Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

12 Type 4: Proposal Argument

Proposal arguments.

Proposal arguments attempt to push for action of some kind. They answer the question “What should be done about it?”

In order to build up to a proposal, an argument needs to incorporate elements of definition argument, evaluation argument, and causal argument. First, we will need to define a problem or a situation that calls for action. Then we need to make an evaluation argument to convince readers that the problem is bad enough to be worth addressing. This will create a sense of urgency within the argument and inspire the audience to seek and adopt proposed action. In most cases, it will need to make causal arguments about the roots of the problem and the good effects of the proposed solution.

Below are some elements of proposal arguments. Together, these elements can help us create a sense of urgency about the need for action and confidence in your proposal as a solution.

Common elements of proposal arguments

Background on the problem, opportunity, or situation.

Often just after the introduction, the background section discusses what has brought about the need for the proposal—what problem, what opportunity exists for improving things, what the basic situation is. For example, management of a chain of daycare centers may need to ensure that all employees know CPR because of new state mandates requiring it, or an owner of pine timberland in eastern Oregon may want to make sure the land can produce saleable timber without destroying the environment.

While the named audience of the proposal may know the problem very well, writing the background section is useful in demonstrating our particular view of the problem. If we cannot assume readers know the problem, we will need to spend more time convincing them that the problem or opportunity exists and that it should be addressed. For a larger audience not familiar with the problem, this section can give detailed context.

Description of the proposed solution

Here we define the nature of what we are proposing so readers can see what is involved in the proposed action. For example, if we write an essay proposing to donate food scraps from restaurants to pig farms, we will need to define what will be considered food scraps. In another example, if we argue that organic produce is inherently healthier for consumers than non-organic produce, and we propose governmental subsidies to reduce the cost of organic produce, we will need to define “organic” and describe how much the government subsidies will be and which products or consumers will be eligible. See 7.2: Definition Arguments for strategies that can help us elaborate on our proposed solution so readers can envision it clearly.

If we have not already covered the proposal’s methods in the description, we may want to add this. How will we go about completing the proposed work? For example, in the above example about food scraps, we would want to describe and how the leftover food will be stored and delivered to the pig farms. Describing the methods shows the audience we have a sound, thoughtful approach to the project. It serves to demonstrate that we have the knowledge of the field to complete the project.

Feasibility of the project

A proposal argument needs to convince readers that the project can actually be accomplished. How can enough time, money, and will be found to make it happen? Have similar proposals been carried out successully in the past? For example, we might observe that according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Rutgers University runs a program that sends a ton of food scraps a day from its dining halls to a local farm. 1 If we describe how other efforts overcame obstacles, we will persuade readers that if they can succeed, this proposal can as well.

Benefits of the proposal

Most proposals discuss the advantages or benefits that will come from the solution proposed. Describing the benefits helps you win the audience to your side, so readers become more invested in adopting your proposed solution. In the food scraps example, we might emphasize that the Rutgers program, rather than costing more, led to $100,000 a year in savings because the dining halls no longer needed to pay to have the food scraps hauled away. We could calculate the predicted savings for our new proposed program as well.

In order to predict the positive effects of the proposal and show how implementing it will lead to good results, we will want to use causal arguments. The strategies in 7.5: Causal Arguments will be helpful here. This is a good time to refer back to the problem we identified early in the essay and show how the proposal will resolve that original problem.

Sample annotated proposal argument

The sample essay “Why We Should Open Our Borders” by student Laurent Wenjun Jiang can serve as an example. Annotations point out how Jiang uses several proposal argument strategies.

- Sample proposal essay “Why We Should Open Our Borders” in PDF with margin notes

- Sample proposal essay “Why We Should Open Our Borders” accessible version with notes in parentheses

Find a proposal argument that you strongly support. Browse news and opinion websites, or try The Conversation . Once you have chosen a proposal, read it closely and look for the elements discussed in this section. Do you find enough discussion of the background, methods, feasibility, and benefits of the proposal? Discuss at least one way in which you think the proposal could be revised to be even more convincing.

Works Cited

1 “Fact Sheet About the Food Scraps Diversion Program at Rutgers University.” Environmental Protection Agency, U.S . October 2009, https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-mana…ers-university . Accessed 12/10/2021.

Attributions

Parts of this section on proposal arguments are original content by Anna Mills and Darya Myers. Parts were adapted from Technical Writing, which was derived in turn by Annemarie Hamlin, Chris Rubio, and Michele DeSilva, Central Oregon Community College, from Online Technical Writing by David McMurrey – CC BY 4.0 .

Screen-Reader Accessible Annotated Proposal Argument

Format note: This version is accessible to screen reader users. For a more traditional visual format, see the PDF version of “Why We Should Open Our Borders” above.

Laurent Wenjun Jiang

Prof. Natalie Peterkin

July 25, 2020

Why We Should Open Our Borders

Refugees, inequalities, economic instabilities…the fact that we are bombarded by news on those topics every day is proof that we live in a world with lots of problems, and many of us suffer as a consequence. Nations have tried a variety of solutions, but the reality has not improved. Yet there exists a single easy measure that could solve almost all of the problems mentioned above: an open-border policy. The current border and immigration practices, including border controls and detention centers, are unjustified and counterproductive. (Note: The first body paragraph gives background on the problem, opportunity, or situation.) This paper discusses the refugee problem, the history of open-border policy, the refutations for the current border policies on philosophical and moral grounds, and the arguments why this open-border policy will work economically.

Refugees are a problem of worldwide concern. Recently the biggest wave of refugees came from Syria, which witnessed an eight-year-long civil war. In an interview, a Syrian refugee expresses deep sorrows regarding the loss of her home: “My brothers, sisters, uncles, neighbors, streets, the bread ovens, schools, children going to schools …we miss all of that, everything in Syria is precious to us” she says, with tears hovering in her eyes (Firpo). She also exposes the terrible living conditions there: “[W]e didn’t run away, Syria has become uninhabitable. Not even animals could live there. No power, no running water, no safety, and no security. You don’t know who to fight…even when you lock yourself away, you’re not safe…I was most scared of seeing my children die right in front of me” (Firpo). (Note: Moving refugee testimonies serve as evidence supporting the claim that their situation is one of great urgency.) As heart-breaking as it sounds, we should also know that this is only the tip of the iceberg: Gerhard Hoffstaedter, an anthropologist at the University of Queensland, states that there are around 70 million displaced people in developing countries, which is the highest recorded number since the 1950s, causing the United Nations to call this world issue “a crisis.” The leading nations in the world do not offer enough support to displaced people living in abject conditions. Refugees at the U.S.-Mexico border and in Southeast Asia and Australia are constantly kept in detention centers. Many nations do not comply with the provisions signed in the 1951 Refugee Convention and the succeeding 1967 Protocol; they treat the refugees only as those in passive need of simply humanitarian aids (Hoffstaedter). In this crisis, it is our common responsibility as members of an international community to help those who are in need.

