- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

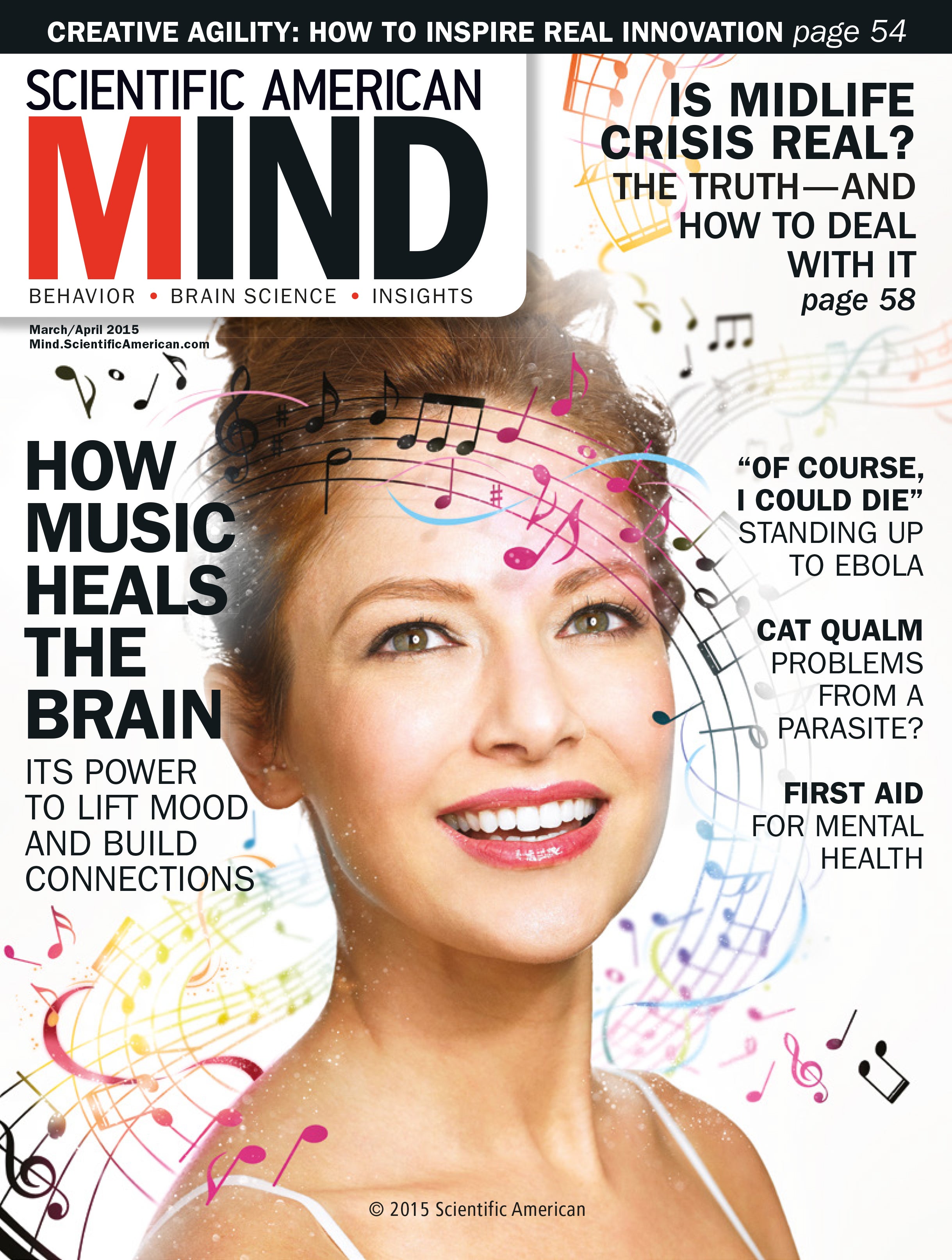

The Healing Power of Music

Music therapy is increasingly used to help patients cope with stress and promote healing.

By Richard Schiffman

“Focus on the sound of the instrument,” Andrew Rossetti, a licensed music therapist and researcher said as he strummed hypnotic chords on a Spanish-style classical guitar. “Close your eyes. Think of a place where you feel safe and comfortable.”

Music therapy was the last thing that Julia Justo, a graphic artist who immigrated to New York from Argentina, expected when she went to Mount Sinai Beth Israel Union Square Clinic for treatment for cancer in 2016. But it quickly calmed her fears about the radiation therapy she needed to go through, which was causing her severe anxiety.

“I felt the difference right away, I was much more relaxed,” she said.

Ms. Justo, who has been free of cancer for over four years, continued to visit the hospital every week before the onset of the pandemic to work with Mr. Rossetti, whose gentle guitar riffs and visualization exercises helped her deal with ongoing challenges, like getting a good night’s sleep. Nowadays they keep in touch mostly by email.

The healing power of music — lauded by philosophers from Aristotle and Pythagoras to Pete Seeger — is now being validated by medical research. It is used in targeted treatments for asthma, autism, depression and more, including brain disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy and stroke.

Live music has made its way into some surprising venues, including oncology waiting rooms to calm patients as they wait for radiation and chemotherapy. It also greets newborns in some neonatal intensive care units and comforts the dying in hospice.

While musical therapies are rarely stand-alone treatments, they are increasingly used as adjuncts to other forms of medical treatment. They help people cope with their stress and mobilize their body’s own capacity to heal.

“Patients in hospitals are always having things done to them,” Mr. Rossetti explained. “With music therapy, we are giving them resources that they can use to self-regulate, to feel grounded and calmer. We are enabling them to actively participate in their own care.”

Even in the coronavirus pandemic, Mr. Rossetti has continued to perform live music for patients. He says that he’s seen increases in acute anxiety since the onset of the pandemic, making musical interventions, if anything, even more impactful than they were before the crisis.

Mount Sinai has also recently expanded its music therapy program to include work with the medical staff, many of whom are suffering from post-traumatic stress from months of dealing with Covid, with live performances offered during their lunch hour.

It’s not just a mood booster. A growing body of research suggests that music played in a therapeutic setting has measurable medical benefits.

“Those who undergo the therapy seem to need less anxiety medicine, and sometimes surprisingly get along without it,” said Dr. Jerry T. Liu, assistant professor of radiation oncology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

A review of 400 research papers conducted by Daniel J. Levitin at McGill University in 2013 concluded that “listening to music was more effective than prescription drugs in reducing anxiety prior to surgery.”

