- Words with Friends Cheat

- Wordle Solver

- Word Unscrambler

- Scrabble Dictionary

- Anagram Solver

- Wordscapes Answers

Make Our Dictionary Yours

Sign up for our weekly newsletters and get:

- Grammar and writing tips

- Fun language articles

- #WordOfTheDay and quizzes

By signing in, you agree to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy .

We'll see you in your inbox soon.

What Is a Claim in Writing? Examples of Argumentative Statements

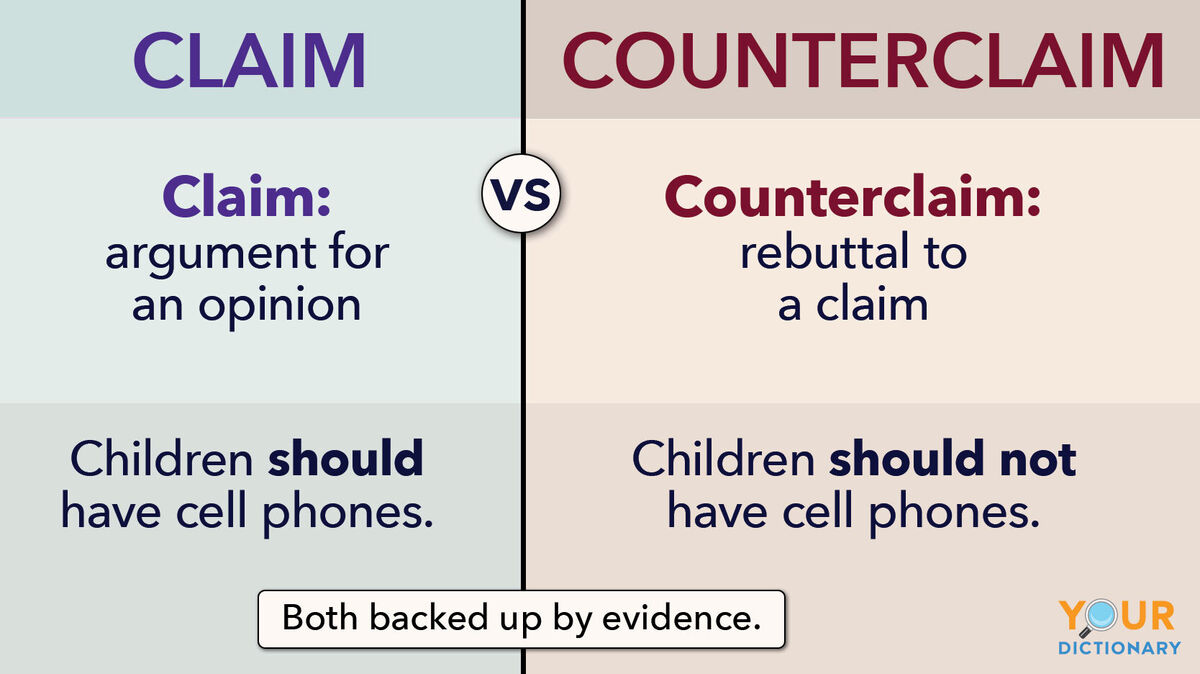

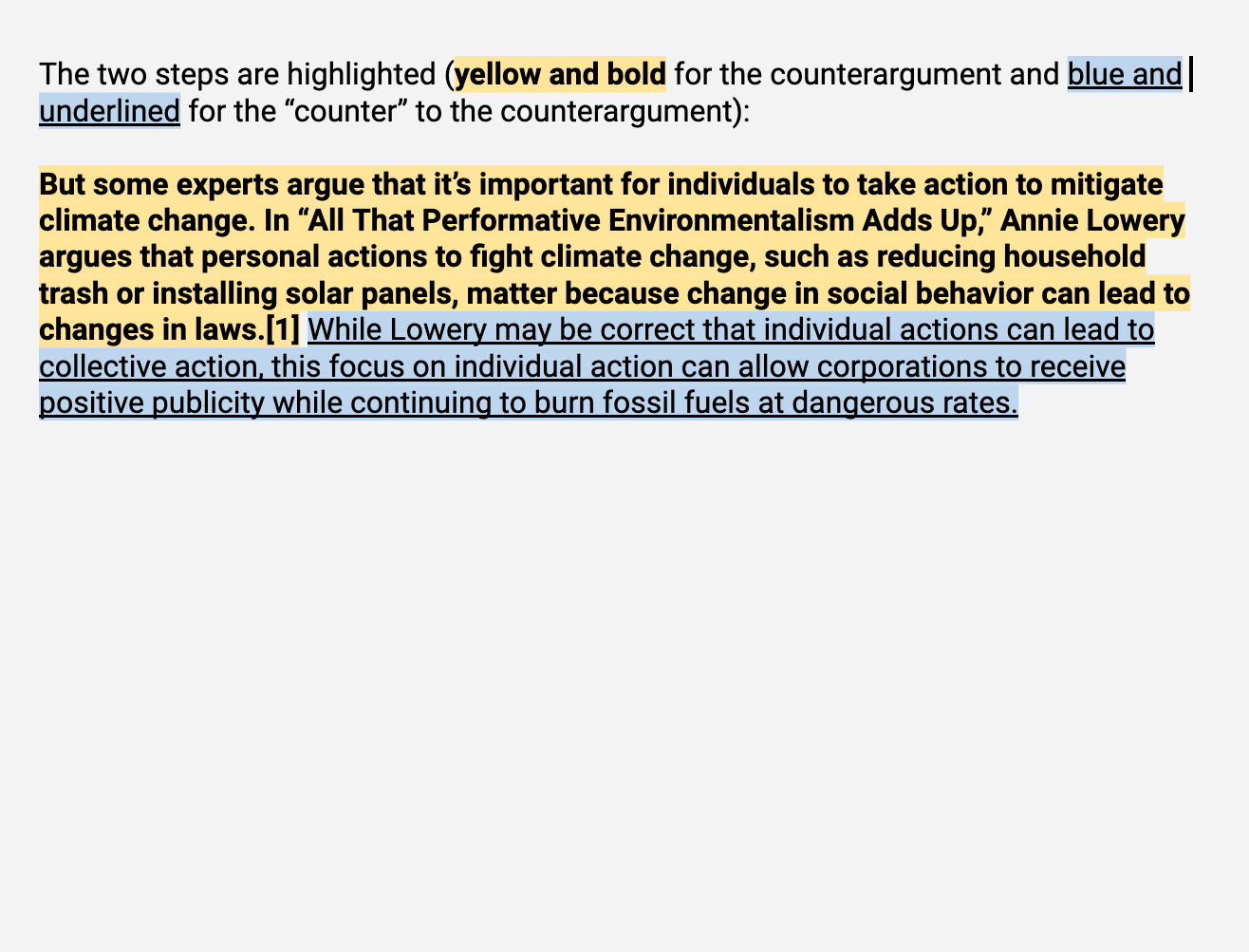

- DESCRIPTION argumentative statements of claim and counterclaim examples

- SOURCE Created by Lindy Gaskill for YourDictionary

- PERMISSION Copyright YourDictionary, Owned by YourDictionary

Are you wondering, "What is a claim in writing?" When you make an argument in writing and back it up with supporting evidence, you are making a claim. Claims are very common in research papers and certain types of essays.

Making Claims in Writing

Making a claim in your writing allows you to present the main idea of the document in the form of an argument that you will support with evidence throughout the document. A claim statement is a type of thesis statement in which you present the main idea of what you are writing in the form of an argument. Think of claims like a thesis statement in the form of an argument.

- Claims are matters of opinion, but they are stated as if they are facts and backed up with evidence.

- Any time you make a debatable statement in writing that is backed up with facts and/or other types of evidence, you are using a claim.

Statement vs. Claim Example

Argumentative claims don't have to be complex, but they do have to be more than just a fact-based statement that is obviously true. Instead, claims should be statements that are up for debate. As a writer, your goal is to effectively argue in favor of your claim. Review the examples below to develop a better understanding of what is a claim in an essay.

- statement - If you open an essay by stating, "I own a cell phone," this is not an example of a claim in writing. Assuming that you do, in fact, own a cell phone, this is just a statement of fact. It is not something that is arguable.

- claim - If you open by stating, "Every middle school student should have their own cell phone," this is a claim. This is not something that everyone agrees upon. Your paper will need to focus on supporting this claim with evidence.

Types of Writing That Use Claims

Claims are common in different types of writing, including documents created for school assignments or in the professional world.

- argumentative essays - These essays focus on an issue that is controversial, presenting evidence that backs up the writer's claim.

- research papers - Academic research papers are designed specifically to provide evidence to confirm or refute the writer's hypothesis , which is a type of claim.

- literary analysis - When engaged in literary analysis, writers make a claim about a literary work, then provide evidence from it to support their claim.

- persuasive essays - Persuasive essays are a type of argumentative essay. They use fact-based information as evidence to back up a writer's claim.

- persuasive speeches - Persuasive speeches are presented orally, but many start with an outline focused on providing evidence for a primary claim.

- persuasive memos - Persuasive memos are often designed to convince readers to believe or act on a claim backed up by evidence.

What Is Evidence in Writing?

