master’s in English and philosophy at Harvard and did additional postgraduate work abroad at Oxford and the Sorbonne.

'Notes on Camp'

Sontag returned to the states by the late 1950s and opted to end her marriage with Rieff, moving to back to New York City with her son. She worked as a college instructor and began to make a name for herself as an essayist, writing for publications like The Nation and The New York Review of Books . A piece she wrote for The Parisian Review , “Notes on Camp,” earned her accolades. She had also been working on her debut novel, The Benefactor , released in 1963 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Sontag’s publisher for the duration of her career.

As an intellectual and a woman in what was still too often a boys’ club, Sontag challenged traditional notions of how art should be interpreted and consumed and what cultural tropes could receive serious scrutiny. She was a renaissance soul as known for everything from collections of nonfiction prose like Against Interpretation and Other Essays (1966) and On Photography (1977) to fiction like I, etcetera: Stories (1978) and The Volcano Lover (1992). She also wrote and directed films, including Duet for Cannibals (1969) and Letter from Venice (1981).

National Book Award

Sontag was the source of much controversy throughout her career, with critics looking at everything from her political statements (i.e. she once offered words of support for communist governments, changing her stance later on) to the amount of attention she received from the general media.

Relationships, Illness and Death

Though Sontag took on sexuality-based cultural criticism, she was generally private about her affairs and enjoyed intimate relationships with women, including Eva Kollisch and photographer Annie Leibovitz , with whom she collaborated on the book Women (1999).

Sontag was diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer in 1975. She detailed how myths around the disease can derail effective treatment in the book Illness as Metaphor (1978), later followed by another book about health and stigma, AIDS and Its Metaphors (1989).

Sontag died from a form of leukemia on December 28, 2004, in New York City. Her son David, who went on to become an editor and a writer as well, paid tribute to Sontag in the book Swimming in a Sea of Death: A Son’s Memoir (2008).

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Susan Sontag

- Birth Year: 1933

- Birth date: January 16, 1933

- Birth State: New York

- Birth City: New York City

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Female

- Best Known For: Susan Sontag was a critical essayist, cultural analyst, novelist and filmmaker. She wrote 'On Photography,' 'Illness as Metaphor,' 'The Volcano Lover' and 'In America,' among many other works.

- War and Militaries

- Education and Academia

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Fiction and Poetry

- Politics and Government

- Astrological Sign: Capricorn

- The Sorbonne

- Oxford College

- University of Chicago

- Harvard University

- Nacionalities

- Occupations

- Anti-War Activist

- Death Year: 2004

- Death date: December 28, 2004

- Death State: New York

- Death City: New York City

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Susan Sontag Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/susan-sontag

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: May 26, 2022

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- Literature was the passport to enter a larger life; that is the zone of freedom.

- I did have the idea that I’d like to have several lives, and it’s very hard to have several lives and then have a husband. … [S]omewhere along the line, one has to choose between the Life and the Project.

- If literature has engaged me as a project, it is as an extension of my sympathies to other selves, other domains, other dreams, other territories of concern.

- It never occurred to me that I would want to marry someone who didn't like someone who read a lot of books.

Womens Rights Activists

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Betty Friedan

Hillary Clinton

Gloria Steinem

30 Civil Rights Leaders of the Past and Present

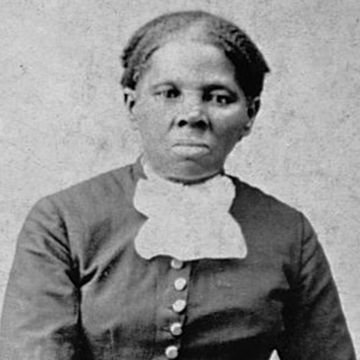

Harriet Tubman

Malala Yousafzai

Queen Rania

Clara Barton

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Against interpretation, and other essays

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

1,862 Views

57 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station33.cebu on February 24, 2020

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

File:Sontag Susan 1964 Notes on Camp.pdf

File history.

