Home — Essay Samples — Business — Leadership — Authoritarian Leader: Analysis

Authoritarian Leader: Analysis

- Categories: Leadership Leadership Styles

About this sample

Words: 606 |

Published: Mar 20, 2024

Words: 606 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Characteristics of an authoritarian leader, impact of authoritarian leadership, implications for followers and subordinates.

- Centralized Decision-Making: Authoritarian leaders tend to make decisions without seeking input from subordinates or other stakeholders. They often believe that they know what is best for the organization and rely on their own judgment to guide decision-making processes.

- Strict Control: Authoritarian leaders maintain tight control over their subordinates, often using strict rules and regulations to enforce compliance. They may also exert control through fear or intimidation, creating a hierarchical power dynamic within the organization.

- Limited Feedback: Authoritarian leaders are often resistant to feedback or criticism from subordinates. They may view dissenting opinions as a threat to their authority and may punish or marginalize those who challenge their decisions.

- Focus on Authority: Authoritarian leaders prioritize maintaining their authority and control over the organization above all else. They may be less concerned with fostering collaboration or empowering their subordinates, instead prioritizing their own power and status.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Business

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1738 words

1 pages / 666 words

6 pages / 2752 words

2 pages / 785 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Leadership

A personal evaluation of strengths is a tool that must be understood to effectively lead people. An effective leader must know how to reach goals by motivating the team. There are many strengths that translate to leadership [...]

In the military, the main role of the leader includes providing motivation, direction, and purpose to the military while they execute their function or mission at hand. As a leader in the different unit of the army, he or she is [...]

The Profession of Soldiering is among the most noble of professions as it pulls the best and brightest of our society. Those individuals who have a sense of duty, and a desire to serve a greater good, even though it may cost [...]

The new-found success at Disney Co. is mainly attributable to the change of leadership from a structural style in Eisner to a combination of Human resources and symbolic styles in Iger. Although Eisner saw much success with [...]

Leadership is directing a group of people to work together towards a common goal while assuring nobody's fundamental human rights are taken away from them. While reading Lord of the Flies, many teachers and historians argue if [...]

Nonprofit leadership and management is an important area of concern because of the impact of nonprofit organizations on society. The mission statements of most nonprofits are geared towards helping people or addressing a need [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Browse Topics

- Executive Committee

- Affiliated Faculty

- Harvard Negotiation Project

- Great Negotiator

- American Secretaries of State Project

- Awards, Grants, and Fellowships

- Negotiation Programs

- Mediation Programs

- One-Day Programs

- In-House Training and Custom Programs

- In-Person Programs

- Online Programs

- Advanced Materials Search

- Contact Information

- The Teaching Negotiation Resource Center Policies

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Negotiation Journal

- Harvard Negotiation Law Review

- Working Conference on AI, Technology, and Negotiation

- 40th Anniversary Symposium

- Free Reports and Program Guides

Free Videos

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- Event Series

- Our Mission

- Keyword Index

PON – Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School - https://www.pon.harvard.edu

Team-Building Strategies: Building a Winning Team for Your Organization

Discover how to build a winning team and boost your business negotiation results in this free special report, Team Building Strategies for Your Organization, from Harvard Law School.

How an Authoritarian Leadership Style Blocks Effective Negotiation

An authoritarian leadership style tends to cut off communication, information sharing, and trust building. as a result, it can backfire on the powerful and prevent win-win agreements..

By Katie Shonk — on October 31st, 2023 / Leadership Skills

Those who favor an authoritarian leadership style, also known as an autocratic leadership style , tend to believe their approach to management is more efficient and decisive than a more collaborative leadership style. But because a top-down approach can heighten the power differential between leaders and those who report to them, it often backfires, generating resentment and ill will among followers. In particular, highlighting the role of leadership in negotiation , an authoritarian leadership style may cause leaders to miss out on opportunities to reach mutually beneficial agreements, both inside their organization and beyond.

Claim your FREE copy: Real Leaders Negotiate

If you aspire to be a great leader, not just a boss, start here: Download our FREE Special Report, Real Leaders Negotiate: Understanding the Difference between Leadership and Management , from Harvard Law School.

A Top-Down Style

Since taking office in 2019, Florida’s Republican governor, Ron DeSantis, has worked with the state legislature to consolidate power at the state level while also blocking local public-health mandates during the Covid-19 pandemic, as an article on DeSantis’s leadership style in the Washington Post reports.

Many Republicans in Florida and beyond view DeSantis as an effective leader who has pushed back against what they view as overreactions to the Covid-19 pandemic by mayors and other officials. But some local leaders in Florida have been frustrated by what they see as DeSantis’s top-down leadership style and insufficient communication. For example, speaking to the Post, Hialeah mayor Carlos Hernandez, a Republican, called DeSantis “a dictator,” while Democratic St. Petersburg mayor Rick Kriseman said he had never been able to reach the governor on the phone.

Lack of communication, a hallmark of an authoritarian leadership style, frequently backfires on leaders, as followers often resist complying with orders they don’t understand or support.

Unchecked Power

A top-down, or authoritarian, leadership style is often carried out in a fully professional manner. But at times, an authoritarian leadership style can cross the line into unfair and even abusive behavior.

Take the case of another recent U.S. governor, Andrew Cuomo, who resigned after numerous employees accused him of fostering a toxic workplace culture. According to a state investigation , Cuomo sexually harassed 11 women while in office. And many people who worked for Cuomo, men and women alike, have accused him of creating a toxic workplace where he regularly yelled at and insulted employees.

Cuomo’s replacement, Kathy Hochul, told the New York Times she would bring a “collaborative approach to government,” saying she was “hard-wired to view everything that Albany does through the lens of a local town, city, county official.” She added, “I know that is going to be a breath of fresh air.”

How Does an Authoritarian Leadership Style Affect Negotiation?

Notably, an authoritarian leadership style is often at odds with best practices for leadership and negotiation. Consider that those who favor an authoritarian style tend to be powerful leaders negotiating with less powerful parties. In their approach to negotiation and leadership, the powerful often veer toward asserting their will—and make the following mistakes:

They underestimate those with less power. Powerful negotiators tend to discount the power of less powerful players, Notre Dame professor Ann E. Tenbrunsel and the late Northwestern University professor David Messick found in their research. Overly self-confident perceptions can lead powerful negotiators to offer fewer concessions than needed to get a deal and to treat others with less respect and recognition than they may deserve. The result? Impasse, suboptimal deals, or retaliation by the less powerful.

They are less prepared. The key to negotiation success is preparation, yet powerful negotiators often tend to undervalue the need to thoroughly prepare to negotiate, according to Tenbrunsel. Those with power are more likely to fall back on cognitive shortcuts when processing information—which leads them to ignore their counterparts’ interests and pass up opportunities to create value for both sides. The powerful, including authoritarians, may also end up being out-strategized by counterparts who spent more time preparing to negotiate.

They fail to anticipate a backlash. Power can trigger resentment, jealousy, and competitiveness in those with less power. As a result, parties with less power are likely to approach negotiations with more powerful parties more aggressively than they would negotiations with less powerful parties. But the powerful are often unaware that they tend to inspire animosity, Tenbrunsel and Messick found in their research; in fact, the more powerful people are, the more trustworthy they expect others to be. Yet those with an authoritarian leadership style are unlikely to take the time needed to build trust with negotiating partners. As a result, they could find that their counterparts are less trustworthy than they expected them to be.

