What is academic writing and why is it important?

Dec 27, 2020 | Academic Writing , College Applications , Englist blog , TOEFL Prep | 0 comments

Academic writing has become an increasingly important part of education as parents and educators realize the value of critical thinking skills and preparing students for college.

Still, many students, parents, and even other teachers don’t have a great grasp on this area of learning and why it is so critical.

As such, at Englist we find it is important to not only teach academic writing, but also help everyone understand why it is imperative to the development of thoughtful and capable students.

What is academic writing?

First, what is academic writing? Most students see writing as something they just have to do because a teacher says so, and it becomes a painful and time-consuming assignment. Our mission is to end this kind of thinking.

Simply put, academic writing is teaching students how to write essays. That sounds pretty simple, but there is a lot more to it than that.

Essay writing is the process of sharing complex ideas, thoughts, or opinions. Writers learn to construct a rather complicated argument or explanation by combining sentences into paragraphs and paragraphs into an essay.

Academic writing demands writers become clear in their explanations and reasoning, direct in their communication, and most importantly, able to make readers understand their topic and thesis.

It may seem obvious, but this is one of the key principles behind any kind of research. Whether you are trying to find a cure for cancer, unpick the secrets of the universe or simply find out how to cook a different type of quiche, that vast repository of existing human knowledge can show you where to start.

In order to do something new and original, you need to know what people have done before you, so that you can build on it. Even Einstein's ground-breaking work on relativity, as famous as it made him, was re-imagined from other renowned physicists' work, such as Hendrik Lorentz and Hermann Minowski.

It's not just of benefit for other researchers. One of the main reasons for writing up academic research is to persuade someone that the conclusions from your research are correct . A sticking point for many researchers (myself included) is that the writing process is often seen as separate to research itself.

This may be more of an issue in the physical sciences or disciplines with a large amount of field work. You might be collecting results in a lab or in the field to write up later, whereas in many of the humanities, research and writing tend to go hand in hand. Writing about your research can help you criticise existing results, pick out any gaps in your evidence or argument that need to be filled, or simply just help organise your thoughts.

"Research isn't research until it's written down" - Anon

There is also the matter of accountability. A large proportion of research carried out in the UK is funded by public money, which is accounted for by the Research Excellence Framework (REF). One of the principles behind the REF is " open access " - research should be made freely available to the public and not kept behind inaccessible paywalls.

Open access and open research could form the topics of several blog posts, but fundamentally it comes down to ensuring research is communicated freely and transparently. Which, of course, leads us neatly back to writing!

Why people find writing so challenging

If you mention thesis writing to most research students, odds are this will bring them out in a cold sweat. The prospect of any kind of academic writing can bring out stress and anxiety in the best of academics. Everyone will have different reasons why, but there certainly are a few common themes.

One of the biggest concerns is that you are putting your professional opinions out for scrutiny by other academics and the wider world. You need to have the evidence and research to back it up, all presented coherently and formatted neatly, taking into account all of your discipline's idiosyncrasies in style, with the right tools to hand, and enough time to do it.

Time is a big factor for many academics, particularly those who are heavily responsible for teaching, as finding a slot in your timetable to sit and write up your research can be extremely challenging. Being able to write both with speed and quality takes a lot of practice - which is going to be even more difficult if you are short on time.

There is also a huge variation across universities in both the quality and content of how undergraduate and postgraduate students are taught how to write academically. It's not unheard of to find people who have written their doctoral thesis, who are now publishing in journals as a researcher, that have never had any formal academic writing education at university.

What we are doing to help

In November, we took part for the first time in WRITEfest2018 - a collaborative celebration of academic writing between a number of universities around the world. It is designed to promote skills and good practice in academic writing, and to get academics away from their desks and just "shut up and write".

As part of this, we ran masterclasses to help researchers with writing strategies to better structure their writing, making use of short blocks of available time. We have run workshops on specific styles of academic writing, such as bid writing, publications in journals and books. This is in addition to workshops for our research students and a 12-week academic English module mainly aimed at international students.

We have also blocked out protected writing time slots so researchers can put the skills from these masterclasses into practice. The overall goal is to help remove the barriers to writing, so researchers can more easily communicate the great research they are doing with the wider world.

For further information contact the press office at [email protected] .

About the author

Stuart archer former researcher (researcher development).

Stuart Archer is the former Lead for the Researcher Development Programme at the University of Derby. He is also a research chemist by training.

Related categories

The Value of Writing

- Original Article

- Published: 27 May 2022

- Volume 59 , pages 556–563, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- John Simmons 1

876 Accesses

13 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Writing can give us all greater joy. Does that sentence make sense in the academic world? Writing rarely receives the academic attention it deserves. Its value in conveying information, ideas, and argument is obvious, but do we neglect the positive contribution that the quality of writing can add to academic papers? This essay argues that too much academic writing loses impact by striving too hard for ‘impossible objectivity’. Arguments need emotion too, provided by stories and words used well, which benefits writers and readers. This essay suggests reasons for giving greater attention to the way we write: from personal fulfilment, through to persuasive power, to writing’s ability to make connections. Writing has the potential to be a source of joy and inspiration not just a necessary chore that goes with the job.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

Clara Busse & Ella August

Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice

Sascha Kraus, Matthias Breier, … João J. Ferreira

Word problems in mathematics education: a survey

Lieven Verschaffel, Stanislaw Schukajlow, … Wim Van Dooren

Berger, J. 1972. Ways of Seeing . London: Penguin.

Google Scholar

Conant, J. 2003. The concept of America. Society , November/December 2003.

Darwin, C. 1968 [1859]. On the Origin of Species . London: Penguin.

Didion, J. 2003. Where I Was From . London: Flamingo.

Etzioni, A. 2016. Happiness is the Wrong Metric. Society 53 , 246–257.

Article Google Scholar

Frost, R. 1939. The Figure a Poem Makes. In Preface to The Collected Poems of Robert Frost . London: Longman.

Hofstadter, D. 1997. Le Ton beau de Marot . London: Bloomsbury.

King, S. 2000. On Writing . London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Obama, B. 2021. The Guardian . 2 October.

Ogilvy, D. 2012 [1955]. Letter to Mr Calt. In The Unpublished David Ogilvy . London: Profile.

Patterson, O. 2001. The American view of freedom: What we say, what we mean. Society , May/June 2001.

Potter, D. 1994. The Long Goodbye. The Guardian , 6 April.

Saunders, G. 2021. A Swim in the Pond in the Rain . London: Bloomsbury.

Seifert, C. 2020. ‘ The Case for Reading Fiction. Harvard Business Review , March

Simmons, J. (ed). 2019. Making Connections. In Dark Angels on Writing . London: Unbound.

Simmons, J. (ed). 2022. We, Me, Them & It: How to Write Powerfully for Business. London, LID.

Goldberg, N. 2006. Writing Down the Bones . Boston: Shambhala.

Gorman, A. 2021. The Guardian , 11 December.

Smith, A. 2012. Speech to Edinburgh World Writers’ Conference, 18 August.

Sokal, A. 1996. article published in Social Text and admitted as a hoax by the author in Lingua Franca (1996) ‘A Physicist Experiments with Social Studies’.

Sondheim, S. 2011. Look, I Made a Hat . London: Virgin Books.

Stoppard, T. 1982. The Real Thing . London: Faber & Faber.

