If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

AP®︎/College Art History

Course: ap®︎/college art history > unit 2, judaism, an introduction.

- Jewish history to the middle ages

- Jewish history—1750 to WW II

- Jewish history—the post-war period

- Writing a history of Jewish architecture

Judaism and time

The debate continues, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- Travel/Study

BIBLE HISTORY DAILY

The origins of judaism.

When did the laws of the Torah become the norm?

Public ritual bath from the Herodian fortress at Masada, and the origins of Judaism. The massive emergence of similar pools across Judea, in accordance with the purity laws of the Torah, corresponds with the origins of Judaism in the mid-second century BCE. Photo by Talmoryair, CC BY 3.0 .

Where can we situate the origins of Judaism? If we were able to travel back in time, would we find ancient Israelites and Judeans following the laws of the Torah during the First Temple period? Almost certainly not, claims Yonatan Adler in his recent scholarly book and a popular article that was just published in the Winter 2022 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review . So, what about during the Babylonian Exile (sixth century BCE), which is when many biblical scholars date the completion of the Torah? In his article “ The Genesis of Judaism ,” Adler asserts that even at this later date, most ordinary Judeans were not yet following the laws of the Torah. What does this mean for the origins of Judaism?

Become a Member of Biblical Archaeology Society Now and Get More Than Half Off the Regular Price of the All-Access Pass!

Explore the world’s most intriguing biblical scholarship.

Dig into more than 9,000 articles in the Biblical Archaeology Society’s vast library plus much more with an All-Access pass.

The Genesis of Judaism

For millennia, Jewish identity has been closely associated with observance of the laws of the Torah . The biblical books of Deuteronomy and Leviticus give numerous prohibitions and commandments that regulate different aspects of Jewish life—from prayers and religious rituals to agriculture to dietary prescriptions and ritual bathing. It stands to reason that the moment when people in ancient Judea recognized these laws as authoritative would mark the origins of Judaism.

As Adler discusses, however, even the Bible itself presents a somewhat different picture:

Ancient Israelite society is never portrayed as keeping the laws of the Torah. The Israelites during the time of the First Temple are never said to refrain from eating pork or shrimp, from doing this or that on the Sabbath, or from wearing mixtures of linen and wool. … Nor is anybody ever said to wear fringes on their clothing, to don tefillin on their arm and head, or to have an inscribed mezuzah on the doorposts of their homes. Whatever it is that the biblical Israelites are doing, they do not seem to be practicing Judaism!

So, when can we date the actual origins of Judaism? Or, as Yonatan Adler puts it: “When did ancient Judeans, as a society, first begin to observe the laws of the Torah in their daily lives?” To answer this question, Adler looks at the archaeological evidence for widespread observance of the laws of the Torah. He suggests that our inquiry begin in the first century CE, where we have plenty of evidence. He then goes backward in time, until he reaches a point when we can no longer see material traces of typical Jewish religious and ritual practices.

The Judean community on Elephantine, in southern Egypt, produced a wealth of documents in Aramaic, including this adoption contract from October 22, 416 BCE. They provide clues also about observance (or not observance) of the laws of the Torah. Photo courtesy of Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Theodora Wilbour, from the collection of her father, Charles Edwin Wilbour.

In particular, Adler traces archaeological imprints of the biblical laws addressing dietary prohibitions, ritual purity, graven images, tefillin and mezuzot , and Sabbath observance. In every instance, the trail of archaeological evidence ends in the mid-second century BCE—moving the origins of Judaism several centuries later than even the most critical scholars previously thought.

Surprisingly, textual sources from Babylon and Egypt, including this letter from the island of Elephantine, reveal that fifth-century BCE Judeans did not celebrate Passover at a set date, were not aware of a seven-day week or the Sabbath prohibitions, and that they sometimes prayed to deities other than Yahweh.

Widespread observance of the ritual purity laws , as attested through ritual baths (later known as mikva’ot ) and the use chalk vessels, is strong in the first century BCE but gradually disappears as we look further back in time past the late second century BCE.

When it comes to the biblical command against graven images (Deuteronomy 5:8), we can see that during the Persian period even the high priests were issuing coins with depictions of human and animal figures. The pictured silver coin from around 350 BCE bears, on its obverse, a crude depiction of a human head. The reverse features a standing owl with the feathers of the head forming a beaded circle. The Hebrew inscription reads “Hezekiah the governor,” referring to the governor of the Persian province of Yehud (Judea).

Persian-period Yehud coin, from c. 350 BCE. The presence of graven images contradicts the laws of the Torah. Photo by Classical Numismatic Group, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons.

Only a century later, in the Hasmonean and Herodian periods, Judean leaders consciously refrained from using figurative imagery, which they replaced with decorative elements and more extensive texts—apparently adhering to the pentateuchal prohibition against graven images. Instead, the pictured bronze prutah of John Hyrcanus I from the late second century BCE features, on the reverse side, two cornucopias adorned with ribbons, and a pomegranate between them. Its obverse bears a lengthy Old Hebrew inscription inside a wreath that reads, “Yehohanan the High Priest and the Council of the Judeans.”

Hasmonean coin of John Hyrcanus I, from the late second century BCE. The absence of any human or animal figures seems to signal widespread acceptance of the laws of the Torah and to herald the origins of Judaism. Photo in public domain.

In sum, the archaeological evidence for observance of the laws of the Torah in the daily lives of ordinary Judeans seems to situate the origins of Judaism around the middle of the second century BCE.

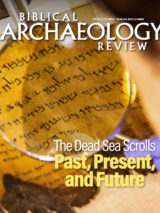

To delve into the intricacies of the textual and archaeological evidence for widespread observance of the laws of the Torah and the origins of Judaism, read Yonatan Adler’s article “ The Genesis of Judaism ,” published in the Winter 2022 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review .

—————— Subscribers: Read the full article “ The Genesis of Judaism ” by Yonatan Adler in the Winter 2022 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review .

Read more in Bible History Daily:

Original Maimonides Manuscript Goes Digital

All-Access Subscribers, read more in the BAS Library:

Biblical Law

Related Posts

Who Was Moses? Was He More than an Exodus Hero?

By: Biblical Archaeology Society Staff

Exodus in the Bible and the Egyptian Plagues

Were Mary and Joseph Married or Engaged at Jesus’ Birth?

By: Mark Wilson

How Was Jesus’ Tomb Sealed?

By: Megan Sauter

10 Responses

David Holland said >>Wondering if the rise of the Pharisaic movement was related to the forces driving the revolt<<

I wasn't alive in those days (contrary to what my kids say), and can only say they were the people's choice and party of the common people at least as early as Alexander Yannai ("Jannæus"). But I do know one thing:

The Pharisees were not happy that after the battles were history, the Khasmonayeem ("Hasmoneans") had both the kingship and the priesthood. Previously there was a balance of power: Kings were of the Davidic line, and priests were descendants of Aharon" {Aaron").

Now the priests, labeled "Sadducees" (derived from the ancient high priest Tzadok) controlled both powerful positions. Clashes were inevitable.

The monotheism of Judaism developed the same way as that of Islam by evolving from a polytheistic belief in many gods. Originally both Yahweh & Allah were only one of many different gods in Canaan & Arabia but eventually Yahweh was selected as the sole god to be worshiped just as Mohammed selected Allah to be the sole god when he formed Islam (using tenets and history from Judaism as a guide). This evolutionary path is glimpsed in the Bible when it had been reduced to one male god and one female goddess, Yahweh and Asherah, before Asherah was eliminated by, IIRC, King Josiah.

Baseless unadulterated nonsense! Allah (Satan) was invented around 600 AD and based on an apparent demonic encounter by Muhammad. The worship of Yahweh (God) dates back to the beginning of creation (albeit under some different name probably), certainly long before the entry of the Israelites into Canaan. As a consequence of Joshua’s conquest not eradicating all the Canaanites along with their idolatry, Asherah along with other Satanic idols were eventually incorporated into the Israelites’ worship, which was naturally followed by God’s judgment, resulting in said idols being eliminated, rightfully leaving only Yahweh left to be worshipped. The Bible blatantly contradicts your evidently false narrative!

Can’t help but think about the Maccabean Revolt when presented that suggested dating. Wondering if the rise of the Pharisaic movement was related to the forces driving the revolt, or perhaps a separate but related response to Hellenistic pressures.

