- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

Grade 11 - Apartheid South Africa 1940s to 1960s

The global pervasiveness of racism and segregation in the 1920s and 1930s

During the 1920s and 1930s, there were discriminatory policies in different parts of the world. These were mostly in European countries like Britain and European colonies like South Africa. These discriminatory policies were mostly on basis of Race, and were often in favour of white people’s interests. Black and white people were not allowed contact in different social domains. For instance in schools, white people had well-resourced schools with better facilities, while Black people had inadequate facilities like overcrowded schools with poor teaching and learning resources.

Segregation after formation of the Union

By 1910, South Africa (then Union of South Africa ) was ruled by White people (descendants of white European settlers). This government was exclusively for white people. They were the only ones who participated in it, the only ones allowed to vote.

Under their leadership segregation laws were predominant and highly active. These segregation laws were implemented in spaces such as the work place. In the job market white people were given first priority, they were given upper position and paid higher salaries even if they had the same qualifications, experience and capabilities as Black people. Black people worked under poor and unsafe conditions and were denied the rights to join or form trade unions. In the army only white people could serve main roles like being a soldier, Black people were given supporting roles such as cooking and cleaning. Other segregation laws and policies included the Native Land Act of 1913 and the Pass laws .

National Party victory 1948

The National Party ’s victory in the 1948 elections can be linked with the dismantlement of segregation in South Africa during the Second World War . This was because of the growth in industries, where black people were in demand for labour in industries. Black people filled the positions that were left empty by the whites. White people could not fill these positions because they were few in numbers and most white people already occupied better jobs rather than physical manual labour. Large numbers of black people then moved to the cities to fill these vacancies and soon Blacks became the majority of labour in cities.

Black people were then given pieces of land outside cities to occupy. These pieces of lands were known as ghettos. The ghettos were often not too far from the cities, so Black people could get to work in the cities easy.

In the same year, 1948, when the National Party came to power, apartheid started. Apartheid resulted from white people’s frustrations and their dissatisfactions by the then overwhelming presence of Black people in cities. The large numbers of Black people in cities threatened white people’s power. To whites, it seemed like Black people would be difficult to control in cities than in Homelands . For Whites, apartheid would then re-affirm white superiority and would keep that Black people under their control.

Overcoming Apartheid - the nature of internal resistance to Apartheid before 1960

Internal resistance against apartheid began in the 1950s. This was when anti-apartheid groups rejected the apartheid system. They adopted a programme called the “ programme of action ”, which encompassed other internal resistance programmes such as:

- The Defiance campaign

- The African National congress

- The Freedom Charter

- The women Resistance movement

- Sharpeville Massacre

- Rivonia Trial

Also see: http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/popular-struggles-early-years-apartheid-1948-1960

Review - ‘Apartheid’ becomes an international word; putting South Africa within a broader world context in relation to the uniqueness of Apartheid

Under the apartheid system, the South African profile in terms of foreign relations did not look good. Many countries began ending their relationship with South Africa. As a result, South Africa became relatively isolated. Most countries in the world did not approve of the apartheid system in South Africa. This was because most countries and most people became more aware of human rights and learnt from past experiences of discriminations like the Holocaust .

See: http://www.sahistory.org.za/dated-event/european-community-lifts-sanctions-against-sa

See: http://www.sahistory.org.za/dated-event/un-lifts-mandatory-sanctions-against-sa

In 1946, the United Nations expressed its concerns about South Africa’s discriminatory policies, particularly how South Africa handled the issues of South African Indians , which caused tensions between South Africa and India.

In 1952, after the Defiance Campaign, the United Nations appointed a task team to monitor the progress of the apartheid system in South Africa. Possibly the UN was a bit lenient with South Africa regarding apartheid. Many countries in the UN felt that apartheid was South Africa’s internal issue, and was quite outside from UN issues.

However the UN became hard on South Africa regarding administration of South West Africa (now Namibia ). This was because South Africa had refused grant South West Africa independence to Germany as it was stated on the Treaty of Versailles . The NP treated SWA as the fifth province of South Africa and spread apartheid in the country too.

In 1960 Liberia and Ethiopia called for the International Court of Justice to take legal actions against South Africa’s control of SWA. These two countries realised that apartheid was also expanding to other regions of in south west Africa.

In November 1960, a lawsuit, which would last for six years, was given to South Africa for poor administration of SWA. The International Court of Justice ruled that announced that Ethiopia and Liberia had no right to intervene in South Africa’s internal issues. No further rulings were made by the court regarding South Africa’s legitimacy over the administration of SWA. South Africa then continued to administer SA until its independence in 1988.

After showing signs of improvement on racial discrimination, such as negotiations about ending the apartheid system, the release of Political prisoners like the release of Nelson Mandela in 1990, and the African National Congress ’ lift on the armed struggle, South Africa finally earned its freedom in 1994, and soon formed the

After showing signs of improvement on racial discrimination, such as negotiations about ending the apartheid system, the release of Political prisoners like the release of Nelson Mandela in 1990, and the African National Congress ’ lift on the armed struggle, South Africa finally earned its freedom in 1994, and soon formed the Truth And Reconciliation Commission .

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

State of the Nation Address 2024

Click-to-Save

- Newsletters

- The Presidency

Racism Is still part of the daily South African experience

- Share this:

Dear Fellow South African,

The country has, in recent days, been outraged at the sight of a white student at the University of Stellenbosch degrading and humiliating a fellow black student in a despicable act.

There has been widespread anger that such acts still take place in a country with a bitter past like ours; a past which we have fought so hard to overcome.

It is more troubling that such incidents are happening at schools and places of higher learning. A number of the people involved were born after the end of apartheid.

While the incident at the University of Stellenbosch may seem like an aberration – an appalling act that has been roundly condemned – the truth is that racism is still a feature of every-day life in South Africa. The sooner we recognise that reality, the sooner we can change it.

We know that racism, here and around the world, is driven by feelings of superiority on the part of those who perpetuate it. And although racism can be directed against anyone, it is black people who bear the brunt, both in the past and in the present. As the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement has so strongly asserted, we need to systematically dismantle and eradicate attitudes of white superiority.