Book Google Scholar

Thunberg, G. 2019. Speech to the United Nations Climate Action Summit, September 24.

Valmorbida, E. 2021. The Happy Writing Book . London: Laurence King Publishing.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Dark Angels, London, England, UK

John Simmons

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to John Simmons .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Simmons, J. The Value of Writing. Soc 59 , 556–563 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-022-00731-x

Download citation

Published : 27 May 2022

Issue Date : October 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-022-00731-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Only connect

- Inspiration

- Imagination

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.2: What is Academic Writing

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 69724

- Elizabeth Burrows, Angela Fowler, Heath Fowler, and Amy Locklear

- Auburn University at Montgomery

Articles links:

“What Is ‘Academic’ Writing?” by L. Lennie Irvin

“What is an Essay?” provided by Candela Open Courses

“Critical Thinking in College Writing: From the Personal to the Academic” by Gita DasBender

Chapter Preview

- Explore academic writing myths.

- Identify characteristics of academic writing.

- Describe what first-year writing courses are designed to teach.

A YouTube element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: pb.libretexts.org/composing2/?p=39

What Is “Academic” Writing?

by L. Lennie Irvin

Introduction: The Academic Writing Task

As a new college student, you may have a lot of anxiety and questions about the writing you’ll do in college.* That word “academic,” especially, may turn your stomach or turn your nose. However, with this first year composition class, you begin one of the only classes in your entire college career where you will focus on learning to write. Given the importance of writing as a communication skill, I urge you to consider this class as a gift and make the most of it. But writing is hard, and writing in college may resemble playing a familiar game by completely new rules (that often are unstated). This chapter is designed to introduce you to what academic writing is like, and hopefully ease your transition as you face these daunting writing challenges.

So here’s the secret. Your success with academic writing depends upon how well you understand what you are doing as you write and then how you approach the writing task. Early research done on college writers discovered that whether students produced a successful piece of writing depended largely upon their representation of the writing task. The writers’ mental model for picturing their task made a huge difference. Most people as they start college have wildly strange ideas about what they are doing when they write an essay, or worse—they have no clear idea at all. I freely admit my own past as a clueless freshman writer, and it’s out of this sympathy as well as twenty years of teaching college writing that I hope to provide you with something useful. So grab a cup of coffee or a diet coke, find a comfortable chair with good light, and let’s explore together this activity of academic writing you’ll be asked to do in college. We will start by clearing up some of those wild misconceptions people often arrive at college possessing. Then we will dig more deeply into the components of the academic writing situation and nature of the writing task.

Myths about Writing

Though I don’t imagine an episode of MythBusters will be based on the misconceptions about writing we are about to look at, you’d still be surprised at some of the things people will believe about writing. You may find lurking within you viral elements of these myths—all of these lead to problems in writing.

Myth #1: The “Paint by Numbers” myth

Some writers believe they must perform certain steps in a particular order to write “correctly.” Rather than being a lock-step linear process, writing is “ recursive .” That means we cycle through and repeat the various activities of the writing process many times as we write.

Myth #2: Writers only start writing when they have everything figured out

Writing is not like sending a fax! Writers figure out much of what they want to write as they write it. Rather than waiting, get some writing on the page—even with gaps or problems. You can come back to patch up rough spots.

Myth #3: Perfect first drafts

We put unrealistic expectations on early drafts, either by focusing too much on the impossible task of making them perfect (which can put a cap on the development of our ideas), or by making too little effort be cause we don’t care or know about their inevitable problems. Nobody writes perfect first drafts; polished writing takes lots of revision.

Myth #4: Some got it; I don’t—the genius fallacy

When you see your writing ability as something fixed or out of your control (as if it were in your genetic code), then you won’t believe you can improve as a writer and are likely not to make any efforts in that direction. With effort and study, though, you can improve as a writer. I promise.

Myth #5: Good grammar is good writing

When people say “I can’t write,” what they often mean is they have problems with grammatical correctness. Writing, however, is about more than just grammatical correctness. Good writing is a matter of achieving your desired effect upon an intended audience. Plus, as we saw in myth #3, no one writes perfect first drafts.

Myth #6: The Five Paragraph Essay

Some people say to avoid it at all costs, while others believe no other way to write exists. With an introduction, three supporting para- graphs, and a conclusion, the five paragraph essay is a format you should know, but one which you will outgrow. You’ll have to gauge the particular writing assignment to see whether and how this format is useful for you.

Myth #7: Never use “I”

Adopting this formal stance of objectivity implies a distrust (almost fear) of informality and often leads to artificial, puffed-up prose. Although some writing situations will call on you to avoid using “I” (for example, a lab report), much college writing can be done in a middle, semi-formal style where it is ok to use “I.”

The Academic Writing Situation

Now that we’ve dispelled some of the common myths that many writers have as they enter a college classroom, let’s take a moment to think about the academic writing situation. The biggest problem I see in freshman writers is a poor sense of the writing situation in general. To illustrate this problem, let’s look at the difference between speaking and writing.

When we speak, we inhabit the communication situation bodily in three dimensions, but in writing we are confined within the two- dimensional setting of the flat page (though writing for the web—or multimodal writing—is changing all that). Writing resembles having a blindfold over our eyes and our hands tied behind our backs: we can’t see exactly whom we’re talking to or where we are. Separated from our audience in place and time, we imaginatively have to create this context. Our words on the page are silent, so we must use punctuation and word choice to communicate our tone. We also can’t see our audience to gauge how our communication is being received or if there will be some kind of response. It’s the same space we share right now as you read this essay. Novice writers often write as if they were mumbling to themselves in the corner with no sense that their writing will be read by a reader or any sense of the context within which their communication will be received.

What’s the moral here? Developing your “writer’s sense” about communicating within the writing situation is the most important thing you should learn in freshman composition.

Looking More Closely at the “Academic Writing” Situation

Writing in college is a fairly specialized writing situation, and it has developed its own codes and conventions that you need to have a keen awareness of if you are going to write successfully in college. Let’s break down the writing situation in college:

So far, this list looks like nothing new. You’ve been writing in school toward teachers for years. What’s different in college? Lee Ann Carroll, a professor at Pepperdine University, performed a study of student writing in college and had this description of the kind of writing you will be doing in college:

What are usually called ‘writing assignments’ in college might more accurately be called ‘literacy tasks’ because they require much more than the ability to construct correct sentences or compose neatly organized paragraphs with topic sentences Projects calling for high levels of critical literacy in college typically require knowledge of research skills, ability to read complex texts, understanding of key disciplinary concepts, and strategies for synthesizing, analyzing, and responding critically to new information, usually within a limited time frame. (3–4)

Academic writing is always a form of evaluation that asks you to demonstrate knowledge and show proficiency with certain disciplinary skills of thinking, interpreting, and presenting. Writing the paper is never “just” the writing part. To be successful in this kind of writing, you must be completely aware of what the professor expects you to do and accomplish with that particular writing task. For a moment, let’s explore more deeply the elements of this college writing “literacy task.”

Knowledge of Research Skills

Perhaps up to now research has meant going straight to Google and Wikipedia, but college will require you to search for and find more in-depth information. You’ll need to know how to find information in the library, especially what is available from online databases which contain scholarly articles. Researching is also a process, so you’ll need to learn how to focus and direct a research project and how to keep track of all your source information. Realize that researching represents a crucial component of most all college writing assignments, and you will need to devote lots of work to this researching.