Historically, the large-scale control of the mobility of people is a relatively new phenomenon worldwide. (Note: This body paragraph starts with a definition argument to show that the current trend is new. This argument later becomes support for the idea that open borders are possible.) In the modern era, border signifies “ever more restrictive immigration policies” at the same time grants “greater freedom of mobility to capital and commodities”, as defined in the editorial “Why No Borders.” This creates a contradictory ideology that could cause potential harm to those who need to migrate (Anderson, et al.). John Maynard Keynes dates the beginning of this process only back to World War I in the early 20th century. However, this trend did not become widespread until after World War II. According to a historical outline created by Christof Van Mol and Helga de Valk, due to the booming in the industrial production in northwestern Europe in the 1950s, the local workers were increasingly educated and gradually became whitecollar employers, leaving vacancies in blue-collar occupations (Mol and Valk).

Thus, those countries started recruiting immigrants from other parts of Europe and even North Africa: for example, Germany and France started seasonal working programs to attract immigrants (Mol and Valk). Because of the lack of job opportunities in the other parts of Europe and North Africa and the need for workers in the industrializing countries in Northern and Western Europe, “international migration was generally viewed positively because of its economic benefits, from the perspective of both the sending and the receiving countries” (Mol and Valk). This early migration pattern within Europe provides the basic model for the European Union that builds on the fundamental ideology of the free movements of goods and human resources. In recent days, the European Union has become one of the biggest multinational organizations, which can also serve as a successful example of this open-border ideology, at least on a regional scale.

Borders do not satisfy the needs of contemporary societies. From both philosophical and moral perspectives, restrictive border policies are not justified. First of all, borders divide and subjugate people. The editorial “Why No Borders” describes the border as being“thoroughly ideological” (Anderson, et al.). The authors argue that because border policies try to categorize people into “desirable and non-desirable” according to their skills, race, or social status, etc., they thus create an interplay between “subjects and subjectivities,” placing people into “new types of power relationship” (Anderson, et al.). This is what is identified as the ultimate cause of the divisions and inequalities between people.

Some fear that competition from immigrants would cause a reduction in the wages of local workers (Caplan). (Note: In this body paragraph, the author attempts to disprove the counterargument about a downside of open borders for local workers.) This is not an uncalled-for worry, but it is also a misunderstanding of the nature of the open-border policy. Nick Srnicek reasons that this kind of competition has already existed under the current trend of globalization, where workers in developed countries are already competing against those in developing countries that have cheaper labor. He argues, “Workers in rich countries are already losing, as companies eliminate good jobs and move their factories and offices elsewhere” (Srnicek). The border serves companies by making workers in the developing world stay where wages are low. Thus, “companies can freely exploit” cheap labor. In this sense, workers on both sides will be better off under an open-border policy (Srnicek). A recent study from the University of Wisconsin-Madison investigating the economic implications of immigration between rich and poor countries concluded that the benefits of an open-border policy far outweigh the cons and that “the real wage effects are small” (Kennan).

Although an open border could lead to minor reductions in the wages of local workers in developed countries, there is a simple solution. Since the labor market follows the economic law of supply, work supply and wages are inversely related, meaning that the lower the supply of labor, the more wages rise. (Note: This paragraph could be seen as a limit and a rebuttal because the open border would need to be combined with changes to labor laws in order to avoid a possible bad effect.) Nick Srnicek proposes, “a shortening of the workweek…would reduce the amount of work supplied, spread the work out more equally among everyone and give more power to workers … more free time to everyone” (Srnicek). Thus, although the open-border policy is not perfect, its downside is easy to address. (Note: The author does not investigate how much time, money, and will an open border policy would need; the argument remains mostly theoretical because it doesn’t address feasibility.)

As an expatriate myself, I can truly relate to this type of thinking. Due to a variety of the political, economic, and social limitations that I came across in my home country, I was not able to achieve self-actualization. In pursuit of a better education and a more free living environment, I went abroad and finally arrived in this country a few years ago. It was not until then that I gained a vision of my future. Now I am working in hopes that one day the vision could become reality. Sometimes I cannot help wondering what could happen if I was not so lucky to be where I am today. But at the same time, I am also conscious of the fact that there are also millions of people out there who cannot even conceive of what it is like to actualize their lives. (Note: The conclusion humanizes the possible benefits of the proposed solution.) I am sure that one of the mothers who escaped her war-torn home country with her family has the sole hope to witness her children growing up in a happy and free place, just like any mother in the world. I am sure that there is one little girl whose family fled her country in desperation who once studied so hard in school, dreaming of becoming the greatest scientist in the world. I am also sure that there is a young boy who survived persecutions and wishes to become a politician one day to make the world a better place for the downtrodden. Because of borders, these children can only dream of the things that many of us take for granted every day. We, as human beings, might be losing a great mother, great scientist, great politician, or just a great person who simply wishes for a better world. But everything could be otherwise. Change requires nothing but a minimal effort. With open borders, we can help people achieve their dreams.

Hoffstaedter, Gerhard. “There Are 70 Million Refugees in the World. Here Are 5 Solutions to the Problem.” The Conversation , 24 Mar. 2020, theconversation.com/there-are-70-million-refugees-in-the-world-here-are-5- solutions-to-the-problem-118920.

Anderson, Sharma. “Editorial: Why No Borders?” Refuge , vol. 26, no. 2, 2009, pp.5+. Centre for Refugee Studies, York University. Accessed July 26, 2020.

D, D. “Keynes, J. M., The economic consequences of the peace.” Ekonomisk tidskrift, vol. 22, no. 1, Basil Blackwell Ltd., etc, Jan. 1920, p. 15–. Accessed July 26, 2020.

Srnicek, Nick. “The US$100 Trillion Case for Open Borders.” The Conversation , 18 Feb. 2020, theconversation.com/the-us-100-trillion-case-for-open-borders-72595.

Caplan, Bryan. “Why Should We Restrict Immigration?” Cato Journal , vol. 32, no. 1, 2012, pp. 5-24. ProQuest , https://libris.mtsac.edu/login?url=https://search- proquest-com.libris.mtsac.edu/docview/921128626?accountid=12611.Accessed July 26, 2020.

