- EssayBasics.com

- Pay For Essay

- Write My Essay

- Homework Writing Help

- Essay Editing Service

- Thesis Writing Help

- Write My College Essay

- Do My Essay

- Term Paper Writing Service

- Coursework Writing Service

- Write My Research Paper

- Assignment Writing Help

- Essay Writing Help

- Call Now! (USA) Login Order now

- EssayBasics.com Call Now! (USA) Order now

- Writing Guides

Is Science Good Or Bad? (Essay Sample)

Is science good or bad.

Since the beginning of time man has been on endless exploration of information and knowledge. Because of his hunger and thirst he has accumulated knowledge in many fields. During prehistoric times the desires and wants of man were less but when these cravings started to grow, he started to formulate new ideas. Because of science, man has made a remarkable improvement of life through inventions. Man has used the knowledge of science to understand how the universe works and how to do many things. It is evident that through science man has created modern treatment that has helped in curing various illnesses. Information has greatly improved and an example is the emergence of the internet. However, one can agree that man has done totally immoral things in the name of science; nevertheless it does not mean that science is bad overall, it only means that some bad people have used science for bad intentions. Science is a good thing as well as bad thing. This paper attempts to describe the things that make science good and the things that make science bad.

Because of scientific inventions man is living today a pleasant life. One can imagine, is it possible for humanity live on this world without, the internet, vehicles, television, electricity, medicine, mobile phones, and other millions of scientific inventions? Currently, because of science there is modern medicine which is used to treat and cure sickness. Sickness that could be fatal for mankind is curable because of science and hence the life of people is prolonged. No one can truly oppose the significance of science breakthroughs; however it safe to say that one can underrate the risks of scientific discoveries in the society. Scientific discoveries can have consequences and it is the obligation of man to search for solutions when problems arise instead of just assuming the concealed consequences. Science is a good thing because human is now able to irrigate and plow the land. Through science it is possible to study heavenly bodies like stars, planets, meteors, and comets. One can predict the weather today and this is helpful because people can take special precautions to avoid damage.

All good things can be said about science and its benefits to man however there are problems that may arise. As much as there is electricity, cars that use fuel, and factories, one tends to forget about global warming. Man desires nuclear energy without worrying about the nuclear refuse and hazardous consequences of nuclear radiation. Man wants to have wooden furniture, and paper without thinking about the depletion of natural resources. When all these is taken into consideration, it clear that wants have consequences and these need solutions. Other scientific discoveries can have hazardous results. A good example of this is the discovery of atoms. This field has led to invention of atomic bombs that has brought about the deaths of millions of people. This is evident when the first atomic bomb was used during the world war two on Japanese cities. Till this day, people are still suffering from the effects of nuclear radiation.

In conclusion, the question of whether science is good or bad can be a tricky one. One can list the whole day the benefits of science as well as the consequences. Man has used the knowledge of science to understand how the universe works and how to do many things. Scientific discoveries can have consequences and it is the obligation of man to search for solutions when problems arise instead of just assuming the concealed consequences. Scientific discoveries have made remarkable changes in our environment today.

Science Interviews

- Earth Science

- Engineering

Science: For good or bad?

Interview with , part of the show scrutinizing science, bonsai tree.

Science is usually touted as a good thing, but could there be a dark side? Graihagh Jackson debated this with Tom Ziessen...

Tom - It becomes quite obvious as to 'why science?' when you look back at at all the advances that have happened.

So I'm Tom Zeissan. I am in the Engaging Science team at the Wellcome Trust.

Graihagh - I was interested in talking to Tom about Wellcome because, well, it provides science funding for thousands of people across the world. It's not a government body, it's a charity and thus has no obligations to do so. Why then does it? Well it starts with a chap called Sir Henry Wellcome...

Tom - He was an American marketeer; he was born in the mid-west and from an early age was trying to sell products to friends and family. He started out selling invisible ink, I think, was his first thing...

Graihagh - Invisible ink!

Tom - Invisible ink which was, just basically, lemon juice - I think he was sixteen when he started that.

He came over to the UK in the 1880s to found the Wellcome Foundation, and Henry Wellcome was always very interested in the arts and science of healing through the ages.

Henry died in 1936 and in his Will he set up the Wellcome Trust.

Graihagh - Because I think what's quite different about Wellcome is that most people get their funding from big research bodies from the government so, EPSRC, STFC, whereas Wellcome sits in this unusual sort of framework?

Tom - Yes, that's right. So we are a very large funder of research that's non-government - we're independent; we're not unique in that respect. But our funding supports, currently, over fourteen thousand people in more than seventy countries.

Graihagh - And I suppose that brings me onto my next question. I wonder - why science? - why should science be put on a pedestal among all the other things that this money could be used for?

Tom - Actually, Wellcome Trust is not just interested in science. We're interested in all kinds of research related to health and wellbeing but, coming back to your question of: why do we place science as such an important part of what we do - it's because we think that science is a great way of giving us insights into the way the world works, the way we work. It becomes quite obvious as to 'why science?' when you look back at all the advances that have happened since 1936, or since the sort of scientific revolution and the improvements that's made to health and wellbeing.

Graihagh - But arguably it's not always been used for good things. I'm thinking the haber bosch process was used by the Nazi's as the poisonous gas in the holocaust, and then there's nuclear weapons. You've painted a very rosy picture of the use of science there.

Tom - Uh, yes. I mean, I think anything can be useful for bad purposes as well as for good purposes. That's not really a problem with science, that's really a problem with humanity and I don't think science is a force for good or evil. It's a way of understanding the world, understanding of what potential there is there but, hopefully, the majority of uses for it are beneficial.

Graihagh - I suppose the other side of this is that science has enabled populations to grow, it's enabled us to develop cars, which then produce lots of greenhouse gases. And I read this great quote that "man has survived millennia without science but may not survive a mere two centuries of science." With all these problems we're in some ways creating for ourselves, if that makes sense?

Tom - It does make sense. I think it's a very pessimistic view of the world but there's no question that there are problems related to scientific developments; there are more people around; they're living longer and using more resources. They're also happier, healthier and able to enjoy lives that wouldn't have been possible prior to science.

Graihagh - The future of science looks to be an interesting place. In the time that the Naked Scientists have been around, we've seen the advent of global warming and accelerated destruction of our natural world...

David Attenborough - This loss not only diminishes the beauty and diversity of the natural world, it also puts our own future in jeopardy.

Graihagh - And 3D printed guns...

So in this case what's happening is that you're downloading a digital file that defines this object - in this case a gun. You send that to a 3D printer which literally builds it up until you end up with a gun.

Graihagh - But also a new age of physics...

We have discovered a new particle, a boson. Most probably a Higgs boson but we have to find out which kind of Higgs Boson this is - what are its properties and where do they point to?

Ladies and gentleman... we have detected gravitational waves. We did it!

Graihagh - That only leads me to question - what next for science? Only time will tell...

- Previous Why cannabis gets you stoned

- Next Is social media changing journalism?

Related Content

Does the 5:2 diet work, contagious earworms, covid-19: has science failed, britain's sexist scientists, the science of brainwashing, add a comment, support us, forum discussions.

Positive and negative effects of Science

- September 19, 2017

- Education , General

This might be the umpteenth time you will be reading a huge article on the merits and demerits of science. However, it seems like we cannot really differentiate between the boons and devils of science. One cannot debate on the fact that science plays an inseparable part in everyone’s life. Directly or indirectly, everyone is affected by the progression of science. In the context of a fast-paced life, we need to stall a bit and evaluate ourselves and question whether every progression made in every possible sector of science are justified or not.