The Ability to Read Complex Texts

Whereas your previous writing in school might have come generally from your experience, college writing typically asks you to write on unfamiliar topics. Whether you’re reading your textbook, a short story, or scholarly articles from research, your ability to write well will be based upon the quality of your reading. In addition to the labor of close reading, you’ll need to think critically as you read. That means separating fact from opinion, recognizing biases and assumptions, and making inferences. Inferences are how we as readers connect the dots: an inference is a belief (or statement) about something unknown made on the basis of something known. You smell smoke; you infer fire. They are conclusions or interpretations that we arrive at based upon the known factors we discover from our reading. When we, then, write to argue for these interpretations, our job becomes to get our readers to make the same inferences we have made.

The Understanding of Key Disciplinary Concepts

Each discipline whether it is English, Psychology, or History has its own key concepts and language for describing these important ways of understanding the world. Don’t fool yourself that your professors’ writing assignments are asking for your opinion on the topic from just your experience. They want to see you apply and use these concepts in your writing. Though different from a multiple-choice exam, writing similarly requires you to demonstrate your learning. So whatever writing assignment you receive, inspect it closely for what concepts it asks you to bring into your writing.

Strategies for Synthesizing, Analyzing, and Responding Critically to New Information

You need to develop the skill of a seasoned traveler who can be dropped in any city around the world and get by. Each writing assignment asks you to navigate through a new terrain of information, so you must develop ways for grasping new subject matter in order, then, to use it in your writing. We have already seen the importance of reading and research for these literacy tasks, but beyond laying the information out before you, you will need to learn ways of sorting and finding meaningful patterns in this information.

In College, Everything’s an Argument: A Guide for Decoding College Writing Assignments

Let’s restate this complex “literacy task” you’ll be asked repeatedly to do in your writing assignments. Typically, you’ll be required to write an “essay” based upon your analysis of some reading(s). In this essay you’ll need to present an argument where you make a claim (i.e. present a “thesis”) and support that claim with good reasons that have adequate and appropriate evidence to back them up. The dynamic of this argumentative task often confuses first-year writers, so let’s examine it more closely.

Academic Writing Is an Argument

To start, let’s focus on argument. What does it mean to present an “argument” in college writing? Rather than a shouting match between two disagreeing sides, argument instead means a carefully arranged and supported presentation of a viewpoint. Its purpose is not so much to win the argument as to earn your audience’s consideration (and even approval) of your perspective. It resembles a conversation between two people who may not hold the same opinions, but they both desire a better understanding of the subject matter under discussion. My favorite analogy, however, to describe the nature of this argumentative stance in college writing is the courtroom. In this scenario, you are like a lawyer making a case at trial that the defendant is not guilty, and your readers are like the jury who will decide if the defendant is guilty or not guilty. This jury (your readers) won’t just take your word that he’s innocent; instead, you must convince them by presenting evidence that proves he is not guilty. Stating your opinion is not enough—you have to back it up too. I like this courtroom analogy for capturing two importance things about academic argument: 1) the value of an organized presentation of your “case,” and 2) the crucial element of strong evidence.

Academic Writing Is an Analysis

We now turn our attention to the actual writing assignment and that confusing word “analyze.” Your first job when you get a writing assignment is to figure out what the professor expects. This assignment may be explicit in its expectations, but often built into the wording of the most defined writing assignments are implicit expectations that you might not recognize. First, we can say that unless your professor specifically asks you to summarize, you won’t write a summary. Let me say that again: don’t write a summary unless directly asked to. But what, then, does the professor want? We have already picked out a few of these expectations: You can count on the instructor expecting you to read closely, research adequately, and write an argument where you will demonstrate your ability to apply and use important concepts you have been studying. But the writing task also implies that your essay will be the result of an analysis. At times, the writing assignment may even explicitly say to write an analysis, but often this element of the task remains unstated.

So what does it mean to analyze? One way to think of an analysis is that it asks you to seek How and Why questions much more than What questions. An analysis involves doing three things:

- Engage in an open inquiry where the answer is not known at first (and where you leave yourself open to multiple suggestions)

- Identify meaningful parts of the subject

- Examine these separate parts and determine how they relate to each other

An analysis breaks a subject apart to study it closely, and from this inspection, ideas for writing emerge. When writing assignments call on you to analyze, they require you to identify the parts of the subject (parts of an ad, parts of a short story, parts of Hamlet’s character), and then show how these parts fit or don’t fit together to create some larger effect or meaning. Your interpretation of how these parts fit together constitutes your claim or thesis, and the task of your essay is then to present an argument defending your interpretation as a valid or plausible one to make. My biggest bit of advice about analysis is not to do it all in your head. Analysis works best when you put all the cards on the table, so to speak. Identify and isolate the parts of your analysis, and record important features and characteristics of each one. As patterns emerge, you sort and connect these parts in meaningful ways. For me, I have always had to do this recording and thinking on scratch pieces of paper. Just as critical reading forms a crucial element of the literacy task of a college writing assignment, so too does this analysis process. It’s built in.

Three Common Types of College Writing Assignments

We have been decoding the expectations of the academic writing task so far, and I want to turn now to examine the types of assignments you might receive. From my experience, you are likely to get three kinds of writing assignments based upon the instructor’s degree of direction for the assignment. We’ll take a brief look at each kind of academic writing task.

The Closed Writing Assignment

- Is Creon a character to admire or condemn?

- Does your advertisement employ techniques of propaganda, and if so what kind?

- Was the South justified in seceding from the Union?

- In your opinion, do you believe Hamlet was truly mad?

These kinds of writing assignments present you with two counter claims and ask you to determine from your own analysis the more valid claim. They resemble yes-no questions. These topics define the claim for you, so the major task of the writing assignment then is working out the support for the claim. They resemble a math problem in which the teacher has given you the answer and now wants you to “show your work” in arriving at that answer.

Be careful with these writing assignments, however, because often these topics don’t have a simple yes/no, either/or answer (despite the nature of the essay question). A close analysis of the subject matter often reveals nuances and ambiguities within the question that your eventual claim should reflect. Perhaps a claim such as, “In my opinion, Hamlet was mad” might work, but I urge you to avoid such a simplistic thesis. This thesis would be better: “I believe Hamlet’s unhinged mind borders on insanity but doesn’t quite reach it.”

The Semi-Open Writing Assignment

- Discuss the role of law in Antigone.

- Explain the relationship between character and fate in Hamlet.

- Compare and contrast the use of setting in two short stories.

- Show how the Fugitive Slave Act influenced the Abolitionist Movement.

Although these topics chart out a subject matter for you to write upon, they don’t offer up claims you can easily use in your paper. It would be a misstep to offer up claims such as, “Law plays a role in Antigone” or “In Hamlet we can see a relationship between character and fate.” Such statements express the obvious and what the topic takes for granted. The question, for example, is not whether law plays a role in Antigone, but rather what sort of role law plays. What is the nature of this role? What influences does it have on the characters or actions or theme? This kind of writing assignment resembles a kind of archaeological dig. The teacher cordons off an area, hands you a shovel, and says dig here and see what you find. Be sure to avoid summary and mere explanation in this kind of assignment. Despite using key words in the assignment such as “explain,” “illustrate,” analyze,” “discuss,” or “show how,” these topics still ask you to make an argument. Implicit in the topic is the expectation that you will analyze the reading and arrive at some insights into patterns and relationships about the subject. Your eventual paper, then, needs to present what you found from this analysis—the treasure you found from your digging. Determining your own claim represents the biggest challenge for this type of writing assignment.

