Essays About Religion: Top 5 Examples and 7 Writing Prompts

Essays about religion include delicate issues and tricky subtopics. See our top essay examples and prompts to guide you in your essay writing.

With over 4,000 religions worldwide, it’s no wonder religion influences everything. It involves faith, lessons on humanity, spirituality, and moral values that span thousands of years. For some, it’s both a belief and a cultural system. As it often clashes with science, laws, and modern philosophies, it’s also a hot debate topic. Religion is a broad subject encompassing various elements of life, so you may find it a challenging topic to write an essay about it.

1. Wisdom and Longing in Islam’s Religion by Anonymous on Ivypanda.com

2. consequences of following religion blindly essay by anonymous on ivypanda.com, 3. religion: christians’ belief in god by anonymous on ivypanda.com, 4. mecca’s influence on today’s religion essay by anonymous on ivypanda.com, 5. religion: how buddhism views the world by anonymous on ivypanda.com , 1. the importance of religion, 2. pros and cons of having a religion, 3. religions across the world, 4. religion and its influence on laws, 5. religion: then and now, 6. religion vs. science, 7. my religion.

“Portraying Muslims as radical religious fanatics who deny other religions and violently fight dissent has nothing to do with true Islamic ideology. The knowledge that is presented in Islam and used by Muslims to build their worldview system is exploited in a misinterpreted form. This is transforming the perception of Islam around the world as a radical religious system that supports intolerance and conflicts.”

The author discusses their opinion on how Islam becomes involved with violence or terrorism in the Islamic states. Throughout the essay, the writer mentions the massive difference between Islam’s central teachings and the terrorist groups’ dogma. The piece also includes a list of groups, their disobediences, and punishments.

This essay looks at how these brutalities have nothing to do with Islam’s fundamental ideologies. However, the context of Islam’s creeds is distorted by rebel groups like The Afghan mujahideen, Jihadis, and Al-Qa’ida. Furthermore, their activities push dangerous narratives that others use to make generalized assumptions about the entire religion. These misleading generalizations lead to misunderstandings amongst other communities, particularly in the western world. However, the truth is that these terrorist groups are violating Islamic doctrine.

“Following religion blindly can hinder one’s self-actualization and interfere with self-development due to numerous constraints and restrictions… Blind adherence to religion is a factor that does not allow receiving flexible education and adapting knowledge to different areas.”

The author discusses the effects of blindly following a religion and mentions that it can lead to difficulties in self-development and the inability to live independently. These limitations affect a person’s opportunity to grow and discover oneself. Movies like “ The Da Vinci Code ” show how fanatical devotion influences perception and creates constant doubt.

“…there are many religions through which various cultures attain their spiritual and moral bearings to bring themselves closer to a higher power (deity). Different religions are differentiated in terms of beliefs, customs, and purpose and are similar in one way or the other.”

The author discusses how religion affects its followers’ spiritual and moral values and mentions how deities work in mysterious ways. The essay includes situations that show how these supreme beings test their followers’ faith through various life challenges. Overall, the writer believes that when people fully believe in God, they can be stronger and more capable of coping with the difficulties they may encounter.

“Mecca represents a holy ground that the majority of the Muslims visit; and is only supposed to be visited by Muslims. The popularity of Mecca has increased the scope of its effects, showing that it has an influence on tourism, the financial aspects of the region and lastly religion today.”

The essay delves into Mecca’s contributions to Saudi Arabia’s tourism and religion. It mentions tourism rates peaking during Hajj, a 5-day Muslim pilgrimage, and visitors’ sense of spiritual relief and peace after the voyage. Aside from its tremendous touristic benefits, it also brings people together to worship Allah. You can also check out these essays about values and articles about beliefs .

“Buddhism is seen as one of the most popular and widespread religions on the earth the reason of its pragmatic and attractive philosophies which are so appealing for people of the most diversified backgrounds and ways of thinking .”

To help readers understand the topic, the author explains Buddhism’s worldviews and how Siddhatta Gotama established the religion that’s now one of the most recognized on Earth. It includes teachings about the gift of life, novel thinking, and philosophies based on his observations. Conclusively, the author believes that Buddhism deals with the world as Gotama sees it.

Check out our guide packed full of transition words for essays .

7 Prompts on Essays About Religion

Religion’s importance is embedded in an individual or group’s interpretation of it. They hold on to their faith for various reasons, such as having an idea of the real meaning of life and offering them a purpose to exist. Use this prompt to identify and explain what makes religion a necessity. Make your essay interesting by adding real-life stories of how faith changed someone’s life.

Although religion offers benefits such as positivity and a sense of structure, there are also disadvantages that come with it. Discuss what’s considered healthy and destructive when people follow their religion’s gospels and why. You can also connect it to current issues. Include any personal experience you have.

Religion’s prevalence exhibits how it can significantly affect one’s daily living. Use this prompt to discuss how religions across the world differ from one another when it comes to beliefs and if traditions or customs influence them. It’s essential to use relevant statistical data or surveys in this prompt to support your claims and encourage your readers to trust your piece.

There are various ways religion affects countries’ laws as they adhere to moral and often humanitarian values. Identify each and discuss how faith takes part in a nation’s decision-making regarding pressing matters. You can focus on one religion in a specific location to let the readers concentrate on the case. A good example is the latest abortion issue in the US, the overturning of “Wade vs. Roe.” Include people’s mixed reactions to this subject and their justifications.

In this essay, talk about how the most widespread religions’ principles or rituals changed over time. Then, expound on what inspired these changes. Add the religion’s history, its current situation in the country, and its old and new beliefs. Elaborate on how its members clash over these old and new principles. Conclude by sharing your opinion on whether the changes are beneficial or not.

There’s a never-ending debate between religion and science. List the most controversial arguments in your essay and add which side you support and why. Then, open discourse about how these groups can avoid quarreling. You can also discuss instances when religion and science agreed or worked together to achieve great results.

Use this prompt if you’re a part of a particular religion. Even if you don’t believe in faith, you can still take this prompt and pick a church you’ll consider joining. Share your personal experiences about your religion. Add how you became a follower, the beliefs that helped you through tough times, and why you’re staying as an active member in it. You can also speak about miraculous events that strengthen your faith. Or you can include teachings that you disagree with and think needs to be changed or updated.

For help with your essay, check out our top essay writing tips !

Maria Caballero is a freelance writer who has been writing since high school. She believes that to be a writer doesn't only refer to excellent syntax and semantics but also knowing how to weave words together to communicate to any reader effectively.

View all posts

The Christian Perspective on Other Religions: What You Need to Know

Welcome to our article on The Christian Perspective on Other Religions . In this post, we will explore the views of Christianity towards other religions and provide you with a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Religious pluralism is becoming increasingly prevalent in our modern world. With many different beliefs and practices, it can be challenging to understand how Christianity fits into the larger religious landscape. Our goal is to provide clarity on the topic and help you understand the Christian perspective.

Throughout this article, we will explore the biblical basis for exclusive Christianity , common misconceptions and stereotypes, and how to engage with people of different beliefs. By the end of this post, you will have a better understanding of Christianity’s relationship with other religions and be equipped to navigate interfaith dialogue with respect and understanding.

Join us on this journey to explore the Christian perspective on other religions and gain insights into how we can foster interfaith dialogue and understanding in our increasingly diverse world.

Understanding Religious Pluralism

Religious pluralism is the belief that multiple religions can coexist and be equally valid. This view acknowledges that there are many ways to approach spirituality, and that no one religion has a monopoly on truth. Diversity is at the heart of religious pluralism, as it allows for the expression of different beliefs and practices.

However, not everyone agrees with this perspective. Some people hold to the belief that their religion is the only true path to salvation or enlightenment. This exclusivist approach can lead to tension and conflict between different religious groups. It’s important to note that there are many different forms of exclusivism, and not all of them are necessarily hostile to other faiths.

Another important concept to consider in the context of religious pluralism is tolerance . Tolerance involves respecting the beliefs and practices of others, even if they differ from our own. This doesn’t mean that we have to agree with everything that other religions teach, but it does require us to treat others with kindness and understanding.

Finally, it’s worth noting that religious pluralism can take many different forms. Some people advocate for a more syncretistic approach, where different beliefs are blended together to create a new religious tradition. Others prefer a more ecumenical approach, where different religious groups work together to find common ground and promote understanding.

Overall, understanding religious pluralism is key to engaging with people of different faiths and building a more inclusive society. By recognizing the value of diversity, practicing tolerance, and embracing different forms of pluralism, we can work towards a world where all religions are valued and respected.

The Definition of Religious Pluralism

Religious pluralism refers to the coexistence of multiple religious beliefs and practices within a society. It recognizes that different religions offer unique perspectives and paths to understanding the divine or ultimate reality. Rather than seeing diversity as a problem, religious pluralism embraces it as a positive aspect of human experience.

One key aspect of religious pluralism is tolerance . This involves acknowledging and respecting differences between religions, and recognizing the right of individuals to practice their own faith. Tolerance does not mean agreeing with or accepting all beliefs, but rather creating an environment where people can live together peacefully despite their differences.

Another important element of religious pluralism is dialogue . This involves engaging in meaningful conversations between people of different faiths, with the aim of understanding each other better and finding common ground. Dialogue can help break down stereotypes and prejudices, and foster a sense of community and shared humanity.

Pluralism is often contrasted with exclusivism , which holds that only one religion or belief system is true, and others are mistaken or false. Pluralism recognizes the validity and value of multiple paths to understanding the divine, while exclusivism asserts the superiority of one path over all others.

The Different Types of Religious Pluralism

Religious pluralism is the belief that multiple religions can coexist harmoniously within a society. This idea has become increasingly relevant as our global society has become more diverse, with people from various backgrounds and belief systems interacting more frequently. There are different types of religious pluralism that people adhere to, each with its own unique perspective on how religions can and should coexist. Inclusivism, exclusivism, relativism, and particularism are four words relevant to this topic that we will explore further below.

Inclusivism is often seen as a more tolerant and accepting approach to religious pluralism, while exclusivism is seen as more rigid and exclusive. Relativism is a more neutral approach that does not take a stance on the validity or truth of any religion, while particularism falls somewhere in between inclusivism and exclusivism.

While these different types of religious pluralism provide a framework for understanding how people view the coexistence of religions, they are not the only perspectives. People’s beliefs and attitudes towards religious pluralism are shaped by a variety of factors, including cultural background, personal experiences, and religious teachings. Ultimately, how religions coexist within a society depends on the attitudes and actions of the people who practice them.

In conclusion, religious pluralism is a complex topic that involves different beliefs and attitudes towards the coexistence of multiple religions. Inclusivism, exclusivism, relativism, and particularism are four words that describe some of the different perspectives on religious pluralism. Understanding these perspectives can help us navigate the diversity of our global society and promote greater understanding and tolerance among people of different backgrounds and beliefs.

Biblical Basis for Exclusive Christianity

Exclusive Christianity is a belief that only those who accept Jesus Christ as their Lord and Savior will attain salvation. This belief is based on the biblical teaching that Jesus is the only way to God. John 14:6 states, “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.” This verse makes it clear that salvation is exclusive to those who accept Jesus as the way to God.

Furthermore, the Bible teaches that salvation is a gift from God and cannot be earned through good works or adherence to religious practices. Ephesians 2:8-9 states, “For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith—and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God—not by works, so that no one can boast.” This means that salvation is not dependent on one’s actions, but rather on one’s belief in Jesus Christ.

Another biblical basis for exclusive Christianity is the concept of sin. The Bible teaches that all humans have sinned and fall short of the glory of God (Romans 3:23). Therefore, all humans are in need of salvation, which can only be attained through faith in Jesus Christ. Acts 4:12 states, “Salvation is found in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given to mankind by which we must be saved.”

Salvation through Christ Alone

Salvation through Christ alone is a fundamental belief of Christianity. This belief is based on the biblical teaching that Jesus is the only way to attain salvation. There are several reasons why Christians believe in salvation through Christ alone.

Firstly, the Bible teaches that all humans have sinned and fall short of the glory of God (Romans 3:23). As a result, all humans are in need of salvation. The only way to attain salvation is through faith in Jesus Christ. Acts 16:31 states, “Believe in the Lord Jesus, and you will be saved—you and your household.” This verse makes it clear that salvation is only possible through belief in Jesus.

Secondly, Jesus himself taught that he was the only way to God. John 10:9 states, “I am the gate; whoever enters through me will be saved.” This statement by Jesus reinforces the idea that salvation is exclusive to those who believe in him.

Lastly, Christians believe in salvation through Christ alone because it is a gift from God. Ephesians 2:8-9 states, “For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith—and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God—not by works, so that no one can boast.” This means that salvation is not something that can be earned, but rather it is a gift that is given to those who believe in Jesus Christ.

The Uniqueness of Jesus in Christianity

One of the most distinctive beliefs of Christianity is the centrality of Jesus . Unlike other religions, Christianity asserts that Jesus is not just a prophet or teacher, but the Son of God who came to earth to save humanity from sin.

There are several ways in which Jesus is unique in Christianity. First, his miraculous virgin birth sets him apart from any other religious figure. According to the Bible, Jesus was conceived by the Holy Spirit and born of a virgin named Mary.

Second, Jesus’ teachings and life are considered to be a perfect example for Christians to follow. His love, compassion, and sacrifice serve as a model for how Christians should live their lives.

Finally, Jesus’ death and resurrection are the cornerstones of the Christian faith. Through his death on the cross, Jesus paid the penalty for humanity’s sin, making it possible for people to be reconciled with God. His resurrection from the dead three days later demonstrated his power over death and confirmed his divine nature.

The Role of Other Religions in God’s Plan

Religious Pluralism: Religious pluralism is a concept that acknowledges the existence of multiple religions and recognizes that there are different paths to God. While Christianity asserts that Jesus is the only way to God, other religions may hold different beliefs about how one attains salvation. According to religious pluralism, all religions offer a valid path to God.

Interfaith Dialogue: Interfaith dialogue refers to the process of engaging in conversations with members of other religions. The goal of interfaith dialogue is to build bridges of understanding between different faith communities, learn from one another, and work together to promote peace and justice in the world. Christians engage in interfaith dialogue as a way to live out their faith in the world and to love their neighbors as themselves.

Missionary Work: Despite recognizing the validity of other religions, Christians still hold that Jesus is the only way to God. Therefore, Christians engage in missionary work, which involves sharing the gospel message of Jesus Christ with people who have not yet heard it. Missionary work is done out of love and compassion for others, with the goal of helping people find true peace and fulfillment in a relationship with God.

Common Misconceptions and Stereotypes

One common misconception about religion is that it is always the root cause of violence and conflict. While it is true that religion has been a factor in some conflicts throughout history, it is often used as a cover for underlying political or economic motives.

