Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

1. americans’ views on whether, and in what circumstances, abortion should be legal.

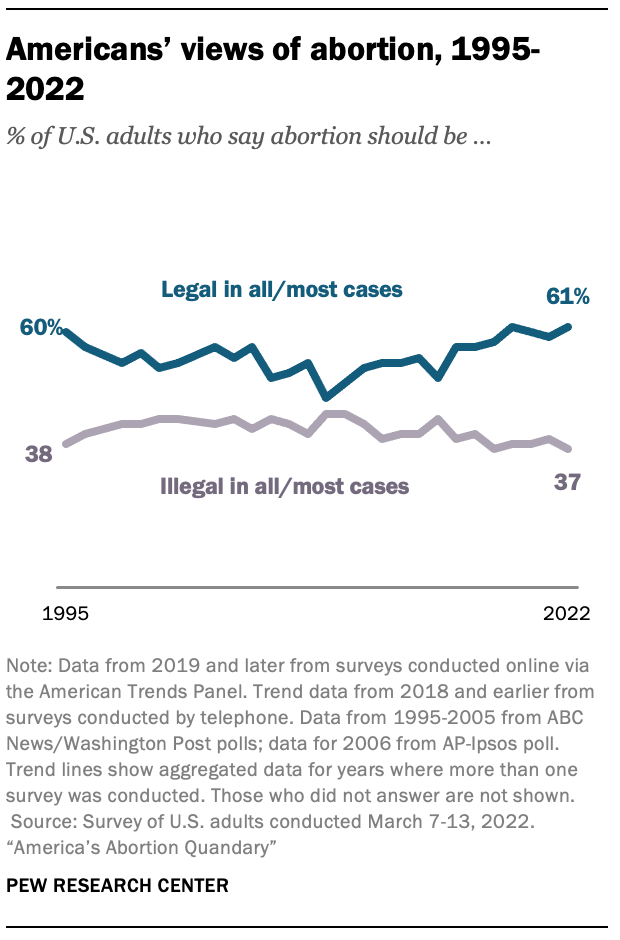

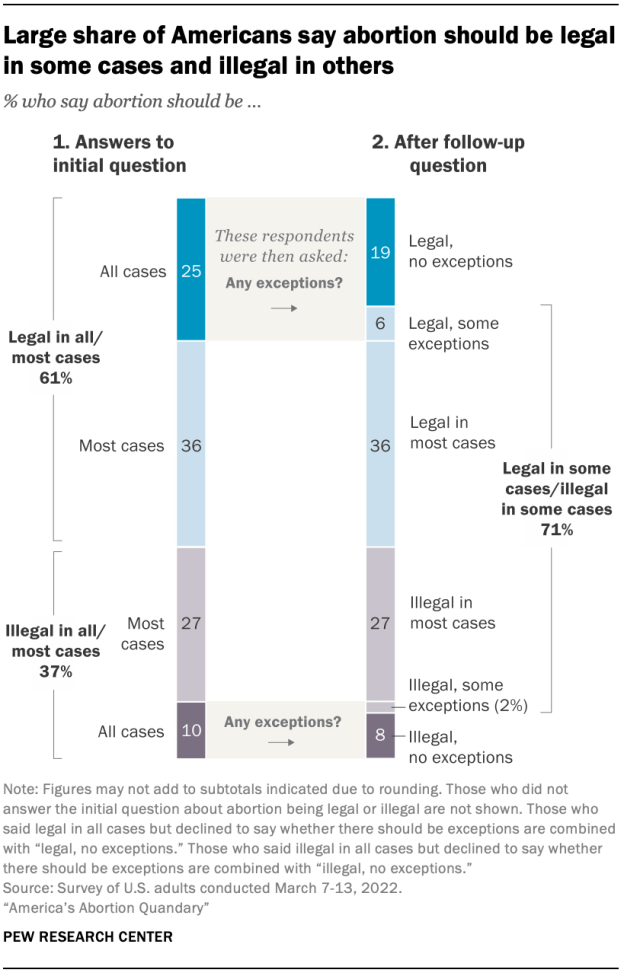

As the long-running debate over abortion reaches another key moment at the Supreme Court and in state legislatures across the country , a majority of U.S. adults continue to say that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. About six-in-ten Americans (61%) say abortion should be legal in “all” or “most” cases, while 37% think abortion should be illegal in all or most cases. These views have changed little over the past several years: In 2019, for example, 61% of adults said abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while 38% said it should be illegal in all or most cases. Most respondents in the new survey took one of the middle options when first asked about their views on abortion, saying either that abortion should be legal in most cases (36%) or illegal in most cases (27%).

Respondents who said abortion should either be legal in all cases or illegal in all cases received a follow-up question asking whether there should be any exceptions to such laws. Overall, 25% of adults initially said abortion should be legal in all cases, but about a quarter of this group (6% of all U.S. adults) went on to say that there should be some exceptions when abortion should be against the law.

One-in-ten adults initially answered that abortion should be illegal in all cases, but about one-in-five of these respondents (2% of all U.S. adults) followed up by saying that there are some exceptions when abortion should be permitted.

Altogether, seven-in-ten Americans say abortion should be legal in some cases and illegal in others, including 42% who say abortion should be generally legal, but with some exceptions, and 29% who say it should be generally illegal, except in certain cases. Much smaller shares take absolutist views when it comes to the legality of abortion in the U.S., maintaining that abortion should be legal in all cases with no exceptions (19%) or illegal in all circumstances (8%).

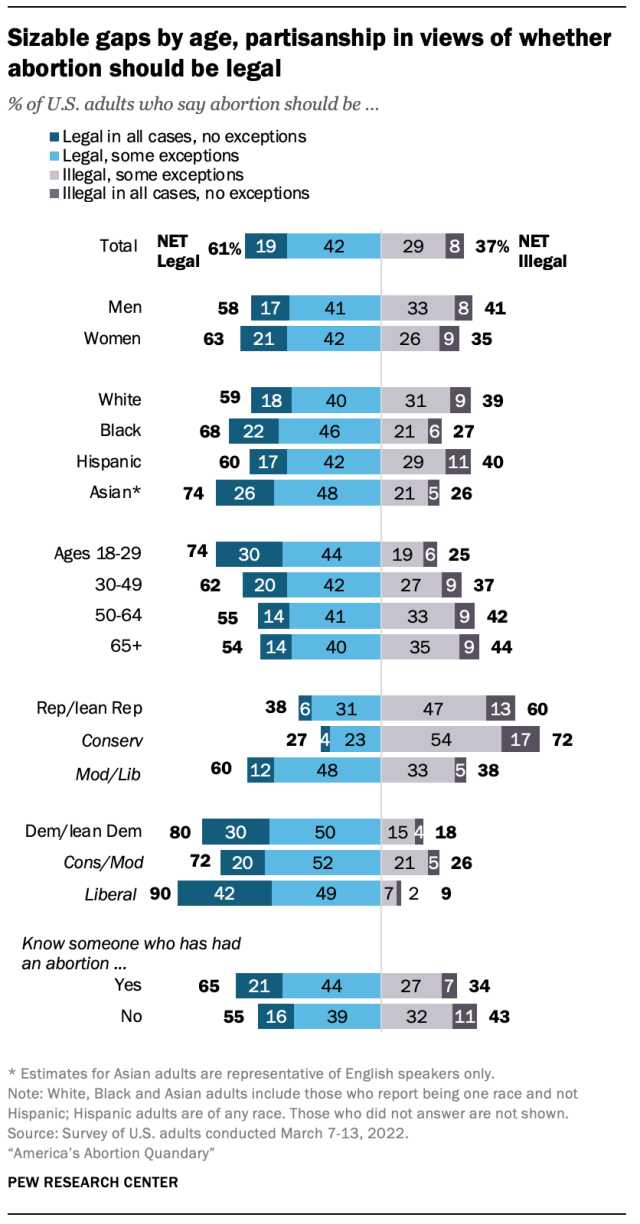

There is a modest gender gap in views of whether abortion should be legal, with women slightly more likely than men to say abortion should be legal in all cases or in all cases but with some exceptions (63% vs. 58%).

Younger adults are considerably more likely than older adults to say abortion should be legal: Three-quarters of adults under 30 (74%) say abortion should be generally legal, including 30% who say it should be legal in all cases without exception.

But there is an even larger gap in views toward abortion by partisanship: 80% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, compared with 38% of Republicans and GOP leaners. Previous Center research has shown this gap widening over the past 15 years.

Still, while partisans diverge in views of whether abortion should mostly be legal or illegal, most Democrats and Republicans do not view abortion in absolutist terms. Just 13% of Republicans say abortion should be against the law in all cases without exception; 47% say it should be illegal with some exceptions. And while three-in-ten Democrats say abortion should be permitted in all circumstances, half say it should mostly be legal – but with some exceptions.

There also are sizable divisions within both partisan coalitions by ideology. For instance, while a majority of moderate and liberal Republicans say abortion should mostly be legal (60%), just 27% of conservative Republicans say the same. Among Democrats, self-described liberals are twice as apt as moderates and conservatives to say abortion should be legal in all cases without exception (42% vs. 20%).

Regardless of partisan affiliation, adults who say they personally know someone who has had an abortion – such as a friend, relative or themselves – are more likely to say abortion should be legal than those who say they do not know anyone who had an abortion.

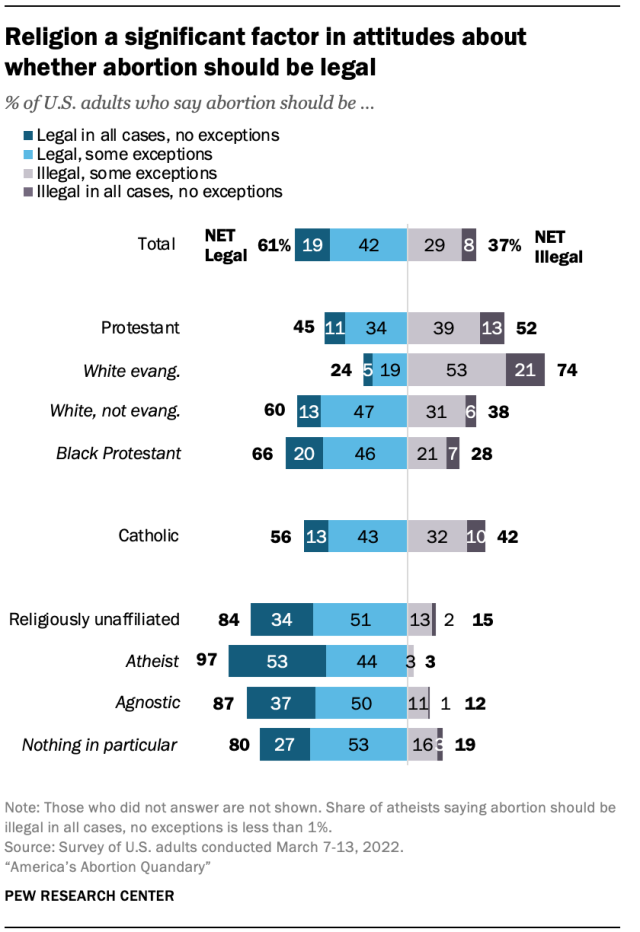

Views toward abortion also vary considerably by religious affiliation – specifically among large Christian subgroups and religiously unaffiliated Americans.

For example, roughly three-quarters of White evangelical Protestants say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases. This is far higher than the share of White non-evangelical Protestants (38%) or Black Protestants (28%) who say the same.

Despite Catholic teaching on abortion , a slim majority of U.S. Catholics (56%) say abortion should be legal. This includes 13% who say it should be legal in all cases without exception, and 43% who say it should be legal, but with some exceptions.

Compared with Christians, religiously unaffiliated adults are far more likely to say abortion should be legal overall – and significantly more inclined to say it should be legal in all cases without exception. Within this group, atheists stand out: 97% say abortion should be legal, including 53% who say it should be legal in all cases without exception. Agnostics and those who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” also overwhelmingly say that abortion should be legal, but they are more likely than atheists to say there are some circumstances when abortion should be against the law.

Although the survey was conducted among Americans of many religious backgrounds, including Jews, Muslims, Buddhists and Hindus, it did not obtain enough respondents from non-Christian groups to report separately on their responses.

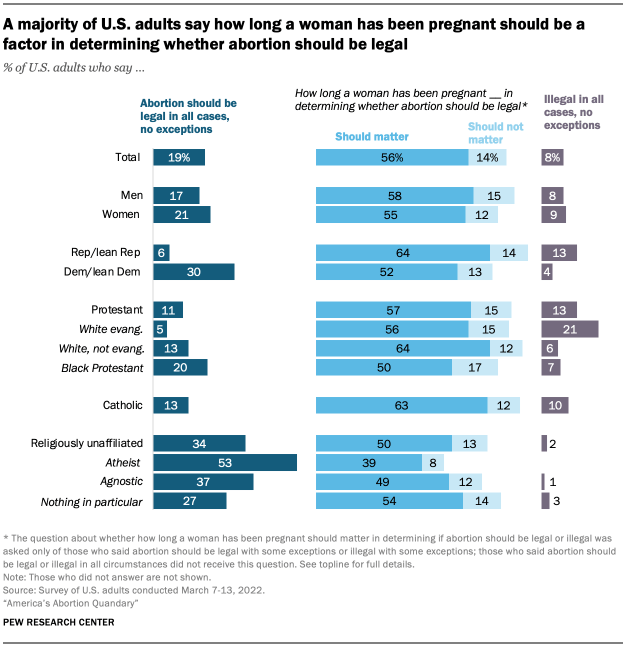

Abortion at various stages of pregnancy

As a growing number of states debate legislation to restrict abortion – often after a certain stage of pregnancy – Americans express complex views about when abortion should generally be legal and when it should be against the law. Overall, a majority of adults (56%) say that how long a woman has been pregnant should matter in determining when abortion should be legal, while far fewer (14%) say that this should not be a factor. An additional one-quarter of the public says that abortion should either be legal (19%) or illegal (8%) in all circumstances without exception; these respondents did not receive this question.

Among men and women, Republicans and Democrats, and Christians and religious “nones” who do not take absolutist positions about abortion on either side of the debate, the prevailing view is that the stage of the pregnancy should be a factor in determining whether abortion should be legal.

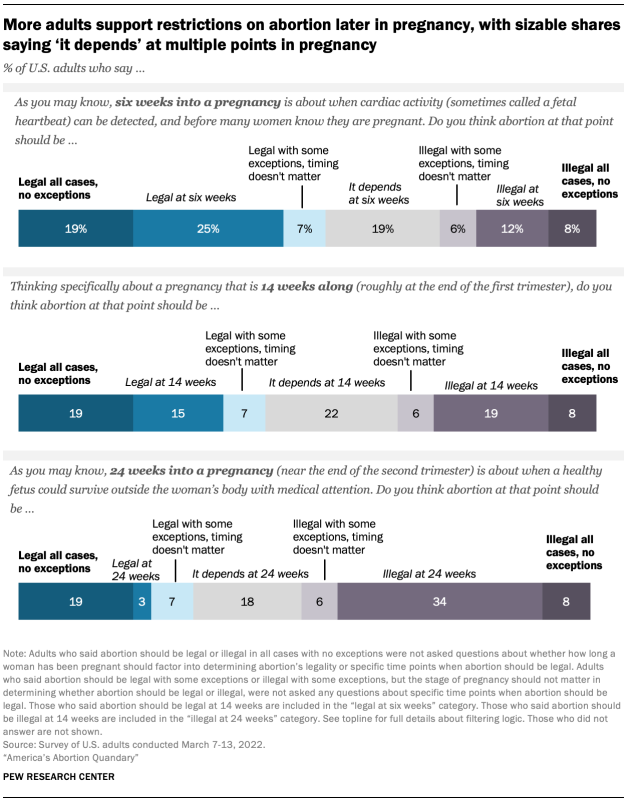

Americans broadly are more likely to favor restrictions on abortion later in pregnancy than earlier in pregnancy. Many adults also say the legality of abortion depends on other factors at every stage of pregnancy.

One-in-five Americans (21%) say abortion should be illegal at six weeks. This includes 8% of adults who say abortion should be illegal in all cases without exception as well as 12% of adults who say that abortion should be illegal at this point. Additionally, 6% say abortion should be illegal in most cases and how long a woman has been pregnant should not matter in determining abortion’s legality. Nearly one-in-five respondents, when asked whether abortion should be legal six weeks into a pregnancy, say “it depends.”

Americans are more divided about what should be permitted 14 weeks into a pregnancy – roughly at the end of the first trimester – although still, more people say abortion should be legal at this stage (34%) than illegal (27%), and about one-in-five say “it depends.”

Fewer adults say abortion should be legal 24 weeks into a pregnancy – about when a healthy fetus could survive outside the womb with medical care. At this stage, 22% of adults say abortion should be legal, while nearly twice as many (43%) say it should be illegal . Again, about one-in-five adults (18%) say whether abortion should be legal at 24 weeks depends on other factors.

Respondents who said that abortion should be illegal 24 weeks into a pregnancy or that “it depends” were asked a follow-up question about whether abortion at that point should be legal if the pregnant woman’s life is in danger or the baby would be born with severe disabilities. Most who received this question say abortion in these circumstances should be legal (54%) or that it depends on other factors (40%). Just 4% of this group maintained that abortion should be illegal in this case.

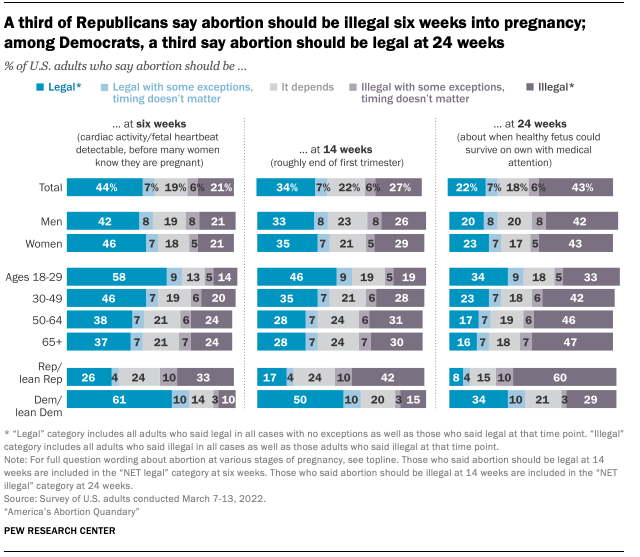

This pattern in views of abortion – whereby more favor greater restrictions on abortion as a pregnancy progresses – is evident across a variety of demographic and political groups.

Democrats are far more likely than Republicans to say that abortion should be legal at each of the three stages of pregnancy asked about on the survey. For example, while 26% of Republicans say abortion should be legal at six weeks of pregnancy, more than twice as many Democrats say the same (61%). Similarly, while about a third of Democrats say abortion should be legal at 24 weeks of pregnancy, just 8% of Republicans say the same.

However, neither Republicans nor Democrats uniformly express absolutist views about abortion throughout a pregnancy. Republicans are divided on abortion at six weeks: Roughly a quarter say it should be legal (26%), while a similar share say it depends (24%). A third say it should be illegal.

Democrats are divided about whether abortion should be legal or illegal at 24 weeks, with 34% saying it should be legal, 29% saying it should be illegal, and 21% saying it depends.

There also is considerable division among each partisan group by ideology. At six weeks of pregnancy, just one-in-five conservative Republicans (19%) say that abortion should be legal; moderate and liberal Republicans are twice as likely as their conservative counterparts to say this (39%).

At the same time, about half of liberal Democrats (48%) say abortion at 24 weeks should be legal, while 17% say it should be illegal. Among conservative and moderate Democrats, the pattern is reversed: A plurality (39%) say abortion at this stage should be illegal, while 24% say it should be legal.

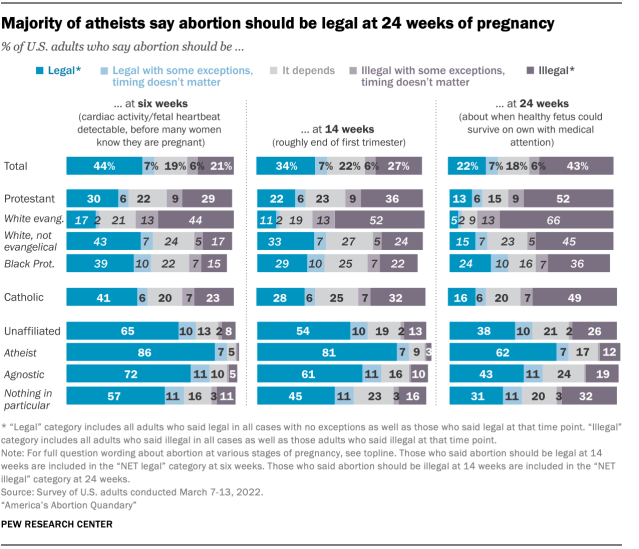

Christian adults are far less likely than religiously unaffiliated Americans to say abortion should be legal at each stage of pregnancy.

Among Protestants, White evangelicals stand out for their opposition to abortion. At six weeks of pregnancy, for example, 44% say abortion should be illegal, compared with 17% of White non-evangelical Protestants and 15% of Black Protestants. This pattern also is evident at 14 and 24 weeks of pregnancy, when half or more of White evangelicals say abortion should be illegal.

At six weeks, a plurality of Catholics (41%) say abortion should be legal, while smaller shares say it depends or it should be illegal. But by 24 weeks, about half of Catholics (49%) say abortion should be illegal.

Among adults who are religiously unaffiliated, atheists stand out for their views. They are the only group in which a sizable majority says abortion should be legal at each point in a pregnancy. Even at 24 weeks, 62% of self-described atheists say abortion should be legal, compared with smaller shares of agnostics (43%) and those who say their religion is “nothing in particular” (31%).

As is the case with adults overall, most religiously affiliated and religiously unaffiliated adults who originally say that abortion should be illegal or “it depends” at 24 weeks go on to say either it should be legal or it depends if the pregnant woman’s life is in danger or the baby would be born with severe disabilities. Few (4% and 5%, respectively) say abortion should be illegal at 24 weeks in these situations.

Abortion and circumstances of pregnancy

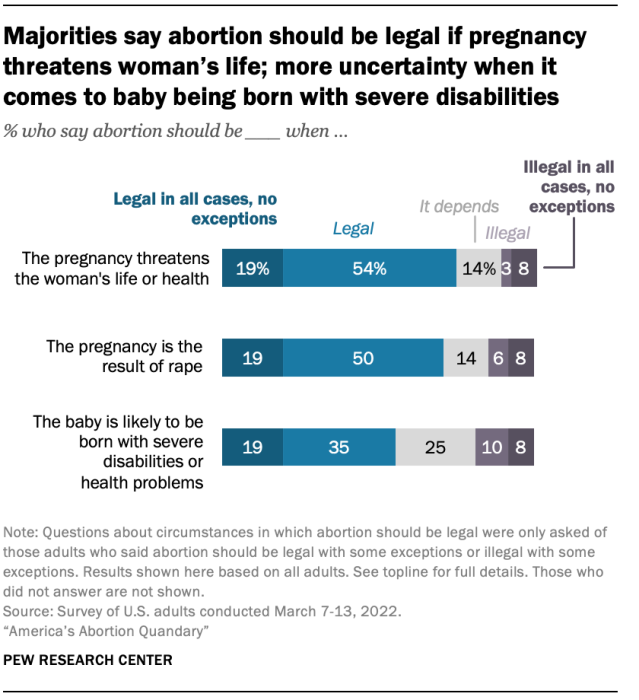

The stage of the pregnancy is not the only factor that shapes people’s views of when abortion should be legal. Sizable majorities of U.S. adults say that abortion should be legal if the pregnancy threatens the life or health of the pregnant woman (73%) or if pregnancy is the result of rape (69%).

There is less consensus when it comes to circumstances in which a baby may be born with severe disabilities or health problems: 53% of Americans overall say abortion should be legal in such circumstances, including 19% who say abortion should be legal in all cases and 35% who say there are some situations where abortions should be illegal, but that it should be legal in this specific type of case. A quarter of adults say “it depends” in this situation, and about one-in-five say it should be illegal (10% who say illegal in this specific circumstance and 8% who say illegal in all circumstances).

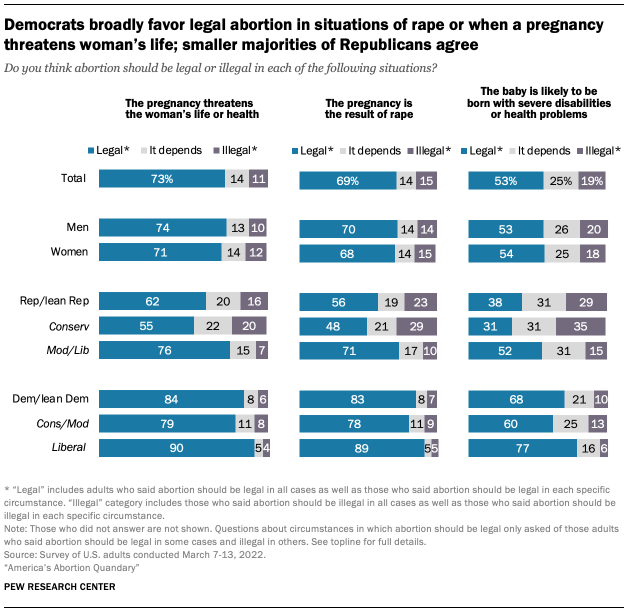

There are sizable divides between and among partisans when it comes to views of abortion in these situations. Overall, Republicans are less likely than Democrats to say abortion should be legal in each of the three circumstances outlined in the survey. However, both partisan groups are less likely to say abortion should be legal when the baby may be born with severe disabilities or health problems than when the woman’s life is in danger or the pregnancy is the result of rape.

Just as there are wide gaps among Republicans by ideology on whether how long a woman has been pregnant should be a factor in determining abortion’s legality, there are large gaps when it comes to circumstances in which abortions should be legal. For example, while a clear majority of moderate and liberal Republicans (71%) say abortion should be permitted when the pregnancy is the result of rape, conservative Republicans are more divided. About half (48%) say it should be legal in this situation, while 29% say it should be illegal and 21% say it depends.

The ideological gaps among Democrats are slightly less pronounced. Most Democrats say abortion should be legal in each of the three circumstances – just to varying degrees. While 77% of liberal Democrats say abortion should be legal if a baby will be born with severe disabilities or health problems, for example, a smaller majority of conservative and moderate Democrats (60%) say the same.

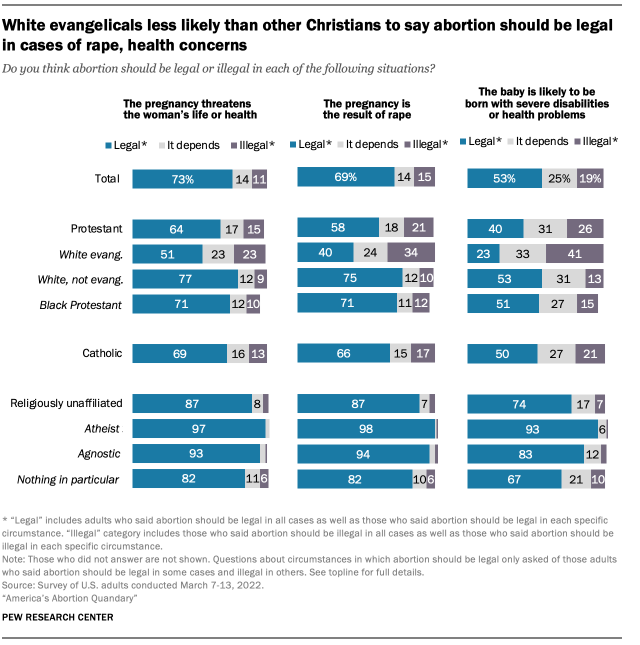

White evangelical Protestants again stand out for their views on abortion in various circumstances; they are far less likely than White non-evangelical or Black Protestants to say abortion should be legal across each of the three circumstances described in the survey.

While about half of White evangelical Protestants (51%) say abortion should be legal if a pregnancy threatens the woman’s life or health, clear majorities of other Protestant groups and Catholics say this should be the case. The same pattern holds in views of whether abortion should be legal if the pregnancy is the result of rape. Most White non-evangelical Protestants (75%), Black Protestants (71%) and Catholics (66%) say abortion should be permitted in this instance, while White evangelicals are more divided: 40% say it should be legal, while 34% say it should be illegal and about a quarter say it depends.

Mirroring the pattern seen among adults overall, opinions are more varied about a situation where a baby might be born with severe disabilities or health issues. For instance, half of Catholics say abortion should be legal in such cases, while 21% say it should be illegal and 27% say it depends on the situation.

Most religiously unaffiliated adults – including overwhelming majorities of self-described atheists – say abortion should be legal in each of the three circumstances.

Parental notification for minors seeking abortion

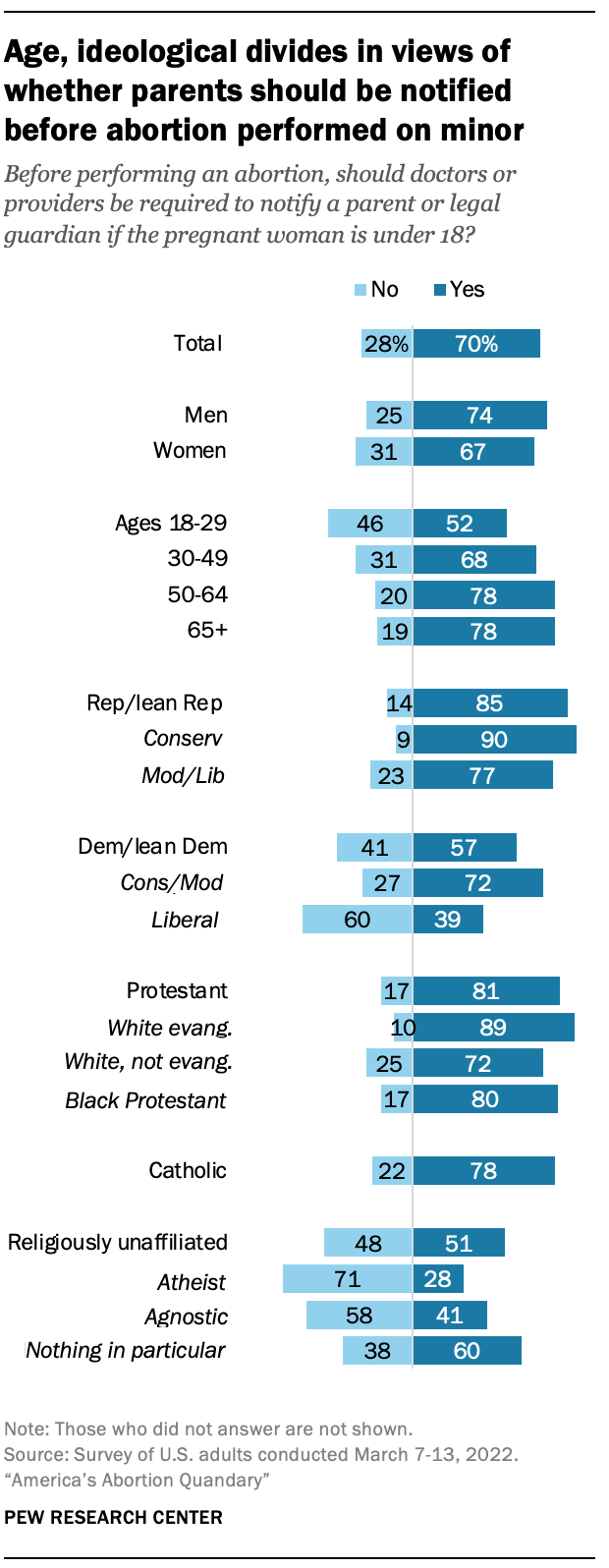

Seven-in-ten U.S. adults say that doctors or other health care providers should be required to notify a parent or legal guardian if the pregnant woman seeking an abortion is under 18, while 28% say they should not be required to do so.

Women are slightly less likely than men to say this should be a requirement (67% vs. 74%). And younger adults are far less likely than those who are older to say a parent or guardian should be notified before a doctor performs an abortion on a pregnant woman who is under 18. In fact, about half of adults ages 18 to 24 (53%) say a doctor should not be required to notify a parent. By contrast, 64% of adults ages 25 to 29 say doctors should be required to notify parents of minors seeking an abortion, as do 68% of adults ages 30 to 49 and 78% of those 50 and older.

A large majority of Republicans (85%) say that a doctor should be required to notify the parents of a minor before an abortion, though conservative Republicans are somewhat more likely than moderate and liberal Republicans to take this position (90% vs. 77%).

The ideological divide is even more pronounced among Democrats. Overall, a slim majority of Democrats (57%) say a parent should be notified in this circumstance, but while 72% of conservative and moderate Democrats hold this view, just 39% of liberal Democrats agree.

By and large, most Protestant (81%) and Catholic (78%) adults say doctors should be required to notify parents of minors before an abortion. But religiously unaffiliated Americans are more divided. Majorities of both atheists (71%) and agnostics (58%) say doctors should not be required to notify parents of minors seeking an abortion, while six-in-ten of those who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” say such notification should be required.

Penalties for abortions performed illegally

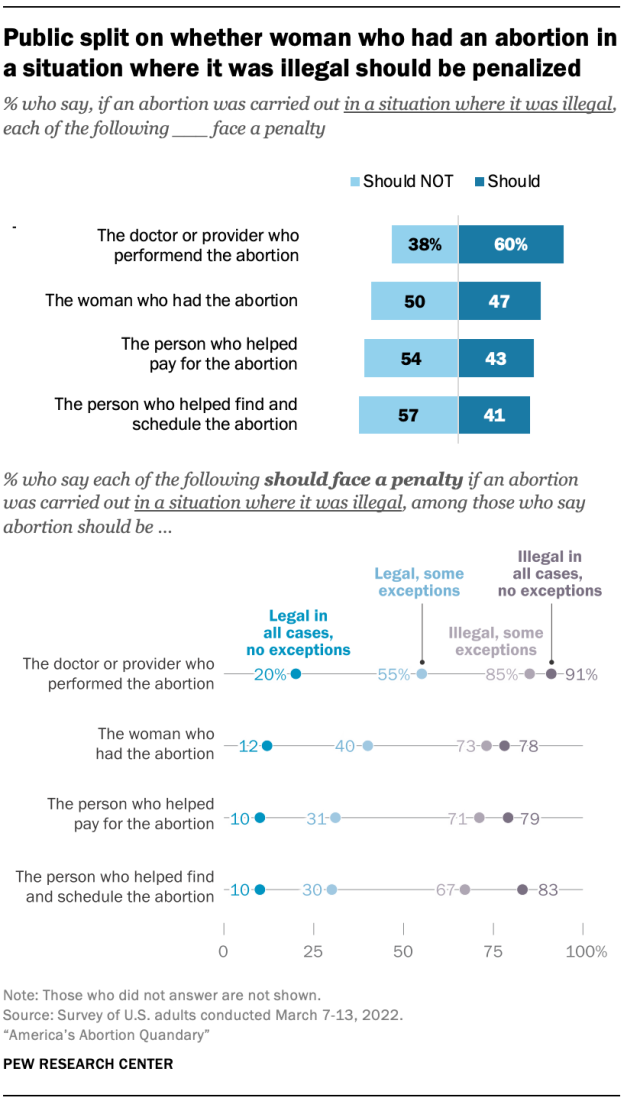

Americans are divided over who should be penalized – and what that penalty should be – in a situation where an abortion occurs illegally.

Overall, a 60% majority of adults say that if a doctor or provider performs an abortion in a situation where it is illegal, they should face a penalty. But there is less agreement when it comes to others who may have been involved in the procedure.

While about half of the public (47%) says a woman who has an illegal abortion should face a penalty, a nearly identical share (50%) says she should not. And adults are more likely to say people who help find and schedule or pay for an abortion in a situation where it is illegal should not face a penalty than they are to say they should.

Views about penalties are closely correlated with overall attitudes about whether abortion should be legal or illegal. For example, just 20% of adults who say abortion should be legal in all cases without exception think doctors or providers should face a penalty if an abortion were carried out in a situation where it was illegal. This compares with 91% of those who think abortion should be illegal in all cases without exceptions. Still, regardless of how they feel about whether abortion should be legal or not, Americans are more likely to say a doctor or provider should face a penalty compared with others involved in the procedure.

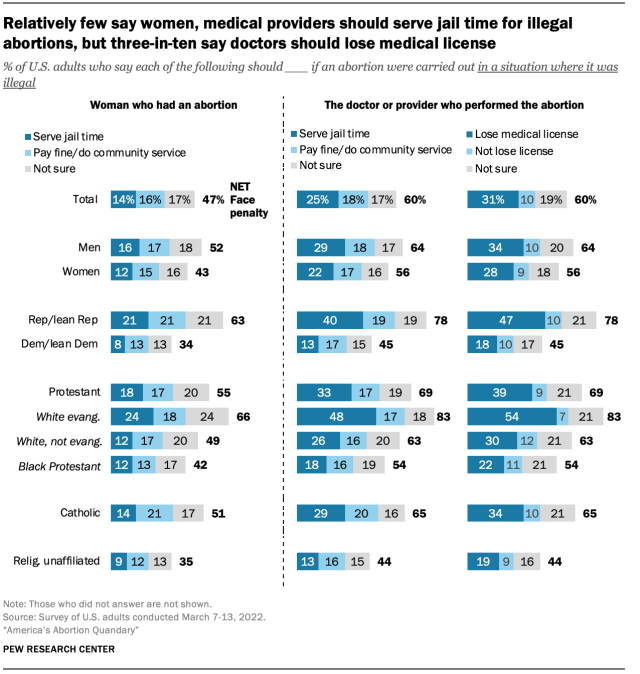

Among those who say medical providers and/or women should face penalties for illegal abortions, there is no consensus about whether they should get jail time or a less severe punishment. Among U.S. adults overall, 14% say women should serve jail time if they have an abortion in a situation where it is illegal, while 16% say they should receive a fine or community service and 17% say they are not sure what the penalty should be.

A somewhat larger share of Americans (25%) say doctors or other medical providers should face jail time for providing illegal abortion services, while 18% say they should face fines or community service and 17% are not sure. About three-in-ten U.S. adults (31%) say doctors should lose their medical license if they perform an abortion in a situation where it is illegal.

Men are more likely than women to favor penalties for the woman or doctor in situations where abortion is illegal. About half of men (52%) say women should face a penalty, while just 43% of women say the same. Similarly, about two-thirds of men (64%) say a doctor should face a penalty, while 56% of women agree.

Republicans are considerably more likely than Democrats to say both women and doctors should face penalties – including jail time. For example, 21% of Republicans say the woman who had the abortion should face jail time, and 40% say this about the doctor who performed the abortion. Among Democrats, far smaller shares say the woman (8%) or doctor (13%) should serve jail time.

White evangelical Protestants are more likely than other Protestant groups to favor penalties for abortions in situations where they are illegal. Fully 24% say the woman who had the abortion should serve time in jail, compared with just 12% of White non-evangelical Protestants or Black Protestants. And while about half of White evangelicals (48%) say doctors who perform illegal abortions should serve jail time, just 26% of White non-evangelical Protestants and 18% of Black Protestants share this view.

- Only respondents who said that abortion should be legal in some cases but not others and that how long a woman has been pregnant should matter in determining whether abortion should be legal received questions about abortion’s legality at specific points in the pregnancy. ↩

Sign up for our Religion newsletter

Sent weekly on Wednesday

Report Materials

Table of contents, majority of public disapproves of supreme court’s decision to overturn roe v. wade, wide partisan gaps in abortion attitudes, but opinions in both parties are complicated, key facts about the abortion debate in america, about six-in-ten americans say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, fact sheet: public opinion on abortion, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

We Asked Hundreds of Americans About Abortion. Their Feelings Were Complicated

H eadlines broadcasting the pending Supreme Court ruling on abortion commonly pit one “side” against another. “Pro-life” versus “pro-choice.” Abortion rights or abortion opposition. “Healthcare” or “Murder.” It’s seems there’s little room for ambivalence when the stakes are so high and rallying cry so deafening.

But most ordinary Americans’ views on abortion are messy. Complicated. Contradictory, even. Not so easily categorized as “for” or “against.” This messiness means that the political and social implications of overturning Roe—which looks likely in the wake of a leak from the Court—remain unclear.

As a sociologist and lead researcher on the National Abortion Attitudes Study , my team and I interviewed hundreds of Americans in 2019 to better understand what’s behind contemporary abortion thinking in the U.S. We were motivated by the puzzle that confounds statistical summaries of abortion opinion— namely, that so many Americans describe themselves as neither entirely for nor entirely against abortion. Most support it in some cases, but not all . On questions of morality, more Americans say “it depends” than say “morally opposed” or “not morally opposed.”

Surveys can’t tell us much about that kind of equivocation, which is why we turned instead to confidential, 75-minute, face-to-face interviews. We invited a randomly selected, closely representative set of Americans to tell us in their own words how they felt.

Lucinda, a pseudonym for a 28-year-old Black Christian woman living in the South, paused in contemplation before answering a question we asked her about the morality of abortion. “Mostly, I’m opposed to it. But it also kind of depends. I’m here and there with it.” She explained that, for her, the issue hinges on responsibility. “Have fun,” but “at least use protection or take precautionary measures. Don’t just be out there willy-nilly.” And if someone gets pregnant, well, “that life was meant to be.” Lucinda cringes at the idea of people “just in and out of the abortion clinic.” “I think they should be more responsible. Don’t be such a loosey-goosey.”

But Lucinda—who tells us that she’d answer “legal in certain circumstances” to a survey question on abortion—also shared that she “understands” how someone might take every precaution and still wind up pregnant. Empathy motivates her support for legal abortion if a woman cannot afford any more children. Or does not want to marry the man involved in the pregnancy. Or is married but does not want more children.

“It sucks. But it’s also understandable.”

She doesn’t approve of abortion for “any reason,” either, because people “should have been a little more careful.” Her support wanes as a pregnancy develops. First trimester “is, like, okay.” Second trimester “is really pushing it.” And the third trimester? “That’s just a complete ‘No,’ like, it’s too late for you to do that. I understand you are upset, but it’s a formed life.” “I’m pro-life,” Lucinda says, “but I do still believe people should be able to have a choice.”

Read More: The End of Roe Could Galvanize Democrats’ Base

Brad (a 49-year-old white father of two) told us that he wishes to see abortion outlawed apart from situations of rape (“if you can prove it”) or health endangerment (“if the woman’s gonna die”). But he also shared his uncertainty about holding to his convictions “if my 16-year-old daughter comes to me and says, ‘I’m pregnant and I want to have an abortion’… I don’t know what I would do…I cannot say 100% that I would say ‘No, you’ve got to have this baby.’”

We also met 56-year-old Greg, a white nonreligious Democrat in the Mountain West, who supports abortion only as “a last resort” – “it’s certainly not the preferred method of birth control.” And Lauren, 24, white, and unmarried, who wishes someone considering an abortion would “think about it a bit more,” pondering for herself whether “it’s better to just have an abortion than have that child be raised in a really bad environment.” But she also votes to restrict abortion in nearly all circumstances.

Lucinda, Brad, Greg, and Lauren are hardly alone in their foggy mix of views on abortion, blurring lines between support and opposition, moral views and legal ones, what could happen and what should happen. A new study on U.S. abortion attitudes from the Pew Research Center echoes what we heard among our interviewees, revealing large shares of Americans opposed to abortion who nonetheless support legality, Americans whose opinions differ by pregnancy timing and circumstance, and a complex picture of abortion thinking overall.

Messiness abounds in Americans’ attitudes on an issue misleadingly portrayed as mutually exclusive.

Our interviewees avidly against abortion simultaneously shared stories about driving a friend to get an abortion , terminating a pregnancy themselves, or walking with women through crowds of protesters to access a clinic. Americans who support the legal right to abortion spoke also about the irrefutable notion of “babies” in the womb, including their own; of being unable to fathom having an abortion themselves; and of deep discomfort with abortions that occur “too late” in a pregnancy or for “bad” reasons like sex selection or as a substitute for contraception.

The legal lexicon surrounding abortion does not leave much room for the kind of moral grappling Americans do when they think through the issue. Our interviewees vacillated confusingly between what was “a right” and what was “right.” To a series of questions on legality, many would offer answers as to what a woman “should” or “shouldn’t” do in the given situation, fusing their moral and legal appraisals. Some told us that they felt one way but would respond to a survey (or vote) another.

Of course, abortion for ordinary Americans isn’t deliberated in a courthouse. It’s deliberated personally and interpersonally. A quarter of our female interviewees— like a quarter of U.S. women overall— had an abortion themselves. Another three-quarters knew someone personally who had experienced an abortion, whether a friend, family member, or otherwise. Abortion talk raises countless personal stories about pregnancy, miscarriage, infertility, the high cost of childcare, failed relationships, abuse, absent parenthood, and much more.

The political gets muddy precisely because it’s so personal. Americans’ convictions on abortion, we learned, encounter inconvenient exceptions and questions with neither clear answers nor venues to sort through them.

Attitudinal complexity leaves many Americans feeling sidelined and displaced for their abortion views: ill-fitting in the Democrat and Republican parties, imperfectly aligned within religious traditions, unwilling to join activist movements that don’t readily invite equivocation or gradation. Many choose instead to stay quiet. Many feel like they are the only ones whose views look like this.

But they aren’t. They’re in company with a wide array of Americans who don’t quite know what to do about abortion. It’s a hard issue, both politically and personally.

Which brings us back to the unpredictability of what happens after the Supreme Court’s impending decision. There’s a chance that the ruling will lay bare the brokenness to how we (don’t) talk about abortion. Maybe it’s also an invitation for a new lexicon, greater empathy, reduced stigma, bolstered support, and a more honest deliberation regarding pregnancy, families, and inequality in the U.S. today. And while it’s hard to predict what comes next, what’s clear is that we’re living a historical moment where we need to engage the conversation.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Passengers Are Flying up to 30 Hours to See Four Minutes of the Eclipse

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Essay: The Complicated Dread of Early Spring

- Why Walking Isn’t Enough When It Comes to Exercise

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

Key Arguments From Both Sides of the Abortion Debate

Mark Wilson / Staff / Getty Images

- Reproductive Rights

- The U. S. Government

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

- B.A., English Language and Literature, Well College

Many points come up in the abortion debate . Here's a look at abortion from both sides : 10 arguments for abortion and 10 arguments against abortion, for a total of 20 statements that represent a range of topics as seen from both sides.

Pro-Life Arguments

- Since life begins at conception, abortion is akin to murder as it is the act of taking human life. Abortion is in direct defiance of the commonly accepted idea of the sanctity of human life.

- No civilized society permits one human to intentionally harm or take the life of another human without punishment, and abortion is no different.

- Adoption is a viable alternative to abortion and accomplishes the same result. And with 1.5 million American families wanting to adopt a child, there is no such thing as an unwanted child.

- An abortion can result in medical complications later in life; the risk of ectopic pregnancies is increased if other factors such as smoking are present, the chance of a miscarriage increases in some cases, and pelvic inflammatory disease also increases.

- In the instance of rape and incest, taking certain drugs soon after the event can ensure that a woman will not get pregnant. Abortion punishes the unborn child who committed no crime; instead, it is the perpetrator who should be punished.

- Abortion should not be used as another form of contraception.

- For women who demand complete control of their body, control should include preventing the risk of unwanted pregnancy through the responsible use of contraception or, if that is not possible, through abstinence .

- Many Americans who pay taxes are opposed to abortion, therefore it's morally wrong to use tax dollars to fund abortion.

- Those who choose abortions are often minors or young women with insufficient life experience to understand fully what they are doing. Many have lifelong regrets afterward.

- Abortion sometimes causes psychological pain and stress.

Pro-Choice Arguments

- Nearly all abortions take place in the first trimester when a fetus is attached by the placenta and umbilical cord to the mother. As such, its health is dependent on her health, and cannot be regarded as a separate entity as it cannot exist outside her womb.

- The concept of personhood is different from the concept of human life. Human life occurs at conception, but fertilized eggs used for in vitro fertilization are also human lives and those not implanted are routinely thrown away. Is this murder, and if not, then how is abortion murder?

- Adoption is not an alternative to abortion because it remains the woman's choice whether or not to give her child up for adoption. Statistics show that very few women who give birth choose to give up their babies; less than 3% of White unmarried women and less than 2% of Black unmarried women.

- Abortion is a safe medical procedure. The vast majority of women who have an abortion do so in their first trimester. Medical abortions have a very low risk of serious complications and do not affect a woman's health or future ability to become pregnant or give birth.

- In the case of rape or incest, forcing a woman made pregnant by this violent act would cause further psychological harm to the victim. Often a woman is too afraid to speak up or is unaware she is pregnant, thus the morning after pill is ineffective in these situations.

- Abortion is not used as a form of contraception . Pregnancy can occur even with contraceptive use. Few women who have abortions do not use any form of birth control, and that is due more to individual carelessness than to the availability of abortion.

- The ability of a woman to have control of her body is critical to civil rights. Take away her reproductive choice and you step onto a slippery slope. If the government can force a woman to continue a pregnancy, what about forcing a woman to use contraception or undergo sterilization?

- Taxpayer dollars are used to enable poor women to access the same medical services as rich women, and abortion is one of these services. Funding abortion is no different from funding a war in the Mideast. For those who are opposed, the place to express outrage is in the voting booth.

- Teenagers who become mothers have grim prospects for the future. They are much more likely to leave school; receive inadequate prenatal care; or develop mental health problems.

- Like any other difficult situation, abortion creates stress. Yet the American Psychological Association found that stress was greatest prior to an abortion and that there was no evidence of post-abortion syndrome.

Additional References

- Alvarez, R. Michael, and John Brehm. " American Ambivalence Towards Abortion Policy: Development of a Heteroskedastic Probit Model of Competing Values ." American Journal of Political Science 39.4 (1995): 1055–82. Print.

- Armitage, Hannah. " Political Language, Uses and Abuses: How the Term 'Partial Birth' Changed the Abortion Debate in the United States ." Australasian Journal of American Studies 29.1 (2010): 15–35. Print.

- Gillette, Meg. " Modern American Abortion Narratives and the Century of Silence ." Twentieth Century Literature 58.4 (2012): 663–87. Print.

- Kumar, Anuradha. " Disgust, Stigma, and the Politics of Abortion ." Feminism & Psychology 28.4 (2018): 530–38. Print.

- Ziegler, Mary. " The Framing of a Right to Choose: Roe V. Wade and the Changing Debate on Abortion Law ." Law and History Review 27.2 (2009): 281–330. Print.

“ Life Begins at Fertilization with the Embryo's Conception .” Princeton University , The Trustees of Princeton University.

“ Long-Term Risks of Surgical Abortion .” GLOWM, doi:10.3843/GLOWM.10441

Patel, Sangita V, et al. “ Association between Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and Abortions .” Indian Journal of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and AIDS , Medknow Publications, July 2010, doi:10.4103/2589-0557.75030

Raviele, Kathleen Mary. “ Levonorgestrel in Cases of Rape: How Does It Work? ” The Linacre Quarterly , Maney Publishing, May 2014, doi:10.1179/2050854914Y.0000000017

Reardon, David C. “ The Abortion and Mental Health Controversy: A Comprehensive Literature Review of Common Ground Agreements, Disagreements, Actionable Recommendations, and Research Opportunities .” SAGE Open Medicine , SAGE Publications, 29 Oct. 2018, doi:10.1177/2050312118807624

“ CDCs Abortion Surveillance System FAQs .” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 25 Nov. 2019.

Bixby Center for Reproductive Health. “ Complications of Surgical Abortion : Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology .” LWW , doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181a2b756

" Sexual Violence: Prevalence, Dynamics and Consequences ." World Health Organizaion.

Homco, Juell B, et al. “ Reasons for Ineffective Pre-Pregnancy Contraception Use in Patients Seeking Abortion Services .” Contraception , U.S. National Library of Medicine, Dec. 2009, doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2009.05.127

" Working With Pregnant & Parenting Teens Tip Sheet ." U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Major, Brenda, et al. " Abortion and Mental Health: Evaluating the Evidence ." American Psychological Association, doi:10.1037/a0017497

- The Roe v. Wade Supreme Court Decision

- Roe v. Wade

- 1970s Feminism Timeline

- Analysis of 'Hills Like White Elephants' by Ernest Hemingway

- Quotes from Contraceptives Pioneer Margaret Sanger

- Female Infanticide in Asia

- The Pro-Life vs Pro-Choice Debate

- Abortion on Demand: A Second Wave Feminist Demand

- Pros & Cons of Embryonic Stem Cell Research

- Abortion Facts and Statistics in the 21st Century

- The 1969 Redstockings Abortion Speakout

- 3 Major Ways Enslaved People Showed Resistance to a Life in Bondage

- Feminist Organizations of the 1970s

- Biography of Margaret Sanger

- Population Decline in Russia

- Is Abortion Legal in Every State?

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.1: Arguments Against Abortion

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 35918

- Nathan Nobis & Kristina Grob

- Morehouse College & University of South Carolina Sumter via Open Philosophy Press

We will begin with arguments for the conclusion that abortion is generally wrong , perhaps nearly always wrong . These can be seen as reasons to believe fetuses have the “right to life” or are otherwise seriously wrong to kill.

5.1.1 Fetuses are human

First, there is the claim that fetuses are “human” and so abortion is wrong. People sometimes debate whether fetuses are human , but fetuses found in (human) women clearly are biologically human : they aren’t cats or dogs. And so we have this argument, with a clearly true first premise:

Fetuses are biologically human.

All things that are biologically human are wrong to kill.

Therefore, fetuses are wrong to kill.

The second premise, however, is false, as easy counterexamples show. Consider some random living biologically human cells or tissues in a petri dish. It wouldn’t be wrong at all to wash those cells or tissues down the drain, killing them; scratching yourself or shaving might kill some biologically human skin cells, but that’s not wrong; a tumor might be biologically human, but not wrong to kill. So just because something is biologically human, that does not at all mean it’s wrong to kill that thing. We saw this same point about what’s merely biologically alive.

This suggests a deficiency in some common understandings of the important idea of “human rights.” “Human rights” are sometimes described as rights someone has just because they are human or simply in virtue of being human .

But the human cells in the petri dish above don’t have “human rights” and a human heart wouldn’t have “human rights” either. Many examples would make it clear that merely being biologically human doesn’t give something human rights. And many human rights advocates do not think that abortion is wrong, despite recognizing that (human) fetuses are biologically human.

The problem about what is often said about human rights is that people often do not think about what makes human beings have rights or why we have them, when we have them. The common explanation, that we have (human) rights just because we are (biologically) human , is incorrect, as the above discussion makes clear. This misunderstanding of the basis or foundation of human rights is problematic because it leads to a widespread, misplaced fixation on whether fetuses are merely biologically “human” and the mistaken thought that if they are, they have “human rights.” To address this problem, we need to identify better, more fundamental, explanations why we have rights, or why killing us is generally wrong, and see how those explanations might apply to fetuses, as we are doing here.

It might be that when people appeal to the importance and value of being “human,” the concern isn’t our biology itself, but the psychological characteristics that many human beings have: consciousness, awareness, feelings and so on. We will discuss this different meaning of “human” below. This meaning of “human” might be better expressed as conscious being , or “person,” or human person. This might be what people have in mind when they argue that fetuses aren’t even “human.”

Human rights are vitally important, and we would do better if we spoke in terms of “conscious-being rights” or “person-rights,” not “human rights.” This more accurate and informed understanding and terminology would help address human rights issues in general, and help us better think through ethical questions about biologically human embryos and fetuses.

5.1.2 Fetuses are human beings

Some respond to the arguments above—against the significance of being merely biologically human—by observing that fetuses aren’t just mere human cells, but are organized in ways that make them beings or organisms . (A kidney is part of a “being,” but the “being” is the whole organism.) That suggests this argument:

Fetuses are human beings or organisms .

All human beings or organisms are wrong to kill.

Therefore, fetuses are wrong to kill, so abortion is wrong.

The first premise is true: fetuses are dependent beings, but dependent beings are still beings.

The second premise, however, is the challenge, in terms of providing good reasons to accept it. Clearly many human beings or organisms are wrong to kill, or wrong to kill unless there’s a good reason that would justify that killing, e.g., self-defense. (This is often described by philosophers as us being prima facie wrong to kill, in contrast to absolutely or necessarily wrong to kill.) Why is this though? What makes us wrong to kill? And do these answers suggest that all human beings or organisms are wrong to kill?

Above it was argued that we are wrong to kill because we are conscious and feeling: we are aware of the world, have feelings and our perspectives can go better or worse for us —we can be harmed— and that’s what makes killing us wrong. It may also sometimes be not wrong to let us die, and perhaps even kill us, if we come to completely and permanently lacking consciousness, say from major brain damage or a coma, since we can’t be harmed by death anymore: we might even be described as dead in the sense of being “brain dead.” 10

So, on this explanation, human beings are wrong to kill, when they are wrong to kill, not because they are human beings (a circular explanation), but because we have psychological, mental or emotional characteristics like these. This explains why we have rights in a simple, common-sense way: it also simply explains why rocks, microorganisms and plants don’t have rights. The challenge then is explaining why fetuses that have never been conscious or had any feeling or awareness would be wrong to kill. How then can the second premise above, general to all human organisms, be supported, especially when applied to early fetuses?

One common attempt is to argue that early fetuses are wrong to kill because there is continuous development from fetuses to us, and since we are wrong to kill now , fetuses are also wrong to kill, since we’ve been the “same being” all along. 11 But this can’t be good reasoning, since we have many physical, cognitive, emotional and moral characteristics now that we lacked as fetuses (and as children). So even if we are the “same being” over time, even if we were once early fetuses, that doesn’t show that fetuses have the moral rights that babies, children and adults have: we, our bodies and our rights sometimes change.

A second attempt proposes that rights are essential to human organisms: they have them whenever they exist. This perspective sees having rights, or the characteristics that make someone have rights, as essential to living human organisms. The claim is that “having rights” is an essential property of human beings or organisms, and so whenever there’s a living human organism, there’s someone with rights, even if that organism totally lacks consciousness, like an early fetus. (In contrast, the proposal we advocate for about what makes us have rights understands rights as “accidental” to our bodies but “essential” to our minds or awareness, since our bodies haven’t always “contained” a conscious being, so to speak.)

Such a view supports the premise above; maybe it just is that premise above. But why believe that rights are essential to human organisms? Some argue this is because of what “kind” of beings we are, which is often presumed to be “rational beings.” The reasoning seems to be this: first, that rights come from being a rational being: this is part of our “nature.” Second, that all human organisms, including fetuses, are the “kind” of being that is a “rational being,” so every being of the “kind” rational being has rights. 12

In response, this explanation might seem question-begging: it might amount to just asserting that all human beings have rights. This explanation is, at least, abstract. It seems to involve some categorization and a claim that everyone who is in a certain category has some of the same moral characteristics that others in that category have, but because of a characteristic (actual rationality) that only these others have: so, these others profoundly define what everyone else is . If this makes sense, why not also categorize us all as not rational beings , if we are the same kind of beings as fetuses that are actually not rational?

This explanation might seem to involve thinking that rights somehow “trickle down” from later rationality to our embryonic origins, and so what we have later we also have earlier , because we are the same being or the same “kind” of being. But this idea is, in general, doubtful: we are now responsible beings, in part because we are rational beings, but fetuses aren’t responsible for anything. And we are now able to engage in moral reasoning since we are rational beings, but fetuses don’t have the “rights” that uniquely depend on moral reasoning abilities. So that an individual is a member of some general group or kind doesn’t tell us much about their rights: that depends on the actual details about that individual, beyond their being members of a group or kind.

To make this more concrete, return to the permanently comatose individuals mentioned above: are we the same kind of beings, of the same “essence,” as these human beings? If so, then it seems that some human beings can be not wrong to let die or kill, when they have lost consciousness. Therefore, perhaps some other human beings, like early fetuses, are also not wrong to kill before they have gained consciousness . And if we are not the same “kind” of beings, or have different essences, then perhaps we also aren’t the same kind of beings as fetuses either.

Similar questions arise concerning anencephalic babies, tragically born without most of their brains: are they the same “kind” of beings as “regular” babies or us? If so, then—since such babies are arguably morally permissible to let die, even when they could be kept alive, since being alive does them no good—then being of our “kind” doesn’t mean the individual has the same rights as us, since letting us die would be wrong. But if such babies are a different “kind” of beings than us, then pre-conscious fetuses might be of a relevantly different kind also.

So, in general, this proposal that early fetuses essentially have rights is suspect, if we evaluate the reasons given in its support. Even if fetuses and us are the same “kind” of beings (which perhaps we are not!) that doesn’t immediately tell us what rights fetuses would have, if any. And we might even reasonably think that, despite our being the same kind of beings as fetuses (e.g., the same kind of biology), we are also importantly different kinds of beings (e.g., one kind with a mental life and another kind which has never had it). This photograph of a 6-week old fetus might help bring out the ambiguity in what kinds of beings we all are:

In sum, the abstract view that all human organisms have rights essentially needs to be plausibly explained and defended. We need to understand how it really works. We need to be shown why it’s a better explanation, all things considered, than a consciousness and feelings-based theory of rights that simply explains why we, and babies, have rights, why racism, sexism and other forms of clearly wrongful discrimination are wrong, and , importantly, how we might lose rights in irreversible coma cases (if people always retained the right to life in these circumstances, presumably, it would be wrong to let anyone die), and more.

5.1.3 Fetuses are persons

Finally, we get to what some see as the core issue here, namely whether fetuses are persons , and an argument like this:

Fetuses are persons, perhaps from conception.

Persons have the right to life and are wrong to kill.

So, abortion is wrong, as it involves killing persons.

The second premise seems very plausible, but there are some important complications about it that will be discussed later. So let’s focus on the idea of personhood and whether any fetuses are persons. What is it to be a person ? One answer that everyone can agree on is that persons are beings with rights and value . That’s a fine answer, but it takes us back to the initial question: OK, who or what has the rights and value of persons? What makes someone or something a person?

Answers here are often merely asserted , but these answers need to be tested: definitions can be judged in terms of whether they fit how a word is used. We might begin by thinking about what makes us persons. Consider this:

We are persons now. Either we will always be persons or we will cease being persons. If we will cease to be persons, what can end our personhood? If we will always be persons, how could that be?

Both options yield insight into personhood. Many people think that their personhood ends at death or if they were to go into a permanent coma: their body is (biologically) alive but the person is gone: that is why other people are sad. And if we continue to exist after the death of our bodies, as some religions maintain, what continues to exist? The person , perhaps even without a body, some think! Both responses suggest that personhood is defined by a rough and vague set of psychological or mental, rational and emotional characteristics: consciousness, knowledge, memories, and ways of communicating, all psychologically unified by a unique personality.

A second activity supports this understanding:

Make a list of things that are definitely not persons . Make a list of individuals who definitely are persons . Make a list of imaginary or fictional personified beings which, if existed, would be persons: these beings that fit or display the concept of person, even if they don’t exist. What explains the patterns of the lists?

Rocks, carrots, cups and dead gnats are clearly not persons. We are persons. Science fiction gives us ideas of personified beings: to give something the traits of a person is to indicate what the traits of persons are, so personified beings give insights into what it is to be a person. Even though the non-human characters from, say, Star Wars don’t exist, they fit the concept of person: we could befriend them, work with them, and so on, and we could only do that with persons. A common idea of God is that of an immaterial person who has exceptional power, knowledge, and goodness: you couldn’t pray to a rock and hope that rock would respond: you could only pray to a person. Are conscious and feeling animals, like chimpanzees, dolphins, cats, dogs, chickens, pigs, and cows more relevantly like us, as persons, or are they more like rocks and cabbages, non-persons? Conscious and feeling animals seem to be closer to persons than not. 13 So, this classificatory and explanatory activity further supports a psychological understanding of personhood: persons are, at root, conscious, aware and feeling beings.

Concerning abortion, early fetuses would not be persons on this account: they are not yet conscious or aware since their brains and nervous systems are either non-existent or insufficiently developed. Consciousness emerges in fetuses much later in pregnancy, likely after the first trimester or a bit beyond. This is after when most abortions occur. Most abortions, then, do not involve killing a person , since the fetus has not developed the characteristics for personhood. We will briefly discuss later abortions, that potentially affect fetuses who are persons or close to it, below.

It is perhaps worthwhile to notice though that if someone believed that fetuses are persons and thought this makes abortion wrong, it’s unclear how they could coherently believe that a pregnancy resulting from rape or incest could permissibly be ended by an abortion. Some who oppose abortion argue that, since you are a person, it would be wrong to kill you now even if you were conceived because of a rape, and so it’s wrong to kill any fetus who is a person, even if they exist because of a rape: whether someone is a person or not doesn’t depend on their origins: it would make no sense to think that, for two otherwise identical fetuses, one is a person but the other isn’t, because that one was conceived by rape. Therefore, those who accept a “personhood argument” against abortion, yet think that abortions in cases of rape are acceptable, seem to have an inconsistent view.

5.1.4 Fetuses are potential persons

If fetuses aren’t persons, they are at least potential persons, meaning they could and would become persons. This is true. This, however, doesn’t mean that they currently have the rights of persons because, in general, potential things of a kind don’t have the rights of actual things of that kind : potential doctors, lawyers, judges, presidents, voters, veterans, adults, parents, spouses, graduates, moral reasoners and more don’t have the rights of actual individuals of those kinds.

Some respond that potential gives the right to at least try to become something. But that trying sometimes involves the cooperation of others: if your friend is a potential medical student, but only if you tutor her for many hours a day, are you obligated to tutor her? If my child is a potential NASCAR champion, am I obligated to buy her a race car to practice? ‘No’ to both and so it is unclear that a pregnant woman would be obligated to provide what’s necessary to bring about a fetus’s potential. (More on that below, concerning the what obligations the right to life imposes on others, in terms of obligations to assist other people.)

5.1.5 Abortion prevents fetuses from experiencing their valuable futures

The argument against abortion that is likely most-discussed by philosophers comes from philosopher Don Marquis. 14 He argues that it is wrong to kill us, typical adults and children, because it deprives us from experiencing our (expected to be) valuable futures, which is a great loss to us . He argues that since fetuses also have valuable futures (“futures like ours” he calls them), they are also wrong to kill. His argument has much to recommend it, but there are reasons to doubt it as well.

First, fetuses don’t seem to have futures like our futures , since—as they are pre-conscious—they are entirely psychologically disconnected from any future experiences: there is no (even broken) chain of experiences from the fetus to that future person’s experiences. Babies are, at least, aware of the current moment, which leads to the next moment; children and adults think about and plan for their futures, but fetuses cannot do these things, being completely unconscious and without a mind.

Second, this fact might even mean that the early fetus doesn’t literally have a future: if your future couldn’t include you being a merely physical, non-conscious object (e.g., you couldn’t be a corpse: if there’s a corpse, you are gone), then non-conscious physical objects, like a fetus, couldn’t literally be a future person. 15 If this is correct, early fetuses don’t even have futures, much less futures like ours. Something would have a future, like ours, only when there is someone there to be psychologically connected to that future: that someone arrives later in pregnancy, after when most abortions occur.

A third objection is more abstract and depends on the “metaphysics” of objects. It begins with the observation that there are single objects with parts with space between them . Indeed almost every object is like this, if you could look close enough: it’s not just single dinette sets, since there is literally some space between the parts of most physical objects. From this, it follows that there seem to be single objects such as an-egg-and-the-sperm-that-would-fertilize-it . And these would also seem to have a future of value, given how Marquis describes this concept. (It should be made clear that sperm and eggs alone do not have futures of value, and Marquis does not claim they do: this is not the objection here). The problem is that contraception, even by abstinence , prevents that thing’s future of value from materializing, and so seems to be wrong when we use Marquis’s reasoning. Since contraception is not wrong, but his general premise suggests that it is , it seems that preventing something from experiencing its valuable future isn’t always wrong and so Marquis’s argument appears to be unsound. 16

In sum, these are some of the most influential arguments against abortion. Our discussion was brief, but these arguments do not appear to be successful: they do not show that abortion is wrong, much less make it clear and obvious that abortion is wrong.

Ethics and Morality

Ethics and abortion, two opposing arguments on the morality of abortion..

Posted June 7, 2019 | Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Abortion is, once again, center stage in our political debates. According to the Guttmacher Institute, over 350 pieces of legislation restricting abortion have been introduced. Ten states have signed bans of some sort, but these are all being challenged. None of these, including "heartbeat" laws, are currently in effect. 1

Much has been written about abortion from a philosophical perspective. Here, I'd like to summarize what I believe to be the best argument on each side of the abortion debate. To be clear, I'm not advocating either position here; I'm simply trying to bring some clarity to the issues. The focus of these arguments is on the morality of abortion, not its constitutional or legal status. This is important. One might believe, as many do, that at least some abortions are immoral but that the law should not restrict choice in this realm of life. Others, of course, argue that abortion is immoral and should be illegal in most or all cases.

"Personhood"

Personhood refers to the moral status of an entity. If an entity is a person , in this particular sense, it has full moral status . A person, then, has rights , and we have obligations to that person. This includes the right to life. Both of the arguments I summarize here focus on the question of whether or not the fetus is a person, or whether or not it is the type of entity that has the right to life. This is an important aspect to focus on, because what a thing is determines how we should treat it, morally speaking. For example, if I break a leg off of a table, I haven't done anything wrong. But if I break a puppy's leg, I surely have done something wrong. I have obligations to the puppy, given what kind of creature it is, that I don't have to a table, or any other inanimate object. The issue, then, is what kind of thing a fetus is, and what that entails for how we ought to treat it.

A Pro-Choice Argument

I believe that the best type of pro-choice argument focuses on the personhood of the fetus. Mary Ann Warren has argued that fetuses are not persons; they do not have the right to life. 2 Therefore, abortion is morally permissible throughout the entire pregnancy . To see why, Warren argues that persons have the following traits:

- Consciousness: awareness of oneself, the external world, the ability to feel pain.

- Reasoning: a developed ability to solve fairly complex problems.

- Ability to communicate: on a variety of topics, with some depth.

- Self-motivated activity: ability to choose what to do (or not to do) in a way that is not determined by genetics or the environment .

- Self-concept : see themselves as _____; e.g. Kenyan, female, athlete , Muslim, Christian, atheist, etc.

The key point for Warren is that fetuses do not have any of these traits. Therefore, they are not persons. They do not have a right to life, and abortion is morally permissible. You and I do have these traits, therefore we are persons. We do have rights, including the right to life.

One problem with this argument is that we now know that fetuses are conscious at roughly the midpoint of a pregnancy, given the development timeline of fetal brain activity. Given this, some have modified Warren's argument so that it only applies to the first half of a pregnancy. This still covers the vast majority of abortions that occur in the United States, however.

A Pro-Life Argument

The following pro-life argument shares the same approach, focusing on the personhood of the fetus. However, this argument contends that fetuses are persons because in an important sense they possess all of the traits Warren lists. 3

At first glance, this sounds ridiculous. At 12 weeks, for example, fetuses are not able to engage in reasoning, they don't have a self-concept, nor are they conscious. In fact, they don't possess any of these traits.

Or do they?

In one sense, they do. To see how, consider an important distinction, the distinction between latent capacities vs. actualized capacities. Right now, I have the actualized capacity to communicate in English about the ethics of abortion. I'm demonstrating that capacity right now. I do not, however, have the actualized capacity to communicate in Spanish on this issue. I do, however, have the latent capacity to do so. If I studied Spanish, practiced it with others, or even lived in a Spanish-speaking nation for a while, I would likely be able to do so. The latent capacity I have now to communicate in Spanish would become actualized.

Here is the key point for this argument: Given the type of entities that human fetuses are, they have all of the traits of persons laid out by Mary Anne Warren. They do not possess these traits in their actualized form. But they have them in their latent form, because of their human nature. Proponents of this argument claim that possessing the traits of personhood, in their latent form, is sufficient for being a person, for having full moral status, including the right to life. They say that fetuses are not potential persons, but persons with potential. In contrast to this, Warren and others maintain that the capacities must be actualized before one is person.

The Abortion Debate

There is much confusion in the abortion debate. The existence of a heartbeat is not enough, on its own, to confer a right to life. On this, I believe many pro-lifers are mistaken. But on the pro-choice side, is it ethical to abort fetuses as a way to select the gender of one's child, for instance?

We should not focus solely on the fetus, of course, but also on the interests of the mother, father, and society as a whole. Many believe that in order to achieve this goal, we need to provide much greater support to women who may want to give birth and raise their children, but choose not to for financial, psychological, health, or relationship reasons; that adoption should be much less expensive, so that it is a live option for more qualified parents; and that quality health care should be accessible to all.

I fear , however, that one thing that gets lost in all of the dialogue, debate, and rhetoric surrounding the abortion issue is the nature of the human fetus. This is certainly not the only issue. But it is crucial to determining the morality of abortion, one way or the other. People on both sides of the debate would do well to build their views with this in mind.

https://abcnews.go.com/US/state-abortion-bans-2019-signed-effect/story?id=63172532

Mary Ann Warren, "On the Moral and Legal Status of Abortion," originally in Monist 57:1 (1973), pp. 43-61. Widely anthologized.

This is a synthesis of several pro-life arguments. For more, see the work of Robert George and Francis Beckwith on these issues.

Michael W. Austin, Ph.D. , is a professor of philosophy at Eastern Kentucky University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Persuasive Essay Guide

Persuasive Essay About Abortion

Crafting a Convincing Persuasive Essay About Abortion

-9248.jpg&w=640&q=75)

People also read

A Comprehensive Guide to Writing an Effective Persuasive Essay

200+ Persuasive Essay Topics to Help You Out

Learn How to Create a Persuasive Essay Outline

30+ Free Persuasive Essay Examples To Get You Started

Read Excellent Examples of Persuasive Essay About Gun Control

How to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid19 | Examples & Tips

Learn to Write Persuasive Essay About Business With Examples and Tips

Check Out 12 Persuasive Essay About Online Education Examples

Persuasive Essay About Smoking - Making a Powerful Argument with Examples

Are you about to write a persuasive essay on abortion but wondering how to begin?

Writing an effective persuasive essay on the topic of abortion can be a difficult task for many students.

It is important to understand both sides of the issue and form an argument based on facts and logical reasoning. This requires research and understanding, which takes time and effort.

In this blog, we will provide you with some easy steps to craft a persuasive essay about abortion that is compelling and convincing. Moreover, we have included some example essays and interesting facts to read and get inspired by.

So let's start!

- 1. How To Write a Persuasive Essay About Abortion?

- 2. Persuasive Essay About Abortion Examples

- 3. Examples of Argumentative Essay About Abortion

- 4. Abortion Persuasive Essay Topics

- 5. Facts About Abortion You Need to Know

How To Write a Persuasive Essay About Abortion?

Abortion is a controversial topic, with people having differing points of view and opinions on the matter. There are those who oppose abortion, while some people endorse pro-choice arguments.

It is also an emotionally charged subject, so you need to be extra careful when crafting your persuasive essay .

Before you start writing your persuasive essay, you need to understand the following steps.

Step 1: Choose Your Position

The first step to writing a persuasive essay on abortion is to decide your position. Do you support the practice or are you against it? You need to make sure that you have a clear opinion before you begin writing.

Once you have decided, research and find evidence that supports your position. This will help strengthen your argument.

Check out the video below to get more insights into this topic:

Step 2: Choose Your Audience

The next step is to decide who your audience will be. Will you write for pro-life or pro-choice individuals? Or both?

Knowing who you are writing for will guide your writing and help you include the most relevant facts and information.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Step 3: Define Your Argument

Now that you have chosen your position and audience, it is time to craft your argument.

Start by defining what you believe and why, making sure to use evidence to support your claims. You also need to consider the opposing arguments and come up with counter arguments. This helps make your essay more balanced and convincing.

Step 4: Format Your Essay

Once you have the argument ready, it is time to craft your persuasive essay. Follow a standard format for the essay, with an introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion.

Make sure that each paragraph is organized and flows smoothly. Use clear and concise language, getting straight to the point.

Step 5: Proofread and Edit

The last step in writing your persuasive essay is to make sure that you proofread and edit it carefully. Look for spelling, grammar, punctuation, or factual errors and correct them. This will help make your essay more professional and convincing.

These are the steps you need to follow when writing a persuasive essay on abortion. It is a good idea to read some examples before you start so you can know how they should be written.

Continue reading to find helpful examples.

Persuasive Essay About Abortion Examples

To help you get started, here are some example persuasive essays on abortion that may be useful for your own paper.

Short Persuasive Essay About Abortion

Persuasive Essay About No To Abortion

What Is Abortion? - Essay Example

Persuasive Speech on Abortion

Legal Abortion Persuasive Essay

Persuasive Essay About Abortion in the Philippines

Persuasive Essay about legalizing abortion

You can also read m ore persuasive essay examples to imp rove your persuasive skills.

Examples of Argumentative Essay About Abortion

An argumentative essay is a type of essay that presents both sides of an argument. These essays rely heavily on logic and evidence.

Here are some examples of argumentative essay with introduction, body and conclusion that you can use as a reference in writing your own argumentative essay.

Abortion Persuasive Essay Introduction

Argumentative Essay About Abortion Conclusion

Argumentative Essay About Abortion Pdf

Argumentative Essay About Abortion in the Philippines

Argumentative Essay About Abortion - Introduction

Abortion Persuasive Essay Topics

If you are looking for some topics to write your persuasive essay on abortion, here are some examples:

- Should abortion be legal in the United States?

- Is it ethical to perform abortions, considering its pros and cons?

- What should be done to reduce the number of unwanted pregnancies that lead to abortions?

- Is there a connection between abortion and psychological trauma?

- What are the ethical implications of abortion on demand?

- How has the debate over abortion changed over time?

- Should there be legal restrictions on late-term abortions?

- Does gender play a role in how people view abortion rights?

- Is it possible to reduce poverty and unwanted pregnancies through better sex education?

- How is the anti-abortion point of view affected by religious beliefs and values?

These are just some of the potential topics that you can use for your persuasive essay on abortion. Think carefully about the topic you want to write about and make sure it is something that interests you.

Check out m ore persuasive essay topics that will help you explore other things that you can write about!

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Facts About Abortion You Need to Know

Here are some facts about abortion that will help you formulate better arguments.

- According to the Guttmacher Institute , 1 in 4 pregnancies end in abortion.

- The majority of abortions are performed in the first trimester.

- Abortion is one of the safest medical procedures, with less than a 0.5% risk of major complications.

- In the United States, 14 states have laws that restrict or ban most forms of abortion after 20 weeks gestation.

- Seven out of 198 nations allow elective abortions after 20 weeks of pregnancy.

- In places where abortion is illegal, more women die during childbirth and due to complications resulting from pregnancy.

- A majority of pregnant women who opt for abortions do so for financial and social reasons.

- According to estimates, 56 million abortions occur annually.

In conclusion, these are some of the examples, steps, and topics that you can use to write a persuasive essay. Make sure to do your research thoroughly and back up your arguments with evidence. This will make your essay more professional and convincing.

Need the services of a professional essay writing service ? We've got your back!

MyPerfectWords.com is a persuasive essay writing service that provides help to students in the form of professionally written essays. Our persuasive essay writer can craft quality persuasive essays on any topic, including abortion.

Frequently Asked Questions

What should i talk about in an essay about abortion.

When writing an essay about abortion, it is important to cover all the aspects of the subject. This includes discussing both sides of the argument, providing facts and evidence to support your claims, and exploring potential solutions.

What is a good argument for abortion?

A good argument for abortion could be that it is a woman’s choice to choose whether or not to have an abortion. It is also important to consider the potential risks of carrying a pregnancy to term.

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Caleb S. has been providing writing services for over five years and has a Masters degree from Oxford University. He is an expert in his craft and takes great pride in helping students achieve their academic goals. Caleb is a dedicated professional who always puts his clients first.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Introduction: The Politics of Abortion 50 Years after Roe

Katrina Kimport is a professor with the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences and a medical sociologist with the ANSIRH program at the University of California, San Francisco. Her research examines the (re)production of inequality in health and reproduction, with a topical focus on abortion, contraception, and pregnancy. She is the author of No Real Choice: How Culture and Politics Matter for Reproductive Autonomy (2022) and Queering Marriage: Challenging Family Formation in the United States (2014) and co-author, with Jennifer Earl, of Digitally Enabled Social Change (2011). She has published more than 75 articles in sociology, health research, and interdisciplinary journals.

Rebecca Kreitzer is an associate professor of public policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research focuses on gendered political representation and intersectional policy inequality in the US states. Much of her research focuses on the political dynamics of reproductive health care, especially surrounding contraception and abortion. She has published dozens of articles in political science, public policy, and law journals.

- Standard View

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Katrina Kimport , Rebecca Kreitzer; Introduction: The Politics of Abortion 50 Years after Roe . J Health Polit Policy Law 1 August 2023; 48 (4): 463–484. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-10451382

Download citation file:

- Reference Manager