- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

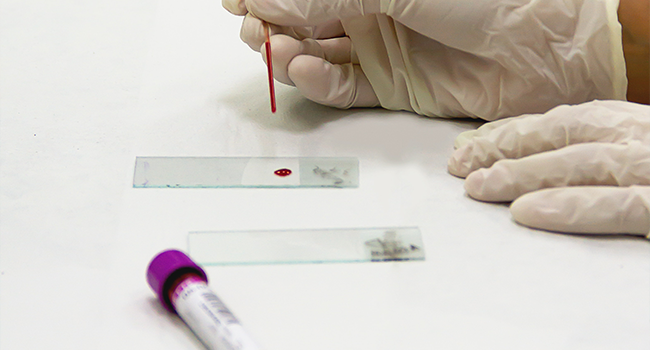

Hemophobia (Fear of Blood) Signs and Coping Strategies

- What Is it?

Hemophobia is a psychological disorder characterized by an extreme fear of blood . While it's normal to feel a bit queasy or uncomfortable at the sight of blood, people with hemophobia react to blood in irrational ways and can become highly distressed at the mere thought of it.

This article explains what hemophobia is and what causes it. It also covers how hemophobia is diagnosed and treated, along with ways to cope with the fear of blood.

Verywell / Danie Drankwalter

What Is Hemophobia?

Hemophobia, or blood phobia, causes an irrational fear of seeing blood. This persistent fear causes those who experience hemophobia to have intense feelings of distress upon seeing blood or even thinking about it.

The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) classifies blood phobia as a specific phobia . A specific phobia is an anxiety disorder that presents as a fear of a certain object or situation. The DSM-5 characterizes the fear of a specific phobia as out of proportion to the actual danger posed by a specific situation or object.

Specific phobias are divided into five categories, and blood phobia falls within the category of blood-injection-injury type. Other examples of phobias within this category are those related to seeing or experiencing an injury, or even something as simple as getting your blood drawn .

Symptoms of Hemophobia

Many people living with a blood phobia may only experience symptoms if they see blood. But for some people, even the thought of blood can make them feel panicked or anxious. This is referred to as anticipatory anxiety.

Each person with hemophobia may react to blood differently, but some of the more common symptoms are:

- Tremors or palpitations

- Chest tightness or pain

- Shortness of breath

- Faintness or dizziness

Those with a fear of blood may be highly distressed and go out of their way to avoid situations that involve blood.

Symptoms in Children

Symptoms of hemophobia can also vary from child to child, but some of the most common include:

- Increased heart rate

- Trembling and shaking

- Feeling like they are choking

- Chest pain or discomfort

- Fear of dying

- Feeling numb

- Chills or hot flashes

Additionally, a child with hemophobia may display extreme, irrational fear when faced with a situation in which blood may be present, such as going to a doctor's appointment.

Such situations may cause the child to cry, throw tantrums, or cling to their parent or caregiver.

Diagnosing Hemophobia

Hemophobia is formally diagnosed using seven criteria outlined in the DSM-5:

- The fear is persistent and is considered unreasonable or excessive. The fear may occur in the presence of blood or in anticipation of seeing blood.

- Seeing blood nearly always results in an anxious response. This may include a panic attack. In children, the response may take the form of clinging, tantrums, crying, or freezing.

- The person with the blood phobia knows that their fear of blood is excessive (though in children this may not be the case).

- The person either avoids blood or experiences intense feelings of anxiety and is distressed in situations that involve blood.

- The fear of blood significantly disrupts the person's daily life and may impact their work, schooling, relationships, or social activities. They may have significant distress about having their phobia of blood.

- The fear of blood typically persists for at least six months.

- The feelings of anxiety or behaviors associated with the blood phobia can't be explained through other disorders like obsessive-compulsive disorder , social phobia , panic disorder , and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) .

Not everyone with a blood phobia is formally diagnosed. Many people with blood phobia are already aware they have a phobia and may choose to live their life without a diagnosis. These people may also go to great lengths to avoid blood or situations that involve blood.

This approach is not advised, as avoidance of blood may make a blood phobia worse.

The cause of specific phobias like hemophobia are often complex and may be due to a variety of reasons like past experiences, learned history, and biological factors.

Past Experiences

Some people may develop a phobia of blood after a past traumatic experience. A car accident, for instance, can equate negative emotions with the sight of blood, and may lead to an irrational fear of blood.

Learned History

A learned history can be one factor that contributes to the development of a blood phobia. There are three forms of learned history:

- A direct learning experience refers to a specific experience that involves blood. This experience might have been traumatic.

- An observational learning experience refers to learning a fear by observing other people show fear in a situation that involves blood. This may involve a child seeing their parent be afraid of blood, then developing their own fear of blood.

- Informational learning refers to a fear that might come from reading or hearing about a situation that could be considered dangerous.

Often, learned history is not the sole reason for developing a phobia. Other factors like genetics and overall mental health can play a role in phobia development.

Biological Factors

There may be a genetic component to developing a specific phobia, as it is believed that some people are born with a predisposition to feelings of anxiety compared to others.