Another stereotype is that all religious people are narrow-minded and intolerant of other beliefs. While there are certainly some individuals who hold such views, it is unfair to generalize an entire group based on the actions of a few.

Finally, there is a misconception that atheists are inherently immoral or lack a moral compass. This is simply not true. Many atheists have a strong moral code and live ethical lives, just as many religious people do.

Christianity as a Western Religion

One common misconception about Christianity is that it is a religion only for Westerners. While it is true that Christianity originated in the Middle East and spread primarily through Western Europe, it is now a global religion with followers in every part of the world. In fact, the majority of Christians today are found in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Another misconception is that Christianity is inherently connected to Western culture and values. While Christianity has undoubtedly had a profound impact on Western culture, it is important to recognize that Christianity has been practiced and interpreted in a variety of ways throughout history and across different cultures.

Finally, it is important to note that Christianity has often been used as a tool of colonialism and imperialism in the past, which has contributed to the perception that it is a Western religion. However, it is important to separate the actions of individuals and institutions from the teachings of Christianity itself, which emphasize love, justice, and compassion for all people.

Interfaith Dialogue and Respectful Coexistence

Interfaith dialogue is a vital component of promoting understanding and peaceful coexistence between different religions. It involves individuals from different faiths engaging in constructive conversations that seek to find common ground and build relationships based on mutual respect.

Respectful coexistence requires an acknowledgement of the diverse beliefs and practices of different religions. Rather than seeking to convert others to our own faith, we should strive to learn from each other and promote harmony through shared values such as compassion, justice, and kindness.

Effective interfaith dialogue and respectful coexistence can lead to positive social and political outcomes, including the reduction of religious tensions and conflicts. By embracing our differences and finding common ground, we can build a more peaceful and harmonious world.

The Importance of Interfaith Dialogue

Understanding is one of the main reasons why interfaith dialogue is important. It allows people from different religions to gain a deeper appreciation and understanding of each other’s beliefs and practices. It also helps to break down stereotypes and prejudices that may exist.

Interfaith dialogue also promotes peace and harmony among people of different faiths. When people have a better understanding of each other, it can lead to greater respect and tolerance. This, in turn, can help to reduce conflict and promote peaceful coexistence.

Learning is another key benefit of interfaith dialogue. By engaging in dialogue, people have the opportunity to learn about different cultures, traditions, and beliefs. This can broaden their perspective and enrich their own faith or worldview. It can also lead to new insights and ideas that can help to promote greater understanding and cooperation between different religious communities.

Respectful Coexistence among Different Beliefs

Respect is a fundamental aspect of coexistence among people with different beliefs. It means acknowledging the value and dignity of every person regardless of their beliefs, and treating them with kindness and compassion. When people of different beliefs interact with each other respectfully, it promotes mutual understanding, reduces conflicts, and strengthens social cohesion.

Tolerance is also crucial in fostering respectful coexistence among people of different beliefs. It means acknowledging and accepting that people have different beliefs, and not letting those differences be a source of animosity or conflict. It requires a willingness to listen to and learn from others, even if their beliefs differ from our own.

Dialogue is another essential component of respectful coexistence among people of different beliefs. Dialogue involves engaging in meaningful conversations, listening to each other’s perspectives, and seeking to understand each other better. Through dialogue, people can learn from each other, find common ground, and work towards building a more harmonious society.

Common Grounds among Religions

Love for fellow human beings is a shared value among many religions. The Golden Rule, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” is a teaching found in various religious texts.

Peace and justice are also common themes across religions. Many faiths encourage their followers to work for the betterment of society, promote social harmony, and pursue equality and fairness for all.

Spiritual practices and rituals are another area where religions often share similarities. Practices such as prayer, meditation, fasting, and pilgrimage are common across many faiths and serve as a means of connecting with the divine.

Despite the differences that exist between religions, there are many commonalities and shared values . Recognizing these commonalities and working to promote understanding and cooperation can help build bridges between different communities and foster a more peaceful and harmonious world.

Engaging with people of different beliefs can be a challenging yet rewarding experience. Here are some practical ways to do so:

Listen actively: When engaging with people of different beliefs, it’s essential to listen actively to what they have to say. Try to understand their perspective and beliefs before responding.

Show respect: Respect is crucial in any interfaith conversation. Treat others with the same respect you would like to receive, even if you disagree with their beliefs.

Be open-minded: Try to keep an open mind when engaging with people of different beliefs. Recognize that everyone has unique experiences and perspectives that shape their beliefs.

Remember, engaging with people of different beliefs is an opportunity to learn and grow. By listening actively, showing respect, and being open-minded, you can build bridges of understanding and foster greater harmony among diverse communities.

Building Genuine Relationships

Listening: One of the most important aspects of building genuine relationships with people of different beliefs is listening to their stories, experiences, and perspectives. This means being present, attentive, and respectful, and avoiding making assumptions or judgments.

Sharing: Building relationships is a two-way street, and it’s important to be willing to share your own beliefs, experiences, and perspectives with others. However, this should be done in a respectful and non-confrontational way, and with a genuine desire to learn from each other.

Engaging in Activities: Participating in activities or events that are important to people of different beliefs can also be a great way to build genuine relationships. This can include attending religious services, cultural events, or volunteering together for a common cause.

Active Listening and Mutual Learning

One of the most important aspects of engaging with people of different beliefs is active listening. It is essential to listen to others’ perspectives with an open mind and heart, without interrupting or judging them. Empathy is key to active listening, and it helps to put ourselves in others’ shoes to understand their point of view.

Mutual learning is another critical component of building relationships with people of different beliefs. It involves a willingness to learn from others’ experiences and knowledge, even if they differ from our own. Humility is essential to mutual learning, as it recognizes that we do not have all the answers and that others’ insights can enrich our understanding.

Active listening and mutual learning also require patience . It takes time to build trust and understanding, and we may encounter different perspectives that challenge our beliefs. However, by approaching these conversations with respect, curiosity, and a desire to learn, we can create meaningful connections with people of different faiths and cultures.

Collaborative Works for Common Good

Collaboration can be a powerful tool for building bridges between different faith communities. When people of diverse backgrounds come together and work towards a shared goal, it can create a sense of unity and understanding.

One way to engage in collaborative works is to participate in interfaith service projects . This can involve volunteering at a local charity, organizing a food drive, or participating in an environmental cleanup effort. Through working together, people can learn about each other’s values, beliefs, and customs while also making a positive impact on their community.

Another way to collaborate is through interfaith dialogue and education . By organizing events such as panel discussions, workshops, and seminars, individuals can learn from each other and gain a deeper understanding of different beliefs and practices. This can lead to a greater appreciation of diversity and a more respectful and harmonious society.

Finally, advocacy and activism can also be a way to work collaboratively towards a common goal. By advocating for issues such as social justice, human rights, and environmental protection, people of different faiths can unite in their commitment to making positive change in the world.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is christianity accepting of other religions.

Christianity recognizes the existence of other religions but holds the belief that Jesus Christ is the only way to salvation. Christians are encouraged to love and respect individuals from different religions and share the message of salvation through Christ with them.

Does Christianity view other religions as valid?

Christianity recognizes the positive aspects of other religions and respects their right to exist. However, Christianity believes that only through accepting Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior can one attain salvation and eternal life.

Can Christians learn from other religions?

Christians can learn from other religions by studying their beliefs and practices, as well as by engaging in interfaith dialogue. Christians can also gain insight into their own faith by learning about other religions and their perspectives on spirituality and morality.

