Home — Essay Samples — Environment — Animal Welfare — The Care About Animal Welfare

The Care About Animal Welfare

- Categories: Animal Welfare

About this sample

Words: 403 |

Published: Dec 18, 2018

Words: 403 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Works Cited

- American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. (n.d.). Animal welfare.

- Animal Welfare Institute. (n.d.). Our mission. Retrieved from https://awionline.org/content/our-mission

- Compassion in World Farming. (n.d.). About us. Retrieved from https://www.ciwf.org/about-us/

- Humane Society International. (n.d.). Our mission. Retrieved from https://www.hsi.org/what-we-do/

- RSPCA Australia. (n.d.). What is animal welfare?

- World Animal Protection. (n.d.). Our vision and mission.

- Animal Welfare Act of 1966, Pub. L. No. 89-544, 80 Stat. 350 (1966).

- Grandin, T. (2017). Animals make us human: Creating the best life for animals. Mariner Books.

- Rollin, B. E. (2011). Animal rights and human morality (3rd ed.). Prometheus Books.

- Singer, P. (2009). Animal liberation (4th ed.). Harper Perennial.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Environment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 776 words

2 pages / 962 words

5 pages / 2419 words

2 pages / 942 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Animal Welfare

I visited an animal shelter for my community service. I saw and learned things there that relate to our class discussion of inequality and social norms. Specifically, I want to talk about puppies and kittens being adopted more, [...]

Man’s best friend has become scientists’ guinea pig. Over and over again, scientists have pushed the government for public funding towards animal cloning. However, animal cloning is morally wrong. Cloning animals is just as [...]

Most people experience mixed feelings of amazement and pity when seeing exotic or wild animals at the zoo. With over 200 million people visiting zoos annually, society is amazed at the existence of wild and exotic animals, but [...]

The Konark temple in the state of Odisha is one of the most recognized tourist place in India. It is famous for its Culturally enrich large Sun temple at the beautiful Shore of Bay of Bangal. The temple is now not in its [...]

Animal testing is the procedure of using non-human animals to control changes that may affect biological systems or behaviors in experiments. Because animals and humans have similar properties, the process of animal [...]

Nowadays Plastic is everywhere in today’s lifestyle. The disposal of plastic wastes is a great problem. These are non-biodegradable product due to which these materials pose environmental pollution and problems like breast [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

What Is Animal Welfare and Why Is It Important?

Though critics argue that advocating for animal welfare only cements animals’ exploitation in laboratories, on farms, and in other industrial situations, strengthening welfare standards makes these animals' lives more bearable.

T he term “animal welfare” can evoke a sense of calm or well-being for the conscious consumer, especially when it appears on a carton of eggs or a jug of milk proclaiming that animals were treated humanely during the creation of these products. But these claims often obscure the dark realities of where and how these products were made—on factory farms that systematically condemn animals to lives of extreme confinement, stress, pain, and even torture.

This article will explore what animal welfare means, why it matters, and how welfare standards are too-often violated.

What is animal welfare?

Animal welfare pertains to the living conditions of animals who are kept in captivity or are otherwise under human control. In this way, animal welfare is synonymous with human control of animals.

As a guiding philosophy for legislation and regulations, animal welfare attempts to mitigate the suffering of human-controlled animals and to ensure a minimum standard of living conditions and treatment. Welfare standards can be applied to farms, laboratories, pet stores, horse ranches, and entertainment facilities, although standards differ widely based on the species and how animals are used.

What's the difference between animal rights and animal welfare?

While both animal rights and animal welfare are oriented towards the well-being of individual animals, they differ significantly . Animal rights advocates believe that every animal deserves the right to live a life free from human control. Veganism—refraining from using or consuming animal products—is a lifestyle commonly adopted by proponents of this philosophy.

Conversely, animal welfare implicitly reinforces human use of animals, because welfare is applied to situations where animals are under the control of humans. These include facilities such as farms, where animals are being used (and/or killed) to create products or food for humans.

Notably, some argue that a person can be both an animal rights advocate and an animal welfare advocate. For example, if one's ultimate goal is to achieve animal rights, they may work in the meantime to advance animal welfare.

What is the Animal Welfare Act?

Signed into law by Lyndon B. Johnson in 1966, the Animal Welfare Act (AWA) is federal legislation in the United States designed to prevent animal cruelty and abuse within laboratories, the entertainment industry (e.g., zoos, circuses), and captive breeding. The act provides the legal framework for dealing with unnecessary cruelty and is enforced by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Despite the progressive underpinnings of the AWA, it leaves much to be desired by not protecting many animals who do not fall beneath its purview. For example, rats and mice who are used extensively in laboratories and subjected to extremely painful procedures like vivisection—or the dissection of living animals—are not protected by the act.

Farmed animals of all kinds are also excluded from the AWA, despite the fact that these animals account for the greatest numbers of animals who routinely endure cruelty and abuse on factory farms and in slaughterhouses. Farmed chickens, turkeys, cows, and pigs would arguably benefit the most from the legislation, yet they remain unprotected.

The Five Freedoms of Animal Welfare

The Five Freedoms of Animal Welfare, which were written by Irish medical scientist Francis Brambell in 1965 and codified by the UK's Farm Animal Welfare Council in 1979, represent the bare minimum of living standards that animals in captivity should have:

- Freedom from thirst and hunger

- Freedom from discomfort by providing adequate shelter

- Freedom from disease, pain, or injury

- Freedom from distress and fear

- Freedom to engage in natural behaviors

Unfortunately, there is room for interpretation in these guidelines that often disadvantages animals. For example, if animals are allowed to engage in some natural behaviors—such as chickens being allowed to perch and spread their wings, as opposed to being locked in battery cages where they can do neither of these things—this is seen as sufficiently maintaining their welfare. However, perching in a factory farm still means birds are confined to one indoor room for the duration of their drastically shortened lives.

On factory farms, animals are denied most if not all of the natural behaviors they would otherwise engage in. This has serious consequences for their physical and psychological health.

Animal welfare issues

Animal welfare issues can arise in any situation where animals are being used by humans, whether for food, entertainment, or experimentation. Below are a few examples of human activities that often impinge on animal welfare.

Animal testing

The US animal testing industry subjects 25 million animals to cruel tests each year. Rabbits, mice, guinea pigs, and other animals regularly undergo stressful operations and experiments. Some are restrained in devices while substances are dripped into their eyes, while others are force-fed or endure painful operations. Laboratory animals are often kept within stainless steel enclosures for much of their lives.

Lack of behavioral enrichment

Behavioral enrichment refers to the features added to animals’ living spaces meant to provide mental stimulation. Boredom is a common cause of mental distress for captive animals. In zoos, items such as tires, barrels stuffed with food, or artificial rocks or trees are meant to simulate wild environments and provide relief from restlessness. However, these additions still do not approximate a natural life, which is defined by choice, exploration, and variety. Zoos and aquariums may not seem as horrific as factory farms, but they remain problematic .

Animals on factory farms often live without any behavioral enrichment whatsoever. This extreme trauma triggers stress-induced behaviors such as chewing on the bars of their cages, attacking other animals, and even cannibalism.

Farmed animals

The most prevalent source of animal welfare violations in the US, based on the sheer number of animals affected, are farmed animals. Life within the industrial agricultural system means undergoing routine mutilations without anesthetics. Cows, pigs , and sheep have their tails removed, and portions of chickens’ beaks are often sliced off at a young age. These animals live in dark, crowded, unsanitary enclosures that are largely if not entirely indoors. Generally speaking, factory farms prioritize cost-efficiency and profits over animal welfare.