Kennan, John. “Open Borders in the European Union and Beyond: Migration Flows and Labor Market Implications.” NBER Working Paper Series, 2017, www.nber.org/papers/w23048.pdf.

Firpo, Matthew K., director. Refuge . 2016. The Refuge Project, www.refugeproject.co/watch.

Van Mol, Cristof, and Helga de Valk. “Migration and Immigrants in Europe: A Historical and Demographic Perspective.” Integration Processes and Policies in Europe , edited by Blanca Garcés-Mascareñas and Rinus Penninx, 2016, IMISCOE Research Series, pp. 33-55.

Attribution

This sample essay was written by Laurent Wenjun Jiang and edited and annotated by Natalie Peterkin. Licensed CC BY-NC 4.0 .

Chapter Attribution

This chapter is from “Forming a Research-Based Argument” in in How Arguments Work: A Guide to Writing and Analyzing Texts in College by Anna Mills under a CC BY-NC 4.0 license.

Upping Your Argument and Research Game Copyright © 2022 by Liona Burnham is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Order now 1(888)585-0586 1(888)216-9741

Proposal Argument Essay: An In-Depth Guide

Throughout your academic career, you will come across various essay types, including proposal argument essays. Writing a proposal argument essay can be challenging, as it assumes persuading your audience to support your proposal using robust evidence and convincing arguments. Nevertheless, by adopting the right approach and guidance, you can learn how to write such a paper that wins over your audience. In this article, we offer a step-by-step guide that will walk you from understanding what such an assignment is to learning how to write a strong proposal argument essay effectively. So, let’s dive in.

Let’s Answer the Question: What is a Proposal Argument Essay?

A proposal argument essay is a specific kind of essay that involves presenting a problem and offering a solution how to address and handle that problem. The primary aim of this essay is to convince the readers to support your proposed solution and idea. The proposal can involve a policy change, a novel method or approach to solving a problem, or even introduction of a new product or service.

The key distinguishing feature of the proposal argument essay assignment from other persuasive essays is its focus on a particular proposal or solution to a certain problem. The aim of such a paper is not only to persuade your audience to accept your opinion or viewpoint but also to suggest a practical solution to a real-world issue.

Getting Started: Developing Proposal Argument Essay Outline

A proposal argument essay, just like any other essay, should include an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. However, the specific structure may vary depending on the assignment instructions given by your professor. Thus, creating an outline is always helpful. Below you can find a tentative outline for your task:

I. Introduction

- A. Background information

- B. Thesis statement

- C. Topicality of the issue

II. Problem

- A. Description of the problem

- B. Importance of resolving the problem

- C. Supporting evidence

III. Proposed Solution

- A. Description of proposed solution

- B. Advantages of the proposed solution

IV. Counterarguments

- A. Explanation of potential objections

- B. Refutation of counterarguments

V. Conclusion

- A. Restate thesis

- B. Recap main points

- C. Call to action

Introductory Section: The introduction should provide an overview of the issue and introduce the suggested resolution. Remember to develop a clear and succinct thesis statement, which is essential for effectively conveying the argument.

Issue Elaboration: In this section, you should delve deeper into the problem, discussing its causes and consequences.

Suggested Solution: In this section you should provide recommendations for resolving the issue. Your suggested solution must be specific, practical, and achievable. Remember to present supporting evidence for the proposed solution, which might include statistical data, research findings, or expert opinions.

Counterarguments: You should identify and address any potential objections to your proposal, ensuring that the proposal is well-rounded and comprehensive.

Concluding Remarks: The conclusion should recap the proposal and highlight its advantages, leaving a lasting impression on the readers that would encourage them to accept your viewpoint on the issue and agree with your solution.

Having learned the structure and tentative outline, let’s further review how to make a great proposal argument essay step by step.

How to Write a Proposal Argument Essay – A Step by Step Guide

To craft a compelling proposal argument essay, you will need to employ critical thinking, persuasive writing skills, and conduct thorough research. Follow this step-by-step guide to help you write a persuasive proposal argument essay.

- Select a Topic

The first step in writing a proposal argument essay is choosing the topic. Pick a topic that has the potential to make a difference. Also, make sure that your chosen topic is specific, feasible, and appealing to your audience. Yet mind, if you choose a topic you are passionate about, it will be easier for you to persuade your audience.

- Conduct Research

After selecting your topic, conduct in-depth research to gather information and evidence to support your proposal. Utilize various sources such as academic journals, books, authoritative websites, and interviews with experts. Remember to take notes and organize your research for easy reference while writing your essay.

- Develop an Outline

Creating an outline is a critical stage of writing process. It helps in organizing your thoughts and ideas, making it easier to write a clear, concise and logically-structured essay. You can use the tentative outline mentioned in the previous section and customize it to fit your topic and research.

- Create the Introduction

The introduction should capture the reader’s attention and offer a clear understanding of the problem and the proposed solution. Thesis statement should be included in the introduction and present your argument. Make your introduction clear, concise, and engaging.

- Write the Body Paragraphs

The body paragraphs should provide supporting evidence for your proposal. Use the information gathered during research to back up your argument and address any counterarguments or objections to your proposal. Utilize transitional words and sentences to ensure a smooth flow in the essay and enhance its comprehensibility.

- Compose the Conclusion

The conclusion should recap the main points of your proposal and its advantages. It must also leave an impression on the reader and encourage them to take action in support of your solution. Avoid introducing any new perspectives on the problem in the conclusion and ensure you restate your thesis statement.

- Revise and Edit

While writing your first draft, plan some time to revise and edit your essay later. Check for grammatical and spelling errors, ensure a smooth flow throughout the essay, and verify that the argument is clear and concise. Seek feedback from friends, family, or peers to ensure your essay is easy to ready and comprehensive.

Writing a Proposal Argument Essay in a Nutshell

Below are the described steps outlined in short statements:

- Choose a topic that excites you and may inflame passion in your readers.

- Conduct extensive research and find as much information as you can to support your arguments.

- Use credible and reliable sources, such as books, academic journals, and trustworthy websites.

- Write a clear and concise thesis statement that encapsulates your argument.

- Use evidence and examples to back up your argument.

- Address potential counterarguments and prepare refutation.

- Use transitions to ensure smooth and logical in your essay.

Our team has gathered several topics to help you get started and inspire you to develop a successful essay.

You might also find Research Proposal Essay Topics useful.

Topics for Proposal Argument Essay

Selecting a topic for your proposal argument essay is essential. It will determine the level of interest your audience has in reading your paper. Here are some ideas for proposal argument papers to consider:

- Should college tuition be free for students?