For these reasons and others, an authoritarian leadership style is typically antithetical to effective negotiation . Generally, leaders will benefit from taking a more collaborative approach to leadership and negotiation. That includes taking time to build trusting relationships, preparing thoroughly for negotiation, and never underestimating counterparts. In addition, it means approaching both leadership and negotiation with humility, understanding that everyone has something to contribute and that power can be measured in different ways.

By shifting their stance toward collaboration and cooperation, the powerful will not only set themselves up to construct win-win agreements but also embody more effective leadership.

Have you had experience with an authoritarian leadership style? If so, how did it affect negotiations in your organization or industry?

Related Posts

- Paternalistic Leadership: Beyond Authoritarianism

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Leadership Styles: Uncovering Bias and Generating Mutual Gains

- The Contingency Theory of Leadership: A Focus on Fit

- Servant Leadership and Warren Buffett’s Giving Pledge

- How to Negotiate in Cross-Cultural Situations

Click here to cancel reply.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Negotiation and Leadership

- Learn More about Negotiation and Leadership

NEGOTIATION MASTER CLASS

- Learn More about Harvard Negotiation Master Class

Negotiation Essentials Online

- Learn More about Negotiation Essentials Online

Beyond the Back Table: Working with People and Organizations to Get to Yes

- Download Program Guide: March 2024

- Register Online: March 2024

- Learn More about Beyond the Back Table

Select Your Free Special Report

- Negotiation and Leadership Fall 2024 Program Guide

- Negotiation Essentials Online (NEO) Spring 2024 Program Guide

- Beyond the Back Table Spring 2024 Program Guide

- Negotiation Master Class May 2024 Program Guide

- Negotiation and Leadership Spring 2024 Program Guide

- Make the Most of Online Negotiations

- Managing Multiparty Negotiations

- Getting the Deal Done

- Salary Negotiation: How to Negotiate Salary: Learn the Best Techniques to Help You Manage the Most Difficult Salary Negotiations and What You Need to Know When Asking for a Raise

- Overcoming Cultural Barriers in Negotiation: Cross Cultural Communication Techniques and Negotiation Skills From International Business and Diplomacy

Teaching Negotiation Resource Center

- Teaching Materials and Publications

Stay Connected to PON

Preparing for negotiation.

Understanding how to arrange the meeting space is a key aspect of preparing for negotiation. In this video, Professor Guhan Subramanian discusses a real world example of how seating arrangements can influence a negotiator’s success. This discussion was held at the 3 day executive education workshop for senior executives at the Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School.

Guhan Subramanian is the Professor of Law and Business at the Harvard Law School and Professor of Business Law at the Harvard Business School.

Articles & Insights

- Negotiation Examples: How Crisis Negotiators Use Text Messaging

- For Sellers, The Anchoring Effects of a Hidden Price Can Offer Advantages

- BATNA Examples—and What You Can Learn from Them

- Taylor Swift: Negotiation Mastermind?

- Power and Negotiation: Advice on First Offers

- How to Negotiate in Good Faith

- How to Deal with Cultural Differences in Negotiation

- Dear Negotiation Coach: Coping with a Change-of-Control Provision

- The Importance of Negotiation in Business and Your Career

- Negotiation in Business: Starbucks and Kraft’s Coffee Conflict

- Advanced Negotiation Strategies and Concepts: Hostage Negotiation Tips for Business Negotiators

- Negotiating the Good Friday Agreement

- Communication and Conflict Management: Responding to Tough Questions

- How to Maintain Your Power While Engaging in Conflict Resolution

- Conflict-Management Styles: Pitfalls and Best Practices

- Negotiating Change During the Covid-19 Pandemic

- AI Negotiation in the News

- Crisis Communication Examples: What’s So Funny?

- Crisis Negotiation Skills: The Hostage Negotiator’s Drill

- Police Negotiation Techniques from the NYPD Crisis Negotiations Team

- Managing Difficult Employees, and Those Who Just Seem Difficult

- How to Deal with Difficult Customers

- Negotiating with Difficult Personalities and “Dark” Personality Traits

- Consensus-Building Techniques

- Ethics in Negotiations: How to Deal with Deception at the Bargaining Table

- Understanding Exclusive Negotiation Periods in Business Negotiations

- Perspective Taking and Empathy in Business Negotiations

- Dealmaking and the Anchoring Effect in Negotiations

- Negotiating Skills: Learn How to Build Trust at the Negotiation Table

- How to Counter Offer Successfully With a Strong Rationale

- What is Alternative Dispute Resolution?

- Alternative Dispute Resolution Examples: Restorative Justice

- Choose the Right Dispute Resolution Process

- Union Strikes and Dispute Resolution Strategies

- What Is an Umbrella Agreement?

- The Pros and Cons of Back-Channel Negotiations

- Overcoming Cultural Barriers in Negotiations and the Importance of Communication in International Business Deals

- Managing Cultural Differences in Negotiation

- Top 10 International Business Negotiation Case Studies

- Hard Bargaining in Negotiation

- Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) Training: Mediation Curriculum

- What Makes a Good Mediator?

- Why is Negotiation Important: Mediation in Transactional Negotiations

- The Mediation Process and Dispute Resolution

- Negotiations and Logrolling: Discover Opportunities to Generate Mutual Gains

- Finding Mutual Gains In “Non-Negotiation”

- Appealing to Sympathy When Dealing with Difficult Situations

- Negotiation Skills: How to Become a Negotiation Master

- The Benefits of Coalitions at the Bargaining Table

- Identify Your Negotiation Style: Advanced Negotiation Strategies and Concepts

- Negotiation Journal celebrates 40th anniversary, new publisher, and diamond open access in 2024

- Ethics and Negotiation: 5 Principles of Negotiation to Boost Your Bargaining Skills in Business Situations

- 10 Negotiation Training Skills Every Organization Needs

- Trust in Negotiation: Does Gender Matter?

- Use a Negotiation Preparation Worksheet for Continuous Improvement

- How to Negotiate Pay in an Interview

- How to Negotiate a Higher Salary

- Renegotiate Salary to Your Advantage

- How to Counter a Job Offer: Avoid Common Mistakes

- Salary Negotiation: How to Ask for a Higher Salary

- Check Out Videos from the PON 40th Anniversary Symposium

- Check Out the All-In-One Curriculum Packages!

- Teach Your Students to Negotiate Cross-Border Water Conflicts

- Asynchronous Learning: Negotiation Exercises to Keep Students Engaged Outside the Classroom

- Planning for Cyber Defense of Critical Urban Infrastructure

- What is a Win-Win Negotiation?

- How to Win at Win-Win Negotiation

- Labor Negotiation Strategies

- How to Create Win-Win Situations

- For NFL Players, a Win-Win Negotiation Contract Only in Retrospect?

PON Publications

- Negotiation Data Repository (NDR)

- New Frontiers, New Roleplays: Next Generation Teaching and Training

- Negotiating Transboundary Water Agreements

- Learning from Practice to Teach for Practice—Reflections From a Novel Training Series for International Climate Negotiators

- Insights From PON’s Great Negotiators and the American Secretaries of State Program

- Gender and Privilege in Negotiation

Remember Me This setting should only be used on your home or work computer.

Lost your password? Create a new password of your choice.

Copyright © 2024 Negotiation Daily. All rights reserved.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Autocratic Leadership?

Characteristics, Strengths, and Weaknesses of Autocratic Leadership

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

- Characteristics

Are You an Autocratic Leader?

Autocratic leadership, also known as authoritarian leadership, is a leadership style characterized by individual control over all decisions and little input from group members.

Autocratic leaders typically make choices based on their ideas and judgments and rarely accept advice from followers. Autocratic leadership involves absolute, authoritarian control over a group.

