Study at Cambridge

About the university, research at cambridge.

- Events and open days

- Fees and finance

- Student blogs and videos

- Why Cambridge

- Qualifications directory

- How to apply

- Fees and funding

- Frequently asked questions

- International students

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

- How the University and Colleges work

- Visiting the University

- Term dates and calendars

- Video and audio

- Find an expert

- Publications

- International Cambridge

- Public engagement

- Giving to Cambridge

- For current students

- For business

- Colleges & departments

- Libraries & facilities

- Museums & collections

- Email & phone search

- The Letters

- Darwin's life in letters

Darwin in letters, 1844–1846: Building a scientific network

Darwin correspondence project.

- About Darwin overview

- Family life overview

- Darwin on childhood

- Darwin on marriage

- Darwin’s observations on his children

- Darwin and fatherhood

- The death of Annie Darwin

- Visiting the Darwins

- Voyage of HMS Beagle

- What Darwin read overview

- Darwin’s student booklist

- Books on the Beagle

- Darwin’s reading notebooks

- On the Origin of Species overview

- The writing of "Origin"

- Abstract of Darwin’s theory

- Alfred Russel Wallace’s essay on varieties

- Charles Darwin and his publisher

- Review: The Origin of Species

- Darwin's notes for his physician, 1865

- Darwin’s photographic portraits

- Have you read the one about....

- Six things Darwin never said – and one he did overview

- The evolution of a misquotation

- Portraits of Charles Darwin: a catalogue overview

- 1.1 Ellen Sharples pastel

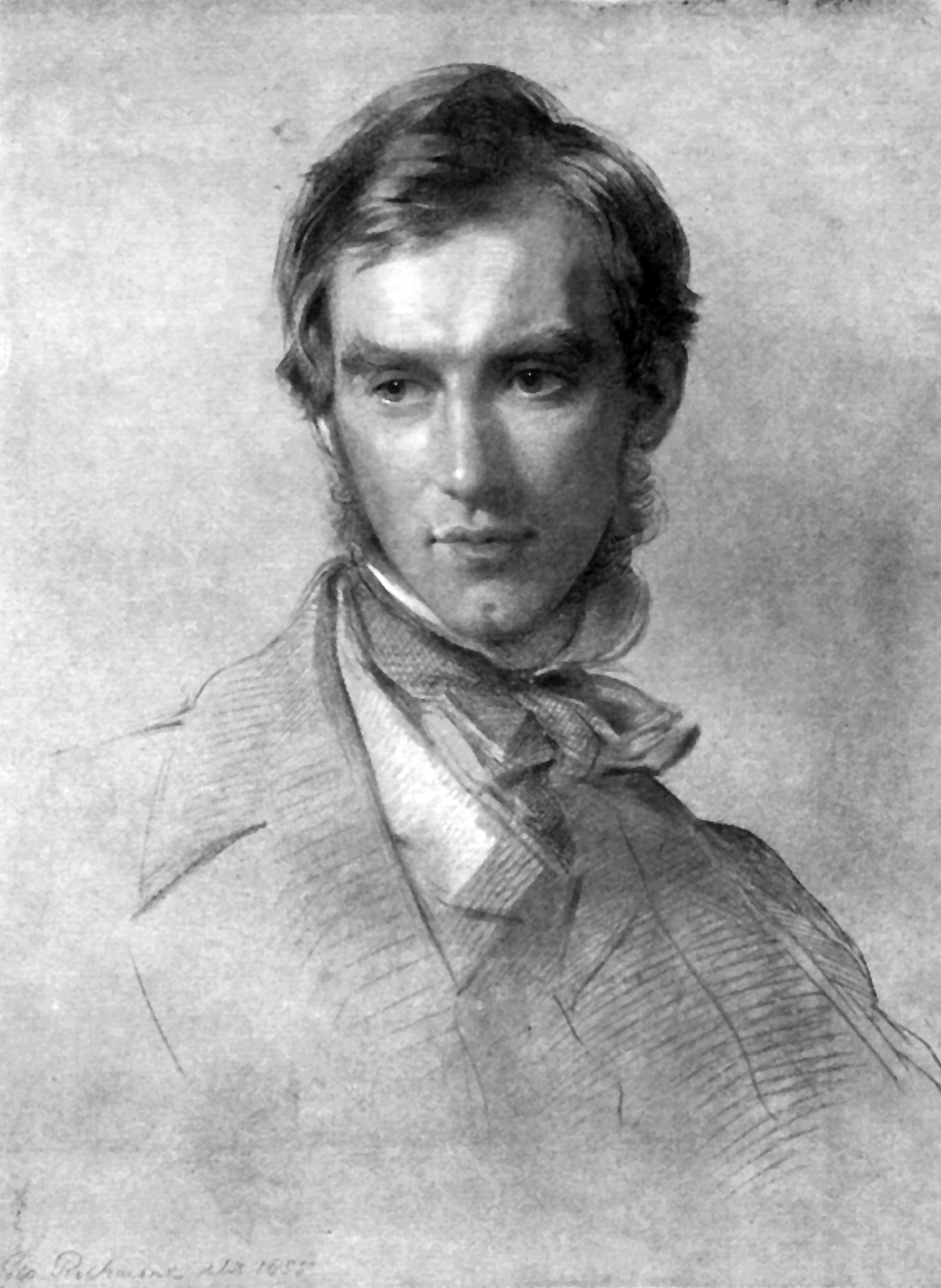

- 1.2 George Richmond, marriage portrait

- 1.3 Thomas Herbert Maguire, lithograph

- 1.4 Samuel Laurence drawing 1

- 1.5 Samuel Laurence drawing 2

- 1.6 Ouless oil portrait

- 1.7 Ouless replica

- 1.8 anonymous drawing, after Ouless

- 1.9 Rajon, etching after Ouless

- 1.10 Rajon etching, variant state

- 1.11 Laura Russell, oil

- 1.12 Marian Huxley, drawing

- 1.13 Louisa Nash, drawing

- 1.14 William Richmond, oil

- 1.15 Albert Goodwin, watercolour

- 1.16 Alphonse Legros, drypoint

- 1.17 Alphonse Legros drawing

- 1.18 John Collier, oil in Linnean

- 1.19 John Collier, oil in NPG

- 1.20 Leopold Flameng etching, after Collier

- 1.21 window at Christ's College Cambridge

- 2.1 Thomas Woolner bust

- 2.2 Thomas Woolner metal plaque

- 2.3 Wedgwood medallions

- 2.4 Wedgwood plaque

- 2.5 Wedgwood medallions, 2nd type

- 2.6 Adolf von Hildebrand bust

- 2.7 Joseph Moore, Midland Union medal

- 2.8 Alphonse Legros medallion

- 2.9 Legros medallion, plaster model

- 2.10 Moritz Klinkicht, print from Legros

- 2.11 Christian Lehr, plaster bust

- 2.12 Allan Wyon, Royal Society medal

- 2.13 Edgar Boehm, statue in the NHM

- 2.14 Boehm, Westminster Abbey roundel

- 2.15 Boehm terracotta bust (NPG)