Positive effects of Science:

• Convenience: It is amazing as how times have changed. It took us eternity to develop a non-human mode of transportation, but the recent couple of centuries saw us traveling over the mountains and beyond the waters. You can travel back and forth covering the deepest and darkest corners there are to explore. We can communicate to our dear ones sitting at one end of the World to the other. With the introduction of Artificial Intelligence, one does not even need to talk, but simulate a healthy conversation or run a chore.

• Dramatic increase of lifespan: Remember reading the horrific plague that almost nullified Europe as much as to the extent of rejuvenating it through the period of Renaissance? Fast forward to the 21st century and you will see people being spoilt for choice, to live, if yes, how many years would they prefer to. It baffles to see such transformation and enhancement in the field of medical science and technology . With the cure to every known disease, or at least the development of new drugs has brightened the survival rate exponentially. Stillborn and other infant fatalities have gone down significantly, and the third World countries are getting back on their feet as well.

• New technologies and better understanding of where we live in: Technology and Science go hand in hand, and there is no doubt that we have been engulfed in the technological world. Technology has been seeped in with such precision and deftness that we don’t really appreciate it that much. Science has also let us know about our Universe, and there is so much more to the 75% Water-25% Land concept. There are many wonders yet to be discovered, and with science one-day humans will acquire the knowledge of infinity with the help of science.

Negative effects of Science:

• Aesthetically wrong at times: Forget the readings and writings of any religious texts and books. Focus on the alteration made possible by science that tend to haunt the mankind in future. Altering the genetic combination tends to disrupt the balance of the nature, and messes with the ecosystem as well. Genetic alterations on animals have proven to give dubious results and have faced a lot of criticism and backlash.

• Used in strengthening war chances: Gone are the days when people used to stamp their authorities through duels and wars were won with horses, elephants, swords, and other man-made weapons. Times have flown by and the nuclear trump card in every countries arsenal has bolstered the chance of destructing the Earth, and killing many in process.

• Stressful information: The deeper you delve into science; more likely you are going to come up with unrequired or harmful information’s. You might end up discovering some lethal elements buried deep down. Overloaded with information has compelled us to make headways into calamitic consequences.

• Overpopulation: One of the most ironical aspects of science. Science tells you the reason why the Earth is being overpopulated and the measures that should be taken to deal with it. On the other hand, science has enabled us to live longer than average expectancy, decreasing the mortality rate immensely. It might be easy to say that one should not opt for such life expectant drugs and operations, but weighing the emotional side of things it becomes difficult to stick to a rational decision.

• People connecting through social media, but drifting away in person: Technology enables us to talk to strangers staying miles away from us, but we don’t bother to communicate in person when we have the chance to. Artificial Intelligence has ignited the virtual method of communication , and that seems to become the norm in years to come.

Science might be a technical and rational component of this Universe, but the sword of morality has been hanging over the head of every person on this planet. One should greet the progression of science with open arms, but needs to check the rapid growth that might do more harm than good eventually.

Related Posts

Negative effects of Instagram

- August 4, 2018

Negative effects of online shopping

- August 1, 2018

Negative effects of cursing

- July 28, 2018

One comment

please help me to write a debate that science is not good opposing side

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Name *

Email *

Add Comment *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Post Comment

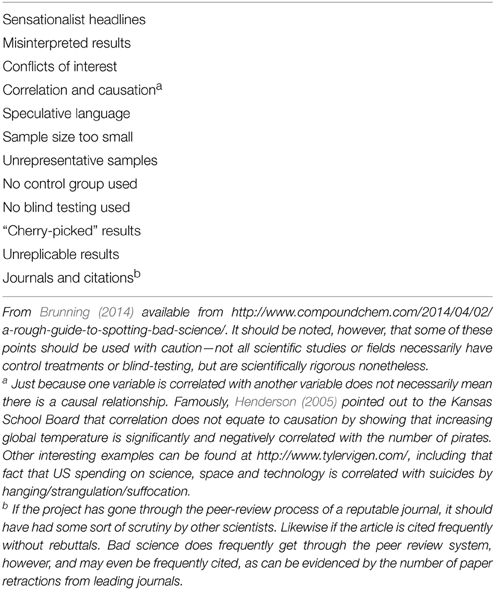

How to Tell the Difference Between Good and Bad Science

You don't need a stem degree to have high scientific literacy..

Posted December 18, 2018

Nothing makes headlines like the latest medical breakthrough. The heroic work of researchers should lead the news when it fundamentally changes our world and prospects for improved health. However, it can often be difficult to sort good science from bad.

When the Media Misleads

One of the reasons it is difficult to determine breakthrough versus dodgy science is that the media is motivated to present the latest scientific findings in the most interesting way possible. Unfortunately, the trend of clickbait has led to misleading articles like “Red wine compound helps kill off cancer cells, new study finds” from the LA Times . The natural takeaway of the article is that the compound resveratrol can help make radiation therapy more effective for people fighting cancer.

And yet, a quick review of the published study in question makes it apparent that the LA Times vastly overstated its implications. The study wasn’t performed on humans or even mice—it was carried out on melanoma cells in a petri dish. It is a far leap to extrapolate results from a petri dish to the human body. In this case, the problem comes with what wasn’t said rather than what was said. While the article does explain that the compound fights cancer cells, it doesn’t make the distinction that these are cells in a petri dish and not cells in the body—a big difference. That is why for each media review of a scientific study, it is critical to go to the source article or abstract.

A Quick Review of a Scientific Article

Where do you begin once you find the original study? Many people think that the Results section of an academic article is the best way to tell if the work is important. In fact, the most critical section of a research paper is the Methods section. This is the part that tells you whether or not you can trust the results.

Two Types of Study Methodologies to Know

First, there is one type of study that is commonly cited in the news: the clinical trial. A clinical trial evaluates the effectiveness of a treatment by comparing a group of people who were given a treatment to a group who were not, called a “control group.” The best kind of clinical trial is randomized; study coordinators place participants into treatment groups randomly rather than placing them in the group where they think the participants will respond most favorably.

One way of comparing treatment groups is with a placebo. One group receives the treatment and the other receives a placebo, commonly a sugar pill , which has no significant effect on health. While it can be useful to compare all versus nothing to assess efficacy, this is not always helpful or ethical. In fact, the World Medical Association has a specific provision around the use of placebos, stating that “the benefits, risks, burdens, and effectiveness of a new intervention must be tested against those of the best proven intervention.” A placebo may be used if no other intervention exists or if there is solid reasoning behind why another intervention is not needed.

Another study often relayed in the news is the observational study . This type of study does not assign treatments to different groups. Instead, it observes people who are already performing a health behavior—whether it be taking a drug or engaging in activities like smoking or exercise. One of the most famous observational studies is the Framingham Heart Study . This is an ongoing, epic project. It began in 1948 with 5,209 participants of the Massachusetts town of Framingham and is still collecting data and running participants today. Two considerable findings attributed to this study are that high blood pressure increases the risk of stroke and cigarette smoking increases the risk of heart disease.

What to Look for in the Methods Section

When it comes to examining the robustness of a study, whether it be a clinical trial or an observational study, it can be difficult to discern red flags from acceptable limitations. Generally, it is important to have a large sample size. However, this is not possible if a disease is rare or the population being studied is uncommon or difficult to recruit into a study. This does not mean that the research should be thrown out, just that the effect size of the results should be evaluated carefully, as well as the ability to generalize the study results to the population at large.

Along these lines, it is always preferable to have a representative population in the study. This has been a considerable fault of science in the past. A recent article from STAT News shed light on the clinical trial for Ninlaro, a drug for multiple myeloma. Despite the fact that almost 20 percent of multiple myeloma sufferers are black, only 1.8 percent of trial participants were black. This kind of skewed representation requires a dose of skepticism to evaluate the results—and a demand that medical researchers aim to do better.

