How to Write War Essay: Russia Ukraine War

Understanding the Purpose and Scope of a War Essay

A condition of armed conflict between nations or between groups living in one nation is known as war. Sounds not like much fun, does it? Well, conflicts have been a part of human history for thousands of years, and as industry and technology have developed, they have grown more devastating. As awful as it might seem, a war typically occurs between a country or group of countries against a rival country to attain a goal through force. Civil and revolutionary wars are examples of internal conflicts that can occur inside a nation.

Your history class could ask you to write a war essay, or you might be personally interested in learning more about conflicts, in which case you might want to learn how to write an academic essay about war. In any scenario, we have gathered valuable guidance on how to organize war essays. Let's first examine the potential reasons for a conflict before moving on to the outline for a war essay.

- Economic Gain - A country's desire to seize control of another country's resources frequently starts conflicts. Even when the proclaimed goal of a war is portrayed to the public as something more admirable, most wars have an economic motivation at their core, regardless of any other possible causes.

- Territorial Gain - A nation may determine that it requires additional land for habitation, agriculture, or other uses. Additionally, the territory might serve as buffer zones between two violent foes.

- Religion - Religious disputes can stem from extremely profound issues. They may go dormant for many years before suddenly resurfacing later.

- Nationalism - In this sense, nationalism simply refers to the act of violently subjugating another country to demonstrate the country's superiority. This frequently manifests as an invasion.

- Revenge - Warfare can frequently be motivated by the desire to punish, make up for, or simply exact revenge for perceived wrongdoing. Revenge has a connection to nationalism as well because when a nation has been wronged, its citizens are inspired by patriotism and zeal to take action.

- Defensive War - In today's world, when military aggression is being questioned, governments will frequently claim that they are fighting in a solely protective manner against a rival or prospective aggressor and that their conflict is thus a 'just' conflict. These defensive conflicts may be especially contentious when conducted proactively, with the basic premise being that we are striking them before they strike us.

How to Write War Essay with a War Essay Outline

Just like in compare and contrast examples and any other forms of writing, an outline for a war essay assists you in organizing your research and creating a good flow. In general, you keep to the traditional three-part essay style, but you can adapt it as needed based on the length and criteria of your school. When planning your war paper, consider the following outline:

Introduction

- Definition of war

- Importance of studying wars

- Thesis statement

Body Paragraphs

- Causes of the War

- Political reasons

- Economic reasons

- Social reasons

- Historical reasons

- Major Players in the War

- Countries and their leaders

- Military leaders

- Allies and enemies

- Strategies and Tactics

- Military tactics and techniques

- Strategic planning

- Weapons and technology

- Impact of the War

- On the countries involved

- On civilians and non-combatants

- On the world as a whole

- Summary of the main points

- Final thoughts on the war

- Suggestions for future research

If you found this outline template helpful, you can also use our physics help for further perfecting your academic assignments.

Begin With a Relevant Hook

A hook should be the focal point of the entire essay. A good hook for an essay on war can be an interesting statement, an emotional appeal, a thoughtful question, or a surprising fact or figure. It engages your audience and leaves them hungry for more information.

Follow Your Outline

An outline is the single most important organizational tool for essay writing. It allows the writer to visualize the overall structure of the essay and focus on the flow of information. The specifics of your outline depend on the type of essay you are writing. For example, some should focus on statistics and pure numbers, while others should dedicate more space to abstract arguments.

How to Discuss Tragedy, Loss, and Sentiment

War essays are particularly difficult to write because of the terrible nature of war. The life is destroyed, the loved ones lost, fighting, death, great many massacres and violence overwhelm, and hatred for the evil enemy, amongst other tragedies, make emotions run hot, which is why sensitivity is so important. Depending on the essay's purpose, there are different ways to deal with tragedy and sentiment.

The easiest one is to stick with objective data rather than deal with the personal experiences of those who may have been affected by these events. It can be hard to remain impartial, especially when writing about recent deaths and destruction. But it is your duty as a researcher to do so.

However, it’s not always possible to avoid these issues entirely. When you are forced to tackle them head-on, you should always be considerate and avoid passing swift and sweeping judgment.

Summing Up Your Writing

When you have finished presenting your case, you should finish it off with some sort of lesson it teaches us. Armed conflict is a major part of human nature yet. By analyzing the events that transpired, you should be able to make a compelling argument about the scale of the damage the war caused, as well as how to prevent it in the future.

Tired of Looming Deadlines?

Get the help you need from our expert writers to ace your next assignment!

Popular War Essay Topics

When choosing a topic for an essay about war, it is best to begin with the most well-known conflicts because they are thoroughly recorded. These can include the Cold War or World War II. You might also choose current wars, such as the Syrian Civil War or the Russia and Ukraine war. Because they occur in the backdrop of your time and place, such occurrences may be simpler to grasp and research.

To help you decide which war to write about, we have compiled some facts about several conflicts that will help you get off to a strong start.

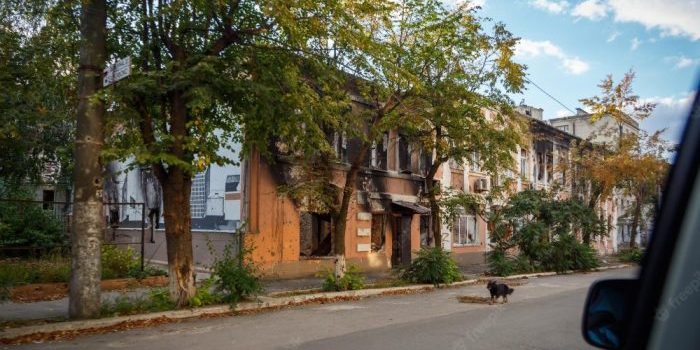

Russia Ukraine War

Russian President Vladimir Putin started the Russian invasion in the early hours of February 24 last year. According to him. the Ukrainian government had been committing genocide against Russian-speaking residents in the eastern Ukraine - Donbas region since 2014, calling the onslaught a 'special military operation.'

The Russian president further connected the assault to the NATO transatlantic military alliance commanded by the United States. He said the Russian military was determined to stop NATO from moving farther east and establishing a military presence in Ukraine, a part of the Soviet Union, until its fall in 1991.

All of Russia's justifications have been rejected by Ukraine and its ally Western Countries. Russia asserted its measures were defensive, while Ukraine declared an emergency and enacted martial law. According to the Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the administration's objective is not only to repel offensives but also to reclaim all Ukrainian land that the Russian Federation has taken, including Crimea.

Both sides of the conflict accuse the other of deploying indiscriminate force, which has resulted in many civilian deaths and displacements. According to current Ukraine news, due to the difficulty of counting the deceased due to ongoing combat, the death toll is likely far higher. In addition, countless Ukrainian refugees were compelled to leave their homeland in search of safety and stability abroad.

Diplomatic talks have been employed to try to end the Ukraine-Russia war. Several rounds of conversations have taken place in various places. However, the conflict is still raging as of April 2023, and there is no sign of a truce.

World War II

World War II raged from 1939 until 1945. Most of the world's superpowers took part in the conflict, fought between two military alliances headed by the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, and the Axis Powers, led by Germany, Italy, and Japan.

If you'd like to explore it more in-depth, consider using our history essay service for a World War 2 essay pdf sample!

After World War II, a persistent political conflict between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their allies became known as the Cold War. It's hard to say who was to blame for the cold war essay. American citizens have long harbored concerns about Soviet communism and expressed alarm over Joseph Stalin's brutal control of his own nation. On their side, the Soviets were angry at the Americans for delaying their participation in World War II, which led to the deaths of tens of millions of Russians, and for America's long-standing unwillingness to recognize the USSR as a genuine member of the world community.