Blood sport

In blood sports—such as bullfighting or dogfighting—it is often the pain of an animal that provides the attraction for human audiences, leading to many welfare concerns. Dogfighting and cockfighting involve raising animals in tight confines, conducting invasive breeding activities, and forcing two animals to fight until they reach the point of serious injury or death. In bullfighting, bulls are stabbed repeatedly while being goaded around a ring in a stadium filled with cheering people. Blood sports offer the opposite of quick, painless deaths.

Sport hunting

Sport hunting is the killing of animals for fun, rather than food, and is usually carried out without regard for animal welfare. Species such as deer, rabbits, ducks, and bears are common targets of sport hunting in North America, where they're killed with weapons such as guns or crossbows. While hunters often try to kill animals with one shot, the animals are often grievously wounded instead. Many escape their hunter(s) only to die later from their wounds, slowly and painfully.

While game hunting usually refers to the legal hunting of animals, poaching usually means hunting outside the law. It's another form of vicious exploitation that's generally conducted without any regard for animal welfare. The lucrative trade in pangolins , for example, sees nearly 3 million of these animals caught from the wild each year and shipped over great distances, sometimes for weeks at a time. (They're then killed for their scales or meat.) Elephants, rhinoceroses, tigers, and gorillas are also heavily poached. Elephants and rhinos often have their tusks and horns cut away from their faces while the animals are still alive.

It's difficult to kill a whale quickly, which is among the many reasons why the hunting of whales is rife with welfare issues. Particularly in larger whales, it can take a long time—sometimes minutes, sometimes hours—for a whale to finally succumb to a harpoon. A variety of weapons have been devised over the years to hasten the demise of whales, including explosive harpoons that detonate inside a whale’s body. But even these can take up to 25 minutes .

To make matters worse, whales are often in full view of their family members as they die.

Overpopulation in companion animals

When companion animals like dogs and cats aren’t spayed or neutered, they can inadvertently contribute to America's overpopulation problem, where there aren’t enough people willing to adopt the number of animals available. In these cases, animals are either abandoned to fend for themselves, or dropped at shelters. Life at a shelter can be stressful for animals because they're usually kept in cages where they don't have much room to move around.

While many shelters adopt policies to never kill animals (these are known as no-kill shelters), others euthanize animals who are deemed unadoptable. Euthanization at shelters typically meets the highest welfare standards, but it's still a tragic and avoidable outcome. The ASPCA estimates that 1.5 million dogs and cats are put down at US shelters every year.

Puppy mills

Puppy mills, unlike more legitimate dog breeders, present serious welfare concerns for the many animals in their care. Pregnant dogs in puppy mills can be locked within cages for the duration of their lives, made to churn out puppies until their bodies give out. Their offspring are taken from them soon after birth, only to endure their own traumatic experiences of crowding, malnutrition, and unsanitary conditions before being shipped to pet stores or other sellers and sold to an often unsuspecting public.

Puppies born in puppy mills can also have psychological and physical disorders that make them difficult to cohabitate with, and which sometimes lead to premature death.

Why is animal welfare important?

Though some critics argue that animal welfare only cements animals’ exploitation on farms, in laboratories, and in other industrial situations, welfare standards are effective in making the lives of animals more bearable. The Humane League and our supporters have succeeded in convincing some slaughterhouses to stop using killing methods that cause prolonged pain for chickens, and in persuading some factory farms to end extreme confinement of chickens. These are major milestones in the movement to end the abuse of animals raised for food.

While these changes may seem incremental in the face of a powerful industry that largely regards animals as inanimate objects rather than intelligent and sensitive beings, without welfare advocates, these animals' lives would be even more tortured and painful. A chicken who is allowed to grow at a less rapid rate, who is able to stand up without breaking any bones, who has room to spread their wings and move around, and who will be spared the horrors of live-shackle slaughter represents a very real, tangible improvement over the alternative.

It's a tragic reality that the intersection of human and animal lives so often results in pain and suffering for animals. Strengthening welfare standards not only improves the lives of animals; it can also educate the public about the harsh conditions animals face in places like factory farms and laboratories.

The conversation around animal welfare is constantly evolving, and it features many different viewpoints even from advocates with the same ultimate goals. Still, this ongoing dialogue and the actions it inspires continue to pull our society toward better conditions for animals. One day, progress in our movement ideally will result in all animals' liberation from the worst of human treatment.

More like this

How Meat Chickens Are Raised, Treated, and Killed

Broiler chickens on factory farms are treated more like inanimate objects than living beings. Their brutal conditions also pose grave risks to human health and worker safety.

6 Cruel Ways That Pigs Are Abused on Factory Farms

Pigs are subjected to horrific conditions on factory farms, but their suffering is unseen. Learn the truth about what happens behind closed doors.

- Board Members

- Mission Statements

- Position Statements

- NAIA Position Statements

- NAIA Campaigns

- Homes For Animal Heroes

- NAIA Shelter Project

- Advocacy Center's Mission

- The Advocates

- The Position Statements

- NAIA Rescue

- Discover Animals

- Consider The Source

- Events Calendar

- NAIA Videos

- Press Center

- Animal Heroes 2020 Virtual 5K

- Donate your car to NAIA

- NAIA Brochures and Handouts

- Legal and Legislative Resources

- The Case Against Animal Rights and Environmental Extremism

- Sites of Interest

- NAIA Articles

- Press Releases

- Heroes, Winners and Success Stories

- White Papers

- Guest Editorials and Commentary

Our Programs

Learn More About NAIA

Join & Participate

Donate Now!

What is animal welfare and why is it important, the difference between animal rights & animal welfare.

Some people use the terms animal welfare and animal rights interchangeably, suggesting that they represent the same concerns, principles and practices. But the differences between the two are significant and irreconcilable.

What is Animal Welfare?

In its simplest form, animal welfare refers to the relationships people have with animals and the duty they have to assure that the animals under their care are treated humanely and responsibly.

Despite its current popularity, interest in animal welfare is not a modern phenomenon. Concern for animal care and wellbeing has existed since domestication, which occurred at least 10,000 years ago in Neolithic times . Our appreciation and respect for animals led to their domestication, animal agriculture and animal husbandry , the branch of agriculture that deals with the care and breeding of animals. Many historians consider the development of agriculture to be the most important event in all of human history.

The animal welfare ethic that developed in the Neolithic era is one that obligated people to consider their animals’ welfare in order to achieve their own purposes. It set in place a mutually beneficial arrangement between people and animals that goes like this: “If we take care of the animals, the animals will take care of us.” In this ancient but enduring pact, self-interest demanded that people take good care of their animals. Amazingly, this very fundamental animal welfare ethic survives today, especially in settings where hands-on animal care continues. Today we call this special relationship the human-animal bond .

Dr. Bernard Rollin , an animal science professor at Colorado State University, argues however, that 20th century technology broke this ancient contract when it allowed us to put animals into environments and uses that didn't impair their productivity but harmed their well-being.

That defines the challenge today, the need to provide acceptable levels of animal welfare in a nation that is no longer rural and agricultural , but which in the span of 2 paradigm-shifting centuries has become urbanized and technological . In modern American society only 2% of an ever-increasing population lives on farms and only 1% practices farming as an occupation . This contrasts sharply with the mid 1800’s when 90% of Americans were farmers . If these trends continue, farming will become more concentrated in the future, a situation that makes animal welfare an even more important subject.

