- Science & Math

- Sociology & Philosophy

- Law & Politics

Masculinity in ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’

- Masculinity in ‘A Streetcar Named…

Williams presents masculinity in ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ by presenting the violent nature of Stanley in comparison to Blanche as well as how this naturally leads to the destruction of Blanche and symbolically the old south.

From the start of the play, the characters of Stanley and Blanche are presented as polar opposites with Blanche being representative of ‘the soft, sensitive and the delicate’, as Williams says, shown by how she is ‘daintily dressed’ in white. Whereas, Stanley represents the ‘savage and brutal nature of modern men’ as shown by how he ‘heaves’ a ‘package of meat’ to Stella showing his masculine traits.

This contrast sets Stanley and Blanche as antagonist versus protagonist from the start of the play; a troupe of classic Aristotelian tragedy, highlighting the inevitable clash between the characters and the tragic ending of the play. Masculinity is also presented by showing the nature of violent relationships in Elysian Fields revealing the constant power struggle between males and females.

Masculinity is presented in ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ through Williams’ use of Stanley’s violent nature. He displays high masculinity and violence through the use of predatory animalistic imagery in both stage directions and Blanche’s descriptions of him.

In the ‘Poker Night’ scene, Stanley ‘stalks’ and ‘charges’ at Stella and hits her. Those aggressive verbs reflect an animalistic nature which Stanley is associated with throughout the play. Blanche describes him as a ‘survivor of the Stone-Age” and “ape-like” revealing his primitive, uncivilized nature.

She also uses a metaphor of ‘bearing the raw meat home from the kill in the jungle!” which further reveals his animalistic behavior as he is aggressive. The use of only exclamation marks and scripted non-fluency by Williams in Blanche’s description of Stanley reveals her fear and desperation which comes due to Stanley’s aggressive masculinity. Masculinity is further presented by asserting Stanley’s dominance over Stella and the household.

He ‘hurls the cups and saucer” to the ground when Stella asks him to clean up after himself and he states that “Every man is a king” thus is asserting his masculinity and dominance over Stella in the relationship. Stanley’s masculinity and physical violence are used to invoke fear in the women and assert himself over them, and this leads to Stella “crying weakly”.

His masculinity is further shown by his demand to have the documents relating to Blanche and Stella’s background and Belle Reve. He uses a series of demanding and interrogative questions such as “where are the papers?” and “what is Ambler & Ambler?” He also repeats throughout the scene the law ‘Napoleonic code’ which is a law that states that whatever belongs to the wife belongs to the husband as well.

He attempts to make his demands of the documents seem like he cares by stating that Stella will be having a baby, but in reality, he demands details and repeats the term ‘Napoleonic code’ to assert his dominance in the relationship. The demanding tone and continuous interrogation that Blanche faces due to Stanley’s masculinity leave her overwhelmed and she gives in to him as she “touches her forehead” and then “hands him the entire box”.

Therefore, Williams presents masculinity in ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ by revealing Stanley’s violent and animalistic nature as well as his desire to dominate and control in a domestic relationship.

Masculinity is further presented by Williams in ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ by highlighting the power struggle between the opposing sexes of male and female specifically in domestic relationships.

Stanley and Stella’s relationship is revealed to be an aggressive and violent relationship in the ‘Poker night’ scene. When Stanley ‘charges’ at Stella there is a ‘sound of a blow’ and Stella ‘cries out’. The use of violence by Stanley against Stella reveals the masculine, abusive nature of Stanley in their domestic relationship.

Not only is he physically violent but also psychologically abusive as seen by how Stanley calls for Stella after the fight “[with heaven-splitting violence] STELLL-AHHHH!”.

Not only does Stanley reveal his masculinity through the physical violence but also his desire to have Stella back is even more violent. His use of his abusive, masculine nature in their relationship is further highlighted when Stella talks about her wedding night saying, “Stanley smashed all the light—bulbs”.

The normal reality of domestic violence in Elysian Fields is further displayed by Steve and Eunice’s fight. Eunice shouts “you hit me! I’m gonna call the police” revealing the violent nature of Steve revealing his masculinity. The fact that Stella remarks that “Eunice seems to have some trouble with Steve” shows her carelessness about the situation due to its normality at Elysian Fields.

Furthermore, Mitch’s dismissal of Stanley’s abusive nature in his relationship with Stella when he says to Blanche “don’t take it seriously” revealing how the abusive and violent domestic relationship is seen as normal at Elysian Fields.

Masculinity is finally presented as the reason for destruction, specifically Blanche’s downfall and the destruction of the Old South. When Stanley attacks Stella it brings Blanche to near hysteria as she shouts ‘shrilly’ and ‘runs to the kitchen’. She is left terrified and describes Stanley’s violence as ‘Lunacy, absolute lunacy’.

Stanley’s masculinity also destroys Blanche both psychologically and physically as his rape of her is the ultimate symbol of male dominance. He pins her ‘inert figure”; to the bed suggesting that she has been left powerless in the face of Stanley’s masculinity evoking catharsis in the audience. The rape is the ultimate destruction of Blanche who represents a Southern Belle with her manners and appearance thus the destruction of the Old South by the new emerging south represented by Stanley.

He states “We had this date from the beginning” highlighting the tragic nature of the play as her downfall as well as the Old South’s downfall is inevitable due to the tragic genre of the play according to Aristotle’s definition of a tragedy. The rape removes all of Blanche’s fantasy as Stanley states “There is nothing but goddam imagination”. Therefore, the violence and masculinity of Stanley brings realism to the play.

Blanche is arguably an expressionist character due to her overly exaggerated/ flowery dialogues; thus, she is theatrically isolated as well as powerless due to her femininity. Mitch’s masculinity is also revealed by his attempt to rape Blanche by saying “What I’ve been missing all summer” and he also brings realism to Blanche by revealing that she is “not clean enough to bring in the house with [his] mother.” Thus, masculinity destroys Blanche’s hopes and illusions.

