Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9 What is an Argument?

What is an argument.

This is an introductory textbook in logic and critical thinking. Both logic and critical thinking centrally involve the analysis and assessment of arguments. “Argument” is a word that has multiple distinct meanings, so it is important to be clear from the start about the sense of the word that is relevant to the study of logic. In one sense of the word, an argument is a heated exchange of differing views as in the following:

Sally: Abortion is morally wrong and those who think otherwise are seeking to justify murder!

Bob: Abortion is not morally wrong and those who think so are right-wing bigots who are seeking to impose their narrow-minded views on all the rest of us!

Sally and Bob are having an argument in this exchange. That is, they are each expressing conflicting views in a heated manner. However, that is not the sense of “argument” with which logic is concerned. Logic concerns a different sense of the word “argument.” An argument, in this sense, is a reason for thinking that a statement, claim or idea is true . For example:

Sally: Abortion is morally wrong because it is wrong to take the life of an innocent human being, and a fetus is an innocent human being.

In this example Sally has given an argument against the moral permissibility of abortion. That is, she has given us a reason for thinking that abortion is morally wrong. The conclusion of the argument is the first four words, “abortion is morally wrong.” But whereas in the first example Sally was simply asserting that abortion is wrong (and then trying to put down those who support it), in this example she is offering a reason for why abortion is wrong.

We can (and should) be more precise about our definition of an argument. But before we can do that, we need to introduce some further terminology that we will use in our definition. As I’ve already noted, the conclusion of Sally’s argument is that abortion is morally wrong. But the reason for thinking the conclusion is true is what we call the premise . So we have two parts of an argument: the premise and the conclusion. Typically, a conclusion will be supported by two or more premises. Both premises and conclusions are statements. A statement is a type of sentence that can be true or false and corresponds to the grammatical category of a “declarative sentence.” For example, the sentence,

The Nile is a river in northeastern Africa

is a statement. Why? Because it makes sense to inquire whether it is true or false. (In this case, it happens to be true.) But a sentence is still a statement even if it is false. For example, the sentence,

The Yangtze is a river in Japan

is still a statement; it is just a false statement (the Yangtze River is in China). In contrast, none of the following sentences are statements:

Please help yourself to more casserole

Don’t tell your mother about the surprise

Do you like Vietnamese pho?

The reason that none of these sentences are statements is that it doesn’t make sense to ask whether those sentences are true or false (rather, they are requests or commands, and questions, respectively).

So, to reiterate: all arguments are composed of premises and conclusions, which are both types of statements. The premises of the argument provide a reason for thinking that the conclusion is true. And arguments typically involve more than one premise.

A Brief Introduction to Philosophy Copyright © 2021 by Southern Alberta Institution of Technology (SAIT) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Arguments and Philosophical Reasoning

Lesson Plan

Materials needed

- Chalkboard or whiteboard

- Computer and projector or equipment to watch short video clips from the web

Introduction This lesson can be used at any time in a philosophy course, for a meeting of a philosophy club or discussion group, or for a workshop. Because it introduces students or participants to the method of how philosophers approach philosophical questions, it is especially appropriate as a first lesson or experience. It is intended to get students or participants to recognize that philosophical reasoning takes place in the form of argumentation. This lesson, however, stops short of providing tools for evaluating philosophical arguments. Therefore, if you are using this as the first lesson in a class or for a first meeting of a philosophy club or interest group, it would be natural to follow it up with some lessons on critical thinking or logic to provide a more complete foundation in philosophical reasoning. In turn, those lessons could be followed by explorations of philosophical content, in which you would use the method of philosophical reasoning to address specific philosophical questions or topics.

Am I Your Teacher? (10 minutes)

- Begin by writing “I am the teacher of this class” (or whatever would be most appropriate for your setting) at the bottom of the board with a line drawn above it. Ask the students or participants to show by raising hands how many of them think this statement is true. Presumably, all of them will. If so, ask them why they think this. As they give reasons, write the reasons on the board above the line. Once there are a large number of reasons on the board, ask them what everything written on the board together is called. The purpose is to illustrate that an argument is being made.

I told you that I am the teacher.

I am standing at the front of the class.

I am leading this exercise.

I am the only adult in the room.

____________________________

I am the teacher of this class

- Ask the students or participants why they think you had them do this as the first exercise when exploring philosophy. Lead a brief discussion. A few points to try to develop during the discussion include:

- What you have written on the board is an example of an argument

- Arguments are the way we think and reason—when we’re reasoning something out, what we’re doing is forming a series of arguments in our heads

- Philosophy is essentially a process of thinking systematically about difficult and interesting questions, and a primary component of philosophy centers on making and evaluating arguments.

What Is an Argument? (10 minutes)

- Begin this activity by showing the Monty Python clip, “ The Argument Clinic .”

- After showing the clip, ask:

What are the two different concepts of “argument” presented in the skit?

The two concepts are:

- Mere contradiction or a dispute (Yes it is… No it isn’t… Yes it is… No it isn’t…)

- (Proposed by the customer) “A collected series of statements to establish a definite proposition.”

When we talk about arguments as used by philosophers, we are talking about an argument in the latter sense. Again, doing philosophy is essentially a process of making and evaluating arguments.

Parts of an Argument (10 minutes)

- Return to the “I am the teacher of this class” argument. You’ll use it as an example to illustrate and help explore what arguments are and how they work.

- In a group discussion, explore the parts of an argument. As you do so, it will be helpful to develop the following points and to introduce the following terms:

Ask what parts constitute an argument. What are its basic building blocks? Arguments are composed of sentences. In fact, they are made up of a particular type of sentence, known as a proposition.

Proposition : A declarative sentence that has a truth value. In other words, a proposition is a sentence that can be either true or false. To be precise, propositions express facts about the world that can either be true or false. Examples include “Today is Monday” and “It’s raining outside.”

Question: Are there kinds of sentences that are not propositions? Answer: Yes. Questions, commands, exclamations, etc., are all types of sentences that are not propositions because they lack a truth value. Examples include “Go open the door,” and “What is today’s date?”

Typically, most of the propositions in an argument state facts or provide information which support the claim being made. These propositions are known as premises.

Premise : A proposition serving as a reason for a conclusion.

The claim being made is known as the conclusion of the argument.

Conclusion : A proposition that is supported or entailed by a set of premises.

Arguments always have one conclusion, but the number of premises can vary quite a bit. The “I am the teacher of this class” argument has several premises.

Question: Can there be an argument with only one premise? Answer: Yes. For example, “Bill is an unmarried male. Therefore, Bill is a bachelor.”

Question: Can there be an argument with no premises? Answer: Yes. For example, consider an argument with no premises and the following conclusion: “It is either Monday in Tokyo or it is not Monday in Tokyo.”

It’s worth noting that adding premises doesn’t necessarily add support for a conclusion. For example, the argument above with no premises is in fact a compelling argument, since it always has to either be Monday or not be Monday in Tokyo.

- Now we can say what an argument is in a more precise way:

Argument : An argument is a set (a collection) of propositions in which one proposition, known as the conclusion, is claimed to derive support from the other propositions, known as premises.

- To summarize:

- Arguments are the way we think and reason—when we’ve reasoning something out, what we are really doing is forming a series of arguments in our heads.

- Though “argument” can also mean a dispute in common use, that’s not the sense in which we mean it when doing philosophy.

- Arguments consist of a conclusion and (almost always) some premises.

- The conclusion is what the argument is meant to support as being true; it’s the claim being made.

- The premises provide support for the conclusion.

- There can be any number of premises, from 0 to an infinite number (but having more premises doesn’t necessarily mean there is more support for the conclusion!).

- The premises and conclusion are propositional statements; that is, they are sentences that express facts (propositions) about the world that may be true or false.