Animal Welfare Principles & Policies

- The American Kennel Club’ Care and Conditions Policy

- The Novartis Animal Welfare Policy for Animals in Research

- The American Zoological Association’s Animal Husbandry and Welfare Policy

- The American Medical Veterinary Association (AVMA) Animal Welfare Principle

- The Five Freedoms is a widely cited animal welfare document both in Europe and in the United States

The Five Freedoms:

- Freedom from Hunger and Thirst - by ready access to fresh water and a diet to maintain full health and vigour.

- Freedom from Discomfort - by providing an appropriate environment including shelter and a comfortable resting area.

- Freedom from Pain, Injury or Disease - by prevention or rapid diagnosis and treatment.

- Freedom to Express Normal Behaviour - by providing sufficient space, proper facilities and company of the animal's own kind.

- Freedom from Fear and Distress - by ensuring conditions and treatment which avoid mental suffering.

There’s broad agreement among animal professionals and the general public that people should treat their animals humanely, but the devil is in the details and debate over how to accomplish that goal rages on. Despite the ability of intensive confinement systems and institutional settings to provide animals with wholesome food and fresh water, and to protect them from predators and extremes in weather, people generally distrust their ability to provide the same level of animal welfare that pastoral life offered in the past. This is the primary animal welfare focus in the US today and it’s one that animal professionals spend considerable resources working to address.

Regardless of the level of care provided and the actual level of wellbeing experienced by the animals, close-confinement housing systems and institutional settings appear unnatural to many onlookers: laboratories where animal studies are conducted; zoos, circuses and marine animal parks where exotic animals can be seen; large farms where thousands of animals may live in close confinement and commercial dog breeding kennels. Even as these businesses explore new approaches and adopt new and improved practices, however, the optics makes it difficult for critics to believe that animal welfare is being nurtured.

Public concern over substandard care and treatment of animals in large-scale or institutional settings has led to an enormous body of federal, state and local laws governing the treatment and housing of animals in these settings, sometimes creating numerous layers of regulations and requiring multiple agencies to perform inspections of the same entity. At the federal level there are laws governing the care of zoo, circus and marine animals ; the humane slaughter of farm animals , how laboratory animals should be treated, and how dogs raised in commercial dog breeding kennels should be housed and cared for. In addition, there are countless local ordinances regulating the keeping of animals, laws that regulate dog breeding and a host of other activities that formerly were conducted in more rural settings.

The role of animal welfare in dealing with animal abuse, cruelty and neglect

Animal abuse comes in many forms, but for purposes of simplification, can be separated into two major categories: abuse that occurs as a result of negligence (failure to act properly) or harm that results from deliberate acts. The lines are sometimes blurred between what is intentional and what is not, and cases are decided on the basis of case-specific facts. Every state now has felony laws against animal cruelty, but they vary tremendously from state to state in the acts they designate as felonies, and in the punishment they impose for those crimes.

In the case of neglect, abuse can be the result of ignorance, such as when a pet owner didn’t recognize that a pet needed veterinary treatment; or when it is the result of behavior that a person should have known would cause harm to animals but allowed to continue.

Abuse can also be the result of overt cruelty to animals . Deliberate acts of cruelty include torture, beating or maiming animals as well as activities such as dog fighting, which result in severe pain, injury and death to the animals involved. Deliberate acts of abuse warrant the most severe penalties, not only because of their shocking nature and the immediate harm they inflict, but also because there are well known connections between abuse to animals and violence against people .

Animal Welfare and Animal Rights ARE NOT THE SAME

Many animal welfare proponents call themselves animal rights advocates because that term seems to represent what they believe, but animal welfare and animal rights are based in entirely different beliefs and use different tactics to achieve their goals. Unlike animal welfare principles, which inherently support the humane and responsible use of animals, animal rights tenets oppose all use of animals no matter how humane, or how responsible. PETA’s motto articulates the animal rights position very well, and demonstrates that in this belief system, animal use and animal abuse are synonymous: “Animals are not ours to eat, wear, experiment on, use for entertainment, or abuse in any other way.”

Animal rights campaigns use animal welfare issues to promote their agenda

Although packaged for maximum appeal, animal rights beliefs conflict with the views of at least 94% of Americans , the number who eat meat. And an additional portion, omnivores and vegetarians alike, benefit from medical advances, go to circuses and zoos, keep pets, hunt or fish, ride horses or otherwise use animals. Americans are generally unaware of the true animal rights agenda . And that makes sense: Although animal rights leaders state their positions clearly when speaking to their followers , many of them hide their true beliefs under a mantle of animal welfare rhetoric when speaking to the public, misleading their audiences about their true agenda. Animal rights campaigns frequently use strategic deceptions against animal owners and businesses. Many people who view themselves as animal rights advocates are simply people who love animals and want to do something to improve their lives. They are unaware of radical path charted by the animal rights leadership.

For the animal rights movement, the ends justify the means

It is also important to recognize that the animal rights movement is the only social movement in the US with a history of working with underground criminals , which the FBI has named single issue terrorists . Notably, many in the animal rights leadership do not condemn violence when it is committed in the name of their cause, a hallmark of unethical and radical movements. Many animal rights groups do little more than exploit animal welfare problems for their own fundraising purposes. Sometimes the fundraising campaign amounts to no more than raising concerns about an industry or pastime that utilizes animals, labeling them as cruel in order to position themselves on the high moral ground and raise money. The ASPCA and HSUS recently paid $9.3 million and $15.75 million respectively to the company that owns Ringling Bros circus to settle, among other things, a Racketeering Corrupt Organization Act (RICO) lawsuit in which they were defendants because they (or their affiliates) improperly paid someone to be a witness against the company with testimony that was not found to be credible.

Another area of disagreement between animal welfare and animal rights proponents is over the legal status of animals. Animal welfare advocates call for animal protection laws. Animal rights supporters push for legal rights for animals, something that requires a change in the legal status of animals and mandates a new class of government administrators to make decisions on behalf of animals. Fundamentally, the animal rights approach to animals is less about improving their care than it is about politics. It’s about power. Specifically it’s about who decides how animals will be treated including whether they should remain in private ownership at all, or be placed in sanctuaries created to provide animals refuge from human ownership and use. Animal rights ideology works to separate people from animals and if achieved would sever the human-animal bond.

The ethical framework that supports animal welfare principles springs from the Western ethical tradition, one that embraces tolerance for diversity and minority views and uses knowledge and education rather than coercion to advance its objectives. The willingness of the animal rights leadership to misrepresent their beliefs and motives and to work with illegal factions indicates that their views arise from different roots.

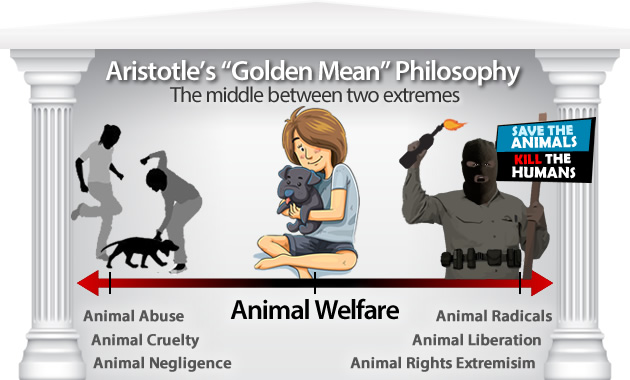

Animal Welfare - The middle ground between two extremes

Aristotle's Golden Mean

The great philosopher Aristotle espoused an ideal he termed the " golden mean " the desirable middle between two extremes, one of excess and the other of deficiency. His ethical framework is outlined in this chart . Though sometimes difficult to achieve, these are the principles that mainstream animal welfare organizations like the National Animal Interest Alliance strive to achieve, making steady progress without compromising other important values like honesty, integrity, lawful conduct and love for our fellow man. Here is an explanatory poster which provides an Overview of Animal Related Philosophies & Organizations that may enable you to visualize the interplay between these concepts and competing values.