Sontag_Susan_1964_Notes_on_Camp.pdf (file size: 132 KB, MIME type: application/pdf )

Sontag, Susan. "Notes on camp." Camp: queer aesthetics and the performing subject: a reader (1964): 53-65.

Click on a date/time to view the file as it appeared at that time.

- You cannot overwrite this file.

The following 3 pages uses this file:

- Susan Sontag

- File:Sontag Notes on camp 1964.pdf (file redirect)

Navigation menu

Personal tools.

- Not logged in

- Contributions

- Create account

- Recent changes

- Recent files

- Batch upload

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

- Browse bases

- This page was last edited on 18 January 2016, at 15:55.

- Privacy policy

- About Monoskop

- Disclaimers

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

Camp Is Having a Moment on Television

Shows like palm royale , feud: capote vs. the swans , and the gilded age share a core sensibility..

The more you watch of Palm Royale —the new Apple TV+ show starring Kristen Wiig as a wannabe socialite trying to make it into the upper crust of 1969 Palm Beach, Florida—the more it may feel as if a microdose of LSD is starting to kick in.

Though Wiig’s sunny caricature of a Southern accent won me over from the pilot, I knew I was onto something special when, midway through the miniseries, Allison Janney’s queen bee falls in love with a beached whale while a handsome man soon falls, quite literally, from outer space. In what other show, pray tell, would we get to hear Wiig utter the magnificent lines “Take me right here on this ethnic rug. Go get your trumpet. I want you to play ‘Edelweiss’ in me real slow”? That’s right. I’ll wait.

Thanks to a sense of self-awareness and a commitment to not taking itself too seriously, Palm Royale is a fast, fun, and occasionally quite funny series that charts the efforts of Maxine (a brilliant Wiig, whose ditzy charm has rarely been better deployed) to break into high society at the eponymous Palm Royale beach club. Her chief rival is Evelyn (Janney), who is perpetually dressed in a series of stunning silk caftans while she sits atop the social milieu in the absence of Maxine’s ailing aunt-in-law Norma (comedy icon Carol Burnett, who proves she can still make us laugh with very few lines of discernible dialogue). The show begins to feel overstuffed in its later episodes, as Maxine and husband, Douglas (Josh Lucas), scramble to keep afloat in their new world, but it’s never boring.

In fact, Palm Royale shares a lot of its DNA with a certain other period series starring an ensemble of fabulous middle-aged women. I am talking, of course, about HBO’s The Gilded Age , albeit imbued with the pleasant lightheadedness of having downed a few poolside mai tais. Indeed, it seems that camp is having a moment on television: With the recent release of buzzy, star-studded shows like Palm Royale , FX’s Feud: Capote vs. The Swans , and the latest season of The Gilded Age , we are positively drowning in shows about the glitzy world of the well-to-do that I can only—facetiously, of course—describe as being catnip for a gay man with a streaming subscription.

There are obvious similarities between the three series. The Gilded Age follows the battle between new money and old in 1880s New York, while this latest addition to the Feud anthology is based on the fallout between writer Truman Capote and his bevy of wealthy female friends following his lampooning them in a gossipy 1975 essay . In all these shows, we follow groups of elite, wealthy, and catty women who are fighting to maintain their grip on social power to the exclusion of all others. In all these shows, the extravagances and intricacies of this moneyed class are both venerated and vilified. And in all these shows, the wardrobe budget is the real star.

But the similarities go beyond the surface, touching on a slippery sensibility that has been famously defined by Susan Sontag in her landmark 1964 essay “Notes on ‘Camp.’ ” First, Palm Royale and its ilk revel in the artifice, theatricality, and visual glamor of the rich worlds they inhabit—what Sontag referred to as “the spirit of extravagance.” That glamor is on display not only in the subjects’ lives and storylines but also in the style through which they are depicted on screen. There is nothing natural about the homes in which these wealthy characters reside, whether they be seaside belle epoque estates in Rhode Island decked out with murals of the sky, or warm Mediterranean Revival palazzos that are drowning in stuffed birds and fern wallpaper.