Related Posts

- Sex and Gender Roles

- A Streetcar Named Desire Quotations & Analysis

- Streetcar Named Desire: Characters, Summary, Themes

- Class Conflict in A Streetcar Named Desire

Author: William Anderson (Schoolworkhelper Editorial Team)

Tutor and Freelance Writer. Science Teacher and Lover of Essays. Article last reviewed: 2022 | St. Rosemary Institution © 2010-2024 | Creative Commons 4.0

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post comment

A Streetcar Named Desire: Theme & Key Quotes: Masculinity

A streetcar named desire: theme & key quotes: masculinity, understanding the theme: masculinity.

- Masculinity in ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ is showcases multiple aspects - both brutish and gentle .

- Stanley Kowalski embodies a raw and primitive form of masculinity powered by physical strength, sexual dominance, and a volatile temper.

- Harold Mitchell (Mitch), on the other hand, portrays a softer, more refined type of masculinity showcased through his respect for women and longing for genuine connections.

- The conflict between Stanley and Mitch brings out the contrast between these two forms of masculinity.

Key Ideas Around Masculinity

- Physical Dominance : This is most visible in Stanley who sees himself as the master of his house and uses physical violence to assert his authority.

- Emotional Vulnerability : This is portrayed through Mitch, who displays emotions publicly and has a sensitive character.

- Sexual Power : Stanley views women primarily as objects for his sexual desires, while Mitch desires a more emotional and genuine connection.

- Masculinity and Class : Stanley’s working-class background contributes to his rough and aggressive masculinity, while Mitch’s softer approach might be seen as more middle-class.

Important Quotes

- “I am the king around here, so don’t forget it!” - Stanley asserting his dominion.

- “I try to give her what she needs.” - Stanley on his relationship with Stella, reducing it to physical needs.

- “You need somebody—and I need somebody, too.” - Mitch highlighting his desire for companionship and emotional connection.

Literary Techniques and Devices

- The contrast between Stanley and Mitch is used to explore different aspects of masculinity.

- Stanley’s violent behavior serves as a critique of toxic masculinity.

- The dialogue and actions of the characters highlight their differing attitudes towards women, reinforcing their contrasting forms of masculinity.

- The use of staging and symbolism further emphasize the differences in masculine identity —Stanley’s love for bowling, raw meat, and alcohol versus Mitch’s gentle manner and concern for his sick mother.

Understanding this theme can help you gain a deeper comprehension of the play ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ and the way masculinity is portrayed and challenged.

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Literature A Streetcar Named Desire

Depiction of Masculinity in On Chesil Beach and A Streetcar Named Desire

*minimum deadline

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below

- David and Goliath

- Anna Karenina

- Young Goodman Brown

- Tragic Hero

- Lady Lazarus

Related Essays

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Plays — A Streetcar Named Desire

Essays on A Streetcar Named Desire

Choosing the right essay topic is crucial for your success in college. Your creativity and personal interests play a significant role in the selection process. This webpage aims to provide you with a variety of A Streetcar Named Desire essay topics to inspire your writing and help you excel in your academic pursuits.

Essay Types and Topics

Argumentative.

- The role of gender in A Streetcar Named Desire

- The impact of societal norms on the characters' behaviors

Paragraph Example:

In Tennessee Williams' A Streetcar Named Desire, the portrayal of gender dynamics is a central theme that sheds light on the power struggles and societal expectations faced by the characters. This essay aims to explore the significance of gender in the play and its influence on the characters' decisions and relationships.

Through a close examination of the gender dynamics in A Streetcar Named Desire, this essay has highlighted the complexities of societal norms and their impact on individual lives. The characters' struggles serve as a reflection of the broader societal challenges, prompting us to reconsider our perceptions of gender roles and expectations.

Compare and Contrast

- The parallels between Blanche DuBois and Stanley Kowalski

- The contrasting symbols of light and darkness in the play

Descriptive

- The vivid imagery of New Orleans in the play

- The sensory experiences portrayed in A Streetcar Named Desire

- An argument for Blanche's mental state and its impact on her actions

- The case for the significance of the play's setting in shaping the characters

- Reimagining a key scene from a different character's perspective

- A personal reflection on the themes of illusion and reality in the play

Engagement and Creativity

As you explore these essay topics, remember to engage your critical thinking skills and bring your unique perspective to your writing. A Streetcar Named Desire offers a rich tapestry of themes and characters, providing ample opportunities for creative exploration in your essays.

Educational Value

Each essay type presents a valuable opportunity for you to develop different skills. Argumentative essays can refine your analytical thinking, while descriptive essays can enhance your ability to paint vivid pictures with words. Persuasive essays help you hone your persuasive writing skills, and narrative essays allow you to practice storytelling and narrative techniques.

Reality Versus Illusion in The Streetcar Named Desire

The theme of abandonment and brutality in a streetcar named desire, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

How Blanche and Stella Rely on Self-delusion in a Streetcar Named Desire

The character of blanche in the play a streetcar named desire, the truth of blanche in a streetcar named desire, a marxist criticism of a streetcar named desire, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

An Examination of The Character of Blanche in a Streetcar Named Desire

The flaws of blanche and why she ultimately failed, analysis of stanley kowalski’s role in tennessee williams’ book, a streetcar named desire, analysis of blanche and stella relationship in a streetcar named desire, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

The Concealed Homosexuality in a Streetcar Named Desire

Oppression, its brutality and its inescapability, is a dominant theme in literature, similar themes in a streetcar named desire by tennessee williams and water by robery lowell, first impression lies: the power and masculinity exuded by stanley kolawski, determining the tragedy potential in a streetcar named desire, how tennessee williams is influenced by the work of chekhov, the use of suspense in a streetcar named desire, a streetcar named desire by tennessee williams: personal identity of blanche, the portrayals of sexuality in cat on a hot tin roof and a streetcar named desire, evaluation of the social class ranking as illustrated in the book, a streetcar named desire, blanche and mitch relationship in a streetcar named desire, female powerlessness in the duchess of malfi and a streetcar named desire, a comparison between the plastic theatre and expressionism in a streetcar named desire, morality and immorality in a streetcar named desire and the picture of dorian gray, oppositions and their purpose in "a streetcar named desire" and "the birthday party", how femininity and masculinity are presented in ariel and a streetcar named desire, tennessee williams’ depiction of blanche as a casualty as illustrated in his play, a streetcar named desire, history defined the themes of a streetcar named desire, comparing social and ethnic tensions in a streetcar named desire and blues for mister charlie, the use of contrast as a literary device at the beginning of a streetcar named desire.

