- About Project

- Testimonials

Business Management Ideas

Essay on Happiness

List of essays on happiness, essay on happiness – short essay (essay 1 – 150 words), essay on happiness – for kids and children (essay 2 – 200 words), essay on happiness – 10 lines on happiness written in english (essay 3 – 250 words), essay on happiness (essay 4 – 300 words), essay on happiness – ways to be happy (essay 5 – 400 words), essay on happiness – for school students (class 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 standard) (essay 6 – 500 words), essay on happiness – ways of developing happiness (essay 7 – 600 words), essay on happiness – sources of suffering, happiness and conclusion (essay 8 – 750 words), essay on happiness – long essay on happiness (essay 9 – 1000 words).

Happiness is defined by different people in different ways. When we feel positive emotions we tend to feel happy. That is what happiness is all about. Happiness is also regarded as the mental state of a person in an optimistic manner.

Every person defines happiness in his/her own manner. In whatever manner you may define happiness; the truth is that it is vital for a healthy and prosperous life.

In order to make students understand what true happiness is all about, we have prepared short essays for students which shall enlighten them further on this topic.

Audience: The below given essays are exclusively written for school students (Class 3, 4 ,5, 6 and 7 Standard).

Introduction:

Happiness is a state of mind and the feeling expressed when things are going great. It is what we feel when we get our first car, buy a new house or graduate with the best grades. Happiness should be distinguished from joy. When joy is a constant state of mind, happiness depends on events in our lives.

Importance of Happiness:

The opposite of happiness is sadness which is a state of negativity in the mindset. When we remain sad for an extended period of time it can lead to depression. To avoid this state of mind we must always remind ourselves of happenings in our lives that made us happy.

Conclusion:

Though life throws countless challenges at us on a daily basis, if we drown in those challenges we would definitely become depressed. It is important that we find positive things in our daily lives to get excited about and feel the happiness.

Happiness is a state of mind which makes you feel accomplished in life and having everything in this world without a single reason to repent. Well, although there can be no perfect definition of happiness; happiness is when you feel you’re at the top of the world where a sense of complete satisfaction prevails.

The meaning of happiness is relative and varies from people to people. For some, happiness is when you experience professional success, reunions with family and friends, eating out, reading books or watching good movies. While for others, happiness can be accomplished by some weekend activities which might help you de-stress and get the satisfaction of mind.

If you involve yourself in social activities where you help the needy and provide support to the weaker section of the society, you can experience happiness if not anything else. When a young boy flies a kite, plays with mud, and watches the nature, for him, that is the greatest happiness in the world.

The happiness of mind is often considered quite contrary to jealousy and anger which you experience once you have failed or unaccomplished any desired goal. You should always try to rehearse the ways of keeping yourself satisfied and keeping away from negativity to experience peace and happiness in life. True happiness begins where desire ends!

What is happiness? It is a state of being happy. But it does not mean to be happy all the time. Happiness is a feeling of something good that is happening in our life. We feel happy when we achieve something. But happiness is spread when our dear one is happy as well. Some people find true happiness in playing with their pets, while some may find happiness in staying engaged in creative work.

Happiness is often derived from channelizing thoughts to positive thinking. However, it is not as simple as it may sound.

To achieve the state of complete happiness one has to practice on improving the state of life by:

1. Staying contended in life with what you have. Cribbing and grumbling never lead to happiness.

2. Staying focused on the current life instead of daydreaming of the good days or old days.

3. Stop blaming for something that went terribly wrong in life. The life is all about moving on. Stop worrying and set new goals in life.

4. Being thankful to God for all the good things that you have in your life.

5. Having good people around you who can boost up positivity in your life.

Everyone desires to be happy in life. Happiness cannot be achieved without establishing complete control of one’s thoughts as it is very easy to be carried away by the waves of thoughts and emotions surrounding us. Remind yourself of the good things of your life and be thankful about it.

What is happiness? Some would state that happiness implies being well off. Others would state that for them, happiness intends to be sound. You will discover individuals saying that for them happiness implies having love in their life, having numerous companions, a great job, or accomplishing a specific objective. There are individuals, who trust that the want of a specific wish would make happiness in their life; however, it may not be so. Having true happiness is something which is desired by all.

The Path to Happiness:

There are small things which when incorporated into our daily lives, can lead us to the path of happiness. For instance, instead of thinking about problems, we should actually be thinking about the solutions. Not only will we be happier but we shall also be able to solve our problems faster. Similarly, once in a while, you start the day with the longing to achieve a few targets. Toward the day’s end, you may feel disappointed and miserable, in light of the fact that you haven’t possessed the capacity to do those things. Take a look at what you have done, not at what you have not possessed the capacity to do. Regularly, regardless of whether you have achieved a ton amid the day, you let yourself feel disappointed, due to some minor assignments you didn’t achieve. This takes away happiness from you.

Again, now and then, you go throughout the day effectively completing numerous plans, yet as opposed to feeling cheerful and fulfilled, you see what was not cultivated and feel troubled. It is out of line towards you.

Each day accomplishes something good which you enjoy doing. It may tend to be something little, such as purchasing a book, eating something you cherish, viewing your most loved program on TV, heading out to a motion picture, or simply having a walk around the shoreline. Even small things can bring great levels of happiness in our lives and motivate us for new goals.

Happiness is not what you feel from outside, rather it is something which comes from your inner soul. We should find happiness in us rather than searching for it in worldly desires.

Happiness is defined by different people in different ways. Some find happiness in having a luxurious life while some find it in having loving people around them rather than money. True happiness lies within us and our expectation of happiness. It is something that should be felt and cannot be explained in words.

Even though this simple word has a lot of meaning hidden in it, many fail to understand the real one or feel the real happiness. Finding happiness in the outer world is the main reason for this failure. Nothing can buy you happiness, whether be the favorite thing you desire for or the person you love the most or the career you build, unless and until you feel it within yourself.

Ways to be Happy:

Bring happiness and soulful life to yourself rather than expecting it from the outside world like things, money, etc. Being happy is not as easy as advised to be one happier person. To be content and happy with whatever you have and yourself it takes time and patience. You should practice to be a happier person in all moments and eventually you will notice that no sorrow can sink you down.

Whatever good or bad happened in your past shouldn’t bother your present. Learn to live today with more happiness than yesterday and forget about your past sadness for a harmonious life. Thankfulness to the life you got is another important character you should acquire to be happy. If you compare yourself with someone with better luxurious life, then you will never be happy or content and do it the other way.

Don’t depress your mind with bad and negative thoughts about yourself and around. Try to find every goodness in a situation you face and accept the things that already happened, whether good or bad. Never forget to choose merrier and positive people to be closer to you so that their vibes will also help you in being one merrier person.

Whenever you feel low and depressed never hesitate to go to those around you to find happiness. But be aware of those negative ones that may pull you even deeper into the bad thoughts. Always surround yourself with positive thinking and motivating people so that you can rise higher even from the deepest fall.

Happiness is nothing but a feeling that will be seeded into your soul only if you wish to and nothing other than yourself can indulge this feeling in you. Don’t spoil your life finding happiness somewhere else.