When we watch these shows, we’re tuning in as much for the over-the-top costumes and production design as for the plot. It’s what Sontag would call our “visual reward”—and boy are we rewarded. Indeed, the costumes in this season of Feud were so sumptuously camp that they were even highlighted in a New York Times style piece detailing how the show depicted Capote’s 1966 Black and White Ball and how designer Zac Posen re-created some of the gowns for New York’s high society ladies.

The very fact of the Times’ interest in a show like Feud (the brainchild of Ryan Murphy, the current king of TV melodrama, who prefers the word baroque over camp to describe his work) points to another element of camp in these series’ appeal: a unique blend of high-low culture. Contrast the chatter surrounding these shows with the reception of the long-running soap operas about the wealthy that were synonymous with the ’80s and ’90s, from Dynasty to The Young and the Restless to The Bold and the Beautiful . Those soaps were typically viewed as trash popular television, but this current slate of shows, while equally lavish, entertaining, and catty, are framed as prestige productions with big stars and bigger budgets. They take viewers into a high-culture world of exclusive balls, pricey art auctions, and martini luncheons, but through the historically low-culture medium of television. The stakes—box seats at the opera, beach club membership—are deadly serious for the characters, even as they are remarkably silly for us viewers. To cite Sontag, these shows are “serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious.”

However, there are different planes to camp. Sontag distinguished between “pure” or “naive” camp and “deliberate” camp, observing, “The pure examples of Camp are unintentional; they are dead serious.” Feud and Palm Royale fall more within the “deliberate” category, possessing some measure of fun and self-awareness (even if Murphy’s series does wallow in Capote’s addiction problems somewhat movingly, thanks mainly to a brilliant, preening performance by Tom Hollander). The Gilded Age , by contrast, must fall under peak camp by virtue of taking itself seriously. Although HBO’s period drama imagined itself to be sumptuous, important television, it failed spectacularly, particularly in its bloated, boring first season. But it was that failure—“the sensibility of failed seriousness,” per Sontag, in a production that had the “proper mixture of the exaggerated, the fantastic, the passionate, and the naive”—that also made it so wonderfully camp. In short, the perfect series for a large swath of cynical viewers who happily called it “the worst show on television ,” while still tuning in every week, addicted to hating it as much as they loved it.

There are plenty of other TV shows about the world of the wealthy and those trying to infiltrate it, but they don’t quite rest on the “innocence” that Sontag ascribed to camp. Netflix’s Ripley —the upcoming black-and-white adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley , starring Andrew Scott—is too dogged and dour; HBO’s Succession , while at times sardonic, had a jagged edge of seriousness; The White Lotus , although funny, was too consciously satirical to be camp. (I would argue, however, that Jennifer Coolidge’s award-winning turn as Tanya in both the first and second seasons was camp at its finest.)

There’s an ineffability to campiness, a special quality that you know when you see it. The best camp, just like the grasshopper cocktail that Wiig’s character sips throughout Palm Royale , may seem like a ridiculous order, but it goes down easy with just the right balance of alcohol and sugar. Just kick back, relax, and let the booze settle in.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Solzhenitsyn, Literary Giant Who Defied Soviets, Dies at 89

By Michael T. Kaufman

- Aug. 4, 2008

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, whose stubborn, lonely and combative literary struggles gained the force of prophecy as he revealed the heavy afflictions of Soviet Communism in some of the most powerful works of the 20th century, died late on Sunday at the age of 89 in Moscow.

His son Yermolai said the cause was a heart ailment.

Mr. Solzhenitsyn outlived by nearly 17 years the Soviet state and system he had battled through years of imprisonment, ostracism and exile.

Mr. Solzhenitsyn had been an obscure, middle-aged, unpublished high school science teacher in a provincial Russian town when he burst onto the literary stage in 1962 with “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.” The book, a mold-breaking novel about a prison camp inmate, was a sensation. Suddenly he was being compared to giants of Russian literature like Tolstoy, Dostoyevski and Chekhov.