Like other leadership styles, the autocratic style has both some benefits and some weaknesses. While those who rely on this approach too heavily are often seen as bossy or dictator-like, this level of control can have benefits and be useful in certain situations.

When and where the authoritarian style is most useful can depend on factors such as the situation , the type of task the group is working on, and characteristics of the team members. If you tend to utilize this type of leadership with a group, learning more about your style and the situations in which this style is the most effective can be helpful.

Characteristics of Autocratic Leadership

Some of the primary characteristics of autocratic leadership include:

- Allows little or no input from group members

- Requires leaders to make almost all of the decisions

- Provides leaders with the ability to dictate work methods and processes

- Leaves the group feeling like they aren't trusted with decisions or important tasks

- Tends to create highly structured and very rigid environments

- Discourages creativity and out-of-the-box thinking

- Establishes rules and tends to be clearly outlined and communicated

There are also three primary types of autocratic leadership: Directing (rigid), permissive (slightly more flexible), and paternalistic (strict but balanced with care and concern).

Allows for quick decision-making especially in stress-filled situations

Offers a clear chain of command or oversight

Works well where strong, directive leadership is needed

Discourages group input

Hurts morale and leads to resentment

Ignores or impairs creative solutions and expertise from subordinates

Benefits of Autocratic Leadership

The autocratic style tends to sound quite negative. It certainly can be when overused or applied to the wrong groups or situations. However, autocratic leadership can be beneficial in some instances, such as when decisions need to be made quickly without consulting with a large group of people.

Some projects require strong leadership to get things accomplished quickly and efficiently. When the leader is the most knowledgeable person in the group, the autocratic style can lead to fast and effective decisions. The autocratic leadership style can be useful in the following instances:

Provides Direction

Autocratic leadership can be effective in small groups where leadership is lacking . Have you ever worked with a group of students or co-workers on a project that got derailed by poor organization, a lack of leadership and an inability to set deadlines?

If so, the chances are that your grade or job performance suffered as a result. In such situations, a strong leader who utilizes an autocratic style can take charge of the group, assign tasks to different members, and establish solid deadlines for projects to be finished.

These types of group projects tend to work better when one person is either assigned the role of leader or simply takes on the job on their own. By setting clear roles, assigning tasks, and establishing deadlines, the group is more likely to finish the project on time and with everyone providing equal contributions.

Relieves Pressure

This leadership style can also be used well in cases where a great deal of pressure is involved. In situations that are particularly stressful, such as during military conflicts, group members may prefer an autocratic style.

This allows members of the group to focus on performing specific tasks without worrying about making complex decisions. This also allows group members to become highly skilled at performing certain duties, which is ultimately beneficial to the success of the entire group.

Offers Structure

Manufacturing and construction work can also benefit from the autocratic style. In these situations, it is essential that each person have a clearly assigned task, a deadline, and rules to follow.

Autocratic leaders tend to do well in these settings because they ensure that projects are finished on time and that workers follow safety rules to prevent accidents and injuries.

Downsides of Autocratic Leadership

While autocratic leadership can be beneficial at times, there are also many instances where this leadership style can be problematic. People who abuse an autocratic leadership style are often viewed as bossy, controlling, and dictatorial. This can sometimes result in resentment among group members.

Group members can end up feeling that they have no input or say in how things or done, and this can be particularly problematic when skilled and capable members of a team are left feeling that their knowledge and contributions are undermined. Some common problems with autocratic leadership:

Discourages Group Input

Because autocratic leaders make decisions without consulting the group, people in the group may dislike that they are unable to contribute ideas. Researchers have also found that autocratic leadership often results in a lack of creative solutions to problems, which can ultimately hurt the group from performing.

Autocratic leaders tend to overlook the knowledge and expertise that group members might bring to the situation. Failing to consult with other team members in such situations hurts the overall success of the group.

Hurts Morale

Autocratic leadership can also impair the morale of the group in some cases. People tend to feel happier and perform better when they feel like they are making contributions to the future of the group. Since autocratic leaders typically do not allow input from team members, followers start to feel dissatisfied and stifled.

Is autocratic leadership good or bad?

Autocratic leadership is generally a bad thing when it is used excessively. However, it is important to note that this type of leadership can be useful in certain situations. When group members lack knowledge, need direction, and time is of the essence, autocratic leadership can provide guidance, relieve pressure, and offer the structure that group members need to succeed.

How to Be Successful With Autocratic Leadership

The autocratic style can be beneficial in some settings, but also has its pitfalls and is not appropriate for every setting and with every group. If this tends to be your dominant leadership style, there are things that you should consider whenever you are in a leadership role.

Listen to Team Members

You might not change your mind or implement their advice, but subordinates need to feel that they can express their concerns. Autocratic leaders can sometimes make team members feel ignored or even rejected.

Listening to people with an open mind can help them feel like they are making an important contribution to the group's mission.

Establish Clear Rules

In order to expect team members to follow your rules, you need to first ensure that guidelines are clearly established and that each person on your team is fully aware of them.

Provide Tools

Once your subordinates understand the rules, you need to be sure that they actually have the education and abilities to perform the tasks you set before them. If they need additional assistance, offer oversight and training to fill in this knowledge gap.

Be Reliable

Inconsistent leaders can quickly lose the respect of their teams. Follow through and enforce the rules you have established. Establish that you are a reliable leader and your team is more likely to follow your guidance because you have built trust with them.

Recognize Success

Your team may quickly lose motivation if they are only criticized when they make mistakes but never rewarded for their successes. Try to recognize success more than you point out mistakes. By doing so, your team will respond much more favorably to your correction.

Try our fast and free quiz to find out if you tend towards autocratic leadership or one of the other styles.

While autocratic leadership does have some potential pitfalls, leaders can learn to use elements of this style wisely. For example, an autocratic style can be used effectively in situations where the leader is the most knowledgeable member of the group or has access to information that other members of the group do not.

Instead of wasting valuable time consulting with less knowledgeable team members, the expert leader can quickly make decisions that are in the best interest of the group. Autocratic leadership is often most effective when it is used for specific situations. Balancing this style with other approaches including democratic or transformational styles can often lead to better group performance.

Wang H, Guan B. The positive effect of authoritarian leadership on employee performance: The moderating role of power distance . Front Psychol. 2018;9:357. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00357

St. Thomas University. What is autocratic leadership? How procedures can improve efficiency .

Rosing F, Boer D, Buengeler C. When timing is key: How autocratic and democratic leadership relate to follower trust in emergency contexts . Front Psychol . 2022;13:904605. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.904605

- Cragen, JF, Wright, DW, & Kasch, CR. Communication in Small Groups: Theory, Process, and Skills. Boston: Wadsworth; 2009.

