- Commercial Law

- Constitutional Law

- Criminal Law

- Law Related Discussion

- Legal Ethics

- Procedural Law

- Special Penal Laws

- What is the Importance of Dangerous Drugs Law?

by RALB Law

Dangerous drugs existed way centuries before. From herbal produce to chemical-based drugs, all of them have adverse effects to our body system.

Science has proven the detrimental effects of the usage of these dangerous drugs. Their chemical composition primarily affects our mental state, and their consequences are either short-term or permanent. Even when a person has stopped the use of said drugs, its damage may be continuous.

Dangerous drugs, just as human beings, evolve. When our ancestors discovered drugs as products of herbs and plants coupled with developing societies, people discovered the scientific mixing of various chemicals, which, in effect, produces these detrimental drugs.

Dangerous drugs can now be either injected, ingested, and inhaled. For instance, the effect of a drug injected goes directly in our bloodstream. Thus, the aftermath is immediate. Even a medically prescribed drug, when overused can cause adverse outcome, worse of which is death.

Although not all drugs are dangerous, we should be mindful that what we are taking are:

1) those prescribed by a duly licensed physician;

2) are within the limit of dosage given to us; and

3) the most important is that the drug is not enlisted as one of those narcotics and other dangerous drugs.

Now, as the international community are well aware of the damaging side effects of these dangerous drugs not only to one’s person, but also to the greater society, these countries have promulgated their respective laws which regulate and sanction the use of dangerous drugs.

The importance of enacting these laws is to protect mainly the health and well-being of every citizen. Also, with the regulation of these dangerous drugs, the public order and integrity of state’s territory is ensured.

What is Dangerous Drug Act?

Dangerous Drugs Act is a piece of legislation which prohibits and regulates the manufacture, trade, usage, and maintenance of illegal drugs in one’s territory.

The first United States Anti-drug law was enacted way back November 15, 1875. It was enacted in San Francisco where it banned opium smoking and opium.

The measure on banning of opium smoking and opium dens were subsequently followed by Virginia City, and Carson in Nevada, Cheyenne, Wyoming and Montana on the succeeding years.

On February 26, 1909, the first international conference was convened in Shanghai, China to discuss the possible measures and regulations to address the world’s narcotic problems.

The Shanghai Opium Commission of 1909 was the precedent of the first international drug control treaty – the International Opium Convention of The Hague of 1912.

Due to this international treaty, the importation of opium has been vastly affected as the same was declined in several countries.

Then came 1946 when the defunct League of Nations transferred the drug control in international sphere to the newly created United Nations.

That same year when the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) created the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs to assist in the supervision on the implementation and application of the international drug control treaties.

Internationally, the control on dangerous drugs is based on three major treaties, namely:

1) The Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961, which was subsequently amended in 1972;

2) the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971; and

3) the United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances of 1988.

What is the Dangerous Drugs Act in the Philippines and What is its Purpose?

In the Philippines, the first law that prohibits the use of opium was codified in the Revised Penal Code, specifically in Articles 190, 191, and 193 until it was repealed by Republic Act No. 6425,(( Republic Act No. 6425 , The Dangerous Drugs Act of 1972)) or the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1972.

Until their ( Drug Provisions under the Revised Penal Code ) repeal in 1972, only opium, cocaine, alpha and beta eucaine, Indian hemp, are classified as prohibited drugs, as provided under Article 190 (1) of the Revised Penal Code.

The new law in 1972 added heroin and morphine; coca leaf and its derivatives alpha and beta eucaine; hallucinogenic drugs, such as mescaline, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and other substances producing similar effects were added in the list of prohibited drugs.

Republic Act No. 9165(( The Dangerous Drug Act of 2002 )) or the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002, as amended by R.A. No. 10640, repealed the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1972, is currently the governing law on prohibited drugs.

RA 9165 basically replaced the term “prohibited drugs” in the old laws, with “dangerous drugs,” thereby enlisting in the law all those dangerous drugs “listed in the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, as amended by the 1972 Protocol.” (Sec. 3,[j], RA 9165)

Moreover, the new law considers as dangerous those drugs “without having any therapeutic value or if the quantity possessed is far beyond therapeutic requirements.” (Sec. 11, RA 9165)

The purpose of the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Law is anchored in its Declaration of Policy of the State to “safeguard the integrity of its territory and the well-being of its citizenry particularly the youth, from the harmful effects of dangerous drugs on their physical acts.” (Section 2, RA 9165)

What is the Target of Republic Act No. 9165

The first target of this law is to safeguard the integrity of its territory – When we speak of integrity, it is the quality of honesty, having strong moral principles and uprightness. On the other hand, territory is the “fixed portion of the surface of the earth inhabited by the people of the State.” (Cruz, 2014, Page 22)

We have to see to it that we are complying faithfully with our international obligations, more specially with the international drug control treaties. We have adopted as generally accepted principles of international law under the doctrine of pacta sunt servanda .

By observing this obligation , the State has the duty to ensure that the citizens in its territory, at the very least, are not influenced with dangerous drugs.

The second target of this law is the well-being of its citizenry particularly the youth, from the harmful effects of dangerous drugs on their physical and mental well-being.

The State, in its capacity as Parens Patriae, has the obligation to ensure that its citizenry, particularly the youth, will not be destructed by the harmful effects of dangerous drugs.

Medical researches show that the effect of dangerous drugs are mostly impacted in the brain of its users that is why most users have been labeled “high” due to the manipulations of chemical components of these dangerous drugs to the our systems.

Who are Punished by the Law and Why are they Punished?

Republic Act No. 9165(( The Dangerous Drugs Act , Supra.)) punishes the following persons:

1] Those involved in the Sale, Trading, Administration, Dispensation, and Delivery:

1.a] Persons who buy and sell dangerous drugs are punished by law. In order to convict them, the prosecution must prove the identity of the buyer and the seller, the object of the sale and its

1.b] Persons who are engaged in the trading or the transactions involving the illegal trafficking of dangerous drugs using electronic devices or acting such a broker in any of those transactions. It is necessary that there is money or consideration

1.c] Persons without the authority to administer dangerous drug into the body of any person, with or without the latter’s knowledge, by injection, inhalation, ingestion or other means, or by assisting any person in administering said dangerous drug to himself, unless these persons are duly licensed practitioner, and the purpose of administration is for medication.

