Rhetorical Questions in Essays: 5 Things you should Know

Rhetorical questions can be useful in writing. So, why shouldn’t you use rhetorical questions in essays?

In this article, I outline 5 key reasons that explain the problem with rhetorical questions in essays.

Despite the value of rhetorical questions for engaging audiences, they mean trouble in your university papers. Teachers tend to hate them.

There are endless debates among students as to why or why not to use rhetorical questions. But, I’m here to tell you that – despite your (and my) protestations – the jury’s in. Many, many teachers hate rhetorical questions.

You’re therefore not doing yourself any favors in using them in your essays.

Rhetorical Question Examples

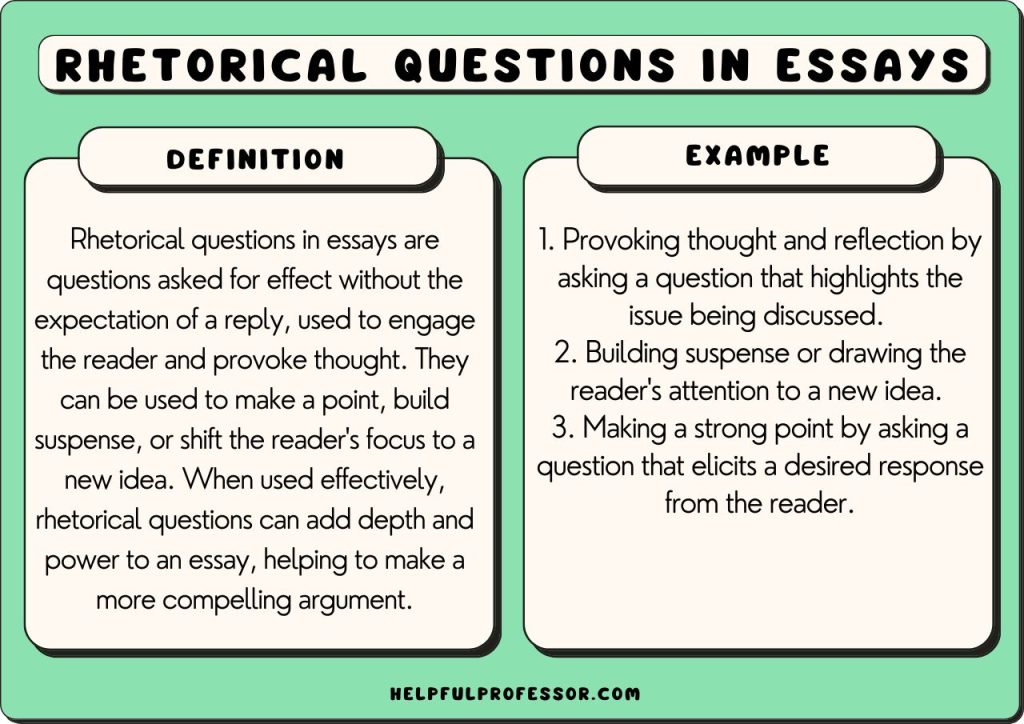

A rhetorical question is a type of metacommentary . It is a question whose purpose is to add creative flair to your writing. It is a way of adding style to your essay.

Rhetorical questions usually either have obvious answers, or no answers, or do not require an answer . Here are some examples:

- Are you seriously wearing that?

- Do you think I’m that gullible?

- What is the meaning of life?

- What would the walls say if they could speak?

I understand why people like to use rhetorical questions in introductions . You probably enjoy writing. You probably find rhetorical questions engaging, and you want to draw your marker in, engage them, and wow them with your knowledge.

1. Rhetorical Questions in Academic Writing: They Don’t belong.

Rhetorical questions are awesome … for blogs, diaries, and creative writing. They engage the audience and ask them to predict answers.

But, sorry, they suck for essays. Academic writing is not supposed to be creative writing .

Here’s the difference between academic writing and creative writing:

- Supposed to be read for enjoyment first and foremost.

- Can be flamboyant, extravagant, and creative.

- Can leave the reader in suspense.

- Can involve twists, turns, and surprises.

- Can be in the third or first person.

- Readers of creative writing read texts from beginning to end – without spoilers.

Rhetorical questions are designed to create a sense of suspense and flair. They, therefore, belong as a rhetorical device within creative writing genres.

Now, let’s look at academic writing:

- Supposed to be read for information and analysis of real-life ideas.

- Focused on fact-based information.

- Clearly structured and orderly.

- Usually written in the third person language only.

- Readers of academic writing scan the texts for answers, not questions.

Academic writing should never, ever leave the reader in suspense. Therefore, rhetorical questions have no place in academic writing.

Academic writing should be in the third person – and rhetorical questions are not quite in the third person. The rhetorical question appears as if you are talking directly to the reader. It is almost like writing in the first person – an obvious fatal error in the academic writing genre.

Your marker will be reading your work looking for answers , not questions. They will be rushed, have many papers to mark, and have a lot of work to do. They don’t want to be entertained. They want answers.

Therefore, academic writing needs to be straight to the point, never leave your reader unsure or uncertain, and always signpost key ideas in advance.

Here’s an analogy:

- When you came onto this post, you probably did not read everything from start to end. You probably read each sub-heading first, then came back to the top and started reading again. You weren’t interested in suspense or style. You wanted to find something out quickly and easily. I’m not saying this article you’re reading is ‘academic writing’ (it isn’t). But, what I am saying is that this text – like your essay – is designed to efficiently provide information first and foremost. I’m not telling you a story. You, like your teacher, are here for answers to a question. You are not here for a suspenseful story. Therefore, rhetorical questions don’t fit here.

I’ll repeat: rhetorical questions just don’t fit within academic writing genres.

2. Rhetorical Questions can come across as Passive

It’s not your place to ask a question. It’s your place to show your command of the content. Rhetorical questions are by definition passive: they ask of your reader to do the thinking, reflecting, and questioning for you.

Questions of any kind tend to give away a sense that you’re not quite sure of yourself. Imagine if the five points for this blog post were:

- Are they unprofessional?

- Are they passive?

- Are they seen as padding?

- Are they cliché?

- Do teachers hate them?

If the sub-headings of this post were in question format, you’d probably – rightly – return straight back to google and look for the next piece of advice on the topic. That’s because questions don’t assist your reader. Instead, they demand something from your reader .

Questions – rhetorical or otherwise – a position you as passive, unsure of yourself, and skirting around the point. So, avoid them.

3. Rhetorical Questions are seen as Padding

When a teacher reads a rhetorical question, they’re likely to think that the sentence was inserted to fill a word count more than anything else.

>>>RELATED ARTICLE: HOW TO MAKE AN ESSAY LONGER >>>RELATED ARTICLE: HOW TO MAKE AN ESSAY SHORTER

Rhetorical questions have a tendency to be written by students who are struggling to come to terms with an essay question. They’re well below word count and need to find an extra 15, 20, or 30 words here and there to hit that much-needed word count.

In order to do this, they fill space with rhetorical questions.

It’s a bit like going into an interview for a job. The interviewer asks you a really tough question and you need a moment to think up an answer. You pause briefly and mull over the question. You say it out loud to yourself again, and again, and again.

You do this for every question you ask. You end up answering every question they ask you with that same question, and then a brief pause.

Sure, you might come up with a good answer to your rhetorical question later on, but in the meantime, you have given the impression that you just don’t quite have command over your topic.

4. Rhetorical Questions are hard to get right

As a literary device, the rhetorical question is pretty difficult to execute well. In other words, only the best can get away with it.

The vast majority of the time, the rhetorical question falls on deaf ears. Teachers scoff, roll their eyes, and sigh just a little every time an essay begins with a rhetorical question.

The rhetorical question feels … a little ‘middle school’ – cliché writing by someone who hasn’t quite got a handle on things.

Let your knowledge of the content win you marks, not your creative flair. If your rhetorical question isn’t as good as you think it is, your marks are going to drop – big time.

5. Teachers Hate Rhetorical Questions in Essays

This one supplants all other reasons.