Happiness is a very complicated thing. Happiness can be used both in emotional or mental state context and can vary largely from a feeling from contentment to very intense feeling of joy. It can also mean a life of satisfaction, good well-being and so many more. Happiness is a very difficult phenomenon to use words to describe as it is something that can be felt only. Happiness is very important if we want to lead a very good life. Sadly, happiness is absent from the lives of a lot of people nowadays. We all have our own very different concept of happiness. Some of us are of the opinion that we can get happiness through money, others believe they can only get true happiness in relationships, some even feel that happiness can only be gotten when they are excelling in their profession.

As we might probably know, happiness is nothing more than the state of one being content and happy. A lot of people in the past, present and some (even in the future will) have tried to define and explain what they think happiness really is. So far, the most reasonable one is the one that sees happiness as something that can only come from within a person and should not be sought for outside in the world.

Some very important points about happiness are discussed below:

1. Happiness can’t be bought with Money:

A lot of us try to find happiness where it is not. We associate and equate money with happiness. If at all there is happiness in money then all of the rich people we have around us would never feel sad. What we have come to see is that even the rich amongst us are the ones that suffer depression, relationship problems, stress, fear and even anxiousness. A lot of celebrities and successful people have committed suicide, this goes a long way to show that money or fame does not guarantee happiness. This does not mean that it is a bad thing to be rich and go after money. When you have money, you can afford many things that can make you and those around you very happy.

2. Happiness can only come from within:

There is a saying that explains that one can only get true happiness when one comes to the realisation that only one can make himself/herself happy. We can only find true happiness within ourselves and we can’t find it in other people. This saying and its meaning is always hammered on in different places but we still refuse to fully understand it and put it into good use. It is very important that we understand that happiness is nothing more than the state of a person’s mind. Happiness cannot come from all the physical things we see around us. Only we through our positive emotions that we can get through good thoughts have the ability to create true happiness.

Our emotions are created by our thoughts. Therefore, it is very important that we work on having only positive thoughts and this can be achieved when we see life in a positive light.

Happiness is desired by every person. However, there are very few persons that attain happiness easily in life.

It is quite tough to get happiness in life as people usually link it with the things and the people around them. The simple fact is that happiness usually starts as well as finishes with your own life. All those people who understand this fact easily get the true happiness in their life.

Happiness in Relationships:

There are lots of people who link happiness with the money and there are few others also who link it with the personal relations. It is very important to know that if you are not happy with yourself then, it is not possible to remain happy in your relationship as well.

The problems in the relationship have been increasing speedily and the main cause behind it is the huge amount of expectation that we have from the other individual. We always want them to make us feel happy. For example, some people feel happy if their partner plans a surprise for them or if he/she buy them a new dress. But all these things are not a true source of happiness in life.

Ways of Developing Happiness:

The lack of happiness in the relationship not only exists in couples but also in the relationship of friends, sister – brother or parent-child.

The following are the few ways that help in creating happiness in the relationships:

1. Pay Attention to Yourself:

You should always pay attention to yourself to get happiness. You should not give importance to any other person in your life in comparison to yourself and also expect the same from that person. Giving too much importance to the other and not receiving anything back from them makes a person disappointed and happiness gets lost.

2. Have some Initiative:

You can make the plan of traveling outside yourself. Don’t wait for your parent, partner or kid to take you outside. You can ask them to come along with you if they want. But, if they decline your offer then, don’t get discouraged and carry on your trip plan along with full happiness.

3. Provide some Space:

It is necessary to provide some amount of space to every individual and spend some time with oneself. It helps in creating happiness.

Happiness is Necessary for Good Life:

It does not matter that whether you are a working expert, a schoolchild, a retired person or a housewife, happiness is necessary for everybody to live a good and happy life. Happiness is essential for an individual’s emotional comfort. A person who is not fit emotionally will feel an impact on his complete health that will drain very soon.

Unluckily, despite the fact that happiness is tremendously necessary, people do not give so much importance to all those habits which can keep them happy. They are so excessively captivated inside their professional lives as well as other nuts and bolts of life that they overlook to relish the happy memories of their life. It is also the main reason that problems like anxiety, stress, and depression are increasing gradually in people’s lives today.

Happiness is an internal feeling. It is a healthy emotion. Happiness helps us to stay fit both mentally and physically. Happiness helps in lowering stress and keeping away from any health issues. The reason of happiness may be different for different person. You just need to find out what actually makes you happy. So, if you want real happiness in life then, you need to understand that only you can make yourself happy.

“There is no way to happiness, happiness is the way” this sentence has been attributed to Buddha. Well, at least that’s what it says on one sticker in my dorm room. The fact is that man has occupied himself with the path to happiness for millennia. Something happened during our evolution that made us deeply question the purpose of our existence. People like Buddha are part of the answer, or at least they try to give us the answer.

Since these questions have troubled us there have been many who sought to answer them and by doing so, they formed philosophies and religions. The search for earthly happiness will make many do incredible deeds but if this energy is used in the wrong way it can cause great suffering. How can we know which recipe for happiness is the best one and what we should devote our time and attention to? The trick is, there is no right answer and as the first sentence of this essay states, there is no way to be happy because being happy is the way. That’s how I got my head around this problem, let me explain some more.

Source of Suffering:

At the expense of sounding Buddhist, when you think about most of the things that make us unhappy are material in nature. They are the things that we really do not need but they make us feel happy. This notion is not just something the wise man from the 6 th century BC India expressed but many more have said this before and after him. Socrates and Jesus to name just a few.

What I find interesting in the struggle for happiness is the paradox present in the instructions to reach it. One has a thought all through life to be good and hard working so he can get the things he wants and needs later on in life but then as you start to struggle for the money you realize that your life is turning into a money grabbing game. So, the source of happiness and stability becomes the source of all your anxiety and aggression. Naturally, we can see how some people thought that all material things stand on the path to our happiness.

But what about the immaterial, what if you are in love with someone you are not supposed to love? The above instruction would tell you to surrender your heart’s desire and you will be free from constraints. Is this happiness? Or is it the struggle to do and achieve the impossible the real source of happiness?

Source of Happiness:

People often forget that they are animals and like all of them they have a logic to their nature and their own specific needs. Like all the other animal’s people are caught in the struggle for existence and sometimes surviving the day can be a real ordeal if you get caught in the wrong circumstances. Men has made himself safe from most of the things that could have harmed him in nature but in doing so he forgot what he has made.

Think about the present from a historical perspective. Even a hundred years ago most people lost up to 80% of all their children to diseases, clean water was a rarity for most of our existence, and people actually had to labor to make food and to have enough to feed their family all through the year. The fact is we have a lot to be grateful for in the present age and the fact that some of us are unhappy because we do not have all our heart’s desires is just a symptom of collective infancy. Having all of your loved ones around you, with a roof to shelter under and with lots of delicious food is the only source of happiness man needs everything else should just be a bonus.

Happiness cannot be found by rejecting everything that is material or by earning more money then you can spend. The trick is to find balance by looking at yourself and the lives of people around you and by understanding that there is a lot to be grateful for, the trick is to stop searching for a path and to understand that we are already walking on one. As long as we are making any type of list of the prerequisite for our life of happiness, we will end up unsatisfied because life does not grant wishes we are the ones that make them come true. Often the biggest change in our lives comes from a simple change of perspective rather than from anything we can own.

Happiness is the state of emotional wellbeing and being contented. Happiness is expressed through joyful moments and smiles. It is a desirable feeling that everybody want to have at all times. Being happy is influenced by situations, achievements and other circumstances. Happiness is an inner quality that reflects on the state of mind. A peaceful state of mind is considered to be happiness. The emotional state of happiness is mixture of feelings of joy, satisfaction, gratitude, euphoria and victory.