1.d] The law also punishes any person who passed on possession of a dangerous drugs to another, and such delivery is not authorized by law. Further, for a person to be punished, the “accused must knowingly made the delivery. Worthy of note is that the delivery may be committed even without consideration.” (People vs. Maongco, G.R. No. 196966, October 23, 2013)

2] Those who manufacture illegal drugs or those involved in the production, preparation, compounding or processing of any dangerous drug and/or controlled precursor and essential chemical, either directly or indirectly or by extraction from substances of natural origin, or independently by means of chemical synthesis or by a combination of extraction and chemical synthesis, and shall include any packaging or repackaging of such substances, design or configuration of its form, or labeling or relabeling of its container. (Sec. 3[u], RA 9165)

3] Those who are in possession of any dangerous drug without lawful authority (Sec. 11, RA9165) and drug paraphernalia. (Sec. 12, RA 9165)

4] Those who operate or maintain a drug den, dive or resort where dangerous drug is used or sold in any form or any controlled precursor and essential chemical is used or sold in any form. Moreover, this provision also punishes the employee of such den, dive, or resort who is aware of the nature of such place, as well as those persons visiting the place who are also aware of the nature of such place. (Sec. 6, RA 9165

5] Those persons using such dangerous

6] Those persons who are unnecessarily prescribing dangerous drugs and who unlawfully prescribe dangerous

7] Those who cultivate or culture dangerous

8] They are punished, even when the criminal intent is lacking. RA 9165 is a special penal law, thus the defense of good faith is inapplicable in crimes mala prohibita .

What are the Common Acts Punished under RA 9165 and their Respective Penalties?

There are several acts punished under RA 9165, but these are the most common acts in our jurisdiction:

Section 5 of RA 9165 punishes any person, who, unless authorized by law, shall sell, trade, administer, dispense, deliver, give away to another, distribute dispatch in transit or transport any dangerous drug, including any and all species of opium poppy regardless of the quantity and purity involved, with the penalty of life imprisonment to death and a fine ranging from P500,000.00 to P1,000,000.00. Sec. 5 moreover punishes in its maximum penalty, persons who shall perform these acts within 100 meters from the school, or drug pushers who shall use minors or mentally incapacitated individuals as runners or couriers.

The penalty imposed in these acts are reasonable considering that this law is enacted to protect the integrity of the territory and well-being of the citizenry, specially the youth.

It is reasonable to impose maximum penalty of life imprisonment in acts transgressing and compromising the public order and integrity, and the State in its Parens Patriae capacity, has the obligation to protect to the fullest extent the interests beneficial to the youth of this country.

Section 6 of RA 9165 punishes any person or group of persons who shall maintain a den, dive or resort where any dangerous drug is used or sold in any form with the penalty of life imprisonment to death and a fine ranging from P500,000.00 to P1,000,000.00, while Section 8 of the law punishes any person who, unless authorized by law, shall engage in the manufacture of any dangerous drug, with a penalty of life imprisonment to death and a fine ranging from P500,000.00 to P1,000,000.00.

The penalties provided under the aforementioned provisions are again reasonable as the maintenance of drug dens, dives, or resort and the manufacture of any dangerous drugs play vital role in the malignant commerce of dangerous drugs in the society.

With them, the trading of dangerous drugs commences. Hence, by life imprisonment, this law will be of great help to eradicate the roots of dangerous drugs.

The penalty for the illegal possession depends on the quantity confiscated by the authorities upon the person of the accused. Section 11 governs the punishment for illegal possession of dangerous drugs.

The penalty of life imprisonment to death and a fine ranging from P500,000.00 to P1,000,000.00 is imposable upon any person who shall unlawfully posses 10 grams or more of opium, morphine, heroine, cocaine, marijuana resin or marijuana resin oil, ecstasy, paramethoxyamphetamine (PMA), trimethoxyamphetamine (TMA), lysergic acid diethylamine (LSD), gamma hydroxyamphetamine (GHB), and those similarly designed; 50 grams or more of methamphetamine hydrochloride or “shabu”; and 500 grams or more of marijuana.

The next lower imposable penalties are applicable in cases of lesser quantities of dangerous drugs seized or confiscated.

The penalty for illegal possession of drug paraphernalia is imprisonment ranging from 6 months and 1 day to 4 years and a fine ranging from P10,000.00 to P50,000.00.

All told, the penalties provided under this law are reasonable. The law itself is a valid exercise of police power. It is the power of the state to promote public welfare by restraining and regulating the use of liberty and property.

It is the most pervasive, the least limitable, and the most demanding of the three fundamental powers of the State. ( Gerochi v. Department of Energy, as cited in Southern Luzon Drug Corporation vs. DSWD, G.R. No. 199669, April 25, 2017)

Related Jurisprudence

The Supreme Court, through the years, have promulgated several cases in relation to violations of RA 9165 and set many precedents to be followed by all inferior courts in deciding drugs cases at trial court level.

In cases of illegal possession of drugs or drugs paraphernalia:

Criminal intent is not an essential element.

In the case of People vs. Lagman,(( G.R. No. 168695, December 8, 2008 )) the Supreme Court held that:

“[i]llegal possession of regulated drugs is mala prohibita, and, as such, criminal intent is not an essential element . However, the prosecution must prove that the accused had the intent to possess ( animus posidendi ) the drugs. Possession , under the law, includes not only actual possession, but also constructive possession. Actual possession exists when the drug is in the immediate physical possession or control of the accused. On the other hand, constructive possession exists when the drug is under the dominion and control of the accused or when he has the right to exercise dominion and control over the place where it is found. Exclusive possession or control is not necessary. The accused cannot avoid conviction if his right to exercise control and dominion over the place where the contraband is located, is shared with another .” Hence, a person may be held convicted even if the authorities found dangerous drugs, even though not in in his actual possession, but in a location where he can exercise proximate control over the subject to be seized.(( People vs. Lagman , Ibid.))

Moreover, “mere possession of a prohibited drug constitutes prima facie evidence of knowledge or animus possidendi sufficient to convict an accused in the absence of satisfactory explanation.” (People vs. De Jesus, G.R. No. 198794, February 6, 2013)

The Supreme Court has distinguished as well the terminologies:

“Marking vs. Chain of Custody”

In the case of People vs. Ameril,(( G.R. No. 203293, November 14, 2016 )) the Supreme Court ruled that:

“Marking” means the placing by the apprehending officer or the poseur-buyer of his/her initials and signature on the items seized to identify it as the subject matter of the prohibited sale. Marking after seizure is the starting point in the custodial link and is vital to be immediately undertaken because succeeding handlers of the specimens will use the markings as reference. Chain of custody is defined as “the duly recorded authorized movements and custody of seized drugs or controlled chemicals or plant sources of dangerous drugs or laboratory equipment of each stage, from the time of seizure/confiscation to receipt in the forensic laboratory to safekeeping to presentation in court for destruction.” Such record of movements and custody of seized item shall include the identity and signature of the person who held temporary custody of the seized item, the date and time when such transfer of custody were made in the course of safekeeping and use in court as evidence, and the final disposition.(( People vs. Ameril , Ibid.))

The Supreme Court moreover added guidelines in chain of custody in a buy-bust situation.

In People v. Kamad(( G.R. No. 174198, January 19, 2010 )) (624 SCRA 289, 304-306 [2010]), the Court identified the links that the prosecution must establish in the chain of custody in a buy-bust situation to be as follows: first , the seizure and marking, if practicable, of the illegal drug recovered from the accused by the apprehending officer; second , the turnover of the illegal drug seized by the apprehending officer to the investigating officer; third , the turnover by the investigating officer of the illegal drug to the forensic chemist for laboratory examination; and fourth , the turnover and submission of the marked illegal drug seized by the forensic chemist to the court.