The fact is that there are enough teachers out there who hate rhetorical questions in essays that using them is a very risky move.

Believe me, I’ve spent enough time in faculty lounges to tell you this with quite some confidence. My opinion here doesn’t matter. The sheer amount of teachers who can’t stand rhetorical questions in essays rule them out entirely.

Whether I (or you) like it or not, rhetorical questions will more than likely lose you marks in your paper.

Don’t shoot the messenger.

Some (possible) Exceptions

Personally, I would say don’t use rhetorical questions in academic writing – ever.

But, I’ll offer a few suggestions of when you might just get away with it if you really want to use a rhetorical question:

- As an essay title. I would suggest that most people who like rhetorical questions embrace them because they are there to ‘draw in the reader’ or get them on your side. I get that. I really do. So, I’d recommend that if you really want to include a rhetorical question to draw in the reader, use it as the essay title. Keep the actual essay itself to the genre style that your marker will expect: straight up the line, professional and informative text.

“97 percent of scientists argue climate change is real. Such compelling weight of scientific consensus places the 3 percent of scientists who dissent outside of the scientific mainstream.”

The takeaway point here is, if I haven’t convinced you not to use rhetorical questions in essays, I’d suggest that you please check with your teacher on their expectations before submission.

Don’t shoot the messenger. Have I said that enough times in this post?

I didn’t set the rules, but I sure as hell know what they are. And one big, shiny rule that is repeated over and again in faculty lounges is this: Don’t Use Rhetorical Questions in Essays . They are risky, appear out of place, and are despised by a good proportion of current university teachers.

To sum up, here are my top 5 reasons why you shouldn’t use rhetorical questions in your essays:

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a rhetorical analysis | Key concepts & examples

How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis | Key Concepts & Examples

Published on August 28, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A rhetorical analysis is a type of essay that looks at a text in terms of rhetoric. This means it is less concerned with what the author is saying than with how they say it: their goals, techniques, and appeals to the audience.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Key concepts in rhetoric, analyzing the text, introducing your rhetorical analysis, the body: doing the analysis, concluding a rhetorical analysis, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about rhetorical analysis.

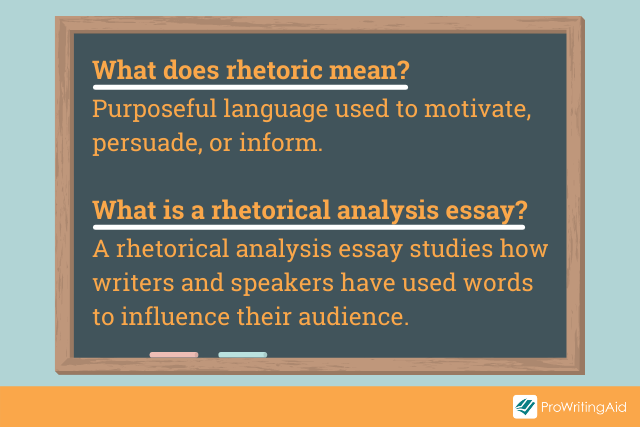

Rhetoric, the art of effective speaking and writing, is a subject that trains you to look at texts, arguments and speeches in terms of how they are designed to persuade the audience. This section introduces a few of the key concepts of this field.

Appeals: Logos, ethos, pathos

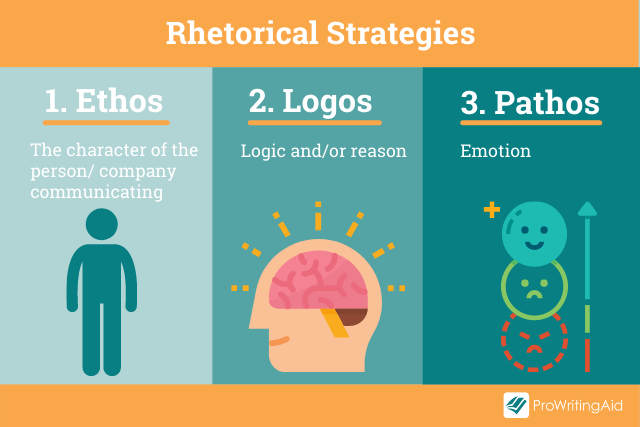

Appeals are how the author convinces their audience. Three central appeals are discussed in rhetoric, established by the philosopher Aristotle and sometimes called the rhetorical triangle: logos, ethos, and pathos.

Logos , or the logical appeal, refers to the use of reasoned argument to persuade. This is the dominant approach in academic writing , where arguments are built up using reasoning and evidence.

Ethos , or the ethical appeal, involves the author presenting themselves as an authority on their subject. For example, someone making a moral argument might highlight their own morally admirable behavior; someone speaking about a technical subject might present themselves as an expert by mentioning their qualifications.

Pathos , or the pathetic appeal, evokes the audience’s emotions. This might involve speaking in a passionate way, employing vivid imagery, or trying to provoke anger, sympathy, or any other emotional response in the audience.

These three appeals are all treated as integral parts of rhetoric, and a given author may combine all three of them to convince their audience.

Text and context

In rhetoric, a text is not necessarily a piece of writing (though it may be this). A text is whatever piece of communication you are analyzing. This could be, for example, a speech, an advertisement, or a satirical image.

In these cases, your analysis would focus on more than just language—you might look at visual or sonic elements of the text too.

The context is everything surrounding the text: Who is the author (or speaker, designer, etc.)? Who is their (intended or actual) audience? When and where was the text produced, and for what purpose?

Looking at the context can help to inform your rhetorical analysis. For example, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech has universal power, but the context of the civil rights movement is an important part of understanding why.

Claims, supports, and warrants

A piece of rhetoric is always making some sort of argument, whether it’s a very clearly defined and logical one (e.g. in a philosophy essay) or one that the reader has to infer (e.g. in a satirical article). These arguments are built up with claims, supports, and warrants.

A claim is the fact or idea the author wants to convince the reader of. An argument might center on a single claim, or be built up out of many. Claims are usually explicitly stated, but they may also just be implied in some kinds of text.

The author uses supports to back up each claim they make. These might range from hard evidence to emotional appeals—anything that is used to convince the reader to accept a claim.

The warrant is the logic or assumption that connects a support with a claim. Outside of quite formal argumentation, the warrant is often unstated—the author assumes their audience will understand the connection without it. But that doesn’t mean you can’t still explore the implicit warrant in these cases.

For example, look at the following statement:

We can see a claim and a support here, but the warrant is implicit. Here, the warrant is the assumption that more likeable candidates would have inspired greater turnout. We might be more or less convinced by the argument depending on whether we think this is a fair assumption.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Rhetorical analysis isn’t a matter of choosing concepts in advance and applying them to a text. Instead, it starts with looking at the text in detail and asking the appropriate questions about how it works:

- What is the author’s purpose?

- Do they focus closely on their key claims, or do they discuss various topics?

- What tone do they take—angry or sympathetic? Personal or authoritative? Formal or informal?

- Who seems to be the intended audience? Is this audience likely to be successfully reached and convinced?

- What kinds of evidence are presented?

By asking these questions, you’ll discover the various rhetorical devices the text uses. Don’t feel that you have to cram in every rhetorical term you know—focus on those that are most important to the text.

The following sections show how to write the different parts of a rhetorical analysis.

Like all essays, a rhetorical analysis begins with an introduction . The introduction tells readers what text you’ll be discussing, provides relevant background information, and presents your thesis statement .

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how an introduction works.

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech is widely regarded as one of the most important pieces of oratory in American history. Delivered in 1963 to thousands of civil rights activists outside the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., the speech has come to symbolize the spirit of the civil rights movement and even to function as a major part of the American national myth. This rhetorical analysis argues that King’s assumption of the prophetic voice, amplified by the historic size of his audience, creates a powerful sense of ethos that has retained its inspirational power over the years.

The body of your rhetorical analysis is where you’ll tackle the text directly. It’s often divided into three paragraphs, although it may be more in a longer essay.