December 3, 1947, Tennessee Williams

Play; Southern Gothic

The French Quarter and Downtown New Orleans

Blanche DuBois, Stella Kowalski, Stanley Kowalski, Harold "Mitch" Mitchell

1. Vlasopolos, A. (1986). Authorizing History: Victimization in" A Streetcar Named Desire". Theatre Journal, 38(3), 322-338. (https://www.jstor.org/stable/3208047) 2. Corrigan, M. A. (1976). Realism and Theatricalism in A Streetcar Named Desire. Modern Drama, 19(4), 385-396. (https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/50/article/497088/summary) 3. Quirino, L. (1983). The Cards Indicate a Voyage on'A Streetcar Named Desire'. Contemporary Literary Criticism, 30. (https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CH1100001571&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=00913421&p=LitRC&sw=w&userGroupName=anon%7E8abc495e) 4. Corrigan, M. A. (2019). Realism and Theatricalism in A Streetcar Named Desire. In Essays on Modern American Drama (pp. 27-38). University of Toronto Press. (https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.3138/9781487577803-004/html?lang=de) 5. Van Duyvenbode, R. (2001). Darkness Made Visible: Miscegenation, Masquerade and the Signified Racial Other in Tennessee Williams' Baby Doll and A Streetcar Named Desire. Journal of American Studies, 35(2), 203-215. (https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-american-studies/article/abs/darkness-made-visible-miscegenation-masquerade-and-the-signified-racial-other-in-tennessee-williams-baby-doll-and-a-streetcar-named-desire/B73C386D2422793FB8DC00E0B79B7331) 6. Cahir, L. C. (1994). The Artful Rerouting of A Streetcar Named Desire. Literature/Film Quarterly, 22(2), 72. (https://www.proquest.com/openview/7040761d75f7fd8f9bf37a2f719a28a4/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=5938) 7. Silvio, J. R. (2002). A Streetcar Named Desire—Psychoanalytic Perspectives. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry, 30(1), 135-144. (https://guilfordjournals.com/doi/abs/10.1521/jaap.30.1.135.21985) 8. Griffies, W. S. (2007). A streetcar named desire and tennessee Williams' object‐relational conflicts. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 4(2), 110-127. (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/aps.127) 9. Shackelford, D. (2000). Is There a Gay Man in This Text?: Subverting the Closet in A Streetcar Named Desire. In Literature and Homosexuality (pp. 135-159). Brill. (https://brill.com/display/book/9789004483460/B9789004483460_s010.xml)

Relevant topics

- Macbeth Ambition

- Romeo and Juliet

- Macbeth Guilt

- The Importance of Being Earnest

- Oedipus Rex

- Hamlet Theme

- The Glass Menagerie

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Bibliography

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Join Now to View Premium Content

GradeSaver provides access to 2356 study guide PDFs and quizzes, 11005 literature essays, 2763 sample college application essays, 926 lesson plans, and ad-free surfing in this premium content, “Members Only” section of the site! Membership includes a 10% discount on all editing orders.

A Streetcar Named Desire

Strong first impression: stanley kowalski's power and masculinity anonymous college.

Throughout scenes 1 and 2 of A Streetcar Named Desire , playwright Tennessee Williams presents Stanley as extremely powerful and authoritative through the use of dialogue as well as stage directions. The audience immediately learns how strong Stanley is in a physical sense; however, we soon discover that he is also very controlling in his own animalistic nature. Furthermore, it becomes evident that Stanley regards himself as the dominant partner in his relationship with Stella, as Williams conveys a sense of pre-eminence in Stanley’s attitude towards his wife. Each of these factors contribute to Stanley’s overall image of forceful masculinity, which grows more apparent as the play progresses.

Stanley’s physical appearance is a key aspect of his overall dominance in Streetcar , as it reflects his toughness and boldness throughout the play. For example, in the stage directions Williams describes Stanley as ‘strongly, compactly built,' instantly illustrating him as a robust and muscular man. The fact that he is built ‘compactly’ not only highlights his solidity but also suggests that he is explosive, in the sense that his body is so compressed that he could easily lash out in an act of violence at any second. At the beginning of Act...

GradeSaver provides access to 2313 study guide PDFs and quizzes, 10989 literature essays, 2751 sample college application essays, 911 lesson plans, and ad-free surfing in this premium content, “Members Only” section of the site! Membership includes a 10% discount on all editing orders.

Already a member? Log in

We are aware of some issues with pdfs on the website after last night's update. Some should now be fixed and others will be later today.

A Streetcar Named Desire

Nathan M. ★ 5.0 (1)

University of york - ma philosophy.

Philosophy Master's Graduate from York with a passion for language, learning, and everything academic!

Notes || Exam Prep || Character Profiles || Themes || Additional Reading & Videos

This text is included in Paper 2 . You can find notes and guides for it below.

- Scene Analysis

Additional Reading & Videos:

- Essay: Blanche Dubois’s Tragedy of Incomprehension (Psychoanalysis)

- Video: Literary, Political and Social Context

- Film: A Streetcar Named Desire (dir. Diane Lane, 1995)

- Newspaper Article: Tennessee Williams: The Quiet Revolutionary

- Essay: Stand-in Stanley: “Streetcar named Desire’s” Polish African American

- Essay: From ‘Home-Place’ to the Asylum: Confining Spaces in A Streetcar Named Desire”

- Video: Literary, Historical and Biographical Contexts

Character Profiles

- Blanche Dubois

- Harold 'Mitch' Mitchell

- Minor Characters

- Stanley Kowalski

- Stella Kowalski

- Death and Desire

- Fantasy and Delusion

- Female Entrapment

- Hegemonic Masculinity

- Social Class

Connect with PMT Education!