Come 2018, when the Supreme Court imposed a stricter and mandatory requirement for drug enforcement authorities in conducting anti-dangerous drug operations. This was elucidated in the case of People vs. Romy Lim. Justice Peralta, stressed down the following policy to be enforced in connection with arrests and seizures in cases involving dangerous drugs, viz:

“In order to weed out early on from the courts’ already congested docket any orchestrated or poorly built up drug- related cases, the following should henceforth be enforced as a mandatory policy:

1] In the sworn statements/affidavits, the apprehending/seizing officers must state their compliance with the requirements of Section 21 (1) of R.A. No. 9165, as amended, and its IRR.

2] In case of non-observance of the provision, the apprehending/seizing officers must state the justification or explanation therefor as well as the steps they have taken in order to preserve the integrity and evidentiary value of the seized/ confiscated items.

3] If there is no justification or explanation expressly declared in the sworn statements or affidavits, the investigating fiscal must not immediately file the case before the Instead, he or she must refer the case for further preliminary investigation in order to determine the (non) existence of probable cause.

4] If the investigating fiscal filed the case despite such absence, the court may exercise its discretion to either refuse to issue a commitment order (or warrant of arrest) or dismiss the case outright for lack of probable cause in accordance with Section 5, Rule 112, Rules of Court”

The declaration as unconstitutional the prohibition against plea bargaining in drug cases, is a landmark case in drugs cases. In the case of Estipona vs. Lobrigo,(( G.R. No. 226679, August 15, 2017 )) the Supreme Court held that:

“[t]he power to promulgate rules of pleading, practice and procedure is now [the Supreme Court’s] exclusive domain and no longer shared with the Executive and Legislative departments.”

The Supreme Court’s sole prerogative to issue, amend, or repeal procedural rules is limited to the preservation of substantive rights, i.e., the former should not diminish, increase or modify the latter.

Thus, the power to promulgate rules of procedure is lodged with the Supreme Court and this cannot be repealed or amended by subsequent substantive laws the Congress has to enact.

Final Thoughts

RA 9165 is a broad yet concise law. It was carefully crafted by our lawmakers. As I have mentioned, this law is a valid exercise of the State’s Police Power.

The proper exercise of the police power requires the concurrence of a lawful subject and a lawful method . ( Gerochi v. Department of Energy, as cited in Southern Luzon Drug Corporation vs. DSWD, G.R. No. 199669, April 25, 2017)

The lawful subject in here is the suppression of the dangerous drugs in our country and the lawful method is to impose the maximum penalty imposable in our jurisdiction to those who will be found guilty of the acts punishable under RA 9165.

The Philippine Government’s obligation with international treaties on drug control is clearly complied with in our jurisdiction.

This is evidenced by the pieces of legislations the Congress of the Philippines passed from the first anti- drug prohibition codified in the Revised Penal Code, until it was repealed by the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1972 and the same has been repealed by the current Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002, which is the governing law concerning illegal and dangerous drugs.

This is a special penal law. Thus, defense of good faith is untenable .

The particular provision in illegal possession is the one of the most commonly filed cases in our Courts and by merely in possession is punishable itself.

It is an elementary rule in Criminal Law that the criminal intent in crimes malum prohibitum is not necessary and cannot be invoked as a defense.

It is because, crime malum prohibitum , in a literal term- PROHIBITS one from doing this and that, as in this case, in RA 9165, it is prohibited to possess dangerous drugs without lawful authority or satisfactory justification.

Imagine a future without dangerous drugs, our world would be forever peaceful and in order.

RALB Law | RABR & Associates Law Firm

Leave a reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked

Name * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Email * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

You cannot copy content of this page

- Subscribe Now

The dangers of the Dangerous Drugs Act

Already have Rappler+? Sign in to listen to groundbreaking journalism.

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – It is one of the Philippines’ main weapons against illegal drugs yet Republic Act 9165 or the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002 looks good only on paper.

With President Rodrigo Duterte’s fight against drugs, this 14-year-old measure was suddenly put under the spotlight.

RA 9165 mandates the government to “pursue an intensive and unrelenting campaign against the trafficking and use of dangerous drugs and other similar substances.”

Under the law, those caught importing, selling, manufacturing, and using illegal drugs and its forms may be fined and imprisoned for at least 12 years to a lifetime, depending on the severity of the crime.

Since the law was passed at a time the death penalty was still applicable, it is the maximum punishment imposed by the original law. This, however, is moot at present as the death penalty was already abolished in 2006.

If such strict law was passed 14 years ago in 2002, the question remains: Why does the multi-billion drug industry remain unstoppable?

Duterte’s strong drive against drugs has raised more questions than answers involving the measure: Is the law effective? What else can be done? What went wrong?

For Senate Majority Leader Vicente Sotto III, principal sponsor of the law, the legislation is anything but a failure.

Had the law been implemented properly and consistently, Sotto said the country’s drug problem would not be as massive as it is now.

“Kaya lumala hindi inimplementa nang tama ang batas noong mga nakaraang taon. Mula 2002 hanggang ngayon, every now and then parang roller coaster, may panahon na aasikasuhin, may panahon na hindi. Talagang execution ang problema. Ang ganda na nga eh,” Sotto told Rappler.

(That’s why it got worse because the law was not properly implemented in the past year. Starting 2002 until now, it’s like a roller coaster. It’s implemented every now and then, there are times it would be prioritized, there are times not. Execution is really the problem. The law is already good.)

Past administrations had their own respective focus. Now, Duterte’s single agenda of fighting criminality has opened the floodgates of issues that had long been neglected.

Politics? PDEA vs DDB

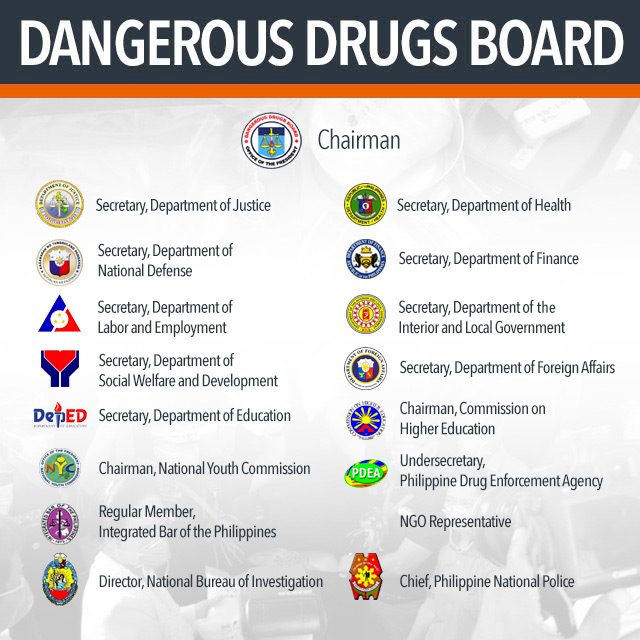

RA 9165 repealed RA 6425 or the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1972. The law mandates the Dangerous Drugs Board to be the policy- and strategy-making body that plans and formulates programs on drug prevention and control.