Vietnam War

If you're thinking about writing the Vietnam War essay, you should know that it was a protracted military battle that lasted in Vietnam from 1955 to 1975. The North Vietnamese communist government fought South Vietnam and its main ally, the United States, in the lengthy, expensive, and contentious Vietnam War. The ongoing Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union exacerbated the issue. The Vietnam War claimed the lives of more than 3 million individuals, more than half of whom were Vietnamese civilians.

American Civil War

Consider writing an American Civil War essay where the Confederate States of America, a grouping of eleven southern states that seceded from the Union in 1860 and 1861, and the United States of America battled each other. If you're wondering what caused the civil war, you should know that the long-standing dispute about the legitimacy of slavery is largely responsible for how the war started.

The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

After over a century, the Israel-Palestine conflict has evolved into one of the most significant and current problems in the Middle East. A war that has claimed the lives of tens of thousands of people destroyed their homes and gave rise to terrorist organizations that still hold the region hostage. Simply described, it is a conflict between two groups of people for ownership of the same piece of land. One already resided there, while the other was compelled to immigrate to this country owing to rising antisemitism and later settled there. For Israelis and Palestinians alike, as well as for the larger area, the war continues to have substantial political, social, and economic repercussions.

The Syrian Civil War

Pro-democracy protests broke out in southern Deraa in March 2011 due to upheavals against oppressive leaders in neighboring nations. When the Syrian government employed lethal force to quell the unrest, widespread protests calling for the president's resignation broke out.

The country entered a civil war as the violence quickly increased. After hundreds of rebel organizations emerged, the fight quickly expanded beyond a confrontation between Syrians supporting or opposing Mr. Assad. Everyone believes a political solution is necessary, even though it doesn't seem like it will soon.

Russia-Ukraine War Essay Sample

With the Russian-Ukrainian war essay sample provided below from our paper writing experts, you can gain more insight into structuring a flawless paper.

Why is there a war between Russia and Ukraine?

Final Words

To understand our past and the present, we must study conflicts since they are a product of human nature and civilization. Our graduate essay writing service can produce any kind of essay you want, whether it is about World War II, the Cold War, or another conflict. Send us your specifications with your ' write my essay ' request, and let our skilled writers help you wow your professor!

Having Hard Time Writing on Wars?

From the causes and consequences of wars to the strategies and tactics used in battle, our team of expert writers can provide you with a high-quality essay!

Related Articles

.webp)

Home » Writing a Compelling War Essay: Crafting a Powerful Narrative of the Russia Ukraine War 2022

Writing a Compelling War Essay: Crafting a Powerful Narrative of the Russia Ukraine War 2022

Writing a compelling war essay can be a daunting task. It requires a deep understanding of the subject matter and a keen sense of story-telling to craft a powerful narrative that captures the essence of the Russia Ukraine War 2022. In this blog article, we will explore the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, the historical context of the war, and the elements of a powerful essay. We will also look at strategies for researching and presenting the evidence in the essay, as well as tips for writing and editing the essay. Finally, we will discuss how to review the essay before submission.

Understanding the conflict between Russia and Ukraine

The conflict between Russia and Ukraine is not a new one. In fact, the two countries have been at odds since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Russia has long been an ally of Ukraine, with the two countries sharing both a cultural and political history. However, tensions have been escalating in recent years due to the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the ongoing war in eastern Ukraine.

The conflict between Russia and Ukraine is primarily driven by geopolitics and economics. Russia sees Ukraine as a strategic buffer against the West and as a potential market for its energy resources. Ukraine, on the other hand, is keen to assert its independence from Russia and has sought to strengthen its ties with the West. This has led to a number of clashes between the two countries, including the current ongoing conflict in the Donbas region of Ukraine.

The Russia Ukraine War 2022 is a major event in world history and has had a profound impact on both countries. It is, therefore, important to understand the conflict and its implications in order to write a compelling war essay.

Historical context of the Russia Ukraine War and its implications

In order to write a powerful narrative of the Russia Ukraine War 2022, we should understand the historical context of the conflict. The conflict between Russia and Ukraine dates back to the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, when Ukraine declared its independence from Russia. The two countries have since been locked in a tense and often hostile relationship, with Russia attempting to reassert its influence over Ukraine and Ukraine striving to maintain its independence.

The conflict escalated in 2014 when Russia annexed Crimea, sparking outrage in the international community. This led to the imposition of sanctions on Russia by the European Union and the United States. In response, Russia has continued to support separatist forces in eastern Ukraine, leading to the ongoing war in the Donbas region.

The Russia Ukraine War 2022 is the culmination of this long and bitter conflict. The war has had far-reaching implications, not only for the two countries involved, but for the entire region and beyond.

Crafting a powerful narrative: Elements of a compelling War Essay

Writing a powerful narrative of the Russia Ukraine War 2022 requires an in-depth understanding of the conflict and its implications. A compelling war essay should include a clear thesis statement and well-structured argument. It should also include evidence to support the argument, as well as an analysis of the sources used.

In order to craft a powerful narrative, it is necessary to understand the key elements of a compelling war essay. These include:

-A clear and concise thesis statement -An understanding of the historical context of the conflict -A well-structured argument -Evidence to support the argument -An analysis of the sources used -A conclusion that ties together all the elements of the essay

By incorporating these elements into the essay, it is possible to craft a powerful narrative of the Russia Ukraine War 2022.

Analyzing and evaluating the sources used in the essay

To writing a compelling war essay, using reliable sources that provide accurate information is important. It is also important to analyze and evaluate the sources in order to determine their credibility.

When analyzing sources, we should consider the source’s reliability, accuracy, and relevance. Sources should be reviewed for bias and possible errors. It is also important to look at the date of publication and the author’s credentials.

When evaluating sources, we need to consider the evidence presented in the source. Does the evidence support the argument? Is the evidence presented in a fair and balanced manner? Does the evidence contradict or support other sources?

By analyzing and evaluating the sources used in the essay, it is possible to ensure that the argument is supported by reliable evidence.

Writing an effective thesis statement

The thesis statement is the cornerstone of any essay, a thesis statement should clearly and concisely state the main argument of the essay. It should also be specific and clearly identify the focus of the essay.

When writing a thesis statement for a war essay, we should consider the scope of the essay. The thesis statement should be broad enough to cover all the elements of the essay, but not so broad that it becomes vague or unfocused.

It is also important to take a stance on the issue. The thesis statement should make a clear and unambiguous argument. It should not be vague or open-ended.

By writing an effective thesis statement, it is possible to set the stage for a powerful and compelling narrative of the Russia Ukraine War 2022.

Structuring the essay: outlining and introduction, body, and conclusion

Once the thesis statement has been written, structure the essay into an introduction, body, and conclusion. The introduction should provide an overview of the essay, as well as a brief explanation of the thesis statement.

The body of the essay should include evidence to support the argument, as well as an analysis of the sources used. It should also include a discussion of the implications of the war.

The conclusion should tie together all the elements of the essay and provide a brief summary of the argument. It should also include a call to action, if applicable.

By outlining the essay and structuring it into an introduction, body, and conclusion, it is possible to create a powerful narrative of the Russia Ukraine War 2022.

Strategies for researching and presenting the evidence for the essay

In order to write a compelling war essay, it is important to research the subject thoroughly and present the evidence in a clear and concise manner.

When researching for the essay, we need to use a variety of sources, including primary and secondary sources. Primary sources, such as news articles, are direct sources of information about the war. Secondary sources, such as books and academic journals, provide an in-depth analysis of the conflict.