- Revision Courses

- Past Papers

- Solution Banks

- University Admissions

- Numerical Reasoning

- Legal Notices

The photo that wrapped Marlon Brando’s homoerotic swagger in a tight leather jacket

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Book Review

Marlon Brando: Hollywood Rebel

By Burt Kearns Applause: 296 pages, $29.95 If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org , whose fees support independent bookstores.

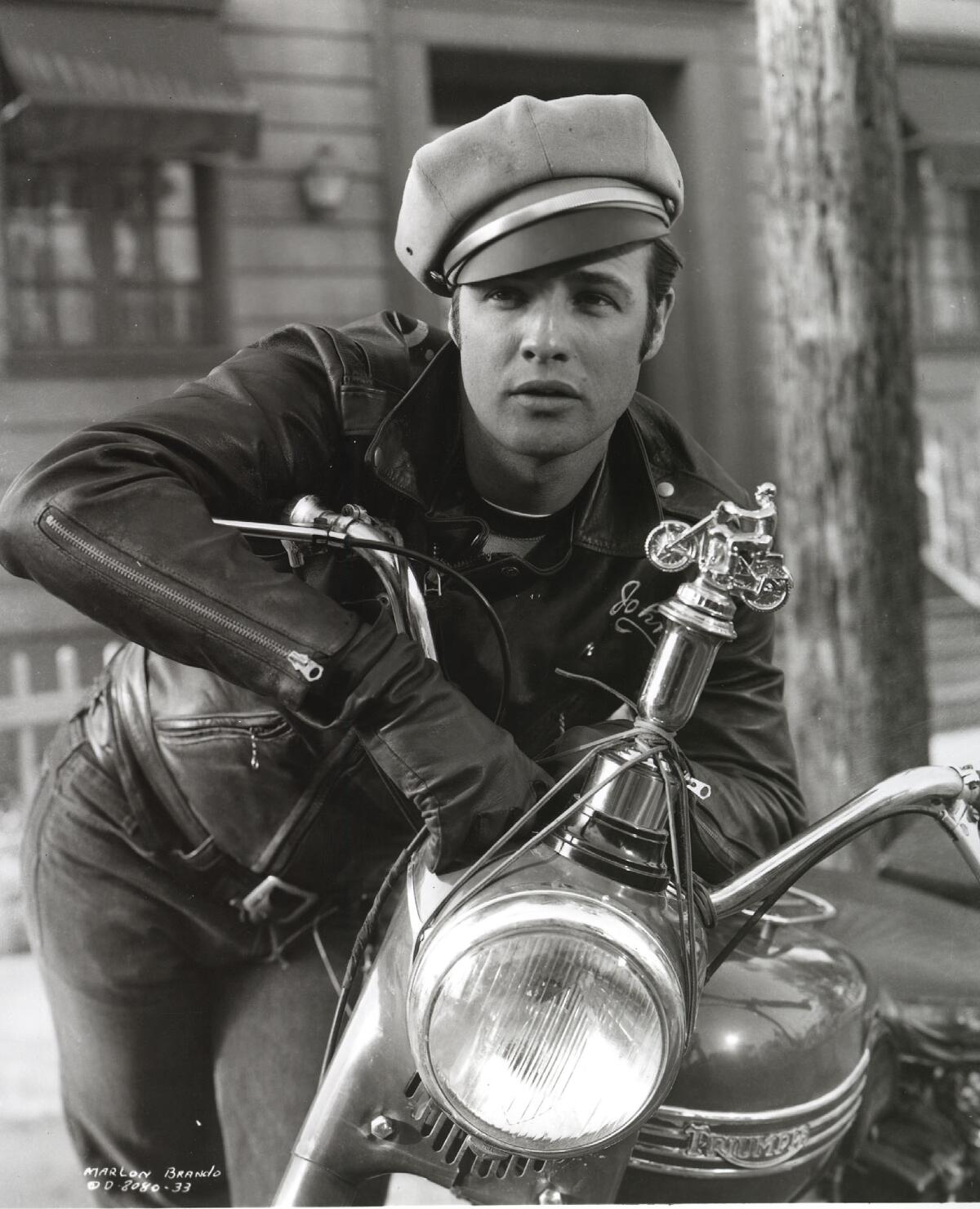

He leans over the handlebars of his motorcycle, zipped up in a black leather jacket, his biker cap tilted over his right eye. His lips slightly parted, his eyes inquisitive, he instantly embodies contradictions: tough and vulnerable, fearless and scared, masculine and feminine.

This image of Marlon Brando from the 1953 film “The Wild One,” absorbed by the likes of Elvis Presley, James Dean and John Lennon, immortalized in the pop art of Andy Warhol, has had an almost subliminal impact on the American psyche.

“The Wild One” is nowhere close to Brando’s best movie or best performance. But this singular image, culled from an 89-minute film, somehow plumbs the depths of our thoughts and feelings on masculinity and rebellion.

How Keith Haring’s art transcended critics, bigotry and a merciless virus

Biographer Brad Gooch’s “Radiant” reveals how much life and creativity artist Keith Haring packed into 31 years before he died of AIDS.

March 15, 2024

Burt Kearns’ new book, “Marlon Brando: Hollywood Rebel,” is not, the author takes pains to explain, a Brando biography. There have been many of those, including the actor’s own “Brando: Songs My Mother Taught Me” (written with Robert Lindsey).

“Hollywood Rebel” is, as the author writes, “a study of how one man’s artistic and personal decisions affected not only those around him, but all of Western society and popular culture.” But at its most incisive the book is a biography of this specific image from Brando’s late 20s, the biker portrait seen ’round the world, recognizable and indelible even to those who have never seen the movie from which it was extracted.

“The Wild One” was based on the Frank Rooney short story “Cyclists’ Raid,” which in turn was based on the 1947 invasion of the Central California town of Hollister (near Monterey) by thousands of rowdy bikers over a turbulent Fourth of July weekend. As Kearns writes, post-World War II motorcycle “gangs” were generally populated by veterans set adrift in a new world after their service ended. “Cyclists’ Raid” caught the attention of producer Stanley Kramer, who specialized in progressive “social problem” movies, including one he had just made with Brando, “The Men,” in which the rising star played a paralyzed vet.