How happiness is achieved:

Happiness is achieved psychologically through having a peaceful state of mind. By a free state of mind, I mean that there should be no stressful factors to think about. Happiness is also achieved through accomplishment of goals that are set by individuals. There is always happiness that accompanies success and they present feelings of triumph and contentment.

To enable personal happiness in life, it is important that a person puts himself first and have good self-perception. Putting what makes you happy first, instead of putting other people or other things first is a true quest towards happiness. In life, people tend to disappoint and putting them as a priority always reduces happiness for individuals. There is also the concept of practicing self-love and self-acceptance. Loving oneself is the key to happiness because it will mean that it will not be hard to put yourself first when making decisions.

It is important for an individual to control the thoughts that goes on in their heads. A peaceful state of mind is achieved when thoughts are at peace. It is recommended that things that cause a stressful state of mind should be avoided.

Happiness is a personal decision that is influenced by choices made. There is a common phrase on happiness; “happiness is a choice” which is very true because people choose if they want to be happy or not. Happiness is caused by circumstances and people have the liberty to choose those circumstance and get away from those that make them unhappy.

Happiness is also achieved through the kind of support system that an individual has. Having a family or friends that are supportive will enable the achievement of happiness. Communicating and interacting with the outside world is important.

Factors Affecting Happiness:

Sleep patterns influence the state of mind thus influence happiness. Having enough sleep always leads to happy mornings and a good state of mind for rest of the day. Sleep that is adequate also affects the appearance of a person. There is satisfaction that comes with having enough sleep. Enough rest increases performance and productivity of an individual and thus more successes and achievements are realized and happiness is experienced.

Another factor affecting happiness is the support network of an individual. A strong support network of family and friends results in more happiness. Establishing good relationships with neighbors, friends and family through regular interactions brings more happiness to an individual. With support network, the incidences of stressful moments will be reduced because your family and friends will always be of help.

Sexual satisfaction has been established to affect happiness. It is not just about getting the right partner anymore. It is about having a partner that will satisfy you sexually. There is a relationship between sex and happiness because of the hormones secreted during sexual intercourse. The hormone is called oxytocin and responsible for the happiness due to sexual satisfaction. Satisfaction also strengthens the relationships between the partners and that creates happiness.

Wealth also plays a significant role in happiness. There is a common phrase that is against money and happiness: “money cannot buy happiness” is this true? Personally, I believe that being financially stable contributes to happiness because you will always have peace of mind and many achievements. Peace of mind is possible for wealthy people because they do not have stressors here and then compared to poor people. Also, when a person is wealthy, they can afford to engage in luxurious activities that relaxes the mind and create happiness. For a person to be wealthy, they will have had many achievements in life. These achievement make them happy.

A good state of health is an important factor that influences the happiness of individuals. A healthy person will be happy because there are no worries of diseases or pain that they are experiencing. When a person is healthy, their state of mind is at peace because they are not afraid of death or any other health concerns. Not only the health of individuals is important, but also the health of the support system of the person. Friends and family’s state of health will always have an impact on what we feel as individuals because we care about them and we get worried whenever they are having bad health.

Communication and interactions are important in relation to an individual’s happiness. Having a support system is not enough because people need to communicate and interact freely. Whenever there are interactions like a social gathering where people talk and eat together, more happiness is experienced. This concept is witnessed in parties because people are always laughing and smiling in parties whenever they are with friends.

Communication is key to happiness because it helps in problem solving and relieving stressors in life. Sharing experiences with a support system creates a state of wellbeing after the solution is sought. Sometime when I am sad, I take my phone and call a friend or a family member and by the time the phone call is over, I always feel better and relieved of my worries.

Happiness is an important emotion that influences how we live and feel on a daily basis. Happiness is achieved in simple ways. People have the liberty to choose happiness because we are not bound by any circumstances for life. Factors that influence happiness are those that contribute to emotional wellbeing. Physical wellbeing also affects happiness. Every individual finds happiness in their own because they know what makes them happy and what doesn’t.

Emotions , Happiness , Psychology

Get FREE Work-at-Home Job Leads Delivered Weekly!

Join more than 50,000 subscribers receiving regular updates! Plus, get a FREE copy of How to Make Money Blogging!

Message from Sophia!

Like this post? Don’t forget to share it!

Here are a few recommended articles for you to read next:

- Which is More Important in Life: Love or Money | Essay

- Essay on My School

- Essay on Solar Energy

- Essay on Biodiversity

No comments yet.

Leave a reply click here to cancel reply..

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Billionaires

- Donald Trump

- Warren Buffett

- Email Address

- Free Stock Photos

- Keyword Research Tools

- URL Shortener Tools

- WordPress Theme

Book Summaries

- How To Win Friends

- Rich Dad Poor Dad

- The Code of the Extraordinary Mind

- The Luck Factor

- The Millionaire Fastlane

- The ONE Thing

- Think and Grow Rich

- 100 Million Dollar Business

- Business Ideas

Digital Marketing

- Mobile Addiction

- Social Media Addiction

- Computer Addiction

- Drug Addiction

- Internet Addiction

- TV Addiction

- Healthy Habits

- Morning Rituals

- Wake up Early

- Cholesterol

- Reducing Cholesterol

- Fat Loss Diet Plan

- Reducing Hair Fall

- Sleep Apnea

- Weight Loss

Internet Marketing

- Email Marketing

Law of Attraction

- Subconscious Mind

- Vision Board

- Visualization

Law of Vibration

- Professional Life

Motivational Speakers

- Bob Proctor

- Robert Kiyosaki

- Vivek Bindra

- Inner Peace

Productivity

- Not To-do List

- Project Management Software

- Negative Energies

Relationship

- Getting Back Your Ex

Self-help 21 and 14 Days Course

Self-improvement.

- Body Language

- Complainers

- Emotional Intelligence

- Personality

Social Media

- Project Management

- Anik Singal

- Baba Ramdev

- Dwayne Johnson

- Jackie Chan

- Leonardo DiCaprio

- Narendra Modi

- Nikola Tesla

- Sachin Tendulkar

- Sandeep Maheshwari

- Shaqir Hussyin

Website Development

Wisdom post, worlds most.

- Expensive Cars

Our Portals: Gulf Canada USA Italy Gulf UK

Privacy Overview

Happiness Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on happiness.

Happiness is something which we can’t describe in words it can only be felt from someone’s expression of a smile. Likewise, happiness is a signal or identification of good and prosperous life. Happiness is very simple to feel and difficult to describe. Moreover, happiness comes from within and no one can steal your happiness.

Can Money Buy You Happiness?

Every day we see and meet people who look happy from the outside but deep down they are broken and are sad from the inside. For many people, money is the main cause of happiness or grief. But this is not right. Money can buy you food, luxurious house, healthy lifestyle servants, and many more facilities but money can’t buy you happiness.

And if money can buy happiness then the rich would be the happiest person on the earth. But, we see a contrary image of the rich as they are sad, fearful, anxious, stressed, and suffering from various problems.

In addition, they have money still they lack in social life with their family especially their wives and this is the main cause of divorce among them.

Also, due to money, they feel insecurity that everyone is after their money so to safeguard their money and them they hire security. While the condition of the poor is just the opposite. They do not have money but they are happy with and stress-free from these problems.