When presenting the evidence, it is important to be clear and concise. Evidence should be presented in a logical order, with each point supporting the argument. Also don’t forget to cite all sources used in the essay.

By following these strategies for researching and presenting the evidence, it is possible to create a compelling narrative of the Russia Ukraine War 2022.

Writing and editing the essay

Once the research has been completed and the evidence has been presented, it is time to write the essay. Our essay should be clear and concise. The argument should be well-structured, with each point building on the previous one.

It is also important to use language that is appropriate for the subject matter. The tone of the essay should be appropriate for the topic, and the language should be clear and concise.

Once the essay has been written, the final step in writing a war essay is editing and proofreading. Editing involves making changes to the structure, tone, and content of the essay. Proofreading involves checking essay for any errors in grammar, punctuation, and spelling.

By writing and editing the essay, it is possible to craft a powerful narrative of the Russia Ukraine War 2022.

Reviewing the essay before submission

Before submitting the essay, we need to review it carefully. It is important to make sure that the essay is well-structured and that the argument is clear and concise. The used sources are reliable and accurate. Essay is within the word limit and that it follows the instructions provided by the instructor.

By reviewing the essay before submission, it is possible to ensure that the essay is of the highest quality.

Writing a compelling war essay about the Russia Ukraine War 2022 requires a deep understanding of the conflict and its implications.

While crafting a compelling war essay, it is necessary to understand the elements of a powerful narrative and to analyze and evaluate the sources used. It is also necessary to write an effective thesis statement and structure the essay into an introduction, body, and conclusion. Author should research and present the evidence in a clear and concise manner. Finally, a complete review the essay before submission.

Writing a powerful narrative of the Russia Ukraine War 2022 can be a daunting task, but it is possible with the right approach. By following the tips outlined in this blog article, it is possible to craft a compelling war essay that captures the essence of the war.

By Lily James

You might also like:.

Understanding Plagiarism: Types, Consequences, and Prevention

The Renaissance Writer: Inspiring Brilliance in Academic Prose

How to Write a Captivating Introduction for Your Academic Paper

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Enjoy this blog? Please spread the word :)

How to Win Wars: The Role of the War Narrative

- First Online: 10 May 2017

Cite this chapter

- Tone Kvernbekk 3 &

- Ola Bøe-Hansen 4

Part of the book series: Argumentation Library ((ARGA,volume 31))

964 Accesses

3 Citations

8 Altmetric

One might think it is obvious in a military conflict who has won and who has lost. But is it? It seems to be commonly accepted that the Americans actually lost the Vietnam War, even though they won all or most of the actual battles on the ground. Wars, modern military theory states, are not won on the battlefield – they are won in people’s minds, in the cognitive domain. To secure the support of the population for participating in military operations a government must therefore present good, persuasive reasons. Such reasons have come to be called “war narratives”. A war narrative can be seen as a reason whose job it is to bolster the conclusion that participation in a war, often far away from home territory, is legitimate and right. In this chapter we discuss the content and function of war narratives: what they say; why they arise; the audiences they are aimed at, and how they fare over time. This latter issue is particularly important, we suggest, because war narratives may erode if or when counter-evidence piles up as military events unfold. If that happens the narrative becomes a liability to its narrator. The audience becomes skeptical and retracts its support – the narrative fails to persuade and the war might be lost.

- Cognitive Domain

- Security Council

- Target Audience

- Strategic Communication

- Universal Audience

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Aristotle. 1982. The Poetics. Trans. James Hutton. New York: W. W. Norton.

Google Scholar

Bitzer, L. 1968. The rhetorical situation. Philosophy & Rhetoric 1 (1): 1–14.

Bøe-Hansen, O. 2013. Narrativets rolle i den nasjonale strategien [The role of the narrative in the national strategy]. In Strategisk suksess – norsk maktbruk i Libya og Afghanistan [Strategic success – Norwegian use of force in Libya and Afghanistan], ed. O. Bøe-Hansen, T. Heier and J.H. Matlary, 42–57. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

———. 2014. Narrativet som maktfaktor i internasjonale operasjoner [The narrative as a power factor in international operations]. In Norge i internasjonale operasjoner: militærmakt mellom idealer og realpolitik [Norway in international operations: between ideals and reality], ed. T. Heier, A. Kjølberg and C.F. Rønnfeldt, 54–63. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

British National Security Council. 2012. Joint doctrine note 1/12, strategic communication: The defence contribution . Shrivenham: Development, Concepts and Doctrine Center.

Bruner, J. 2002. Making stories. Law, literature, life . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Burke, K. 1945. A grammar of motives . New York: Prentice-Hall.

Clausewitz, C. Von. 1976. On war . Princeton University Press: Princeton. Originally published 1832.

Danto, A.C. 1985. Narration and knowledge . New York: Columbia University Press.

Defence Staff Norway. 2007. Norwegian armed forces joint operational doctrine . Oslo: The Defence Staff.

De Graaf, B., G. Dimitriu, and J. Ringsmose, eds. 2015. Strategic narratives, public opinion, and war . Oxford/London: Routledge.

Goldman, E. 2007. Strategic communication: A tool for asymmetric warfare. Small Wars Journal : 1–7.

Govier, T. 1999. The philosophy of argument . Newport News: Vale Press.

Johnson, R. 2013. The role of audience in argumentation from the perspective of informal logic. Philosophy and Rhetoric 46 (4): 533–549.

Article Google Scholar

Joint Forces Commanders. 2006. Joint publication 3–13, Information Operations, Joint Chiefs of Staff Official Norwegian Reports 2016:8 (NOU). A good ally – Norway in Afghanistan 2001–2014.

Ornatowski, C.M. 2012. Rhetoric goes to war: The evolution of the United States of America’s narrative of the “War on terror”. African Yearbook of Rhetoric 3 (3): 65–74.

Perelman, C., and L. Olbrechts-Tyteca. 1969. The new Rhetoric. A treatise on argumentation . Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Ricoeur, P. 1984. Time and narrative . Vol. I. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Riessman, C.K. & J. Speedy. 2007. Narrative inquiry in the psychotherapy professions: A critical review. In Handbook of narrative inquiry , ed. D.J. Clandinin, 426–456. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Rodden, R. 2008. How do stories convince us? Notes towards a rhetoric of narrative. College Literature 35 (1): 148–173.

Shea, J.P. 2002. The Kosovo crisis and the media: Reflections of a NATO spokesman. In Lessons from Kosovo – The KFOR experience , ed. L. Wentz. Washington, DC: Department of Defense Command and Control Research Program (DoD CCRP).

Tindale, C. 1992. Audiences, relevance, and cognitive environments. Argumentation 6: 177–188.

———. 2013. Rhetorical argumentation and the nature of audience: Toward an understanding of audience-issues in argumentation. Philosophy and Rhetoric 46 (4): 508–532.

Vlahos, M. 2006. The long war: A self-fulfilling prophecy of protracted conflict – And defeat. The National Interest. http://nationalinterest.org/?id=11982 .

White, H. 1978. The historical text as literary artifact. In The writing of history , ed. R.H. Canary and H. Kozicki, 41–62. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Web 1. http://www.historyplace.com/speeches/fdr-infamy.htm .

Web 2. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/sep/21/september11.usa13.