- 2.16 Horace Montford statue, Shrewsbury

- 2.17 Montford, statuette

- 2.18 Montford, Carnegie bust

- 2.19 Montford, bust at the Royal Society

- 2.20 Montford, terracotta bust, NPG

- 2.21 Montford, relief at Christ's College

- 2.22 L.-J. Chavalliaud statue in Liverpool

- 2.23 Hope Pinker statue, Oxford Museum

- 2.24 Herbert Hampton statue, Lancaster

- 2.25 Henry Pegram statue, Birmingham

- 2.26 Linnean Society medal

- 2.27 William Couper bust, New York

- 2.28 Couper bust in Cambridge

- 3.1 Antoine Claudet, daguerreotype

- 3.2 Maull and Polyblank photo 1

- 3.3 Maull and Polyblank photo 2

- 3.4 William Darwin, photo 1

- 3.5 William Darwin, photo 2

- 3.6 William Darwin, photo 3

- 3.7 Leonard Darwin, photo on verandah

- 3.8 Leonard Darwin, interior photo

- 3.9 Leonard Darwin, photo on horseback

- 3.10 Ernest Edwards, 'Men of Eminence'

- 3.11 Edwards, in Illustrated London News

- 3.12 Edwards, second group of photos

- 3.13 Edwards 'Representative Men'

- 3.14 Julia Margaret Cameron, photos

- 3.15 George Charles Wallich, photo

- 3.16 Oscar Rejlander, photos

- 3.17 Lock and Whitfield, 'Men of Mark'

- 3.18 Elliott and Fry photos, c.1869-1871

- 3.19 Elliott and Fry photos c.1880-1

- 3.20 Elliott and Fry, c.1880-1, verandah

- 3.21 Herbert Rose Barraud, photos

- 4.1 Albert Way, comic drawings

- 4.2 Augustus Earle, caricature drawing

- 4.3 Alfred Crowquill, caricature

- 4.4 Thomas Huxley, caricature sketch

- 4.5 William Beard, comic painting

- 4.6 Thomas Nast, cartoon

- 4.7 'Vanity Fair', caricature

- 4.8 'Vanity Fair', preliminary study

- 4.9 'Graphic', cartoon

- 4.10 'Hornet' caricature of Darwin

- 4.11 'Fun' cartoon, 'A little lecture'

- 4.12 'Fun', Wedding procession

- 4.13 'Fun' cartoon by Griset, 'Emotional'

- 4.14 'Fun' cartoon, 'That troubles'

- 4.15 George Cruikshank, comic drawing

- 4.16 Joseph Simms, physiognomy

- 4.17 'Figaro', unidentifiable 1871

- 4.18 'Figaro' chromolithograph 1

- 4.19 George Montbard, caricature

- 4.20 Frederick Waddy, caricature

- 4.21 Gegeef, 'Our National Church', 1

- 4.22 Gegeef et al., 'Our National Church', 2

- 4.23 Gegeef, 'Battle Field of Science'

- 4.24 'Daily Graphic', Nast satire

- 4.25 'Punch' 1877 re. Cambridge doctorate

- 4.26 Christmas card caricature, monkeys

- 4.27 'Four founders of Darwinismus'

- 4.28 'English celebrities' montage

- 4.29 Richard Grant White, 'Fall of man'

- 4.30 'La Petite Lune', Gill cartoon

- 4.31 'La Lune Rousse', Gill cartoon

- 4.32 Anis liqueur label

- 4.33 'Harper's Weekly', Bellew caricature

- 4.34 'Punch', Sambourne cartoon 1

- 4.35 Frederick Sem, caricature

- 4.36 Sem, Chistmas card

- 4.37 'Mosquito' satire

- 4.38 Franz Goedecker, caricature

- 4.39 'Moonshine' magazine cartoon

- 4.40 'Phrenological Magazine'

- 4.41 'Punch', Sambourne cartoon 2

- 4.42 'Punch' Sambourne cartoon 3

- 4.43 'Illustrated London News' article

- 4.44 'Puck' cartoon 1

- 4.45 'Puck' cartoon 2

- 4.46 'Puck' cartoon 3

- 4.47 'Puck' cartoon 4

- 4.48 'Puck', cartoon 5

- 4.49 Alfred Bryan, caricature

- 4.50 Cigar box lid design

- 4.51 Frederick Holder 'Life and Work'

- 4.52 'Wasp' caricature

- 4.53 Claud Warren, 'Outlines of Hands'

- 4.54 jubilees of Queen Victoria

- 4.55 Harry Furniss caricature

- 4.56 'Larks' cartoon

- 4.57 silhouette cartoon

- 4.58 'Simian, savage' . . . drawings

- 4.59 'Simplicissimus' cartoon

- Darwin and the experimental life overview

- What is an experiment?

- From morphology to movement: observation and experiment

- Fool's experiments

- Experimenting with emotions

- Animals, ethics, and the progress of science

- Fake Darwin: myths and misconceptions

- Darwin's bad days

- Darwin’s first love

- The letters overview

- Darwin's life in letters overview

- 1821-1836: Childhood to the Beagle voyage

- 1837-43: The London years to 'natural selection'

- 1844-1846: Building a scientific network

- 1847-1850: Microscopes and barnacles

- 1851-1855: Death of a daughter

- 1856-1857: The 'Big Book'

- 1858-1859: Origin

- 1860: Answering critics

- 1861: Gaining allies

- 1862: A multiplicity of experiments

- 1863: Quarrels at home, honours abroad

- 1864: Failing health

- 1865: Delays and disappointments

- 1866: Survival of the fittest

- 1867: A civilised dispute

- 1868: Studying sex

- 1869: Forward on all fronts

- 1870: Human evolution

- 1871: An emptying nest

- 1872: Job done?

- 1873: Animal or vegetable?

- 1874: A turbulent year

- 1875: Pulling strings

- 1876: In the midst of life

- 1877: Flowers and honours

- 1878: Movement and sleep

- 1879: Tracing roots

- 1880: Sensitivity and worms

- 1881: Old friends and new admirers

- 1882: Nothing too great or too small

- Darwin's works in letters overview

- Journal of researches

- Living and fossil cirripedia

- Before Origin: the ‘big book’ overview

- Dates of composition of Darwin's manuscript on species

- Rewriting Origin - the later editions overview

- How old is the earth?