In order to back up a claim in writing, you will need to provide evidence. Evidence is information that provides proof of or support for an idea. Your claim statement should be a logical conclusion that you reached as a result of reviewing and understanding valid, reliable evidence. Rather than expecting readers to simply believe that your claim is true, you'll need to provide them with evidence they can consider to reach their own conclusion.

There are many types of evidence:

- direct observation of a phenomenon or occurrence

- primary research, such as an experiment or content analysis

- synthesis of secondary research, such as a literature review

- information gathered from investigative interviews

- facts, statistics or other data

- expert opinions

- examples of past behavior

It's important to be aware that the fact you can find evidence in favor of your claim does not necessarily mean that your claim is a factual statement. There is also just as much evidence against a claim as there is evidence for them. The idea of making a claim in writing is to present a logical, fact-based argument for the claim that you are making.

Argumentative Claim Examples

Review a few examples of argumentative claims to help clarify what is a claim in writing. These examples can help you identify claims when reading works of writing, as well as provide you with inspiration when you need to write a claim statement.

- College students today should focus on learning skills that will qualify them to work effectively in a virtual environment.

- School uniforms help promote an inclusive educational environment for all students, regardless of socioeconomic status.

- In light of the severity of recent hurricanes, living near the coast is becoming increasingly hazardous.

- Yoga provides both physical and mental health benefits.

- Concrete is the best building material for residential structures.

- Children under the age of 12 should not be allowed to have social media profiles.

- Spending more than an hour per day on housework is a waste of time.

- People who get at least 10,000 steps per day are healthier than those who don't.

- Eating too many carbohydrates is the primary reason some people are overweight.

- Dining in restaurants is actually more economical for individuals or couples than cooking at home.

Note that the statements above are not commonly accepted facts. You may agree with some of these, but chances are that you don't agree with all of them. Each example above is a matter of opinion. If you write about any of these, you will need to back up with evidence in an effort to prove your point. Readers will decide whether or not they agree with your argument base on how effectively you make your point, as well as their own knowledge and/or opinion about the topic.

What to Include in a Claim Paragraph

An argumentative claim will generally appear in the first paragraph of a document. The claim statement is usually paired with a hook to form the introductory paragraph of an essay or other document. The hook is designed to capture reader interest so they will want to learn more, while the claim statement lets them know what point will be argued in the paper.

What Is a Counterclaim in Writing?

When someone presents an alternative argument to your claim, that is a counterclaim. Another word for a counterclaim is a rebuttal. When someone presents a counterclaim, they are making a claim of their own. It will be up to them to state their counterclaim, then seek to back it up with evidence (just as you did when making the initial claim).

- claim - making an argument and backing it up with evidence

- counterclaim - presenting a rebuttal to a claim and backing it up with evidence

Debates involve claims (arguments) and counterclaims (rebuttals). When people participate in a debate, they prepare arguments for their claims and deliver strong rebuttals to the claims of their opponents.

Explore Argumentation and Debate

Now that you know what a claim is in writing, consider taking a deeper dive into how this communication strategy can be used in writing and face-to-face communication. Start by exploring key ways the terms argument and debate differ . From there, investigate how examples of rhetoric can be used as a tool to persuade and motivate.

What Is a Claim in an Essay? Read This Before Writing

What is a claim in an essay?

In this article, you’ll find the essay claim definition, characteristics, types, and examples. Let’s learn where to use claims and how to write them.

Get ready for up-to-date and practical information only!

What Is a Claim in Writing?

A claim is the core argument defining an essay’s goal and direction. (1) It’s assertive, debatable, and supported by evidence. Also, it is complex, specific, and detailed.

Also known as a thesis, a claim is a little different from statements and opinions. Keep reading to reveal the nuances.

Claims vs. statements vs. opinions

Where to use claims.

To answer the “What is claim in writing?”, it’s critical to understand that this definition isn’t only for high school or college essays. Below are the types of writing with claims:

- Argumentative articles. Consider a controversial issue, proving it with evidence throughout your paper.

- Literary analysis. Build a claim about a book , and use evidence from it to support your claim.

- Research papers. Present a hypothesis and provide evidence to confirm or refute it.

- Speeches. State a claim and persuade the audience that you’re right.

- Persuasive essays and memos. State a thesis and use fact-based evidence to back it up..

What can you use as evidence in essays?

- Facts and other data from relevant and respectful resources (no Wikipedia or other sources like this)

- Primary research

- Secondary research (science magazines’ articles, literature reviews, etc.)

- Personal observation

- Expert quotes (opinions)

- Info from expert interviews

How to Write a Claim in Essays

Two points to consider when making a claim in a college paper:

First, remember that a claim may have counterarguments. You’ll need to respond to them to make your argument stronger. Use transition words like “despite,” “yet,” “although,” and others to show those counterclaims.

Second, good claims are more complex than simple “I’m right” statements. Be ready to explain your claim, answering the “So what?” question.

And now, to details:

Types of claims in an essay (2)

Writing a claim: details to consider.

What makes a good claim? Three characteristics (3):

- It’s assertive. (You have a strong position about a topic.)

- It’s specific. (Your assertion is as precise as possible.)

- It’s provable. (You can prove your position with evidence.)

When writing a claim, avoid generalizations, questions, and cliches. Also, don’t state the obvious.

- Poor claim: Pollution is bad for the environment.

- Good claim: At least 25% of the federal budget should be spent upgrading businesses to clean technologies and researching renewable energy sources to control or cut pollution.

How to start a claim in an essay?

Answer the essay prompt. Use an active voice when writing a claim for readers to understand your point. Here is the basic formula:

When writing, avoid:

- First-person statements

- Emotional appeal

- Cluttering your claim with several ideas; focus on one instead

How long should a claim be in an essay?

1-2 sentences. A claim is your essay’s thesis: Write it in the first paragraph (intro), presenting a topic and your position about it.

Examples of Claims

Below are a few claim examples depending on the type. I asked our expert writers to provide some for you to better understand how to write it.

Feel free to use them for inspiration, or don’t hesitate to “steal” if they appear relevant to your essay topic. Also, remember that you can always ask our writers to assist with a claim for your papers.

Final Words

Now that you know what is a claim in an essay, I hope you don’t find it super challenging to write anymore. It’s like writing a thesis statement; make it assertive, specific, and provable.

If you still have questions or doubts, ask Writing-Help writers for support. They’ll help you build an A-worthy claim for an essay.

References:

- https://www.pvcc.edu/files/making_a_claim.pdf

- https://lsa.umich.edu/content/dam/sweetland-assets/sweetland-documents/teachingresources/TeachingArgumentation/Supplement2_%20SixCommonTypesofClaim.pdf

- https://students.tippie.uiowa.edu/sites/students.tippie.uiowa.edu/files/2022-05/effective_claims.pdf

- Essay samples

- Essay writing

- Writing tips

Recent Posts

- Writing the “Why Should Abortion Be Made Legal” Essay: Sample and Tips

- 3 Examples of Enduring Issue Essays to Write Yours Like a Pro

- Writing Essay on Friendship: 3 Samples to Get Inspired

- How to Structure a Leadership Essay (Samples to Consider)

- What Is Nursing Essay, and How to Write It Like a Pro

What this handout is about

This handout will define what an argument is and explain why you need one in most of your academic essays.

Arguments are everywhere

You may be surprised to hear that the word “argument” does not have to be written anywhere in your assignment for it to be an important part of your task. In fact, making an argument—expressing a point of view on a subject and supporting it with evidence—is often the aim of academic writing. Your instructors may assume that you know this and thus may not explain the importance of arguments in class.

Most material you learn in college is or has been debated by someone, somewhere, at some time. Even when the material you read or hear is presented as a simple fact, it may actually be one person’s interpretation of a set of information. Instructors may call on you to examine that interpretation and defend it, refute it, or offer some new view of your own. In writing assignments, you will almost always need to do more than just summarize information that you have gathered or regurgitate facts that have been discussed in class. You will need to develop a point of view on or interpretation of that material and provide evidence for your position.

Consider an example. For nearly 2000 years, educated people in many Western cultures believed that bloodletting—deliberately causing a sick person to lose blood—was the most effective treatment for a variety of illnesses. The claim that bloodletting is beneficial to human health was not widely questioned until the 1800s, and some physicians continued to recommend bloodletting as late as the 1920s. Medical practices have now changed because some people began to doubt the effectiveness of bloodletting; these people argued against it and provided convincing evidence. Human knowledge grows out of such differences of opinion, and scholars like your instructors spend their lives engaged in debate over what claims may be counted as accurate in their fields. In their courses, they want you to engage in similar kinds of critical thinking and debate.

Argumentation is not just what your instructors do. We all use argumentation on a daily basis, and you probably already have some skill at crafting an argument. The more you improve your skills in this area, the better you will be at thinking critically, reasoning, making choices, and weighing evidence.

Making a claim

What is an argument? In academic writing, an argument is usually a main idea, often called a “claim” or “thesis statement,” backed up with evidence that supports the idea. In the majority of college papers, you will need to make some sort of claim and use evidence to support it, and your ability to do this well will separate your papers from those of students who see assignments as mere accumulations of fact and detail. In other words, gone are the happy days of being given a “topic” about which you can write anything. It is time to stake out a position and prove why it is a good position for a thinking person to hold. See our handout on thesis statements .