In addition, they take care of their wife and children and their divorce rate is also very low.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Happiness Comes from Within

As we now know that we can’t buy happiness with money and there is no other shortcut to happiness. It is something that you feel from within.

In addition, true happiness comes from within yourself. Happiness is basically a state of mind.

Moreover, it can only be achieved by being positive and avoiding any negative thought in mind. And if we look at the bright side of ourselves only then we can be happy.

Happiness in a Relationship

People nowadays are not satisfied with their relationship because of their differences and much other reason. But for being happy in a relationship we have to understand that there are some rules or mutual understanding that keeps a relationship healthy and happy.

Firstly, take care of yourself then your partner because if you yourself are not happy then how can you make your partner happy.

Secondly, for a happy and healthy relationship give you partner some time and space. In addition, try to understand their feeling and comfort level because if you don’t understand these things then you won’t be able to properly understand your partner.

Most importantly, take initiative and plan to go out with your partner and family. Besides, if they have plans then go with them.

To conclude, we can say that happiness can only be achieved by having positive thinking and enjoying life. Also, for being happy and keeping the people around us happy we have to develop a healthy relationship with them. Additionally, we also have to give them the proper time.

FAQs about Happiness

Q.1 What is True Happiness? A.1 True happiness means the satisfaction that you find worthy. The long-lasting true happiness comes from life experience, a feeling of purpose, and a positive relationship.

Q.2 Who is happier the rich or the poor and who is more wealthy rich or poor? A.2 The poor are happier then the rich but if we talk about wealth the rich are more wealthy then the poor. Besides, wealth brings insecurity, anxiety and many other problems.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Happiness?

Defining Happiness, and How to Become Happier

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

Verywell/ Jiaqi Zhou

How to Cultivate Happiness

How to be a happier person.

Happiness is something that people seek to find, yet what defines happiness can vary from one person to the next. Typically, happiness is an emotional state characterized by feelings of joy, satisfaction, contentment, and fulfillment. While happiness has many different definitions, it is often described as involving positive emotions and life satisfaction.

When most people talk about the true meaning of happiness, they might be talking about how they feel in the present moment or referring to a more general sense of how they feel about life overall.

Because happiness tends to be such a broadly defined term, psychologists and other social scientists typically use the term ' subjective well-being ' when they talk about this emotional state. Just as it sounds, subjective well-being tends to focus on an individual's overall personal feelings about their life in the present.

Two key components of happiness (or subjective well-being) are:

- The balance of emotions: Everyone experiences both positive and negative emotions, feelings, and moods. Happiness is generally linked to experiencing more positive feelings than negative ones.

- Life satisfaction: This relates to how satisfied you feel with different areas of your life including your relationships, work, achievements, and other things that you consider important.

Another definition of happiness comes from the ancient philosopher Aristotle, who suggested that happiness is the one human desire, and all other human desires exist as a way to obtain happiness. He believed that there were four levels of happiness: happiness from immediate gratification, from comparison and achievement, from making positive contributions, and from achieving fulfillment.

Happiness, Aristotle suggested, could be achieved through the golden mean, which involves finding a balance between deficiency and excess.

Signs of Happiness

While perceptions of happiness may be different from one person to the next, there are some key signs that psychologists look for when measuring and assessing happiness.

Some key signs of happiness include:

- Feeling like you are living the life you wanted

- Going with the flow and a willingness to take life as it comes

- Feeling that the conditions of your life are good

- Enjoying positive, healthy relationships with other people

- Feeling that you have accomplished (or will accomplish) what you want in life

- Feeling satisfied with your life

- Feeling positive more than negative

- Being open to new ideas and experiences

- Practicing self-care and treating yourself with kindness and compassion

- Experiencing gratitude

- Feeling that you are living life with a sense of meaning and purpose

- Wanting to share your happiness and joy with others

One important thing to remember is that happiness isn't a state of constant euphoria . Instead, happiness is an overall sense of experiencing more positive emotions than negative ones.

Happy people still feel the whole range of human emotions—anger, frustrastion, boredom, loneliness, and even sadness—from time to time. But even when faced with discomfort, they have an underlying sense of optimism that things will get better, that they can deal with what is happening, and that they will be able to feel happy again.

Types of Happiness

There are many different ways of thinking about happiness. For example, the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle made a distinction between two different kinds of happiness: hedonia and eudaimonia.

- Hedonia: Hedonic happiness is derived from pleasure. It is most often associated with doing what feels good, self-care, fulfilling desires, experiencing enjoyment, and feeling a sense of satisfaction.

- Eudaimonia: This type of happiness is derived from seeking virtue and meaning. Important components of eudaimonic well-being including feeling that your life has meaning, value, and purpose. It is associated more with fulfilling responsibilities, investing in long-term goals, concern for the welfare of other people, and living up to personal ideals.

Hedonia and eudemonia are more commonly known today in psychology as pleasure and meaning, respectively. More recently, psychologists have suggested the addition of the third component that relates to engagement . These are feelings of commitment and participation in different areas of life.

Research suggests that happy people tend to rank pretty high on eudaimonic life satisfaction and better than average on their hedonic life satisfaction.

All of these can play an important role in the overall experience of happiness, although the relative value of each can be highly subjective. Some activities may be both pleasurable and meaningful, while others might skew more one way or the other.

For example, volunteering for a cause you believe in might be more meaningful than pleasurable. Watching your favorite tv show, on the other hand, might rank lower in meaning and higher on pleasure.

Some types of happiness that may fall under these three main categories include:

- Joy: A often relatively brief feeling that is felt in the present moment

- Excitement: A happy feeling that involves looking forward to something with positive anticipation

- Gratitude: A positive emotion that involves being thankful and appreciative

- Pride: A feeling of satisfaction in something that you have accomplished

- Optimism: This is a way of looking at life with a positive, upbeat outlook

- Contentment: This type of happiness involves a sense of satisfaction

While some people just tend to be naturally happier, there are things that you can do to cultivate your sense of happiness.

Pursue Intrinsic Goals

Achieving goals that you are intrinsically motivated to pursue, particularly ones that are focused on personal growth and community, can help boost happiness. Research suggests that pursuing these types of intrinsically-motivated goals can increase happiness more than pursuing extrinsic goals like gaining money or status.

Enjoy the Moment

Studies have found that people tend to over earn—they become so focused on accumulating things that they lose track of actually enjoying what they are doing.

So, rather than falling into the trap of mindlessly accumulating to the detriment of your own happiness, focus on practicing gratitude for the things you have and enjoying the process as you go.

Reframe Negative Thoughts

When you find yourself stuck in a pessimistic outlook or experiencing negativity, look for ways that you can reframe your thoughts in a more positive way.

People have a natural negativity bias , or a tendency to pay more attention to bad things than to good things. This can have an impact on everything from how you make decisions to how you form impressions of other people. Discounting the positive—a cognitive distortion where people focus on the negative and ignore the positive—can also contribute to negative thoughts.

Reframing these negative perceptions isn't about ignoring the bad. Instead, it means trying to take a more balanced, realistic look at events. It allows you to notice patterns in your thinking and then challenge negative thoughts.

Impact of Happiness

Why is happiness so important? Happiness has been shown to predict positive outcomes in many different areas of life including mental well-being, physical health, and overall longevity.