It is encouraging and exhilarating to see young South Africans taking the lead in this effort. The thousands of students who have joined protests at Stellenbosch and elsewhere were not responding to just one incident.

They were responding to a deep and pervasive problem in our society, which they themselves have to confront daily.

As Kwenzokuhle Khumalo, a 4th year Management Sciences student and leader, told students on the Stellenbosch campus this week: “You’ve met the wrong generation this time.”

Like the youth of 1976, a new generation of young South Africans is stepping forward to proclaim their birth right and reclaim their future. They are challenging society to grapple with racism, its causes and its effects. As Ms Khumalo rightly said, it is not black people who are the problem and need attention, but those people who still hold on to ideas of white superiority.

It cannot be that the onus must rest with the formerly oppressed as the main victims of racism to advance reconciliation. It cannot be that black South Africans have to continue to prove themselves worthy of dignity and respect.

In a 2016 judgment on a case involving an employee of the South African Revenue Service who was fired for using the k-word at work, Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng wrote: “There are many bridges yet to be crossed in our journey from crude and legalised racism to a new order where social cohesion, equality and the effortless observance of the right to dignity is a practical reality.”

If we are going to cross these bridges, we need to understand what is causing racist attitudes to flourish in our schools and places of higher learning. We need to understand what kind of institutional cultures contribute to racism in the workplace, in social organisations and in communities.

We need frank and honest dialogue between people of different races on the experiences of black people in South Africa 28 years into democracy.

These discussions should be part of the life orientation curriculum in our schools. The arts and culture community should produce content and programming that fully reflects the diversity of the country and the lived experiences of people of all races.

Greater emphasis should be placed on inculcating tolerance and respect for diversity in the classroom from a young age. Parents should be part of this effort because the reality is that racist, chauvinistic and sexist attitudes among the younger generation are often a reflection of what they observe and learn from their parents and older relatives at home.

As many student leaders who took part in protests over the past week said, when it comes to transformation the time for half-measures is over.

This doesn’t only apply to overt racism in schools, workplaces and places of higher learning, but to all of society. Just as racists must be held accountable for their actions, all sectors of society, including business, must advance transformation.

The rights to equality and human dignity are the cornerstones of our Constitution and building a non-racial and non-sexist society is our shared fundamental responsibility.

In complying with employment equity legislation, in advancing broad-based black economic empowerment, in taking practical steps towards redress and undoing the legacy of our discriminatory past, we are not just obeying the law.

We are redressing a grave injustice and building a new country in which race, class and gender no longer determine the circumstances of one’s birth or one’s prospects in life.

Ending racism is not just about changing attitudes; it is also about changing the material conditions that still today separate black and white South Africans.

We have come too far and the sacrifices made have been too great for such appalling acts of racism to turn us against each other. Rather, we must use this incident to confront the issue of race and racial inequality in our society.

It is our wish and expectation that the student population and the broader Stellenbosch university community, both black and white, find each other and rally together to confront racism honestly with courage and truthfulness. They must roundly reject what has happened and express their determination to achieve a learning environment free of bigotry, racism and chauvinism and embrace a non-racial future for Stellenbosch University. By so doing they will set the standard for us all.

With best regards,

- Racism /

- University of Stellenbosch /

- Transformation /

- Diversity

Stay up to date

Get a weekly update on the most pressing issues that interest and affect South Africans – straight from the desk of the President .

- Board Members

- Essay Competition

Latest Updates Racism Watch

Essay: racism in south african schools, a thing of the past.

Mbalenhle Shandu

“You speak so well for a black girl, Mbali!” “You take isiZulu? I would have expected an academic like yourself to rather choose Afrikaans!” “Don’t forget your true people Mbali, you are giving me serious coconut vibes chommie.” “Swimming? Come on Mbalz, why don’t you try netball? It’s more in your forte.”

It has been a staggering 15749 days since students marched for an education that strived to elevate them in all aspects of being; irrespective of their race. Thinking back to the many revolutionists who fought to enable me the opportunities which I eagerly snatch today, it appears that their efforts may have been for nothing as racism continues to pollute classrooms all over our country. Visionaries imagined that classes where people of all races could be educated together would eliminate prejudice towards each other, but the present day South African education system has truly proven otherwise. A system which is extremely boastful about its diversity but is still a slave at the mercy of those with racial intolerance; a true paradoxical state where racism in schools is slowly becoming as prominent as a teacher’s red pen on a marked test. Bullets were fired. Students were killed. New laws were established. History was written. A country transformed – or so we thought.

Growing up, I believed that the idiom “birds of the same feather flock together” was limited to the phylum which soar the skies, but the harsh actuality is that the latter is applicable to students as people of the same race tend to gravitate towards each other at school. Considering how as human beings, we choose to surround ourselves with those who share the same language and culture as us, this truth appears justifiable. Though appearing justifiable, the fact of the matter is that the results of this one component of our break-time buddies continue to hold us back as a community. Racism in schools can be compared to a steadily growing cancer tumor; ignorable in the beginning yet destructive in the most internal ways. Association by skin color creates exclusivity in our schools and limits us to mainly interacting with only our racial groups- causing students to miss so many opportunities to engage with those who differ from them and robbing them of the chances to perceive their classmates beyond the stereotypes.

Having changed learning centres several times during my schooling career, I have come to the sorrowful conclusion that nothing makes trying to settle into a new school environment harder than being discriminated against. As a new student, the teacher had assigned me a buddy named Kelly who I was meant to shadow for my first week, due to our similar subjects. As one would expect, this resulted in me socializing with her clique more often than the other students. Bundled with my unconventional accent, I quickly developed the image of being a ‘stuck-up coconut’, which is a derogatory term used to describe black students who do not conform to stereotypical behavior and whose cliques consist mainly of white people. The basis of this belief of being “brown on the outside and white on the inside”, is that people who seek to break out of the usual race-based friendship circles see themselves as having more societal value than those of the same ethnic group. It stems from the stigma that people of color discard parts of who they are to fit into the desirable margins within our schools, predominately a more “white-washed” approach to who they really are. No words could ever accurately depict the pain I experienced during every Zulu lesson that term where I was ostracized and ridiculed, despite never once claiming to be superior to my peers or trying to resign my true identity for a more Westernized one. NginumZulu phaqa, ungangisoli. Such a belief continues to terrorize students all over the country, as evident with the death of UCT student turned professor, Bongani Mayosi, who committed suicide as a result of being labelled the above and outcast for having opinions which differed from the general consensus of black people; as if we are unable to formulate individual perceptions.