Argument Dissection (10 minutes)

The “I am the teacher of this class” argument is in normal form. That’s just a fancy way of saying that the premises have been collected together in a list with the conclusion following them. Often, we separate the conclusion from the premises by drawing a line between them (or by putting in the symbol \, which means “therefore,” before the conclusion) to make it very clear which proposition is the conclusion. Usually arguments written in English prose are not so simply presented. The conclusion may be stated first, or for stylistic reasons it might not be at either the beginning or the end of the prose. Converting an argument from English prose into normal form allows us to clearly pick out the premises and conclusion.

How can we identify the premises and the conclusion of an argument in ordinary prose? It can take some judgment, but we are usually guided by indicator words. The propositions in arguments are often accompanied by words that indicate whether that proposition is a premise or a conclusion.

As a group, brainstorm words or phrases that might indicate that the proposition they introduce is a premise or a conclusion. The following lists provide some of the most common premise and conclusion indicators.

Premise Indicators: since, because, for, in that, as, given that, for the reason that, may be inferred from, owing to, inasmuch as

Conclusion Indicators: therefore, consequently, thus, hence, it follows that, for this reason, we may infer, we may conclude, entails that, implies that

With that background in hand, the next activity will help everyone see that arguments are in fact all around us and help them to identify more easily the structure of those arguments, which is an important first step in evaluating whether we should be convinced by the argument.

- Hand out to each student or participant a couple of arguments you have found in editorials, blogs, philosophy texts, or wherever. Ask them to re-write the arguments in normal form, identifying the premises and the conclusions.

- When done, ask everyone to pair up. Each person should show his or her partner the original arguments and the rewritten arguments in normal form. Each pair should then discuss whether or not the premises and conclusions were correctly identified. Float throughout the room and answer questions.

Evaluating Arguments (10 minutes)

This is a fun activity to help everyone start thinking about how to evaluate whether we should be convinced by an argument. Begin this activity by showing the Monty Python clip, “ She’s a Witch! ”

Begin a discussion about whether people are convinced by the argument provided in the video clip. Try to focus the discussion on whether the premises provide good reasons for believing that the conclusion is correct. Note that until the characters in the video clip actually use the scale, they don’t know whether some of the facts asserted in the premises are true. That’s often the case in exploring philosophical questions. What’s important is the logical relationship between the premises and the conclusion. Hypothetically, if the premises were all to turn out to be true, would they then make it likely that the conclusion would also be true? By asking that question, we can evaluate the reasoning in an argument. Philosophers often focus the most on this step. If the reasoning in an argument is good, then we can go on to ask whether the premises are in fact true. Often that requires empirical investigation (and so may require the aid of scientists or other specialists). If both are the case—the reasoning is good and the premises are true—only then should we assent to the conclusion.

After a few minutes, pause the discussion. Ask the students to write a paragraph defending why they are or are not convinced by the argument in the video clip. Remind everyone that the paragraph should, of course, take the form of an argument!

If this lesson is being used for a one-time event, you can ask some volunteers to read their paragraphs and then resume a discussion about what they learned. If you are using this lesson as part of a class or a series of meetings, you can always ask the students or participants to write the paragraph at home and bring it with them to the next meeting. You can then discuss their paragraphs and what they learned from the exercise. If you are teaching a formal course, you can have the students turn in their paragraphs as an assignment.

Follow-Up and Conclusions

If this lesson is part of a course or a long sequence of meetings, it would be worthwhile to follow up with another lesson or two on how to properly evaluate arguments. How that is done will depend on how formal or informal you want to be in thinking about logic, and also how long you want to spend on an introductory philosophical reasoning unit.

Supplemental Materials

There are a number of excellent textbooks and resources on arguments, critical thinking, and logic. For example, reading the first two chapters of the following logic textbook would prepare you thoroughly for leading this lesson:

Hurley, Patrick. A Concise Introduction to Logic (Twelfth ed.). Stamford: Cengage Learning, 2015.

(As an aside, reading the third and fourth chapters of the Hurley text would prepare you well for a potential follow-up lesson on distinguishing deductive from non-deductive arguments and evaluating arguments.)

A supplementary text with a more informal discussion of arguments is the following:

Weston, Anthony. A Rulebook for Arguments (4th ed.). Indianapolis: Hackett Publications, 2009.

The following brief magazine article was written by the authors of this lesson and, in a fun way, explores how philosophers investigate philosophical questions:

Gluck, S. and Rodriguez, C. “The Philosopher’s Toolbox,” Imagine 17.4 (2010): 20-21.

( Available online here )

This lesson plan, created by Stuart Gluck and Carlos Rodriguez, is part of a series of lesson plans in Philosophy in Education: Questioning and Dialogue in Schools , by Jana Mohr Lone and Michael D. Burroughs (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016) .

If you would like to change or adapt any of PLATO's work for public use, please feel free to contact us for permission at [email protected] .

Related Tools

Connect With Us!

Stay Informed

PLATO is part of a global UNESCO network that encourages children to participate in philosophical inquiry. As a partner in the UNESCO Chair on the Practice of Philosophy with Children, based at the Université de Nantes in France, PLATO is connected to other educational leaders around the world.

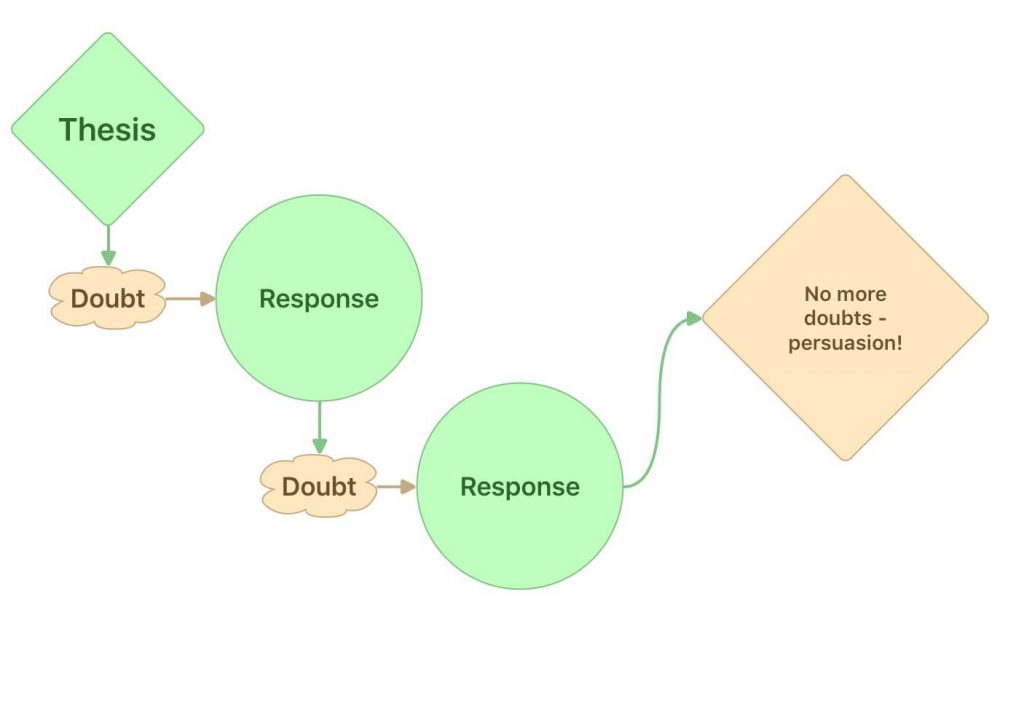

I. Definition

An argument is a series of statements with the goal of persuading someone of something. When they’re successful, arguments start with a specific point of view, something that the reader doubts ; by the end of the argument, the reader has been convinced and no longer doubts this view. In order to argue well, you have to put yourself in the reader’s position and imagine what doubts they might have about your claim.

Argument is not the same as fighting!