Article 9, Section 77 of the law states that the DDB “shall develop and adopt a comprehensive, integrated, unified and balanced national drug abuse prevention and control strategy. It shall be under the Office of the President.”

The DDB is composed of 17 members, including the chairman with the rank of Secretary.

The law also created the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA), which serves as the implementing arm of the DDB, and is automatically part of the 17-member DDB.

These two, ideally, work hand in hand to fight drugs. In reality, however, politics and bureaucracy get in the way of things.

The DDB chair has a rank of secretary, while the PDEA Director General is considered an undersecretary. But since it is PDEA that implements the law and does the operations on the ground, Sotto said PDEA tends to reject being under the DDB.

“May leadership problem. Yung PDEA at DDB chair, hindi nagkakasundo. May feeling sila di sila subservient sa isa’t isa. So ang nangyari, ang PDEA feeling nila di sila subservient sa DDB, di nga umaattend ng forum regularly. Magkasama yan sa opisina. Ilang taon yan. Ewan ko kung bakit,” Sotto said.

(There’s a leadership problem. The PDEA and the DDB chairmen are not on good terms. Each of them has a feeling that they are not subservient to each other. So what happens, PDEA feels it is not subservient to DDB, it does not attend regularly. They share the same office. It has been going on for years, I don’t know why.)

DDB Chairman Felipe Rojas Jr, for his part, admitted politics exists inside but downplayed its effect, saying it is not enough to jeopardize the entirety of the anti-drug effort.

“Yung appointment of officials, yung iba hindi qualified, minsan intervention ng pulitika, ” Rojas said. (The appointment of officials – some are not qualified, sometimes politics intervenes.)

This does not come as a surprise to some, as such is the situation in most government offices in the country.

Senator Grace Poe, former Senate committee chair on public order, said the track record of appointees should be checked.

“I really think it all boils down to the credibility of the people you will assign in those posts. In the past kasi, mga nandun sa PNP (Philippine National Police), nandun sa iba’t ibang organizations, so sila-sila pa rin (In the past, those from the PNP are also in other organizations, so it’s just always them). I really think kailangan ma-vet mabuti yung Dangerous Drugs Board (I really think those in the Dangerous Drugs Board should be properly vetted) ,” Poe said.

But while the suggestion is good, the reality is that appointments still depend on one person – the president. He himself chooses who leads the crucial agencies of PDEA and the executive offices that comprise the DDB.

As of posting time, Rojas was already relieved from his post after Duterte ordered appointees of former president Benigno Aquino III to submit a courtesy resignation. The President has now assigned the post to former assistant secretary Benjie Reyes.

As simple as quorum

The politics inside the board may have more repercussions than what meets the eye. Another problem of the board is the lack of quorum, which requires 9 out of 17 members. While it may not necessarily be political, such challenge shows the seemingly shaky dynamics inside, which in turn sheds light on the struggles of policy formation and implementation.

The DDB has 17 members from all aspects of drug rehabilitation precisely because the law wants a holistic approach to the complex drug problem. But while the intent is good, the same could not be said about the agencies involved.

The law mandates that the DDB meet once a week or “as often as necessary at the discretion of the Chairman or at the call of any 4 other members.”

One may call it lucky if the board gets to meet weekly. At the very least, the Board meets once a month, according to Rojas.

Asked if he, as chair, has powers to compel and convince other board members to attend, Rojas only had this to say:

“Very limited, in fact, wala talaga. In some agencies sa abroad, ang DDB ang may hawak ng pondo. As they say, the one who holds the gold rules. Kapag ikaw may hawak ng pondo susunod sa ‘yo yan pero wala sa akin,” he said.

(Very limited. In fact, none. In some agencies abroad, the DDB holds the funds. As they say, the one who holds the gold rules. If you hold the funds, they will follow you but it’s not with me.)

Sotto, former DDB chairman, echoed Rojas’ sentiment.

“’Di nagmi-meet regularly dahilan lagi walang quorum. Hindi uma-attend secretaries. Yung mga secretaries nagpapadala ng undersecretaries, puwede naman yun na representative lang, pero yun mga Usec nila di rin uma-attend eh,” said Sotto.

(The board does not meet regularly, the usual excuse is lack of quorum. The secretaries do not attend. The secretaries send their undersecretaries as their representatives, which is allowed, but the undersecretaries do not attend too.)

The surge in the popularity of Duterte’s anti-drug campaign has given the DDB a huge role to fill, something difficult to accomplish all at once, especially if institutions have long been weak.

“Matagal ang decision-making process – convene the board, magno-notice ka pa. You have to wait for the resolution. Unlike other countries, isa lang ang decision-making at mabilis,” Rojas said.

(The decision-making process takes a while – convene the board, you have to submit notice. You have to wait for the resolution. Unlike other countries, their decision-making process is unified and fast.)

To be concluded – Rappler.com

(READ: Part 2: The dangers of the Dangerous Drugs Act )

Add a comment

Please abide by Rappler's commenting guidelines .

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.

How does this make you feel?

Related Topics

Camille Elemia

Recommended stories, {{ item.sitename }}, {{ item.title }}.

Checking your Rappler+ subscription...

Upgrade to Rappler+ for exclusive content and unlimited access.

Why is it important to subscribe? Learn more

You are subscribed to Rappler+

Access information on Multilateral Environmental Agreements

Comprehensive dangerous drugs act of 2002 (republic act no. 9165)..

This content is exclusively provided by FAO / FAOLEX / ECOLEX

- français

- BAHÁNDÌAN Home

- College of Law

- Juris Doctor

A content analysis of Supreme Court decisions on the acquittal and conviction of drug related cases under R.A. 9165 (otherwise known as the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002)

Thesis Adviser

Share , description, suggested citation, shelf location, physical description, collections.

- Juris Doctor [144]

Related items

Showing items related by title, author, creator and subject.

War on drugs: Critical analysis of the legislation of other countries and their implication to Republic Act Number 9165 or the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002

A review of Supreme Court decisions on drug cases from 2012-2016: In view of proposing amendments to R.A. No. 9165 otherwise known as the “Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002”

A case law approach on the proposed amendments to Republic Act 9165 or The Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002

CPU Henry Luce III Library

EXTERNAL LINKS DISCLAIMER

This link is being provided as a convenience and for informational purposes only. Central Philippine University bears no responsibility for the accuracy, legality or content of the external site or for that of subsequent links. Contact the external site for answers to questions regarding its content.

If you come across any external links that don't work, we would be grateful if you could report them to the repository administrators .

Click DOWNLOAD to open/view the file. Chat Bertha to inform us in case the link we provided don't work.