- Positive emotions increase satisfaction with life.

- Happiness helps people build stronger coping skills and emotional resources.

- Positive emotions are linked to better health and longevity. One study found that people who experienced more positive emotions than negative ones were more likely to have survived over a 13 year period.

- Positive feelings increase resilience. Resilience helps people better manage stress and bounce back better when faced with setbacks. For example, one study found that happier people tend to have lower levels of the stress hormone cortisol and that these benefits tend to persist over time.

- People who report having a positive state of well-being are more likely to engage in healthy behaviors such as eating fruits and vegetables and engaging in regular physical exercise.

- Being happy may make help you get sick less often. Happier mental states are linked to increased immunity.

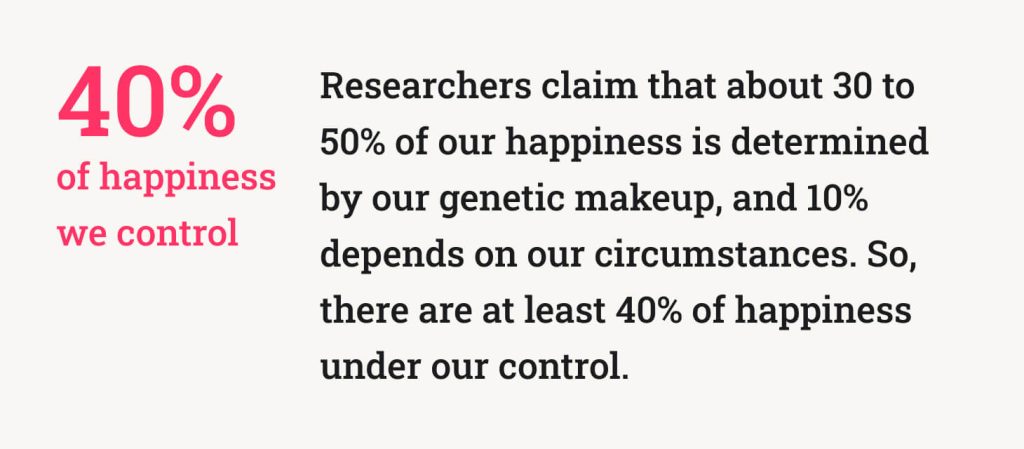

Some people seem to have a naturally higher baseline for happiness—one large-scale study of more than 2,000 twins suggested that around 50% of overall life satisfaction was due to genetics, 10% to external events, and 40% to individual activities.

So while you might not be able to control what your “base level” of happiness is, there are things that you can do to make your life happier and more fulfilling. Even the happiest of individuals can feel down from time to time and happiness is something that all people need to consciously pursue.

Cultivate Strong Relationships

Social support is an essential part of well-being. Research has found that good social relationships are the strongest predictor of happiness. Having positive and supportive connections with people you care about can provide a buffer against stress, improve your health, and help you become a happier person.

In the Harvard Study of Adult Development, a longitudinal study that looked at participants over 80 years, researchers found that relationships and how happy people are in those relationships strongly impacted overall health.

So if you are trying to improve your happiness, cultivating solid social connections is a great place to start. Consider deepening your existing relationships and explore ways to make new friends.

Get Regular Exercise

Exercise is good for both your body and mind. Physical activity is linked to a range of physical and psychological benefits including improved mood. Numerous studies have shown that regular exercise may play a role in warding off symptoms of depression, but evidence also suggests that it may also help make people happier, too.

In one analysis of past research on the connection between physical activity and happiness, researchers found a consistent positive link.

Even a little bit of exercise produces a happiness boost—people who were physically active for as little as 10 minutes a day or who worked out only once a week had higher levels of happiness than people who never exercised.

Show Gratitude

In one study, participants were asked to engage in a writing exercise for 10 to 20 minutes each night before bed. Some were instructed to write about daily hassles, some about neutral events, and some about things they were grateful for. The results found that people who had written about gratitude had increase positive emotions, increased subjective happiness, and improve life satisfaction.

As the authors of the study suggest, keeping a gratitude list is a relatively easy, affordable, simple, and pleasant way to boost your mood. Try setting aside a few minutes each night to write down or think about things in your life that you are grateful for.

Find a Sense of Purpose

Research has found that people who feel like they have a purpose have better well-being and feel more fulfilled. A sense of purpose involves seeing your life as having goals, direction, and meaning. It may help improve happiness by promoting healthier behaviors.

Some things you can do to help find a sense of purpose include:

- Explore your interests and passions

- Engage in prosocial and altruistic causes

- Work to address injustices

- Look for new things you might want to learn more about

This sense of purpose is influenced by a variety of factors, but it is also something that you can cultivate. It involves finding a goal that you care deeply about that will lead you to engage in productive, positive actions in order to work toward that goal.

Press Play for Advice On Reaching Your Dreams

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast , featuring best-selling author Dave Hollis, shares how to create your best life. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

Challenges of Finding Happiness

While seeking happiness is important, there are times when the pursuit of life satisfaction falls short. Some challenges to watch for include:

Valuing the Wrong Things

Money may not be able to buy happiness, but there is research that spending money on things like experiences can make you happier than spending it on material possessions.

One study, for example, found that spending money on things that buy time—such as spending money on time-saving services—can increase happiness and life satisfaction.

Rather than overvaluing things such as money, status, or material possessions, pursuing goals that result in more free time or enjoyable experiences may have a higher happiness reward.

Not Seeking Social Support

Social support means having friends and loved ones that you can turn to for support. Research has found that perceived social support plays an important role in subjective well-being. For example, one study found that perceptions of social support were responsible for 43% of a person's level of happiness.

It is important to remember that when it comes to social support, quality is more important than quantity. Having just a few very close and trusted friends will have a greater impact on your overall happiness than having many casual acquaintances.

Thinking of Happiness as an Endpoint

Happiness isn’t a goal that you can simply reach and be done with. It is a constant pursuit that requires continual nurturing and sustenance.

One study found that people who tend to value happiness most also tended to feel the least satisfied with their lives. Essentially, happiness becomes such a lofty goal that it becomes virtually unattainable.

“Valuing happiness could be self-defeating because the more people value happiness, the more likely they will feel disappointed,” suggest the authors of the study.

Perhaps the lesson is to not make something as broadly defined as “happiness” your goal. Instead, focus on building and cultivating the sort of life and relationships that bring fulfillment and satisfaction to your life.

It is also important to consider how you personally define happiness. Happiness is a broad term that means different things to different people. Rather than looking at happiness as an endpoint, it can be more helpful to think about what happiness really means to you and then work on small things that will help you become happier. This can make achieving these goals more manageable and less overwhelming.

History of Happiness

Happiness has long been recognized as a critical part of health and well-being. The "pursuit of happiness" is even given as an inalienable right in the U.S. Declaration of Independence. Our understanding of what will bring happiness, however, has shifted over time.

Psychologists have also proposed a number of different theories to explain how people experience and pursue happiness. These theories include:

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

The hierarchy of needs suggests that people are motivated to pursue increasingly complex needs. Once more basic needs are fulfilled, people are then motivated by more psychological and emotional needs.

At the peak of the hierarchy is the need for self-actualization, or the need to achieve one's full potential. The theory also stresses the importance of peak experiences or transcendent moments in which a person feels deep understanding, happiness, and joy.