As a believer (of which BAR has no understanding), I will state the obvious as found in the Bible. God does not change, therefore the laws of God were extant even before man was created. Avraham knew and understood the entirety of the statutes, commandments, and law (Gen. 26:5 …and Avraham kept my keeping, my commandments my stautes and my laws.) From that time on the law was observed. Since the commandments, statutes, and law were considered holy, you would not find extra biblical sources relating to it.

Jump to the time of Yeshua and it is clear the rabbinics had removed God from the law. The law was now on equal footing as the rabbinics and was being manipulated by the rabbinics, hence Yeshua’s issue with the Pharisees and the Sadducees. This why you will find extra biblical documents regarding the law just pior to and from this time forth. I think that maybe BAR scholars (as they call themselves) need to wake up a bit.

And that’s why he fornicated with Hagar.

He and Sarai were apparently following a known Babylonian law that called on the sterile wife to provide her husband with a servant to produce a child. The consequences of the situation make it clear it was a terrible idea. But one of the fascinating things about the Bible is that the heroes of the People of God actually make all kinds of mistakes and commit all kinds of infidelities, while God keeps trying to teach them and set them right, and is always faithful.

Interesting article but the Bible is clear that many did not follow the practices laid down by God to the people of Israel. Even kings are recorded as violating Gods laws. While finding graven images is evidence of those who did not follow Judaism, it is not proof that others were not following Judaism or not making graven images for religious reasons. And a lack of written material during this time stating their beliefs is understandably absent since any kind of writing except on clay or stone carvings is almost non-existent. Therefore, finding evidence that these laws were violated is not necessarily evidence that the laws did not exist during that time.

It’s funny that even scholars conveniently ignore the next words of the 10 Commandments. The prohibition against graven images is immediately followed by its rationale: “You shall not bow down to them nor serve them.” Ergo, it does not follow that Jews were prohibited to make coins that had a face carved into them, just as long as they didn’t worship them.

Well said. The Mt Ebal Curse Tablet appears to reinforce the Biblical events referred to in Deuteronomy and Joshua regarding the Israelites worshipping at Ebal, uttering the curses in the Law of Moses. It seems to date from the 1400s BCE (nice knowing ya, Ramesside Exodus theory), mentions Yahweh by name 4 times, written in Proto-Sinaitic script. Michael Shelomo Bar-Ron’s recent translations of the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions also support the historicity of Exodus-related events.

Write a Reply or Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Recent Blog Posts

Did Jesus Exist? Searching for Evidence Beyond the Bible

OnSite: The Via Dolorosa

Jesus’ Last Supper Still Wasn’t a Passover Seder Meal

Must-read free ebooks.

50 Real People In the Bible Chart

The Dead Sea Scrolls: Past, Present, and Future

Biblical Peoples—The World of Ancient Israel

Who Was Jesus? Exploring the History of Jesus’ Life

Want more bible history.

Sign up to receive our email newsletter and never miss an update.

By submitting above, you agree to our privacy policy .

All-Access Pass

Dig into the world of Bible history with a BAS All-Access membership. Biblical Archaeology Review in print. AND online access to the treasure trove of articles, books, and videos of the BAS Library. AND free Scholar Series lectures online. AND member discounts for BAS travel and live online events.

Signup for Bible History Daily to get updates!

Select Page

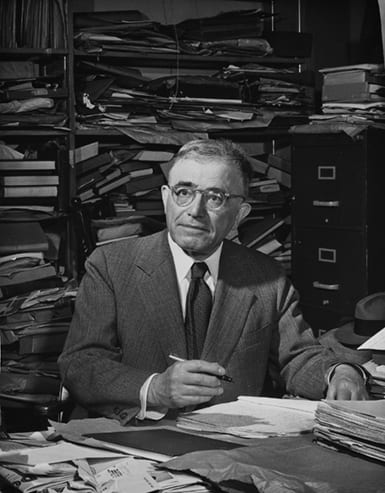

George Foot Moore (1851–1931) by Ignaz Marcel Gaugengigl. Harvard University Portrait Collection, gift of friends and colleagues of Dr. Moore to the Divinity School, 1926, h348, photo by Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Leaving aside more recent figures, the most impressive scholar of Hebraica in the history of Harvard is surely George Foot Moore (1851–1931), who served as Professor of the History of Religion from 1902 to 1928. And a remarkably capacious concept of religion he had: the first book of his two-volume History of Religions (1920) treated China, Japan, Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria, India, Persia, Greece, and Rome, and the second focused on Judaism, Christianity, and Mohammedanism ( sic ). Even granting the obvious fact that far less was known about most of those traditions then than now and that the methodological and theoretical frameworks were more limited, one cannot come away from Moore’s study unimpressed with the command of historical and textual detail it exhibits and the author’s eagerness to be fair to the religions on which he wrote. In a memoir of Moore published soon after his death, his colleague (and sometime dean) William Wallace Fenn observed that “it was often said that he could have taught any course in the curriculum of the Theology School, except those listed under Practical Theology and Social Ethics, quite as satisfactorily as the professor who actually offered it.” 14 Personally, I am confident in the judgment that Fenn intended his comment to reflect on Moore rather than on his colleagues.

Moore came to his phenomenal Hebraic competence naturally. Fenn reports of his grandfather, the Reverend George Foot, that “largely by independent study, he mastered Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and French” and that, having taught his daughter (Moore’s mother) Hebrew, the two of them had read the Hebrew Bible through in the original seven times before she was married. 15 Moore’s own formal education was strikingly short. Largely self-taught like his grandfather, he went into the pastorate after graduating Yale in two years and Union Theological Seminary in New York in one.

Into the pastorate but not out of scholarship. Serving a church in Zanesville, Ohio (1878–1883), he took up the study of rabbinic Hebrew with a local rabbi. His comments about the experience tell us much about both Moore himself and the type of study the two undertook:

It was an old-fashioned training. Its methods were doubtless of a kind which our pedagogical experts would regard as altogether obsolete; but it accomplished its end, which is, after all, the final test of the efficiency of a method. In one respect it differed widely from that of our schools; unsophisticated by educational psychology, the yeshiva-trained teacher, like his predecessors in the great age of classical learning in Western Europe, naively assumed that the object of studying a subject was to know it, not to acquire a certificate of having been through it. In that antiquated education the memory was systematically trained, not methodologically ruined. 16

Moore pursued Modern Hebrew at the same time, 17 something that to this day cannot be said of most scholars of the Hebrew Bible.

George Foot Moore became a leading figure in the scholarship of the Hebrew Bible, playing a major role in the importation of innovative German scholarship into the United States; his commentary on Judges (1895) is still considered a classic. 18

But it is primarily in the realm of rabbinic Judaism that he left his mark. His three-volume study, Judaism in the First Centuries of the Christian Era: The Age of the Tannaim (1927–1930), is an extraordinary accomplishment, though dated in important ways now. For our purposes, I would like instead to concentrate on “Christian Writers on Judaism,” a long essay that he published in Harvard Theological Review (of which he was a founding editor) in 1921. 19 For reasons we shall see, it remains highly instructive.

The opening sentence tells it all: “Christian interest in Jewish literature has always been apologetic or polemic rather than historical.” 20 Whereas in “early Christian apologetic . . . the controversial points were the interpretation and application of passages in the Old Testament” to Jesus, “the discussion in the Middle Ages . . . assumed a more learned character in the endeavor to demonstrate that Christian doctrines were supported by the authentic Jewish tradition . . . or by the mostly highly reputed Jewish interpreters.” 21 (About this, Moore, perhaps with an eye to scholarship in his own day, dryly remarks, “Whatever its value otherwise, it had at least one good result—it led to a much more zealous and assiduous study of Judaism than any purely scientific interest would have inspired.” 22 ) Later, in the age of the Reformation, Protestants endeavored to show “that on the issues in debate between Protestants and Catholics the Jews were on the Protestant side.” In the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, however, “a broader interest in learning for its own sake as well as its uses prevailed . . . and led . . . to the creation of a great body of learned literature in every branch of Hebrew antiquities.” 23

In the case of the revival of Christian study of Judaism in the nineteenth century, Moore writes, “the actuating motive was to find in it the milieu of early Christianity” and, more ominously, “to exhibit the system of Palestinian Jewish theology in the first three or four centuries of our era as the antithesis of Christian theology and religion as they were taught in certain contemporary German schools.” 24 There thus emerged the notion that the Talmudic rabbis subscribed to an “abstract monotheism” by which they “exalted [God] out of this world, which, like an absentee proprietor, he administered henceforth by agents.” And thus there emerged as well the charge of “legalism,” which according to Moore, (writing, remember, in 1921) “for the last fifty years has become the very definition and the all-sufficient condemnation of Judaism.” Whereas before this, “Concretely Jewish observances are censured or ridiculed . . . ‘legalism’ as a system of religion, not to say as the essence of Judaism, no one seems to have discovered.” 25

Whatever it was that first impelled the young Moore to study with that rabbi in Zanesville, by the time he had become a mature scholar his research compelled him to recognize that the reflexive anti-Judaism of the Christian community was in urgent need of correction.