From watching political debates and sports analysis on TV, you might get the impression that arguments are hostile and aggressive, more intended to defeat the opponent than to persuade anyone. But this isn’t necessarily true. In fact, the best arguments come from a place of sympathy and friendship — when friends have differing points of view, they may explain the reasoning behind their view as a way of building understanding. Often this takes the form of a friendly argument or debate .

In fact, learning to argue well is one of the most important skills you can develop — in your personal and professional relationships, a certain amount of conflict and disagreement is inevitable. If you don’t know how to argue with reason and logic, then all you’re left with is fighting . An argument is all about coming to an agreement (or, if agreement is not possible, at least understanding the reasons why it’s impossible). Fighting, on the other hand, is all about expressing emotions like anger and hurt, without caring about the other person’s point of view. Argument, if you know how to do it right, can resolve differences; fighting usually just makes them worse.

II. Types of Argument

There are three basic types of argument: deductive, inductive, and mixed . They are based on three different types of inference (see next section for more on what an inference is). If you find this confusing, visit our article on Inferences for more detail.

- Deductive arguments are built from deductive inferences

- Inductive arguments are built from inductive inferences

- Mixed arguments are built from both types of inference

So what’s the difference between deductive and inductive inferences?

Deductive inferences have to be true. You start from a basic statement or “premise,” and as long as that premise is true there is no logical way for the conclusion to be false.

- If x=y, then we can deductively infer that y=x. There’s no way for that not to be true!

- If Socrates is a man and all men are mortal, then Socrates must be mortal as well.

You could always question the premises of a deductive argument (for example, you might say that Socrates is a god, not a man, and therefore question whether he’s mortal), but if you accept the premises you have no logical choice but to accept the conclusion.

Inductive inferences don’t have to be true, but probably are.

For the whole history of human experience the sun has risen in the east and set in the west; therefore, the sun will do the same thing tomorrow.

This is almost certainly true! Most people would readily accept this line of argument. However, notice that it’s a matter of probability, not a matter of logical certainty like a deductive argument. After all, it’s possible that aliens could come and destroy the sun, meaning it wouldn’t rise or set ever again. That’s extremely unlikely, but not logically impossible.

So, in strict logical terms, deductive arguments seem stronger than inductive ones. However, inductive arguments have one crucial advantage: they usually matter more. In our day-to-day life, almost all of our decisions are based on inductive inferences:

- It usually takes me an hour to get to work, so if I leave at 8:00 I’ll probably get there by 9

- Yesterday I got sick after eating Wendy’s, so I won’t go there for lunch today

- My best friend advised me not to skip class, and her advice is usually good, so I’ll follow it

These inferences are all inductive — they’re all based on reasonable probability, not absolute logical certainty.

Deductive arguments, on the other hand, are based on absolute certainty, but their conclusions are often trivial:

- y=x, so therefore x=y . But who cares? These are just different ways of writing the same equation. The first statement might be very important: y=x might be the key to solving an important algebra problem. But the deductive argument doesn’t provide any new information on top of what we already started with.

- I am a human, and all humans are primates, so therefore I am a primate . Again, does this really matter? The statement “all humans are primates” is certainly interesting in its own right, but does “I am a primate” really add anything new on top of it?

III. Argument vs. Claim vs. Inference

In short, an argument is made up of claims connected by inferences . Each individual step in the argument is a separate claim. There’s a main claim , or “thesis,” which is supported by supporting claims . As we saw in section1, the supporting claims are intended to respond to doubts about the main claim.

Inferences are usually not stated out loud; they are invisible connectors between the claims in the argument.

Think about a cover letter . A cover letter is your chance to persuade someone that they ought to hire you — it’s a kind of argument that people in nearly every line of work have to master. A cover letter might work like this (the underlined portions would be stated explicitly (claims), whereas the italic parts are just implied/anticipated (inferences)):

Thesis: You should hire me.

Expected doubt : We need someone with statistics skills, which most people don’t have

Supporting claim: I studied statistics in college.

( Hidden Inference: when people study something in college they gain skills in that subject)

Expected doubt : OK, but studying something in college doesn’t mean you can apply it

Supporting claim: I also did a market-research internship during the summer

(Hidden Inference: real-world internships teach people to apply their knowledge )

And so on. In the cover letter, each paragraph covers out one of the supporting claims, providing further support and detail. In the end, if you’ve correctly anticipated your reader’s doubts, you will persuade them that you are the best person for the job!

IV. Quotations About Argument

“I find I am much prouder of the victory I obtain over myself, when, in the very ardor of dispute, I make myself submit to my adversary’s force of reason, than I am pleased with the victory I obtain over him through his weakness.” (Michel de Montaigne)

The French essayist Montaigne had a talent for argument, and understood the importance of listening to the other person’s point of view rather than just trying to defeat it. In fact, this quote is a pretty apt summary of the difference between argument and fighting — when you argue, you always remain open to the possibility that you will be the one persuaded in the end, rather than just hanging on to your side no matter what.

“There can be no progress without head-on confrontation.” (Christopher Hitchens)

Another master of the art of argument, journalist Christopher Hitchens was an outspoken proponent of various controversial views, from politics and religion to science and literature. In all of these areas he emphasized the importance of arguments and logic, not because he was an inherently contentious man (though that may have been true — opinions differ), but mainly because he believed that the clash of ideas would lead to new, better ideas.

V. The History and Importance of Argument

Arguments are probably as old as language itself. In fact, it’s possible that language originated as a way for pre-human primates to influence one another’s behavior without resorting to violence. Imagine you’re a homo ergaster on the African savannah: you want one of your group-mates to help you search for berries, but she’s more interested in grooming. Wouldn’t it be helpful if you could reason with her and persuade her to spend her energy in a different direction? It’s possible that language evolved as, among other things, a tool for persuasion.

However it started, argument is an extremely widespread human behavior. Different cultures have different ways of going about it — different ideas, for example, of what counts as polite argument, or what sorts of topics are appropriate to argue about in a given setting. But all human beings, across the globe, use language to make claims, express doubts, and respond to those doubts.

While some rulers try to suppress argument, others historically have welcomed it. For example, the Mughal Emperor Akbar was a Muslim who ruled India from 1556-1605. He knew that his people followed many different religions and philosophies, and built temples and schools for the specific purpose of staging reasonable, enlightening arguments among all faiths and points of view. His hope was that, through argument, people of different religions would learn from each other and that eventually a new religion would emerge, combining the best insights from each tradition.

In Europe, a short time later, this sort of argument fueled the Scientific Revolution and later the Enlightenment. Drawing on the ideas of non-European thinkers in places like India, China, and the Middle East, Europeans developed a method of argument and experimentation that we call science. They also began to consider new forms of government based on arguments and persuasion rather than royal decrees and birthright — thinkers like Benjamin Franklin, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Thomas Jefferson conceived of a government founded on constant argument, both in the public square and in institutions like Congress .

VI. Argument in Popular Culture

Sports shows provide great examples of both arguments and fighting. They usually start with a controversial thesis like “Aaron Rodgers is a better quarterback than Carson Palmer.” Then the two hosts will argue back and forth over whether the thesis is true or false. Sometimes, they will listen to each other, anticipate the doubts of the other side, and respond to them rationally; other times, they just shout over each other and never make any progress towards persuasion, in which case it’s an example of fighting rather than argument.