If a person with hemophobia sees blood, they may experience a number of biological changes in the body:

- Release of cortisol , a primary stress hormone

- Release of insulin , a hormone produced in the pancreas that turns glucose to energy

- Release of growth hormones, which help give your body energy as part of its response to stress

- Changes to the activity in the brain

- Increased blood pressure

Many phobias can be treated or potentially cured. Specific phobias like hemophobia can be treated through desensitization or exposure therapy .

This involves a person with a phobia of blood gradually being exposed to blood or situations that involve being around blood. These exposure techniques can be performed with the help of a professional.

Other treatment options include psychotherapy , counseling, and cognitive behavioral therapy .

Typically, medication is not used to treat phobias. In some cases, it may be prescribed to help with anxiety. Medications that may be prescribed in this context include beta-blockers , benzodiazepines, and antidepressants.

Coping With Hemophobia

Having a blood phobia can be distressing, but there are techniques that can help you cope with this fear.

Distraction Techniques

Distraction techniques involve focusing on something else or performing an activity to distract from a situation that may involve blood or the thought of blood.

You may be able to distract yourself by:

- Listening to music

- Playing games

- Arts and crafts, like painting or embroidery

- Walking or going on a bike ride

- Meeting up with a friend

Visualizing a situation that evokes feelings of calm may be beneficial for those with hemophobia. Creating a calm image in the brain and thinking about how it felt to be in that situation can reduce feelings of anxiety.

Challenge Negative Thoughts

Negative thoughts associated with a specific phobia can bring on symptoms of anxiety. By challenging these negative thoughts, those with hemophobia may better cope with their fears.

For instance, if you have hemophobia and think you can't cope with having your blood drawn, you may challenge this thought by reminding yourself that a blood test is a normal procedure that many other people experience regularly without issue.

Relaxation Techniques

When a person with hemophobia thinks about blood or is in a situation involving blood, they may notice their body tenses up and their heart rate increases.

Using relaxation techniques like muscle relaxation, meditation, and deep breathing may help reduce feelings of anxiety.

The exact cause of hemophobia may be hard to pinpoint, but there are steps a person can take to reduce their fear of blood. Gradual exposure to blood or situations that involve blood may help a person desensitize their irrational fear.

Those with a blood phobia can also benefit from mindfulness exercises that may improve mental health overall, such as exercising regularly, eating a healthy diet, staying hydrated, and attending therapy.

American Psychological Association. Blood phobia.

American Psychological Association. Specific phobia.

SAMHSA. Anxiety disorders .

Perelman School of Medicine. Specific phobias.

Cincinnati Children's. What are phobias? .

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Impact of the DSM-IV to DSM-5 changes on the national survey on drug use and health .

Barlett A, Singh R, Hunter R. Anxiety and epigenetics . Adv Exp Med Biol . 2017;978(1):145-166. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-53889-1_8

National Institute of Mental Health. Mental health medications .

Harvard Health Publishing. Relaxation techniques: Breath control helps quell errant stress response .

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Understanding and Overcoming the Fear of Blood

Daniel B. Block, MD, is an award-winning, board-certified psychiatrist who operates a private practice in Pennsylvania.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/block-8924ca72ff94426d940e8f7e639e3942.jpg)

JGI /Tom Grill / Getty Images

Hemophobia (also called hematophobia) is the fear of blood, wounds, and injuries. Hemophobia is categorized by the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual as a “blood-injection-injury” (BII) phobia. This subtype, which also includes trypanophobia or fear of needles can cause symptoms that are not frequently seen in other types of specific phobias .

Having an aversion to blood is natural—in fact, horror movies often prey on our discomfort by showing large quantities of fake blood to inspire fear and unease in their audience. However, hemophobia causes much more than discomfort, and someone with this condition will experience highly distressing and disruptive symptoms at the sight of blood.

This article explores the symptoms, diagnosis, and causes of hemophobia. It also covers the treatments and coping strategies that can be helpful.

Symptoms of Hemophobia

Hemophobia can cause physical symptoms like:

- Increased heart rate initially, followed by a sudden drop in heart rate and blood pressure

- Nausea and gastrointestinal upset

- Rapid breathing

It can also cause emotional symptoms, including:

- Anticipatory anxiety ahead of medical procedures

- Extreme fear and anxiety at the sight or thought of blood

- Feeling of intense disgust at the sight of blood

- Panic attacks

- Persistent avoidance of medical procedures that might involve the sight of blood

- Problems functioning in other areas of your life

Children can also show signs of hemophobia by clinging, crying, freezing, and throwing tantrums as a response to their fear of blood.

While most types of phobia lead to an increase in cardiac activity, BII phobias such as hemophobia can cause an abrupt and sometimes dangerous reduction in blood pressure and heart rate. This sudden drop can lead to fainting at the sight of blood, which is relatively common for people with hemophobia.

Rarely, an extreme reaction to the sight of blood could lead to cardiac arrest and even death. If you or a loved one is experiencing serious cardiac symptoms after the sight of blood, call 911 or seek help immediately.

For help dealing with hemophobia, contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 1-800-662-4357 .

Diagnosis of Hemophobia

When diagnosing a phobia , your doctor will look for signs that show your fear of blood is extreme, has lasted for at least six months, and causes significant problems in other areas of your life.