Claims can be as simple as “Protons are positively charged and electrons are negatively charged,” with evidence such as, “In this experiment, protons and electrons acted in such and such a way.” Claims can also be as complex as “Genre is the most important element to the contract of expectations between filmmaker and audience,” using reasoning and evidence such as, “defying genre expectations can create a complete apocalypse of story form and content, leaving us stranded in a sort of genre-less abyss.” In either case, the rest of your paper will detail the reasoning and evidence that have led you to believe that your position is best.

When beginning to write a paper, ask yourself, “What is my point?” For example, the point of this handout is to help you become a better writer, and we are arguing that an important step in the process of writing effective arguments is understanding the concept of argumentation. If your papers do not have a main point, they cannot be arguing for anything. Asking yourself what your point is can help you avoid a mere “information dump.” Consider this: your instructors probably know a lot more than you do about your subject matter. Why, then, would you want to provide them with material they already know? Instructors are usually looking for two things:

- Proof that you understand the material

- A demonstration of your ability to use or apply the material in ways that go beyond what you have read or heard.

This second part can be done in many ways: you can critique the material, apply it to something else, or even just explain it in a different way. In order to succeed at this second step, though, you must have a particular point to argue.

Arguments in academic writing are usually complex and take time to develop. Your argument will need to be more than a simple or obvious statement such as “Frank Lloyd Wright was a great architect.” Such a statement might capture your initial impressions of Wright as you have studied him in class; however, you need to look deeper and express specifically what caused that “greatness.” Your instructor will probably expect something more complicated, such as “Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture combines elements of European modernism, Asian aesthetic form, and locally found materials to create a unique new style,” or “There are many strong similarities between Wright’s building designs and those of his mother, which suggests that he may have borrowed some of her ideas.” To develop your argument, you would then define your terms and prove your claim with evidence from Wright’s drawings and buildings and those of the other architects you mentioned.

Do not stop with having a point. You have to back up your point with evidence. The strength of your evidence, and your use of it, can make or break your argument. See our handout on evidence . You already have the natural inclination for this type of thinking, if not in an academic setting. Think about how you talked your parents into letting you borrow the family car. Did you present them with lots of instances of your past trustworthiness? Did you make them feel guilty because your friends’ parents all let them drive? Did you whine until they just wanted you to shut up? Did you look up statistics on teen driving and use them to show how you didn’t fit the dangerous-driver profile? These are all types of argumentation, and they exist in academia in similar forms.

Every field has slightly different requirements for acceptable evidence, so familiarize yourself with some arguments from within that field instead of just applying whatever evidence you like best. Pay attention to your textbooks and your instructor’s lectures. What types of argument and evidence are they using? The type of evidence that sways an English instructor may not work to convince a sociology instructor. Find out what counts as proof that something is true in that field. Is it statistics, a logical development of points, something from the object being discussed (art work, text, culture, or atom), the way something works, or some combination of more than one of these things?

Be consistent with your evidence. Unlike negotiating for the use of your parents’ car, a college paper is not the place for an all-out blitz of every type of argument. You can often use more than one type of evidence within a paper, but make sure that within each section you are providing the reader with evidence appropriate to each claim. So, if you start a paragraph or section with a statement like “Putting the student seating area closer to the basketball court will raise player performance,” do not follow with your evidence on how much more money the university could raise by letting more students go to games for free. Information about how fan support raises player morale, which then results in better play, would be a better follow-up. Your next section could offer clear reasons why undergraduates have as much or more right to attend an undergraduate event as wealthy alumni—but this information would not go in the same section as the fan support stuff. You cannot convince a confused person, so keep things tidy and ordered.

Counterargument

One way to strengthen your argument and show that you have a deep understanding of the issue you are discussing is to anticipate and address counterarguments or objections. By considering what someone who disagrees with your position might have to say about your argument, you show that you have thought things through, and you dispose of some of the reasons your audience might have for not accepting your argument. Recall our discussion of student seating in the Dean Dome. To make the most effective argument possible, you should consider not only what students would say about seating but also what alumni who have paid a lot to get good seats might say.

You can generate counterarguments by asking yourself how someone who disagrees with you might respond to each of the points you’ve made or your position as a whole. If you can’t immediately imagine another position, here are some strategies to try:

- Do some research. It may seem to you that no one could possibly disagree with the position you are arguing, but someone probably has. For example, some people argue that a hotdog is a sandwich. If you are making an argument concerning, for example, the characteristics of an exceptional sandwich, you might want to see what some of these people have to say.

- Talk with a friend or with your teacher. Another person may be able to imagine counterarguments that haven’t occurred to you.

- Consider your conclusion or claim and the premises of your argument and imagine someone who denies each of them. For example, if you argued, “Cats make the best pets. This is because they are clean and independent,” you might imagine someone saying, “Cats do not make the best pets. They are dirty and needy.”

Once you have thought up some counterarguments, consider how you will respond to them—will you concede that your opponent has a point but explain why your audience should nonetheless accept your argument? Will you reject the counterargument and explain why it is mistaken? Either way, you will want to leave your reader with a sense that your argument is stronger than opposing arguments.

When you are summarizing opposing arguments, be charitable. Present each argument fairly and objectively, rather than trying to make it look foolish. You want to show that you have considered the many sides of the issue. If you simply attack or caricature your opponent (also referred to as presenting a “straw man”), you suggest that your argument is only capable of defeating an extremely weak adversary, which may undermine your argument rather than enhance it.

It is usually better to consider one or two serious counterarguments in some depth, rather than to give a long but superficial list of many different counterarguments and replies.

Be sure that your reply is consistent with your original argument. If considering a counterargument changes your position, you will need to go back and revise your original argument accordingly.

Audience is a very important consideration in argument. Take a look at our handout on audience . A lifetime of dealing with your family members has helped you figure out which arguments work best to persuade each of them. Maybe whining works with one parent, but the other will only accept cold, hard statistics. Your kid brother may listen only to the sound of money in his palm. It’s usually wise to think of your audience in an academic setting as someone who is perfectly smart but who doesn’t necessarily agree with you. You are not just expressing your opinion in an argument (“It’s true because I said so”), and in most cases your audience will know something about the subject at hand—so you will need sturdy proof. At the same time, do not think of your audience as capable of reading your mind. You have to come out and state both your claim and your evidence clearly. Do not assume that because the instructor knows the material, he or she understands what part of it you are using, what you think about it, and why you have taken the position you’ve chosen.

Critical reading

Critical reading is a big part of understanding argument. Although some of the material you read will be very persuasive, do not fall under the spell of the printed word as authority. Very few of your instructors think of the texts they assign as the last word on the subject. Remember that the author of every text has an agenda, something that he or she wants you to believe. This is OK—everything is written from someone’s perspective—but it’s a good thing to be aware of. For more information on objectivity and bias and on reading sources carefully, read our handouts on evaluating print sources and reading to write .

Take notes either in the margins of your source (if you are using a photocopy or your own book) or on a separate sheet as you read. Put away that highlighter! Simply highlighting a text is good for memorizing the main ideas in that text—it does not encourage critical reading. Part of your goal as a reader should be to put the author’s ideas in your own words. Then you can stop thinking of these ideas as facts and start thinking of them as arguments.

When you read, ask yourself questions like “What is the author trying to prove?” and “What is the author assuming I will agree with?” Do you agree with the author? Does the author adequately defend her argument? What kind of proof does she use? Is there something she leaves out that you would put in? Does putting it in hurt her argument? As you get used to reading critically, you will start to see the sometimes hidden agendas of other writers, and you can use this skill to improve your own ability to craft effective arguments.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Booth, Wayne C., Gregory G. Colomb, Joseph M. Williams, Joseph Bizup, and William T. FitzGerald. 2016. The Craft of Research , 4th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ede, Lisa. 2004. Work in Progress: A Guide to Academic Writing and Revising , 6th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Gage, John T. 2005. The Shape of Reason: Argumentative Writing in College , 4th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and John J. Ruszkiewicz. 2016. Everything’s an Argument , 7th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Rosen, Leonard J., and Laurence Behrens. 2003. The Allyn & Bacon Handbook , 5th ed. New York: Longman.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Customer Reviews

- Extended Essays

- IB Internal Assessment

- Theory of Knowledge

- Literature Review

- Dissertations

- Essay Writing

- Research Writing

- Assignment Help

- Capstone Projects

- College Application

- Online Class

How to Write a Claim for An Argumentative Essay Step-By-Step

by Antony W

October 24, 2022

Have you searched for a guide on how to write a claim for an argumentative essay but came out empty?

You’ve come to the right place.

Whether you’re looking forward to working on a difficult argumentative essay topic or you already have easy subject to work on, this guide will show you how to write a claim that you can defend using evidence and reason.

Key Takeaways

- A claim is a declaration sentence subject to debate.

- Claims are different from topic sentences in that they appear only in the thesis statement of the essay. A topic sentence appears in every paragraph of an essay.

- For a sentence to be a claim, it should communicate a message that engages an audience to do something or act in a certain way.

What is a Claim in an Argumentative Essay?

A claim in an essay is a debatable statement and a part of an argument’s declaration sentence. In respect to academic writing standards, a claim must exclude personal feelings and already known facts and it must leave room for debate.

Just as personal opinions are unacceptable in argumentative writing, a claim must not have a link to how you feel about a subject. Rather making a bold statement that potentially demonstrate that you’re right about an issue, you must bind your claim up for inquiry within the specific subject.