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, this is Chewbacca. Chewbacca is a Wookiee from the planet Kashyyyk. But Chewbacca lives on the planet Endor….If Chewbacca lives on Endor you must acquit!” (Johnnie Cochran, South Park )

This line from South Park is a spoof of the real Johnnie Cochran, the lawyer in the O.J. Simpson trial, but it’s also an example of a (terrible) deductive argument. The argument is structured like this:

- If Chewbacca lives on Endor, you must acquit (find my client not guilty)

- Chewbacca lives on Endor

- Therefore, you must acquit

Statement #1 is clearly an absurd premise, but if it were true then this deductive argument would have the force of absolute logical certainty. That’s the problem with deductive reasoning : if the premises are accurate, it’s air-tight; but often they are not.

a. Deductive inferences

b. Responses to doubt

c. Inductive inferences

a. Inference

c. Fighting

a. Mixed argument

b. Supporting claim

c. Deductive reasoning

d. Inductive reasoning

a. The Enlightenment in Europe

b. The Mughal period in India

c. Medieval Islam

d. All human societies

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Back to Entry

- Entry Contents

- Entry Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Supplement to Argument and Argumentation

Historical supplement: argumentation in the history of philosophy.

Arguments and argumentation figure prominently in most (if not all) influential philosophical traditions. This Supplement presents argumentation as discussed in five prominent traditions from the past: ancient Greek, classical Indian, classical Chinese, medieval Latin, and medieval Islamicate philosophy. The goal is not to present an exhaustive historical account of these developments, but rather to offer a sample of reflections on argumentation in five noteworthy philosophical traditions.

2.2 Islamicate

1. ancient traditions.

Argumentative practices in ancient Greece constitute one of the main historical examples of a well-developed argumentative tradition (Dutilh Novaes 2020: ch. 5). The relevant sociopolitical background is that of Athenian democracy (508 to 322 BCE), where citizens could participate in decisions pertaining to governance of the city (M. Hansen 1977–81 [1991]). The three main political bodies were the assembly, the boule, and the courts of law; in all three, decisions were reached on the basis of extensive debates. Thus, being a persuasive orator was of paramount importance for a citizen, both to obtain votes in the assembly and to argue for a legal case in court.

In this setting, those who could train citizens to become skilled orators had something immensely valuable to offer. Many of the well-known thinkers of this period were exactly that: itinerant professional teachers who became collectively known as the Sophists (Notomi 2014; see entry on the Sophists ). But with the end of the so-called golden age of Athenian democracy and the disastrous results of the Peloponnesian Wars (431–404 BCE) for Athens, this mode of discursive engagement came to be criticized as a sign of the failure of democracy as a political system. Plato famously (and somewhat unfairly) offers harsh criticism of the Sophists in his dialogues (e.g., the Gorgias , the Republic ; see entry on Plato ): according to Plato, they only aim at shallow persuasion rather than at the truth (Irani 2017).

Plato promotes a different style of argumentative discourse: instead of the long speeches of the rhetoricians, and following his teacher Socrates (see entry on Socrates ), he favors dialogical interactions where speakers take turns in quick succession, in what became known as dialectical encounters . Dialectic seems to have predated Socrates and Plato, as the Eleatic philosophers (Parmenides, Zeno) were apparently already practitioners of this kind of discourse (Castelnérac & Marion 2009; see entry on Zeno of Elea ). But Plato was arguably the first to reflect and theorize on these different styles of argumentation.

What does a dialectical encounter look like, concretely? There are a number of detailed reconstructions of the basic features of this practice in the literature (Castelnérac & Marion 2009; Fink 2012). Aristotle’s Topics and its “ninth chapter”, the Sophistical Refutations , may be read as the (presumably) first regimentation/systematization of these practices, thus providing support for a general description thereof:

First of all there are the agents: the questioner and the answerer. There may also have been an audience ( Sophistical Refutations 16 175a20–30). The questioner has two main jobs: first, to extract a thesis, the “starting point” for the debate from the answerer; second, to try to force the answerer to admit the contradictory of that starting point, by getting the answerer to agree to certain premises. Alternatively, the questioner can try to reduce the thesis to absurdity. In either case, the questioner aims to refute the answerer. Crucially, the starting point should be something that can be affirmed or denied ( Topics 8.2. 158a14–22). For example, “what is knowledge?” would not be allowed as a starting point, as the answerer cannot reply “yes” or “no”. The answerer, on the other hand, has only one task, which is to remain un-refuted within a fixed time ( Topics 8.10. 161a1–15). If the answerer is refuted, then the answer should make clear that it is not their fault, but is due solely to the starting point ( Topics 8.4. 159a18–22) (Duncombe & Dutilh Novaes 2016: 3).

A key component of dialectic is the concept of refutation , or elenchus in Greek: questioner aims at refutation, answerer tries to avoid being refuted. Readers of Plato will recall the numerous instances where Socrates, by means of questions, elicits various discursive commitments from his interlocutors, only to show that, taken together, these commitments are incoherent. The interlocutor is thus refuted , and must revise their previous discursive commitments so as to restore coherence. But beyond these basic details, there is much discussion in the literature on how best to understand the concept of elenchus (Wolfsdorf 2013).

Practices of dialectic provided the background for the emergence of the first fully-fledged logical system in history, Aristotle’s syllogistic, as described in the Prior Analytics (Dutilh Novaes 2020: ch. 6; see entry on Aristotle’s logic ). Syllogistic differs from dialectic more generally in that it views as valid only arguments having the property of necessary truth-preservation (i.e., deductive arguments), whereas dialectic also allows for inductive and analogical arguments (as attested by the wide range of arguments used in Plato’s dialogues). But Aristotle remained equally interested in dialectic more generally, as attested by his manuals on how to argue well in dialectical encounters, the Topics and the Sophistical Refutations , and by the extensive discussions on dialectic even in the Prior Analytics . A key concept introduced by Aristotle in the Sophistical Refutations is that of fallacies , i.e., arguments that appear correct but are ultimately incorrect, thus leading to faulty conclusions (see entry on fallacies ). For millennia (and to this day), the identification and study of fallacies remained one of the main instruments to study argumentation.

Plato and Aristotle were not the only Greek thinkers interested in dialectic (see entry on the dialectical school ). Later authors continued to discuss the concept of dialectic, even if it acquired different meanings for different authors and traditions (see entry on ancient logic ). The Stoics are particularly worth mentioning, as they are credited with developing the first fully-fledged propositional logic, where the validity of arguments is analyzed by means of schemata where numbers take the place of propositions (whereas in Aristotle’s syllogistic, letters take the place of terms). Modus Ponens, for example, was formulated by the Stoics as:

If the 1 st , then the 2 nd . But the 1 st , therefore the 2 nd

(See entry on ancient logic .) In sum, a concern with rational discourse and argumentation was a constant element in ancient Greek philosophy, from the early stages with pre-Socratic thinkers all the way until late antiquity.

The classical Indian tradition shares with the ancient Greek tradition the pervasiveness of debating practices. In fact, it might seem that Indian thinkers relished engaging in lively debates even more than their Greek peers, as attested by their sophisticated reflections on argumentation (both for instruction and practice, and as theoretical investigations; Matilal 1998: chs 2 and 3; Solomon 1976). As is well known, classical Indian philosophy is extremely diverse, branching into a plethora of schools. These essentially fall within two groups: Brahmanical schools, which accepted the validity of the Vedic sacred texts (such as Nyāya and Yoga), and schools that rejected the authority of the Vedas (such as Buddhism and Jainism). There was much disagreement among these different schools, thus generating ample opportunity for lively discussions.

While the emergence of sustained debating practices in ancient Greece was greatly influenced by the political background, in India debating practices emerged as a response to different circumstances, in particular to address metaphysical, epistemological and religious issues (see entry on epistemology in classical Indian philosophy ). The historical record suggests that kings and rulers encouraged and patronized such debates between sages, thus providing an institutional, social embedding quite different from the background for intellectual endeavors in ancient Greece. On the whole, while the Greeks were primarily interested in moral and political issues, Indian thinkers mainly focused on ontological, epistemological, medical, and religious questions such as the distinction of the soul from the body, the purpose of life, the different sources of knowledge, and the existence of the after-life (Matilal 1998; though these discussions also had moral implications).

The popularity of debates dates back to the early stages in the history of Indian thought (as early as 1700 BCE), but the first theories of argumentation only appeared around the time of the Buddha and other religious reformers (6 th century BCE). By the third and second centuries BCE, monks and Brahmans were required to have training in the art of debating. Debating manuals were written within the different sectarian schools (Matilal 1998), containing accounts of highly regimented debating practices displaying the same level of sophistication (if not beyond) as Greek dialectic (see entry on logic in classical Indian philosophy ). The Indian authors distinguished between friendly, honest debates, where presumably the common goal was the search for truth, from competitive ones where the goal was mere victory. In the influential Nyāya-sūtra manual, attributed to Akṣapāda Gautama and widely available by 150 CE (exact dates of composition are uncertain), the former were called vāda , while the latter were called jalpa and vitaṇḍā (Nicholson 2010). These manuals contained instructions on how to perform at honest debates as well as discussions of clever argumentative tricks that may be used by disputatious opponents in competitive debates, so as to help the novice to identify and rebut these tricks (Prets 2001). In particular, Indian philosophers also developed sophisticated theories of fallacies (Phillips 2017) that served purposes similar to Aristotle’s Sophistical Refutations (Ganeri 2001).

Indian philosophical discussions also tend to have a strong epistemological focus, with a concern for the nature of evidence and discussions on the means of knowledge, pramāṇa s (see entry on epistemology in classical Indian philosophy ). The Nyāya-sūtra , for example, can be read as offering a formulation of acceptable and sound methods for philosophical discourse and inquiry. Inference ( anumāna ) was viewed by the Nyāya philosophers (as well as by other schools of thought) as one of the pramāṇa s, one of the means of knowledge. But Indian thinkers saw no contradiction between dialectical and epistemological approaches; as is clear in particular in the works of the influential fifth–sixth century CE Buddhist thinker Dignāga, inference—the cognitive process taking one from the known to the unknown—and argument—a device of persuasion—are but two sides of a single coin (see entry on logic in classical Indian philosophy, section 4 ).

There is much discussion among scholars on whether earlier Indian thinkers did or did not draw a sharp distinction between (what we now call) deductive and inductive reasoning (Siderits 2003), and between monotonic and non-monotonic reasoning (Taber 2004). Inferential knowledge was typically viewed as the product of repeated observations of individual cases, and many authors from the earlier period seemed to view these inferences as sufficiently reliable; an exception were some skeptical thinkers, who emphasized precisely the fact that these inferences were not necessarily truth-preserving (Matilal 1998; Siderits 2003). By contrast, later authors, in particular Dignāga, explicitly recognized arguments having the property of necessary truth-preservation as comprising a special class of arguments. Indeed, over the centuries theories and practices of argumentation in the Indian tradition continued to evolve, thus offering much valuable material for those interested in the history of theories of argumentation.

Chinese intellectuals were also deeply interested in argumentation (C. Hansen 1983), a practice described as biàn or biàn shuō in classical Chinese texts. In particular, the thinkers associated with the “School of Names” were especially keen on disputations, including idle contests of wits (at least according to their critics). Indeed, some of these thinkers have been described as the “Chinese sophists”, given the (at least superficial) similarities with the Greek sophists (see entry on the School of Names ). Moreover, Chinese thinkers also dealt with contexts of “mass persuasion”, that is persuasion of large groups of people (even if they were not fellow citizens like in Greece), such as groups of followers of different masters.

Biàn is in fact a more general concept, its core meaning pertaining to drawing distinctions,

as a verb referring to the act of distinguishing or discriminating things from each other and as a noun referring to distinctions. (Fraser 2013: 4)

But for these classical Chinese thinkers, a debate or argument is in fact an activity primarily aimed at drawing distinctions , hence the secondary meaning the term acquired as referring to disputation and argument. Essentially, the question in a disputation is usually whether a given name is suitably applied to a given object (or event), as revealed by a passage from the Mohist Dialectics (A74, as cited in the entry on Mohist canons (note 25) ):

Canon: Biàn is contending over converses. Winning in biàn is fitting the thing. Explanation: One calls it “ox”, the other calls it “non-ox”. This is contending over converses. These do not jointly fit the object. If they do not jointly fit, it must be that one does not fit.

While this may seem like an idle discussion, Chinese thinkers took the rectification of names to be of paramount importance. If speakers do not use names and terms uniformly, chaos and anarchy will ensue. In particular, they will not be able to follow commands as intended by their superiors, as these thinkers emphasized the action-guiding over the descriptive functions of language (see entry on the School of Names, supplement “Disputation in context” ).

While intellectuals of all main traditions in the classical period discussed (and presumably engaged in) biàn , there are three main (interrelated) accounts of argumentation in classical Chinese thought: that of the early Mohists in their rebuttal of fatalism, that of the later Mohist dialectic, and that of Xúnzǐ (a prominent thinker in the Confucian tradition; Fraser 2013). And yet, while they contain sophisticated analyses of proper and improper uses of language in disputations, they remain fundamentally different from the theories of argumentation found in Aristotle’s texts, for example, in particular in that there is no explicit articulation of inferential rules and principles—even if implicitly they seem to endorse certain principles, such as the principle of non-contradiction when stating that something cannot both be called “ox” and “non-ox” (see passage quoted above). The key concept in the Chinese context is that of analogy:

inference is thus understood as the act of distinguishing something as a certain kind of thing on the basis of having distinguished it as similar to a relevant “model” or “standard”. (Fraser 2013: 4)

As noted above, analogical reasoning is also widely present in the Greek tradition, but in the latter it coexists with other modes of reasoning, including deductive reasoning. In this respect, we may say that the property of necessary truth-preservation did not stand out for the Chinese thinkers, who were primarily concerned with language-world relations rather than with relations between sentences (as part of a more general pragmatic intellectual orientation). So here again we have an argumentative tradition tailored to the needs of its practitioners in their own sociocultural circumstances.

2. Medieval Traditions

The Latin medieval intellectual tradition is commonly thought to span from Boethius in the sixth century up to the fifteenth century and beyond. The common denominators were the use of Latin as lingua franca and its (institutional as well as intellectual) proximity with Christianity. A focus on debating and argumentation is a crucial feature of this tradition, in particular as crystalized in what is known as scholastic disputation . Scholastic disputation is a formalized, rigorous procedure for debate, based on fairly strict rules, which became one of the main approaches for intellectual inquiry in medieval Europe (Novikoff 2013). Inspired by ancient Greek argumentation methods, it was then further developed in the monasteries of the early Middle Ages. It reached its pinnacle from the twelfth century onwards, especially with the birth and growth of universities, where it became one of the main teaching methods (see entry on literary forms of medieval philosophy ). The influence of disputations went well beyond universities, expanding towards multiple spheres of cultural life.

Schematically, such disputations may be described thus:

[A disputation] is a regular form of teaching, apprenticeship and research, presided over by a master, characterized by a dialectical method which consists of bringing forward and examining arguments based on reason and authority which oppose one another on a given theoretical or practical problem and which are furnished by participants, and where the master must come to a doctrinal solution by an act of determination which confirms him in his function as master. (Bazán, Wippel, Fransen, & Jacquart 1985: 40; as quoted in the entry on literary forms of medieval philosophy )

In other words, a disputation starts with a statement, and then goes on to examine arguments in favor and against the statement. A disputation is essentially a dialogical practice in that it features two (possibly fictive) parties disagreeing on a given statement and producing arguments to defend their respective positions, even if both roles can be played by one and the same person. The goal may simply be that of convincing an interlocutor and/or the audience, but the implication is typically that something deeper is achieved, namely coming closer to the truth by examining the question from many different angles (Angelelli 1970).

