- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

current events

Lesson of the Day: ‘Critical Race Theory: A Brief History’

In this lesson, students will look at the spread across the country of legislation opposed to critical race theory. Then, they will consider the impact of these bills on their own schools and learning.

By Jeremy Engle

Lesson Overview

Featured Article: “ Critical Race Theory: A Brief History ” by Jacey Fortin

Today’s lesson looks at how an academic legal framework for understanding racism in the United States, developed during the 1980s, has become a hot-button political issue 40 years later.

The Times’s Jacey Fortin writes:

About a year ago, even as the United States was seized by protests against racism, many Americans had never heard the phrase “critical race theory.” Now, suddenly, the term is everywhere. It makes national and international headlines and is a target for talking heads. Culture wars over critical race theory have turned school boards into battlegrounds, and in higher education, the term has been tangled up in tenure battles . Dozens of United States senators have branded it “activist indoctrination.”

In this lesson, students will look at the spread of anti-critical-race-theory regulations across the country, and the larger questions they raise over teaching about race and racism in schools. Then, they will consider the impact of these bills on their own communities, schools and learning.

Part 1: Reflect on Your Experiences

What do you know about the ongoing controversy over the teaching of critical race theory?

Do you live in a state that has tried to restrict, limit or ban the teaching of what has been labeled C.R.T. and the teaching of “divisive” content that includes The 1619 Project from The New York Times? What is your opinion of these efforts? How do you think they might impact your school, your teachers or your learning?

Before reading the featured article, take several minutes to share your thoughts and experiences in a journal by responding to either or both of the following prompts:

What have you studied or learned about race or racism in school, whether in the context of a history or literature class, in an advisory or homeroom, or in any other class? Looking back, how often in your school experience has race or racism been studied or discussed? Do you think the discussions have been productive, informative or enlightening? Do you feel that classroom discussions on these topics have ever been avoided, silenced or marginalized?

How comfortable do you feel discussing race in school? Would you like to see the topic addressed more fully, accurately and honestly in schools? Or, do you feel that race and racism have already been explored enough — or even too much? Have you ever felt singled out, criticized or in any other way made to feel uncomfortable in a classroom because of your race or ethnicity?

Part 2: Analyze a Map

Look at the two maps in “ Efforts to Restrict Teaching About Racism and Bias Have Multiplied Across the U.S. ,” published in Chalkbeat in July. One map tracks efforts to restrict and the other tracks efforts to expand education on racism, bias, the contributions of specific racial or ethnic groups to U.S. history, or related topics.

After examining both maps closely, respond to the following prompts adapted from our weekly feature What’s Going On in This Graph? :

What do you notice about the two maps?

What do you wonder? What questions do you have about the new educational legislation and curriculums tracked in the two maps?

What impact will these maps have on you and your community? On the nation?

What’s going on in these maps? Write a catchy headline that captures their main idea.

Questions for Writing and Discussion

Read the featured article , and then answer the following questions:

1. What is critical race theory, according to the article? How would you explain it in your own words? Who are some of its leading theorists and practitioners?

2. Why do critical race theorists reject the philosophy of “colorblindness”? What does Mari Matsuda, a law professor at the University of Hawaii who was an early developer of the theory, mean when she says of racism, “The problem is not bad people. The problem is a system that reproduces bad outcomes.”

3. Why are people talking about critical race theory now? How has C.R.T. gone from academic classrooms and papers to a frontline in the ongoing culture wars?

4. What do critics of C.R.T., like Christopher F. Rufo, believe are the dangers of the framework and its teaching? Why has Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida called critical race theory “state-sanctioned racism”? How accurate or convincing is this charge, in your opinion?

5. How have people like Prof. Kimberlé Crenshaw responded to critics of C.R.T.? Do you believe they have adequately addressed the concerns of its critics? Do you find these rebuttals persuasive?

6. Who was Prof. Derrick Bell and what role did he play in the emergence of C.R.T. from the field of legal studies? Why was it a new idea in the 1980s to question the neutrality of the American legal system?

7. The article ends with a quote from Professor Matsuda:

I see it like global warming. We have a serious problem that requires big, structural changes; otherwise, we are dooming future generations to catastrophe. Our inability to think structurally, with a sense of mutual care, is dooming us — whether the problem is racism, or climate disaster, or world peace.

Do you think Ms. Matsuda’s comparison between C.R.T. and climate change is a useful one? In what ways are the persistence of racism and racial inequalities like global warming? Do you think C.R.T. is an effective way to diagnose and understand these persistent disparities and problems? Why or why not?

Going Further

Option 1: Share your reaction to the spread of anti-C.R.T. legislation in states and local school districts.

In “ Disputing Racism’s Reach, Republicans Rattle American Schools ,” Trip Gabriel and Dana Goldstein describe how a culture-war brawl has spilled into the country’s educational system, and how Republicans at the local, state and national levels are trying to block curriculums that emphasize systemic racism:

In Loudoun County, Va., a group of parents led by a former Trump appointee are pushing to recall school board members after the school district called for mandatory teacher training in “systemic oppression and implicit bias.” In Washington, 39 Republican senators called history education that focuses on systemic racism a form of “activist indoctrination.” And across the country, Republican-led legislatures have passed bills recently to ban or limit schools from teaching that racism is infused in American institutions. After Oklahoma’s G.O.P. governor signed his state’s version in early May, he was ousted from the centennial commission for the 1921 Race Massacre in Tulsa, which President Biden visited on Tuesday to memorialize one of the worst episodes of racial violence in U.S. history. From school boards to the halls of Congress, Republicans are mounting an energetic campaign aiming to dictate how historical and modern racism in America are taught, meeting pushback from Democrats and educators in a politically thorny clash that has deep ramifications for how children learn about their country.

However, in “ Scholarly Groups Condemn Laws Limiting Teaching on Race ,” Jennifer Schuessler reports that many groups are challenging the new legislation restricting explorations of racism and race:

A coalition of more than six dozen scholarly and educational groups has signed onto a statement decrying the spread of proposed legislation limiting classroom discussion of race, racism and other so-called “divisive concepts,” calling such laws an infringement on “the right of faculty to teach and of students to learn” and a broader threat to civic life. “The clear goal of these efforts is to suppress teaching and learning about the role of racism in the history of the United States,” says the statement, whose signatories include the American Historical Association, the American Association of University Professors, the American Federation of Teachers and the Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Read one or both of the articles, and then share your take:

What do you think of efforts to restrict how schools teach race and racism? What do you see as possible benefits or dangers of this legislation?

Do you agree with Republican senators that the focus on systemic racism is a form of “activist indoctrination”? Or are you persuaded by scholars who charge that laws limiting classroom discussion of race, racism and other “divisive concepts” are an infringement on “the right of faculty to teach and of students to learn” and a broader threat to civic life?

What’s really going on here? How much of the debate really has to do with the tenets of critical race theory or the writing of The 1619 Project? Are public schools, in the words of Mr. Rufo , “being devoured by a hostile ideology that seeks to divide the country by race and undermine the core principle of democratic control.” Or is legislation to restrict or prohibit C.R.T. and related ideas really an attempt to “whitewash U.S. history” and “deny students and scholars the chance to understand the past,” as Ms. Crenshaw argues in The Washington Post? How founded are the fears on each side? Do you think there is room for common ground in the debate?

If you’d like to join a conversation with other students, share your thoughts in our related Student Opinion prompt .

Option 2: Closely look at anti-C.R.T. legislation in your state and across the country.

To date, more than 20 states — including New Hampshire, Michigan, Texas, Florida, South Carolina and Arkansas — have introduced regulations restricting teaching about race. Some of these laws have taken aim explicitly at critical race theory, while others are crafted more broadly to address what they call “divisive concepts.” Other bills have sought to prohibit classroom use of The 1619 Project, an initiative of The New York Times Magazine that explores the history of slavery, positing the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in Virginia in 1619 as the nation’s “very origin.”