The purpose of a claim in an argument is to convince, persuade, or give proof to move your audience to agree with your point of view. You can focus on communicating a message, but it’s best to double down on moving an audience to think in a certain way.

Types of Claims in Argumentative Essay

A claim is one of the elements that drive an argument . For the best outcome, you need to use the right type of claim depending on the topic presented in the prompt.

You can make a:

- Claim of fact

- Claim of definition

- Claim of cause and effect

- Claim of value

- Claim of policy

Let’s look at each of these types of claims to help you understand what they mean.

Claim of Fact

How valid is the statement you’re about to give? Is there an element of truth in the statement you intend to present?

Should such be the statement you want to present, you’re looking at making a claim of fact.

A claim of fact mainly presents an argument that demonstrates whether something is true or false. It holds that if you’re going to challenge what we consider as facts, you must have concrete research to back it up.

Claim of Definition

A claim of definition argues about definitions of things or phenomena. Ideally, you may argue that something means another thing altogether, even if some people don’t consider your definition sounding.

Rather than offering a discount explanation of your claim, you shouldn’t hesitate to give your personal explanation. However, you must ensure that you sound neither emotional nor biased.

Pay attention to the information that you provide when dealing with a claim of definition. Remember that when writing an argumentative essay, even a claim of definition must be debatable.

Claim of Cause and Effect

The claim of cause and effect requires you to do two things:

First, you should describe the cause of an event. Second, you should explain the implication or impact the issue has.

By doing so, your essay will be so comprehensive and valuable that you earn top grades.

Claim of Value

If you’re going to base your argument on the significance of the topic in question, you will have to make a claim of value.

Claim of Policy

You can also make a claim of policy in your argumentative essay.

This type of claim seeks to give readers the reasons why they should care about what you have to say. It also should suggest what they should do after reading your essay.

How to Write a Claim for an Argumentative Essay

You’ve learned three important things so far. You know what claim is in an essay, why the claim is important, and the types of claims you can write in your argument.

But how do you write a claim for an argumentative essay?

1. Explore the Essay’s Topic

Exploring your focus topic is a good way to determine what claim can best fit in your argumentative essay.

Whether you’ve selected your own idea or received a focus topic from your teacher, you should do preliminary research and develop concrete ideas that you can easily argue.

Let’s say you’re working on a topic about global warning. Deforestation would make a good focus topic here. From this, you can present evidence and give reasons why cutting down trees is the major cause of global warming.

2. Ask a Question

Narrowing down to a specific subject has two benefits.

- It’s easy to come up with tons of useful ideas for your central argument.

- You can develop reasonable questions to help you develop a relevant claim for the essay.

The most relevant question for the project is one that summarizes your thoughts. For the claim to be bold, you must follow the question with a short, clear, and direct response to summarize your positon.

3. Determine the Goal of the Essay

Another way to come up with a strong claim for an argumentative essay is to look at the assignment brief once more to understand the primary goal of the argument .

Determining the goal of the assignment can help you to develop a claim that can easily challenge the opinion of your readers regardless of what they assume to be true.

From a writing standpoint, your essay will focus on multiple issues. However, you’ll need to ensure that they all tie together to address the central theme in the thesis statement. In this respect, your claim should demonstrate a clear stand on the main issue.

4. Take a Unique Approach

We’ve looked at hundreds of argumentative essay samples in the last few months. What we discovered is a similarity in the way students approach the assignment.

Either they state arguable facts followed by blunt claims.

There’s nothing with this. The problem, though, is that it becomes difficult to grab the attention of a reader.

So we recommend that you take a different approach. By doing so, you can write a claim that’s not only interesting but also sustainable.

Our team of professional writers and editor, who hold college and university degrees in various fields will research, write, and validate the information in the essay and deliver results that exceed your expectations.

About the author

Antony W is a professional writer and coach at Help for Assessment. He spends countless hours every day researching and writing great content filled with expert advice on how to write engaging essays, research papers, and assignments.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write an Argumentative Essay

4-minute read

- 30th April 2022

An argumentative essay is a structured, compelling piece of writing where an author clearly defines their stance on a specific topic. This is a very popular style of writing assigned to students at schools, colleges, and universities. Learn the steps to researching, structuring, and writing an effective argumentative essay below.

Requirements of an Argumentative Essay

To effectively achieve its purpose, an argumentative essay must contain:

● A concise thesis statement that introduces readers to the central argument of the essay

● A clear, logical, argument that engages readers

● Ample research and evidence that supports your argument

Approaches to Use in Your Argumentative Essay

1. classical.

● Clearly present the central argument.

● Outline your opinion.

● Provide enough evidence to support your theory.

2. Toulmin

● State your claim.

● Supply the evidence for your stance.

● Explain how these findings support the argument.

● Include and discuss any limitations of your belief.

3. Rogerian

● Explain the opposing stance of your argument.

● Discuss the problems with adopting this viewpoint.

● Offer your position on the matter.

● Provide reasons for why yours is the more beneficial stance.

● Include a potential compromise for the topic at hand.

Tips for Writing a Well-Written Argumentative Essay

● Introduce your topic in a bold, direct, and engaging manner to captivate your readers and encourage them to keep reading.

● Provide sufficient evidence to justify your argument and convince readers to adopt this point of view.

● Consider, include, and fairly present all sides of the topic.

● Structure your argument in a clear, logical manner that helps your readers to understand your thought process.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● Discuss any counterarguments that might be posed.

● Use persuasive writing that’s appropriate for your target audience and motivates them to agree with you.

Steps to Write an Argumentative Essay

Follow these basic steps to write a powerful and meaningful argumentative essay :

Step 1: Choose a topic that you’re passionate about

If you’ve already been given a topic to write about, pick a stance that resonates deeply with you. This will shine through in your writing, make the research process easier, and positively influence the outcome of your argument.

Step 2: Conduct ample research to prove the validity of your argument

To write an emotive argumentative essay , finding enough research to support your theory is a must. You’ll need solid evidence to convince readers to agree with your take on the matter. You’ll also need to logically organize the research so that it naturally convinces readers of your viewpoint and leaves no room for questioning.

Step 3: Follow a simple, easy-to-follow structure and compile your essay

A good structure to ensure a well-written and effective argumentative essay includes:

Introduction

● Introduce your topic.

● Offer background information on the claim.

● Discuss the evidence you’ll present to support your argument.

● State your thesis statement, a one-to-two sentence summary of your claim.

● This is the section where you’ll develop and expand on your argument.

● It should be split into three or four coherent paragraphs, with each one presenting its own idea.

● Start each paragraph with a topic sentence that indicates why readers should adopt your belief or stance.

● Include your research, statistics, citations, and other supporting evidence.

● Discuss opposing viewpoints and why they’re invalid.

● This part typically consists of one paragraph.

● Summarize your research and the findings that were presented.

● Emphasize your initial thesis statement.

● Persuade readers to agree with your stance.

We certainly hope that you feel inspired to use these tips when writing your next argumentative essay . And, if you’re currently elbow-deep in writing one, consider submitting a free sample to us once it’s completed. Our expert team of editors can help ensure that it’s concise, error-free, and effective!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

3-minute read

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

2-minute read

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

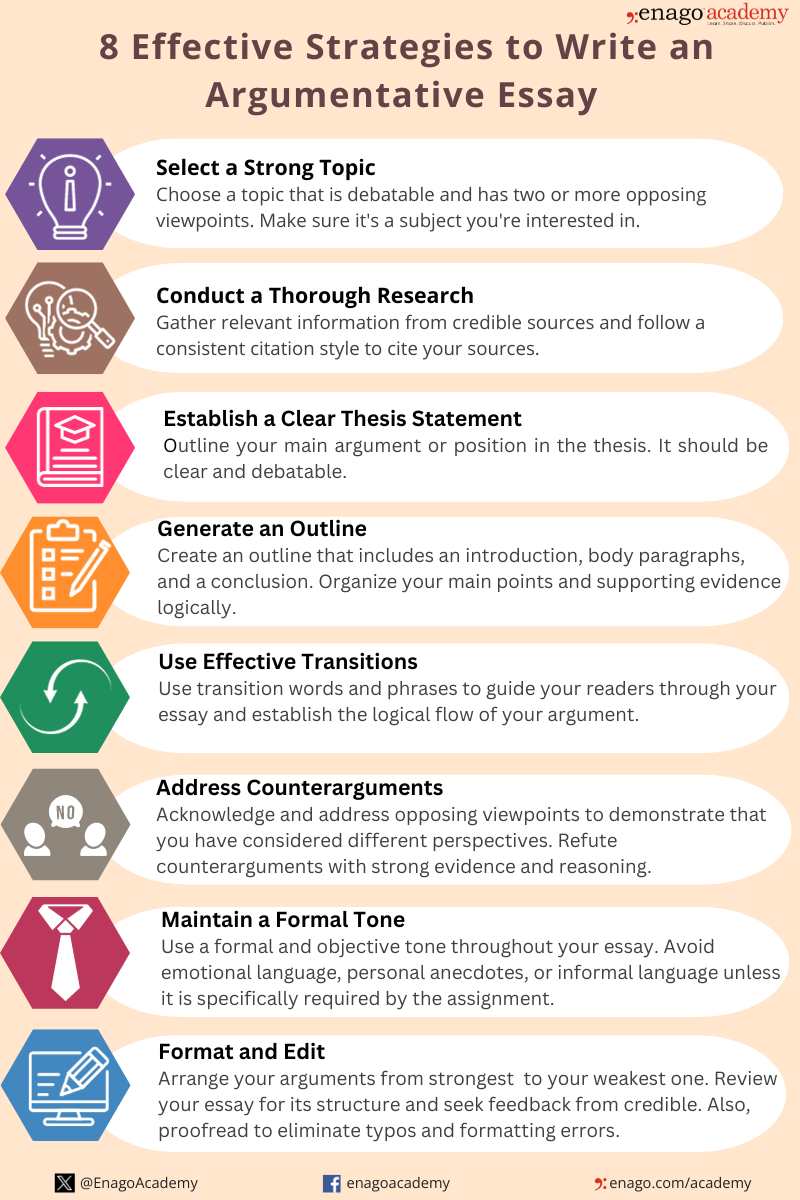

8 Effective Strategies to Write Argumentative Essays

In a bustling university town, there lived a student named Alex. Popular for creativity and wit, one challenge seemed insurmountable for Alex– the dreaded argumentative essay!