“Music takes patients to a familiar home base within themselves. It relaxes them without side effects,” said Dr. Manjeet Chadha, the director of radiation oncology at Mount Sinai Downtown in New York.

It can also help people deal with longstanding phobias. Mr. Rossetti remembers one patient who had been pinned under concrete rubble at Ground Zero on 9/11. The woman, who years later was being treated for breast cancer, was terrified by the thermoplastic restraining device placed over her chest during radiation and which reawakened her feelings of being entrapped.

“Daily music therapy helped her to process the trauma and her huge fear of claustrophobia and successfully complete the treatment,” Mr. Rossetti recalled.

Some hospitals have introduced prerecorded programs that patients can listen to with headphones. At Mount Sinai Beth Israel, the music is generally performed live using a wide array of instruments including drums, pianos and flutes, with the performers being careful to maintain appropriate social distance.

“We modify what we play according to the patient’s breath and heart rate,” said Joanne Loewy, the founding director of the hospital’s Louis Armstrong Center for Music & Medicine. “Our goal is to anchor the person, to keep their mind connected to the body as they go through these challenging treatments.”

Dr. Loewy has pioneered techniques that use several unusual instruments like a Gato Box, which simulates the rhythms of the mother’s heartbeat, and an Ocean Disc, which mimics the whooshing sounds in the womb to help premature babies and their parents relax during their stay in noisy neonatal intensive care units.

Dr. Dave Bosanquet, a vascular surgeon at the Royal Gwent Hospital in Newport, Wales, says that music has become much more common in operating rooms in England in recent years with the spread of bluetooth speakers. Prerecorded music not only helps surgical patients relax, he says, it also helps surgeons focus on their task. He recommends classical music, which “evokes mental vigilance” and lacks distracting lyrics, but cautions that it “should only be played during low or average stress procedures” and not during complex operations, which demand a sharper focus.

Music has also been used successfully to support recovery after surgery. A study published in The Lancet in 2015 reported that music reduced postoperative pain and anxiety and lessened the need for anti-anxiety drugs. Curiously, they also found that music was effective even when patients were under general anesthesia.

None of this surprises Edie Elkan, a 75-year-old harpist who argues there are few places in the health care system that would not benefit from the addition of music. The first time she played her instrument in a hospital was for her husband when he was on life support after undergoing emergency surgery.

“The hospital said that I couldn’t go into the room with my harp, but I insisted,” she said. As she played the harp for him, his vital signs, which had been dangerously low, returned to normal. “The hospital staff swung the door open and said, ‘You need to play for everyone.’”

Ms. Elkan took these instructions to heart. After she searched for two years for a hospital that would pay for the program, the Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital in Hamilton, N.J., signed on, allowing her to set up a music school on their premises and play for patients at all stages in their hospitalization.

Ms. Elkan and her students have played for over a hundred thousand patients in 11 hospitals that have hosted them since her organization, Bedside Harp, was started in 2002.

In the months since the pandemic began, the harp players have been serenading patients at the entrance to the hospital, as well as holding special therapeutic sessions for the staff outdoors. They hope to resume playing indoors later this spring.

For some patients being greeted at the hospital door by ethereal harp music can be a shocking experience.

Recently, one woman in her mid-70s turned back questioningly to the driver when she stepped out of the van to a medley of familiar tunes like “Beauty and the Beast” and “Over the Rainbow” being played by a harpist, Susan Rosenstein. “That’s her job,” the driver responded, “to put a smile on your face.”

While Ms. Elkan says that it is hard to scientifically assess the impact — “How do you put a number on the value of someone smiling who has not smiled in six months?”— studies suggest that harp therapy helps calm stress and put both patients and hospital staff members at ease.

Ms. Elkan is quick to point out that she is not doing music therapy, whose practitioners need to complete a five-year course of study during which they are trained in psychology and aspects of medicine.

“Music therapists have specific clinical objectives,” she said. “We work intuitively — there’s no goal but to calm, soothe and give people hope.”

“When we come onto a unit, we remind people to exhale,” Ms. Elkan said. “Everyone is kind of holding their breath, especially in the E.R. and the I.C.U. When we come in, we dial down the stress level several decibels.”

Ms. Elkan’s harp can do more than just soothe emotions, says Ted Taylor, who directs pastoral care at the hospital. It can offer spiritual comfort to people who are at a uniquely vulnerable moment in their lives.

“There is something mysterious that we can’t quantify,” Mr. Taylor, a Quaker, said. “I call it soul medicine. Her harp can touch that deep place that connects all of us as human beings.”

How Music Helps People Heal: The Therapeutic Power of Music

Music is a universal language that transcends cultural, geographical, and linguistic boundaries. It has been an integral part of human culture for centuries, providing joy, solace, and a means of self-expression. But music’s impact goes far beyond mere entertainment; it possesses a remarkable therapeutic power that can help people heal in profound ways. In this article, we will explore the therapeutic benefits of music and how it can contribute to physical, emotional, and mental well-being.

The Science Behind Music Therapy

Music therapy is a well-established field that uses the power of music to address a variety of physical, emotional, and cognitive needs. It is based on the understanding that music can affect the brain and body in unique ways, triggering emotional and physiological responses that are beneficial for healing. Here are some key ways in which music therapy can have a positive impact:

- Stress Reduction: Listening to soothing music can trigger the release of stress-reducing hormones like serotonin and oxytocin. This can help lower blood pressure, reduce anxiety, and create an overall sense of relaxation.

- Pain Management: Music has the ability to distract people from physical pain by redirecting their focus. For patients undergoing medical procedures or suffering from chronic pain, music therapy can be a valuable tool in managing discomfort.

- Emotional Expression: Music provides a safe outlet for the expression of emotions. Composing or playing music allows individuals to convey their feelings when words alone may not suffice.

- Cognitive Benefits: For individuals with cognitive impairments, music therapy can stimulate memory and improve cognitive functions. It can also enhance speech and language skills.

The Power of Rhythm and Melody

Rhythm and melody are the fundamental building blocks of music that contribute to its therapeutic potential. Here’s how they play a role in healing:

- Rhythm: The steady beat of music can regulate heart rate and breathing, helping to create a sense of stability and control. Rhythmic patterns can also be used to improve motor skills in individuals with physical disabilities.

- Melody: Melodic elements, like harmonies and melodies, can evoke specific emotions and provide comfort. For example, a soothing lullaby can ease a troubled mind, while an upbeat song can boost one’s mood and motivation.

Music and Mental Health

The therapeutic effects of music are particularly pronounced in the realm of mental health. Music can be a powerful tool for managing conditions like depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Here are some ways in which it can help:

- Emotional Regulation: Music can help individuals identify and process their emotions. It offers a safe space to express feelings, which is especially beneficial for those who have difficulty verbalizing their emotions.

- Distraction from Negative Thoughts: Engaging with music can divert attention away from obsessive or distressing thoughts, reducing the intensity of anxiety or depression.

- Self-Expression: Creating music, whether through singing, playing an instrument, or composing, allows individuals to express themselves authentically, providing a sense of empowerment and self-worth.

Music Therapy in Practice

Music therapy is employed in a variety of settings, including hospitals, mental health clinics, schools, and rehabilitation centers. Certified music therapists work with individuals of all ages and backgrounds, customizing treatment plans to address specific needs and goals. Sessions may involve listening to music, playing instruments, songwriting, or even group activities.

The therapeutic power of music is a force to be reckoned with, offering healing and support for physical, emotional, and mental well-being. Whether you’re struggling with stress, physical pain, or mental health challenges, incorporating music into your life can be a beneficial addition to your healing journey. From the soothing melodies that calm the mind to the rhythmic beats that steady the heart, music is a universal balm that transcends words and offers solace to the human soul. So, the next time you find yourself in need of healing, don’t forget to turn to the therapeutic power of music.

Share This Post

Face the music with us.

Many never seek treatment for addiction because of the cost. Face the Music Foundation is looking to help as many people as possible take the financial worry out of addiction treatment so they don’t have to choose between their savings and their sobriety. We need your help to get it done.

UW Health recently identified and investigated a security incident regarding select patients’ information. Learn more

- Find a Doctor

- Conditions & Services

- Locations & Clinics

- Patients & Families

- Refer a Patient

- Refill a prescription

- Price transparency

- Obtain medical records

- Clinical Trials

- Order flowers and gifts

- Volunteering

- Send a greeting card

- Make a donation

- Find a class or support group

- Priority OrthoCare

- Emergency & Urgent care

May 22, 2019

The healing power of music

Madison, Wis. — It’s been called many things – the universal language, a great healer, even a reflection of the divine. While there’s little doubt about the power of music, research now shows us just how powerful it can be.

“Across the history of time, music has been used in all cultures for healing and medicine,” said health psychologist Shilagh Mirgain , PhD. “Every culture has found the importance of creating and listening to music. Even Hippocrates believed music was deeply intertwined with the medical arts.”

Scientific evidence suggests that music can have a profound effect on individuals – from helping improve the recovery of motor and cognitive function in stroke patients, reducing symptoms of depression in patients suffering from dementia, even helping patients undergoing surgery to experience less pain and heal faster. And, of course, it can be therapeutic.

“Music therapy is an established form of therapy to help individuals address physical, emotional, cognitive and social needs,” said Mirgain. “Music helps reduce heart rate, lower blood pressure and cortisol in the body. It eases anxiety and can help improve mood."

Music is often in the background just about anywhere we go – whether at a restaurant or the store. But Mirgain offers some tips to help use music intentionally to relax, ease stress and even boost moods:

Be aware of the sound environment

Some restaurants use music as a way of subtly encouraging people to eat faster so there is greater turnover. If you’re looking for a location to have a meeting, or even a personal discussion that could be stressful, keep in mind that noisy environments featuring lively music can actually increase stress and tension.

Use it to boost your energy

On the other hand, when you need energy levels to be up – like when exercising, cleaning or even giving a presentation – upbeat music can give you the lift you need. Consider using music when you’re getting ready in the morning as a way to get your day off on the right beat.

Improve sleep

Listening to classical or relaxing music an hour before bedtime can help create a sense of relaxation and lead to improved sleep.

Calm road rage

Listening to music you enjoy can help you feel less frustrated with traffic and could even make you a safer driver.

Improve your mental game

Playing an instrument can actually help your brain function better. Faster reaction times, better long-term memory, even improved alertness are just a few of the ways playing music can help. Studies have also shown that children who learn to play music do better at math and have improved language skills.

Reduce medical anxiety

Feeling stressed about an upcoming medical procedure? Consider using music to calm those jitters. Put your ear buds in and listening to your favorite tunes while sitting in the waiting room can ease anticipatory anxiety before a medical procedure, such as a dental procedure, MRI or injection. Ask your health care provider if music is available to be played in the room during certain procedures, like a colonoscopy, mammogram or even a cavity filling. Using music in these situations distracts your mind, provides a positive experience and can improve your medical outcome.

The healing power of music

Sign up for the On Point newsletter here .

Many of us turn to music to feel better. But music can also help us physically heal.

Studies show music can affect our blood pressure and our heart rate – and even help us manage pain.

Today, On Point : Music’s power to heal not only your soul, but your body, as well.

Psyche Loui , associate professor of creativity and creative practice at Northeastern University. Director of the Music, Imaging, and Neural Dynamics Laboratory (MIND Lab). ( @psycheloui )

Pier Lambiase , professor of cardiology at University College London and Barts Heart Centre. ( @LambiasePier )

Also Featured

Suzanne Hanser , chair emerita and professor of music therapy at Berklee College of Music. ( @suzannehanser )

Transcript: The healing power of music

SUZANNE HANSER: At the first treatment, I would bring all of the instruments I could carry. So, I had a Native American flute.

I had a ukulele.

I had hand chimes that create a very resonant sound in this very bright steel glass environment in the chemotherapy unit.

CHAKRABARTI: The chemo unit is at the Center for Integrative Therapies at Boston’s Dana-Farber-Cancer Institute. The patients Suzanne Hanser was working with had metastatic breast cancer.

HANSER: And I would just improvise on some of these instruments and say, we’re just going to try some music and just let me know if you like it, if you want more, if we should try something else.

And then I would just suggest sometimes that they just breathe with the music or suggest that they just imagine being in a beautiful, comforting place.