The NAIA: Promoting Animal Welfare

The National Animal Interest Alliance is a moderate, mainstream animal welfare organization. To learn more about us, please read the NAIA Values Statement here and visit us at http://www.naiaonline.org

About The Author

Related Articles

National Animal Interest Alliance PO Box 66579 Portland, Oregon 97290-6579 Phone:(503)761-8962 (503)227-8450 Email: [email protected]

About Us Board Members Mission Statement Postion Statement Privacy Policy Our Logos Sitemap -->

Issues and Programs NAIA Campaigns NAIA Shelter Project NAIA Advocacy Center NAIA Rescue Press Center -->

NAIA Library NAIA Articles White Papers Press Releases Guest Editorial and Commentary Heroes, Winners and Sucess Stories

Get Involved & Resources Events Calender Volunteer Legislative & Legal Resources Sites of Interest

Find anything you save across the site in your account

What Would It Mean to Treat Animals Fairly?

By Elizabeth Barber

A few years ago, activists walked into a factory farm in Utah and walked out with two piglets. State prosecutors argued that this was a crime. That they were correct was obvious: The pigs were the property of Smithfield Foods, the largest pork producer in the country. The defendants had videoed themselves committing the crime; the F.B.I. later found the piglets in Colorado, in an animal sanctuary.

The activists said they had completed a “rescue,” but Smithfield had good reason to claim it hadn’t treated the pigs illegally. Unlike domestic favorites like dogs, which are protected from being eaten, Utah’s pigs are legally classified as “livestock”; they’re future products, and Smithfield could treat them accordingly. Namely, it could slaughter the pigs, but it could also treat a pig’s life—and its temporary desire for food, space, and medical help—as an inconvenience, to be handled in whatever conditions were deemed sufficient.

In their video, the activists surveyed those conditions . At the facility—a concentrated animal-feeding operation, or CAFO —pregnant pigs were confined to gestation crates, metal enclosures so small that the sows could barely lie down. (Smithfield had promised to stop using these crates, but evidently had not.) Other pigs were in farrowing crates, where they had enough room to lie down but not enough to turn their bodies around. When the activists approached one sow, they found dead piglets rotting beneath her. Nearby, they found two injured piglets, whom they decided to take. One couldn’t walk because of a foot infection; the other’s face was covered in blood. According to Smithfield, which denied mistreating animals, the piglets were each worth about forty-two dollars, but both had diarrhea and other signs of illness. This meant they were unlikely to survive, and that their bodies would be discarded, just as millions of farm animals are discarded each year.

During the trial, the activists reiterated that, yes, they entered Smithfield’s property and, yes, they took the pigs. And then, last October, the jury found them not guilty. In a column for the Times , one of the activists—Wayne Hsiung, the co-founder of Direct Action Everywhere—described talking to one of the jurors, who said that it was hard to convict the activists of theft, given that the sick piglets had no value for Smithfield. But another factor was the activists’ appeal to conscience. In his closing statement, Hsiung, a lawyer who represented himself, argued that an acquittal would model a new, more compassionate world. He had broken the law, yes—but the law, the jury seemed to agree, might be wrong.

A lot has changed in our relationship with animals since 1975, when the philosopher Peter Singer wrote “ Animal Liberation ,” the book that sparked the animal-rights movement. Gestation crates, like the ones in Utah, are restricted in the European Union, and California prohibits companies that use them from selling in stores, a case that the pork industry fought all the way to the Supreme Court—and lost. In a 2019 Johns Hopkins survey, more than forty per cent of respondents wanted to ban new CAFO s. In Iowa, which is the No. 1 pork-producing state, my local grocery store has a full Vegan section. “Vegan” is also a shopping filter on Sephora, and most of the cool-girl brands are vegan, anyway. Wearing fur is embarrassing.

And yet Singer’s latest book, “ Animal Liberation Now ,” a rewrite of his 1975 classic, is less a celebratory volume than a tragic one—tragic because it is very similar to the original in refrain, which is that, big-picture-wise, the state of animal life is terrible. “The core argument I was putting forward,” Singer writes, “seemed so irrefutable, so undeniably right, that I thought everyone who read it would surely be convinced by it.” Apparently not. By some estimates, scientists in the U.S. currently use roughly fifteen million animals for research, including mice, rats, cats, dogs, birds, and nonhuman primates. As in the seventies, much of this research tries to model psychological ailments, despite scientists’ having written for decades that more research is needed to figure out whether animals—and which kind of animals—provide a useful analogue for mental illness in humans. When Singer was first writing, a leading researcher created psychopathic monkeys by raising them in isolation, impregnating them with what he called a “rape rack,” and studying how the mothers bashed their infants’ heads into the ground. In 2019, researchers were still putting animals through “prolonged stress”—trapping them in deep water, restraining them for long periods while subjecting them to the odor of a predator—to see if their subsequent behavior evidenced P.T.S.D. (They wrote that more research was needed.) Meanwhile, factory farms, which were newish in 1975, have swept the globe. Just four per cent of Americans are vegetarian, and each year about eighty-three billion animals are killed for food.

It’s for these animals, Singer writes, “and for all the others who will, unless there is a sudden and radical change, suffer and die,” that he writes this new edition. But Singer’s hopes are by now tempered. One obvious problem is that, in the past fifty years, the legal standing of animals has barely changed. The Utah case was unusual not just because of the verdict but because referendums on farm-animal welfare seldom occur at all. In many states, lawmakers, often pressured by agribusiness, have tried to make it a serious crime to enter a factory farm’s property. The activists in Utah hoped they could win converts at trial; they gambled correctly, but, had they been wrong, they could have gone to prison. As in 1975, it remains impossible to simply petition the justice system to notice that pigs are suffering. All animals are property, and property can’t take its owner to court.

Philosophers have debated the standing of animals for centuries. Pythagoras supposedly didn’t eat them, perhaps because he believed they had souls. Their demotion to “things” owes partly to thinkers like Aristotle, who called animals “brute beasts” who exist “for the sake of man,” and to Christianity, which, like Stoicism before it, awarded unique dignity to humans. We had souls; animals did not. Since then, various secular thinkers have given this idea a new name—“inherent value,” “intrinsic dignity”—in order to explain why it is O.K. to eat a pig but not a baby. For Singer, these phrases are a “last resort,” a way to clumsily distinguish humans from nonhuman animals. Some argue that our ability to tell right from wrong, or to perceive ourselves, sets us apart—but not all humans can do these things, and some animals seem to do them better. Good law doesn’t withhold justice from humans who are elderly or infirm, or those who are cognitively disabled. As a utilitarian, Singer cites the founder of that tradition, the eighteenth-century philosopher Jeremy Bentham, who argued that justice and equality have nothing to do with a creature’s ability to reason, or with any of its abilities at all, but with the fact that it can suffer. Most animals suffer. Why, then, do we not give them moral consideration?