Each paragraph should focus on a different element of the text, and they should all contribute to your overall argument for your thesis statement.

Hover over the example to explore how a typical body paragraph is constructed.

King’s speech is infused with prophetic language throughout. Even before the famous “dream” part of the speech, King’s language consistently strikes a prophetic tone. He refers to the Lincoln Memorial as a “hallowed spot” and speaks of rising “from the dark and desolate valley of segregation” to “make justice a reality for all of God’s children.” The assumption of this prophetic voice constitutes the text’s strongest ethical appeal; after linking himself with political figures like Lincoln and the Founding Fathers, King’s ethos adopts a distinctly religious tone, recalling Biblical prophets and preachers of change from across history. This adds significant force to his words; standing before an audience of hundreds of thousands, he states not just what the future should be, but what it will be: “The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.” This warning is almost apocalyptic in tone, though it concludes with the positive image of the “bright day of justice.” The power of King’s rhetoric thus stems not only from the pathos of his vision of a brighter future, but from the ethos of the prophetic voice he adopts in expressing this vision.

The conclusion of a rhetorical analysis wraps up the essay by restating the main argument and showing how it has been developed by your analysis. It may also try to link the text, and your analysis of it, with broader concerns.

Explore the example below to get a sense of the conclusion.

It is clear from this analysis that the effectiveness of King’s rhetoric stems less from the pathetic appeal of his utopian “dream” than it does from the ethos he carefully constructs to give force to his statements. By framing contemporary upheavals as part of a prophecy whose fulfillment will result in the better future he imagines, King ensures not only the effectiveness of his words in the moment but their continuing resonance today. Even if we have not yet achieved King’s dream, we cannot deny the role his words played in setting us on the path toward it.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

The goal of a rhetorical analysis is to explain the effect a piece of writing or oratory has on its audience, how successful it is, and the devices and appeals it uses to achieve its goals.

Unlike a standard argumentative essay , it’s less about taking a position on the arguments presented, and more about exploring how they are constructed.

The term “text” in a rhetorical analysis essay refers to whatever object you’re analyzing. It’s frequently a piece of writing or a speech, but it doesn’t have to be. For example, you could also treat an advertisement or political cartoon as a text.

Logos appeals to the audience’s reason, building up logical arguments . Ethos appeals to the speaker’s status or authority, making the audience more likely to trust them. Pathos appeals to the emotions, trying to make the audience feel angry or sympathetic, for example.

Collectively, these three appeals are sometimes called the rhetorical triangle . They are central to rhetorical analysis , though a piece of rhetoric might not necessarily use all of them.

In rhetorical analysis , a claim is something the author wants the audience to believe. A support is the evidence or appeal they use to convince the reader to believe the claim. A warrant is the (often implicit) assumption that links the support with the claim.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis | Key Concepts & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 1, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/rhetorical-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an argumentative essay | examples & tips, how to write a literary analysis essay | a step-by-step guide, comparing and contrasting in an essay | tips & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- How It Works

- Prices & Discounts

How to Use Rhetorical Questions in Essay Writing Effectively

Table of contents

If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh?

If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?

These lines are from William Shakespeare’s play, The Merchant of Venice, wherein he uses consecutive rhetorical questions to evoke a sense of human empathy. This literary technique certainly worked here because the speech manages to move us and pushes us to think.

Writers have been incorporating rhetorical questions together for centuries. So, why not take inspiration and include it in your college essays, too?

A rhetorical question is asked more to create an impact or make a statement rather than get an answer. When used effectively, it is a powerful literary device that can add immense value to your writing.

How do you use rhetorical questions in an essay?

Thinking of using rhetorical questions? Start thinking about what you want your reader to take away from it. Craft it as a statement and then convert it into a rhetorical question. Make sure you use rhetorical questions in context to the more significant point you are trying to make.

When Should You Write Rhetorical Questions in Your Essay?

Are you wondering when you can use rhetorical questions? Here are four ways to tactfully use them to elevate your writing and make your essays more thought-provoking.

#1. Hook Readers

We all know how important it is to start your essay with an interesting essay hook that grabs the reader’s attention and keeps them interested. Do you know what would make great essay hooks? Rhetorical questions.

When you begin with a rhetorical question, you make the reader reflect and indicate where you are headed with the essay. Instead of starting your essay with a dull, bland statement, posing a question to make a point is a lot more striking.

How you can use rhetorical questions as essay hooks

Example: What is the world without art?

Starting your essay on art with this question is a clear indication of the angle you are taking. This question does not seek an answer because it aims to make readers feel that the world would be dreary without art.

#2. Evoke Emotions

Your writing is considered genuinely effective when you trigger an emotional response and strike a chord with the reader.

Whether it’s evoking feelings of joy, sadness, rage, hope, or disgust, rhetorical questions can stir the emotional appeal you are going for. They do the work of subtly influencing readers to feel what you are feeling.

So, if you want readers to nod with the agreement, using rhetorical questions to garner that response is a good idea, which is why they are commonly used in persuasive essays.

Example: Doesn’t everyone have the right to be free?

What comes to your mind when you are met with this question? The obvious answer is – yes! This is a fine way to instill compassion and consideration among people.

#3. Emphasize a Point

Making a statement and following it up with a rhetorical question is a smart way to emphasize it and drive the message home. It can be a disturbing statistic, a well-known fact, or even an argument you are presenting, but when you choose to end it with a question, it tends to draw more emphasis and makes the reader sit up and listen.

Sometimes, rather than saying it as a statement, inserting a question leaves a more significant impact.

Example: Between 700 and 800 racehorses are injured and die yearly, with a national average of about two breakdowns for every 1,000 starts. How many will more horses be killed in the name of entertainment?

The question inserted after presenting such a startling statistic is more to express frustration and make the reader realize the gravity of the situation.

#4. Make a Smooth Transition

One of the critical elements while writing an essay is the ability to make smooth transitions from one point or section to another and, of course, use the right transition words in your essay . The essay needs to flow logically while staying within the topic. This is a tricky skill, and few get it right.

Using rhetorical questions is one way to connect paragraphs and maintain cohesiveness in writing. You can pose questions when you want to introduce a new point or conclude a point and emphasize it.

Example: Did you know that Ischaemic heart disease and stroke are the world’s biggest killers? Yes, they accounted for a combined 15.2 million deaths in 2016.

Writing an essay on the leading causes of death? This is an intelligent way to introduce the reason and then go on to explain it.

What are the types of rhetorical questions?

There are three different kinds of rhetorical questions you can use in your essays:

Epiplexis : This rhetorical question is meant to express disapproval or shame to the reader. It is not meant to obtain an answer; it is a way to convince the reader by demonstrating frustration or grief.

Erotesis : This is used to express strong affirmation or denial. It usually implies an answer without giving the expectations of getting one. Erotesis or erotica is used to push the reader to ponder and reflect.

Hypophora : When a question is raised and is immediately answered, it is referred to as hypophora. It is used in a conversational style of writing and aids in generating curiosity in the reader. It’s also a way to make smooth transitions in the essay while letting the writer completely control the narrative.

What to AVOID while writing rhetorical questions in your essay?

It is important to use them sparingly and wherever appropriate. Rhetorical questions cannot be used in every piece of writing.

Using rhetorical questions in the thesis statement : Asking a rhetorical question in your thesis statement is an absolute no-no because thesis statements are meant to answer a question, not pose another question.

Overusing rhetorical questions : Sub7jecting the reader to an overdose of rhetorical questions, consequently or not, makes for an annoying reading experience.

Using rhetorical questions in research papers : Research papers require you to research a topic, take a stand and justify your claims. It’s a formal piece of writing that must be based on facts and research.

So, keep this literary device for persuasive or argumentative essays and creative writing pieces instead of using them in research papers.

20 Ideas of Good Rhetorical Questions to Start an Essay

- "What if the world could be free of poverty?"

- "Is it really possible to have peace in a world so full of conflict?"

- "Can we ever truly understand the depths of the universe?"

- "What does it really mean to be happy?"

- "Is technology bringing us closer together, or driving us apart?"

- "How far would you go to stand up for what you believe in?"

- "What if we could turn back time and prevent disasters?"

- "Can a single person really make a difference in the world?"

- "Is absolute freedom a blessing or a curse?"

- "What defines true success in life?"

- "Are we truly the masters of our own destiny?"

- "Is there a limit to human creativity?"

- "How does one moment change the course of history?"

- "What if we could read each other's thoughts?"

- "Can justice always be served in an imperfect world?"

- "Is it possible to live without regret?"

- "How does culture shape our understanding of the world?"

- "Are we responsible for the happiness of others?"

- "What if the cure for cancer is just around the corner?"

- "How does language shape our reality?"

While rhetorical questions are effective literary devices, you should know when using a rhetorical question is worthwhile and if it adds value to the piece of writing.

If you are struggling with rhetorical questions and are wondering how to get them right, don’t worry. Our professional essay writing service can help you write an essay using the correct literary devices, such as rhetorical questions, that will only alleviate your writing.

Share this article

Achieve Academic Success with Expert Assistance!

Crafted from Scratch for You.

Ensuring Your Work’s Originality.

Transform Your Draft into Excellence.

Perfecting Your Paper’s Grammar, Style, and Format (APA, MLA, etc.).

Calculate the cost of your paper

Get ideas for your essay

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

What Is a Rhetorical Analysis and How to Write a Great One

Helly Douglas

Do you have to write a rhetorical analysis essay? Fear not! We’re here to explain exactly what rhetorical analysis means, how you should structure your essay, and give you some essential “dos and don’ts.”

What is a Rhetorical Analysis Essay?

How do you write a rhetorical analysis, what are the three rhetorical strategies, what are the five rhetorical situations, how to plan a rhetorical analysis essay, creating a rhetorical analysis essay, examples of great rhetorical analysis essays, final thoughts.

A rhetorical analysis essay studies how writers and speakers have used words to influence their audience. Think less about the words the author has used and more about the techniques they employ, their goals, and the effect this has on the audience.

In your analysis essay, you break a piece of text (including cartoons, adverts, and speeches) into sections and explain how each part works to persuade, inform, or entertain. You’ll explore the effectiveness of the techniques used, how the argument has been constructed, and give examples from the text.

A strong rhetorical analysis evaluates a text rather than just describes the techniques used. You don’t include whether you personally agree or disagree with the argument.

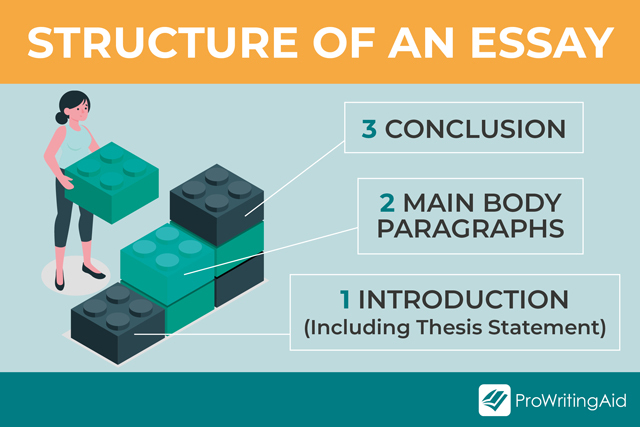

Structure a rhetorical analysis in the same way as most other types of academic essays . You’ll have an introduction to present your thesis, a main body where you analyze the text, which then leads to a conclusion.

Think about how the writer (also known as a rhetor) considers the situation that frames their communication:

- Topic: the overall purpose of the rhetoric

- Audience: this includes primary, secondary, and tertiary audiences

- Purpose: there are often more than one to consider

- Context and culture: the wider situation within which the rhetoric is placed

Back in the 4th century BC, Aristotle was talking about how language can be used as a means of persuasion. He described three principal forms —Ethos, Logos, and Pathos—often referred to as the Rhetorical Triangle . These persuasive techniques are still used today.

Rhetorical Strategy 1: Ethos

Are you more likely to buy a car from an established company that’s been an important part of your community for 50 years, or someone new who just started their business?

Reputation matters. Ethos explores how the character, disposition, and fundamental values of the author create appeal, along with their expertise and knowledge in the subject area.

Aristotle breaks ethos down into three further categories:

- Phronesis: skills and practical wisdom

- Arete: virtue

- Eunoia: goodwill towards the audience

Ethos-driven speeches and text rely on the reputation of the author. In your analysis, you can look at how the writer establishes ethos through both direct and indirect means.

Rhetorical Strategy 2: Pathos

Pathos-driven rhetoric hooks into our emotions. You’ll often see it used in advertisements, particularly by charities wanting you to donate money towards an appeal.

Common use of pathos includes:

- Vivid description so the reader can imagine themselves in the situation

- Personal stories to create feelings of empathy

- Emotional vocabulary that evokes a response

By using pathos to make the audience feel a particular emotion, the author can persuade them that the argument they’re making is compelling.

Rhetorical Strategy 3: Logos

Logos uses logic or reason. It’s commonly used in academic writing when arguments are created using evidence and reasoning rather than an emotional response. It’s constructed in a step-by-step approach that builds methodically to create a powerful effect upon the reader.

Rhetoric can use any one of these three techniques, but effective arguments often appeal to all three elements.

The rhetorical situation explains the circumstances behind and around a piece of rhetoric. It helps you think about why a text exists, its purpose, and how it’s carried out.

The rhetorical situations are:

- 1) Purpose: Why is this being written? (It could be trying to inform, persuade, instruct, or entertain.)

- 2) Audience: Which groups or individuals will read and take action (or have done so in the past)?

- 3) Genre: What type of writing is this?

- 4) Stance: What is the tone of the text? What position are they taking?

- 5) Media/Visuals: What means of communication are used?

Understanding and analyzing the rhetorical situation is essential for building a strong essay. Also think about any rhetoric restraints on the text, such as beliefs, attitudes, and traditions that could affect the author's decisions.

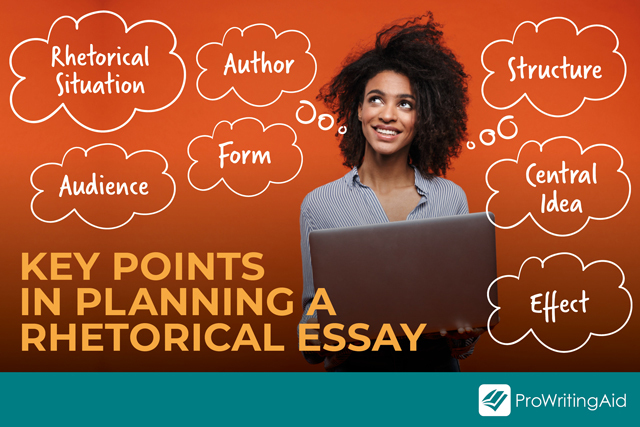

Before leaping into your essay, it’s worth taking time to explore the text at a deeper level and considering the rhetorical situations we looked at before. Throw away your assumptions and use these simple questions to help you unpick how and why the text is having an effect on the audience.

1: What is the Rhetorical Situation?

- Why is there a need or opportunity for persuasion?

- How do words and references help you identify the time and location?

- What are the rhetoric restraints?

- What historical occasions would lead to this text being created?

2: Who is the Author?

- How do they position themselves as an expert worth listening to?

- What is their ethos?

- Do they have a reputation that gives them authority?

- What is their intention?

- What values or customs do they have?

3: Who is it Written For?

- Who is the intended audience?

- How is this appealing to this particular audience?

- Who are the possible secondary and tertiary audiences?

4: What is the Central Idea?

- Can you summarize the key point of this rhetoric?

- What arguments are used?

- How has it developed a line of reasoning?

5: How is it Structured?

- What structure is used?

- How is the content arranged within the structure?

6: What Form is Used?

- Does this follow a specific literary genre?

- What type of style and tone is used, and why is this?

- Does the form used complement the content?

- What effect could this form have on the audience?

7: Is the Rhetoric Effective?

- Does the content fulfil the author’s intentions?

- Does the message effectively fit the audience, location, and time period?

Once you’ve fully explored the text, you’ll have a better understanding of the impact it’s having on the audience and feel more confident about writing your essay outline.

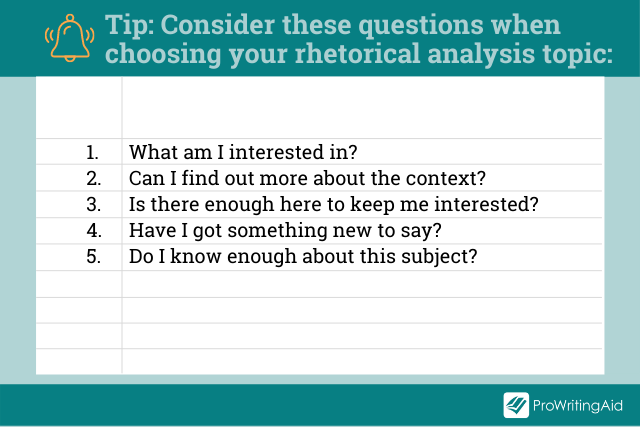

A great essay starts with an interesting topic. Choose carefully so you’re personally invested in the subject and familiar with it rather than just following trending topics. There are lots of great ideas on this blog post by My Perfect Words if you need some inspiration. Take some time to do background research to ensure your topic offers good analysis opportunities.

Remember to check the information given to you by your professor so you follow their preferred style guidelines. This outline example gives you a general idea of a format to follow, but there will likely be specific requests about layout and content in your course handbook. It’s always worth asking your institution if you’re unsure.

Make notes for each section of your essay before you write. This makes it easy for you to write a well-structured text that flows naturally to a conclusion. You will develop each note into a paragraph. Look at this example by College Essay for useful ideas about the structure.

1: Introduction

This is a short, informative section that shows you understand the purpose of the text. It tempts the reader to find out more by mentioning what will come in the main body of your essay.

- Name the author of the text and the title of their work followed by the date in parentheses

- Use a verb to describe what the author does, e.g. “implies,” “asserts,” or “claims”

- Briefly summarize the text in your own words

- Mention the persuasive techniques used by the rhetor and its effect

Create a thesis statement to come at the end of your introduction.

After your introduction, move on to your critical analysis. This is the principal part of your essay.

- Explain the methods used by the author to inform, entertain, and/or persuade the audience using Aristotle's rhetorical triangle

- Use quotations to prove the statements you make

- Explain why the writer used this approach and how successful it is

- Consider how it makes the audience feel and react

Make each strategy a new paragraph rather than cramming them together, and always use proper citations. Check back to your course handbook if you’re unsure which citation style is preferred.

3: Conclusion

Your conclusion should summarize the points you’ve made in the main body of your essay. While you will draw the points together, this is not the place to introduce new information you’ve not previously mentioned.

Use your last sentence to share a powerful concluding statement that talks about the impact the text has on the audience(s) and wider society. How have its strategies helped to shape history?

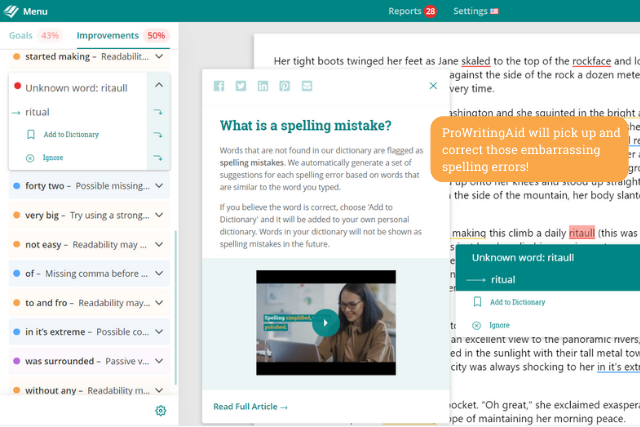

Before You Submit

Poor spelling and grammatical errors ruin a great essay. Use ProWritingAid to check through your finished essay before you submit. It will pick up all the minor errors you’ve missed and help you give your essay a final polish. Look at this useful ProWritingAid webinar for further ideas to help you significantly improve your essays. Sign up for a free trial today and start editing your essays!

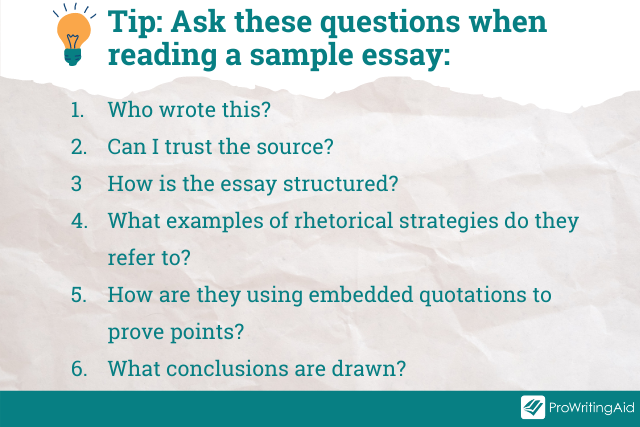

You’ll find countless examples of rhetorical analysis online, but they range widely in quality. Your institution may have example essays they can share with you to show you exactly what they’re looking for.

The following links should give you a good starting point if you’re looking for ideas:

Pearson Canada has a range of good examples. Look at how embedded quotations are used to prove the points being made. The end questions help you unpick how successful each essay is.

Excelsior College has an excellent sample essay complete with useful comments highlighting the techniques used.

Brighton Online has a selection of interesting essays to look at. In this specific example, consider how wider reading has deepened the exploration of the text.

Writing a rhetorical analysis essay can seem daunting, but spending significant time deeply analyzing the text before you write will make it far more achievable and result in a better-quality essay overall.

It can take some time to write a good essay. Aim to complete it well before the deadline so you don’t feel rushed. Use ProWritingAid’s comprehensive checks to find any errors and make changes to improve readability. Then you’ll be ready to submit your finished essay, knowing it’s as good as you can possibly make it.

Try ProWritingAid's Editor for Yourself

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Helly Douglas is a UK writer and teacher, specialising in education, children, and parenting. She loves making the complex seem simple through blogs, articles, and curriculum content. You can check out her work at hellydouglas.com or connect on Twitter @hellydouglas. When she’s not writing, you will find her in a classroom, being a mum or battling against the wilderness of her garden—the garden is winning!

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

9.5 Writing Process: Thinking Critically about Rhetoric

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Develop a rhetorical analysis through multiple drafts.

- Identify and analyze rhetorical strategies in a rhetorical analysis.

- Demonstrate flexible strategies for generating ideas, drafting, reviewing, collaborating, revising, rewriting, and editing.

- Give and act on productive feedback for works in progress.

The ability to think critically about rhetoric is a skill you will use in many of your classes, in your work, and in your life to gain insight from the way a text is written and organized. You will often be asked to explain or to express an opinion about what someone else has communicated and how that person has done so, especially if you take an active interest in politics and government. Like Eliana Evans in the previous section, you will develop similar analyses of written works to help others understand how a writer or speaker may be trying to reach them.

Summary of Assignment: Rhetorical Analysis

The assignment is to write a rhetorical analysis of a piece of persuasive writing. It can be an editorial, a movie or book review, an essay, a chapter in a book, or a letter to the editor. For your rhetorical analysis, you will need to consider the rhetorical situation—subject, author, purpose, context, audience, and culture—and the strategies the author uses in creating the argument. Back up all your claims with evidence from the text. In preparing your analysis, consider these questions:

- What is the subject? Be sure to distinguish what the piece is about.

- Who is the writer, and what do you know about them? Be sure you know whether the writer is considered objective or has a particular agenda.

- Who are the readers? What do you know or what can you find out about them as the particular audience to be addressed at this moment?

- What is the purpose or aim of this work? What does the author hope to achieve?

- What are the time/space/place considerations and influences of the writer? What can you know about the writer and the full context in which they are writing?

- What specific techniques has the writer used to make their points? Are these techniques successful, unsuccessful, or questionable?

For this assignment, read the following opinion piece by Octavio Peterson, printed in his local newspaper. You may choose it as the text you will analyze, continuing the analysis on your own, or you may refer to it as a sample as you work on another text of your choosing. Your instructor may suggest presidential or other political speeches, which make good subjects for rhetorical analysis.

When you have read the piece by Peterson advocating for the need to continue teaching foreign languages in schools, reflect carefully on the impact the letter has had on you. You are not expected to agree or disagree with it. Instead, focus on the rhetoric—the way Peterson uses language to make his point and convince you of the validity of his argument.

Another Lens. Consider presenting your rhetorical analysis in a multimodal format. Use a blogging site or platform such as WordPress or Tumblr to explore the blogging genre, which includes video clips, images, hyperlinks, and other media to further your discussion. Because this genre is less formal than written text, your tone can be conversational. However, you still will be required to provide the same kind of analysis that you would in a traditional essay. The same materials will be at your disposal for making appeals to persuade your readers. Rhetorical analysis in a blog may be a new forum for the exchange of ideas that retains the basics of more formal communication. When you have completed your work, share it with a small group or the rest of the class. See Multimodal and Online Writing: Creative Interaction between Text and Image for more about creating a multimodal composition.

Quick Launch: Start with a Thesis Statement

After you have read this opinion piece, or another of your choice, several times and have a clear understanding of it as a piece of rhetoric, consider whether the writer has succeeded in being persuasive. You might find that in some ways they have and in others they have not. Then, with a clear understanding of your purpose—to analyze how the writer seeks to persuade—you can start framing a thesis statement : a declarative sentence that states the topic, the angle you are taking, and the aspects of the topic the rest of the paper will support.

Complete the following sentence frames as you prepare to start:

- The subject of my rhetorical analysis is ________.

- My goal is to ________, not necessarily to ________.

- The writer’s main point is ________.

- I believe the writer has succeeded (or not) because ________.

- I believe the writer has succeeded in ________ (name the part or parts) but not in ________ (name the part or parts).

- The writer’s strongest (or weakest) point is ________, which they present by ________.

Drafting: Text Evidence and Analysis of Effect

As you begin to draft your rhetorical analysis, remember that you are giving your opinion on the author’s use of language. For example, Peterson has made a decision about the teaching of foreign languages, something readers of the newspaper might have different views on. In other words, there is room for debate and persuasion.

The context of the situation in which Peterson finds himself may well be more complex than he discusses. In the same way, the context of the piece you choose to analyze may also be more complex. For example, perhaps Greendale is facing an economic crisis and must pare its budget for educational spending and public works. It’s also possible that elected officials have made budget cuts for education a part of their platform or that school buildings have been found obsolete for safety measures. On the other hand, maybe a foreign company will come to town only if more Spanish speakers can be found locally. These factors would play a part in a real situation, and rhetoric would reflect that. If applicable, consider such possibilities regarding the subject of your analysis. Here, however, these factors are unknown and thus do not enter into the analysis.

Introduction

One effective way to begin a rhetorical analysis is by using an anecdote, as Eliana Evans has done. For a rhetorical analysis of the opinion piece, a writer might consider an anecdote about a person who was in a situation in which knowing another language was important or not important. If they begin with an anecdote, the next part of the introduction should contain the following information:

- Author’s name and position, or other qualification to establish ethos

- Title of work and genre

- Author’s thesis statement or stance taken (“Peterson argues that . . .”)

- Brief introductory explanation of how the author develops and supports the thesis or stance

- If relevant, a brief summary of context and culture

Once the context and situation for the analysis are clear, move directly to your thesis statement. In this case, your thesis statement will be your opinion of how successful the author has been in achieving the established goal through the use of rhetorical strategies. Read the sentences in Table 9.1 , and decide which would make the best thesis statement. Explain your reasoning in the right-hand column of this or a similar chart.

The introductory paragraph or paragraphs should serve to move the reader into the body of the analysis and signal what will follow.

Your next step is to start supporting your thesis statement—that is, how Octavio Peterson, or the writer of your choice, does or does not succeed in persuading readers. To accomplish this purpose, you need to look closely at the rhetorical strategies the writer uses.

First, list the rhetorical strategies you notice while reading the text, and note where they appear. Keep in mind that you do not need to include every strategy the text contains, only those essential ones that emphasize or support the central argument and those that may seem fallacious. You may add other strategies as well. The first example in Table 9.2 has been filled in.

When you have completed your list, consider how to structure your analysis. You will have to decide which of the writer’s statements are most effective. The strongest point would be a good place to begin; conversely, you could begin with the writer’s weakest point if that suits your purposes better. The most obvious organizational structure is one of the following:

- Go through the composition paragraph by paragraph and analyze its rhetorical content, focusing on the strategies that support the writer’s thesis statement.

- Address key rhetorical strategies individually, and show how the author has used them.

As you read the next few paragraphs, consult Table 9.3 for a visual plan of your rhetorical analysis. Your first body paragraph is the first of the analytical paragraphs. Here, too, you have options for organizing. You might begin by stating the writer’s strongest point. For example, you could emphasize that Peterson appeals to ethos by speaking personally to readers as fellow citizens and providing his credentials to establish credibility as someone trustworthy with their interests at heart.

Following this point, your next one can focus, for instance, on Peterson’s view that cutting foreign language instruction is a danger to the education of Greendale’s children. The points that follow support this argument, and you can track his rhetoric as he does so.

You may then use the second or third body paragraph, connected by a transition, to discuss Peterson’s appeal to logos. One possible transition might read, “To back up his assertion that omitting foreign languages is detrimental to education, Peterson provides examples and statistics.” Locate examples and quotes from the text as needed. You can discuss how, in citing these statistics, Peterson uses logos as a key rhetorical strategy.

In another paragraph, focus on other rhetorical elements, such as parallelism, repetition, and rhetorical questions. Moreover, be sure to indicate whether the writer acknowledges counterclaims and whether they are accepted or ultimately rejected.

The question of other factors at work in Greendale regarding finances, or similar factors in another setting, may be useful to mention here if they exist. As you continue, however, keep returning to your list of rhetorical strategies and explaining them. Even if some appear less important, they should be noted to show that you recognize how the writer is using language. You will likely have a minimum of four body paragraphs, but you may well have six or seven or even more, depending on the work you are analyzing.

In your final body paragraph, you might discuss the argument that Peterson, for example, has made by appealing to readers’ emotions. His calls for solidarity at the end of the letter provide a possible solution to his concern that the foreign language curriculum “might vanish like a puff of smoke.”

Use Table 9.3 to organize your rhetorical analysis. Be sure that each paragraph has a topic sentence and that you use transitions to flow smoothly from one idea to the next.

As you conclude your essay, your own logic in discussing the writer’s argument will make it clear whether you have found their claims convincing. Your opinion, as framed in your conclusion, may restate your thesis statement in different words, or you may choose to reveal your thesis at this point. The real function of the conclusion is to confirm your evaluation and show that you understand the use of the language and the effectiveness of the argument.

In your analysis, note that objections could be raised because Peterson, for example, speaks only for himself. You may speculate about whether the next edition of the newspaper will feature an opposing opinion piece from someone who disagrees. However, it is not necessary to provide answers to questions you raise here. Your conclusion should summarize briefly how the writer has made, or failed to make, a forceful argument that may require further debate.

For more guidance on writing a rhetorical analysis, visit the Illinois Writers Workshop website or watch this tutorial .

Peer Review: Guidelines toward Revision and the “Golden Rule”

Now that you have a working draft, your next step is to engage in peer review, an important part of the writing process. Often, others can identify things you have missed or can ask you to clarify statements that may be clear to you but not to others. For your peer review, follow these steps and make use of Table 9.4 .

- Quickly skim through your peer’s rhetorical analysis draft once, and then ask yourself, What is the main point or argument of my peer’s work?

- Highlight, underline, or otherwise make note of statements or instances in the paper where you think your peer has made their main point.

- Look at the draft again, this time reading it closely.

- Ask yourself the following questions, and comment on the peer review sheet as shown.

The Golden Rule

An important part of the peer review process is to keep in mind the familiar wisdom of the “Golden Rule”: treat others as you would have them treat you. This foundational approach to human relations extends to commenting on others’ work. Like your peers, you are in the same situation of needing opinion and guidance. Whatever you have written will seem satisfactory or better to you because you have written it and know what you mean to say.

However, your peers have the advantage of distance from the work you have written and can see it through their own eyes. Likewise, if you approach your peer’s work fairly and free of personal bias, you’re likely to be more constructive in finding parts of their writing that need revision. Most important, though, is to make suggestions tactfully and considerately, in the spirit of helping, not degrading someone’s work. You and your peers may be reluctant to share your work, but if everyone approaches the review process with these ideas in mind, everyone will benefit from the opportunity to provide and act on sincerely offered suggestions.

Revising: Staying Open to Feedback and Working with It

Once the peer review process is complete, your next step is to revise the first draft by incorporating suggestions and making changes on your own. Consider some of these potential issues when incorporating peers’ revisions and rethinking your own work.

- Too much summarizing rather than analyzing

- Too much informal language or an unintentional mix of casual and formal language

- Too few, too many, or inappropriate transitions

- Illogical or unclear sequence of information

- Insufficient evidence to support main ideas effectively

- Too many generalities rather than specific facts, maybe from trying to do too much in too little time

In any case, revising a draft is a necessary step to produce a final work. Rarely will even a professional writer arrive at the best point in a single draft. In other words, it’s seldom a problem if your first draft needs refocusing. However, it may become a problem if you don’t address it. The best way to shape a wandering piece of writing is to return to it, reread it, slow it down, take it apart, and build it back up again. Approach first-draft writing for what it is: a warm-up or rehearsal for a final performance.

Suggestions for Revising

When revising, be sure your thesis statement is clear and fulfills your purpose. Verify that you have abundant supporting evidence and that details are consistently on topic and relevant to your position. Just before arriving at the conclusion, be sure you have prepared a logical ending. The concluding statement should be strong and should not present any new points. Rather, it should grow out of what has already been said and return, in some degree, to the thesis statement. In the example of Octavio Peterson, his purpose was to persuade readers that teaching foreign languages in schools in Greendale should continue; therefore, the conclusion can confirm that Peterson achieved, did not achieve, or partially achieved his aim.

When revising, make sure the larger elements of the piece are as you want them to be before you revise individual sentences and make smaller changes. If you make small changes first, they might not fit well with the big picture later on.

One approach to big-picture revising is to check the organization as you move from paragraph to paragraph. You can list each paragraph and check that its content relates to the purpose and thesis statement. Each paragraph should have one main point and be self-contained in showing how the rhetorical devices used in the text strengthen (or fail to strengthen) the argument and the writer’s ability to persuade. Be sure your paragraphs flow logically from one to the other without distracting gaps or inconsistencies.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/9-5-writing-process-thinking-critically-about-rhetoric

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Pennington Publishing Blog

- Grammar/Mechanics

- Literacy Centers

- Spelling/Vocabulary

- Study Skills

- Uncategorized

Rhetorical Questions in Essays

Rhetorical Questions “Mr. Smith says that I shouldn’t use thought-provoking questions in my thesis statements,” said Issa. “May I read you my thesis?” “Sure. Let’s hear it,” responds Mandy. “My thesis is ‘Do people really want to be successful and happy?’” “Well, it is called a thesis statement , not a thesis question , ” Mandy replied. “Plus, doesn’t the answer appear in the question itself?” “Oh, I get it. It’s one of those rhetorical questions,” says Issa. “But, do you really get it?” asks Mandy. “Ah… A rhetorical question. Very funny.” “Apparently not so funny to Mr. Smith,” says Mandy.

Definition and Examples

A rhetorical question is a statement formed as a question. Rhetorical questions can be manipulative because they are designed to appear objective and open-ended, but may actually lead the reader to a foregone conclusion.

The rhetorical question takes several forms:

- It may answer itself and require no response. Example: Do people want to be successful?

- It may be used to provoke thought. Example: What if this generation could solve hunger?

- It may be used to state the obvious. Example: Can students try a bit harder next time?

- It may have no possible answer. Example: What if there is no answer to this problem?

Read the rules.

Don’t use rhetorical questions as thesis statements. Conclusion paragraphs may include rhetorical questions to provide questions for further study beyond the essay itself.

In the following sentences, [bracket] the rhetorical questions.

- How could they know? Why are the couples traveling to Europe for business?

- Without the tools the project was impossible to complete. Why bother? Does this project have a purpose?

- What is the message within that painting? What if all works of art meant something?

- If love is the answer, what is the question? Why do people fall in love? Does everyone do so?

- What happens when dreams are delayed? Can dreams be real? Or are dreams simply dreams?

Revise the rhetorical question into a statement.

Of what use are rhetorical questions?

- [How could they know?] Why are the couples traveling to Europe for business?

- Without the tools the project was impossible to complete. [Why bother?] [Does this project have a purpose?]

- What is the message within that painting? [What if all works of art meant something?]

- [If love is the answer, what is the question?] [Why do people fall in love?] [Does everyone do so?]

- [What happens when dreams are delayed?] [Can dreams be real?] [Or are dreams simply dreams?]

For more essay rules and practice, check out the author’s TEACHING ESSAYS BUNDLE . This curriculum includes 42 essay strategy worksheets corresponding to teach the Common Core State Writing Standards, 8 on-demand writing fluencies, 8 writing process essays (4 argumentative and 4 informative/explanatory), 64 sentence revision and 64 rhetorical stance “openers,” writing posters, and helpful editing resources.

Differentiate your essay instruction in this comprehensive writing curriculum with remedial writing worksheets, including sentence structure, grammar, thesis statements, errors in reasoning, and transitions.

Plus, get an e-comment bank of 438 prescriptive writing responses with an link to insert into Microsoft Word® for easy e-grading (works great with Google Docs) ,

Download the following 24 FREE Writing Style Posters to help your students learn the essay rules. Each has a funny or ironic statement (akin to “Let’s eat Grandma) to teach the memorable rule.

Writing composition rules , essay rules , essay structure , essay style , essay writing , essay writing rules , five paragraph essays , how to write an essay , Mark Pennington , questions in conclusions , questions in essays , rhetorical devices , rhetorical questions , Teaching Essay Strategies , thesis statement questions , using questions to provoke thought , writing programs

- No comments yet.

- No trackbacks yet.

Links to Programs and Resources

- About the Author/Contact Us

- Free Reading/ELA Assessments

- Free Articles and Resources

- Testimonials

Join the SOR Literacy Hub - Resource Sharing FB Group

https://www.facebook.com/groups/sorliteracyhub

Recent Articles

- Free Science of Reading Lessons | ELL January 2, 2024

- Free Science of Reading Lessons | SPED January 2, 2024

- Free Science of Reading Lessons | High School January 2, 2024

- Free Science of Reading Lessons | Middle School January 2, 2024

- Free Science of Reading Lessons | Grade 6 January 2, 2024

- Free Science of Reading Lessons | Grade 5 January 2, 2024

- Free Science of Reading Lessons | Grade 4 January 2, 2024

- Reading Intervention Flow Chart December 19, 2023

- Mid-Year Reading Intervention Checklist December 19, 2023

- Reading Rules versus Patterns? December 19, 2023

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

What Is a Rhetorical Question?

3-minute read

- 4th April 2023

Rhetorical questions can be an effective tool for writers and speakers to connect with their audience and convey their message more effectively. In this article, we’ll discuss rhetorical questions, how to use them, and some examples.

Definition of a Rhetorical Question

A rhetorical question is a question that isn’t meant to be answered. It’s asked to make a point or create an effect rather than to elicit an actual response. Here are a few examples:

· Are you kidding me? ‒ Used to express disbelief or shock

· Do you think I was born yesterday? ‒ Used to express suspicion or doubt

· Why not? – Used to express willingness to try something

How to Use a Rhetorical Question

Rhetorical questions are rhetorical devices often used in writing and speech to engage the audience, emphasize a point, or provoke thought. They can be used to introduce a topic, make a statement, or open an argument.

Conversational Rhetorical Questions

Rhetorical questions are used in everyday speech and conversations. For example:

· Who knows? ‒ Indicates that no one knows the answer

· Isn’t that the truth? ‒ Used to express agreement with something

Introducing a Topic

Rhetorical questions are a common strategy in essay writing to introduce a topic or persuade the reader . Here are some essay questions with rhetorical questions you could use to introduce the topic:

Essay Question: Why should we care about climate change?

Rhetorical Question Introduction: Would you like to live on a dying planet?

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Essay Question: Are dress codes a good idea for school?

Rhetorical Question Introduction: Wouldn’t you like the freedom to choose what you want to wear?

Famous Examples of Rhetorical Questions

Rhetorical questions are a powerful and effective device to use in speech and writing, which is why you can find countless examples, from past and present figures, using them. Here are a few examples:

Here, Obama is using rhetorical questions to emphasize a point to his audience about what type of nation America is. The questions demonstrate his stance on immigration in America.

Dr. King used a variety of literary devices in his writing and speeches to inspire and invoke change and action in his audience. Here, he poses the rhetorical question, “Now, what does all of this mean in this great period of history?” to get his audience thinking. There’s no obvious answer here. He’s setting up his response to this seemingly unanswerable question.

Here, Sojourner Truth is speaking at the 1851 Women’s Convention to persuade the audience that women should have the right to vote like men. She’s emphasizing that she can do everything a man can do and more (childbirth), but she can’t vote like a man because she’s a woman.

Rhetorical questions are statements pretending to be a question. They’re not to be answered, as their answer should be obvious or there isn’t an obvious answer.

You can use rhetorical questions to emphasize a point, introduce a topic, or encourage your audience to think critically about an issue. If you’re looking to enhance your speaking or writing, check out our Literary Devices page to learn more.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

4-minute read

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

2-minute read

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

The 5 Best Ecommerce Website Design Tools

A visually appealing and user-friendly website is essential for success in today’s competitive ecommerce landscape....

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Rhetorical Question

Rhetorical Question Definition

What is a rhetorical question? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

A rhetorical question is a figure of speech in which a question is asked for a reason other than to get an answer—most commonly, it's asked to make a persuasive point. For example, if a person asks, "How many times do I have to tell you not to eat my dessert?" he or she does not want to know the exact number of times the request will need to be repeated. Rather, the speaker's goal is to emphasize his or her growing frustration and—ideally—change the dessert-thief's behavior.

Some additional key details about rhetorical questions:

- Rhetorical questions are also sometimes called erotema.

- Rhetorical questions are a type of figurative language —they are questions that have another layer of meaning on top of their literal meaning.

- Because rhetorical questions challenge the listener, raise doubt, and help emphasize ideas, they appear often in songs and speeches, as well as in literature.

How to Pronounce Rhetorical Question

Here's how to pronounce rhetorical question: reh- tor -ih-kuhl kwes -chun

Rhetorical Questions and Punctuation

A question is rhetorical if and only if its goal is to produce an effect on the listener, rather than to obtain information. In other words, a rhetorical question is not what we might call a "true" question in search of an answer. For this reason, many sources argue that rhetorical questions do not need to end in a traditional question mark. In the late 1500's, English printer Henry Denham actually designed a special question mark for rhetorical questions, which he referred to as a "percontation point." It looked like this: ⸮ (Here's a wikipedia article about Denham's percontation point and other forms of "irony punctuation.")

Though the percontation point has fallen out of use, modern writers do sometimes substitute a traditional question mark with a period or exclamation point after a rhetorical question. There is a lively debate as to whether this alternative punctuation is grammatically correct. Here are some guidelines to follow:

- In general, rhetorical questions do require a question mark.

- When a question is a request in disguise, you may use a period. For instance, it is ok to write: "Will you please turn your attention to the speaker." or "Can you please go to the back of the line."

- When a question is an exclamation in disguise, you may use an exclamation point. For instance, it is okay to write: "Were they ever surprised!"

- When asking a question emotionally, you may use an exclamation point. For instance, " Who could blame him!" and "How do you know that!" are both correct.

Rhetorical Questions vs. Hypophora

Rhetorical questions are easy to confuse with hypophora , a similar but fundamentally different figure of speech in which a speaker poses a question and then immediately answers it. Hypophora is frequently used in persuasive speaking because the speaker can pose and answer a question that the audience is likely to be wondering about, thereby making the thought processes of the speaker and the audience seem more aligned. For example, here is an example of hypophora used in a speech by Dwight Eisenhower:

When the enemy struck on that June day of 1950, what did America do? It did what it always has done in all its times of peril. It appealed to the heroism of its youth.

While Eisenhower asked this question without expecting an answer from his audience, this is an example of hypophora because he answered his own question. In a rhetorical question, by contrast, the answer would be implied in the question—to pose a rhetorical question, Eisenhower might have said instead, "When the enemy struck, who in their right mind would have done nothing to retaliate?"

Rhetorical Questions vs. Aporia

Rhetorical questions are also related to a figure of speech called aporia . Aporia is an expression of doubt that may be real, or which may be feigned for rhetorical effect. These expressions of doubt may or may not be made through the form of a question. When they are made through the form of a question, those questions are sometimes rhetorical.

Aporia and Rhetorical Questions

When someone is pretending doubt for rhetorical effect, and uses a question as part of that expression of doubt, then the question is rhetorical. For example, consider this quotation from an oration by the ancient Greek orator Demosthenes:

I am at no loss for information about you and your family; but I am at a loss where to begin. Shall I relate how your father Tromes was a slave in the house of Elpias, who kept an elementary school near the Temple of Theseus, and how he wore shackles on his legs and a timber collar round his neck? Or how your mother practised daylight nuptials in an outhouse next door to Heros the bone-setter, and so brought you up to act in tableaux vivants and to excel in minor parts on the stage?

The questions Demosthenes poses are examples of both aporia and rhetorical question, because Demosthenes is feigning doubt (by posing rhetorical questions) in order to cast insulting aspersions on the character of the person he's addressing.

Aporia Without Rhetorical Questions

If the expression of doubt is earnest, however, then the question is not rhetorical. An example of aporia that is not also a rhetorical question comes from the most famous excerpt of Shakespeare's Hamlet:

To be or not to be—that is the question. Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And by opposing end them?

While Hamlet asks this question without expecting an answer (he's alone when he asks it), he's not asking in order to persuade or make a point. It's a legitimate expression of doubt, which leads Hamlet into a philosophical debate about whether one should face the expected miseries of life or kill oneself and face the possible unknown terrors of death. It's therefore not a rhetorical question, because Hamlet asks the question as an opening to actually seek an answer to the question he is obsessing over.

Rhetorical Question Examples

Rhetorical question examples in literature.

Rhetorical questions are particularly common in plays, appearing frequently in both spoken dialogue between characters, and in monologues or soliloquies, where they allow the playwright to reveal a character's inner life.

Rhetorical Questions in Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice :

In his speech from Act 3, Scene 1 of Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice , Shylock uses rhetorical questions to point out the indisputable similarities between Jews and Christians, in such a way that any listener would find him impossible to contradict:

I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? if you tickle us, do we not laugh? if you poison us, do we not die? and if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you teach me, I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction.

Rhetorical questions in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet :

In this soliloquy from Act 2, Scene 2 of Romeo and Juliet , Juliet poses a series of rhetorical questions as she struggles to grasp the difficult truth—that her beloved Romeo is a member of the Montague family: