‘Freedom’ Means Something Different to Liberals and Conservatives. Here’s How the Definition Split—And Why That Still Matters

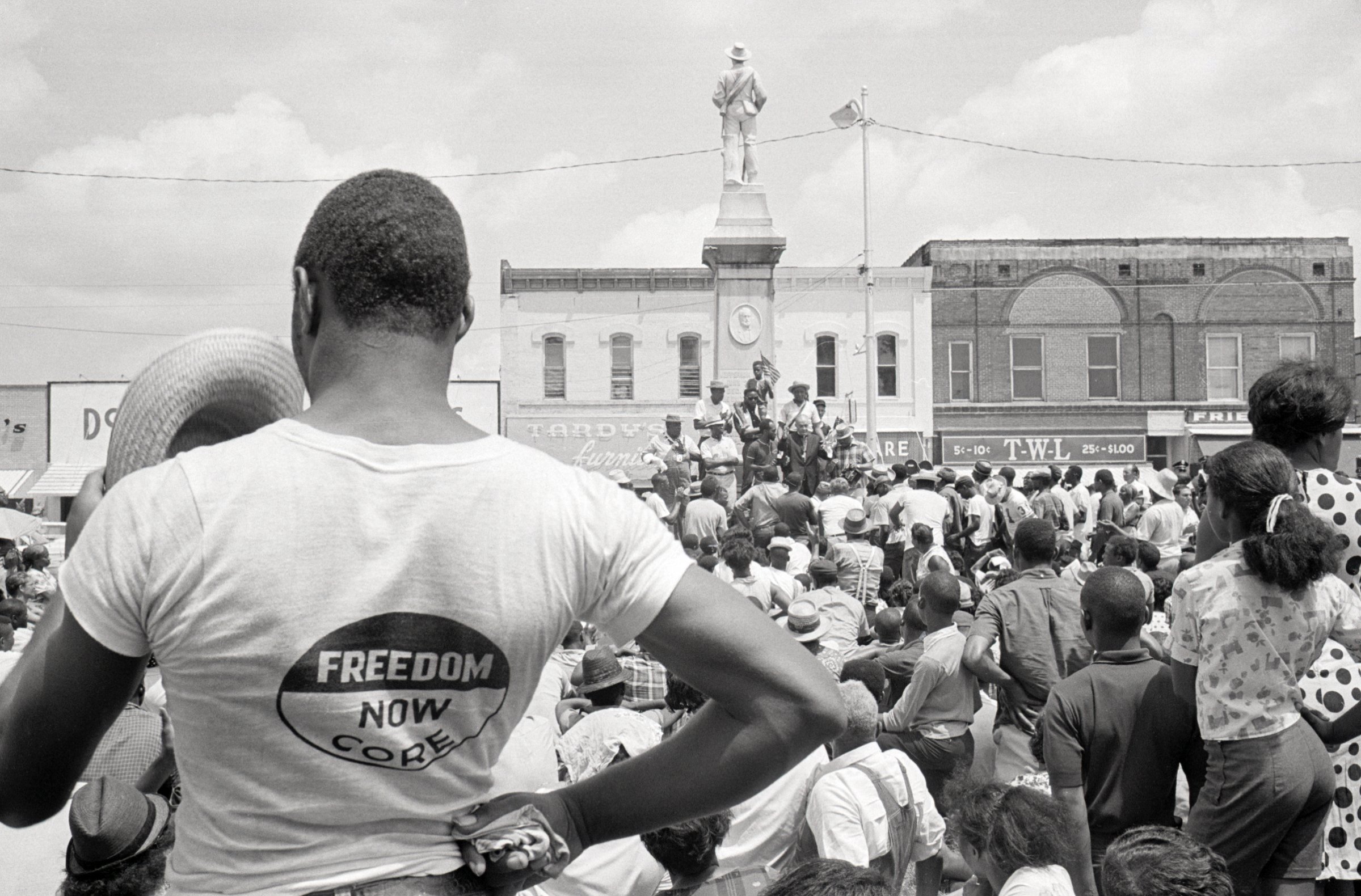

W e tend to think of freedom as an emancipatory ideal—and with good reason. Throughout history, the desire to be free inspired countless marginalized groups to challenge the rule of political and economic elites. Liberty was the watchword of the Atlantic revolutionaries who, at the end of the 18th century, toppled autocratic kings, arrogant elites and ( in Haiti ) slaveholders, thus putting an end to the Old Regime. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Black civil rights activists and feminists fought for the expansion of democracy in the name of freedom, while populists and progressives struggled to put an end to the economic domination of workers.

While these groups had different objectives and ambitions, sometimes putting them at odds with one another, they all agreed that their main goal—freedom—required enhancing the people’s voice in government. When the late Rep. John Lewis called on Americans to “let freedom ring” , he was drawing on this tradition.

But there is another side to the story of freedom as well. Over the past 250 years, the cry for liberty has also been used by conservatives to defend elite interests. In their view, true freedom is not about collective control over government; it consists in the private enjoyment of one’s life and goods. From this perspective, preserving freedom has little to do with making government accountable to the people. Democratically elected majorities, conservatives point out, pose just as much, or even more of a threat to personal security and individual right—especially the right to property—as rapacious kings or greedy elites. This means that freedom can best be preserved by institutions that curb the power of those majorities, or simply by shrinking the sphere of government as much as possible.

This particular way of thinking about freedom was pioneered in the late 18th century by the defenders of the Old Regime. From the 1770s onward, as revolutionaries on both sides of the Atlantic rebelled in the name of liberty, a flood of pamphlets, treatises and newspaper articles appeared with titles such as Some Observations On Liberty , Civil Liberty Asserted or On the Liberty of the Citizen . Their authors vehemently denied that the Atlantic Revolutions would bring greater freedom. As, for instance, the Scottish philosopher Adam Ferguson—a staunch opponent of the American Revolution—explained, liberty consisted in the “security of our rights.” And from that perspective, the American colonists already were free, even though they lacked control over the way in which they were governed. As British subjects, they enjoyed “more security than was ever before enjoyed by any people.” This meant that the colonists’ liberty was best preserved by maintaining the status quo; their attempts to govern themselves could only end in anarchy and mob rule.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

In the course of the 19th century this view became widespread among European elites, who continued to vehemently oppose the advent of democracy. Benjamin Constant, one of Europe’s most celebrated political thinkers, rejected the example of the French revolutionaries, arguing that they had confused liberty with “participation in collective power.” Instead, freedom-lovers should look to the British constitution, where hierarchies were firmly entrenched. Here, Constant claimed, freedom, understood as “peaceful enjoyment and private independence,” was perfectly secure—even though less than five percent of British adults could vote. The Hungarian politician Józseph Eötvös, among many others, agreed. Writing in the wake of the brutally suppressed revolutions that rose against several European monarchies in 1848, he complained that the insurgents, battling for manhood suffrage, had confused liberty with “the principle of the people’s supremacy.” But such confusion could only lead to democratic despotism. True liberty—defined by Eötvös as respect for “well-earned rights”—could best be achieved by limiting state power as much as possible, not by democratization.

In the U.S., conservatives were likewise eager to claim that they, and they alone, were the true defenders of freedom. In the 1790s, some of the more extreme Federalists tried to counter the democratic gains of the preceding decade in the name of liberty. In the view of the staunch Federalist Noah Webster, for instance, it was a mistake to think that “to obtain liberty, and establish a free government, nothing was necessary but to get rid of kings, nobles, and priests.” To preserve true freedom—which Webster defined as the peaceful enjoyment of one’s life and property—popular power instead needed to be curbed, preferably by reserving the Senate for the wealthy. Yet such views were slower to gain traction in the United States than in Europe. To Webster’s dismay, overall, his contemporaries believed that freedom could best be preserved by extending democracy rather than by restricting popular control over government.

But by the end of the 19th century, conservative attempts to reclaim the concept of freedom did catch on. The abolition of slavery, rapid industrialization and mass migration from Europe expanded the agricultural and industrial working classes exponentially, as well as giving them greater political agency. This fueled increasing anxiety about popular government among American elites, who now began to claim that “mass democracy” posed a major threat to liberty, notably the right to property. Francis Parkman, scion of a powerful Boston family, was just one of a growing number of statesmen who raised doubts about the wisdom of universal suffrage, as “the masses of the nation … want equality more than they want liberty.”

William Graham Sumner, an influential Yale professor, likewise spoke for many when he warned of the advent of a new, democratic kind of despotism—a danger that could best be avoided by restricting the sphere of government as much as possible. “ Laissez faire ,” or, in blunt English, “mind your own business,” Sumner concluded, was “the doctrine of liberty.”

Being alert to this history can help us to understand why, today, people can use the same word—“freedom”—to mean two very different things. When conservative politicians like Rand Paul and advocacy groups FreedomWorks or the Federalist Society talk about their love of liberty, they usually mean something very different from civil rights activists like John Lewis—and from the revolutionaries, abolitionists and feminists in whose footsteps Lewis walked. Instead, they are channeling 19th century conservatives like Francis Parkman and William Graham Sumner, who believed that freedom is about protecting property rights—if need be, by obstructing democracy. Hundreds of years later, those two competing views of freedom remain largely unreconcilable.

Annelien de Dijn is the author of Freedom: An Unruly History , available now from Harvard University Press.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Passengers Are Flying up to 30 Hours to See Four Minutes of the Eclipse

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Essay: The Complicated Dread of Early Spring

- Why Walking Isn’t Enough When It Comes to Exercise

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

A nation must think before it acts.

- America and the West

- Middle East

- National Security

- Central Asia

- China & Taiwan

- Expert Commentary

- Directory of Scholars

- Press Contact

- Upcoming Events

- People, Politics, and Prose

- Briefings, Booktalks, and Conversations

- The Benjamin Franklin Award

- Event and Lecture Archive

- Intern Corner

- Simulations

- Our Mission

- Board of Trustees

- Board of Advisors

- Research Programs

- Audited Financials

- PA Certificate of Charitable Registration

- Become a Partner

- Corporate Partnership Program

Freedom: The History of an Idea

- J. Rufus Fears

- June 6, 2007

We live in a moment that is as critical for freedom as the American Revolution, the American Civil War, or the days following Pearl Harbor. In each of those moments, America moved the cause of freedom forward. In the Revolution, we declared our independence from the greatest empire of the day, fought for and won that independence, and then went on to establish a constitution that still gives us liberty under law more than two hundred years later. In the Civil War, we removed the great moral wrong of slavery. After Pearl Harbor, we shouldered the burden of World War II and the subsequent Cold War.

Sept. 11 represents a time just as critical in the history of the freedom. As we judge the generations of the American Revolution, the Civil War, or Pearl Harbor by their heroic response, so we shall be judged. We are engaged in what I believe is a noble crusade to bring freedom to the world. But that crusade is faltering now, in part because we have failed to ask some very fundamental questions.

This essay is intended to ask the most fundamental of those questions: Is freedom a universal human value, which all people in all times and places desire?

History of Freedom

Our foreign policy since the time of Woodrow Wilson has been based in the belief that freedom is a universal value, one that is wanted by all people in all times. But why, if freedom is a universal value, has the history of the world been one of tyranny, misery, and oppression?

Socrates taught that our first task in any discussion is to define our terms. Thus, the starting point here is identifying what we mean by freedom. We never disagree, Socrates tells us, about empirical questions; it is about values that we disagree. No value is more charged with meaning than that of freedom.

If we carefully examine the ideal and reality of freedom throughout the ages, we come to the conclusion that what we call “freedom” is, in fact, an ideal that consists of three component ideals: (1) national freedom; (2) political freedom; and (3) individual freedom.

National freedom is freedom from foreign control. This is the most basic concept of freedom. It is the desire of a nation, ethnic group, or a tribe to rule itself. It is national self-determination.

Political freedom is the freedom to vote, hold office, and pass laws. It is the ideal of “consent of the governed.”

Individual freedom is a complex of values. In its most basic form individual freedom is the freedom to live as you choose as long as you harm no one else, Each nation, each epoch in history, perhaps each individual, may define this ideal of individual freedom in different terms. In its noblest of expressions, individual freedom is enshrined in our Bill of Rights. It is freedom of conscience, freedom of speech, economic freedom, and freedom to choose your life style.

In the United States, we tend to assume that these three ideals of freedom always go together. That is wrong. History proves that these three component ideals of freedom in no way must be mutually inclusive.

You can have national freedom without political or individual freedom; Iraq under Saddam Hussein and North Korea are examples. In fact, this national freedom, this desire for independence, is the most basic of all human freedoms. It has frequently been the justification for some of the most terrible tyrannies in history: Nazi Germany had national freedom but denied individual and political freedom in the name of this national freedom.

It is quite possible to have political and national freedom but not individual freedom. Ancient Sparta had national and political freedom, but none of the individual freedoms we expect today.

The Roman Empire represents two centuries that brought peace and prosperity to the world by extinguishing national and political freedom, but in which individual freedom flourished as it never had.

From the Declaration of Independence to the First World War, the history of our own country provides a dramatic example of the separation of these three component ideals of freedom. After 1776, the United States had national freedom. Adult white males also had political and individual freedom. White women had a considerable degree of individual freedom but no political liberty until 1920 and the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. Until after the Civil War, African-Americans possessed neither political nor individual freedom. In 1857 the Supreme Court formally ruled that African-Americans did not have the right to individual or political freedom. The soldiers of the Confederacy fought valiantly for their political, individual, and national freedom while defending their right to deny individual and political liberty to a considerable proportion of their population.

Thus, clearly, throughout history, these three components ideals of freedom have not been mutually inclusive.

Had we learned this lesson of history, Americans might have avoided crucial mistakes in our recent foreign policy in the Middle East.

History demonstrates that one of the most basic human feelings is the desire for national freedom. You may hate your government, but if someone invades you, you may very well fight in defense of your country. Napoleon learned this in Spain. History should have taught us to be skeptical of the claim that we would be welcomed as liberators in Iraq.

A second lesson of history we should have pondered is that freedom is not a universal value. Great civilizations have risen and fallen without any clear concept of freedom. Egypt—the civilization that built the pyramids, that created astronomy and medicine, did not even have a word for freedom. Everything was under the power of the pharaoh, who was god on earth. Ancient Mesopotamia had a word for freedom, but that word had the connotation of liberties. It was something that the all-powerful king gave to you, like exemption from taxes, and that he could also capriciously take away from you.

In fact, it can be argued that the Middle East, from the time of the pyramids down until today, has had no real concept of freedom.

Russia from the time of Rurik, the first Viking chieftain of Russia in the ninth century, down to Vladimir Putin, has never developed clear ideas of political and individual freedom. Thus we should not have been surprised when the Russian Revolution led not to freedom but to Stalin and one of the bloodiest despotisms in history.

China has no tradition of political or individual freedom. The noble teachings of Confucius are all about order, not freedom.

In fact, the very beginning of civilizations in the Middle East around 3000 BCE and in China around 1700 BCE represented the choice of security over freedom. Civilization began with the decision to give up any freedom in order to have the security of a well regulated economy under a king. Time and again throughout history people have chosen the perceived benefits of security over the awesome responsibilities of freedom.

History thus teaches that freedom is not a universal value. Our Founders knew and acted upon the lessons of history. The Founders, unlike us, thought historically. They used the lessons of the past to make decisions in the present and to plan for the future. They understood that tyranny and the lust for power, not freedom, is the great motivating force of human action and of history. But the Founders also believed that the United States could chart a unique course in history

Our country does have a unique legacy of freedom. That is both a cause for hope and a caution as to whether our unique ideals of freedom can be transplanted to the rest of the world. For in the U.S. we have achieved a unique balance of national, political, and individual freedom.

We have never been conquered; we simply cannot imagine what it would be to be under the rule of a foreigner. Our experience is very different from that of France, for example, or Germany.

We take political freedom for granted. We have regular elections no matter what the circumstances. In 1864, in the midst of the greatest war in our history, we held elections. The Europeans wondered after 9/11 what would happen to America; we went ahead with another election. In a way it is a good thing we are so secure in this freedom that we take it for granted. With that comes our deep love of the Constitution. Of course, Americans may not know what is in the Constitution, but they know it is good and resent any effort to tamper with it.

As to individual freedom, where could one have so much of it, including the basic freedom to create a better life for yourself and your children? People clamor to get into America, because individual freedom opens up a whole new world.

So how did we come to this unique legacy of freedom? Again, history is our guide. Our American legacy of freedom is the product of a unique confluence of five historical currents.

First, there is the legacy of the Old Testament, the idea that we are a nation chosen by God to bear the ark of the liberties to the world. Our Founders believed that deeply. Abraham Lincoln believed it deeply. Franklin Roosevelt believed it.

The second current comes from classical Greece and Rome. The legacy of Greece and Rome is the very basic one of self-government, consent of the governed. The kings of Babylon were chosen by God, Saul was chosen by God. The pharaoh was God on earth. But in Greece and Rome, men said “We are free to govern ourselves under laws that we give ourselves.”

Thirdly, Christianity took the idea of Natural Law from Greece and Rome and turned it into the belief that all men are created equal and endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. The freedom that for the Greeks and Romans had been limited to the citizens of Athens or Rome now became a universal proclamation under Christianity.

Fourthly, England gave us the notion that government is under the law, no matter how powerful that government is. In the Watergate hearings, Sen. Herman Talmadge (D-Ga.) quoted the old saying that “the wind and rain might enter the cottage of a poor Englishman, but the king in all his majesty may not.” The law governs the king himself, and our Congress, senators, and president. As Harry Truman said, any time an American president gets too big for his britches, the people put him back in his place.

Fifthly, there is the contribution of the frontier. From the very beginning, America has been about the frontier. It is what led men and women to Jamestown and Plymouth. The frontier was the vast, seemingly endless land stretching before us. The frontier meant equality of opportunity. Even the best ideals of Greece or Rome or England could never flourish, because they were always cramped. But here there was land and the ability to start over again. This mattered more than all the ancient hatreds and class frictions that had existed under the old world. We cannot understand why Bosnians, Serbs, and Croats speak the same language but kill each other. Their hatreds have been festering for centuries, but here they pass away. That has been the unique gift of the frontier.

The existence of these elements in other nations and civilizations only underscores the uniqueness of the American experience of freedom. Russia has the tradition of Greece and Rome, Christianity, the tradition of the Old Testament; and it has a frontier. But it lacks that English sense of government under the law. So the frontier in Russia becomes the home of the gulag. Latin America has the tradition of Christianity and the Old Testament, and of Greece and Rome, and of the frontier. But Spain lacked the powerful English concept that government is under the law. Thus Latin America, despite its industrious and intelligent population and its natural resources, has never developed a stable basis for political and individual freedom.

Our heritage of freedom has been forged in war and hardship as well as in prosperity. Our national independence was proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence. Name another nation in history founded on principles. An Italian or German will say you are an Italian or German because you speak Italian or German. Traditionally, you were born an Englishman; you were geographical accident. But in America we have said from the start that everyone can come here from wherever they wish. They can speak whatever language is their mother tongue and practice whatever religion they want. They become an American by adopting our principles.

The principles proclaimed in 1776 are the noblest of all principles: we hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal and endowed by their Creator with the unalienable right of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

The proclamation of these ideals in the Declaration of Independence is based on the belief in absolute right and absolute wrong. You can deny that today. We seem to have a society that believes there is no such thing as truth. Ethics is all a matter of circumstances. But the Founders believed in eternal truths, valid in all places and all times. And they believed that governments are instituted among men to achieve those goals. That is the purpose of government. And if a government does not fulfill those goals, you have not only the right but the duty to overthrow it.

The absolute truths of the Declaration of Independence are founded on a belief in God. God appears four times in the Declaration of Independence: “Nature’s God,” the “Creator,” “Supreme Judge of the world,” “Divine Providence.”

Thus our national freedom is founded on absolute truth and upon a belief in God.

As the Declaration of Independence is the charter of our national freedom, so the Constitution is our charter of political freedom.

When that constitution was brought forth in Philadelphia, we were thirteen straggling republics along the eastern seaboard. If Benjamin Franklin or George Washington wanted to go somewhere, they went in the same way Cicero or Caesar did: they walked, rode, or sailed. If they wanted to communicate, they did it the same way Caesar or Cicero did. George Washington received inferior medical care to what a Roman gladiator got in the first century CE. And yet that same constitution gives us liberty under law and prosperity in a world of technology that Benjamin Franklin could not even have imagined and when we are superpower of the world. We should never take this extraordinary achievement for granted.

The American people in their wisdom would not ratify this constitution without the promise of a bill of rights. It seems to us extraordinary today that the first Congress kept its promise; and in short order set down and produced the Bill of Rights, which still guarantees these fundamental freedoms of individual liberty.

But there was still slavery, written into the Constitution. God is not mentioned once in the Constitution, but slavery was made the law of the land. To remove that wrong of slavery we fought the bloodiest war in our history, in which 623,026 Americans died. It produced men of great honor and integrity on both sides. It was finally resolved at Gettysburg.

When Abraham Lincoln went to Gettysburg to redefine our mission, he started with the Declaration of Independence. “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” It was unique because it was dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. In one sentence he told Americans why they were fighting the war, to see whether any nation so conceived and dedicated could long endure. In all the rhetoric we had about Vietnam and all that we have heard about Iraq, we have not been told so simply why we were at war.

Lincoln then went on to state that this civil war was a challenge laid upon this nation by God. The more Lincoln grappled with why this terrible war had come, the more convinced he had become that it was sent by God to punish us for the fundamental wrong of slavery. He told Americans that we must resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain and that this nation under God should have a new birth of freedom. And that government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from the earth.

So this war that had cost so many lives was resolved in a way that no other nation would have. The Confederates simply pledged their word not to take up arms and to go home. The reconciliation began. I think that too is unique in history.

With the Civil War we see the growth of democracy, the move towards extending the franchise to women, 18 year olds. They all become part of this political freedom.

This nation has continued in a unique course of freedom. In World War II we fought and won the war in the name of democratic freedom. We could have withdrawn the way we did after World War I. But we recognized that isolationism had been a mistake. So we shouldered the burden of the Cold War.

Now we have been called again, and the question is, will we find the leadership to tell us why this great challenge is there? Will we find the will to resolve this struggle? Will we find the understanding among ourselves to see the great task that, as Lincoln said, is still before us?

I speak to you not only the legacy of America, but of destiny. I believe that no people in history have ever been more magnanimous, generous, courageous, willing to forgive and forget, and willing to help the world than have the Americans. So after World War II, we raised Germany and Japan up. This remains our greatest foreign policy triumph. We took those two nations that had no long tradition of freedom and made them into viable, prosperous democracies.

Today, because of the United States, more people throughout the world live in freedom than any time in history. If we are willing to accept the challenge, it may yet be our destiny to change the course of history and to establish freedom as a universal value.

Related Event

- Living Without Freedom

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How Lea Ypi Defines Freedom

By Han Zhang

In February, 2020, the Albanian-British philosopher Lea Ypi found herself in a closet trying to write a book about freedom. Ypi, who is a professor of political theory at the London School of Economics, had just started a yearlong research fellowship in Berlin when the world went into lockdown. Libraries closed. Seminars were suspended. Unable to go outside, her three young children colonized the family’s apartment as their playground, and she retreated to her closet to work.

Ypi studies political definitions of freedom, and lockdown gave her ideas new weight. The privations of the early pandemic brought back memories of her childhood in Communist Albania. Ypi found some irony in the fact that, in Western Europe, the heartland of liberal democracy, individual autonomy was being restricted in the name of social good. The sense of impending transformation brought on by the pandemic reminded her of witnessing the fall of Communism in Albania as a child in the early nineteen-nineties. At moments of rupture like these, Ypi told me when we met earlier this year, “ideas of freedom and society are tested.” People began questioning the framework of their world, and the future, however briefly, seemed up for grabs. Ypi had intended to write a straightforward treatise on liberal and socialist concepts of political freedom. The cascade of memories set off by the pandemic changed her mind. She decided, instead, to write a memoir.

The next year, Ypi published “ Free: A Child and a Country at the End of History ,” an account of growing up in Albania during its bruising transition to a multiparty system. “Free” is the intellectual history that Ypi had envisioned, exploring the political traditions of liberalism and socialism, but it tests these ideas against twentieth-century history. The book is given shape by the collapse of the nearly five-decade-long period of Communist rule in Albania and the country’s first multi-party election, which took place in 1991. Like many post-Communist governments, the new Administration adopted a program of economic “shock therapy.” By 1997, when Ypi was in her last year of high school, the country was in a state of emergency. Schools closed; financial institutions went bankrupt; anger at government incompetence skyrocketed; amid the civil unrest, shootings were a daily occurrence. Protests gave way to street fighting, and estimates suggest that at least half a million weapons were looted from military depots.

In the early pages of “Free,” the child Ypi is innocent of the forces shaping her world. The point of view is deceptive: by the end of the book, the promises and disillusioning reality of both socialism and liberalism are laid bare. Since being published, “Free” has been translated into twenty-nine languages and become a best-seller in many countries, including the U.K., Germany, Iceland, Norway, and Spain. When I met with Ypi in a hotel lobby, in Orange County, where she was delivering a talk, she had just landed after days of events on the East Coast. (“The book simply exploded,” her Californian host told me.) Her blond hair was casually pinned, and she wore a green cotton top and black culottes with unfussy elegance. “I didn’t think that people were going to be immediately interested in Albania,” Ypi told me over a Niçoise salad. She ate with gusto and without pausing her animated speech. Perhaps, she speculated, the response to her book reflected deep anxieties about the state of the world. “You have these collective failures and attempts at collective renewals,” she said. She cited the pandemic, the climate crisis, and widespread political dysfunction. “We’re at the point where our institutions are not really sustainable. Something needs to be done, but we can’t quite find the strength to build alternatives.”

In Vivian Gornick’s 1977 book, “ The Romance of American Communism ,” Gornick complains of the “oppressive distance” that crept into the voices of many writers, including those who used to be Communists themselves, when they turned to the subject of Communism. Under the guise of objectivity, such writers, Gornick writes, operated with the patronizing assumption that the Communists “were infantile while we are mature; as though we would have known better while they were incapable of knowing better.” Ypi is the rare post-Communist writer who works through the wounded past of the project of socialism without reflexively dismissing her younger self’s sincere beliefs. Instead, she demands that her readers take the collective attempt of twentieth-century socialism seriously and see its failures and hopes as a mirror of our own. “People tend to think of liberalism and socialism as complete opposites. In fact, historically and philosophically, they are both attempts to think about freedom,” Ypi told me.

As a child, Ypi, an ardent Young Pioneer, was taught that she lived in the freest place on earth. Albanian Communist Party doctrine held that their country’s citizens were not only free of capitalist exploitation but practiced a purer form of socialism than their comrades in the Soviet Union and China, whose regimes the Albanian government dismissed as revisionist. Her day-to-day reality told a different story. In “Free,” she writes of how the adults around her spoke in coded language and exchanged meaningful glances; her childish utterances about forbidden subjects were sometimes met by her family’s censorious panic. Even everyday tasks required unusual stamina: lines to buy groceries were so long that-shopping for food could take a whole day. Material deprivation had a psychological impact. Ypi’s mother prized an empty Coca-Cola can so much that after it disappeared she accused a close friend of stealing it.

After the transition to liberalism, Albanians were better off in some significant ways. They had extricated themselves from the restrictions of Communism. They no longer needed to perform fealty to Stalin and Enver Hoxha, who was the former Albanian Prime Minister, and started to talk about their religions again. But, in other ways, Albanians remained unfree. Without robust financial or political institutions, the country was at the mercy of the acutely under-regulated market economy put in place by its new government. Many people lost the bulk of their savings in pyramid schemes. Material poverty persisted. Well-paying jobs were hard to come by. A political candidate had to borrow Ypi’s father’s socks to finish off the respectable look he was going for.

Ypi’s parents had different views of freedom. Her mother, Doli, who was a secondary-school teacher, believed in an individualistic, libertarian kind of freedom. She watched the soap opera “Dynasty” to admire the interior decoration and attempted to style her hair in the fashion of Margaret Thatcher’s. She also styled her politics the Thatcherite way: to her, Ypi writes, “the world was a place where the natural struggle for survival could be resolved only by regulating private property.”

Ypi’s father, Zafo, had a more socially oriented vision of freedom. He was an engineer in forestry management and followed politics with great interest, often borrowing world events to narrate their lives. Ypi was born, in 1979, prematurely and had to stay in an incubator for months. At one point, her chance of survival was fifty per cent. Zafo joked, in reference to the hostage crisis in Iran, “About the same as the American diplomats in Tehran.” Zafo’s grandfather had briefly served as Prime Minister in the early nineteen-twenties, and Zafo’s father, a lawyer active in social-democratic circles, had been imprisoned by the Communist government for fifteen years. As a result of his family background, Zafo had been banned by the Party from studying math in university, but the experience didn’t poison his commitment to egalitarianism. He embraced international freedom struggles, enthusing over the news of the end of apartheid in South Africa, and was contemptuous of consumerism. When he saw a person begging for money, he would empty his pockets, telling his daughter that deprivation wasn’t a personal failing.

Soon after the country’s first multi-party election, in 1991, Zafo was laid off from his forestry job—the new Administration wasn’t prioritizing planting trees, and his office was set to be closed. After a long period of unemployment, he found work at the country’s largest port, which was soon to be partially privatized. As the general director, he struggled with the actions he was asked to take to keep the enterprise profitable. Firing workers and depriving them of their livelihoods shattered him more than being unemployed himself had. “Socialism had denied him the possibility to be who he wanted,” Ypi writes. “Capitalism was denying it to others.”

Doli weathered the transition to post-Communism more successfully than her husband had—she joined the Democratic Party of Albania and served as a leader of a national women’s association. She kept busy organizing reform campaigns and seeking restitution of her family’s properties—which had been confiscated by the Communists—in court. Unlike Zafo, Doli didn’t believe in people’s fundamental goodness. “That’s why she was convinced that socialism could never work, even under the best circumstances. It was against human nature,” Ypi writes. Reluctant to trust other people or the state, she preferred to take matters into her own hands and keep other people’s power to interfere in her life to a minimum. When a visiting French feminist activist asked Doli how she dealt with sexual harassment, she replied that she always carried a knife. As a young woman, she had to rely on hitchhiking to commute to teach at a remote village school. Once, a truck driver placed a hand on her thigh. She issued a warning: a tickle by the tip of the knife. Under Communism, Doli had the gumption to raise a flock of chicks in their bathroom in order to secure a reliable supply of eggs for her family. During the unrest of 1997, when Albania’s Democratic Party started to hand out guns for self-defense, she tried to convince her husband that they could use one. Zafo didn’t want a firearm at home, but she insisted that owning a gun could be a deterrent.

In “Free,” Ypi inclines more toward her father’s expansive, socially oriented view of freedom than her mother’s more narrowly individualistic one. But the true anchor of the book is her paternal grandmother, Nini, who helped to raise Ypi and who would scold her in French when she misbehaved. Nini grew up in extreme privilege—her uncle was a pasha in the Ottoman Empire, and she met her husband at the Albanian monarch King Zog’s wedding—but she lost everything early in life. After the Communists took power, in 1946, many of her family’s politically influential friends were killed, her husband was sent to prison, and she had to work in labor camps. Even when she was suffering from political persecution and people close to her were dying by execution or suicide, Nini remained convinced of her own moral agency. “Regardless of the changes of circumstances and the oppression around her, she thought she’d always been morally free to act in a responsible way,” Ypi said.

As a scholar, she has come to see her grandmother’s focus on moral agency to be akin to the Kantian idea of freedom, a subject Ypi has been researching and teaching for more than a decade. Kantians like Ypi reflect on the distinction between “negative freedom”—a person’s preferences void of social context—and “positive freedom,” which involves making decisions based on reason, setting aside one’s immediate cravings. In America, “the land of the free” and “beacon of democracy,” people often think of freedom as an entitlement, not as something that must be realized and preserved in concert with others. At a talk in Chicago earlier this year, she reminded her audience that democracy is a “demanding ideal.” Our current system, she went on, “is not really democracy: we have constellations and configurations of interests that are very powerful . . . you have a world where strong states shape the fates of weaker states. You have countries where stronger citizens with more money shape the fates of weaker citizens.” When I met her, she told me, “I want to get away from this idea that, because you have an election, democracy is secure. It’s not a finish line.”

Ypi sees “an obvious discrepancy between the ideology of freedom and ideal freedom.” In the absence of the real thing, the word is often invoked as a license to disregard the well-being of others: to refuse to wear masks during a COVID surge; to flaunt civilian ownership of assault weapons at a time when mass shootings outnumber the days of the year; to voice anti-trans rhetoric that fuels real-world violence and suicides. Ypi has a refreshing insistence on the responsibility that freedom entails. “There’s a dimension of freedom that’s not just about satisfaction, but it’s about placing your desires in a moral context and in the context of relationship to other people, and saying, ‘Well, what makes sense for all of us?’ ” Ypi told me. In a 2019 article for the New Statesman , she echoed Plato’s warning, in “ The Republic ,” that the demagogue, the “man of the people” in thrall to his desires and whims, is a perennial threat to democracy. Failure to work toward the freedom of others, she pointed out, leaves the door open to populists like Boris Johnson and Donald Trump .

Ypi’s education in political philosophy began in 1997, when, aided by a scholarship, she arrived at the Sapienza University of Rome. At university, her housing was provided for, and the cafeteria meals were subsidized, but she lived on about a hundred dollars each month. If she wanted to cook, there was no budget to eat meat or fish regularly. Instead, she would buy pouches of powdered tomato soup. She still remembers walking by the chocolate aisle week after week, longing for a Côte d’Or bar. It was not in the budget. There was no one to tell her what to think or what to do, but, without money, life was full of constraints: she couldn’t afford to go to the movies, hang out with friends at bars, or take a German-language course.

Her classmates, fair-minded aspiring philosophers, often came from well-off families. Though they espoused left-wing political ideas of equality, “it was always about the problems of the world, outside of them,” Ypi said; their blindness to their own advantages and to Ypi’s deprivation was striking. “I really resented them. How do you not see that poverty is such a constraint on someone’s life?” she said. Before she left for college, she had promised her father not to study Marxism. But her experience of the forms of unfreedom that persisted in liberal societies eventually pushed her to reëngage with the tradition of socialism. During her pursuit of a Ph.D., she began to explore “the possibility of reconciling Kant and Marx” and their common ground in society’s search for freedom.

After Albania transitioned to liberalism, and people were free to leave, the country experienced an exodus of economic migrants seeking livable wages, but a better future didn’t exist for many of them. Some drowned during the journey at sea to Italy. Others, like Ypi’s childhood friend, whom she called Elona in “Free,” worked near a train station in Milan, trying to make a living through sex work after running away from home at thirteen years old. Back in 1991, in the spring, Albanians were warmly welcomed refugees. By that summer, they were shunned as “illegal immigrants.” “There was so much racism against Albanians in the nineties in Italy,” Ypi said. Once, on the train in Rome, she offered to carry a bag for an elderly woman, who thanked her and said, “There are so many Albanians around stealing bags!”

It has been twenty-six years since Ypi left her home country. Since then, xenophobia has become politically legitimated in many parts of Europe. Far-right nativist parties, such as Marine Le Pen ’s National Rally (formerly National Front) and Giorgia Meloni ’s Fratelli d’Italia, have moved from the fringe to the mainstream. Last year, Suella Braverman, who was then the British Home Secretary, told Parliament, “If Labour were in charge, they would be allowing all the Albanian criminals to come to this country. They would be allowing all the small boats to come to the U.K. They would open our borders and totally undermine the trust of the British people in controlling our sovereignty.” A week after Braverman’s statement, Ypi questioned why the right was so fixated on Albanians, on the conservative-leaning talk show “Good Morning Britain.” “It’s not just a problem about the Albanian community. It’s a problem for Britain. You begin to disintegrate the multicultural project of integration if you start to treat minorities like this,” she said, her amiable debate-team-champion energy metabolizing into controlled anger. During the fourteen years she has lived in the U.K., her brother was never able to get a visa to visit. In 2015, when Ypi gave birth to her second child, immigration authorities also denied her mother. (A few years later, when Doli tried again and repackaged herself as a wealthy homeowner visiting to shop at Harrods, her entry was permitted.)

Since her appearance on “Good Morning Britain,” Ypi has received more than a hundred messages on social media from the Albanian diaspora, sharing immigration woes and feelings of anxiety at work and school. She has become their rare representative with a platform, which she has used to amplify their voices. “The UK’s immigration system does not find criminals—it creates them. It projects criminal intent well before any criminal act has occurred,” she wrote , in the New Statesman , pushing back against Braverman’s rhetoric. Ypi thinks that economic migrants should be seen as akin to refugees or political-asylum seekers. The lack of employment opportunities that drive them to leave their home countries are almost always the result of historical oppression and exploitation. Politicians should frame economic migration as “an implication of global injustice,” she says. If freedom of movement is a right worth defending, she argues, liberal societies can’t condemn countries like North Korea that prevent citizens from leaving while closing their own borders and imprisoning immigrants.

Ypi is a polyglot—she speaks Albanian, French, Italian, English, German, and Spanish—but the two languages that she finds herself travelling back and forth between most often are literature and philosophy. As a girl, she wanted to be a writer and composed poetry about repression, frustration, and freedom. After the fall of Communism, a French TV crew making a documentary about the transition filmed the eleven-year-old Ypi coming home from school. In the film, she walks between drab low-rise buildings on a path covered in rubble. “I’ve been lucky in my misfortunes,” she tells the reporter. Then she reads one of her poems in French. “Man inherits the earth with pleasure and sometimes with misery,” she recites. “It’s not God, but man that will destroy.”

In those years, as the outside world disintegrated, Ypi found refuge in reading. After the transition, the history textbooks that she and her classmates had used under Communism were discarded. It took some time for new ones to be published; for one thing, there were no printers in operation or paper to print on. Ypi’s mother unsealed a trove of books—literature, philosophy, law, and art history—that had been stored out of sight in the family attic. The books, which had belonged to her grandfather, who studied in France in the nineteen-thirties, were musty and yellowing, and many pages showed signs of being nibbled by mice. A French encyclopedia introduced her to Plato, Nietzsche, and Sartre. She binged on Dante, Shakespeare, Balzac, Maupassant, and Proust, and loved to “spend time with the Russians”: Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Tolstoy. “I created a parallel identity through these books and these characters,” Ypi said. Thirty years later, the names of characters in classic novels roll off her tongue as if they were old friends: she identified with Thomas Mann’s Settembrini for his “reason, hope and belief” and loved Turgenev’s Madame Odintsova for being rational even in her emotions.

Academia had slowly killed the literature in her, Ypi told me. “You enter this realm of abstract concepts, but you lose the human side of it because you are generalizing and abstracting all the time,” she said. “It is hard to write simple. What I like about literature is that it’s a very democratic thing. You open up avenues for people to engage with their problems.” Trying to write strong characters forced Ypi to argue with her own ideas. “You create an alternative theory in your mind” in order to inhabit a particular character, she told me. Then that character “challenges you,” and “you become the worst critic of yourself.”

Writing “Free” forced Ypi to see her mother from a new perspective. Doli was never a touchy-feely mother. When she became active in politics, she didn’t have a lot of time for Ypi. “She was really giving a lot to the public sphere,” Ypi said. But, after Ypi had her own children, she has tried to balance her roles as a mother and a professional, and has come to understand her mother’s no-nonsense approach to child rearing.“I started to see more of the constraints in her life as opposed to my entitlements,” Ypi said. Without extensive help raising her children, Doli had to focus on meeting their concrete needs. She still expresses support for her daughter in the form of finishing tasks on Ypi’s to-do list and is skeptical of Ypi’s work in philosophy. She thinks Ypi is a utopian who plays “word games” and who doesn’t understand “the real world.” “My mom is just really skeptical of humans,” Ypi told me. At moments, she wavers and thinks that maybe her mother’s skepticism is right.

Many commentators seem to find it easier to appreciate Ypi’s critique of Albania’s Communist past than to engage with her equally severe critique of present-day capitalism. “I am with her mother on this,” a Financial Times journalist who interviewed Ypi writes , while acknowledging that Ypi’s “contemporary questions are well worth asking.” Still, Ypi doesn’t feel dismissed. She knows her writing pushes back against ideas that people take for granted. “Sometimes they don’t want to be challenged too much. They want to still feel safe somehow,” she said. In the first book of theory that she published, in 2011, a meditation on global justice and political agency, she presents herself as a philosopher in the “activist mode.” She isn’t content simply to observe things as they are. Instead, she wants to drive debates on how to change them. “Nothing was feasible until it was because somebody had the courage to go out there and articulate it and make it happen,” she said.

When I chatted with Ypi on Zoom a few weeks after our first meeting, she asked to postpone the call so that she could finish dinner. She hadn’t eaten all day. In her kitchen, a yellow sign indicates how chaotic her life can get. It says, in Albanian, “Look after your comrade during work.” That day, she had two other interviewers calling from Finland and Spain, one photo shoot, and a work meeting before going to her children’s school concert. Her husband, a political scientist, also travels a lot. “Our house is like a hotel lobby. One is coming with a suitcase, and the other is going,” she said. She keeps the trips short—part of the balancing act of the scholar-author-mother.

I asked Ypi if she felt free, and she returned to her grandmother’s concept of freedom. “It’s something that reveals itself when you act responsibly,” she said. Her hectic routine is punctuated by moments of harmony, as when her children, inspired by her work, have told her that they want to be writers like her. She wants to raise them in the way that her grandmother raised her, teaching them to act responsibly and to be critical of their privileges. Come Christmas, she tells me, she tries to choose presents that will make her kids neither entitled nor deprived. “Being a moral agent is very demanding,” she said. “But then everything is hard. And the cost of not trying is higher.” Her principled hope brought to mind an anecdote she shared when we first met. Americans are so enthusiastic in their greetings, she observed. In Albania, people often answer the question “How are you doing?” with “I keep pushing.” ♦

New Yorker Favorites

Searching for the cause of a catastrophic plane crash .

The man who spent forty-two years at the Beverly Hills Hotel pool .

Gloria Steinem’s life on the feminist frontier .

Where the Amish go on vacation .

How Colonel Sanders built his Kentucky-fried fortune .

What does procrastination tell us about ourselves ?

Fiction by Patricia Highsmith: “The Trouble with Mrs. Blynn, the Trouble with the World”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Benjamin Kunkel

By Adam Gopnik

By James Wood

Tools for thinking: Isaiah Berlin’s two concepts of freedom

Freedoms and restrictions. Stand on the right. Don’t smoke. Photo by Phil Dolby/Flickr

by Maria Kasmirli + BIO

‘Freedom’ is a powerful word. We all respond positively to it, and under its banner revolutions have been started, wars have been fought, and political campaigns are continually being waged. But what exactly do we mean by ‘freedom’? The fact that politicians of all parties claim to believe in freedom suggests that people don’t always have the same thing in mind when they talk about it. Might there be different kinds of freedom and, if so, could the different kinds conflict with each other? Could the promotion of one kind of freedom limit another kind? Could people even be coerced in the name of freedom?

The 20th-century political philosopher Isaiah Berlin (1909-97) thought that the answer to both these questions was ‘Yes’, and in his essay ‘Two Concepts of Liberty’ (1958) he distinguished two kinds of freedom (or liberty; Berlin used the words interchangeably), which he called negative freedom and positive freedom .

Negative freedom is freedom from interference. You are negatively free to the extent that other people do not restrict what you can do. If other people prevent you from doing something, either directly by what they do, or indirectly by supporting social and economic arrangements that disadvantage you, then to that extent they restrict your negative freedom. Berlin stresses that it is only restrictions imposed by other people that count as limitations of one’s freedom. Restrictions due to natural causes do not count. The fact that I cannot levitate is a physical limitation but not a limitation of my freedom.

Virtually everyone agrees that we must accept some restrictions on our negative freedom if we are to avoid chaos. All states require their citizens to follow laws and regulations designed to help them live together and make society function smoothly. We accept these restrictions on our freedom as a trade-off for other benefits, such as peace, security and prosperity. At the same time, most of us would insist that there are some areas of life that should not be regulated, and where individuals should have considerable, if not complete, freedom. A major debate in political philosophy concerns the boundaries of this area of personal negative freedom. For example, should the state place restrictions on what we may say or read, or on what sexual activities we may engage in?

Whereas negative freedom is freedom from control by others, positive freedom is freedom to control oneself. To be positively free is to be one’s own master, acting rationally and choosing responsibly in line with one’s interests. This might seem to be simply the counterpart of negative freedom; I control myself to the extent that no one else controls me. However, a gap can open between positive and negative freedom, since a person might be lacking in self-control even when he is not restrained by others. Think, for example, of a drug addict who cannot kick the habit that is killing him. He is not positively free (that is, acting rationally in his own best interests) even though his negative freedom is not being limited (no one is forcing him to take the drug).

In such cases, Berlin notes, it is natural to talk of something like two selves: a lower self, which is irrational and impulsive, and a higher self, which is rational and far-sighted. And the suggestion is that a person is positively free only if his higher self is dominant. If this is right, then we might be able to make a person more free by coercing him. If we prevent the addict from taking the drug, we might help his higher self to gain control. By limiting his negative freedom, we would increase his positive freedom. It is easy to see how this view could be abused to justify interventions that are misguided or malign.

B erlin argued that the gap between positive and negative freedom, and the risk of abuse, increases further if we identify the higher, or ‘real’, self, with a social group (‘a tribe, a race, a church, a state’). For we might then conclude that individuals are free only when the group suppresses individual desires (which stem from lower, nonsocial selves) and imposes its will upon them. What particularly worried Berlin about this move was that it justifies the coercion of individuals, not merely as a means of securing social benefits, such as security and cooperation, but as a way of freeing the individuals themselves. The coercion is not seen as coercion at all, but as liberation, and protests against it can be dismissed as expressions of the lower self, like the addict’s craving for his fix. Berlin called this a ‘monstrous impersonation’, which allows those in power ‘to ignore the actual wishes of men or societies, to bully, oppress, torture them in the name, and on behalf, of their “real” selves’. (The reader might be reminded of George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), which shows how a Stalinist political party imposes its conception of truth on an individual, ‘freeing’ him to love the Party leader.)

Berlin was thinking of how ideas of freedom had been abused by the totalitarian regimes of Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia, and he was right to highlight the dangers of this kind of thinking. But it does not follow that it is always wrong to promote positive freedom. (Berlin does not claim that it is, and he notes that the notion of negative freedom can be abused in a similar way.) Some people might need help to understand their best interests and achieve their full potential, and we could believe that the state has a responsibility to help them do so. Indeed, this is the main rationale for compulsory education. We require children to attend school (severely limiting their negative freedom) because we believe it is in their own best interests. To leave children free to do whatever they like would, arguably, amount to neglect or abuse. In the case of adults, too, it is arguable that the state has a responsibility to help its citizens live rich and fulfilling lives, through cultural, educational and health programmes. (The need for such help might be especially pressing in freemarket societies, where advertisers continually tempt us to indulge our ‘lower’ appetites.) It might be, too, that some people find meaning and purpose through identification with a wider social or political movement, such as feminism, and that in helping them to do so we are helping to liberate them.

Of course, this raises many further questions. Does our current education system really work in children’s best interests, or does it just mould them into a form that is socially and economically useful? Who decides what counts as a rich and fulfilling life? What means can the state legitimately use to help people live well? Is coercion ever acceptable? These are questions about what kind of society we want to live in, and they have no easy answers. But in giving us the distinction between negative and positive freedom, Berlin has given us a powerful tool for thinking about them.

Childhood and adolescence

For a child, being carefree is intrinsic to a well-lived life

Luara Ferracioli

Meaning and the good life

Sooner or later we all face death. Will a sense of meaning help us?

Warren Ward

Philosophy of mind

Think of mental disorders as the mind’s ‘sticky tendencies’

Kristopher Nielsen

Philosophy cannot resolve the question ‘How should we live?’

David Ellis

Values and beliefs

Why do you believe what you do? Run some diagnostics on it

Miriam Schoenfield

Gender and identity

What we can learn about respect and identity from ‘plurals’

Elizabeth Schechter

4.2 Constitutions and Individual Liberties

Learning outcomes.

- Differentiate between negative rights and positive rights constitutions.

- Define constitutionalism.

- Analyze how different constitutional systems treat the individual.

- Define due process.

- Explain how the rule of law and its principles are important to individual freedom.

As discussed in Chapter 2: Political Behavior Is Human Behavior most countries have a formal constitution —a framework, blueprint, or foundation for the operation of a government. The constitution need not be in writing, in one document, or even labeled a constitution. Britain, New Zealand, and Israel do not have codified constitutions but instead use uncollected writings that establish the form of government and set out the principles of liberty. 14 In many countries, a series of documents, usually called the basic laws , codifies the government structure and individual rights. 15 If a country lacks a single document labeled a constitution, how does one know that certain writings serve as the country’s constitution? A constitution describes the underlying principles of the people and government, the structure of the branches of government, and their duties. It limits government, listing freedoms or rights reserved for the people, and it must be more difficult to amend or change than ordinary laws. 16

A constitution may be expressed in a way that emphasizes civil liberties as negative or positive rights. When political scientists say a constitution specifies negative rights , this means that it is written to emphasize limitations on government. Consider the wording of the First Amendment :

“ Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” 17 (emphasis added)

The amendment is phrased to focus not on what the government owes the people but on the limitations on the government’s ability to infringe upon the rights of individuals. The US Constitution leans toward being a negative rights constitution because most of the Bill of Rights is written in terms of restrictions on the government.

In a positive rights constitution, rights are written in terms of a government obligation to guarantee the people’s rights. For example, article 5 of the German constitution, the German Basic Law , states:

“Every person shall have the right freely to express and disseminate his opinions in speech, writing and pictures. . . . Freedom of the press . . . shall be guaranteed .” 18 (emphasis added)

This positive rights constitution emphasizes the government’s guarantee of freedom to the individual. Though the US Constitution is primarily seen as a negative rights constitution, like most constitutions it also describes positive rights, as in those clauses that guarantee the right to something. 19 Most democratic constitutions written after World War II are positive rights constitutions. After the Nazis used the existing German constitution to restrict people’s freedoms in Germany and in the countries they conquered, people in the affected countries wanted assurances that the government recognized its obligation to the people and not just the people’s obligation to the government. Similar fears caused many countries not occupied by the Nazis to create positive rights constitutions. 20 These constitutions make the government the protector of freedom against all infringements. They do not just limit government action restricting the individual.

Positive vs. Negative Rights

In this short clip, the Center for Civic Education distinguishes between positive and negative rights.

A country’s constitution delineates the degree of freedom of action that the government allows the individual, and that degree varies by political system. An individualist system emphasizes individuals over the community, including the government, while a communitarian system emphasizes community cohesiveness while recognizing the importance of individual freedoms. Countries vary in terms of the nature of their systems and the degree to which they stress individualism or communitarianism.

What Are the Characteristics of Individualist Systems?

In an individualist system, individuals take precedence over the government. Society rests on the principle that individuals inherently possess rights that the government should preserve and promote. Two major styles of individualism are common today: libertarianism (also called classical liberalism) and modern liberalism . Libertarianism emphasizes restraints on government. Liberalism emphasizes the government’s obligation to enforce laws that protect personal autonomy and rights. Let’s review some of the different philosophies discussed in Chapter 3 in terms of how they impact civil liberties.

In libertarianism, individualists believe that governments exist to assist individuals in achieving their private interests. Therefore, libertarians place many restrictions (negative rights) on the government. As John Stuart Mill observed in his essay On Liberty (1859), in a strict individualist society:

“The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant. He cannot rightfully be compelled to do or forbear because it will be better for him to do so, because it will make him happier, because, in the opinions of others, to do so would be wise, or even right. These are good reasons for remonstrating with him, or reasoning with him, or persuading him, or entreating him, but not for compelling him, or visiting him with any evil in case he do otherwise.” 21

The focus is on the individual, and the benefits to society that might flow from any restriction on the individual must be clear and convincing. This does not mean that the government can never restrict individual action, nor that the good of society need be wholly ignored. Still, it does mean there must be proof of sufficient harmful effects to justify any restraint. This is where the conflict between the individual and society occurs. It is here that the US style of “no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech” comes into play. For example, a person in the United States can say anything against any political candidate; they can even lie about the candidate. 22 With the restriction on government action abridging free speech, no laws restrict that person’s conduct. However, they cannot say they will kill a candidate at three o’clock on Tuesday afternoon. This is a threat to an individual’s safety and to society’s law and order, so the government has laws to punish the person for making the threat. Further, some US statutes make a person liable for damages if they engage in defamation—that is, if they lie about and cause harm to a private person—although these statutes do not apply to lies about political candidates. Thus, even with the United States’ negative rights libertarian-style constitution, the government is not prohibited from imposing restrictions “abridging the freedom of speech” in every situation at all times.

In an individualist society formed in a liberal style, the government actively protects individual rights. For example, under the German Basic Law and its guarantees of free speech, the government can prosecute a person for making false statements or heckling a candidate while they are making a speech. This is a violation of the Basic Law because the rights of free speech “shall find their limits in the provisions of general laws, in provisions for the protection of young persons and in the right to personal honour.” 23 Liberal governments are more proactive than libertarian ones in protecting the individual’s rights. Because they do so to protect the rights of all individuals for the good of society, they place more restrictions on the individual. Still, governments in liberal societies cannot wholly deny a person’s individual liberties.

What Are the Characteristics of Communitarian Systems?

A communitarian system emphasizes the role the government plays in the lives of citizens. Communitarian systems are grounded in the belief that people need the community and its values to create a cohesive society. Government exists not only to protect rights but also to form a political community to solve public problems. There is a public good, and it is the government’s job to protect it, even if that means restricting individual behaviors. Communitarians oppose excessive individualism, arguing that it leads people to be selfish or egocentric, which is harmful to a community. Individuals do not stand apart from society in discrete autonomy; they are part of society and have a role to play in protecting society.

How countries put communitarianism into practice varies widely. Some countries, such as China, Singapore, and Malaysia, have authoritarian governments. This style of government enforces obedience to government authority by strongly limiting personal freedoms. These governments emphasize and enshrine in their constitutions social obligations and the common good. The Chinese constitution states, “Disruption of the socialist system by any organization or individual is prohibited.” 24 In article 35, the Chinese constitution provides that “citizens of the People’s Republic of China enjoy the freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, the procession and demonstration.” 25 However, comparing these two clauses with actual practices in the People's Republic of China shows that the government’s emphasis is not on protecting individual freedom and autonomy but on protecting the government’s view of a cohesive society. 26

Responsive communitarianism contrasts with the authoritarian style of communitarianism and the perceived selfishness of libertarianism. It seeks to blend the common good and individual autonomy while not allowing either to take precedence over the other. The individual is within society, the community, so the community constructs part of the individual identity. In responsive communitarianism , individual rights are balanced with societal norms of the good, and society or the government restrains the individual when individual action challenges an accepted norm. For example, the majority of people living in the United States today oppose slavery and racial injustice. However, had those people been born in the 18th century, many would have supported such concepts. Every community has standards that it declares essential to the common good—the common ground on which the community is formed. In circumstances where the common good takes precedence over the individual, conflict can ensue, and the society, including the government, must decide how to resolve the dispute.

The COVID-19 pandemic mentioned at the beginning of this chapter resulted in severe illness and mass deaths around the world. Many viewed government actions restricting individuals during the pandemic as justified because the challenge the disease posed to society was severe enough to warrant temporarily suspending certain freedoms. People accepted or rejected these government restrictions depending on the degree to which they accepted scientific explanations and on their views of individualism and communitarianism. Scientists explained how the disease spread, and government leaders urged compliance. In many areas of the world, the government instituted restrictions on movement, required that people wear face masks, and punished persons who violated these edicts. Some individuals claimed that their rights were being violated. Some argued that masks do not make a significant difference in transmission of the virus and are unnecessary in most situations. Significant scientific evidence refutes this claim, but such individuals refused to accept it. They also argued that it is their inalienable right to decide whether or not to risk becoming sick or dying, prioritizing that right over the risk they might pose to others. 27 When initial illness rates started to decline and vaccinations became available, the argument shifted to when and how to open up the social sphere and whether to require that people be vaccinated to enter certain places or to participate in certain activities. 28 These responses to the pandemic are a perfect example of the conflicts inherent in everyday situations that require a balance between individuals’ civil liberties and the government’s obligation to act for the common good.

Whether and to what degree a system is individualistic or communitarian does not determine if the system is a constitutional government. Simply having a document labeled a constitution does not give a country a constitutional government; to be considered a constitutional government, a country must practice constitutionalism.

What Is Constitutionalism?

The three main elements of constitutionalism are adherence to the rule of law, limited government, and guarantees of individual rights. The rule of law has four principles:

- Accountability : Government and private actors are accountable under the law, and no one is above the law.

- Just laws : The laws are clear, publicized, stable, and applied evenly. They protect fundamental rights, including protecting persons and property and certain core human rights.

- Open government : The processes by which the laws are enacted, administered, and enforced are accessible, fair, and efficient.

- Accessible and impartial dispute resolution : Justice is delivered in a timely manner by competent, ethical, and independent representatives, and neutral decision makers are accessible, have adequate resources, and reflect the communities they serve.

Constitutionalism balances limited government with the fundamental worth of each individual. The government is limited because people have some right to make their own life decisions. The fundamental worth of each individual means that people have some right to self-determination, as shown in a bill of rights in a constitution. Maintaining a balance between government authority and individual freedom is a challenge.

Utilizing due process is part of the rule of law and constitutionalism, so it is more robustly defended in countries that practice constitutionalism than it is in those with constitutions that do not adhere to all the elements of constitutionalism.

Due process is a legal requirement that the government respect the rights of the people, and it is a demonstration of the rule of law and the balancing of government power with individual rights. In the US Constitution, the due process clause provides that no one shall “be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” 29 This clause applies to all persons, not just citizens of the United States. There are two aspects of due process: procedural due process and substantive due process. Procedural due process concerns the written guidelines for how the government interacts with individuals, while substantive due process concerns the individual’s right to be treated fairly when interacting with the government. A violation of due process offends the rule of law because it puts individuals or groups above the law or treats individuals or groups without equality.

Due Process of Law

In this video clip, Randy E. Barnett, professor of constitutional law at the Georgetown University Law Center, looks at the overarching concept of due process through the lens of US government and its British origins.

When one thinks of the due process of law as government fairness to all persons, civil rights and civil liberties become intertwined. In the landmark same-sex marriage case Obergefell v. Hodges , the United States Supreme Court held that the due process clause of the 14th Amendment guarantees that the government will defend as a fundamental liberty the right to choose whom one will marry. The court also held that to deny that liberty would violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment because doing so would amount to unequal treatment of same-sex and opposite-sex couples, thus denying a same-sex couple equal protection of the law and amounting to a violation of the couple’s civil rights. 30

Thus, same-sex marriage is both a civil liberty and a civil rights issue. The right to marry is a civil liberty because it is a freedom from government interference in one’s choice of a life partner. Same-sex marriage is a civil rights issue because to deny same-sex couples the right to marry is to subject them to unequal treatment. The case of same-sex marriage shows how both civil rights (equality) and civil liberties (freedom from government interference) are a part of the fair government treatment of individuals.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-political-science/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Mark Carl Rom, Masaki Hidaka, Rachel Bzostek Walker

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Political Science

- Publication date: May 18, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-political-science/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-political-science/pages/4-2-constitutions-and-individual-liberties

© Jan 3, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Political Freedom According to Machiavelli and Locke Essay

Introduction.

Political freedom despite its imminent acceptance and popularity among so-called democratic countries has remained subjective and dependent on leaders. This paper shall try to delineate Niccolo Machiavelli’s and John Locke’s interpretation or ideological influence on political freedom.

According to Niccolo Machiavelli, the greatest moral good is a virtuous and stable state so that actions even if cruel, if intended to protect the country are justified. Leaders or state defenders must do anything necessary to keep their power but Machiavelli strongly suggests that above all, the prince must not be hated. He proposed that a wise prince or leader establish himself on where he has control and not in that of others. However, he also wrote that “It is best to be both feared and loved; however, if one cannot be both it is better to be feared than loved,” (The Prince, Chapter __ ).