For example, in June, Florida’s State Board of Education passed amendments prohibiting critical race theory and The 1619 Project from its classrooms. One amendment read :

Instruction on the required topics must be factual and objective, and may not suppress or distort significant historical events, such as the Holocaust, slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction, the civil rights movement and the contributions of women, African American and Hispanic people to our country, as already provided in Section 1003.42(2), F.S. Examples of theories that distort historical events and are inconsistent with State Board approved standards include the denial or minimization of the Holocaust, and the teaching of Critical Race Theory, meaning the theory that racism is not merely the product of prejudice, but that racism is embedded in American society and its legal systems in order to uphold the supremacy of white persons. Instruction may not utilize material from the 1619 Project and may not define American history as something other than the creation of a new nation based largely on universal principles stated in the Declaration of Independence.

Tennessee House Bill SB 0623 bans any teaching that could lead an individual to “feel discomfort, guilt, anguish or another form of psychological distress solely because of the individual’s race or sex” and restricts teaching that leads to “division between, or resentment of, a race, sex, religion, creed, nonviolent political affiliation, social class or class of people.”

Texas House Bill 3979 forbids teaching that “slavery and racism are anything other than deviations from, betrayals of, or failures to live up to, the authentic founding principles of the United States.”

Closely read, analyze and interpret one of the amendments, proposals or bills above, or one from your own state or local school board. Then answer the following questions:

What do you notice about the text? What words, phrases and language stand out and why? What questions do you have about the proposal or legislation?

Try your best to sort through the jargon and legalese in order to try to restate what you have read in your own words, and wrestle with their implications. For example, what does it mean in the Florida amendment to “distort significant historical events”? What do you think that might look like in practice? Or take a look at the Tennessee bill. How will students, teachers, parents and interested citizens determine if teaching leads to “division between, or resentment of, a race, sex, religion, creed, nonviolent political affiliation, social class or class of people”?

What impact do you think the legislation or proposal will have on teachers, students and classrooms? Do you think these rules and laws will help or hinder a safe, healthy and productive learning environment? Will they ensure an accurate understanding of race and American history, or have the opposite effect and deny it? Are these laws and amendments too broad or vague — with language like “divisive concepts” — and will they therefore be easily misused? Or are they so broad that they are mostly symbolic and are likely to have little real impact in the classroom?

Option 3: Imagine you have been invited to your local school board or state capital to speak in favor of or against anti-C.R.T. laws.

Local school board meetings have become central battlegrounds in the fight over C.R.T. But one important perspective that has been largely absent in the ongoing debate is that of students and teenagers: What do you think adults are missing in this conversation? What would you want them to understand from the point of view of a teenager? How do you think schools should teach about race and racism?

Working individually or in a team, write the opening statement to present to your local school board. Be sure to draw upon your own specific experiences of studying race and racism in school that you began articulating in the warm-up activity.

To help formulate your point of view, you might take a look at the growing list of resources available on this topic, within and outside The Times.

Additional Resources

From The New York Times

Demonizing Critical Race Theory

The Excesses of Antiracist Education

Why Is the Country Panicking About Critical Race Theory?

We Disagree on a Lot of Things. Except the Danger of Anti-Critical Race Theory Laws.

The War on History Is a War on Democracy

The Daily Podcast | The Debate Over Critical Race Theory

The Argument Podcast | What Are States Really Banning When They Ban Critical Race Theory in Classrooms?

From other publications:

The Panic Over Critical Race Theory Is an Attempt to Whitewash U.S. History by Kimberlé Crenshaw (The Washington Post)

There Is No Debate Over Critical Race Theory by Ibram X. Kendi (The Atlantic)

Disingenuous Defenses of Critical Race Theory by Christopher F. Rufo (The New York Post)

NYT Op-Ed Illustrates How the Left Employs Critical Race Theory Gaslighting (The Federalist)

First It Was Sex Ed. Now It’s Critical Race Theory. (FiveThirtyEight)

Critical Race Theory Can’t Be Banned. It Can Be Exposed, Mocked and Avoided. (Reason Magazine)

We Must Fight Un-American Race Theories (National Review)

About Lesson of the Day

• Find all our Lessons of the Day in this column . • Teachers, watch our on-demand webinar to learn how to use this feature in your classroom.

Jeremy Engle joined The Learning Network as a staff editor in 2018 after spending more than 20 years as a classroom humanities and documentary-making teacher, professional developer and curriculum designer working with students and teachers across the country. More about Jeremy Engle

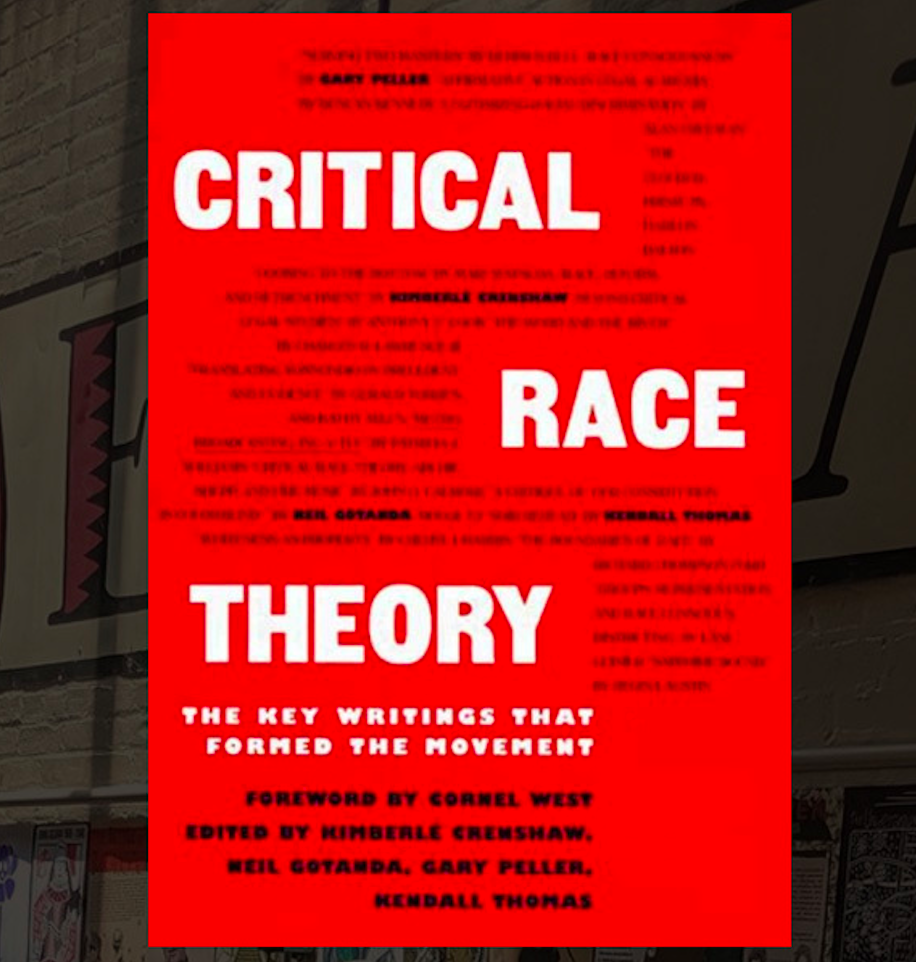

Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement

What is Critical Race Theory and why is it under fire from the political right? This foundational essay collection, which defines key terms and includes case studies, is the essential work to understand the intellectual movement

Why did the president of the United States, in the midst of a pandemic and an economic crisis, take it upon himself to attack Critical Race Theory? Perhaps Donald Trump appreciated the power of this groundbreaking intellectual movement to change the world.

In recent years, Critical Race Theory has vaulted out of the academy and into courtrooms, newsrooms, and onto the streets. And no wonder: as intersectionality theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw recently told Time magazine, "It's an approach to grappling with a history of white supremacy that rejects the belief that what's in the past is in the past, and that the laws and systems that grow from that past are detached from it." The panicked denunciations from the right notwithstanding, CRT has changed the way millions of people interpret our troubled world.

Support The Center for Perservation of Civil Rights Sites

Privacy Policy

Report accessibility issues and get help

The Center for Preservation of Civil Rights Sites University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design

Critical Race Theory

- Introduction

Introduction to Critical Race Theory

Introductory monographs and collections, key articles, critical legal studies, legal feminism.

- Developments in CRT

- Subjects Related to CRT

- Racial Justice in the U.S.

- Racial Justice in North Carolina

Reference Librarian

"Critical race theory builds on the insights of two previous movements, critical legal studies and radical feminism, to both of which it owes a large debt. It also draws from certain European philosophers and theorists, such as Antonio Gramsci, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida, as well as from the American radical tradition exemplified by such figures as Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, W. E. B. Du Bois, César Chávez, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Black Power and Chicano movements of the sixties and early seventies."

- Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic, Critical Race Theory: An Introduction (3rd Edition)

Critical Race Theory: An Introduction By Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic. Third edition available in print and online ; Second edition in print ; First edition in print . Written for a general audience, this text is a comprehensive introduction to the topic, covering major ideas, resources, and scholars. Each chapter provides discussion questions and a useful bibliography.

Critical Race Theory: A Primer , by Khiara M. Bridges. Available online through West Study Aids. Intended as an introductory text to the subject, this text covers the history of CRT, core concepts, the intersection of race with other characteristics, and contemporary issues in CRT.

Critical Race Theory: Cases, Materials, and Problems , by Dorothy Brown. This casebook examines American law from a Critical Race Theory perspective, including chapters on torts, contracts, criminal procedure, civil procedure, property, and criminal law.

Critical Race Theory: The Cutting Edge , ed. Richard Delgado. Available in print . Published in 1995, this collection gathers key essays from en early era of CRT; many are now foundational texts in the subject.

Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Informed the Movement , ed. Kimberle Crenshaw et al. Available in print . This collection gathers important essays from the origins of CRT.

Crossroads, New Directions, and a New Critical Race Theory , ed. Francisco Valdes, Jerome McCristal Culp, and Angela P. Harris. Available in print and online . In this volume, thirty-one CRT scholars present their views on the ideas and methods of CRT, its role in academia and in the culture at large, and its past, present, and future.

The Derrick Bell Reader , ed. Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic. Available in print . The Derrick Bell Reader reflects the tremendous breadth of issues that Bell has grappled with over his phenomenal career, including affirmative action, black nationalism, legal education and ethics.

The Law Unbound!: A Richard Delgado Reader , ed. Adrien Katherine Wing and Jean Stefancic. Available in print and online . This book offers the best and most influential writings of Richard Delgado, one of the founding figures of the critical race theory movement, spanning topics such as hate speech, affirmative action, the war on terror, the endangered status of black men, and the place of Latino/as in the civil rights equation.

Race, Racism, and American Law , ed. Derrick Bell. Fifth edition available online . This casebook examines the role of racism in a society with growing disparities in income, wealth, and opportunity.

Reproducing Racism: How Everyday Choices Lock in White Advantage , by Daria Roithmayr. Available in print . Legal scholar Daria Roithmayr argues that racial inequality lives on because white advantage functions as a powerful self-reinforcing monopoly, reproducing itself automatically from generation to generation even in the absence of intentional discrimination. Drawing on work in antitrust law and a range of other disciplines, Roithmayr compares the dynamics of white advantage to the unfair tactics of giants like AT&T and Microsoft.

Seeing a Color-Blind Future: The Paradox of Race , Patricia Williams. Available in print . In these five collected essays, Patricia J. Williams asks how we might achieve a world where "color doesn't matter"--where whiteness is not equated with normalcy and blackness with exoticism and danger.

White by Law: The Legal Construction of Race , by Ian F. Haney López. First edition available in print and online . Revised tenth anniversary edition available in print and online . White by Law traces the reasoning employed by the courts in their efforts to justify the whiteness of some and the non- whiteness of others. Haney Lopez reveals the criteria that were used, often arbitrarily, to determine whiteness, and thus citizenship: skin color, facial features, national origin, language, culture, ancestry, scientific opinion, and, most importantly, popular opinion.

Derrick A. Bell, " Who's Afraid of Critical Race Theory? " 4 University of Illinois Law Review, 893-910 (1995). Partially a response to the publication of The Bell Curve, Bell describes the origins of CRT, its core ideas, and responds to contemporary criticism.

Derrick A. Bell, " Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest Convergence Dilemma, " 93 Harvard Law Review 518 (1979-1980). In this essay, Bell explores one of CRT's core concepts, that of interest convergence, by examining how the decision in Brown v. Board also benefited whites.

Roy L. Brooks and Mary Jo Newborn, " Critical Race Theory and Classical-Liberal Civil Rights Scholarship: A Distinction Without a Difference ," 82 Cal. L. Rev. 787 (1994). Brooks and Newborn examine how CRT differs from other legal theories.

Devon W. Carbado, " Critical What What ," 43 Connecticut Law Review 1593 (2011). Carbado gives an overview of the field.

Devon W. Carbado and Mitu Gulati, "T he Law and Economics of Critical Race Theory ," 112 Yale Law Review 1757 (2003). In this review of Crossroads, Directions, and a New Critical Race Theory ,Carbado and Gulati demonstrate that the fields of law and economics and critical race theory rarely interact with one another and argue that it would be productive for both fields to consider how they might interact.

Robert S. Chang, " Toward an Asian American legal scholarship: Critical race theory, post-structuralism, and narrative space ." 81 California Law Review 1243 (1993). Chang argues that then-current critical race theory failed to account for the unique issues that Asian-Americans face, including nativistic racism and the model minority myth. This article offers a framework for constructing an Asian-American CRT that acknowledges the different position of disempowered groups while maintaining the possibility of solidarity among them.

Sumi Cho, " Post-Racialism ," 94 Iowa Law Review 1589 (2009). Cho explores the idea of post-racialism and its consequences.

Kimberle Williams Crenshaw, " Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics ," 1989 University of Chicago Legal Fourm 139-168 (1989). Crenshaw's landmark article introduced the concept of intersectionaity by examining the treatment of Black women in race and sex discrimination cases.

Kimberle Williams Crenshaw, " Race, Reform, and Retrenchment Transformation and Legitimation in Antidiscrimination Law, " 1010 Harvard Law Review 1331 (1998). Crenshaw examines scholarship by both conservative and critical legal scholars on efforts towards racial equality in the U.S. and demonstrates the racist nature of supposedly neutral norms.

Peggy Davis. “ Law as Microaggression ” 98 Yale Law Journal 1559-1577 (1989). Davis explores the reasons why African-Americans believe the American court system is biased against them, utilizing cognitive psychology, psychoanalysis, and studies of both African-Americans and participants in the legal system.

Richard Delgado. " Storytelling for oppositionists and others: A plea for narrative ." 87 Michigan Law Review 2411–2441 (1989). This article argues that a focus on storytelling and narrative from disadvantaged groups is a key part of CRT, acting as a counter to dominant mindsets.

Cheryl I. Harris, " Whiteness As Property ," 106 Harvard Law Review 1707 (1993). In this essay, Harris explores the relationship between property and whiteness, arguing that whiteness, originally constructed as a racial identity, has evolved into a form of property under American law.

Charles R. Lawrence III, " The Id, the Ego, and Equal Protection: Reckoning with Unconscious Racism ," 39 Stanford Law Review 317 (1987). This article reconsiders the doctrine of discriminatory purpose, taking into account research on unconscious racism, and applying it to the realm of equal protection.

Nancy Leong, " Racial Capitalism ," 126 Harvard Law Review 2151 (2013). Leong applies a racial capitalist analysis to the field of law, demonstrating how white individuals and white institutions use nonwhite people to acquire social and economic value. She concludes by suggesting ways to dismantle racial capitalism.

Dorothy E. Roberts. " BlackCrit Theory and the Problem of Essentialism ," 53 University of Miami Law Review 855-862 (1998). This essay explores the problems of essentialism, such as assuming a common identity, attributing the issues facing African-Americans to all people of color in the U.S., and reinforcing a Black-white paradigm as the only way to view race in the U.S.

Critical Legal Studies , ed. Allan C. Hutchinson. Available online and in print . This edited collection contains essays on Critical Legal Studies. Topics of discussion include the intellectual foundations of the CLS movement, its principles and aims, its critique of the legal doctrine and ideas for change.

The Critical Legal Studies Movement , by Roberto Mangabeira Unger. First edition available online and in print , second edition available in print. The Critical Legal Studies movement sought to transform traditional views of law and legal doctrine, revealing the hidden interests and class dominations in prevailing legal frameworks. It remains highly influential, having spawned more recent movements, including feminist legal studies and Critical Race Theory.

Ideology and Community in the First Wave of Critical Legal Studies , by Richard W. Bauman. Available online . Bauman examines several major themes and arguments in the first decade of critical legal scholarship, predominantly in the U.S. in the period dating roughly from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s.

In 1982, a Critical Legal Studies symposium was held at Stanford Law School. The symposium issue published by the Stanford Law Review ( Critical Legal Studies Symposium of 1982, Stanford Law Review, v. 36 (1984)) includes many articles that are often cited as fundamental works of the movement.

Introduction to Feminist Legal Theory , by Martha Chamallas. First edition available in print and online , second edition available in print . Chamallas surveys the full range of legal issues affecting women, from rape and domestic violence to workplace discrimination and taxation issues. Her historical approach traces the evolution of legal feminism from the 1970s to the present.

Feminist Legal Theory: A Primer , by Nancy Levit and Robert R.M. Verchick. First edition available in print , second edition available in print . This text introduces the diverse strands of feminist legal theory and discuss an array of substantive legal topics, pulling in recent court decisions, new laws, and important shifts in culture and technology.

Critical Race Feminism: A Reader , ed. Adrien Katherine Wing. First edition available in print , second edition available in print and online . This anthology presents over 40 readings on the legal status of women of color by leading authors and scholars such as Anita Hill, Lani Guinier, Kathleen Neal Cleaver, and Angela Harris.

Feminist and Queer Legal Theory: Intimate Encounters, Uncomfortable Conversations , ed. Martha Albertson Fineman, Jack E. Jackson, Adam P. Romero. Available in print and online . This book brings together voices in feminist and queer theory to create an interdisciplinary dialogue that will define the terms of the debates between and within these theoretical frameworks for the next decade.

Feminist Legal History: Essays on Women and Law , ed. Tracy A. Thomas and Tracey Jean Boisseau. Available in print . This text showcases historical research and analysis that demonstrates how women were denied legal rights, how women used the law proactively to gain rights, and how, empowered by law, women worked to alter the law to try to change gendered realities.

- << Previous: Introduction

- Next: Developments in CRT >>

- Last Updated: Oct 10, 2023 4:35 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/criticalracetheory

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- Backchannel

- Newsletters

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Christina Wyman

What Is Critical Race Theory? Start Here

When my father called recently and asked me to explain critical race theory (CRT) to him, I initially balked. He voted for Donald Trump in both 2016 and 2020, a choice that caused a rift between us. I’ve since tried hard to reconcile Dad’s politics with what I know of him as a person.

He is a loving man and always supported my intellectual pursuits. He also knew that I’d studied race and racism in graduate school and that the issues were foundational to my dissertation and teaching at the college level. Finally, he knows that I make no apologies about my anti-racist and social justice-oriented identity, something he seems to simultaneously admire and abhor. Still, I couldn’t tell whether Dad was making an honest effort to learn about CRT, a field of study that I knew he’d never heard of until it became politicized. Was Dad truly on a path to learn, or was he just antagonizing me?

“Is this question in good faith?” I asked him. He’d said yes and explained that he wanted to help teach the concepts to a friend of his—someone I didn’t know and who, according to Dad, held extreme and unyielding views about race.

Dad next asked me to educate his friend about CRT, an invitation I politely declined in the name of self-preservation. “I’m going to have to pass on this opportunity,” I’d told him, “but your friend is free to locate the many resources that exist on the topic.” I forwarded him an article I’d written on CRT and told him to start there if he was serious about understanding my perspective.

Dad respected my decision to bow out of the discussion, but I still felt unsettled. As a white person, I firmly believe it is my responsibility to engage other white people in these discussions— especially when their politics diverge from mine. After this exchange, I began a quest for resources in the spirit of working through a dilemma that I believe a lot of allies, activists, and teachers can relate to: wanting to protect ourselves from engaging in those circular and fruitless discussions with bad-faith questions about why CRT and anti-racist goals matter, but also feeling a responsibility to guide people toward useful tools in the event that they are genuinely interested in learning about causes that have been weaponized and distorted in political discourse.

In considering my own education, I found it useful to start from the ground up.

Based on recent reports, those most opposed to critical race theory seem to know the least about it . But as writer and activist Scott Woods points out, “Students in K-12 classes aren’t being taught critical race theory … They aren’t being given any textbooks with such theories. They aren’t hiring guest speakers to come in and talk about how to use critical race theory in their science fair projects, even during Black History Month.” (You can follow him here .)

According to Georgetown Law professor Janel George , in writing for the American Bar Association , “CRT is not a diversity and inclusion ‘training’ but a practice of interrogating the role of race and racism in society that emerged in the legal academy and spread to other fields of scholarship.” In other words, CRT is more accurately a way of thinking and being than a series of lessons. To borrow from legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw , “ CRT is not a noun, but a verb .”

Matt Burgess

R Douglas Fields

Kate O'Flaherty

So what is critical race theory and why is it under attack? This Education Week explainer offers a definitional perspective on CRT and would be one place to start. In addition to helpful definitions, the piece covers the history of the debate and is an accessible primer for laypeople and experts alike.

When I want to learn more about something—anything—I never begin with politicians or tabloid news (unless I’m morbidly curious about how they’re spinning an issue to their own advantage). I begin with carefully vetted nonprofits, activists, teachers, and educational institutions that have demonstrated a clear investment in studying, understanding, and teaching about the issues I’m interested in—in this case, critical race theory and anti-racism.

Learn & Unlearn: Anti-racism resource guide is a resource published by the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. This outlet offers multimedia lessons, complete with video lectures by scholars like Keith Stanley Brooks and Gloria Ladson-Billings , and concludes with such thought-provoking reflection questions as “Racism and racial hierarchy have continued unchallenged. Why haven’t things changed?”

Finally, with Critical Race Theory: an introduction , Purdue Online Writing Lab offers an accessible discussion of the history of CRT and includes an extensive reference list for those interested in books on the topic.

After arriving at a definition, it always helps to learn more about how to productively discuss issues that have been scapegoated and spun for political gain. In my own work as an educator, I’ve often turned to Racial Equity Tools to enhance my thinking and teaching. This nonprofit offers a curriculum of fundamental and theoretical discussions about race, categorized under Anti-racism, Critical Race Theory, Racial Capitalism, Racial Identity Development, and Targeted Universalism.

Back when I taught a course on race, racism, and racial identity, one of my students discovered the University of Virginia’s Racial Dot Map , a tool that allows users to visually assess the racial demographics of a given location, including the racial and ethnic disparities of state prisons . This interactive resource was created by the University of Virginia’s Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service and added a great deal to our understanding of the racialization of geography.

For those who prefer film, The Power of An Illusion is a three-part PBS documentary that challenges people's understanding of race. According to John Powell, a professor of law at UC Berkeley, “While race, as a biological concept, is an illusion, racism is a sociological fact … the film helps people see that it’s not just an idea; it’s inscribed in our schools, in our churches, in our neighborhoods and housing. And it’s inscribed in the way we see each other" (as quoted in an interview with PBS ).

Finally, Code Switch is a wildly popular podcast published by NPR that deals candidly with race and racism. Code Switch is my personal favorite source for smart and current takes about how to talk about race, but also for keeping up with ever-evolving language around race, as with senior producer and cohost Shereen Marisol Meraji ’s discussion of outdated labels, words, and phrases that continue to be assigned to people who do not identify as white .

As I’ve taught my students, learning about critical race theory, race, racism, and how we are all situated in this nation’s racist past is not quite enough. Action is often called for, and I encourage students to donate and contribute to causes that align with themselves and their goals.

The Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History & Culture is a tremendous resource for those who want to learn more about race and current conversations, but also for anyone ready to take action. According to the museum's website, it is “the only national museum devoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life, history, and culture.” Curators have compiled a comprehensive multimodal curriculum titled Talking About Race that is conveniently divided into discussions about individual, interpersonal, and institutional forms of racism and how to work toward anti-racist change at all levels of society. This resource encourages a “questioning frame of mind” and includes such provocative questions as “Why do you want to be anti-racist? Considering the breadth and depth of racism, committing to being anti-racist may feel overwhelming, yet small choices made daily can add up to big changes. Reflect on choices you make in your daily life (i.e., who you build relationships with, what media you follow, where you shop). How do these choices reflect being antiracist?” This resource features the work of heavyweights such as Ibram X. Kendi , author of the groundbreaking and wildly popular book How to Be an Antiracist , and activist and speaker Verna Myers .

Finally, there are plenty of organizations that would welcome contributions and activist support. From the aforementioned resources, there's the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture donations page and the Boston University’s Center for Antiracist Research (founded by Kendi). And I've pointed my students toward myriad other ways to contribute to social change in the name of racial justice.

The New Jim Crow : Mass Incarceration In the Age of Colorblindness , for example, is a documentary based on the groundbreaking work of Michelle Alexander and both the film and written work are essential for anyone interested in learning about what have become central tenets of critical race theory.

According to the work's website, royalties from the 10th anniversary edition of The New Jim Crow will be donated to the MOSAIC Fund for Justice. The MOSAIC fund seeks to end mass incarceration, an issue that disproportionately affects Black populations.

In How to Be an Antiracist , Kendi writes that “to be antiracist is a radical choice in the face of history, requiring a radical reorientation of our consciousness.” This sentiment, to my mind, is the “verb” of CRT and the action I hope these resources inspire.

- 📩 The latest on tech, science, and more: Get our newsletters !

- Greg LeMond and the amazing candy-colored dream bike

- Bring on the fist bumps— tech conferences are back

- How to change your web browser in Windows 11

- Is it ok to torment NPCs in video games ?

- The power grid isn't ready for the renewable revolution

- 👁️ Explore AI like never before with our new database

- 🎮 WIRED Games: Get the latest tips, reviews, and more

- 💻 Upgrade your work game with our Gear team’s favorite laptops , keyboards , typing alternatives , and noise-canceling headphones

Jennifer M. Wood

Jason Parham

Megan Farokhmanesh

Angela Watercutter

Explainer: What 'critical race theory' means and why it's igniting debate

What is critical race theory, why is it getting attention.

HOW HAS THE DEBATE AFFECTED SCHOOLS?

What do educators say.

Jumpstart your morning with the latest legal news delivered straight to your inbox from The Daily Docket newsletter. Sign up here.

Reporting by Gabriella Borter; Editing by Colleen Jenkins and Marla Dickerson

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. , opens new tab

Thomson Reuters

Gabriella Borter is a reporter on the U.S. National Affairs team, covering cultural and political issues as well as breaking news. She has won two Front Page Awards from the Newswomen’s Club of New York - in 2020 for her beat reporting on healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, and in 2019 for her spot story on the firing of the police officer who killed Eric Garner. The latter was also a Deadline Club Awards finalist. She holds a B.A. in English from Yale University and joined Reuters in 2017.

Read Next / Editor's Picks

Industry Insight

Mike Scarcella, David Thomas

Karen Sloan

Henry Engler

Diana Novak Jones

Critical Race Theory Research Guide

- Choosing a Topic

- Finding Articles

- Finding Books

- Selected Websites

- Evaluating Sources

- Citation Management Services

- Law Student Guide to Identifying & Preventing Plagiarism

- Law Library Useful Links

- Accessing Databases & E-Resources

- Get Help & About the Author

General Tips

Most articles written by students take the form of either a comment or a note but there are other forms of writing such as narratives and storytelling that may be applicable to your situation. You will want to consult with your journal editors or professor about what is required from you. When choosing a topic, keep the following things in mind:

(1) choose something you find interesting since you will be spending a large amount of time living with this topic;

(2) think carefully about the scope of the topic – avoid overly broad or general topics as well as topics that are too narrow; and

(3) write about something new or look at an issue in a new light.

Ask Your Professor!

If you are writing a paper for a seminar class, your professor may have a list of topics that you can use or give you some ideas.

General Guides to Choosing a Topic

In addition to the Volokh and Falk books that were listed under Writing an Article - General Tips , the following are guides on finding a topic:

- Note Topic Selection on the LexisNexis Services

- Westlaw, Guide to Legal Research for Law Review

Newsletters

Bloomberg law reports.

Bloomberg Law publishes over 40 current report services that track news, topics and trends. Beyond the circuit splits found in the United States Law Week, Bloomberg Law Reports are an excellent resource for potential topics. You can even subscribe to email alerts or an RSS feed.

Mealey’s Newsletters (through Lexis)

Mealey's reports include case summaries, commentaries, and breaking news across different practice areas.

Law360 covers 45 practice areas and provides news on litigation, legislation and regulation, corporate deals, major personnel moves, and legal industry news and trends.

Lexis Emerging Issues

Emerging Issues Analysis articles provides guidance written by attorneys practicing in the field. The commentaries examine a wide range of recent cases, regulations, trends, and developments. They also cover national, state and international issues and provide expert insight in important areas and legal developments.

Westlaw Newsletters

- Westlaw Legal Newspapers & Newsletters

CCH Topical Newsletters

CCH is a subsidiary of Wolters Kluwer publishing company and it is well known for business, labor and employment, tax, and health resources. Find and click on your topical area of interest. Then look at the news options for your topic.

Circuit Splits

A circuit split is where there is a difference of opinion among the United States Courts of Appeal. These often make great law review topics.

United States Law Week (Bloomberg BNA)

The easiest way to browse the Split Circuit Roundup is to use the BNA Online Publications link off of the Law Library’s webpage.

Seton Hall Circuit Review

This law review includes a Current Circuit Splits feature that briefly summarizes current circuit splits, but it also features longer, more in-depth articles analyzing important developments in law at the federal appellate level.

Lexis & Westlaw Searches of Case Law

- Potential search to use: split or conflict /s court or circuit or authority

- Note that you will want to limit by date and subject to avoid an overwhelming list of results.

Browse CILP, SSRN, or BePress

By looking at what others are currently writing about, you can often find ideas about what you want to write about.

- SSRN (Social Science Research Network) This service offers separate electronic journals with abstracts of working papers and articles on various legal topics. Your liaison can assist you in becoming a subscriber to the journals in your areas of interest.

Table of Contents

Review the Table of Contents, comments, and/or notes in a textbook or treatise to generate topic ideas.

Blogs & Web Resources

- Howard J. Bashman, How Appealing

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Finding Articles >>

- Last Updated: Oct 24, 2023 1:21 PM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.uc.edu/criticalracetheory

University of Cincinnati Libraries

PO Box 210033 Cincinnati, Ohio 45221-0033

Phone: 513-556-1424

Contact Us | Staff Directory

University of Cincinnati

Alerts | Clery and HEOA Notice | Notice of Non-Discrimination | eAccessibility Concern | Privacy Statement | Copyright Information

© 2021 University of Cincinnati

What Is Critical Race Theory and Why Are People So Upset About It?

Most Americans are not familiar with term critical race theory, but that hasn’t stopped some from getting upset about attempts to reckon with the sprawling repercussions of slavery.

What Is Critical Race Theory?

ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS | AFP | Getty Images

A mother and daughter stand before a historical marker for the the 1921 Tulsa Massacre on Monday, in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

One hundred years ago, on May 31 and June 1 of 1921, white rioters ransacked and set ablaze a wealthy Black neighborhood in northern Tulsa, Oklahoma – a place known as "Black Wall Street," where Black people were business owners, doctors, lawyers and where they were building and accumulating wealth at a time when that was unheard of in much of America.

The massacre, which left hundreds of Black people dead and roughly 10,000 homeless in its immediate aftermath, has haunted families for generations – not only by stunting their family trees but also by stripping them of future opportunities that such a solid foundation would have brought.

"I call on the American people to reflect on the deep roots of racial terror in our Nation and recommit to the work of rooting out systemic racism across our country," President Joe Biden said in a proclamation on Monday, in which he underscored the devastating repercussions the federal highway system and redlining had in making it "nearly impossible" for the neighborhood to recover.

When the president visits Tulsa on Tuesday to mark the century that's passed since the Tulsa race riot and meet survivors and their families, he's set to deliver remarks and acknowledge how federal laws and policies, to this day, stunt the ability of Black communities to thrive.

In doing so, he will effectively deliver a lesson on critical race theory – the term that's roiling conservatives in Congress and statehouses across the country.

And while nearly 80% of Americans have not heard of the term critical race theory or are unsure of whether they have, according to one recent poll , that hasn't stopped some people from getting really, really upset about what they see as the Biden administration's attempt to reckon with the sprawling repercussions of slavery.

Political Cartoons

So What Is Critical Race Theory, Anyway?

Critical race theory traces its origins to a framework of legal scholarship that gained momentum in the 1980s by challenging conventional thinking about race-based discrimination, which for decades assumed that discrimination on the basis of race could be solved by expanding constitutional rights and then allowing individuals who were discriminated against to seek legal remedies. However, some legal scholars pointed out that such solutions – though well-intentioned – weren't effective because, they argued, racism is pervasive and baked into the foundation of the U.S. legal system and society as a whole.

Take the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education, for example, in which the Supreme Court ruled in 1954 that separate is not equal and that state laws protecting segregated public schools are unconstitutional. While the ruling gave Black children the right to attend schools that had long prohibited them, it also resulted in some white families enrolling their children in private schools, moving to the suburbs or redrawing school district boundaries in an effort to resist integration.

Even now, more than half a century after the Brown v. Board decision, efforts are still underway by some wealthy and majority white communities to create their own school districts , and there exists a $23 billion gap between majority white and majority Black school districts out of which spills an array of inequalities.

Today, critical race theory is used by academic scholars – and not just in law schools – to describe how racism is embedded in all aspects of American life, from health care to housing, economics to education, clean water to the criminal justice system and more. Those systems, they argue, have been constructed and protected over generations in ways that give white people advantages – sometimes in ways that are not obvious or deliberately insidious but nonetheless result in compounding disadvantages for Black people and other racial and ethnic minorities.

Many Americans, especially white people, believe racism is the product of intentionally bad and biased individuals, but critical race theory purports that racism is systemic and is inherent in much of the American way of life, no matter how far removed we are today from its origins.

Over the last two decades, academic researchers and policymakers have increasingly focused on issues of equity, linking how systems were established in the U.S. with how and why they serve different groups of people differently.

In education, for example, that effort took off after Congress passed No Child Left Behind, which for the first time required states to disaggregate academic achievement data by race, income and disability status. From there, policymakers began linking the racial makeup of school districts to state and local education funding, or lack thereof, and their broader academic profiles – not just math and reading scores but also access to high quality teachers, Advanced Placement courses, extracurricular activities and school counselors, graduation rates and much more.

Today, policymakers are shining a light on glaring racial gaps in a whole host of domestic policy arenas, and as the country reckons with systemic racism and inequality in the wake of George Floyd's death at the hands of a white police officer, the term critical race theory is having a moment in the sun.

Why Are People Talking About Critical Race Theory and the 1619 Project Right Now?

The term critical race theory began gaining traction in the mainstream two years ago – or notoriety depending on people's outlook – after The New York Times published the 1619 Project , a compilation of essays, commentaries and poems that brought the idea of critical race theory out of academia for the first time by asking readers to center the consequences of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans in the country's national narrative.

The project's orchestrator, Nikole Hannah-Jones, won a Pulitzer Prize for the moving personal essay she wrote – the introduction to the package – about her father, a veteran, and why he flew an American flag in their front yard and was proud to be American when what she saw as a little girl was a country that used and then abandoned him.

While the project was widely hailed, it also irked many people who argued that it put ideology before historical accuracy, as well as a handful of prominent academic scholars who challenged some of the package's guiding principles, including that colonists fought the Revolutionary War in order to preserve slavery and that slavery was a uniquely American enterprise.

Political conservatives in particular found the darker portrayal of America's origins and its shortcomings galling, saying that it undercut patriotism and had a divisive effect. Former President Donald Trump found it especially insulting.

"Critical race theory, the 1619 Project and the crusade against American history is toxic propaganda, ideological poison, that, if not removed, will dissolve the civic bonds that tie us together, will destroy our country," he said about it at the time.

Months following the 1619 Project's publication, Trump convened the "1776 Commission" to counter the narrative and develop a "patriotic" curriculum that schools can use to teach U.S. history. The commission published a 41-page report two days before the end of the Trump administration, which concluded, among other things, that progressivism is at odds with American values and recommended that schools teach positive stories about the country's founders.

President Joe Biden disassembled the 1776 Commision on his first day in office and repealed the executive order that pushed schools to adopt the former president's so-called patriotic curriculum, which had unlikely legs anyway, given that under federal law the government is prohibited from setting curriculum or persuading states and local school districts to adopt certain curricula.

Two months later, the Biden administration's Education Department published in its federal register a new proposal to prioritize federal grants for history to proposals that incorporate diverse perspectives. Specifically, the federal register stated: "Projects That Incorporate Racially, Ethnically, Culturally, and Linguistically Diverse Perspectives into Teaching and Learning."

The department includes as an example the 1619 Project's connection to the "growing acknowledgment of the importance of including, in the teaching and learning of our country's history, both the consequences of slavery, and the significant contributions of Black Americans to our society."

For Biden, whose vice president, Kamala Harris, is the first Black person to assume the role and whose Cabinet and high-ranking White House officials include more people of color than any previous administration, the move was more than just symbolic, especially coming on the heels of mass protests over systemic racism and inequality and a pandemic that exacerbated those realities.

What's at Stake, Politically, With Critical Race Theory?

Federal register notices hardly get attention, but congressional Republicans pounced on the item and accused the Biden administration of pushing a divisive and revisionist U.S. history curriculum on schools – though that's not what the federal register notice proposed since the federal government cannot interfere with school curriculum.

In a letter addressed to Education Secretary Miguel Cardona and signed by Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky and 36 of his Republican colleagues, McConnell argued the Biden administration's efforts are akin to "spoon-feeding students a slanted story."

"Americans do not need or want their tax dollars diverted from promoting the principles that unite our nation toward promoting radical ideologies meant to divide us," McConnell wrote. "Our nation's youth do not need activist indoctrination that fixates solely on past flaws and splits our nation into divided camps. Taxpayer-supported programs should emphasize the shared civic virtues that bring us together, not push radical agendas that tear us apart."

The ping-ponging debate over the foundation of America and how it should be taught in schools comes at a time of national reckoning over the impact of systemic racism and inequality borne out of the country's history of slavery, as well as at moment of legitimate crisis in civics education.

Recent surveys have shown that barely half of Americans can name the three branches of government and that most would earn an "F" on the U.S. citizenship exam. The most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress found that just 15% of eighth-graders are proficient in U.S. history.

Those critical of the push for states and school districts to emphasize a view of U.S. history that examines more deeply the generational impacts of some of the country's ugliest moments argue that it amounts to revisionism and promotes division, negativity and shame in identifying as American. Instead, they say, now is a moment to strengthen the traditional U.S. history curriculum.

Meanwhile, advocates for a reimagined teaching of U.S. history argue that embracing the hard lessons will better equip students to strive for the ideals of democracy on which the country was founded.

When Cardona testified before the House Appropriations Committee last month about the administration's budget request, Republicans grilled him on the proposal in the federal register.

"It's effectively, in my view, jeopardizing civics as a bipartisan priority," said Rep. Tom Cole, Oklahoma Republican who introduced bipartisan legislation with Rep. Rosa DeLauro, Connecticut Democrat, to provide $1 billion in federal aid for civics education.

Cardona told Cole and his Republican colleagues that the Education Department will play no role in setting curriculum but that it's important for students to be able to see themselves and their heritage in the history they learn – a mantra he's repeated in weeks since.

"Students should always see themselves in curriculum," he said.

But the secretary's promises proved not convincing enough. In recent weeks, at least 20 attorneys general co-authored a letter to Cardona that said the federal register proposal would impose "deeply flawed and controversial teachings" on schools and teachers, and a growing number of Republican-controlled states are passing laws prohibiting schools from teaching critical race theory and the 1619 Project.

Where Does Critical Race Theory Go From Here?

Critical race theory is proving to be more than simply the latest and greatest culture war Republicans are using to bolster their base – see here, also, state laws banning transgender athletes from participating in school sports.

Instead of fizzling after a month in national headlines, the issue continues to motivate and energize conservative voters in ways other hot-button topics have not. And its staying power is likely getting a boost from the simultaneous debate over reopening schools for in-person learning amid the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, which itself has exposed major racial gaps .

In one powerful sign that Republicans will likely propel their opposition of critical race theory into a 2022 campaign issue, it's motivating some conservative parents – again, alongside their support for reopening schools full time – to run for school board seats and drawing a lot of grassroots support.

In fact, a new political action committee, called the "1776 Project," which launched last month, plans to focus on school board races in North Carolina and Florida in hopes of building momentum.

"Help us overturn any teaching of the 1619 Project or critical race theory," its website reads. "Let's bring back Patriotism and Pride in our American History."

Meanwhile, a bill that would provide reparations to descendants of slaves moves through Congress, the president's Cabinet makes a top-to-bottom examination of federal policies and laws that handicap Black people and other racial and enthinic minorities, and Biden himself elevates the Tulsa race massacre to convey its lasting repercussions.

"The Federal Government must reckon with and acknowledge the role that it has played in stripping wealth and opportunity from Black communities," Biden said in Monday's proclamation, before asking the country to "commit together to eradicate systemic racism and help to rebuild communities and lives that have been destroyed by it."

Join the Conversation

Tags: education policy , K-12 education , education reform , race , racism , history , The Racial Divide

America 2024

Health News Bulletin

Stay informed on the latest news on health and COVID-19 from the editors at U.S. News & World Report.

Sign in to manage your newsletters »

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

You May Also Like

The 10 worst presidents.

U.S. News Staff Feb. 23, 2024

Cartoons on President Donald Trump

Feb. 1, 2017, at 1:24 p.m.

Photos: Obama Behind the Scenes

April 8, 2022

Photos: Who Supports Joe Biden?

March 11, 2020

Florida High Court OKs Abortion Vote

Lauren Camera April 1, 2024

The Week in Cartoons April 1-5

April 1, 2024, at 3:48 p.m.

White House Easter Egg Roll

April 1, 2024

What to Know About the Easter Egg Roll

Steven Ross Johnson April 1, 2024

Jobs Back on the Radar to Start Q2

Tim Smart April 1, 2024

Biden Besting Trump in Campaign Cash

Susan Milligan and Lauren Camera March 29, 2024

Anti-Critical-Race-Theory Laws Are Slowing Down. Here Are 3 Things to Know

- Share article

Is it the beginning of the end of “anti-critical race theory” legislation?

Starting in 2021, state lawmakers introduced a wave of such proposals, many modeled off a 2020 executive order signed by then-President Trump forbidding federal employees from receiving training on a number of “divisive concepts,” including the idea that any race was inherently superior to another, or that individuals should bear guilt for things that happened in the past. Some of these bills explicitly name-checked critical race theory—an academic framework for analyzing structural racism in law and policy.

Education Week recently updated its ongoing tracker of these laws , and concluded the pace of newly introduced legislation has slowed. The organization has counted just 10 bills that would affect K-12 education so far in 2024, of which two have passed.

Analysts from the National Conference of State Legislatures who track trends in state-level proposals said their data generally matched EdWeek’s, and that momentum on this topic seems to have flagged.

But other issues around what schools can teach or discuss have replaced the interest in “divisive concepts” and critical race theory, including “parents’ rights” bills allowing parents to withdraw their children from lessons they object to; bills that specifically take aim at gender identity or students’ use of pronouns; and bills that aim to restrict library materials and other curriculum content. (EdWeek’s bill tracker does not look at those topics.)

Some analysts see the slowdown on critical race theory legislation as a sign of fatigue with this element of the ongoing battle over who should shape curriculum.

“There’s only 50 states and only a subset that are sort of safe Republican ones where politicians can vote for these without worrying about being held politically accountable, so it can’t keep going forever,” noted Jeffrey Henig, a professor of political science and education at Teachers College, Columbia University. “You can only signal-call so long, so it’s not that surprising that once people have done their pass and proven themselves to the true believers in their largely solid, gerrymandered, state-legislated districts, things would run out of steam in some way.”

It’s also possible, he said, that the wave of headlines about book restrictions and attacks on librarians have brought some of these issues home locally in ways that have made some constituents uncomfortable.

Here are three things to know about where states stand on these anti-critical race theory laws.

1. Action seems concentrated in a handful of states

So far, no state that had not already considered such a proposal in prior years has seen a lawmaker introduce one in the 2024 legislative cycle. Overall, 44 states have considered legislation or regulations to curb how issues of race and gender can be taught since 2021, and 18 of them have enacted policy.

Most of the 2024 legislation has been introduced in states where previous proposals have failed to pass. Missouri lawmakers, for example, have introduced four bills this year that would variously prohibit the teaching of certain “divisive concepts” related to gender and race, prohibit the teaching of The New York Times’ 1619 Project—an exploration of slavery’s role in shaping American policy—and prohibit teachers from requiring students to create projects that compel students to lobby or engage in activism on specific policies or social issues, among other things. The state had some 20 bills on these same topics in 2023, none of which passed.

Two new laws have passed so far in 2024, in Alabama and Utah—expanding restrictions those states already had on the books (see No. 3, below).

2. Already-passed laws are here to stay—for now

The 2024 session also brought an early test of these laws’ durability.

In New Hampshire, Democrats attempted to strike statutory language added as part of a 2021 budget law that forbids teachers from teaching about gender and race in specific ways. But on March 14, lawmakers voted 192-183, largely along party lines, to indefinitely postpone the bill, effectively killing it.

Attempts to undo the laws could come through the courts. Lawsuits from various combinations of parents, teachers, students, teachers’ unions, and civil rights organizations have been filed in at least six states— Arizona , Arkansas, Florida, Oklahoma , New Hampshire, and Tennessee. The lawsuits generally allege that the laws are impermissibly vague and violate students’ and teachers’ rights to free speech or due process.

The latest lawsuit, filed just this week by two students and their teacher in Little Rock, Ark., takes aim at that state’s executive order and legislation that forbid “teaching that would indoctrinate students with ideologies,” including critical race theory. State officials had cited those rules when determining that the newly developed AP African American Studies course would not count for credit .

3. A few new laws suggest a pivot toward targeting DEI programs

Two newer laws signed this year suggest that diversity, equity, and inclusion, or DEI, programs could be the latest target.

These anti-DEI laws gained traction after the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling last year that bans affirmative action in college admissions, and appear to be aimed mainly at higher education institutions. But several would also prohibit DEI efforts in K-12 schools and districts.

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey signed a law that prohibits public universities and schools from sponsoring any diversity, equity, and inclusion program or maintaining a DEI office, or from requiring students or faculty to attend training or affirm the “divisive concepts” the state already had forbidden from teaching.

Similarly, Utah Gov. Spencer Cox in January signed a law aimed mainly at public colleges and universities but also covers other state institutions, including public schools. It prohibits districts from training staff or students on “discriminatory practices,” including any that rely on personal identity characteristics as a marker of moral character, promote resentment, or assert that an individual is inherently privileged or oppressed, among other things. And it prohibits districts from establishing an office, division, or employee who coordinates activities related to those practices.

Here, too, Henig sees the possibility of overreach.

“People’s attitudes about Harvard and Columbia and Penn as these elite, distanced institutions are different if it starts playing out at Michigan State and your local community college,” he said. “I think there’s some of that same friction when it comes closer to home.”

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Should college essays touch on race? Some say affirmative action ruling leaves them no choice

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

When she started writing her college essay, Hillary Amofa told the story she thought admissions offices wanted to hear. About being the daughter of immigrants from Ghana and growing up in a small apartment in Chicago. About hardship and struggle.

Then she deleted it all.

“I would just find myself kind of trauma-dumping,” said the 18-year-old senior at Lincoln Park High School in Chicago. “And I’m just like, this doesn’t really say anything about me as a person.”

When the Supreme Court ended affirmative action in higher education , it left the college essay as one of few places where race can play a role in admissions decisions. For many students of color, instantly more was riding on the already high-stakes writing assignment. Some say they felt pressure to exploit their hardships as they competed for a spot on campus.

Supreme Court strikes down race-based affirmative action in college admissions

In another major reversal, the Supreme Court forbids the use of race as an admissions factor at colleges and universities.

June 29, 2023

Amofa was just starting to think about her essay when the court issued its decision, and it left her with a wave of questions. Could she still write about her race? Could she be penalized for it? She wanted to tell colleges about her heritage but she didn’t want to be defined by it.

In English class, Amofa and her classmates read sample essays that all seemed to focus on some trauma or hardship. It left her with the impression she had to write about her life’s hardest moments to show how far she’d come. But she and some classmates wondered if their lives had been hard enough to catch the attention of admissions offices.

This year’s senior class is the first in decades to navigate college admissions without affirmative action. The Supreme Court upheld the practice in decisions going back to the 1970s, but this court’s conservative supermajority found it is unconstitutional for colleges to give students extra weight because of their race alone.

Still, the decision left room for race to play an indirect role: Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. wrote that universities can still consider how an applicant’s life was shaped by their race, “so long as that discussion is concretely tied to a quality of character or unique ability.”

Scores of colleges responded with new essay prompts asking about students’ backgrounds.

Post-affirmative action, Asian American families are more stressed than ever about college admissions

Parents who didn’t grow up in the American system, and who may have moved to the U.S. in large part for their children’s education, feel desperate and in-the-dark. Some shell out tens of thousands of dollars for consultants as early as junior high.

Nov. 26, 2023

When Darrian Merritt started writing his essay, his first instinct was to write about events that led to him going to live with his grandmother as a child. Those were painful memories, but he thought they might play well at schools like Yale, Stanford and Vanderbilt.

“I feel like the admissions committee might expect a sob story or a tragic story,” said Merritt, a senior in Cleveland. “I wrestled with that a lot.”

Eventually he abandoned the idea and aimed for an essay that would stand out for its positivity.

Merritt wrote about a summer camp where he started to feel more comfortable in his own skin. He described embracing his personality and defying his tendency to please others. But the essay also reflects on his feelings of not being “Black enough” and being made fun of for listening to “white people music.”

Like many students, Max Decker of Portland, Ore., had drafted a college essay on one topic, only to change direction after the Supreme Court ruling in June.

Decker initially wrote about his love for video games. In a childhood surrounded by constant change, navigating his parents’ divorce, the games he took from place to place on his Nintendo DS were a source of comfort.

‘We’re really worried’: What do colleges do now after affirmative action ruling?

The Supreme Court’s ban on affirmative action has triggered angst on campuses about how to promote diversity without considering race in admissions decisions.

But the essay he submitted to colleges focused on the community he found through Word Is Bond, a leadership group for young Black men in Portland.

As the only biracial, Jewish kid with divorced parents in a predominantly white, Christian community, Decker wrote he felt like the odd one out. On a trip with Word Is Bond to Capitol Hill, he and friends who looked just like him shook hands with lawmakers. The experience, he wrote, changed how he saw himself.

“It’s because I’m different that I provide something precious to the world, not the other way around,” wrote Decker, whose top college choice is Tulane in New Orleans because of the region’s diversity.

Amofa used to think affirmative action was only a factor at schools like Harvard and Yale. After the court’s ruling, she was surprised to find that race was taken into account even at public universities she was applying to.

Now, without affirmative action, she wondered if mostly white schools will become even whiter.

A lot of what you’ve heard about affirmative action is wrong

Debate leading up to the Supreme Court’s decision has stirred up plenty of misconceptions. We break down the myths and explain the reality.

It’s been on her mind as she chooses between Indiana University and the University of Dayton, both of which have relatively few Black students. When she was one of the only Black students in her grade school, she could fall back on her family and Ghanaian friends at church. At college, she worries about loneliness.

“That’s what I’m nervous about,” she said. “Going and just feeling so isolated, even though I’m constantly around people.”

The first drafts of her essay didn’t tell colleges about who she is now, she said. Her final essay describes how she came to embrace her natural hair. She wrote about going to a mostly white grade school where classmates made jokes about her afro.

Over time, she ignored their insults and found beauty in the styles worn by women in her life. She now runs a business doing braids and other hairstyles in her neighborhood.

“Criticism will persist,” she wrote “but it loses its power when you know there’s a crown on your head!”

Collin Binkley, Annie Ma and Noreen Nasir write for the Associated Press. Binkley and Nasir reported from Chicago and Ma from Portland, Ore.

More to Read

Editorial: Early decision admissions for college unfairly favor wealthy students

Jan. 4, 2024

HBCUs brace for flood of applications after Supreme Court affirmative action decision

Sept. 22, 2023

Opinion: In a post-affirmative action world, employers should learn from California’s experience

Sept. 16, 2023

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Voters approved more arts money for schools. Powerful unions allege funds are being misused

April 1, 2024

Exhausted, hungry and sleep-deprived: UCLA student super-commuters search for relief

Former official pleads guilty to embezzling nearly $16 million from O.C. school district

March 29, 2024

Is your child struggling to master the potty? These 5 takeaways from our panel can help

March 28, 2024

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Critical race theory, intellectual and social movement and framework of legal analysis based on the premise that race is a socially constructed category that is used to oppress and exploit people of color. Critical race theorists hold that racism is inherent in the law and legal institutions of the United States.

Critical race theory is an academic concept that is more than 40 years old. The core idea is that race is a social construct, and that racism is not merely the product of individual bias or ...

But critical race theory is not a single worldview; the people who study it may disagree on some of the finer points. As Professor Crenshaw put it, C.R.T. is more a verb than a noun. "It is a ...

A Lesson on Critical Race Theory. In September 2020, President Trump issued an executive order excluding from federal contracts any diversity and inclusion training interpreted as containing "Divisive Concepts," "Race or Sex Stereotyping," and "Race or Sex Scapegoating.". Among the content considered "divisive" is Critical Race ...