Beyond ‘economic nationalism’: towards a new research agenda for the study of nationalism in political economy

- Original Article

- Published: 23 June 2021

- Volume 25 , pages 235–259, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Thomas Fetzer 1

729 Accesses

3 Citations

9 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Economic nationalism is traditionally seen as the protectionist anti-thesis of economic globalisation. Recent revisionist scholarship has exposed the flaws of this traditional approach but has not been able to challenge the latter’s dominance in the field. The article argues that the root cause of these problems lies in the narrow international political economy focus of the economic nationalism concept, and it advocates replacing the concept with a broader framework for the study of nationalism in political economy. Systematically drawing on nationalism studies, the article first discusses the most commonly adopted approach to nationalism as an ideological programme. Different versions of this approach are mapped, and particular emphasis is placed on the need to pay closer attention to the hitherto neglected domestic community aspect. In a second step, three other, less explored approaches are introduced, namely nationalism as political movement, as political discourse, and as everyday sentiment. These approaches are conceptually demarcated from an ideology-focused paradigm, and their relevance and research potential for political economists are highlighted. While diluting the classic focus on international economic order, the framework embeds scholarship on the nationalism-economy nexus in a broader field of studies at the intersection between constructivist political economy and nationalism studies.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

What Is Globalisation?

Contemporary Issues in Public Policy

A review of location, politics, and the multinational corporation: Bringing political geography into international business

Iiris Saittakari, Tiina Ritvala, … Sjoerd Beugelsdijk

Pickel’s ( 2003 , 2005 ) attempt to provide such a framework remained too generic, not least because it was too little grounded in nationalism studies scholarship. I will elaborate on this further in the next section.

The framework also lacks analytical clarity in its conceptual relationship between ‘discourse’, and ‘ideology/doctrine’ – on the one hand, Pickel emphasises ‘ideology/doctrine’ as a distinct analytical pathway, but, on the other hand, he argues that nationalism ‘should be understood primarily as a generic discursive structure, rather than a substantive doctrine’ (Pickel 2003 : 115).

In the case of cultural nationalism, the argument for a separate concept is made on the grounds that it focuses on moral community building rather than the political demand for territorial self-governance (see Woods 2016 ).

This understanding differs from a historically influential pejorative notion of ideology as ‘false consciousness’, as well as from poststructuralist approaches, which conceptualise ideologies holistically as truth regimes underlying taken-for-granted notions of ‘common sense’ (see Norval 2012).

I do not suggest that nationalist political discourse should be dismissed as ‘cheap talk’ – indeed, its significance will be explored in more detail in a separate section. It is crucial, however, to analytically demarcate this discourse approach from an understanding of nationalism as a purpose-driven ideological programme.

So far, few economic nationalism scholars have adopted a comparative frame of analysis (Abdelal 2001 ; Woo-Cumings 1999 ; D’Costa 2012 ), and these comparisons are usually grounded in region-specific contextual patterns, rather than systematically related to established comparative frameworks in either political economy or nationalism studies.

Breuilly ( 1993 : 9) additionally includes ‘unification’ movements as a separate third type. Such movements are left out of consideration here.

Abdelal, Rawi (2001) National Purpose in the World Economy: Post-Soviet States in Comparative Perspective , Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Google Scholar

Abdelal, Rawi et al. (2010) Constructing the International Economy , Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Adria, Marco (2010) Technology and Nationalism , Montreal: McGill.

Ahamed, Liaquat (2011) ‘Currency Wars, Then and Now’, Foreign Affairs 90 (2): 92‒103.

Akhter, Majed (2015) ‘Infrastructure Nation: State Space, Hegemony and Hydraulic Regionalism in Pakistan’, Antipode 47 (4): 849‒70.

Article Google Scholar

Ananth, Sriram (2013) ‘The Politics of the Palestinian BDS Movement’, Socialism and Democracy 27 (3): 129‒43.

Anderson, Benedict (1983) Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism , London: Verso.

Aronczyk, Melissa (2013) Branding the Nation: The Global Business of National Identity , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Baker, David (2006) ‘The Political Economy of Fascism: Myth or Reality?’, New Political Economy 11 (2): 227‒50.

Béland, Daniel and André Lecours (2008) Nationalism and Social Policy: The Politics of Territorial Solidarity , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Berger, Stefan and Angel Smith (1999) Nationalism, labour and ethnicity 1870‒1939 , Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Billig, Michael (1995) Banal Nationalism , London: Sage.

Blyth, Mark (2002) Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bond, Ross et al. (2003) ‘National identity and economic development: reiteration, recapture, reinterpretation and repudiation’, Nations and Nationalism 9 (3): 371‒91.

Boylan, Brandon (2015) ‘In pursuit of independence: The political economy of Catalonia’s secessionist movement’, Nations and Nationalism 21 (4): 761‒85.

Breuilly, John (1993) Nationalism and the State , second edition, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Brubaker, Rogers (2020) ‘Populism and Nationalism’, Nations and Nationalism 26 (1): 44‒66.

Brubaker, Rogers (1996) Nationalism Reframed: Nationhood and the National Question in the New Europe , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buchanan, James and Roger Faith (1987) ‘Secession and the limits of taxation: toward a theory of internal exit’, American Economic Review 77 (5): 1023‒31.

Bungenberg, Mark and Stephan Hobe (2015) Permanent Sovereignty over Natural Resources , Cham: Springer International.

Burnell, Peter (1986) Economic Nationalism in the Third World , Boulder: Westview Press.

Buzan, Barry et al. (1998) Security: A New Framework of Analysis , Boulder/London: Lyenne Renner.

Callaghan, Helen and Paul Lagneau-Ymonet (2012) ‘The Phantom of the Palais Brongniart: “Economic Patriotism” and the Paris Stock Exchange’, European Journal of Public Policy 19 (3): 388‒404.

Campbell, John L. (1998) ‘Institutional analysis and the role of ideas in political economy’, Theory and Society 27 (3): 377‒409.

Chang, Ha-Joon (2002) Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective , London: Anthem Press.

Clift, Ben and Cornelia Woll (2012) ‘Economic Patriotism: Re-Inventing Control over Open Markets’, Journal of European Public Policy 19 (3): 307‒23.

Collier, Paul and Anke Hoeffler (2002) ‘The Political Economy of Secession’, World Bank Development Research Group Paper, Washington.

Conrad, Sebastian. 2010. Work, Max Weber, Confucianism: The Confucian Ethic and the Spirit of Japanese Capitalism, in Jürgen Kocka, ed., Work in a Modern Society: The German Historical Experience in Comparative Perspective , 153‒168, New York/Oxford: Berghahn.

Costa Pinto, Antonio and Federico Finchelstein (2018) Authoritarianism and Corporatism in Europe and Latin America: Crossing Borders , London and New York: Routledge.

Crane, George T. (1998) ‘Economic Nationalism: Bringing the Nation Back In’, Millenium 27 (1): 55‒75.

D’Costa, Anthony (2012) ‘Capitalism and economic nationalism: Asian state activism in the world economy’, in Anthony D’Costa, ed., Globalization and Economic Nationalism in Asia , 1‒32, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

De la Torre, Cruz (2017) ‘Hugo Chavez and the Diffusion of Bolivarianism’, Democratization 24 (7): 1271‒88.

Desai, Radhika (2008) ‘Conclusion: From developmental to cultural nationalisms’, Third World Quarterly 29 (3): 647‒70.

Eichler, Maja. 2005. Explaining Postcommunist Transformations. Economic Nationalism in Ukraine and Russia, in Eric Helleiner and Andres Pickel, eds, Economic Nationalism in a Globalizing World , 69‒87, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Etges, Andreas (2019) ‘Theoretical and historical reflections on economic nationalism in Germany and the United States in the 19 th and early 20 th centuries’, in Stefan Berger and Thomas Fetzer, eds, Nationalism and the Economy: Explorations into a neglected relationship , 87‒98, Budapest: Central European University Press.