The Open Writing Assignment

- Analyze the role of a character in Dante’s The Inferno.

- What does it mean to be an “American” in the 21st Century?

- Analyze the influence of slavery upon one cause of the Civil War.

- Compare and contrast two themes within Pride and Prejudice.

These kinds of writing assignments require you to decide both your writing topic and you claim (or thesis). Which character in the Inferno will I pick to analyze? What two themes in Pride and Prejudice will I choose to write about? Many students struggle with these types of assignments because they have to understand their subject matter well before they can intelligently choose a topic. For instance, you need a good familiarity with the characters in The Inferno before you can pick one. You have to have a solid understanding defining elements of American identity as well as 21st century culture before you can begin to connect them. This kind of writing assignment resembles riding a bike without the training wheels on. It says, “You decide what to write about.” The biggest decision, then, becomes selecting your topic and limiting it to a manageable size.

Picking and Limiting a Writing Topic

Let’s talk about both of these challenges: picking a topic and limiting it. Remember how I said these kinds of essay topics expect you to choose what to write about from a solid understanding of your subject? As you read and review your subject matter, look for things that interest you. Look for gaps, puzzling items, things that confuse you, or connections you see. Something in this pile of rocks should stand out as a jewel: as being “do-able” and interesting. (You’ll write best when you write from both your head and your heart.) Whatever topic you choose, state it as a clear and interesting question. You may or may not state this essay question explicitly in the introduction of your paper (I actually recommend that you do), but it will provide direction for your paper and a focus for your claim since that claim will be your answer to this essay question. For example, if with the Dante topic you decided to write on Virgil, your essay question might be: “What is the role of Virgil toward the character of Dante in The Inferno?” The thesis statement, then, might be this: “Virgil’s predominant role as Dante’s guide through hell is as the voice of reason.” Crafting a solid essay question is well worth your time because it charts the territory of your essay and helps you declare a focused thesis statement.

Many students struggle with defining the right size for their writing project. They chart out an essay question that it would take a book to deal with adequately. You’ll know you have that kind of topic if you have already written over the required page length but only touched one quarter of the topics you planned to discuss. In this case, carve out one of those topics and make your whole paper about it. For instance, with our Dante example, perhaps you planned to discuss four places where Virgil’s role as the voice of reason is evident. Instead of discussing all four, focus your essay on just one place. So your revised thesis statement might be: “Close inspection of Cantos I and II reveal that Virgil serves predominantly as the voice of reason for Dante on his journey through hell.” A writing teacher I had in college said it this way: A well tended garden is better than a large one full of weeds. That means to limit your topic to a size you can handle and support well.

Three Characteristics of Academic Writing

I want to wrap up this section by sharing in broad terms what the expectations are behind an academic writing assignment. Chris Thaiss and Terry Zawacki conducted research at George Mason University where they asked professors from their university what they thought academic writing was and its standards. They came up with three characteristics:

- Clear evidence in writing that the writer(s) have been persistent, open-minded, and disciplined in study. (5)

- The dominance of reason over emotions or sensual perception. (5)

- An imagined reader who is coolly rational, reading for information, and intending to formulate a reasoned response. (7)

Your professor wants to see these three things in your writing when they give you a writing assignment. They want to see in your writing the results of your efforts at the various literacy tasks we have been discussing: critical reading, research, and analysis. Beyond merely stat ing opinions, they also want to see an argument toward an intelligent audience where you provide good reasons to support your interpretations.

The Format of the Academic Essay

Your instructors will also expect you to deliver a paper that contains particular textual features. The following list contains the characteristics of what I have for years called the “critical essay.” Although I can’t claim they will be useful for all essays in college, I hope that these features will help you shape and accomplish successful college essays. Be aware that these characteristics are flexible and not a formula, and any particular assignment might ask for something different.

Characteristics of the Critical Essay

“Critical” here is not used in the sense of “to criticize” as in find fault with. Instead, “critical” is used in the same way “critical thinking” is used. A synonym might be “interpretive” or “analytical.”

- It is an argument, persuasion essay that in its broadest sense MAKES A POINT and SUPPORTS IT. (We have already discussed this argumentative nature of academic writing at length.)

- The point (“claim” or “thesis”) of a critical essay is interpretive in nature. That means the point is debatable and open to interpretation, not a statement of the obvious. The thesis statement is a clear, declarative sentence that often works best when it comes at the end of the introduction.

- Organization: Like any essay, the critical essay should have a clear introduction, body, and conclusion. As you support your point in the body of the essay, you should “divide up the proof,” which means structuring the body around clear primary supports (developed in single paragraphs for short papers or multiple paragraphs for longer papers).

- Support: (a) The primary source for support in the critical es- say is from the text (or sources). The text is the authority, so using quotations is required. ( b) The continuous movement of logic in a critical essay is “assert then support; assert then support.” No assertion (general statement that needs proving) should be left without specific support (often from the text(s)).

- A critical essay will always “document” its sources, distinguishing the use of outside information used inside your text and clarifying where that information came from (following the rules of MLA documentation style or whatever documentation style is required).

- Whenever the author moves from one main point (primary support) to the next, the author needs to clearly signal to the reader that this movement is happening. This transition sentence works best when it links back to the thesis as it states the topic of that paragraph or section.

- A critical essay is put into an academic essay format such as the MLA or APA document format.

- Grammatical correctness: Your essay should have few if any grammatical problems. You’ll want to edit your final draft carefully before turning it in.

As we leave this discussion, I want to return to what I said was the secret for your success in writing college essays: Your success with academic writing depends upon how well you understand what you are doing as you write and then how you approach the writing task. Hopefully, you now have a better idea about the nature of the academic writing task and the expectations behind it. Knowing what you need to do won’t guarantee you an “A” on your paper—that will take a lot of thinking, hard work, and practice—but having the right orientation toward your college writing assignments is a first and important step in your eventual success.

What is an Essay?

provided by Candela Open Courses

Okay, well, in one word, an essay is an idea.

No idea; no essay.

But more than that, the best essays have original and insightful ideas.

Okay, so the first thing we need to begin an essay is an insightful idea that we wish to share with the reader.

But original and insightful ideas do not just pop up every day. Where does one find original and insightful ideas?

Let’s start here: an idea is an insight gained from either a) our personal experiences, or b) in scholarship, from synthesizing the ideas of others to create a new idea.

In this class (except for the last essay) we write personal essays ; therefore, we will focus mostly on a) personal experience as a source for our ideas.

Life teaches us lessons. We learn from our life experiences. This is how we grow as human beings. So before you start on your essays, reflect on your life experiences by employing one or more of the brainstorming strategies described in this course. Your brainstorming and prewriting assignments are important assignments because remember: no idea; no essay . Brainstorming can help you discover an idea for your essay. So, ask yourself: What lessons have I learned? What insights have I gained that I can write about and share with my reader? Your reader can learn from you.

Why do we write?

We write to improve our world; it’s that simple. We write personal essays to address the most problematic and fundamental question of all: What does it mean to be a human being? By sharing the insights and lessons we have learned from our life experiences we can add to our community’s collective wisdom.