- Daft, RL. The Leadership Experience. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning; 2015.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

The virtue of a controlling leadership style: Authoritarian leadership, work stressors, and leader power distance orientation

- Published: 19 November 2022

Cite this article

- Leni Chen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8268-8117 1 ,

- Xu Huang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3472-6822 2 ,

- Jian-min Sun ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7696-3231 3 ,

- Yuyan Zheng ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9340-4626 4 ,

- Les Graham ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0560-2305 5 &

- Judy Jiang 6

1958 Accesses

Explore all metrics

This article has been updated

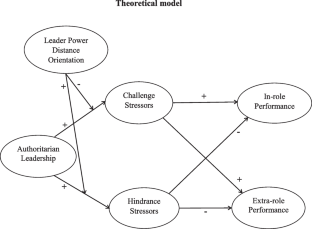

We developed and tested a theoretical model showing that authoritarian leadership has both positive and negative influences on employees’ work performance. We posited that authoritarian leadership may shape both challenge stressors and hindrance stressors, which compel and undermine in-role and extra-role performance, respectively. We found consistent results across two studies. In Study 1, our results from two samples in different cultures showed that authoritarian leadership was positively related to objective performance (Sample 1: n = 402 Chinese chain restaurant managers) and extra-role performance (Sample 2: n = 369 U.K. police officers) via challenge stressors. Authoritarian leadership was negatively related to objective performance and extra-role performance via hindrance stressors. In Study 2 (n = 195 Chinese power industry employees), we replicated the findings of Study 1. Further, we found that authoritarian leadership behaviors among leaders who scored low on power distance orientation were not negatively related to in-role and extra-role performance via hindrance stressors.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Whipping into shape: Construct definition, measurement, and validation of directive-achieving leadership in Chinese culture

Tingting Chen, Fuli Li & Kwok Leung

Authoritarian leadership styles and performance: a systematic literature review and research agenda

Elia Pizzolitto, Ida Verna & Michelina Venditti

Authoritarian leadership and task performance: the effects of leader-member exchange and dependence on leader

Zhen Wang, Yuan Liu & Songbo Liu

Availability of data and material

The raw data from Study 1a and Study 2 are available and will be submitted to the reviewers when they request it. The raw data from Study 1b are not available because participants are police officers and we signed a contract with a confidentiality clause specifying that we cannot share the raw data with others.

Code availability

All Mplus input and output codes are available and will be submitted to the reviewers when they request them.

Change history

25 november 2022.

The original version of this paper was updated to reflect the ORCID ID of authors Xu Huang, Jian-min Sun, Yuyan Zheng, and Les Graham.

We calculated the statistical power of our model in the three samples following Faul et al., (2007). In each case, the statistical power was above the threshold of .80. Specifically, in Sample 1 , the results showed a statistical power of .87 for the mediating effects of authoritarian leadership on in-role performance via the two stressors. In Sample 2 , the statistical power for the mediating effects on extra-role performance was .99. In Sample 3, the statistical power for the mediating effects on in-role performance was .95 and for extra-role performance, it was .99. The statistical power for the moderating effect of leaders’ power distance orientation on the relationship between authoritarian leadership and hindrance stressors was .99.

We ran several additional analyses using our samples to prove that challenge/hindrance stressor framework works better for authoritarian leadership than for other leadership styles. We aimed to examine (1) whether the challenge/hindrance stressor framework could work for other leadership styles and (2) whether the challenge/hindrance stressor framework could still work for authoritarian leadership after controlling for other leadership styles. Therefore, we examined the effects of transformational, benevolent, and moral leadership on work performance via shaping challenge and hindrance stressors. We also retested our theoretical model after controlling for the effects of transformational leadership (Sample 1), benevolent leadership (Sample 3), and moral leadership (Sample 3).

The results showed that transformational leadership was not related to challenge stressors ( B = -.19, SE = .17, n.s. ), but it was negatively related to hindrance stressors ( B = -.60 , SE = .18 , p < .01). Benevolent leadership was not related to challenge stressors (B = -.17, SE = .20, n.s .), but it was negatively related to hindrance stressors ( B = -.42, SE = .21, p < .05). Moral leadership was not related to either challenge stressors ( B = -.13, SE = .22, n.s .) or hindrance stressors ( B = -.15, SE = .21, n.s. ). Further, after controlling for benevolent and moral leadership, the indirect effects of authoritarian leadership on in-role performance ( B = .08, SE = .04, 95% CI = [.01, .17]) and extra-role performance ( B = .06, SE = .03, 95% CI = [.01, .13]) via challenge stressors were significant. Also, after controlling for transformational leadership, the indirect effect of authoritarian leadership on in-role performance via challenge stressors was significant ( B = .03, SE = .02, 95% CI = [.001, .06]).

Overall, we found no empirical evidence that challenge/hindrance stressors function as the underlying mechanisms for the effects of transformational, benevolent, or moral leadership on in-role and extra-role performance. Furthermore, most of our hypotheses held after controlling for other leadership styles. These results indicate that challenge and hindrance stressors may be distinct mechanisms that transmit the effects of authoritarian leadership to performance.

We used employee power distance orientation instead of leaders’ power distance orientation as the moderator in our model. The results showed that the moderating effects of employee power distance orientation are not significant on either the relationship between authoritarian leadership and challenge stressors ( B = -.38, SE = .25, n.s. ) or the relationship between authoritarian leadership and hindrance stressors ( B = -.09, SE = .22, n.s. ). Therefore, we cannot find evidence supporting moderating effects of employee power distance orientation.

Ashford, S. J., Sutcliffe, K. M., & Christianson, M. K. (2009). Speaking up and speaking out: The leadership dynamics of voice in organizations. In J. Greenberg & M. S. Edwards (Eds.), Voice and silence in organizations (pp. 175–202). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group.

Google Scholar

Bagozzi, R. P., & Edwards, J. R. (1998). A general approach for representing constructs in organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 1 (1), 45–87.

Bamberger, P., & Belogolovsky, E. (2017). The dark side of transparency: How and when pay administration practices affect employee helping. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102 (4), 658–671.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44 (1), 1–26.

Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K., & Strauss, J. P. (1993). Conscientiousness and performance of sales representatives: Test of the mediating effects of goal setting. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78 (5), 715–722.

Bass, B. M., & Bass, R. (2009). The Bass handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications . Simon and Schuster.

Bauer, D. J., Preacher, K. J., & Gil, K. M. (2006). Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 11 (2), 142–163.

Brass, D. J., & Burkhardt, M. E. (1993). Potential power and power use: An investigation of structure and behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 36 (3), 441–470.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (pp. 389–444). Allyn & Bacon.

Brockner, J., Ackerman, G., Greenberg, J., Gelfand, M. J., Francesco, A. M., Chen, Z. X., & Shapiro, D. (2001). Culture and procedural justice: The influence of power distance on reactions to voice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37 (4), 300–315.

Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., & Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among US managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85 (1), 65–74.

Chan, S. C., & Mak, W. M. (2012). Benevolent leadership and follower performance: The mediating role of leader–member exchange (LMX). Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 29 (2), 285–301.

Chan, S. C., Huang, X., Snape, E., & Lam, C. K. (2013). The Janus face of paternalistic leaders: Authoritarianism, benevolence, subordinates’ organization-based self-esteem, and performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34 (1), 108–128.

Che, X. X., Zhou, Z. E., Kessler, S. R., & Spector, P. E. (2017). Stressors beget stressors: The effect of passive leadership on employee health through workload and work–family conflict. Work & Stress, 31 (4), 338–354.

Chen, Z. X., Tsui, A. S., & Farh, J. L. (2002). Loyalty to supervisor vs. organizational commitment: Relationships to employee performance in China. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 75 (3), 339–356.

Chen, Z., Takeuchi, R., & Shum, C. (2013). A social information processing perspective of coworker influence on a focal employee. Organization Science, 24 (6), 1618–1639.

Chen, X. P., Eberly, M. B., Chiang, T. J., Farh, J. L., & Cheng, B. S. (2014). Affective trust in Chinese leaders: Linking paternalistic leadership to employee performance. Journal of Management, 40 (3), 796–819.

Cheng, B., Chou, L., Wu, T. Y., Huang, M. P., & Farh, J. L. (2004). Paternalistic leadership and subordinate responses: Establishing a leadership model in Chinese organizations. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 7 (1), 89–117.