CHAKRABARTI: Suzanne is a professor of music therapy at Berklee College of Music. The women had agreed to work with her on research investigating the effects of how music changes a cancer patient’s psychological and physiological responses to treatment.

HANSER: And in the second session we would start with what they really appreciated from the first session and at the opportunity to improvise with me.

So I had a rain stick, something very simple to play. But when you close their eyes, it often transports you to a rain forest or a waterfall or some place in nature.

In the final session, we did some of that and also provided an opportunity for each woman to write a song. And I remember one woman saying, well, there’s just no way I could write music. And I said, Well, perhaps there’s something important you want to say to someone, someone that you love, someone who’s cared for you. And she said, Oh, I don’t know. I don’t really think of anything I’d like to say right now.

And I said, Well, how about writing a song to someone? Is there someone in your life that you like to write a song for? She said, No, I don’t really think so. And then I said, perhaps you’d like to write a song about our experience. You seem to have enjoyed our music therapy sessions. And she just started singing. The music is here. The dancing is here. Back and forth we go. The music will help me. The music can aid me. I think it really will help. It is here when I need it. It is here when I want it. The music will be right for me.

Who would have thought? Some of the women participating in our study said, I never thought chemotherapy would be fun, but, you know, in these sessions they were providing a really beautiful atmosphere for processing what they were going through.

There’s a lot of research out there that speaks to the many physiological changes that happen during a music therapy session: decreased heart rate, decreased blood pressure, their perception of pain. Individuals who had chronic pain, they didn’t necessarily have their pain go away.

But several reflected on how that process, where they were listening to very meaningful music changed. Well, the way that they experienced pain for one person. He said that the throbbing nature of his pain improved, and it became less noticeable. The importance of that is not that perhaps music can relieve pain.

But if a person sees that they can manage the pain, that the pain they thought was constant can actually change while they’re engaged with music, then they know that they can somehow take control of this pain.

Everyone can probably find a piece of music that they love being able to listen to that piece of music. When we’re in a crowded, noisy environment or we’re in a physician’s waiting room, wherever we might be, we can use music to change our mood.

We have music on our playlist that we love. We have music that is constantly changing the way we feel. So, reflecting on how music affects you will teach you about the music that you might want to play when you’re feeling really agitated, or the music that you might need when you’re feeling really lonely or depressed.

A musical experience that engages someone, that makes them dance. That makes them think. That makes them remember. That helps them go back to a wonderful opportunity to live life to its fullest.

Related Reading

Scientific American : “ How Music Can Literally Heal the Heart ” — “In a maverick method, nephrologist Michael Field taught medical students to decipher different heart murmurs through their stethoscopes, trills, grace notes, and decrescendos to describe the distinctive sounds of heart valves snapping closed, and blood ebbing through leaky valves in plumbing disorders of the heart.”

This article was originally published on WBUR.org.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

The healing power of music

- entertainment

Deep English

Thank you for supporting us!

The Healing Power Of Music

People are enamored with music. It touches our souls in profound ways that words alone cannot equal. It stirs our imagination , invigorates our bodies, and transforms our moods. It can lift us up or overwhelm us with emotion. It can make us feel down in the dumps or over the moon . It can pump us up , and it can calm us down.

Billy Joel, the famous American songwriter and performer, once said. “I think music in itself is healing. It’s an explosive expression of humanity. It’s something we are all touched by. No matter what culture we’re from, everyone loves music.”

There is no doubt: music can indeed heal. People with brain injuries such as a stroke, for example, have had success with music therapy. It can activate their brain in alternative ways. It often bypasses the damaged areas, allowing people to regain movement or speech. In this way, music actually changes the structure of the brain. It gives people new chances to move and speak.

Also, studies have shown that music therapy can lower the stress hormone cortisol. It can also increase the pleasure hormone dopamine. It can improve heart and breathing rates, as well as anxiety and pain in cancer patients. In the field of psychology, music has been used to help people suffering from depression and sadness. Also, for children with developmental disabilities, music can be healing.

Therapist Yvonne Russell has seen firsthand the power of music to heal the elderly. Henry, an old man, was living in a nursing home. Like some people his age, Henry was suffering from dementia. He forgot things easily and has lost many of his mental abilities. In fact, Henry lived in his own world , often unresponsive to other people. But when Yvonne gave him an iPod with his favorite blasts from the past , he instantly began to sing and sway to the music. His lifeless face became transformed with energy. His eyes came alive with emotion as he listened to music. While he was mostly mute for years, after listening to music he was suddenly able to shoot the breeze with the people around him. Music breathed life into his body and mind. According to Neurologist Dr. Oliver Sacks, “Henry is restored to himself. He has remembered who he is and has reacquired his identity for a while through the power of music.”

References: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_therapy https://psychcentral.com/lib/music-therapy-may-aid-brain-damaged-patients/

People love music. It touches us in deep ways that words alone cannot. It stirs our imagination , makes our bodies move, and can change our moods. Music can lift us up or overwhelm us with emotion. It can make us feel down in the dumps or over the moon . It can pump us up , and it can calm us down.

Billy Joel once said, “I think music in itself is healing.” The famous singer believes it’s something we are all touched by. “Everyone loves music.”

There is no doubt that music can indeed heal. People with brain damage, for example, have had success with music. It can activate their brains in different ways. It often allows people to regain movement or speech. In this way, music actually changes the brain. It gives people new chances to move and speak.

Studies have shown that music can lower stress and increase pleasure. It can improve heart and breathing rates, as well as anxiety and pain. Music has also helped people suffering from depression and sadness. Also, for children with health problems, music can be healing.

Music also has the power to heal the elderly. Henry, an old man, was living in a nursing home. Like some people his age, Henry was suffering from dementia. He forgot things and has lost many of his mental abilities. In fact, Henry lived in his own world , often unable to talk with other people. But when given an iPod with his favorite blasts from the past , he began to sing and move to the music. His face became filled with energy. His eyes came alive with emotion as he listened to music. Henry was quiet for years. But after listening to music, he was able to shoot the breeze with the people around him. Music breathed life into his body and mind. According to Dr. Oliver Sacks, Henry has remembered who he is. He has found his identity through the power of music.

Fast Fluency Formula

Join the Fast Fluency Formula to use our Speak-Out-Loud AI Chatbot for English speaking practice. Click here to get our 14-Day Free Trial.