We respect the writings of experts. And, guess what; you are an expert! You are the best expert of all on one subject— your own life experiences . So when we write personal essays, we research our own life experiences and describe those experiences with rich and compelling language to convince our reader that our idea is valid.

For example:

For your Narrative essay : do more than simply relate a series of events. Let the events make a point about the central idea you are trying to teach us.

For your Example essay : do more than tell us about your experience. Show us your experience. Describe your examples in descriptive details so that your reader actually experiences for themselves the central idea you wish to teach them.

For the Comparison Contrast essay : do more than simply tell us about the differences and similarities of two things. Evaluate those differences and similarities and draw an idea about them, so that you can offer your reader some basic insight into the comparison.

Critical Thinking in College Writing: From the Personal to the Academic

by Gita DasBender

There is something about the term “ critical thinking ” that makes you draw a blank every time you think about what it means.* It seems so fuzzy and abstract that you end up feeling uncomfortable, as though the term is thrust upon you, demanding an intellectual effort that you may not yet have. But you know it requires you to enter a realm of smart, complex ideas that others have written about and that you have to navigate, understand, and interact with just as intelligently. It’s a lot to ask for. It makes you feel like a stranger in a strange land.

As a writing teacher I am accustomed to reading and responding to difficult texts. In fact, I like grappling with texts that have interesting ideas no matter how complicated they are because I understand their value. I have learned through my years of education that what ultimately engages me, keeps me enthralled, is not just grammatically pristine, fluent writing, but writing that forces me to think beyond the page. It is writing where the writer has challenged herself and then offered up that challenge to the reader, like a baton in a relay race. The idea is to run with the baton.

You will often come across critical thinking and analysis as requirements for assignments in writing and upper-level courses in a variety of disciplines. Instructors have varying explanations of what they actually require of you, but, in general, they expect you to respond thoughtfully to texts you have read. The first thing you should remember is not to be afraid of critical thinking. It does not mean that you have to criticize the text, disagree with its premise, or attack the writer simply because you feel you must. Criticism is the process of responding to and evaluating ideas, argument, and style so that readers understand how and why you value these items.

Critical thinking is also a process that is fundamental to all disciplines. While in this essay I refer mainly to critical thinking in composition, the general principles behind critical thinking are strikingly similar in other fields and disciplines. In history, for instance, it could mean examining and analyzing primary sources in order to understand the context in which they were written. In the hard sciences, it usually involves careful reasoning, making judgments and decisions, and problem-solving. While critical thinking may be subject-specific, that is to say, it can vary in method and technique depending on the discipline, most of its general principles such as rational thinking, making independent evaluations and judgments, and a healthy skepticism of what is being read, are common to all disciplines. No matter the area of study, the application of critical thinking skills leads to clear and flexible thinking and a better understanding of the subject at hand.

To be a critical thinker you not only have to have an informed opinion about the text but also a thoughtful response to it. There is no doubt that critical thinking is serious thinking, so here are some steps you can take to become a serious thinker and writer.

Attentive Reading: A Foundation for Critical Thinking

A critical thinker is always a good reader because to engage critically with a text you have to read attentively and with an open mind, absorbing new ideas and forming your own as you go along. Let us imagine you are reading an essay by Annie Dillard, a famous essayist, called “Living like Weasels.” Students are drawn to it because the idea of the essay appeals to something personally fundamental to all of us: how to live our lives. It is also a provocative essay that pulls the reader into the argument and forces a reaction, a good criterion for critical thinking. So let’s say that in reading the essay you encounter a quote that gives you pause. In describing her encounter with a weasel in Hollins Pond, Dillard says, “I would like to learn, or remember, how to live . . . I don’t think I can learn from a wild animal how to live in particular

. . . but I might learn something of mindlessness, something of the purity of living in the physical senses and the dignity of living without bias or motive” (220). You may not be familiar with language like this. It seems complicated, and you have to stop ever so often (perhaps after every phrase) to see if you understood what Dillard means. You may ask yourself these questions:

- What does “mindlessness” mean in this context?

- How can one “learn something of mindlessness?”

- What does Dillard mean by “purity of living in the physical senses?”

- How can one live “without bias or motive?”

These questions show that you are an attentive reader. Instead of simply glossing over this important passage, you have actually stopped to think about what the writer means and what she expects you to get from it. Here is how I read the quote and try to answer the questions above: Dillard proposes a simple and uncomplicated way of life as she looks to the animal world for inspiration. It is ironic that she admires the quality of “mindlessness” since it is our consciousness, our very capacity to think and reason, which makes us human, which makes us beings of a higher order. Yet, Dillard seems to imply that we need to live instinctually, to be guided by our senses rather than our intellect. Such a “thoughtless” approach to daily living, according to Dillard, would mean that our actions would not be tainted by our biases or motives, our prejudices. We would go back to a primal way of living, like the weasel she observes. It may take you some time to arrive at this understanding on your own, but it is important to stop, reflect, and ask questions of the text whenever you feel stumped by it. Often such questions will be helpful during class discussions and peer review sessions.

When reading any essay, keep track of all the important points the writer makes by jotting down a list of ideas or quotations in a notebook. This list not only allows you to remember ideas that are central to the writer’s argument, ideas that struck you in some way or the other, but it also you helps you to get a good sense of the whole reading assignment point by point. In reading Annie Dillard’s essay, we come across several points that contribute toward her proposal for better living and that help us get a better understanding of her main argument. Here is a list of some of her ideas that struck me as important:

- “The weasel lives in necessity and we live in choice, hating necessity and dying at the last ignobly in its talons” (220).

- “And I suspect that for me the way is like the weasel’s: open to time and death painlessly, noticing everything, remembering nothing, choosing the given with a fierce and pointed will” (221).

- “We can live any way we want. People take vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience—even of silence—by choice. The thing is to stalk your calling in a certain skilled and supple way, to locate the most tender and live spot and plug into that pulse” (221).

- “A weasel doesn’t ‘attack’ anything; a weasel lives as he’s meant to, yielding at every moment to the perfect freedom of single necessity” (221).

- “I think it would be well, and proper, and obedient, and pure, to grasp your one necessity and not let it go, to dangle from it limp wherever it takes you” (221).

These quotations give you a cumulative sense of what Dillard is trying to get at in her essay, that is, they lay out the elements with which she builds her argument. She first explains how the weasel lives, what she learns from observing the weasel, and then prescribes a lifestyle she admires—the central concern of her essay.

Noticing Key Terms and Summarizing Important Quotes

Within the list of quotations above are key terms and phrases that are critical to your understanding of the ideal life as Dillard describes it. For instance, “mindlessness,” “instinct,” “perfect freedom of a single necessity,” “stalk your calling,” “choice,” and “fierce and pointed will” are weighty terms and phrases, heavy with meaning, that you need to spend time understanding. You also need to understand the relationship between them and the quotations in which they appear. This is how you might work on each quotation to get a sense of its meaning and then come up with a statement that takes the key terms into account and expresses a general understanding of the text:

Quote 1 : Animals (like the weasel) live in “necessity,” which means that their only goal in life is to survive. They don’t think about how they should live or what choices they should make like humans do. According to Dillard, we like to have options and resist the idea of “necessity.” We fight death—an inevitable force that we have no control over—and yet ultimately surrender to it as it is the necessary end of our lives.

Quote 2 : Dillard thinks the weasel’s way of life is the best way to live. It implies a pure and simple approach to life where we do not worry about the passage of time or the approach of death. Like the weasel, we should live life in the moment, intensely experiencing everything but not dwelling on the past. We should accept our condition, what we are “given,” with a “fierce and pointed will.” Perhaps this means that we should pursue our one goal, our one passion in life, with the same single-minded determination and tenacity that we see in the weasel.

Quote 3 : As humans, we can choose any lifestyle we want. The trick, however, is to go after our one goal, one passion like a stalker would after a prey.

Quote 4 : While we may think that the weasel (or any animal) chooses to attack other animals, it is really only surrendering to the one thing it knows: its need to live. Dillard tells us there is “the perfect freedom” in this desire to survive because to her, the lack of options (the animal has no other option than to fight to survive) is the most liberating of all.

Quote 5 : Dillard urges us to latch on to our deepest passion in life (the “one necessity”) with the tenacity of a weasel and not let go. Perhaps she’s telling us how important it is to have an unwavering focus or goal in life.

Writing a Personal Response: Looking Inward

Dillard’s ideas will have certainly provoked a response in your mind, so if you have some clear thoughts about how you feel about the essay this is the time to write them down. As you look at the quotes you have selected and your explanation of their meaning, begin to create your personal response to the essay. You may begin by using some of these strategies:

1. Tell a story. Has Dillard’s essay reminded you of an experience you have had? Write a story in which you illustrate a point that Dillard makes or hint at an idea that is connected to her essay.

2. Focus on an idea from Dillard’s essay that is personally important to you. Write down your thoughts about this idea in a first-person narrative and explain your perspective on the issue.

3. If you are uncomfortable writing a personal narrative or using “I” (you should not be), reflect on some of her ideas that seem important and meaningful in general. Why were you struck by these ideas?

4. Write a short letter to Dillard in which you speak to her about the essay. You may compliment her on some of her ideas by explaining why you like them, ask her a question related to her essay and explain why that question came to you, and genuinely start up a conversation with her.

This stage in critical thinking is important for establishing your relationship with a text . What do I mean by this “relationship,” you may ask? Simply put, it has to do with how you feel about the text. Are you amazed by how true the ideas seem to be, how wise Dillard sounds? Or are you annoyed by Dillard’s let-me-tell-you-how-to-live approach and disturbed by the impractical ideas she so easily prescribes? Do you find Dillard’s voice and style thrilling and engaging or merely confus ing? No matter which of the personal response options you select, your initial reaction to the text will help shape your views about it.

Making an Academic Connection: Looking Outward

First-year writing courses are designed to teach a range of writing— from the personal to the academic—so that you can learn to express advanced ideas, arguments, concepts, or theories in any discipline. While the example I have been discussing pertains mainly to college writing, the method of analysis and approach to critical thinking I have demonstrated here will serve you well in a variety of disciplines. Since critical thinking and analysis are key elements of the reading and writing you will do in college, it is important to understand how they form a part of academic writing. No matter how intimidating the term “academic writing” may seem (it is, after all, associated with advanced writing and becoming an expert in a field of study), embrace it not as a temporary college requirement but as a habit of mind.

To some, academic writing often implies impersonal writing , writing that is detached, distant, and lacking in personal meaning or relevance. However, this is often not true of the academic writing you will do in a composition class. Here your presence as a writer—your thoughts, experiences, ideas, and therefore who you are—is of much significance to the writing you produce. In fact, it would not be far-fetched to say that in a writing class academic writing often begins with personal writing. Let me explain. If critical thinking begins with a personal view of the text, academic writing helps you broaden that view by going beyond the personal to a more universal point of view. In other words, academic writing often has its roots in one’s private opinion or perspective about another writer’s ideas but ultimately goes beyond this opinion to the expression of larger, more abstract ideas. Your personal vision—your core beliefs and general approach to life— will help you arrive at these “larger ideas” or universal propositions that any reader can understand and be enlightened by, if not agree with. In short, academic writing is largely about taking a critical, analytical stance toward a subject in order to arrive at some compelling conclusions.

Let us now think about how you might apply your critical thinking skills to move from a personal reaction to a more formal academic response to Annie Dillard’s essay. The second stage of critical thinking involves textual analysis and requires you to do the following:

• Summarize the writer’s ideas the best you can in a brief paragraph. This provides the basis for extended analysis since it contains the central ideas of the piece, the building blocks, so to speak.

• Evaluate the most important ideas of the essay by considering their merits or flaws, their worthiness or lack of worthiness. Do not merely agree or disagree with the ideas but explore and explain why you believe they are socially, politically, philosophically, or historically important and relevant, or why you need to question, challenge, or reject them.

• Identify gaps or discrepancies in the writer’s argument. Does she contradict herself? If so, explain how this contradiction forces you to think more deeply about her ideas. Or if you are confused, explain what is confusing and why.

• Examine the strategies the writer uses to express her ideas. Look particularly at her style, voice, use of figurative language, and the way she structures her essay and organizes her ideas. Do these strategies strengthen or weaken her argument? How?

• Include a second text—an essay, a poem, lyrics of a song— whose ideas enhance your reading and analysis of the primary text. This text may help provide evidence by supporting a point you’re making, and further your argument.

• Extend the writer’s ideas, develop your own perspective, and propose new ways of thinking about the subject at hand.

Crafting the Essay

Once you have taken notes and developed a thorough understanding of the text, you are on your way to writing a good essay. If you were asked to write an exploratory essay, a personal response to Dillard’s essay would probably suffice. However, an academic writing assignment requires you to be more critical. As counter-intuitive as it may sound, beginning your essay with a personal anecdote often helps to establish your relationship to the text and draw the reader into your writing. It also helps to ease you into the more complex task of textual analysis. Once you begin to analyze Dillard’s ideas, go back to the list of important ideas and quotations you created as you read the essay. After a brief summary, engage with the quotations that are most important, that get to the heart of Dillard’s ideas, and explore their meaning. Textual engagement, a seemingly slippery concept, simply means that you respond directly to some of Dillard’s ideas, examine the value of Dillard’s assertions, and explain why they are worthwhile or why they should be rejected. This should help you to transition into analysis and evaluation. Also, this part of your essay will most clearly reflect your critical thinking abilities as you are expected not only to represent Dillard’s ideas but also to weigh their significance. Your observations about the various points she makes, analysis of conflicting viewpoints or contradictions, and your understanding of her general thesis should now be synthesized into a rich new idea about how we should live our lives. Conclude by explaining this fresh point of view in clear, compel- ling language and by rearticulating your main argument.