Cheng, B. S., Boer, D., Chou, L. F., Huang, M. P., Yoneyama, S., Shim, D., Sun, J. M., Lin, T. T., Chou, W. J., & Tsai, C. Y. (2014). Paternalistic leadership in four East Asian societies: Generalizability and cultural differences of the triad model. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45 (1), 82–90.

Cheung, G. W., & Lau, R. S. (2017). Accuracy of parameter estimates and confidence intervals in moderated mediation models: A comparison of regression and latent moderated structural equations. Organizational Research Methods, 20 (4), 746–769.

Chou, W. J., Chou, L. F., Cheng, B. S., & Jen, C. K. (2010). Juan-chiuan and shang-yan: The components of authoritarian leadership. Indigenous Psychological Research in Chinese Societies, 34 , 223–284.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

Chou, W. J., Sibley, C. G., Liu, J. H., Lin, T. T., & Cheng, B. S. (2015). Paternalistic leadership profiles: A person-centered approach. Group & Organization Management, 40 (5), 685–710.

Clugston, M., Howell, J. P., & Dorfman, P. W. (2000). Does cultural socialization predict multiple bases and foci of commitment? Journal of Management, 26 (1), 5–30.

Conway, J. M., & Lance, C. E. (2010). What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25 (3), 325–334.

Costa, P. T., Jr., McCrae, R. R., & Dye, D. A. (1991). Facet scales for agreeableness and conscientiousness: A revision of the NEO Personality Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 12 (9), 887–898.

Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95 (5), 834–848.

De Cremer, D. (2006). Affective and motivational consequences of leader self-sacrifice: The moderating effect of autocratic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 17 (1), 79–93.

De Hoogh, A. H., Greer, L. L., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2015). Diabolical dictators or capable commanders? An investigation of the differential effects of autocratic leadership on team performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 26 (5), 687–701.

Den Hartog, D. N., & De Hoogh, A. H. (2009). Empowering behavior and leader fairness and integrity: Studying perceptions of ethical leader behavior from a levels-of-analysis perspective. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 18 (2), 199–230.

Dorfman, P. W., & Howell, J. P. (1988). Dimensions of national culture and effective leadership patterns: Hofstede revisited. Advances in International Comparative Management, 3 , 127–150.

Dorfman, P. W., Howell, J. P., Hibino, S., Lee, J. K., Tate, U., & Bautista, A. (1997). Leadership in western and Asian countries: Commonalities and differences in effective leadership processes across cultures. Leadership Quarterly, 8 (3), 233–274.

Eatough, E. M., Chang, C. H., Miloslavic, S. A., & Johnson, R. E. (2011). Relationships of role stressors with organizational citizenship behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96 (3), 619–632.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12 (1), 1–22.

Farh, J. L., & Cheng, B. S. (2000). A cultural analysis of paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations. In J. T. Li, A. S. Tsui, & E. Weldon (Eds.), Management and organizations in the Chinese context (pp. 84–127). MacMillan.

Farh, J. L., Hackett, R. D., & Liang, J. (2007). Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support–employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Academy of Management Journal, 50 (3), 715–729.

Fernet, C., Trépanier, S. G., Austin, S., Gagné, M., & Forest, J. (2015). Transformational leadership and optimal functioning at work: On the mediating role of employees’ perceived job characteristics and motivation. Work & Stress, 29 (1), 11–31.

Fernet, C. & Austin, S. (2014). Self-Determination and Job Stress 14. The Oxford handbook of work engagement, motivation, and self-determination theory (pp.231–244). Oxford University Press.

Ferris, G. R., Frink, D. D., Galang, M. C., Zhou, J., Kacmar, K. M., & Howard, J. L. (1996). Perceptions of organizational politics: Prediction, stress-related implications, and outcomes. Human Relations, 49 (2), 233–266.

Fox, S., Spector, P. E., Goh, A., & Bruursema, K. (2007). Does your coworker know what you’re doing? Convergence of self-and peer-reports of counterproductive work behavior. International Journal of Stress Management, 14 (1), 41–60.

Fu, P. P., Tsui, A. S., Liu, J., & Li, L. (2010). Pursuit of whose happiness? Executive leaders’ transformational behaviors and personal values. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55 (2), 222–254.

Gellatly, I. R. (1996). Conscientiousness and task performance: Test of cognitive process model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81 (5), 474–482.

Gillet, N., & Vandenberghe, C. (2014). Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: The mediating role of job characteristics. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 25 (3), 321–347.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience . Harvard University Press.

Graen, G. B. & Scandura, T. A. (1987). Toward a psychology of dyadic organizing. Research in Organizational Behavior, 9 , 175–208.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6 (2), 219–247.

Greco, L. M., & Kraimer, M. L. (2020). Goal-setting in the career management process: An identity theory perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105 (1), 40–57.

Griffin, R. W. (1983). Objective and social sources of information in task redesign: A field experiment. Administrative Science Quarterly , 28 (2), 184–200.

Gu, J., Wang, G., Liu, H., Song, D., & He, C. (2018). Linking authoritarian leadership to employee creativity: The influences of leader–member exchange, team identification and power distance. Chinese Management Studies, 12 (2), 384–406.

Gu, Q., Hempel, P. S., & Yu, M. (2020). Tough love and creativity: How authoritarian leadership tempered by benevolence or morality influences employee creativity. British Journal of Management, 31 (2), 305–324.

Guo, L., Decoster, S., Babalola, M. T., De Schutter, L., Garba, O. A., & Riisla, K. (2018). Authoritarian leadership and employee creativity: The moderating role of psychological capital and the mediating role of fear and defensive silence. Journal of Business Research, 92 , 219–230.

Harms, P. D., Wood, D., Landay, K., Lester, P. B., & Lester, G. V. (2018). Autocratic leaders and authoritarian followers revisited: A review and agenda for the future. The Leadership Quarterly, 29 (1), 105–122.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture and organizations. International Studies of Management & Organization, 10 (4), 15–41.

Hofstede, G. H. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, be- haviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Empirical models of cultural differences . In N. Bleichrodt & P. J. D. Dreuth (Eds.), Contemporary issues in cross- cultural psychology (pp. 4–20). Lisse, the Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Hu, J., Erdogan, B., Jiang, K., Bauer, T. N., & Liu, S. (2018). Leader humility and team creativity: The role of team information sharing, psychological safety, and power distance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103 (3), 313–323.

Huang, X., Iun, J., Liu, A., & Gong, Y. (2010). Does participative leadership enhance work performance by inducing empowerment or trust? The differential effects on managerial and non-managerial subordinates. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31 (1), 122–143.

Huang, X., Xu, E., Chiu, W., Lam, C., & Farh, J. L. (2015). When authoritarian leaders outperform transformational leaders: Firm performance in a harsh economic environment. Academy of Management Discoveries, 1 (2), 180–200.

Judge, T. A., Piccolo, R. F., & Ilies, R. (2004). The forgotten ones? The validity of consideration and initiating structure in leadership research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89 (1), 36–51.

Kenward, M. G., & Molenberghs, G. (1998). Likelihood based frequentist inference when data are missing at random. Statistical Science, 13 (3), 236–247.

Kirkman, B. L., Chen, G., Farh, J. L., Chen, Z. X., & Lowe, K. B. (2009). Individual power distance orientation and follower reactions to transformational leaders: A cross-level, cross-cultural examination. Academy of Management Journal, 52 (4), 744–764.

Kluckhohn, C. (1951). Values and value-orientations in the theory of action: An exploration in definition and classification. Toward a general theory of action (pp. 388–433). Harvard University Press.

Koene, B. A., Vogelaar, A. L., & Soeters, J. L. (2002). Leadership effects on organizational climate and financial performance: Local leadership effect in chain organizations. The Leadership Quarterly, 13 (3), 193–215.