One would expect that being educated in amazing institutions which have developed facilities and opportunities for all students would lead to breakthroughs in various fields but that is simply not the case. My parents had always taught me to be ambitious and perhaps that is what caused me to enter

the interhouse swimming gala when I was in the ninth grade. Instead of the excitement which I had anticipated to receive from my classmates, no one could have ever prepared me for the series of hurtful and embarrassing comments which were spewed at me. Jokes about how black people can’t swim and how I would inevitably drown filled the corridors for days leading up to the event and for the first time, being the subject of attention felt absolutely horrible. The long-anticipated day finally graced us with its presence and my classmates came out in their multitudes to witness my 100m freestyle. To make a long story short, I did end up losing the race and needed help getting out of the pool but what many did not realize is that it was not because of my skin color but rather my unfitness as a swimmer. Students all over the country continue to be victims of marginalization and restricted by what is believed that we can and cannot do, all thanks to stereotypes and untruthful prejudices. This is not only applicable to people of color as I have also witnessed my lighter peers being turned down for specific opportunities such as athletics and cultural activities all because it was believed that it would not be fitting of people of their caliber to participate in those events. Imagine how many more Einsteins, Semenyas, Chad Le Clos’ and Hamilton Nakis would be developed from our education system if students’ abilities and capacities for success were no longer limited and diminished by the stigmas which state otherwise?

As previously mentioned, a big debate that I have found myself within every single year is the

question of why as a top-notch academic, I chose isiZulu instead of Afrikaans as my First Additional Language. Lazy. Inactive. Indolent. These are all the words which I have been called as a result of this. Racism in South African schools is yet again evident in the prioritization of specific activities, subjects and cultures and the negligence of others. Having done isiZulu for the past 5 years at different schools, the common factor is how it is simply not prioritized or taken seriously in comparison to Afrikaans or English. Subjects such as Physical Sciences and Mathematics are glorified over subjects such as Agriculture or Tourism due to how they exhibit more of a Westernized approach to education as opposed to the organic African studies which remind us of home. By encouraging a specific line of thinking and discarding another, we are shown as students that superiority still exists and that perhaps what makes us proud citizens of this country is not worthy of recognition or valid. It is disheartening to see students lose their passion and parts of who they are all thanks to the education system subconsciously showing them that what may be cherished by one ethnicity of people will never be seen as important or applause worthy as that which is cherished by another. It’s not just cutting the costs but also cutting the dreams and making students doubt the value of their futures.

Ahmed Kathrada wisely stated that “ The hardest thing to open is a closed mind.” Ignorance will never become diminished by acting as if the above problems do not exist but will come from the intermingling of students from all different walks of life, because we are people first before we are our races. In spite of all of the biases and discrimination which torment our schools, I remain optimistic for the unprejudiced treatment that students in our country will receive and lavish on each other; irrespective of skin color. Sticks and stones may break our bones but it is the words and kindness which we as South African students need to exhibit which will heal them and finally bring about the change that those who came before died to make a reality.

What to read next

Articles latest updates news uncategorised, anti-racism week 2024 – media resource page, the amrit bhowan-laloo chiba scholarship, ahmed kathrada foundation announces winners of essay writing compeition againts racism.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

General enquiries: Tel: +27 (0)11 854 0082 Fax: +27 (0)11 852 8786 [email protected]

Media enquiries: Tel: +27 (0)78 547 4981 [email protected]

Youth enquiries: [email protected]

Signet Terrace Office Park, Block B, Suite 2 19 Guinea-Fowl Street Lenasia, Gauteng, 1827 South Africa

P.O. Box 10621 Lenasia, Gauteng, 1820 South Africa

ABOUT FOUNDATION

In pursuing its core objective of deepening non-racialism, the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation will:

Promote the values, rights and principles enshrined in the Freedom Charter and the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa;

Collect, record, promote and display, through historical artefacts and contemporary material.

- ANTI-RACISM WEEK 2024 – MEDIA RESOURCE PAGE 27th Feb 2024

- The Amrit Bhowan-Laloo Chiba Scholarship 13th Feb 2024

- AHMED KATHRADA FOUNDATION ANNOUNCES WINNERS OF ESSAY WRITING COMPEITION AGAINTS RACISM 30th Dec 2023

Advertisement

Medical Mistrust and Enduring Racism in South Africa

- Symposium: Institutional Racism, Whiteness, and Bioethics

- Published: 05 January 2021

- Volume 18 , pages 117–120, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Tessa Moll ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7230-7082 1

4399 Accesses

6 Citations

54 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In this essay, I argue that exploring institutional racism also needs to examine interactions and communications between patients and providers. Exchange between bioethicists, social scientists, and life scientists should emphasize the biological effects—made evident through health disparities—of racism . I discuss this through examples of patient–provider communication in fertility clinics in South Africa and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic to emphasize the issue of mistrust between patients and medical institutions. Health disparities and medical mistrust are interrelated problems of racism in healthcare provision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Insiders’ Insight: Discrimination against Indigenous Peoples through the Eyes of Health Care Professionals

Lloy Wylie & Stephanie McConkey

Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition

Elana Curtis, Rhys Jones, … Papaarangi Reid

The Costs of Institutional Racism and its Ethical Implications for Healthcare

Amanuel Elias & Yin Paradies

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In her essay arguing that bioethicists be at the forefront of conversations with life scientists on race, philosopher Camisha Russell ( 2021 ) outlines three ways that race is often framed in both biomedical and lay circles. These are 1) “race science,” the largely discredited idea that race has a basis in the natural world and is therefore ultimately “verifiable by science,” 2) race as a social construct, meaning that race emerges from the social meanings that are gathered from “natural physiological differences,” 3) race as a driver of historical progress that underlies differing teleologies to a so-called developed modernity (what white nationalists often argue). In her fourth offer, Russell contends that, at its most fruitful, thinking with race as a technology allows us to move beyond the question of what race is and instead ask what race does.