Fetzer, Thomas (2012) Paradoxes of Internationalization: British and German trade unions at Ford and General Motors 1967‒2000 , Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Fougner, Tore (2006) ‘Economic nationalism and maritime policy in Norway’, Cooperation and Conflict 41 (2): 177‒201.

Fox, Jon (2007) ‘From national inclusion to economic exclusion: ethnic Hungarian labour migration to Hungary’, Nations and Nationalism 13 (1): 77‒96.

Fox, Jon and Cynthia Miller-Idriss (2008) ‘Everyday nationhood’, Ethnicities 8 (4): 536‒63.

Frank, Dana (1999) Buy American: The Untold Story of Economic Nationalism , Boston: Beacon.

Freeden, Michael (1998) ‘Is Nationalism a Distinct Ideology?’, Political Studies 46 (4): 748‒65.

Garon, Sheldon and Patricia MacIachlan (2006) The Ambivalent Consumer: Questioning Consumption in East Asia and the West , Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Gellner, Ernest (1983) Nations and Nationalism , Oxford: Blackwell.

Goswami, Manu (2004) Producing India: From Colonial Economy to National Space , Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Greenfeld, Liah (2001) The Spirit of Capitalism. Nationalism and Economic Growth , Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hall, Derek (2005) ‘The Continuing Salience of Economic Nationalism in Japan’, in Eric Helleiner and Andres Pickel, eds, Economic Nationalism in a Globalizing World , 118‒38, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Hancké, Bob (2009) Debating Varieties of Capitalism: A Reader , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harmes, Adam (2012) ‘The rise of neoliberal nationalism’, Review of International Political Economy 19 (1): 59‒86.

Hay, Colin. 2006. Constructivist Institutionalism, in Oxford Handbook of Political Institutions , 56‒74, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hay, Colin (1996) ‘Narrating Crisis: The Discursive Construction of the “Winter of Discontent”’, Sociology 30 (2): 253‒77.

Hayek, Friedrich August (1937) Monetary Nationalism and International Stability , London: Longmans.

Heilperin, Michael (1960) Studies in Economic Nationalism , Geneva: Droz.

Helleiner, Eric (1998) ‘National Currencies and National Identities’, American Behavioral Scientist 41 (10): 1409‒36.

Helleiner, Eric (2002) ‘Economic Nationalism as a Challenge to Economic Liberalism? Lessons from the 19 th century’, International Studies Quarterly 46 (3): 307‒29.

Helleiner, Eric (2021) ‘The Diversity of Economic Nationalism’, New Political Economy 26 (2): 229‒38.

Helleiner, Eric and Andres Pickel (2005) Economic Nationalism in a Globalizing World , Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Hobson, John and Leonard Seabrooke (2007) Everyday Politics of the World Economy , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hroch, Miroslav (1985) Social Preconditions of National Revival in Europe , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ivaldi, Gilles and Oscar Mazzoleni (2019) ‘Economic Populism and Producerism: European Right-Wing Parties in Transatlantic Perspective’, Populism 2 (1): 1‒28.

Johnson, Harry G. (1967) Economic Nationalism in Old and New States , Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Johnson, Juliet and Andrew Barnes (2015) ‘Financial nationalism and its international enablers: The Hungarian experience’, Review of International Political Economy 22 (3): 535‒69.

Knott, Eleonor (2015) ‘ Everyday nationalism: a review of the literature’, Studies on National Movements 3 (1): 1‒16.

Kofman, Jan (1997) Economic Nationalism and Development: Central and Eastern Europe between the two World Wars , Boulder: Westview Press.

Kpessa, Michael et al. (2011) ‘Nationalism, development, and social policy: The politics of nation-building in sub-Saharan Africa’, Ethnic and Racial Studies 34 (12): 2115‒33.

Kühschelm, Oliver et al. 2012. Konsum und Nation. Zur Geschichte nationalisierender Inszenierungen in der Produktkommunikation [Consumption and Nation: History of the Use of Nationalizing Product Communication], Bielefeld: transcript.

Larsson, Oscar (2015) ‘Using Post-Structuralism to explore the full impact of ideas on politics‘, Critical Review 27 (2): 174‒97.

Levi-Faur, David (1997) ‘Friedrich List and the Political Economy of the Nation-State’, Review of International Political Economy 4 (1): 154‒78.

Lewis, Karen (1999) ‘Trying to explain Home Bias in Equities and Consumption’, Journal of Economic Literature 37 (2): 571‒608.

Lorenz, Torsten (2006) Cooperatives in Ethnic Conflicts: Eastern Europe in the 19th and early 20th Century , Berlin: Berliner Wissenschaftsverlag.

Margalit, Yotam (2012) ‘Lost in Globalization: International Economic Integration and the Sources of Popular Discontent’, International Studies Quarterly 56 (3): 484‒500.

Mayall, James (1990) Nationalism and International Society , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mehrotra, Ajay K. (2010) ‘The Price of Conflict: War, Taxes, and the Politics of Fiscal Citizenship’, Michigan Law Review 108 (6): 1053‒78.

Mitchell, Timothy (1998) ‘Fixing the economy’, Cultural Studies 12 (1): 82‒101.

Morse, Adair and Sophie Shive (2011) ‘Patriotism in your Portfolio’, Journal of Financial Markets 14 (2): 411‒40.

Myrdal, Gunnar (1960) Beyond the welfare state: economic planning and its international implications , New Haven: Yale University Press.

Mudde, Cas and Rovira Kaltwasser (2017) Populism: A Very short Introduction , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Norval, Aletta (2012) ‘Poststructuralist Conceptions of Ideology’, in Michael Freeden et al., eds, The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies , 155-74, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nyìri, Pal (2001) ‘Expatriating is patriotic? The discourse on “new migrants” in the People’s Republic of China and identity construction among recent migrants from the PRC’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 27 (4): 635‒53.

O’Brien, Robert and Mark Williams (2020) Global Political Economy. Evolution and Dynamics , fifth edition, London: Palgrave.

Oliver, Pamela and Hank Johnston (2000) ‘What a good idea! Ideologies and Frames in Social Movement Research’, Mobilization 4 (1): 37‒54.

Orridge, Andrew (1981) ‘Uneven Development and Nationalism’, Political Studies 29 (1): 1‒15.

Pickel, Andreas (2003) ‘Explaining, and explaining with, economic nationalism’, Nations and Nationalism 9 (1): 105‒27.

Pickel, Andreas (2005) ‘Reconceptualizing economic nationalism in a globalizing world’, in Eric Helleiner and Andres Pickel, eds, Economic Nationalism in a Globalizing World , 1‒20, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Prideaux, Julien (2009) ‘Consuming icons: nationalism and advertising in Australia’, Nations and Nationalism 15 (4): 616‒35.

Pryke, Sam (2012) ‘Economic Nationalism: Theory, History and Prospects’, Global Policy 3 (3): 281‒91.

Pryke, Sam (2017) ‘Explaining Resource Nationalism’, Global Policy 8 (4): 474‒82.

Ptak, Ralf (2009) ‘Neoliberalism in Germany: Revisiting the Foundations of the Social Market Economy’, in Philip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe, eds, The Road from Mount Pelerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective , 98-138, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rodrik, Dani (2018) ‘Populism and the economics of globalization’, Journal of International Business Policy 1 (1‒2): 12‒33.

Schmidt, Vivien (2008) ‘Discursive Institutionalism: The Explanatory Power of Ideas and Discourse’, Annual Review of Political Science 11 : 303–26.

Schmidt, Vivien (2014) ‘Speaking to the Markets or to the People? A Discursive Institutionalist Analysis of the EU’s Sovereign Debt Crisis’, British Journal of Politics and International Relations 16 (1): 188‒209.

Schultz, Helga and Eduard Kubu (2006) History and Culture of Economic Nationalism in East Central Europe , Berlin: Berliner Wissenschaftsverlag.

Schwartzmantel, John (1987) ‘Class and Nation: Problems of Socialist Nationalism’, Political Studies 35 (2): 239‒55.

Seabrooke, Leonard (2012) ‘Homespun capital: economic patriotism and housing finance under stress’, Journal of European Public Policy 19 (3): 358‒72.