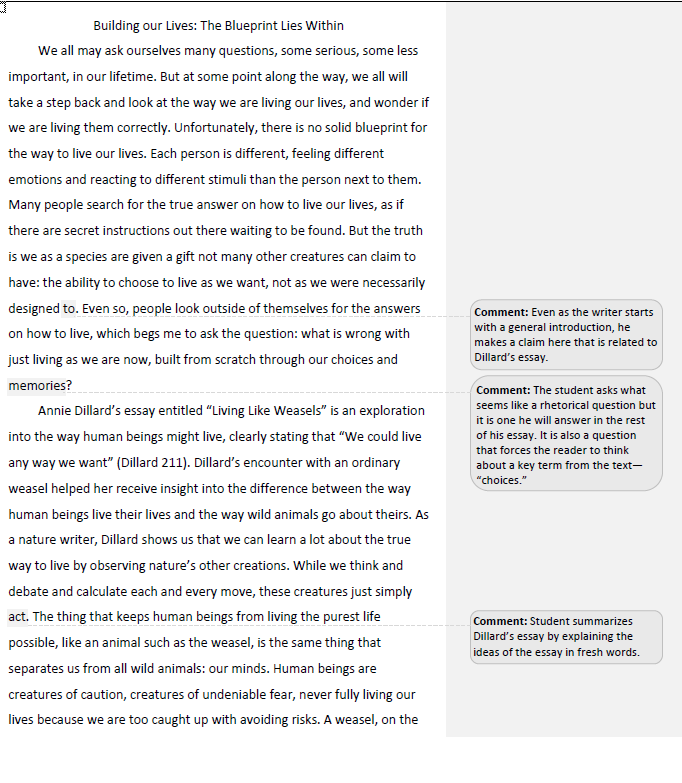

Modeling Good Writing

When I teach a writing class, I often show students samples of really good writing that I’ve collected over the years. I do this for two reasons: first, to show students how another freshman writer understood and responded to an assignment that they are currently working on; and second, to encourage them to succeed as well. I explain that although they may be intimidated by strong, sophisticated writing and feel pressured to perform similarly, it is always helpful to see what it takes to get an A. It also helps to follow a writer’s imagination, to learn how the mind works when confronted with a task involving critical thinking. The following sample is a response to the Annie Dillard essay. Figure 1 includes the entire student essay and my comments are inserted into the text to guide your reading.

Though this student has not included a personal narrative in his essay, his own world-view is clear throughout. His personal point of view, while not expressed in first person statements, is evident from the very beginning. So we could say that a personal response to the text need not always be expressed in experiential or narrative form but may be present as reflection, as it is here. The point is that the writer has traveled through the rough terrain of critical thinking by starting out with his own ruminations on the subject, then by critically analyzing and responding to Dillard’s text, and finally by developing a strong point of view of his own about our responsibility as human beings. As readers, we are engaged by clear, compelling writing and riveted by critical thinking that produces a movement of ideas that give the essay depth and meaning. The challenge Dillard set forth in her essay has been met and the baton passed along to us.

Important Concepts

writing in college

critical literacy

closed writing assignment

semi-open writing assignment

open writing assignment

example essay

comparison contrast essay

critical thinking

relationship with a text

first-year writing courses are designed to teach a range of writing— from the personal to the academic—so that you can learn to express advanced ideas, arguments, concepts, or theories in any discipline

impersonal writing

Licenses and Attributions

CC LICENSED CONTENT, ORIGINAL

Composing Ourselves and Our World, Provided by: the authors. License: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

CC LICENSED CONTENT INCLUDED

This chapter contains an adaptation of What Is Academic Writing? : by Lenny L Irvin, and is used under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 US) license.

The chapter also contains an adaptation of English Composition 1 Provided by : Lumen Learning. Located at : http://lumenlearning.com/ . License : CC BY: Attribution Authored by : Paul Powell. Provided by : Central Community College. Project : Kaleidoscope Open Course Initiative. License : CC BY: Attribution

This chapter contains an excerpt from Critical Thinking in College Writing: From the Personal to the Academic by Gita DasBender.

MULTIMEDIA CONTENT INCLUDED

- Video 1: 7 Tips for Effective Academic Writing by KeeleStudentLearning . Licensed: Creative Commons Attribution license (reuse allowed)

- Image 1: License: CC0 “No Rights Reserved”

- Image of blank journal. Authored by : Sembazuru. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/BKeN . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Image of Idea. Authored by : Mike Linksvayer. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/bD6jZH . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Works Cited

Carroll, Lee Ann. Rehearsing New Roles: How College Students Develop as Writers. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2002. Print.

Thaiss, Chris and Terry Zawacki.

Engaged Writers & Dynamic Disciplines: Research on the Academic Writing Life. Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook, 2006.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Academic Writing Style

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

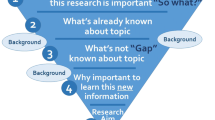

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Academic writing refers to a style of expression that researchers use to define the intellectual boundaries of their disciplines and specific areas of expertise. Characteristics of academic writing include a formal tone, use of the third-person rather than first-person perspective (usually), a clear focus on the research problem under investigation, and precise word choice. Like specialist languages adopted in other professions, such as, law or medicine, academic writing is designed to convey agreed meaning about complex ideas or concepts within a community of scholarly experts and practitioners.

Academic Writing. Writing Center. Colorado Technical College; Hartley, James. Academic Writing and Publishing: A Practical Guide . New York: Routledge, 2008; Ezza, El-Sadig Y. and Touria Drid. T eaching Academic Writing as a Discipline-Specific Skill in Higher Education . Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2020.

Importance of Good Academic Writing

The accepted form of academic writing in the social sciences can vary considerable depending on the methodological framework and the intended audience. However, most college-level research papers require careful attention to the following stylistic elements:

I. The Big Picture Unlike creative or journalistic writing, the overall structure of academic writing is formal and logical. It must be cohesive and possess a logically organized flow of ideas; this means that the various parts are connected to form a unified whole. There should be narrative links between sentences and paragraphs so that the reader is able to follow your argument. The introduction should include a description of how the rest of the paper is organized and all sources are properly cited throughout the paper.

II. Tone The overall tone refers to the attitude conveyed in a piece of writing. Throughout your paper, it is important that you present the arguments of others fairly and with an appropriate narrative tone. When presenting a position or argument that you disagree with, describe this argument accurately and without loaded or biased language. In academic writing, the author is expected to investigate the research problem from an authoritative point of view. You should, therefore, state the strengths of your arguments confidently, using language that is neutral, not confrontational or dismissive.

III. Diction Diction refers to the choice of words you use. Awareness of the words you use is important because words that have almost the same denotation [dictionary definition] can have very different connotations [implied meanings]. This is particularly true in academic writing because words and terminology can evolve a nuanced meaning that describes a particular idea, concept, or phenomenon derived from the epistemological culture of that discipline [e.g., the concept of rational choice in political science]. Therefore, use concrete words [not general] that convey a specific meaning. If this cannot be done without confusing the reader, then you need to explain what you mean within the context of how that word or phrase is used within a discipline.

IV. Language The investigation of research problems in the social sciences is often complex and multi- dimensional . Therefore, it is important that you use unambiguous language. Well-structured paragraphs and clear topic sentences enable a reader to follow your line of thinking without difficulty. Your language should be concise, formal, and express precisely what you want it to mean. Do not use vague expressions that are not specific or precise enough for the reader to derive exact meaning ["they," "we," "people," "the organization," etc.], abbreviations like 'i.e.' ["in other words"], 'e.g.' ["for example"], or 'a.k.a.' ["also known as"], and the use of unspecific determinate words ["super," "very," "incredible," "huge," etc.].