Web 3. http://salempress.com/store/pdfs/bin_laden.pdf .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Education, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Tone Kvernbekk

Department of Veterans Affairs, Norwegian Armed Forces, Oslo, Norway

Ola Bøe-Hansen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tone Kvernbekk .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Linguistics, Modern Languages, Logic and Philosophy of Science, Theory of Literature and Comparative Literature, Autonomous University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain

Paula Olmos

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Kvernbekk, T., Bøe-Hansen, O. (2017). How to Win Wars: The Role of the War Narrative. In: Olmos, P. (eds) Narration as Argument. Argumentation Library, vol 31. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56883-6_12

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56883-6_12

Published : 10 May 2017

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-56882-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-56883-6

eBook Packages : Religion and Philosophy Philosophy and Religion (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Advertisement

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Introduction

Existing explanations for why the u.s. war in afghanistan ended, trauma, narratives, and war, the narrative emerges and settles in, the narrative peaks, the narrative declines, narratives and war: explaining the length and end of u.s. military operations in afghanistan.

Associate Professor of Politics and International Affairs and the Shively Family Faculty Fellow at Wake Forest University.

Supplemental material available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/82RNG7

- Cite Icon Cite

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Permissions

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Search Site

C. William Walldorf; Narratives and War: Explaining the Length and End of U.S. Military Operations in Afghanistan. International Security 2022; 47 (1): 93–138. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00439

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Why did the U.S. war in Afghanistan last so long, and why did it end? In contrast to conventional arguments about partisanship, geopolitics, and elite pressures, a new theory of war duration suggests that strategic narratives best answer these questions. The severity and frequency of attacks by al-Qaeda and the Islamic State across most of the 2000s and 2010s generated and sustained a robust collective narrative across the United States focused on combatting terrorism abroad. Audience costs of inaction generated by this narrative pushed President Barack Obama (2009) and President Donald Trump (2017) to not only sustain but increase troops in Afghanistan, against their better judgement. Strategic narratives also explain the end to the war. The defeat of the ISIS caliphate and a significant reduction in the number of attacks on liberal democratic states in the late 2010s caused the severity and frequency of traumatic events to fall below the threshold necessary to sustain a robust anti-terrorism narrative. As the narrative weakened, advocates for war in Afghanistan lost political salience, while those pressing retrenchment gained leverage over policy. Audience costs for inaction declined and President Joe Biden ended the war (2021). As President Biden seeks to rebalance U.S. commitments for an era of new strategic challenges, an active offshore counterterrorism program will be necessary to maintain this balance.

In May 2017, amid yet another intense national debate about increasing troops in Afghanistan, President Donald Trump asked Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC), “How does this end?” Graham answered, “It never ends.” Soon after, Vice President Mike Pence implored Graham to give Trump an off-ramp, some kind of exit strategy. According to Bob Woodward, Graham responded, “It would never end.” 1

Until Trump's 2020 troop reduction and, especially, President Joe Biden's 2021 decision to end combat operations entirely, Graham's counsel seemed almost prophetic. Despite long-standing countervailing pressures at home (e.g., lobbying by advocates of restraint, public disdain for the war, as well as the pro-withdrawal sentiments of Biden and his two immediate predecessors), the United States stayed in Afghanistan for two decades. 2 What sustained this war for so long, and what allowed Trump to begin and Biden to complete the drawdown?

Conventional arguments in international relations about geopolitics, elites (e.g., “the Blob”), 3 and partisanship struggle to answer these questions. Given these shortcomings, this article turns to a new theory of war duration to explain the length and end of the U.S. war in Afghanistan. The approach centers, at the broadest level, on collective national will or purpose. It does so, more specifically, by focusing primary causal attention on a largely underappreciated yet historically important factor in U.S. foreign policy: strategic narratives. 4

I define strategic narratives as collective national or public-level stories that form out of and center around traumatic events for a group. These events come to be viewed in existential terms as a danger to the national way of life. By collective, I mean that narratives are properties of groups or social facts, like culture. For a nation-state, a narrative becomes collectively salient because it restores order by explaining the pain, assigning blame, and, most importantly, setting lessons going forward to avoid a return to the pain of the past. These lessons are often reflected in a simple mantra—such as “No More Vietnams” or “Stop Terrorism”—that takes on a life of its own in ways that determine national interests to pursue abroad and shape policy debates over time. 5

This article focuses on one especially important type of strategic narrative—the liberal narrative—in the history of U.S. foreign policy. A robust liberal narrative is distinguished by its lesson, notably the need to safeguard liberal political order abroad, “either by promotion (i.e., expanding democracy and liberal rights) or protection (i.e., preventing the spread of counter-ideologies to liberalism).” 6 The liberal narrative manifests in temporally unique variants such as the anti-fascist narrative of the 1930s and 1940s and the anti-communist narrative during the Cold War. With lessons to defend freedom and stop counter-ideologies from spreading, both shared a commitment to protect liberal political order, making them “liberal narratives.” 7

Historically, liberal narratives like these affect policy through the contested nature of democratic politics. At key decision points about the use of force, powerful narratives augment in predictable ways some voices over others in policy debates. Specifically, by tapping into or drawing upon the lessons of a prevailing narrative, agents gain influence by building policy discourses that increase leaders' perceived audience costs, which are defined as the “domestic political price” that leaders pay for choices that are at odds with strong public preferences. 8 Given a narrative's public salience, leaders fear potential electoral or policy losses and, in turn, tend to bring their decisions in line with these narrative-augmented discourses, sometimes against their better judgment. 9

This strategic-narrative argument helps explain the length and end of the U.S. war in Afghanistan. The severity of the September 11 terrorist attacks coupled with the frequency of follow-on attacks globally by al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (ISIS) into the late 2010s generated and sustained a powerful collective story across the U.S. body politic of missed opportunities by U.S. leaders and a lesson to combat terrorism abroad. This anti-terrorism narrative is the most recent variant of a robust liberal narrative in the U.S. policy process. At various decision points, the narrative created space for promoters of war (especially in the U.S. military) to generate discourses that raised audience costs of inaction and politically boxed in presidents to sustain or expand the U.S. war in Afghanistan. Concerns about looking “soft” and not measuring up to narrative standards shaped the decisions of both President Barack Obama and Trump (early in his term) to stay engaged militarily. In recent years, narrative measures show that as the severity and frequency of terrorist attacks receded (i.e., collapse of the ISIS caliphate, absence of severe al-Qaeda attacks), the anti-terrorism narrative also lost policy salience. Moderators (in this case, civilian leaders and policy experts) gained leverage, audience costs of inaction declined, and restraint gained traction in policy debates. Like event-driven narrative dynamics (i.e., following the killing of Osama bin Laden) that allowed Obama to withdraw from Iraq in 2011, the national sense of purpose in Afghanistan waned, creating political space for Trump to decrease troops and for Biden to end the war entirely.

The strategic-narrative argument builds upon and fills important gaps in existing scholarship. In contrast to standard rationalist accounts, it explores the social construction of audience costs and offers new insights into how narratives shape policy outcomes. The argument also turns to the framework of cultural trauma to explain strategic narratives more systematically. 10 In contrast to some accounts that focus primarily on influential agents to explain how narratives form and endure, trauma theory draws primary attention to the importance of events (e.g., September 11). When collectively viewed as existentially dangerous, these events spark new narratives such as the anti-terrorism narrative. Similar follow-on events over time re-traumatize the nation, helping maintain the salience of the narrative as a lodestar for foreign policy for years or even decades on end. Among other things, this trauma framework best accounts for the long-standing vitality of the anti-terrorism narrative in U.S. politics that other arguments about narratives struggle to explain.

This article turns first to conventional explanations, specifically arguments centered on potential changes in Afghanistan's geostrategic value to the United States, the shifting partisan preferences of different presidential administrations, variation in elite ideological or consensus-based pressures, and shifts in civil-military relations. The second and third sections detail the strategic-narrative argument and methods. Sections four through six present the Afghanistan case studies. The article concludes with policy implications.