Sheppard, Randall (2011) ‘Nationalism, economic crisis and “realistic revolution” in 1980s Mexico’, Nations and Nationalism 17 (3): 500‒19.

Shulman, Stephen (2000) ‘Nationalist Sources of International Economic Integration’, International Studies Quarterly 44 (3): 365‒90.

Smith, Anthony D. (1998) Nationalism and Modernism , London and New York: Routledge.

Smith, Anthony D. (2008) ‘The limits of everyday nationhood’, Ethnicities 8 (4): 563‒73.

Smith, Anthony D. (2010) Nationalism. Theory, Ideology, History , Cambridge: Polity.

Streeck, Wolfgang (2017) ‘The Return of the Repressed’, New Left Review 104 : 5‒18.

Szlajfer, Henryk. 2012. Economic Nationalism and Globalization: Lessons from Latin America and Central Europe , Leiden: Brill.

Szporluk, Roman (1991) Communism and Nationalism: Karl Marx versus Friedrich List , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tomlinson, Jim (2000) Politics of Decline. Understanding Post-war Britain , London and New York: Routledge.

Tonnesson, Stein (2009) ‘The Class Route to Nationhood: China, Vietnam, Norway, Cyprus – and France’, Nations and Nationalism 15 (3): 375‒95.

Tooze, Adam (1998) ‘Imagining National Economies: National and International Economics Statistics 1900‒1950’, in Geoffrey Cubitt, ed., Imagining Nations, 90‒125, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Torgler, Benno (2007) Tax Compliance and Tax Morale. A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis , Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Trentmann, Frank. 2008. Free Trade Nation. Commerce, Consumption, and Civil Society in Modern Britain , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Trivedi, Lisa (2003) ‘Visually Mapping the “Nation”: Swadeshi Politics in Nationalist India, 1920‒1930’, Journal of Asian Studies 62 (1): 11‒41.

Van Dijk, Teun (1998) Ideology: A Multidisciplinary Approach , London: Sage.

Varadarajan, Latha (2006) ‘The Life and Times of Economic Nationalism’, International Studies Review 8 (1): 90‒92.

Verdery, Katherine (1993) ‘Whither nation and nationalism?’, Daedalus 122 (3): 37‒46.

Vincent, Andrew (2012) ‘Nationalism’, in Michael Freeden et al., eds, The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies , 452‒73, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wimmer, Andreas (2008) ‘The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multi-Level Process Theory’, American Journal of Sociology 113 (4): 970‒1022.

Woo-Cumings, Meredith (1999) The Developmental State , Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Woods, Eric T. (2016), ‘Cultural Nationalism’, in David Inglis and Anna-Maria Almila, eds, The SAGE Handbook of Cultural Sociology , 429‒41, London and New York: Sage.

Wong, Cara J. (2012) Boundaries of obligation in American politics: Geographic, national and racial communities , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wright, Matthew and Tim Reeskens (2013) ‘Of What Cloth Are the Ties that Bind? A Multilevel Analysis of the Relation between National Identity and Support for the Welfare State across 29 European Countries’, Journal of European Public Policy 20 (10): 1443‒63.

Zettelmeyer, Jeromin (2019), ‘The Troubling Rise of Economic Nationalism in the European Union’, Washington: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Download references

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Vera Scepanovic, Niels Oellerich, Jasper Simons, and three anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of International Relations, Central European University, Quellenstraße 51, 1100, Wien, Austria

Thomas Fetzer

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Thomas Fetzer .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

No financial interest or benefit has arisen from this research.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Fetzer, T. Beyond ‘economic nationalism’: towards a new research agenda for the study of nationalism in political economy. J Int Relat Dev 25 , 235–259 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41268-021-00227-x

Download citation

Published : 23 June 2021

Issue Date : March 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41268-021-00227-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Economic nationalism

- Everyday political economy

- Nationalist movements

- Political discourse

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Economic Nationalism: Theory, History and Prospects

Related Papers

Yorgos Rizopoulos

In this contribution, the meaning of economic nationalism and the possibilities of pursuing nationalist policies in the context of increasingly interdependent economic processes are discussed. Economic nationalism need not solely be affiliated with statist protectionism, while very few states dispose of the necessary economic, social, political and institutional conditions to influence economic policy given the long-term tendencies that undermine nationalist wills (empowerment of supranational bodies, internationalization of production, deindustrialization). Even these states are not monolithic and the pattern of business/government relations in different fields would have a critical influence. Nationalist-type policies would probably be fragmented, followed in some specific domains under powerful constraints.

Anthony D'Costa

Baltic Journal of Economic Studies

Nataliia Reznikova

The purpose of the paper is to analyse the fundamental principles of the policy of economic nationalism and economic patriotism, its origins, intentions and mechanisms of implementation. The analysis of selected theories allowed for outlining the most essential characteristics, along with identifying the ones laying the fundament for economic nationalism. The main purposes of the policy of economic nationalism and economic patriotism have a similarity: in spite of the common adjective “economic”, they have always gone beyond the boundaries of economic regulation, being a response on “political order” of the time. 21 century offers a lot of evidence to confirm the above thesis. Elements of the economic nationalism in the economic patriotism policy have been demanded by state power officials as a kind of response on the awareness of market failure in striking a new balance in the conditions of the imbalanced global economy, with the growing competition and the shrinking global trade. ...

Gilles Saint-Paul

This chapter provides an in-depth analysis of the phenomenon of economic nationalism, as practiced by many governments in the EU, for example in the form of opposition to cross-border mergers, promotion of national champions and bailing out of domestic firms. Even though such measures usually are very inefficient ways of achieving national objectives, they still have been employed. The chapter

Binh N . Nguyen

Debates and studies among intellectuals about the link between nationalism and economy are often conducted within the scenario of developing economies. However, recent discussions of economic nationalism resurface even within the context of advanced economies, especially after many political movements engaging with nationalist attitude are winning grounds globally. Within that context, the paper aims to identify factors that drives the latest trend of economic nationalism and possible consequences while this trend is slowly taking over today's economic structure that becomes more and more globalized. Regarding motivations behind economic nationalism, the paper introduces two arguments. Firstly, economic nationalism nowadays serves as a tool to rally political supports from growing demographic groups that see no benefit of a globalized economy. Secondly, with a narrow view that global economic cooperation is a zero-sum game, politicians adopt nationalist economic planning in their agenda to once again restore national identities and reestablish a new economic competition among nations. Conflicts with severe consequences are in the horizon should this trend of conservative economic planning continues among big nations. And, perhaps, more importantly, the inward-looking attitude of governments in advance economies will strike a blow to international cooperation efforts to solve more threatening global issues like climate change and growing social inequality.

Gordana Uzelac

It is a 'well-known fact' - at least among economists, political economists, and in public perception - that Economic Liberalism and Economic Nationalism are antitheses. In circles of economic liberals, economic nationalism was a term used to describe 'policies they did not like ' (Helleiner, 2002: 308-9), as 'everything that did not fit in with the liberal definition of economy and development’ (Koffman, 1990). It is generally seen among these as a rise in protectionism, as neo-mercantilism (Pryke, 2012), as an idea that 'economic activities are and should be subordinate to the goals of state building and the interests of the state' (Gilpin, 1987: 31). Seen as such a set of policies, Economic Nationalism is construed as the main obstacle to the true free market economies. This paper rejects those views and follows recent approaches that rightly see economic nationalism as a form of nationalism, not of an economy. Hence, it claims that economic nationalis...

Dr Abdul Azim Islahi

Abstract: Dadabhai Naoroji (1825-1917) was among the leading Indian nationalist leaders who aroused the feeling of economic nationalism and propagated for it. The most instrumental in this regard had been his theory of drain. The paper studies this theory and its role in awakening the desire and movement to achieve economic nationalism. It also examines the stages through, which Dadabhai passed from economic nationalism to political nationalism or the self-rule which was his final call. The paper will conclude with a remark that economic nationalism and political nationalism are complementary and supplementary to each other and none will be realized in true sense of the word without the achievement of other.