How does Christianity view religious diversity?

Christianity recognizes that religious diversity exists in the world, and respects the right of individuals to practice their chosen religion. However, Christianity believes that all people are called to follow Jesus Christ and that He is the only way to eternal life.

Is evangelism a part of Christianity’s view on other religions?

Evangelism is a significant part of Christianity’s view on other religions, as Christians are called to share the message of salvation through Jesus Christ with others. This includes individuals who practice other religions, as Christians believe that everyone needs to hear the gospel message.

How does Christianity approach interfaith relations?

Christianity approaches interfaith relations with respect and a willingness to engage in dialogue. Christians believe that interfaith dialogue can lead to mutual understanding and can help to promote peace and harmony among different religions. However, Christians do not compromise their core beliefs and continue to hold the belief that Jesus Christ is the only way to salvation.

Privacy Overview

Essay on Different Religions

Students are often asked to write an essay on Different Religions in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Different Religions

Understanding religion.

Religion is a way of life for many people. It guides their actions, thoughts, and beliefs. Different religions exist because people in various parts of the world have unique ways of understanding life and its purpose.

Christianity

Christianity is a religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians believe in the Holy Bible. They think Jesus is the son of God, who came to earth to save humanity from sin.

Islam is a religion founded by Prophet Muhammad. Muslims, followers of Islam, believe in the Quran. They believe in one God, Allah, and that Muhammad is his prophet.

Hinduism is an ancient religion from India. Hindus believe in many gods and goddesses. They follow the teachings of sacred texts like the Vedas and the Bhagavad Gita.

Buddhism is a religion based on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, known as Buddha. Buddhists follow the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path to achieve enlightenment.

Judaism is a religion of the Jewish people. They believe in one God and follow the teachings of the Torah. Jews believe they have a special relationship with God, as his chosen people.

In conclusion, different religions have unique beliefs and practices. But, they all aim to guide people towards a purposeful life. It’s important to respect all religions, as they contribute to the diversity of human culture.

250 Words Essay on Different Religions

Understanding different religions.

Religion is a belief system that people follow. It helps them understand the world and how to live in it. There are many different religions around the world, each with its own ideas and practices.

Christianity is one of the largest religions in the world. It is based on the teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians believe in one God who is three persons: the Father, the Son (Jesus), and the Holy Spirit. They read the Bible, which is their holy book.

Islam is another big religion. Muslims, followers of Islam, believe in one God, Allah. They follow the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad. The Quran is their holy book. Muslims pray five times a day and fast during the month of Ramadan.

Hinduism is a major religion in India. Hindus believe in many gods and goddesses. Their holy books are the Vedas and the Upanishads. They believe in karma, which means your actions in this life will affect your next life.

Buddhism started in India, but it is now followed in many parts of the world. Buddhists follow the teachings of Buddha. They believe in reaching enlightenment, a state of peace and wisdom.

Judaism is one of the oldest religions. Jews believe in one God. Their holy book is the Torah. They have many special holidays, like Hanukkah and Passover.

In conclusion, each religion has its unique beliefs and practices. Even though they are different, all religions teach us to be good people and to respect others. Understanding different religions can help us respect and learn from each other.

500 Words Essay on Different Religions

Introduction to religions.

Religion is a special part of many people’s lives. It gives them a sense of purpose and helps them understand the world. There are many different religions across the globe. Each one has its own beliefs, practices, and traditions. Some of the major religions include Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Judaism.

Christianity is the most followed religion in the world. People who follow Christianity are known as Christians. They believe in Jesus Christ and consider him the son of God. They believe that Jesus died for the sins of all people and that belief in him leads to eternal life. The holy book of Christianity is the Bible. It includes the Old Testament and the New Testament.

Islam is the second largest religion in the world. People who follow Islam are called Muslims. They believe in one God, Allah, and that Muhammad is his prophet. Muslims follow the teachings of the Quran, their holy book. They have five important duties known as the Five Pillars of Islam. These include faith, prayer, charity, fasting, and pilgrimage to Mecca.

Hinduism is one of the oldest religions in the world. It originated in India. Hindus believe in many gods and goddesses. They also believe in reincarnation, which means the soul is reborn in a new body after death. The sacred texts of Hinduism are the Vedas and the Upanishads.

Buddhism started in India, but it is now followed in many parts of the world. Buddhists follow the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, also known as Buddha. They believe in a path of enlightenment through meditation, moral living, and wisdom. Buddhists do not believe in a personal god. Their sacred texts are called the Tripitaka.

Judaism is the religion of the Jewish people. It is one of the oldest religions in the world. Jews believe in one God who revealed himself through ancient prophets. The Torah is their most important holy book. It includes the first five books of the Bible.

In conclusion, there are many different religions in the world. Each one has its own unique beliefs and practices. While they may be different, all religions aim to provide guidance and a sense of purpose to their followers. It’s important to respect all religions, even if their beliefs are different from our own.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Diet And Nutrition

- Essay on Diet And Health

- Essay on Diarrhea

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Email Signup

Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology

World Religions Overview Essay

The Movement of Religion and Ecology: Emerging Field and Dynamic Force

Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim, Yale University

Originally published in the Routledge Handbook of Religion and Ecology

As many United Nations reports attest, we humans are destroying the life-support systems of the Earth at an alarming rate. Ecosystems are being degraded by rapid industrialization and relentless development. The data keeps pouring in that we are altering the climate and toxifying the air, water, and soil of the planet so that the health of humans and other species is at risk. Indeed, the Swedish scientist, Johan Rockstrom, and his colleagues, are examining which planetary boundaries are being exceeded. (Rockstrom and Klum, 2015)

The explosion of population from 3 billion in 1960 to more then 7 billion currently and the subsequent demands on the natural world seem to be on an unsustainable course. The demands include meeting basic human needs of a majority of the world’s people, but also feeding the insatiable desire for goods and comfort spread by the allure of materialism. The first is often called sustainable development; the second is unsustainable consumption. The challenge of rapid economic growth and consumption has brought on destabilizing climate change. This is coming into full focus in alarming ways including increased floods and hurricanes, droughts and famine, rising seas and warming oceans.

Can we turn our course to avert disaster? There are several indications that this may still be possible. On September 25, 2015 after the Pope addressed the UN General Assembly, 195 member states adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). On December 12, 2015 these same members states endorsed the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. Both of these are important indications of potential reversal. The Climate Agreement emerged from the dedicated work of governments and civil society along with business partners. The leadership of UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon and the Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, Christiana Figueres, and many others was indispensable.

One of the inspirations for the Climate Agreement and for the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals was the release of the Papal Encyclical, Laudato Si’ in June 2015. The encyclical encouraged the moral forces of concern for both the environment and people to be joined in “integral ecology”. “The cry of the Earth and the cry of the poor” are now linked as was not fully visible before. (Boff, 1997 and in the encyclical) Many religious and environmental communities are embracing this integrated perspective and will, no doubt, foster it going forward. The question is how can the world religions contribute more effectively to this renewed ethical momentum for change. For example, what will be their long-term response to population growth? As this is addressed in the article by Robert Wyman and Guigui Yao, we will not take it up here. Instead, we will consider some of the challenges and possibilities amid the dream of progress and the lure of consumption.

Challenges: The Dream of Progress and the Religion of Consumption

Consumption appears to have become an ideology or quasi-religion, not only in the West but also around the world. Faith in economic growth drives both producers and consumers. The dream of progress is becoming a distorted one. This convergence of our unlimited demands with an unquestioned faith in economic progress raises questions about the roles of religions in encouraging, discouraging, or ignoring our dominant drive toward appropriately satisfying material needs or inappropriately indulging material desires. Integral ecology supports the former and critiques the latter.

Moreover, a consumerist ideology depends upon and simultaneously contributes to a worldview based on the instrumental rationality of the human. That is, the assumption for decision-making is that all choices are equally clear and measurable. Market based metrics such as price, utility, or efficiency are dominant. This can result in utilitarian views of a forest as so much board feet or simply as a mechanistic complex of ecosystems that provide services to the human.

One long-term effect of this is that the individual human decision-maker is further distanced from nature because nature is reduced to measurable entities for profit or use. From this perspective we humans may be isolated in our perceived uniqueness as something apart from the biological web of life. In this context, humans do not seek identity and meaning in the numinous beauty of the world, nor do they experience themselves as dependent on a complex of life-supporting interactions of air, water, and soil. Rather, this logic sees humans as independent, rational decision-makers who find their meaning and identity in systems of management that now attempt to co-opt the language of conservation and environmental concern. Happiness is derived from simply creating and having more material goods. This perspective reflects a reading of our current geological period as human induced by our growth as a species that is now controlling the planet. This current era is being called the “Anthropocene” because of our effect on the planet in contrast to the prior 12,000 year epoch known as the Holocene.

This human capacity to imagine and implement a utilitarian-based worldview regarding nature has undermined many of the ancient insights of the world’s religious and spiritual traditions. For example, some religions, attracted by the individualistic orientations of market rationalism and short-term benefits of social improvement, seized upon material accumulation as containing divine sanction. Thus, Max Weber identified the rise of Protestantism with an ethos of inspirited work and accumulated capital.

Weber also identified the growing disenchantment from the world of nature with the rise of global capitalism. Karl Marx recognized the “metabolic rift” in which human labor and nature become alienated from cycles of renewal. The earlier mystique of creation was lost. Wonder, beauty, and imagination as ways of knowing were gradually superseded by the analytical reductionism of modernity such that technological and economic entrancement have become key inspirations of progress.

Challenges: Religions Fostering Anthropocentrism

This modern, instrumental view of matter as primarily for human use arises in part from a dualistic Western philosophical view of mind and matter. Adapted into Jewish, Christian and Islamic religious perspectives, this dualism associates mind with the soul as a transcendent spiritual entity given sovereignty and dominion over matter. Mind is often valued primarily for its rationality in contrast to a lifeless world. At the same time we ensure our radical discontinuity from it.

Interestingly, views of the uniqueness of the human bring many traditional religious perspectives into sync with modern instrumental rationalism. In Western religious traditions, for example, the human is seen as an exclusively gifted creature with a transcendent soul that manifests the divine image and likeness. Consequently, this soul should be liberated from the material world. In many contemporary reductionist perspectives (philosophical and scientific) the human with rational mind and technical prowess stands as the pinnacle of evolution. Ironically, religions emphasizing the uniqueness of the human as the image of God meet market-driven applied science and technology precisely at this point of the special nature of the human to justify exploitation of the natural world. Anthropocentrism in various forms, religious, philosophical, scientific, and economic, has led, perhaps inadvertently, to the dominance of humans in this modern period, now called the Anthropocene. (It can be said that certain strands of the South Asian religions have emphasized the importance of humans escaping from nature into transcendent liberation. However, such forms of radical dualism are not central to the East Asian traditions or indigenous traditions.)

From the standpoint of rational analysis, many values embedded in religions, such as a sense of the sacred, the intrinsic value of place, the spiritual dimension of the human, moral concern for nature, and care for future generations, are incommensurate with an objectified monetized worldview as they not quantifiable. Thus, they are often ignored as externalities, or overridden by more pragmatic profit-driven considerations. Contemporary nation-states in league with transnational corporations have seized upon this individualistic, property-based, use-analysis to promote national sovereignty, security, and development exclusively for humans.

Possibilities: Systems Science

Yet, even within the realm of so-called scientific, rational thought, there is not a uniform approach. Resistance to the easy marriage of reductionist science and instrumental rationality comes from what is called systems science and new ecoogy. By this we refer to a movement within empirical, experimental science of exploring the interaction of nature and society as complex dynamic systems. This approach stresses both analysis and synthesis – the empirical act of observation, as well as placement of the focus of study within the context of a larger whole. Systems science resists the temptation to take the micro, empirical, reductive act as the complete description of a thing, but opens analysis to the large interactive web of life to which we belong, from ecosystems to the biosphere. There are numerous examples of this holistic perspective in various branches of ecology. And this includes overcoming the nature-human divide. (Schmitz 2016) Aldo Leopold understood this holistic interconnection well when he wrote: “We abuse land because we see it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” (Leopold, 1966)

Collaboration of Science and Religion

Within this inclusive framework, scientists have been moving for some time beyond simply distanced observations to engaged concern. The Pope’s encyclical, Laudato Si , has elevated the level of visibility and efficacy of this conversation between science and religion as perhaps never before on a global level. Similarly, many other statements from the world religions are linking the wellbeing of people and the planet for a flourishing future. For example, the World Council of Churches has been working for four decades to join humans and nature in their program on Justice, Peace, and the Integrity of Creation.

Many scientists such as Thomas Lovejoy, E.O. Wilson, Jane Lubchenco, Peter Raven, and Ursula Goodenough recognize the importance of religious and cultural values when discussing solutions to environmental challenges. Other scientists such as Paul Ehrlich and Donald Kennedy have called for major studies of human behavior and values in relation to environmental issues. ( Science , July 2005) This has morphed into the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. (mahb.standford.edu). Since 2009 the Ecological Society of America has established an Earth Stewardship Initiative with yearly panels and publications. Many environmental studies programs are now seeking to incorporate these broader ethical and behavioral approaches into the curriculum.

Possibilities: Extinction and Religious Response

The stakes are high, however, and the path toward limiting ourselves within planetary boundaries is not smooth. Scientists are now reporting that because of the population explosion, our consuming habits, and our market drive for resources, we are living in the midst of a mass extinction period. This period represents the largest loss of species since the extinction of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago when the Cenozoic period began. In other words, we are shutting down life systems on the planet and causing the end of this large-scale geological era with little awareness of what we are doing or its consequences.

As the cultural historian Thomas Berry observed some years ago, we are making macrophase changes on the planet with microphase wisdom. Indeed, some people worry that these rapid changes have outstripped the capacity of our religions, ethics, and spiritualities to meet the complex challenges we are facing.

The question arises whether the wisdom traditions of the human community, embedded in institutional religions and beyond, can embrace integral ecology at the level needed? Can the religions provide leadership into a synergistic era of human-Earth relations characterized by empathy, regeneration, and resilience? Or are religions themselves the wellspring of those exclusivist perspectives in which human societies disconnect themselves from other groups and from the natural world? Are religions caught in their own meditative promises of transcendent peace and redemptive bliss in paradisal abandon? Or does their drive for exclusive salvation or truth claims cause them to try to overcome or convert the Other?

Authors in this volume are exploring these issues within religious and spiritual communities regarding the appropriate responses of the human to our multiple environmental and social challenges. What forms of symbolic visioning and ethical imagining can call forth a transformation of consciousness and conscience for our Earth community? Can religions and spiritualites provide vision and inspiration for grounding and guiding mutually enhancing human-Earth relations? Have we arrived at a point where we realize that more scientific statistics on environmental problems, more legislation, policy or regulation, and more economic analysis, while necessary, are no longer sufficient for the large-scale social transformations needed? This is where the world religions, despite their limitations, surely have something to contribute.

Such a perspective includes ethics, practices, and spiritualities from the world’s cultures that may or may not be connected with institutional forms of religion. Thus spiritual ecology and nature religions are an important part of the discussions and are represented in this volume. Our own efforts have focused on the world religions and indigenous traditions. Our decade long training in graduate school and our years of living and traveling throughout Asia and the West gave us an early appreciation for religions as dynamic, diverse, living traditions. We are keenly aware of the multiple forms of syncretism and hybridization in the world religions and spiritualties. We have witnessed how they are far from monolithic or impervious to change in our travels to more than 60 countries.

Problems and Promise of Religions

Several qualifications regarding the various roles of religion should thus be noted. First, we do not wish to suggest here that any one religious tradition has a privileged ecological perspective. Rather, multiple interreligious perspectives may be the most helpful in identifying the contributions of the world religions to the flourishing of life.

We also acknowledge that there is frequently a disjunction between principles and practices: ecologically sensitive ideas in religions are not always evident in environmental practices in particular civilizations. Many civilizations have overused their environments, with or without religious sanction.

Finally, we are keenly aware that religions have all too frequently contributed to tensions and conflict among various groups, both historically and at present. Dogmatic rigidity, inflexible claims of truth, and misuse of institutional and communal power by religions have led to tragic consequences in many parts of the globe.

Nonetheless, while religions have often preserved traditional ways, they have also provoked social change. They can be limiting but also liberating in their outlooks. In the twentieth century, for example, religious leaders and theologians helped to give birth to progressive movements such as civil rights for minorities, social justice for the poor, and liberation for women. Although the world religions have been slow to respond to our current environmental crises, their moral authority and their institutional power may help effect a change in attitudes, practices, and public policies. Now the challenge is a broadening of their ethical perspectives.

Traditionally the religions developed ethics for homicide, suicide, and genocide. Currently they need to respond to biocide, ecocide, and geocide. (Berry, 2009)

Retrieval, Reevaluation, Reconstruction

There is an inevitable disjunction between the examination of historical religious traditions in all of their diversity and complexity and the application of teachings, ethics, or practices to contemporary situations. While religions have always been involved in meeting contemporary challenges over the centuries, it is clear that the global environmental crisis is larger and more complex than anything in recorded human history. Thus, a simple application of traditional ideas to contemporary problems is unlikely to be either possible or adequate. In order to address ecological problems properly, religious and spiritual leaders, laypersons and academics have to be in dialogue with scientists, environmentalists, economists, businesspeople, politicians, and educators. Hence the articles in this volume are from various key sectors.

With these qualifications in mind we can then identify three methodological approaches that appear in the still emerging study of religion and ecology. These are retrieval, reevaluation, and reconstruction. Retrieval involves the scholarly investigation of scriptural and commentarial sources in order to clarify religious perspectives regarding human-Earth relations. This requires that historical and textual studies uncover resources latent within the tradition. In addition, retrieval can identify ethical codes and ritual customs of the tradition in order to discover how these teachings were put into practice. Traditional environmental knowledge (TEK) is an important part of this for all the world religions, especially indigenous traditions.

With reevaluation, traditional teachings are evaluated with regard to their relevance to contemporary circumstances. Are the ideas, teachings, or ethics present in these traditions appropriate for shaping more ecologically sensitive attitudes and sustainable practices? Reevaluation also questions ideas that may lead to inappropriate environmental practices. For example, are certain religious tendencies reflective of otherworldly or world-denying orientations that are not helpful in relation to pressing ecological issues? It asks as well whether the material world of nature has been devalued by a particular religion and whether a model of ethics focusing solely on human interactions is adequate to address environmental problems.

Finally, reconstruction suggests ways that religious traditions might adapt their teachings to current circumstances in new and creative ways. These may result in new syntheses or in creative modifications of traditional ideas and practices to suit modern modes of expression. This is the most challenging aspect of the emerging field of religion and ecology and requires sensitivity to who is speaking about a tradition in the process of reevaluation and reconstruction. Postcolonial critics have appropriately highlighted the complex issues surrounding the problem of who is representing or interpreting a religious tradition or even what constitutes that tradition. Nonetheless, practitioners and leaders of particular religions are finding grounds for creative dialogue with scholars of religions in these various phases of interpretation.

Religious Ecologies and Religious Cosmologies

As part of the retrieval, reevaluation, and reconstruction of religions we would identify “religious ecologies” and “religious cosmologies” as ways that religions have functioned in the past and can still function at present. Religious ecologies are ways of orienting and grounding whereby humans undertake specific practices of nurturing and transforming self and community in a particular cosmological context that regards nature as inherently valuable. Through cosmological stories humans narrate and experience the larger matrix of mystery in which life arises, unfolds, and flourishes. These are what we call religious cosmologies. These two, namely religious ecologies and religious cosmologies, can be distinguished but not separated. Together they provide a context for navigating life’s challenges and affirming the rich spiritual value of human-Earth relations.

Human communities until the modern period sensed themselves as grounded in and dependent on the natural world. Thus, even when the forces of nature were overwhelming, the regenerative capacity of the natural world opened a way forward. Humans experienced the processes of the natural world as interrelated, both practically and symbolically. These understandings were expressed in traditional environmental knowledge, namely, in hunting and agricultural practices such as the appropriate use of plants, animals, and land. Such knowledge was integrated in symbolic language and practical norms, such as prohibitions, taboos, and limitations on ecosystems’ usage. All this was based in an understanding of nature as the source of nurturance and kinship. The Lakota people still speak of “all my relations” as an expression of this kinship. Such perspectives will need to be incorporated into strategies to solve environmental problems. Humans are part of nature and their cultural and religious values are critical dimensions of the discussion.

Multidisciplinary approaches: Environmental Humanities

We are recognizing, then, that the environmental crisis is multifaceted and requires multidisciplinary approaches. As this book indicates, the insights of scientific modes of analytical and synthetic knowing are indispensable for understanding and responding to our contemporary environmental crisis. So also, we need new technologies such as industrial ecology, green chemistry, and renewable energy. Clearly ecological economics is critical along with green governance and legal policies as articles in this volume illustrate.

In this context it is important to recognize different ways of knowing that are manifest in the humanities, such as artistic expressions, historical perspectives, philosophical inquiry, and religious understandings. These honor emotional intelligence, affective insight, ethical valuing, and spiritual awakening.

Environmental humanities is a growing and diverse area of study within humanistic disciplines. In the last several decades, new academic courses and programs, research journals and monographs, have blossomed. This broad-based inquiry has sparked creative investigation into multiple ways, historically and at present, of understanding and interacting with nature, constructing cultures, developing communities, raising food, and exchanging goods.

It is helpful to see the field of religion and ecology as part of this larger emergence of environmental humanities. While it can be said that environmental history, literature, and philosophy are some four decades old, the field of religions and ecology began some two decades ago. It was preceded, however, by work among various scholars, particularly Christian theologians. Some eco-feminists theologians, such as Rosemary Ruether and Sallie McFague, Mary Daly, and Ivone Gebara led the way.