- The whale-bear

- Origin: the lost changes for the second German edition

- Climbing plants

- Insectivorous plants

- Forms of flowers

- Cross and self fertilisation

- Life of Erasmus Darwin

- Movement in Plants

- About the letters

- Lifecycle of a letter film overview

- Editing a Letter

- Working in the Darwin archive

- Capturing Darwin’s voice: audio of selected letters

- Correspondence with women

- The hunt for new letters

- Editorial policy and practice overview

- Full notes on editorial policy

- Symbols and abbreviations

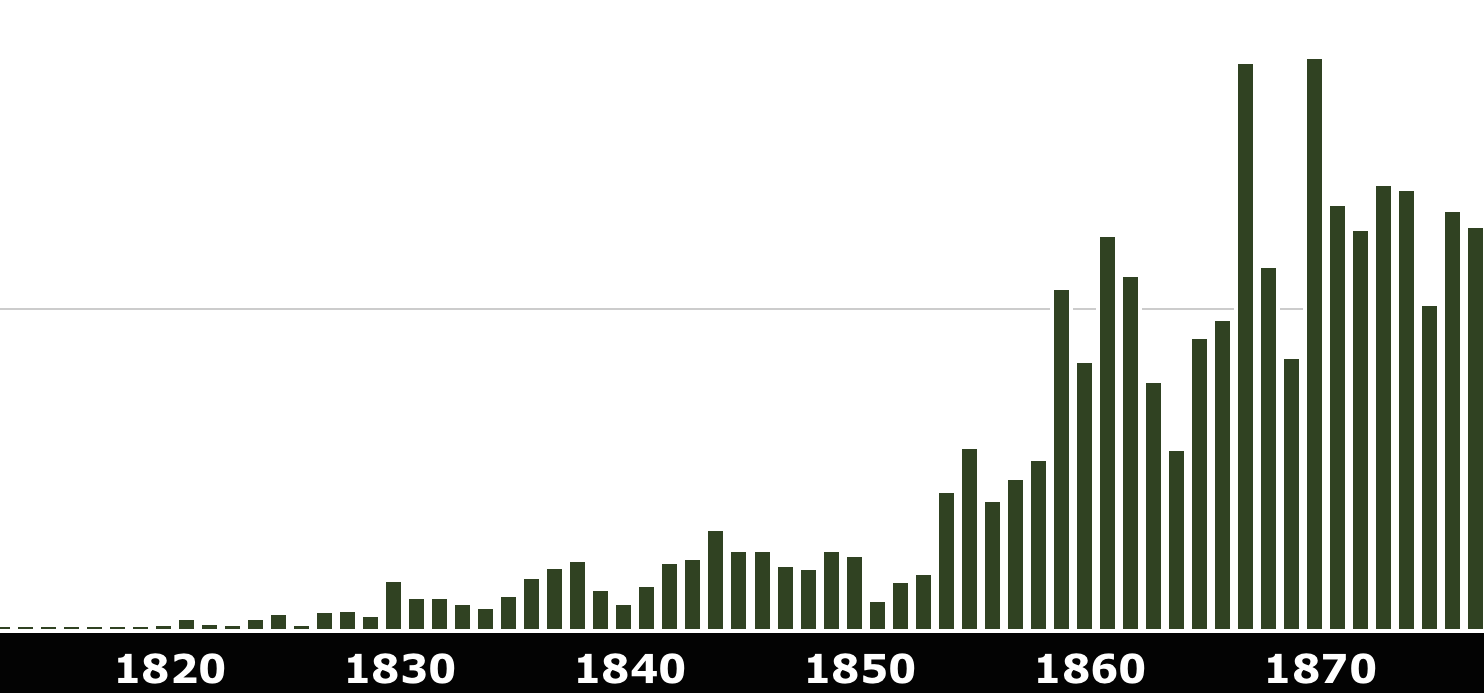

Darwin's letters: a timeline

- Darwin's letters: World Map

- Have you read the one about...

- Charles Darwin: A Life in Letters

- Darwin in Conversation exhibition

- Diagrams and drawings in letters

- Favourite Letters overview

- Be envious of ripe oranges: To W. D. Fox, May 1832

- That monstrous stain: To J. M. Herbert, 2 June 1833

- My most solemn request: To Emma Darwin, 5 July 1844

- Our poor dear dear child: To Emma Darwin, [23 April 1851]

- I beg a million pardons: To John Lubbock, [3 September 1862]

- Prize possessions: To Henry Denny, 17 January [1865]

- How to manage it: To J. D. Hooker, [17 June 1865]

- A fly on the flower: From Hermann Müller, 23 October 1867

- Reading my roommate’s illustrious ancestor: To T. H. Huxley, 10 June 1868

- A beginning, & that is something: To J. D. Hooker, [22 January 1869]

- Perfect copper-plate hand: From Adolf Reuter, 30 May 1869

- Darwin’s favourite photographer: From O. G. Rejlander, 30 April 1871

- Your letter eternalized before us: From N. D. Doedes, 27 March 1873

- Lost in translation: From Auguste Forel, 12 November 1874

- I never trusted Drosera: From E. F. Lubbock, [after 2 July] 1875

- From Argus pheasant to Mivart: To A. R. Wallace, 17 June 1876

- Wearing his knowledge lightly: From Fritz Müller, 5 April 1878

- Terms of engagement: To Julius Wiesner, 25 October 1881

- Intellectual capacities: From Caroline Kennard, 26 December 1881

- Darwin plays overview

- 'Emma' audio play

- 'Frank' audio play

- 'Like confessing a murder' audio play

- 'Re: Design' dramatisation overview

- Dramatisation script

- Browse all Darwin letters in date order

- List of correspondents

- Commentary overview

- Evolution overview

Natural selection

- Sexual selection

- Inheritance

- Correlation of growth: deaf blue-eyed cats, pigs, and poison

- Natural Selection: the trouble with terminology Part I

- Survival of the fittest: the trouble with terminology Part II

- Darwin’s species notebooks: ‘I think . . .’

- Geology overview

- Darwin and geology

- Darwin’s introduction to geology

- The geology of the Beagle voyage

- Darwin and coral reefs

- Darwin’s earthquakes

- Darwin and the Geological Society

- Darwin and Glen Roy

- Bibliography of Darwin’s geological publications

- Life sciences overview

- Darwin and Down overview

- Darwin’s hothouse and lists of hothouse plants

- Species and varieties

- The evolution of honeycomb

- A tale of two bees

- Beauty and the seed overview

- Mauro Galetti: profile of an ecologist

- Casting about: Darwin on worms

- Was Darwin an ecologist?

- Dipsacus and Drosera

- Darwin and barnacles overview

- Darwin’s study of the Cirripedia

- Darwin and vivisection overview

- Vivisection: draft petition

- Vivisection: BAAS committee report

- Vivisection: first sketch of the bill

- Vivisection: Darwin's testimony

- 'An Appeal' against animal cruelty

- Biodiversity and its histories

- Human nature overview

- Darwin on human evolution

- The expression of emotions overview

- Emotion experiment overview

- Results of the Darwin Online Emotions Experiment

- Face of emotion

- Darwin’s queries on expression

- The origin of language overview

- Language: key letters

- Language: Interview with Gregory Radick

- Film series podcasts

- Religion overview

- Darwin and design

- What did Darwin believe?

- Darwin and the Church

- British Association meeting 1860

- Darwin and religion in America

- Essays and reviews by Asa Gray overview

- Darwiniana – Preface

- Essay: Design versus necessity

- Essay: Natural selection & natural theology

- Essay: Evolution and theology

- Essay: What is Darwinism?

- Essay: Evolutionary teleology

- Science and religion Interviews overview

- Interview with Emily Ballou

- Interview with Simon Conway Morris

- Interview with John Hedley Brooke

- Interview with Randal Keynes

- Interview with Tim Lewens

- Interview with Pietro Corsi

- For the curious... overview

- Cordillera Beagle expedition

- The Darwin family

- Darwin’s plant experiments

- Behind the scenes

- Darwin’s Networks

- Darwin and the Beagle voyage

- Darwin and working from home

- Darwin, cats and cat shows

- Darwin and dogs

- Darwin's illness

- Plant or animal? (Or: Don’t try this at home!)

- Strange things sent to Darwin in the post

- People overview

- Key correspondents

- Beagle voyage networks

- Family and friends

- Darwin's scientific network

- Readers and critics

- Publishers, artists and illustrators

- People pages in alphabetical order

- German and Dutch photograph albums overview

- Photograph album of German and Austrian scientists

- Photograph album of Dutch admirers

- German poems presented to Darwin

- List of all people mentioned in letters

- Learning overview

- Ages 7-11 overview

- Darwin The Collector

- Detecting Darwin

- Darwin And Evolution

- Darwin's Fantastical Voyage

- Home learning: 7-11 years

- Ages 11-14 overview

- Darwin and Religion

- Doing Darwin’s Experiments

- How dangerous was Darwin?

- Offer of a lifetime

- Darwin and slavery

- Beagle Voyage

- Darwin’s scientific women

- Schools Gallery: Using Darwin’s letters in the classroom

- Universities overview

- Letters as a primary source overview

- Scientific networks

- Scientific practice

- Controversy

- Discussion questions and essay questions

- Suggested reading

- Getting to know Darwin's science overview

- Biogeography

- Variation under domestication

- Instinct and the evolution of mind

- Floral dimorphism

- Power of movement in plants

- Dining at Down House

- Darwin and human nature overview

- Moral nature

- Race, civilization, and progress

- Women and science overview

- Women’s scientific participation

- Women as a scientific audience

- Referencing women’s work

- Darwin in public and private

- Darwin as mentor

- Discussion questions

- Darwin timeline

- Teacher training

- Resources overview

- Historical documents

- Interactive

- About us overview

- Publications overview

- The correspondence of Charles Darwin

- Charles Darwin: the Beagle letters

- Charles Darwin’s letters: a selection 1825-1859

- Evolution: Selected Letters of Charles Darwin 1860-1870

- The correspondence 1821-60: anniversary paperback set

- A voyage round the world

- Calendars to the correspondence of Charles Darwin

- Darwin and women: a selection of letters

- Research initiatives overview

- Darwin and ecological science

- Darwin and religion: a definitive web resource

- Evolutionary views of human nature

- The Darwin and gender project overview

- Darwin and gender projects by Harvard students

- Darwin’s Women: Short Film

- Epsilon: a collaborative digital framework

- Funding overview

- History overview

- Frederick Burkhardt (1912-2007)

- Anne Schlabach Burkhardt (1916–2012)

Privacy policy

Search form

Hooker-j-d-02-02357.jpg.

The scientific results of the Beagle voyage still dominated Darwin's working life, but throughout these years he broadened his continuing investigations into the nature and origin of species and varieties. In contrast to the received image of Darwin as a recluse in Down, the letters show him to be an established and confident naturalist at the heart of British scientific society, travelling often to London and elsewhere to attend meetings and confer with colleagues, and involved in the social and political activities of the community of savants as well as in its philosophical and scientific pursuits. At home, time was filled with copious natural history work, writing, and gathering information from an ever-expanding network of correspondents. Down House was altered and extended to accommodate Darwin’s growing family and the many relatives and friends who came to stay; and, with his father’s advice, Darwin began a series of judicious financial investments to ensure a comfortable future for all those under his care.

The geological publications

In these years, Darwin published two books on geology, Volcanic islands (1844) and Geological observations on South America (1846), which completed his trilogy on the geological results of the Beagle voyage, and extensively revised his Journal of researches for a second edition in 1845, having already provided corrections in 1844 for a German translation of the first edition. He continued as an officer of the Geological Society of London, acting as one of four vice-presidents in 1844 and remaining on the council from 1845 onwards; he was a conscientious member of the Royal Geographical Society and the Royal Society; he regularly attended meetings and refereed papers for all these organisations. Between 1844 and 1846 Darwin himself wrote ten papers, six of which related to the Beagle collections. Among these were some studies of invertebrates that at first had been intended for publication in The zoology of the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle (1838–43) but were deferred when the Government grant was exhausted ( Correspondence vol. 2, letter to A. Y. Spearman, 9 October 1843, n. 1).

Darwin's inner circle: first discussions of species change

In addition, Darwin threw himself into analysing the results emerging from the examination of Beagle plant specimens by the young botanist and traveller, Joseph Dalton Hooker. More than 1200 letters between the two men survive, fully documenting a life-long friendship.

species are not (it is like confessing a murder) immutable

Darwin’s earlier scientific friendships were not neglected either, as the correspondence with Charles Lyell, George Robert Waterhouse, John Stevens Henslow, Leonard Horner, Leonard Jenyns, Edward Forbes, and Richard Owen shows. These friends, with the addition of Hooker, were important to Darwin for—among other things—they were the first people he turned to when he wished to discuss the problems and various scientific issues that arose out of his work on species. Darwin discussed his ideas on species mutability with Hooker, Horner, Jenyns, Lyell, Owen, and Charles James Fox Bunbury; he may well have broached the subject with others. Only two months after their first exchange, early in 1844, Darwin told Hooker that he was engaged in a ‘very presumptuous work’ which had led to the conviction that ‘species are not (it is like confessing a murder) immutable’ ( letter to J. D. Hooker, [11 January 1844] ). Nine months later, in his letter of 12 October [1844], he explained to Jenyns: 'I have continued steadily reading & collecting facts on variation of domestic animals & plants & on the question of what are species; I have a grand body of facts & I think I can draw some sound conclusions. The general conclusion at which I have slowly been driven from a directly opposite conviction is that species are mutable & that allied species are co-descendants of common stocks. I know how much I open myself, to reproach, for such a conclusion, but I have at least honestly & deliberately come to it.'

It is clear from the correspondence that his close friends were not outraged by Darwin’s heterodox opinions and later in the year both Jenyns and Hooker were invited to read a manuscript essay on his species theory (DAR 113; Foundations , pp. 57–255), an expanded version, completed on 5 July 1844, of a pencil sketch he had drawn up some two years earlier. But although eager for the views of informed colleagues, Darwin was naturally protective of his untried theory and seems to have shied away from the risk of pushing it too early into the open. In the event, it was not until the beginning of 1847 that Hooker was given a fair copy of the essay of 1844 to read (see Correspondence vol. 4, letter to J. D. Hooker, 8 [February 1847]). Darwin can be seen as a cautious strategist, sometimes confident, but often uneasy about his work, and always attempting to gauge the kind of response that his theory of transmutation would generate. In particular, he anxiously watched the controversy seething around an evolutionary book, Vestiges of the natural history of creation , published anonymously in 1844. His old friend Adam Sedgwick attacked the work vehemently in the Edinburgh Review (1845), while other colleagues like Edward Forbes ridiculed the theories employed there, caring only to join in the popular guessing-game about the identity of the author. One candidate, known to be working on species and varieties, was Darwin himself: as he told his cousin William Darwin Fox in a letter of [24 April 1845] , he felt he ought to be both ‘flattered & unflattered’ to hear that other naturalists attributed the book to him. But, as his letters to Hooker show, Darwin carefully considered and then rejected almost all of the contents of Vestiges , and he feared that the reaction to his own work would be prejudiced by the arguments aroused by its skilful but scientifically unsound reasoning.

Perhaps the most interesting letter relating to Darwin’s species theory, which also bears on his concern for the future, is that addressed to his wife Emma, dated 5 July 1844 , just after Darwin had completed the final draft of his essay on the subject. He asked her to ensure that the essay would be published in the event of his death and stipulated a sum of money to be bequeathed, together with his extensive library and portfolios of notes on species, to an editor who would undertake to see the work through the press. Darwin also listed possible editors: at first he proposed any one of Lyell, Henslow, Edward Forbes, William Lonsdale, Hugh Edwin Strickland, or Owen—the last with the caveat that he would probably not wish to take on the work. But the list was subsequently altered after Darwin’s second, and possibly third, thoughts on the choice of the right person. The names of Lonsdale, Forbes, and Owen were deleted, Henslow’s was queried, and J. D. Hooker’s was added. Much later, by the autumn of 1854 when Darwin began sorting out his notes in preparation for writing up his ‘big book’ on species ( Natural selection ), he had decided that Hooker was by far the best man for the task and added a note on the cover to that effect.

The full consideration that Darwin gave to the future editing and publication of his essay, and the way in which he wrote to colleagues and friends about his work, show clearly his intention to publish his theory. His instructions to Emma may, perhaps, as some scholars have thought, indicate a reluctance to take the responsibility for publishing upon himself, but, more plausibly, they portray a man faced with the task of establishing a theory and its consequences, and fearful lest both the energy and time necessary to achieve this end should be denied him. After prolonged illnesses in 1841 and 1842, years poorly represented in the Correspondence because he was for much of the time too ill even to write letters, Darwin felt that his life was only too likely to be cut short. Moreover, even when at his best, Darwin could never work as intensively as he felt he ought to, or needed to, for fear of inducing another breakdown in his health.

Volcanoes, rocks, and fossils

Darwin’s published work during this period secured his position as one of Britain’s foremost naturalists. His study of the volcanic islands visited during the Beagle voyage was based on a wide range of rock and mineral specimens, including his own, and considerable research into contemporary theories of volcanic activity, mountain formation, and the elevation of extensive tracts of land relative to the sea. Darwin put forward a new explanation of the origin of so-called ‘craters of elevation’, which formed the basis of discussions with Charles Lyell and Leonard Horner in letters in this volume. His observations on the lamination of volcanic rocks prompted an exchange with James David Forbes on the analogous structure of glacier-ice. In South America he proposed that the tension generated in molten rock before final consolidation, which he believed gave rise to this lamination, could also explain and link the widespread phenomena of cleavage and foliation, observable in some metamorphic rocks. His description and explanation of cleavage and foliation in the clay-slates and schists of South America benefitted from the mathematical expertise of William Hopkins and aroused the interest of Daniel Sharpe, whose subsequent work led to the general acceptance of Darwin’s views. South America drew together all the geological and palaeontological results of Darwin’s travels through that area and, like Volcanic islands , demonstrated how the structure of the land could best be explained by elevation. Darwin presented a wholeheartedly Lyellian picture of the geology of this vast area, reflecting the influence of Lyell’s Principles of geology (1830–3) and a commitment to Lyell’s idea of gradual geological change taking place overimmensely long periods of time; a commitment that transcended Darwin’s purely geological thought and influenced his speculations in all fields of natural history. But despite this clear and acknowledged debt, Darwin’s independence of mind was never in doubt and is well evidenced by the skilled and determined defence of his theories he invariably made against rivals of whatever standing. Through the pages of South America Darwin pursued an argument against the French palaeontologist Alcide d’Orbigny, insisting that the vast pampas formation could not have been laid down at a single moment through the action of a great débâcle , as Orbigny proposed. Darwin not only used his personal notes and records but, by letter, marshalled the resources of experts such as palaeontologists Edward Forbes and George Brettingham Sowerby, and the German naturalist Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg, to support his own opinion that the pampas formations had been deposited successively under mostly brackish or estuarine conditions.

Journal of researches : Darwin's story of the Beagle voyage

In addition to writing up his geology, Darwin undertook the revision of his Journal of researches for a second edition in 1845. At Lyell’s recommendation, arrangements were made for the rights of the work to be transferred from Henry Colburn, the original publisher, to John Murray, and throughout 1845 Darwin worked hard to provide manuscript copy to be published in three parts during the year. Though the text was reduced in volume, Darwin went to considerable trouble to add the latest descriptions of the Beagle collections, to alter and expand some of his previous suggestions about the causes of extinction, and to supplement the original account of the three Fuegians carried on board the Beagle back to Tierra del Fuego. By 1845, Darwin was in full command of a sophisticated theory of species transmutation and there is much interplay between the information supplied in letters to Darwin, the contents of the new edition of the Journal of researches , and his species work.

Joseph Hooker and the Beagle plant collections

The botany of the Beagle voyage was a topic still relatively unexplored by Darwin, even though he had collected plants extensively. Henslow, who had undertaken to describe the collection, was overwhelmed by ever-increasing parish and local concerns in Cambridge and Hitcham and apparently relieved to handover Darwin’s plants to Hooker, who had just returned from accompanying James Clark Ross’s Antarctic surveying expedition and who hoped to publish a detailed account of the flora of the Southern Hemisphere. Darwin was quick to spot in Hooker a man he judged could become the ‘first authority in Europe on that grand subject, that almost key-stone of the laws of creation, Geographical Distribution’ ( letter to J. D. Hooker, [10 February 1845] ) and quick to make use of the young man’s already large fund of botanical knowledge and his extensive connections with other British and European botanists. Darwin’s questions challenged Hooker to apply his particular knowledge to more general problems, always relating, directly or indirectly, to the question of the origin and nature of species. There is little in contemporary botany and botanical systematics that is not touched upon in their correspondence. Hooker’s observations on classification provided Darwin with a professional judgment on the plant world to place beside that of Waterhouse with respect to the animal kingdom. Hooker was also ready to discuss contemporary ideas on transformism in Britain and France and was a constant source of useful references and books. Some indication of the intellectual value that both men placed on their correspondence is found in the fact that they independently kept practically all the letters received from each other. The letters also document aspects of Hooker’s life: his search for a paid position, involving an unsuccessful campaign for the chair of botany at Edinburgh University and a period of half-hearted work with the Geological Survey of Great Britain. Like Darwin, he obtained Government aid to publish the results of his own four-year voyage and struggled to keep up to the time-table. And like Darwin, he was deeply committed to philosophical natural history.

Mr Arthrobalanus - Darwin's work on barnacles

It was also Hooker who helped Darwin in the first stages of his barnacle work, a study commenced towards the end of 1846. Hooker, ready with advice on microscopes and microscopic technique, assisted Darwin with drawings of his first dissection. The barnacle—‘M r Arthrobalanus’ in Hooker’s and Darwin’s letters—was a minute, aberrant species collected by Darwin in the Chonos Archipelago, off southern Chile, which lived inside the shell of the mollusc, Concholepas . Unusual sexual dimorphism, with the male virtually a parasite on the female, a complex life-cycle, and difficult taxonomic considerations, combined to intrigue Darwin, and he launched himself into a survey of related species to elucidate some of the problems presented by the animal. The cirripedes were to remain central to Darwin’s working life for the next eight years.

In this section:

- 1837-43: The London years to 'natural selection'

- 1856-1857: The 'Big Book'

Related people

Forbes, edward, forbes, j. d., henslow, j. s., hooker, j. d., horner, leonard, jenyns, leonardblomefield, leonard, lyell, charles, murray, john (b), owen, richard, waterhouse, g. r., about this article.

Based on the introduction to The correspondence of Charles Darwin , volume 3: 1844-1846

Edited by Frederick Burkhardt, Sydney Smith. (Cambridge University Press 1987)

Order this volume online from Cambridge University Press

Explore the letters to and from Charles Darwin over time

Darwin Correspondence Project [email protected]

© University of Cambridge 2022

Copyright declaration

Website by Surface Impression

- Historical sources

- Audio resources

- Video resources

- Letters data indexes

© 2024 University of Cambridge

- University A-Z

- Contact the University

- Accessibility

- Freedom of information

- Terms and conditions

- Undergraduate

- Spotlight on...

- About research at Cambridge

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Back to Entry

- Entry Contents

- Entry Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Notes to Darwinism

1. So described, Darwinism denotes not so much a theory as a ‘research tradition’ (Laudan, 1976) or a ‘scientific practice’ (Kitcher 1993); that is, at any given time in its history Darwinism consists of a family of theories related by a shared ontology, methodology and goals; and through time, it consists of a lineage of such theories. The word ‘theory’ above is being used in the very broad sense in which, from early on in his notebooks, Darwin kept referring to ‘my theory’.

2. The word ‘scientist’ was coined by William Whewell during Darwin’s lifetime, but very few of Darwin’s contemporaries owned up to it.

3. An entertaining account of the culture of the key members of this group can be found in Uglow 2002.

4. I.e., A Preliminary Discourse on the Study of Natural Philosophy , initially the introductory volume to Dionysius Lardner’s Cabinet Cyclopedia . It was published during Darwin’s final semester at Cambridge.

5. It is worth noting here that in chapter VI. of his Preliminary Discourse , a chapter devoted to induction and the discovery of causes, Herschel’s first two extended examples are taken from the first volume of Lyell’s Principles of Geology , which was published in 1830, the same year as the Preliminary Discourse . It is also worth noting that Lyell’s work is first and foremost a defense of a new method in geology, a new set of principles for the fledgling science. Thus Lyell’s work is held up as exemplary in a treatise on philosophy of science (as we would call it), and its influence on Darwin was as much on the philosophical as on the scientific level (as we would say).

6. Two puzzles are worth noting about Darwin’s reaction to Herschel’s letter. First, though Darwin’s unpublished diary of the Beagle voyage does comment on the personal importance to him of meeting and talking with Herschel at the Cape, the published Journal of Researches , based on the diary, completely omits mention of his days (June 8-15) in Cape Town. Though I can see no relevance to the fact, the published version of the diary appeared in 1839, two years after Babbage’s Bridgewater Treatise , and Darwin’s ‘Hurrah’. Second, the reference at the beginning of the Origin to ‘one of our greatest philosophers’ would be opaque to all but a group of insiders, those familiar with the excerpts of Herschel’s letter to Lyell that had been published in Babbage’s Bridgewater Treatise . Given that the passage had been published, why not name the philosopher who called species origins ‘that mystery of mysteries’? It would be interesting to know at what point Darwin decided to use that phrase to introduce his ‘big species book’.

In sum, Darwin appears reluctant to name Herschel in print in connection with ‘the species question’. Whether this is evidence that they discussed the content of that letter when they met in June of 1836 I do not know. However, there is strong evidence that they did. One of the early entries (p. 32; p. 38 of the Herbert edition) in ‘The Red Notebook’, which Darwin began the day the Beagle left Cape Town, refers to “Sir J. Herschels [sic] idea of escape of Heat prevented by sedimentary rocks, and hence Volcanic action…”. As Herbert’s note to the passage says: “Months before [meeting Darwin] Herschel had described his new notion of the cause of volcanic action in a letter to Charles Lyell dated 20 February 1836. Probably he repeated the same explanation to Darwin in June.” Another possibility is that he showed him a copy of the entire letter; since both were professional geologists who had been reading Lyell carefully, it could have served as the basis for their discussions. (Cf. Herbert 1980, pp. 38, 86.)

7. A more recent phenomenon than is usually appreciated. In Dobzhansky 1937, after describing Ronald Fisher’s ‘extreme selectionism’, he quotes, as a ‘good contrast’, the following remark of selection skeptics G. C. Robson and O. W. Richards 1936: “We do not believe that natural selection can be disregarded as a possible factor in evolution. Nevertheless, there is so little positive evidence in its favor…that we have no right to assign to it the main causative role in evolution.”

8. On which see Beatty 1990 and Lennox 1993.

9. Darwin was examined as an undergraduate on John Locke’s Essay on Human Understanding . As far as I know he never discusses whether this had any impact on his willingness to articulate the views expressed in this quote.

10. There is a very important, and under explored, tension here at least in Lyell and Herschel, both of whom seem to be in many other respects orthodox followers of Scottish empiricism.

11. Dov Ospovat (1980, 51-53), of course, argues persuasively that Darwin only gradually gave up a roughly Lamarckian view of the origins of variation.

12. Cf. Shanahan 1991, 249-269. Compare Eble 1999, 76-78, who notes a number of the same uses of ‘random’ and ‘chance’ as those discussed here, but sees their relationships quite differently. The ideas in Eble 1999 are nicely elaborated in Millstein (2000, 608-613).

13. Cf. Barrett et al. 1987, 279; and notes 1-4 to notebook page C133.

14. It should be stressed here that this discussion is restricted to explanations of adaptation within the Darwinian framework, i.e. by reference to natural selection. Whether other sorts of explanation in other aspects of biology are teleological or not, and whether, if they are, the explanation would take the same form, is left entirely open. For a good survey of this question, and a defense of a distinct understanding of biological function in the domain of comparative morphology, see Amundson and Lauder, 1998.

15. Mayr (1987) acknowledges this as an extension of his ideas.

Copyright © 2019 by James Lennox < jglennox+ @ pitt . edu >

- Accessibility

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2023 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Department of Philosophy, Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

The Early Evolutionary Imagination pp 69–100 Cite as

Darwinism in Literature

- Emelie Jonsson 4

- First Online: 29 September 2021

278 Accesses

Part of the book series: Cognitive Studies in Literature and Performance ((CSLP))

This book’s argument about the clash between Darwinism and human psychology assigns a special place to the arts. Literary authors not only engaged with the theoretical ideas of Darwin, Huxley, Spencer, and Haeckel but also mirrored and expanded the evolutionary myth-making of those thinkers. Literary authors writing in vastly different genres extrapolated the evolutionary myths into fictional worlds. Historically, literary scholars have not attended to the psychological aspect of that influence. This chapter outlines the history of previous literary scholarship on Darwinism and explains how evolutionary literary theory advances on previous criticism. Traditional humanists have catalogued Darwinian influences on fiction without aiming for explanation, and poststructuralist literary scholars have explained the influences mainly through ideology. Evolutionary literary theory returns the human mind to the equation.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Abrams, M. H. 1953. The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

———. 1997. “The Transformation of English Studies: 1930–1995.” Daedalus 126 (1): 105–31.

Beer, Gillian. 2009 [1983]. Darwin’s Plots: Evolutionary Narrative in Darwin, George Eliot and Nineteenth-Century Fiction. Cambridge University Press.

Bowler, Peter J. 1989. Evolution: The History of an Idea. Berkeley; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press.

———. 2007. Monkey Trials and Gorilla Sermons: Evolution and Christianity from Darwin to Intelligent Design. Cambridge; London: Cambridge University Press.

Boyd, Brian. 2006. “Getting It All Wrong.” American Scholar 76 (1): 156–158.

———. 2013. “What’s Your Problem? And How Might We Deepen It?” Scientific Study of Literature 3 (1): 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1075/ssol.3.1.02boy .

Article Google Scholar

Bradley, A. C. 1905. Shakespearean Tragedy: Lectures on Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth. London: Macmillan.