Your doctor will also check to see if you have symptoms of a related phobia, like the fear of hospitals ( nosocomephobia ) or needles ( trypanophobia ), or if you show signs of a common comorbid condition, like:

- Agoraphobia

- Animal-based phobia

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Panic disorder

- Social anxiety disorder (SAD)

To diagnose hemophobia, your healthcare provider will ask question about your symptoms, their severity, and how long they have lasted. They will also ask questions about how these symptoms affect your life and may evaluate you to determine if your symptoms might be caused by another mental health condition.

Causes of Hemophobia

Hemophobia affects around 3% to 4% of people. While it's hard to determine an exact cause, BII phobias may have a genetic component. Many people with this type of fear have multiple family members with the same condition. It's also possible to have developed this phobia during childhood if a caregiver or another adult showed extreme discomfort around blood.

Hemophobia can also be related to trauma. If you have experienced or witnessed a severe injury involving significant blood loss, you may develop a phobia.

Your phobia may also be rooted in another underlying fear, like:

- Dentophobia , or fear of dentists

- Iatrophobia , or fear of doctors

- Illness anxiety disorder , or fear of severe health conditions

- Mysophobia , or fear of germs

- Nosophobia , or fear of a specific disease

In some cases, the fear of blood may be related to a fear of loss of control or even a fear of death .

Types of Hemophobia

Hemophobia symptoms can occur in a variety of situations; you don't necessarily need to be in sight of blood to experience discomfort and anxiety. While phobias may begin as a fear of a specific stimulus, they can become generalized over time.

That means you may experience symptoms by encountering fake blood in images, movies, television shows, or video games.

Impact of Hemophobia

Hemophobia can cause a wide range of difficulties that may prove life-limiting or even dangerous. If you are afraid of blood, you may be reluctant to seek medical treatment. You might postpone or avoid annual physicals and needed medical tests. You may refuse surgery or dental treatments.

Parents with hemophobia may find it difficult or impossible to bandage their children’s wounds. You might pass these tasks off to your spouse whenever possible. You may also overreact to minor injuries in your children as well as yourself, frequenting emergency rooms or walk-in clinics when home treatment would suffice.

A fear of blood may also cause you to limit activities that carry a risk of injury. You might be unable to participate in outdoor activities such as hiking, camping, or running. You may avoid sports, carnival rides, and other activities that you perceive as dangerous.

Over time, such avoidant behaviors can lead to isolation. You might develop a social phobia or, in extreme cases, agoraphobia . Your relationships might suffer, and you might find it difficult to participate in even the normal activities of daily living. Feeling depressed is not unusual.

A fear of blood can have a limiting impact on your life. You might avoid any situation that could lead to injury or exposure to the sight of blood. As a result, normal daily activities may be severely impaired, which can affect relationships and contribute to loneliness and social isolation.

Treatment for Hemophobia

Hemophobia responds very well to many treatment methods. Therapy is generally the first-line treatment option, and medication may also prove helpful.

If your phobia is severe, medications like antidepressants or anti-anxiety drugs may help. These may be prescribed to control the anxiety and allow you to focus on your treatment, or they may be useful in situations where you have to undergo a medical procedure or otherwise face your fear of blood.

Psychotherapy

One of the most common psychotherapy options for phobias is cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) . In CBT, you learn to replace your fearful self-talk with healthier responses to the sight of blood. You also learn new behaviors and coping strategies.

Your therapist may also try exposure therapy , where you are gradually exposed to things that trigger your fear. In exposure therapy, your therapist provides you with guidance and a safe environment to help you learn how to calm yourself down at the sight of blood.

Other forms of talk therapy, hypnosis , and even alternative treatments may also be helpful.

A skilled therapist can guide you through the process of recovery, which can be difficult or impossible on your own. With help, though, there is no reason for hemophobia to control your life.

Coping With Hemophobia

You can learn to manage your hemophobia , and seeking professional treatment is an important part of that process.

Taking other steps can also help, like:

- Learning more about your condition and understanding what triggers your fear

- Incorporating stress-management techniques into your daily routine

- Leaning on friends and family for support

If you experience fainting at the sight of blood, familiarizing yourself with the symptoms that typically precede a fainting spell may help you reduce your chance of injury. If you feel faint, try to:

- Get to a safe area to prevent a fall

- Practice breathing exercises to combat any hyperventilation

- Tense the muscles in your arms, legs, and core to try to prevent yourself from fainting

In addition to seeking professional treatment, there are self-help strategies that can help you cope with a fear of blood. Understanding the condition and practicing relaxation strategies can be helpful. Knowing how to respond when you find yourself feeling faint upon the sight of blood may help you avoid injury due to a fall.

While it is natural to feel uncomfortable at the sight of blood, if your fear is keeping you from undergoing regular medical check-ups and necessary procedures, it may be time to consult with a mental healthcare professional who understands how to treat phobias. Treatment can alleviate the anxiety associated with hemophobia and help you recover from your symptoms.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed . Washington, DC; 2013. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Wani AL, Ara A, Bhat SA. Blood injury and injection phobia: The neglected one . Behav Neurol . 2014;2014:471340. doi:10.1155/2014/471340

Samra CK, Abdijadid S. Specific phobia . In: StatPearls . StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

Pan Y, Cai W, Cheng Q, Dong W, An T, Yan J. Association between anxiety and hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies . Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat . 2015;11:1121-30. doi:10.2147/NDT.S77710

Wani A, Bhat S, Ara A. Persistence and inheritance of blood injury and injection phobia . Gulhane Med J . 2016;58:67-73. doi:10.5455/gulhane.172838

Singh J, Singh J. Treatment options for the specific phobias . Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol . 2016;5(3):593-598. doi:10.18203/2319-2003.ijbcp20161496

Pitkin MR, Malouff JM. Self-arranged exposure for overcoming blood-injection-injury phobia: a case study . Health Psychol Behav Med . 2014;2(1):665-669.