- Should weekly working hours be limited?

- Should governments impose higher taxes on fast food to encourage healthy eating?

- Should plastic bags be banned?

- Should smoking be banned in public places?

- Should parents be held responsible for obesity in their children?

- Should social media companies be held accountable for spreading fake news?

- Should schools adopt a four-day school week?

- Should governments lower the voting age to 16?

- Should all states cancel the death penalty?

In conclusion, a proposal argument essay goes beyond merely presenting an argument. You must propose a solution to a problem or issue and provide evidence to support it. By adopting the right approach, you can create a persuasive and captivating essay that convinces your readers and professor to embrace your proposed solution. If you need assistance, our academic writing company is here to provide you with a custom-written essay tailored to your specific requirements.

Get a Proposal Argument Paper for Sale

If you find it challenging to write your proposal argument essay, or simply lack the time to do it yourself, you can always seek assistance from our academic writing company. Our writers have extensive experience in writing various types of academic papers. They are well-versed in all formatting and citation styles and will ensure that your paper is appropriately structured and cited.

To order a proposal argument essay, click “Order now” and complete the order form. Be sure to provide all necessary details, including your topic, deadline, and any specific instructions from your professor. We will assign a writer who is best suited for your project and can deliver a high-quality essay that meets all your requirements. Don’t lose your chance to get writing assistance you need. Let us know the details of your assignment, and we will help you craft a paper that will earn you the best grades.

Payment Methods

- Accounting Essay

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- APA Essay Format

- Argumentative Essay

- Argumentative Essay Writing Tips

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Report

- Book Review

- Business Writing Services

- Business Report

- Capstone Project

- Chicago Writing Style

- Classification Essay

- Coalition Application Essay

- Comparative Essay

- Definition Essay

- Discussion Board Post Assistance

- Dissertation Abstract

- Dissertation Discussion Chapter

- Dissertation Introduction

- Dissertation Literature Review

- Dissertation Results Section

- Dissertations Writing Help

- Economics Essay

- English Essay

- Essay on Marketing

- Essay Rewriting Service

- Excel Exercises Help

- Formatting Services

- IB Extended Essay

- Good Essay Outline

- Grant Proposal

- Hypothesis Statement for a Dissertation

- Letter Writing

- Literary Analysis Writing

- Literature Essay Topics

- Literature Review

- Marketing Essay

- Methodology for a Dissertation

- Motivation Letter Writing

- Movie Critique

- Movie Review

- Paper Revision

- Poem Writing Help

- PowerPoint Presentation

- Online Test

- PPT Poster Writing Service

- Proofreading Service

- Questionnaire for Research Paper

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal Essay Topics

- Response Essay

- Resume Writing Tips

- Scholarship Essay

- Thesis Paper

- Thesis Proposal Example!

- Turabian Style

- Turabian Style Citation

- What Is a Proposal Argument?

- Movie Adaptation of the Shakespeare’s Book Romeo and Juliet

- Personal Leadership Reflective Paper

- Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Discourse Community

- Tesla Motors

- Richard Weston Case

- Assessing Post Injury Intellectual Ability

- Cinema Leisure

- The Trauma of Physical Abuse

- Dance Culture

- IT Computer Software

- Final Project on Pepsi Co. Strategic Plan

- Career Research Report on EBay and Amazon

- Scientific Method As Applied To Real Life Instances

- RR Analysis Paper

- Professional Development Plan

- Anxiety and Depression in Hospice Patients

- The Coca-Cola Company Human Resource Practices

- Flight Safety

- Media Coverage Analysis

- Hollywood Movie in UAE

- Is Technology and Social Media Taking Over?

- Importance of Social Class in our Society

- V for Vendetta

- How Spanx Became a Billion-Dollar Business Without Advertising

- Deinstitutionalization Movement

- Cultural Self-Analysis

- Accordion Family – Challenges of Today

- Symbolism in Fahrenheit 451

- Value and Drawbacks of Innovations in Limb Prosthetics

- Managing Information Systems

- Movie Family Assessment

- Strategic Environmental Assessment in South Australia

- Technology and Happiness

- Casinos as Part of Entertainment Industry

- TV Drama Series Analysis

- Western Culture and Its Artifacts

- Underage Drinking

- The Nature of Love in The Storm and As Good as it Gets

- Strategic Rewards

- Sociology Essay

- Service Learning Reflection

- Review of Music of the Heart

- Political Systems in Ancient Greece

- Philosophy of Nursing

- Organizational Structure in an Aircraft Maintenance Facility

- New Balance Market in the USA and Worldwide

Please note!

Some text in the modal.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

63 Proposal Argument Model

Proposal method.

from Introduction to College Writing at CNM

The proposal method of argument is used when there is a problematic situation, and you would like to offer a solution to the situation. The structure of the proposal method is similar to the other persuasive methods, but there are slight differences.

Introduce and define the nature of the problematic situation. Make sure to focus on the problem and its causes. This may seem simple, but many people focus solely on the effects of a problematic situation. By focusing on the actual problem, your readers will see your proposal as a solution to the problem. If you don’t, your readers might see your solution as a mere complaint.

Propose a solution, or a number of solutions, to the problem. Be specific about these solutions. If you have one solution, you may choose to break it into parts and spend a paragraph or so describing each part. If you have several solutions, you may instead choose to spend a paragraph on each scenario. Each additional solution will add both depth and length to your argument. But remember to stay focused. Added length does not always equal a better argument.

Describe the workability of the various solutions. There are a variety of ways that this could be done. With a single-solution paper you could break the feasibility down into short and long term goals and plans. With a multiple-solution essay, you may instead highlight the strengths and weaknesses of the individual solutions, and establish which would be the most successful, based on your original statement of the problem and its causes. Check out this source from Owlcation, where they give a chart of 12 Ways to Solve Problems in the middle of the page.

Summarize and conclude your proposal. Summarize your solutions, re-state how the solution or solutions would work to remedy the problematic situation, and you’re done.

More information on proposal arguments follows.

Proposal Arguments

from College Comp II

Key Concept

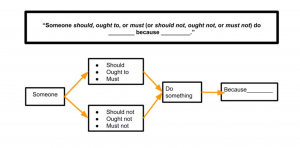

Proposal Argument: argues that something should, ought to, or must happen.

Proposal arguments–which propose that something should, ought to, or must happen–may be one of the most common kinds of arguments we encounter in our day-to-day lives; however, despite how often we find them, they can actually be rhetorically quite complex, perhaps because they appear deceptively simple to make. And this is exactly why we’re covering them last, since there are some very important subtleties to them.

The basic idea behind a proposal argument seems pretty straightforward: we state what we think should happen and then marshal evidence to support that proposal. Seems easy, right?

Let’s look at a hypothetical example:

Friend #1: “We should go see Movie X!” (Proposal claim)

Friend #2: “Okay, sounds good. I’m in!”

Friend #1 is making a proposal claim, arguing that both friends should go see a particular movie. In an abstract setting, this claim makes sense. However, Friend #2’s response seems pretty unlikely. If you were Friend #2, you’d probably have a few questions about why Friend #1 thinks you should go see this movie, right? Equally, you’d probably expect Friend #1 to provide at least some evidence (however scant) about why you should go see this movie. Perhaps, for example, you might want to know about the actors or the director. Maybe you’re curious about what critics are saying. Perhaps you’d like to know how long it is. Indeed, these are pretty typical things that your average person would want to know before they pay for their movie ticket. Maybe a more genuine conversation would look like this:

Friend #1: “Hey, did you know that Movie X in the theaters right now?” (Definition claim, establishing the existence of a condition.)

Friend #2: “Yeah, I did!”

Friend #1: “I’ve been reading that critics across the board are praising it. One critic whose opinion I really trust even said that it’s the best movie to come out all year.” (Evaluative claim, arguing that something is good.)

Friend #2: “Oh wow!”

Friend #1: “I think we should go see it!” (Proposal claim)

Note that in this second example, in order for Friend #1 to build a sound proposal argument, they have to first make several other claims–notably a definition claim, establishing the existence of a condition, following by an evaluative claim, arguing that the movie is good.

However, in less mundane examples, proposal arguments often begin by identifying a problem before proposing a solution to it. For instance, in recent years, there has been increased public awareness of the dangers of disposable plastic drinking straws, particularly focused on the dangers they cause to wildlife. Many stakeholders have proposed (and even implemented) a variety of different solutions. Starbucks, for example, redesigned their cold-drink cups so that they could stop giving customers obligatory straws with their beverages. Other establishments have switched to using straws that are made of paper, which is more biodegradable and therefore breaks down more easily. Other companies have started marketing washable, reusable plastic straws that can be reused over and over again. While a wide variety of solutions have been proposed (and while many of those proposals have even been enacted), what’s important to note is that these proposals were in response to what was identified as a problem–i.e. The wastefulness of disposable drinking straws.

For our purposes, however, here is how we can think about making proposal arguments:

1) Part of showing that a problem exists entails getting your reader to care enough to accept your proposed solution. To get the reader to care, you will need to work on their hearts as well as their minds by showing how the problem affects people (and, potentially, the reader specifically) and has important stakes.

2) You will need to show how your solution solves the problem (wholly or partially).

3) You will need to offer reasons for adopting your proposal. What values can you appeal to? Of the person or organization that needs to be convinced, how can you show that their interests are served? Always remember your audience. You don’t have to pretend that your solution is perfect or has neither costs nor any negative consequences; you should address these and convince your reader that despite them, your solution is about doing the right thing.

Recapping the main ideas behind Proposal Arguments:

- They argue that something should, ought to or must happen

- They don’t necessarily need to completely “solve” the problem; perhaps they only improve certain parts of it.

- Proposal claims are often the culmination of a string of other claims (definition, causal, etc.)

SAMPLE ESSAY

Here is an annotated Sample Proposal Essay .

Proposal Argument Model Copyright © 2020 by Liza Long; Amy Minervini; and Joel Gladd is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

4.2 Understanding and Composing Researched Arguments

[1] features of academic argument.

A clear and arguable position: You must present a reasonable argument for which both evidence and opposing or alternate views (counterarguments) exist. If few would disagree with you or you cannot find any evidence of a credible opposing view, you should consider rethinking and revising your position. A common error occurs when students try to present a statement of fact as an argumentative position. See the example below to learn how an idea or statement of fact can be developed and revised to become an effective thesis statement.

Example: Can a statement of fact evolve into a strong argumentative thesis statement?

When presenting your stance in an argumentative thesis statement, make sure you have stated an argument and not a simple statement of fact or an expository thesis statement like you would write for a report.

Statement of Fact: Some social media users develop unhealthy attitudes about their body image because of the constant portrayal of “ideal” body types they encounter online.

Expository Thesis Statement: Excessive social media use can cause unhealthy physical and mental conditions, particularly for girls and young women.

Overarching Point Argumentative Thesis Statement: Social media users should restrict themselves from exposure to unrealistic photos and from the portrayal of the “ideal” body type in order to prevent the development of significant health issues.

Argument Thesis Statement with Broadcasting of Discussion Points (Reasons/Minor Premises): Social media users should restrict themselves from the exposure to unrealistic photos and from the portrayal of the “ideal” body type in order to prevent harmful physical and mental health conditions linked with excessive social media use.

Proposal Solution Argument Thesis Statement: To help users moderate their exposure to unrealistic photos and “ideal” body types associated with harmful physical and mental health conditions, social media companies should provide users with informative public service announcements focused on healthy body image, display advertising promoting healthy body images and attitudes, and develop filters and messaging preferences to help end-users control their media stream content.

THESIS TIPS: When you compare the statements above, it is clear that a solid expository or argumentative thesis statement can contain factual information, but it must be a more complex idea that requires more development and evidence. The simple statement of fact above does not pass the “so what?” or “why?” test. When a thesis makes a claim about what a person or organization should do, think, or say , you are in the realm of argument. A useful strategy for developing a strong argumentative thesis statement is to answer this question: Who should do what and why ?

Necessary background information: You must present the issues, history, or larger contexts that provide the foundation for understanding your argument so that your readers (and you) can comprehend and see the urgency in the specific argument you are making. That is, you must acknowledge the current rhetorical context and provide a sense of the argument’s importance or exigence.

Viable reasons for your position: Your argument offers valid reasons for your position for which you provide relevant evidence. These reasons usually become the key points expressed in the topic sentences of your body paragraphs.

Convincing evidence: You present convincing, credible, relevant researched evidence including facts, statistics, surveys, expert testimony, anecdotes, and textual (i.e. such as history, reports, analyses) evidence. Think about the appeals you learned about in Composition 1: logos, ethos, pathos, Kairos, and Stasis when selecting your evidence. Varying evidence types will help you vary the rhetorical appeals and create a more balanced argument and greater audience appeal.