Over the next five decades, Mr. Solzhenitsyn’s fame spread throughout the world as he drew upon his experiences of totalitarian duress to write evocative novels like “The First Circle” and “The Cancer Ward” and historical works like “The Gulag Archipelago.”

“Gulag” was a monumental account of the Soviet labor camp system, a chain of prisons that by Mr. Solzhenitsyn’s calculation some 60 million people had entered during the 20th century. The book led to his expulsion from his native land. George F. Kennan, the American diplomat, described it as “the greatest and most powerful single indictment of a political regime ever to be leveled in modern times.”

Mr. Solzhenitsyn was heir to a morally focused and often prophetic Russian literary tradition, and he looked the part. With his stern visage, lofty brow and full, Old Testament beard, he recalled Tolstoy while suggesting a modern-day Jeremiah, denouncing the evils of the Kremlin and later the mores of the West. He returned to Russia and deplored what he considered its spiritual decline, but in the last years of his life he embraced President Vladimir V. Putin as a restorer of Russia’s greatness.

In almost half a century, more than 30 million of his books have been sold worldwide and translated into some 40 languages. In 1970 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Mr. Solzhenitsyn owed his initial success to Khrushchev’s decision to allow “Ivan Denisovich” to be published in a popular journal. Khrushchev believed its publication would advance the liberal line he had promoted since his secret speech in 1956 on the crimes of Stalin.

But soon after the story appeared, Khrushchev was replaced by hard-liners, and they campaigned to silence its author. They stopped publication of his new works, denounced him as a traitor and confiscated his manuscripts.

A Giant and a Victim

Their iron grip could not contain Mr. Solzhenitsyn’s reach. By then his works were appearing outside the Soviet Union, in many languages, and he was being compared not only to Russia’s literary giants but also to Stalin’s literary victims, writers like Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelstam and Boris Pasternak.

At home, the Kremlin stepped up its campaign by expelling Mr. Solzhenitsyn from the Writer’s Union. He fought back. He succeeded in having microfilms of his banned manuscripts smuggled out of the Soviet Union. He addressed petitions to government organs, wrote open letters, rallied support among friends and artists, and corresponded with people abroad. They turned his struggles into one of the most celebrated cases of the cold war period.

Hundreds of well-known intellectuals signed petitions against his silencing; the names of left-leaning figures like Jean-Paul Sartre carried particular weight with Moscow. Other supporters included Graham Greene, Muriel Spark, W. H. Auden, Gunther Grass, Heinrich Boll, Yukio Mishima, Carlos Fuentes and, from the United States, Arthur Miller, John Updike, Truman Capote and Kurt Vonnegut. All joined a call for an international cultural boycott of the Soviet Union.

That position was confirmed when he was awarded the 1970 Nobel Prize in the face of Moscow’s protests. The Nobel jurists cited him for “the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature.”

Mr. Solzhenitsyn dared not travel to Stockholm to accept the prize for fear that the Soviet authorities would prevent him from returning. But his acceptance address was circulated widely. He recalled a time when “in the midst of exhausting prison camp relocations, marching in a column of prisoners in the gloom of bitterly cold evenings, with strings of camp lights glimmering through the darkness, we would often feel rising in our breast what we would have wanted to shout out to the whole world if only the whole world could have heard us.”

He wrote that while an ordinary man was obliged “not to participate in lies,” artists had greater responsibilities. “It is within the power of writers and artists to do much more: to defeat the lie!”

By this time, Mr. Solzhenitsyn had completed his own massive attempt at truthfulness, “The Gulag Archipelago.” In more than 300,000 words, he told the history of the Gulag prison camps, whose operations and rationale and even existence were subjects long considered taboo.