When Brando signed on to star in “The Wild One” he was hot off the success of the film adaptation of “A Streetcar Named Desire,” which had made him a young Broadway legend when it premiered there in 1947. In “Streetcar” Brando played Stanley Kowalski as a virtual fire hose of sexuality, a brute in a tight white T-shirt (and, though the film conveys the point with Production Code-mandated subtlety, a rapist). This was a new kind of screen carnality, raw and visceral, and Brando, a mumbling powerhouse, was a new kind of star.

How 3 shades of jazz swirled together in 1959 to make ‘Kind of Blue’

James Kaplan’s triple biography weaves together ‘3 Shades of Blue’ in the backstories of Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Bill Evans at the height of jazz’s cultural sway.

March 8, 2024

But “The Wild One” was newer still. As Kearns observes, the movie’s homoerotic subtext quickly becomes homoerotic text. Brando’s Johnny Strabler, pouty with a slight Southern lilt, engages in a frenemy relationship with a rival biker, Chino (played by Lee Marvin), who behaves more like a jilted lover than a fellow road dog (“I love ya, Johnny!” he repeats over and over; during a fistfight Johnny knocks Chino through a store window, where he lands smack in between bride and groom mannequins).

Johnny seems utterly baffled by, if not terrified of, the opposite sex, represented by a townie (Mary Murphy) looking to spice up her small-town existence and a biker moll (Yvonne Doughty) with fond memories of a one-night stand.

Then there’s that tight leather, which would make Brando-as-Johnny a sort of butch fetish object for gay fans, artists and filmmakers, including Warhol, who used the famous image in multiple works; and Kenneth Anger, whose 1963 avant-garde short film “Scorpio Rising” features clips of Johnny cruising on his bike.

That Brando himself freely discussed his sexual adventures with both men and women made the homoerotic symbolism of “The Wild One” both easier and more resonant.

Lest you think the film influenced only gay subculture, Kearns also details its impact on rock ’n’ roll, particularly on a shy megastar from Memphis, who openly proclaimed his Brando worship, and a group of lads from Liverpool.

In one scene, Chino is lamenting to Johnny that “the Beetles” miss him, apparently alluding to the gang’s groupies. And yes, this was seven years before a certain band began to call itself the Beatles. John Lennon was on record as a huge Brando and “Wild One” fan. Kearns builds a compelling case for this origin story of the band’s name as he goes down one of the book’s many rabbit holes, some more rewarding than others.

The big picture is much clearer. Brando, and especially this Brando, has had an outsize influence on American culture and our conception of how a rebel behaves. “What are you rebelling against?” Johnny is asked as his gang makes itself at home in small-town California. His famous response: “Whaddya got?” Brando-as-Johnny grew into an all-purpose symbol of revolt, against norms in society, sexuality, fashion, music … and whaddya got. (Two years later came “Rebel Without a Cause” and another timeless jacket, this one a red nylon windbreaker.)

“Hollywood Rebel” occasionally wears out its welcome. Kearns has a habit of extensively, excessively quoting the same handful of expert sources. He sometimes overstates his arguments, as when he calls the Hollister biker invasion “one of the most influential public disturbances since the Boston Massacre” (one could imagine many rivals for that list, from the Civil War draft riots, to Vietnam protests, to Watts, to Ferguson, to the Jan. 6 insurrection). The author also seems a little too proud of his prolific double-entendre usage, even for a book that is largely about sexual magnetism.

On balance, however, “Hollywood Rebel” is a worthy addition to the Brando bookshelf, largely because the author picks an idea and never loses sight of it, even as he fans across multiple disciplines to explore the idea. This is a book about how one facet of one man captured in one image from one film can send ripples through the world.

Chris Vognar is a freelance culture writer.

More to Read

What became of Marlon Brando’s ecological wonderland on the sea? I visited to find out

March 20, 2024

Commentary: ‘American Fiction’s’ Oscar shows not all movies by Black directors need to be about violence and poverty

March 11, 2024

Granderson: Your U.S. history class needed a film like ‘Rustin’

Feb. 24, 2024

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

How many lives can one author live? In new short stories, Amor Towles invites us along for the ride

March 29, 2024

Storytellers can inspire climate action without killing hope

March 26, 2024

A novel about psychosis, or spirits, or exploitation. But definitely about family

March 22, 2024

In ‘The Exvangelicals,’ Sarah McCammon tells the tale of losing her religion

How to Restage ‘Cabaret’? Don’t Treat It Like a Classic.

The British director Rebecca Frecknall’s immersive revival of the Kander and Ebb musical was a hit in London. This spring, she’s bringing it to Broadway.

Rebecca Frecknall at the August Wilson Theater in Manhattan, which will be transformed into the Kit Kat Club for “Cabaret,” opening there next month. Credit... Amir Hamja/The New York Times

Supported by

- Share full article

By Douglas Greenwood

Douglas Greenwood reported this article from New York, London and Amsterdam.

- March 27, 2024

When Rebecca Frecknall was a child, one of her favorite things to watch was a televised 1993 London revival of “Cabaret,” which her father had recorded on VHS tape. As the British theater director grew up, she hoped that one day she would stage a version of the musical, in which a writer falls in love with an exuberant and wayward cabaret performer in Weimar-era Germany.

In early March, in a Midtown rehearsal room, Frecknall, 37, was preparing to do just that. Her “Cabaret,” which opens in previews at the August Wilson Theater on April 1, is a transfer from London’s West End, where it opened in 2021 to critical acclaim. The show won seven Olivier Awards , the British equivalent to the Tonys.

“I always wanted to direct ‘Cabaret’,” Frecknall said later in an interview. “I just never thought I’d get the rights to it.” Her opportunity came when Eddie Redmayne — a producer on the show who played the Emcee in London, and will reprise the part on Broadway — asked her in 2019 to be part of a bid for a revival.

At first it seemed like “a pipe dream,” Redmayne said, but after years of wrangling, they pulled it off. For the London show, the Playhouse Theater was reconfigured to reflect the musical’s debauched setting, transforming it into the Kit Kat Club, with cabaret tables and scantily clad dancers and musicians roaming the foyer and auditorium. The August Wilson Theater is getting a similar treatment, Frecknall said. To honor the playhouse’s namesake, the production designer Tom Scutt commissioned a Black artist, Jonathan Lyndon Chase, to paint murals in the reconfigured lobby, with theatergoers now entering via an alleyway off 52nd Street.