The Methods section must also be detailed . This section should answer who, what, when, where, and how. Here are some questions that you could expect the Methods section of a clinical trial study to answer.

- Who was included in the study? Why were some people considered ineligible?

- What is the intervention measured? How was it administered?

- When and how long did this study run for?

- Where was the study run? Which hospital or facility?

- How was the data analyzed? What statistical methods were used? Why were they chosen?

- How were the treatment and control groups decided?

Sometimes all these questions may be answered, but there may still be lingering inconsistencies. If you are not certain if a Methods section is sound, ask a scientifically-minded friend to review it as well. Their different experiences may help them notice fallacies or allow them to explain why the methods were laid out in that way and are actually correct. Sometimes the media will review a study. Outlets devoted to science, medicine, or research are usually more adept at identifying holes in studies or acknowledging which are sound.

We look to the research communities to answer our most burning questions about health. The vast majority of studies are done in good faith with strong scientific foundation, but for the ones that are not, we need to be able to assess for ourselves what is good science and what is bad science.

Mylea Charvat, Ph.D. , is a clinical psychologist, translational neuroscientist, and the CEO and founder of the digital cognitive assessment company, Savonix.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Science and Pseudo-Science

The demarcation between science and pseudoscience is part of the larger task of determining which beliefs are epistemically warranted. This entry clarifies the specific nature of pseudoscience in relation to other categories of non-scientific doctrines and practices, including science denial(ism) and resistance to the facts. The major proposed demarcation criteria for pseudo-science are discussed and some of their weaknesses are pointed out. There is much more agreement on particular cases of demarcation than on the general criteria that such judgments should be based upon. This is an indication that there is still much important philosophical work to be done on the demarcation between science and pseudoscience.

1. The purpose of demarcations

2. the “science” of pseudoscience, 3.1 non-, un-, and pseudoscience, 3.2 non-science posing as science, 3.3 the doctrinal component, 3.4 a wider sense of pseudoscience, 3.5 the objects of demarcation, 3.6 a time-bound demarcation, 4.1 the logical positivists, 4.2 falsificationism, 4.3 the criterion of puzzle-solving, 4.4 criteria based on scientific progress, 4.5 epistemic norms, 4.6 multi-criterial approaches, 5. two forms of pseudo-science, 6.1 scepticism, 6.2 resistance to facts, 6.3 conspiracy theories, 6.4 bullshit, 6.5 epistemic relativism, 7. unity in diversity, cited works, philosophically-informed literature on pseudosciences and contested doctrines, other internet resources, related entries.

Demarcations of science from pseudoscience can be made for both theoretical and practical reasons (Mahner 2007, 516). From a theoretical point of view, the demarcation issue is an illuminating perspective that contributes to the philosophy of science in much the same way that the study of fallacies contributes to our knowledge of informal logic and rational argumentation. From a practical point of view, the distinction is important for decision guidance in both private and public life. Since science is our most reliable source of knowledge in a wide range of areas, we need to distinguish scientific knowledge from its look-alikes. Due to the high status of science in present-day society, attempts to exaggerate the scientific status of various claims, teachings, and products are common enough to make the demarcation issue pressing in many areas. The demarcation issue is therefore important in practical applications such as the following:

Climate policy : The scientific consensus on ongoing anthropogenic climate change leaves no room for reasonable doubt (Cook et al. 2016; Powell 2019). Science denial has considerably delayed climate action, and it is still one of the major factors that impede efficient measures to reduce climate change (Oreskes and Conway 2010; Lewandowsky et al. 2019). Decision-makers and the public need to know how to distinguish between competent climate science and science-mimicking disinformation on the climate.

Environmental policies : In order to be on the safe side against potential disasters it may be legitimate to take preventive measures when there is valid but yet insufficient evidence of an environmental hazard. This must be distinguished from taking measures against an alleged hazard for which there is no valid evidence at all. Therefore, decision-makers in environmental policy must be able to distinguish between scientific and pseudoscientific claims.

Healthcare : Medical science develops and evaluates treatments according to evidence of their effectiveness and safety. Pseudoscientific activities in this area give rise to ineffective and sometimes dangerous interventions. Healthcare providers, insurers, government authorities and – most importantly – patients need guidance on how to distinguish between medical science and medical pseudoscience.

Expert testimony : It is essential for the rule of law that courts get the facts right. The reliability of different types of evidence must be correctly determined, and expert testimony must be based on the best available knowledge. Sometimes it is in the interest of litigants to present non-scientific claims as solid science. Therefore courts must be able to distinguish between science and pseudoscience. Philosophers have often had prominent roles in the defence of science against pseudoscience in such contexts. (Pennock 2011)

Science education : The promoters of some pseudosciences (notably creationism) try to introduce their teachings in school curricula. Teachers and school authorities need to have clear criteria of inclusion that protect students against unreliable and disproved teachings.

Journalism : When there is scientific uncertainty, or relevant disagreement in the scientific community, this should be covered and explained in media reports on the issues in question. Equally importantly, differences of opinion between on the one hand legitimate scientific experts and on the other hand proponents of scientifically unsubstantiated claims should be described as what they are. Public understanding of topics such as climate change and vaccination has been considerably hampered by organised campaigns that succeeded in making media portray standpoints that have been thoroughly disproved in science as legitimate scientific standpoints (Boykoff and Boykoff 2004; Boykoff 2008). The media need tools and practices to distinguish between legitimate scientific controversies and attempts to peddle pseudoscientific claims as science.

Attempts to define what we today call science have a long history, and the roots of the demarcation problem have sometimes been traced back to Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics (Laudan 1983). Cicero’s arguments for dismissing certain methods of divination in his De divinatione has considerable similarities with modern criteria for the demarcation of science (Fernandez-Beanato 2020). However it was not until the 20th century that influential definitions of science have contrasted it against pseudoscience. Philosophical work on the demarcation problem seems to have waned after Laudan’s (1983) much noted death certificate according to which there is no hope of finding a necessary and sufficient criterion of something as heterogeneous as scientific methodology. In more recent years, the problem has been revitalized. Philosophers attesting to its vitality maintain that the concept can be clarified by other means than necessary and sufficient criteria (Pigliucci 2013; Mahner 2013) or that such a definition is indeed possible although it has to be supplemented with discipline-specific criteria in order to become fully operative (Hansson 2013).

The Latin word “pseudoscientia” was used already in the first half of the 17th century in discussions about the relationship between religion and empirical investigations (Guldentops 2020, 288n). The oldest known use of the English word “pseudoscience” dates from 1796, when the historian James Pettit Andrew referred to alchemy as a “fantastical pseudo-science” (Oxford English Dictionary). The word has been in frequent use since the 1880s (Thurs and Numbers 2013). Throughout its history the word has had a clearly defamatory meaning (Laudan 1983, 119; Dolby 1987, 204). It would be as strange for someone to proudly describe her own activities as pseudoscience as to boast that they are bad science. Since the derogatory connotation is an essential characteristic of the word “pseudoscience”, an attempt to extricate a value-free definition of the term would not be meaningful. An essentially value-laden term has to be defined in value-laden terms. This is often difficult since the specification of the value component tends to be controversial.

This problem is not specific to pseudoscience, but follows directly from a parallel but somewhat less conspicuous problem with the concept of science. The common usage of the term “science” can be described as partly descriptive, partly normative. When an activity is recognized as science this usually involves an acknowledgement that it has a positive role in our strivings for knowledge. On the other hand, the concept of science has been formed through a historical process, and many contingencies influence what we call and do not call science. Whether we call a claim, doctrine, or discipline “scientific” depends both on its subject area and its epistemic qualities. The former part of the delimitation is largely conventional, whereas the latter is highly normative, and closely connected with fundamental epistemological and metaphysical issues.

Against this background, in order not to be unduly complex a definition of science has to go in either of two directions. It can focus on the descriptive contents, and specify how the term is actually used. Alternatively, it can focus on the normative element, and clarify the more fundamental meaning of the term. The latter approach has been the choice of most philosophers writing on the subject, and will be at focus here. It involves, of necessity, some degree of idealization in relation to common usage of the term “science”, in particular concerning the delimitation of the subject-area of science.

The English word “science” is primarily used about the natural sciences and other fields of research that are considered to be similar to them. Hence, political economy and sociology are counted as sciences, whereas studies of literature and history are usually not. The corresponding German word, “Wissenschaft”, has a much broader meaning and includes all the academic specialties, including the humanities. The German term has the advantage of more adequately delimiting the type of systematic knowledge that is at stake in the conflict between science and pseudoscience. The misrepresentations of history presented by Holocaust deniers and other pseudo-historians are very similar in nature to the misrepresentations of natural science promoted by creationists and homeopaths.

More importantly, the natural and social sciences and the humanities are all parts of the same human endeavour, namely systematic and critical investigations aimed at acquiring the best possible understanding of the workings of nature, people, and human society. The disciplines that form this community of knowledge disciplines are increasingly interdependent. Since the second half of the 20th century, integrative disciplines such as astrophysics, evolutionary biology, biochemistry, ecology, quantum chemistry, the neurosciences, and game theory have developed at dramatic speed and contributed to tying together previously unconnected disciplines. These increased interconnections have also linked the sciences and the humanities closer to each other, as can be seen for instance from how historical knowledge relies increasingly on advanced scientific analysis of archaeological findings.

The conflict between science and pseudoscience is best understood with this extended sense of science. On one side of the conflict we find the community of knowledge disciplines that includes the natural and social sciences and the humanities. On the other side we find a wide variety of movements and doctrines, such as creationism, astrology, homeopathy, and Holocaust denialism that are in conflict with results and methods that are generally accepted in the community of knowledge disciplines.

Another way to express this is that the demarcation problem has a deeper concern than that of demarcating the selection of human activities that we have for various reasons chosen to call “sciences”. The ultimate issue is “how to determine which beliefs are epistemically warranted” (Fuller 1985, 331). In a wider approach, the sciences are fact-finding practices , i.e., human practices aimed at finding out, as far as possible, how things really are (Hansson 2018). Other examples of fact-finding practices in modern societies are journalism, criminal investigations, and the methods used by mechanics to search for the defect in a malfunctioning machine. Fact-finding practices are also prevalent in indigenous societies, for instance in the forms of traditional agricultural experimentation and the methods used for tracking animal prey (Liebenberg 2013). In this perspective, the demarcation of science is a special case of the delimitation of accurate fact-finding practices. The delimitation between science and pseudoscience has much in common with other delimitations, such as that between accurate and inaccurate journalism and between properly and improperly performed criminal investigations (Hansson 2018).

3. The “pseudo” of pseudoscience

The phrases “demarcation of science” and “demarcation of science from pseudoscience” are often used interchangeably, and many authors seem to have regarded them as equal in meaning. In their view, the task of drawing the outer boundaries of science is essentially the same as that of drawing the boundary between science and pseudoscience.

This picture is oversimplified. All non-science is not pseudoscience, and science has non-trivial borders to other non-scientific phenomena, such as metaphysics, religion, and various types of non-scientific systematized knowledge. (Mahner (2007, 548) proposed the term “parascience” to cover non-scientific practices that are not pseudoscientific.) Science also has the internal demarcation problem of distinguishing between good and bad science.

A comparison of the negated terms related to science can contribute to clarifying the conceptual distinctions. “Unscientific” is a narrower concept than “non-scientific” (not scientific), since the former but not the latter term implies some form of contradiction or conflict with science. “Pseudoscientific” is in its turn a narrower concept than “unscientific”. The latter term differs from the former in covering inadvertent mismeasurements and miscalculations and other forms of bad science performed by scientists who are recognized as trying but failing to produce good science.

Etymology provides us with an obvious starting-point for clarifying what characteristics pseudoscience has in addition to being merely non- or un-scientific. “Pseudo-” (ψευδο-) means false. In accordance with this, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines pseudoscience as follows:

“A pretended or spurious science; a collection of related beliefs about the world mistakenly regarded as being based on scientific method or as having the status that scientific truths now have.”

Many writers on pseudoscience have emphasized that pseudoscience is non-science posing as science. The foremost modern classic on the subject (Gardner 1957) bears the title Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science . According to Brian Baigrie (1988, 438), “[w]hat is objectionable about these beliefs is that they masquerade as genuinely scientific ones.” These and many other authors assume that to be pseudoscientific, an activity or a teaching has to satisfy the following two criteria (Hansson 1996):

The former of the two criteria is central to the concerns of the philosophy of science. Its precise meaning has been the subject of important controversies among philosophers, to be discussed below in Section 4. The second criterion has been less discussed by philosophers, but it needs careful treatment not least since many discussions of pseudoscience (in and out of philosophy) have been confused due to insufficient attention to it. Proponents of pseudoscience often attempt to mimic science by arranging conferences, journals, and associations that share many of the superficial characteristics of science, but do not satisfy its quality criteria. Naomi Oreskes (2019) called this phenomenon “facsimile science”. Blancke and coworkers (2017) called it “cultural mimicry of science”.

An immediate problem with the definition based on (1) and (2) is that it is too wide. There are phenomena that satisfy both criteria but are not commonly called pseudoscientific. One of the clearest examples of this is fraud in science. This is a practice that has a high degree of scientific pretence and yet does not comply with science, thus satisfying both criteria. Nevertheless, fraud in otherwise legitimate branches of science is seldom if ever called “pseudoscience”. The reason for this can be clarified with the following hypothetical examples (Hansson 1996).

Case 1 : A biochemist performs an experiment that she interprets as showing that a particular protein has an essential role in muscle contraction. There is a consensus among her colleagues that the result is a mere artefact, due to experimental error.

Case 2 : A biochemist goes on performing one sloppy experiment after the other. She consistently interprets them as showing that a particular protein has a role in muscle contraction not accepted by other scientists.

Case 3 : A biochemist performs various sloppy experiments in different areas. One is the experiment referred to in case 1. Much of her work is of the same quality. She does not propagate any particular unorthodox theory.

According to common usage, 1 and 3 are regarded as cases of bad science, and only 2 as a case of pseudoscience. What is present in case 2, but absent in the other two, is a deviant doctrine . Isolated breaches of the requirements of science are not commonly regarded as pseudoscientific. Pseudoscience, as it is commonly conceived, involves a sustained effort to promote standpoints different from those that have scientific legitimacy at the time.

This explains why fraud in science is not usually regarded as pseudoscientific. Such practices are not in general associated with a deviant or unorthodox doctrine. To the contrary, the fraudulent scientist is usually anxious that her results be in conformity with the predictions of established scientific theories. Deviations from these would lead to a much higher risk of disclosure.

The term “science” has both an individuated and an unindividuated sense. In the individuated sense, biochemistry and astronomy are different sciences, one of which includes studies of muscle proteins and the other studies of supernovae. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines this sense of science as “a particular branch of knowledge or study; a recognized department of learning”. In the unindividuated sense, the study of muscle proteins and that of supernovae are parts of “one and the same” science. In the words of the OED, unindividuated science is “the kind of knowledge or intellectual activity of which the various ‘sciences‘ are examples”.

