- Tips & Guides

How To Avoid Using “We,” “You,” And “I” in an Essay

- Posted on October 27, 2022 October 27, 2022

Maintaining a formal voice while writing academic essays and papers is essential to sound objective.

One of the main rules of academic or formal writing is to avoid first-person pronouns like “we,” “you,” and “I.” These words pull focus away from the topic and shift it to the speaker – the opposite of your goal.

While it may seem difficult at first, some tricks can help you avoid personal language and keep a professional tone.

Let’s learn how to avoid using “we” in an essay.

What Is a Personal Pronoun?

Pronouns are words used to refer to a noun indirectly. Examples include “he,” “his,” “her,” and “hers.” Any time you refer to a noun – whether a person, object, or animal – without using its name, you use a pronoun.

Personal pronouns are a type of pronoun. A personal pronoun is a pronoun you use whenever you directly refer to the subject of the sentence.

Take the following short paragraph as an example:

“Mr. Smith told the class yesterday to work on our essays. Mr. Smith also said that Mr. Smith lost Mr. Smith’s laptop in the lunchroom.”

The above sentence contains no pronouns at all. There are three places where you would insert a pronoun, but only two where you would put a personal pronoun. See the revised sentence below:

“Mr. Smith told the class yesterday to work on our essays. He also said that he lost his laptop in the lunchroom.”

“He” is a personal pronoun because we are talking directly about Mr. Smith. “His” is not a personal pronoun (it’s a possessive pronoun) because we are not speaking directly about Mr. Smith. Rather, we are talking about Mr. Smith’s laptop.

If later on you talk about Mr. Smith’s laptop, you may say:

“Mr. Smith found it in his car, not the lunchroom!”

In this case, “it” is a personal pronoun because in this point of view we are making a reference to the laptop directly and not as something owned by Mr. Smith.

Why Avoid Personal Pronouns in Essay Writing

We’re teaching you how to avoid using “I” in writing, but why is this necessary? Academic writing aims to focus on a clear topic, sound objective, and paint the writer as a source of authority. Word choice can significantly impact your success in achieving these goals.

Writing that uses personal pronouns can unintentionally shift the reader’s focus onto the writer, pulling their focus away from the topic at hand.

Personal pronouns may also make your work seem less objective.

One of the most challenging parts of essay writing is learning which words to avoid and how to avoid them. Fortunately, following a few simple tricks, you can master the English Language and write like a pro in no time.

Alternatives To Using Personal Pronouns

How to not use “I” in a paper? What are the alternatives? There are many ways to avoid the use of personal pronouns in academic writing. By shifting your word choice and sentence structure, you can keep the overall meaning of your sentences while re-shaping your tone.

Utilize Passive Voice

In conventional writing, students are taught to avoid the passive voice as much as possible, but it can be an excellent way to avoid first-person pronouns in academic writing.

You can use the passive voice to avoid using pronouns. Take this sentence, for example:

“ We used 150 ml of HCl for the experiment.”

Instead of using “we” and the active voice, you can use a passive voice without a pronoun. The sentence above becomes:

“150 ml of HCl were used for the experiment.”

Using the passive voice removes your team from the experiment and makes your work sound more objective.

Take a Third-Person Perspective

Another answer to “how to avoid using ‘we’ in an essay?” is the use of a third-person perspective. Changing the perspective is a good way to take first-person pronouns out of a sentence. A third-person point of view will not use any first-person pronouns because the information is not given from the speaker’s perspective.

A third-person sentence is spoken entirely about the subject where the speaker is outside of the sentence.

Take a look at the sentence below:

“In this article you will learn about formal writing.”

The perspective in that sentence is second person, and it uses the personal pronoun “you.” You can change this sentence to sound more objective by using third-person pronouns:

“In this article the reader will learn about formal writing.”

The use of a third-person point of view makes the second sentence sound more academic and confident. Second-person pronouns, like those used in the first sentence, sound less formal and objective.

Be Specific With Word Choice

You can avoid first-personal pronouns by choosing your words carefully. Often, you may find that you are inserting unnecessary nouns into your work.

Take the following sentence as an example:

“ My research shows the students did poorly on the test.”

In this case, the first-person pronoun ‘my’ can be entirely cut out from the sentence. It then becomes:

“Research shows the students did poorly on the test.”

The second sentence is more succinct and sounds more authoritative without changing the sentence structure.

You should also make sure to watch out for the improper use of adverbs and nouns. Being careful with your word choice regarding nouns, adverbs, verbs, and adjectives can help mitigate your use of personal pronouns.

“They bravely started the French revolution in 1789.”

While this sentence might be fine in a story about the revolution, an essay or academic piece should only focus on the facts. The world ‘bravely’ is a good indicator that you are inserting unnecessary personal pronouns into your work.

We can revise this sentence into:

“The French revolution started in 1789.”

Avoid adverbs (adjectives that describe verbs), and you will find that you avoid personal pronouns by default.

Closing Thoughts

In academic writing, It is crucial to sound objective and focus on the topic. Using personal pronouns pulls the focus away from the subject and makes writing sound subjective.

Hopefully, this article has helped you learn how to avoid using “we” in an essay.

When working on any formal writing assignment, avoid personal pronouns and informal language as much as possible.

While getting the hang of academic writing, you will likely make some mistakes, so revising is vital. Always double-check for personal pronouns, plagiarism , spelling mistakes, and correctly cited pieces.

You can prevent and correct mistakes using a plagiarism checker at any time, completely for free.

Quetext is a platform that helps you with all those tasks. Check out all resources that are available to you today.

Sign Up for Quetext Today!

Click below to find a pricing plan that fits your needs.

You May Also Like

Mastering the Basics: Understanding the 4 Types of Sentences

- Posted on April 5, 2024

Can You Go to Jail for Plagiarism?

- Posted on March 22, 2024 March 22, 2024

Empowering Educators: How AI Detection Enhances Teachers’ Workload

- Posted on March 14, 2024

The Ethical Dimension | Navigating the Challenges of AI Detection in Education

- Posted on March 8, 2024

How to Write a Thesis Statement & Essay Outline

- Posted on February 29, 2024 February 29, 2024

The Crucial Role of Grammar and Spell Check in Student Assignments

- Posted on February 23, 2024 February 23, 2024

Revolutionizing Education: The Role of AI Detection in Academic Integrity

- Posted on February 15, 2024

How Reliable are AI Content Detectors? Which is Most Reliable?

- Posted on February 8, 2024 February 8, 2024

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

Can You Use I or We in a Research Paper?

4-minute read

- 11th July 2023

Writing in the first person, or using I and we pronouns, has traditionally been frowned upon in academic writing . But despite this long-standing norm, writing in the first person isn’t actually prohibited. In fact, it’s becoming more acceptable – even in research papers.

If you’re wondering whether you can use I (or we ) in your research paper, you should check with your institution first and foremost. Many schools have rules regarding first-person use. If it’s up to you, though, we still recommend some guidelines. Check out our tips below!

When Is It Most Acceptable to Write in the First Person?