Positive Psychology

The pursuit of happiness is central to the field of positive psychology . Psychologists who study positive psychology are interested in learning ways to increase positivity and helping people live happier, more satisfying lives.

Rather than focusing on mental pathologies, the field instead strives to find ways to help people, communities, and societies improve positive emotions and achieve greater happiness.

Finley K, Axner M, Vrooman K, Tse D. Ideal levels of prosocial involvement in relation to momentary affect and eudaimonia: Exploring the golden mean . Innov Aging . 2020;4(Suppl 1):614. doi:10.1093/geroni/igaa057.2083

Kringelbach ML, Berridge KC. The neuroscience of happiness and pleasure . Soc Res (New York) . 2010;77(2):659-678.

Panel on Measuring Subjective Well-Being in a Policy-Relevant Framework; Committee on National Statistics; Division on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; National Research Council; Stone AA, Mackie C, editors. Subjective Well-Being: Measuring Happiness, Suffering, and Other Dimensions of Experience [Internet]. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US).

Lee MA, Kawachi I. The keys to happiness: Associations between personal values regarding core life domains and happiness in South Korea . PLoS One . 2019;14(1):e0209821. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0209821

Hsee CK, Zhang J, Cai CF, Zhang S. Overearning . Psychol Sci . 2013;24(6):852-9

Carstensen LL, Turan B, Scheibe S, et al. Emotional experience improves with age: evidence based on over 10 years of experience sampling . Psychol Aging . 2011;26(1):21‐33. doi:10.1037/a0021285

Steptoe A, Wardle J. Positive affect and biological function in everyday life . Neurobiol Aging . 2005;26 Suppl 1:108‐112. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.08.016

Sapranaviciute-Zabazlajeva L, Luksiene D, Virviciute D, Bobak M, Tamosiunas A. L ink between healthy lifestyle and psychological well-being in Lithuanian adults aged 45-72: a cross-sectional study . BMJ Open . 2017;7(4):e014240. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014240

Costanzo ES, Lutgendorf SK, Kohut ML, et al. Mood and cytokine response to influenza virus in older adults . J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci . 2004;59(12):1328‐1333. doi:10.1093/gerona/59.12.1328

Lyubomirsky S, Sheldon KM, Schkade D. Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change . Review of General Psychology. 2005;9 (2):111–131. doi:0.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111

The Harvard Gazette. Good genes are nice, but joy is better .

Zhang Z, Chen W. A systematic review of the relationship between physical activity and happiness . J Happiness Stud 20, 1305–1322 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9976-0

Cunha LF, Pellanda LC, Reppold CT. Positive psychology and gratitude interventions: a randomized clinical trial . Front Psychol . 2019;10:584. Published 2019 Mar 21. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00584

Ryff CD. Psychological well-being revisited: advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia . Psychother Psychosom . 2014;83(1):10‐28. doi:10.1159/000353263

Whillans AV, Dunn EW, Smeets P, Bekkers R, Norton MI. Buying time promotes happiness . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2017;114(32):8523‐8527. doi:10.1073/pnas.1706541114

Gulacti F. The effect of perceived social support on subjective well-being . Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences . 2010;2(2):3844-3849. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.602

Mauss IB, Tamir M, Anderson CL, Savino NS. Can seeking happiness make people unhappy? [corrected] Paradoxical effects of valuing happiness [published correction appears in Emotion. 2011 Aug;11(4):767]. Emotion . 2011;11(4):807‐815. doi:10.1037/a0022010

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Essays About Happiness: 5 Essay Examples and 6 Writing Prompts

Being happy and content is essential to living a successful life. If you are writing essays about happiness, start by reading our helpful guide.

Whenever we feel positive emotions rushing through our heads, chances are we are feeling happy. Happiness is what you feel when you enter the house, the smell of your favorite food being cooked or when you finally save up enough money to buy something you’ve wanted. It is an undeniably magical feeling.

Happiness can do wonders for your productivity and well-being; when you are happy, you are more energetic, optimistic, and motivated. So it is, without a doubt, important. However, do not become caught up in trying to be happy, as this may lead to worse problems. Instead, allow yourself to feel your emotions; be authentic, even if that means feeling a little more negative.

5 Top Essay Examples

1. causes of happiness by otis curtis, 2. how to be happy by tara parker-pope, 3. reflections on ‘happiness’ by shahzada sultan.

- 4. Happiness is Overrated by John Gorman

5. Toxic positivity by Suhani Mahajan

6 prompts for essays about happiness, 1. why is it important to be happy, 2. what is happiness to you, 3. the role of material things in happiness, 4. how does happiness make you more productive, 5. is true happiness achievable, 6. happiness vs. truth.

“If you don’t feel good about yourself you will have a similarly negative attitude towards others and education is one way of having good self-esteem, as it helps you to live life successfully and happily. Education is one way of getting that dream job and education is an essential cog in the wheel to living comfortably and happily. One English survey that included over 15,000 participants revealed that 81 percent of people who had achieved a good level of education had a high level of life satisfaction.”

Based on personal beliefs and research, Curtis’ essay describes different contributing causes to people’s happiness. These include a loving, stable family and good health. Interestingly, there is a positive correlation between education level and happiness, as Curtis cites statistics showing that education leads to high self-esteem, which can make you happier.

“Socratic questioning is the process of challenging and changing irrational thoughts. Studies show that this method can reduce depression symptoms. The goal is to get you from a negative mindset (“I’m a failure.”) to a more positive one (“I’ve had a lot of success in my career. This is just one setback that doesn’t reflect on me. I can learn from it and be better.”)”

Parker-Pope writes about the different factors of happiness and how to practice mindfulness and positivity in this guide. She gives tips such as doing breathing exercises, moving around more, and spending time in places and with people that make you happy. Most importantly, however, she reminds readers that negative thoughts should not be repressed. Instead, we should accept them but challenge that mindset.

“Happiness is our choice of not leaving our mind and soul at the mercy of the sways of excitement. Happiness cannot eliminate sorrow, suffering, pain or death from the scheme of things, but it can help keep fear, anxiety, sadness, hopelessness, pessimism and other fathers of unhappiness at bay.”

Sultan discusses what happiness means to her personally. It provides an escape from all the dreariness and lousy news of daily life, not eliminating negative thoughts but keeping them at a distance, even just for a moment. She writes that to be happy; we should not base our happiness on the outcomes of our actions. We cannot control the world around us, so we should not link our happiness to it. If something doesn’t go our way, that is just how the world works. It is useless to be sad over what we cannot control.

4. Happiness is Overrated by John Gorman

“Our souls do float across the sea of life, taking on water as they go, sinking ever so slightly — perhaps even imperceptibly — into despair. But our souls are not the bucket. Happiness itself is. And it’s the bucket we use to pour water out our souls and keep us afloat. What we really need is peace. Peace patches the holes in our souls and stops the leaking. Once we have peace, we will no longer need to seek happiness.”

In his essay, Gorman reflects on how he stopped trying to chase happiness and instead focused on finding peace in life. He writes that we are often so desperate looking for happiness that our lives become complicated, chaotic, and even depressing at times. He wants readers to do what they are passionate about and be their authentic selves; that way, they will find true happiness. You might also be interested in these essays about courage .

“That’s the mindset most of us have. Half of toxic positivity is just the suppression of 200% acceptable feelings such as anger, fear, sadness, confusion, and more. Any combination of such feelings is deemed “negative.” Honestly, mix ‘em up and serve them to me in a cocktail, eh? (Fine, fine, a mocktail. I reserve my right to one of those little umbrellas though.)

But by closing ourselves off to anything but positivity, we’re experiencing the same effects as being emotionally numb. Why are we doing this to ourselves?”

Mahajan writes about the phenomenon known as “toxic positivity” in which everyone is expected to be happy with their lives. It trivializes people’s misfortunes and sufferings, telling them to be happy with what they have instead. Mahajan opposes this, believing that everyone’s feelings are valid. She writes that it’s okay to be sad or angry at times, and the stigma around “negative feelings” should be erased. When we force ourselves to be happy, we may feel emotionally numb or even sad, the exact opposite of being happy.

Many would say that happiness aids you in many aspects of your life. Based on personal experience and research, discuss the importance of being happy. Give a few benefits or advantages of happiness. These can include physical, mental, and psychological benefits, as well as anything else you can think of.

Happiness means different things to different people and may come from various sources. In your essay, you can also explain how you define happiness. Reflect on this feeling and write about what makes you happy and why. Explain in detail for a more convincing essay; be sure to describe what you are writing about well.

Happiness has a myriad of causes, many of which are material. Research the extent to which material possessions can make one happy, and write your essay about whether or not material things can truly make us happy. Consider the question, “Can money buy happiness?” Evaluate the extent to which it can or cannot, depending on your stance.

Happiness has often been associated with a higher level of productivity. In your essay, look into the link between these two. In particular, discuss the mental and chemical effects of happiness. Since this topic is rooted in research and statistics, vet your sources carefully: only use the most credible sources for an accurate essay.

In their essays, many, including Gorman and Mahajan, seem to hold a more critical view of happiness. Our world is full of suffering and despair, so some ask: “Can we truly be happy on this earth?” Reflect on this question and make the argument for your position. Be sure to provide evidence from your own experiences and those of others.

In dystopian stories, authorities often restrict people’s knowledge to keep them happy. We are seeing this even today, with some governments withholding crucial information to keep the population satisfied or stable. Write about whether you believe what they are doing is defensible or not, and provide evidence to support your point.

For help with this topic, read our guide explaining “what is persuasive writing ?”

For help picking your next essay topic, check out our top essay topics about love .

Martin is an avid writer specializing in editing and proofreading. He also enjoys literary analysis and writing about food and travel.

View all posts

1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Philosophy, One Thousand Words at a Time

Happiness: What is it to be Happy?

Author: Kiki Berk Category: Ethics , Phenomenology and Existentialism Words: 992

Listen here

Do you want to be happy? If you’re like most people, then yes, you do.

But what is happiness? What does it mean to be “happy”? [1]

This essay discusses four major philosophical theories of happiness. [2]

1. Hedonism

According to hedonism, happiness is simply the experience of pleasure. [3] A happy person has a lot more pleasure than displeasure (pain) in her life. To be happy, then, is just to feel good. In other words, there’s no difference between being happy and feeling happy.

Famous hedonists include the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus and the modern English philosophers Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. [4] These philosophers all took happiness to include intellectual pleasures (such as reading a book) in addition to physical pleasures (such as having sex).

Although we associate being happy with feeling good, many philosophers think that hedonism is mistaken.

First, it’s possible to be happy without feeling good (such as when a happy person has a toothache), and it’s also possible to feel good without being happy (such as when an unhappy person gets a massage). Since happiness and pleasure can come apart, they can’t be the same thing.

Second, happiness and pleasure seem to have different properties. Pleasures are often fleeting, simple, and superficial (think of the pleasure involved in eating ice cream), whereas happiness is supposed to be lasting, complex, and profound. Things with different properties can’t be identical, so happiness can’t be the same thing as pleasure.

These arguments suggest that happiness and pleasure aren’t identical. That being said, it’s hard to imagine a happy person who never feels good. So, perhaps happiness involves pleasure without being identical to it.

2. Virtue Theory

According to virtue theory, happiness is the result of cultivating the virtues—both moral and intellectual—such as wisdom, courage, temperance, and patience. A happy person must be sufficiently virtuous. To be happy, then, is to cultivate excellence and to flourish as a result. This view is famously held by Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics. [5]

Linking happiness to virtue has the advantage of treating happiness as a lasting, complex, and profound phenomenon. It also explains how happiness and pleasure can come apart, since a person can be virtuous without feeling good, and a person can feel good without being virtuous.

In spite of these advantages, however, virtue theory is questionable. An important part of being virtuous is being morally good. But are immoral people always unhappy? Arguably not. Many bad people seem happy in spite of—or even because of—their unsavory actions. And a similar point can be made about intellectual virtue: unwise or irrational people aren’t always unhappy, either. In fact, some of these people seem happy as a direct result of their intellectual deficiencies. “Ignorance is bliss,” the saying goes!

But virtue theorists have a response here. Maybe some immoral people seem happy, on the surface; but that doesn’t mean that they are truly happy, at some deeper level. And the same thing can be said about people who lack the intellectual virtues: ignorance may lead to bliss, but that bliss isn’t true happiness. So, there seems to be some room for debate on these issues.

3. Desire Satisfaction Theory

According to the desire satisfaction theory, happiness consists in getting what you want—whatever that happens to be. A happy person has many of her desires satisfied; and the more her desires are satisfied, the happier she is.

Even though getting what you want can be a source of happiness, identifying happiness with desire satisfaction is problematic.

To start, this implies that the only way to become happier is by satisfying a desire. This seems wrong. Sometimes our happiness is increased by getting something we didn’t previously want—such as a surprise birthday party or getting stuck taking care of a neighbor’s cat. This implies that desire satisfaction is not necessary for happiness.

Desire satisfaction is not always sufficient for happiness, either. Unfortunately, it is common for people to feel disappointed when they get what they want. Many accomplishments, such as earning a degree or winning a tournament, simply don’t bring the long-lasting happiness that we expect. [6]

So, even if getting what we want sometimes makes us happy, these counterexamples suggest that happiness does not consist in desire satisfaction. [7]

4. Life Satisfaction Theory

According to the life satisfaction theory, happiness consists in being satisfied with your life. A happy person has a positive impression of her life in general, even though she might not be happy about every single aspect of it. To be happy, then, means to be content with your life as a whole.

It’s controversial whether life satisfaction is affective (a feeling) or cognitive (a belief). On the one hand, life satisfaction certainly comes with positive feelings. On the other hand, it’s possible to step back, reflect on your life, and realize that it’s good, even when you’re feeling down. [8]

One problem for this theory is that it’s difficult for people to distinguish how they feel in the moment from how they feel about their lives overall. Studies have shown that people report feeling more satisfied with their lives when the weather is good, even though this shouldn’t make that much of a difference. But measuring life satisfaction is complicated, so perhaps such studies should be taken with a grain of salt. [9]

5. Conclusion

Understanding what happiness is should enable you to become happier.

First, decide which theory of happiness you think is true, based on the arguments.

Second, pursue whatever happiness is according to that theory: seek pleasure and try to avoid pain (hedonism), cultivate moral and intellectual virtue (virtue theory), decide what you really want and do your best to get it (desire satisfaction theory), or change your life (or your attitude about it) so you feel (or believe) that it’s going well (life satisfaction theory).