One gloomy afternoon, as the rain tapped against the window pane, Alex sat at his cluttered desk, staring at a blank document on the computer screen. The assignment loomed large: a 350-600-word argumentative essay on a topic of their choice . With a sigh, he decided to seek help of mentor, Professor Mitchell, who was known for his passion for writing.

Entering Professor Mitchell’s office was like stepping into a treasure of knowledge. Bookshelves lined every wall, faint aroma of old manuscripts in the air and sticky notes over the wall. Alex took a deep breath and knocked on his door.

“Ah, Alex,” Professor Mitchell greeted with a warm smile. “What brings you here today?”

Alex confessed his struggles with the argumentative essay. After hearing his concerns, Professor Mitchell said, “Ah, the argumentative essay! Don’t worry, Let’s take a look at it together.” As he guided Alex to the corner shelf, Alex asked,

Table of Contents

“What is an Argumentative Essay?”

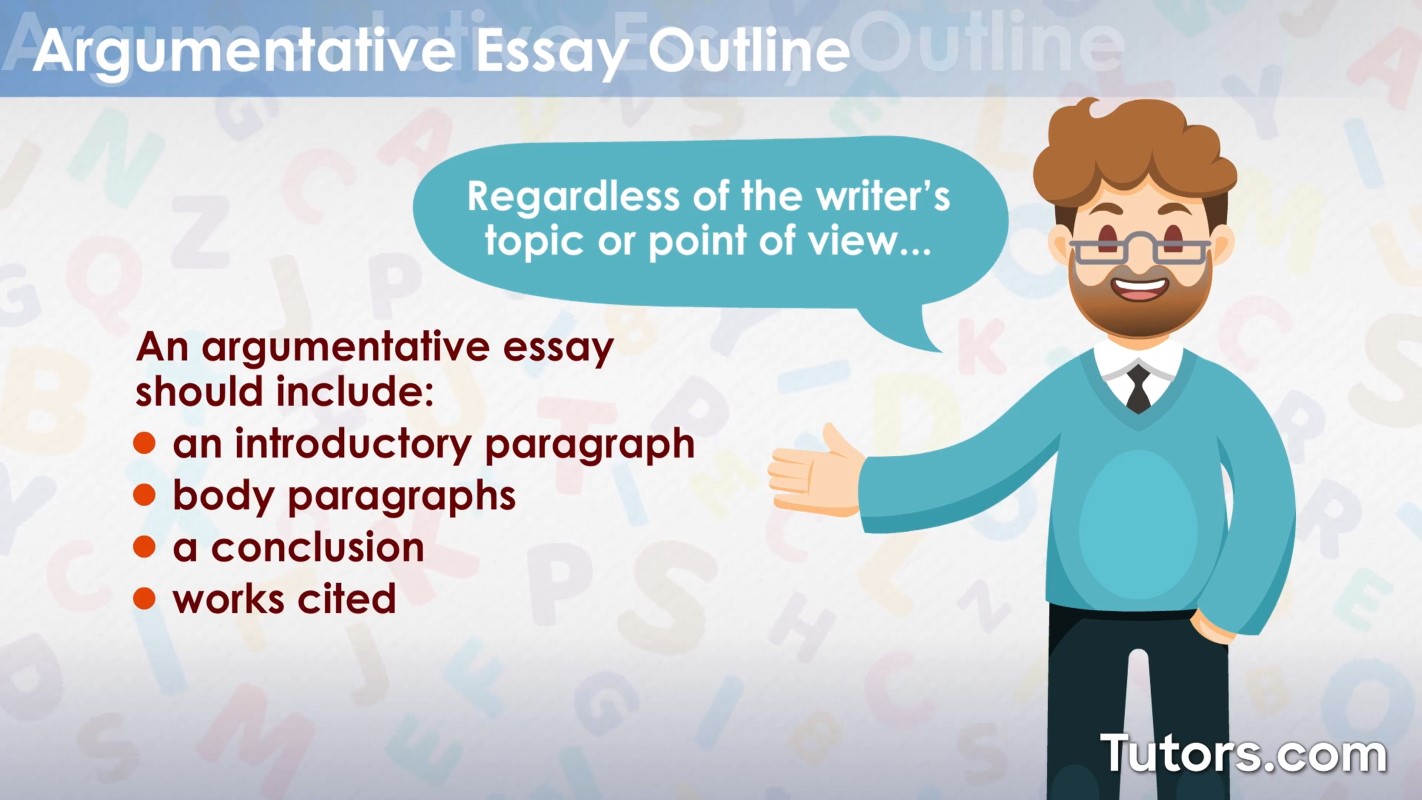

The professor replied, “An argumentative essay is a type of academic writing that presents a clear argument or a firm position on a contentious issue. Unlike other forms of essays, such as descriptive or narrative essays, these essays require you to take a stance, present evidence, and convince your audience of the validity of your viewpoint with supporting evidence. A well-crafted argumentative essay relies on concrete facts and supporting evidence rather than merely expressing the author’s personal opinions . Furthermore, these essays demand comprehensive research on the chosen topic and typically follows a structured format consisting of three primary sections: an introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph.”

He continued, “Argumentative essays are written in a wide range of subject areas, reflecting their applicability across disciplines. They are written in different subject areas like literature and philosophy, history, science and technology, political science, psychology, economics and so on.

Alex asked,

“When is an Argumentative Essay Written?”

The professor answered, “Argumentative essays are often assigned in academic settings, but they can also be written for various other purposes, such as editorials, opinion pieces, or blog posts. Some situations to write argumentative essays include:

1. Academic assignments

In school or college, teachers may assign argumentative essays as part of coursework. It help students to develop critical thinking and persuasive writing skills .

2. Debates and discussions

Argumentative essays can serve as the basis for debates or discussions in academic or competitive settings. Moreover, they provide a structured way to present and defend your viewpoint.

3. Opinion pieces

Newspapers, magazines, and online publications often feature opinion pieces that present an argument on a current issue or topic to influence public opinion.

4. Policy proposals

In government and policy-related fields, argumentative essays are used to propose and defend specific policy changes or solutions to societal problems.

5. Persuasive speeches

Before delivering a persuasive speech, it’s common to prepare an argumentative essay as a foundation for your presentation.

Regardless of the context, an argumentative essay should present a clear thesis statement , provide evidence and reasoning to support your position, address counterarguments, and conclude with a compelling summary of your main points. The goal is to persuade readers or listeners to accept your viewpoint or at least consider it seriously.”

Handing over a book, the professor continued, “Take a look on the elements or structure of an argumentative essay.”

Elements of an Argumentative Essay

An argumentative essay comprises five essential components:

Claim in argumentative writing is the central argument or viewpoint that the writer aims to establish and defend throughout the essay. A claim must assert your position on an issue and must be arguable. It can guide the entire argument.

2. Evidence

Evidence must consist of factual information, data, examples, or expert opinions that support the claim. Also, it lends credibility by strengthening the writer’s position.

3. Counterarguments

Presenting a counterclaim demonstrates fairness and awareness of alternative perspectives.

4. Rebuttal

After presenting the counterclaim, the writer refutes it by offering counterarguments or providing evidence that weakens the opposing viewpoint. It shows that the writer has considered multiple perspectives and is prepared to defend their position.

The format of an argumentative essay typically follows the structure to ensure clarity and effectiveness in presenting an argument.

How to Write An Argumentative Essay

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to write an argumentative essay:

1. Introduction

- Begin with a compelling sentence or question to grab the reader’s attention.

- Provide context for the issue, including relevant facts, statistics, or historical background.

- Provide a concise thesis statement to present your position on the topic.

2. Body Paragraphs (usually three or more)

- Start each paragraph with a clear and focused topic sentence that relates to your thesis statement.

- Furthermore, provide evidence and explain the facts, statistics, examples, expert opinions, and quotations from credible sources that supports your thesis.

- Use transition sentences to smoothly move from one point to the next.

3. Counterargument and Rebuttal

- Acknowledge opposing viewpoints or potential objections to your argument.

- Also, address these counterarguments with evidence and explain why they do not weaken your position.

4. Conclusion

- Restate your thesis statement and summarize the key points you’ve made in the body of the essay.

- Leave the reader with a final thought, call to action, or broader implication related to the topic.

