A Summary and Analysis of the Book of Ruth

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

The Book of Ruth is one of the shorter books of the Bible, but the story it tells is one of the most movingly ‘human’ in all of the Old Testament. However, how the story of Ruth should be interpreted is not an easy question to answer. Let’s delve deeper into the Biblical Book of Ruth to discover a world of outsiders, love, law, and mysterious customs involving shoes.

Before we come to the analysis, though, it might be worth summarising the plot of the story of Ruth as it’s laid out in the Bible. The Book of Ruth is thought to have been written some time between 450 and 250 BC.

Book of Ruth: summary

A man named Elimelech, from Bethlehem-Judah, left his hometown when a famine struck. He and his wife Naomi, along with their two sons Mahlon and Chilion, left for Moab. Elimelech died, leaving Naomi with her two sons.

These two sons married Moabite women: Orpah and Ruth. Ten years passed, and Mahlon and Chilion both died. Naomi decided to return to Judah, hearing that the famine had passed, but she entreated her sisters-in-law to remain in their homeland of Moab. After all, this was their home, and why should they accompany her back to her homeland now their husbands were dead? They have a house in Moab and will be provided for.

Although both women initially pledged to stay with Naomi, when she urged them to leave her, Orpah agreed. But Ruth stayed by Naomi’s side and vowed to accompany her back to Judah.

Back in Judah, there was wealthy relative of Naomi’s dead husband, a man named Boaz. Ruth went into the field to gather corn for the harvest, where she caught the eye of Boaz.

Boaz promised to treat Ruth, an outsider in the land of Judah, as an equal, and welcomed her. Ruth was overcome by his kindness, and asked what she, a stranger, had done to deserve it. Boaz replied that he had heard how she left behind her own parents in Moab to accompany her mother-in-law into a strange land.

Ruth went home to her mother-in-law that evening, and told her what had happened. Naomi told Ruth that Boaz was a near-kinsman, and as such he will protect and provide for them. Ruth went to Boaz that night and knelt at his feet. She told him she was his handmaid and they were kin.

Boaz replied that there was a man who was an even closer kinsman to her than he was, and this other man had, essentially, first refusal on whether he wished to marry Ruth. However, if this other man said he didn’t want to marry Ruth, Boaz declared he would happily do so. And he gave her six measures of corn to take back to Naomi as pledge.

Boaz called a counsel of elders, including this other kinsman of Ruth’s, and explained that Naomi had her dead husband’s parcel of land to sell, but that if the kinsman wished to claim it, he must also agree to marry Ruth.

There followed a strange custom involving a shoe, whereby a man ‘plucked off his shoe’ and handed it to his neighbour if he wished to forgo his claim to something. This was a kind of ‘testimony in Israel’ in those days, we are told, a legal ritual which sealed the deal.

So this other man took off his shoe and gave it to Boaz, signalling that he relinquished all claim to Ruth or her dead father-in-law’s land. Marrying Ruth would damage his own inheritance from his father (presumably for marrying a Moabite foreigner) so he declined. Boaz announced that he would marry Ruth, and they promptly got married, and Ruth had a son.

This son, we are told, in turn had a son named Jesse, who himself had a son, named David.

Book of Ruth: analysis

Many books of the Old Testament seem to have been written to counter the narrow nationalism of other books of the Old Testament. So the message of the Book of Jonah – in which the title character’s disdain for the people of Nineveh receives a sharp moral rebuke from God – functions as a sort of riposte to the Book of Obadiah. And we can analyse the Book of Ruth as a response, or counter-response, to those other stories in the Bible which endorse a nationalistic understanding of Israel.

Whichever interpretation of Ruth we choose to follow, we should bear in mind the key fact of the story, which is that Ruth is a Moabite who leaves her family and her own people behind to begin a new life, as the devoted companion to her widowed mother-in-law Naomi, in the land of Judah.

The Dictionary of the Bible emphasises this aspect of the story, and suggests that Ruth’s loyalty to her adopted nation of Judah is important because Ruth is the ancestor of David, the great King of Israel. (Ruth is David’s great-grandmother.) So one ‘meaning’ for the Book of Ruth, and its significance for Judaism and Christianity, lies in its genealogical quality, in providing the story of David’s ancestry. If Ruth had never left Moab and followed Naomi to Judah, David would never have been born.

All of our lives hinge on such chance happenings or vagaries that occurred somewhere in our ancestral history, but for Jews and Christians the story of Ruth’s adoption of Judah as her new home, and her union with Boaz, possesses greater importance because her descendants would include King David of Israel.

Ruth is an idyllic romance, and one of only two books of the Bible named after women (the other one is Esther). But it would be wrong to offer a feminist interpretation of the story of Ruth which saw her as somehow bucking the patriarchal customs and laws of her time.

After all, the patriarchal laws binding women to men are still present her: Ruth may wish to marry Boaz, but he is intent on observing the law which gives Ruth’s closer kinsman first dibs on her, as it were. Both Ruth and Naomi are survivors in this patriarchal landscape, but they are nevertheless constrained by its laws and traditions.

We should view the Book of Ruth firmly as fiction: it’s a ‘short story’, essentially, some two millennia before the ‘short story’ came into existence as a recognised genre. But the details of the narrative are too neat to be strictly historical.

For instance, the names of Elimelech’s children, Mahlon and Chilion, literally mean ‘sickness’ and ‘wasting’ respectively; these strike us as unlikely names for a parent to give to their children, and given the fates of the two sons, their names seem far too pat. They chime symbolically, however, with the famine which drives Elimelech to leave Judah behind for Moab.

Continue to explore the Bible with our summary and analysis of the Book of Esther .

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from interesting literature.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

News and Interpretations on the Bible and Ancient Near East History.

Mark Elliott

- Excavations

- Archaeology

- Biblical Interpretation

- Dead Sea Scrolls

- Historical Jesus

- New Testament

- Old Testament

- Second Temple Judaism

- Science and Religion

- Hebrew Language

- Archeological Reports

The Book of Ruth: Origin and Purpose

As a last option for understanding Ruth, I would offer that Ruth does fit well when set against the background of the early post-exilic period. The literature on this time is vast and continues to grow, but it is safe to say that the small community in Judea in the late 500s to early 400s B.C.E. conflicted over various societal issues, one of which was how they should define the boundaries of their community. The prophet Zechariah believed that Jerusalem would throng with foreigners who would count as Yhwh’s people (Zech 2:15[EV 11]), but other persons from the Ezra-Nehemiah narrative feel that foreigners have no part in the community (Ezra 4:1-3; 9:1-4; Neh 13:1-3). This is not to say that Ruth reacts directly to the Ezra-Nehemiah text, nor should we read Ezra-Nehemiah uncritically as plain history, but it is reasonable to hold that community cohesion and in-group/out-group questions were live topics at the time. Within this debate, we can see how Ruth provides a counterfactual to a certain exclusivist perspective toward outsiders. The text is not so bold as to claim that all non-Israelites/Judeans should count as people of Yhwh, but it does demonstrate that there are cases where a foreigner can reasonably measure up to the standard of a true Israelite.

See Also: Reading Ruth in the Restoration Period (Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2016).

By E. Allen Jones III, PhD Associate Professor of Bible Corban University November 2017

If we were to inquire into the origin and purpose of the biblical book of Ruth, it may seem like a simple and straightforward question. As modern readers in highly literate communities, we are accustomed to asking “why” – why did an author write this book? To whom were they speaking and what were they trying to communicate? Modern authors follow established practices – they include their names with their publications. They identify the year in which they produced a work. They will even include prefaces and/or introductions that help orient readers to their thoughts. Understandably, we suppose such information should be equally as important to and equally accessible for the books that we find in the Bible. Sadly (or happily, depending on one’s interpretive sensibilities), such information is not generally on hand for biblical books. The biblical texts, at least those found in the Hebrew Bible (HB)/Old Testament (OT), are technically anonymous. Traditions do come to be associated with various figures (Neh 8:1; Mark 12:26), but biblical books do not include title pages that identify an author(s) or date of publication. Yet, despite the fact that such information is illusive when it comes to biblical texts, the intuition remains among laypeople and scholars alike that it is likely relevant to how we understand the HB/OT. So it is for the HB/OT broadly, and so it is for the book of Ruth. Fortunately for the reader of this short essay, we will restrict our investigation herein to an exploration of the various scholarly arguments on the origin and purpose of Ruth. Thus, certainty may evade us, but time travel back into the ancient world of Israel will not be necessary.

Framing the Problem [1]

When it comes to specifying either a possible publication range and/or articulating a purpose for Ruth, biblical scholars traverse all areas of the proverbial map. On the matter of dating, our oldest manuscripts for Ruth come from the 1st cent. B.C.E. (Campbell, 1975), but the story tells of events that are set in the Judges period (pre-1000 B.C.E.), which allows for a much earlier point of origin. Two clues from within the story – mention of (King) David and the “sandal ceremony” (Ruth 4:6-8) – suggest that our author was somewhat removed from the events of the story, but it is hard to say by how far. Thus, we have a window of some 800-900 years during which the story could appear, and scholars have made full use of the possibilities. Murray Gow (1992) represents one end of the spectrum, setting the book right near the beginning of the monarchic period. Erich Zenger (1992) holds down the other pole in the spectrum, claiming that Ruth comes from the Maccabean period (i.e. after the expulsion of the Greek occupiers in Israel and before Rome’s domination of Palestine). Considering the purpose of the book, again, scholars vary widely. Some refer to the story as an idyllische Novelle (Kaiser, 1969). Others hold that it is a political apology for David’s lineage (Gow, 1992), and still others see it as a subversive cultural commentary (Fewell and Gunn, 1990). Though Ruth has been with us for anywhere between 2,000-3,000 years, it is clear that space remains to discuss how we should view the book.

Framing the Solutions

Taking into account the difficulties outlined above, there are broadly two stances that scholars have taken regarding Ruth’s origin and purpose. On the one hand, some opt not to pursue a date of origin, which, in turn, means they may also pass over considering what the book’s original purpose was. This approach can stem from a post-modern reading strategy (Greenstein, 1999) or from an ecclesial commitment to the ongoing witness of Ruth (Lau, Goswell, 2016), but for others it is a matter of admitting the limits of our evidence. In his very recent commentary on Ruth, Jeremy Schipper (2016) eventually settles on the early Persian period (late 500s-early 400s B.C.E.) as the date of Ruth, but he qualifies his claim saying, “no single piece of evidence definitively determines the date,” and that his case is “extremely tentative” (p. 22). On the other hand, there are scholars that try to build a cumulative case for a particular origin and purpose, drawing on linguistic, legal, and literary evidence. Put more precisely, these scholars try to evaluate the form of Hebrew used in Ruth – is it the more ancient Standard Biblical Hebrew, or is it the younger Late Biblical Hebrew? They look for genetic-developmental relationships between various law codes in Torah and those described in Ruth to establish a relative dating. Last, they try to match the various details and/or the wider argument of the book with a reasonably paired moment in Israel’s history (i.e. “message fit”). As the logic goes, any one of these components may suggest the probability that Ruth comes from a particular period and that it may address a particular matter.

Following these lines of investigation, scholars tend to date Ruth to one of three periods: the monarchic period, the exilic period, or the post-exilic period (a.k.a. Second Temple period); with each categorization largely correlating with a particular view on the book’s purpose. Kirsten Nielsen (1997) is representative of a strand within the monarchic group, arguing that Ruth would have served to neutralize any claims against David/the House of David over its association with Moab, a traditional enemy of Israel. Edward Campbell (1975), who also dates Ruth to the monarchic period, takes a simpler view and says that Ruth was most likely a didactic text that encouraged readers to emulate the kind and loyal (hesed) behavior of the story’s characters. Filling a minority position, Christian Frevel (1992) and Tod Linafelt (1999) position Ruth in the exilic period. Frevel hears in Ruth a call to exiled Judeans to return from Babylon to the homeland, which makes his position analogous to Campbell’s exhortation toward positive behavior. Alternatively, Linafelt believes that Ruth’s author composed the book with Samuel in mind. In the same way that Samuel highlights some of the negative impacts David had on Israel, Ruth highlights some of the ambiguities in David’s ancestry. Samuel and Ruth work together to force the reader to consider the conundrums of the monarchy. Finally, a good number of scholars (Zakovitch, 1990; Eskenazi and Frymer-Kensky, 2011) set Ruth in the post-exilic period, believing that it came to counteract exclusivist tendencies among particular groups within the return community (cf. Ezra-Neh).

Evaluating the Evidence

While there has been a recent revival of interest in the historical development of ancient Hebrew and in the creation of typological periodizations within the language (cf. Rezetko and Young, 2014), such investigations have long been a part of research in Ruth (Driver, 1892; Eissfeldt 1964). Scholars have postulated that if Ruth consistently employs an old form of Hebrew, then it is likely a more ancient text. It would be akin to Shakespearean plays in Western literature – they continue to circulate at present, but their language indicates that these stories have their origins in an earlier time. Alternatively, if Ruth includes late forms and constructions, then the book (though not the characters and events in the story) would come from later in time. An analogy here would be encountering a text that is littered with emojis – we would quickly recognize the text as “young” as it employs recently created linguistic symbols. Unfortunately though (at least for those who desire certainty), Ruth appears to have a mix of both ancient and recent linguistic features. At times, characters speak in “thee”-s, thou”-s, and “thine”-s, but in other places the story has the equivalent of modern slang. With evidence on either side, interpreters suggest explanations (cf. Fischer 2001; Campbell), but none have been able fully to win over the other side.

In addition to investigating Ruth’s Hebrew, scholars have also examined the apparent legal customs/activities that play such a key role in the book. Somewhat like the linguistic argument, the hope is that if we can establish a relative position for a practice in Ruth vis-à-vis a related practice in another book – particularly a book whose date we can fix with certainty – then we will have at least a relative date for Ruth. In ch. 2, Ruth gleans in Boaz’s fields (cf. Schipper), and in ch. 4, Boaz seems to suggest that Naomi is/has been in possession of land (cf. Matthews and Benjamin, 2006), both of which relate to various law codes in Torah, but the greatest amount of attention has gone to Boaz’s legal transaction in the city gate (Ruth 4:1-12). The story appears to engage levirate law (Deut 25) and redemption law (Lev 25), which strongly suggest Ruth’s interaction with core legal traditions, but here again scholars debate the significance of the connections. There is one camp that sees a linear development to the levirate custom moving from a broad pool of potential redeemers (i.e. Ruth), to a narrower pool of just eligible male family members (i.e. Judah and Judah’s sons in Gen 38), to the narrowest pool of only brothers who live together (Deut 25) (Carmichael, 1979; Weisberg, 2009). Alternatively, there is another camp that has accepted the restrictive move from Gen 38 to Deut 25, but which then sees Ruth as a voice reacting to Deut 25 and its limiting stance. Ruth comes to throw the doors open to participation in the levirate custom (Davies 1981; Zevit, 2005). So we see that both camps use the same evidence to argue for competing relative positions for Ruth, and the debate remains at a standstill. Before moving on to arguments related to “message fit,” it is worth noting that two studies (Embry, 2016; Jones, 2016) have come out in recent years that try to relate Ruth’s marriage to Zelophehad’s daughters (Num 27, 36) and the desire to let women inherit while also protecting family land holdings (cf. Tobit). These studies may provide a new point of reference against which to compare Ruth and its practices, but as of yet, there has not been enough time for scholars to critically engage these new ideas.

Finally, we are left to argue over whether we can ascribe a particular argument or message to Ruth, and if this is possible, if we can associate this message with a circumscribed moment in Israel’s religio-intellectual development. Of all the lines of argument for Ruth’s origin and purpose, this approach is noticeably the most vulnerable to circular reasoning – if one’s date for the book influences one’s belief about its message or vice versa, then we are assuming our conclusion – but the effort will still be valuable if it helps us probe aspects of the text. Further, while open to the charge of circularity, it is also possible that we could hit on a historical accuracy through this investigation.

If the reader will allow the author to step more overtly into the frame of this study, I would suggest that we should begin by rejecting the idea of Ruth as a simple didactic tale or idyllic novella. Ruth certainly is a model character within the story, and Boaz also seems to go beyond what Torah strictly requires of him. However, there is ample reason to see a darker shade to the remaining characters in the story. As background, the un-named crowds of Bethlehemites appear either to be ambivalent towards Ruth, or they are a menace to her. The typical field hand poses a threat to Ruth’s personal safety (Ruth 2:9, 15-16, 22), the closest redeemer backs out of his deal to procure Naomi’s land when he learns that Ruth comes with the deal (Ruth 4:6), and the elders of the town say nothing when this man shirks his responsibility. Some may suggest that the elders do bless Boaz’s marriage to Ruth (Ruth 4:11-12) and that the town’s women rejoice at the birth of Ruth’s child (Ruth 4:14-15, 17), but certain portions of their “blessings” seem suspect. The elders compare Boaz and Ruth to Judah’s liaison with Tamar (Ruth 4:12), which may be a backhanded reference to the scene in Ruth 3, and the women of Bethlehem cut Ruth out of the relationship in their final attribution of Obed’s parentage (Ruth 4:17). Moving closer to home, Naomi initially tries to separate from Ruth in ch. 1 (vv. 8-18), and then she allows Ruth to go and glean in the fields in ch. 2 without warning her of the danger that she faces, though she is well aware that it exists (Ruth 2:22). More poignantly, Naomi is the one to mastermind the plan in ch. 3 – a transparent attempt to have Ruth seduce Boaz and thereby gain his provision (Zakovitch, 1979; Yavin, 2007). Thus, it seems to me that Ruth is not simply a story holding forth characters for emulation. However, this is only one of the three possible arguments that scholars ascribe to the book. We must introduce a further form of analysis to discount the idea of Ruth as a political apology.

In recent years, scholars of the HB/OT have become interested in how certain biblical books reference other biblical books (“re-use” or “inner-biblical citation/interpretation”), a path of study that Ruth scholars have willingly followed (Beyer, 2014). [2] Through careful analysis of repeating motifs/themes and unique phrases, interpreters now argue that the author of Ruth has intentionally cast various characters as re-embodiments of great figures from Israel’s history (Jones). There is not space here to evaluate the evidence for each connection, but we can outline the following as possible re-uses: Ruth is a new Abram, a new Patriarch (Isaac, Jacob, Moses) of Israel, a new Rebekah, a new Tamar, and a renewed mother of Moab. Alternatively, Elimelek and Naomi stand out as re-enactments of the failures of the ancestors. Elimelek follows Abram’s example by abandoning the land during a famine, while Naomi mirrors Judah’s attempts to send away a foreign daughter-in-law with a legitimate claim on a levirate partner. These observations, then, provide a second perspective through which to evaluate the message or argument of Ruth. Those that place Ruth in the pre-exilic period frequently argue that the author was trying to demonstrate that, while David did have Moabite ancestry, his ancestor Ruth was an exceptional Moabite, and so David (or the Davidic scion) is still acceptable as a ruler of Israel. The author’s decision to cast Ruth in the mold of Israel’s greatest heroes and heroines would certainly support such a reading of Ruth, but this is only one strand within the story. If a pro-David writer was trying to win over skeptics, it is less clear why this person would associate the Bethlehemite community (sans Boaz) with the failings of the ancestors. Such a literary creation seems just as likely to turn non-Judahites against Bethlehemites/Judeans (i.e. the other half of David’s parentage) specifically, or to offend them all together and turn them against the story. [3]

As a last option for understanding Ruth, I would offer that Ruth does fit well when set against the background of the early post-exilic period. The literature on this time is vast and continues to grow, but it is safe to say that the small community in Judea in the late 500s to early 400s B.C.E. conflicted over various societal issues, one of which was how they should define the boundaries of their community. The prophet Zechariah believed that Jerusalem would throng with foreigners who would count as Yhwh’s people (Zech 2:15[EV 11]), but other persons from the Ezra-Nehemiah narrative feel that foreigners have no part in the community (Ezra 4:1-3; 9:1-4; Neh 13:1-3). This is not to say that Ruth reacts directly to the Ezra-Nehemiah text, nor should we read Ezra-Nehemiah uncritically as plain history, but it is reasonable to hold that community cohesion and in-group/out-group questions were live topics at the time. Within this debate, we can see how Ruth provides a counterfactual to a certain exclusivist perspective toward outsiders. The text is not so bold as to claim that all non-Israelites/Judeans should count as people of Yhwh, but it does demonstrate that there are cases where a foreigner can reasonably measure up to the standard of a true Israelite. For her part, Ruth is surprisingly Torah pious – she honors her mother, she follows gleaning law, she avoids fornication, and she encourages redemption. There are even parts of her life that mimic events in the lives of the nation’s founders. On the other hand, it is also true that bonafide members of the community can fail to follow the basic standards of Israel’s identity. The Bethlehemites do not treat a foreigner in their midst well, and Elimelek and Naomi appear to repeat the mistakes of the ancestors. The only figure to run counter to this characterization is Boaz. He goes out of his way to support Ruth, and in so doing, Yhwh takes him up into her storyline and allows Boaz to participate in the ancestry of David – Israel/Judah’s archetypical king (cf. Zech 12:8). If this reading of Ruth is on the correct track, it suggests for us both a date and a purpose for the book that accounts for the varying characterizations within the story and for the impact that an author may have sought to have on his/her community of readers and hearers.

Bibliography

Beyer, Andrea. Hoffnung in Bethlehem: Innerbiblische Querbezüge als Deutungshorizonte im Ruthbuch . Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 463. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2014.

Campbell, Edward F., Jr. Ruth: A New Translation with Introduction, Notes, and Commentary . Anchor Bible 7. Garden City: Doubleday, 1975.

Carmichael, Calum M. Women, Law, and the Genesis Traditions . Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1979.

Davies, Eryl W. “Inheritance Rights and Hebrew Levirate Marriage: Part 2.” Vetus Testamentum 31, no. 3 (1981): 257-68.

Driver, S. R. An Introduction to the Literature of the Old Testament . 4th ed. International Theological Library. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1892.

Embry, Brad. “Legalities in the Book of Ruth: A Renewed Look.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 41, no. 1 (2016): 31-44.

Eissfeldt, Otto. Einleitung in das Alte Testament unter Einschluß der Apokryphen und Pseudepigraphen sowie der apokryphen- und pseudepigraphenartigen Qumrān-Schriften: Entstehungsgeschichte des alten Testaments . 3., neubearbeitete Aufl. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), 1964.

Eskenazi, Tamara Cohn, and Tikva Frymer-Kensky. Ruth: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation . JPS Bible Commentary. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2011.

Fewell, Danna Nolan, and David M. Gunn. Compromising Redemption: Relating Characters in the Book of Ruth . Literary Currents in Biblical Interpretation. Louisville: Westminster/John Knox, 1990.

Fischer, Irmtraud. Rut: Übersetzt und ausgelegt . Herders Theologischer Kommentar zum Alten Testament. Freiburg: Herder, 2001.

Frevel, Christian. Das Buch Rut . Neuer Stuttgarter Kommentar, Altes Testament 6. Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk, 1992.

Gow, Murray D. The Book of Ruth: Its Structure, Theme and Purpose . Leicester: Apollos, 1992.

Greenstein, Edward L. “Reading Strategies and the Story of Ruth.” Pages 211-31 in Women in the Hebrew Bible: A Reader . Edited by Alice Bach. London: Routledge, 1999.

Jones III, Edward Allen. Reading Ruth in the Restoration Period: A Call for Inclusion . Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 604. London: Bloomsburry T&T Clark, 2016.

Kaiser, Otto. Einleitung in das Alte Testament: Eine Einführung in ihre Ergebnisse und Probleme . Gütersloh: Gerd Mohn, 1969.

Lau, Peter H. W., and Gregory Goswell. Unceasing Kindness: A Biblical Theology of Ruth . New Studies in Biblical Theology 41. Downers Grove: Apollos, 2016.

Linafelt, Tod. “Ruth.” Pages xiii-90 in Ruth and Esther . Tod Linafelt and Timothy K. Beal. Berit Olam. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1999.

Matthews, Victor H., and Don C. Benjamin. Old Testament Parallels: Laws and Stories from the Ancient Near East . Fully rev. and exp. 3d. Mahwah: Paulist, 2006.

Nielsen, Kirsten. Ruth: A Commentary . Old Testament Library. Translated by Edward Broadbridge. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1997.

Rezetko, Robert, and Ian Young. Historical Linguistics & Biblical Hebrwe: Steps Toward an Integrated Approach . Ancinet Near East Monographs 9. Atlanta: SBL Press, 2014.

Schipper, Jeremy. Ruth: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary . Anchor Bible 7D. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

Weisberg, Dvora E. Levirate Marriage and the Family in Ancient Judaism . HBI Series on Jewish Women. Lebanon: Brandeis University Press; University Press of New England, 2009.

Yavin, Zipora (Zipi). “Ruth – The Fifth Mother (A Study of the Scroll of Ruth): The Semantic Field as a Ground of Confrontation between Two Giants: The Ephraimite Author against the Judean Author.” [Hebrew] Jewish Studies 44 (2007): 167-213.

Zakovitch, Yair. “Between the Threshing Floor Scene in the Scroll of Ruth and the Tale of Lot’s Daughters.” [Hebrew] Shnaton 3 (1979): 29-33. . Ruth: With an Introduction and Commentary . [Hebrew] Miqra le-Yisrael. Tel Aviv: Am Oved Publishers, 1990.

Zenger, Erich. Das Buch Ruth . Zücher Bibelkommentare 8. 2. Aufl. Zürich: Theologischer Verlag, 1992.

Zevit, Ziony. “Dating Ruth: Legal, Linguistic and Historical Observations.” Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 117 (2005): 574-600.

[1] Much of the content in this essay is a review of the work that I have done in Reading Ruth in the Restoration Period: A Call for Inclusion .

[2] We should note that some scholars have tried to assign Ruth a date by positioning it relative to the books that it cites. However, dating other books in the HB/OT can be as difficult as dating Ruth, so such attempts remain in dispute.

[3] This point seems to create similar problems for the minority of scholars that set Ruth in the exilic period.

Add new comment

- Featured Essay The Love of God An essay by Sam Storms Read Now

- Faithfulness of God

- Saving Grace

- Adoption by God

Most Popular

- Gender Identity

- Trusting God

- The Holiness of God

- See All Essays

- Conference Media

- Featured Essay Resurrection of Jesus An essay by Benjamin Shaw Read Now

- Death of Christ

- Resurrection of Jesus

- Church and State

- Sovereignty of God

- Faith and Works

- The Carson Center

- The Keller Center

- New City Catechism

- Publications

- Read the Bible

U.S. Edition

- Arts & Culture

- Bible & Theology

- Christian Living

- Current Events

- Faith & Work

- As In Heaven

- Gospelbound

- Post-Christianity?

- TGC Podcast

- You're Not Crazy

- Churches Planting Churches

- Help Me Teach The Bible

- Word Of The Week

- Upcoming Events

- Past Conference Media

- Foundation Documents

- Church Directory

- Global Resourcing

- Donate to TGC

To All The World

The world is a confusing place right now. We believe that faithful proclamation of the gospel is what our hostile and disoriented world needs. Do you believe that too? Help TGC bring biblical wisdom to the confusing issues across the world by making a gift to our international work.

Invitation to Ruth

The Book of Ruth is a well-loved short story. Part of this affection is that the narrative has all the elements of good drama: an engaging plot, interesting characters, tension, romance, conflict, people overcoming hardship, and so much more. The moving account ends like a Cinderella story, in which the two main figures find love, marry, and have children. Some commentators rely on this type of reading as they explain the intent of the book, seeing the major characters and their love for each other as a model of God’s love for us.

Along similar lines, some writers—perhaps even the earliest Hebrew readers of the book—emphasize the moral virtues of the people in the book. For example, in Ruth 3:11, Boaz calls Ruth “a worthy woman;” the Hebrew term for “worthy” is one that reflects integrity, skill, and honor. In the English Bible, Ruth is the eighth book in the Old Testament immediately after the book of Judges, but in the Hebrew Bible, it comes right after the book of Proverbs. Why so? In the last chapter of Proverbs, the author asks whether anyone can find “a worthy woman” (Prov 31:10). The Book of Ruth answers the question of Proverbs with a historical example: Boaz found a worthy woman. In fact, the book refers to Boaz as “a worthy man” (Ruth 2:1). The upright characters of Ruth and Boaz are certainly worthy of emulation, but the theme of moral virtue still does not fully reflect the purpose of the book.

The book has a greater purpose than simply being a moral story of human uprightness. The author tells a story that took place in the time of the judges ( see commentary on Judges for more on this period ), which is one where “there was no king in Israel” (Judg 21:25). The Book of Ruth provides an account of the ancestry of David, perhaps the greatest king of ancient Israel. The story ends by disclosing the fact that Ruth and Boaz are David’s great grandparents. The story, therefore, is not merely a moral story of integrity, but it points ahead to the coming king.

But even David’s appearance is not the climax of the book. David himself ultimately points to the coming of a final king, who is Jesus Christ, the son of David. The genealogy of David at the close of the Book of Ruth (4:18–22) is essentially the same found in the genealogy of Jesus (Matt 1:3–6). The one difference between the two genealogies is that Matthew includes the names of two Gentile women, Rahab and Ruth, in the ancestry of Jesus. One reason for that incorporation is to point to the reality of the inclusion of the Gentiles in God’s kingdom. The glorious conclusion of the Book of Ruth is the coming of the Messiah, and the reader needs to keep this in mind when studying the book.

The Book of Ruth describes the redemption and inclusion of Gentiles into the lineage of David and of David’s son, the Messianic King.

“But Ruth said, ‘Do not urge me to leave you or to return from following you. For where you go I will go, and where you lodge I will lodge. Your people shall be my people, and your God my God.’”

— Ruth 1:16 ESV

The Book of Ruth may be outlined simply according to four scenes, as follows:

Scene 1: In Moab (1:1–18)

A setting of adversity (1:1–5), the lord’s compassion (1:6–9), the great cling (1:10–14), ruth’s confession (1:15–18), scene 2: in bethlehem (1:19–2:23), homecoming (1:19–22), in the fields (2:1–7), the conversation (2:8–17), ruth returns from the field (2:18–23).

Scene 3: At the Threshing Floor (3:1–18)

Hatching a Plan (3:1–6)

At the heap of grain (3:7–13), back to bethlehem (3:14–18), scene 4: at the gate (4:1–22), in the courtroom (4:1–12), the descendant (4:13–22).

1:1 The opening words of the text “in the days when the judges ruled” provide the timing and setting of the story. What do we know of this period? The book of Judges ends with the statement, “everyone did what was right in his own eyes” (Judg 21:25). It was a time of moral relativism, decay, and anarchy. No central political authority or spiritual focus existed in Israel. As a result, the book of Judges records a downhill spiral in Israel’s moral activity. By the end of the book, we read of the downright salacious and obscene story of the Benjaminites. This setting serves as a foil to the Book of Ruth ( see commentary on Judges for more on this period ). Although many in Israel lacked moral fiber and acted in-line with the ungodly Canaanites, not everyone was behaving that way. In this vein, the author invites us to consider Boaz and Ruth. This bright spot in a dark time testifies to the reality that the Apostle Paul would later proclaim, namely that God “did not leave himself without witness” in past generations (Acts 14:17).

Besides the general historical timing of the events of the book, the author opens by explaining that a physical famine had come upon Israel—a likely sign of God’s displeasure with Israel’s unfaithfulness (Lev 26:18–20). The story then becomes particularized, as one man and his family left Israel because of the natural disaster. Ironically, the man was from the town of Bethlehem, a name that means “house of food”! For the reader, the name is also a reminder that this town was the home of the later great king of Israel, David, and the place of birth of the later even greater Messianic king, Jesus.

The text then says that the man traveled to Moab to sojourn there. A sojourner was one who worked in a foreign country but had few of the rights and privileges of the citizenry. He was one who did not own land but was generally in the service of a native (in this case, a Moabite). The Moabites were a pagan people who worshipped the gods Chemosh, Baal Peor, and many others. During the period of the judges, they were an archenemy of Israel (see Judg 3:12–30). So, this Israelite man left his ancestral lands allotted to him by the Lord, and he went to Moab to work under pagan authority. He, therefore, appears to have put his family in harm’s way. Was it the right thing to do? One point to consider is the fact that not everyone reacted to the famine by resorting to sojourning. Apparently, many—like Boaz—remained in the land of promise.

1:2 The names of the family members are important for interpreting the story. The man’s name was Elimelech, which means “my God is king;” his name is ironic, since “there was no king in Israel. Everyone did what was right in his own eyes” (Judg 21:25). This man and his actions were a testimony to the relativism of the time. His wife’s name was Naomi, which means “sweet” or “pleasant.” Later in the story, after much suffering, the woman told the women of Bethlehem not to call her Naomi (“sweet”) but rather to address her as Mara (“bitter”).

Elimelech’s family were Ephrathites. This clan was part of the tribe of Judah that lived near Bethlehem. This denotation is to remind the reader, again, of the future coming of King David: we read in 1 Samuel 17:12 that David “was the son of an Ephrathite of Bethlehem in Judah, named Jesse, who had eight sons.” David was not only from the tribe of Judah and a Bethlehemite, but he was of the very clan of Elimelech’s family.

1:3–5 The family was in dire straits. They lived under famine, and then they came under Moabite authority for “about ten years.” They were obviously affected by their circumstances, as is evident in the fact that the two sons married Moabite women in disobedience to God’s word (see Deut 7:3–4). Tragedy then struck, as both Elimelech and his two sons died. This left Naomi in a grave situation. As an Israelite widow with no sons, she was unprotected and faced destitution, poverty, and perhaps even enslavement. She was now a cast-off, one of the unwanted class. What was she to do?

1:6 Naomi now planned to return to her family’s inheritance in Judah for two reasons. First, her life in Moab had become untenable: she was a widow without any means of support in a pagan society. Second, she heard that God had visited his people and ended the famine. Yahweh had brought the famine, and now he graciously removed it. The text underscores the providence of God over nature.

A leading word appears throughout Ruth 1:6–22: the verb “to return” occurs twelve times. Although this verb has a common usage of a person changing course and physically returning to a place, it also has a spiritual significance in the Old Testament. The Old Testament uses the word to describe a person repenting and turning to God (e.g., Hos 3:5; 6:1; 7:10). Its repetition in the text likely indicates that the characters were not only returning/going to the land of promise, but also returning/turning to Yahweh.

1:7–9 As Naomi began her journey back to Bethlehem, her two widowed daughters-in-law, Orpah and Ruth, accompanied her. Ironically, the two of them would arrive in Bethlehem in the same state as Naomi in Moab; they would be widows with no male protection and sojourners in a foreign land. According to ancient Near Eastern law, the two women were not required to go with Naomi but had every right to return to their own families. Naomi urged them to return to their Moabite families where they would receive care and protection. She then pronounced a blessing on them by invoking the name of Yahweh, the covenant name of the God of Israel. She called for Yahweh to “deal kindly” with them—a strong word in Hebrew ( chesed ), best translated as “covenant loyalty.” Naomi was requesting that the covenant God of Israel would show covenant loyalty to these two Moabite women and entrusting them to his care.

1:10–13a Although Orpah and Ruth asserted that they would yet go with their mother-in-law, Naomi was insistent that they do no such thing. She argued that Israel held no prospects for these Moabite women. Naomi would have nothing to offer them. She was indigent, widowed, and had no sons who could marry Orpah and Ruth. Here, the reader is introduced to the important Hebrew custom called “the levirate law” (the word levir is Latin for “a husband’s brother”). The law is related most clearly in Deuteronomy 25:5–6:

If brothers dwell together, and one of them dies and has no son, the wife of the dead man shall not be married outside the family to a stranger. Her husband’s brother shall go in to her and take her as his wife and perform the duty of a husband’s brother to her. And the first son whom she bears shall succeed to the name of his dead brother, that his name may not be blotted out of Israel.

Naomi was emphasizing for Orpah and Ruth that she has no sons to perform this custom and, therefore, was attempting to dissuade them from traveling with her. (As an aside, this law will play an important role later in the book.)

1:13b–14 Naomi then highlighted her own bitter plight that would have negative effects on Orpah and Ruth. She concluded that “the hand of the Lord has gone out against me.” Naomi understood that her adversity was not due to chance or mere circumstance, but history was playing out according to the providence of God. Naomi’s rational plea resulted in a divergence of response: Orpah kissed Naomi goodbye, but Ruth clung to her so as not to be separated.

1:15–16a Naomi then urged Ruth to follow her sister-in-law and return to Moab. Ruth, however, was resolute. She dedicated herself to Naomi and was determined to follow her to Israel. This commitment is underscored by a series of statements grammarians call by the Latin phrase idem per idem (a figure of speech in which the same verb or noun is used of the actions of two different people). The series of statements “where you go , I will go ”; “where you lodge I will lodge ”; “your people shall be my people ”; and so on underscores the oneness of purpose and unity of action between the two women. Ruth was pledging undying allegiance and fidelity to Naomi.

1:16b–18 Ruth’s vow, however, was not only to Naomi. She declared the idem per idem , “your God, my God.” That affirmation is a non-verbal statement (no verb is stated explicitly), having a unique force in the Hebrew. The claim was like a thunder-clap. Back in Ruth 1:15, Orpah had returned to her gods. Ruth, on the contrary, was renouncing the polytheism of the Moabites and embracing the monotheism of the Hebrews. Ruth 1:17 confirms this conversion as Ruth invokes the name of the Lord, the name Yahweh, the covenant name of the God of Israel. Ruth’s conversion and oath silenced Naomi.

The conversion of a Gentile, pagan Moabite to the true faith ought to shock us as well. This conversion further points to a greater reality: The Gentiles are included in the people of God by faith. And, as we mentioned in the introduction , this is one important reason that Matthew includes Ruth (and Rahab) in the genealogy of Jesus (Matt 1:5).

1:19 Nothing is said in the text about the journey to Bethlehem. It simply says that they “went on until they came to Bethlehem.” Thus, a time gap exists between Ruth 1:18, 19. This trip was approximately 40–50 miles or 65–80 kilometers in rugged terrain that was mostly uphill. It would have taken days to complete the trip. This gap should remind us to slow down when reading and realize that some events take a long time to unfold.

When the women arrived in Bethlehem, the entire town was “stirred.” This word in the original carries the idea of “being in commotion,” and so the town was in turmoil and confusion because of their unexpected arrival. The gossip was abuzz, as the women of the town asked, “Is this Naomi?” This question may have had a malicious angle, or it may have been asked out of mere curiosity.

1:20–21 Naomi responded directly by using a wordplay on her own name. Back in Ruth 1:2, her name was defined as meaning “sweet” or “pleasant.” She told the women of Bethlehem not to call her that, but rather, they were to call her Mara, meaning “bitter.” Naomi had used that word back in Ruth 1:13 when she told Orpah and Ruth that “it is exceedingly bitter to me . . . that the hand of the Lord has gone out against me.” Her name change reflected her understanding of the providence of God. She declared in Ruth 1:20–21 that God had done four things to her: dealt bitterly with her, brought her back empty, testified against her (the verb “testified” can mean “afflicted” in the original), and brought trouble upon her. These were all bitter providences. Naomi, however, was not blaming God for her situation. She was simply recognizing God’s hand in all the eventualities of life and responding with endurance and patience to them all.

1:22 This section ends with the statement that Naomi and Ruth had come to Bethlehem “at the beginning of the barley harvest.” The barley harvest was the first harvest of grain during the agricultural year, and it was soon followed by the wheat harvest. This year, the harvest was rich (Ruth 1:6), and abundant workers would be needed in the fields. Ruth, then, would be able to find work, feed the family, and meet Boaz. This certainly was God’s timing, and it was a sweet providence.

2:1 The opening verse of this section is a parenthesis, interrupting the flow of the story. The author now introduces the reader to a man named Boaz. Boaz was a “relative” of Naomi’s husband Elimelech. This word had a broad range of meaning in ancient Hebrew and, therefore, the reader is uncertain of the exact relationship between the two men. The verse also says that Boaz was of Elimelech’s “clan,” which was an extended family based on consanguinity (a multi-generational blood relationship). Yet, the drama heightens in the story because we do not yet know how close the relationship between the two men is.

Boaz was “a worthy man;” the word “worthy” can refer to wealth, but it often can mean integrity, valor, and honor. His character was confirmed by the meaning of his name: “in him is strength.” Later, when Boaz’s great-great-grandson Solomon built the temple in Jerusalem, he called one of the foundational pillars of the edifice “Boaz” (1Kgs 7:21). The man Boaz and the pillar of the same name shared similar characteristics; one was a pillar in Bethlehem, upholding the community, and the other was a pillar in the temple, upholding the monumental structure.

2:2–3 Here the author picks up the story of Ruth again. According to Hebrew law, the farmer must only glean and reap his fields one time during the harvest; he was not to strip his fields bare (Lev 19:9–10). He was to leave the edges of his fields unharvested, and what was missed in the fields was to be left for the disadvantaged in Israel. Ruth asked Naomi if she could go to the fields and glean after the reapers, as one of the indigents in the land.

After receiving her mother-in-law’s permission, she went out to labor in the fields, and “she happened to come” to the field belonging to Boaz. How is the reader to understand this comment that appears to say that she came to this field by chance? Perhaps it was a tongue-in-cheek line by the author who was aware of God’s providence driving the story. Or, perhaps, from Ruth’s perspective it appeared to have been by chance; she had not planned it. The popular statement attributed to John Flavel is helpful in understanding the perspective of the writer in this passage: “God’s providence is like Hebrew, it must be read backwards.”

2:4–7 Ruth 2:4 begins with the word “behold”; this is an emphatic statement of surprise. Our new character is now reintroduced. Boaz’s timing was perfect because it was God’s timing. Here was the industrious, hard-working, “worthy” man coming to oversee the work; he was not an absentee landlord. Inspecting the work, Boaz noticed an unfamiliar person, and he discreetly asked his head reaper about her. Ruth’s reputation as an upright woman had preceded her work in the field; her care for her mother-in-law gave her a sterling name among the people of Bethlehem. In addition, her work in the field testified to her honorable, diligent character. The chief reaper explained to Boaz that Ruth worked in the field all day “except for a short rest.” A precise, direct reading of the reaper’s claim is, “This (field) is her dwelling, the house is little.” In other words, the field has been Ruth’s dwelling place all day long, and her house in town meant little to her. She was a person of industry and fortitude; in fact, she was much like Boaz!

2:8–9a After hearing the report, Boaz turned to speak directly to Ruth. He spoke to her with kindness and respect. Then he provided for her in two ways. First, he gave her protection. He told her to glean only in his field and to keep close to his “young women.” These women were likely not slaves or servants but young, unmarried women from Boaz’s clan—well protected due to kinship. He also told the young men working in the field not to assault her. Ruth, as an indigent foreigner, was vulnerable and so Boaz safeguarded her well-being.

2:9b–16 Second, Boaz provided for Ruth’s sustenance. He told her to take from the water provided for the laborers in the field. He then invited her to a meal prepared for the reapers, that included roasted grain. When they returned to work, Boaz told the reapers to let Ruth glean right in the areas where they labored: here she would not get mere leftovers but the very best pickings of the crop. Additionally, he ordered his workers to leave sheaves of grain that she could easily pick up and bundle.

Ruth responded to Boaz’s actions with great humility and surprise. Ruth uses a play on words here (the verb “take notice” and the noun “foreigner” are related), expressing her wonder at the generosity of Boaz. Foreigners were those who usually lived unnoticed and unrecognized: Ruth thus wondered, why was she noticed by Boaz? She was further startled that he would speak to her so kindly and comfort her although she was merely “a servant” and not “even one of your servants.” Here again Ruth’s humility and honesty shone forth.

Finally, Boaz pronounced the blessing of Yahweh on Ruth, calling for the Lord to bring Ruth’s deeds and conduct to full fruition. In this blessing, he fully recognized Ruth’s conversion, as he described her relationship to the Lord as “under whose wings you have come to take refuge.” Boaz pictured God as a mother bird who protects its young; this is a metaphor in the Old Testament used of God’s people belonging to him and under his care (e.g., Deut 32:11; Exod 19:4).

2:17 Ruth continued to glean until the evening. Then she went and threshed what she had gleaned, separating the good grain from the husks. After this hard labor, Ruth came away with about an ephah of barley (an ephah is about two-thirds of a bushel or eight liters in volume and 30 pounds or 14 kilograms of weight, capable of producing 672 slices of whole grain bread). This was a generous amount for her labors.

2:18 After her labors, Ruth returned to Naomi and showed her the liberal amount of grain she had gleaned. She then gave to Naomi the food “she had left over after being satisfied.” The same wording appeared earlier in Ruth 2:14; in other words, Ruth provided Naomi with some of the roasted grain she had received from Boaz at mealtime in the fields. She not only dragged home the 30 pounds or 14 kilograms of barley from the field, but she also brought home a meal for Naomi. Ruth was one who put others before herself.

2:19–20 Naomi responded by invoking two blessings on Boaz. Naomi’s excitement particularly shines through as she describes the man as “one of our redeemers.” The Hebrew term “redeemer” is go’el , and it plays an important role in the Book of Ruth.

What Is a Kinsman-Redeemer?

A go’el was one who delivered his kin from difficult circumstances, redeeming them from danger. In ancient Israel, the go’el had four basic duties:

1. He was to buy his kin out of bondage, usually brought about when someone went into debt and indentured himself to another Hebrew (Lev 25:47–49; Deut 15:12–17);

2. He had the duty to buy back tribal land that a relative had sold (Lev 25:23–25);

3. He was to perform the Levirate Law by marrying a widow in the family who had no male heirs and produce a progeny for the dead husband (Deut 25:5–6; see comment on Ruth 1:11);

4. He was to avenge the blood of a relative (Num 35:16–19).

The concept of redemption by a go’el was a wonderful picture in Scripture of God’s work for his people. Throughout the Old Testament, the term go’el was used for God interceding on the behalf of his people (Job 19:25–26; Psa 19:14). The exodus out of Egypt was the great redemptive act of the Old Testament wherein God redeemed his people from bondage (Exod 6:6–8). In the New Testament, Jesus is the go’el who brings liberty to his people (Luke 4:16–21). He released his kin from bondage (Rom 8:29), he reclaimed an inheritance for his people (1Pet 1:3–4), he raised up a seed in his name (Eph 1:5), and he served as blood avenger (see the book of Revelation). Jesus, the true go’el has come!

2:21–23 Finally, observe how Ruth is described as “the Moabite.” The reference to this status in Ruth 2:2 serves as an inclusio , reminding the reader from the beginning to the end of the chapter that Ruth was an outsider who was in need of redemption.

Scene 3: At the Threshing Floor (3:1-18)

Ruth had been working in the field of Boaz for about three months, until the end of the wheat harvest (Ruth 2:23). No redemptive activity on the part of Boaz had taken place during this time, so Naomi decided to act and help set in motion the process.

3:1 Some commentators argue that Naomi’s actions were manipulative—almost deceitfully so—in order to get what she wanted. Such underhanded dealings are unlikely because Naomi cared much for Ruth’s welfare, and she was concerned for the temporal provision that a redeemer would supply. Indeed, the two of them were eking out a living, but Naomi was at the point that she may have to sell her land to survive (Ruth 4:3). In addition, Ruth, being a Moabite, may have not known how Israelite redemptive laws worked and, thus, Naomi was guiding her.

3:2 Naomi told Ruth to go down to the threshing floor that very evening where Boaz would be overseeing the winnowing of his crop. He would be there all night in order to guard his harvest. Naomi then explained what Ruth was to do: she was to wash herself, anoint herself, and change her clothes. Some commentators believe that Naomi was instructing Ruth to be seductive or alluring. More likely, her actions demonstrated to Boaz that Ruth’s time of mourning was over. In 2 Samuel 12:20, David did the same three things to indicate that he had completed his mourning over his dead child.

3:3–6 Ruth should wait until Boaz was alone before approaching him. Again, this was not a case of scandalous entrapment. She was approaching him privately so that Ruth’s reputation would be preserved in case Boaz rejected her proposal. He was a godly man who would not take advantage of her but would handle matters in a proper way. But it would surely seem that Naomi’s command that Ruth “uncover his feet and lie down” next to Boaz was a lure to sexual activity. To the contrary, it was a highly symbolic act. By entering in and lying at Boaz’s feet under the edge of the blanket, Ruth was coming to the place reserved for a wife. She was, in effect, saying that she wanted to be his wife through redemption. Her act was one of submission and not scandal. The next section of the book provides further testimony to the virtuous activity of both Ruth and Boaz.

3:7 The drama continues as Boaz finishes his food and drink and then lays down to sleep. His “heart was merry”—meaning “to be satisfied or content” and not indicating drunkenness or susceptibility to enticement. Ruth, then, came to him “softly,” a translation that wrongly assumes a tantalizing pose on Ruth’s part. That word, however, bears the sense of her coming to Boaz in “secrecy” and “privacy” (see its use in 1Sam 18:22). This was not a scene of seduction.

Ruth “uncovered his feet” and lay down. Again, some writers see this act as one of sexual activity. To be fair, the verb “uncover” can be used that way in the Old Testament (see, e.g., Lev 20:11, 19–21). On the other hand, the phrase used elsewhere is “to uncover one’s nakedness” and not “to uncover one’s feet.” We ought to take Ruth’s action at face value: she uncovered Boaz’s feet by lifting the blanket, laying down next to his feet, and covering herself with the blanket. Ruth will later explain her metaphorical intent by asking that Boaz “spread your wings over your servant, for you are a redeemer.” Ruth’s placing the blanket over herself was imagery that she wanted to come under Boaz’s redemptive protection and care. In support of this idea, in Ruth 2:12, Boaz had talked to Ruth about her having come under the “wings” (i.e., protection) of Yahweh.

3:8–13 Boaz woke up “startled” and asked the woman to identify herself. If the two of them were in the midst of a sexual encounter, this question would make no sense. The entire scene was Ruth’s humble and virtuous request for Boaz to act the part of a redeemer. Boaz recognized her sterling character, explaining that the entire town of Bethlehem knew Ruth as a “worthy woman” (similar to the description of Boaz in Ruth 2:1). They were both people of integrity and honor, and to view this scene as a seedy, seductive event diminishes their upright characters.

Boaz promised to act, but he introduces a possible snag to his plans: another go’el was closer in kinship and had the first right of refusal. This meant that Boaz would have to find a way to encourage the nearer redeemer to decide the matter. In any event, Boaz gave his oath to Ruth, and he sealed it by using the covenantal name of Yahweh. His vow was based on the very existence of the God of Israel.

3:14 Ruth stayed at the threshing floor for the remainder of the night and lay at Boaz’s feet. This was a place of protection with no sense of impropriety. The scene portrays restraint and caution. Ruth then arose before dawn: Boaz was concerned for her reputation and, thus, made certain that she would be gone early and unrecognized.

3:15 Before she left, Boaz gave her six measures of barley. Some commentators believe this to have been some type of payment for sexual favors (cf. Gen 38, in which Judah paid-off Tamar for prostitution). Such an interpretation is unseemly. Instead, the grain served as a pledge from Boaz to both Ruth and Naomi that he would keep his word. He was providing a token as a promise that he would seek redemption that very day. The last line of the verse confirms Boaz’s intentions. The ESV renders the line as “then she went into the city” (emphasis mine). The problem is that the Hebrew text has a masculine subject, that is, “then he went into the city.” The point of the masculine subject in the text is that Boaz was serious about his pledge, and he went into Bethlehem immediately to do his duty.

3:16–18 Ruth returned to her home, and she reported to Naomi all that took place. She concluded her account by quoting Boaz that it would not be right for Ruth to return to Naomi “empty-handed.” This is the same word used back in Ruth 1:21, where Naomi declared that Yahweh had returned her from Moab “empty.” Instead, Naomi will no longer be empty, but she will be full because of Boaz’s redemptive promise.

4:1 The setting of the story now shifts, and Boaz appears at the main gate of Bethlehem. The central gate of an ancient town served as the gathering place for the elders of the city, and legal matters were decided there: it was the place of the ancient courtroom. Boaz’s timing was perfect, for the closest redeemer passed by the gate. Boaz called to him, “Turn aside, friend.” The word “friend” in Hebrew is actually two words that commonly mean “whoever, such and such.” The man was not called by name, and this was significant. Perhaps the omission of his name was a mark of shame because he ended up not doing his duty in the matter of redemption (see Deut 25:9–10). In other words, he made his own name disreputable.

4:2–4 Now with the closest redeemer present, Boaz gathered ten elders of the town to serve as a judicial quorum. He then laid out the case before them. We learn that Naomi was planning to sell Elimelech’s land in order to support herself; she was facing indigence. Land, however, could not be sold in perpetuity but must be redeemed by the clan (Lev 25:23–24). Boaz was forcing the nearest go’el to make his decision, and he responded with “I will redeem it.”

4:5–6 Boaz then provides a plot twist: if the nearest go’el would redeem Naomi, he would also have to act on the Levirate law, marry Ruth, and raise descendants for the dead. The first redeemer now drew a different conclusion, “I cannot redeem it.” He knew that if he acted on the redemption, it would sow familial discord because his own inheritance would have to be shared with his progeny and with Ruth. Also, if he had no other sons, the entirety of his estate would pass to the son of the levirate union. He decided to protect his own interests.

4:7–11a So Boaz received the right of redemption and sealed it with an ancient custom of giving one’s shoe to another. This was an act of attestation to the transaction. The elders and people at the gate legally validated the deal by bearing witness to the court case. Their attestation in the original language was only one word: “Witnesses!” All of them spoke in unison and agreement.

4:11b–12 The people, finally, pronounced a three-part blessing on Ruth and Boaz. First, they asked that Yahweh would make Ruth like Rachel and Leah. These two were wives of Jacob, along with their handmaidens, gave birth to the twelve sons of Jacob and, thus, “built up the house of Israel.” Second, they called for Boaz to continue acting “worthily” (same word used of Boaz in 2:1 and Ruth in 3:11), and they asked that his name would be remembered in Bethlehem. And, finally, the people prayed that the house of Boaz would be like “the house of Perez whom Tamar bore to Judah.” This request refers to Genesis 38, in which Tamar, a foreign woman, resorted to the Levirate law to perpetuate the family lines of the tribe of Judah. The people of Bethlehem were from that tribe, and thus, they had great hope that the progeny of Ruth and Boaz would also continue the line of Judah.

4:13 In Ruth 4:13–17 we see the story of the book coming to an initial climax. Ruth’s story has ascended in an arc: she arrived in Bethlehem as “not one of Boaz’s servants” (Ruth 2:13), eventually announced to Boaz, “I am your servant” (3:9), and now, in the present passage, she is declared to be his wife. She then conceived; the sovereignty of God was unmistakable in this event as he opened her womb and she bore a son. Here was the male heir who would carry on the family name and inheritance!

4:14–16 The women of the town showed up and pronounced a blessing on Naomi. They had first appeared in the account back in Ruth 1:9, in which they perhaps denigrated Naomi by asking, “Is this Naomi?” Now they bless Yahweh for providing her with a redeemer. The two speeches of the women of the town serve as an inclusio, bracketing the events in Bethlehem. The women, in a sense, function as a chorus commenting on the movement of the story from bitter to sweet.

4:17 The women of Bethlehem named the child “Obed,” which means “the one who serves.” Obed’s name was apt because he served to preserve the line of Elimelech and the family’s land inheritance. The author now provides an even greater significance in Obed’s carrying on the lineage by recording that Obed became the father of Jesse and the grandfather of David, the great king of Israel. Thus, the reader begins to see a larger picture: we see God at work establishing the royal line of Israel through this unlikely pairing of Ruth and Boaz.

4:18–22 The Book of Ruth ends with a broader genealogy that traced the lineage from Perez, Judah’s son, to David. This more extensive genealogy exists to link David back to Judah, who was promised a royal line and kingship (see Gen 49:8–10). Observe that the genealogy is selective; it does not list every generation from Perez to David. The genealogy lists ten names, and in Hebrew culture the number ten often signifies completion. The idea behind this genealogy is not to provide a historically exhaustive list, but to show that the genealogy reaches its climax and completion in the person of David.

This selective genealogy, however, not only looks backward, but it also looks forward. The list of the ten descendants, from Perez to David, is exactly what Matthew records in the genealogy of Jesus (Matt 1:3–6), adding the three women Tamar, Rahab, and Ruth. This demonstrates that the genealogy found at the end of the Book of Ruth finds its ultimate climax in the coming of Jesus, the son of David, and the final king of Israel. Observe how the main characters of the Ruth story—Naomi, Boaz, and Ruth—have faded from the narrative. Their story is not the main story. The coming of the Messiah is the be-all and end-all of the Book of Ruth.

Bibliography

Block, D. L., Judges, Ruth. New American Commentary. Nashville, TN: B&H, 1999.

Campbell, E. F., Ruth. The Anchor Bible, vol. 7. New York: Doubleday, 1975.

Duguid, I. M., Esther and Ruth. Reformed Expository Commentary. Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2005.

Ferguson, S. B., Faithful God: An Exposition of the Book of Ruth . Darlington, England: Evangelical Press, 2005.

Hubbard, R. L., The Book of Ruth. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1989.

Permissions

The text of Ruth , excluding all Bible quotations, is © 2023 by The Gospel Coalition. The Gospel Coalition (TGC) gives you permission to reproduce this work in its entirety, without any changes, in English for noncommercial distribution throughout the world. Crossway, the holder of the copyright to the ESV Bible text, grants permission to include the ESV quotations within this work, in English. In addition, TGC gives you permission to faithfully translate the work into any other language, but you may not translate the English ESV Bible into another language. If you wish to include Bible quotations with the translated work, you will need to obtain permission from a publisher of a Bible translation in the same language. All scripture quotations are taken from the ESV® Bible (the Holy Bible, English Standard Version®) copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. ESV Text Edition: 2016. All rights reserved. The ESV text may not be quoted in any publication made available to the public by a Creative Commons license. The ESV may not be translated into any other language. The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®, is adapted from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A.

Naomi Widowed

1:1 In the days when the judges ruled there was a famine in the land, and a man of Bethlehem in Judah went to sojourn in the country of Moab, he and his wife and his two sons. 2 The name of the man was Elimelech and the name of his wife Naomi, and the names of his two sons were Mahlon and Chilion. They were Ephrathites from Bethlehem in Judah. They went into the country of Moab and remained there. 3 But Elimelech, the husband of Naomi, died, and she was left with her two sons. 4 These took Moabite wives; the name of the one was Orpah and the name of the other Ruth. They lived there about ten years, 5 and both Mahlon and Chilion died, so that the woman was left without her two sons and her husband.

Ruth’s Loyalty to Naomi

6 Then she arose with her daughters-in-law to return from the country of Moab, for she had heard in the fields of Moab that the LORD had visited his people and given them food. 7 So she set out from the place where she was with her two daughters-in-law, and they went on the way to return to the land of Judah. 8 But Naomi said to her two daughters-in-law, “Go, return each of you to her mother’s house. May the LORD deal kindly with you, as you have dealt with the dead and with me. 9 The LORD grant that you may find rest, each of you in the house of her husband!” Then she kissed them, and they lifted up their voices and wept. 10 And they said to her, “No, we will return with you to your people.” 11 But Naomi said, “Turn back, my daughters; why will you go with me? Have I yet sons in my womb that they may become your husbands? 12 Turn back, my daughters; go your way, for I am too old to have a husband. If I should say I have hope, even if I should have a husband this night and should bear sons, 13 would you therefore wait till they were grown? Would you therefore refrain from marrying? No, my daughters, for it is exceedingly bitter to me for your sake that the hand of the LORD has gone out against me.” 14 Then they lifted up their voices and wept again. And Orpah kissed her mother-in-law, but Ruth clung to her.

15 And she said, “See, your sister-in-law has gone back to her people and to her gods; return after your sister-in-law.” 16 But Ruth said, “Do not urge me to leave you or to return from following you. For where you go I will go, and where you lodge I will lodge. Your people shall be my people, and your God my God. 17 Where you die I will die, and there will I be buried. May the LORD do so to me and more also if anything but death parts me from you.” 18 And when Naomi saw that she was determined to go with her, she said no more.

Naomi and Ruth Return

19 So the two of them went on until they came to Bethlehem. And when they came to Bethlehem, the whole town was stirred because of them. And the women said, “Is this Naomi?” 20 She said to them, “Do not call me Naomi; 1 call me Mara, 2 for the Almighty has dealt very bitterly with me. 21 I went away full, and the LORD has brought me back empty. Why call me Naomi, when the LORD has testified against me and the Almighty has brought calamity upon me?”

22 So Naomi returned, and Ruth the Moabite her daughter-in-law with her, who returned from the country of Moab. And they came to Bethlehem at the beginning of barley harvest.

[1] 1:20 Naomi means pleasant [2] 1:20 Mara means bitter

Your browser does not support JavaScript. Please note, our website requires JavaScript to be supported.

Please contact us or click here to learn more about how to enable JavaScript on your browser.

- Change Country

- Resources /

- Insights on the Bible /

- The Historical Books

Listen to Chuck Swindoll’s overview of Ruth in his audio message from the Classic series God’s Masterwork .

Who wrote the book?

According to the Talmud (Jewish tradition), the prophet Samuel wrote the book of Ruth. The text itself says nothing of the author, but whoever wrote it was a skilled storyteller. It has been called the most beautiful short story ever written.

The final words of the book link Ruth with her great-grandson, David (Ruth 4:17–22), so we know it was written after his anointing. The genealogy at the end of the book shows David’s lineage through the days of the judges, acting as a support for his rightful kingship. Solomon is not mentioned, leading some to believe the book was written before David ascended the throne.

Where are we?

The events of Ruth occurred sometime between 1160 BC and 1100 BC, during the latter period of the judges (Ruth 1:1). These were dark days, full of suffering brought about by the Israelites’ apostasy and immorality. Part of the judgments God brought upon His sinful people included famine and war. The book of Ruth opens with a report of famine, which drove Naomi’s family out of Bethlehem into neighboring Moab. Naomi eventually returned with Ruth because she heard “that the LORD had visited His people in giving them food” (1:6).

Readers can identify this interlude as part of the cyclical pattern of sin, suffering, supplication, and salvation found in Judges. But this story stands as a ray of light, showing the power of the love between God and His faithful people. The author gave the reader a snapshot perspective—one family, in a small town, at the threshing floor—as opposed to the broader narratives found in Judges.

Why is Ruth so important?

The book was written from Naomi’s point of view. Every event related back to her: her husband’s and sons’ deaths, her daughters-in-law, her return to Bethlehem, her God, her relative, Boaz, her land to sell, and her progeny. Almost without peer in Scripture, this story views “God through the eyes of a woman.” 1

Naomi has been compared to a female Job. She lost everything: home, husband, and sons—and even more than Job did—her livelihood. She joined the ranks of Israel’s lowest members: the poor and the widowed. She cried out in her grief and neglected to see the gift that God placed in her path—Ruth.

Ruth herself embodied loyal love. Her moving vow of loyalty (Ruth 1:16–17), though obviously not marital in nature, is often included in modern wedding ceremonies to communicate the depths of devotion to which the new couples aspire. The book reveals the extent of God’s grace—He accepted Ruth into His chosen people and honored her with a role in continuing the family line into which His appointed king, David, and later His Son, Jesus, would be born (Matthew 1:1, 5).

What's the big idea?

Obedience in everyday life pleases God. When we reflect His character through our interactions with others, we bring glory to Him. Ruth’s sacrifice and hard work to provide for Naomi reflected God’s love. Boaz’s loyalty to his kinsman, Naomi’s husband, reflected God’s faithfulness. Naomi’s plan for Ruth’s future reflected selfless love.

The book of Ruth showed the Israelites the blessings that obedience could bring. It showed them the loving, faithful nature of their God. This book demonstrates that God responds to His people’s cry. He practices what He preaches, so to speak. Watching Him provide for Naomi and Ruth, two widows with little prospects for a future, we learn that He cares for the outcasts of society just as He asks us to do (Jeremiah 22:16; James 1:27).

How do I apply this?

The book of Ruth came along at a time of irresponsible living in Israel’s history and appropriately called the people back to a greater responsibility and faithfulness before God—even in difficult times. This call applies just as clearly to us today.

We belong to a loving, faithful, and powerful God who has never failed to care and provide for His children. Like Ruth and Boaz, we are called to respond to that divine grace in faithful obedience, in spite of the godless culture in which we live. Are you willing?

- Carolyn Custis James, The Gospel of Ruth: Loving God Enough to Break the Rules (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008), 28.

Copyright ©️ 2009 by Charles R. Swindoll, Inc. All rights reserved worldwide.

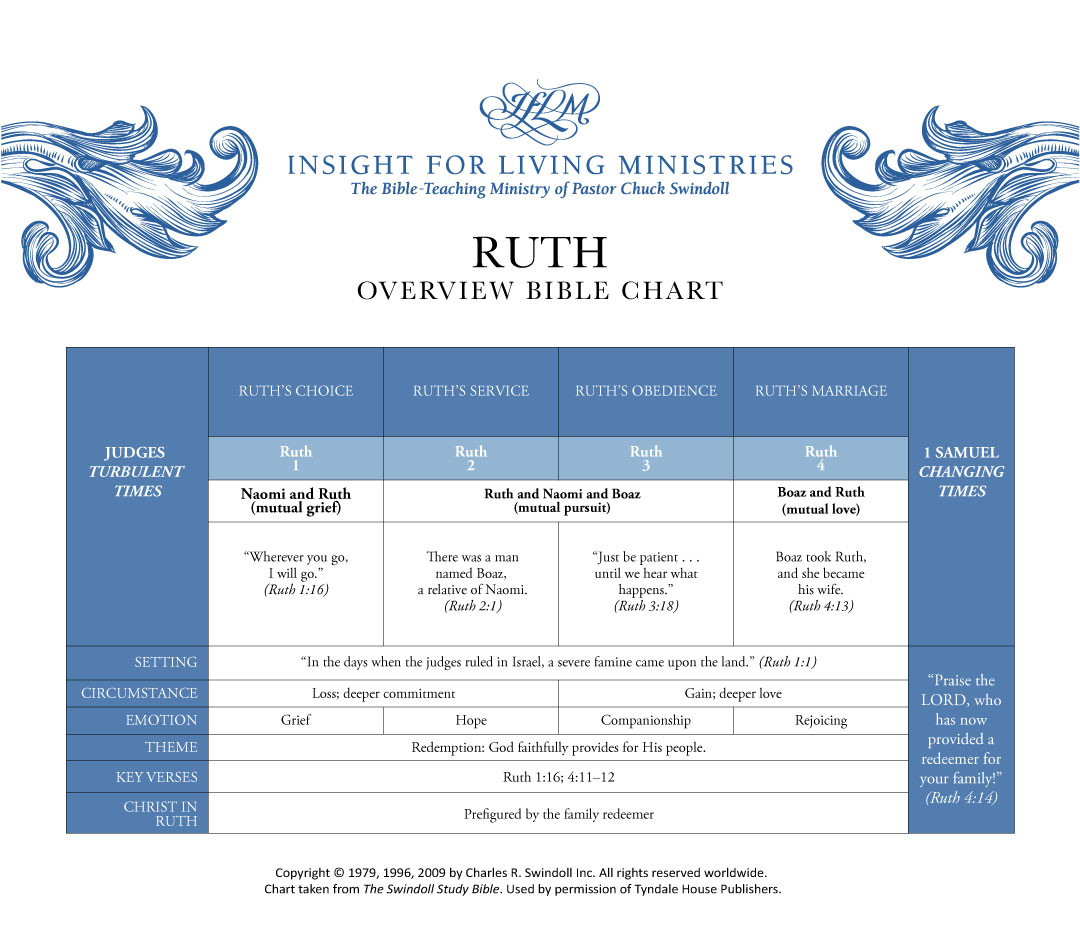

Bible Study Chart

Ruth overview chart.

View Chuck Swindoll's chart of Ruth , which divides the book into major sections and highlights themes and key verses.

View a list of Bible maps , excerpted from The Swindoll Study Bible.

The Book of Ruth reminds us to take seriously the lives of ordinary people

Though the media tells us that trust in institutions is at an all-time low and that increasing numbers of people think only of themselves rather than the common good, the biblical story of Ruth tells quite a different tale. Two vulnerable women place extraordinary trust in each other, treat their townspeople with decency and in return are treated respectfully, play a major role in their village, and contribute to the welfare of the nation. Without their being aware of it, the women perform a small-scale version of the Exodus, the great deed that brought Israel into existence centuries before. The scribal author, like other scribes, preferred a story to a sermon, confident that watching these two women act will make readers appreciate the communal importance of trust and respect for others.

In the biblical story of Ruth, two women make their way toward the village of Bethlehem five miles south of Jerusalem, the hometown of King David. Both women are widows. Naomi is perhaps in her late 40s and Ruth her late 20s. Both are also orphans—more accurately fatherless—lacking the support of a nearby family. Ten years earlier, severe famine forced Naomi’s family to leave Israel for Moab, west of the Dead Sea. During the course of their stay, Naomi’s two sons married Moabite women, Orpah and Ruth. Misfortune fell heavily on the family there, however: Death took Naomi’s husband Elimelech and her two sons.

Hearing that the Lord had brought prosperity back to her homeland, Naomi decided to return. She bade farewell to her daughters-in-law, addressing what was foremost in their minds: “May the Lord guide you to find a husband and a home [In Hebrew, mĕnȗḥāh ] . Have I other sons in my womb who could become your husbands?” Orpah returned to her family in Moab, but Ruth declared she would never leave her mother-in-law:

Wherever you go I will go, wherever you lodge I will lodge. Your people shall be my people and your God, my God. Where you die I will die, and there be buried. May the Lord do thus to me, and more, if even death separates me from you!