Shortly before the show opened in London, Frecknall’s father died. That recorded revival, directed by Sam Mendes, was one of his favorites, and Frecknall loved it so much that, as she grew up and studied theater, she chose never to see the show onstage.

That has perhaps helped her find her own way with the show. In London, where Frecknall has been mounting notable productions since 2018, she has earned a reputation for refreshing the classics: “ A Streetcar Named Desire ,” “ Three Sisters ” and “ Romeo and Juliet. ” But she is not afraid to disregard Chekhov’s stage directions or cut key scenes from Shakespeare. For her recent show “Julie” at the International Theater Amsterdam, she adapted Strindberg’s “Miss Julie” herself, changing the setting from a manor house to a modern, stainless-steel kitchen. Instead of a gown, her Julie wore a gold sequined cocktail dress.

Ivo van Hove, the Tony-award winning director who commissioned “Julie” for his Amsterdam playhouse, said he admired Frecknall for her “daring to transpose those sacred texts to the present,” adding that she taught her actors to “speak the language of the body, not just the language of words.”

Dance sequences are a hallmark of her shows, often devised by Frecknall herself. “I sort of say it flippantly that I’d like to be a choreographer,” she said. “There’s something for me about bodies and movement that feels so good.”

In her “Romeo and Juliet,” the knife fights between Montagues and Capulets became energetic, ballet-like episodes. For “Streetcar,” at the same theater, her ensemble moved as if guided by the crashing cymbals of a live drummer. Her influences were rooted more in dance than drama, she said: “I would be Pina Bausch if I could.”

Frecknall’s interest in movement started with childhood dance classes that she took while growing up in Warboys, a small village near Cambridge, England. There, she said, “everybody knew each other,” and “no one went to the theater.” Her family was the exception.

Her father, Paul Frecknall, had been obsessed with the stage since he was a boy, but a theater career was out of the question for the working-class lad, Frecknall said. It “wasn’t really something to pursue — you got a job that paid something,” she added. Instead, he channeled his passion into amateur dramatics, and, along with his wife Kate, joined a community theater group.

Frecknall’s parents nurtured her interest in the arts. She took flute and dance lessons and listened to cast albums from her father’s CD collection. Occasionally, she went with her father to London to see shows on the West End. (The first time she saw “Cats,” she said, she was 8 years old and so scared she cried.)

She also enjoyed sorting through her father’s theater memorabilia. Among his playbill collection, Frecknall discovered the program for a London production of Peter Shaffer’s “Equus.” Her curiosity was piqued, and her father gave her the script.

“It changed my life,” Frecknall said. Having only seen musicals, she hadn’t considered that theater could be a vehicle for moral or political questions. “There were ideas in that play that were so much bigger,” she added. “I didn’t know theater could do that.”

After graduating high school, Frecknall enrolled to study drama at Goldsmiths College in London. One of her teachers there, Cass Fleming recalled that she was “curious and sort of brave,” and that, even then, she was making work “that sat between directing and choreographing.” After postgraduate study at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, she worked as an assistant director at esteemed London institutions, including the Young Vic and the National Theatre.

It was while working on a 2012 staging of “The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe” that Frecknall met Rupert Goold, the Tony-nominated director who now runs the Almeida, an off-West End venue known for its cutting-edge approach. “Directing tends to breed a certain level of overconfidence,” Goold said, but with Frecknall, it “just didn’t feel like that. She seemed quiet, kind of good-natured, and a bit anxious.” He added that he would “be lying if I said I knew from that first week that we had a major director on our hands.”

In 2016, after assisting directors for nearly seven years, Frecknall had her directorial debut: a more traditional take on “Miss Julie” at a regional theater. Two years later, she joined the Almeida’s resident director program. That year, Goold commissioned her production of Williams’s rarely staged “Summer and Smoke,” in which actors performed in a pit of dirt surrounded by pianos that the ensemble sporadically played. It won Frecknall her first Olivier.

The actor Patsy Ferran, who played the lead in “Summer and Smoke” and has worked with Frecknall on two other shows, said rehearsing with the director was liberating. “You can think you’ve found your limit,” Ferran said, but Frecknall always pushed performers beyond it, drawing better performances out of them.

Rehearsals usually began with warm-up games, she said, and though Frecknall is serious about her work, “the process isn’t.” Both Ferran and Paul Mescal, who played Stanley Kowalski in Frecknall’s “Streetcar,” compared the director’s rehearsal rooms to “playgrounds.”

Rehearsals were the part of a production Frecknall said she enjoyed the most. “I don’t like having a show on,” she added. “I do always have a slight, low level of anxiety around it,” she said.

Mescal, who won an Olivier for his “Streetcar” performance, said, “Rebecca struggles to enjoy the finished product because she’s always searching for something greater.” But that was also “why her work is so brilliant and so commanding,” he added. “Because she never settles.”

“Cabaret” chronicles the insular nightclub life of its characters while Nazism thrives around them, suggesting that their apathy helped spread it. During rehearsals this month, Frecknall invited Joshua Stanton, a rabbi, and Betsy L. Billard, a queer Jewish woman, into the studio for a workshop, giving the cast a chance to contemplate the musical’s historical message.

As part of that process, Redmayne said, “Every single person in that cast had a conversation about our own heritage.” Frecknall “knows her responsibility to the story,” he added, which is to help the cast “bring their own stories to the piece.”

Before the “Cabaret” transfer was announced, Frecknall had signed on to direct another musical on Broadway: an adaptation of “The Great Gatsby” with music by Florence Welch, of Florence and the Machine. Frecknall didn’t have time for both, she said, though it was “probably the best thing” for “Gatsby,” a show based on such an important American text, that it would now be directed by an American, Rachel Chavkin.