The Emerging Field of Religion and Ecology

An effort to identify and to map religiously diverse attitudes and practices toward nature was the focus of a three-year international conference series on world religions and ecology. Organized by Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim, ten conferences were held at the Harvard Center for the Study of World Religions from 1996-1998 that resulted in a ten volume book series (1997-2004). Over 800 scholars of religion and environmentalists participated. The director of the Center, Larry Sullivan, gave space and staff for the conferences. He chose to limit their scope to the world religions and indigenous religions rather than “nature religions”, such as wicca or paganism, which the organizers had hoped to include.

Culminating conferences were held in fall 1998 at Harvard and in New York at the United Nations and the American Museum of Natural History where 1000 people attended and Bill Moyers presided. At the UN conference Tucker and Grim founded the Forum on Religion and Ecology, which is now located at Yale. They organized a dozen more conferences and created an electronic newsletter that is now sent to over 12,000 people around the world. In addition, they developed a major website for research, education, and outreach in this area (fore.yale.edu). The conferences, books, website, and newsletter have assisted in the emergence of a new field of study in religion and ecology. Many people have helped in this process including Whitney Bauman and Sam Mickey who are now moving the field toward discussing the need for planetary ethics. A Canadian Forum on Religion and Ecology was established in 2002, a European Forum for the Study of Religion and the Environment was formed in 2005, and a Forum on Religion and Ecology @ Monash in Australia in 2011.

Courses on this topic are now offered in numerous colleges and universities across North America and in other parts of the world. A Green Seminary Initiative has arisen to help educate seminarians. Within the American Academy of Religion there is a vibrant group focused on scholarship and teaching in this area. A peer-reviewed journal, Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture, and Ecology , is celebrating its 25 th year of publication. Another journal has been publishing since 2007, the Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature, and Culture . A two volume Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature edited by Bron Taylor has helped shape the discussions, as has the International Society for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture he founded. Clearly this broad field of study will continue to expand as the environmental crisis grows in complexity and requires increasingly creative interdisciplinary responses.

The work in religion and ecology rests in an intersection between the academic field within education and the dynamic force within society. This is why we see our work not so much as activist, but rather as “engaged scholarship” for the flourishing of our shared planetary life. This is part of a broader integration taking place to link concerns for both people and the planet. This has been fostered in part by the twenty-volume Ecology and Justice Series from Orbis Books and with the work of John Cobb, Larry Rasmussen, Dieter Hessel, Heather Eaton, Cynthia Moe-Loebeda, and others. The Papal Encyclical is now highlighting this linkage of eco-justice as indispensable for an integral ecology.

The Dynamic Force of Religious Environmentalism

All of these religious traditions, then, are groping to find the languages, symbols, rituals, and ethics for sustaining both ecosystems and humans. Clearly there are obstacles to religions moving into their ecological, eco-justice, and planetary phases. The religions are themselves challenged by their own bilingual languages, namely, their languages of transcendence, enlightenment, and salvation; and their languages of immanence, sacredness of Earth, and respect for nature. Yet, as the field of religion and ecology has developed within academia, so has the force of religious environmentalism emerged around the planet. Roger Gottlieb documents this in his book A Greener Faith . (Gottlieb 2006) The Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew held international symposia on “Religion, Science and the Environment” focused on water issues (1995-2009) that we attended. He has made influential statements on this issue for 20 years. The Parliament of World Religions has included panels on this topic since 1998 and most expansively in 2015. Since 1995 the UK based Alliance of Religion and Conservation (ARC), led by Martin Palmer, has been doing significant work with religious communities around under the patronage of Prince Philip.

These efforts are recovering a sense of place, which is especially clear in the environmental resilience and regeneration practices of indigenous peoples. It is also evident in valuing the sacred pilgrimage places in the Abrahamic traditions (Jerusalem, Rome, and Mecca) both historically and now ecologically. So also East Asia and South Asia attention to sacred mountains, caves, and other pilgrimage sites stands in marked contrast to massive pollution.

In many settings around the world religious practitioners are drawing together religious ways of respecting place, land, and life with understanding of environmental science and the needs of local communities. There have been official letters by Catholic Bishops in the Philippines and in Alberta, Canada alarmed by the oppressive social conditions and ecological disasters caused by extractive industries. Catholic nuns and laity in North America, Australia, England, and Ireland sponsor educational programs and conservation plans drawing on the eco-spiritual vision of Thomas Berry and Brian Swimme. Also inspired by Berry and Swimme, Paul Winter’s Solstice celebrations and Earth Mass at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York Winter have been taking place for three decades.

Even in the industrial growth that grips China, there are calls from many in politics, academia, and NGOs to draw on Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist perspectives for environmental change. In 2008 we met with Pan Yue, the Deputy Minister of the Environment, who has studied these traditions and sees them as critical to Chinese environmental ethics. In India, Hinduism is faced with the challenge of clean up of sacred rivers, such as the Ganges and the Yamuna. To this end in 2010 with Hindu scholars, David Haberman and Christopher Chapple, we organized a conference of scientists and religious leaders in Delhi and Vrindavan to address the pollution of the Yamuna.

Many religious groups are focused on climate change and energy issues. For example, InterFaith Power and Light and GreenFaith are encouraging religious communities to reduce their carbon footprint. Earth Ministry in Seattle is leading protests against oil pipelines and terminals. The Evangelical Environmental Network and other denominations are emphasizing climate change as a moral issue that is disproportionately affecting the poor. In Canada and the US the Indigenous Environmental Network is speaking out regarding damage caused by resource extraction, pipelines, and dumping on First Peoples’ Reserves and beyond. All of the religions now have statements on climate change as a moral issue and they were strongly represented in the People’s Climate March in September 2015. Daedalus, the journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, published the first collection of articles on religion and climate change from two conferences we organized there. (Tucker & Grim, 2001)

Striking examples of religion and ecology have occurred in the Islamic world. In June 2001 and May 2005 the Islamic Republic of Iran led by President Khatami and the United Nations Environment Programme sponsored conferences in Tehran that we attended. They were focused on Islamic principles and practices for environmental protection. The Iranian Constitution identifies Islamic values for ecology and threatens legal sanctions. One of the earliest spokespersons for religion and ecology is the Iranian scholar, Seyyed Hossein Nasr. Fazlun Khalid in the UK founded the Islamic Foundation for Ecology and Environmental Science. In Indonesia in 2014 a fatwa was issued declaring that killing an endangered species is prohibited.

These examples illustrate ways in which an emerging alliance of religion and ecology is occurring around the planet. These traditional values within the religions now cause them to awaken to environmental crises in ways that are strikingly different from science or policy. But they may find interdisciplinary ground for dialogue in concerns for eco-justice, sustainability, and cultural motivations for transformation. The difficulty, of course, is that the religions are often preoccupied with narrow sectarian interests. However, many people, including the Pope, are calling on the religions to go beyond these interests and become a moral leaven for change.

Renewal Through Laudato Si’

Pope Francis is highlighting an integral ecology that brings together concern for humans and the Earth. He makes it clear that the environment can no longer be seen as only an issue for scientific experts, or environmental groups, or government agencies alone. Rather, he invites all people, programs and institutions to realize these are complicated environmental and social problems that require integrated solutions beyond a “technocratic paradigm” that values an easy fix. Within this integrated framework, he urges bold new solutions.

In this context Francis suggests that ecology, economics, and equity are intertwined. Healthy ecosystems depend on a just economy that results in equity. Endangering ecosystems with an exploitative economic system is causing immense human suffering and inequity. In particular, the poor and most vulnerable are threatened by climate change, although they are not the major cause of the climate problem. He acknowledges the need for believers and non-believers alike to help renew the vitality of Earth’s ecosystems and expand systemic efforts for equity.