Kossek, E. E., Ruderman, M. N., Braddy, P. W., & Hannum, K. M. (2012). Work–nonwork boundary management profiles: A person-centered approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81 (1), 112–128.

Lacerenza, C. N., Reyes, D. L., Marlow, S. L., Joseph, D. L., & Salas, E. (2017). Leadership training design, delivery, and implementation: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102 (12), 1686–1718.

Lau, D. C., Liu, J., & Fu, P. P. (2007). Feeling trusted by business leaders in China: Antecedents and the mediating role of value congruence. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24 (3), 321–340.

Lee, K., & Allen, N. J. (2002). Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87 (1), 131–142.

LePine, J. A., Podsakoff, N. P., & LePine, M. A. (2005). A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 48 (5), 764–775.

LePine, M. A., Zhang, Y., Crawford, E. R., & Rich, B. L. (2016). Turning their pain to gain: Charismatic leader influence on follower stress appraisal and job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 59 (3), 1036–1059.

Leslie, L. M., Manchester, C. F., Park, T. Y., & Mehng, S. A. (2012). Flexible work practices: A source of career premiums or penalties? Academy of Management Journal, 55 (6), 1407–1428.

Li, Y., & Sun, J. M. (2015). Traditional Chinese leadership and employee voice behavior: A cross-level examination. The Leadership Quarterly, 26 (2), 172–189.

Li, R., Chen, Z., Zhang, H., & Luo, J. (2021). How do authoritarian leadership and abusive supervision jointly thwart follower proactivity? A social control perspective. Journal of Management, 47 (4), 930–956.

Lin, C. P., Xian, J., Li, B., & Huang, H. (2020). Transformational leadership and employees’ thriving at work: The mediating roles of challenge-hindrance stressors. Frontiers in Psychology, 11 , 1400.

Lorinkova, N. M., Pearsall, M. J., & Sims, H. P., Jr. (2013). Examining the differential longitudinal performance of directive versus empowering leadership in teams. Academy of Management Journal, 56 (2), 573–596.

Lu, J., Zhang, Z., & Jia, M. (2019). Does servant leadership affect employees’ emotional labor? A social information-processing perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 159 (2), 507–518.

Mackey, J. D., Frieder, R. E., Brees, J. R., & Martinko, M. J. (2017). Abusive supervision: A meta-analysis and empirical review. Journal of Management, 43 (6), 1940–1965.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39 (1), 99–128.

Martin, S. L., Liao, H., & Campbell, E. M. (2013). Directive versus empowering leadership: A field experiment comparing impacts on task proficiency and proactivity. Academy of Management Journal, 56 (5), 1372–1395.

McGrath, R. G., MacMillan, I. C., Yang, E. A. Y., & Tsai, W. (1992). Does culture endure, or is it malleable? Issues for entrepreneurial economic development. Journal of Business Venturing, 7 (6), 441–458.

McNeely, B. L., & Meglino, B. M. (1994). The role of dispositional and situational antecedents in prosocial organizational behavior: An examination of the intended beneficiaries of prosocial behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79 (6), 836–844.

Mooney, C. F., Mooney, C. L., Mooney, C. Z., Duval, R. D., & Duvall, R. (1993). Bootstrapping: A nonparametric approach to statistical inference . Sage.

Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. (2015). Mplus. The comprehensive modelling program for applied researchers: user’s guide , 5 .

Ohly, S., & Fritz, C. (2010). Work characteristics, challenge appraisal, creativity, and proactive behavior: A multi-level study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31 (4), 543–565.

Organ, D. W., & Konovsky, M. (1989). Cognitive versus affective determinants of organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74 (1), 157–164.

Parasuraman, S., & Alutto, J. A. (1981). An examination of the organizational antecedents of stressors at work. Academy of Management Journal, 24 (1), 48–67.

Pellegrini, E. K., & Scandura, T. A. (2008). Paternalistic leadership: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 34 (3), 566–593.

Peterson, S. J., Galvin, B. M., & Lange, D. (2012). CEO servant leadership: Exploring executive characteristics and firm performance. Personnel Psychology, 65 (3), 565–596.

Piccolo, R. F., & Colquitt, J. A. (2006). Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Academy of Management Journal, 49 (2), 327–340.

Piccolo, R. F., Greenbaum, R., Hartog, D. N. D., & Folger, R. (2010). The relationship between ethical leadership and core job characteristics. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31 (2–3), 259–278.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88 (5), 879–903.

Podsakoff, N. P., LePine, J. A., & LePine, M. A. (2007). Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92 (2), 438–454.

Porter, C. M., Woo, S. E., & Campion, M. A. (2016). Internal and external networking differentially predict turnover through job embeddedness and job offers. Personnel Psychology, 69 (3), 635–672.

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15 (3), 209–233.

Purvanova, R. K., Bono, J. E., & Dzieweczynski, J. (2006). Transformational leadership, job characteristics, and organizational citizenship performance. Human Performance, 19 (1), 1–22.

Rodell, J. B., & Judge, T. A. (2009). Can “good” stressors spark “bad” behaviors? The mediating role of emotions in links of challenge and hindrance stressors with citizenship and counterproductive behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94 (6), 1438–1451.

Rotundo, M., & Sackett, P. R. (2002). The relative importance of task, citizenship, and counterproductive performance to global ratings of job performance: A policy-capturing approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87 (1), 66–80.

Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23 , 224–253.

Scandura, T. A., & Schriesheim, C. A. (1994). Leader-member exchange and supervisor career mentoring as complementary constructs in leadership research. Academy of Management Journal, 37 (6), 1588–1602.

Schaubroeck, J. M., Shen, Y., & Chong, S. (2017). A dual-stage moderated mediation model linking authoritarian leadership to follower outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102 (2), 203–214.

Schuh, S. C., Zhang, X. A., & Tian, P. (2013). For the good or the bad? Interactive effects of transformational leadership with moral and authoritarian leadership behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 116 (3), 629–640.

Schutz, A. (1967). The phenomenology of the social world . Northwestern University Press.

Selig, J. P., & Preacher, K. J. (2008, June). Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation: An interactive tool for creating confidence intervals for indirect effects [Computer software]. Available from http://quantpsy.org/ .

Shamir, B., House, R. J., & Arthur, M. B. (1993). The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: A self-concept based theory. Organization Science, 4 (4), 577–594.

Shen, Y., Chou, W. J., & Schaubroeck, J. M. (2019). The roles of relational identification and workgroup cultural values in linking authoritarian leadership to employee performance. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28 (4), 498–509.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7 (4), 422–445.

Skarlicki, D. P., & Latham, G. P. (1996). Increasing citizenship behavior within a labor union: A test of organizational justice theory. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81 (2), 161–169.

Skarlicki, D. P., & Latham, G. P. (1997). Leadership training in organizational justice to increase citizenship behavior within a labor union: A replication. Personnel Psychology, 50 (3), 617–633.

Smircich, L., & Morgan, G. (1982). Leadership: The management of meaning. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 18 (3), 257–273.

Stellmacher, J., & Petzel, T. (2005). Authoritarianism as a group phenomenon. Political Psychology, 26 (2), 245–274.

Takeuchi, R., Wang, A. C., & Farh, J. L. (2020). Asian conceptualizations of leadership: Progresses and challenges. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 7 , 233–256.

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (2), 178–190.

Tepper, B. J. (2007). Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 33 (3), 261–289.