Frecknall said she was at a point in her career where she could afford to be selective, and now turns down work that doesn’t feel right. “I never feel like I’m going to work to fund my life. My work is my life,” she said. “I’m really low maintenance,” she added. “I’m single and don’t have dependents. I just have to feed my cat.”

Once “Cabaret” opens here, she plans to return to London and take a break for the summer, she said: By then, she will have spent six months working on three productions back-to-back. But she was already looking forward, and said that she would love to make a film one day or direct another stage production from her dad’s VHS collection: Stephen Sondheim’s “Company.”

Getting a musical off the ground is expensive and difficult, she said — like a “big fish in a stream” that “very few people catch” — and she knew “Cabaret” might be her one chance.

But van Hove wasn’t quite so worried. “She is one of those directors who will stay with us for a long time,” he said.

An earlier version of this article misstated Rebecca Frecknall’s age; she is 37, not 38. It also misstated her mother’s name; she is Kate, not Jane. The article also mistakenly stated that Frecknall’s parents had met in a community theater group; they joined the group after they had met. It misidentified the origins of a playbill for Peter Shaffer’s “Equus”; it was from a London production, not the original Broadway production. And it misspelled the name of a composer and lyricist; he is Stephen Sondheim, not Steven.

How we handle corrections

Advertisement

A Streetcar Named Desire

Tennessee williams, everything you need for every book you read..

Many critics believe that Williams invented the idea of desire for the 20th century. The power of sexual desire is the engine propelling A Streetcar Named Desire : all of the characters are driven by “that rattle-trap street-car” in various ways.

Much of Blanche’s conception of how she operates in the world relies on her perception of herself as an object of male sexual desire. Her interactions with men always begin with flirtation. Blanche tells Stella that she and Stanley smoothed things over when she began to flirt with him. When Blanche meets Stanley’s poker-playing friends, she lights upon Mitch as a possible suitor and adopts the guise of a chaste lover for him to pursue.

Blanche nearly attacks the Young Man with her aggressive sexuality, flirting heavily with him and kissing him. Blanche dresses provocatively in red satin, silks, costume jewelry, etc: she calls attention to her body and her femininity through her carefully cultivated appearance. Blanche clings to her sexuality more and more desperately as the play progresses. To Blanche, perhaps motivated by her discovery that her first husband was in fact homosexual, losing her desirability is akin to losing her identity and her reason to live.

Stella’s desire for Stanley pulls her away from Belle Reve and her past. Stella is drawn to Stanley’s brute, animal sexuality, and he is drawn to her traditional, domestic, feminine sexuality. Stella is pregnant: her sexuality is deeply tied to both womanliness and motherhood. Even though Stanley is violent to Stella, their sexual dynamic keeps them together. When Blanche is horrified that Stanley beats Stella, Stella explains that the things that a man and a woman do together in the dark maintain their relationship.

Stanley’s sexuality and his masculinity are extremely interconnected: he radiates a raw, violent, brute animal magnetism. Stanley’s sexuality asserts itself violently over both Stella and Blanche. Although he hits Stella, she continues to stay with him and to submit to his force. While Stella is at the hospital giving birth to his child, Stanley rapes Blanche: the culmination of his sexual act with Stella coincides with the tragic culmination of his destined date with Blanche.

Throughout the play, sexual desire is linked to destruction. Even in supposedly loving relationships, sexual desire and violence are yoked: Stanley hits Stella, and Steve beats Eunice . The “epic fornications” of the DuBois ancestors created a chain reaction that has culminated in the loss of the family estate. Blanche’s pursuit of sexual desire has led to the loss of Belle Reve, her expulsion from Laurel, and her eventual removal from society. Stanley’s voracious carnal desire culminates in his rape of Blanche. Blanche’s husband’s “unacceptable” homosexual desire leads to his suicide.

Sexual Desire ThemeTracker

Sexual Desire Quotes in A Streetcar Named Desire

They told me to take a street-car named Desire, and transfer to one called Cemeteries, and ride six blocks and get off at—Elysian Fields!

Sit there and stare at me, thinking I let the place go? I let the place go? Where were you ! In bed with your–Polack!

Since earliest manhood the center of [Stanley’s] life has been pleasure with women, the giving and taking of it, not with weak indulgence, dependently, but with the power and pride of a richly feathered male bird among hens.

I never met a woman that didn’t know if she was good-looking or not without being told, and some of them give themselves credit for more than they’ve got.

Now let’s cut the re-bop!

After all, a woman’s charm is fifty percent illusion.

Oh, I guess he’s just not the type that goes for jasmine perfume, but maybe he’s what we need to mix with our blood now that we’ve lost Belle Reve.

The kitchen now suggests that sort of lurid nocturnal brilliance, the raw colors of childhood’s spectrum.

STELL-LAHHHHH!

There are things that happen between a man and a woman in the dark–that sort of make everything else seem–unimportant.

What you are talking about is brutal desire–just–Desire!–the name of that rattle-trap street-car that bangs through the Quarter.

Don’t–don’t hang back with the brutes!

Young man! Young, young, young man! Has anyone ever told you that you look like a young Prince out of the Arabian Nights?

Sometimes–there’s God–so quickly!

It’s only a paper moon, Just as phony as it can be–But it wouldn’t be make-believe If you believed in me!

I told you already I don’t want none of his liquor and I mean it. You ought to lay off his liquor. He says you’ve been lapping it up all summer like a wild-cat!

I don’t want realism. I want magic!

Tiger–tiger! Drop the bottle-top! Drop it! We’ve had this date with each other from the beginning!

Please don’t get up. I’m only passing through.

You left nothing here but spilt talcum and old empty perfume bottles–unless it’s the paper lantern you want to take with you. You want the lantern?

Whoever you are—I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Masculinity and Physicality Theme Analysis. Masculinity and Physicality. LitCharts assigns a color and icon to each theme in A Streetcar Named Desire, which you can use to track the themes throughout the work. Masculinity, particularly in Stanley, is linked to the idea of a brute, aggressive, animal force as well as carnal lust.

Masculinity is presented in 'A Streetcar Named Desire' through Williams' use of Stanley's violent nature. He displays high masculinity and violence through the use of predatory animalistic imagery in both stage directions and Blanche's descriptions of him. In the 'Poker Night' scene, Stanley 'stalks' and 'charges' at ...