Brooks, Cleanth. 1947. The Well Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry. New York: Reynal & Hitchcock.

Carroll, Joseph. 1995. Evolution and Literary Theory . Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

Book Google Scholar

———. 2005. “Aestheticism, Homoeroticism, and Christian Guilt in The Picture of Dorian Gray .” Philosophy and Literature 29 (2): 286–304. https://doi.org/10.1353/phl.2005.0018 .

———. 2012a. “An Evolutionary Approach to Shakespeare’s King Lear. ” In Critical Insights: Family , edited by John Knapp, 83–103. Ipswich, MA: EBSCO.

———. 2012b. “An Open Letter to Jonathan Kramnick.” Critical Inquiry 38 (2): 405–410.

———. 2013a. “Correcting for The Corrections: A Darwinian Critique of a Foucauldian Novel.” Style 47 (1): 87–118.

———. 2013b. “A Rationale for Evolutionary Studies of Literature.” Scientific Study of Literature 3 (1): 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1075/ssol.3.1.03car .

Carroll, Joseph, Jonathan Gottschall, John Johnson, and Daniel J. Kruger. 2012. Graphing Jane Austen: The Evolutionary Basis of Literary Meaning . Cognitive Studies in Literature and Performance. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Castle, Gregory. 2013. The Literary Theory Handbook. Blackwell Literature Handbooks. 2nd ed. Wiley.

Clasen, Mathias. 2010. “Vampire Apocalypse: A Biocultural Critique of Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend. ” Philosophy and Literature 34 (2): 313–28. https://doi.org/10.1353/phl.2010.0005 .

———. 2012. “Attention, Predation, Counterintuition: Why Dracula Won’t Die.” Style 46 (3–4): 378–98.

———. 2017. Why Horror Seduces. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, Patricia. 2010. “The Next Big Thing in English: Knowing They Know That You Know.” New York Times , April 1, 2010, C1.

Crews, Frederick. 2008. “Apriorism for Empiricists.” Style 42 (2/3): 155–60.

Duncan, Ian. 2019. Human Forms: The Novel in the Age of Evolution. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Easterlin, Nancy. 2000. “Psychoanalysis and ‘The Discipline of Love’.” Philosophy and Literature 24 (2): 261–79. https://doi.org/10.1353/phl.2000.0033 .

Fletcher, Angus. 2014. “Another Literary Darwinism.” Critical Inquiry 40 (2): 450–69. https://doi.org/10.1086/674126 .

Fromm, Harold. 2006. “Reading with Selection in Mind.” Science 311 (5761): 612–13. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1123990 .

Gibbons, Tom H. 1973. Rooms in the Darwin Hotel: Studies in English Literary Criticism and Ideas, 1880–1920 . Nedlands: University of Western Australia Press.

Glendening, John. 2008. The Evolutionary Imagination in Late-Victorian Novels: An Entangled Bank . Aldershot: Ashgate.

Griffiths, Devin. 2019. The Age of Analogy: Science and Literature Between the Darwins. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Goldstein, Rebecca. 2006. “A Cross-Cultural Relationship.” Nature 441 (7090): 160–160. https://doi.org/10.1038/441160a .

Goodheart, Eugene. 2008. “Do We Need Literary Darwinism?” Style 42 (2/3): 181–85.

Gottschall, Jonathan. 2008. The Rape of Troy: Evolution, Violence, and the World of Homer . Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2013. “Toward Consilience, Not Literary Darwinism.” Scientific Study of Literature 3 (1): 16–18.

Greenberg, Jonathan. 2009. “Introduction: Darwinism in Literary Studies.” Twentieth-Century Literature 55 (4): 423–44. https://doi.org/10.1215/0041462X-2009-1001 .

Henkin, Leo. 1963 [1940]. Darwinism in the English Novel, 1860–1910: The Impact of Evolution on Victorian Fiction. New York: Russell & Russell.

Hillegas, Mark R. 1967. The Future as Nightmare: H. G. Wells and the Anti-Utopians . New York: Oxford University Press.

Holmes, John. 2009. Darwin’s Bards: British and American Poetry in the Age of Evolution. Edinburg: Edinburg University Press.

Huxley, T. H. 2009 [1863]. Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

James, Simon J., and Nicholas Saul. 2011. The Evolution of Literature: Legacies of Darwin in European Cultures . Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Kean, Sam. 2011. “Red in Tooth and Claw Among the Literati.” Science 332 (6030): 654–56. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.332.6030.654 .

Kramnick, Jonathan. 2011. “Against Literary Darwinism.” Critical Inquiry 37 (2): 315–47. https://doi.org/10.1086/657295 .

Levine, George. 1991 [1988]. Darwin and the Novelists: Patterns of Science in Victorian Fiction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McLean, Steven. 2009. The Early Fiction of H. G. Wells: Fantasies of Science . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

O’Hanlon, Redmond. 1984. Joseph Conrad and Charles Darwin: The Influence of Scientific Thought on Conrad’s Fiction . Edinburgh: Salamander Press.

Page, Michael R. 2012. The Literary Imagination from Erasmus Darwin to H. G. Wells: Science, Evolution, and Ecology . Farnham: Ashgate.

Parvini, Neema. 2012. Shakespeare and Contemporary Theory: New Historicism and Cultural Materialism. New York: Arden Shakespeare.

Richter, David H., ed. 2018. A Companion to Literary Theory. Hoboken: Blackwell.

Richter, Virginia. 2011. Literature After Darwin: Human Beasts in Western Fiction, 1859–1939. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ruddick, Nicholas. 2009. The Fire in the Stone: Prehistoric Fiction from Charles Darwin to Jean M. Auel . Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Saunders, Judith P. 2009. Reading Edith Wharton Through a Darwinian Lens: Evolutionary Biological Issues in Her Fiction. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co.

———. 2018. American Classics: Evolutionary Perspectives. Boston: Academic Studies Press.

Spolsky, Ellen. 2008. “The Centrality of the Exceptional in Literary Study.” Style 42 (2/3): 285–89.

Stevenson, Lionel. 1963 [1932]. Darwin Among the Poets. New York: Russell & Russell.

Van Ghent, Dorothy. 1953. The English Novel, Form and Function. New York: Rinehart.

Voigts, Eckart, Barbara Schaff, and Monika Pietrzak-Franger. 2014. Reflecting on Darwin . Ashgate Publishing Group.

Ward, Mrs. Humphry. 2013 [1888]. Robert Elsmere . Edited by Miriam E. Burstein. Brighton: Victorian Secrets.