- CONVERSATION QUESTIONS

- GENERAL CONVERSATION

How To Practice Your English With Our AI Chatbot

(Tired of typing? Don’t limit yourself to just reading and writing practice. Get full access to our speak-out-loud English conversation chatbot inside the Fast Fluency Formula.)

Get Our Free 7 Day Course Now

Improve Your English Speaking Fluency

Enter your name and email to get started, join us on facebook.

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

This website uses Google Analytics to collect anonymous information such as the number of visitors to the site, and the most popular pages.

Keeping this cookie enabled helps us to improve our website.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!

This website uses the following additional cookies:

Advertising Cookies

March 1, 2015

12 min read

Music Can Heal the Brain

New therapies are using rhythm, beat and melody to help patients recover language, hearing, motion and emotion

By William Forde Thompson & Gottfried Schlaug

One day when Laurel was 11, she began to feel dizzy while playing with her twin sister and some friends in a park on Cape Cod. She sat down, and one of her friends asked her if she was okay. And then Laurel's memory went blank. A sudden blockage in a key blood vessel leading to the brain had caused a massive stroke. Blood could no longer reach regions crucial for language and communication, resulting in permanent damage. Laurel was still able to understand language, but she struggled to vocalize even a single word, and what she managed to say was often garbled or not what she had intended. Except when she sang .

Through a type of treatment called melodic intonation therapy, Laurel learned to draw on undamaged brain regions that moderate the rhythmic and tonal aspects of language, bypassing the speech pathways on the left side of her brain that were destroyed. In other words, she found her way back to language through music.

The therapeutic program that helped Laurel—like the others we focus on in our work as scientists and clinicians—is one of a new class of music-based treatments based directly on the biology of neurological impairment and recovery. These treatments aim to restore functions lost to injury or neurological disorders by enlisting healthy areas of the brain and sometimes even by reviving dysfunctional circuitry. As evidence accumulates about the effectiveness of these techniques, clinicians and therapists from a variety of fields have begun to incorporate them into their practices, most notably music therapists, who are at the intersection of music and health and important mediators of these interventions, as well as speech therapists and physical therapists. And among the beneficiaries are people diagnosed with stroke, autism, tinnitus, Parkinson's disease and dementia.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

As scientists learn more about the effect of music on cognitive and motor functions and mental states, they can tailor these therapies for each disorder, targeting specific brain injuries or dysfunctions. In Laurel's case, the treatments were designed to trigger, over time, the development of alternative neural pathways in healthy parts of the brain that would compensate for the lost pathways in the damaged language centers. But the ultimate aim was to help her recapture as much as she could of the world that had collapsed around her that day in the park.

Music as medicine

Across cultures and throughout history, music listening and music making have played a role in treating disorders of the mind and body. Egyptian frescoes from the fourth millennium b.c. appear to depict the use of music to enhance fertility in women. Shamans in the highland tropical forests of Peru use chanting as their primary tool for healing, and the Ashanti people of Ghana accompany healing ceremonies with drumming.

Much of the power of music-based treatment lies in its ability to meld numerous subtle benefits in a single, engaging package. Music is perhaps unrivaled by any other form of human expression in the range of its defining characteristics, from its melody and rhythm to its emotional and social nature. The treatments that take advantage of these attributes are rewarding, motivating, accessible and inexpensive, and basically free of side effects, too. The attractive quality of music also encourages patients to continue therapy over many weeks and months, improving the chance of lasting gains.

The view that music can be useful in treating neurological impairment gained some scientific heft in a landmark study published in 2008. Psychologist Teppo Särkämö of the University of Helsinki and his team recruited 60 patients who had suffered a stroke in the middle cerebral artery of one hemisphere. They split the patients into three groups: the first participated in daily sessions of music listening, the second listened to audiobooks every day and the third received no auditory treatment. Researchers observed the patients over two months. Those in the group that listened to music exhibited the greatest recovery in verbal memory and attention. And because listening to music appears to improve memory, the hope now is that active music making—singing, moving and synchronizing to a beat—might help restore additional skills, including speech and motor functions in stroke patients.

The singing cure

The variety of music-based treatment that Laurel received springs from a remarkable observation about people who have had a stroke. When a stroke affects areas of the brain that control speech, it can leave patients with a condition known as nonfluent aphasia, or an inability to speak fluently. And yet, as therapists over the years have noted, people with nonfluent aphasia can sometimes sing words they cannot otherwise say.

In the 1970s neurologist Martin Albert and speech pathologists Robert Sparks and Nancy Helm (now Helm-Estabrooks), then at a Veterans Administration hospital in Boston, recognized the therapeutic implications of this ability and developed a treatment called melodic intonation therapy in which singing is a central element. During a typical session, patients will sing words and short phrases set to a simple melody while tapping out each syllable with their left hand. The melody usually involves two notes, perhaps separated by a minor third (such as the first two notes of “Greensleeves”). For example, patients might sing the phrase “How are you?” in a simple up-and-down pattern, with the stressed syllable (“are”) assigned a higher pitch than the others. As the treatment progresses, the phrases get longer and the frequency of the vocalizations increases, perhaps from one syllable per second to two.

Each element of the treatment contributes to fluency by recruiting undamaged areas of the brain. The slow changes in the pitch of the voice engage areas associated with perception in the right hemisphere, which integrates sensory information over a longer interval than the left hemisphere does; as a consequence, it is particularly sensitive to slowly modulated sounds. The rhythmic tapping with the left hand, in turn, invokes a network in the right hemisphere that controls movements associated with the vocal apparatus. Benefits are often evident after even a single treatment session. But when performed intensively over months, melodic intonation therapy also produces long-term gains that appear to arise from changes in neural circuitry—the creation of alternative pathways or the strengthening of rudimentary ones in the brain. In effect, for patients with severe aphasia, singing trains structures and connections in the brain's right hemisphere to assume permanent responsibility for a task usually handled mostly by the left.

This theory has gained support in the past two decades from studies of stroke patients with nonfluent aphasia conducted by researchers around the world. In a study published in September 2014 by one of us (Schlaug) and his group at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, 11 patients received melodic intonation therapy; nine received no treatment. The patients who received therapy were able to string together more than twice as many appropriate words per minute in response to a question. That same group also showed structural changes, assessed through MRI, in a right-hemisphere network associated with vocalization. The laboratory is now conducting studies to compare the benefits of melodic intonation therapy with other forms of therapy for patients with aphasia.

Because melodic intonation therapy seemed to work by engaging the right hemisphere, researchers then surmised that electrical or magnetic stimulation of the region might boost the therapy's power. In two recent studies that we conducted with our collaborators—one in 2011 at Beth Israel Deaconess and Harvard and the other in 2014 at the ARC Center of Excellence in Cognition and Its Disorders in Sydney, Australia—researchers stimulated an area in the right hemisphere called the inferior frontal gyrus, which helps to connect sounds with the oral, facial and vocal movements that produce them. For many participants, combining melodic intonation therapy with noninvasive brain stimulation yielded improvements in speech fluency after only a few sessions.

The benefits of melodic intonation therapy were dramatic for Laurel (who was part of a study led by Schlaug). The stroke had destroyed much of her left hemisphere, including a region crucial for language production known as Broca's area. When she began therapy in 2008, she could not string together more than two or three words, and her speech was often ungrammatical, leaving her frustrated whenever she tried to communicate. Her treatment plan was intensive—an hour and a half a day for up to five days a week, with 75 sessions in all. By the end of the 15-week treatment period, she could speak in sentences of five to eight words, sometimes more. Over the next several years she treated herself at home using the techniques she learned during the sessions. Today, eight years after her stroke, Laurel spends some of her time as a motivational speaker, giving hope and support to fellow stroke survivors. Her speech is not quite perfect but remarkable nonetheless for someone whose stroke damaged so much of her left brain. Evaluation of the long-term benefits of combination therapy is next on researchers' agenda.

Music and motion

Music making can also help stroke survivors living with impaired motor skills. In a study published in 2007 neuropsychologist and music educator Sabine Schneider and neurologist Eckard Altenmueller, both then at the Hannover University of Music, Drama and Media in Germany, asked patients to use their movement-impaired hand to play melodies on the piano or tap out a rhythm on pitch-producing drum pads. Patients who engaged in this intervention, called music-supported training, showed greater improvement in the timing, precision and smoothness of fine motor skills than did patients who relied on conventional therapy. The researchers postulated that the gains resulted from an increase in connections between neurons of the sensorimotor and auditory regions.

Rhythm is the key to treatment of people with Parkinson's, which affects roughly one in 100 older than 60. Parkinson's arises from degeneration of cells in the midbrain that feed dopamine to the basal ganglia, an area involved in the initiation and smoothness of movements. The dopamine shortage in the region results in motor problems ranging from tremors and stiffness to difficulties in timing the movements associated with walking, facial expressions and speech.

Music with a strong beat can allay some of these symptoms by providing an audible rhythmic sequence that people can use to initiate and time their movements. Treatments include so-called rhythmic entrainment, which involves playing a stimulus like a metronome. In neurologist Oliver Sacks's 1973 book Awakenings , musical rhythm sometimes released individuals from their immobility, letting them dance or sing out unexpectedly.

The use of rhythm in motor therapy gained momentum in the 1990s, when musician, music therapist and neuroscientist Michael Thaut of Colorado State University and other researchers around the world demonstrated a technique called rhythmic auditory stimulation, or RAS, for people who had trouble walking, such as stroke and Parkinson's patients. A therapist will first ask patients to walk at a comfortable speed and then to an audible rhythm. Tempos that pushed patients slightly past their comfort zone yielded the greatest improvementsin velocity, cadence and stride length.

Despite these encouraging outcomes, the neural mechanisms that trigger improvements have been difficult to pin down. Imaging work suggests that during rhythmic auditory stimulation, neural control of motor behavior is rerouted around the basal ganglia; instead the brain stem serves as a relay station that sends auditory input to motor networks in the cerebellum, which governs coordination, and to other cortical regions that could help synchronize sound and motion.

Recovered memory

Fewer neurological disorders inspire greater fear than dementia, one of the most common diseases of the elderly. According to some estimates, 44 million people worldwide are living with dementia, a number expectedto reach 135 million by 2050. Alzheimer's disease, a neurodegenerative condition, accounts for more than 60 percent of the cases; multiple strokes can also cause so-called vascular dementia.

Music may be ideally suited to stimulating memory in people with dementia, helping them maintain a sense of self. Because music activates neural areas and pathways in several parts of the brain, the odds are greater that memories associated with music will survive disease. Music also stimulates normal emotional responses even in the face of general cognitive decline. In a 2009 study psychologist Lise Gagnon of the University of Sherbrooke in Quebec and her colleagues asked 12 individuals with Alzheimer's and 12 without it to judge the emotional connotations of various pieces of music. The Alzheimer's participants were just as accurate as the others despite significant impairments in different areas of judgment. Other research suggests that taking part in musical activities throughout life keeps the mind young and may even decrease the risk of developing dementia [see “ Everyone Can Gain from Making Music ”]; the continuous engagement of the parts of the brain that integrate senses and motion with the systems for emotions and rewards might prevent loss of neurons and synapses.

The type of therapy that individual dementia patients receive will vary, from receptive (listening) to active (dancing, singing, clapping). Music that the patient selects is most effective because the choice represents a connection to memory and self. The benefits vary, too, and tend to be short-term. But when the treatment does work, it reduces the feelings of agitation that lead to wandering and vocal outbursts and encourages cooperation and interaction with others. Music therapy can also help patients with dementia sleep better and can enhance their emotional well-being.

These emotional and social benefits are clear in the case of June, an 89-year-old woman from New Hampshire. June has severe, irreversible dementia and is cared for at home by her daughter (who described her mother's circumstances to a clinician in Thompson's lab). Throughout the day, June is mainly nonresponsive and sits with her head hanging low. She cannot talk or walk, and she is incontinent. Yet when her daughter sings to her, June comes alive. She bangs her hands on her legs, smiles widely and begins to laugh. June especially loves Christmas songs and may even blurt out a word or two. When listening to music, she can bang her leg in time with the beat.

Music on the spectrum

Perhaps the most fascinating interplay between music and the brain lies in the case files of people with autism spectrum disorder, a neurodevelopmental syndrome that occurs in 1 to 2 percent of children, most of whom are boys. Hallmarks of autism include impaired social interactions, repetitive behaviors and difficulties in communication. Indeed, up to 30 percent of people with autism cannot make the sounds of speech at all; many have limited vocabulary of any kind, including gesture.

One of the peculiarities of the neurobiology of autism is the overdevelopment of short-range brain connections. As an apparent consequence, children with autism tend to focus intensely on the fine details of sensory experience, such as the varying textures of different fabrics or the precise sound qualities emitted by appliances such as a refrigerator or an air conditioner. And this fascination with sound may account for the many anecdotal reports of children with autism who thoroughly enjoy making and learning music. A disproportionate number of children with autism spectrum disorder are musical savants, with extraordinary abilities in specialized areas, such as absolute pitch.

The positive response to music opens the way to treatments that can help children with autism engage in activities with other people, acquiring social, language and motor skills as they do. Music also activates areas of the brain that relate to social ways of thinking. When we listen to music, we often get a sense of the emotional states of the people who created it and those who are playing it. By encouraging children with autism to imagine these emotions, therapists can help them learn to think about other people and what they might be feeling.

Recently the Music and Neuroimaging Laboratory at Beth Israel Deaconess and Harvard (which Schlaug directs) developed a new technique called auditory-motor mapping training, or AMMT, for children whose autism has left them unable to speak. The treatments have two main components: intonation of words and phrases (changing the melodic pitch of one's voice) and tapping alternately with each hand on pitch-producing drums while singing or speaking words and phrases. In a proof-of-principle study, six completely nonverbal children took part in 40 sessions of this training over eight weeks. By the end, all were able to produce some speech sounds, and some were even able to voice meaningful and appropriate words during tasks that the therapy sessions had not covered. Most important, the children were still able to demonstrate their new skills eight weeks after the training sessions ended.

Quiet, please

Music-based treatments can also train the brain to tune out the phantom strains of tinnitus—the experience of noise or ringing in the ear in the absence of sound that affects roughly 20 percent of adults. Age-related hearing loss, exposure to loud sounds and circulatory system disorders can all bring on the condition, with symptoms ranging from buzzing or hissing in the ears to a continuous tone with a definable pitch. The sensation can cause serious distress and interfere with the ability to concentrate on other sounds and activities. There is no cure.

The past decade has seen a surge in understanding of the neurological basis of the disorder. In one view, cochlear damage (most likely caused by exposure to loud sounds) reduces the transmission of particular sound frequencies to the brain. To compensate for the loss, neuronal activity in the central auditory system changes, creating neural “noise,” perhaps by throwing off the balance between inhibition and excitation in the auditory cortex, leading to the perception of sounds that are not there. Also at play might be dysfunctional feedback to auditory brain regions from the limbic system, which is thought to serve as a noise-cancellation apparatus that identifies and inhibits irrelevant signals.

Music treatment seeks to counteract this dysfunction by inducing changes in the neural circuitry. For those with tonal tinnitus, one treatment involves listening to “notched music,” generated by digitally removing the frequency band that matches the tinnitus frequency. The notching—pioneered and proved effective by neurophysiologist Christo Pantev and his group at the University of Münster in Germany—might help reverse the imbalance in the auditory cortex, strenghtening the inhibition of the frequency band that might be the source of the phantom sound in the first place. Another approach involves playing a series of pitches to patients and then asking them to imitate the sequence vocally. As the patients refine their accuracy, they learn to disregard irrelevant auditory signals and focus on what they want to hear. In time, the stimulus of effortful attention might help the auditory cortex return to its normal physiological state.

For any novel therapy, enthusiasm can sometimes outpace the evidence, and researchers have rightly pointed out that the new music-based treatments must prove their efficacy against the more established therapies. But of all the techniques for addressing neurological disorders, music-based therapies seem unique in their capacity to tap into emotions, to help the brain find lost memories, to let patients resume their place in the world. We are only now beginning to understand the science behind the belief in the power of music to heal.

William Forde Thompson is a professor of psychology at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, and a chief investigator at the ARC Center of Excellence in Cognition and Its Disorders there.

Gottfried Schlaug is an associate professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and is a leading researcher on plasticity in brain disorders and music-based treatments for neurological impairments.

Gareth Malone’s Easter Passion, BBC One, review: a fitting testament to the healing power of music

D on’t worry, Gareth Malone’s Easter Passion (BBC One) wasn’t a programme about the choirmaster’s love of hot cross buns or penchant for Lindt chocolate bunnies . BBC commissioners haven’t stooped that low. Not yet, anyway. Instead it was a welcome reminder of the true meaning of Holy Week.

On the 300th anniversary of its debut performance, this three-part documentary found musical maestro Malone staging Bach’s St John Passion at Cardiff’s Hoddinott Hall with the help of untrained amateur singers. It was patchy and ponderous TV but ultimately transcendent.

TV loves a challenge and a deadline, yet the jeopardy often felt false. “I have just eight weeks to get them ready for the concert,” said Malone. Why, though? This was never made clear. It might have been the biggest task of the host’s career, as he kept reminding us, but it didn’t need to be. “I wish I had six months,” he sighed. To which a reasonable response was, “Well, you should have started earlier.”

Such contrivances aside, though, this was an engaging and enlightening journey. It was a rare foray into classical conducting for Malone, best known for schoolboy and military choirs. He seemed almost as nervous as his new recruits. However, as a lifelong fan of Johann Sebastian Bach, his evangelical enthusiasm was infectious.

The opening episode saw Malone encouraging people from all walks of life to apply, before hand-picking his final eight. What stood out was the human stories. Hopefuls courageously opened up about their own struggles which might allow them to connect to the 1724 oratorio. Bristolian civil servant Astrid spoke movingly about nearly dying from preeclampsia during childbirth. Psychotherapist Joy discussed being rejected by her birth mother and then, due to her sexuality, by the church.

Port Talbot drag queen Jake had severe sight impairment (hence his drag name, Venetia Blind) and struggled to follow the score. During rehearsals, asthmatic retiree Simon lost his niece in a road accident, but was determined to sing through his grief. Over an intense practice period, Malone worked his customary magic.

Finally came the concert itself. Malone decided it should be in English, not German, in the hope this would bring Bach’s brilliance to a new audience. Alongside the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, the BBC Singers (rightly rescued from defunding) and three world-class soloists, the novices acquitted themselves magnificently. The mighty musical interpretation of the Crucifixion story built to a potent communal climax.

As Malone said, Bach’s masterpiece has endured because humanity hasn’t changed. Its themes – betrayal, suffering, loss, love, hope – remain relevant. The experience proved transformative for those involved, paying testament to the healing power of music. Putting a long-form choral concert at the heart of the Easter schedules was to be applauded as loudly as that final ovation.

Sign up to the Front Page newsletter for free: Your essential guide to the day's agenda from The Telegraph - direct to your inbox seven days a week.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

250 Words Essay on Music Has the Power to Heal The Healing Power of Music. Music, an art form that transcends boundaries and cultures, has a profound influence on our emotions and body. It is an omnipresent force, often overlooked for its therapeutic potential. The healing power of music is a topic of increasing interest within the scientific ...

These being: " (1) It is universal…, (2) It reveals itself early in life…, (3) It should exist in other animals…, (4) We might expect the brain to have specialized areas for music" (Bennet, 278). The above factors suggest that the brain is able to process, react, and change due to different collections of music.

The healing power of music — lauded by philosophers from Aristotle and ... A review of 400 research papers conducted by Daniel J. Levitin at McGill University in 2013 concluded that ...

Research suggests music lowers levels of the "stress hormone" cortisol. Another study conducted in 2013 found that not only did listening to music help reduce pain and anxiety for children at ...

Music therapy, or just listening to music, can be good for the heart. November 2009 Reviewed and updated March 25, 2015 Music can make you laugh or cry, rile you up or calm you down. Some say it's good for the soul. It just might be good for the heart, too. Make no mistake—daily doses of Mozart won't clean

National Research. Johns Hopkins is far from alone in researching the therapeutic effects of music. The Sound Health Network, a partnership of the National Endowment of the Arts with the University of California San Francisco, which was awarded $20 million over five years in 2019 by the National Institutes of Health, also supports research and promotes public awareness of the impact of music ...

It can also enhance speech and language skills. Rhythm and melody are the fundamental building blocks of music that contribute to its therapeutic potential. Here's how they play a role in healing: Rhythm: The steady beat of music can regulate heart rate and breathing, helping to create a sense of stability and control.

Healing Power Of Music Essay. Better Essays. 1863 Words. 8 Pages. Open Document. The Healing Power Of Music Music has survived throughout the course of human history because it has always been such a huge part of the human life. Music allows us to feel joy, sadness and fear. It can bring us pleasure, express what we cannot express in words.

And, of course, it can be therapeutic. "Music therapy is an established form of therapy to help individuals address physical, emotional, cognitive and social needs," said Mirgain. "Music helps reduce heart rate, lower blood pressure and cortisol in the body. It eases anxiety and can help improve mood." Music is often in the background ...

The healing power of music. Published December 23, 2022 at 9:00 AM CST. Listen • 47:03. French N.G.O. Musique et Sante (Music and Health). Music therapy in children's ward. (BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty Images) . Many of us turn to music to feel better. But music can also help us physically heal.

1350 Words. 6 Pages. 12 Works Cited. Open Document. In definition, music therapy is, "the clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals" (American Music Therapy). Music has been an element of the human psyche since early ancestors fell asleep to the rhythmic sounds of waves lapping against the ...

The Healing Power of Music Essay. In December of 1992, David Ott's father was dying of cancer. On Christmas Eve morning he went into a coma. The family gathered in the small hospital room knowing that their beloved husband and father would not be with them long. Since it was Christmas Eve, carolers were going through the hospital quietly singing.

Playing an instrument provides great comfort and solace, expressing what words cannot. Though the original intent may be for pure enjoyment, I believe in the power of playing an instrument for healing, contentment, and calming purposes. Now when I play in my own concerts, I remember my sister's so many years ago and am thankful for noticing ...

Recent research suggests that music engagement not only shapes our personal and cultural identities but also plays a role in mood regulation. 1 A 2022 review and meta-analysis of music therapy found an overall beneficial effect on stress-related outcomes. Moreover, music can be used to help in addressing serious mental health and substance use ...

The healing power of music | TEDxChicago • October 2021. Read transcript. Can smooth grooves and an exotic blend of cultural sounds heal what makes us not well? This band, a combination of traditional Indian instruments and vocals, electric guitar, percussion, and flute believes it is so. Meditate in the healing power of musical relaxation ...

And, as we've seen, classical music can work to calm us down and fill us with a sense of peace. It's thought that the structure of the music, the sounds and melodies, can have an impact on our mind and body. Because calming or classical types of music can reduce anxiety, they can also help us balance our mood.

The Healing Power Of Music. Free 7-Day Course. Click any word to translate. People are enamored with music. It touches our souls in profound ways that words alone cannot equal. It stirs our imagination, invigorates our bodies, and transforms our moods. It can lift us up or overwhelm us with emotion.

The Healing Power of Music Essay. Usually, when one considers what they can do to fight off a cold, relieve pain, or alleviate mental illness, the first things that comes to mind may be to take over-the-counter drugs or prescribed medications. However, the cure to these and many other infirmities may be found within your own ipod.

Music has the power to touch our hearts and souls. It can make us laugh, cry, or dance. It can lift our spirits and provide comfort in times of trouble. For all of these reasons, music is a truly powerful force in the world. The radio is often playing some rhythmically driving "Rock and Roll" song.

Music Can Heal the Brain. New therapies are using rhythm, beat and melody to help patients recover language, hearing, motion and emotion. One day when Laurel was 11, she began to feel dizzy while ...

For more, stream KCBS Radio now. She spoke with KCBS Radio's Bret Burkhart on "As Prescribed" about the 16-year-old program. Research has shown that music therapy can help a broad range of ...

Scientific studies and anecdotal evidence alike have long demonstrated the therapeutic and healing powers of music. The members of the Northwest Arkansas chapter of Soldier Songs and Voices witness music's transformative potential every week in their work with patients at the Veterans Health Care System of the Ozarks and with veterans in the community.

It was at this time that my wise band teacher taught me one of the most important lessons of my life. And that's why I believe in the healing power of music. I saw this power in the week following my classmate's death. As I played many different kinds of song, happy, sad, dark, light, angry, soothing, I could notice and see the physical and ...

The experience proved transformative for those involved, paying testament to the healing power of music. Putting a long-form choral concert at the heart of the Easter schedules was to be applauded ...