Singer’s answer is “speciesism,” or “bias in favor of the interests of members of one’s own species.” Like racism and sexism, speciesism denies equal consideration in order to maintain a status quo that is convenient for the oppressors. As Lawrence Wright has written in this magazine , courts, when considering the confinement of elephants and chimpanzees, have conceded that such animals evince many of the qualities that give humans legal standing, but have declined to follow through on the implications of this fact. The reason for that is obvious. If animals deserved the same consideration as humans, then we would find ourselves in a world in which billions of persons were living awful, almost unimaginably horrible lives. In which case, we might have to do something about it.

Equal consideration does not mean equal treatment. As a utilitarian, Singer’s aim is to minimize the suffering in the world and maximize the pleasure in it, a principle that invites, and often demands, choices. This is why Singer does not object to killing mosquitos (if done quickly), or to using animals for scientific research that would dramatically relieve suffering, or to eating meat if doing so would save your life. What he would not agree with, though, is making those choices on the basis of perceived intelligence or emotion. In a decision about whether to eat chicken or pork, it is not better to choose chicken simply because pigs seem smarter. The fleeting pleasure of eating any chicken is trounced by its suffering in industrial farms, where it was likely force-fed, electrocuted, and perhaps even boiled alive.

Still, Singer’s emphasis on suffering is cause for concern to Martha Nussbaum , whose new book, “ Justice for Animals ,” is an attempt to settle on the ideal philosophical template for animal rights. Whereas Singer’s argument is emphatically emotion-free—empathy, in his view, is not just immaterial but often actively misleading—Nussbaum is interested in emotions, or at least in animals’ inner lives and desires. She considers several theories of animal rights, including Singer’s, before arguing that we should adopt her “capabilities approach,” which builds on a framework developed by the Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen, and holds that all creatures should be given the “opportunity to flourish.” For decades, Nussbaum has adjusted her list of what this entails for humans, which includes “being able to live to the end of a human life of normal length,” “being able to have attachments to things and people outside ourselves,” and having “bodily integrity”—namely, freedom from violence and “choice in matters of reproduction.” In “Justice for Animals,” she outlines some conditions for nonhuman flourishing: a natural life span, social relationships, freedom of movement, bodily integrity, and play and stimulation. Eventually, she writes, we would have a refined list for each species, so that we could insure flourishing “in the form of life characteristic to the creature.”

In imagining this better world, Nussbaum is guided by three emotions: wonder, anger, and compassion. She wants us to look anew at animals such as chickens or pigs, which don’t flatter us, as gorillas might, with their resemblance to us. What pigs do, and like to do, is root around in the dirt; lacquer themselves in mud to keep cool; build comfy nests in which to shelter their babies; and communicate with one another in social groups. They also seek out belly rubs from human caregivers. In a just world, Nussbaum writes, we would wonder at a pig’s mysterious life, show compassion for her desire to exist on her own terms, and get angry when corporations get in her way.

Some of Nussbaum’s positions are more actionable, policy-wise, than others. For example, she supports legal standing for animals, which raises an obvious question: How would a pig articulate her desires to a lawyer? Nussbaum notes that a solution already exists in fiduciary law: in the event that a person, like a toddler or disabled adult, cannot communicate their decisions or make sound ones, a representative is appointed to understand that person’s interests and advocate for them. Just as organizations exist to help certain people advance their interests, organizations could represent categories of animals. In Nussbaum’s future world, such a group could take Smithfield Foods to court.

Perhaps Nussbaum’s boldest position is that wild animals should also be represented by fiduciaries, and indeed be assured, by humans, the same flourishing as any other creature. If this seems like an overreach, a quixotic attempt to control a world that is better off without our meddling, Nussbaum says, first, to be realistic: there is no such thing as a truly wild animal, given the extent of human influence on Earth. (If a whale is found dead with a brick of plastic in its stomach, how “wild” was it?) Second, in Nussbaum’s view, if nature is thoughtless—and Nussbaum thinks it is—then perhaps what happens in “the wild” is not always for the best. No injustice can be ignored. If we aspire to a world in which no sentient creature can harm another’s “bodily integrity,” or impede one from exploring and fulfilling one’s capabilities, then it is not “the destiny of antelopes to be torn apart by predators.”

Here, Nussbaum’s world is getting harder to imagine. Animal-rights writing tends to elide the issue of wild-animal suffering for obvious reasons—namely, the scarcity of solutions. Singer covers the issue only briefly, and mostly to say that it’s worth researching the merit of different interventions, such as vaccination campaigns. Nussbaum, for her part, is unclear about how we would protect wild antelopes without impeding the flourishing of their predators—or without impeding the flourishing of antelopes, by increasing their numbers and not their resources. In 2006, when she previously discussed the subject, she acknowledged that perhaps “part of what it is to flourish, for a creature, is to settle certain very important matters on its own.” In her new book, she has not entirely discarded that perspective: intervention, she writes, could result in “disaster on a large scale.” But the point is to “press this question all the time,” and to ask whether our hands-off approach is less noble than it is self-justifying—a way of protecting ourselves from following our ideals to their natural, messy, inconvenient ends.

The enduring challenge for any activist is both to dream of almost-unimaginable justice and to make the case to nonbelievers that your dreams are practical. The problem is particularly acute in animal-rights activism. Ending wild-animal suffering is laughably hard (our efforts at ending human suffering don’t exactly recommend us to the task); obviously, so is changing the landscape of factory farms, or Singer wouldn’t be reissuing his book. In 2014, the British sociologist Richard Twine suggested that the vegan isn’t unlike the feminist of yore, in that both come across as killjoys whose “resistance against routinized norms of commodification and violence” repels those who prefer the comforts of the status quo. Wayne Hsiung, the Direct Action Everywhere activist, was only recently released from jail, after being sentenced for duck and chicken rescues in California. On his blog, he wrote that one reason the prosecution succeeded was that, unlike in Utah, he and his colleagues were cast as “weird extremists.”

It’s easy to construct a straw-man vegan, one oblivious to his own stridency, privilege, or hypocrisy. Isn’t he driving deforestation with all his vegetables? (No, Singer replies, as the vast majority of soybeans are fed to farm animals.) Isn’t he ignoring food deserts or the price tag on vegan substitutes, which puts them out of the reach of poor families? (Nussbaum acknowledges that cost can be an issue, but argues that it only emphasizes the need for resourced people to eat as humanely as they can, given that the costs of a more ethical diet “will not come down until it is chosen by many.”) Anyone pointing out moral culpability will provoke, in both others and themselves, a certain defensiveness. Nussbaum spends a lot of time discussing her uneasiness with her choice to eat fish for nutritional reasons. (She argues that fish likely have no sense of the future, a claim that even she seems unsure about.) Singer is eager to intervene here, emphasizing that animal-rights activism should pursue the diminishment of suffering, not the achievement of sainthood. “We are more likely to persuade others to share our attitude if we temper our ideals with common sense than if we strive for the kind of purity that is more appropriate to a religious dietary law than to an ethical and political movement,” he writes. Veganism is a boycott, and, while boycotts are more effective the more you commit to them, what makes them truly effective is persuading others to join them.