Spiegel SB. Current issues in the treatment of specific phobia: recommendations for innovative applications of hypnosis . Am J Clin Hypn . 2014;56(4):389-404. doi:10.1080/00029157.2013.801009

Ritz T, Meuret AE, Ayala ES. The psychophysiology of blood-injection-injury phobia: Looking beyond the diphasic response paradigm . Int J Psychophysiol . 2010;78(1):50-67. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2010.05.007

By Lisa Fritscher Lisa Fritscher is a freelance writer and editor with a deep interest in phobias and other mental health topics.

An Overview of Hemophobia: Symptoms, Risk Factors, and Treatment

- Updated: 12.09.2022

Rabia Khaliq

Dr. william grigg.

Phobia is a disorder characterized by an extreme, persistent, and irrational fear of specific objects or situations. People with any phobia feel vulnerable and will go to any length to avoid the source of their anxiety. The main categories include complex phobias ( agoraphobia and social phobia ) and specific phobias . Hemophobia — a fear of blood — is in the latter category.

The sight or thoughts of blood cause distress or anxiety in people with hemophobia. Moreover, the condition interferes with a patient’s life. For instance, one may skip a doctor’s appointment so as not to take a blood test.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) categorizes hemophobia as blood-injection-injury (BBI) phobia. According to the National Institute of Health [1*] , the disorder is prevalent since it affects about 3% to 4% of the general population.

Fear of blood can be managed. Book an appointment to see a doctor and get medical phobia treatment .

Main Causes and Risk Factors for Blood Phobia

The exact cause of hemophobia is not clear. However, it has been established that anxiety disorders such as hemophobia can pass through bloodlines. A person with a neurotic personality usually overreacts to distress and is likely to develop phobias too.

In some cases, the disorder is a result of direct traumatic experiences or hearing a narration of a frightening experience. It is also possible to acquire the condition by witnessing a blood-associated trauma.

Aside from genetics and traumatic experiences, a few more factors make a person more susceptible to hemophobia. These risk factors include:

- Other psychoneurotic disorders. A person with other psychoneurotic disorders like panic disorder may also develop hemophobia.

- Caregiver’s anxiety. If a caregiver usually gets anxious at the sight of blood, the minor in his/her care may develop similar fears. Eventually, the fear may evolve into a phobia.

- Gender. Research indicates that women are more likely to have specific phobias than men. For instance, statistics [2*] show that the occurrence of blood-injury phobia is approximately 2.2% among males and 3.9% among females.

A mental health professional can help you identify the root cause of your anxiety and recommend useful techniques.

Hemophobia Symptoms

Hemophobia symptoms [3*] are evident if the affected person sees blood. The reactions may be emotional or physical.

Emotional Symptoms:

- Feeling unreal and detached from self

- Extreme anxiety

- Panic attacks

- Feeling as if one could die or pass out

- A powerless and helpless feeling

- An unsettling feeling in the stomach

- Desire to escape or disappear from a scene that has blood

Physical Signs:

- An increase in heart rate

- Chest tightness or pain

- Cold or hot flashes

- Difficulty breathing

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Excessive sweating

- Nausea or vomiting

- Trembling or shaking

Although the symptoms of hemophobia may be obvious, only a doctor can make a diagnosis and determine the right treatment.

How to Diagnose Hemophobia

Hemophobia diagnosis involves a psychological evaluation by a mental health practitioner. To make a formal diagnosis, the doctor uses the criteria outlined in the DSM-5.

The seven-point criteria include the following:

- An excessive, persistent, irrational fear of seeing blood.

- The fear of blood persists for at least six months from the first experience.

- Anxiety or panic attacks as a response to the sight of blood.

- The extreme fear of blood is out of proportion to the actual danger it poses.

- Someone actively tries to avoid the sight of blood and has intense distress or anxiety when in a situation with blood.

- The fear of blood interferes with the daily functions of a person.

- The patient’s irrational reactions to blood differ from other specific disorders’ symptoms. The symptoms differ from panic disorder, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or post-traumatic stress disorder signs.