Certain sections of your paper are more conducive to writing in the first person. Typically, the first person makes sense in the abstract, introduction, discussion, and conclusion sections. You should still limit your use of I and we , though, or your essay may start to sound like a personal narrative .

Using first-person pronouns is most useful and acceptable in the following circumstances.

When doing so removes the passive voice and adds flow

Sometimes, writers have to bend over backward just to avoid using the first person, often producing clunky sentences and a lot of passive voice constructions. The first person can remedy this. For example:

Both sentences are fine, but the second one flows better and is easier to read.

When doing so differentiates between your research and other literature

When discussing literature from other researchers and authors, you might be comparing it with your own findings or hypotheses . Using the first person can help clarify that you are engaging in such a comparison. For example:

In the first sentence, using “the author” to avoid the first person creates ambiguity. The second sentence prevents misinterpretation.

When doing so allows you to express your interest in the subject

In some instances, you may need to provide background for why you’re researching your topic. This information may include your personal interest in or experience with the subject, both of which are easier to express using first-person pronouns. For example:

Expressing personal experiences and viewpoints isn’t always a good idea in research papers. When it’s appropriate to do so, though, just make sure you don’t overuse the first person.

When to Avoid Writing in the First Person

It’s usually a good idea to stick to the third person in the methods and results sections of your research paper. Additionally, be careful not to use the first person when:

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● It makes your findings seem like personal observations rather than factual results.

● It removes objectivity and implies that the writing may be biased .

● It appears in phrases such as I think or I believe , which can weaken your writing.

Keeping Your Writing Formal and Objective

Using the first person while maintaining a formal tone can be tricky, but keeping a few tips in mind can help you strike a balance. The important thing is to make sure the tone isn’t too conversational.

To achieve this, avoid referring to the readers, such as with the second-person you . Use we and us only when referring to yourself and the other authors/researchers involved in the paper, not the audience.

It’s becoming more acceptable in the academic world to use first-person pronouns such as we and I in research papers. But make sure you check with your instructor or institution first because they may have strict rules regarding this practice.

If you do decide to use the first person, make sure you do so effectively by following the tips we’ve laid out in this guide. And once you’ve written a draft, send us a copy! Our expert proofreaders and editors will be happy to check your grammar, spelling, word choice, references, tone, and more. Submit a 500-word sample today!

Is it ever acceptable to use I or we in a research paper?

In some instances, using first-person pronouns can help you to establish credibility, add clarity, and make the writing easier to read.

How can I avoid using I in my writing?

Writing in the passive voice can help you to avoid using the first person.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

3-minute read

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

2-minute read

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Using “I” in Academic Writing

Traditionally, some fields have frowned on the use of the first-person singular in an academic essay and others have encouraged that use, and both the frowning and the encouraging persist today—and there are good reasons for both positions (see “Should I”).

I recommend that you not look on the question of using “I” in an academic paper as a matter of a rule to follow, as part of a political agenda (see webb), or even as the need to create a strategy to avoid falling into Scylla-or-Charybdis error. Let the first-person singular be, instead, a tool that you take out when you think it’s needed and that you leave in the toolbox when you think it’s not.

Examples of When “I” May Be Needed

- You are narrating how you made a discovery, and the process of your discovering is important or at the very least entertaining.

- You are describing how you teach something and how your students have responded or respond.

- You disagree with another scholar and want to stress that you are not waving the banner of absolute truth.

- You need “I” for rhetorical effect, to be clear, simple, or direct.

Examples of When “I” Should Be Given a Rest

- It’s off-putting to readers, generally, when “I” appears too often. You may not feel one bit modest, but remember the advice of Benjamin Franklin, still excellent, on the wisdom of preserving the semblance of modesty when your purpose is to convince others.

- You are the author of your paper, so if an opinion is expressed in it, it is usually clear that this opinion is yours. You don’t have to add a phrase like, “I believe” or “it seems to me.”

Works Cited

Franklin, Benjamin. The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin . Project Gutenberg , 28 Dec. 2006, www.gutenberg.org/app/uploads/sites/3/20203/20203-h/20203-h.htm#I.

“Should I Use “I”?” The Writing Center at UNC—Chapel Hill , writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/should-i-use-i/.

webb, Christine. “The Use of the First Person in Academic Writing: Objectivity, Language, and Gatekeeping.” ResearchGate , July 1992, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb01974.x.

J.S.Beniwal 05 August 2017 AT 09:08 AM

I have borrowed MLA only yesterday, did my MAEnglish in May 2017.MLA is of immense help for scholars.An overview of the book really enlightened me.I should have read it at bachelor's degree level.

Your e-mail address will not be published

Dr. Raymond Harter 25 September 2017 AT 02:09 PM

I discourage the use of "I" in essays for undergraduates to reinforce a conversational tone and to "self-recognize" the writer as an authority or at least a thorough researcher. Writing a play is different than an essay with a purpose.

Osayimwense Osa 22 March 2023 AT 05:03 PM

When a student or writer is strongly and passionately interested in his or her stance and argument to persuade his or her audience, the use of personal pronoun srenghtens his or her passion for the subject. This passion should be clear in his/her expression. However, I encourage the use of the first-person, I, sparingly -- only when and where absolutely necessary.

Eleanor 25 March 2023 AT 04:03 PM

I once had a student use the word "eye" when writing about how to use pronouns. Her peers did not catch it. I made comments, but I think she never understood what eye was saying!

Join the Conversation

We invite you to comment on this post and exchange ideas with other site visitors. Comments are moderated and subject to terms of service.

If you have a question for the MLA's editors, submit it to Ask the MLA!

Table of Contents

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process, using first person in an academic essay: when is it okay.

- CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 by Jenna Pack Sheffield

Related Concepts: Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community ; First-Person Point of View ; Rhetorical Analysis; Rhetorical Stance ; The First Person ; Voice

In order to determine whether or not you can speak or write from the first-person point of view, you need to engage in rhetorical analysis. You need to question whether your audience values and accepts the first person as a legitimate rhetorical stance. Source:Many times, high school students are told not to use first person (“I,” “we,” “my,” “us,” and so forth) in their essays. As a college student, you should realize that this is a rule that can and should be broken—at the right time, of course.

By now, you’ve probably written a personal essay, memoir, or narrative that used first person. After all, how could you write a personal essay about yourself, for instance, without using the dreaded “I” word?

However, academic essays differ from personal essays; they are typically researched and use a formal tone . Because of these differences, when students write an academic essay, they quickly shy away from first person because of what they have been told in high school or because they believe that first person feels too informal for an intellectual, researched text. While first person can definitely be overused in academic essays (which is likely why your teachers tell you not to use it), there are moments in a paper when it is not only appropriate, but also more effective and/or persuasive to use first person. The following are a few instances in which it is appropriate to use first person in an academic essay:

- Including a personal anecdote: You have more than likely been told that you need a strong “hook” to draw your readers in during an introduction. Sometimes, the best hook is a personal anecdote, or a short amusing story about yourself. In this situation, it would seem unnatural not to use first-person pronouns such as “I” and “myself.” Your readers will appreciate the personal touch and will want to keep reading! (For more information about incorporating personal anecdotes into your writing, see “ Employing Narrative in an Essay .”)