Strangely, where Singer and Nussbaum might agree is that defining the proper basis for the rights of animals is less important, at least in the short term, than getting people not to harm them, for any reason at all. Those reasons might have nothing to do with the animals themselves. Perhaps you decide not to eat animals because you care about people: because you care that the water where you live, if it’s anything like where I live, is too full of CAFO by-products to confidently drink. Perhaps you care about the workers in enormous slaughterhouses, where the pay is low and the costs to the laborer high. Perhaps you believe in a God, and believe that this God would expect better of people than to eat animals raised and killed in darkness. Or perhaps someone you love happens to love pigs, or to love the idea that the world could be gentler or more just, and you love the way they see the future enough to help them realize it. Nussbaum, after all, became interested in animal rights because she loved a person, her late daughter, an attorney who championed legislation to protect whales and other wild animals until her death, in 2019. Nussbaum’s book is dedicated to her—and also, now, to the whales. ♦

New Yorker Favorites

Searching for the cause of a catastrophic plane crash .

The man who spent forty-two years at the Beverly Hills Hotel pool .

Gloria Steinem’s life on the feminist frontier .

Where the Amish go on vacation .

How Colonel Sanders built his Kentucky-fried fortune .

What does procrastination tell us about ourselves ?

Fiction by Patricia Highsmith: “The Trouble with Mrs. Blynn, the Trouble with the World”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Jay Caspian Kang

By Jessica Winter

By Amy Davidson Sorkin

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

119 Animal Welfare Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Title: 119 Animal Welfare Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Introduction: Animal welfare is an important issue that encompasses the well-being of animals, their treatment, and the ethical considerations surrounding their use in various industries. Writing an essay on animal welfare can help raise awareness about the various challenges animals face and the need for better protection and treatment. To assist you in choosing a topic, we have compiled a list of 119 animal welfare essay topic ideas and examples. This comprehensive list covers a wide range of subjects, ensuring that you will find something that resonates with your interests and concerns.

I. Animal Testing and Research:

- The ethical implications of animal testing: Discuss the morality of using animals for scientific research.

- Alternatives to animal testing: Explore the development and effectiveness of alternative methods in scientific research.

- The impact of animal testing on medical advancements: Assess the contribution of animal testing to the progress of medical science.

- Animal testing in cosmetics industry: Evaluate the necessity and ethical implications of animal testing for beauty and personal care products.

- The role of legislation in regulating animal testing: Analyze the effectiveness of laws in ensuring ethical treatment of animals in research.

II. Factory Farming and Animal Agriculture: 6. The environmental impact of factory farming: Discuss the ecological consequences of intensive animal agriculture. 7. Animal welfare in intensive farming: Examine the conditions and treatment of animals on factory farms. 8. The role of antibiotic use in animal agriculture: Explore the effects of antibiotics on animal welfare and public health. 9. The ethics of consuming animal products: Discuss the moral implications of supporting an industry that often neglects animal welfare. 10. The potential of plant-based diets: Evaluate the benefits of plant-based diets for animal welfare, the environment, and human health.

III. Wildlife Conservation and Habitat Preservation: 11. The impact of climate change on wildlife: Examine how climate change affects animal habitats and biodiversity. 12. The role of zoos in wildlife conservation: Assess the effectiveness of zoos in preserving endangered species and educating the public. 13. Trophy hunting and its consequences: Discuss the ethical considerations surrounding trophy hunting and its impact on animal populations. 14. Wildlife trafficking and illegal trade: Analyze the effects of illegal wildlife trading and explore potential solutions. 15. Human-wildlife conflict: Investigate the conflicts that arise when human and animal habitats overlap, and propose strategies for coexistence.

IV. Pets and Companion Animals: 16. The responsibility of pet ownership: Discuss the obligations and ethical considerations of owning a pet. 17. Animal shelters and adoption: Explore the importance of adopting animals from shelters and the challenges faced by these organizations. 18. Animal abuse and neglect: Investigate the causes and consequences of animal abuse and propose preventive measures. 19. The benefits of therapy animals: Examine the positive impact of therapy animals on human well-being. 20. The influence of popular culture on pet trends: Analyze how media and trends affect pet ownership and animal welfare.

Conclusion: Animal welfare is a multifaceted and vital topic that demands attention and action. By choosing a compelling animal welfare essay topic from this comprehensive list, you can contribute to the ongoing discourse surrounding the treatment and protection of animals. Remember to consider your own interests and passions when selecting a topic, as this will ensure that your essay is both engaging and impactful. Whether you choose to explore the ethics of animal testing, the environmental consequences of factory farming, or the challenges faced by wildlife conservation efforts, your contribution to raising awareness about animal welfare is essential.

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

- Open access

- Published: 29 December 2023

Animal welfare research is fascinating, ethical, and useful—but how can it be more rigorous?

- Georgia J. Mason 1

BMC Biology volume 21 , Article number: 302 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2114 Accesses

28 Altmetric

Metrics details

The scientific study of animal welfare supports evidence-based good animal care, its research contributing to guidelines and policies, helping to solve practical problems caused by animal stress, and raising fascinating questions about animal sentience and affective states. However, as for many branches of science (e.g. all those with replicability problems), the research rigour of welfare science could be improved. So, hoping to inspire methodologies with greater internal, external, and construct validity, here I outline 10 relevant papers and provide potential “journal club” discussion topics.

Welfare science now: a thriving field with ethical, practical, and fundamental relevance

As noted by Marian Dawkins, a long-standing leader in this field, animals with good welfare are healthy and have what they want (in terms of, for example, space, shelter, and opportunities to perform highly motivated natural behaviours). This results in them having more positive “affective states”, i.e. moods, emotions, and similar. Identifying such states, and understanding how they could be achieved, is the remit of animal welfare research. Studying animal welfare was somewhat fringe when the field emerged in the 1970s and 1980s: a European eccentricity. But today, animal welfare publications number in the thousands annually; animal welfare conferences involve hundreds of researchers; welfare presentations are not uncommon at agricultural, ecology, animal cognition, and even human emotion meetings; welfare research happens in BRICS and developing nations, not just the developed world; and in many countries, welfare research informs policies on how to treat animals. In parallel, welfare research techniques have become more sophisticated, often inspired by studies of human well-being (e.g. mood-sensitive cognitive changes like “judgment bias”).

The growth of welfare science partly reflects its ethical importance, along with increased acceptance by other branches of biology. It also reflects the rewarding nature of working in this field. Intellectually, welfare research touches on fascinating scientific questions such as the evolutionary functions of emotions and moods and the distribution of sentience. Furthermore, despite some tensions between human interests and animal needs (especially in agriculture), understanding and improving welfare can also help solve some practical problems: reducing behavioural problems in pets, tackling poor reproduction in zoos and conservation breeding centres, and increasing job satisfaction for laboratory animal technicians, to name a few. Welfare science is truly an absorbing, satisfying field to be in.

Welfare science in the future: towards greater rigour and validity

BMC Biology’s twentieth anniversary collection comprises comment articles that provide an overview of different fields and projection of future trends, limited to referencing 10 papers. What to cover in my piece? The promise of new technologies for automated welfare assessment? How human research could reveal the functions of conscious affect? The need for wild animal welfare studies in a time of climate change? So many topics, yet underpinning all is a bedrock need for welfare science to be valid: to say something true and relevant about the animals it aims to understand. Validity is therefore my focus, especially given today’s understanding of the unintended consequences of academia’s “publish or perish” culture. I collate 10 papers and provide discussion topics (Table 1 ) for an imaginary journal club on internal, external, and construct validity. A perfect introduction is a seminar by Hanno Würbel, on the principles of good welfare science ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SXJ1TDEUf3U&t=1666s ). Overall, I hope to provoke enjoyable debate, (perhaps uneasy) self-reflection, and ultimately more transparent, valid research.