5. Citations and References

- Properly cite all the sources you use in your essay using a consistent citation style.

- Also, include a bibliography or works cited at the end of your essay.

6. Formatting and Style

- Follow any specific formatting guidelines provided by your instructor or institution.

- Use a professional and academic tone in your writing and edit your essay to avoid content, spelling and grammar mistakes .

Remember that the specific requirements for formatting an argumentative essay may vary depending on your instructor’s guidelines or the citation style you’re using (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago). Always check the assignment instructions or style guide for any additional requirements or variations in formatting.

Did you understand what Prof. Mitchell explained Alex? Check it now!

Fill the Details to Check Your Score

Prof. Mitchell continued, “An argumentative essay can adopt various approaches when dealing with opposing perspectives. It may offer a balanced presentation of both sides, providing equal weight to each, or it may advocate more strongly for one side while still acknowledging the existence of opposing views.” As Alex listened carefully to the Professor’s thoughts, his eyes fell on a page with examples of argumentative essay.

Example of an Argumentative Essay

Alex picked the book and read the example. It helped him to understand the concept. Furthermore, he could now connect better to the elements and steps of the essay which Prof. Mitchell had mentioned earlier. Aren’t you keen to know how an argumentative essay should be like? Here is an example of a well-crafted argumentative essay , which was read by Alex. After Alex finished reading the example, the professor turned the page and continued, “Check this page to know the importance of writing an argumentative essay in developing skills of an individual.”

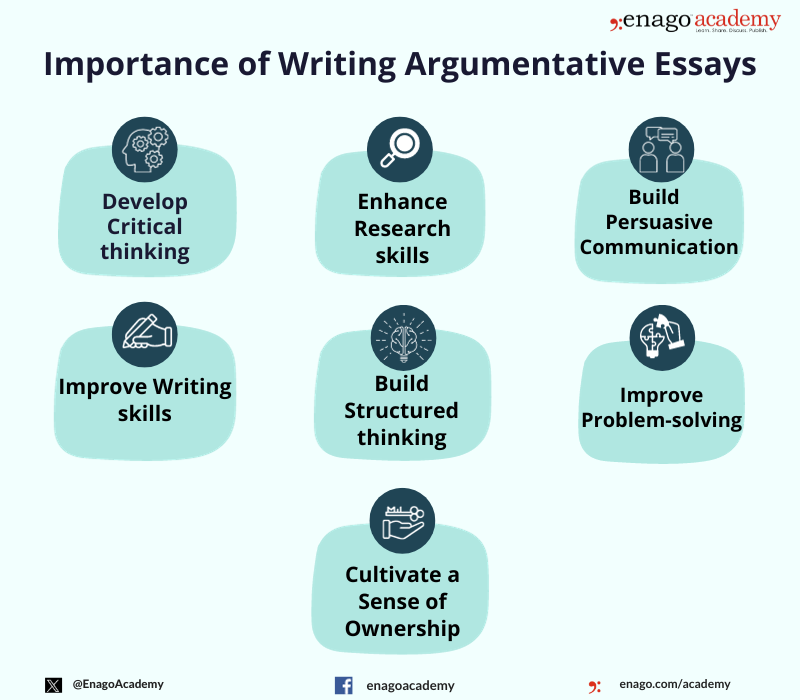

Importance of an Argumentative Essay

After understanding the benefits, Alex was convinced by the ability of the argumentative essays in advocating one’s beliefs and favor the author’s position. Alex asked,

“How are argumentative essays different from the other types?”

Prof. Mitchell answered, “Argumentative essays differ from other types of essays primarily in their purpose, structure, and approach in presenting information. Unlike expository essays, argumentative essays persuade the reader to adopt a particular point of view or take a specific action on a controversial issue. Furthermore, they differ from descriptive essays by not focusing vividly on describing a topic. Also, they are less engaging through storytelling as compared to the narrative essays.

Alex said, “Given the direct and persuasive nature of argumentative essays, can you suggest some strategies to write an effective argumentative essay?

Turning the pages of the book, Prof. Mitchell replied, “Sure! You can check this infographic to get some tips for writing an argumentative essay.”

Effective Strategies to Write an Argumentative Essay

As days turned into weeks, Alex diligently worked on his essay. He researched, gathered evidence, and refined his thesis. It was a long and challenging journey, filled with countless drafts and revisions.

Finally, the day arrived when Alex submitted their essay. As he clicked the “Submit” button, a sense of accomplishment washed over him. He realized that the argumentative essay, while challenging, had improved his critical thinking and transformed him into a more confident writer. Furthermore, Alex received feedback from his professor, a mix of praise and constructive criticism. It was a humbling experience, a reminder that every journey has its obstacles and opportunities for growth.

Frequently Asked Questions

An argumentative essay can be written as follows- 1. Choose a Topic 2. Research and Collect Evidences 3. Develop a Clear Thesis Statement 4. Outline Your Essay- Introduction, Body Paragraphs and Conclusion 5. Revise and Edit 6. Format and Cite Sources 7. Final Review

One must choose a clear, concise and specific statement as a claim. It must be debatable and establish your position. Avoid using ambiguous or unclear while making a claim. To strengthen your claim, address potential counterarguments or opposing viewpoints. Additionally, use persuasive language and rhetoric to make your claim more compelling

Starting an argument essay effectively is crucial to engage your readers and establish the context for your argument. Here’s how you can start an argument essay are: 1. Begin With an Engaging Hook 2. Provide Background Information 3. Present Your Thesis Statement 4. Briefly Outline Your Main 5. Establish Your Credibility

The key features of an argumentative essay are: 1. Clear and Specific Thesis Statement 2. Credible Evidence 3. Counterarguments 4. Structured Body Paragraph 5. Logical Flow 6. Use of Persuasive Techniques 7. Formal Language

An argumentative essay typically consists of the following main parts or sections: 1. Introduction 2. Body Paragraphs 3. Counterargument and Rebuttal 4. Conclusion 5. References (if applicable)

The main purpose of an argumentative essay is to persuade the reader to accept or agree with a particular viewpoint or position on a controversial or debatable topic. In other words, the primary goal of an argumentative essay is to convince the audience that the author's argument or thesis statement is valid, logical, and well-supported by evidence and reasoning.

Great article! The topic is simplified well! Keep up the good work

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Career Corner

- Trending Now

Recognizing the signs: A guide to overcoming academic burnout

As the sun set over the campus, casting long shadows through the library windows, Alex…

- Diversity and Inclusion

Reassessing the Lab Environment to Create an Equitable and Inclusive Space

The pursuit of scientific discovery has long been fueled by diverse minds and perspectives. Yet…

- AI in Academia

Simplifying the Literature Review Journey — A comparative analysis of 6 AI summarization tools

Imagine having to skim through and read mountains of research papers and books, only to…

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

How to Improve Lab Report Writing: Best practices to follow with and without AI-assistance

Imagine you’re a scientist who just made a ground-breaking discovery! You want to share your…

How to Improve Lab Report Writing: Best practices to follow with and without…

Digital Citations: A comprehensive guide to citing of websites in APA, MLA, and CMOS…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

We define an argumentative essay as a type of essay that presents arguments about both sides of an issue. The purpose is to convince the reader to accept a particular viewpoint or action. In an argumentative essay, the writer takes a stance on a controversial or debatable topic and supports their position with evidence, reasoning, and examples. The essay should also address counterarguments, demonstrating a thorough understanding of the topic.

Table of Contents

- What is an argumentative essay?

- Argumentative essay structure

- Argumentative essay outline

- Types of argument claims

How to write an argumentative essay?

- Argumentative essay writing tips

- Good argumentative essay example

How to write a good thesis

- How to Write an Argumentative Essay with Paperpal?

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an argumentative essay.

An argumentative essay is a type of writing that presents a coherent and logical analysis of a specific topic. 1 The goal is to convince the reader to accept the writer’s point of view or opinion on a particular issue. Here are the key elements of an argumentative essay:

- Thesis Statement : The central claim or argument that the essay aims to prove.

- Introduction : Provides background information and introduces the thesis statement.

- Body Paragraphs : Each paragraph addresses a specific aspect of the argument, presents evidence, and may include counter arguments.

Articulate your thesis statement better with Paperpal. Start writing now!

- Evidence : Supports the main argument with relevant facts, examples, statistics, or expert opinions.

- Counterarguments : Anticipates and addresses opposing viewpoints to strengthen the overall argument.

- Conclusion : Summarizes the main points, reinforces the thesis, and may suggest implications or actions.

Argumentative essay structure

Aristotelian, Rogerian, and Toulmin are three distinct approaches to argumentative essay structures, each with its principles and methods. 2 The choice depends on the purpose and nature of the topic. Here’s an overview of each type of argumentative essay format.

Have a looming deadline for your argumentative essay? Write 2x faster with Paperpal – Start now!

Argumentative essay outline

An argumentative essay presents a specific claim or argument and supports it with evidence and reasoning. Here’s an outline for an argumentative essay, along with examples for each section: 3

1. Introduction :

- Hook : Start with a compelling statement, question, or anecdote to grab the reader’s attention.

Example: “Did you know that plastic pollution is threatening marine life at an alarming rate?”

- Background information : Provide brief context about the issue.

Example: “Plastic pollution has become a global environmental concern, with millions of tons of plastic waste entering our oceans yearly.”

- Thesis statement : Clearly state your main argument or position.

Example: “We must take immediate action to reduce plastic usage and implement more sustainable alternatives to protect our marine ecosystem.”

2. Body Paragraphs :

- Topic sentence : Introduce the main idea of each paragraph.

Example: “The first step towards addressing the plastic pollution crisis is reducing single-use plastic consumption.”

- Evidence/Support : Provide evidence, facts, statistics, or examples that support your argument.

Example: “Research shows that plastic straws alone contribute to millions of tons of plastic waste annually, and many marine animals suffer from ingestion or entanglement.”

- Counterargument/Refutation : Acknowledge and refute opposing viewpoints.

Example: “Some argue that banning plastic straws is inconvenient for consumers, but the long-term environmental benefits far outweigh the temporary inconvenience.”

- Transition : Connect each paragraph to the next.

Example: “Having addressed the issue of single-use plastics, the focus must now shift to promoting sustainable alternatives.”

3. Counterargument Paragraph :

- Acknowledgement of opposing views : Recognize alternative perspectives on the issue.

Example: “While some may argue that individual actions cannot significantly impact global plastic pollution, the cumulative effect of collective efforts must be considered.”

- Counterargument and rebuttal : Present and refute the main counterargument.

Example: “However, individual actions, when multiplied across millions of people, can substantially reduce plastic waste. Small changes in behavior, such as using reusable bags and containers, can have a significant positive impact.”

4. Conclusion :

- Restatement of thesis : Summarize your main argument.

Example: “In conclusion, adopting sustainable practices and reducing single-use plastic is crucial for preserving our oceans and marine life.”

- Call to action : Encourage the reader to take specific steps or consider the argument’s implications.

Example: “It is our responsibility to make environmentally conscious choices and advocate for policies that prioritize the health of our planet. By collectively embracing sustainable alternatives, we can contribute to a cleaner and healthier future.”

Types of argument claims

A claim is a statement or proposition a writer puts forward with evidence to persuade the reader. 4 Here are some common types of argument claims, along with examples:

- Fact Claims : These claims assert that something is true or false and can often be verified through evidence. Example: “Water boils at 100°C at sea level.”

- Value Claims : Value claims express judgments about the worth or morality of something, often based on personal beliefs or societal values. Example: “Organic farming is more ethical than conventional farming.”

- Policy Claims : Policy claims propose a course of action or argue for a specific policy, law, or regulation change. Example: “Schools should adopt a year-round education system to improve student learning outcomes.”

- Cause and Effect Claims : These claims argue that one event or condition leads to another, establishing a cause-and-effect relationship. Example: “Excessive use of social media is a leading cause of increased feelings of loneliness among young adults.”

- Definition Claims : Definition claims assert the meaning or classification of a concept or term. Example: “Artificial intelligence can be defined as machines exhibiting human-like cognitive functions.”

- Comparative Claims : Comparative claims assert that one thing is better or worse than another in certain respects. Example: “Online education is more cost-effective than traditional classroom learning.”

- Evaluation Claims : Evaluation claims assess the quality, significance, or effectiveness of something based on specific criteria. Example: “The new healthcare policy is more effective in providing affordable healthcare to all citizens.”

Understanding these argument claims can help writers construct more persuasive and well-supported arguments tailored to the specific nature of the claim.

If you’re wondering how to start an argumentative essay, here’s a step-by-step guide to help you with the argumentative essay format and writing process.

- Choose a Topic: Select a topic that you are passionate about or interested in. Ensure that the topic is debatable and has two or more sides.

- Define Your Position: Clearly state your stance on the issue. Consider opposing viewpoints and be ready to counter them.

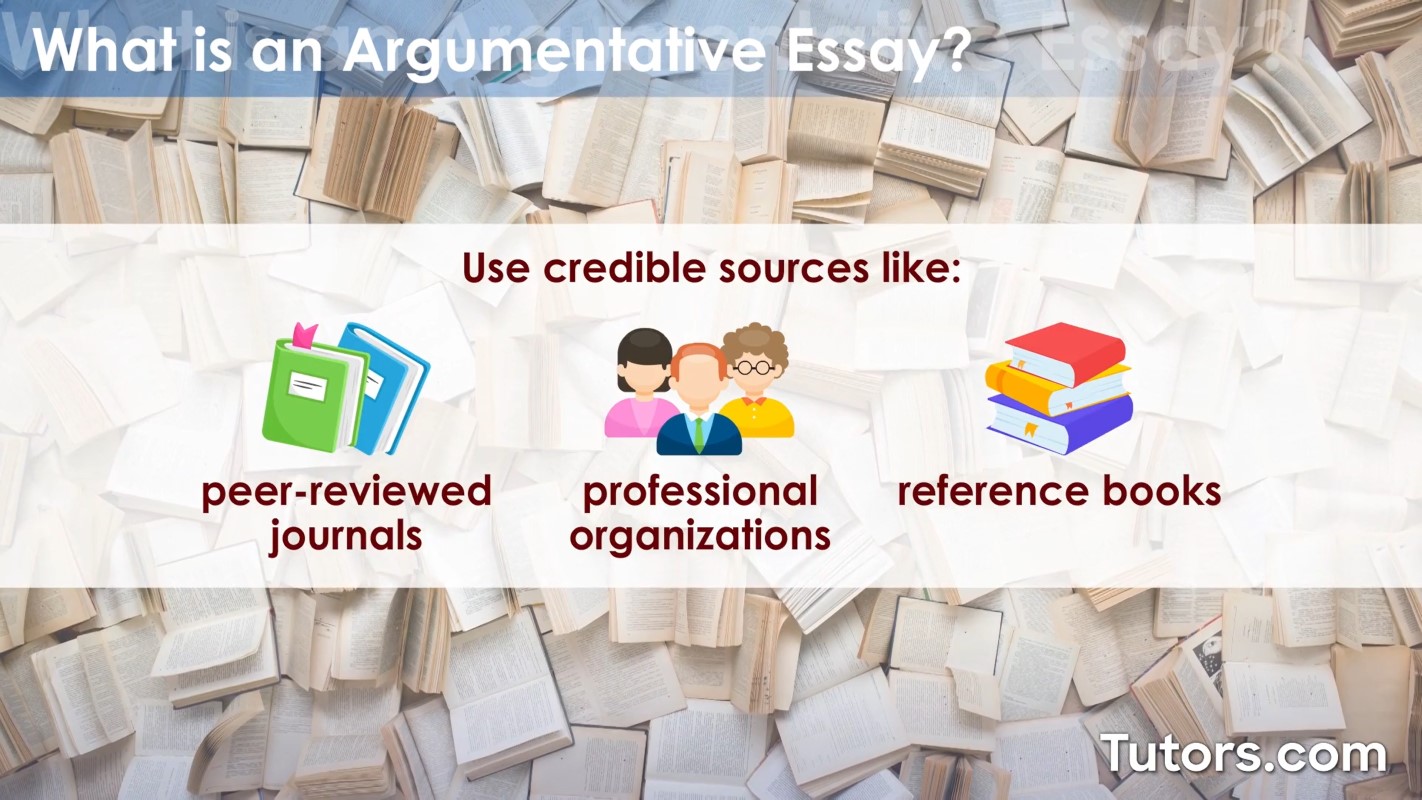

- Conduct Research: Gather relevant information from credible sources, such as books, articles, and academic journals. Take notes on key points and supporting evidence.

- Create a Thesis Statement: Develop a concise and clear thesis statement that outlines your main argument. Convey your position on the issue and provide a roadmap for the essay.

- Outline Your Argumentative Essay: Organize your ideas logically by creating an outline. Include an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Each body paragraph should focus on a single point that supports your thesis.

- Write the Introduction: Start with a hook to grab the reader’s attention (a quote, a question, a surprising fact). Provide background information on the topic. Present your thesis statement at the end of the introduction.

- Develop Body Paragraphs: Begin each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that relates to the thesis. Support your points with evidence and examples. Address counterarguments and refute them to strengthen your position. Ensure smooth transitions between paragraphs.

- Address Counterarguments: Acknowledge and respond to opposing viewpoints. Anticipate objections and provide evidence to counter them.

- Write the Conclusion: Summarize the main points of your argumentative essay. Reinforce the significance of your argument. End with a call to action, a prediction, or a thought-provoking statement.

- Revise, Edit, and Share: Review your essay for clarity, coherence, and consistency. Check for grammatical and spelling errors. Share your essay with peers, friends, or instructors for constructive feedback.

- Finalize Your Argumentative Essay: Make final edits based on feedback received. Ensure that your essay follows the required formatting and citation style.

Struggling to start your argumentative essay? Paperpal can help – try now!

Argumentative essay writing tips

Here are eight strategies to craft a compelling argumentative essay:

- Choose a Clear and Controversial Topic : Select a topic that sparks debate and has opposing viewpoints. A clear and controversial issue provides a solid foundation for a strong argument.

- Conduct Thorough Research : Gather relevant information from reputable sources to support your argument. Use a variety of sources, such as academic journals, books, reputable websites, and expert opinions, to strengthen your position.

- Create a Strong Thesis Statement : Clearly articulate your main argument in a concise thesis statement. Your thesis should convey your stance on the issue and provide a roadmap for the reader to follow your argument.

- Develop a Logical Structure : Organize your essay with a clear introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. Each paragraph should focus on a specific point of evidence that contributes to your overall argument. Ensure a logical flow from one point to the next.

- Provide Strong Evidence : Support your claims with solid evidence. Use facts, statistics, examples, and expert opinions to support your arguments. Be sure to cite your sources appropriately to maintain credibility.

- Address Counterarguments : Acknowledge opposing viewpoints and counterarguments. Addressing and refuting alternative perspectives strengthens your essay and demonstrates a thorough understanding of the issue. Be mindful of maintaining a respectful tone even when discussing opposing views.

- Use Persuasive Language : Employ persuasive language to make your points effectively. Avoid emotional appeals without supporting evidence and strive for a respectful and professional tone.

- Craft a Compelling Conclusion : Summarize your main points, restate your thesis, and leave a lasting impression in your conclusion. Encourage readers to consider the implications of your argument and potentially take action.

Good argumentative essay example

Let’s consider a sample of argumentative essay on how social media enhances connectivity:

In the digital age, social media has emerged as a powerful tool that transcends geographical boundaries, connecting individuals from diverse backgrounds and providing a platform for an array of voices to be heard. While critics argue that social media fosters division and amplifies negativity, it is essential to recognize the positive aspects of this digital revolution and how it enhances connectivity by providing a platform for diverse voices to flourish. One of the primary benefits of social media is its ability to facilitate instant communication and connection across the globe. Platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram break down geographical barriers, enabling people to establish and maintain relationships regardless of physical location and fostering a sense of global community. Furthermore, social media has transformed how people stay connected with friends and family. Whether separated by miles or time zones, social media ensures that relationships remain dynamic and relevant, contributing to a more interconnected world. Moreover, social media has played a pivotal role in giving voice to social justice movements and marginalized communities. Movements such as #BlackLivesMatter, #MeToo, and #ClimateStrike have gained momentum through social media, allowing individuals to share their stories and advocate for change on a global scale. This digital activism can shape public opinion and hold institutions accountable. Social media platforms provide a dynamic space for open dialogue and discourse. Users can engage in discussions, share information, and challenge each other’s perspectives, fostering a culture of critical thinking. This open exchange of ideas contributes to a more informed and enlightened society where individuals can broaden their horizons and develop a nuanced understanding of complex issues. While criticisms of social media abound, it is crucial to recognize its positive impact on connectivity and the amplification of diverse voices. Social media transcends physical and cultural barriers, connecting people across the globe and providing a platform for marginalized voices to be heard. By fostering open dialogue and facilitating the exchange of ideas, social media contributes to a more interconnected and empowered society. Embracing the positive aspects of social media allows us to harness its potential for positive change and collective growth.

- Clearly Define Your Thesis Statement: Your thesis statement is the core of your argumentative essay. Clearly articulate your main argument or position on the issue. Avoid vague or general statements.

- Provide Strong Supporting Evidence: Back up your thesis with solid evidence from reliable sources and examples. This can include facts, statistics, expert opinions, anecdotes, or real-life examples. Make sure your evidence is relevant to your argument, as it impacts the overall persuasiveness of your thesis.

- Anticipate Counterarguments and Address Them: Acknowledge and address opposing viewpoints to strengthen credibility. This also shows that you engage critically with the topic rather than presenting a one-sided argument.

How to Write an Argumentative Essay with Paperpal?

Writing a winning argumentative essay not only showcases your ability to critically analyze a topic but also demonstrates your skill in persuasively presenting your stance backed by evidence. Achieving this level of writing excellence can be time-consuming. This is where Paperpal, your AI academic writing assistant, steps in to revolutionize the way you approach argumentative essays. Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to use Paperpal to write your essay:

- Sign Up or Log In: Begin by creating an account or logging into paperpal.com .

- Navigate to Paperpal Copilot: Once logged in, proceed to the Templates section from the side navigation bar.

- Generate an essay outline: Under Templates, click on the ‘Outline’ tab and choose ‘Essay’ from the options and provide your topic to generate an outline.

- Develop your essay: Use this structured outline as a guide to flesh out your essay. If you encounter any roadblocks, click on Brainstorm and get subject-specific assistance, ensuring you stay on track.

- Refine your writing: To elevate the academic tone of your essay, select a paragraph and use the ‘Make Academic’ feature under the ‘Rewrite’ tab, ensuring your argumentative essay resonates with an academic audience.

- Final Touches: Make your argumentative essay submission ready with Paperpal’s language, grammar, consistency and plagiarism checks, and improve your chances of acceptance.

Paperpal not only simplifies the essay writing process but also ensures your argumentative essay is persuasive, well-structured, and academically rigorous. Sign up today and transform how you write argumentative essays.

The length of an argumentative essay can vary, but it typically falls within the range of 1,000 to 2,500 words. However, the specific requirements may depend on the guidelines provided.

You might write an argumentative essay when: 1. You want to convince others of the validity of your position. 2. There is a controversial or debatable issue that requires discussion. 3. You need to present evidence and logical reasoning to support your claims. 4. You want to explore and critically analyze different perspectives on a topic.

Argumentative Essay: Purpose : An argumentative essay aims to persuade the reader to accept or agree with a specific point of view or argument. Structure : It follows a clear structure with an introduction, thesis statement, body paragraphs presenting arguments and evidence, counterarguments and refutations, and a conclusion. Tone : The tone is formal and relies on logical reasoning, evidence, and critical analysis. Narrative/Descriptive Essay: Purpose : These aim to tell a story or describe an experience, while a descriptive essay focuses on creating a vivid picture of a person, place, or thing. Structure : They may have a more flexible structure. They often include an engaging introduction, a well-developed body that builds the story or description, and a conclusion. Tone : The tone is more personal and expressive to evoke emotions or provide sensory details.

- Gladd, J. (2020). Tips for Writing Academic Persuasive Essays. Write What Matters .

- Nimehchisalem, V. (2018). Pyramid of argumentation: Towards an integrated model for teaching and assessing ESL writing. Language & Communication , 5 (2), 185-200.

- Press, B. (2022). Argumentative Essays: A Step-by-Step Guide . Broadview Press.

- Rieke, R. D., Sillars, M. O., & Peterson, T. R. (2005). Argumentation and critical decision making . Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

- Life Sciences Papers: 9 Tips for Authors Writing in Biological Sciences

Make Your Research Paper Error-Free with Paperpal’s Online Spell Checker

The do’s & don’ts of using generative ai tools ethically in academia, you may also like, how to use paperpal to generate emails &..., ai in education: it’s time to change the..., is it ethical to use ai-generated abstracts without..., do plagiarism checkers detect ai content, word choice problems: how to use the right..., how to avoid plagiarism when using generative ai..., what are journal guidelines on using generative ai..., types of plagiarism and 6 tips to avoid..., how to write an essay introduction (with examples)..., similarity checks: the author’s guide to plagiarism and....

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, how to write an a+ argumentative essay.

Miscellaneous

You'll no doubt have to write a number of argumentative essays in both high school and college, but what, exactly, is an argumentative essay and how do you write the best one possible? Let's take a look.

A great argumentative essay always combines the same basic elements: approaching an argument from a rational perspective, researching sources, supporting your claims using facts rather than opinion, and articulating your reasoning into the most cogent and reasoned points. Argumentative essays are great building blocks for all sorts of research and rhetoric, so your teachers will expect you to master the technique before long.

But if this sounds daunting, never fear! We'll show how an argumentative essay differs from other kinds of papers, how to research and write them, how to pick an argumentative essay topic, and where to find example essays. So let's get started.

What Is an Argumentative Essay? How Is it Different from Other Kinds of Essays?

There are two basic requirements for any and all essays: to state a claim (a thesis statement) and to support that claim with evidence.

Though every essay is founded on these two ideas, there are several different types of essays, differentiated by the style of the writing, how the writer presents the thesis, and the types of evidence used to support the thesis statement.

Essays can be roughly divided into four different types:

#1: Argumentative #2: Persuasive #3: Expository #4: Analytical

So let's look at each type and what the differences are between them before we focus the rest of our time to argumentative essays.

Argumentative Essay

Argumentative essays are what this article is all about, so let's talk about them first.

An argumentative essay attempts to convince a reader to agree with a particular argument (the writer's thesis statement). The writer takes a firm stand one way or another on a topic and then uses hard evidence to support that stance.

An argumentative essay seeks to prove to the reader that one argument —the writer's argument— is the factually and logically correct one. This means that an argumentative essay must use only evidence-based support to back up a claim , rather than emotional or philosophical reasoning (which is often allowed in other types of essays). Thus, an argumentative essay has a burden of substantiated proof and sources , whereas some other types of essays (namely persuasive essays) do not.

You can write an argumentative essay on any topic, so long as there's room for argument. Generally, you can use the same topics for both a persuasive essay or an argumentative one, so long as you support the argumentative essay with hard evidence.

Example topics of an argumentative essay:

- "Should farmers be allowed to shoot wolves if those wolves injure or kill farm animals?"

- "Should the drinking age be lowered in the United States?"

- "Are alternatives to democracy effective and/or feasible to implement?"

The next three types of essays are not argumentative essays, but you may have written them in school. We're going to cover them so you know what not to do for your argumentative essay.

Persuasive Essay

Persuasive essays are similar to argumentative essays, so it can be easy to get them confused. But knowing what makes an argumentative essay different than a persuasive essay can often mean the difference between an excellent grade and an average one.