Thau, S., Bennett, R. J., Mitchell, M. S., & Marrs, M. B. (2009). How management style moderates the relationship between abusive supervision and workplace deviance: An uncertainty management theory perspective. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108 (1), 79–92.

Thomas, J., & Griffin, R. (1983). The social information processing model of task design: A review of the literature. Academy of Management Review, 8 (4), 672–682.

Wallace, J. C., Edwards, B. D., Arnold, T., Frazier, M. L., & Finch, D. M. (2009). Work stressors, role-based performance, and the moderating influence of organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94 (1), 254–262.

Wang, H., & Guan, B. (2018). The positive effect of authoritarian leadership on employee performance: The moderating role of power distance. Frontiers in Psychology, 9 , 357.

Wayne, S. J., Lemmon, G., Hoobler, J. M., Cheung, G. W., & Wilson, M. S. (2017). The ripple effect: A spillover model of the detrimental impact of work–family conflict on job success. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38 (6), 876–894.

Webster, J. R., Beehr, T. A., & Christiansen, N. D. (2010). Toward a better understanding of the effects of hindrance and challenge stressors on work behavior. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76 (1), 68–77.

Webster, J. R., Beehr, T. A., & Love, K. (2011). Extending the challenge-hindrance model of occupational stress: The role of appraisal. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79 (2), 505–516.

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17 (3), 601–617.

Williams, L. J., & O’Boyle, E. H., Jr. (2008). Measurement models for linking latent variables and indicators: A review of human resource management research using parcels. Human Resource Management Review, 18 (4), 233–242.

Wu, M., Huang, X., Li, C., & Liu, W. (2012). Perceived interactional justice and trust-in-supervisor as mediators for paternalistic leadership. Management and Organization Review, 8 (1), 97–122.

Xu, E., Huang, X., Lam, C. K., & Miao, Q. (2012). Abusive supervision and work behaviors: The mediating role of LMX. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33 (4), 531–543.

Zhang, Y., & Xie, Y. H. (2017). Authoritarian leadership and extra-role behaviors: A role-perception perspective. Management and Organization Review, 13 (1), 147–166.

Zhang, Y., LePine, J. A., Buckman, B. R., & Wei, F. (2014). It’s not fair… or is it? The role of justice and leadership in explaining work stressor–job performance relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 57 (3), 675–697.

Zheng, Y., Huang, X., Redman, T., Graham, L., & Hu, S. (2020). Deterrence effects: The role of authoritarian leadership in controlling employee workplace deviance. Management and Organization Review, 16 (2), 377–404.

Zheng, Y., Graham, L., Farh, J. L., & Huang, X. (2021). The impact of authoritarian leadership on ethical voice: A moderated mediation model of felt uncertainty and leader benevolence. Journal of Business Ethics, 170 (1), 133–146.

Zheng, Y., Epitropaki, O., Graham, L., & Caveney, N. (2022). Ethical leadership and ethical voice: The mediating mechanisms of value internalization and integrity identity. Journal of Management, 48 (4), 973–1002.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Business, Hong Kong Baptist University, WLB 902, 34 Renfrew Road, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong

School of Business, Hong Kong Baptist University, WLB 725, 34 Renfrew Road, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong

School of Labor and Human Resources, Renmin University of China, Room 232, QiuShi Building, No.59, Zhongguancun Street, Beijing, China

Jian-min Sun

Surrey Business School, University of Surrey, Guildford, GU2 7XH, UK

Yuyan Zheng

Business School, Durham University, Mill Hill Lane, Durham, DH1 3LB, UK

School of Business, Hong Kong Baptist University, 34 Renfrew Road, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jian-min Sun .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval.

Our study involving human participants was approved by the Hong Kong Baptist University Doctorate in Business Administration Dissertation Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate

All participants agreed in writing to participate in our study.

Consent to publication

All participates from Study 1a and Study 2 agreed to have their raw data published without their name attached. Participates from Study 1b agreed to publication of their information in a research report showing the overall data pattern.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest or competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Chen, L., Huang, X., Sun, Jm. et al. The virtue of a controlling leadership style: Authoritarian leadership, work stressors, and leader power distance orientation. Asia Pac J Manag (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-022-09860-7

Download citation

Accepted : 23 October 2022

Published : 19 November 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-022-09860-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Authoritarian leadership

- Challenge/hindrance stressor framework

- Leader power distance orientation

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 23 December 2019

Authoritarian leadership and task performance: the effects of leader-member exchange and dependence on leader

- Zhen Wang 1 ,

- Yuan Liu 1 &

- Songbo Liu 1

Frontiers of Business Research in China volume 13 , Article number: 19 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

58k Accesses

19 Citations

Metrics details

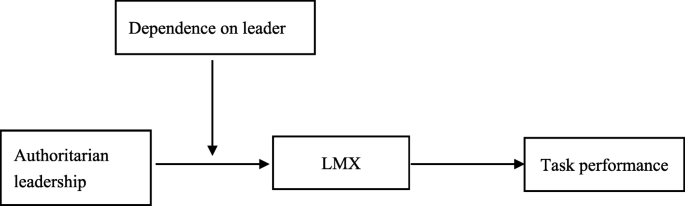

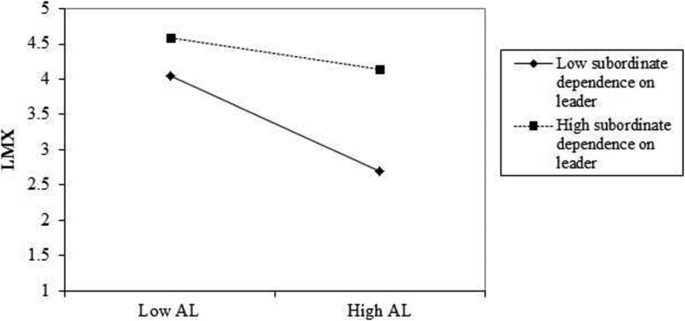

This study examines how and when authoritarian leadership affects subordinates’ task performance. Using social exchange theory and power dependence theory, this study proposes that authoritarian leadership negatively influences task performance through leader-member exchange (LMX). This study further proposes that the effect of authoritarian leadership on LMX is stronger when a subordinate has less dependence on a leader. A two-wave survey was conducted in a large electronics and information enterprise group in China. These hypotheses are supported by results based on 219 supervisor-subordinate dyads. The results reveal that authoritarian leadership negatively affects subordinates’ task performance via LMX. Dependence on leader buffers the negative effect of authoritarian leadership on LMX and mitigates the indirect effect of authoritarian leadership on employee task performance through LMX. Theoretical contributions and practical implications are discussed.

Introduction

The dark or destructive side of leadership behavior has attracted the attention of many scholars and practitioners in recent years (Liao and Liu 2016 ). Much of the research has focused on authoritarian leadership (e.g., Chan et al. 2013 ; Li and Sun 2015 ; Schaubroeck et al. 2017 ), which is prevalent in Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia-Pacific business organizations (Pellegrini and Scandura 2008 ). Authoritarian leadership refers to the leadership that stresses the use of authority to control subordinates (Cheng et al. 2004 ). In general, authoritarian leadership has a negative connotation in the literature; this type of leadership is negatively related to employees’ attitudes, emotions and perceptions, for example, regarding organizational commitment, job satisfaction, tacit knowledge-sharing intentions (Chen et al. 2018 ), team identification (Cheng and Wang 2015 ), intention to stay and organizational justice (Pellegrini and Scandura 2008 ; Schaubroeck et al. 2017 ). A substantial body of empirical research has also explored the influence of authoritarian leadership on followers’ work-related behavior and outcomes. Authoritarian leadership is negatively related to employee voice (Chan 2014 ; Li and Sun 2015 ), organizational citizenship behavior (Chan et al. 2013 ), employee creativity (Guo et al. 2018 ), and employee performance (Chan et al. 2013 ; Schaubroeck et al. 2017 ; Shen et al. 2019 ; Wu et al. 2012 ), and such leadership is positively associated with employee deviant workplace behavior (Jiang et al. 2017 ). In particular, studies concerning authoritarian leadership and employee performance have suggested that authoritarian leadership is negatively related to employee performance because subordinates of authoritarian leaders are likely to have low levels of the following: trust-in-supervisor, organization-based self-esteem, perceived insider status, relational identification, and thus, little motivation to improve performance (Chan et al. 2013 ; Schaubroeck et al. 2017 ; Shen et al. 2019 ; Wu et al. 2012 ).