Internal validity: are our studies bias-free and replicable?

Preclinical animal research (aiming to understand human disease) has been subject to devastating scrutiny especially around “spectacular cases of irreproducibility” [ 1 ]. Only half — at best — of biomedical studies are replicable, impeding biomedical progress with vast numbers of false leads. Causes include research designs that bias data (e.g. absence of blinding or randomisation), statistical misbehaviours like “P-hacking”, and selective reporting of results [ 1 ]. A survey of 271 biomedical publications thus identified “a number of issues” [ 2 ], randomisation being reported in just 12% for example. Practices like blinding are crucial in welfare research too, as Tuyttens and colleagues [ 3 ] demonstrated. Students, trained to extract data from ethological videos, produced skewed data if given false information about the subjects being scored (cattle believed to be hot being scored as panting more, for instance), leading the authors to lament, “can we believe what we score, if we score what we believe?”.

Adding further concerns, Kilkenny and colleagues found that only 62% of biomedical experiments that were amenable to factorial designs actually used them. Reassuringly, 87% did seem to use appropriate statistical methods [ 2 ]. However, P-hacking is often impossible to detect post-publication. Furthermore, other work (e.g. excellent publications by Stanley Lazic, including [ 4 ]) identifies pseudoreplication as a common statistical error. The Kilkenny paper also reported some lack of clarity in writing, inconsistent with a priori hypothesis testing, with 5% of studies not explaining their aims. (This issue resonated with me; in my lab, we recently screened the introductions of 71 papers on judgement bias and found it impossible to ascertain the research aims of 8 of these [11%]).

External validity: are our studies relevant to real-world situations?

Even when results are internally valid and replicable, they might be irrelevant to other populations or contexts. Thus, biomedical research results often do not translate to humans; and for animal welfare, data collected in a welfare research lab may not translate to commercial situations. Solutions to this could include “introducing systematic variation (heterogenization) of relevant variables (for example species/strains of animals, housing conditions, tests)” [ 1 ]. Dawkins [ 5 ] takes this further, arguing that, at least for poultry, controlled laboratory situations have limited value. “Working directly with the poultry industry on commercial farms … shows what works in practice, out there in the real world”: it is critically important because “what is true of 50 birds in a small pen is not necessarily true of 50,000 birds in a large poultry house”.

Construct validity: do our measures mean what we think they mean?

Welfare researchers have another challenge: making defensible inferences about something that cannot be measured directly — affective states. Doing this well requires knowing our measures have construct validity, and understanding a priori their strengths and weaknesses. Welfare studies thus largely fall into two types: those seeking to validate new indicators of affect (via manipulations known a priori to influence affective state) and those using well-validated indicators to discover new things about animal well-being. Both must be logical and transparent. Thus, validation studies must use defensible validation methods; and if a potential indicator fails, that measure must not be treated as if still valid. Likewise, welfare studies must select well-validated, appropriate indicators, such that increased/decreased values have meanings that are known a priori , not invoked post hoc once results are known.

If we do not work in this logical way, we risk “HARK-ing” (‘Hypothesising After the Results are Known’): a form of circular reasoning where aims and predictions are covertly tweaked after seeing patterns in the data, which looks (indeed is ) biased. Perhaps worse, we may draw mistaken conclusions about animals: ones which fail to improve their well-being. As Rosso et al. [ 6 ] argue in a preprint, “HARKing can invalidate study outcomes and hamper evidence synthesis by inflating effect sizes... lead researchers into blind alleys … and waste animals, time, and resources”.

So, how to ensure an indicator has construct validity? Jake Veasey and I [ 7 ] outlined three methods: (1) assessing whether a potential indicator changes alongside self-reported affect in humans (assuming homology between species), (2) assessing whether it changes in animals deliberately exposed to aversive treatments, and (3) assessing whether such changes can be reversed pharmacologically, by giving, e.g. analgesics or anxiolytics. Another two — as beautifully laid out by philosopher Heather Browning [ 8 ] — are as follows: (4) recording effects of exposing animals to factors important for fitness and (5) identifying correlates of existing, well-validated indicators. And to give one illustration of construct validation done well, Agnethe-Irén Sandem and colleagues investigated eye-white exposure as a potential indicator of negative affect in cattle (e.g. [ 9 ]); see Table 1 for details.

Underneath all these issues lies the problematic incentive structure of academia. As Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet , wrote in 2015, “No-one is incentivised to be right. Instead, scientists are incentivised to be productive”. Obsessions with publication rates and P -values under 0.05 affect animal welfare science just as they do other disciplines. One partial solution could involve “open science” practices [ 10 ], such as pre-registering planned studies (so that hypotheses and statistical analyses are spelled out a priori , and, for registered reports, manuscripts are peer-reviewed and accepted before results are generated) and providing open access to data (so that anyone can re-analyse them). But perhaps more radically, perhaps a more fundamental overhaul is needed: a transition to a slower, better science that could improve researchers’ welfare as well as animals'?

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Würbel H. More than 3Rs: the importance of scientific validity for harm-benefit analysis of animal research. Lab Anim. 2017;46:164–6.

Article Google Scholar

Kilkenny C, Parsons N, Kadyszewski E, Festing MF, Cuthill IC, Fry D, Hutton J, Altman DG. Survey of the quality of experimental design, statistical analysis and reporting of research using animals. PloS One. 2009;4:e7824.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tuyttens FAM, de Graaf S, Heerkens JL, Jacobs L, Nalon E, Ott S, Stadig L, Van Laer E, Ampe B. Observer bias in animal behaviour research: can we believe what we score, if we score what we believe? Anim Behav. 2014;90:273–80.

Lazic SE. The problem of pseudoreplication in neuroscientific studies: is it affecting your analysis? BMC Neurosci. 2010;11:1–17.

Dawkins MS. Commercial scale research and assessment of poultry welfare. Brit Poultry Sci. 2012;53:1–6.

Rosso M, Herrera A, Würbel H, Voelkl B. Evidence for HARKing in mouse behavioural tests of anxiety. bioRxiv. 2022: 2022-12. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.01.518668

Mason GJ, Veasey JS. How should the psychological well-being of zoo elephants be objectively investigated? Zoo Biol. 2010;29:237–55.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Browning, H. Validating indicators of subjective animal welfare. Philos Sci. 2023.1-10. https://doi.org/10.1017/psa.2023.10

Sandem AI, Braastad BO, Bøe KE. Eye white may indicate emotional state on a frustration–contentedness axis in dairy cows. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2002;79:1–10.

Muñoz-Tamayo R, Nielsen BL, Gagaoua M, Gondret F, Krause ET, Morgavi DP, Olsson IA, Pastell M, Taghipoor M, Tedeschi L, Veissier I. Seven steps to enhance open science practices in animal science. PNAS Nexus. 2022;1:106.

Download references

Acknowledgements

With thanks to many colleagues for past discussions (especially Melissa Bateson, Marian Dawkins, Joe Garner, Birte Nielsen, Mike Mendl, Christian Nawroth, Anna Olsson, Liz Paul, Clive Phillips, Jake Veasey, Hanno Würbel, and the members of the Campbell Centre for the Study of Animal Welfare); to Olga Burenkova, Shay Forget, Lindsey Kitchenham, Aileen Maclellan and Alex Podturkin for comments on this paper; and to the many graduate students who took my “Assessing affective states” class (2010–2020). I apologise for relevant studies not mentioned here due to the tight word and reference count restrictions. This work was conducted on the traditional territories of the Mississaugas of the Credit.