Appeals to readers’ values: Effective arguments appeal to readers’ emotions, values, wants, and needs. You might appeal to your readers’ sense of compassion or justice through a compelling narrative/anecdote. However, you will want to make sure that you have a balance between appeals to your reader’s values and presenting sound evidence to support those appeals and keep your argument from being driven solely by appeals to pathos.

A trustworthy tone: Through a confident tone, clear focus, knowledgeable voice, and well-researched, credible evidence, you can develop readers’ confidence in your credibility conveying to them that you possess internal ethos. This means that vague or shallow evidence and writing that is unedited and/or too informal in tone will reduce your audience’s trust in your argument resulting in a smaller chance that your readers will seriously consider the ideas you are presenting as valid.

Careful consideration of counterarguments: You present your awareness of opposing views about your argument to address the audience’s needs or expectations and to reinforce your internal ethos. If you do not address the “yeah, but” or “what about” in your readers’ or listeners’ minds, your argument may not be taken seriously and, even worse, your audience will think you have not researched your topic well enough or that you underestimate their existing knowledge. You should concede some points the opposition makes and refute others through evidence when you can.

Appropriate use of patterns of development to present your argument: Your argument reflects the application of the most effective patterns of development or rhetorical modes which you learned about in Composition 1 (i.e. exemplification, explanation, analysis, classification, comparison/contrast, definition, description, narration), with which to develop the content supporting your reasons.

Activating an Inquiry-based Mindset for Creating Arguments

Using a questioning heuristic [3] can help you generate an academic argument. Just as you pre-research a possible argument topic to see what others are saying about it or just bubble map or list to generate some ideas or list some research questions, you also need to “interrogate” the argument you are forming before you go too far with your research. In fact, working through these questions about the argument will help you identify holes in the argument you can address with specific research questions for your next round of rhetorical research.

QUESTIONING HEURISTIC FOR INVENTING AN ARGUMENT [4]

Questions are at the core of arguments. What matters is not just that you believe that what you have to say is true, but that you give others viable reasons to believe it as well—and also show them that you have considered the issue from multiple angles. To do that, build your argument out of the answers to the five questions a rational reader will expect answers to. In academic and professional writing, we tend to build arguments from the answers to these main questions:

- What do you want me to do or think?

- Why should I do or think that?

- How do I know that what you say is true?

- Why should I accept the reasons that support your claim?

- What about this other idea, fact, or consideration?

- How should you present your argument?

When you ask people to do or think something they otherwise would not, they quite naturally want to know why they should do so. In fact, people tend to ask the same questions. As you make a reasonable argument, you anticipate and respond to readers’ questions with a particular part of the argument:

- The answer to What do you want me to do or think? is your conclusion : “I conclude that you should do or think X.”

- The answer to Why should I do or think that? states your premise : “You should do or think X because . . .”

- The answer to How do I know that what you say is true? presents your support : “You can believe my reasons because they are supported by a thorough review of the available information and this carefully selected, credible evidence . . .”

- The answer to Why should I accept that your reasons support your claim? states your general principle of reasoning, called a warrant : which is/are assumptions and/or values the author holds and possibly the audience holds as well: “My specific reason supports my specific claim because whenever this general condition is true, we can generally draw a conclusion like mine.” OR “I know people in my audience value the importance of X, just as I do.”

- The answer to What about this other idea, fact, or conclusion? acknowledges that your readers might see things differently and then responds to their counterarguments .

- The answer to How should you present your argument? leads to the point of view , organization , and tone that you should use when making your arguments.

As you have noticed, the answers to these questions involve knowing the particular vocabulary argumentation because these terms refer to specific parts of an argument. The remainder of this section will cover the terms referred to in the questions listed above as well as others that will help you better understand the building blocks of the argument.

Types of Arguments

Aristotelian argument.

Most likely sometime during your time in high school or your first semester of composition, you composed a simplified Aristotelian argument essay in which you researched a controversial issue and formed an argumentative position on the issue. You wrote an introduction leading into your thesis statement (major premise), provided two to three reasons as discussion points (minor premises) which became the focus of the essay’s body paragraphs. You also provided a counterargument presenting an opposing view and offered both a concession and refutation of that view.

Rogerian Argument

The Rogerian approach to argument is based on the work of Carl Rogers, one of the founders of Humanistic Psychology. Humanists are “concerned with the fullest growth of the individual in the areas of love, fulfillment, self-worth, and autonomy” [5] . In the field of learning and rhetoric, the “Rogerian” approach is focused on personal growth, developing a sense of personal fulfillment, and finding common ground with others. This concept of finding common ground with others who hold opposing views or perspectives is a contrast to the traditional Aristotelian argument as discussed above or the Toulmin argument which we will look at later.

A Rogerian argument presents the opposing view without bias or negative tone and finds subclaims or points within the opposition’s argument that have merit or align with your own position on the issue. If you understand the issue well enough and can authentically present two or more stances on the issue, you are demonstrating that you have brought an open mind to the issue and are trustworthy in presenting your own argument and the opposing view. That is, you will have validated your internal ethos to your audience. As you present the opposing argument and consider the supporting evidence, your goal is to work your way toward a common ground; that is, the reasons and/or evidence both sides can agree upon, at least to some degree. Even if you do not actually write or present a formal Rogerian Argument, working through an outline of the opposition’s case with an open mind for the purpose of finding common ground and determining where your arguments diverge will help you more effectively develop your own argument and present a counterargument that accurately represents the opposition’s views.

The Rogerian argument analysis expands your knowledge and understanding of an issue far beyond a simple pro/con understanding of the issue and can help you develop a more sophisticated, complex argument. Processing your argument through the filter of a Rogerian perspective could also help you avoid some argumentative pitfalls. For example, fully understanding and trying to find common ground with opposing views may help you prevent:

- Taking too hostile a position against an opposing argument, thus alienating your audience.

- Not acknowledging the values, wants, or needs the opposing argument fulfills for the members of your audience will result in you never addressing them yourself.

- Writing a weak, uniformed counterargument to your own argument leading to audience mistrust of your internal ethos.

Toulmin Argument

The Toulmin Argument, which you studied in Composition 1, was developed by philosopher, Stephen Toulmin. Toulmin is best known for his work on argumentation which moved argument out of classical logical reasoning based on syllogisms to what he termed “practical arguments” based on justification rather than abstract proofs. Key elements of the Toulmin Model are claims, grounds or evidence, rebuttals, warrants, backing, and qualifiers. Below is a recap of the main components of the Toulmin Model.