The war in Afghanistan was the centerpiece of U.S. forever wars across the first two decades of the 2000s. Presidents Obama, Trump, and Biden conducted major policy reviews early in their administrations. The first two opted against withdrawal and increased troops instead—Obama by 30,000 in 2009 and Trump by 4,000 in 2017. Three years later, Trump began—and Biden completed—the withdrawal. What explains this change?

Standard explanations struggle to answer this question. Realists see no geostrategic value in nation-building wars like Afghanistan. Although the end of the war makes sense to realists, its duration does not. 11 Partisan arguments offer no clear explanation either—Obama (D) continued President George W. Bush's (R) policy that Trump (R) also initially followed before shifting to withdrawal, which Biden (D) elected to continue. 12 Elite-based arguments fare poorly, too. For those who focus on elite ideology, reduced elite ideological concerns about Afghanistan over the past decade (e.g., Obama on the overreaction to September 11 and talks of terrorism as nonexistential) should have meant that the United States ended the war years ago. Therefore, why the United States stayed so long and what changed to allow Biden to leave when others could not is puzzling. 13 This is not to say that ideology is irrelevant; it affects how narratives form, but in ways that the narrow focus in extant work on elites alone does not capture well. 14 Alternatively, some scholars argue that a powerful establishment consensus aimed at sustaining U.S. “liberal hegemony” explains U.S. wars in the Middle East. In short, elites want forever wars and get what they want. 15 But if this theory is correct, then how did Biden end the war? As a constant, establishment consensus cannot explain this, nor can it explain many other decisions for retrenchment, such as Obama's choice in 2011 to withdraw all troops from Iraq and his refusal to enforce the Syrian “red line” in 2014.

Finally, I suggest that the strongest conventional argument comes from the civil-military relations literature. When the military enters the political fray with dire public warnings of danger ahead for the nation, some scholars argue that civil-military relations tilt toward the military in ways that often lead to strategically suboptimal outcomes, such as continuing stalemated forever wars. In contrast, these kinds of wars result in retrenchment only when civilians regain the upper hand, especially by muzzling the military in public. 16

The problem with this argument is not that it is wrong. In fact, the strategic-narrative argument I develop here agrees that the balance between military leaders as powerful promoters of war and civilian leaders as moderators of war is important. Not surprisingly, then, when military leaders went public (or threatened to do so) in the Obama and Trump periods, civilian leaders capitulated, troops increased, and war continued. In the Biden period, however, civilians carried the upper hand, the military chose not to go public with its preferences to continue the fight, and the president ended the war. In a broad sense, the cases match civil-military expectations.

This argument's greatest shortcoming comes with explaining change, which is the main puzzle of this article. If the civil-military relations balance is critical to both the continuation of and the end to forever wars, such as the war in Afghanistan, why does that balance tilt one way or the other at different times? More specifically, why does the military go public sometimes and not others, why and how do the public appeals of the military generate pressure on civilian leaders, and under what conditions are civilians able to muzzle the military and, in so doing, gain more leverage over policy?

The politics of strategic narratives help answer questions like these. The civil-military balance generally favors the military when there is a robust liberal narrative—such as the anti-terrorism narrative from 2001 to 2018. The narrative gives military promoters (and their civilian supporters in government) an important political tool to build public pressure on civilian leaders in order to continue/expand war. Military leaders are most likely to go public (or threaten to do so) under such narrative conditions. Civilian leaders—fearful of the political costs of not measuring up to narrative standards (i.e., looking “weak” or “losing”)—capitulate to military pressure. But when a liberal narrative weakens, the civil-military balance often tilts toward the former. Military promoters find themselves on more tenuous ground in policy debates. In the absence of nationwide, narrative-driven fervor to intervene militarily in conflicts abroad, the military tends to hesitate about going public with its preferences for more force. As the public costs of looking weak recede with the weakened liberal narrative, civilians/moderators find more political space to assert themselves, both in internal debates and in public. Long wars such as the U.S. war in Afghanistan often come to an end.

In sum, the nexus between civil-military relations and strategic narratives provides deeper insights into why long wars endure and ultimately end. International relations scholars have shed a great deal of light on the former but not on the latter. For that reason, I now turn greater attention to the narrative side of this equation.

Narratives are not new to the field of international relations. The existing literature on narratives faces two primary shortcomings, though. 17 First, scholars offer no clear explanation for why and when narratives shape policy outcomes, like decisions to continue or end forever wars. My attention to audience costs corrects for this. Second, in explaining how narratives strengthen and weaken over time, existing scholarship gives primary attention to narrators—especially the president in the U.S. context. 18 Although narrators (and sometimes presidents, as such) are important, these arguments tend to overlook how events shape strategic narratives' content and strength across time. In the mid-2010s, President Obama tried to re-narrate and dampen terrorism worries in the United States, for instance. He largely failed because most U.S. citizens viewed Obama's new story as being out of touch amid a surge in ISIS terrorist attacks. The president told the wrong story at the wrong time. Events matter.

I start with scholarship on collective trauma, which draws attention to two particularly important concepts: the severity and the frequency of events. Neil Smelser defines cultural trauma as “a memory accepted and given public credence by a relevant membership group and evoking an event(s) or situation(s) which is a) laden with … affect, b) represented as indelible, and c) regarded as threatening a society's existence or violating one or more of its fundamental cultural presuppositions.” 19 Building off this definition, trauma involves three stages that leave behind marks on society, essentially new prevailing narratives. The strategic-narrative argument starts with identity, which determines what a community values most. Stage one involves severe events that are perceived as an attack on these values, an existential challenge making them traumatic. 20 This severity produces deep emotional reactions—“disgust, shame, guilt … or anxiety”—for a community, which leads quickly to stage two of trauma, notably a collective search for new “routines” and ways to “get by in the world.” 21 Above all else, the affected community looks to presumed wise figures in society for explanation and ways forward. 22

Stage three of trauma—the formation of new collective narratives—emerges from these explanations. Many enter the fray amid severity, often telling competing stories. Specific kinds of severity resonate with the injured group in ways that privilege some stories over others. 23 As a result of the disquiet generated by certain events, some stories become affirmed, validated, and collectively labeled as “good.” Storytellers gain a hearing, according to Jeffrey Alexander, when they “represent social pain as a fundamental threat to … [a group's] sense of who they are.” 24 If severe events repeat frequently, privileged stories resonate deeper and longer. High frequency re-traumatizes the collective, which makes the story indelible (i.e., “see, I told you so”) and helps sustain it over time as the new collective wisdom—or prevailing narrative—with new ways of being going forward. 25

This latter element—new directions toward repair—is a natural part of trauma-generated narratives. Effective storytellers repeatedly narrate ways for “defense and coping,” drawing attention to “mistakes and how they may be avoided in the future” (i.e., blame and lesson). 26 These lessons are often encapsulated in slogans such as “no more Vietnams,” “no more 9/11s,” or “who lost China?” (which helped propel intervention in Korea and Vietnam). Lessons and severe event(s) are intrinsically connected in narratives—the latter gives meaning to the former. 27

This trauma framework—centered on the severity and frequency of events—helps explain the emergence and cross-temporal strength of strategic narratives in U.S. foreign policy. 28 For this article, I grant special attention to one kind of trauma—external trauma—and the type of narrative that it tends to generate. Trauma theorists find that severe event(s) from some force outside a community leads to group unity around a story centered on protecting the ideals of the community—that is, “who we are”—as a means of defense or repair. 29 This external trauma helps explain the emergence and strength of liberal narratives (such as the anti-terrorism narrative) that centers on activism abroad to defend or promote liberal political order.

Liberal states (including the public in these states) view other states and developments in the international system through the ideological lens of their own regime type (i.e., identity)—they notice and worry about the plight of liberal order abroad because it threatens their own security. 30 The severe events most likely to spark stage one of trauma emerge when ideologically distant—in this case illiberal—rival(s) make strategic gains, especially through either a direct attack on the United States or a series of attacks on other kindred liberal or liberalizing states. Like the ideology literature in international relations, I argue that these kinds of strategic shifts are not objective, as realists expect. Instead, their impact on a polity is conditioned by state identity. 31 When these attacks produce civilian casualties and/or lead to the expansion of illiberal governments abroad, collective anxiety around existential danger to the national way of life rises exponentially. This sense of existential panic around high-severity events comes almost immediately after direct attacks (e.g., Pearl Harbor or September 11). 32 With indirect attacks on ideological kin, geographic distance from the target often means that it takes several accumulated attacks to generate the same collective sense of severity and, with that, collective trauma. 33

Whether their pathway is direct or indirect, high-severity attacks lead to stages two and three of trauma. Many of society's “wise figures” will engage in storytelling in stage two. External trauma privileges stories from agents who I call “promoters,” those who validate public fears of existential danger and the need to defend liberal order abroad. 34 If rival gains come via direct attack, promoter stories immediately prevail and the liberal narrative strengthens quickly. 35 If attacks are indirect, the slower growth of severity means that promoter stories gain acceptance more slowly, too. In stage three, repeated rival attacks/gains validate the promoter story, giving it collective strength. Finally, the frequency of events sustains narrative strength and salience over time. In a path-dependent way, the liberal narrative remains robust if an ideological rival regularly continues (i.e., at least every two or three years) to make gains, especially if it either directly or indirectly attacks other ideologically kindred (in this case, liberal or liberalizing) states. 36 In essence, frequent and severe challenges abroad perpetually re-traumatize the nation, giving a robust liberal narrative ongoing strength and vitality. 37

The dominant variant of the liberal narrative during the Cold War—the anti-communist narrative—offers a good example of the theory. In the 1940s, the U.S. public was traumatized by a cascade of Soviet ideological gains: communist advances in East-Central Europe, atomic bomb tests, an alliance with newly communist China, and support of the Korean War. This development shut out moderate voices, such as progressive Vice President Henry A. Wallace, and allowed promoters to establish a robust liberal narrative around stopping communism. For much of the forty years that followed, frequent demonstrations of communist-bloc strength (i.e., Sputnik, gains in Africa and Asia, the Cuban Revolution, and the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan) re-traumatized the United States, keeping the anti-communist narrative robust. 38

There are two potential pathways by which severity and frequency can weaken the liberal narrative. First, the narrative will weaken most profoundly and substantially when an ideological rival experiences a debilitating defeat or changes its ideology altogether. These kinds of positive events generate what Emile Durkheim calls “success anomie,” or a collective sense of lost purpose for the nation that makes the old narrative appear antiquated as a guide for policy. 39 Positive events profoundly weaken a temporal variant of the liberal narrative for years to follow—this becomes permanent if a rival fails to rebuild.

Second, narrative weakening could also occur when either trauma-generating strategic gains by an ideological rival cease for at least four years, or when a rival takes accommodating steps to reduce tension. This absence of negative events can also produce success anomie. When either scenario happens, the frequency and severity of traumatic events fall below the threshold necessary to sustain a robust liberal narrative. In these conditions, especially when marked by the positive event of a rival's debilitating defeat, a political opportunity space emerges for certain agents who I call “moderators” to engage in storytelling about reduced ideological danger and restraint abroad. U.S. presidents sometimes become moderators, but as Obama found out the hard way, their success as storytellers depends on the event-driven context. That is, they must tell the right story at the right time. 40 The liberal narrative weakens under these conditions of rival decline or absence of negative events; retrenchment settles in as the new lodestar for the polity. For example, the liberalization and eventual collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 initiated a major re-narration by moderators. As a result, the anti-communist narrative disappeared from discussions of U.S. foreign policy.

narrative discourses and war

Narratives shape policy outcomes—such as decisions to sustain or end wars—by raising audience costs. Standard accounts demonstrate that audience costs emerge when heads of state bind themselves by making a public commitment to action abroad. 41 Audience costs from strategic narratives form in a different way, however, notably through social construction. 42 At key decision points, agents (promoters or moderators) use strategic narratives to build discourses for or against war. These discourses generate different domestic political cost-benefit scenarios: high audience costs of action, or high audience costs of inaction. 43 While not required for these kinds of discourses to form, appeals by leaders with robust narratives as a justification for policy may help fuel these narrative-driven discourses and elevate audience costs. Leader pledges (i.e., the conventional audience-cost argument) can matter, then, but only if they are linked to prevailing narratives. Regardless of their contributions to the process, democratic leaders worry about future elections or their broader policy agendas (i.e., the potential political consequences of elevated audience costs) when facing robust, narrative-based discourses. Consequently, leaders usually bring policy in line with the narrative discourses that agents build around them.

For starters, I assume that at any major policy decision point, both promoters and moderators will be present to advocate their different positions. Liberal war continuation (and expansion) is most likely when a strong liberal narrative develops at key decision points in a conflict. Here, a robust liberal narrative (meaning, again, an elevated national passion to protect liberal order abroad) augments promoter arguments. This gives promoters a special hearing with the public and in policy debates generally. 44 Promoters know this and use the liberal narrative to create (or policymakers fear they will create) broad public movements, which raises audience costs of inaction. In wartime, military leaders are often also promoters, and strategic narratives tip the civil-military balance in their favor. Civilian leaders who do not support continuing or expanding military action fear losing future elections or policy goals, and thus some bring their policies in line with promoters' arguments. Others get “pushed to act” against their better judgment to continue or expand liberal wars.

Sometimes, these reluctant leaders ironically help create the strong liberal discourses that later push them along. In the 1960 presidential campaign, President John F. Kennedy intentionally took a tough position against Fidel Castro's communist regime in Cuba to enhance his anti-communist credentials with voters. This stance helped Kennedy win the White House, but it also boxed him in once in office. As promoters in Congress built a robust discourse around anti-communism for a tough policy in 1961, the political costs of looking weak on communism proved too high for Kennedy to pursue his preferred course of normalizing relations with Castro's regime. The 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion followed. 45

Liberal wars end as liberal discourse weakens. Because of a national sense of lost purpose, moderator appeals (which often come from civilians in wartime) resonate more in policy debates as the liberal narrative weakens. Promoter arguments tend to appear odd, by contrast, maybe even extreme. Consequently, promoters often go quiet, especially in public. 46 In this scenario, leaders face lower audience costs of inaction, and they may in fact perceive higher audience costs of action given the absence of a national passion for war. In this latter scenario, leaders worry about the domestic political dangers of carrying on or expanding the war. As a result, a weak liberal discourse allows leaders who prefer ending a liberal war to do so, and it pushes those leaders who prefer to continue fighting to instead phase down or end military action. During the 1990s, moderators inside President Bill Clinton's administration repeatedly pointed to flagging public support for things like democracy building and humanitarian intervention (i.e., a weak liberal discourse). 47 This discourse constrained military options for Clinton, especially in the Balkans, throughout his administration. 48

I combine congruence and comparative case study methods to test the strategic-narrative argument in decisions for troop increases in Afghanistan by Obama (2009) and Trump (2017) against Biden's decision to withdraw (2021). 49 For space reasons and because Biden made the final decision, I devote less attention to Trump's 2020 pledge to withdraw. The cases are good for comparison, holding several background factors constant, such as war (Afghanistan) and period (post-9/11). The Obama-Biden cases are especially good for comparison because they share a common policy approach and party affiliation, but they lead to different outcomes. Outcome variation avoids sampling on the dependent variable.

Tautology is a pitfall for any ideational argument. To avoid this, I use a method of symbolic structuring of discourse to assess narrative strength and its component parts (i.e., severity and frequency) at time t-1, meaning independent of and prior to the decision-making process. 50 Narrative strength is measured in each case study using content analysis of newspaper editorials and the Congressional Record (see the online appendix), along with secondary sources and public opinion polls. Editorials reflect the collective national discussion across the country around specific events at specific points in time. Consequently, they are a well-established tool for measuring collective ideas, like narratives. Scholars find that patterns in the Congressional Record do the same—in a mutually constitutive way, authoritative actors both reflect and help reinforce prevailing narrative trends in any given period. 51

For the Afghan cases, I first scanned the historical record for geostrategic gains that were likely to reach the threshold of severity required to spark trauma and the initial narrative-making process. Most notably, examples include any attacks by an illiberal actor on the United States or other liberal states that caused civilian casualties or threatened to spread illiberalism. Second, and most importantly for the strategic-narrative argument in this article, I then scanned the historical record beyond the initial trauma for any similar follow-on severe attacks. If the strategic-narrative argument is correct, the above measures should demonstrate that a direct attack on the United States, or a series of indirect attacks on strategic partners (i.e., severity), open(s) space for promoters and generates a new liberal narrative centered on existential danger, blame, and a lesson to get active abroad against a specific foe. Likewise, these measures should also show that a follow-on attack (i.e., frequency) reinforces and sustains the narrative. Specifically, patterns of discourse in congressional and editorial commentary will typically show extensive references to existential danger and the need to get active, and they will link present severe events to those in the past, especially at the narrative founding. Secondary sources and polls will show the same pattern. 52

On the other hand, if severity and frequency are low in a given period—owing to the defeat of an ideological rival (i.e., positive event) or scarcity of direct/indirect attacks (i.e., absence of negative events) by a rival for at least two or three years—there should be less discussion in editorials and the Congressional Record about an ideological foe compared with periods marked by narrative robustness. Likewise, talk of existential danger, blame, and the lesson to protect liberal order abroad should be substantially less than in periods of a robust liberal narrative. Polls and scholarly or pundit assessments in secondary sources will validate this outcome.

Finally, using a singular type of congruence test, I explore narrative discourses and their impact (if any) on decisions to continue, expand, or end war. If the strategic-narrative argument is correct, assessments by pundits, memoirs, and the like should show how narrative-based discourses affected policy decisions in predicted ways. When the liberal discourse is robust, various actors (especially leaders) should talk about the domestic pressure to continue military action or the domestic costs of withdrawal. But when the discourse is weak, they should talk about domestic costs to maintain military action or political space to retrench from conflicts abroad. 53

The September 11 terrorist attacks dramatically reversed the weak liberal narrative environment of the early post–Cold War period. 54 “This week's frontal assault on America is a collective trauma unlike any other in any of our lifetimes,” observed the San Francisco Chronicle . 55 “A new narrative literally fell from the sky on September 11” and “became embedded in the popular imagination,” noted a pair of scholars. 56 Almost everyone became a promoter. As anticipated when external trauma arises from a direct attack, the story immediately saturated the public discourse—print media, television, members of Congress, and eventually in statements by President George W. Bush. The story included all standard parts of a national security narrative: detailing events existentially, assigning blame, and setting a way forward to repair (i.e., lesson). Members of Congress repeatedly framed events in existential terms, as an attack on “our laws, our cherished beliefs.” 57 “This is war,” declared House Majority Leader Dick Gephardt (D-MO), just after the attack. 58 Newspapers across the country echoed the same themes, as did polls in late September: 58 percent of Americans wanted “a long-term war”; 73 percent supported ground troops to “combat international terrorism.” 59

In the years that followed, the frequency of severe attacks remained high and reinforced the liberal narrative. Targets included, to name a few, Kuwait (2002), Bali (2002, 2005), Mombasa (2002), Riyadh (2003), Casablanca (2003), Istanbul (2003), Madrid (2004), London (2005), Algiers (2007), and countless bombings in Iraq and Afghanistan starting in 2004. 60 These events (especially against liberal or liberalizing allies in Europe and Iraq) sparked fervent national discussions in the United States.

Most specifically, the salience of promoter narratives about existential danger, parallels to 9/11, and the lesson to fight terrorism increased dramatically. Bush framed the 2005 London terrorist attack as an assault on “human liberty.” 61 Of Madrid, Secretary of State Colin Powell said that the bombing should “redouble everyone's efforts” to go after terrorists. 62 As anticipated by trauma theory, every congressional statement in the two weeks after the Madrid and London attacks described them in existential terms, which both reflected and revalidated the robust liberal narrative. “Americans were shocked and dismayed … when terror struck the capital of the United Kingdom, the cradle of Western liberty,” one said of London. 63 “The free nations of the world will … ensure that those who hate freedom and liberty will not succeed,” said another of Madrid. 64 Likewise, no one framed these as isolated, disconnected events, but instead linked them together as “reminders” and, with that, extensions of September 11 and the anti-terrorism narrative. Many talked of how Americans did and should look “through the prism” of September 11 to make sense of Bali, Madrid, London, Istanbul, and the like. “No American will ever forget the infamous day of 9/11,” a member of Congress said of Madrid. 65 Finally, promoters stressed that these events supported the lesson to press on in the fight against terrorism. It was like a drumbeat from political leaders: “stand firm against terrorism”; “renew our determination to eradicate terrorism”; “dismantle the al Qaeda network”; “remain defiant in the face of terrorism.” 66

Like the days after 9/11, promoter appeals resonated and echoed nationally, pointing to the continued strength and vitality of the anti-terrorism narrative into the late 2000s. This was evident in two ways. First, it showed up in newspapers across the country, from big cities to small towns. Content analysis of seventy-two editorials in the ten days after the Madrid bombings found that 54 percent of the papers described the attacks in existential terms related to democracy, liberty, freedom, or civilization; 64 percent drew parallels between the bombing and other recent terrorist attacks, especially 9/11; and 70 percent referenced the central lesson of the narrative to actively stamp out terrorism abroad. The same was the case with editorials following the London bombings: 63 percent were existential; 71 percent were connected to 9/11 or other terrorist attacks; and 73 percent referenced the lesson to remain or become more active abroad to fight terrorism. 67

Take a Wall Street Journal editorial, for instance, about Madrid. “So much for the illusion that the global war on terror isn't really a war,” noted the editors, “That complacent notion which has been infiltrating its way into the American public mind, blew up along with 10 bombs on trains carrying Spanish commuters yesterday.” The editors then listed eleven other attacks—including September 11—to draw attention to the existential danger that “terrorism remains the single largest threat to Western freedom and security.” 68 Headlines around the Madrid, London, and Bali bombings were similar: “This Week, ‘Madrid Became Manhattan’”; “Ground Zero, Madrid”; “Terror in London: A Reminder to the World that War of 9/11 Is Not Over.” 69 A total of 56 percent of Americans agreed that the London attacks showed that “it is necessary to fight the war against the terrorists in Iraq and everywhere else.” 70

A second indicator of narrative strength was the extent to which both Democrats and Republicans used the narrative as a political battering ram by the late 2000s. The Bush White House had long painted political opponents as weak on terrorism to win votes. 71 By 2006, with al-Qaeda gaining new ground in Iraq (where the United States was deeply invested in trying to build a liberal democratic government), Republicans doubled down on this message, saying that Democratic proposals for withdrawal from Iraq would aid terrorists. “If we were to follow the proposals of Democratic leaders,” said one Republican (GOP) House member in a 2007 debate on a resolution opposing the Iraq troop surge, “anarchy in Iraq would give al Qaeda and other extremists a haven to train and plot attacks.” 72 Thirty-nine other Republicans (73 percent of GOP speakers) echoed the same that day. Many senior Democrats also used the anti-terrorism narrative as a counterpunch. “Fighting terrorism, fighting extremism … is weakened by our being in Iraq,” said Representative Barney Frank (D-MA); “it has emboldened radicals everywhere.” 73 Others noted similarly how Bush “distracted us from the real war on terror” and “weakened our fight against al Qaeda.” 74

Afghanistan played a big part in these Democratic counterpunches around terrorism, especially after a 2007 National Intelligence Estimate showed that the Taliban/al-Qaeda had made significant gains there. Democratic calls to “refocus” the war on terrorism invariably meant moving attention to Afghanistan. 75 Senator and presidential candidate Barack Obama (D-IL) led the way. 76 “We must get off the wrong battlefield,” Obama charged in an August 2007 speech, before committing to send two additional divisions to Afghanistan. 77 The speech was intentional, meant to counter charges from Senator Hillary Clinton (D-NY) in a July presidential primary debate that Obama was weak on foreign policy. Cognizant of how Bush successfully painted rival presidential candidate John Kerry as “weak” on terrorism in 2004, political strategist David Axelrod hatched the idea of the August speech. 78 “Outflanking Bush-Cheney with a serious, aggressive, intelligent campaign against Islamist terror?” said a pair of observers, “It's what the country wants. And it seems to be what Obama is offering.” 79

Overall, Obama's August 2007 move reflected the strength of the liberal narrative around terrorism in the late 2000s. It also fueled a narrative-based discourse that constrained Obama throughout his presidency.

obama's first troop surge

When President Obama took office in 2009, a request for additional troops for Afghanistan was on his desk. 80 Obama initially hesitated. “I have campaigned on providing Afghanistan more troops,” he said in a January 23 National Security Council (NSC) meeting, “but I haven't made the decision yet.” Supported by Vice President Joe Biden and other civilian moderators in the White House, Obama expressed doubts about escalation, blocked a move by military leaders to add troops without his approval, and commissioned former NSC staffer Bruce Riedel to conduct a review of Afghan policy, after which Obama would decide on troops. 81

Moderators failed, however. Animated by the cascade of narrative-validating terror attacks, a surging liberal discourse prevented Obama from maintaining this wait and see approach, pushing him to approve 17,000 more troops for Afghanistan in mid-February 2009, well before the completed review. Combined with the president's campaign pledges, public support for the troop request by promoters—like Michael Mullen, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff—ignited an expansive national discussion for more action. In editorials, 70 percent supported more troops, 85 percent discussed combating terrorism (i.e., the narrative's lesson), and 40 percent mentioned Obama's campaign pledges. 82 The Washington Post criticized Obama for waffling on his campaign promises: “The war on terrorism did not end on January 20 [Obama's Inauguration Day].” 83 Polls showed that 70 percent of respondents expected Afghanistan to fall under “the control of terrorists” if the United States left; 63 percent favored more troops. 84 Deputy National Security Advisor for Strategic Communications Ben Rhodes bemoaned the “political drama” and the fact that “the media started calling Afghanistan ‘Obama's War.’” 85 The White House saw costs of inaction rising.

Promoters inside the administration elevated these costs too. In the January 23 NSC meeting, General David Petraeus, commander of U.S. Central Command, said that failure was coming in Afghanistan and that al-Qaeda would gain ground: “we cannot achieve our objective without more troops.” Mullen echoed the same. 86 Obama knew the political risks. Just ten days prior, Senator Graham had warned Obama that Republicans would use failure in Afghanistan in the 2010 midterms. During a February 13 meeting, advisers gave Obama two options: wait on Riedel's report or add 17,000 troops. Promoters (including Secretary of State Hillary Clinton) harped on narrative themes: a “bloodbath” for al-Qaeda without more troops. 87 The domestic fallout of that happening was simply too high. “For practical and political purposes there really was no choice [italics added],” observed Bob Woodward. 88 Four days later, Obama publicly justified more troops as being vital to counterterrorism; 63 percent of the electorate approved. 89 Like Woodward, the New York Times concluded that Obama “had no choice” given what he said “during the campaign.” In short, Obama's opportunistic use of the anti-terrorism narrative during the 2008 presidential campaign fueled a robust liberal discourse and high audience costs of inaction that forced his hand in February 2009. 90

obama and the second troop surge

In June 2009, National Security Advisor James Logan Jones Jr. told General Stanley McChrystal, the head of military operations in Afghanistan, that the president wanted to “reduce U.S. involvement” and shift to an aid-based strategy. 91 Eight weeks later, McChrystal requested an additional 40,000 troops as part of a report assessing the situation in Afghanistan. When Secretary of Defense Robert Gates informed the president, “the room exploded” in opposition. 92 Moderators in the White House warned Obama that he had pledged to end the Middle East wars. 93 “I shared Joe's [Biden] skepticism,” Obama said as he pushed back against more troops. There “are no good options,” he noted in a September 12 NSC meeting. 94

In the end, moderators lost again. As in February, the president capitulated to the anti-terrorism narrative pressure. In early September 2009, promoters generated a robust liberal discourse for more troops, arguing that failure risked another September 11. Frustrated by Obama's hesitancy, military leaders—namely, Petraeus, Mullen, and McChrystal—played a critical role by going public to use the robust anti-terrorism narrative to their advantage (which augmented their position in policy debates, as the strategic-narrative argument expects). The move was calculated. In a late August meeting on handling White House resistance to more troops, Senator Graham (while on air force reserve duty in Afghanistan) told Petraeus and McChrystal that their messaging focused too much on the Taliban. “America is worried all about al Qaeda attacking,” he counseled, “Americans understand that the Taliban are bad guys, but what drives the American psyche more than anything else is, are we about to let the country that attacked us once attack us twice?” 95 In short, Graham counseled the generals to use the anti-terrorism narrative to their political advantage.

The generals complied, now focusing their message on al-Qaeda, new attacks, and the potential for “failure” without more troops. 96 Petraeus warned publicly that the Afghan government would collapse without a fully resourced counterinsurgency. 97 On September 15 (just three days after Obama's “no good options” comment), Mullen told Congress that success in Afghanistan required more troops. A few days later, the Washington Post reported on a leaked copy of the McChrystal report in a front-page article titled “McChrystal: More Forces or ‘Mission Failure.’” The sixty-six-page report mentioned “failure” or “defeat” fourteen times. 98 Finally, McChrystal said publicly that he rarely spoke directly with Obama and that another September 11 would come without additional resolve. 99 Obama looked weak and out of touch.

As expected, these moves fueled a powerful liberal discourse across the country for more troops in Afghanistan. From mid-September to mid-October, 71 percent of statements on Capitol Hill about Afghanistan mentioned comments by the generals, and 88 percent of supporters of more force warned of another September 11: “Afghanistan is where the attacks of 9/11 originated” and “the sacrifices we make overseas now will prevent another 9/11-style attack here at home.” 100 Promoters in Congress attacked Obama's hesitancy to uphold his March pledge to “disrupt, dismantle and defeat al Qaeda” following Riedel's review. 101 “Soft-peddling … in Afghanistan,” said one; Obama's “latest verbal wavering aided terrorists,” said another. 102