The Mason Lab is funded by NSERC.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Campbell Centre for the Study of Animal Welfare/Integrative Biology Department, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, N1G 2W1, Canada

Georgia J. Mason

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

GJM wrote the article and read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Georgia J. Mason .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mason, G.J. Animal welfare research is fascinating, ethical, and useful—but how can it be more rigorous?. BMC Biol 21 , 302 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-023-01793-x

Download citation

Received : 01 December 2023

Accepted : 01 December 2023

Published : 29 December 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-023-01793-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

BMC Biology

ISSN: 1741-7007

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Encyclopedia of Food and Agricultural Ethics pp 148–159 Cite as

Animal Welfare: A Critical Examination of the Concept

- John Rossi 3 &

- Samual Garner 4

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 21 November 2014

479 Accesses

Animal ethics; Animal welfare science; Animal well-being; Prudential value theory

Introduction

The past half-century has witnessed a dramatic increase in both philosophical and social concern about animals. Much of this concern is about animals’ moral standing and the ethical permissibility of various animal-harming practices. However, a parallel track of concern relates to animal mind and animal well-being. Some of the motivation for concern about animal mind and animal well-being can be traced to scientific curiosity; however, the investigation of what animals are like, and what makes an animal’s life go well or poorly, is an important part of moral philosophy. Normative judgments about what humans owe animals usually presuppose some account of what is beneficial or harmful to them, and philosophical work in normative ethics therefore must proceed apace with conceptual and empirical work regarding animal welfare. In addition, an important historical and sociological aspect...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). (2003). Veterinary leaders support science-based OIE animal welfare policies. AVMA News . December 1, 2003. Available at: https://www.avma.org/News/JAVMANews/Pages/031201n.aspx . Last accessed on October 2, 2012.

American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). (2005). A comprehensive review of housing for pregnant sows. JAVMA, 227 (10), 1580–1590.

Google Scholar

Carbone, L. (2004). What animals want: Expertise and advocacy in laboratory animal welfare policy . New York: Oxford University Press.

DeGrazia, D. (1996). Taking animals seriously: Mental life and moral status . New York: Cambridge University Press.

DeGrazia, D. (2007). The harm of death, time-relative interests, and abortion. The Philosophical Forum 38 (1), 57–80.

Fraser, D. (1995). Science, values and animal welfare. Animal Welfare, 4 , 103–117.

Fraser, D. (1999). Animal ethics and animal welfare science: Bridging the two cultures. Applied Animal Behavior Science, 65 , 171–189.

Fraser, D., Weary, D. M., Pajor, E. A., & Milligan, B. N. (1997). A scientific conception of animal welfare that reflects ethical concerns. Animal Welfare, 6 , 187–205.

Harman, E. (2011). The moral significance of animal pain and animal death. In Beauchamp, T.L., & Frey, R.G. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Animal Ethics (pp. 726–737). New York: Oxford University Press

Haynes, R. P. (2011). Competing conceptions of animal welfare and their ethical implications for the treatment of non-human animals. Acta Biotheoretica, 59 , 105–120.

Heathwood, C. (2006). Desire satisfactionism and hedonism. Philosophical Studies, 128 , 539–563.

Humane Society of the United States (HSUS). (2009). Scientists and experts on Gestation Crates and Sow welfare. Humane Society of the United States . October 23, 2009. Available at http://www.hsus.org . Last accessed October 2, 2012.

Jones, W.T. (1975). Logical positivism. In A history of western philosophy, Vol. V, The twentieth century to Wittgenstein and Sartre (2nd ed., revised, pp. 218–249). New York: Harcourt Brace.

Korte, S. M., Olivier, B., & Koolhaas, J. M. (2007). A new animal welfare concept based on allostasis. Physiology and Behavior, 92 , 422–428.

Mason, G., & Mendl, M. (1993). Why is there no simple way of measuring animal welfare? Animal Welfare, 2 , 301–319.

McGlone, J. (2006). Comparison of sow welfare in the Swedish deep-bedded system and the US crated-sow system. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 229 (9), 1377–1380.

Mench, J. (1998). Thirty years after Brambell: Whither animal welfare science? Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 1 (2), 91–102.

Rachels, J. (1993). Subjectivism. In P. Singer (Ed.), A companion to ethics (pp. 432–441). Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Rollin, B. (1990). The unheeded cry: Animal consciousness, animal pain, and science . New York: Oxford University Press.

Rudner, R. (1998). The scientist qua scientist makes value judgments. In E. D. Klemke, R. Hollinger, & D. W. Rudge (Eds.), Introductory readings in the philosophy of science (3rd ed.). Amherst: Prometheus Books.

Smith, Michael, Lewis, David, and Johnston, Mark. (1989). Dispositional theories of value. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Supplementary Volumes, 63: 89-111,113-137,139-174

Shrader-Frechette, K. S. (1991). Risk and rationality: Philosophical foundations for populist reforms . Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Tannenbaum, J. (1995). Veterinary ethics: Animal welfare, client relations, competition and collegiality (2nd ed.). St Louis: Mosby.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Community Health and Prevention, Drexel University School of Public Health, 1505 Race Street, Bellet Building, 11th Floor, 19102, Philadelphia, PA, USA

HJF-DAIDS, a Division of the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., NIAID, NIH, DHHS, 6700A Rockledge Drive Suite 200, 20817, Bethesda, MD, USA

Samual Garner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to John Rossi .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Philosophy, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA

Paul B. Thompson

Department of Philosophy and Religion, University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA

David M. Kaplan

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Rossi, J., Garner, S. (2014). Animal Welfare: A Critical Examination of the Concept. In: Thompson, P.B., Kaplan, D.M. (eds) Encyclopedia of Food and Agricultural Ethics. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0929-4_313

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0929-4_313

Published : 21 November 2014

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-94-007-0928-7

Online ISBN : 978-94-007-0929-4

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Rights of Nature, Rights of Animals

- Kristen Stilt

- See full issue

The fields of animal law and environmental law have an uneasy relationship. At a basic level, they are intertwined by the fundamental observation that animals, human and nonhuman, exist in the environment. Environmental law is generally concerned with animals at the level of species (and specifically endangered or threatened species), whereas animal law is concerned with all animals, regardless of particular characteristics. The issue of wild horses in the western United States illustrates this tension. Some environmentalists view the horses as “feral pests” that damage the fragile ecosystem and compete with wildlife — and privately owned cattle — for resources. 1 They argue that the horses should be gathered through helicopter-led “roundups” and euthanized or sold. 2 Animal protection advocates argue that these roundups are cruel and note that the millions of cattle also grazing on these lands are far more damaging to the environment than the horses. 3 They insist that these wild horses should not be killed — the life of each individual animal matters and should be protected. 4

Environmental law is the older and more established field of law. There are many ways to measure this, such as at the constitutional level, which shows environmental law’s seniority and success. Most constitutions address the environment, and the typical phrasing is anthropocentric: a human right to a healthy environment as seen, for example, in article 42 of the Constitution of Kenya: “Every person has the right to a clean and healthy environment . . . .” 5 Newer trends adopt ecocentric or biocentric approaches and grant rights to nature (or its component parts, such as a river) at the constitutional or legislative level or through judicial decisions. 6