Adoption of Bill Allowing the Imposition of the Death Penalty for a New Crime. Asia By Grace Keane O'Connor , on 30 April 2021

Philippine House Bill No. 7814 provides the death penalty for a new crime under the 2002 Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act.

Adopted on March 2nd 2021, this Bill comes after years of President Rodrigo Duterte’s unflagging insistence to reintroduce the death penalty to the Philippines, despite the country having abolished the capital punishment for all crimes in 2006. CHR Commissioner Karen Gomez-Dumpit released a statement urging legislators not to pursue this bill.

The Reintroduction of the Death Penalty

The passage of House Bill No. 7814 a is an attempt on the part of the government of the Philippines to reintroduce the death penalty, who, under the leadership of President Duterte, has called for a return to the death penalty since his election in 2016. The bill is aimed at strengthening the country’s drug prevention and control. Section 20 of the bill provides a mandatory penalty of death for a new crime involving the use or implementation of a search warrant based on perjurious or falsified documents or planted evidence. There is also a presumption of guilt if the accused planter does not follow the investigation procedure under Section 19 of the bill. Not only do these provisions demonstrate intent for a broader introduction of the death penalty in the Philippines, but they prevent human rights institutions in the country from carrying out effective work.

The Commission on Human Rights (CHR) has “committed to tirelessly assail” the death penalty in the Philippines. Its reintroduction would violate international obligations made under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and its Second Optional Protocol. Commissioner Gomez-Dumpit highlighted the lack of evidence proving that the death penalty is a deterrent on crime. It does not improve crime rates in countries that retain it, and it also creates further “problems in the disadvantaged, marginalized and vulnerable sectors of society.”

The CHR “most respectfully urge[s] our legislators to pursue bills that would address recovery from the pandemic. We are still in the middle of a pandemic – where thousands of lives have been lost and many lives are still at peril. While we await for the arrival of vaccines in the country, we appeal to our legislators to pursue measures that would allow us to recover not only from COVID-19 but also from the negative effects of the responses to quell it. The reintroduction of the death penalty will create more problems particularly in terms of livelihood that may be lost given the dire economic situation especially of the disadvantaged, marginalized, and vulnerable sectors of society. It may likely lead to the suspension or withdrawal of privileges under the Generalized Scheme of Preferences Plus (GSP+) Program with the European Union. We emphasize that many industries, most especially the agriculture sector, have benefitted tremendously under this trade agreement.” The CHR in the Philippines also noted in the statement that they are ready to work with government to craft “human rights and evidence-based policies” to assure the rights of the accused and to affirm the universal right to life.

Providing for the ‘Presumption of Guilt’

The Bill in question would additionally provide for the ‘Presumption of Guilt’ for people accused of trafficking crimes and involvement with illegal drugs. The system of law in the Philippines adheres to the basic tenet that presumes a person is innocent until proven guilty. Commissioner Gomez-Dumpit highlights in her statement that this is in direct conflict with the constitution. “The presumptions of guilt in the bill goes against this right guaranteed for the accused under the Bill of Rights of our 1987 Philippine Constitution. We note that the bill provides for presumptions of guilt for people accused of being traffickers, financiers, protectors, coddlers and/or being involved in illegal drugs which we strongly believe to be patently unconstitutional”, stated Commissioner Gomez-Dumpit.

This element of Bill No. 7814 emphasises further the dangers of reintroducing capital punishment. The death penalty is an irreversible sentence, and no justice system is free from judicial errors. The ‘Presumption of Guilt’ provision compromises a person’s right to due process. With this bill there is an increased risk of an irrevocable miscarriage of justice.

Creation of Advocacy Brochures for the Philippines

As a part of the World Coalition’s larger project working with countries at risk of reintroducing the death penalty, the Coalition has been working closely with the CHR in the Philippines. An educational and advocacy brochure titled “Keep the Death Penalty Abolished in the Philippines” has recently been finalized in 13 languages, including 11 local languages of the Philippines and has been made available to organizations fighting a return of the death penalty. These brochures were created in collaboration with the CHR. They include the political history of capital punishment in the Philippines along with a detailed outline of reasons to keep the Philippines an abolitionist state, and a list of mobilising actions to take against its reintroduction. It is available in all 13 languages on the WCADP website now.

Photo by Mara Rivera on Unsplash.

Attached documents

Document(s)

Keep the Death Penalty Abolished in the Philippines (Bicolano)

By World Coalition Against Death Penalty, on 23 March 2021

Campaigning

Drug Offenses

Philippines

This brochure was developed by the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty with the Commission on the Human Rights in the Philippines. It explains why the death penalty risks returning in the Philippines and the reasons against its resurgence. It is available in 11 languages of the Philippines, plus French and English.

Keep the Death Penalty Abolished in the Philippines (Cebuano)

Keep the Death Penalty Abolished in the Philippines (English)

Keep the Death Penalty Abolished in the Philippines (Hiligaynon)

Keep the Death Penalty Abolished in the Philippines (Ilokano)

Keep the Death Penalty Abolished in the Philippines (Kapampangan)

Keep the Death Penalty Abolished in the Philippines (Marano)

Keep the Death Penalty Abolished in the Philippines (Pangasinense)

Keep the Death Penalty Abolished in the Philippines (Tagalog)

Keep the Death Penalty Abolished in the Philippines (Tausug)

Keep the Death Penalty Abolished in the Philippines (Waray)

Abolitionist for all crimes Death penalty legal status

21st World Day Against the Death Penalty – The death penalty: An irreversible torture

Helping the World Achieve a Moratorium on Executions

In 2007, the World Coalition made one of the most important decisions in its young history: to support the Resolution of the United Nations General Assembly for a moratorium on the use of the death penalty as a step towards universal abolition. A moratorium is temporary suspension of executions and, more rarely, of death sentences. […]

More articles

Violations of the Right to Life in the Context of Drug Policies

Congress should block effort to reintroduce death penalty in the Philippines

UN: freeze funding of Iran counter-narcotics efforts

Malaysia and the Politics Behind the Death Penalty: A Tumultuous Relationship.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

RA 9165, RA 10640 and Related Jurisprudence

COMPREHENSIVE DANGEROUS DRUGS ACT OF 2002 Implementing Rules and Regulations

Related Papers

shivangi pandey

Alex Stevens

This drug policy guide was compiled in 2009 through research and consultation with our network of experts. It aims to provide our regional and national partners with a resource that they can use to conduct reviews of the national drug policies and programmes in their areas, and engage with policy-makers to work towards policy and programme improvements. The guide will be updated annually to reflect changes in global evidence and experience.