Masculinity in 'A Streetcar Named Desire' is showcases multiple aspects - both brutish and gentle. Stanley Kowalski embodies a raw and primitive form of masculinity powered by physical strength, sexual dominance, and a volatile temper.

Introduction. Hegemonic masculinity, a concept which is part of Connell's (1995) gender order theory, can be defined as a practice that authorises and encourages male domination, therefore justifying the subordination of women and non-hegemonic males. The theme of hegemonic masculinity is central to both Williams' play, but also to the ...

Sexual entitlement is a very important theme used by both McEwan and Williams' to further present masculinity throughout A Streetcar Named Desire and On Chesil Beach. Sexual entitlement is a particularly striking theme in A Streetcar Named Desire, due to the unexpected implied rape scene at the end of scene ten.

The purpose of this essay is to explore the impact of longheld notions of gender-based behavior upon the characters in Tennessee Williams' A Streetcar Named Desire. Throughout the play, the characters struggle with the desire to establish their own identities and the pressure to accept and conform to the role that society determines for them.

An Examination of The Character of Blanche in a Streetcar Named Desire. 5 pages / 2287 words. In Tennessee Williams' play, A Streetcar Named Desire, the nature of theatricality, "magic," and "realism," all stem from the tragic character, Blanche DuBois. Blanche is both a theatricalizing and self-theatricalizing woman.

That Rattle-trap Streetcar Named Desire. The Desire streetcar line operated in New Orleans from 1920 to 1948, going through the French Quarter to its final stop on Desire Street. Streetcar on the silver screen. The original 1947 Broadway production of Streetcar shot Marlon Brando, who played Stanley Kowalski, to stardom. Brando's legendary ...

Join Now Log in Home Literature Essays A Streetcar Named Desire Strong First Impression: Stanley Kowalski's Power and Masculinity A Streetcar Named Desire Strong First Impression: Stanley Kowalski's Power and Masculinity Anonymous College. Throughout scenes 1 and 2 of A Streetcar Named Desire, playwright Tennessee Williams presents Stanley as extremely powerful and authoritative through the ...

A Streetcar Named Desire can be described as an elegy, or poetic expression of mourning, for an Old South that died in the first part of the twentieth century. Expand on this description. The story of the DuBois and Kowalski families depicts the evolving society of the South over the first half of the twentieth century.

Dependence on Men. A Streetcar Named Desire presents a sharp critique of the way the institutions and attitudes of postwar America placed restrictions on women's lives. Williams uses Blanche's and Stella's dependence on men to expose and critique the treatment of women during the transition from the old to the new South.

INTRODUCTION. In A Streetcar Named Desire, the themes of death and desire permeate most of the play's events. Williams crafts these two elements as extremely interconnected, and relates them to Blanche's downfall. and her tragic ostracization from society. This is essentially through all of the loss. she has experienced in her life (most ...

Many critics believe that Williams invented the idea of desire for the 20th century. The power of sexual desire is the engine propelling A Streetcar Named Desire: all of the characters are driven by "that rattle-trap street-car" in various ways. Much of Blanche's conception of how she operates in the world relies on her perception of ...

Essay, masculinity and femininity in A streetcar named Desire - Free download as Word Doc (.doc / .docx), PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free.

Historical Context Essay: Post-World War II New Orleans. Set in New Orleans in the late 1940s, A Streetcar Named Desire unfolds in a time when the United States in general and the South in particular were poised for major economic growth and significant social change. This period gave rise to the New South, as an impoverished, largely agrarian ...

8 Pages. Tennessee Williams's A Streetcar Named Desire shows the life of Blanche Dubois while she has a long-term stay with her sister and her brother-in-law. The play was put on stage during the late 1940's and set in the suburban part of New Orleans, Louisiana. During this time many were rejoicing over the end of the Great Depression and ...

A Streetcar Named Desire - Masculinity / Femininity quotes. 22 terms. Daisy_Cox. Preview. Heany- A constable calls (content ) 11 terms. kellywhelan656. Preview. Poetry Study Set. 12 terms. quizlette81701802. Preview. Streetcar masculinity essay plans. 8 terms. Meganxx_21. Preview. Masculinity - A Streetcar Named Desire. Teacher 10 terms. aw761 ...

Socio-Cultural Context. Gender Roles. A Streetcar Named Desire is often considered a play that critiques the limitations that the post-world war American society imposed on itself. While the restrictions on women are an explicit focus of Williams', the gender stereotyping that men suffer is also addressed implicitly.

Themes. Death and Desire. Fantasy and Delusion. Female Entrapment. Hegemonic Masculinity. Social Class. Advertisement. Scene analysis, context, character profiles and themes for AQA English A-level English Literature Paper 2: A Streetcar Named Desire.

Similar documents to "A Streetcar Named Desire Essay on Masculinity" avaliable on Thinkswap. Documents similar to "A Streetcar Named Desire Essay on Masculinity" are suggested based on similar topic fingerprints from a variety of other Thinkswap Subjects

Essay on "A streetcar named desire" - Free download as Word Doc (.doc / .docx), PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free.

Streetcar Named Desire Essay Plans. 5 terms. katierogers888. Preview. A streetcar named desire essay plan themes. 49 terms. meercatred. Preview. ... mimics Stanley - 'Rosenkavelier', 'so utterly uncavalier' - Context: reflects culture of war years, masculinity defined by willingness to fight - Allan killed by society rejecting his 'tenderness ...

When Brando signed on to star in "The Wild One" he was hot off the success of the film adaptation of "A Streetcar Named Desire," which had made him a young Broadway legend when it ...

In London, where Frecknall has been mounting notable productions since 2018, she has earned a reputation for refreshing the classics: "A Streetcar Named Desire," "Three Sisters" and ...

Many critics believe that Williams invented the idea of desire for the 20th century. The power of sexual desire is the engine propelling A Streetcar Named Desire: all of the characters are driven by "that rattle-trap street-car" in various ways.. Much of Blanche's conception of how she operates in the world relies on her perception of herself as an object of male sexual desire.