In my role as an anthropologist, my fieldwork brought me not to the researchers of life science but their clinical practitioners, in the tense and tender interactions between clinical medicine and patients in South African fertility clinics. These are often overlooked moments in thinking about race in the life sciences; the legacy of “race science” and notions of genetic difference looms long and large. But genetics is not the only space for locating ideas of racial difference. As Anne Pollock argues:

Race in biomedicine does not originate in the science and filter down to the doctors’ offices; neither does it simply filter up. It does slightly different work in each sphere, but gains its durability through its capacity to travel between them. ( 2012 , 5)

Less a question of its “realness” in office spaces, race certainly has very real effects. These effects I contextualize and embed in South Africa. As Russell has previously argued ( 2016 ), voices on the margin need to also be brought forth to the centre of philosophical and bioethical discussions of justice. Thinking about legacies and lessons and manifestations of race and bioethics need not always centre U.S. histories. In those moments in South Africa like the vignette below, race is a category that shapes all manner and measure of interactions, decisions, and engagement between staff and patients. While life scientists have done well to argue against a biological basis for racialized difference, I, like Russell, encourage them to recognize the biological effects of racism. These include, but are not limited to, the ongoing mistrust between medical institutions and many communities and the enduring health disparities emerging from racialized political economy.

During my fieldwork in fertility clinics, I often sat with clinic staff as they explained to patients how IVF worked and guided them through the key decisions that they would have to make in the coming weeks. Despite spending three months at one clinic, I encountered only a single black couple coming in for IVF. Like many spaces of post-apartheid life, fertility clinics in South Africa are deeply segregated spaces. While white people make up less than 10 per cent of the population, the vast majority of IVF patients and all the professional medical staff that I met were white. Footnote 1 Patients were more diverse, including some patients from nearby Angola, Namibia, and Zimbabwe, but the majority were also white. No doubt the high cost of IVF cycles in private clinics—and twelve of fifteen fertility clinics in South Africa are private—becomes a de facto form of racial segregation as wealth remains cloistered among a persistently white local elite.

A black couple came in one day searching for biomedical solutions for their problem —married for two years and they had yet to fall pregnant. Both had children from previous partnerships but desired a child together. Originally from Mthata, a regional hub in the Eastern Cape, the couple now lived near Cape Town, where the man, Fundani, ran and owned a shebeen , an informal local tavern. Estie, the clinic staff member, came to explain IVF and ask them questions about their relationship, understanding of the process, and experience of trying to conceive. At least that would be the typical procedure I had seen from her on several occasions. This case began similarly but quickly veered into discourses of racialized culturalism that endure in white spaces of South Africa. While race science—the notion of race being a biologically-rooted form of difference—provided a form of “scientific legitimacy” to the apartheid regime, culture was also a significant fulcrum of difference in the logic of South African white supremacy (Dubow 1995 ). This too was backed with “science,” as volkekunde anthropologists contributed the theoretical backing for social segregation along demarcations of culture (Sharp 2007 ). Racialized culturalism refers to the ways that “culture” emerges as a rationale for racial difference, a discourse I had all too often been privy to as a white person living in South Africa today.

In the clinic, as I observed, Estie, who was white, asked Fundani and Colleen how long they had been “struggling to fall pregnant.” Two years, they said—since their wedding. Then, Estie continued, “In black culture, it’s much more difficult when you want a baby; your wife can be an outcast. But it’s different in your case because you both have children. In your culture, you must have a child.” They nodded along as she spoke. Estie continued, asking about their relationship; “No fights?” No, Fundani and Colleen said, no fights. “Do you have enough money to raise the child?” Fundani nodded. “How much was lobolo Footnote 2 ? How many cattle?” Fundani chuckled but didn’t answer. “Were you married traditionally?” Yes, Colleen said. “Do you have just the one wife or more than one wife?” He said just one wife. Estie asked what he did, and he said he sold beer. “You have a shebeen ? Are you a drinker? Alcohol can hurt those sperms that we need for making the baby.” He said that he didn’t drink, and his wife, Colleen, reiterated, “No, no, he doesn’t drink, he’s a good man.” These are questions and allusion that I never saw lobbed at white couples.

When it came time for the couple to make some medical decisions—How did they feel about freezing extra embryos? Did they want to use the more expensive incubator?—Fundani asked the medical professionals to leave the room and instead asked me, the outsider anthropologist, what I thought they should do. I was, and am, not a medical professional; I couldn’t offer medical advice and was clear about that. He asked why the extra cost for freezing? I explained why freezing costs money—liquid nitrogen, storage space—but also why it can be beneficial to have frozen embryos rather than “start from scratch.” He seemed satisfied with my explanations—and my limitations as someone without medical training. After the couple left, I spoke with the medical staff about the situation. “We should have a translator here next time,” mused Estie. Estie thought it was an issue of language. I thought it was an issue of trust, and one that went both ways. In my reading, Estie did not trust Fundani and Colleen. Their racial difference marked them as suspect and having questionable motives for parenthood and family relations, and she suspected they lacked in resources to pay for treatment and care for a potential child. In response, Fundani and Colleen clearly did not trust Estie, nor the other medical staff. In my reading, they felt the mistrust and in turn worried that were being potentially duped—that the clinic staff were after their money rather than helping them with their problem. Ironically, I believe that Estie’s line of questioning came from a place of concern with providing what some medical programmes refer to as “culturally competent care” (see Jenks 2010 ).

One often thinks of mistrust in medical institutions as arising from specific and infamous moments of unethical research. For instance, in the introduction to their special issue on public trust and expert knowledge, Camporesi, Vaccarella, and Davis ( 2017 ) reference the Tuskegee Syphilis Study in the United States, where doctors knowingly withheld treatment for six hundred black men. In South Africa, we have fresh in our minds the apartheid-era Project Coast and the plans (recounted in the late 1990s Truth and Reconciliation Commission) of biological warfare against the black population using, but not limited to, the dissemination of anthrax, the purposeful deployment of cholera in high-density neighbourhoods, and the use of sterilizing oral contraception (Fassin 2015 ). And yet the public are also comprised of people, each with their individual tales of doctor–patient interactions, and many like Fundani and Colleen.

The need for a thinking about race and the institutions of life sciences has become ever more urgent. The world has changed immensely in the mere weeks since Russell set out her call for collaboration between bioethics and life sciences on the lessons of race. In those weeks, COVID-19 has, as of this writing, emerged in nearly three million confirmed cases, and claimed the lives of at least several hundred thousand. Footnote 3 I, along with nearly a third of the world, am under lockdown, connected to friends, family, and news of the world via WhatsApp and Zoom. While our intimate connections are increasingly framed as threats in themselves, the information connections flourish, allowing for a different kind of threat. State health officials and researchers’ peer-reviewed work sits side by side with the ramblings of the U.S. president and other dubious sources. Our present condition flattens credibility, confusing questions of validity and expertise. In South Africa, where I write and reside, I have read online that drinking hot tea can kill the virus. There is an ongoing theory about its source involving the Chinese state and 5G installations. A member of parliament wrote to President Cyril Ramaphosa asking for clarification on why Bill Gates had been in Cape Town earlier in the year (for a charity tennis match), citing rumours that the billionaire had come to discuss secret vaccine trials in Africa.

Like many rumours and theories, the latter comes with scaffolds of present and historical truths. In early April, two French scientists discussed on television whether to test a COVID vaccine on Africans. After public denouncements, they attempted to clarify that they merely wanted to ensure that Africa was included in vaccine trials. As Fiona Ross ( 2020 ) writes, “We do not come to this disease as tabula rasa.” This is true in more ways than one. Many South Africans come to COVID with durable legacies (see Stoler 2016 ) of apartheid-era Project Coast and contemporary enduring and daily experiences of racism. Many South Africans know well the biopolitical stratifications of life and how medicine has often worked alongside those stratifications, if not sedimented in them.

When the virus first came to South Africa, many suggested that it only affected white people. This was bolstered by the fact that the first cases were all white people, those coming from holidays abroad. As Adia Benton ( 2020 ) describes, “Viruses move in bodies, and the freedom of certain bodies, certain people, to move across borders needs to be acknowledged.” This is an acknowledgement to counter the common narrative that viruses know no border, no class, no race. Viruses, this narrative goes, reduce us all to mere biology: deracialized, decontextualized biology. The statistics would beg to differ. In the United States, early figures from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) show that 33 per cent of COVID hospitalizations were among black patients, despite them comprising 18 per cent of the population in the catchment area. Health disparities, an effect of racism and economic stratifications, underly the differing co-morbidities of hypertension, obesity, and chronic lung disease (CDC 2020 ). This is certainly in the minds of South Africa’s political and public health leaders, who have implemented one of the strictest lockdowns in the world. Efforts to slow the spread approach dry tinder: a population largely impoverished by decades of white supremist rule, many immuno-suppressed from HIV/AIDS, one of the highest rates of tuberculosis, and living in high-density neighbourhoods. The understanding that the social emerges in biology, or what Margaret Lock ( 1993 ) referred to as “local biologies,” has gained greater traction in recent years. Epigenetics research now suggests the enduring impression of social stratification in genetic expression (Krieger 2000 ; Kuzawa and Sweet 2009 ). Legacies of racism may now be etched in bodies in ways surprisingly material and frustratingly durable (Meloni 2017 ).

These twinned legacies—mistrust of scientific expertise and institutions and enduring racial health disparities—are of course interrelated. They come from moments that make headlines and moments that do not. I do not know if Fundani and Colleen ever came back for IVF treatment or if they ever became pregnant. They certainly understood the roots of the treatment they experienced at the clinic and, I surmise, felt they weren’t getting proper care as a result. Regardless of the ontological status of race in that moment, whether it came in the form of racialized culturalism or scientific racism, the impacts of it were immediate. The current global pandemic brings the need for bioethicists, social scientists, and life scientists to work collaboratively and reflexively to recognize the complicated place of race, both historically and in the present, to ever greater urgency. Simultaneously to that, we also need to reflect on whether we (and here I include anthropologists like myself) deserve any such trust to have these conversations and to have them well. Many disciplines, life and social sciences alike, have legacies that long need understanding, reflecting, and ideally upending in order to move forward with this critical work.

I conducted fieldwork in three clinics in urban centres of South Africa. The racial homogeneity was and is not the case for all clinics across the country; however, fertility medical staff remain predominantly white. For instance, at the time of my fieldwork in 2015−2016, all the physicians in Cape Town were white.

Lobolo is the customary payment from a male partner to the women’s family as part of the marriage process. Cattle are the main sources and denominations of payment.

The rate of infection still astonishes me. How woefully out-of-date this number will be by the time this essay goes to press.

Benton, A. 2020. Border promiscuity, illicit intimacies, and origin stories: Or what Contagion’s bookends tell us about new infectious diseases and a racialized geography of blame. Somatosphere , March 6. somatosphere.net/forumpost/border-promiscuity-racialized-blame /. Accessed November 28, 2020.

Camporesi, S., M. Vaccarella, and M. Davis. 2017. Investigating public trust in expert knowledge: Narrative, ethics, and engagement. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 14(1): 23–30.

Article Google Scholar

CDC (Centers for Disease Control). 2020. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69(15): 458–464.

Dubow, S. 1995. Scientific racism in modern South Africa . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Google Scholar

Fassin, D. 2015. Adventures of African nevirapine: The political biography of a magic bullet. In Para-States and Medical Science: Making African Global Health , edited by P. Geizler, 333–353 . Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Jenks, A. 2010. What’s the use of culture? Health disparities and the development of culturally competent healthcare. In What’s the use of race? Modern governance and the biology of difference , edited by I. Whitmarsh and D.S. Jones, 207–224. Cambridge, USA: MIT Press.

Krieger, N. 2000. Refiguring “race”: Epidemiology, racialized biology, and biological expressions of race relations. International Journal of Health Services 30(1): 211–216.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kuzawa, C.W., and E. Sweet. 2009. Epigenetics and the embodiment of race: Developmental origins of US racial disparities in cardiovascular health. American Journal of Human Biology 21(1): 2–15.

Lock, M. 1993. Encounters with aging: Mythologies of menopause in Japan and North America . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Meloni, M. 2017. Race in an epigenetic time: Thinking biology in the plural. The British Journal of Sociology 68(3): 389–409.

Pollock, A. 2012. Medicating race: Heart disease and durable preoccupations with difference. Durham, USA: Duke University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Ross, F. 2020. Of soap and dignity in South Africa’s lockdown. Corona Times , April 8. https://www.coronatimes.net/soap-dignity-south-africa-lockdown/ . Accessed November 28, 2020.

Russell, C. 2021. Bioethicists should be helping scientists think about race. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1007s11673-020-10068-x.

Russell, C. 2016. Questions of race in bioethics: Deceit, disregard, disparity, and the work of decentering. Philosophy Compass 11(1): 43–55.

Sharp, J. 2007. The roots and development of Volkekunde in South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies 8(1): 16–36.

Stoler, L.A. 2016. Duress: Imperial durabilities in our times . Durham, USA: Duke University Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalization, Deakin University, 221 Burwood Hwy, Burwood, VIC, 3125, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tessa Moll .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Moll, T. Medical Mistrust and Enduring Racism in South Africa. Bioethical Inquiry 18 , 117–120 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-020-10072-1

Download citation

Received : 29 April 2020

Accepted : 30 November 2020

Published : 05 January 2021

Issue Date : March 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-020-10072-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- South Africa

- Medical mistrust

- Racialized culturalism

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

RACISM IN SOUTH AFRICA

2018, isara solutions

Racial discrimination in South Africa is unique in the world. The black communities in South Africa were against racism and the policy of their government. Identity is the other problem for the black and colored South Africans during the apartheid regime. Apartheid is generally understood as comprising a set of racially discriminatory policies and enforced racial segregation. It covered all aspects of life in South Africa, political, social, and economical. As South Africa has a long history of foreign occupation, settlement and urbanization, this led to an abundant literature of protest, inequality and discrimination under apartheid. To understand this issue, it is pertinent to trace its history. As historically speaking, initially Africa was just a continent and was not divided into the countries, it becomes pertinent to study this issue by dividing this history into 3 stages, namely, pre-colonial Africa, colonial Africa and South Africa and the beginning of the racial practices.

Related Papers

Mark Fredericks

Vanessa Rolke

Stichproben. Vienna Journal of African Studies

Birgit Englert

Prof. Dr. Dr. Paul Oluwole-Olusegun

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa, is the southernmost sovereign state in Africa. It is bounded on the south by 2,798 kilometers of coastline of Southern Africa stretching along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans, [9] [10] [11] on the north by the neighbouring countries of Namibia, Botswana and Zimbabwe, and on the east by Mozambique and Swaziland, and surrounding the kingdom of Lesotho. [12] South Africa is the 25th-largest country in the world by land area, and with close to 53 million people, is the world's 24th-most populous nation. It is the southernmost country on the mainland of the Old World or the Eastern Hemisphere. [13]

Monica Inés Cejas

Anthony Löwstedt

De Gruyter eBooks

Hugo van der Merwe

12 Lenses into Diversity in South Africa

The early promises of a unified South Africa as a rainbow nation after its first democratic election in 1994 and a breakaway from minority rule, has certainly in its delivery, in the main, been forgotten, side-lined, faded or adjusted, 27 years on. A major part of the country’s centuries-old colonial history, Apartheid history and post-Apartheid/democratic history have always been intertwined with race. In 1994, the democratically-elected tripartite alliance – the African National Congress (ANC), the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the South African Communist Party (SACP) – introduced legislative measures to eradicate racism. One research participant for this book chapter (P4, Camissa, identifying as female) reflected on the promise: “I was so excited that I was finally going to be considered a full human… at work, in the shops, on the road, when travelling… without the accompanying filters through which other people viewed me. I believed that there would be no more racism… I could get any job, if I was qualified for it. I could live anywhere, if I could afford it. I could go to museums and restaurants with other people, if I paid for it. I could openly date and marry people from other races, if I was in love and inclined to do so. The stares would stop. The suspicion would stop. I could stop pretending… I could be me and be accepted for being me”. In addition to scrapping the Apartheid legislation, an extensive policy and legal framework was developed to promote affirmative action in education, employment, sport and other areas of life, including a far-reaching programme of Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (B-BBEE). B-BBEE has attempted to move diversity from being a political ideal to a practical business mandate. The belief in the end of racism in the nation, as well as the promise of a non-racial society, have endured in the minds of many citizens, however researchers and writers have, over the years, highlighted some of the enduring social, political and economic obstacles to the development of a mature, non-racial democracy in South Africa. These include low levels of industrialisation; poor public service delivery; ailing state-owned enterprises; widespread poverty; high levels of unemployment; violence; homelessness; weakened governance structures, particularly at municipality levels; considerable inequality in the distribution of wealth; skewed land ownership; low skills levels of the majority of the population; and a low educational level of large segments of the population. These latter issues are not the substantive focus of this chapter however, as they have been extensively explored and written about in relation to race, and are still being written about by researchers and journalists alike. Instead, this chapter will seek to shine a light on the less-mentioned aspects of racism in South Africa, specifically the changing narratives and therefore outworking of racism, and the resulting psychological and behavioural effects on those who reside in the country.

vusi sithole

The evils and atrocities of the apartheid government had far reaching effects that can be imagined. To capture the essence of negative effects and impact of the apartheid system is a daunting task, because the apartheid government committed evils above what may be perceived as genocide or any form of harm to the black citizens of South Africa. To many people and the world, the evils of Apartheid are perceived to have been affecting the black South Africans than any race in the country. little do some people know how terrible Apartheid was to all South Africans including the white minority citizens. The white minority government that crafted segregatory laws which were enforced to suppress and dehumanise black South Africans, did not realise how toxic and deadly those laws were to the white community and how these would play themselves in the future democratic South Africa, which was in any way not expected by white communities. This paper scrutinises the Apartheid laws and how they impacted on the entire South African citizenry, including the white communities.

Kevin Durrheim

RELATED PAPERS

Pontos de Interrogação — Revista de Crítica Cultural

Journal of Educational and Psychological Studies [JEPS]

Hisham Makaneen

Polo del Conocimiento

Rossana Dolores Toala Mendoza

Ario Satria

Medicina Fluminensis

daria sfeci

International Journal of Morphology

Fabiola Bustamante

Indonesian Journal of Tropical and Infectious Disease

Endang Sutedja

Estudos em Avaliação Educacional

CLEONICE TOMAZZETTI

Nugent Maria

Suhirman Suhirman

International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research

Dr. Chandrashekhar Jagannath Patil

ACS Symposium Series

IFAC Proceedings Volumes

Alexander Petroianu

E3S Web of Conferences

Kazuya Shide

Berichte zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte

Michael Eckert

AIP Conference Proceedings

Eko Saputra

Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings

Kaleem Khan

Parasitology Research

Naima Berber

Archives of Microbiology

Sathyanarayana Reddy Gundlapally

Pediatric Nephrology

alessandra coelho noronha

Clinical Cancer Research

Domagoj Vucic

Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology

Frank Starmer

Klimik Dergisi/Klimik Journal

Esra Akaydın Gültürk

European Heart Journal

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

What young people have to say about race and inequality in South Africa

Senior researcher, Durban University of Technology

Senior Lecturer, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Disclosure statement

Kira Erwin has received funding from the National Research Foundation, as well as other external funders for research projects at the Urban Futures Centre at the Durban University of Technology.

Kathryn Pillay receives funding from the National Research Foundation.

University of Kwa-Zulu Natal provides funding as a partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

View all partners

Meritocracy is the belief that holding power or success should be judged on people’s individual ability, rather than on wealth or social connections. At first glance, this appears to be a reasonable proposition. But the focus on individual merit becomes harder to fathom as one enters the messy world of structural inequality and discrimination.

As our research shows, ideologies of meritocracy and individualism create obstacles for collective action towards a more equal and just society. Our findings were published in the book Race in Education , the outcome of a thinktank on the effects of race at the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study.

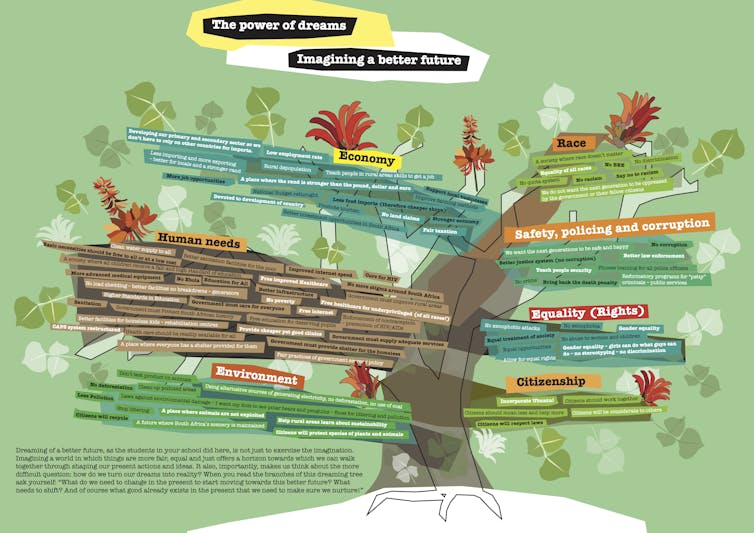

Using a methodology called Dreaming Workshops , our study explored how Grade 11 students, of around 16 and 17 years old, from different schools in the South African coastal city of Durban imagined race, racism and non-racialism in a utopian future.

Young South Africans are being socialised into a highly racialised society and experience severe disparities. Expecting them to eradicate racism without dismantling material inequalities is a deferral of adult responsibility. Mindful of this, we designed a study to listen to young people’s ideas, as opposed to looking to them for solutions.

Complex views

The five schools that participated in this study, three government and two private, are located in a middle-class, formerly “white” area in Durban. The schools have, on average, a diverse but mostly middle-class student body, with some students travelling from townships to attend class. Under apartheid townships were poorly resourced and under-serviced residential spaces designated for people racialised as black. Each school in the study had approximately 20 students per class. One school markets itself as girls-only, one as boys-only, the other three are open to all genders.

Young people involved in the study were deeply aware of inequality. For them, reducing inequality was a priority if the country was to move towards a better future.

It is notable that non-racialism was not a concept volunteered by any of the students as a future ideal, despite it being a constitutional principle in South Africa. At present there is little clarity on the meaning of non-racialism. It is equated to a multiplicity of ideas, among them mobilisation against apartheid, multiracialism, multiculturalism, nation-building, and race-blindness.

What students did want eradicated from their utopia was racial discrimination and racism. The meanings they attached to race shifted depending on the conversation, for example, race when it related to racial quotas as opposed to race when it related to culture, identity or politics.

Racial identities played an important role in these young people’s sense of self. But some thought it is the “weirdest thing ever” that people sit in “race groups” during lunch breaks. They make sense of this by explaining that people sit with others who share their culture. Using race and culture as proxies for each other is very much part of the South African experience of racialisation.

The “commitment” to racial identities, however, was more complex than it first appeared. There was an uneasiness between accepting and feeling pride in racial identities, and not wanting them to count as measures of social value. They frequently vocalised a rejection of racial stereotypes and racism.

In each school, there were students committed to eradicating their own racist thoughts, who openly challenge parents and family members about racism and actively refused to essentialise their peers. Students felt a generational responsibility to challenge racial stereotypes.

They were also vehemently against race as a category in government policies. Arguments against racial quotas, such as broad-based black economic empowerment and affirmative action (race-based legislation aimed to redress past and current discriminations) were present in all the schools. As were statements that “we need to get over blaming the past”, or linking poverty with laziness, or refusing to recognise the role of privilege in individual achievement.

These sentiments reflected a socialisation process happening at schools, and in the family, that raised real tensions for young people. Many students were taught to believe that individual hard work pays dividends. Principles of individual success and meritocracy were well established in their homes, and valorised daily at their schools. Schools acutely focused on individual competition in sports and academic achievements, rewarding individual rather than collective effort.

The “wiping out” of the individual in favour of a group racial identity for employment and university entry appeared unfair and contradictory to the meritocratic values they were being taught to aspire to.

Read more: We need to unpack the word 'race' and find new language

These views were present in students who would be racialised as belonging to all four of South Africa’s racial categories, socially constructed in this country as black, Indian, Coloured and white.

Meritocratic arguments were also against the redistribution of wealth in South Africa. Taxing the rich was often seen as “making the poor lazy”. Here, class privilege was indiscernible from what would usually be thought of as a defence of white privilege.

In our view meritocratic sentiments are highly problematic in the context of structural inequality. In South Africa there is no equal playing field on which to justify individual merit.

It is not just race-blindness that we should guard against in South Africa; class-blindness too leads to a repetition of the status quo. Since structural inequalities fundamentally enable reproductions of racism this creates a complex dilemma for these students.

What does it mean to desire social justice and equality but refuse to “give up” any privileges?

This dilemma poses a challenge for education in South Africa. Certainly more frank and critical classroom conversations on race, class and culture are needed. More pressing is how to restructure schooling so that it is less focused on individual merit and reward.

This article is part of a series . Other authors include Barney Pityana, Göran Therborn, Nina Jablonski, George Chaplin and Njabulo Ndebele.

The three edited volumes of essays published by African Sun Media in 2018 ( The Effects of Race , edited by Nina G. Jablonski and Gerhard Maré), 2019 ( Race in Education , edited by Gerhard Maré), and 2020 ( Persistence of Race , edited by Nina G. Jablonski) contain the complete representation of the project’s scholarship.

- High school students

- Peacebuilding

- non-racialism

- KPMG South Africa

- #EffectOfRaceSeries

- race and culture

Biocloud Project Manager - Australian Biocommons

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Deputy Editor - Technology

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Racism in South Africa can be traced back to the earliest historical accounts of interactions between African, Asian, and European peoples along the coast of Southern Africa. It has existed throughout several centuries of the history of South Africa, dating back to the Dutch colonization of Southern Africa, which started in 1652. Before universal suffrage was achieved in 1994, White South ...

Grade 11 - Apartheid South Africa 1940s to 1960s. The global pervasiveness of racism and segregation in the 1920s and 1930s. During the 1920s and 1930s, there were discriminatory policies in different parts of the world. These were mostly in European countries like Britain and European colonies like South Africa.

The implication is that even if South Africa's politics officially subscribe to non-racialism, the physical and psychological violence inflicted upon the African majority cannot be wished away ...

As South Africa marks Human Rights Month, commemorating the struggle for democracy, it is a moment to reflect on the lingering scars that still influence policing in the country.

Essay On Racism In South Africa. 1579 Words7 Pages. As humans, we have come a long way and we have overcome a lot of great difficulties. Be it war, disease, natural calamities, man-made disasters, you name it and we have crossed it. But over all these years, we seem to have missed the point that all the tragedies that we come to face with are ...

Racism Is still part of the daily South African experience. The country has, in recent days, been outraged at the sight of a white student at the University of Stellenbosch degrading and humiliating a fellow black student in a despicable act. There has been widespread anger that such acts still take place in a country with a bitter past like ...

The 63-page report, "'They Have Robbed Me of My Life': Xenophobic Violence Against Non-Nationals in South Africa," details xenophobic incidents in the year after the government adopted the ...

This equipped it poorly to respond to and make sense of racism and modern South Africa. Black commuters defiantly board a train reserved for whites during apartheid in 1952. Bettman via Getty Images

Racism is global detrimental reality that has destroyed the peaceful social order in South Africa in the name of Colonialism and Imperialism by European countries from 1652-1961.

Racial segregation had long existed in white minority-governed South Africa, but the practice was extended under the government led by the National Party (1948-94), and the party named its racial segregation policies apartheid (Afrikaans: "apartness").The Population Registration Act of 1950 classified South Africans as Bantu (black Africans), Coloured (those of mixed race), or white; an ...

It's 2019, almost 25 years into South Africa's democratic dispensation, and racism is still playing out in the country's schools. Most recently, a primary school teacher was accused of ...

These are all the words which I have been called as a result of this. Racism in South African schools is yet again evident in the prioritization of specific activities, subjects and cultures and the negligence of others. Having done isiZulu for the past 5 years at different schools, the common factor is how it is simply not prioritized or taken ...

Health disparities, an effect of racism and economic stratifications, underly the differing co-morbidities of hypertension, obesity, and chronic lung disease (CDC 2020 ). This is certainly in the minds of South Africa's political and public health leaders, who have implemented one of the strictest lockdowns in the world.

This collection of essays only scratches the surface in terms of uncovering the myriad viewpoints that emerged from the left amidst South Africa's particular combination of capitalism and racism. Nonetheless, we hope that readers will appreciate that South African theorizing is not only important because it coined a phrase - racial capitalism.

In June 2020, I was in the process of phasing out my Facebook account when I stumbled upon a post about racism and discrimination at my South African high school. The increased momentum for the Black Lives Matter movement after a police officer murdered George Floyd in the U.S. had provoked an online conversation among alumni about how teachers ...

CASIRJ Volume 9 Issue 1 [Year - 2018] ISSN 2319 - 9202 RACISM IN SOUTH AFRICA Dr. Tarakeshwari Negi Associate Professor Department of Political Science Satyawati College Evening University of Delhi Racial discrimination in South Africa is unique in the world. The black communities in South Africa were against racism and the policy of their ...

Young South Africans are being socialised into a highly racialised society and experience severe disparities. Expecting them to eradicate racism without dismantling material inequalities is a ...

897 Words4 Pages. Generally in South Africa racism is a discrimination against a person of a specific race under the belief that he or she is superior to the other whereas in a broader sense globally racism is defined as a discrimination against another person on the basis of their race, or an event that reduces human dignity through actions ...

This essay sample was donated by a student to help the academic community. Papers provided by EduBirdie writers usually outdo students' samples. It can be seen to a large extent that South Africa is less racist since apartheid. Life during apartheid was harsh due to radical laws imposing segregation between blacks and whites.

November 2020 · Sociology of Race and Ethnicity. The nation-state is one powerful entity that makes race. For instance, the mid-twentieth-century South African apartheid racial state cultivated a ...

According to Obi Akwani "It has been nearly a decade and a half after the end of apartheid" and South Africans are finally realizing there is a problem with racism (Akwani, 2008). This realization occurred after white students from the University of the Free State, made a racist video.