New England Journal of Medicine

Kevin Outterson

Faiza Sefroun

Douglas Behr

International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Communication and Technology

shriniwas Mane

The field of regulatory affairs (RA) serves as a link between the global pharmaceutical sector and regulators. It was created in response to governments’ desire to safeguard the public’s health by regulating the efficacy and safety of pharmaceuticals, veterinary drugs, medical equipment, pesticides, agricultural chemicals, cosmetics, and other goods. Companies that are in charge of the development, manufacture, testing, and sale of these products aim to guarantee that they deliver safe and efficient goods for the welfare of the general public. Different registration criteria for pharmaceutical products are covered by pharmaceutical drug regulatory affairs. As a result of the demand for superior quality medicine that includes safety and efficacy in the areas of not only pharmacy but also veterinary medicine, medical devices, insecticides, pesticides, agrochemicals, cosmetic, and supplementary medicine, a new profession called pharmacy was created. Additionally, it created a connectio...

British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology

Raymond Hill

brahmaiah bonthagarala

RELATED PAPERS

TRANSACTIONS of the VŠB – Technical University of Ostrava Safety Engineering Series

Darren Delaney

The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease

Madeleine Hackney

Geophysical Research Letters

Gerbang Inovasi

Retno Rusdjijati

H.P. Meininger

Fiona Margetts

Alexander Sich

Jakir hossan

Revista de Pesquisa: Cuidado é Fundamental Online

Andréa Faustino

Environmental Chemistry Letters

Samer Fawzy

Journal of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Research

Isam Elkhidir

Genes, Chromosomes and Cancer

Karoly Szuhai

Journal of Indonesian Economy and Business

Teguh Budiarto

iJADE Conference 2011 - The Centrality of Art, Design and the Performing Arts to Education

samantha forster

John Nerbonne

Advanced Robotics

Antonio Sgorbissa

Wilmer Fuentes

ECS Meeting Abstracts

Rebeca González-Villela

Journal of the American Chemical Society

Simon Trudel

Humanisme et Entreprise

Pierre Louart

Ari Susilowati

Nadine Holdsworth

Microprocessors and Microsystems

Mirosław Chmiel

The Astrophysical Journal

Comer Duncan

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- JRSM Short Rep

- v.4(5); 2013 May

From gold-medal glory to prohibition: the early evolution of cocaine in the United Kingdom and the United States

As reported in the 2011 World Drug Report, cocaine is likely to be the most problematic drug worldwide in terms of trafficking-related violence and second only to heroin in terms of negative health consequences and drug deaths. Over a period of 60 years, cocaine evolved from the celebrated panacea of the 1860s to outlawed street drug of the 1920s. As demonstrated by the evolution of cocaine use and abuse in the United Kingdom and United States during this time period, cultural attitudes influenced both the acceptance of cocaine into the medical field and the reaction to the harmful effects of cocaine. Our review of articles on cocaine use in the United Kingdom and the United States from 1860 to 1920 reveals an attitude of caution in the United Kingdom compared with an attitude of progressivism in the United States. When the trends in medical literature are viewed in the context of the development of drug regulations, our analysis provides insight into the relationship between cultural attitudes and drug policy, supporting the premise that it is cultural and social factors which shape drug policy, rather than drug regulations changing culture.

Introduction

Cocaine is likely to be the most problematic drug worldwide in terms of trafficking-related violence and second only to heroin in terms of negative health consequences and drug deaths. 1 Our review of articles on cocaine use in the United Kingdom and the United States from 1860 to 1920 reveals significant differences in these nations’ initial responses to cocaine use and abuse, leading to subsequent efforts of legal control.

A literature search was carried out using the online databases for The Lancet , British Medical Journal , New England Journal of Medicine and the Journal of the American Medical Association . General trends and cultural attitudes present in the medical field were found by database searches using the search terms ‘cocaine’ and ‘coca’. A systematic search of the databases for The Lancet , British Medical Journal , New England Journal of Medicine and the Journal of the American Medical Association for references to the harmful effects of cocaine was done using the search terms ‘cocaine poisoning’ and ‘poisoning by cocaine’ for the years 1860–1920, inclusive. No results were found for the years 1860–1879, inclusive. Each independent article or letter found using the search terms ‘cocaine poisoning’ and ‘poisoning by cocaine’ was considered a single reference, resulting in a total of 129 independent references found in the time period of 1880–1920, with 70 references in The Lancet , 33 references in the British Medical Journal , 25 references in the New England Journal of Medicine , and 1 reference in the Journal of the American Medical Association .

Background: cocaine’s early years

Cocaine is a crystalline alkaloid derived from the leaves of the coca plant, Erythroxylum coca , which is endogenous to South America, Mexico, Indonesia and the West Indies. 2 It has been used for centuries by the natives of these countries as a general stimulant, hunger suppressant and an important part of religious rituals. Coca, known in Europe since the Spanish conquest of Peru, remained mostly uninvestigated until, in 1859, Paolo Mantegazza, a prominent Italian physician, published an influential paper on the properties of coca leaf extract. 3 , 4 At approximately the same time, Albert Niemann, a German chemist, isolated cocaine from coca leaves. He published his results in 1860, paving the way for future experimentation with the purified drug. 5

Both the United Kingdom and the United States enthusiastically embraced products containing cocaine, often used in the form of a coca leaf extract rather than purified crystals. Cocaine was seen as a miracle drug, with one 1876 article in The Lancet claiming that it ‘has been advocated by one or another in the utmost variety of cases, and were one-tenth part of what has been stated of its effects correct, it would be a panacea for all human ailments – the veritable Elixir of Life’. 6

Due to the popularity of cocaine tonics, historian Dr Howard Markel postulates that the world’s first cocaine millionaire was probably Angelo Mariani, a French chemist. Mariani combined ground coca leaves with Bordeaux in the 1860s and marketed his famous tonic wine under the name Vin Mariani. Introduced to the United States in 1863, Vin Mariani was generously prescribed by physicians across Europe and North America. Vin Mariani was used liberally by the public and the elite, including Queen Victoria, Thomas Edison, Ulysses S. Grant and Pope Leo XIII. Pope Leo XIII even awarded Vin Mariani with a Vatican gold medal. 7

Cocaine remained popular as a medicinal ingredient in a great many products; however, other than the occasional article prompting the continued exploration of coca’s properties, it nearly dropped out of the medical literature until 1884.

Local anaesthesia: cocaine’s medical miracle

It was in the spring of 1884 when Sigmund Freud, a Viennese neurologist, published his account of cocaine’s physiological effects and potential therapeutic uses in his article titled ‘Über Coca’. He included cocaine’s anaesthetizing effects in his final paragraph (considered by some historians to be more of a postscript), likely not realizing that it was cocaine’s anaesthetizing ability that would make a lasting impression in the medical field. 8 Nevertheless, Sigmund Freud’s mention of the anaesthetic properties of cocaine did not escape notice for long.

Carl Koller, an ophthalmology intern at Vienna’s general hospital, used a solution of cocaine hydrochloride for cataract surgery and met with great success. His work was first presented at the international Ophthalmological Congress in September 1884 at Heidelberg, Germany. 8 In October and November of 1884, Koller’s work was already being discussed and expanded upon. 9 , 10 It is at this point that the first major distinction between the response of the United Kingdom and the United States becomes apparent.

Two weeks before the publication of Dr Koller’s original paper in Vienna, Americans were informed of his discovery and immediately began testing cocaine in a variety of applications. Consequently, the first response from the United States regarding the use of cocaine as a local anaesthetic was six weeks earlier than the first response from their British counterparts. In addition to its use in ophthalmic surgeries, where cocaine quickly became invaluable, cocaine solutions were popular in laryngeal procedures, otology, genito-urinary surgeries, gynaecology and obstetrics. 11

Cocaine as a local anaesthetic reached widespread use by both the Americans and the British. However, in comparison to the Americans, the British proceeded more conservatively in changing their medical practices. Dr Knapp, a physician who compiled all that was written about cocaine in the first decade of its use, was the first to note that the British response was slow and guarded, while the Americans responded with a spirit of receptiveness and progressivism. 11 , 12 These responses to the use of cocaine in medical settings were suggestive of the cultural attitudes that presaged the coming differences in the response to cocaine’s toxic effects.

Cocaine poisoning: impact of UK reticence and US enthusiasm

Comments on the effects of cocaine, such as its ability to increase heart rate and cause pupil dilation, had accompanied even the earliest descriptions of its use. However, most physicians and scientists in the United States and Europe believed cocaine to be safe and non-addictive. It was not until 1887 that belief in the benign nature of cocaine was actively challenged. 13 As shown in Figure 1 , a survey of the years 1860–1920 in The Lancet , British Medical Journal , New England Journal of Medicine and the Journal of the American Medical Association for references to cocaine poisoning reveals that, when compared with the eager response by the United States and conservative response by the United Kingdom to the discovery of cocaine as an anaesthetic, there was a role reversal when understanding the potential for harm from cocaine use. The earliest mention of poisoning by cocaine occurred in The Lancet in 1880, albeit an animal study report, while it took until 1885 for similar concerns to appear in the New England Journal of Medicine . There was a peak of interest in writing up case studies and treatments for cocaine poisoning in the British medical literature in 1889. While the topic of cocaine poisoning was addressed in American medical literature, with significantly more interest shown in The New England Journal of Medicine than the Journal of the American Medical Association , there was never a dramatic peak of published articles comparable with that of the British publications. It appears as if British caution resulted in higher sensitivity to signs of danger, while American progressivism tended to dampen negative responses.

References to cocaine poisoning from 1880 to 1920 in The Lancet , the British Medical Journal , the Journal of the American Medical Association and the New England Medical Journal .

The prohibition of cocaine

By the year 1900, cocaine had gone from being the beloved ingredient of the award-winning Vin Mariani to a feared drug holding many people prisoners to addiction. In the United States, it is estimated that 5% of the population was addicted to one or more of cocaine, heroin or morphine at the turn of the 20th century, with the majority being rural, middle-class white women who had been prescribed the drugs by well-meaning physicians. 14 With medicinal use of cocaine-containing products culminating in an addiction epidemic in both the United Kingdom and the United States, and increasing numbers of case reports of cocaine poisoning during medical procedures, regulation of cocaine became an impending necessity.

The cultural attitude of caution demonstrated by the United Kingdom in their comparatively slow uptake of cocaine’s medical uses, and in their early and thorough investigation into the harmful effects of cocaine, was also evident in their process of developing legislation to control drug access. The United Kingdom’s Pharmacy Act of 1868 showed a historical willingness to not only appreciate that beneficial drugs often can have harmful effects, but to also accept the need for drug regulations to protect the public from drug abuse. 15 In comparison, American progressivism and enthusiasm had resulted in a fast-paced period of increased use of pharmaceutical agents, unaccompanied by any formal drug regulation until decades later. With the historical precedent of the Pharmacy Act of 1868 already in place in the United Kingdom, implementing new drug legislation was not nearly as difficult in the United Kingdom as it was to create similar controls de novo in the United States.

In the United Kingdom, the labelling and sale of products containing cocaine was first regulated under the Poisons and Pharmacy Act of 1908. The Defence of the Realm Act was instituted in 1916 to curb illegal possession of cocaine, prompted by concern over the possession and sale of cocaine by soldiers during the World War I. In 1920, the Dangerous Drugs Act limited the production, import, export, possession, sale or distribution of cocaine to licensed persons. After passing the Dangerous Drugs Act, cocaine use in the United Kingdom was successfully maintained at a low level for the subsequent five to six decades. 15

Restricting access to cocaine in the United States was further complicated in that healthcare fell under state instead of federal jurisdiction, meaning that a national law to control access to cocaine would require a constitutional amendment to allow federal interference in healthcare. To avoid legal conflicts, initial attempts to control cocaine use were necessarily piecemeal and indirect. 14

The first federal step towards drug control was The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. This act prohibited the sale of adulterated or mislabelled products, serving to decrease drug abuse by curtailing false advertising of drugs. However, it did not outlaw dangerous drugs, such as cocaine, nor did it even restrict the possession and sale of cocaine. 14

Success in limiting the sale of cocaine to licensed pharmacists and physicians was finally achieved with the Harrison Tax Act of 1914. Cocaine was added at the last minute by Southern legislators who promoted the post-civil war racial belief that there is a class in society that can control themselves while using alcohol or drugs, and another class that simply cannot. Southern politicians argued that cocaine was a national concern because policemen and physicians reported that cocaine abuse resulted in aggressive, sex-crazed black men who were apt to commit violent crimes and rape innocent white women. It was this carefully timed racist sentiment that forever changed the American society’s view of cocaine from boon to bane. In fact, the perception of cocaine shifted so dramatically that it was the only drug in the Harrison Tax Act which was completely restricted from inclusion in over-the-counter medications. 14 , 16

Today’s use of cocaine

With high rehabilitation costs, relatively frequent overdoses and deaths, and health complications from adulterants and polydrug use, cocaine in the 21st century is a significant burden on healthcare systems worldwide. Recent declines in American cocaine consumption, specifically noted in the population of young drug users, are encouraging. However, even after taking the recent declines into consideration, the United States remains the country with the highest overall cocaine consumption. In comparison, the annual prevalence of cocaine use in the European Union remains less than half of the annual prevalence in the United States, but is double that of a decade earlier. With two-thirds of the European Union’s cocaine users residing in the United Kingdom, Spain and Italy, the cocaine trend in the United Kingdom has been strongly heading upwards. 1

Over a period of 60 years, cocaine evolved from the celebrated panacea of the 1860s to outlawed street drug of the 1920s. As demonstrated by the evolution of cocaine use and abuse in the United Kingdom and United States during this time period, cultural attitudes influenced both the acceptance of cocaine into the medical field and the reaction to the harmful effects of cocaine. This influence is shown by publications in medical literature and in the nations’ establishment of regulatory laws.

Now, roughly 100 years after cocaine played a role in the initiation of their drug policies, both nations are facing another potential turning point. The current question is whether or not liberalizing drug laws, in attempts to reduce the amount of criminality involved in drug trafficking, will result in an unwanted increase in drug users. Recent studies by the United Kingdom Drug Policy Commission have concluded that there is little evidence from the United Kingdom, or any other country, that drug policy actually influences the number of drug users or drug dependents. The present day cocaine use trends are likely the result of changing cultural perception of cocaine, not policy. 15 Indeed, our analysis of the aetiology of drug laws in the United Kingdom and United States supports the premise that cultural and social factors shape policy, rather than that policy changes culture.

Declarations

Competing interests.

None declared

The research and publication costs will be covered by the History of Medicine Program at the University of Alberta

Contributorship

VW conceived the idea, performed the literature search, and is the main author for this manuscript. DG approved the idea, supervised the project, and contributed in the revision of the manuscript

Acknowledgements

Timothy Peters

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002, officially designated as Republic Act No. 9165, is a consolidation of Senate Bill No. 1858 and House Bill No. 4433.It was enacted and passed by the Senate of the Philippines and House of Representatives of the Philippines on May 30 and 29, 2002, respectively. It was signed into law by President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo on June 7, 2002.

Dangerous Drugs Act is a piece of legislation which prohibits and regulates the manufacture, trade, usage, and maintenance of illegal drugs in one's territory. The first United States Anti-drug law was enacted way back November 15, 1875. It was enacted in San Francisco where it banned opium smoking and opium.

AN ACT INSTITUTING THE COMPREHENSIVE DANGEROUS DRUGS ACT OF 2002, REPEALING REPUBLIC ACT NO. 6425, OTHERWISE KNOWN AS THE DANGEROUS DRUGS ACT OF 1972, AS AMENDED, PROVIDING FUNDS THEREFOR, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES. Be it enacted by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Philippines in Congress assembled. SECTION 1. Short Title.

The drug policy in the Philippines is written as the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002 or Republic Act 9165. Unlike drug policies in other countries, the law includes policies on drug testing. Aside from mandatory drug testing for specific situations, the law states further that two testing methods should be employed—a screening test ...

RA 9165 Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002. It is the policy of the State : to safeguard the integrity of its territory & the well-being of its citizenry, particularly the youth, from the harmful effects of dangerous drugs on their physical & mental well-being, and 2. to defend the same against acts or omissions detrimental to their ...

Smith et al.1 emphasized the imperative of implementing evidence-based public health programs and advancing social justice in drug rehabilitation and treatment within the Philippines. The authors also underlined the necessity of reforming the two-decades-old Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act.1 This stance is consistent with the position of local and international advocates, students ...

The dangers of the Dangerous Drugs Act. Aug 28, 2016 9:53 AM PHT. Camille Elemia. If such strict law - the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002 - was passed 14 years ago in 2002, why does ...

This Act repeals Republic Act No. 6425, otherwise known as the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1972. Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002 (Republic Act No. 9165). This Act, consisting of 101 sections, provides for importation of Dangerous Drugs and/or Controlled Precursors and Essential Chemicals. It establishes offences.

problem is embodied in R.A. 9165, more popularly known as "The Comprehensive Drugs Act of 2002." This book is the result of a quite exceptional multidisciplinary research cooperation that has ...

Ortiz, L. S. P. (2016). A content analysis of Supreme Court decisions on the acquittal and conviction of drug related cases under R.A. 9165 (otherwise known as the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002) (Unpublished postgraduate thesis).

Academia.edu is a platform for academics to share research papers. IMPLEMENTING RULES AND REGULATIONS (IRR) OF REPUBLIC ACT NO. 9165, OTHERWISE KNOWN AS THE " COMPREHENSIVE DANGEROUS DRUGS ACT OF 2002 " THESE RULES AND REGULATIONS ARE HEREBY PROMULGATED TO IMPLEMENT THE PROVISIONS OF REPUBLIC ACT NO . × ...

Essay Sample: The illegal drugs problem in the country is real and pervasive. It is undermining the moral fabric of our society and is victimizing almost everyone, ... or the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002, on June 7, 2002 and it took effect on July 4, 2002. The Republic Act No. 165 defines more concrete courses of action for the ...

Asia. Philippine House Bill No. 7814 provides the death penalty for a new crime under the 2002 Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act. Adopted on March 2nd 2021, this Bill comes after years of President Rodrigo Duterte's unflagging insistence to reintroduce the death penalty to the Philippines, despite the country having abolished the capital ...

Drugs in the United States are controlled by the 1970 Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act. This was past by Congress in the 1970's. It regulates the manufacture, the destruction as well as the possession and use of drugs. It also places all drugs into one of the five schedules that are I, II, III, IV and V.

In Criminal Case No. 04-2433, the accused Jesusa Figueroa y Coronado alias Baby is found guilty beyond reasonable doubt of the offense of violation of Sec. 26, Art. II, RA 9165 and is sentenced to suffer life imprisonment and to pay a fine of Five Hundred Thousand (P500,000.00).

danicaparra. report flag outlined. Comprehensive dangerous act, a policy and law that made the youth safe and free from harmful drugs. Come to think of it, does this law being followed? Maybe yes from some of the youth who are not interested to use drugs. The government shall implement an intensive law that can prevent the youth from using drugs.

Short Title. - This Act shall be known and cited as the "Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002". Section 2. Declaration of Policy. - It is the policy of the State to safeguard the integrity of its territory and the well-being of its citizenry particularly the youth, from the harmful effects of dangerous drugs on their physical ...

Abstract. We examine the ethical, social and regulatory barriers that may hamper research on therapeutic potential of certain controversial controlled substances like marijuana, heroin or ketamine. Hazards for individuals and society, and their potential adverse effects on communities may be good reasons for limiting access and justify careful ...

The Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002 - Free download as Powerpoint Presentation (.ppt / .pptx), PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or view presentation slides online. powerpoint presentation about the salient provisions of RA 9165

Title II of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, commonly known as the Controlled Substance Act (CSA), establishes a federal policy to regulate the manufacturing, distributing, importing/exporting, and use of regulated substances.[1] The CSA was enacted by the 91st United States Congress and signed by President Richard Nixon into law in 1970.[2]

The Dangerous Act of 1972. RA 9165. The Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002. Narcotic Drugs. Refers to any drug which produces insensibility, stupor, melancholy, or dullness of mind with delusions. opium. Refers to coagulated juice of the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) and embraces every kind and class of opium.

Terms in this set (106) REPUBLIC ACT NO. 6425. Repealed RA, Known as the Dangerous Drug Act of 1972, as amended. SEC. 2. Declaration of Policy. What section of this law can this statement be found: the government shall pursue an intensive and unrelenting campaign against the trafficking and use of dangerous drugs and other similar substances ...

The first federal step towards drug control was The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. This act prohibited the sale of adulterated or mislabelled products, serving to decrease drug abuse by curtailing false advertising of drugs. However, it did not outlaw dangerous drugs, such as cocaine, nor did it even restrict the possession and sale of cocaine. 14