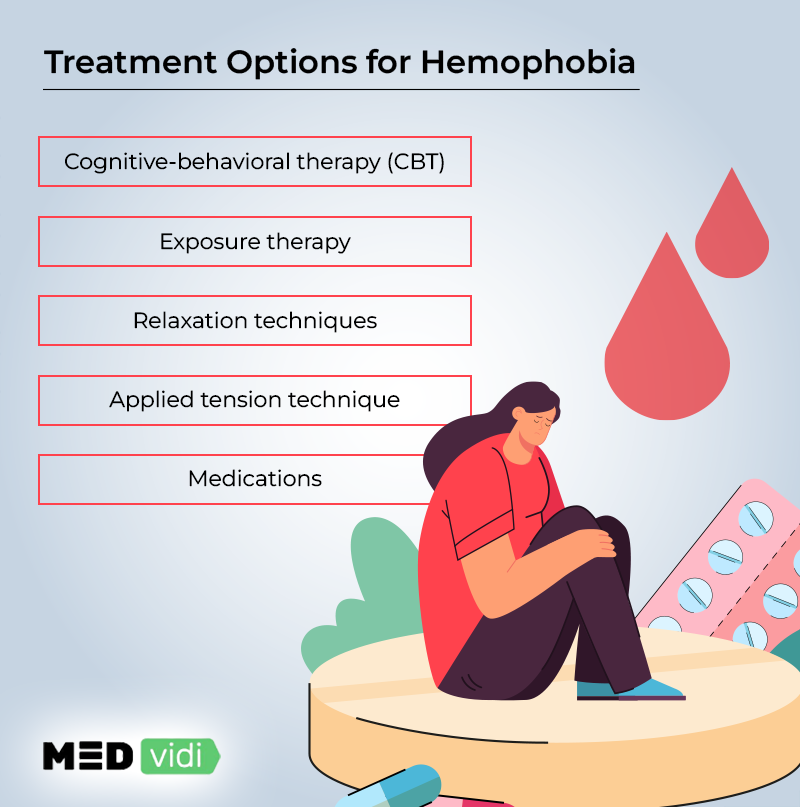

Treatment and Management of Hemophobia

Psychotherapy is the most effective treatment for hemophobia. In severe cases, a doctor may include a pharmacological treatment. Therapeutic interventions to treat hemophobia include:

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

This therapy [4*] helps a patient understand and confront the irrational fear of blood. It also helps them learn new coping techniques to manage their fears.

- Exposure therapy

The patient is gradually and systematically exposed to experiences that involve blood until he/she develops a coping mechanism to overcome the fear of blood.

- Relaxation techniques

The client learns relaxation techniques like yoga, meditation, and breathing exercises. They use these techniques to release physical tension, diffuse stress and eventually get over the fear of blood.

- Applied tension

The Applied Tension technique [5*] is helpful to patients that faint at the sight of blood. In the technique, a person tenses his/her muscles for timed intervals. The exercise happens concurrently with the exposure to the trigger. The tension helps the patient to watch a scene with blood without fainting.

- Medications

When it comes to medications prescribed for hemophobia, the doctor may prescribe selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) , a well-known class of antidepressants.

Hemophobia is a distressful disorder that can interfere with a person’s life. For instance, a patient may not keep medical appointments or be able to help someone in an emergency. People with hemophobia symptoms should seek treatment to be able to have a productive life. If you notice any warning symptoms and want to manage them, MEDvidi doctors are here to help.

- Blood Injury and Injection Phobia: The Neglected One. (2014) Source link

- Blood-injury phobia. (1994) Source link

- The psychophysiology of blood-injection-injury phobia: Looking beyond the diphasic response paradigm. (2010) Source link

- A comprehensive group-based cognitive behavioural treatment for blood-injection-injury phobia. (2022) Source link

- Applied tension. A specific behavioral method for treatment of blood phobia. (1987) Source link

Consult a healthcare professional online and receive a treatment plan tailored to your needs.

Recommended Articles

Recent Articles

Sign up to receive mental health news and tips delivered right in your inbox every month.

- Consent to Telehealth

- DEA rules update

STAY TUNED WITH THOSE WHO FEEL THE SAME WAY YOU DO

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Terms and Conditions

- Payment Terms

- Refund Policy

- HIPAA Notice

- HIPAA Privacy Policy

Evidence Based

This article is based on scientific evidence, written by experts and fact checked by experts.

Our team of experts strive to be objective, unbiased, honest and to present both sides of the argument.

This article contains scientific references. The numbers in the parentheses (1, 2, 3) are clickable links to peer-reviewed scientific papers.

- Pakistan Insights

- Entertainment

- Fashion Files

- Food Fusion

- Travel Journal

- Lifestyle Lounge

- Cyberbullying

Fear Of Blood: Everything You Need To Know About Hemophobia

Are you someone who feels uneasy or anxious at the mere sight of blood? You’re not alone! Hemophobia, while it might sound like a mouthful, is simply the fear of blood. Picture this: a remarkable and capable individual, just like you, who, when faced with blood, experiences an overwhelming sensation of discomfort.

But fear not! Understanding hemophobia and its quirks is the first step toward managing this common yet intriguing phobia. So, let’s delve into the fascinating world of hemophobia, unravel its mysteries, and discover ways to navigate it confidently and easily.

Fear of Blood (Hemophobia/Blood Phobia)

Hemophobia is a specific phobia characterized by an intense and irrational fear of blood. People with hemophobia may experience severe anxiety or panic attacks when confronted with blood, whether it’s their own, someone else’s, or even just the sight of blood in general. This fear can be quite distressing and may interfere with daily life, causing avoidance of situations involving blood or medical procedures.

Why Some People Fear Blood?

The fear of blood, known as hemophobia, can stem from various factors. For some, it might be an instinctual response to the fear of injury or illness. Others may develop it due to a negative or traumatic experience involving blood, such as witnessing a serious accident or undergoing a distressing medical procedure.

Sometimes, cultural or societal influences can also play a role. The sight of blood might be associated with danger or vulnerability, triggering a fear response. Our brains are complex, and fears can develop for many reasons, often without a clear cause. Understanding the origins of this fear can be an essential step in overcoming it and finding ways to cope.

How is Fear of Blood Diagnosed

Diagnosis for the fear of blood, or hemophobia, typically involves a comprehensive assessment by a mental health professional. The process may include:

- Clinical Interview: A therapist or psychologist will conduct a detailed interview to understand the individual’s symptoms, fears, and the impact of the fear of blood on their life.

- Diagnostic Criteria: The mental health professional will use the criteria outlined in diagnostic manuals (such as the DSM-5 – Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) to determine if the fear meets the criteria for specific phobias, like hemophobia.

- Assessment Tools: Psychological assessments or questionnaires might be used to evaluate the severity of the fear and its effects on daily functioning.

- Medical Evaluation: Sometimes, a medical evaluation might be recommended to rule out any underlying medical conditions that could contribute to the fear response, although hemophobia is primarily a psychological issue.

Exploration of Triggers: Understanding the specific situations, thoughts, or images related to blood that trigger fear and anxiety is crucial in diagnosing hemophobia.

Blood Phobia Symptoms

Some of the symptoms of fear of blood are as follows

These symptoms can vary in intensity from person to person and may occur immediately upon exposure to blood or even at the mere anticipation of encountering it.

Overcoming Fear of Blood (Blood Phobia)

Treating blood phobia, or hemophobia, typically involves therapeutic approaches aimed at reducing anxiety and gradually desensitizing individuals to the fear of blood.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) : Therapy isn’t just about lying on a couch and talking about your childhood (though that can be part of it, too!). It’s about learning how to rewire those brain circuits to react differently to the sight of blood. This therapy helps identify and challenge irrational thoughts or beliefs about blood. Techniques like gradual exposure to blood-related stimuli in a controlled and supportive environment can help reduce anxiety.

- Exposure Therapy: Exposure therapy might sound intimidating, but it’s like dipping your toes in the water before you take the plunge – slowly getting used to the sight of blood in a safe and controlled way. Gradual exposure to blood-related situations or images, starting with less anxiety-provoking scenarios and progressing to more challenging ones, can help desensitize individuals to their fear.

- Relaxation Techniques: Learning relaxation and breathing exercises can assist in managing anxiety responses when confronted with blood or blood-related situations.

- Mindfulness and Meditation : Practices focusing on staying present in the moment can aid in reducing overall anxiety levels and managing the fear response to blood.

- Medication: In severe cases where the phobia significantly impacts daily life, a doctor might prescribe anti-anxiety medications or beta-blockers to manage symptoms during exposure therapy or specific situations.

- Support Groups or Counseling: Joining support groups or seeking counseling can provide a supportive environment to discuss fears and gain insights from others facing similar challenges.

The most effective treatment often involves a combination of therapies tailored to an individual’s specific needs and the severity of their hemophobia. Seeking help from mental health professionals or therapists experienced in treating phobias can guide individuals toward overcoming their fear of blood.

Prevalence Rate

Now, here’s a mind-blowing fact: hemophobia isn’t as rare as you might think. Surveys suggest that it’s among the top fears people have, right up there with heights and spiders. So, if you’ve ever felt queasy at the sight of blood, you’re not alone in this wild phobia club.

Interesting Fact

Did you know that some people overcome their fear by actually training to work with blood? Yep, phlebotomists – individuals who skillfully draw blood were once fearful too.

Trypanophobia and Hemophobia

The fear of needles is known as trypanophobia . It often ties into a broader fear of medical procedures or injections rather than solely the sight of blood. This fear can stem from various sources, including

Past Trauma: A negative or painful experience during a medical procedure involving needles can lead to a fear of needles. Traumatic events can leave a lasting impact, causing significant anxiety when faced with similar situations.

Fear of Pain: Some individuals fear the physical sensation associated with needle pricks, even if it’s minimal. The anticipation of pain can trigger anxiety or panic responses.

- Sensitivity to Bodily Intrusions: The idea of a foreign object entering the body, even for a beneficial or necessary reason like drawing blood, can cause discomfort or fear in some individuals.

- Anxiety about Health Procedures: For some, medical settings can induce anxiety or fear due to the environment, leading to a broader fear of medical procedures or needles specifically.

- Lack of Control: Feeling a lack of control over the situation, especially when someone else is administering the needle, can intensify the fear of certain individuals.

Though it’s normal to be uneasy around blood. If this fear is hindering your ability to get routine medical check-ups or necessary treatments. Seeking help from a mental health professional trained in treating phobias could be beneficial. Effective treatment for hemophobia can ease the anxiety linked to this fear and support your recovery from its symptoms.

Next time you catch yourself feeling woozy at the sight of blood, remember, that you’re not alone, and there are a whole bunch of fascinating ways to tackle that fear!

ALSO READ: FEAR OF DARKNESS: EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT NYCTOPHOBIA

- blood and needle phobia

- blood injury

- blood injury phobia

- blood phobia

- blood phobia fear

- blood phobia symptoms

- blood test fear of needles

- blood test needle phobia

- fear of blood

- fear of blood draw

- fear of getting blood drawn

- trypanophobia

- trypanophobia test

Top 10 SEO Strategies to Rank Your Website on Google

Fear of water: everything you need to know about hydrophobia, fear of decision making: everything you need to know about decidophobia.

Very good information

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Most Popular

Top 10 bakeries in islamabad for eid cakes 2024, top 10 bakeries in karachi for eid cakes 2024, easy mehndi designs for eid 2024 : confidence for a stress-free eid, recent comments, editor picks, popular posts, top 10 affordable iftar deals in karachi :feast on a budget, popular category.

- Psychology 78

- Education 57

- Food Fusion 37

- Lifestyle Lounge 37

- Pakistan Insights 37

- News Buzzers 28

- Tech Talk 22

Bepsych.com is your news, entertainment, food, fashion, Tech website. Stay informed with our timely delivery of the latest news directly from the respective industries.

© 2024, Bepsych.com. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

8 Phobias of Blood, Needles, Doctors, and Dentists

- Published: August 2006

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Chapter 8 focuses on phobias of blood, needles, doctors, and dentists, and explores the association of these phobias with fainting, the prevalence of medical phobias, treatment strategies, and ways that the treatment plan can be tailored to treat this type of phobia.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Child Health

- Heart Health

- Men's Health

- Mental Health

- Sexual Health

- Skin Conditions

- Travel Vaccinations

- Treatment and Medication

- Women's Health

- View all categories

- Bones and Joints

- Digestive Health

- Healthy Living

- Signs and Symptoms

Try our Symptom Checker Got any other symptoms?

- Nervous System

- Heart Disease

- Inflammation

- Painkillers

- Muscle Pain

- View all Medicines and Drugs

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Bacterial Vaginosis

- View all Treatments

- BMI Calculator

- Pregnancy Due Date Calculator

- Screening Tests

- Blood Tests

- Liver Function Tests

- Am I Pregnant?

- Am I Depressed?

- View all Tools

- Latest Features

- Health Videos

- Bronchiolitis

- Molluscum Contagiosum

- Actinic Keratosis

- Abdominal Pain in Children

- Subdural Haematoma

- Obesity in Adults

- View all Pro Articles

- View all Medical Calculators

- Login / Register

- Patient Access

- Health Info

How to get over a fear of blood tests

Remove from Saved

Blood tests are a great diagnostic tool, giving vital information to doctors about the state of a patient's health. But for many of us, the idea of having blood drawn from our arm can put us into a panic. If you're feeling nervous about an impending test, try our tips for managing the procedure.

If you're someone who generally takes life in your stride, you might feel a little embarrassed to admit that you're anxious about a blood test . But many people feel nervous when they have blood taken. "It's natural to feel a little anxious about a medical procedure of any kind," agrees Dr Kate Mason of Roots Psychology Group . "Being open and honest about that - with others and yourself - can help you to feel better."

How to prepare for a blood test

A blood test is one of the most common medical tests and is a good way to get a picture of your ...

What is a full blood count - and what can it tell us?

What to expect when you give blood

Eat breakfast (if allowed)

If your blood test doesn't involve fasting (check with your healthcare professional) then it can be helpful to have a healthy breakfast/meal before your appointment (depending on the time of day). "When we’re anxious, it can affect our appetite," says Mason. "But having something to eat can stabilise blood sugar and help us to feel stronger."

Having something to eat immediately after the test (especially if you've been fasting) can also be helpful.

Want to speak to a pharmacist?

Book a private telephone consultation with a local pharmacist today

Locate your fear

Although many of us are worried about blood tests, we're not all anxious for the same reasons. For some, it's a worry about whether the procedure will hurt. For others, it might be a fear of fainting, or nerves that rise up during the wait beforehand. Other people might be nervous about the reason for the test and what their result may mean.

In order to manage your anxiety, it's important to identify where your fear stems from - once you've highlighted what's driving this, you can manage your reaction more effectively. For example, if you're concerned about pain, you may wish to ask for a product to numb the area beforehand.

Manage the wait

If you're feeling nervous about a procedure, managing the wait is very important. "You find with many people that their anxiety is worse before a test rather than when it's actually taking place," agrees Mason. "If you're likely to have to wait, think about how to manage that time. Take a book, or find an interesting article to read on your phone to take your mind off the test itself."

If you're particularly worried, it's also worth asking someone to come with you. They will be able to offer support and distraction as you wait for your name to be called. "Having someone at your side can really help you to feel supported," agrees Mason. "Explain to your friend beforehand how you are feeling and what support you might find helpful."

Manage your physical reaction

If you're concerned about fainting , you can take steps to minimise the risk of this. "Some people are worried that they'll panic so much that they’ll pass out," says Mason. "But panicking tends to raise our blood pressure, and it's low blood pressure that would cause us to faint. Understanding this physiology can be helpful."

It's also helpful to mention at your appointment if you're worried about or prone to fainting or feeling wobbly. "The nurse or phlebotomist will be able to take blood with you lying in a more reclined position if you're worried about dizziness or passing out," Mason advises. "It's worth raising the issue with them - they will be used to patients feeling this way."

Speak to the clinician

Phlebotomists and nurses will have seen it all - and witnessed many different reactions to blood tests. Don't be afraid to mention your misgivings - they will be able to put your mind at rest. "If you let the nurse or phlebotomist know how you're feeling, they'll be able to take that into account and offer reassurance or support," says Mason.

It's also worth thinking how you're going to manage the moment when blood is taken. "Some people find counting is helpful - after all, a blood test doesn't tend to take very long," says Mason. "Or you may wish to look in the other direction and scroll on your phone. Distraction can be a useful way of coping with anxiety and nervousness."

Tips from a nurse

Nurse and Midwife Laura Mudie has her own advice for those nervous about an impending blood test.

"Being nervous about a blood test is very common - both in children and adults. In some people this can become a real phobia," she says. "If you feel this way, it's important to speak to the practitioner taking your blood as they will be able to help."

"Tell the nurse or phlebotomist how you're feeling - they will be able to take a little more time to make sure you're OK. They may be able to use a smaller needle, and make an effort to distract you during the test."

If you have a severe phobia, or the blood test is for a younger person, there are also products available that can numb the site. If you feel that this may help you, it's worth talking with your GP when they refer you for the test, or asking a pharmacist beforehand.

Why some people bruise so easily

Are you protected against flu?

See if you are eligible for a free NHS flu jab today.

Join our weekly wellness digest

from the best health experts in the business

Related Information

- What is a CA125 blood test?

- Blood Groups and Types

- Blood Tests to Detect Inflammation

- Coombs Test

- Full Blood Count and Blood Film

Hello, I have a question can i take THC cannabis when i inject blood thinners? I have a knee injury and I'm using blood thinner but I also usually use THC for my head pain reduction because pills... Volavka

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online with our free symptom checker.

Disclaimer: This article is for information only and should not be used for the diagnosis or treatment of medical conditions. Egton Medical Information Systems Limited has used all reasonable care in compiling the information but make no warranty as to its accuracy. Consult a doctor or other health care professional for diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions. For details see our conditions .

Does the Sight of Blood Make You Anxious? It Could Be Hemophobia.

It’s a common scene: A phlebotomist guides her patient into the room, asks him to sit. She cleans his skin with rubbing alcohol, loops a tourniquet around his forearm. She puts the needle in position and warns him that he may feel a slight pinch. The clear vial attached to the needle fills with a bright pool of red. Minutes later, the procedure is over, and the patient is free to go.

It seems simple enough, but for many people, appointments like these are impossible to complete. If you’re always postponing your regular doctor check-ups in a cold sweat, you may be facing the anxiety condition hemophobia.

Hemophobia is the fear of blood , and it can be extremely inhibiting for those who live with it. People who have hemophobia may avoid necessary medical care or stay away from activities or sports that involve the risk of being injured (and bleeding). Just thinking about surgery or seeing one acted out on a TV show can be enough to make your heart race if you live with the condition.

If any of this sounds like you, you’re not alone. Researchers estimate that hemophobia affects approximately 3-4% of the population , but with the right treatment, you can get past your anxiety. Read on to learn more about hemophobia and what you can do if you’re struggling.

What Is Hemophobia?

Hemophobia is an intense fear of blood. It’s listed as blood injection injury phobia in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorders (DSM-5), though it differs from injection phobia and injury phobia in a number of key ways.

“[Hemophobia] can come on as a result of seeing one’s own blood or the blood of another,” Sheva Rajaee , LMFT, director of the Center for Anxiety and OCD, told the Mighty. While many people experience unease at the sight of blood, your discomfort may rise to the level of a phobia when your “anxiety response to the sight, mention or thought of blood causes an exaggerated or prolonged fear response.”

Hemophobia can manifest in a number of ways, according to Rajaee. Some common experiences of people who live with the condition are:

- Avoidance of blood, including the sight or mention of blood

- Avoidance of situations or activities that could result in bleeding or injury

- Experiencing sweaty palms, dizziness, nausea or racing thoughts at the sight of blood

Dr. Tabasom Vahidi, Ph.D. , told The Mighty that unlike other phobias , people living with hemophobia can experience a vasovagal response, or “fainting induced by a decrease in blood pressure.” John Sanford, who used to struggle with hemophobia, once described the vasovagal response in a piece for Stanford Medicine :

Observing blood seep from a wound, flow into a syringe or spatter on the ground, blood phobics initially will respond like other phobics — that is, their heart rate and blood pressure will increase. But then something else will happen: Their heart rate and blood pressure will suddenly drop, causing dizziness, sweatiness, tunnel vision, nausea, fainting or some combination of these symptoms. This is a vasovagal response … which does not generally occur with other phobias.

It’s worth noting that the vasovagal response is usually harmless, though it is possible to be injured from falling when the response is activated.

What Causes Hemophobia?

Researchers have yet to determine what exactly causes hemophobia. While Rajaee said that phobias can manifest in response to something that happened in your environment, she noted that “unlike other psychological conditions, many phobias and anxiety-related disorders do not have a basis in trauma and do not need to have a rational or familial basis in order to manifest.”

Some studies have suggested that individuals can be genetically predisposed to develop the condition. Researchers have also put forward the idea that hemophobia developed as an evolutionary response to being injured. According to this theory, ancient humans injured by predators may have escaped a grisly fate by catching sight of their own blood and fainting. Predator species tend to pass over prey that abruptly stops moving.