Pseudoscience is an antithesis of science in the individuated rather than the unindividuated sense. There is no unified corpus of pseudoscience corresponding to the corpus of science. For a phenomenon to be pseudoscientific, it must belong to one or the other of the particular pseudosciences. In order to accommodate this feature, the above definition can be modified by replacing (2) by the following (Hansson 1996):

Most philosophers of science, and most scientists, prefer to regard science as constituted by methods of inquiry rather than by particular doctrines. There is an obvious tension between (2′) and this conventional view of science. This, however, may be as it should since pseudoscience often involves a representation of science as a closed and finished doctrine rather than as a methodology for open-ended inquiry.

Sometimes the term “pseudoscience” is used in a wider sense than that which is captured in the definition constituted of (1) and (2′). Contrary to (2′), doctrines that conflict with science are sometimes called “pseudoscientific” in spite of not being advanced as scientific. Hence, Grove (1985, 219) included among the pseudoscientific doctrines those that “purport to offer alternative accounts to those of science or claim to explain what science cannot explain.” Similarly, Lugg (1987, 227–228) maintained that “the clairvoyant’s predictions are pseudoscientific whether or not they are correct”, despite the fact that most clairvoyants do not profess to be practitioners of science. In this sense, pseudoscience is assumed to include not only doctrines contrary to science proclaimed to be scientific but doctrines contrary to science tout court, whether or not they are put forward in the name of science. Arguably, the crucial issue is not whether something is called “science” but whether it is claimed to have the function of science, namely to provide the most reliable information about its subject-matter. To cover this wider sense of pseudoscience, (2′) can be modified as follows (Hansson 1996, 2013):

Common usage seems to vacillate between the definitions (1)+(2′) and (1)+(2″); and this in an interesting way: In their comments on the meaning of the term, critics of pseudoscience tend to endorse a definition close to (1)+(2′), but their actual usage is often closer to (1)+(2″).

The following examples serve to illustrate the difference between the two definitions and also to clarify why clause (1) is needed:

- A creationist book gives a correct account of the structure of DNA.

- An otherwise reliable chemistry book gives an incorrect account of the structure of DNA.

- A creationist book denies that the human species shares common ancestors with other primates.

- A preacher who denies that science can be trusted also denies that the human species shares common ancestors with other primates.

(a) does not satisfy (1), and is therefore not pseudoscientific on either account. (b) satisfies (1) but neither (2′) nor (2″) and is therefore not pseudoscientific on either account. (c) satisfies all three criteria, (1), (2′), and (2″), and is therefore pseudoscientific on both accounts. Finally, (d) satisfies (1) and (2″) and is therefore pseudoscientific according to (1)+(2″) but not according to (1)+(2′). As the last two examples illustrate, pseudoscience and anti-science are sometimes difficult to distinguish. Promoters of some pseudosciences (notably homeopathy) tend to be ambiguous between opposition to science and claims that they themselves represent the best science.

Various proposals have been put forward on exactly what elements in science or pseudoscience criteria of demarcation should be applied to. Proposals include that the demarcation should refer to a research program (Lakatos 1974a, 248–249), an epistemic field or cognitive discipline, i.e. a group of people with common knowledge aims, and their practices (Bunge 1982, 2001; Mahner 2007), a theory (Popper 1962, 1974), a practice (Lugg 1992; Morris 1987), a scientific problem or question (Siitonen 1984), and a particular inquiry (Kuhn 1974; Mayo 1996). It is probably fair to say that demarcation criteria can be meaningfully applied on each of these levels of description. A much more difficult problem is whether one of these levels is the fundamental level to which assessments on the other levels are reducible. However, it should be noted that appraisals on different levels may be interdefinable. For instance, it is not an unreasonable assumption that a pseudoscientific doctrine is one that contains pseudoscientific statements as its core or defining claims. Conversely, a pseudoscientific statement may be characterized in terms of being endorsed by a pseudoscientific doctrine but not by legitimate scientific accounts of the same subject area.

Derksen (1993) differs from most other writers on the subject in placing the emphasis in demarcation on the pseudoscientist, i.e. the individual person conducting pseudoscience. His major argument for this is that pseudoscience has scientific pretensions, and such pretensions are associated with a person, not a theory, practice or entire field. However, as was noted by Settle (1971), it is the rationality and critical attitude built into institutions, rather than the personal intellectual traits of individuals, that distinguishes science from non-scientific practices such as magic. The individual practitioner of magic in a pre-literate society is not necessarily less rational than the individual scientist in modern Western society. What she lacks is an intellectual environment of collective rationality and mutual criticism. “It is almost a fallacy of division to insist on each individual scientist being critically-minded” (Settle 1971, 174).

Some authors have maintained that the demarcation between science and pseudoscience must be timeless. If this were true, then it would be contradictory to label something as pseudoscience at one but not another point in time. Hence, after showing that creationism is in some respects similar to some doctrines from the early 18th century, one author maintained that “if such an activity was describable as science then, there is a cause for describing it as science now” (Dolby 1987, 207). This argument is based on a fundamental misconception of science. It is an essential feature of science that it methodically strives for improvement through empirical testing, intellectual criticism, and the exploration of new terrain. A standpoint or theory cannot be scientific unless it relates adequately to this process of improvement, which means as a minimum that well-founded rejections of previous scientific standpoints are accepted. The practical demarcation of science cannot be timeless, for the simple reason that science itself is not timeless.

Nevertheless, the mutability of science is one of the factors that renders the demarcation between science and pseudoscience difficult. Derksen (1993, 19) rightly pointed out three major reasons why demarcation is sometimes difficult: science changes over time, science is heterogenous, and established science itself is not free of the defects characteristic of pseudoscience.

4. Alternative demarcation criteria

Philosophical discussions on the demarcation of pseudoscience have usually focused on the normative issue, i.e. the missing scientific quality of pseudoscience (rather than on its attempt to mimic science. One option is to base the demarcation on the fundamental function that science shares with other fact-finding processes, namely to provide us with the most reliable information about its subject-matter that is currently available. This could lead to the specification of critierion (1) from Section 3.2 as follows:

This definition has the advantages of (i) being applicable across disciplines with highly different methodologies and (ii) allowing for a statement to be pseudoscientific at present although it was not so in an earlier period (or, although less commonly, the other way around). (Hansson 2013) At the same time it removes the practical determination whether a statement or doctrine is pseudoscientific from the purview of armchair philosophy to that of scientists specialized in the subject-matter that the statement or doctrine relates to. Philosophers have usually opted for demarcation criteria that appear not to require specialized knowledge in the pertinent subject area.

Around 1930, the logical positivists of the Vienna Circle developed various verificationist approaches to science. The basic idea was that a scientific statement could be distinguished from a metaphysical statement by being at least in principle possible to verify. This standpoint was associated with the view that the meaning of a proposition is its method of verification (see the section on Verificationism in the entry on the Vienna Circle ). This proposal has often been included in accounts of the demarcation between science and pseudoscience. However, this is not historically quite accurate since the verificationist proposals had the aim of solving a distinctly different demarcation problem, namely that between science and metaphysics.

Karl Popper described the demarcation problem as the “key to most of the fundamental problems in the philosophy of science” (Popper 1962, 42). He rejected verifiability as a criterion for a scientific theory or hypothesis to be scientific, rather than pseudoscientific or metaphysical. Instead he proposed as a criterion that the theory be falsifiable, or more precisely that “statements or systems of statements, in order to be ranked as scientific, must be capable of conflicting with possible, or conceivable observations” (Popper 1962, 39).

Popper presented this proposal as a way to draw the line between statements belonging to the empirical sciences and “all other statements – whether they are of a religious or of a metaphysical character, or simply pseudoscientific” (Popper 1962, 39; cf. Popper 1974, 981). This was both an alternative to the logical positivists’ verification criteria and a criterion for distinguishing between science and pseudoscience. Although Popper did not emphasize the distinction, these are of course two different issues (Bartley 1968). Popper conceded that metaphysical statements may be “far from meaningless” (1974, 978–979) but showed no such appreciation of pseudoscientific statements.

Popper’s demarcation criterion has been criticized both for excluding legitimate science (Hansson 2006) and for giving some pseudosciences the status of being scientific (Agassi 1991; Mahner 2007, 518–519). Strictly speaking, his criterion excludes the possibility that there can be a pseudoscientific claim that is refutable. According to Larry Laudan (1983, 121), it “has the untoward consequence of countenancing as ‘scientific’ every crank claim which makes ascertainably false assertions”. Astrology, rightly taken by Popper as an unusually clear example of a pseudoscience, has in fact been tested and thoroughly refuted (Culver and Ianna 1988; Carlson 1985). Similarly, the major threats to the scientific status of psychoanalysis, another of his major targets, do not come from claims that it is untestable but from claims that it has been tested and failed the tests.

Defenders of Popper have claimed that this criticism relies on an uncharitable interpretation of his ideas. They claim that he should not be interpreted as meaning that falsifiability is a sufficient condition for demarcating science. Some passages seem to suggest that he takes it as only a necessary condition (Feleppa 1990, 142). Other passages suggest that for a theory to be scientific, Popper requires (in addition to falsifiability) that energetic attempts are made to put the theory to test and that negative outcomes of the tests are accepted (Cioffi 1985, 14–16). A falsification-based demarcation criterion that includes these elements will avoid the most obvious counter-arguments to a criterion based on falsifiability alone.

However, in what seems to be his last statement of his position, Popper declared that falsifiability is a both necessary and a sufficient criterion. “A sentence (or a theory) is empirical-scientific if and only if it is falsifiable.” Furthermore, he emphasized that the falsifiability referred to here “only has to do with the logical structure of sentences and classes of sentences” (Popper [1989] 1994, 82). A (theoretical) sentence, he says, is falsifiable if and only if it logically contradicts some (empirical) sentence that describes a logically possible event that it would be logically possible to observe (Popper [1989] 1994, 83). A statement can be falsifiable in this sense although it is not in practice possible to falsify it. It would seem to follow from this interpretation that a statement’s status as scientific or non-scientific does not shift with time. On previous occasions he seems to have interpreted falsifiability differently, and maintained that “what was a metaphysical idea yesterday can become a testable scientific theory tomorrow; and this happens frequently” (Popper 1974, 981, cf. 984).

Logical falsifiability is a much weaker criterion than practical falsifiability. However, even logical falsifiability can create problems in practical demarcations. Popper once adopted the view that natural selection is not a proper scientific theory, arguing that it comes close to only saying that “survivors survive”, which is tautological. “Darwinism is not a testable scientific theory, but a metaphysical research program” (Popper 1976, 168). This statement has been criticized by evolutionary scientists who pointed out that it misrepresents evolution. The theory of natural selection has given rise to many predictions that have withstood tests both in field studies and in laboratory settings (Ruse 1977; 2000).

In a lecture in Darwin College in 1977, Popper retracted his previous view that the theory of natural selection is tautological. He now admitted that it is a testable theory although “difficult to test” (Popper 1978, 344). However, in spite of his well-argued recantation, his previous standpoint continues to be propagated in defiance of the accumulating evidence from empirical tests of natural selection.

Thomas Kuhn is one of many philosophers for whom Popper’s view on the demarcation problem was a starting-point for developing their own ideas. Kuhn criticized Popper for characterizing “the entire scientific enterprise in terms that apply only to its occasional revolutionary parts” (Kuhn 1974, 802). Popper’s focus on falsifications of theories led to a concentration on the rather rare instances when a whole theory is at stake. According to Kuhn, the way in which science works on such occasions cannot be used to characterize the entire scientific enterprise. Instead it is in “normal science”, the science that takes place between the unusual moments of scientific revolutions, that we find the characteristics by which science can be distinguished from other activities (Kuhn 1974, 801).

In normal science, the scientist’s activity consists in solving puzzles rather than testing fundamental theories. In puzzle-solving, current theory is accepted, and the puzzle is indeed defined in its terms. In Kuhn’s view, “it is normal science, in which Sir Karl’s sort of testing does not occur, rather than extraordinary science which most nearly distinguishes science from other enterprises”, and therefore a demarcation criterion must refer to the workings of normal science (Kuhn 1974, 802). Kuhn’s own demarcation criterion is the capability of puzzle-solving, which he sees as an essential characteristic of normal science.

Kuhn’s view of demarcation is most clearly expressed in his comparison of astronomy with astrology. Since antiquity, astronomy has been a puzzle-solving activity and therefore a science. If an astronomer’s prediction failed, then this was a puzzle that he could hope to solve for instance with more measurements or adjustments of the theory. In contrast, the astrologer had no such puzzles since in that discipline “particular failures did not give rise to research puzzles, for no man, however skilled, could make use of them in a constructive attempt to revise the astrological tradition” (Kuhn 1974, 804). Therefore, according to Kuhn, astrology has never been a science.

Popper disapproved thoroughly of Kuhn’s demarcation criterion. According to Popper, astrologers are engaged in puzzle solving, and consequently Kuhn’s criterion commits him to recognize astrology as a science. (Contrary to Kuhn, Popper defined puzzles as “minor problems which do not affect the routine”.) In his view Kuhn’s proposal leads to “the major disaster” of a “replacement of a rational criterion of science by a sociological one” (Popper 1974, 1146–1147).

Popper’s demarcation criterion concerns the logical structure of theories. Imre Lakatos described this criterion as “a rather stunning one. A theory may be scientific even if there is not a shred of evidence in its favour, and it may be pseudoscientific even if all the available evidence is in its favour. That is, the scientific or non-scientific character of a theory can be determined independently of the facts” (Lakatos 1981, 117).

Instead, Lakatos (1970; 1974a; 1974b; 1981) proposed a modification of Popper’s criterion that he called “sophisticated (methodological) falsificationism”. On this view, the demarcation criterion should not be applied to an isolated hypothesis or theory, but rather to a whole research program that is characterized by a series of theories successively replacing each other. In his view, a research program is progressive if the new theories make surprising predictions that are confirmed. In contrast, a degenerating research programme is characterized by theories being fabricated only in order to accommodate known facts. Progress in science is only possible if a research program satisfies the minimum requirement that each new theory that is developed in the program has a larger empirical content than its predecessor. If a research program does not satisfy this requirement, then it is pseudoscientific.

According to Paul Thagard (1978, 228), a theory or discipline is pseudoscientific if it satisfies two criteria. One of these is that the theory fails to progress, and the other that “the community of practitioners makes little attempt to develop the theory towards solutions of the problems, shows no concern for attempts to evaluate the theory in relation to others, and is selective in considering confirmations and disconfirmations”. A major difference between this approach and that of Lakatos is that Lakatos would classify a nonprogressive discipline as pseudoscientific even if its practitioners work hard to improve it and turn it into a progressive discipline. (In later work, Thagard has abandoned this approach and instead promoted a form of multi-criterial demarcation (Thagard 1988, 157-173).)

In a somewhat similar vein, Daniel Rothbart (1990) emphasized the distinction between the standards to be used when testing a theory and those to be used when determining whether a theory should at all be tested. The latter, the eligibility criteria, include that the theory should encapsulate the explanatory success of its rival, and that it should yield testable implications that are inconsistent with those of the rival. According to Rothbart, a theory is unscientific if it is not testworthy in this sense.

George Reisch proposed that demarcation could be based on the requirement that a scientific discipline be adequately integrated into the other sciences. The various scientific disciplines have strong interconnections that are based on methodology, theory, similarity of models etc. Creationism, for instance, is not scientific because its basic principles and beliefs are incompatible with those that connect and unify the sciences. More generally speaking, says Reisch, an epistemic field is pseudoscientific if it cannot be incorporated into the existing network of established sciences (Reisch 1998; cf. Bunge 1982, 379).

Paul Hoyninengen-Huene (2013) identifies science with systematic knowledge, and proposes that systematicity can be used as a demarcation criterion. However as shown by Naomi Oreskes, this is a problematic criterion, not least since some pseudosciences seem to satisfy it (Oreskes 2019).

A different approach, namely to base demarcation criteria on the value base of science, was proposed by sociologist Robert K. Merton ([1942] 1973). According to Merton, science is characterized by an “ethos”, i.e. spirit, that can be summarized as four sets of institutional imperatives. The first of these, universalism , asserts that whatever their origins, truth claims should be subjected to preestablished, impersonal criteria. This implies that the acceptance or rejection of claims should not depend on the personal or social qualities of their protagonists.

The second imperative, communism , says that the substantive findings of science are the products of social collaboration and therefore belong to the community, rather than being owned by individuals or groups. This is, as Merton pointed out, incompatible with patents that reserve exclusive rights of use to inventors and discoverers. The term “communism” is somewhat infelicitous; “communality” probably captures better what Merton aimed at.

His third imperative, disinterestedness , imposes a pattern of institutional control that is intended to curb the effects of personal or ideological motives that individual scientists may have. The fourth imperative, organized scepticism , implies that science allows detached scrutiny of beliefs that are dearly held by other institutions. This is what sometimes brings science into conflicts with religions and ideologies.

Merton described these criteria as belonging to the sociology of science, and thus as empirical statements about norms in actual science rather than normative statements about how science should be conducted (Merton [1942] 1973, 268). His criteria have often been dismissed by sociologists as oversimplified, and they have only had limited influence in philosophical discussions on the demarcation issue (Dolby 1987; Ruse 2000). Their potential in the latter context does not seem to have been sufficiently explored.

Popper’s method of demarcation consists essentially of the single criterion of falsifiability (although some authors have wanted to combine it with the additional criteria that tests are actually performed and their outcomes respected, see Section 4.2). Most of the other criteria discussed above are similarly mono-criterial, of course with Merton’s proposal as a major exception.

Most authors who have proposed demarcation criteria have instead put forward a list of such criteria. A large number of lists have been published that consist of (usually 5–10) criteria that can be used in combination to identify a pseudoscience or pseudoscientific practice. This includes lists by Langmuir ([1953] 1989), Gruenberger (1964), Dutch (1982), Bunge (1982), Radner and Radner (1982), Kitcher (1982, 30–54), Grove (1985), Thagard (1988, 157–173), Glymour and Stalker (1990), Derksen (1993, 2001), Vollmer (1993), Ruse (1996, 300–306) and Mahner (2007). Many of the criteria that appear on such lists relate closely to criteria discussed above in Sections 4.2 and 4.4. One such list reads as follows:

- Belief in authority : It is contended that some person or persons have a special ability to determine what is true or false. Others have to accept their judgments.

- Unrepeatable experiments : Reliance is put on experiments that cannot be repeated by others with the same outcome.

- Handpicked examples : Handpicked examples are used although they are not representative of the general category that the investigation refers to.

- Unwillingness to test : A theory is not tested although it is possible to test it.

- Disregard of refuting information : Observations or experiments that conflict with a theory are neglected.

- Built-in subterfuge : The testing of a theory is so arranged that the theory can only be confirmed, never disconfirmed, by the outcome.

- Explanations are abandoned without replacement . Tenable explanations are given up without being replaced, so that the new theory leaves much more unexplained than the previous one.

Some of the authors who have proposed multicriterial demarcations have defended this approach as being superior to any mono-criterial demarcation. Hence, Bunge (1982, 372) asserted that many philosophers have failed to provide an adequate definition of science since they have presupposed that a single attribute will do; in his view the combination of several criteria is needed. Dupré (1993, 242) proposed that science is best understood as a Wittgensteinian family resemblance concept. This would mean that there is a set of features that are characteristic of science, but although every part of science will have some of these features, we should not expect any part of science to have all of them. Irzik and Nola (2011) proposed the use of this approach in science education.

However, a multicriterial definition of science is not needed to justify a multicriterial account of how pseudoscience deviates from science. Even if science can be characterized by a single defining characteristic, different pseudoscientific practices may deviate from science in widely divergent ways.

Some forms of pseudoscience have as their main objective the promotion of a particular theory of their own, whereas others are driven by a desire to fight down some scientific theory or branch of science. The former type of pseudoscience has been called pseudo-theory promotion , and the latter science denial(ism) (Hansson 2017). Pseudo-theory promotion is exemplified by homeopathy, astrology, and ancient astronaut theories. The term “denial” was first used about the pseudo-scientific claim that the Nazi holocaust never took place. The phrase “holocaust denial” was in use already in the early 1980s (Gleberzon 1983). The term “climate change denial” became common around 2005 (e.g. Williams 2005). Other forms of science denial are relativity theory denial, tobacco disease denial, hiv denialism, and vaccination denialism.

Many forms of pseudoscience combine pseudo-theory promotion with science denialism. For instance, creationism and its skeletal version “intelligent design” are constructed to support a fundamentalist interpretation of Genesis. However, as practiced today, creationism has a strong focus on the repudiation of evolution, and it is therefore predominantly a form of science denialism.

The most prominent difference between pseudo-theory promotion and science denial is their different attitudes to conflicts with established science. Science denialism usually proceeds by producing false controversies with legitimate science, i.e. claims that there is a scientific controversy when there is in fact none. This is an old strategy, applied already in the 1930s by relativity theory deniers (Wazeck 2009, 268–269). It has been much used by tobacco disease deniers sponsored by the tobacco industry (Oreskes and Conway 2010; Dunlap and Jacques 2013), and it is currently employed by climate science denialists (Boykoff and Boykoff 2004; Boykoff 2008). However, whereas the fabrication of fake controversies is a standard tool in science denial, it is seldom if ever used in pseudo-theory promotion. To the contrary, advocates of pseudosciences such as astrology and homeopathy tend to describe their theories as conformable to mainstream science.

6. Some related terms

The term scepticism (skepticism) has at least three distinct usages that are relevant for the discussion on pseudoscience. First, scepticism is a philosophical method that proceeds by casting doubt on claims usually taken to be trivially true, such as the existence of the external world. This has been, and still is, a highly useful method for investigating the justification of what we in practice consider to be certain beliefs. Secondly, criticism of pseudoscience is often called scepticism. This is the term most commonly used by organisations devoted to the disclosure of pseudoscience. Thirdly, opposition to the scientific consensus in specific areas is sometimes called scepticism. For instance, climate science deniers often call themselves “climate sceptics”.

To avoid confusion, the first of these notions can be specified as “philosophical scepticism”, the second as “scientific scepticism” or “defence of science”, and the third as “science denial(ism)”. Adherents of the first two forms of scepticism can be called “philosophical sceptics”, respectively “science defenders”. Adherents of the third form can be called “science deniers” or “science denialists”. Torcello (2016) proposed the term “pseudoscepticism” for so-called climate scepticism.