- Establishing your credibility ( ethos ): Ethos is a term stemming back to Ancient Greece that essentially means “character” in the sense of trustworthiness or credibility. A writer can establish her ethos by convincing the reader that she is trustworthy source. Oftentimes, the best way to do that is to get personal—tell the reader a little bit about yourself. (For more information about ethos, see “ Ethos .”)For instance, let’s say you are writing an essay arguing that dance is a sport. Using the occasional personal pronoun to let your audience know that you, in fact, are a classically trained dancer—and have the muscles and scars to prove it—goes a long way in establishing your credibility and proving your argument. And this use of first person will not distract or annoy your readers because it is purposeful.

- Clarifying passive constructions : Often, when writers try to avoid using first person in essays, they end up creating confusing, passive sentences . For instance, let’s say I am writing an essay about different word processing technologies, and I want to make the point that I am using Microsoft Word to write this essay. If I tried to avoid first-person pronouns, my sentence might read: “Right now, this essay is being written in Microsoft Word.” While this sentence is not wrong, it is what we call passive—the subject of the sentence is being acted upon because there is no one performing the action. To most people, this sentence sounds better: “Right now, I am writing this essay in Microsoft Word.” Do you see the difference? In this case, using first person makes your writing clearer.

- Stating your position in relation to others: Sometimes, especially in an argumentative essay, it is necessary to state your opinion on the topic . Readers want to know where you stand, and it is sometimes helpful to assert yourself by putting your own opinions into the essay. You can imagine the passive sentences (see above) that might occur if you try to state your argument without using the word “I.” The key here is to use first person sparingly. Use personal pronouns enough to get your point across clearly without inundating your readers with this language.

Now, the above list is certainly not exhaustive. The best thing to do is to use your good judgment, and you can always check with your instructor if you are unsure of his or her perspective on the issue. Ultimately, if you feel that using first person has a purpose or will have a strategic effect on your audience, then it is probably fine to use first-person pronouns. Just be sure not to overuse this language, at the risk of sounding narcissistic, self-centered, or unaware of others’ opinions on a topic.

Recommended Readings:

- A Synthesis of Professor Perspectives on Using First and Third Person in Academic Writing

- Finding the Bunny: How to Make a Personal Connection to Your Writing

- First-Person Point of View

Brevity – Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence – How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow – How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity – Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style – The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority – How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

Can You Use First-Person Pronouns (I/we) in a Research Paper?

Research writers frequently wonder whether the first person can be used in academic and scientific writing. In truth, for generations, we’ve been discouraged from using “I” and “we” in academic writing simply due to old habits. That’s right—there’s no reason why you can’t use these words! In fact, the academic community used first-person pronouns until the 1920s, when the third person and passive-voice constructions (that is, “boring” writing) were adopted–prominently expressed, for example, in Strunk and White’s classic writing manual “Elements of Style” first published in 1918, that advised writers to place themselves “in the background” and not draw attention to themselves.

In recent decades, however, changing attitudes about the first person in academic writing has led to a paradigm shift, and we have, however, we’ve shifted back to producing active and engaging prose that incorporates the first person.

Can You Use “I” in a Research Paper?

However, “I” and “we” still have some generally accepted pronoun rules writers should follow. For example, the first person is more likely used in the abstract , Introduction section , Discussion section , and Conclusion section of an academic paper while the third person and passive constructions are found in the Methods section and Results section .

In this article, we discuss when you should avoid personal pronouns and when they may enhance your writing.

It’s Okay to Use First-Person Pronouns to:

- clarify meaning by eliminating passive voice constructions;

- establish authority and credibility (e.g., assert ethos, the Aristotelian rhetorical term referring to the personal character);

- express interest in a subject matter (typically found in rapid correspondence);

- establish personal connections with readers, particularly regarding anecdotal or hypothetical situations (common in philosophy, religion, and similar fields, particularly to explore how certain concepts might impact personal life. Additionally, artistic disciplines may also encourage personal perspectives more than other subjects);

- to emphasize or distinguish your perspective while discussing existing literature; and

- to create a conversational tone (rare in academic writing).

The First Person Should Be Avoided When:

- doing so would remove objectivity and give the impression that results or observations are unique to your perspective;

- you wish to maintain an objective tone that would suggest your study minimized biases as best as possible; and

- expressing your thoughts generally (phrases like “I think” are unnecessary because any statement that isn’t cited should be yours).

Usage Examples

The following examples compare the impact of using and avoiding first-person pronouns.

Example 1 (First Person Preferred):

To understand the effects of global warming on coastal regions, changes in sea levels, storm surge occurrences and precipitation amounts were examined .

[Note: When a long phrase acts as the subject of a passive-voice construction, the sentence becomes difficult to digest. Additionally, since the author(s) conducted the research, it would be clearer to specifically mention them when discussing the focus of a project.]

We examined changes in sea levels, storm surge occurrences, and precipitation amounts to understand how global warming impacts coastal regions.

[Note: When describing the focus of a research project, authors often replace “we” with phrases such as “this study” or “this paper.” “We,” however, is acceptable in this context, including for scientific disciplines. In fact, papers published the vast majority of scientific journals these days use “we” to establish an active voice. Be careful when using “this study” or “this paper” with verbs that clearly couldn’t have performed the action. For example, “we attempt to demonstrate” works, but “the study attempts to demonstrate” does not; the study is not a person.]

Example 2 (First Person Discouraged):

From the various data points we have received , we observed that higher frequencies of runoffs from heavy rainfall have occurred in coastal regions where temperatures have increased by at least 0.9°C.

[Note: Introducing personal pronouns when discussing results raises questions regarding the reproducibility of a study. However, mathematics fields generally tolerate phrases such as “in X example, we see…”]

Coastal regions with temperature increases averaging more than 0.9°C experienced higher frequencies of runoffs from heavy rainfall.

[Note: We removed the passive voice and maintained objectivity and assertiveness by specifically identifying the cause-and-effect elements as the actor and recipient of the main action verb. Additionally, in this version, the results appear independent of any person’s perspective.]

Example 3 (First Person Preferred):

In contrast to the study by Jones et al. (2001), which suggests that milk consumption is safe for adults, the Miller study (2005) revealed the potential hazards of ingesting milk. The authors confirm this latter finding.

[Note: “Authors” in the last sentence above is unclear. Does the term refer to Jones et al., Miller, or the authors of the current paper?]

In contrast to the study by Jones et al. (2001), which suggests that milk consumption is safe for adults, the Miller study (2005) revealed the potential hazards of ingesting milk. We confirm this latter finding.

[Note: By using “we,” this sentence clarifies the actor and emphasizes the significance of the recent findings reported in this paper. Indeed, “I” and “we” are acceptable in most scientific fields to compare an author’s works with other researchers’ publications. The APA encourages using personal pronouns for this context. The social sciences broaden this scope to allow discussion of personal perspectives, irrespective of comparisons to other literature.]

Other Tips about Using Personal Pronouns

- Avoid starting a sentence with personal pronouns. The beginning of a sentence is a noticeable position that draws readers’ attention. Thus, using personal pronouns as the first one or two words of a sentence will draw unnecessary attention to them (unless, of course, that was your intent).

- Be careful how you define “we.” It should only refer to the authors and never the audience unless your intention is to write a conversational piece rather than a scholarly document! After all, the readers were not involved in analyzing or formulating the conclusions presented in your paper (although, we note that the point of your paper is to persuade readers to reach the same conclusions you did). While this is not a hard-and-fast rule, if you do want to use “we” to refer to a larger class of people, clearly define the term “we” in the sentence. For example, “As researchers, we frequently question…”

- First-person writing is becoming more acceptable under Modern English usage standards; however, the second-person pronoun “you” is still generally unacceptable because it is too casual for academic writing.

- Take all of the above notes with a grain of salt. That is, double-check your institution or target journal’s author guidelines . Some organizations may prohibit the use of personal pronouns.

- As an extra tip, before submission, you should always read through the most recent issues of a journal to get a better sense of the editors’ preferred writing styles and conventions.

Wordvice Resources

For more general advice on how to use active and passive voice in research papers, on how to paraphrase , or for a list of useful phrases for academic writing , head over to the Wordvice Academic Resources pages . And for more professional proofreading services , visit our Academic Editing and P aper Editing Services pages.

- The Open University

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

Can I use 'we' and 'I' in my essay? Introducing corpus linguistics

This page was published over 6 years ago. Please be aware that due to the passage of time, the information provided on this page may be out of date or otherwise inaccurate, and any views or opinions expressed may no longer be relevant. Some technical elements such as audio-visual and interactive media may no longer work. For more detail, see how we deal with older content .

What is a corpus?

But what exactly is meant by a corpus? A corpus (plural corpora) is basically a collection of texts, selected and organised in a principled way, and stored on a computer so that you can search easily. It could be anything from a few hundred words (e.g. a collection of your Facebook status updates) or several billion words (e.g. corpora compiled from trawling webpages).

You can search corpora that already exist, using a 'concordancer' or other types of software, or you could even build your own corpus if you want to investigate a particular type of text and you can't find an existing corpus.

Googlefight

We're all now used to searching large collections of texts quickly. Every time you use a search engine you're effectively trawling through vast numbers of entries.

So why don't linguists just use Google as a large corpus to find out how language works? Searching the web works as a very rough and ready way of quickly getting a sense of how language items are used.

You might be interested in trying a 'Google fight' to resolve disputes over how frequently two words or phrases are used! Go to www.googlefight.com . Here's what I found when I searched for 'we' and 'I':

So 'I' wins the Googlefight. But what does this actually mean?

If you search the web using Google or another search engine, your search will include all sorts of webpages – and duplicates of webpages. You also don't have any idea about the kinds of text the word appears in or about the other words your search item is used with (the 'co-text').

If we want to know whether 'we' is more common than 'I' in student essays, for example, looking on Google wouldn't be a very good way to go about it. And if we wanted to know if one group of students (for example Engineering students) use 'we' in their academic writing more than another group (such as History students) then an internet search wouldn't be any help at all.

To answer the question in the title to this article, we'd get a more accurate result by searching a collection of student writing such as the British Academic Written English or 'BAWE' corpus (pronounced 'boar' like the animal).

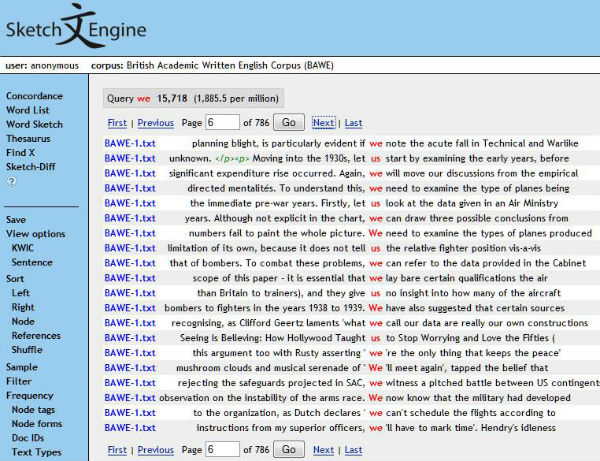

This corpus contains not just essays but also lab reports, case studies, literature reviews, and other types of writing that undergraduate and masters students do at university. Here I've used the free site Sketch Engine Open and I've searched the whole BAWE corpus:

From this screenshot, we can see that BAWE contains 15,718 instances of 'we' (or 1,885 per million words). A similar search for 'I' reveals that there are 13,069 instances in the whole student corpus (or 1,568 per million words).

So in the BAWE corpus, 'we' is more frequent than 'I'; this is the opposite result to Googlefight. Searching a corpus of student writing gives us results from this type of text and not from all texts found on the web.

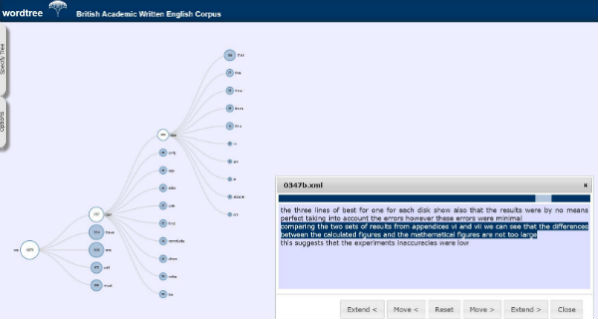

A concordancer (unlike Googlefight) also shows us the co-text, that is, the words appearing before and after our search term (in this case 'we'). Another piece of software that shows us the co-text to 'I' and 'we' is the 'Wordtree'. Below you can see a search for words occurring after 'we'. You can access the Wordtree online .

So, is 'we' or 'I' more common in essay-writing? The answer overall from our search of the BAWE corpus is that 'we' is more common. But to give a more useful and accurate answer, you might want to also look at particular disciplines such as English Literature or Biological Sciences.

And you might also want to consider whether you're writing an 'essay' or a 'literature review' or a 'lab report'.

But in overall student writing 'we' takes first place!

Follow-on links

Using sketch engine to explore the bawe corpus.

The free version of Sketch Engine gives access to several corpora, including BAWE. From the homepage of Sketch Engine, choose a corpus, then click ‘concordance’ and type a word or phrase in the text box. This will produce a list of concordance lines which can then be sorted. The ‘help’ function gives very clear guidance for more advanced searches.

Reading more about BAWE

You can find out more about the British Academic Written English corpus (BAWE) from the BAWE website .

Corpus linguistics resources

For useful links, look at this site . Click on ‘CBL Links’ for information on corpora, software and courses.

You could also look for free, short courses on Futurelearn, such as The University of Lancaster's Corpus Linguistics

And from The Open University...

- You might like The Open University course Exploring English Grammar

- Try a free sample of English Grammar In Context on OpenLearn

- If you're a bit more advanced, consider the postgraduate course Language, literacy and learning in the contemporary world - there's an OpenLearn course sample on learning a second language

Become an OU student

Ratings & comments, share this free course, copyright information, publication details.

- Originally published: Monday, 20 January 2014

- Body text - Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 : The Open University

- Image 'Should this be I or should this be we?' - Emanuele Rosso under CC-BY-NC-ND licence under Creative-Commons license

- Image 'A screengrab comparing the number of returns for I against We on Google' - Copyright: Googlefight

- Image 'Screengrab showing instances of the word 'we' in the British Academic Written English corpus as returned by SketchEngine' - Copyright: Sketchengine

- Image 'A screengrab from Wordtree showing the words which follow we' - Copyright: Wordtree

Rate and Review

Rate this article, review this article.

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

For further information, take a look at our frequently asked questions which may give you the support you need.

We should use ‘I’ more in academic writing – there is benefit to first-person perspective

Lecturer in Critical Thinking; Curriculum Director, UQ Critical Thinking Project, The University of Queensland

Disclosure statement

Peter Ellerton is affiliated with the Centre for Critical and Creative Thinking. He is a Fellow of the Rationalist Society of Australia.

University of Queensland provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

The use of the word “I” in academic writing, that is writing in the first person , has a troublesome history. Some say it makes writing too subjective, others that it’s essential for accuracy.

This is reflected in how students, particularly in secondary schools, are trained to write. Teachers I work with are often surprised that I advocate, at times, invoking the first person in essays or other assessment in their subject areas.

In academic writing the role of the author is to explain their argument dispassionately and objectively. The author’s personal opinion in such endeavours is neither here nor there.

As noted in Strunk and White’s highly influential Elements of Style – (first published in 1959) the writer is encouraged to place themselves in the background.

Write in a way that draws the reader’s attention to the sense and substance of the writing, rather than to the mood and temper of the author.

This all seems very reasonable and scholarly. The move towards including the first person perspective, however, is becoming more acceptable in academia.

There are times when invoking the first person is more meaningful and even rigorous than not. I will give three categories in which first person academic writing is more effective than using the third person.

1. Where an academic is offering their personal view or argument

Above, I could have said “there are three categories” rather than “I will give three categories”. The former makes a claim of discovering some objective fact. The latter, a more intellectually honest and accountable approach, is me offering my interpretation.

I could also say “three categories are apparent”, but that is ignoring the fact it is apparent to me . It would be an attempt to grant too much objectivity to a position than it deserves.

In a similar vein, statements such as “it can be argued” or “it was decided”, using the passive voice, avoid responsibility. It is much better to say “I will argue that” or “we decided that” and then go on to prosecute the argument or justify the decision.

Taking responsibility for our stances and reasoning is important culturally as well as academically. In a participatory democracy, we are expected to be accountable for our ideas and choices. It is also a stand against the kinds of anonymous assertions that easily proliferate via fake and unnamed social media accounts.

Read more: Post-truth politics and why the antidote isn't simply 'fact-checking' and truth

It’s worth noting that Nature – arguably one of the world’s best science journals – prefers authors to selectively avoid the passive voice. Its writing guidelines note:

Nature journals prefer authors to write in the active voice (“we performed the experiment…”) as experience has shown that readers find concepts and results to be conveyed more clearly if written directly.

2. Where the author’s perspective is part of the analysis

Some disciplines, such as anthropology , recognise that who is doing the research and why they are doing it ought to be overtly present in their presentation of it.

Removing the author’s presence can allow important cultural or other perspectives held by the author to remain unexamined. This can lead to the so-called crisis of representation , in which the interpretation of texts and other cultural artefacts is removed from any interpretive stance of the author.

This gives a false impression of objectivity. As the philosopher Thomas Nagel notes, there is no “ view from nowhere ”.

Philosophy commonly invokes the first person position, too. Rene Descartes famously inferred “I think therefore I am” ( cogito ergo sum ). But his use of the first person in Meditations on First Philosophy was not simply an account of his own introspection. It was also an invitation to the reader to think for themselves.

3. Where the author wants to show their reasoning

The third case is especially interesting in education.

I tell students of science, critical thinking and philosophy that a phrase guaranteed to raise my hackles is “I strongly believe …”. In terms of being rationally persuasive, this is not relevant unless they then go on tell me why they believe it. I want to know what and how they are thinking.

To make their thinking most clearly an object of my study, I need them to make themselves the subjects of their writing.

I prefer students to write something like “I am not convinced by Dawson’s argument because…” rather than “Dawson’s argument is opposed by DeVries, who says …”. I want to understand their thinking not just use the argument of DeVries.

Read more: Thinking about thinking helps kids learn. How can we teach critical thinking?

Of course I would hope they do engage with DeVries, but then I’d want them to say which argument they find more convincing and what their own reasons were for being convinced.

Just stating Devries’ objection is good analysis, but we also need students to evaluate and justify, and it is here that the first person position is most useful.

It is not always accurate to say a piece is written in the first or third person. There are reasons to invoke the first person position at times and reasons not to. An essay in which it is used once should not mean we think of the whole essay as from the first person perspective.

We need to be more nuanced about how we approach this issue and appreciate when authors should “place themselves in the background” and when their voice matters.

- Critical thinking

- First person

- Academic writing

- Essay writing

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Data and Reporting Analyst

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

10 Better Ways To Say “Our” And “We” In Formal Essays

When writing formal essays, there are rules of English grammar that we need to follow. Sometimes, we need to change perspective, and instead of writing in the first person and saying ‘we,’ we need to stay in the third person. So, what are the best alternatives to saying ‘we?’

There are many alternatives to saying ‘we.’ The most preferred alternatives we use are ‘they,’ ‘the group,’ and ‘the team.’ These three alternatives are the more general alternatives that seem to be applicable in almost all contexts, especially ‘they’ as we simply remove ourselves from the narrative by using it.

‘They’ is the most general and preferred alternative to ‘we’ and ‘us.’ By using ‘they,’ we replace our first-person pronoun with a third-person pronoun that simply excludes ourselves from the narrative, making the essay sound more objective and formal. ‘They’ is also a pronoun that is applicable in all contexts.

Take a look at these examples below.

- Original: Humans are incredible creatures. We have so much creativity.

- Alternative: Humans are incredible creatures. They have so much creativity.

- Original: Our group will report tomorrow. We will talk about this month’s sales.

- Alternative: Their group will report tomorrow. They will talk about this month’s sales.

- Original: We simply hope the audience learned something from us.

- Alternative: They simply hope the audience learned something from them.

- Original: We’ve done our research, but we don’t have precise predictions yet.

- Alternative: They’ve done their research, but they don’t have precise predictions yet.

‘The group’ is a good, general alternative to saying ‘we’ in formal essays. However, this alternative specifies that we refer to ‘we’ as a group of individuals. Therefore, this alternative does not apply to populations of large scale like nations, humans, or races.

- Original: We were able to conclude the following findings.

- Alternative: The group was able to conclude the following findings.

- Original: We could not administer the test today due to certain circumstances.

- Alternative: The group could not administer the test today due to certain circumstances?

- Original: Our experimental set-ups did not yield any significant difference.

- Alternative: The group’s experimental set-ups did not yield any significant difference.

- Original: It is beneficial for us if more people participate in the study.

- Alternative: It is beneficial for the group if more people participate in the study.

‘The team’ is synonymous with ‘the group.’ It is another alternative to saying ‘we’ but implies that ‘we’ refers to a team or a group of individuals that are together for the same purpose. However, ‘the team’ does not apply to bigger populations, like an entire race or human population.

- Original: We are composed of individuals with a passion for learning.

- Alternative: The team is composed of individuals with a passion for learning.

- Original: The results of our work do not define our identity.

- Alternative: The results of the team’s work do not define the team’s identity.

- Original: We poured our best efforts into this project.

- Alternative: The team poured their best efforts into this project.

- Original: We do not tolerate any misconduct and violent behavior.

- Alternative: The team does not tolerate any misconduct and violent behavior.

‘The body’ is another alternative for saying ‘we’ in formal essays. We mostly use ‘body’ when referring to large groups of individuals like the audience, spectators, or students. However, we do not use it for extreme scales such as a race population, and the like.

- Original: We didn’t find the presentation interesting.

- Alternative: The body didn’t find the presentation interesting.

- Original: We have a lot of questions we want to ask the speaker after the talk.

- Alternative: The body has a lot of questions they want to ask the speaker after the talk.

- Original: We listened to different opinions on the issue.

- Alternative: The body listened to different opinions on the issue.

- Original: We were only able to watch the latter part of the program.

- Alternative: The body was only able to watch the latter part of the program.

The Organization

‘The organization’ is a more specific alternative for ‘we.’ In using this alternative, we refer to ‘we’ as an organization in the context we are talking or writing. This alternative is most applicable for organization-related things. However, do not use this alternative if the context does not involve an organization.

- Original: We will push through with the planned fundraising project.

- Alternative: The organization will push through with the planned fundraising project.

- Original: Our accomplishments this year are something we should be proud of.

- Alternative: The organization’s accomplishments this year are something they should be proud of.

- Original: We plan on collaborating with other organizations to plan the event.

- Alternative: The organization plans on collaborating with other organizations to plan the event.

- Original: We only accept people who have a passion for our advocacy.

- Alternative: The organization only accepts people who have a passion for their advocacy.

The Researchers

‘The researchers’ is a specific alternative to ‘we’ that we only use when we refer to ‘we’ as a group of researchers. We mostly use this alternative in writing research papers that need to be in the third-person perspective. However, we don’t use this alternative outside the scope of research.

- Original: We administered a total of three set-ups for the study.

- Alternative: The researchers administered a total of three set-ups for the study.

- Original: We encountered circumstances that provided the limitations of our research.

- Alternative: The researchers encountered circumstances that provided the limitations of their research.

- Original: After three months of observation, our conclusion is as follows .

- Alternative: After three months of observation, the researchers’ conclusion is as follows.

- Original: Our study would not be successful if not for the help of our research adviser.

- Alternative: The researchers’ study would not be successful if not for the help of their research adviser.

The Company

‘The company’ is another specific alternative for ‘we.’ We only use this alternative, if we are in the context that ‘we’ refers to a company. We use this mostly in business-related reports or presentations. Other than that, we don’t use this alternative for purposes that do not involve a company.

- Original: Our sales for this month are higher than last month.

- Alternative: The company’s sales for this month are higher than last month.

- Original: We only sell organic, vegan-friendly, and cruelty-free products.

- Alternative: The company only sells organic, vegan-friendly, and cruelty-free products.

- Original: We need to continuously track our demand and supply levels.

- Alternative: The company needs to continuously track its demand and supply levels.

- Original: Our vision and mission should guide us in all our endeavors.

- Alternative: The company’s vision and mission should guide the company in all its endeavors.

The Association

‘The association’ is also a specific alternative to ‘we.’ We only use this alternative if we are in a context to talk as part of or within an association. However, we do not use this alternative if we are not talking about, for, or as part of an association.

- Original: We will hold meetings every Friday to discuss weekly matters.

- Alternative: The association will hold meetings every Friday to discuss weekly matters.

- Original: Our job is to advocate and uphold democracy in our country.

- Alternative: The association’s job is to advocate and uphold democracy in our country.

- Original: Our goal directs the objectives of every endeavor we take care of.

- Alternative: The association’s goal directs the objectives of every endeavor it takes care of.

- Original: We are open to expanding the scope of its initiatives.

- Alternative: The association is open to expanding the scope of its initiatives.

‘Humans’ is a specific alternative for ‘we’ that we use only when we refer to ‘we’ as the entire human population. We cannot use ‘humans’ for small-scale groups like researchers or a company. We use this alternative only when we regard ‘we’ as the entire human population.

Take a look at the examples below.

- Original: We have so much potential inside us.

- Alternative: Humans have so much potential inside them.

- Original: Sometimes, even 24 hours isn’t enough for what we want to do in a day.

- Alternative: Sometimes, even 24 hours isn’t enough for what humans want to do in a day.

- Original: All of us have a desire to accomplish something in our lives.

- Alternative: All humans have a desire to accomplish something in their lives.

- Original: We cannot live without one another.

- Alternative: Humans cannot live without one another.

‘Society’ or ‘the society’ is an alternative to ‘we’ that we use when referring to ‘we’ as the society we are part of, or we are in. Like ‘humans,’ we do not use ‘society’ for small-scale groups, and we can only use this alternative for anything that involves our society.

- Original: We are so cruel towards others sometimes.

- Alternative: Society is so cruel towards others sometimes.

- Original: We have reached far and accomplished a lot collectively.

- Alternative: Society has reached far and accomplished a lot collectively.

- Original: Sometimes, we put up unrealistic standards for ourselves and for others.

- Alternative: Sometimes, society puts up unrealistic standards for oneself and for others.

- Original: We should start accepting everyone for who they are.

- Alternative: Society should start accepting everyone for who they are.

Is It Appropriate To Use ‘Our’ And ‘We’ In Formal Essays?

Whether to use ‘we’ or not depends on how formal you want your essay to be or how formal it needs to be. Some formal essays allow the use of first-person pronouns like ‘we’ and ‘us.’ However, omitting these pronouns do make your essays sound more professional, formal, and objective.

Martin holds a Master’s degree in Finance and International Business. He has six years of experience in professional communication with clients, executives, and colleagues. Furthermore, he has teaching experience from Aarhus University. Martin has been featured as an expert in communication and teaching on Forbes and Shopify. Read more about Martin here .

- Research On or In – Which Is Correct?

- What Are Power Dynamics? (Meaning & Examples)

- 10 Words For Working Together Towards A Common Goal

- Work On/In/With A Team – Preposition Guide (With Examples)

- Support LUC

- Directories

- KRONOS Timecard

- Employee Self-Service

- Password Self-service

- Academic Affairs

- Advancement

- Admission: Adult B.A.

- Admission: Grad/Prof

- Admission: International

- Admission: Undergrad

- Alumni Email

- Alumni Relations

- Arrupe College

- Bursar's Office

- Campus Ministry

- Career Centers

- Center for Student Assistance and Advocacy

- Colleges and Schools

- Commencement

- Conference Services

- Continuing Education

- Course Evaluations IDEA

- Cuneo Mansion & Gardens

- Dining Services

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Emeriti Faculty Caucus

- Enterprise Learning Hub

- Executive and Professional Education

- Faculty Activity System

- Financial Aid

- Human Resources

- IBHE Institutional Complaint System

- Information Technology Services

- Institute of Environmental Sustainability

- Learning Portfolio

- Loyola Health App

- Loyola University Chicago Retiree Association (LUCRA)

- Madonna della Strada Chapel

- Media Relations

- Navigate Staff

- Office of First Year Experience

- Office of Institutional Effectiveness

- President's Office

- Rambler Buzz

- Registration and Records

- Residence Life

- Retreat & Ecology Campus

- Rome Center

- Security/Police

- Staff Council

- Student Achievement

- Student Consumer Information

- Student Development

- Study Abroad

- Summer Sessions

- University Policies

Writing Center

Loyola university chicago, using "i" in an essay.

A common issue in essay-writing is whether to use “I”:

(E.g., “I believe that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. used the rhetorical appeal of pathos to both admonish and make allies of white fellow clergymen who were not yet supporting civil rights for African Americans.”)

Some teachers will allow you to use “I” while others will not. Be sure to ask.

Try to avoid using first person verb tense unless you are writing a Personal or Response Essay describing events that happened directly to you and are informed by your unique perspective.

At the same time, remember that you are the Assumed Author. When you are not quoting, summarizing, or explaining the meaning of outside material, your reader will read the essay as your personal perspective.

With this in mind, you can correct the habit of self-attribution—writing “I think/I believe/I am of the opinion that...”—by erasing yourself from the offending passages:

Example 1 : “ I believe that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. used the rhetorical appeal of pathos to both admonish and make allies of white fellow clergymen who were not yet supporting civil rights for African Americans.”

Example 2 : “ In my opinion, King Jr’s expressed respect for white clergymen as men of the cloth made it possible for them to become allies for African Americans, even as he chided them for their callous indifference to racial injustice.”

Since you are understood to be the author, state your opinion as a point-of-fact; you will go on to prove your statements in your paper, so be confident in your assertions.

- Undergraduate

- Graduate/ Professional

- Adult Education

How To Avoid Using “We,” “You,” And “I” In An Essay

Formal writing requires following patterns, sometimes uncommon for the everyday communication or fiction literature style. When composing an academic paper, one wants to rely on facts, check plagiarism , cite the sources, and sound objective and neutral. It is best to avoid personal opinions in essays to achieve the latter, making the work more generalized and persuasive. How can one omit first and second person pronouns so the text still sounds natural?

What are first and second-person pronouns

First-person pronouns I, we, me, us, my, mine, our, and ours present the story from the narrator’s perspective.

I chose the research topic because it sounded relevant to my favorite subject.

We conducted an experiment to confirm or disprove our theory.

Second-person pronouns, you and your, are used to address the reader.

This article will teach you how to avoid second-person pronouns in your writing.

Why first and second-person pronouns are not recommended for academic writing

“I,” “we,” “you,” and similar pronouns shift the perspective from the subject itself to the individual, emphasizing the author of the paper or the action described in the text. It is appropriate for fiction or everyday speech but doesn’t suit academic papers, where the focus should be on the research topic. Moreover, a personal point of view makes the information sound subjective and less trustworthy, while academic writing aims to make the opposite impression. Hence, one should choose the wording carefully and omit using a first-person perspective in formal texts.

Ways to replace first and second-person pronouns in formal paper

Here are some strategies to make the paper sound more formal and professional.

Focus on the writing

Shift the perspective from the narrator to the work.

I discovered that… – The research states that…

We believe that… – The experiments confirm that…

Address the facts

Instead of framing the information with personal opinion, double-check the facts and let them speak for themselves.

I chose the topic as I believe the polar bear extinction is a burning issue… – Global polar bear numbers are projected to decline by 30% by 2050.

You can also refer to the authoritative source: According to the World Wild Fund prognosis, the global polar bear numbers are projected to decline by 30% by 2050.

Change into passive voice

In fiction, marketing, and personal communication, the active voice sounds more energetic and expressive, while the neutrality of the passive voice suits formal writing.

I conducted a survey in 2023… – The survey was conducted in 2023…

We surveyed 1000 respondents and got the statistics… – From 1000 respondents surveyed in 2023, …

Specify the source and the audience

Be specific and name the objects or people instead of using pronouns.

From the article, you will learn how… – The article tells the reader how…/The article describes how…

We describe the process in the paper published in 2018. – The paper published in 2018 gives the details on…/Dr. Jackson and Dr. Mark refer to the fact in the paper published in 2018…

PlagiarismCheck.org is your one-stop resource for all matters related to academic writing! Try our plagiarism and Chat GPT detector , stay mistakes-free, and get more professional writing tips in our blog. Join us now!

Discover how PlagiarismCheck.org can empower your workflow!

Related articles.

Academic Cheating Statistics Teachers Need to Know

7 Neologisms Invented by Famous Writers

Martin Luther King Plagiarism Case

Improvements to Paper Checking: Fresh Updates Educators Will Love

Paraphrase: Write in Your Own Words

The document is loaded and is now being checked for plagiarism.

Go to profile

To continue, please provide your email adress. Already have an account? Please use Sign In

Use of this website establishes your agreement to our Terms & Privacy Policy , and to receiving product-related emails, which you can unsubscribe from at any time.

Not a member? Create Account

Email Address

Reset password

To continue, please enter your email

Choose a new password

New password

Confirm new password

We'll be glad to know what you like or dislike about our website. Let us know about your suggestions concerning service enhancement, or any technical difficulties you are experiencing.

Your message

Continue to check the text

Are you a professor, teacher, instructor, or tutor in the education sector? Your thoughts are highly welcome!

Click here or email [email protected] to say what you think on the topic. Make sure your subject line is "Unobvious plagiarism consequences."

Please, include:

- your 50-100 words long answer

- your full name, short bio, country and personal blog or website

If your response adds value, we will add it to this original post.

Shopping cart

One step to the finish, find out more about our products and solutions.

- For teachers

- How it works

- AI Plagiarism Checker

- AI Content Detector with API integration

- User guides

- Customer reviews

- API documentation

- Canvas integration

- Moodle integration

- Google classroom integration

- Google docs add-on

- [email protected]

- +1 844 319 5147 (24/7)

- Plagiarism check free

- Best similarity checking app

- Plagiarism detector for canvas

- Plagiarism checking tool for moodle

- Plagiarism detector for google classroom

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Refund policy

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write an argumentative essay | Examples & tips

How to Write an Argumentative Essay | Examples & Tips

Published on July 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

An argumentative essay expresses an extended argument for a particular thesis statement . The author takes a clearly defined stance on their subject and builds up an evidence-based case for it.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

When do you write an argumentative essay, approaches to argumentative essays, introducing your argument, the body: developing your argument, concluding your argument, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about argumentative essays.

You might be assigned an argumentative essay as a writing exercise in high school or in a composition class. The prompt will often ask you to argue for one of two positions, and may include terms like “argue” or “argument.” It will frequently take the form of a question.

The prompt may also be more open-ended in terms of the possible arguments you could make.

Argumentative writing at college level

At university, the vast majority of essays or papers you write will involve some form of argumentation. For example, both rhetorical analysis and literary analysis essays involve making arguments about texts.

In this context, you won’t necessarily be told to write an argumentative essay—but making an evidence-based argument is an essential goal of most academic writing, and this should be your default approach unless you’re told otherwise.

Examples of argumentative essay prompts

At a university level, all the prompts below imply an argumentative essay as the appropriate response.

Your research should lead you to develop a specific position on the topic. The essay then argues for that position and aims to convince the reader by presenting your evidence, evaluation and analysis.

- Don’t just list all the effects you can think of.

- Do develop a focused argument about the overall effect and why it matters, backed up by evidence from sources.

- Don’t just provide a selection of data on the measures’ effectiveness.

- Do build up your own argument about which kinds of measures have been most or least effective, and why.

- Don’t just analyze a random selection of doppelgänger characters.

- Do form an argument about specific texts, comparing and contrasting how they express their thematic concerns through doppelgänger characters.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

An argumentative essay should be objective in its approach; your arguments should rely on logic and evidence, not on exaggeration or appeals to emotion.

There are many possible approaches to argumentative essays, but there are two common models that can help you start outlining your arguments: The Toulmin model and the Rogerian model.

Toulmin arguments

The Toulmin model consists of four steps, which may be repeated as many times as necessary for the argument:

- Make a claim

- Provide the grounds (evidence) for the claim

- Explain the warrant (how the grounds support the claim)

- Discuss possible rebuttals to the claim, identifying the limits of the argument and showing that you have considered alternative perspectives

The Toulmin model is a common approach in academic essays. You don’t have to use these specific terms (grounds, warrants, rebuttals), but establishing a clear connection between your claims and the evidence supporting them is crucial in an argumentative essay.

Say you’re making an argument about the effectiveness of workplace anti-discrimination measures. You might:

- Claim that unconscious bias training does not have the desired results, and resources would be better spent on other approaches

- Cite data to support your claim

- Explain how the data indicates that the method is ineffective

- Anticipate objections to your claim based on other data, indicating whether these objections are valid, and if not, why not.

Rogerian arguments

The Rogerian model also consists of four steps you might repeat throughout your essay:

- Discuss what the opposing position gets right and why people might hold this position

- Highlight the problems with this position

- Present your own position , showing how it addresses these problems

- Suggest a possible compromise —what elements of your position would proponents of the opposing position benefit from adopting?

This model builds up a clear picture of both sides of an argument and seeks a compromise. It is particularly useful when people tend to disagree strongly on the issue discussed, allowing you to approach opposing arguments in good faith.

Say you want to argue that the internet has had a positive impact on education. You might:

- Acknowledge that students rely too much on websites like Wikipedia

- Argue that teachers view Wikipedia as more unreliable than it really is

- Suggest that Wikipedia’s system of citations can actually teach students about referencing

- Suggest critical engagement with Wikipedia as a possible assignment for teachers who are skeptical of its usefulness.

You don’t necessarily have to pick one of these models—you may even use elements of both in different parts of your essay—but it’s worth considering them if you struggle to structure your arguments.

Regardless of which approach you take, your essay should always be structured using an introduction , a body , and a conclusion .

Like other academic essays, an argumentative essay begins with an introduction . The introduction serves to capture the reader’s interest, provide background information, present your thesis statement , and (in longer essays) to summarize the structure of the body.

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how a typical introduction works.

The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education. The use of the internet in academic contexts is on the rise, and its role in learning is hotly debated. For many teachers who did not grow up with this technology, its effects seem alarming and potentially harmful. This concern, while understandable, is misguided. The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its critical benefits for students and educators—as a uniquely comprehensive and accessible information source; a means of exposure to and engagement with different perspectives; and a highly flexible learning environment.

The body of an argumentative essay is where you develop your arguments in detail. Here you’ll present evidence, analysis, and reasoning to convince the reader that your thesis statement is true.

In the standard five-paragraph format for short essays, the body takes up three of your five paragraphs. In longer essays, it will be more paragraphs, and might be divided into sections with headings.

Each paragraph covers its own topic, introduced with a topic sentence . Each of these topics must contribute to your overall argument; don’t include irrelevant information.

This example paragraph takes a Rogerian approach: It first acknowledges the merits of the opposing position and then highlights problems with that position.

Hover over different parts of the example to see how a body paragraph is constructed.

A common frustration for teachers is students’ use of Wikipedia as a source in their writing. Its prevalence among students is not exaggerated; a survey found that the vast majority of the students surveyed used Wikipedia (Head & Eisenberg, 2010). An article in The Guardian stresses a common objection to its use: “a reliance on Wikipedia can discourage students from engaging with genuine academic writing” (Coomer, 2013). Teachers are clearly not mistaken in viewing Wikipedia usage as ubiquitous among their students; but the claim that it discourages engagement with academic sources requires further investigation. This point is treated as self-evident by many teachers, but Wikipedia itself explicitly encourages students to look into other sources. Its articles often provide references to academic publications and include warning notes where citations are missing; the site’s own guidelines for research make clear that it should be used as a starting point, emphasizing that users should always “read the references and check whether they really do support what the article says” (“Wikipedia:Researching with Wikipedia,” 2020). Indeed, for many students, Wikipedia is their first encounter with the concepts of citation and referencing. The use of Wikipedia therefore has a positive side that merits deeper consideration than it often receives.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

An argumentative essay ends with a conclusion that summarizes and reflects on the arguments made in the body.

No new arguments or evidence appear here, but in longer essays you may discuss the strengths and weaknesses of your argument and suggest topics for future research. In all conclusions, you should stress the relevance and importance of your argument.

Hover over the following example to see the typical elements of a conclusion.

The internet has had a major positive impact on the world of education; occasional pitfalls aside, its value is evident in numerous applications. The future of teaching lies in the possibilities the internet opens up for communication, research, and interactivity. As the popularity of distance learning shows, students value the flexibility and accessibility offered by digital education, and educators should fully embrace these advantages. The internet’s dangers, real and imaginary, have been documented exhaustively by skeptics, but the internet is here to stay; it is time to focus seriously on its potential for good.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

An argumentative essay tends to be a longer essay involving independent research, and aims to make an original argument about a topic. Its thesis statement makes a contentious claim that must be supported in an objective, evidence-based way.

An expository essay also aims to be objective, but it doesn’t have to make an original argument. Rather, it aims to explain something (e.g., a process or idea) in a clear, concise way. Expository essays are often shorter assignments and rely less on research.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

The majority of the essays written at university are some sort of argumentative essay . Unless otherwise specified, you can assume that the goal of any essay you’re asked to write is argumentative: To convince the reader of your position using evidence and reasoning.

In composition classes you might be given assignments that specifically test your ability to write an argumentative essay. Look out for prompts including instructions like “argue,” “assess,” or “discuss” to see if this is the goal.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write an Argumentative Essay | Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved April 6, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/argumentative-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, how to write an expository essay, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

THE PHILOSOPHER