Publishers in Paris and New York had secretly received the manuscript on microfilm. But wanting the book to appear first in the Soviet Union, Mr. Solzhenitsyn asked them to put off publishing it. Then, in September 1973, he changed his mind. He had learned that the Soviet spy agency, the KGB, had unearthed a buried copy of the book after interrogating his typist, Elizaveta Voronyanskaya, and that she had hung herself soon afterward.

He went on the offensive. With his approval, the book was speedily published in Paris, in Russian, just after Christmas. The Soviet government counterattacked with a spate of articles, including one in Pravda, the state-run newspaper, headlined “The Path of a Traitor.” He and his family were followed, and he received death threats.

On Feb. 12, 1974, he was arrested. The next day, he was told that he was being deprived of his citizenship and deported. On his arrest, he had been careful to take with him a threadbare cap and a shabby sheepskin coat that he had saved from his years in exile. He wore them both as he was marched onto an Aeroflot flight to Frankfurt.

Mr. Solzhenitsyn was welcomed by the German novelist Heinrich Böll. Six weeks after his expulsion, Mr. Solzhenitsyn was joined by his wife, Natalia Svetlova, and their three sons. She had played a critical role in organizing his notes and transmitting his manuscripts. After a short stay in Switzerland, the family moved to the United States, settling in the hamlet of Cavendish, Vt.

There he kept mostly to himself for some 18 years, protected from sightseers by neighbors, who posted a sign saying, “No Directions to the Solzhenitsyns.” He kept writing and thinking a great deal about Russia and hardly at all about his new environment, so certain was he that he would return to his homeland one day.

His rare public appearances could turn into hectoring jeremiads. Delivering the commencement address at Harvard in 1978, he called the country of his sanctuary spiritually weak and mired in vulgar materialism. Americans, he said, speaking in Russian through a translator, were cowardly. Few were willing to die for their ideals, he said. He condemned both the United States government and American society for its “hasty” capitulation in Vietnam. And he criticized the country’s music as intolerable and attacked its unfettered press, accusing it of violations of privacy.

Many in the West did not know what to make of the man. He was perceived as a great writer and hero who had defied the Russian authorities. Yet he seemed willing to lash out at everyone else as well democrats, secularists, capitalists, liberals and consumers.

David Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker, who has written extensively about the Soviet Union and visited Mr. Solzhenitsyn, wrote in 2001: “In terms of the effect he has had on history, Solzhenitsyn is the dominant writer of the 20th century. Who else compares? Orwell? Koestler? And yet when his name comes up now, it is more often than not as a freak, a monarchist, an anti-Semite, a crank, a has been.”

In the 1970s, Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger warned President Gerald R. Ford to avoid seeing Mr. Solzhenitsyn. “Solzhenitsyn is a notable writer, but his political views are an embarrassment even to his fellow dissidents,” Mr. Kissinger wrote in a memo. “Not only would a meeting with the president offend the Soviets, but it would raise some controversy about Solzhenitsyn’s views of the United States and its allies.” Mr. Ford followed the advice.

The writer Susan Sontag recalled a conversation about Mr. Solzhenitsyn between her and Joseph Brodsky, the Russian poet who had followed Mr. Solzhenitsyn into forced exile and who would also become a Nobel laureate. “We were laughing and agreeing about how we thought Solzhenitsyn’s views on the United States, his criticism of the press, and all the rest were deeply wrong, and on and on,” she said. “And then Joseph said: ‘But you know, Susan, everything Solzhenitsyn says about the Soviet Union is true. Really, all those numbers 60 million victims it’s all true.’ “

Ivan Denisovich

In the autumn of 1961, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was a 43-year-old high school teacher of physics and astronomy in Ryazan, a city some 70 miles south of Moscow. He had been there since 1956, when his sentence of perpetual exile in a dusty region of Kazakhstan was suspended. Aside from his teaching duties, he was writing and rewriting stories he had conceived while confined in prisons and labor camps since 1944.