Unwillingness to accept strongly supported factual statements is a traditional criterion of pseudoscience. (See for instance item 5 on the list of seven criteria cited in Section 4.6.) The term “fact resistance” or “resistance to facts” was used already in the 1990s, for instance by Arthur Krystal (1999, p. 8), who complained about a “growing resistance to facts”, consisting in people being “simply unrepentant about not knowing things that do not reflect their interests”. The term “fact resistance” can refer to unwillingness to accept well-supported factual claims whether or not that support originates in science. It is particularly useful in relation to fact-finding practices that are not parts of science. (Cf. Section 2.)

Generally speaking, conspiracy theories are theories according to which there exists some type of secret collusion for any type of purpose. In practice, the term mostly refers to implausible such theories, used to explain social facts that have other, considerably more plausible explanations. Many pseudosciences are connected with conspiracy theories. For instance, one of the difficulties facing anti-vaccinationists is that they have to explain the overwhelming consensus among medical experts that vaccines are efficient. This is often done by claims of a conspiracy:

At the heart of the anti-vaccine conspiracy movement [lies] the argument that large pharmaceutical companies and governments are covering up information about vaccines to meet their own sinister objectives. According to the most popular theories, pharmaceutical companies stand to make such healthy profits from vaccines that they bribe researchers to fake their data, cover up evidence of the harmful side effects of vaccines, and inflate statistics on vaccine efficacy. (Jolley and Douglas 2014)

Conspiracy theories have peculiar epistemic characteristics that contribute to their pervasiveness. (Keeley 1999) In particular, they are often associated with a type of circular reasoning that allows evidence against the conspiracy to be interpreted as evidence for it.

The term “bullshit” was introduced into philosophy by Harry Frankfurt, who first discussed it in a 1986 essay ( Raritan Quarterly Review ) and developed the discussion into a book (2005). Frankfurt used the term to describe a type of falsehood that does not amount to lying. A person who lies deliberately chooses not to tell the truth, whereas a person who utters bullshit is not interested in whether what (s)he says is true or false, only in its suitability for his or her purpose. Moberger (2020) has proposed that pseudoscience should be seen as a special case of bullshit, understood as “a culpable lack of epistemic conscientiousness”.

Epistemic relativism is a term with many meanings; the meaning most relevant in discussions on pseudoscience is denial of the common assumption that there is intersubjective truth in scientific matters, which scientists can and should try to approach. Epistemic relativists claim that (natural) science has no special claim to knowledge, but should be seen “as ordinary social constructions or as derived from interests, political-economic relations, class structure, socially defined constraints on discourse, styles of persuasion, and so on” (Buttel and Taylor 1992, 220). Such ideas have been promoted under different names, including “social constructivism”, the “strong programme”, “deconstructionism”, and “postmodernism”. The distinction between science and pseudoscience has no obvious role in epistemic relativism. Some academic epistemic relativists have actively contributed to the promotion of doctrines such as AIDS denial, vaccination denial, creationism, and climate science denial (Hansson 2020, Pennock 2010). However, the connection between epistemic relativism and pseudoscience is controversial. Some proponents of epistemic relativism have maintained that that relativism “is almost always more useful to the side with less scientific credibility or cognitive authority” (Scott et al. 1990, 490). Others have denied that epistemic relativism facilitates or encourages standpoints such as denial of anthropogenic climate change or other environmental problems (Burningham and Cooper 1999, 306).

Kuhn observed that although his own and Popper’s criteria of demarcation are profoundly different, they lead to essentially the same conclusions on what should be counted as science respectively pseudoscience (Kuhn 1974, 803). This convergence of theoretically divergent demarcation criteria is a quite general phenomenon. Philosophers and other theoreticians of science differ widely in their views on what science is. Nevertheless, there is virtual unanimity in the community of knowledge disciplines on most particular issues of demarcation. There is widespread agreement for instance that creationism, astrology, homeopathy, Kirlian photography, dowsing, ufology, ancient astronaut theory, Holocaust denialism, Velikovskian catastrophism, and climate change denialism are pseudosciences. There are a few points of controversy, for instance concerning the status of Freudian psychoanalysis, but the general picture is one of consensus rather than controversy in particular issues of demarcation.

It is in a sense paradoxical that so much agreement has been reached in particular issues in spite of almost complete disagreement on the general criteria that these judgments should presumably be based upon. This puzzle is a sure indication that there is still much important philosophical work to be done on the demarcation between science and pseudoscience.

Philosophical reflection on pseudoscience has brought forth other interesting problem areas in addition to the demarcation between science and pseudoscience. Examples include related demarcations such as that between science and religion, the relationship between science and reliable non-scientific knowledge (for instance everyday knowledge), the scope for justifiable simplifications in science education and popular science, the nature and justification of methodological naturalism in science (Boudry et al 2010), and the meaning or meaninglessness of the concept of a supernatural phenomenon. Several of these problem areas have as yet not received much philosophical attention.

- Agassi, Joseph, 1991. “Popper’s demarcation of science refuted”, Methodology and Science , 24: 1–7.

- Baigrie, B.S., 1988. “Siegel on the Rationality of Science”, Philosophy of Science , 55: 435–441.

- Bartley III, W. W., 1968. “Theories of demarcation between science and metaphysics”, pp. 40–64 in Imre Lakatos and Alan Musgrave (eds.), Problems in the Philosophy of Science, Proceedings of the International Colloquium in the Philosophy of Science, London 1965 (Volume 3), Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company.

- Blancke, Stefaan, Maarten Boudry and Massimo Pigliucci, 2017. “Why do irrational beliefs mimic science? The cultural evolution of pseudoscience”, Theoria , 83(1): 78–97.

- Boudry, Maarten, Stefaan Blancke, and Johan Braeckman, 2010. “How not to attack intelligent design creationism: Philosophical misconceptions about methodological naturalism.” Foundations of Science , 153: 227–244.

- Boykoff, M. T., 2008. “Lost in translation? United States television news coverage of anthropogenic climate change, 1995–2004”, Climatic Change , 86: 1–11.

- Boykoff, M. T. and J. M. Boykoff, 2004. “Balance as bias: global warming and the U.S. prestige press”, Global Environmental Change , 14: 125–136.

- Bunge, Mario, 1982. “Demarcating Science from Pseudoscience”, Fundamenta Scientiae , 3: 369–388.

- –––, 2001. “Diagnosing pseudoscience”, in Mario Bunge, Philosophy in Crisis. The Need for Reconstruction , Amherst, N.Y.; Prometheus Books, pp. 161–189.

- Burningham, K., and G. Cooper, 1999. “Being constructive: Social constructionism and the environment”, Sociology , 33(2): 297–316.

- Buttel, Frederick H. and Peter J. Taylor, 1992. “Environmental sociology and global environmental change: A critical assessment”, Society and Natural Resources , 5(3): 211–230.

- Carlson, Shawn, 1985. “A Double Blind Test of Astrology”, Nature , 318: 419–425.

- Cioffi, Frank, 1985. “Psychoanalysis, pseudoscience and testability”, pp 13–44 in Gregory Currie and Alan Musgrave, (eds.) Popper and the Human Sciences , Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

- Cook, John, Naomi Oreskes, Peter T. Doran, William RL Anderegg, Bart Verheggen, Ed W. Maibach, J. Stuart Carlton, et al., 2016. “Consensus on consensus: A synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming”, Environmental Research Letters , 11: 048002.

- Culver, Roger and Ianna, Philip, 1988. Astrology: True or False , Buffalo: Prometheus Books.

- Derksen, A.A., 1993. “The seven sins of pseudoscience”, Journal for General Philosophy of Science , 24: 17–42.