Medieval intellectuals engaged in “live” disputations, both privately, between a master and a pupil, and as grand public events attended by the university community at large (Novikoff 2013). Moreover, the general structure is used extensively in some of the most prominent writings by these authors (some of them are in fact written-up versions of disputations actually having taken place, known as reportatio ). For example, Aquinas’ Summa Theologica —possibly the most influential work from the scholastic tradition—follows the structure of a disputation, with arguments for and against specific claims being examined (see entry on Thomas Aquinas ). Indeed, disputation became one of the chief methods for intellectual inquiry in general, and medieval treatises on philosophical topics typically contain a fair amount of disputational vocabulary. The widespread presence of disputation and related genres has been described as “the institutionalization of conflict” in scholasticism (see entry on literary forms of medieval philosophy ).

Logical textbooks were expected to provide the required training to excel in the art of disputation, with chapters on fallacies, consequence, the logical structure and meaning of propositions, obligationes (a special kind of disputation) etc., all of which are directly relevant for the art of disputation (see entries on medieval theories of consequence , properties of terms , and obligationes ). In fact, to a great extent Latin medieval authors did not differentiate between “ logica ” and “ dialectica ”, as attested by the fact that a number of influential logical textbooks—Abelard’s De Dialectica , Buridan’s Summulae de dialectica —bore the term “ dialectica ” in their titles. As late as in the sixteenth century, the Spanish scholastic author Domingo de Soto still defined dialectic/logic as “the art or science of disputing” (Ashworth 2011).

But elsewhere, Renaissance authors such as Lorenzo Valla (Nauta 2009; see entry on Lorenzo Valla ) were harsh critics of the genre of scholastic disputation. These authors deplored the lack of applicability of scholastic logic; Valla for example saw syllogisms as an artificial type of reasoning, useless for orators on account of being too far removed from natural ways of speaking and arguing. They condemned the cumbersome, artificial and overly technical Latin of scholastic authors, and defended a return to the classical Latin of Cicero and Vergil. Many Renaissance authors did not belong to the university system, where scholasticism was still the norm in the fifteenth century; instead, many were civil servants, and were thus involved in politics, administration, and civic life in general. As such, they were much more interested in rhetoric and persuasion than in logic and demonstration (Dutilh Novaes 2017).

The demise of scholasticism was a gradual process, and for centuries the logic taught at universities was still based on general Aristotelian theories such as syllogistic. But as a whole, logic and argumentation became less prominent topics of discussion for thinkers in the early modern period (Dutilh Novaes 2020: ch. 7). One exception is the so-called Port Royal Logic (1662), which presented itself explicitly as a manual on the art of thinking, but which contains extensive discussions on modes of arguing as well (see entry on Port Royal logic ).

With the advent of Islam in the seventh century, a new cultural and intellectual tradition was initiated; alongside the novelty of Islam, it drew significantly from earlier sources such as ancient Greek philosophy and also Persian and Arabic sources (among others). (The term “Islamicate” is used to refer to what pertains to regions in which Muslims are culturally dominant, but not specifically to the religion of Islam as such.) The primary language of learning in this tradition was Arabic, but significant texts were also written in Persian, Turkish and Hebrew (among other languages).

In this tradition, the term jadal was generally used to refer to argumentative practices and accompanying theories; it is commonly translated as “dialectic” or “disputation theory” (Young 2017; Miller 2020). Islamicate theories of argumentation come in many kinds, emerging within specific fields of inquiry such as theology and later jurisprudence, but also as domain-independent reflections on how to reason and argue well, in particular but not exclusively in connection with logic and ancient Greek sources such as Aristotle (see entry on Arabic and Islamic philosophy of language and logic ).

The advent of the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258) marked the beginning of systematic efforts to translate a wide range of ancient Greek texts, in particular texts by Aristotle and his commentators, under the protection and sponsorship of these rulers. The translation movement culminated around 830 in the circle of al-Kindî in Baghdad, and inaugurated the intellectual tradition of falsafa (an alliteration for the Greek word “ philosophia ”), which, at least initially, was viewed as a competitor for the “local” traditions of kalam (rational theology) and fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) (Miller 2020; see entries on Greek sources in Arabic and Islamic philosophy and on Arabic and Islamic natural philosophy and natural science ). The latter also offered accounts of reasoning and argumentation (in their specific domains), but until the eleventh century there was little cross-pollination between them and Greek-inspired logic and philosophy.

The earliest fully-fledged theories of jadal emerged in theological contexts, around the turn of the ninth to the tenth century (Miller 2020: ch. 2). For these theologians, jadal is a method for attaining truth, used by God in disputing with the Jews, and taught by God to his prophet. The focus is thus predominantly epistemological, but jadal is said to explicitly involve at least two people (thus being different from solitary speculation) who exchange questions and answers. The ultimate goal is to defend and prove the truth of Islam in contexts of religious disputes. The authors in this tradition wrote detailed treatises that included discussions of rules of conduct during debates, objections and counter-objections, and signs of defeat. The theological tradition of jadal then provided the substratum for the development of dialectical theories of jurisprudence (Miller 2020: ch. 4).

Within falsafa , argumentation was initially studied from the perspective of the Aristotelian Organon . By the early tenth century, a group of self-declared Peripatetics in Baghdad presented themselves as the defenders of Aristotelian orthodoxy. The most famous member of this group was al-Farabi, who composed a series of commentaries on the books of the Organon , including an influential commentary on Aristotle’s Topics , which was known as the Book of Dialectic ( Kitāb al-Jadal ; (DiPasquale 2019; see entries on al-Farabi and al-Farabi’s philosophy of logic and language ). At this stage, unsurprisingly, these thinkers were predominantly interested in the key topics of Aristotle’s logical canon such as syllogistic, dialectic, and demonstration, and developed detailed theories on argumentation (Miller 2020: ch. 3).

All this was to change thanks to the larger-than-life figure of Ibn Sina (Avicenna; ca. 970–1037; see entry on Ibn Sina ). Ibn Sina reoriented the Aristotelian conception of logic as closely connected with dialectic and argumentation towards a more epistemological, mentalistic approach (see entry on Ibn Sina’s logic ). Ibn Sina went on to become the most influential thinker in the Islamicate tradition in subsequent centuries, and this meant that the study of logic, referred to as mantiq , became by and large divorced from jadal .

In later periods, the “foreign” theories of the falsafa tradition were finally (partially) incorporated into the original traditions in jurisprudence, law and theology, in particular with the rise of the madrasa system starting in the late eleventh century (El-Rouayheb 2016; madrasas were official institutions of learning, functionally similar to European universities). In the madrasas, the Arabic scholastic method became consolidated and widely disseminated (see entry on Arabic and Islamic philosophy of language and logic ). But theories of disputation tended to be studied as an independent discipline, called “the science of disputation” ( 'ilm al-munazara ) or “the rules of discussion” ( ādāb al-baḥth ), whereas logic ( mantiq ) remained focused on epistemological concerns. As described by Miller (2020: 103),

ādāb al-baḥth emerged as an independent intellectual discipline and literary genre by adopting concepts from Aristotelian logic and philosophy as well as rules formulated in the context of both juridical and theological dialectics. (The earliest works in the ādāb al-baḥth tradition date to the first half of the 14 th century)

Thus, over the centuries, authors and thinkers in the Islamic World produced sophisticated theories of argumentation, and this from different angles, in particular theology, law, and philosophy.

Copyright © 2021 by Catarina Dutilh Novaes < cdutilhnovaes @ gmail . com >

- Accessibility

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2023 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Department of Philosophy, Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

Quick Links

Current Courses Don Berkich: PHIL 2306.001: Intro to Ethics PHIL 2306.003: Intro to Ethics Minds and Machines Resources Reading Philosophy Writing Philosophy

- This Semester

- Next Semester

- Past Semesters

- Descriptions

- Two-Year Rotation

- Double-Major

- Don Berkich

- Stefan Sencerz

- Glenn Tiller

- Administration

- Philosophy Club

- Finding Philosophy

- Reading Philosophy

- Writing Philosophy

- Philosophy Discussions

- The McClellan Award

- Undergraduate Journals

- Undergraduate Conferences

James Pryor, "What Is an Argument?