Moore’s own motivation was different. As one scholar puts it, “Moore did not attempt to establish connections between Judaism and Christianity, but”—and this was really quite revolutionary for a Christian scholar—“to present a composite and constructive view of Judaism in its own terms.” 26 Whatever it was that first impelled the young Moore to study with that rabbi in Zanesville, by the time he had become a mature scholar his research compelled him to recognize that the reflexive anti-Judaism of the Christian community was in urgent need of correction. As Fenn observes in his memoir, “Professor Moore . . . had come to believe that that popular conception of the Pharisees, although possibly true of some members of the sect, misrepresented them as a whole. He sometimes said to his friends: ‘If you and I had been living in Palestine in the first century of our era, we should have been Pharisees, I hope.’ ” 27

Although Judaism in the First Centuries of the Christian Era: The Age of the Tannaim remains an important compendium of rabbinic discussions, its assumptions are now, as mentioned, woefully out of date. For one thing, Moore failed to involve himself in sufficient depth in halakhah, or normative Jewish practice, the major focus of the Talmud and of much midrashic literature as well. 28 For another, he attributed a historically problematic normativity to rabbinic Judaism and failed to reckon with the vitality of its antecedents and competitors (although, in fairness, before the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered, this was a more understandable move). He also accepted attributions of statements to various figures uncritically, thus limiting the utility of his massive study to historians. 29 Jacob Neusner was thus right when he wrote of Moore’s great study in 1980,“What is constructed is a static exercise in dogmatic theology.” 30 But Neusner erred when he observed in the same piece, “Moore closed many doors; he opened none.” 31 In fact, he opened the door to a fresh view of ancient Judaism for scores of Christian scholars—a “view of Judaism in its own terms.”

Not that every Christian scholar was willing to walk through it, as we shall see.

Harry Austryn Wolfson (1887–1974). Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

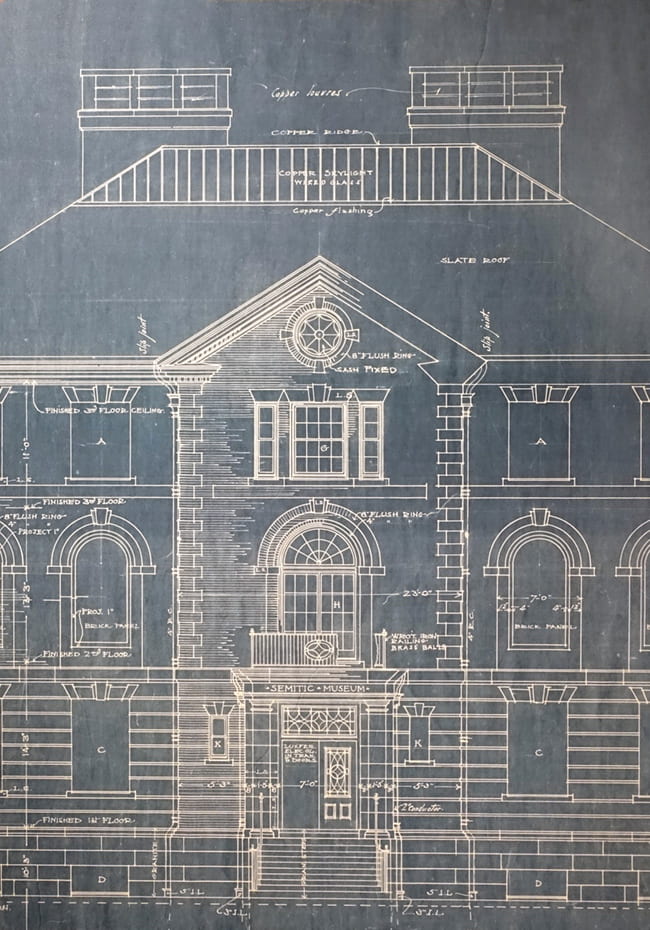

The attentive reader will have noticed one element that has so far been missing in these reflections on Jewish Studies at Harvard Divinity School: Jews. Around 1912 this was to change, when Lyon and Moore spotted a brilliant young undergraduate who had immigrated with his family from Lithuania (then under czarist Russia), eventually creating a position for him and helping, along with Harvard Law professor (and later Supreme Court justice) Felix Frankfurter, to raise the money to fund it. 32 That young man, Harry Wolfson, was to serve on the Harvard faculty from 1915 to 1958. Although he remained grateful to the Divinity School—he had once lived in Divinity Hall—to the end of his career, and spoke warmly of the institution and of Moore in particular, 33 with his appointment the center of Jewish Studies at Harvard shifted to the Semitic Department, forerunner of today’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations (NELC).

The shift was, in a sense, inevitable. As Isadore Twersky, Wolfson’s disciple and successor as Nathan Littauer Professor of Hebrew Literature and Philosophy and the founding director of the Center for Jewish Studies, wrote in an appreciation of his teacher in 1976:

In the past—and that means up to very recent times—the study of Judaica was ancillary, secondary, fragmentary, or derivative. Jewish studies were sometimes referred to as service departments whose task was to help illumine an obscurity in Tacitus or Posidonius, a midrash in Jerome, a Hebrew allusion in Dante. . . . The establishment of the Littauer chair at Harvard for Harry Wolfson gave Judaica its own station on the frontiers of knowledge and pursuit of truth, and began to redress the lopsidedness or imbalance of quasi-Jewish studies. 34

My sense, however, is that the importance of Jewish Studies’ having “its own station” was not well grasped in the Divinity School even as late as the time I arrived here (1988), and for quite an innocent reason: the major focus of faculty and students alike was on Christianity, and that meant that the farther the Jewish material was from intersecting with the church (especially with its two-testament Bible), the less relevance it seemed to have. Sometimes, it even appeared that the very existence of Jews and Judaism beyond antiquity was not altogether appreciated. I still remember that the catalogue cross-listed a NELC course called “Sources of Jewish History: 500–1750” in Area I, “Scripture and Interpretation”—this despite the fact that its earliest material dated to 650 years or so after the latest source in the Hebrew Bible!

Already in his essay of 1921, Moore had lamented the prominence of specialists in the New Testament among those with a penchant for commenting negatively about Judaism without, in the main, finding “it necessary to know anything about the rabbinical sources.” In a mode somewhat reminiscent of Twersky’s two generations later, he found intensely problematic the work of those whose “interest in Judaism also was not for its own sake, but for the light it might throw on the beginnings of Christianity.” 35 It is hard to gainsay this judgment, or to pronounce it obsolete. But there is another side to the issue. Absent the focus on Christianity in general and the New Testament in particular, it is hard to see how most of those laboring under anti-Jewish stereotypes originating in Christianity (whether the individuals profess Christianity or not) will ever have occasion to confront their bias and to approach Jewish sources on their own terms. In that sense, paradoxically, a more religiously diverse and pluralistic academy can prove not less but more subject to the old misconceptions, since the latter have a life and a momentum of their own, quite independent of the ancient theological claims in which they took shape.

Fully 56 years after Moore published “Christian Writers on Judaism,” a New Testament scholar, only this time another American eager to correct the record, opened his own study by terming Moore’s essay “an article which should be required reading for any Christian scholar who writes about Judaism.” 36 As E. P. Sanders went on to show in his now classic study, Paul and Palestinian Judaism: A Comparison of Patterns of Religion , in the intervening decades many eminent New Testament scholars had failed to understand the import of Moore’s work and continued to trade in the old prejudicial stereotypes, sometimes even citing Moore against what he was, in fact, saying. 37 Decades after Moore, even after the Holocaust, the old biases were alive and well.

To me, the pressing question is why. Why has the negative presentation of Judaism proven so powerful, so protean, and so tenacious?

One reason, I think, is that it intersects with social prejudice—theological anti-Judaism drawing energy from, and imparting energy to, social anti-Semitism. But another reason is that the old pattern presents a simple but enormously powerful psychological drama—the innocent and peace-loving Jesus murdered by his godless, hypocritical, and legalistic kinsmen. As for the perfidious malefactors themselves, they are rightfully scattered all over the world with no state of their own, surviving as involuntary witnesses to the truth of the gospel, as they “groan in grief over their lost kingdom and quake in fear under the sway of innumerable Christian peoples,” as Augustine had put it. 38

The drama is so powerful, in fact, that, as Jonathan Sacks, now retired as Chief Rabbi of the United Kingdom and the British Commonwealth, put it, “it is a virus—and like a virus it mutates.” In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, “religious anti-Judaism,” the variety that we have been considering, “mutated into racial anti-Semitism,” best known for its role in Nazism and the Holocaust. But now what Sacks calls “the second great mutation of anti-Semitism in modern times” is underway, a mutation “from racial anti-Semitism to religious anti-Zionism.” The new strain, he writes, “uses all the mediaeval myths—the Blood Libel, poisoning of wells, killers of the Lord’s anointed, incarnation of evil—transposed into a new key and context,” with the state of Israel as the great malefactor. 39 With the Jewish people no longer stateless, groaning in grief over their lost kingdom and quaking in fear under the sway of innumerable Christian peoples, the old evil is again loose in the world.

It is essential to understand that Sacks is not speaking of those who are critical of this or that Israeli policy, even sharply so. If he were, he would be accusing large segments of the Israeli populace and world Jewry alike. Helpful criteria for distinguishing criticism of Israel from anti-Semitism are given by Alan Dershowitz, now retired as Felix Frankfurter Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. “So long as criticism is comparative, contextual, and fair,” Dershowitz writes, “it should be encouraged, not disparaged. But when the Jewish nation is the only one criticized for faults that are far worse among other nations, such criticism crosses the line from fair to foul, from acceptable to anti-Semitic.” 40 Unfortunately, the long history of Christian anti-Semitism provides a rich and remarkably resilient resource for that singling out of the Jewish state for consistently and univocally negative judgments unreflective of the complexity of the historical facts. 41

This latest mutation of anti-Semitism has indeed produced a virulent strain; only time will tell how hearty it is. Remarkably, another central figure in the history of Jewish Studies at Harvard Divinity School spotted the danger early on. Krister Stendahl, (1921–2008), an influential New Testament scholar who became dean of Harvard Divinity School (1968–1979) and, later, a Lutheran bishop, wrote in these pages in the wake of the Six-Day War (1967):

In the months and years to come, difficult political problems in the Middle East call for solutions. Christians both in the West and in the East will weigh the proposals differently. But all of us should watch out for the ways in which the ancient venom of Christian anti-semitism might enter in. A militarily victorious and politically strong Israel cannot count on half as much good will as a threatened Jewish people in danger of its second holocaust. The situation bears watching. . . . The present political situation may well unleash a type of Christian attitude which identifies Judaism and Israel with materialism and lack of compassion, devoid of the Christian spirit of love. 42

But if the goal is to think comparatively and contextually and with fairness to the full range of facts, as Dershowitz recommends, then some small solace can be found in the history of scholarship on ancient Judaism and early Christianity since Moore, in which precisely that type of analysis has grown in strength (Stendahl’s own work is an example), 43 and dramatically so in the decades since Sanders voiced his lament. As always, it will take far more than scholarship to counter large cultural and social forces, but, in the face of the new challenge, scholars should underestimate neither their own responsibilities nor the lessons embedded in the history of their own disciplines and the general enrichment that can come when Judaism has its own station and the study of it is pursued for its own sake.

A postscript: Although I have not intended these reflections as comprehensive and have necessarily omitted reference to several notable figures, I cannot close without mentioning one more. My own teacher, Frank Moore Cross (1921–2012), taught at Harvard Divinity School from 1957 until his retirement in 1992, holding the Hancock Professorship, by then in NELC, from 1958. Trained, like his father, as a Presbyterian minister, Cross presided over a genuinely nonconfessional program, which produced a large number of the most prominent Jewish figures in what is now the senior generation of Hebrew Bible scholars. Like Stendahl a great admirer and supporter of Jewish scholarship, he invited a number of prominent scholars from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem to be visiting professors, including such influential figures as Moshe Goshen-Gottstein and Shemaryahu Talmon.

- This is also a tradition of immense historical importance to the emergence of ideas of religious tolerance in political thought, as brilliantly analyzed by Eric Nelson of Harvard’s Department of Government in The Hebrew Republic: Jewish Sources and the Transformation of European Political Thought (Harvard University Press, 2010).

- Samuel Eliot Morison, The Founding of Harvard College (Harvard University Press, 1935), 220–21. Morison thanks Harry A. Wolfson for tracking down the reference ( Mishneh Torah, Tefillah 11:14).

- Robert H. Pfeiffer, “The Teaching of Hebrew in Colonial America,” Jewish Quarterly Review 45 (1955): 363–73, at 369.

- Lee M. Friedman, “Judah Monis: First Instructor in Hebrew at Harvard University,” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 22 (1914): 1–24, at 2–3.

- See Shalom Goldman, God’s Sacred Tongue: Hebrew and the American Imagination (University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 41–45.

- “Rules and Statutes of the Professorships in the University at Cambridge” (Metcalf and Company, 1846), 7–8.

- William T. Baxter, The House of Hancock: Business in Boston, 1724–1775 (Harvard University Press, 1945), esp. 55–56, 69–74, and 114–18 .

- Baruch de Spinoza, A Theological-Political Tractate and Political Treatise (Dover Publications, 1951), 106 and 103. The Tractatus Theologico-Politicus was first published in 1670.

- www.harvardsquarelibrary.org/biographies/george-rapall-noyes . James de Normandie, “Memoir of Rev. Edward James Young, D.D.” in Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 44 (October 1910–June 1911): 529–42, at 531–32.

- D. G. Lyon, “Crawford Howell Toy,” Harvard Theological Review 13 (1920): 1–21.

- The name was changed in 1961 to Department of Near Eastern Languages and Literatures and then to its current name at some point in the early 1970s, when your humble—nay, overrated—scribe was a graduate student there.

- See David G. Lyon, “Semitic,” in The Development of Harvard University since the Inauguration of President Eliot, 1869–1929 , ed. Samuel Eliot Morison (Harvard University Press, 1930), 231–40.

- Ibid., 235.

- Willam Wallace Fenn, “George Foot Moore: A Memoir,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 64 (February 1932): 3–11, at 3.

- Quoted in Leo W. Schwarz, Wolfson of Harvard: Portrait of a Scholar (Jewish Publication Society of America, 5738/1978), 38–39, with no indication of the source of Moore’s quote.

- Samuel A. Meier, “Moore, George Foot (15 October 1851–16 May 1931),” American National Biography (online version, 2000), www.anb.org .

- George Foot Moore, “Christian Writers on Judaism,” Harvard Theological Review 14 (1921): 197–254.

- Ibid., 197.

- Ibid., 250.

- Ibid., 202.

- Ibid., 251. On this last point, see Nelson, The Hebrew Republic .

- Moore, “Christian Writers on Judaism,” 251–52. On the latter point, Moore refers specifically to Ferdinand Weber but certainly sees the pattern as much more general.

- Ibid., 252.

- E. P. Sanders, Paul and Palestinian Judaism: A Comparison of Patterns of Religion (Fortress Press, 1977), 56.

- Fenn, “George Foot Moore,” 8.

- For a fine introduction to this important subject, see now Chaim Saiman, Halakhah: The Rabbinic Idea of Law (Library of Jewish Studies; Princeton University Press, 2018).

- A very useful new introduction to the Talmud and contemporary scholarly approaches to it is Barry Scott Wimpfheimer, The Talmud: A Biography (Lives of Great Religious Books; Princeton University Press, 2018).

- Jacob Neusner, “ ‘Judaism’ after Moore: A Programmatic Statement,” Journal of Jewish Studies 31 (1980): 141–56, at 147. The whole article is a good discussion of what Neusner found inadequate in Moore’s procedures.

- Ibid., 142.

- Schwartz, Wolfson , 38–39, 49.

- Ibid., 171.

- Isadore Twersky, “Harry Austryn Wolfson, in Appreciation,” American Jewish Year Book 76 (1976): 99–111, at 107.

- Moore, “Christian Writers,” 241, n. 47. The second comment (on 241 itself) was made about Emil Schürer and Wilhelm Bousset.

- Sanders, Paul , 33.

- E.g., ibid., 55–56.

- Augustine, Contra Faustum 12:12.

- Jonathan Sacks, “A New Anti-Semitism,” Chesterton Review 30 (2004): 199–207, at 202–03. For more detail, in this case involving the revival of the adversus iudaeos tradition among liberal theologians in particular, see Adam Gregerman, “Old Wine in New Bottles: Liberation Theology and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict,” Journal of Ecumenical Studies 41 (2004): 313–40, esp. 333–39; idem, “Israel as the ‘Hermeneutical Jew’ in Protestant Statements on the Land and State of Israel: Four Presbyterian examples,” Israel Affairs 23 (2017): 773–93 (Gregerman is an alumnus of Harvard Divinity School); and Jonathan Rynhold, The Arab-Israeli Conflict in American Political Culture (Cambridge University Press, 2015), esp. 130–31. Of course, the religious and racial versions of anti-Semitism are hardly incompatible and can readily energize each other. On this, see Susannah Heschel, The Aryan Jesus: Christian Theologians and the Bible in Nazi Germany (Princeton University Press, 2008). The same can be said as well for the relationship of anti-Semitism and anti-Israelism.

- Alan Dershowitz, The Case for Israel (John Wiley & Sons, 2003), 1.

- For examples, see Gregerman, “Israel as the ‘Hermeneutical Jew.’ ” It is important to recognize that (1) a great many Christians have successfully rid themselves of the penchant to vilify or even demonize the Jews, and (2) one can be subject to that penchant without being a believing Christian.

- Krister Stendahl, “Judaism and Christianity II—After a Colloquium and a War,” Harvard Divinity Bulletin 1 (1967): 2–9, at 7. On the larger question of the range of Christian theological responses to the resumption of Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel, see, for example, Adam Gregerman, “Comparative Christian Hermeneutical Approaches to the Land Promises to Abraham,” CrossCurrents 64 (2014): 410–25.

- See especially Stendahl’s influential essay, “The Apostle Paul and the Introspective Conscience of the West,” Harvard Theological Review 56 (1963): 199–215, reprinted in Paul among Jews and Gentiles (Fortress Press, 1976), 78–96.

Jon D. Levenson is the Albert A. List Professor of Jewish Studies at HDS. His many books include Resurrection and the Restoration of Israel: The Ultimate Victory of the God of Life (Yale University Press, 2006), which won a National Jewish Book Award, and The Love of God: Divine Gift, Human Gratitude, and Mutual Faithfulness in Judaism (Princeton University Press, 2015).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

About | Commentary Guidelines | Harvard University Privacy | Accessibility | Digital Accessibility | Trademark Notice | Reporting Copyright Infringements Copyright © 2024 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved.

- Share full article

Opinion Guest Essay

The Great Rupture in American Jewish Life

Credit... Daniel Benneworth-Gray

Supported by

By Peter Beinart

Mr. Beinart is the editor at large of Jewish Currents and a journalist and writer who has written extensively on the Middle East, Jewish life and American foreign policy.

- March 22, 2024

F or the last decade or so, an ideological tremor has been unsettling American Jewish life. Since Oct. 7, it has become an earthquake. It concerns the relationship between liberalism and Zionism, two creeds that for more than half a century have defined American Jewish identity. In the years to come, American Jews will face growing pressure to choose between them.

They will face that pressure because Israel’s war in Gaza has supercharged a transformation on the American left. Solidarity with Palestinians is becoming as essential to leftist politics as support for abortion rights or opposition to fossil fuels. And as happened during the Vietnam War and the struggle against South African apartheid, leftist fervor is reshaping the liberal mainstream. In December, the United Automobile Workers demanded a cease-fire and formed a divestment working group to consider the union’s “economic ties to the conflict.” In January, the National L.G.B.T.Q. Task Force called for a cease-fire as well. In February, the leadership of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the nation’s oldest Black Protestant denomination, called on the United States to halt aid to the Jewish state. Across blue America, many liberals who once supported Israel or avoided the subject are making the Palestinian cause their own.

This transformation remains in its early stages. In many prominent liberal institutions — most significantly, the Democratic Party — supporters of Israel remain not only welcome but also dominant. But the leaders of those institutions no longer represent much of their base. The Democratic majority leader, Senator Chuck Schumer, acknowledged this divide in a speech on Israel on the Senate floor last week. He reiterated his longstanding commitment to the Jewish state, though not its prime minister. But he also conceded, in the speech’s most remarkable line, that he “can understand the idealism that inspires so many young people in particular to support a one-state solution” — a solution that does not involve a Jewish state. Those are the words of a politician who understands that his party is undergoing profound change.

The American Jews most committed to Zionism, the ones who run establishment institutions, understand that liberal America is becoming less ideologically hospitable. And they are responding by forging common cause with the American right. It’s no surprise that the Anti-Defamation League, which only a few years ago harshly criticized Donald Trump’s immigration policies, recently honored his son-in-law and former senior adviser, Jared Kushner.

Mr. Trump himself recognizes the emerging political split. “Any Jewish person that votes for Democrats hates their religion,” he said in an interview published on Monday. “They hate everything about Israel, and they should be ashamed of themselves because Israel will be destroyed.” It’s typical Trumpian indecency and hyperbole, but it’s rooted in a political reality. For American Jews who want to preserve their country’s unconditional support for Israel for another generation, there is only one reliable political partner: a Republican Party that views standing for Palestinian rights as part of the “woke” agenda.

The American Jews who are making a different choice — jettisoning Zionism because they can’t reconcile it with the liberal principle of equality under the law — garner less attention because they remain further from power. But their numbers are larger than many recognize, especially among millennials and Gen Z. And they face their own dilemmas. They are joining a Palestine solidarity movement that is growing larger, but also more radical, in response to Israel’s destruction of Gaza. That growing radicalism has produced a paradox: A movement that welcomes more and more American Jews finds it harder to explain where Israeli Jews fit into its vision of Palestinian liberation.

The emerging rupture between American liberalism and American Zionism constitutes the greatest transformation in American Jewish politics in half a century. It will redefine American Jewish life for decades to come.

“A merican Jews,” writes Marc Dollinger in his book “Quest for Inclusion: Jews and Liberalism in Modern America,” have long depicted themselves as “guardians of liberal America.” Since they came to the United States in large numbers around the turn of the 20th century, Jews have been wildly overrepresented in movements for civil, women’s, labor and gay rights. Since the 1930s, despite their rising prosperity, they have voted overwhelmingly for Democrats. For generations of American Jews, the icons of American liberalism — Eleanor Roosevelt, Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., Gloria Steinem — have been secular saints.

The American Jewish love affair with Zionism dates from the early 20th century as well. But it came to dominate communal life only after Israel’s dramatic victory in the 1967 war exhilarated American Jews eager for an antidote to Jewish powerlessness during the Holocaust. The American Israel Public Affairs Committee, which was nearly bankrupt on the eve of the 1967 war, had become American Jewry’s most powerful institution by the 1980s. American Jews, wrote Albert Vorspan, a leader of Reform Judaism, in 1988, “have made of Israel an icon — a surrogate faith, surrogate synagogue, surrogate God.”

Given the depth of these twin commitments, it’s no surprise that American Jews have long sought to fuse them by describing Zionism as a liberal cause. It has always been a strange pairing. American liberals generally consider themselves advocates of equal citizenship irrespective of ethnicity, religion and race. Zionism — or at the least the version that has guided Israel since its founding — requires Jewish dominance. From 1948 to 1966, Israel held most of its Palestinian citizens under military law; since 1967 it has ruled millions of Palestinians who hold no citizenship at all. Even so, American Jews could until recently assert their Zionism without having their liberal credentials challenged.

The primary reason was the absence from American public discourse of Palestinians, the people whose testimony would cast those credentials into greatest doubt. In 1984, the Palestinian American literary critic Edward Said argued that in the West, Palestinians lack “permission to narrate” their own experience. For decades after he wrote those words, they remained true. A study by the University of Arizona’s Maha Nassar found that of the opinion articles about Palestinians published in The New York Times and The Washington Post between 2000 and 2009, Palestinians themselves wrote roughly 1 percent.

But in recent years, Palestinian voices, while still embattled and even censored , have begun to carry. Palestinians have turned to social media to combat their exclusion from the press. In an era of youth-led activism, they have joined intersectional movements forged by parallel experiences of discrimination and injustice. Meanwhile, Israel — under the leadership of Benjamin Netanyahu for most of the past two decades — has lurched to the right, producing politicians so openly racist that their behavior cannot be defended in liberal terms.

Many Palestine solidarity activists identify as leftists, not liberals. But like the activists of the Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter movements, they have helped change liberal opinion with their radical critiques. In 2002, according to Gallup , Democrats sympathized with Israel over the Palestinians by a margin of 34 points. By early 2023, they favored the Palestinians by 11 points. And because opinion about Israel cleaves along generational lines, that pro-Palestinian skew is much greater among the young. According to a Quinnipiac University poll in November, Democrats under the age of 35 sympathize more with Palestinians than with Israelis by 58 points.

Given this generational gulf, universities offer a preview of the way many liberals — or “progressives,” a term that straddles liberalism and leftism and enjoys more currency among young Americans — may view Zionism in the years to come. Supporting Palestine has become a core feature of progressive politics on many campuses. At Columbia, for example, 94 campus organizations — including the Vietnamese Students Association, the Reproductive Justice Collective and Poetry Slam, Columbia’s “only recreational spoken word club” — announced in November that they “see Palestine as the vanguard for our collective liberation.” As a result, Zionist Jewish students find themselves at odds with most of their politically active peers.

Accompanying this shift, on campus and beyond, has been a rise in Israel-related antisemitism. It follows a pattern in American history. From the hostility toward German Americans during World War I to violence against American Muslims after Sept. 11 and assaults on Asian Americans during the Covid pandemic, Americans have a long and ugly tradition of expressing their hostility toward foreign governments or movements by targeting compatriots who share a religion, ethnicity or nationality with those overseas adversaries. Today, tragically, some Americans who loathe Israel are taking it out on American Jews. (Palestinian Americans, who have endured multiple violent hate crimes since Oct. 7, are experiencing their own version of this phenomenon.) The spike in antisemitism since Oct. 7 follows a pattern. Five years ago, the political scientist Ayal Feinberg, using data from 2001 and 2014, found that reported antisemitic incidents in the United States spike when the Israeli military conducts a substantial military operation.

Attributing the growing discomfort of pro-Israel Jewish students entirely to antisemitism, however, misses something fundamental. Unlike establishment Jewish organizations, Jewish students often distinguish between bigotry and ideological antagonism. In a 2022 study , the political scientist Eitan Hersh found that more than 50 percent of Jewish college students felt “they pay a social cost for supporting the existence of Israel as a Jewish state.” And yet, in general, Dr. Hersh reported, “the students do not fear antisemitism.”

Surveys since Oct. 7 find something similar. Asked in November in a Hillel International poll to describe the climate on campus since the start of the war, 20 percent of Jewish students answered “unsafe” and 23 percent answered “scary.” By contrast, 45 percent answered “uncomfortable” and 53 percent answered “tense.” A survey that same month by the Jewish Electorate Institute found that only 37 percent of American Jewish voters ages 18 to 35 consider campus antisemitism a “very serious problem,” compared with nearly 80 percent of American Jewish voters over the age of 35.

While some young pro-Israel American Jews experience antisemitism, they more frequently report ideological exclusion. As Zionism becomes associated with the political right, their experiences on progressive campuses are coming to resemble the experiences of young Republicans. The difference is that unlike young Republicans, most young American Zionists were raised to believe that theirs was a liberal creed. When their parents attended college, that assertion was rarely challenged. On the same campuses where their parents felt at home, Jewish students who view Zionism as central to their identity now often feel like outsiders.

In 1979, Mr. Said observed that in the West, “to be a Palestinian is in political terms to be an outlaw.” In much of America — including Washington — that remains true. But within progressive institutions one can glimpse the beginning of a historic inversion. Often, it’s now the Zionists who feel like outlaws.

G iven the organized American Jewish community’s professed devotion to liberal principles, which include free speech, one might imagine that Jewish institutions would greet this ideological shift by urging pro-Israel students to tolerate and even learn from their pro-Palestinian peers. Such a stance would flow naturally from the statements establishment Jewish groups have made in the past. A few years ago, the Anti-Defamation League declared that “our country’s universities serve as laboratories for the exchange of differing viewpoints and beliefs. Offensive, hateful speech is protected by the Constitution’s First Amendment.”

But as pro-Palestinian sentiment has grown in progressive America, pro-Israel Jewish leaders have apparently made an exception for anti-Zionism. While still claiming to support free speech on campus, the ADL last October asked college presidents to investigate local chapters of Students for Justice in Palestine to determine whether they violated university regulations or state or federal laws, a demand that the American Civil Liberties Union warned could “chill speech” and “betray the spirit of free inquiry.” After the University of Pennsylvania hosted a Palestinian literature festival last fall, Marc Rowan, chair of the United Jewish Appeal-Federation of New York and chair of the board of advisers of Penn’s Wharton business school, condemned the university’s president for giving the festival Penn’s “imprimatur.” In December, he encouraged trustees to alter university policies in ways that Penn’s branch of the American Association of University Professors warn ed could “silence and punish speech with which trustees disagree.”

In this effort to limit pro-Palestinian speech, establishment Jewish leaders are finding their strongest allies on the authoritarian right. Pro-Trump Republicans have their own censorship agenda: They want to stop schools and universities from emphasizing America’s history of racial and other oppression. Calling that pedagogy antisemitic makes it easier to ban or defund. At a much discussed congressional hearing in December featuring the presidents of Harvard, Penn and M.I.T., the Republican representative Virginia Foxx noted that Harvard teaches courses like “Race and Racism in the Making of the United States as a Global Power” and hosts seminars such as “Scientific Racism and Anti-Racism: History and Recent Perspectives” before declaring that “Harvard also, not coincidentally but causally, was ground zero for antisemitism following Oct. 7.”

Ms. Foxx’s view is typical. While some Democrats also equate anti-Zionism and antisemitism, the politicians and business leaders most eager to suppress pro-Palestinian speech are conservatives who link such speech to the diversity, equity and inclusion agenda they despise. Elise Stefanik, a Trump acolyte who has accused Harvard of “caving to the woke left,” became the star of that congressional hearing by demanding that Harvard’s president , Claudine Gay, punish students who chant slogans like “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.” (Ms. Gay was subsequently forced to resign following charges of plagiarism.) Elon Musk, who in November said that the phrase “from the river to the sea” was banned from his social media platform X (formerly Twitter), the following month declared , “D.E.I. must die.” The first governor to ban Students for Justice in Palestine chapters at his state’s public universities was Florida’s Ron DeSantis, who has also signed legislation that limits what those universities can teach about race and gender.

This alignment between the American Jewish organizational establishment and the Trumpist right is not limited to universities. If the ADL has aligned with Republicans who want to silence “woke” activists on campus, AIPAC has joined forces with Republicans who want to disenfranchise “woke” voters. In the 2022 midterm elections, AIPAC endorsed at least 109 Republicans who opposed certifying the 2020 election. For an organization single-mindedly focused on sustaining unconditional U.S. support for Israel, that constituted a rational decision. Since Republican members of Congress don’t have to mollify pro-Palestinian voters, they’re AIPAC’s most dependable allies. And if many of those Republicans used specious claims of Black voter fraud to oppose the democratic transfer of power in 2020 — and may do so again — that’s a price AIPAC seems to be prepared to pay.

F or the many American Jews who still consider themselves both progressives and Zionists, this growing alliance between leading Zionist institutions and a Trumpist Republican Party is uncomfortable. But in the short term, they have an answer: politicians like President Biden, whose views about both Israel and American democracy roughly reflect their own. In his speech last week, Mr. Schumer called these liberal Zionists American Jewry’s “silent majority.”

For the moment he may be right. In the years to come, however, as generational currents pull the Democratic Party in a more pro-Palestinian direction and push America’s pro-Israel establishment to the right, liberal Zionists will likely find it harder to reconcile their two faiths. Young American Jews offer a glimpse into that future, in which a sizable wing of American Jewry decides that to hold fast to its progressive principles it must jettison Zionism and embrace equal citizenship in Israel and Palestine, as well as in the United States.

For an American Jewish establishment that equates anti-Zionism with antisemitism, these anti-Zionist Jews are inconvenient. Sometimes, pro-Israel Jewish organizations pretend they don’t exist. In November, after Columbia suspended two anti-Zionist campus groups, the ADL thanked university leaders for acting “to protect Jewish students” — even though one of the suspended groups was Jewish Voice for Peace. At other times, pro-Israel leaders describe anti-Zionist Jews as a negligible fringe. If American Jews are divided over the war in Gaza, Andrés Spokoiny, the president and chief executive of the Jewish Funders Network, an organization for Jewish philanthropists, declared in December, “the split is 98 percent/2 percent.”

Among older American Jews, this assertion of a Zionist consensus contains some truth. But among younger American Jews, it’s false. In 2021, even before Israel’s current far-right government took power, the Jewish Electorate Institute found that 38 percent of American Jewish voters under the age of 40 viewed Israel as an apartheid state, compared with 47 percent who said it’s not. In November, it revealed that 49 percent of American Jewish voters ages 18 to 35 opposed Mr. Biden’s request for additional military aid to Israel. On many campuses, Jewish students are at the forefront of protests for a cease-fire and divestment from Israel. They don’t speak for all — and maybe not even most — of their Jewish peers. But they represent far more than 2 percent.

These progressive Jews are, as the U.S. editor of The London Review of Books, Adam Shatz, noted to me, a double minority. Their anti-Zionism makes them a minority among American Jews, while their Jewishness makes them a minority in the Palestine solidarity movement. Fifteen years ago, when the liberal Zionist group J Street was intent on being the “ blocking back ” for President Barack Obama’s push for a two-state solution, some liberal Jews imagined themselves leading the push to end Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Today, the prospect of partition has diminished, and Palestinians increasingly set the terms of activist criticism of Israel. That discourse, which is peppered with terms like “apartheid” and “decolonization," is generally hostile to a Jewish state within any borders.

There’s nothing antisemitic about envisioning a future in which Palestinians and Jews coexist on the basis of legal equality rather than Jewish supremacy. But in pro-Palestine activist circles in the United States, coexistence has receded as a theme. In 1999, Mr. Said argued for “a binational Israeli-Palestinian state” that offered “self-determination for both peoples.” In his 2007 book, “One Country,” Ali Abunimah, a co-founder of The Electronic Intifada, an influential source of pro-Palestine news and opinion, imagined one state whose name reflected the identities of both major communities that inhabit it. The terms “‘Israel’ and ‘Palestine’ are dear to those who use them and they should not be abandoned,” he argued. “The country could be called Yisrael-Falastin in Hebrew and Filastin-Isra’il in Arabic.”

In recent years, however, as Israel has moved to the right, pro-Palestinian discourse in the United States has hardened. The phrase “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,” which dates from the 1960s but has gained new prominence since Oct. 7, does not acknowledge Palestine and Israel’s binational character. To many American Jews, in fact, the phrase suggests a Palestine free of Jews. It sounds expulsionist, if not genocidal. It’s an ironic charge, given that it is Israel that today controls the land between the river and the sea, whose leaders openly advocate the mass exodus of Palestinians and that the International Court of Justice says could plausibly be committing genocide in Gaza.

Palestinian scholars like Maha Nassar and Ahmad Khalidi argue that “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” does not imply the subjugation of Jews. It instead reflects the longstanding Palestinian belief that Palestine should have become an independent country when released from European colonial control, a vision that does not preclude Jews from living freely alongside their Muslim and Christian neighbors. The Jewish groups closest to the Palestine solidarity movement agree: Jewish Voice for Peace’s Los Angeles chapter has argued that the slogan is no more anti-Jewish than the phrase “Black lives matter” is anti-white. And if the Palestine solidarity movement in the United States calls for the genocide of Jews, it’s hard to explain why so many Jews have joined its ranks. Rabbi Alissa Wise, an organizer of Rabbis for Cease-Fire, estimates that other than Palestinians, no other group has been as prominent in the protests against the war as Jews.

Still, imagining a “free Palestine” from the river to the sea requires imagining that Israeli Jews will become Palestinians, which erases their collective identity. That’s a departure from the more inclusive vision that Mr. Said and Mr. Abunimah outlined years ago. It’s harder for Palestinian activists to offer that more inclusive vision when they are watching Israel bomb and starve Gaza. But the rise of Hamas makes it even more essential.

Jews who identify with the Palestinian struggle may find it difficult to offer this critique. Many have defected from the Zionist milieu in which they were raised. Having made that painful transition, which can rupture relations with friends and family, they may be disinclined to question their new ideological home. It’s frightening to risk alienating one community when you’ve already alienated another. Questioning the Palestine solidarity movement also violates the notion, prevalent in some quarters of the American left, that members of an oppressor group should not second-guess representatives of the oppressed.

But these identity hierarchies suppress critical thought. Palestinians aren’t a monolith, and progressive Jews aren’t merely allies. They are members of a small and long-persecuted people who have not only the right but also the obligation to care about Jews in Israel, and to push the Palestine solidarity movement to more explicitly include them in its vision of liberation, in the spirit of the Freedom Charter adopted during apartheid by the African National Congress and its allies, which declared in its second sentence that “South Africa belongs to all who live in it, Black and white.”

For many American Jews, it is painful to watch their children’s or grandchildren’s generation question Zionism. It is infuriating to watch students at liberal institutions with which they once felt aligned treat Zionism as a racist creed. It is tempting to attribute all this to antisemitism, even if that requires defining many young American Jews as antisemites themselves.

But the American Jews who insist that Zionism and liberalism remain compatible should ask themselves why Israel now attracts the fervent support of Representative Stefanik but repels the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the United Automobile Workers. Why it enjoys the admiration of Elon Musk and Viktor Orban but is labeled a perpetrator of apartheid by Human Rights Watch and likened to the Jim Crow South by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Why it is more likely to retain unconditional American support if Mr. Trump succeeds in turning the United States into a white Christian supremacist state than if he fails.

For many decades, American Jews have built our political identity on a contradiction: Pursue equal citizenship here; defend group supremacy there. Now here and there are converging. In the years to come, we will have to choose.

Peter Beinart ( @PeterBeinart ) is a professor of journalism and political science at the Newmark School of Journalism at the City University of New York. He is also the editor at large of Jewish Currents and writes The Beinart Notebook , a weekly newsletter.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

Advertisement

Trending Topics:

- Say Kaddish Daily

- Passover 2024

Why I Converted to Judaism

My involvement with Judaism began with a Jewish boyfriend, but I ultimately converted for myself.

By Rabbi Heidi Hoover

That morning I had immersed in a mikveh, the Jewish ritual bath, and my declaration in front of the congregation concluded my conversion to Judaism.

As I left services that momentous evening, an older woman said to me, “Why would you want to convert to this?”

I didn’t know her. I didn’t know her story or anything about her experience of Judaism. I only know that while she hadn’t rejected Judaism, she also couldn’t understand why someone would affirmatively choose it. I imagine she may have experienced anti-Semitism, or had some other negative feeling related to her Judaism such that she considered being Jewish a mixed blessing — or maybe not a blessing at all.

People often assume that most Jews by choice convert because they have a partner or spouse who is Jewish. And while it’s true that my involvement with Judaism began with a Jewish boyfriend— now my husband of 28 years and the father of our two children — as Reform Jews, I would not have had to convert to participate in Jewish life and raise Jewish children. I converted because I wanted to be a Jew — for myself, separate from my relationship with my husband.

There are a number of reasons why I was attracted to Judaism and ultimately converted.

Growing up Lutheran, my religious practice was centered in the church. Aside from reciting grace before meals, any rituals that took place at home — Christmas trees or Easter eggs, for example — were essentially secular rituals that came to be associated with Christian holidays. The religious parts of the holidays were celebrated at church.

But for Jews, so much religious ritual takes place at home, from Shabbat candles to the Hanukkah menorah to the Passover seder to the sukkah we build in the fall. I love how much home-based ritual there is.

Judaism is also a great religion for kids. Take Passover , for example. The point of our Passover celebration is to teach the story of the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt to our children. When the rabbis developed the Passover seder in the first century CE, they used food as symbols for the different parts of the story. What better way to teach people than to use food? It’s genius.

I also find Jewish traditions to be very sensible. They seem to meet people where they are on the level of basic human needs. When someone very close to you dies, you sit shiva . For seven days (though many people only observe it for three days), you stay home. You don’t go out, you don’t shower, you don’t look in the mirror. People bring you food and sit with you in your grief. It strikes me that this is exactly what a lot of people need in that situation, and our tradition developed to give it to them.

Another example: At Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur , we confess our sins and ask forgiveness. But Judaism doesn’t consider humans to be essentially bad or sinful—rather, it considers us to be humans, and part of being human is to make mistakes, to sometimes do things that are wrong. So you make amends and you ask for forgiveness, and you go on trying to be a decent person in the world.

Judaism also focuses on behavior more than belief (though belief also matters). We focus on doing the best we can in this world instead of looking toward a reward after we die. And we recognize that we cannot understand God or know what God is like, so there is no dictated way to be in relationship with God.

Every Jew is free to determine their own relationship with God. If that relationship is primarily intellectual rather than emotional, that’s fine. When I first got involved with Judaism, that was how I was most comfortable relating to the divine, so it gave me a way in.

Finally, Judaism values questioning and learning. Jews delve deep into our sacred texts, wrestling with them and finding meaning in them for ourselves. There are many ways to understand our texts, and different interpretations — even contradictory ones — can coexist and be valid. I love that — and it’s so amazing for me to discover new interpretations. Every time, it feels like a revelation from God.

After I converted, I became a rabbi , and now I have the opportunity to open doors for others interested in Judaism, both Jewish and not. My motivations for conversion are not the same as other converts, and that is as it should be.

Jewish tradition is incredibly rich and deep, with so much that is worth exploring. Those who come to Judaism as adults often bring a different perspective than those who were born Jewish and grew up as Jews. The experience of those who convert isn’t better or worse: it’s just different. Every Jew, whether born Jewish or Jewish by conversion, brings more richness to our tradition.

Rabbi Heidi Hoover is the spiritual leader of Beth Shalom v’Emeth Reform Temple in Brooklyn, New York.

Are you considering conversion to Judaism? Sign up here for a special email series that will guide you through everything you need to know.

Join Our Newsletter

Empower your Jewish discovery, daily

Discover More

Tractate Gittin

Convert son of a convert.

Tractate Kiddushin

Kiddushin 73

How to avoid being pelted with etrogs.

Saving Judaism.

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essay Examples >

- Essays Topics >

- Essay on Countries

Judaism Essay

Type of paper: Essay

Topic: Countries , Judaism , Religion , History , Middle East , Holocaust , God , Belief

Published: 03/20/2020

ORDER PAPER LIKE THIS

Judaism is among the oldest religions in history. The origin of the religion can be traced back to nearly four thousand years whereby the religion was initially practiced near Canaan, that is the modern day Palestine and Israel. The religion is said to have similar traits as the beliefs and practices of the Jewish or Israeli people who were rescued from Egyptian slavery by God. The heritage of the Jewish religion practices and beliefs is reflected on the covenant that God made with Moses. The beliefs and practices of Judaism including the belief in one God, eternal afterlife and Holy Scriptures and narratives are similar to those of other major religions mainly Christianity and Islam. The only difference is presented in terms of how each religion interprets these beliefs (Cohen, 18). Judaism was the first religion to believe in monotheism, a belief in one supreme God who controls the universe. Jewish faith beliefs in God’s teachings contained in the Tanakh, which is the Hebrew bible particularly Torah that consists of the first five books of the Christians bible. Other beliefs include the sacred narratives especially about creation, and the redemption and exodus from slavery; rituals and ceremonies especially sacrifices, sacred space of worship which is the synagogue, and devotion and worship of one God. Despite being the oldest religion in history, Judaism followers have faced endless persecution and seclusion in the Diaspora which involved the countries dominated by Christians and Muslims, especially after several Jews willingly or forcefully migrated from their ancestral land in Eretz Israel. After settling in new countries after moving from their homeland, few Jews assimilated with the residents in the Diaspora while others were persecuted or fled to tertiary countries after a prolonged seclusion in anti-Jewish or anti-Semitic countries such as France and Germany. The persecution of Jews in Islamic countries has been in existence for a long time especially as a result of the belief that Islam is the only true religion. For instance, the Jewish persecution by Islamic believers can be traced to historical events such as the public execution that involved crucifying of a Jewish vizier Joseph HaNagid on December 1066 in Granada, Spain. A similar case occurred in 1465 at Fez, morocco where thousands of Jews were slaughtered with a claim that a Jewish Vizier had inappropriately treated a Muslim woman. Such cases have occurred in history with massive slaughters of Jewish people and destruction of synagogues in Muslim countries with the period between eighth to nineteenth centuries being the most intense (Bergen, 63). The persecution became rampant especially as a result of the Israel-Palestine clashes, with the recent massacre occurring in 1940’s in Iraq, Syria, Libya, Egypt and Yemen, thus resulting in mass exodus of the Diaspora Jews living in Islamic populated countries. The systematic mass killing of the Jews by the German Nazis during the holocaust period is one of the historical significance of the persecution of Judaism believers in the Diaspora. According to the Nazis, Germans were superior racially and as such, the presence of Jews and other minor races such as Gypsies, and Slavic’s people was a threat to the superiority of the Germans, and thus, they had to be executed or segregated. According to Bergen (156), the Nazis and other European collaborators killed millions of Jews in their ‘final solution’ strategy between 1941 and 1945. By the end of the World War II, approximately seven hundred Jews had survived the holocaust and these immigrated to Israel and other allied countries such as the US. These series of events indicates that the ongoing religious and social conflicts that have created hatred even in the modern world have existed for a long time. Thus, unless the people learn to respect and appreciate religious diversity, the existence of hatred on the basis of religious beliefs is likely to continue.

Works Cited

Bergen, Doris. War & Genocide: A Concise History of the Holocaust. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003. Print Cohen, Shaye. The Beginnings of Jewishness: Boundaries, Varieties, Uncertainties, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999. Print

Cite this page

Share with friends using:

Removal Request

Finished papers: 229

This paper is created by writer with

ID 281480444

If you want your paper to be:

Well-researched, fact-checked, and accurate

Original, fresh, based on current data

Eloquently written and immaculately formatted

275 words = 1 page double-spaced

Get your papers done by pros!

Other Pages

Free essay on sampling, characters literature review, transcription landscape essay, free essay on americas industrial revolution, example of health fitness critical thinking, good research paper on brief background, example of research paper on praxis paper, following reasons were there which caused the failure of establishment of any joint essay samples, example of understanding becker using four part framework essay, nonverbal functions essay examples, good example of civil war essay, free self evaluation course work example, example of essay on scientific communication paper, free research paper on project and portfolio management historical current and future practices, example of sungmin cho research paper, example of an analysis of the three characters in poe 039 s stories including an analysis research paper, good world religion essay example, dear sir or madam essay example, violence essay sample, good research paper on united farm workers of america, free political violence essay example, environmental and urban economics research paper example, exubera essays, fern essays, ezrin essays, diclofenac essays, biliary essays, alkaline essays, chromatograph essays, biopsychology essays, consumer behavior argumentative essays, the chosen argumentative essays, the canterbury tales argumentative essays, elephant argumentative essays, search engine argumentative essays, common law argumentative essays, pearl harbor argumentative essays, balance sheet argumentative essays, george washington argumentative essays, precision argumentative essays, legend argumentative essays, regeneration argumentative essays.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

- Email Signup

Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology

Judaism Introduction

Religions of the World and Ecology Series

Judaism and ecology.