V. Punctuation Scholars rely on precise words and language to establish the narrative tone of their work and, therefore, punctuation marks are used very deliberately. For example, exclamation points are rarely used to express a heightened tone because it can come across as unsophisticated or over-excited. Dashes should be limited to the insertion of an explanatory comment in a sentence, while hyphens should be limited to connecting prefixes to words [e.g., multi-disciplinary] or when forming compound phrases [e.g., commander-in-chief]. Finally, understand that semi-colons represent a pause that is longer than a comma, but shorter than a period in a sentence. In general, there are four grammatical uses of semi-colons: when a second clause expands or explains the first clause; to describe a sequence of actions or different aspects of the same topic; placed before clauses which begin with "nevertheless", "therefore", "even so," and "for instance”; and, to mark off a series of phrases or clauses which contain commas. If you are not confident about when to use semi-colons [and most of the time, they are not required for proper punctuation], rewrite using shorter sentences or revise the paragraph.

VI. Academic Conventions Among the most important rules and principles of academic engagement of a writing is citing sources in the body of your paper and providing a list of references as either footnotes or endnotes. The academic convention of citing sources facilitates processes of intellectual discovery, critical thinking, and applying a deliberate method of navigating through the scholarly landscape by tracking how cited works are propagated by scholars over time . Aside from citing sources, other academic conventions to follow include the appropriate use of headings and subheadings, properly spelling out acronyms when first used in the text, avoiding slang or colloquial language, avoiding emotive language or unsupported declarative statements, avoiding contractions [e.g., isn't], and using first person and second person pronouns only when necessary.

VII. Evidence-Based Reasoning Assignments often ask you to express your own point of view about the research problem. However, what is valued in academic writing is that statements are based on evidence-based reasoning. This refers to possessing a clear understanding of the pertinent body of knowledge and academic debates that exist within, and often external to, your discipline concerning the topic. You need to support your arguments with evidence from scholarly [i.e., academic or peer-reviewed] sources. It should be an objective stance presented as a logical argument; the quality of the evidence you cite will determine the strength of your argument. The objective is to convince the reader of the validity of your thoughts through a well-documented, coherent, and logically structured piece of writing. This is particularly important when proposing solutions to problems or delineating recommended courses of action.

VIII. Thesis-Driven Academic writing is “thesis-driven,” meaning that the starting point is a particular perspective, idea, or position applied to the chosen topic of investigation, such as, establishing, proving, or disproving solutions to the questions applied to investigating the research problem. Note that a problem statement without the research questions does not qualify as academic writing because simply identifying the research problem does not establish for the reader how you will contribute to solving the problem, what aspects you believe are most critical, or suggest a method for gathering information or data to better understand the problem.

IX. Complexity and Higher-Order Thinking Academic writing addresses complex issues that require higher-order thinking skills applied to understanding the research problem [e.g., critical, reflective, logical, and creative thinking as opposed to, for example, descriptive or prescriptive thinking]. Higher-order thinking skills include cognitive processes that are used to comprehend, solve problems, and express concepts or that describe abstract ideas that cannot be easily acted out, pointed to, or shown with images. Think of your writing this way: One of the most important attributes of a good teacher is the ability to explain complexity in a way that is understandable and relatable to the topic being presented during class. This is also one of the main functions of academic writing--examining and explaining the significance of complex ideas as clearly as possible. As a writer, you must adopt the role of a good teacher by summarizing complex information into a well-organized synthesis of ideas, concepts, and recommendations that contribute to a better understanding of the research problem.

Academic Writing. Writing Center. Colorado Technical College; Hartley, James. Academic Writing and Publishing: A Practical Guide . New York: Routledge, 2008; Murray, Rowena and Sarah Moore. The Handbook of Academic Writing: A Fresh Approach . New York: Open University Press, 2006; Johnson, Roy. Improve Your Writing Skills . Manchester, UK: Clifton Press, 1995; Nygaard, Lynn P. Writing for Scholars: A Practical Guide to Making Sense and Being Heard . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2015; Silvia, Paul J. How to Write a Lot: A Practical Guide to Productive Academic Writing . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2007; Style, Diction, Tone, and Voice. Writing Center, Wheaton College; Sword, Helen. Stylish Academic Writing . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Strategies for...

Understanding Academic Writing and Its Jargon

The very definition of research jargon is language specific to a particular community of practitioner-researchers . Therefore, in modern university life, jargon represents the specific language and meaning assigned to words and phrases specific to a discipline or area of study. For example, the idea of being rational may hold the same general meaning in both political science and psychology, but its application to understanding and explaining phenomena within the research domain of a each discipline may have subtle differences based upon how scholars in that discipline apply the concept to the theories and practice of their work.

Given this, it is important that specialist terminology [i.e., jargon] must be used accurately and applied under the appropriate conditions . Subject-specific dictionaries are the best places to confirm the meaning of terms within the context of a specific discipline. These can be found by either searching in the USC Libraries catalog by entering the disciplinary and the word dictionary [e.g., sociology and dictionary] or using a database such as Credo Reference [a curated collection of subject encyclopedias, dictionaries, handbooks, guides from highly regarded publishers] . It is appropriate for you to use specialist language within your field of study, but you should avoid using such language when writing for non-academic or general audiences.

Problems with Opaque Writing

A common criticism of scholars is that they can utilize needlessly complex syntax or overly expansive vocabulary that is impenetrable or not well-defined. When writing, avoid problems associated with opaque writing by keeping in mind the following:

1. Excessive use of specialized terminology . Yes, it is appropriate for you to use specialist language and a formal style of expression in academic writing, but it does not mean using "big words" just for the sake of doing so. Overuse of complex or obscure words or writing complicated sentence constructions gives readers the impression that your paper is more about style than substance; it leads the reader to question if you really know what you are talking about. Focus on creating clear, concise, and elegant prose that minimizes reliance on specialized terminology.

2. Inappropriate use of specialized terminology . Because you are dealing with concepts, research, and data within your discipline, you need to use the technical language appropriate to that area of study. However, nothing will undermine the validity of your study quicker than the inappropriate application of a term or concept. Avoid using terms whose meaning you are unsure of--do not just guess or assume! Consult the meaning of terms in specialized, discipline-specific dictionaries by searching the USC Libraries catalog or the Credo Reference database [see above].

Additional Problems to Avoid

In addition to understanding the use of specialized language, there are other aspects of academic writing in the social sciences that you should be aware of. These problems include:

- Personal nouns . Excessive use of personal nouns [e.g., I, me, you, us] may lead the reader to believe the study was overly subjective. These words can be interpreted as being used only to avoid presenting empirical evidence about the research problem. Limit the use of personal nouns to descriptions of things you actually did [e.g., "I interviewed ten teachers about classroom management techniques..."]. Note that personal nouns are generally found in the discussion section of a paper because this is where you as the author/researcher interpret and describe your work.

- Directives . Avoid directives that demand the reader to "do this" or "do that." Directives should be framed as evidence-based recommendations or goals leading to specific outcomes. Note that an exception to this can be found in various forms of action research that involve evidence-based advocacy for social justice or transformative change. Within this area of the social sciences, authors may offer directives for action in a declarative tone of urgency.

- Informal, conversational tone using slang and idioms . Academic writing relies on excellent grammar and precise word structure. Your narrative should not include regional dialects or slang terms because they can be open to interpretation. Your writing should be direct and concise using standard English.

- Wordiness. Focus on being concise, straightforward, and developing a narrative that does not have confusing language . By doing so, you help eliminate the possibility of the reader misinterpreting the design and purpose of your study.