An argument is not the same thing as a quarrel. The goal of an argument is not to attack your opponent, or to impress your audience. The goal of an argument is to offer good reasons in support of your conclusion , reasons that all parties to your dispute can accept.

Nor is an argument just the denial of what the other person says. Even if what your opponent says is wrong and you know it to be wrong, to resolve your dispute you have to produce arguments. And you haven't yet produced an argument against your opponent until you offer some reasons that show him to be wrong.

Here's a sample argument. The premises are in red.

- No one can receive an NYU degree unless he or she has paid tuition to NYU.

- Shoeless Joe Jackson received an NYU degree.

- So, Shoeless Joe Jackson paid tuition to NYU.

In this argument, it is clear what the premises are, and what the conclusion is. Sometimes it will take skill to identify the conclusion and the premises of an argument. You will often have to extract premises and conclusions from more complex and lengthy passages of prose. When you do this, it is helpful to look out for certain key words that serve as indicators or flags for premises or conclusions.

Some common premise-flags are the words because , since , given that , and for . These words usually come right before a premise. Here are some examples:

Your car needs a major overhaul, for the carburetor is shot.

My Given that euthanasia is a common medical practice, the state legislatures ought to legalize it and set up some kind of regulations to prevent abuse.

Because euthanasia is murder, it is always morally wrong.

We must engage in affirmative action, because America is still a racist society.

Since abortion is a hotly contested issue in this country, nobody should force his opinion about it on anyone else.

Some common conclusion-flags are the words thus , therefore , hence , it follows that , so , and consequently . These words usually come right before a conclusion. Here are some examples:

You need either a new transmission, or a new carburetor, or an entirely new car; so you had better start saving your pennies.

Affirmative action violates the rights of white males to a fair shake; hence it is unjust.

It is always wrong to kill a human being, and a fetus is undoubtedly a human being. It follows that abortion is always wrong.

A woman's right to control what happens to her body always takes precedence over the rights of a fetus. Consequently , abortion is always morally permissible.

Euthanasia involves choosing to die rather than to struggle on. Thus , euthanasia is a form of giving up, and it is therefore cowardly and despicable.

Authors do not always state all the premises of their arguments. Sometimes they just take certain premises for granted. It will take skill to identify these hidden or unspoken premises. We will discuss this more later.

Whether an argument convinces us depends wholly on whether we believe its premises, and whether its conclusion seems to us to follow from those premises. So when we're evaluating an argument, there are two questions to ask:

- Are its premises true and worthy of our belief?

- Does its conclusion really follow from the premises?

These are completely independent issues. Whether or not an argument's premises are true is one question; and whether or not its conclusion follows from its premises is another, wholly separate question.

If we don't accept the premises of an argument, we don't have to accept its conclusion, no matter how clearly the conclusion follows from the premises. Also, if the argument's conclusion doesn't follow from its premises, then we don't have to accept its conclusion in that case, either, even if the premises are obviously true.

So bad arguments come in two kinds. Some are bad because their premises are false; others are bad because their conclusions do not follow from their premises. (Some arguments are bad in both ways.)

If we recognize that an argument is bad, then it loses its power to convince us. That doesn't mean that a bad argument gives us reason to reject its conclusion. The bad argument's conclusion might after all be true; it's just that the bad argument gives us no reason to believe that the conclusion is true.

Let's consider our sample argument again:

In this argument, the conclusion does in fact follow from the premises, but at least one of the premises is false. It's not true that one has to pay tuition in order to receive an NYU degree. (NYU gives out a number of honorary degrees every year to people who were never NYU students, and never paid tuition.) Probably the other premise is false, too: as far as I know, Shoeless Joe Jackson did not ever receive an NYU degree. So this argument does not, by itself, establish that Shoeless Joe Jackson paid tuition to NYU.

- College of Liberal Arts

- Bell Library

- Academic Calendar

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2 Evaluating Arguments

Nathan Smith

One particularly relevant application of logic is assessing the relative strength of philosophical claims. While the topics covered by philosophers are fascinating, it is often difficult to determine which positions on these topics are the right ones. Many students are led to think that philosophy is just a matter of opinion. After all, who could claim to know the final answer to philosophical questions?

It’s not likely that anyone will ever know the final answer to deep philosophical questions. Yet there are clearly better and worse answers; and philosophy can help us distinguish them. This chapter will give you some tools to begin to distinguish which positions on philosophical topics are well-founded and which are not. When a person makes a claim about a philosophical subject, you should ask, “What are the arguments to support that claim?” Once you have identified an argument, you can use these tools to assess whether it’s a good or bad one, whether the evidence and reasoning really support the claim or not.

In broad terms, there are two features of arguments that make them good: (1) the structure of the argument and (2) the truth of the evidence provided by the argument. Logic deals more directly with the structure of arguments. When we examine the logic of arguments, we are interested in whether the arguments have the right architecture, whether the evidence provided is the right sort of evidence to support the conclusion drawn. However, once we try to evaluate the truth of the conclusion, we need to know whether the evidence is true. We’ll look at both of these considerations in what follows.

Inference and Implication: Why Conclusions Follow from Premises

An argument is a connected series of propositions, some of which are called premises and at least one of which is a conclusion. The premises provide the reasons or evidence that supports the conclusion. From the point of view of the reader, an argument is meant to persuade the reader that, once the premises are accepted as true, the conclusion follows from them. If the reader accepts the premises, then she ought to accept the conclusion. The act of reasoning that connects the premises to the conclusion is called an inference . A good argument supports a rational inference to the conclusion, a bad argument supports no rational inference to the conclusion. [1]

Consider the following example:

- All human beings are mortal.

- Socrates is a human being.

- [latex]/ \therefore[/latex] Socrates is mortal.

This argument asserts that Socrates is mortal. It does so by appealing to the fact that Socrates is a human being, together with the idea that all human beings are mortal. There is clearly a strong connection between the premises and conclusion. Imagine a reader who accepts both premises but denies the conclusion. This person would have to believe that Socrates is a human being and that all human beings are mortal, but still deny that Socrates is mortal. How could such a person maintain that belief? It just doesn’t seem rational to believe the premises but deny the conclusion!

Now consider the following argument:

- I saw a black cat today.

- My knee is aching.

- [latex]/ \therefore[/latex] It is going to rain.

Suppose that it does, in fact, rain and the person who advances this argument believes that it is going to rain. Is that person justified in their belief that it will rain? Not based on the argument presented here! In this argument, there is a very weak connection between the premises and the conclusion. So, even if the conclusion turns out to be true, there is no reason why a reader ought to accept the conclusion given these premises (there may be other reasons for thinking it is going to rain that are not provided here, of course). The point is that these premises do not provide the right sort of evidence to justify the conclusion.

So far, I have described the connection between premises and conclusion in terms of the psychological demand placed on a reader of the argument. However, we can describe this connection from another perspective. We can say that the premises of an argument logically imply a conclusion. Either way of speaking is correct. What they assert is that good arguments present a strong connection between the truth of the premises and the truth of the conclusion. In the next few sections, we will examine three different types of logical connection, each with its own rules for evaluation. Sometimes logical implication is guaranteed (as in the case of deductive arguments ), sometimes the logical connection only ensures the conclusion is probable (as with inductive and abductive arguments ).

Deductive Arguments

Deductive arguments are the most common type of argument in philosophy, and for good reason. Deductive arguments attempt to demonstrate that the conclusion follows necessarily from the premises. As long as the premises of a good deductive argument are true, the conclusion is true as a matter of logic. This means that if I know the premises are true, I know with one-hundred percent certainty that the conclusion is also true! This may be hard to believe; after all, how can we be absolutely certain about anything? But notice what I am saying: I am not saying that we know the conclusion is true with one-hundred percent certainty. I am saying that we can be one-hundred percent certain the conclusion is true, on the condition that the premises are true. If one of the premises is false, then the conclusion is not guaranteed.

Here are two examples of good deductive arguments. They are both valid and have true premises. A valid argument is an argument whose premises guarantee the truth of the conclusion. That is, if the premises are true, then it is impossible for the conclusion to be false. A valid deductive argument whose premises are all true is called a sound argument .

- If it rained outside, then the streets will be wet.

- It rained outside.

- [latex]/ \therefore[/latex] The streets are wet.

- Either the world ended on December 12, 2012 or it continues today.

- The world did not end on December 12, 2012.

- [latex]/ \therefore[/latex] The world continues today.

Hopefully, you can see that these arguments present a close connection between the premises and conclusion. It seems impossible to deny the conclusion while accepting that the premises are all true. This is what makes them valid deductive arguments. To show what happens when similar arguments employ false premises, consider the following examples:

- If Russia wins the 2018 FIFA World Cup, then Russia is the reigning FIFA world champion [in 2019].

- Russia won the 2018 FIFA World Cup.

- [latex]/ \therefore[/latex] Russia is the reigning FIFA world champion [in 2019].

- Either snow is cold or snow is dry.

- Snow is not cold.

- [latex]/ \therefore[/latex] Snow is dry.

You may recognize that these arguments have the same structure as the previous two arguments. That is, each expresses the same connection between the premises and conclusion, and they are all deductively valid. However, these latter two arguments have at least one false premise and this false premise is the reason why these otherwise valid arguments reach a false conclusion. In the case of these arguments, the structure is good, but the evidence is bad.

Deductive arguments are either valid or invalid because of the form or structure of the argument. They are sound or unsound based on the form, plus the content. You might become familiar with some of the common forms of arguments (many of them have names) and once you do, you will be able to tell when a deductive argument is invalid.

Now let’s look at some invalid deductive arguments. These are arguments that have the wrong structure or form. Perhaps you have heard a playful argument like the following:

- Grass is green.

- Money is green.

- [latex]/ \therefore[/latex] Grass is money.

Here is another example of the same argument:

- All tigers are felines.

- All lions are felines.

- [latex]/ \therefore[/latex] All tigers are lions.

These arguments are examples of the fallacy of the undistributed middle term . The name is not important, but you may recognize what is going on here. The two types of objects in each conclusion are each a member of some third type, but they are not members of each other. So, the premises are all true, but the conclusions are false. If you encounter an argument with this structure, you will know that it is invalid.

But what do you do if you cannot immediately recognize when an argument is invalid? Philosophers look for counterexamples. A counterexample is a scenario in which the premises of the argument are true while the conclusion is clearly false. This automatically shows that it is possible for the argument’s premises to be true and the conclusion false. So, a counterexample demonstrates that the argument is invalid. After all, validity requires that if the premises are all true, the conclusion cannot possibly be false. Consider the following argument, which is an example of a fallacy called affirming the consequent :

- The streets are wet.

- [latex]/ \therefore[/latex] It rained outside.

Can you imagine a scenario where the premises are true, but the conclusion is false?

What if a water main broke and flooded the streets? Then the streets would be wet, but it may not have rained. It would still remain true that if it had rained, the streets would be wet, but in this scenario even if it didn’t rain, the streets would still be wet. So, the scenario where a water main breaks demonstrates this argument is invalid.

The counterexample method can also be applied to arguments where there is no clear scenario that makes the premises true and the conclusion false, but we will have to apply it a little differently. In these cases, we need to imagine another argument that has exactly the same structure as the argument in question but uses propositions that more easily produce a counterexample. Suppose I made the following argument:

- Most people who live near the coast know how to swim.

- Mary lives near the coast.

- [latex]/ \therefore[/latex] Mary knows how to swim.

I don’t know if Mary knows how to swim, but I do know that this argument does not provide sufficient reasons for us to know that Mary knows how to swim. I can demonstrate this by imagining another argument with the same structure as this argument, but the premises of this argument are clearly true while its conclusion is false:

- Most months in the calendar year have at least 30 days.

- February is a month in the calendar year.

- [latex]/ \therefore[/latex] February has at least 30 days.

To review, deductive arguments purport to lead to a conclusion that must be true if all the premises are true. But there are many ways a deductive argument can go wrong. In order to evaluate a deductive argument, we must answer the following questions:

- Are the premises true? If the premises are not true, then even if the argument is valid, the conclusion is not guaranteed to be true.

- Is the form of the argument a valid form? Does this argument have the exact same structure as one of the invalid arguments noted in this chapter or elsewhere in this book? [2]

- Can you come up with a counterexample for the argument? If you can imagine a case in which the premises are true but the conclusion is false, then you have demonstrated that the argument is invalid.

Inductive Arguments

Almost all of the formal logic taught to philosophy students is deductive. This is because we have a very well-established formal system, called first-order logic, that explains deductive validity. [3] Conversely, most of the inferences we make on a daily basis are inductive or abductive. The problem is that the logic governing inductive and abductive inferences is significantly more complex and more difficult to formalize than deductive inferences.

The chief difference between deductive arguments and inductive or abductive arguments is that while the former arguments aim to guarantee the truth of the conclusion, the latter arguments only aim to ensure that the conclusion is more probable . Even the conclusions of the best inductive and abductive arguments may still turn out to be false. Consequently, we do not refer to these arguments as valid or invalid. Instead, arguments with good inductive and abductive inferences are strong ; bad ones are weak . Similarly, strong inductive or abductive arguments with true premises are called cogent .

Here’s a table to help you remember these distinctions:

Inductive inferences typically involve an appeal to past experience in order to infer some further claim directly related to that experience. In its classic formulation, inductive inferences move from observed instances to unobserved instances, reasoning that what is not yet observed will resemble what has been observed before. Generalizations, statistical inferences, and forecasts about the future are all examples of inductive inference. [4] A classic example is the following:

- The Sun rose today.

- The Sun rose yesterday.

- The Sun has risen every day of human history.

- [latex]/ \therefore[/latex] The Sun will rise tomorrow.

You might wonder why this conclusion is merely probable. Is there anything more certain than the fact that the Sun will rise tomorrow? Well, not much. But at some point in the future, the Sun, like all other stars, will die out and its light will become so faint that there will be no sunrise on the Earth. More radically, imagine an asteroid disrupting the Earth’s rotation so that it fails to spin in coordination with our 24-hour clocks—in this case, the Sun would also fail to rise tomorrow. Finally, any inference about the future must always contain a degree of uncertainty because we cannot be certain that the future will resemble the past. So, even though the inference is very strong, it does not provide us with one-hundred percent certainty.

Consider the following, very similar inference, from the perspective of a chicken:

- When the farmer came to the coop yesterday, he brought us food.

- When the farmer came to the coop the day before, he brought us food.

- Every day that I can remember, the farmer has come to the coop to bring us food.

- [latex]/ \therefore[/latex] When the farmer comes today, he will bring food.

From a chicken’s perspective, this inference looks equally as strong as the previous one. But this chicken will be surprised on that fateful day when the farmer comes to the coop with a hatchet to butcher her! From the chicken’s perspective, the inference may appear strong, but from the farmer’s perspective, it’s fatally flawed. The chicken’s inference shares some similarities with the following example:

- A recent poll of over 5,000 people in the USA found that 85% of them are members of the National Rifle Association.

- The poll found that 98% of respondents were strongly or very strongly opposed to any firearms regulation.

- [latex]/ \therefore[/latex] Support of gun rights is very strong in the USA.