Although previous studies have explored the effect of authoritarian leadership on employee performance from the perspective of self-evaluation or perception, such as organization-based self-esteem or perceived insider status, the underlying mechanism remains unclear (Chan et al. 2013 ; Schaubroeck et al. 2017 ). To fully understand the effect of authoritarian leadership on employee performance, it is critical to investigate alternative influencing mechanisms of authoritarian leadership from other perspectives (Hiller et al. 2019 ). For example, Wu et al. ( 2012 ) reveal that trust-in-supervisor mediates the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee performance; Shen et al. ( 2019 ) show that relational identification also mediates this relationship. These findings suggest that authoritarian leadership may lead to a poor exchange between leaders and followers, whereby followers of authoritarian leaders may reciprocate by withholding their efforts at work. These studies use a social exchange perspective to understand the effect of authoritarian leadership on employee performance but fail to examine the exchange relationship explicitly. To summarize, little is known about how authoritarian leadership impacts the ongoing social exchange relationship between leaders and subordinates and how such social exchange affects subordinates’ performance. Therefore, we adopt a social exchange perspective to explore the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee task performance to gain a deep understanding of employees’ reaction to authoritarian leadership behavior.

From the perspective of social exchange, leader-member exchange (LMX) is most often chosen to examine how leadership affects followers’ behavior and outcomes (Dulebohn et al. 2012 ). Thus, we specifically posit that LMX mediates the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee task performance.

Moreover, Wang and Guan ( 2018 ) suggest that the effects of authoritarian leadership on employees depend on certain conditions and, thus, may influence the relationship between authoritarian leadership and performance. Literature concerning the relationship between mistreatment and employees’ response find that employees are less likely to respond to perceived mistreatment with deviant behavior when their power status is lower than that of the offender or when they depend more on the perpetrator (Aquino et al. 2001 ; Tepper et al. 2009 ). Since employees have less power than the offender, vengeful or deviant employee behavior may incur a punitive response or trigger future downward hostility (Tepper et al. 2009 ). Thus, the second purpose of this research is to examine how subordinates’ dependence on a leader impacts the responses of subordinates to authoritarian leadership. Specifically, we posit that subordinates’ dependence on a leader moderates the relationship between authoritarian leadership and LMX.

By examining the relationship between authoritarian leadership and subordinates’ task performance, this research makes several contributions to the literature. First, we directly examine the social exchange relationship between authoritarian leaders and their subordinates, which helps further clarify the mediating mechanism of authoritarian leadership on employee task performance (Chan et al. 2013 ; Schaubroeck et al. 2017 ). Second, this study contributes to the LMX literature by exploring the role of LMX in destructive or dark leadership. Indeed, most studies on LMX focus on how constructive leadership leads to a positive and high-quality LMX relationship, which then impacts followers’ behavior and outcomes (Chan and Mak 2012 ; Lin et al. 2018 ; Qian et al. 2017 ; Wang et al. 2005 ). Therefore, exploring and determining how destructive or dark leadership behavior influences the exchange relationship between leaders and followers is imperative (Harvey et al. 2007 ; Xu et al. 2012 ). Third, this study helps clarify the boundary condition of the effect of authoritarian leadership on subordinate outcomes. By investigating and demonstrating the moderating effect of employee dependence on a leader, our research offers some of the first insights into how dependence influences the effect of authoritarian leadership and the social exchange relationship as well.

Theoretical background and hypotheses development

- Authoritarian leadership

Authoritarian leadership refers to leader behavior that exerts absolute authority and control over subordinates and demands unconditional obedience (Farh and Cheng 2000 ; Pellegrini and Scandura 2008 ). Authoritarian leaders expect their subordinates to obey their requests without disagreement and to be socialized to accept and respect a strict and centralized hierarchy (Redding 1990 ).

Authoritarian leadership reflects the cultural characteristics of familial ties, paternalistic control, and submission to authority in Chinese culture (Farh and Cheng 2000 ; Farh et al. 2008 ). Influenced by Confucian doctrine, a father has absolute authority and power over his children and other family members in a traditional Chinese family (Cheng and Wang 2015 ). In business organizations, leaders often enforce this patriarchal value by establishing a vertical hierarchy and by playing a paternal role in an authoritarian leadership style (Peng et al. 2001 ). Authoritarian leadership is prevalent in Chinese organizations and its construct domain remains relatively unchanged regardless of rapid modernization (Farh et al. 2008 ).

According to Farh and Cheng’s ( 2000 ) research, authoritarian leadership has four kinds of typical behavior. First, authoritarian leaders exercise tight control over their subordinates and require unquestioning submission. To maintain their absolute dominance in organizations, authoritarian leaders are unwilling to empower their subordinates. In addition, higher authoritarian leaders share relatively little information with employees and adopt a top-down communication style. Second, authoritarian leaders tend to deliberately ignore subordinates’ suggestions and contributions. Such leaders are more likely to attribute success to themselves and to attribute failure to subordinates. Third, authoritarian leaders focus very much on their dignity and always show confidence. Such leaders control and manipulate information to maintain the advantage of power distance and create and maintain a good image through manipulation. Fourth, highly authoritarian leaders demand that their subordinates achieve the best performance within the organization and make all the important decisions in their team. In addition, such leaders strictly punish employees for poor performance.

Authoritarian leadership and task performance

In this study, we posit that authoritarian leadership harms employee performance according to the four kinds of typical behavior of authoritarian leaders. First, authoritarian leaders try to maintain a strict hierarchy, are unwilling to share information with followers, and adopt a top-down communication style (Farh and Cheng 2000 ). All of these behaviors create distance and distrust between subordinates and leaders, thus leading to poor employee performance (Cheng and Wang 2015 ). Second, authoritarian leaders tend to ignore followers’ contributions to success and to attribute failure to followers (Farh and Cheng 2000 ). These behaviors greatly undermine subordinates’ self-evaluation and are harmful to improving employee performance (Chan et al. 2013 ; Schaubroeck et al. 2017 ). Third, it is typical for leaders with an authoritarian leadership style to control and manipulate information to maintain the advantage of power distance and create and maintain a good image (Farh and Cheng 2000 ). Such behaviors set a bad example for subordinates and are not conducive to improving employee performance (Chen et al. 2018 ). Fourth, leaders with a highly authoritarian leadership style focus strongly on the supreme importance of performance. Subordinates are commanded to pursue high performance and surpass competitors. If subordinates fail to reach the desired goal, leaders will rebuke and punish them severely (Farh and Cheng 2000 ). Leaders’ emphasis on high performance and possible severe consequences enhance subordinates’ sense of fear (Guo et al. 2018 ), which is detrimental to performance improvement. To summarize, we posit that authoritarian leadership is negatively related to employee performance.

Authoritarian leadership and LMX