Watt, Ian. 1957. The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson, and Fielding . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Zunshine, Lisa. 2010. Introduction to Cognitive Cultural Studies. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Zwierlein, Anne-Julia. 2005. Unmapped Countries: Biological Visions in Nineteenth Century Literature and Culture. London: Anthem Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway

Emelie Jonsson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Emelie Jonsson .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Jonsson, E. (2021). Darwinism in Literature. In: The Early Evolutionary Imagination. Cognitive Studies in Literature and Performance. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82738-0_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82738-0_3

Published : 29 September 2021

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-82737-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-82738-0

eBook Packages : Literature, Cultural and Media Studies Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Books Received

- Published: 16 October 1879

Darwinism and other Essays

Nature volume 20 , pages 575–576 ( 1879 ) Cite this article

14 Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

TO readers of NATURE there is nothing new and little very striking in these essays, and it is only justice to Mr. Fiske to remark that the title of the first which gives its name to the volume, claims nothing of the sort. The most interesting consideration in the four papers upon the subject is the marvellous way in which every science and line of thought, both in natural history and in human history, have entirely changed their aspect and started in a new direction since the publication of “The Origin of Species.” One fourth of the book is a review of Mr. Buckle's “History of Civilisation,” written and published by Mr. Fiske when he was nineteen years old: the object of reprinting which now it is hard to see. Yet it is interesting read in immediate juxtaposition with the chapters on Darwinism, for nothing could show so distinctly how high and dry the stream of knowledge has left the whole theory of a work most celebrated only twenty years ago. Buckle's book, the theorem of which was that there is a science of history, the laws of which are as uniform and invariable as those of mechanics or astronomy, if only we could discover and measure all the various forces at work, was an energetic effort in the right direction, and was gladly welcomed by many scientific men of the day. But the key to the puzzle had not then been found. Had Buckle lived in these days, when the works of Darwin, Herbert Spencer, and Sir H. Maine are familiar, he would, no doubt, have built up a far more coherent theory than he did.

Darwinism and other Essays.

By John Fiske, formerly Lecturer, on Philosophy, Instructor in History, and Assistant-Librarian at Harvard University. (London: Macmillan and Co., 1879.)

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Darwinism and other Essays . Nature 20 , 575–576 (1879). https://doi.org/10.1038/020575a0

Download citation

Issue Date : 16 October 1879

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/020575a0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Erasmus Darwin. Erasmus Darwin was a member of the small circle of improvers, factory owners, medical men, and politically progressive intellectuals who called themselves the Lunar Society (Uglow, 2002). Erasmus Darwin had three sons, one of whom was also a physician with an inquiring mind - he was Charles Darwin's father. The Darwin-Wedgwood

The Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection. The theory of evolution by natural selection is a theory about the mechanism by which evolution occurred in the past, and is still occurring now. The basic theory was developed by both Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace (1823窶・913), however, Darwin gave a much fuller argument.

This entry offers a broad historical review of the origin and development of Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection through the initial Darwinian phase of the "Darwinian Revolution" up to the publication of the Descent of Man in 1871. The development of evolutionary ideas before Darwin's work has been treated in the separate entry evolutionary thought before Darwin.

4 Darwin's Essays of 1842 and 1844 were never published in his life time. His son Francis published them on the hundredth anniversary of his father's birth. See Charles Darwin, Foundations of the Origin of Species: Two Essays Written in 1842 and 1844, ed. Francis Darwin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1909).

Darwin's also unpublished 1844 'Essay': appearing six times in the 60,000 words that again anticipate the structure and argument of the Origin (F. Darwin, 1909). One of the few aspects of the Origin that is not anticipated in these earlier renderings of Darwin's theory was the separate consideration of

Cultural environments can clearly exert strong coevolutionary forces on genes. The development of agriculture, for example, seems to have launched a wave of strong selection on genes (Hawks et al. 2007). Similarly, human ―social instincts,‖ as Darwin called them, plausibly evolved by gene- culture coevolution.

The contributors to this volume, including M. J. S. Hodge, David Hull, and Roberto Moreno, gathered in 1972 at an international conference on the comparative reception of Darwinism. Their essays ...

Abstract. - Darwin's Theory of Evolution is the widely held notion that all life is related and has descended from a common ancestor: the birds and the bananas, the fishes and the flowers -- all ...

Darwin's mentors decisively shaped his philosophical attitudes and scientifi c career. Henslow was the fi nal link in securing his position on the H. M. S. Beagle. The combination of meticulous fi eld observation, collection, experimentation, note taking, reading, and thinking during that fi ve-year journey through a wide cross-section of ...

Darwinian evolution had to compete on several fronts inside and outside of evolutionary biology. The mechanism of natural selection as the engine of organic evolution was questioned and relieved ...

Sometimes "Darwinism" is treated as a synonym for "evolution." A history-of-science commonplace has it that in the Origin Darwin furnished a new argument for an old idea, evolution, which went back at least to the days of Darwin's grandfather, the physician Erasmus Darwin, and his French contemporary, the Paris naturalist Jean-Baptiste de

Abstract. It is often said that Darwin's study of nature drove him to atheism. Whereas this might be, in principle, possible, it does not seem to have actually been the case for him. Both in his autobiography, which was not intended to be published, and in his personal correspondence, Darwin consistently described himself as an agnostic.

All told, On the Origin of Species is one of the most sustained and compelling arguments in English literature. Darwin was modest about his own literary abilities, but he is increasingly being claimed as an important prose stylist. More than Darwin himself, T. H. Huxley acquired that reputation in his own lifetime.

This essay discusses Universal Darwinism: the idea that Darwinian mechanisms can explain interesting evolutionary change in many different domains, in both the Humanities and the Natural Sciences. The idea should appeal to Big Histori-ans because it links research into evolutionary change at many different scales.

Darwin was not, however, a man to be rushed. While his autobiography claims that the framework of his theory was laid down by 1839, its first outline sketch did not emerge until 1842. That essay was heavily edited, with many insertions and erasures. It formed the vital kernel of his more expansive but also unpolished and unpublished essay of 1844.

Since 1837, Darwin had been dealing with a theory on the transmutation of species and registering his ideas in notebooks. In June 1842, he wrote a brief abstract of his theory in pencil on 35 pages, which he enlarged into 230 pages during the summer of 1844 (Barlow, 1958, Footnote 1 p. 120; Darwin, 1859, p. 1).Early in 1856, Charles Lyell (1797-1875) advised him to write his views as a whole.

It was lucky that Darwin kept a rough copy (Burkhardt and Smith 6, 445-50). The following year, when Alfred Russel Wallace unexpectedly sent Darwin an essay describing his independent formulation of the same notion of evolution by natural selection, Darwin turned to his correspondence with Gray to verify his priority.

Between 1844 and 1846 Darwin himself wrote ten papers, six of which related to the Beagle collections. Among these were some studies of invertebrates that at first had been intended for publication in The zoology of the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle (1838-43) but were deferred when the Government grant was exhausted ( Correspondence vol. 2, letter ...

Charles Darwin 1809-1882. English scientist. Generally regarded as the most prominent of the nineteenth-century evolutionary theorists, Charles Darwin is primarily known for his On the Origin of ...

Notes to Darwinism. 1. So described, Darwinism denotes not so much a theory as a 'research tradition' (Laudan, 1976) or a 'scientific practice' (Kitcher 1993); that is, at any given time in its history Darwinism consists of a family of theories related by a shared ontology, methodology and goals; and through time, it consists of a ...

The human imagination faced Darwin's theory in scientific arguments and political essays as well as in novels and poems. Though the non-fiction writing was generally less "veiled in musical language" and more constrained by the public responsibility of truth claims, non-fiction writers did as we have seen produce sparks of mythology.

Darwinism and other Essays. By John Fiske, formerly Lecturer, on Philosophy, Instructor in History, and Assistant-Librarian at Harvard University. (London: Macmillan and Co., 1879.)

The study shows that the main differences between the views of the two founders of evolutionary theory lie in their claims about the speed of evolution and the adoption of an individual or ...

How to Write an Assignment In 2024 - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. "Unlock the secrets of assignment writing in 2024 with our expert guide. From mastering different styles to honing your research skills, we've got you covered. Get ready to impress your professors and elevate your academic game!"