Trent International Political Economy Centre

Andreas Pickel

Christopher Pokarier

Nationalism studies have provided us with good understandings of why boundaries matter as concept: their imagining is part of the conceptualization of national group particularity and its host territory. Inquiry is still needed into why national boundaries, in their modern technically complex and often virtual form, are taken seriously in practice. For the formulation and enforcement of such precise borders is costly. Why do valuable national resources get redirected from individual or other collective goods to the often technical and laborious tasks of comprehensive specification of national interests and consequent boundary design and enforcement? What makes some cross-border ‘risks’ politically salient and not others? Who gains? Who loses? The costs of national border regimes fall both upon the state, hence taxpayers, and upon all those private entities subject to the associated compliance and opportunity costs, or to co-option in border enforcement. The ideational fact of nation...

Sociologia & Antropologia

Chris Opesen

RELATED PAPERS

Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English

Konstantinos Chondroudis

Revue internationale d'éducation de Sèvres

Patricia Broadfoot

Proceedings of the ITI 2012 34th International Conference on INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY INTERFACES

Viorel Negru

Batja Mesquita

Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia

Bruno Caramelli

Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition

Isaac Weisfuse

Journal of Medical Science And clinical Research

The Journal of Physical Chemistry C

Tarun Mandal

Open Forum Infectious Diseases

Sumeeta Srinivasan

MIGUEL FERNANDO CASTRO SANCHEZ

CESAR HUMERTO DUARTE ALVARADO

Angelo Mazzu

Acta clinica Croatica

Environmental microbiology

Dirk De Beer

Al-Mukhtar Journal of Sciences

Ismaeel Bozakouk

Arthur Foch

KnE Life Sciences

Fedik abdul Rantam

Marcos N . Beccari

The Journal of Cell Biology

Len Pagliaro

Hippolyte Nyengeri

Sydney Carpenter

Gary A Stilwell

pedro rodriguez gomez

Sayyed Yaghoub Zolfegharifar

See More Documents Like This

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Economic Nationalism

Jason Jackson

Economic nationalism has returned to the fore of scholarly and policy debates. The concept took on renewed significance in the wake of the global financial crisis as countries sought to respond to the domestic effects of the economic disaster. Nationalist responses were initially praised by some who saw them as logical mechanisms to protect domestic economies and condemned by others fearing the shadow of the Great Depression and the rise of fascism that kindled inter-state rivalries and led to World War II. The latter concern has become more prescient in more recent years with the rise of right-wing authoritarian nationalism, in the US, Europe and of course India and Brazil.

Nationalism has long been seen as a central explanatory factor underpinning protectionist economic policies, from the era of late imperialism and mercantilism that marked the end of the ‘first’ globalization, through the post-war era when newly independent states sought to assert control over domestic economies that were previously controlled by colonial powers in the name of development, to the current of period of neoliberal crises. However, while the concept of economic nationalism is frequently deployed it is often underspecified, posited as the cause of protectionism in some cases while providing a rationale for liberalization in others. This research seeks to address issue by providing a more rigorous articulation of this crucial concept.

To do so the project analyzes puzzling contrasts in policy approaches to regulating foreign investment in post-war India and Brazil (1945-1960). Conventional approaches cite India’s leftist ‘socialism’ and Brazil’s right-wing authoritarianism to explain why India generally resisted foreign direct investment (FDI) while Brazil welcomed foreign firms. However, this ignores puzzling industry-level variation: India restricted FDI in manufacturing industry such as automobiles but allowed multinationals to establish dominant positions in natural resource-based sectors like petroleum, while Brazil welcomed foreign companies to establish its nascent automobile industry but strongly prohibited FDI in oil. This variation is inadequately explained by pluralist theories of organizational power, materialist approaches based on these countries’ structural positions in the global economy, or ideational theories resting on the role of economic ideas. Instead, this research argues that policymakers’ preferences were shaped by contrasting colonial experiences that generated distinct nationalist beliefs in the role of foreign capital in industrial development. Indian economic nationalism was rooted in the idea that British free trade policies deindustrialized India by destroying pre-colonial manufacturing skills thus derailing India from its ‘natural’ industrialization course. Nationalist development goals were thus oriented towards regaining lost manufacturing prowess. Brazilians had no such social memory of past manufacturing glory. Instead, nationalist beliefs rested on protecting natural resource wealth. These differences in the content and meaning of development thus combined to generate distinct varieties of economic nationalism and ensuing policies and patterns of industrialization in both countries that persist to this day.

Image credit: The Rise of Economic Nationalism Threatens Global Cooperation. Monica de Bolle. Peterson Institute for International Economics

The Rise of Economic Nationalism Ushers In an Era of Uncertainty

Millions of chinese entered the middle class and free trade reigned supreme. the end of the cold war meant the end of history, then donald trump took center stage.

By Henry Thomson and Michael Hechter

Economic policymaking in developed democracies has become difficult to decipher. Why, after Democrats harshly criticized the Trump administration’s trade tariffs on China, is the Biden administration keeping most of these measures in place and even expanding plans to prevent imports of Chinese steel? Why, after experts’ cries that President Trump was supposedly dismantling the liberal international order, does President Biden continue his hardline stance toward the World Trade Organization and refuse to appoint new members to its appellate body, which mediates international trade disputes?

The explanation for these puzzling phenomena is a new nationalist era of politics and economy policymaking emerging not only in the developed world but globally. Under this new economic nationalism, appeals to national identity increasingly trump those to individual economic self-interest. Liberal orthodoxies predominant since the end of World War II are increasingly disregarded as voters and governments trade off the efficiency of economic globalization against the vision of greater autonomy for their nation-state.

The rise of this nationalism is an important shift in the politics of the world economy. For three decades, globalization has been steered predominantly by liberal ideas that had seen off the Cold War challenge of Marxism. Today, attacks on the open world economy come not only from the left—which has always denounced what it sees as the exploitation of low-income workers in developing countries—but also from those on the right who are supposed to be among the greatest benefactors and supporters of globalization. That is what makes the emerging era of economic nationalism new and surprising to politicians, scholars and commentators who had grown comfortable with a long-standing consensus on the benefits of open international markets.

The Chinese Miracle

When Deng Xiaoping became the leader of the Chinese Communist Party in 1978, China was an overwhelmingly rural country. Only 1 in 5 Chinese lived in cities. Three-quarters of a billion peasants labored in agricultural collectives to meet quotas handed down by state bureaucrats. They produced barely as much food as they had in the early 1950s. After nearly three decades of Maoist rule—including the upheavals of land redistribution, collectivization, the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution—China’s economy was stagnant at best.

By the time of Deng’s ascent, a few plucky local party officials had begun to experiment with ideas questioning the very foundations of China’s socialist economy. But they did so in secret, fearing reprisals from party bosses who had punished reformers in the wake of the Great Leap Forward in the early 1960s. Their experiments—to allow households, rather than collectives, to lease land and fill state production quotas—caused an immediate surge in food production. They were so successful that the party had to take notice.

In 1956, under Mao, the party had collectivized the entire Chinese peasantry in a burst of revolutionary mobilization. Under Deng, it reversed course almost as quickly, if less coercively. Two years after Deng blessed the household responsibility system as “consistent with socialism” in 1982, almost all Chinese peasants were able to plant, harvest and profit free from the strictures of collectivized agriculture.

Choosing Prosperity

The popular faces of neoliberalism are Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, staring down strikes by coal miners, railway workers and air traffic controllers to check labor unions and speed up a trend toward deregulation and lower taxes among Western democracies. But Deng and the reformers in the Chinese Communist Party were the ones who truly epitomized the triumph of neoliberalism: the belief that the path to prosperity runs through markets and trade—even if the party didn’t sign up for the notion of a small state focused on upholding private property rights.

China’s agricultural reforms lifted hundreds of millions of peasants out of poverty and drove a historic economic transformation. By 2001, when China joined the World Trade Organization, millions of private farms and trading entities had replaced the previous central plan for agriculture. Special economic zones open to international trade and investment, such as Shenzhen’s, were fast becoming huge manufacturing hubs. China’s rural population had shrunk by a quarter, and output per capita had increased fivefold.