In short, he is calling for “ecological conversion” from within all the world religions. He is making visible an emerging worldwide phenomenon of the force of religious environmentalism on the ground, as well as the field of religion and ecology in academia developing new ecotheologies and ecojustice ethics. This diverse movement is evoking a change of mind and heart, consciousness and conscience. Its expression will be seen more fully in the years to come.

The challenge of the contemporary call for ecological renewal cannot be ignored by the religions. Nor can it be answered simply from out of doctrine, dogma, scripture, devotion, ritual, belief, or prayer. It cannot be addressed by any of these well-trod paths of religious expression alone. Yet, like so much of our human cultures and institutions the religions are necessary for our way forward yet not sufficient in themselves for the transformation needed. The roles of the religions cannot be exported from outside their horizons. Thus, the individual religions must explain and transform themselves if they are willing to enter into this period of environmental engagement that is upon us. If the religions can participate in this creativity they may again empower humans to embrace values that sustain life and contribute to a vibrant Earth community.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berry, Thomas. 2009. The Sacred Universe: Earth Spirituality and Religion in the 21st Century (New York: Columbia University Press).

Boff, Leonardo. 1997. Cry of the Earth, Cry of the Poor (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books).

Gottlieb, Roger. 2006. A Greener Faith: Religious Environmentalism and Our Planetary Future . (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Grim, John and Mary Evelyn Tucker, eds. 2014. Ecology and Religion. (Washington, DC: Island Press).

Leopold, Aldo. 1966. A Sand County Almanac . (Oxford University Press).

Rockstrom, Johan and Mattias Klum. 2015. Big World, Small Planet: Abundance Within Planetary Boundaries . (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Schmitz, Oswald. 2016. The New Ecology: Science for a Sustainable World. (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

Taylor, Bron, ed. 2008. Encyclopedia of Religion, Nature, and Culture. (London: Bloomsbury).

Tucker, Mary Evelyn. 2004. Worldly Wonder: Religions Enter their Ecological Phase . (Chicago: Open Court).

Tucker, Mary Evelyn and John Grim, eds. 2001 Religion and Ecology: Can the Climate Change? Daedalus Vol. 130, No.4.

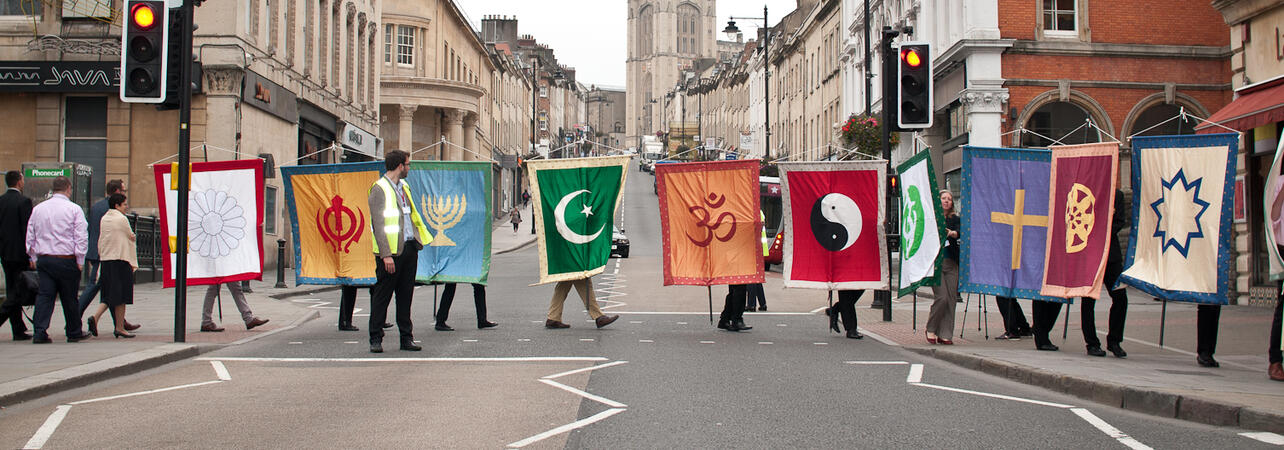

Header photo: ARC procession to UN Faith in Future Meeting, Bristol, UK

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Big History Project

Course: big history project > unit 7.

- WATCH: Where and Why Did the First Cities and States Appear?

- READ: Intro to Agrarian Civilizations

- ACTIVITY: Comparing Civilizations

- READ: Mesoamerica

- READ: Jericho

- READ: East Asia

- READ: Greco-Roman

- READ: Aksum

- READ: Ghana

- READ: We're not in Kansas Anymore — The Emergence of Early Cities

READ: The Origin of World Religions

- ACTIVITY: Comparing Crops

- READ: Gallery — Civilization

- Quiz: The First Cities and States Appear

The Origin of World Religions

Why religions became global.

In subsequent centuries, urban dwellers, and particularly poor, marginal persons, found that authoritative religious guidance, shared faith, and mutual support among congregations of believers could substitute for the tight-knit custom of village existence (within which the rural majority continued to live) and give meaning and value to ordinary lives, despite daily contact with uncaring strangers. Such religious congregations, in turn, helped to stabilize urban society by making its inherent inequality and insecurity more tolerable. (61)

A closer look at Hinduism and Buddhism

The untouchables, the lowest members of society, dealt with human waste and the dead. This group did the jobs no one else wanted to do. They were regarded by the other groups as ritually impure and therefore outside the hierarchy of groups altogether. The Sudras had service jobs, and the Vaisya were herders, farmers, artisans, and merchants. The Ksatriyas, the second highest caste, were the warriors and rulers. At the top were the Brahmans, who were priests, scholars, and teachers. Because priests were part of this caste, the early religion is known as Brahmanism. Brahmanism evolved into the larger Hindu tradition.

The Hindus revered many gods. They believed that people had many lives (reincarnation). Also, they believed in karma. This meant that whatever a person did in this life would determine what he or she would be in the next life. Thus, reincarnation creates a cycle of birth, life, death, and rebirth. The cycle ends only when a person realizes that his or her soul and God’s soul are one. To help achieve this goal, the Hindus had several spiritual practices, some of which are done in the western world today, including meditation and yoga.

1. dharma: living a virtuous life

2. kama: pleasure of the senses

3. artha: achieving wealth and success lawfully

4. moksha: release from reincarnation

Life is filled with suffering (dukkha).

The root of this suffering comes from a person’s material desires (to want what you do not have).

In order to stop suffering, you must get rid of desire or greed.

If you follow the Eight-Fold Path then you can eliminate your material desires, and therefore, your suffering.

Right View: Understand that there is suffering in the world and that the Four Noble Truths can break this pattern of suffering.

Right Intention: Avoid harmful thoughts, care for others, and think about more than yourself.

Right Speech: Speak kindly and avoid lying or gossip.

Right Action: Be faithful and do the right thing; do not kill, steal, or lie.

Right Living: Make sure that your livelihood does not harm others. Do not promote slavery or the selling of weapons or poisons.

Right Effort: Work hard and avoid negative situations.

Right Awareness: Exercise control over your mind and increase your wisdom.

Right Concentration: Increase your peacefulness and calmness, in particular through meditation.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Friday essay: what do the 5 great religions say about the existence of the soul?

Emeritus Professor in the History of Religious Thought, The University of Queensland

Disclosure statement

Philip C. Almond does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Queensland provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners