Argument: How Deep Does Corruption Run in Ukraine?

Create an FP account to save articles to read later and in the FP mobile app.

ALREADY AN FP SUBSCRIBER? LOGIN

World Brief

- Editors’ Picks

- Africa Brief

China Brief

- Latin America Brief

South Asia Brief

Situation report.

- Flash Points

- War in Ukraine

- Israel and Hamas

- U.S.-China competition

- Biden's foreign policy

- Trade and economics

- Artificial intelligence

- Asia & the Pacific

- Middle East & Africa

The Return of Great Powers

Ones and tooze, foreign policy live.

Winter 2024 Issue

Print Archive

FP Analytics

- In-depth Special Reports

- Issue Briefs

- Power Maps and Interactive Microsites

- FP Simulations & PeaceGames

- Graphics Database

Her Power 2024

The atlantic & pacific forum, principles of humanity under pressure, fp global health forum 2024, fp @ unga79.

By submitting your email, you agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use and to receive email correspondence from us. You may opt out at any time.

Your guide to the most important world stories of the day

Essential analysis of the stories shaping geopolitics on the continent

The latest news, analysis, and data from the country each week

Weekly update on what’s driving U.S. national security policy

Evening roundup with our editors’ favorite stories of the day

One-stop digest of politics, economics, and culture

Weekly update on developments in India and its neighbors

A curated selection of our very best long reads

How Deep Does Corruption Run in Ukraine?

Ukraine has made significant progress fighting graft, but its record continues to haunt it..

During a recent off-the-record think tank discussion on Ukraine, a respected journalist raised the issue of the damaging effects that Ukraine’s ongoing corruption issues have had on U.S. congressional Republican support for the country as it resists Russia’s invasion. The journalist’s comment, of course, was not the first about what has become a bugbear for Ukraine’s friends and enemies alike. Indeed, corruption in Ukraine’s economy, and more recently within its military structures, is a problem that needs to be addressed forcefully and forthrightly by Ukraine’s leaders.

But context and nuance about Ukrainian corruption are also crucial. After all, support for Ukraine’s heroic resistance to Russia’s brutal invasion is a strategic and moral imperative. How, then, should Ukraine’s corruption problems be understood?

First, it’s necessary to be precise about the scale of the problem. Because corruption is hidden, estimating its scale is always problematic. According to the most widely cited source—the annual ranking of corruption by Transparency International (TI)—Ukraine has scored poorly for decades. As late as 2016, amid major anti-corruption reforms, TI’s survey still judged Ukraine to be as corrupt as Russia. The most recent TI index suggests that Ukraine has made some strides since then, but it still ranks 104th among 180 countries. Denmark is ranked first—meaning that it is perceived as cleanest—while Russia ranks 141st.

TI’s ranking—called the Corruption Perceptions Index—does not measure actual corruption, but rather the perception of corruption based on international studies, public opinion polls, and responses from businesspeople and experts. Such sources are subjective by definition. What’s more, perceptions can be significantly influenced by the level of corruption-related information and debate, including public awareness campaigns, extensive investigative reporting, media discussion of corrupt practices, and comments by public figures.

In Ukraine’s case, Western governments, the European Union, and international agencies such as the World Bank have often highlighted the fight against corruption as a top priority, and their aid programs have invested heavily in anti-corruption nongovernmental organizations, public awareness campaigns, and promotion of transparent governance. These efforts helped to produce, for example, one of the world’s most stringent requirements for the declaration of income and assets by civil servants, legislators, and government officials. But such a persistent focus on corruption also heightens the perception that it is widespread—and it takes a while for that perception to turn around.

While Ukraine still carries an international reputation for endemic corruption, it has made major strides in the past decade. A 2018 report by the Kyiv-based Institute for Economic Research and Policy Consulting (IER), refereed by leading Western experts, documented four years of major anti-corruption reforms in the aftermath of the 2013-2014 Maidan protests, which ousted uber-corrupt President Viktor Yanukovych.

The reforms, including transparent government procurement and the deregulation of the notoriously corrupt energy sector, were estimated to have reduced grand corruption—a category that excludes petty corruption, such as police bribes—by a total of approximately $6 billion, or some 6 percent of Ukraine’s official GDP. Reforms of the state tax and revenue authorities also pared the size of the shadow economy, which dropped from an estimated 43 percent of GDP in 2014 to 33 percent in late 2017.

With few exceptions—such as the reintroduction of fixed gas prices to protect consumers during wartime—the reforms introduced during the administration of former President Petro Poroshenko were retained and expanded under current President Volodymyr Zelensky.

Before the reforms, Ukraine’s notoriously corrupt gas market alone had sucked billions of dollars in shady profits out of the state treasury. In the years before the all-out war, gas sector reforms added approximately $3 billion to the state budget. And these efforts are ongoing: Last year, Ukrainian authorities opened a criminal case against Dmytro Firtash, an oligarch also wanted in the United States for corruption, alleging that his group embezzled $484 million from the Ukrainian state treasury in a scheme involving gas transit fees.

Tax administration reforms and an enforcement crackdown have eliminated tax losses amounting to at least $1 billion per year. The reforms included electronic filing for value-added tax, which helped curb graft. Investigators exposed and eliminated a widespread network of corrupt tax evasion—established under Yanukovych—that diverted cash to tax inspectors, who accepted falsified income and expense records in return for 6 to 12 percent of the evaded taxes.

Another landmark anti-corruption reform came in 2016, when Ukraine unveiled a transparent electronic system for public procurement, ProZorro , which has drastically reduced corruption in bidding for government contracts. Funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the system has saved Ukraine almost $6 billion in public procurement costs since 2017, according to a 2021 U.S. government report. The system has been promoted by Transparency International and was recently recognized by the World Bank.

Other open-data reforms eliminated many rent-seeking schemes and lowered procurement costs from ongoing contracts by a further $700 million. Since the 2022 Russian invasion, procurement related to national security is now conducted in secret, but ProZorro continues to operate for other bidding.

In all, IER calculates that anti-corruption reforms eliminated nearly $4 billion a year in formerly misappropriated revenues. The number is conservative, since it does not include related efforts to clean up Ukraine’s economy, such as banking reforms that eliminated so-called zombie banks that had misappropriated citizens’ savings and other assets to bank managers and owners.

In addition, Ukraine seized $1.5 billion in suspicious assets controlled by what Ukraine’s prosecutor general called an “organized crime group led by Yanukovych” and returned the assets to the state treasury. Ukrainian authorities also temporarily nationalized the banking assets of oligarch Ihor Kolomoysky and began the legal process to restore more than $5 billion that PrivatBank, the bank he co-owned and controlled , is alleged to have stolen through fraudulent loans to foreign shell companies and accounts.

The wave of anti-corruption reforms that began with Yanukovych’s ouster in 2014 continued when Zelensky came into office in 2019. That fall, the new High Anti-Corruption Court launched its first cases; by late 2023, it had convicted 157 government officials and other perpetrators. Since the 2022 invasion, Zelensky’s government has also stepped up asset seizures from companies and individuals in business that had been working with Russia and financing pro-Russian media and political parties in Ukraine. In September 2023, Ukrainian authorities arrested Kolomoysky on a wide range of criminal charges, including forgery and major fraud.

There is no question that Ukraine has made great strides combating corruption, with 11 consecutive years of improving its ranking in the TI Corruption Perception Index.

This leads us to the most recent arena of corruption—and, in the context of Ukraine’s need for Western support, the most sensitive one: the defense and national security sector. Since the start of the full-scale Russian invasion, scandals related to the military have included price gouging on foodstuffs for the armed forces, overpriced (and possibly flimsy) winter gear, and an unfulfilled contract for mortar shells. All of these are serious and deserve prosecution, especially when they carry a cost in lives in the ongoing war.

It’s important, however, to set the scale of these cases in relation to the war. The abuses involved amount to millions or tens of millions of dollars—and while these are large numbers, they are an exceedingly miniscule percentage of Ukraine’s vast military expenditures. Since Russia’s invasion, Ukraine has increased its military budget from $6 billion in 2021 to $35 billion in 2023 and up to $42 billion this year. Together with foreign security assistance, its total military resources have climbed to roughly $75 to $80 billion annually.

This scaling up occurred amid a blistering multifront Russian attack. In short, Ukraine’s military spending grew exponentially to something approaching half of its 2022 GDP—all while its officials scrambled to purchase, arm, equip, and integrate a rapidly expanding force; had to find ways to replace fast-depleting Soviet-era munitions; and faced massive Russian attacks on the country’s defense industry. All the while, Russia was snatching up as many of Soviet era munitions as it could find on the international arms market in order to deny Ukraine access. In this context, Ukraine turned to various domestic and international middlemen, some of whom were not properly vetted.

Even as it was hunting globally for stores of Soviet-era munitions and weapons, Ukraine also gave priority to systems that would ensure that Western weapons did not become part of corrupt schemes that could threaten Western support. Given the urgency of moving weapons to the front, it is hardly surprising that in January, the Pentagon’s inspector general found that some $1 billion of U.S.-supplied weapons had not been properly tracked. At the same time, however, Pentagon spokesperson Maj. Gen. Patrick Ryder said that there was “no credible evidence of illicit diversion of U.S.-provided, advanced conventional weapons from Ukraine.”

Nevertheless, with so much cash and equipment in play—and a multiplicity of vendors, contractors, and subcontractors involved—there will likely be some instances of fraud, corruption, or incompetence. Such cases should be measured against the scale and complexity of aid. The fact that no evidence of significant abuses of Western military aid has emerged over the past two years—despite systematic efforts by the Kremlin and its sympathizers in the West to discredit Ukraine—is itself an encouraging sign.

Finally, there is the question of the standard to which Ukraine is being held. In his famous 1982 article in Commentary , “Why We Need More,” the strategic analyst Edward Luttwak highlighted inefficient spending, botched contracts, and failed weapons systems in the U.S. defense budget. His point was that the Reagan administration’s dramatic increase in military spending would necessarily come with substantial inefficiency. Moreover, Luttwak argued that the main objective of the defense establishment should be wise strategy, better operational methods, and more ingenious tactics—all areas in which Ukraine’s military and defense officials have thus far excelled. Luttwak asserted that if the price for strategic, operational, and tactical success is the neglect of “micro-management,” then a little more “waste, fraud, and mismanagement” in the Pentagon would be a reasonable price to pay.

No one wishes to see corruption or mismanagement of public resources, but Luttwak’s point is that whenever there are massive and rapid government spending increases, there will inevitably be failures in the systems that monitor them, no matter the country. Compared to the United States in peacetime, this point is even more relevant in Ukraine, which in a single year saw a more than 1,000 percent increase in its military resources in the middle of an unprovoked invasion by a powerful enemy.

As Ukraine’s war against Russia proceeds, policymakers and the public should expect further corruption scandals. These must be addressed, and their perpetrators punished, but they must also be seen in the proper context. Occasional lurid headlines notwithstanding, Ukraine has made major progress in tackling grand corruption, reducing the power of oligarchs, and managing a vast increase in defense spending without scandals on a massive scale. That in itself is testament to how much has changed in Ukraine since a decade ago.

Shining a light on corruption while being honest about its scale is not merely a matter of accuracy—it is a matter of Ukraine’s survival.

Adrian Karatnycky is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, the founder of Myrmidon Group, and the author of Battleground Ukraine: From Independence to the War with Russia , to be published by Yale University Press in June 2024.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber? Log In .

Subscribe Subscribe

View Comments

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Not your account? Log out

Please follow our comment guidelines , stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username:

I agree to abide by FP’s comment guidelines . (Required)

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.

What a Russian Victory Would Mean for Ukraine

Ukrainians would face terror on a scale not seen in Europe since the 20th-century era of totalitarian rule.

The West Can No Longer Hesitate on Ukraine

Allies must provide Kyiv with what it needs to win the war and secure the peace: arms supplies and a path to NATO membership.

NATO’s Confusion Over the Russia Threat

Scenarios and timelines for Moscow’s possible war goals in Europe are a veritable Tetris game of alliance planning.

Sign up for Editors' Picks

A curated selection of fp’s must-read stories..

You’re on the list! More ways to stay updated on global news:

Turkey’s Opposition Wins ‘Historic Victory’ in Local Elections

Israel escalates shadow war against iran, migrants in russia are terrified as racism grows after deadly attack, ‘everything, everywhere, all at once’: u.s. officials warn of increased cyberthreats, will vietnam’s political turmoil shake up foreign investment, editors’ picks.

- 1 ‘Everything, Everywhere, All At Once’: U.S. Officials Warn of Increased Cyberthreats

- 2 Turkey’s Opposition Wins ‘Historic Victory’ in Local Elections

- 3 NATO Is Unprepared for Russia’s Arctic Threats

- 4 Why Biden Can’t Force a Truce on Israel—or Won’t

- 5 America Must Act to Prevent a Rwanda-Congo War

- 6 Why Lula Is Silent on Haiti

Turkey Local Election Results: Erdogan's AKP Loses to Opposition CHP in Istanbul, Ankara

Israel strikes iran consulate in syria, kills irgc commander, putin is using moscow terrorist attack to target ukrainians and migrants, china, russia, and iran pose growing cyberthreats to u.s. infrastructure, vietnam: will president's resignation affect foreign investment, more from foreign policy, is this a revolution or are people just very ticked off.

In a new book, Fareed Zakaria explores how much the times are a-changin’. At risk, he says, is the entire global system.

Egypt Is What Happens When the U.S. Gives Up on Democratization

Civil society loses—and China and Russia fill the vacuum.

Russia Is Back to the Stalinist Future

With a Soviet-style election, Vladimir Putin’s Russia has come full circle.

Why Biden Can’t Force a Truce on Israel—or Won’t

The United States has intervened in past Mideast wars, but this one is different.

Why Lula Is Silent on Haiti

America must act to prevent a rwanda-congo war, power is the answer in u.s. competition with china.

Sign up for World Brief

FP’s flagship evening newsletter guiding you through the most important world stories of the day, written by Alexandra Sharp . Delivered weekdays.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Corruption concerns involving Ukraine are revived as the war with Russia drags on

The Associated Press

In this photo provided by the Ukrainian Presidential Press Office on July 8, 2022, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, attends a meeting with military officials during his visit the war-hit Dnipropetrovsk region. Ukrainian Presidential Press Office via AP hide caption

In this photo provided by the Ukrainian Presidential Press Office on July 8, 2022, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, attends a meeting with military officials during his visit the war-hit Dnipropetrovsk region.

WASHINGTON (AP) — Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy's dismissal of senior officials is casting an inconvenient light on an issue that the Biden administration has largely ignored since the outbreak of war with Russia: Ukraine's history of rampant corruption and shaky governance.

As it presses ahead with providing tens of billions of dollars in military, economic and direct financial support aid to Ukraine and encourages its allies to do the same, the Biden administration is now once again grappling with longstanding worries about Ukraine's suitability as a recipient of massive infusions of American aid.

Those issues, which date back decades and were not an insignificant part of former President Donald Trump's first impeachment, had been largely pushed to the back burner in the immediate run-up to Russia's invasion and during the first months of the conflict as the U.S. and its partners rallied to Ukraine's defense.

But Zelenskyy's weekend firings of his top prosecutor, intelligence chief and other senior officials have resurfaced those concerns and may have inadvertently given fresh attention to allegations of high-level corruption in Kyiv made by one outspoken U.S. lawmaker.

It's a delicate issue for the Biden administration. With billions in aid flowing to Ukraine, the White House continues to make the case for supporting Zelenskyy's government to an American public increasingly focused on domestic issues like high gas prices and inflation. High-profile supporters of Ukraine in both parties also want to avoid a backlash that could make it more difficult to pass future aid packages.

U.S. officials are quick to say that Zelenskyy is well within his right to appoint whomever he wants to senior positions, including the prosecutor general, and remove anyone who he sees as collaborating with Russia.

Yet even as Russian troops were massing near the Ukrainian border last fall, the Biden administration was pushing Zelenskyy to do more to act on corruption — a perennial U.S. demand going back to Ukraine's early days of independence.

"In all of our relationships, and including in this relationship, we invest not in personalities; we invest in institutions, and, of course, President Zelenskyy has spoken to his rationale for making these personnel shifts," State Department spokesman Ned Price told reporters on Monday.

Price declined to comment further on Zelenskyy's reasoning for the dismissals or address the specifics but said there was no question that Russia has been trying to interfere in Ukraine.

"Moscow has long sought to subvert, to destabilize the Ukrainian government," Price said. "Ever since Ukraine chose the path of democracy and a Western orientation this has been something that Moscow has sought to subvert."

Still, in October and then again in December 2021, as the U.S. and others were warning of the increasing potential for a Russian invasion, the Biden administration was calling out Zelenskyy's government for inaction on corruption that had little or nothing to do with Russia.

"The EU and the US are greatly disappointed by unexplained and unjustifiable delays in the selection of the Head of the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor Office, a crucial body in the fight against high-level corruption," the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv said on Oct. 9.

"We urge the selection commission to resume its work without further delays. Failure to move forward in the selection process undermines the work of anti-corruption agencies, established by Ukraine and its international partners," it said. That special prosecutor was finally chosen in late December but was never actually appointed to the position. Although there are indications the appointment will happen soon, the dismissal of the prosecutor general could complicate the matter.

The administration and high-profile lawmakers have avoided public criticism of Ukraine since Russia invaded in February. The U.S. has ramped up the weapons and intelligence it's providing to Ukraine despite early concerns about Russia's penetration of the Ukrainian government and existing concerns about corruption.

A Ukrainian-born congresswoman who came to prominence early in the war recently broke that unofficial silence.

Rep. Victoria Spartz, a first-term Republican from Indiana, has made half a dozen visits to Ukraine since the war began. And she was invited to the White House in May and received a pen used by President Joe Biden to sign an aid package for Ukraine even after she angrily criticized Biden for not doing more to help.

But in recent weeks, Spartz has accused Zelenskyy of "playing politics" and alleged his top aide Andriy Yermak had sabotaged Ukraine's defense against Russia.

She's also repeatedly called on Ukraine to name the anti-corruption prosecutor, blaming Yermak for the delay.

Ukrainian officials have hit back. A statement from Ukraine's Foreign Ministry accused Spartz of spreading "Russian propaganda" and warned her to "stop trying to earn extra political capital on baseless speculation."

U.S. officials gave Spartz a two-hour classified briefing on Friday in hopes of addressing her concerns and encouraging her to limit her public criticism. She declined to discuss the briefing afterward but told The Associated Press that "healthy dialogue and deliberation is good for Congress."

"We're not here to please people," she said. "It's good to deliberate."

Hours later, Spartz gave a Ukrainian-language interview broadcast on YouTube in which she called again for the appointment of an independent prosecutor.

"This issue should be resolved as soon as possible," she said in the interview. "This is a huge problem for the West, so I think your president should address this issue soon."

Rep. Jason Crow, a Colorado Democrat who sits on the House Armed Services and Intelligence committees, said he had seen no evidence to support allegations that Zelenskyy's inner circle was trying to help Russia. But as the war continues, part of the long-term American strategy in Ukraine will have to include addressing waste and mismanagement of resources, he said.

"There is no war in the history of the world that is immune from corruption and people trying to take advantage of it," Crow said. "If there are concerns raised, we will address them."

Igor Novikov, a Kyiv-based former adviser to Zelenskyy, called many of Spartz's claims a mix of "hearsay and urban legends and myths." Allegations against Yermak in particular have circulated for years going back to his interactions with Trump allies who sought derogatory information against Biden's son Hunter.

"Given that we're in a state of war, we need to give President Zelenskyy and his team the benefit of the doubt," Novikov said. "Until we win this war, we have to trust the president who stayed and fought with the people."

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Limited time offer save up to 40% on standard digital.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital.

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- Videos & Podcasts

- FT App on Android & iOS

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Premium newsletters

- Weekday Print Edition

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Everything in Print

- Everything in Premium Digital

The new FT Digital Edition: today’s FT, cover to cover on any device. This subscription does not include access to ft.com or the FT App.

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

Ukraine recap: Zelensky battles corruption and a major row with his commander-in -chief

Senior International Affairs Editor, Associate Editor

View all partners

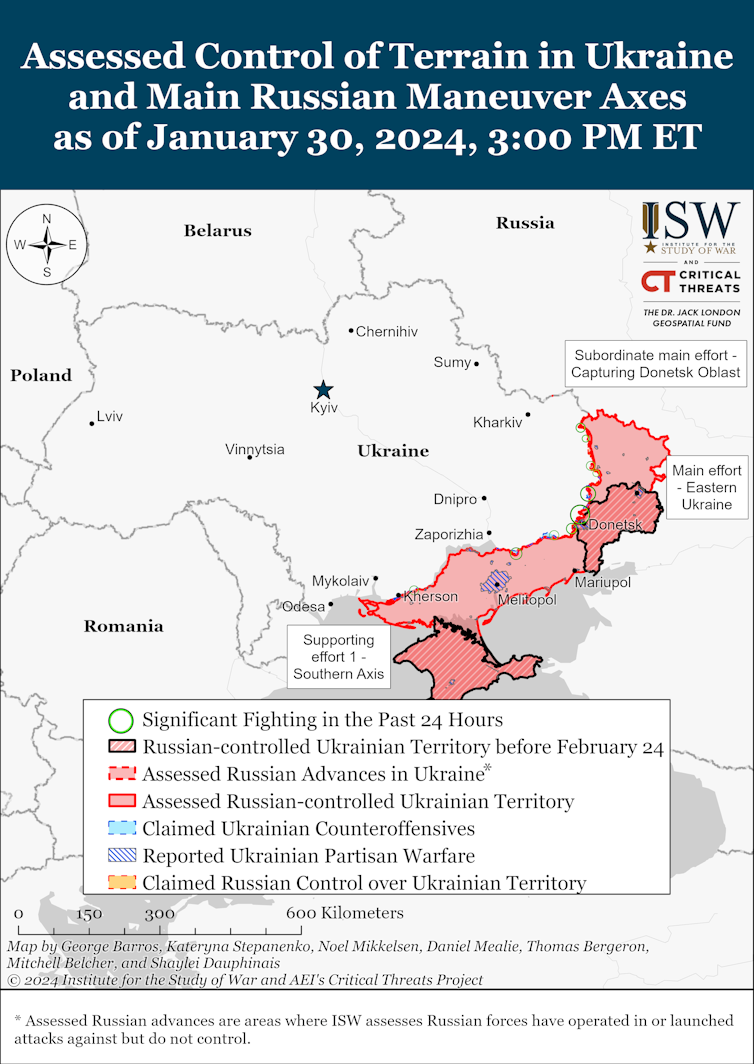

The Russian winter offensive flagged here a fortnight ago appears to be under way, according to the Institute for the Study of War, which has noted operations in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts resulting in small Russian gains of territory. Ukrainian intelligence reports that the aim is to push towards Kharkiv while occupying the whole administrative areas of Donetsk and Luhansk.

But the feeling is that Russia is unlikely to be able to fulfil this ambition. Lieutenant General Kyrylo Budanov, the head of Ukraine’s military intelligence, or GUR, said he expected Russian forces would be “completely exhausted” by spring. As ever, the key will be whether Ukraine can obtain enough ammunition to survive until then. According to a recent report by Bloomberg, the EU is expected to deliver only just over half the 1 million shells it has promised Ukraine by March 1.

Meanwhile, both the EU and US have been struggling to get their aid packages agreed – although it has been reported that Hungarian president Viktor Orbán has bowed to pressure from other EU members and agreed not to obstruct their €50 billion (£42.7 billion) military aid package. But this leaves the US president, Joe Biden, trying to find ways to convince recalcitrant Republican senators to fall into line over his plans to provide Ukraine with US$60 billion (£47.3 billion) of military aid.

It has been reported that Biden has managed to circumvent the senate by giving Greece a large cache of older surplus weapons, with the understanding that Greece then passes on its own surplus weaponry to Ukraine – a variation of what is known as Germany’s Ringtausch (ring transfer) programme, by which it supplied tanks to Ukraine via Slovakia, circumventing its own security policy.

But it’s widely hoped that Biden will be able to bring the senate round to his way of thinking. One possible snag is the military corruption scandal that has broken round Volodymyr Zelensky’s ears in recent days.

The Ukrainian president came to power in 2019 on a platform of rooting out corruption and fraud in one of Europe’s most corrupt countries. That this latest episode concerns senior defence officials and managers of an arms supplier allegedly colluding to pocket £31 million that was meant to buy artillery shells will not make it any easier for Biden to persuade sceptical senators to fall into line, write Stefan Wolff and Tetyana Malyarenko .

Wolff, an expert in international security at the University of Birmingham, and Malyarenko, from the University of Odesa, also highlight a rift between Zelensky and his military commander, General Valeriy Zaluzhny, which has developed since November when Zaluzhny said publicly the war was in a stalemate. None of this will give Kyiv’s western allies a great deal of confidence about the future of their investment.

Read more: Ukraine war: corruption scandals and high-level rifts could become an existential threat as Kyiv asks for more military aid

Since Vladimir Putin sent his war machine into Ukraine on February 24 2022, The Conversation has called upon some of the leading experts in international security, geopolitics and military tactics to help our readers understand the big issues . You can also subscribe to our fortnightly recap of expert analysis of the conflict in Ukraine.

Ukrainians remain committed to beating Russia, although polling taken in November 2023 revealed that an increasing number would be willing to accept a negotiated deal to end the fighting, which would inevitably involve the loss of territory to Russia.

Gerard Toal, professor of government and international affairs at Virginia Tech, believes this resolve may be tested once the next round of recruitment, which aims to add as many as 500,000 fresh troops to Ukraine’s armed forces in the field, gets under way.

Read more: What latest polling says about the mood in Ukraine – and the desire to remain optimistic amid the suffering

Meanwhile Elis Vilasi, who lectures in national security and foreign affairs at the University of Tennessee, warns against any peace deal which would involve Russia gaining territory. He points to Serbia, which – more than two decades on from the settlement of hostilities in the Balkans – continues to attempt to destabilise the region.

Read more: A Western-imposed peace deal in Ukraine risks feeding Russia's hunger for land – as it did with Serbia

Beating the drum for war

Increasingly common media coverage in the UK pointing to the likelihood of a major war in Europe has encouraged some commentators and military types to consider the precipitous decline in the UK’s troop numbers, which are forecast to fall below 70,000 within two years.

Mark Lacy, a philosopher at Lancaster University, notes a new recruitment video for the British army which uses a Fortnite-style computer game to target more tech-savvy young people. The nature of war is changing, Lacy believes, so strong tech skills will inevitably be part of most future soldiers’ armoury.

Read more: New Fortnite-style recruitment video shows how UK armed forces are getting serious about prospects of Nato war with Russia

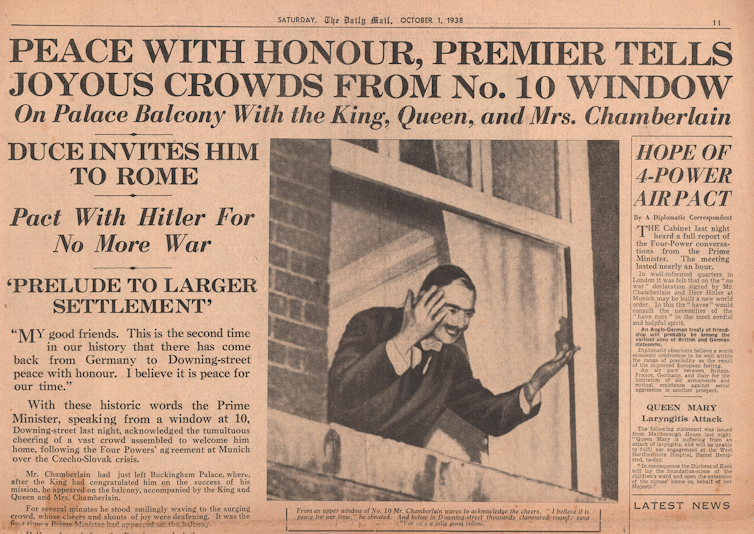

All this talk of a major impending European – even world – war bears comparison to the years in the lead-up to the second world war. History tells us that most people in Britain realised by the late 1930s that a fresh conflict with Germany was inevitable.

Tim Luckhurst, who researches newspaper history at Durham University, has had a trawl through some of the coverage from 1938 when the then-prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, flew to Munich for talks with Adolf Hitler and came back with a “piece of paper” promising “peace in our time”. Liberal and left-leaning papers such as the Daily Mirror and The Guardian decried Chamberlain’s deal for abandoning Czechoslovakia (and of course, with hindsight, we know how disastrous a decision it turned out to be).

The more conservative press, including the Times and the Daily Mail, were four-square behind Chamberlain. The Mail, which in its chequered past featured headlines such as “Hurrah for the Blackshirts” in praise of homegrown fascist Oswald Mosley, appeared to be particularly convinced of Hitler’s bona fides.

Read more: UK press warns of Nato war with Russia – newspapers are clearly keen to avoid mistakes of WWII

Meanwhile in Russia …

In his quest to ensure he retains control over the hearts and minds of as many Russian people as possible, Vladimir Putin has mandated a rewriting of school history textbooks. Among other things, the new books extol the memory of Comrade Joseph Stalin – who we know as a murderous tyrant, but who a new generation of Russians (and Ukrainians in occupied territories) now know to be a kindly old gentleman who did a good deal to make Russia the great nation that Putin aims to restore.

Anya Free, a scholar of Russian and Soviet history at Arizona State University, writes that this is part of a wider move to control memory in Russia , which also involves the creation of a network of “historical memory” centres across Russia and occupied Ukraine. Ukrainian students will, for example, get to read a collection of documents on the “historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians” – where they will find out that Comrade Putin was right all along about Ukraine being part of Russia.

Read more: Back in the USSR: New high school textbooks in Russia whitewash Stalin's terror as Putin wages war on historical memory

Of course, a new generation of patriotic young Russians will want to explore the wonders of their country, so Putin also plans to turn his country’s untamed and isolated far east into a new tourism hotspot.

Natasha Kuhrt, a Russia expert at King’s College London, says the region – which has hitherto been a massive centre for the production of energy and raw materials, much of which have been exported to China – will depend on domestic visitors and tourists from China. And there’s no disputing its natural beauty, including 23 national parks.

The problem, as Kuhrt notes , is that many Chinese visitors to Russia’s “wild east” in the past have engaged in large-scale hunting and poaching of wildlife. This would seem at odds with Putin’s plan to encourage development of the region as a centre for ecotourism.

Read more: Putin wants to transform Russia's far east into a tourist hotspot – but history shows it won't be easy

Ukraine Recap is available as a fortnightly email newsletter. Click here to get our recaps directly in your inbox.

- Vladimir Putin

- Viktor Orbán

- UK military

- Russian history

- Volodymyr Zelensky

- Ukraine invasion 2022

- Keep me on trend

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Initiative Tech Lead, Digital Products COE

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- TikTok’s fate

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

- World Politics

- Russia-Ukraine war

Ukraine’s corruption shake-up, briefly explained

Top officials are ousted or resign in the biggest reshuffle since the start of the Russian invasion.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Ukraine’s corruption shake-up, briefly explained

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/71902688/1246324930.0.jpg)

A corruption scandal is shaking up the Ukrainian government , with top officials stepping aside as Kyiv seems eager to assure Western partners of their responsible stewardship of billions in military and economic aid.

Among the high-profile exits are Kyrylo Tymoshenko, deputy head in the office of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, and a deputy in the ministry of defense, Vyacheslav Shapovalov , who was responsible for overseeing supplies and food for troops. A deputy prosecutor general was also fired, as were a handful of regional governors and a few other government ministers .

The actual details of what prompted the shake-up are a bit murky, and not all of the resignations and ousters appear to be related, but it comes after at least one report in Ukrainian media that the Ministry of Defense had purchased food for troops at extra-high prices. The Ministry of Defense had said the allegations were a deliberate attempt to mislead, but said it would conduct an internal audit. Additional media reports in the past week had questioned officials, including Tymoshenko, who appeared to be enjoying lavish lifestyles .

This represents the most high-profile reshuffle since Russia’s invasion last year. More details about the alleged graft are likely to emerge, but it seems clear that Zelenskyy’s government moved fast to tamp down any allegations of widespread corruption, especially from international backers who are providing tens of billions of dollars in assistance that Ukraine depends on in its fight against Russia. Some critics have also suggested the shake-up is more of a political move, rather than a genuine anti-corruption effort.

In his Tuesday evening address, posted on Telegram , Zelenskyy acknowledged the personnel shifts and said that any internal problems “that hinder the state are being cleaned up and will be cleaned up. It is fair, it is necessary for our defense, and it helps our rapprochement with European institutions.”

Ukraine has previously struggled to root out high-level corruption and bolster the rule of law , despite Zelenskyy promising to do so when he was elected in 2019 . Ukraine’s backers in the United States and Europe had long put pressure on Kyiv to deal with these issues, especially as a condition for Ukraine’s invitation into Western institutions, including perhaps one day joining the European Union . Russia’s full-scale attack last year shunted some of those corruption concerns aside, as Western governments rushed to back up Ukraine and as Ukraine itself became a global symbol for democratic resistance.

Within Ukraine, some civil society groups and anti-corruption forces who’d long been critical of the Ukrainian government and Zelenskyy put some of their activism on hold as Ukrainian society fully mobilized in the war effort. According to a report on war and corruption in Ukraine released last summer, about 84 percent of anti-corruption experts abandoned their activities because of the conflict.

Still, concerns about Ukraine’s approach to corruption never totally dissipated . The chaos of conflict — lots of rapid procurements, an influx of funds and supplies moving through many hands — tends to create fertile areas for potential graft and can exacerbate existing problems. This is true no matter where the war is or who’s doing the fighting . Ukraine is no exception.

What we know about the Ukrainian government shake-ups

The recent reshuffle appears to be connected to a few different scandals. Perhaps the most high-profile is this allegation, first reported in the Ukrainian media outlet ZN.UA , that the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense had signed a contract paying two to three times more for food than retail prices in Kyiv . Defense Minister Oleksiy Reznikov rejected the claims, saying it was a “technical error” and suggesting the leak was timed to a meeting of Western donors , in an effort to undermine Ukraine. “Information about the content of food service shoppers who have taken up public space is spreading with signs of deliberate manipulation and mislead,” the ministry said in a statement . The ministry said it was opening an investigation into the “spread of intentionally false information,” though it was also conducting an internal audit.

In response to the procurement allegations, the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU) publicly announced its own investigation. On Tuesday, Deputy Defense Minister Vyacheslav Shapovalov reportedly asked to be dismissed , so as “not to pose a threat to the stable supply of the Armed Forces of Ukraine as a result of a campaign of accusations related to the purchase of food services.”

But Ukraine’s government shake-up extends beyond that. On Tuesday, Tymoshenko , a close aide to Zelenskyy, announced his resignation, saying it was of his “own volition.” Tymoshenko had a fairly public-facing role during the war , and Ukrainian media had reported last year that he had driven an SUV donated for humanitarian purposes for his personal use (he denied that report). In December, another investigation suggested Tymoshenko had been driving an expensive sports car, and had rented a mansion belonging to a prominent businessman — flashy accessories for a government official in wartime. Tymoshenko has said he rents the house because his own is in an area targeted by airstrikes.

Oleksiy Symonenko, a deputy prosecutor general , was also ousted, following reports last month in Ukrainian media that he had gone on a 10-day holiday in Spain during the war . On Monday, Zelenskyy banned all government officials from leaving the country for anything other than official business.

In addition to these high-profile ousters, a few other deputy ministers and regional governors — including those in the Kyiv and Kherson regions — were also fired. According to the Kyiv Independent , some of these officials have been implicated in graft, while others appear to have just been caught up in the reshuffle.

This turmoil also comes days after Ukraine’s deputy infrastructure minister, Vasyl Lozinskyi, was fired following allegations from Ukrainian prosecutors that he stole $400,000 (£320,000) that was intended to go to the purchase of aid, including generators, to help Ukrainians withstand the winter after Russian attacks badly damaged energy infrastructure . He has not commented on the allegations.

Ukraine corruption is a focus again, a year into war

A few firings and resignations will not fix endemic corruption or rule of law problems in Ukraine, just as Ukraine’s resistance against Moscow will not erase all of its underlying governance weaknesses. A bigger question is how widespread these latest instances of corruption are, and whether the ousters and resignations now represent a real and sustained effort to crack down or are more a political reshuffle and a public show to reassure Western partners and the Ukrainian public.

An aid to Zelenskyy tweeted that the moves show the government won’t turn any “blind eyes” to misdeeds. Yet some critics have suggested this is more of a political shake-up, and that other politicians accused of corruption remain in their posts .

In 2021, Transparency International had ranked Ukraine 122 among 180 countries for corruption, making it one of the worst offenders. Even on the eve of Russia’s invasion, the United States and European partners had continued to put pressure on Zelenskyy to implement anti-corruption and rule of law reforms. Those calls didn’t stop once the war commenced , but the focus, with legitimate reason, was on supporting Ukraine’s resistance to Russia and providing military, humanitarian, and economic aid to Kyiv.

Within Ukraine, too, some of the government’s biggest critics redirected their energies to the larger war effort, according to a survey of 169 anti-corruption experts who responded in April 2022. Around 47 percent reported feeling endangered if they continued to fight corruption during the conflict.

This, of course, is why war and conflict can deepen corruption. Ukraine is fighting for its existence as a state, so, naturally, that’s the priority above all else. Government resources, attention, and funding all go to mobilizing for that, which means anti-corruption efforts and rule of law reforms fall by the wayside. On top of that, war creates plenty of opportunities for graft, with less time and attention on accountability and oversight.

The recent allegations come nearly one year into the war as the West once again gears up to send Ukraine massive tranches of weapons — including now, reportedly , advanced US tanks. The US alone has contributed about $100 billion toward Ukraine , including military, security, and economic assistance. As of November, European countries and EU institutions have pledged more than €51 billion in assistance to Ukraine , according to the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. As the war drags on, some Western lawmakers are questioning the amount of aid flowing to Ukraine — and are calling for more accountability on where everything is going. That includes some of the newly sworn-in Republican majority in the US House . Kyiv relies on foreign support in its fight against Russia, and repeated hints of misuse may jeopardize that, so it’s not surprising Kyiv is moving quickly to respond.

And that is perhaps one of the big questions: How much of this is for optics, and how much does this reflect a deeper commitment on those corruption promises? The US has lauded Ukraine for making these moves, but a lot will depend on how the investigations play out and what they uncover. Still, Ukraine’s efforts to signal a corruption crackdown to the world — and to a domestic audience who’s sacrificed a lot for the war — still carry a warning to other officials.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

At Vox, we believe that clarity is power, and that power shouldn’t only be available to those who can afford to pay. That’s why we keep our work free. Millions rely on Vox’s clear, high-quality journalism to understand the forces shaping today’s world. Support our mission and help keep Vox free for all by making a financial contribution to Vox today.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In World Politics

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Why is there so much lead in American food?

Multigenerational housing is coming back in a big way

You can’t afford to buy a house. Biden knows that.

Want a 32-hour workweek? Give workers more power.

The harrowing “Quiet on Set” allegations, explained

The chaplain who doesn’t believe in God

Of oligarchs and corruption: Ukraine faces its own demons

Subscribe to the center on the united states and europe update, jeremy shapiro and jeremy shapiro nonresident senior fellow - foreign policy , center on the united states and europe @jyshapiro hannah thoburn ht hannah thoburn senior research assistant and assistant blog editor.

March 24, 2015

While combat continues in Eastern Ukraine, a perhaps more important battle for the soul of Ukraine is playing out in the political corridors and the corporate boardrooms of Kyiv. Since independence, Ukraine has struggled continuously to break the iron triangle of oligarchic rule, corruption, and financial instability that has left Ukraine mired in poverty. It has made depressingly little progress. That struggle has entered a new phase and acquired a new momentum after the Maidan revolution, the Russian invasion of Crimea and Eastern Ukraine, and the formation of a new reform-minded government. But the old demons remain and the early signs are that victory in the new struggle may prove as elusive as in the old.

The new Ukrainian government is well aware of the challenges. Ukraine’s Finance Minister Natalie Jaresko came to Washington, D.C. last week to ask for support in helping her country in finding a solid financial footing. In a speech at Brookings , she laid out the young government’s challenges. Although it is at war, she said, “the war of creating a reformed market economy that is strong and capable and can lead Ukraine forward” is perhaps of larger importance.

The list of tasks Jaresko laid out was daunting. President Petro Poroshenko and his government must “stabilize the economy, reform the country, fight corruption, improve transparency and accountability, improve the rule of law, [and] create conditions for the return of economic growth and prosperity.” Ukraine’s government seems to recognize the urgency in making quick reforms that will have an impact on Ukrainians’ daily lives. Minister Jaresko spoke of the forthcoming roll-out of a new policing system, an increase in taxes for the very wealthy, eventual reduction in payroll taxes, and a simplified tax system.

But the difficulty of these tasks was brought into sharp relief this weekend, when the powerful oligarch Igor Kolomoiskiy took umbrage at the firing of one of his acolytes, Oleksander Lazorko, as head of the state-owned oil-pipeline operator UkrTransNafta. After Lazorko barricaded himself in the office and refused to leave, Kolomoiskiy appeared in central Kyiv with a small battalion of masked, armed men in tow.

This incident epitomizes what Jaresko called “the old ways of doing business in Ukraine.” Since Ukraine gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukraine’s economy has been held hostage to the desires of an elite, ruthless few. State-owned businesses are still key strategic assets in an internal struggle between oligarchs. And those oligarchs will not hesitate to resort to extralegal means to maintain their sources of income and their power.

Kolomoiskiy is a perfect example of the type. Although a one-time partisan of former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, he was appointed the governor of Ukraine’s east-central and heavily industrial Dnipropetrovsk region by the new government because it urgently needed his help. In the process, he has recast his image as a Ukrainian patriot. Many credit his strong hand at the helm of the region, as well as his personal financing of volunteer battalions, materiel for regular troops, and bounties placed on the heads of Russian fighters, as key to having stopped the separatists’ push into other parts of Ukraine.

But those volunteer battalions receive their salaries from Kolomoiskiy, not the government of Ukraine. He has in effect raised a large private army that he has now proven ready to employ to protect his interests should they diverge from those of the government.

On his blog last week, Ukrainian Parliament member and former journalist Mustafa Nayyem argued for Kolomoiskiy’s dismissal : “As a class, oligarchs represent as great a danger to the community as does the external enemy on our eastern border. They are the sources of corruption… And most important, it is they who are least interested in the building of a new country.”

It is the mission of building a new country that concerned Minister Jaresko most. “The Ukrainian people have chosen their set of values,” she argued. “…it’s about having a market economy that’s competitive and not driven by either oligarchs or other interests. And I think Ukraine has made that choice. I think they’ve made that choice and there’s no going back.”

But Ukraine has made that choice before and gone back. The long-suffering citizens of Ukraine have seen a similar movement—2004’s Orange Revolution—fail before. And now again, episodes like that at UkrTransNafta do not encourage them to believe that the change they stood for at Maidan last winter will come to fruition.

Reining in men like Kolomoiskiy and the corruption and instability they breed is the central challenge for Ukraine. Such men are first and foremost loyal to themselves. Even steps taken to defend Ukraine are in their interest; no Ukrainian oligarch has any desire to play second fiddle to a conquering Russian one. But nor are they interested in allowing a reformist Ukrainian government to destroy their sources of income or power. As already proven, they will battle to protect their interests, even if that may mean striking a temporary alliance of convenience with centers of power in Russia.

Frustratingly, the West is mostly a bystander in this all-important struggle. Western governments and financial institutions can provide technical expertise and even financial assistance. But this is not at core a technical or financial problem. It is a Ukrainian political struggle and will have to be won or lost by Ukrainians.

Update: Over night, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko dismissed Kolomoiskiy as governor of Dnipropetrovsk .

Foreign Policy

Center on the United States and Europe

Kevin Dong, Mallie Prytherch, Lily McElwee, Patricia M. Kim, Jude Blanchette, Ryan Hass

March 15, 2024

The Brookings Institution, Washington DC

10:00 am - 11:30 am EDT

Online only

9:00 am - 11:45 am EDT

Advertisement

Supported by

In High-Profile Raids, Zelensky Showcases Will to Tackle Corruption

President Volodymyr Zelensky is eager to highlight his crackdown on corruption, ahead of E.U. accession talks and possible Western investigations of war aid.

- Share full article

By Andrew E. Kramer

KYIV, Ukraine — A leaked police video showing bundles of cash found in an official’s sofa. A tax inspector accused of fraud in issuing refunds. The dismissal of the chief of the customs service and his top deputy, as well as senior officials from a consumer protection agency and the forestry agency. And a search warrant served on a business tycoon once seen as all but untouchable for his close ties to government.

These new details emerged Thursday from an expanding investigation into corruption in domestic military procurement in Ukraine, following a dozen searches of homes and offices on Wednesday, and from corruption cases that had lingered in the Ukrainian courts for months.

Corruption, and Ukraine’s long struggle against it, had mostly dropped off the agenda after the Russian invasion last February, as Ukrainians rallied around the army and government at a time of national peril.

But rather than playing down what many former Ukrainian officials and analysts say are all but unavoidable instances of wartime profiteering, President Volodymyr Zelensky pivoted earlier this year to a policy of high-profile enforcement.

Analysts cited several reasons for the change.

To some extent, it signals a resumption of Mr. Zelensky’s prewar focus on fighting corruption, aimed at maintaining Ukrainians’ trust in the wartime government despite the flurry of accusations and dismissals of government officials. It may represent the government’s effort to put its own house in order, as it faces the prospect of greater scrutiny of financial aid and weapons transfers from the Republican-led House in Washington.

And Mr. Zelensky is expected to meet in Kyiv on Friday with the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, and Charles Michel, the president of the European Council, to discuss Ukraine’s reconstruction and its candidacy for membership in the bloc. Ukraine’s ability to get a handle on graft and corruption is an overriding concern for the Western allies in both those areas.

Previously, Mr. Zelensky’s government had made a string of dismissals mostly for relatively minor lapses of judgment or tone-deafness, like the optics of driving expensive cars or vacationing abroad. But the cases opened after Wednesday’s searches included serious accusations of graft and official abuse.

“Today is a fruitful day for our country,” Mr. Zelensky said in an overnight address to the nation on Wednesday. Mr. Zelensky said he would “change as much as necessary to ensure that people do not abuse power” within his government.

He emphasized that the anti-corruption crackdown would focus primarily on domestic military procurement. None of the criminal investigations and dismissals of officials touched on the billions of dollars in foreign aid or weapons transferred to Ukraine from its Western allies. Mr. Zelensky highlighted that contrast in his speech, saying the strict controls now applied to foreign military aid should be a model for military contracting within Ukraine.

“Any domestic supply, any procurement, everything must be absolutely as clean and honest as the external supply for our defense,” he said. He said he would seek “cleanliness of process” in the Defense Ministry and army.

Underscoring that point, Ukrainska Pravda, a Ukrainian news outlet, published on Thursday a video it said showed the police searching the home of a former deputy minister of defense, Oleksandr Myronyuk, over suspicions of graft in purchases for the army before the Russian invasion. In the video, which could not be independently verified, investigators pull bundle after bundle of cash from a storage space in a sofa bed. Also on Thursday, a court ordered another deputy minister of defense, Viacheslav Shapovalov, suspected of fraud in military procurement during the war, placed in pretrial detention with bail set at 402 million hryvnia, or about $10 million.

Ukrainian journalists had reported on graft in food purchases for the military before the government acted, in articles that some commentators in Ukraine suggested had forced Mr. Zelensky’s hand.

The Ukrainian leader swept to a landslide victory in presidential elections in 2019 on promises to rid Ukraine of graft and waste in government and had made some steps in that direction, such as stripping members of Parliament of immunity from prosecution.

In the post-Soviet period, Ukraine never fully privatized many large industrial enterprises, and the resulting state-owned or partially state-owned companies became easy targets for graft. The country was also plagued by so-called strategic corruption by the Kremlin, with Ukrainian businessmen allowed a bonanza of profits trading in Russian natural gas in exchange for promoting Russian interests through bribery and subsidies to pro-Russian news media outlets.

Mr. Zelensky’s pre-invasion record in tackling these problems had been mixed. Anti-corruption groups and former officials criticized him for stalling a swirl of investigations into the business dealings of an oil and media tycoon, Ihor Kolomoisky, who had supported his television career and election campaign.

But the police searched the home of Mr. Kolomoisky Wednesday, accusing him of embezzlement of about $1 billion from a partially state-owned oil company, suggesting Mr. Zelensky’s wartime crackdown will not exempt his former supporter from scrutiny.

While Mr. Zelensky focused attention on corruption in military procurement, the crackdown did not stop there. On Wednesday, the police searched the home of Arsen Avakov, a former interior minister who resigned in 2021 after a scandal-ridden tenure.

Mr. Avakov told the Ukrainian news media that law enforcement officers were pursing an investigation into the helicopter crash that killed his successor, Denys Monastyrsky, on Jan. 18 outside Kyiv. Mr. Avakov had overseen the purchase of the helicopter, but he said the police had found no information relevant to the crash investigation.

In another investigation into a political ally of Mr. Zelensky, the government’s National Agency on Corruption Prevention said in a statement that a criminal investigation had been opened into a deputy head of the Parliamentary arm of Mr. Zelensky’s political party, Pavlo Khalimon. Ukrainian journalists had earlier reported that Mr. Khalimon had purchased a luxurious home in Kyiv that cost far more than his salary would allow.

Whatever the government’s motivation in ordering the crackdown, it drew praise from analysts who have for years vented frustration at the slow pace of anti-corruption activity.

“Long overdue,” Timothy Ash, an economist who has tracked Ukraine’s anticorruption efforts, tweeted about the search of Mr. Kolomoisky’s home. The action would “send a strong signal to push on with early E.U. accession.”

Vitaly Sych, the editor in chief of NV, a Ukrainian news outlet, said the crackdown stemmed primarily from recent news media reports on corruption as well as the coming E.U. summit, and quipped that, maybe someday, “we could fire these people without visits from E.U. officials.”

The head of the parliamentary faction of Mr. Zelensky’s political party, Davyd Arakhamia, wrote that “the country in wartime will change. If anybody is not prepared for change, then the government will come and help them change.”

Maria Varenikova contributed reporting from Kyiv

Andrew E. Kramer is the Times bureau chief in Kyiv. He was part of a team that won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize in International Reporting for a series on Russia’s covert projection of power. More about Andrew E. Kramer

Our Coverage of the War in Ukraine

News and Analysis

Ukraine’s troop-starved brigades have started their own recruitment campaigns to fill ranks depleted in the war with Russia.

The Czech Republic froze the assets of two men and a news website it accused of running a “Russian influence operation” in Europe.

Ahead of the U.S. elections, Russia is intensifying efforts to elevate candidates who oppose aid for Ukraine and support isolationism, disinformation experts say.

Symbolism or Strategy?: Ukrainians say that defending places with little strategic value is worth the cost in casualties and weapons , because the attacking Russians pay an even higher price. American officials aren’t so sure.

Elaborate Tales: As the Ukraine war grinds on, the Kremlin has created increasingly complex fabrications online to discredit Ukraine’s leader, Volodymyr Zelensky, and undermine the country’s support in the West.

Targeting Russia’s Oil Industry: With its army short of ammunition and troops to break the deadlock on the battlefield, Kyiv has increasingly taken the fight beyond the Ukrainian border, attacking oil infrastructure deep in Russian territory .

How We Verify Our Reporting

Our team of visual journalists analyzes satellite images, photographs , videos and radio transmissions to independently confirm troop movements and other details.

We monitor and authenticate reports on social media, corroborating these with eyewitness accounts and interviews. Read more about our reporting efforts .

IMAGES

COMMENTS

March 6, 2024, 2:54 PM. During a recent off-the-record think tank discussion on Ukraine, a respected journalist raised the issue of the damaging effects that Ukraine’s ongoing corruption issues ...

Mr. Zelensky has been on a mission to convince Ukrainians and donor countries that he has things under control. In May the chief of Ukraine’s Supreme Court was arrested on bribery charges.In ...

The latest revelations about corruption in Ukraine tell a complex story. A scandal has engulfed the Ukrainian ministry of defence, where 100,000 mortar shells worth about $40m ...

Since the start of the war with Russia, the Biden administration has mostly ignored Ukraine's corruption history. Questions resurfaced about its suitability as a recipient of massive infusions of aid.

Ukraine’s efforts to improve governance deserve endorsement. The transformation of the country’s public health procurement system demonstrates how rooting out corruption can save money and lives.

The state of the war in Ukraine, January 30 2024. Institute for the Study of War. But it’s widely hoped that Biden will be able to bring the senate round to his way of thinking. One possible ...

Corruption in Ukraine. A week after the E.U. formally named Ukraine as a candidate, the head of the bloc’s executive arm, Ursula von der Leyen, told the Ukrainian parliament today that anti ...

Ukraine’s corruption shake-up, briefly explained. Top officials are ousted or resign in the biggest reshuffle since the start of the Russian invasion. By Jen Kirby [email protected] Jan 24, 2023 ...

Since independence, Ukraine has struggled continuously to break the iron triangle of oligarchic rule, corruption, and financial instability that has left Ukraine mired in poverty. It has made ...

Ukraine’s ability to get a handle on graft and corruption is an overriding concern for the Western allies in both those areas. Image Mr. Zelensky with President Joe Biden at the White House in ...