Bringing markets and prosperity to communist China was the ultimate, if unanticipated, achievement of the neoliberals, who after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the defeat of the Soviet Union appeared to be leading a march toward “the end of history,” as Francis Fukuyama famously put it. A combination of liberal democracy and capitalist enterprise was the apparent end point of the political-economic organization on which humanity was converging. It might take a while, but it seemed that even China would join the club as it extended its trajectory of market reform into the political sphere.

Meanwhile, among democracies, economic globalization was almost universally accepted as key to sustained economic growth. Market skeptics in traditional social democratic parties were elbowed aside as leaders of a center-left “third way” such as Bill Clinton and Tony Blair supported greater economic integration through the North American Free Trade Agreement, the European Union and the WTO.

The End of ‘The End of History’

How jarring, then, when Donald Trump announced his candidacy for president with a fierce attack on free trade and America’s engagement with the Chinese economy. To be fair, his opposition to globalization had been gestating a long time: In the 1980s, Trump complained to Oprah Winfrey on TV that Japan exploited the free trade system to “dump everything right into our markets … knock the hell out of our country.” He told Piers Morgan in 2011 that “China is just ripping us left and right … they’re taking our jobs.” And Trump was far from alone, as illustrated by the presidential campaigns of Pat Buchanan and Ross Perot, the “Battle for Seattle” protests against the 1999 WTO conference, George W. Bush’s steel tariffs and the Occupy Wall Street movement.

But it was one thing for a celebrity real estate developer to hold these economic views; it was quite another for the Republican nominee for president to see trade in such zero-sum terms: “When was the last time anybody saw us beating, let’s say, China in a trade deal? They kill us.”

More disorienting were Trump’s views on immigration, especially illegal immigration. Trump broke completely with the right’s traditional preference for immigration to contain wage growth and lower costs for employers. He descended on Laredo, Texas, in his private jet to tout a U.S.-Mexico border wall and bask in the concentrated attention of an incredulous national press corps.

An Ally in the U.K.

Moreover, Trump was not alone in railing against globalization. He seemed to capture and embody a new zeitgeist in opposition to prevailing economic orthodoxies. As his presidential campaign picked up steam—taking the lead in Republican primary polls in July 2015 and accepting the party’s nomination a year later—the Brexit campaign surged to a surprise victory in the June 2016 referendum in the U.K. Another eccentric outsider and long-standing opponent of European integration, Nigel Farage, was able to bundle people’s opposition to trade and immigration into a majority in favor of “taking back control” from the EU’s supranational governance structures in Brussels.

The zeitgeist that Trump and Farage were both tapping into was a new economic nationalism, a movement appealing to collective national identities rather than the economic self-interest of individuals or companies, with the goal of maximizing the autonomy of the nation rather than economic growth.

To be clear, economic nationalism is nothing new. From Alexander Hamilton and Friedrich List through Hermann Göring to the bureaucrats of Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry, thinkers and policymakers have long defied liberal doctrines of free trade. Their goals have ranged from protecting infant industries to subjugating neighboring states in preparation for war, and they have sometimes been spectacularly achieved.

Economic nationalism has been an ideological current against the tide of liberalism since globalization’s infancy in the 18th century. Nationalists favor cultural politics, and they mobilize cross-class coalitions that blow up the familiar distinction between left and right or the owners of labor and capital. They pursue expansive programs to construct infrastructure such as railway networks and coordinate the development of manufacturing and military industries, and they do so in the name of the nation instead of specific classes, companies or interest groups.

Nationalists Around the World

But the rise of contemporary economic nationalism has come as a surprise. Only 10 years ago, these ideas were confined to the political fringes; now they are mainstream. The new nationalism is also not confined to the U.S. and Britain. In post-communist Eastern Europe, a generation of nationalist leaders has diverged from the neoliberal “big bang” policies of the 1990s.

Exemplified by Victor Orbán in Hungary, they have re-nationalized key industries, embraced state-led workforce activation campaigns, and provided generous new support for the elderly and families with children. In the former East Germany, the nationalist Alternative für Deutschland has won support with its opposition to European integration and immigration since 2013. In China, the high tide of market reform has ebbed under Xi Jinping, with policies such as the Belt and Road Initiative and the doctrine of “dual circulation” aiming to reduce his country’s integration into the global economy.

Economic nationalists might seem to have a lot in common with left-wing opponents of globalization, whose radical demonstrations at meetings of the WTO, G-7 and other pro-trade organizations have been making headlines for decades. Bernie Sanders in the U.S. and Jeremy Corbyn in the U.K. have called for withdrawal from the WTO and the EU and supported the nationalization of industries. But there is an important distinction. Critiques of globalization from the left revolve around class-based grievances: Critiquing unfettered immigration due to fears of lower domestic wages, for example, or opposing trade because lower labor standards in developing countries raise fears of job losses at home. Although the working class might be defined as very large and almost contiguous with the nation—the “99% versus the 1%”—it is still based on economic interests rather than culturally defined national interests.

Five years on from the watershed election of 2016, economic nationalism appears to be here to stay. There are few signs of a return to neoliberal orthodoxies and the pursuit of economic globalization. Class-based politics have ceded center stage to culture-based politics and competing appeals to national identity.

Ready for more?

Would Economic Nationalism Benefit the U.S.?

Economic nationalism can mean different things to different people. However, features that are usually associated with it are concerns about imports and foreign ownership of a nation’s assets. Such concerns may lead to higher barriers to trade and foreign investment. Among other factors, this issue of economic nationalism has gained traction because of rising inequality in recent decades.

According to an October paper, the average pre-tax income of the bottom 50 percent of adults in the U.S. has remained at about $16,000 per adult (in constant 2014 dollars) since 1980. When looking at the entire distribution, however, average national income per adult grew by 60 percent to $64,500 in 2014. 1

Therefore, in spite of relatively low unemployment rates and increasing prosperity of certain segments of the population, some imports that may be destroying U.S. manufacturing jobs are being seen with greater suspicion. In turn, this has given new life to the idea of mercantilism, which favors positive trade balance (that is, the value of exports being greater than the value of imports).

Gaining from Trade

Trade balance does not reflect a nation’s potential for gains from trade. Consider a nation that does not trade and, hence, has a trade balance of zero. When this nation opens up to trade and pays for imports with exports, the trade balance is again zero. However, its welfare is higher because of gains from specialization and trade.

Furthermore, notice that imports and exports are two sides of the same coin. When a nation specializes in certain goods to raise its exports, its resources move away from other goods that are also needed and are therefore imported. In other words, as exports expand, so must imports. This process is critical to gains from trade.

Trade Deficit Impacts on Economies

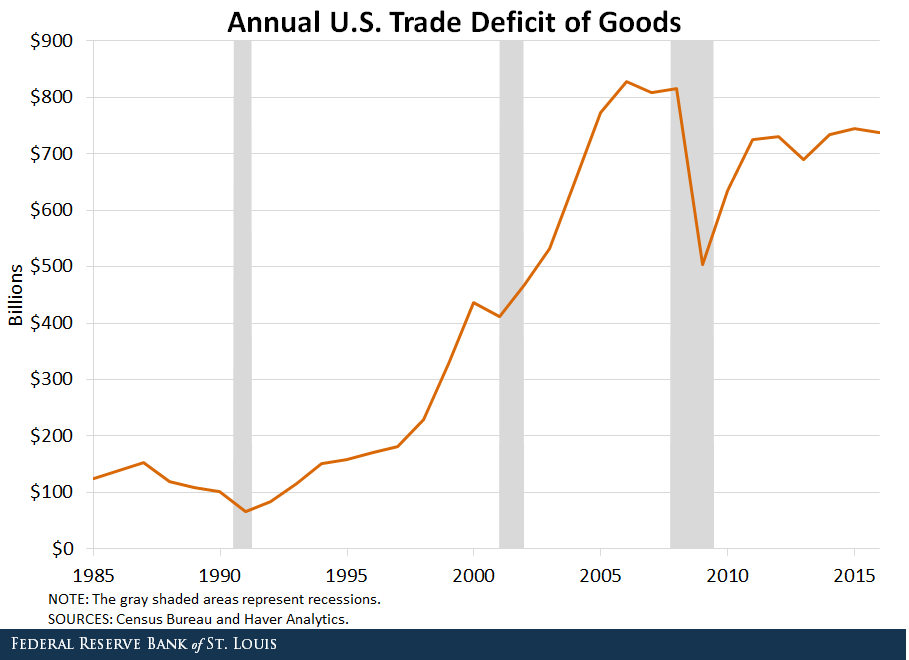

But, are trade deficits harmful for an economy? The figure below shows that the U.S. trade deficit rose every time the economy made its way out of the last three recessions.

In these contexts, a rising trade deficit was associated with greater vitality of the U.S. economy, where consumption and investment picked up as business optimism rose. Therefore, rather than attributing rising trade deficits to trade openness, we should be looking at underlying macroeconomic factors behind trade deficits. 2

Trade and Inequality

Given the current state of inequality, we cannot dismiss the potential loss for U.S. labor from greater import competition, even if there are aggregate gains from trade. I will make two points about this.

First, it is debatable whether trade has been a net destroyer of U.S. jobs. A recent study shows that job gains from exports have more than offset job losses from imports in the U.S. between 1995 and 2011. 3

Second, erecting trade barriers may not help reduce job losses. Technological change and automation will incentivize employers to move away from lower skilled jobs that can be easily automated.

What is called for is a better education system to improve skills to levels that are harder to automate and that yield higher productivity and wages. Sensible tax and transfer policies will also help wage growth and help reduce inequality.

Notes and References

1 Piketty, Thomas; Saez, Emmanuel; and Zucman, Gabriel. “ Distributional National Accounts: Methods and Estimates for the United States .” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, October 2017.

2 Bernanke, Ben S. “ The Global Saving Glut and the U.S. Current Account Deficit .” Remarks at the Sandridge Lecture, Virginia Association of Economists, March 10, 2005.

3 Feenstra, Robert C.; and Sasahara, Akira. “ The ‘China Shock,’ Exports and U.S. Employment: A Global Input-Output Analysis .” Working Paper, University of California, Davis, August 2017.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy : Productivity Growth: Learn from Other Countries or Innovate Yourself?

- On the Economy : U.S. Trade Deficit Driven by Goods, Not Services

- On the Economy : Does Trading with the U.S. Make the World Smarter?

Subhayu Bandyopadhyay is an economist and economic policy advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. His research interests include international trade, development economics and public economics. He has been at the St. Louis Fed since 2007. Read more about the author’s work .

Related Topics

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Media questions

All other blog-related questions

Chapter 5 Introductory Essay: 1800-1828

Written by: Todd Estes, Oakland University

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain the context in which the republic developed from 1800 to 1828

Introduction

In 1800, the Federalist Party controlled both houses of Congress, John Adams was president, the Sedition Act was still in place, and the nation was reeling from the crises sparked by the Quasi-War with France. By the end of 1828, the Federalist Party was extinct and the Jeffersonian Republicans had completely triumphed, though often through Hamiltonian policies. The nation was in the midst of a period of tremendous growth in nearly all realms, particularly economic and territorial. Andrew Jackson had defeated John Adams’s son, incumbent John Quincy Adams, to win the presidency. Jacksonianism signaled the expansion of suffrage to all white men and their widespread, democratic political participation in an exceptional manner, though women and African Americans were not included. A new post-Revolutionary generation built the new nation as farmers and merchants, as well as national leaders.

Compare the presidential portrait of (a) Andrew Jackson by Ralph Eleaser Whiteside Earl in 1837 with the presidential portrait of (b) John Quincy Adams by George Peter Alexander Healy in 1858. In what ways are they similar and different? What were the artists trying to convey?

Jeffersonian America

Thomas Jefferson’s election to the presidency was secured narrowly, and only after thirty-six contentious ballots in the House of Representatives, which had to break an electoral-vote tie between Jefferson and Aaron Burr (see the Was the Election of 1800 a Revolution? Point-Counterpoint). The Jeffersonian Republicans also took control of the House and Senate as well as many state legislatures. Jefferson’s unique leadership style was nimble, and it proved to be popular. His relaxed personality and good manners made him an exceptional host who often disarmed guests at his dinners and social gatherings. He thought the Federalists had created a presidency full of monarchical trappings, and he made the office appear more democratic.

Jeffersonian Republicans believed in decreasing the size of government by cutting taxes and working to eliminate the debt. They favored an agriculture-based economy and praised the ideal of the independent farmer, though agriculture in the country ranged from small independent farms to large plantations. The Jeffersonians continued their antipathy toward Great Britain in the Napoleonic Wars. Although they held an ideological belief, grounded in the American Revolution, that power could easily be abused, Jefferson himself exercised strong executive power and interpreted the Constitution broadly.

Although Jeffersonian Republicans did not destroy the national bank, they refused to renew its charter, and they encouraged the growth of state banks. In their first congressional session in 1801, Jeffersonians repealed all internal taxes, cut spending, and began to pay off the debt as quickly as possible. They preferred that raising tax revenue be left to the state governments. By 1812, they had shaved $27.5 million from a debt once gauged at nearly $83 million. Furthermore, they stepped back from the idea of government interference in the economy, preferring to let individual decisions by citizens drive the economy, instead of a national policy. These political and ideological preferences placed more power in the hands of private citizens and their local governing bodies, fueling the growth of political democracy and of individual liberty, two key components of Jeffersonianism and examples of rising democratization.

The Supreme Court became involved in the politics of the Jefferson administration, notably in the famous case of Marbury v. Madison (1803). Chief Justice Marshall’s ruling was masterful. The 1801 Judiciary Act expanded the number of federal judges and, as outgoing president, Adams had made several “midnight” appointments before Jefferson took office. One of the appointed justices, William Marbury, did not receive his commission for the office from incoming Secretary of State James Madison and sued for it to be delivered to him. The Court agreed that Marbury had a right to the commission but declared that part of the Judiciary Act of 1789 was unconstitutional, thus restricting its own power to order the commission to be given. In this way, Chief Justice Marshall avoided a direct political collision with Jefferson (who sought to reverse Adams’s last-minute appointments of Federalist judges to the bench). Marshall then also asserted the Court’s power to interpret the Constitution (by declaring part of the act unconstitutional), because it was “emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” The ruling helped establish the principle of judicial review, though it did not claim the Court had an undisputed right to interpret the Constitution. But even within the limits of a narrow decision, it sent a very strong statement about the role of the Court in future matters (see the Marbury v. Madison Decision Point).

Watch this BRI Homework Help Video on Marbury v. Madison for a summary of Chief Justice Marshall’s decision:

The Jefferson administration is notable for skilled diplomacy, opportune circumstances, and, when it came to the Louisiana Purchase, plain good luck. American diplomats found Napoleon ready to sell the entire Louisiana Territory for the remarkable price of only $15 million. An unprecedented windfall, the purchase doubled the size of the country, stretching from the Mississippi River to the Rockies, at a bargain price. The purchase created ample room for the development of Jefferson’s “empire of liberty” by opening a vast tract of highly fertile soil for farmers. It removed a European rival’s presence from North America, which had great strategic importance for the nation.

(a) This 1804 map shows the territory added to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Compare this depiction with (b) the contemporary map. How does the 1804 version differ from what you know of the geography of the United States? (attribution (b): Copyright Rice University OpenStax under CC BY 4.0 license)

But nothing in the Constitution gave the president the specific power to make such a purchase, and as a strict constructionist, Jefferson was caught in a bind. He argued that the purchase was so beneficial to the future good of the country that no president could dare pass it up and bent his principles to a more Hamiltonian loose construction. Thus, he overcame his own doubts about the constitutionality of such a move and urged Senate Republicans to ratify the purchase as a treaty, which they did by a vote of 24 to 7, and the House of Representatives introduced a bill appropriating the funds. The Federalists fiercely opposed the purchase because they feared the movement of Jeffersonian Republicans into the new lands, with the potential to expand their political power. However, public response to the purchase was overwhelmingly positive.

Americans knew almost nothing about the newly purchased land itself. To investigate it, Jefferson named Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to form an exploratory expedition. Their team spent two years trekking from St. Louis to the Pacific and back, drawing maps, collecting samples, taking detailed notes, and compiling drawings of their findings. Meanwhile, a Shoshone woman and interpreter named Sacagawea helped them navigate interactions with the various American Indian tribes they encountered. The Lewis and Clark expedition made it abundantly clear just how valuable and important the new territory would be to the young nation (see the The Lewis and Clark Expedition Narrative and The Journals of Lewis and Clark, 1805 Primary Source).

The good fortune and nearly unbroken record of success of Jefferson’s first term resulted in his landslide reelection in 1804. Jefferson received 162 electoral votes, vanquishing his opponent, South Carolina Federalist Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, who received 14. Even Massachusetts, the former Federalist base camp, voted for Jefferson in 1804. But Jefferson’s success came to a crashing halt during his second term, primarily due to the renewed conflict between Great Britain and France. Americans insisted on their right to trade with both warring nations. Neither the French nor the British were willing to allow U.S. goods to get through to the other nation. They blockaded each other and violated American neutral rights.

Between 1793 and 1811, the British also impressed nearly ten thousand American sailors into service in the British Navy. The worst incident by far, however, occurred just off the coast of Norfolk, Virginia, in June 1807, when the H.M.S. Leopard fired upon the U.S.S. Chesapeake , killing three and wounding eighteen. Four alleged deserters from the Royal Navy were carted off the Chesapeake, one of whom was hanged immediately as an example to the others.

Americans were furious; some demanded retaliation and even war. Jefferson proposed instead an embargo on all U.S. ships leaving the nation’s harbors. There would be no export of U.S. goods to any nation nor any imports, to force the European powers to renounce interference with American trade and seizures of ships. The Embargo Act of 1807 primarily hurt U.S. trade, however, with exports collapsing from $108 million to $39 million, and it failed to coerce either the British or French to respect American neutral rights. The embargo was especially unpopular in New England, where it grounded trade and sparked a political revival among the Federalists in the 1808 elections. Jefferson left office in March 1809, despondent over the embargo’s failure.

In this political cartoon criticizing the Embargo Act of 1807, a snapping turtle named Ograbme (embargo spelled backward) is biting the merchants.

In 1808, James Madison was elected Jefferson’s successor and continued the trade restrictions he had supported as secretary of state. Jefferson had signed Congress’s repeal of the embargo on March 1, 1809, days before leaving office. At the start of Madison’s presidency, Republicans in Congress passed the Non-Intercourse Act, which forbade the importation of French and British goods but allowed American ships to leave their harbors and trade with any nation except the two belligerents. That measure was also unenforceable and led to numerous violations by American shippers, who continued to trade with the British and the French. This second failed attempt to regulate trade with the warring powers gave way to Macon’s Bill No. 2, which allowed the United States to reopen trade with all nations, including England and France, and stipulated that if either country renounced its restrictions on American shipping, the United States would cut off its trade with the other.

The War of 1812

The wily Napoleon deceived Madison by announcing he was repealing his trade decrees, prompting the Americans to renounce trade with the British. But the French did no such thing; they continued to seize ships—more than the British did between 1807 and 1812. Despite this betrayal by the French, tensions between the Americans and British ratcheted upward. Some Americans welcomed another war with the British, seeing a military conflict as a way of reasserting national pride, and “War Hawks” in Congress such as Kentucky’s Henry Clay argued that honor demanded a fight. Besides national honor, these southern and western members of Congress also wanted to invade Canada to expel the British and expand the frontier as a way to expel the Native Americans. Madison did not seek war but found himself under increasing pressure to ask Congress for a declaration. Despite strong opposition from Federalists and a significant number of Republicans, Congress voted to declare war on Britain on June 18, 1812, and what some Americans came to think of as a second war for independence was soon underway.

A political cartoon from about 1813 depicting Lady Columbia as the United States (left) Napoleon as France (middle) and John Bull an imaginary figure representing Britain (right). Lady Columbia attempts to lecture John Bull on free trade and a ship’s right to free passage of the seas. John Bull doesn’t want to listen and instead reads a book that states “Power constitutes right.”

The British were preoccupied with the fighting in Europe and at first devoted little attention to North America. Meanwhile, the United States launched unsuccessful campaigns against the British in Canada and engaged the British navy in sea battles. However, various tribes in the Northwest had joined together in a confederacy under the leadership of Shawnee Tecumseh and his brother, the visionary prophet Tenskwatawa. They decided to fight with the British to resist further white encroachment into the area. Thus, the British and Indian confederacy fought against American settlers throughout the Great Lakes area during the war.

In 1814, the British launched three major operations across the United States: in the Chesapeake Bay area, at Lake Champlain in New York, and at the mouth of the Mississippi River. In August, British soldiers routed poorly trained U.S. soldiers and seized Washington, DC. They burned the White House, forcing Madison and the government to flee in what was the embarrassing low point of the war for the United States. The British then turned north toward Baltimore and assaulted Fort McHenry, held by the Americans, but failed to take it (see the Fort McHenry and the War of 1812 Narrative). The British invasion in New York was also turned back as the Americans secured the nation’s northern border against heavy odds. Finally, in December 1814, British troops landed at New Orleans, attacked well-entrenched American forces commanded by Andrew Jackson, and suffered a crushing defeat (see the Old Hickory: Andrew Jackson and the Battle of New Orleans Narrative).

Watch this BRI Homework Help video on Early 1800s U.S. Foreign Policy for a comprehensive review of the early republic’s foreign affairs:

Because of slow communications, the Battle of New Orleans occurred shortly after the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, which had already ended the war. The treaty was inconclusive, reflecting the fact that the conflict had been largely a stalemate. Both sides agreed to return to the “status quo antebellum,” the conditions that had existed at the start of the conflict, and the maritime violations were not resolved. One decisive loser of the conflict turned out to be the Federalists. They had opposed a popular war that led to patriotic fervor and were against the trade restrictions, which had hurt New England trade. Some members of the Federalist Party gathered in convention at Hartford, Connecticut, in late 1814 and early 1815, where talk of a separate New England confederacy struck many Americans as disloyal. And the timing discredited the party, because news of the Hartford convention reached many Americans at nearly the same time as news of the great victory at New Orleans and the peace treaty. As a result, the Federalists were soon spent as a political force and the party disappeared (see the The Hartford Convention Decision Point).

The war was also particularly disastrous for Native Americans. The British had been their allies and had provided them with leverage in dealing with the Americans. When the British withdrew from the United States, the outnumbered and weakened Native Americans had no counterweight remaining. On top of this, the Shawnee lost their great leader Tecumseh, who was killed by U.S. forces at the Battle of the Thames in 1813 (see the Tecumseh and the Prophet Narrative). These twin blows left American Indians isolated and increasingly at the mercy of land-hungry whites, who continued to push westward after the war, claiming Indian territories as their own. American Indians soon discovered the war and its consequences left them more vulnerable to removal.

In Washington, however, amid celebratory patriotism, the Jeffersonian Republicans enjoyed one-party rule in a time called the “Era of Good Feelings.” In 1816, Madison left office and his ally James Monroe came to the presidency. Monroe’s term was not without controversy, and the era of one-party domination was rather short-lived because different sectional and ideological factions began to emerge among the Jeffersonian Republicans. Nevertheless, Monroe was reelected virtually without opposition in 1820. Three years later, he issued a major statement of American foreign policy known as the Monroe Doctrine, which guided the nation’s diplomatic principles for almost two centuries. It restated the pledge of George Washington’s 1796 Farewell Address that the United States would not meddle in European affairs, but it also warned Europeans that the Americas were not open to any further colonization by rival powers (see the The Monroe Doctrine, 1823 Primary Source).

Market Revolution and Transportation Revolution

Even as the War of 1812 was ending, the United States was already being reshaped by three major transformations. The Market Revolution and the Transportation Revolution changed the way Americans worked and lived, and each helped create a new integrated national economy that, in turn, transformed the way the nation bought and sold goods, manufactured items for consumption at home and abroad, and engaged in trade across the Atlantic world.

The years before and during the War of 1812 marked a turning point for the U.S. economy. With access to British goods blocked by embargo or war, the first years of the nineteenth century stimulated tremendous growth in manufacturing, especially in textiles. The end of the war moved a great deal of capital back into the economy, and government policies that encouraged economic growth, such as a protective tariff, a national bank, and aid to internal improvements, spurred development. President Madison and Jeffersonian Republicans in Congress chartered the Second National Bank, the protective tariff of 1816 (which raised rates by an average of 25 percent), and debated spending on canals and roads. Federal spending on internal improvements failed because Madison, Monroe, and their allies in Congress thought it was unconstitutional and required a constitutional amendment. Most of the spending on infrastructure thus was done by state governments and private investors.

The first few decades of the nineteenth century saw the rise of a truly national market system, with the agricultural economy becoming more varied and diversified. As the United States developed more of its own manufacturing capacity, it relied less on foreign trade for goods and more on its own production. Americans began trading more with each other, shipping resources like cotton from the South to northern textile factories, where they were made into finished goods and then sold around the nation, transported overland on roads and by water on rivers and canals.

With the help of the cotton gin, the South grew and exported millions of pounds of cotton to British markets. By 1840, the United States was growing approximately 60 percent of the world’s cotton supply, and cotton made up two-thirds of American exports. Northern factories manufactured the cotton into cloth, and northern shipping transported the cotton and finished textiles to Europe, though British mills dominated the world market. Southern planters invested their profits even more heavily in enslaved persons and in land, because these were the two essentials of cotton production. In the North, small-scale manufacturing by artisans began to give way to larger-scale factories with machinery that could turn out large amounts of goods, such as the famous mills in Lowell, Massachusetts.

After the invention of the cotton gin, the production of cotton increased dramatically. By 1840 the United States was producing approximately 60 percent of the world’s supply. (credit: “U.S. Cotton Production 1790-1834” by Bill of Rights Institute/Flickr CC BY 4.0)

These market expansions also changed women’s role on the farm. In addition to the heavy burdens of domestic and farming chores, women now took in piecework like sewing and knitting. Instead of producing only enough for household consumption, they participated in the market revolution by making or growing surplus for sale in local markets. Young farm women supplied the labor at the Lowell mills. Most women, however, participated in manufacturing by taking part in a larger production process by making small items inside their homes in a system called “outwork.” With workplace and home becoming more distinct from each other in the North, separate spheres for men and women emerged. Men increasingly joined the public world of work and commerce, while women, even though some young women worked in New England factories, were relegated to the private sphere of home life, where they were expected maintain a home based on Victorian virtues for their husbands and children according to the “cult of domesticity.” Piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity were the desired traits that characterized what was also known as the “cult of true womanhood.” Magazines and treatises on homemaking provided middle-class women with advice on household matters and child-rearing and shaped an ideal of comfortable domestic bliss for families. Of course, such aspirations were mostly unattainable for working-class, rural, and free black women, to say nothing of many thousands of enslaved women.

For the market economy to become truly national, a transportation network linking various parts of the country was essential so goods and raw materials could move easily, quickly, and inexpensively. The transportation revolution that brought this about was bolstered by three central mechanisms: canals, steamboats, and railroads. State governments and private investment built thousands of miles of canals, like the Erie Canal in upstate New York (see the The Building of the Erie Canal Narrative). Canals made it possible to transport goods on flatboats connecting various rivers and waterways, helping to link the nation’s economy. Steamboats moved people and goods upstream against river currents and significantly reduced the time and cost of shipping goods and resources on rivers and major waterways. Eventually, water travel was overtaken by the rise of railroads, which could move people and goods even faster, effectively shortening time and distance. The 1830s were a decade of crucial growth for the rail industry, and by 1840, there were 3,300 miles of railroads in the United States. Because the nation seemed always to be in motion, with goods and products and people in constant transit, the market revolution also helped encourage greater individualism and democratization.

The United States experienced incredible growth in population as well, driven by natural increase and by immigration. The population doubled during the period 1800–1828 and continued to double every twenty-two years until the Civil War, from approximately 4 million people in 1790 to 9 million in 1820, and to 23 million in 1850. This enormous growth put pressure on resources and the environment, and it fostered political, economic, and social conflicts. It also gave rise to the growth of cities and to the westward spread of the nation.

Government and the Market Revolution

After the War of 1812, some politicians supported nationally funded internal improvements, a national bank, and a protective tariff under a philosophy known as economic nationalism. The charter for the original Bank of the United States expired in 1811 and was not renewed, producing economic chaos during the war. President Madison, long an opponent of Hamilton’s national bank on constitutional grounds, supported the bank’s recharter in 1811, but the Republican Congress defeated it. In 1816, the Republican Congress relented and rechartered the bank for twenty years.

The Tariff of 1816 protected American industry from European competition. Although it increased the cost of goods, the tariff was widely supported, especially in the North and even by some in the South. South Carolina’s congressional representative John C. Calhoun supported a protective tariff and put through the House a plan to fund internal improvements. This time, opposition came from New England and the South, because the West would primarily benefit from the resulting roads and waterways. President Madison vetoed the bill, however, because he thought it was unconstitutional unless an amendment was passed empowering the government to engage in such projects. Otherwise, states had responsibility for internal improvements.

This portrait of John C. Calhoun was painted by George Peter Alexander Healy around 1845 when Calhoun was serving as the sixteenth secretary of state. Calhoun was a fixture in U.S. politics for the first half of the nineteenth century serving as congressional representative senator vice president secretary of state and secretary of war.

Economic nationalism prevailed in a series of Supreme Court decisions. In cases such as Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1816), McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), and Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), John Marshall’s Supreme Court moved boldly to assert the rights of the national government over the states and to reinforce the power of contracts and charters that favored businesses and corporations. In the process, the Court expanded the reach and extent of the federal power over commerce. These rulings put the power of the nation’s judicial branch on the side of consolidation, centralization, the national government, and private industry (see the John Marshall’s Landmark Cases DBQ Lesson).

Expansion Population of the West and Slavery

As the nation and the national economy moved west, so too did the institution of slavery. President Thomas Jefferson had signed the bill outlawing the importation of enslaved persons in 1808, but slavery did not die of its own volition, as the founders hoped. Thanks to the technological breakthrough of the cotton gin and to the increasing demand for cotton, slavery’s hold on the American economy strengthened. White farmers surged westward into the new states of Alabama and Mississippi and states created from the Louisiana Territory, bringing their slaves with them to raise cotton. In short, slavery became even more deeply entrenched in the United States from 1800 to 1828. (See the Changing Views of Slavery Mini-DBQ Lesson.)

The graph shows rapid population growth in the South from 1790 to the Civil War. What factors might account for this rate of population growth? (credit: “Population of the South 1790-1860” by Bill of Rights Institute/Flickr CC BY 4.0)

The systems of slavery and the experience of enslaved persons in the nation varied widely. Slaves worked on different crops depending on the region and labored on large plantations, on small farms, and in urban areas. A booming domestic market traded enslaved persons, whose value rose along with the profits generated by their labor. As the slave economy took deeper hold, economic differences emerged between poor and middling white farmers who owned few or no slaves and wealthy planters who owned many.

The enslaved faced tightening legal and policing controls on their movement and harsher discipline imposed by their owners. Southerners viewed slaves through the lens of property rights and increasingly strengthened the hold of owners on their chattel slaves. Slave rebellions were put down swiftly and ferociously. In 1800, Virginian slave Gabriel Prosser sought to lead a slave revolt for equal natural rights, but dozens of the slaves were captured before they could begin the revolt and were hanged. In 1822, South Carolinian Denmark Vesey, a free black man, was inspired by the Christian ideals of the Second Great Awakening and tried to start a revolt, but it met the same fate as Gabriel’s Rebellion. Still, the possibility of rebellion and violence remained a powerful dread among white southerners of all classes, who reacted with swift vengeance to suppress any slave revolt.

National Politics