And if you’re not sure which theory of happiness is true, then you could always try pursuing all of these things. 😊

[1] This might seem like an empirical (scientific) question rather than a philosophical one. However, this essay asks the conceptual question of what happiness is, and conceptual questions belong to philosophy, not to science.

[2] Happiness is commonly distinguished from “well-being,” i.e., the state of a life that is worth living. Whether or not happiness is the same thing as well-being is an open question, but most philosophers think it isn’t. See, for example, Haybron (2020).

[3] The word “hedonism” has different uses in philosophy. In this paper, it means that happiness is the same thing as pleasure (hedonism about happiness). But sometimes it is used to mean that happiness is the only thing that has intrinsic value (hedonism about value) or that humans are always and only motivated by pleasure (psychological hedonism). It’s important not to confuse these different uses of the word.

[4] For more on Epicurus and happiness, see Konstan (2018). For more on Bentham and Mill on happiness, see Driver (2014), as well as John Stuart Mill on The Good Life: Higher-Quality Pleasures by Dale E. Miller and Consequentialism by Shane Gronholz

[5] For more on Plato and happiness, see Frede (2017); for more on Aristotle and happiness, see Kraut (2018), and on the Stoics and happiness, see Baltzly (2019).

[6] For a discussion of the phenomenon of disappointment in this context see, for example, Ben Shahar (2007).

[7] For more objections to the desire satisfaction theory, see Shafer-Landau (2018) and Vitrano (2013).

[8] If happiness is life satisfaction, then happiness seems to be “subjective” in the sense that a person cannot be mistaken about whether or not she is happy. Whether happiness is subjective in this sense is controversial, and a person who thinks that a person can be mistaken about whether or not she is happy will probably favor a different theory of happiness.

[9] See Weimann, Knabe and Schob (2015) and Berk (2018).

Baltzly, Dirk, “Stoicism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2019/entries/stoicism/>.

Berk, Kiki (2018). “Does Money Make Us Happy? The Prospects and Problems of Happiness Research in Economics,” in Journal of Happiness Studies, 19, 1241-1245.

Ben-Shahar, Tal (2007). Happier . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Driver, Julia, “The History of Utilitarianism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/utilitarianism-history/>.

Frede, Dorothea, “Plato’s Ethics: An Overview”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/plato-ethics/>.

Haybron, Dan, “Happiness”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/happiness/>.

Konstan, David, “Epicurus”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/epicurus/>.

Kraut, Richard, “Aristotle’s Ethics”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/aristotle-ethics/>.

Shafer-Landau, Russ (2018). The Ethical Life: Fundamental Readings in Ethics and Moral Problems. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vitrano, Christine (2013). The Nature and Value of Happiness. Boulder: Westview Press.

Weimann, Joachim, Andreas Knabe, and Ronnie Schob (2015). Measuring Happiness . Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Related Essays

Meaning in Life: What Makes Our Lives Meaningful? by Matthew Pianalto

The Philosophy of Humor: What Makes Something Funny? by Chris A. Kramer

Virtue Ethics by David Merry

John Stuart Mill on The Good Life: Higher-Quality Pleasures by Dale E. Miller

Consequentialism by Shane Gronholz

Ethical Egoism by Nathan Nobis

Ancient Cynicism: Rejecting Civilization and Returning to Nature by G. M. Trujillo, Jr.

What Is It To Love Someone? by Felipe Pereira

Camus on the Absurd: The Myth of Sisyphus by Erik Van Aken

Ethics and Absolute Poverty: Peter Singer and Effective Altruism by Brandon Boesch

Is Death Bad? Epicurus and Lucretius on the Fear of Death by Frederik Kaufman

PDF Download

Download this essay in PDF .

About the Author

Dr. Kiki Berk is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Southern New Hampshire University. She received her Ph.D. in Philosophy from the VU University Amsterdam in 2010. Her research focuses on Beauvoir’s and Sartre’s philosophies of death and meaning in life.

Follow 1000-Word Philosophy on Facebook , Twitter and subscribe to receive email notifications of new essays at the bottom of 1000WordPhilosophy.com

Share this:, 20 thoughts on “ happiness: what is it to be happy ”.

- Pingback: Camus on the Absurd: The Myth of Sisyphus – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Existentialism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Hope – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: John Stuart Mill on The Good Life: Higher-Quality Pleasures – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Consequentialism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Mill’s Proof of the Principle of Utility – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Ethical Egoism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: What Is It To Love Someone? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Ethics and Absolute Poverty: Peter Singer and Effective Altruism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Is Death Bad? Epicurus and Lucretius on the Fear of Death – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Is Immortality Desirable? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Online Philosophy Resources Weekly Update | Daily Nous

- Pingback: Reason is the Slave to the Passions: Hume on Reason vs. Desire – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Virtue Ethics – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Meaning in Life: What Makes Our Lives Meaningful? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: The Philosophy of Humor: What Makes Something Funny? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Aristotle on Friendship: What Does It Take to Be a Good Friend? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: W.D. Ross’s Ethics of “Prima Facie” Duties – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Ancient Cynicism: Rejecting Civilization and Returning to Nature – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Comments are closed.

Discover more from 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

There are roughly two philosophical literatures on “happiness,” each corresponding to a different sense of the term. One uses ‘happiness’ as a value term, roughly synonymous with well-being or flourishing. The other body of work uses the word as a purely descriptive psychological term, akin to ‘depression’ or ‘tranquility’. An important project in the philosophy of happiness is simply getting clear on what various writers are talking about: what are the important meanings of the term and how do they connect? While the “well-being” sense of happiness receives significant attention in the contemporary literature on well-being, the psychological notion is undergoing a revival as a major focus of philosophical inquiry, following on recent developments in the science of happiness. This entry focuses on the psychological sense of happiness (for the well-being notion, see the entry on well-being ). The main accounts of happiness in this sense are hedonism, the life satisfaction theory, and the emotional state theory. Leaving verbal questions behind, we find that happiness in the psychological sense has always been an important concern of philosophers. Yet the significance of happiness for a good life has been hotly disputed in recent decades. Further questions of contemporary interest concern the relation between the philosophy and science of happiness, as well as the role of happiness in social and political decision-making.

1.1 Two senses of ‘happiness’

1.2 clarifying our inquiry, 2.1 the chief candidates, 2.2 methodology: settling on a theory, 2.3 life satisfaction versus affect-based accounts, 2.4 hedonism versus emotional state, 2.5 hybrid accounts, 3.1 can happiness be measured, 3.2 empirical findings: overview, 3.3 the sources of happiness, 4.1 doubts about the value of happiness, 4.2 restoring happiness to the theory of well-being, 4.3 is happiness overrated, 5.1 normative issues, 5.2 mistakes in the pursuit of happiness, 5.3 the politics of happiness, other internet resources, related entries, 1. the meanings of ‘happiness’.

What is happiness? This question has no straightforward answer, because the meaning of the question itself is unclear. What exactly is being asked? Perhaps you want to know what the word ‘happiness’ means. In that case your inquiry is linguistic. Chances are you had something more interesting in mind: perhaps you want to know about the thing , happiness, itself. Is it pleasure, a life of prosperity, something else? Yet we can’t answer that question until we have some notion of what we mean by the word.

Philosophers who write about “happiness” typically take their subject matter to be either of two things, each corresponding to a different sense of the term:

- A state of mind

- A life that goes well for the person leading it