One story, a short novel, was “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich,” an account of a single day in an icy prison camp written in the voice of an inmate named Ivan Denisovich Shukov, a bricklayer. With little sentimentality, he recounts the trials and sufferings of “zeks,” as the prisoners were known, peasants who were willing to risk punishment and pain as they seek seemingly small advantages like a few more minutes before a fire. He also reveals their survival skills, their loyalty to their work brigade and their pride.

The day ends with the prisoner in his bunk. “Shukov felt pleased with his life as he went to sleep,” Mr. Solzhenitsyn wrote. Shukov was pleased because, among other things, he had not been put in an isolation cell, and his brigade had avoided a work assignment in a place unprotected from the bitter wind, and he had swiped some extra gruel, and had been able to buy a bit of tobacco from another prisoner.

“The end of an unclouded day. Almost a happy one,” Mr. Solzhenitsyn wrote, adding: “Just one of the 3,653 days of his sentence, from bell to bell. The extra three days were for leap years.”

Mr. Solzhenitsyn typed the story single spaced, using both sides to save paper. He sent one copy to Lev Kopelev, an intellectual with whom he had shared a cell 16 years earlier. Mr. Kopelev, who later became a well known dissident, realized that under Khrushchev’s policies of liberalization, it might be possible to have the story published by Novy Mir , or The New World, the most prestigious of the Soviet Union’s so-called thick literary and cultural journals. Mr. Kopelev and his colleagues steered the manuscript around lower editors who might have blocked its publication and took it to Aleksandr Tvardovsky, the editor and a Politburo member who backed Khrushchev.

On reading the manuscript, Mr. Tvardovsky summoned Mr. Solzhenitsyn from Ryazan. “You have written a marvelous thing,” he told him. “You have described only one day, and yet everything there is to say about prison has been said.” He likened the story to Tolstoy’s moral tales. Other editors compared it to Dostoyevski’s “House of the Dead,” which the author had based on his own experience of incarceration in czarist times. Mr. Tvardovsky offered Mr. Solzhenitsyn a contract worth more than twice his teacher’s annual salary, but he cautioned that he was not certain he could publish the story.

Mr. Tvardovsky was eventually able to get Khrushchev himself to read “One Day in the Life.” Khrushchev was impressed, and by mid-October 1962, the presidium of the Politburo took up the question of whether to allow it to be published. The presidium ultimately agreed, and in his biography “Solzhenitsyn” (Norton, 1985), Michael Scammell wrote that Khrushchev defended the decision and was reported to have declared: “There’s a Stalinist in each of you; there’s even a Stalinist in me. We must root out this evil.”

The novel appeared in Novy Mir in early 1962. The critic Kornei Chukovsky pronounced the work “a literary miracle.” Grigori Baklanov, a respected novelist and writer about World War II, declared that the story was one of those rare creations after which “it is impossible to go on writing as one did before.”

Novy Mir ordered extra printings, and every copy was sold. A book edition and an inexpensive newspaper version also vanished from the shelves.

Mr. Solzhenitsyn was not the first to write about the camps. As early as 1951, Gustav Herling, a Pole, had published “A World Apart,” about the three years he spent in a labor camp on the White Sea. Some Soviet writers had typed accounts of their own experiences, and these pages and their carbon copies were passed from reader to reader in a clandestine, self-publishing effort called zamizdat. Given the millions who had been forced into the gulag, few families could have been unaware of the camp experiences of relatives or friends. But few had had access to these accounts. “One Day in the Life” changed that.

Mikhail S. Gorbachev, the last Soviet president, said on Monday that Mr. Solzhenitsyn was “a man with a unique life story whose name will endure throughout the history of Russia.”

“Severe trials befell Solzhenitsyn, as they did millions of other people in this country,” Mr. Gorbachev said in an interview with the Interfax news agency. “He was among the first to speak out about the brutality of Stalin’s regime and about the people who experienced it, but were not crushed.”

Mr. Solzhenitsyn’s books “changed the minds of millions of people, making them rethink their past and present,” Mr. Gorbachev said.

Born With the Russian Revolution

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn was born in the Caucasus spa town of Kislovodsk on Dec. 11, 1918, a year after the Russian Revolution began. His father, Isaaki, had been a Russian artillery officer on the German front and married to Taissa Shcherback by the brigade priest. Shortly after he was demobilized and six months before his son’s birth, he was killed in a hunting accident. The young widow took the child to Rostov-on-Don, where she reared him while working as a typist and stenographer. By Mr. Solzhenitsyn’s account, he and his mother lived in a dilapidated hut. Still, her class origins she was the daughter of a Ukrainian land owner were considered suspect, as was her knowledge of English and French. Mr. Solzhenitsyn remembered her burying his father’s three war medals because they could indicate reactionary beliefs.

He was religious. When he was a child, older boys once ripped a cross from his neck. Nonetheless, at 12, though the Communists repudiated religion, he joined the Young Pioneers and later became a member of Komsomol, the Communist youth organization.

He was a good student with an aptitude for mathematics, though from adolescence he imagined becoming a writer. In 1941, a few days before Germany attacked Russia to expand World War II into Soviet territory, he graduated from Rostov University with a degree in physics and math. A year earlier, he had married Natalia Reshetovskaya, a chemist. When hostilities began, he joined the army and was assigned to look after horses and wagons before being transferred to artillery school. He spent three years in combat as a commander of a reconnaissance battery.

In February 1945, as the war in Europe drew to a close, he was arrested on the East Prussian front by agents of Smersh, the Soviet spy agency. The evidence against him was found in a letter to a school friend in which he referred to Stalin disrespectfully, the authorities said as “the man with the mustache.” Though he was a loyal Communist, he was sentenced to eight years in a labor camp. It was his entry into the vast network of punitive institutions that he would later name the Gulag Archipelago, after the Russian acronym for the Main Administration of Camps.

His penal journey began with stays in two prisons in Moscow. Then he was transferred to a camp nearby, where he moved timbers, and then to another, called New Jerusalem, where he dug clay. From there he was taken to a camp called Kaluga Gate, where he suffered a moral and spiritual breakdown after equivocating in his response to a warden’s demand that he report on fellow inmates. Though he never provided information, he referred to his nine months there as the low point in his life.

After brief stays in several other institutions, Mr. Solzhenitsyn was moved to Special Prison No. 16 on the outskirts of Moscow on July 9, 1947. This was a so-called sharashka, an institution for inmates who were highly trained scientists and whose forced labor involved advanced scientific research. He was put there because of his gift for mathematics, which he credited with saving his life. “Probably I would not have survived eight years of the camps if as a mathematician I had not been assigned for three years to a sharashka.” His experiences at No. 16 provided the basis for his novel “The First Circle,” which was not published outside the Soviet Union until 1968. While incarcerated at the research institute, he formed close friendships with Mr. Kopelev and another inmate, Dmitry Panin, and later modeled the leading characters of “The First Circle” on them.

Granted relative freedom within the institute, the three would meet each night to carry on intellectual discussions and debate. During the day, Mr. Solzhenitsyn was assigned to work on an electronic voice-recognition project with applications toward coding messages. In his spare time, he began to write for himself: poems, sketches and outlines of books.

He also tended toward outspokenness, and it soon undid him. After scorning the scientific work of the colonel who headed the institute, Mr. Solzhenitsyn was banished to a desolate penal camp in Kazakhstan called Ekibastuz. It would become the inspiration for “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.”

At Ekibastuz, any writing would be seized as contraband. So he devised a method that enabled him to retain even long sections of prose. After seeing Lithuanian Catholic prisoners fashion rosaries out of beads made from chewed bread, he asked them to make a similar chain for him, but with more beads. In his hands, each bead came to represent a passage that he would repeat to himself until he could say it without hesitation. Only then would he move on to the next bead. He later wrote that by the end of his prison term, he had committed to memory 12,000 lines in this way.

‘Perpetual Exile’