TOULMIN MODEL [6]

THE CLAIM: The claim or thesis must be very clear and concise because it sets up the entire paper. Questions that a good claim might answer are:

THE EVIDENCE: The next part of our argument and the most in-depth is the evidence that supports our claim. We are basically saying in our argument that the reader should agree with us because of XYZ where XYZ is the evidence. It is often said that the heart of any argument is the evidence. The key is to use evidence that is accurate, current, fair, or unbiased which makes it credible to support the claim. Also, the evidence has to be presented accurately because the reader is simply not going to believe you unless you are some form of subject matter expert, which you probably are not, so we need to have the experts speak for you.

THE REBUTTAL: This section usually contains two parts: (1) addresses the main opposing point of view to the writer’s position. This demonstrates that you understand what that position is and helps develop your own credibility as the writer. (2) After you discuss the opposing view, next you provide evidence that casts doubt on that view suggesting that the other position might not be correct. The evidence does not have to prove that the other side is completely wrong; it only needs to suggest that there may be some doubt with the point of view based upon the evidence you are offering.

THE WARRANT: This is the basic/common or underlying principle that links your claim, reason, and evidence. For example, let’s say that your claim was about the dangers of social media use by young adults; however, everyone may not care about social media use. Therefore, you want to connect the reason “why” to the claim by expressing a common or underlying principle that will help your audience understand how the reason and claim link. So, while some people may not care about social media use, most people would care about keeping young adults safe and away from danger because that is a natural instinct embedded in the human psyche . Warrants can come from principles that are shared at the societal level or within the field itself.

THE QUALIFIERS: This term refers to language and its use in making your claim. They are words used to acknowledge the limits of your position and keep you from creating a claim that overreaches. Including words that accomplish a sufficiently narrow claim suggests that you know that there are other possibilities or contingencies. One of the best ways to get your readers to walk away from your argument is blind arrogance.

The diagram below reflects the elements of Toulmin’s practical argument. The diagram illustrates how warrants and the back of warrants provide the connection between evidence and a conclusion. Warrants help contextualize a fact or link a fact to a conclusion. Creating a diagram such as this will help you create a solid basis on which to justify your argument. Probably the most important elements of the Toulmin model are the warrant and the backing. If you are not sure what warrant/s (shared audience knowledge, values, or assumption/s) link your evidence (grounds for the argument) to the conclusion, you may not be supporting your conclusion with the most effective evidence.

Other Types of Academic Arguments

Sometimes writing instructors assign specific types of arguments. These genre arguments have different purposes and will require different writing strategies. These purposes and strategies require writers to assume different roles. If assigned one of these arguments, you may find yourself investigating a cause, defining a term, evaluating a product, or solving a problem. You’ll still be arguing and using rhetorical principles to make these arguments, but you’ll need to consider your role as you compose your argument.

Causal Arguments

In a causal argument, a writer must argue about a problem or controversy’s cause. Causal arguments are difficult because most controversial issues have complicated causes. Many people also tend to believe in causes that correspond to their political beliefs. Consider the various explanations for school shootings. Some will insist the problem is the easy availability of firearms while others will insist that shooters are inspired by violent video games and entertainment. When making a causal argument, a writer should consider their biases and rely on evidence to support their claims.

In a causal argument, writers may be tempted by logical fallacies. For example, it’s important to remember that correlation is not equal to causation . If two events happen at the same time, that doesn’t necessarily mean that one event caused the other.

Definition Arguments

This type of argument may seem puzzling. How do we argue about a word’s definition? Isn’t that what dictionaries are for? For most definition arguments, the real argument isn’t the precise meaning of the word. Instead, the argument is about the implications of that definition and how the definition may be applied to specific situations. Consider the word “obscene.” One dictionary defines “obscene” as “offensive or disgusting by accepted standards of morality and decency.” A writer may want to argue that Playboy is obscene. Or that a recent controversial film is obscene. By making this kind of argument, the writer would suggest some course of action: the obscene material should be age-limited, should be condemned, or should be banned. In this kind of paper, the author would make claims about “accepted standards” and “offensive or disgusting” as they apply to the potentially obscene item.

Many popular arguments rely on definitions. Determining whether something is obscene or offensive is just one popular item. As part of the War on Terror, we’ve argued about the meaning of “torture” and its justification. Many death penalty arguments rely upon the terms “cruel and unusual punishment.” The Iraq war inspired many arguments about “just” and “unjust” wars, as did the Vietnam war did decades earlier.

Evaluation Arguments

You may be more familiar with evaluation arguments than you realize. If you’ve ever read a movie, restaurant, or other product review, you’ve read an evaluation argument. As online shopping and social media have expanded, you may have even written your own evaluation argument on Amazon, Google, or Yelp. A good evaluation argument will rely upon clear criteria. “Criteria” (singular “criterion”) are the conditions by which you make your evaluation; these conditions could be used to evaluate any thing that is in the same category. A restaurant review may be based upon the food quality, price, service, and ambiance of the restaurant. An evaluation should also consider the specific category of what’s being evaluated: one shouldn’t evaluate a local pub with the same criteria as a fine dining establishment. By establishing a narrow category, the writer can write a more accurate evaluation. While reviews are the most popular form of evaluation arguments, that is not the only place they are used. Evaluation arguments are useful for supporting or opposing public policies or proposed laws. A community may propose several solutions to deal with a school district’s budget woes. A teacher from that district may write a guest editorial arguing for the best policy, or write an article criticizing a poor choice.

Proposal Argument (Problem/Solution)

Proposal arguments require the writer to perform two tasks: argue that there is a problem, and then propose a solution to that problem. Usually, the problem will be a local problem. It is good to focus on a smaller community because national or global problems or much more complex; therefore, making them harder to successfully argue in the limited space of a college essay.

Proposals have two separate arguments. The first is the problem: it’s not enough to label an issue a problem; a writer must prove that the problem is severe to an audience. Take, for instance, the opioid crisis. A writer may need to convince community members who aren’t addicts why the crisis is a problem for their community; therefore, it is not enough to discuss how addiction hurts addicts. Showing how the community is harmed by the crime associated with addiction would be a better way to motivate a community to solve the problem.

The second argument is the solution. Explain what the solution is and how it solves the problem. A writer should establish that their solution is the best solution. The best solution is the cheapest solution that best addresses the problem. “Cheapest” here refers to more than monetary costs. While monetary costs are oftentimes a considerable factor, there are other costs like labor and change that may affect people physically, mentally, or emotionally. “Addressing the problem” is an acknowledgment that most proposals won’t completely solve a problem. The goal is a reasonable solution that eliminates most of the harm, or the most serious harm, caused by the problem. Perhaps the most difficult aspect of proposals is considering the unintended consequences of a solution. These can be positive or negative. Writers should ask “What happens next?” of their solutions.

[8] Structuring Argument in Your Paper

Now that we have looked at the different terms and styles of arguments, we need to start thinking about how these things come together in a paper because writing academic research papers is (more than likely) going to be a lot messier than this chapter, or any textbook, makes it seem.

In a traditional argument-based paper, the claim is generally stated in the thesis (often at the end of the introduction), with the reasons appearing as the topic sentences of body paragraphs. The content of the body paragraphs is then focused on providing the evidence that supports the topic sentences, ultimately supporting the claim. Such organization helps to ensure that the argument is always at the forefront of the writing, since it provides guideposts in key places to direct the reader’s attention to what the author wants to persuade him/her of. There may be occasions, though, when it is preferable to delay stating the claim until later.

In addition, regardless of what the reasons are that you plan to use to support your claim, they will not be equal in their strength/ability to do so. Realistically, the reasons will fall along a spectrum from strongest to weakest (note that “weakest” does not carry the traditional connotation of the word “weak”), so, when writing an argument-based paper, you will need to determine the best order in which to place your reasons. The most common suggestion for ordering is to place your weakest reasons in the middle of the paper, with your strongest appearing at the beginning and end. This approach makes sense in terms of wanting to show the reader early in the writing that your claim is backed by sound reasoning and to leave him/her with a final impression that your argument is solid. You also should consider the complexity of the reasons; if some of your ideas are more complicated to understand than others, you will need to strike a balance between strength and complexity in the structure to ensure that your reader is not only persuaded throughout the paper but also that he/she can fully understand the logical progression from one point to the next.

organizing reasons effectively

Imagine that you are assigned an argument paper that must focus on an education-related issue, with the audience consisting of your peers. You select as your claim the idea that all undergraduate writing courses that fulfill a general education requirement should include a tutor, who would attend all class meetings and assist students as needed. As you plan your paper, you decide to use the following reasons to support your claim:

- Students may be more comfortable seeking individualized help with their writing from a peer (advanced undergraduate student or graduate student) than their instructor.

- The tutor could provide valuable feedback to the instructor to assist him/her with teaching that students may be uncomfortable sharing or otherwise unable to do so.

- Student grades and retention would improve.

To support the first reason, your evidence consists of anecdotes from fellow students. To support the second and third reasons, your evidence consists of published research that suggests these benefits. In what order would you place the reasons in your paper, and why?

Media Attributions

- “Toulmin argumentation can be diagrammed as a conclusion established, more or less, on the basis of a fact supported by a warrant (with backing), and a possible rebuttal.” Image by Chaswick Chap, CC-BY-SA 3.0 © Chap Chiswick is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 4.2 (except where otherwise noted) is borrowed with minor edits and additions from Claim Your Voice in First Year Composition, Vol. 2 by Cynthia Kiefer and Serene Rock which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ↵

- Hillocks, G.,Jr. (2010). Teaching argument for critical thinking and writing: An introduction. English Journal, 99 (6), 24-32. https://www.proquest.com/docview/577286527/fulltextPDF/8F9B51E2B09B440EPQ/1?accountid=30550 ↵

- Definition : of or constituting an educational method in which learning takes place through discoveries that result from investigations made by the student ↵

- Borrowed with minor edits and additions from "Argument" by Kirsten DeVries which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License and published as part of Critical Reading, Critical Writing: A Handbook to Understanding College Composition, SP22 edition ↵

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). Humanistic psychology. In Encyclopaedia Britannica . https://www.britannica.com/science/humanistic-psychology ↵

- Borrowed with minor edits and additions from Writing and Rhetoric by Heather Hopkins Bowers, Anthony Ruggiero, and Jason Saphara which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ↵

- Borrowed with minor edits and additions from "Argument Genres" by Heather Hopkins Bowers, Anthony Ruggiero, and Jason Saphara which was published in Writing and Rhetoric, Colorado State University, Pueblo and is licensed under CC-BY 4.0. ↵

- The following section (except where otherwise noted) was borrowed with minor edits and additions from "Structure of Argument" by Karla Lyles and Jeanine Rauch provided by the University of Mississippi which is licensed under a CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike ↵

Composition 2: Research and Writing Copyright © by Brittany Seay is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

The goal of a research proposal is twofold: to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting research are governed by standards of the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, therefore, the guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to determine that the research problem has not been adequately addressed or has been answered ineffectively and, in so doing, become better at locating pertinent scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of conducting scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those findings. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your proposal is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to investigate.

- Why do you want to do the research? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of in-depth study. A successful research proposal must answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to conduct the research? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having difficulty formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here for strategies in developing a problem to study.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise . A research proposal must be focused and not be "all over the map" or diverge into unrelated tangents without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review . Proposals should be grounded in foundational research that lays a foundation for understanding the development and scope of the the topic and its relevance.

- Failure to delimit the contextual scope of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.]. As with any research paper, your proposed study must inform the reader how and in what ways the study will frame the problem.

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research . This is critical. In many workplace settings, the research proposal is a formal document intended to argue for why a study should be funded.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar . Although a research proposal does not represent a completed research study, there is still an expectation that it is well-written and follows the style and rules of good academic writing.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues . Your proposal should focus on only a few key research questions in order to support the argument that the research needs to be conducted. Minor issues, even if valid, can be mentioned but they should not dominate the overall narrative.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal. Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing most college-level academic papers, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. The text of proposals generally vary in length between ten and thirty-five pages, followed by the list of references. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like, "Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

Most proposals should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea based on a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and to be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in two to four paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that research problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Answer the "So What?" question by explaining why this is important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This is where you explain the scope and context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. It can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is most relevant in explaining the aims of your research.

To that end, while there are no prescribed rules for establishing the significance of your proposed study, you should attempt to address some or all of the following:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing; be sure to answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care?].

- Describe the major issues or problems examined by your research. This can be in the form of questions to be addressed. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain the methods you plan to use for conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Describe the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you plan to study, but what aspects of the research problem will be excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts, theories, or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while at the same time, demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methodological approaches they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, when stated, their recommendations. Also pay attention to any suggestions for further research.

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your proposed study in relation to the arguments put forth by other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically or chronologically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you review more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

NOTE: Do not shy away from challenging the conclusions made in prior research as a basis for supporting the need for your proposal. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. Highlighting the problematic conclusions strengthens your proposal. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

To help frame your proposal's review of prior research, consider the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.