Understanding Gender, Sex, and Gender Identity

It's more important than ever to use this terminology correctly..

Posted February 27, 2021 | Reviewed by Kaja Perina

- The Fundamentals of Sex

- Find a sex therapist near me

Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene hung a sign outside her Capitol office door that said “There are TWO genders: MALE & FEMALE. ‘Trust the Science!’” There are many reasons to question hanging such a sign, but given that Rep. Taylor Greene invoked science in making her assertion, I thought it might be helpful to clarify by citing some actual science. Put simply, from a scientific standpoint, Rep. Taylor Greene’s statement is patently wrong. It perpetuates a common error by conflating gender with sex . Allow me to explain how psychologists scientifically operationalize these terms.

According to the American Psychological Association (APA, 2012), sex is rooted in biology. A person’s sex is determined using observable biological criteria such as sex chromosomes, gonads, internal reproductive organs, and external genitalia (APA, 2012). Most people are classified as being either biologically male or female, although the term intersex is reserved for those with atypical combinations of biological features (APA, 2012).

Gender is related to but distinctly different from sex; it is rooted in culture, not biology. The APA (2012) defines gender as “the attitudes, feelings, and behaviors that a given culture associates with a person’s biological sex” (p. 11). Gender conformity occurs when people abide by culturally-derived gender roles (APA, 2012). Resisting gender roles (i.e., gender nonconformity ) can have significant social consequences—pro and con, depending on circumstances.

Gender identity refers to how one understands and experiences one’s own gender. It involves a person’s psychological sense of being male, female, or neither (APA, 2012). Those who identify as transgender feel that their gender identity doesn’t match their biological sex or the gender they were assigned at birth; in some cases they don’t feel they fit into into either the male or female gender categories (APA, 2012; Moleiro & Pinto, 2015). How people live out their gender identities in everyday life (in terms of how they dress, behave, and express themselves) constitutes their gender expression (APA, 2012; Drescher, 2014).

“Male” and “female” are the most common gender identities in Western culture; they form a dualistic way of thinking about gender that often informs the identity options that people feel are available to them (Prentice & Carranza, 2002). Anyone, regardless of biological sex, can closely adhere to culturally-constructed notions of “maleness” or “femaleness” by dressing, talking, and taking interest in activities stereotypically associated with traditional male or female gender identities. However, many people think “outside the box” when it comes to gender, constructing identities for themselves that move beyond the male-female binary. For examples, explore lists of famous “gender benders” from Oxygen , Vogue , More , and The Cut (not to mention Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head , whose evolving gender identities made headlines this week).

Whether society approves of these identities or not, the science on whether there are more than two genders is clear; there are as many possible gender identities as there are people psychologically forming identities. Rep. Taylor Greene’s insistence that there are just two genders merely reflects Western culture’s longstanding tradition of only recognizing “male” and “female” gender identities as “normal.” However, if we are to “trust the science” (as Rep. Taylor Greene’s recommends), then the first thing we need to do is stop mixing up biological sex and gender identity. The former may be constrained by biology, but the latter is only constrained by our imaginations.

American Psychological Association. (2012). Guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. American Psychologist , 67 (1), 10-42. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024659

Drescher, J. (2014). Treatment of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. In R. E. Hales, S. C. Yudofsky, & L. W. Roberts (Eds.), The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychiatry (6th ed., pp. 1293-1318). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Moleiro, C., & Pinto, N. (2015). Sexual orientation and gender identity: Review of concepts, controversies and their relation to psychopathology classification systems. Frontiers in Psychology , 6 .

Prentice, D. A., & Carranza, E. (2002). What women should be, shouldn't be, are allowed to be, and don't have to be: The contents of prescriptive gender stereotypes. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 26 (4), 269-281. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.t01-1-00066

Jonathan D. Raskin, Ph.D. , is a professor of psychology and counselor education at the State University of New York at New Paltz.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Gender vs. Sexuality: What's the Difference?

Cynthia Vinney, PhD is an expert in media psychology and a published scholar whose work has been published in peer-reviewed psychology journals.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/cynthiavinney-ec9442f2aae043bb90b1e7405288563a.jpeg)

Dr. Monica Johnson is a clinical psychologist and owner of Kind Mind Psychology, a private practice in NYC specializing in evidence-based approaches to treating a wide range of mental health issues (e.g., depression, anxiety, trauma, and personality disorders). Additionally, she works with marginalized groups of people, including BIPOC, LGBTQ+, and alternative lifestyles, to manage minority stress.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Dr-Monica-Johnson-d254c48e06be4690a2423d260b1130bd.jpeg)

Ronniechua / Getty Images

- Differences

- Discrimination Impact

Gender and sexuality are often assumed to be related concepts but, in reality, they are separate and distinct. Understanding the difference between gender vs. sexuality is important because, while both are important parts of an individual's sense of self, if you don't know what each one is, you may make incorrect assumptions.

For example, some people may assume that someone who is transgender is gay. But a transgender person's gender identity and sexual orientation aren't connected.

This article begins by defining gender identity and describing the differences between gender identity, gender expression, and sex. It then defines sexual orientation and discusses sexual fluidity. Finally, it details the impact of discrimination against gender diverse and sexual minority individuals and the factors that can help mediate the negative effects of stigma and prejudice.

Understanding Gender vs. Sexuality

To understand the difference between gender vs. sexuality, it's helpful to know what each term means.

- Gender is socially constructed and one's innermost concept of themselves as a man, woman, and/or nonbinary person. People define their gender identity in a variety of deeply personal ways that can include man or woman, but can also extend to identities such as agender, genderfluid , gender nonconforming , and a variety of others .

- Sexuality refers to who a person is attracted to and can include a plethora of orientations. While being gay, heterosexual, and bisexual are perhaps the most well-known sexual orientations, there are many others , such as asexual and pansexual .

The American Psychological Association (APA) defines gender identity as "a person’s deeply felt, inherent sense of being a boy, a man, or male; a girl, a woman, or female; or an alternative gender, which may or may not correspond to a person’s sex assigned at birth."

Gender identity is personal and an inherent part of an individual's sense of self. While gender is often presented as a binary that only includes men and women, in reality, gender is a spectrum and people can define their gender in a variety of ways, including as a combination of woman and man , a completely separate gender, or as no gender at all.

The four types of gender applied to living and nonliving things are masculine, feminine, neuter, and common.

Gender Identity vs. Gender Expression

Gender identity is internal and may not always be obvious to the outside world. That's because gender expression —the way one presents themselves through their external appearance and behavior with things like clothes, hairstyles, voice, and body language—may or may not conform to their gender identity.

Gender Identity vs. Sex

The terms sex and gender are often used interchangeably, and people often assume that the sex one is assigned at birth dictates the gender one is. In reality, though, gender identity and sex refer to different things.

While gender identity refers to how one defines themselves, sex is biological and dictated by one's anatomy, hormones, and chromosomes.

Just like gender identity, sex is a continuum that isn't limited to male or female, as people can also be born intersex , meaning their bodies aren't biologically male or female.

What Is Sexuality?

Sexuality is another word for sexual orientation. The APA defines sexual orientation as "a component of identity that includes a person's sexual or emotional attraction to another person and the behavior that may result from this attraction.

It's important to recognize that sexual and emotional attraction may not always match for asexual and aromantic people. Someone may be sexually attracted to one gender but experience no romantic attraction, whereas they may be romantically attracted to another gender but not want to engage in sexual acts.

Sexual Fluidity

Sexual orientation can change at any point during one's lifetime. In particular, as one ages and gets to know themselves and their preferences better, it may allow them to realize who they are attracted to, leading to the evolution of their sexuality. In fact, for some people, sexuality is fluid throughout their lives.

Impact of Discrimination Based on Gender and Sexuality

Unfortunately, transgender people or those whose sexual orientation is something other than heterosexual often encounter discrimination and prejudice. In the past few decades, both gender identity and sexual orientation have become political flashpoints.

A case revolving around whether people who were not heterosexual had the right to marry went all the way to the Supreme Court and the judges' ruling led to marriage equality. And many states have passed or are debating laws about issues involving transgender people, such as whether to prevent transgender men and women from using the bathroom that matches their gender identity.

The fact that issues surrounding the rights of gender-diverse and sexual minority people are up for debate contributes to a climate where discrimination is still common against anyone who isn't straight and cisgender . Research shows gender diverse and sexual minority individuals suffer from physical and psychological abuse, bullying, and persecution in a variety of contexts including school, the workplace, and health care.

People can become preoccupied with an individual's gender expression or sexual orientation if it doesn't conform to social norms and they may make their lack of support clear by doing things like using incorrect pronouns to refer to the individual.

In fact, a 2019 report of the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer ( LGBTQ ) youth in American schools, found that over half of LGBTQ+ students were verbally harassed and that over one-fifth were physically harassed due to their sexual orientation or gender expression.

This kind of prejudice and discrimination puts gender-diverse and sexual minority individuals at an increased risk of mental health issues including depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and suicide. On the other hand, an individual's journey to determining their sexuality or gender identity is personal. Suppressing one's true gender or sexual identity can lead to mental health issues as well.

Studies have shown that the mental distress triggered by discrimination can be mediated by things like social and familial support, contact with other sexual minorities or others who are gender diverse, and expectations of acceptance.

Moreover, LGBTQ students in schools with gay-straight alliances, LGBTQ-inclusive curriculums, and supportive educators felt safer and experienced a greater sense of belonging at school.

Both gender identity and sexual orientation are important to parts of a person's overall identity. Yet, in each case, social constructs surrounding gender and sexuality continue to result in prejudices that negatively impact gender-diverse and sexual minority individuals. This may be one reason these constructs continue to be conflated.

It is important that people recognize that for individuals, gender and sexuality are not inherently linked and that assumptions should never be made about one's sexual orientation based on gender or vice versa. Instead, people need to feel free to explore and define their gender identity and sexual orientation in the way that feels best to them. In doing so, they can be the truest version of themselves.

American Psychological Association Divisions 16 and 44. Key Terms And Concepts In Understanding Gender Diversity And Sexual Orientation Among Students . 2015.

Human Rights Campaign. Glossary of Terms .

Morris BJ. History of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Social Movements . American Psychological Association. 2009.

Adams C. The difference between sexual orientation and gender identity . CBS News. 2017.

GLSEN. The 2019 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth in Our Nation's School: Executive Summary . 2020.

Moleiro C, Pinto N. Sexual orientation and gender identity: Review of concepts, controversies and their relation to psychopathology classification systems . Front Psychol . 2015;6. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01511

By Cynthia Vinney, PhD Cynthia Vinney, PhD is an expert in media psychology and a published scholar whose work has been published in peer-reviewed psychology journals.

Gender Identity Essay

Introduction, interaction between hormones and behavior, current arguments on sexual identity, biological influences on gender identity and sexual differentiation, environmental influences.

Gender refers to the state of being either male or female, which is distinguished by factors such as gender roles, social and economic status, perceptions, and ideals and values (Lee, 2005). Gender has been described as a psycho-sociocultural aspect. In contrast, sex is a biological concept that is determined by factors such as hormones and genetic make-up (Lee, 2005). Gender is also understood as evaluation of behavior based on individual perceptions and societal expectations.

Gender identity is defined as personal concepts and perceptions of self that are based on gender (Lee, 2005). This paper will explore determination of gender identity based on connections between hormones and behavior. In addition, it will scrutinize how biological and environmental factors affect gender identity. It will also explore current arguments on gender identity.

Research studies have revealed that hormones have great influence on behavior. For example, hormonal processes contribute towards hostile and aggressive behaviors (Lee, 2005). Studies associate certain behaviors with certain hormones. For example, testosterone is associated with aggressiveness. Studies on effect of hormones on behavior are based on the net effect of hormones on emotions. They cause varying level of moods or behavior depending on their concentrations.

For example, in adults, estrogen causes positive moods while lack of estrogen causes depressive moods (Lee, 2005). This is the same effect testosterone has on moods and behaviors. Some hormones affect behavior directly while others affect behavior indirectly. For example, hormones that determine body size affect behavior indirectly. Big-sized people are domineering and usually rough towards small-sized people. Abnormal activity of glands can also influence behavior directly.

Hormones respond by combining with specific cell receptors to form behavior. Puberty and prenatal periods are the most critical periods in human development that hormones have the greatest impact (Lee, 2005). During the prenatal period, any anomaly in production of hormones results in anomalies in gender identity.

For example, a study conducted on 25 androgenized girls found out that even though they were raised as girls, they exhibited masculine attitudes, sexuality, and grooming (Lee, 2005). After the development of Money’s theories on gender identity, several studies followed that established connections between gender identity and environmental factors.

Current arguments on sexual identify claim that is mainly determined by biological factors rather than environmental factors (Lee, 2005). This argument is based on lifestyles such as homosexuality and lesbianism. These arguments claim that people who adopt these lifestyles were born that way because of interaction between different biological factors.

Other arguments claim that such lifestyles can be caused by environmental factors. If an individual gets exposure to one of these lifestyles early in childhood, then he/she would adopt a similar lifestyle owing to influence of the environment (Lee, 2005). However, research has established that these lifestyles are mainly caused by influence of biological factors and further augmented by environmental factors.

The influence of biological factors on gender identity can be explained by considering functions of hormones and cerebral lateralization of the brain (Lee, 2005).

Gender is determined before birth by biological factors. Studies have revealed that brain lateralization and hormonal functions contribute in determination of gender. Males and females contain sexual and reproductive hormones in varying quantities. This is observed from childhood through adulthood although in each stage of development certain changes take place. During puberty, gender characteristics become more pronounced because attraction towards the opposite sex develops (Lee, 2005).

Brain lateralization follows different systems of development in males and females. For example, in females the left side of the brain is more developed compared to males whose right side is more developed. Variation in brain lateralization accounts for high performance by males in sciences and mathematics and better performance in languages by girls.

The first environmental child experiences after birth is the family (Lee, 2005). Mothers dress newborn babies in clothes that depict their gender. As they go through different development stages, children learn to discern their gender from how they are treated. Fathers influence boys and mothers influence girls.

Absence of a father in the family affects discernment of gender identity significantly. Other environments outside the family also play critical roles. Television, music, movies, and books depict different genders in different ways (Lee, 2005). Children pick gender cues from these environments and incorporate them in their gender identity discernment processes.

Environmental factors have the greatest influence on gender identity compared to other factors. Environments such as family and classrooms have the greater influence on gender identity compared to biological and psychological factors (Lee, 2005).

Gender differs from sex in that it is psycho-sociocultural while sex is biological. Aspects such as social and economic status, roles, and personal perceptions determine gender. Gender identity is influenced and determined by biological, psychological, and environmental factors.

The environment has the greatest influence compared to other factors. From childhood to adulthood, people interact with different environments that influence how they discern and define gender identity. According to the foregoing discussion, nurture has greater influence on gender identity than nature. Each of the three factors plays a different role in determination of gender identity.

Lee, J. (2005). Focus on Gender Identity . New York: Nova Publishers.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, November 27). Gender Identity. https://ivypanda.com/essays/gender-identity-2/

"Gender Identity." IvyPanda , 27 Nov. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/gender-identity-2/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Gender Identity'. 27 November.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Gender Identity." November 27, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/gender-identity-2/.

1. IvyPanda . "Gender Identity." November 27, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/gender-identity-2/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Gender Identity." November 27, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/gender-identity-2/.

- Cognitive Neuroscience: Methods and Studies

- Neuroplasticity Principle Interference (Melodic Intonation Therapy)

- The Hemispheres Adaptability to Function Independently

- Addictions and Emotions in Biopsychology

- Health Care Statistics on Ambidextrous Children

- Hormones and Behaviors in Determination of Gender Identity

- Endocrinology: Regulation of Growth Hormone

- Hormone Replacement Therapy

- Research and Report on Hormone Use in US Meats

- Different Aspects of Gender Identity

- Effects of Technology and Globalization on Gender Identity

- Identity: Acting out Culture

- Social Survey: Men and Women on Sexual Intent

- Stereotypes and Their Effects

- “Stay Hungry, Stay Foolish” by Steve Jobs

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Neurobiology of gender identity and sexual orientation

Sexual identity and sexual orientation are independent components of a person’s sexual identity. These dimensions are most often in harmony with each other and with an individual’s genital sex, although not always. The present review discusses the relationship of sexual identity and sexual orientation to prenatal factors that act to shape the development of the brain and the expression of sexual behaviours in animals and humans. One major influence discussed relates to organisational effects that the early hormone environment exerts on both gender identity and sexual orientation. Evidence that gender identity and sexual orientation are masculinised by prenatal exposure to testosterone and feminised in it absence is drawn from basic research in animals, correlations of biometric indices of androgen exposure and studies of clinical conditions associated with disorders in sexual development. There are, however, important exceptions to this theory that have yet to be resolved. Family and twin studies indicate that genes play a role, although no specific candidate genes have been identified. Evidence that relates to the number of older brothers implicates maternal immune responses as a contributing factor for male sexual orientation. It remains speculative how these influences might relate to each other and interact with postnatal socialisation. Nonetheless, despite the many challenges to research in this area, existing empirical evidence makes it clear that there is a significant biological contribution to the development of an individual’s sexual identity and sexual orientation.

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Gender identity and sexual orientation are fundamental independent characteristics of an individual’s sexual identity. 1 Gender identity refers to a person’s innermost concept of self as male, female or something else and can be the same or different from one’s physical sex. 2 Sexual orientation refers to an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic and/or sexual attractions to men, women or both sexes. 3 Both gender identity and sexual orientation are characterised by obvious sex differences. Most genetic females identify as such and are attracted to males (ie, androphilic) and most genetic males identify as males and are attracted to females (ie, gynophilic). The existence of these dramatic sex differences suggest that gonadal hormones, particularly testosterone, might be involved, given that testosterone plays an important role in the development of most, behavioural sex differences in other species. Here, a review is provided of the evidence that testosterone influences human gender identity and sexual orientation. The review begins by summarising the available information on sex hormones and brain development in other species that forms the underpinnings of the hypothesis suggesting that these human behaviours are programmed by the prenatal hormone environment, and it will also consider contributions from genes. This is followed by a critical evaluation of the evidence in humans and relevant animal models that relates sexual identity and sexual orientation to the influences that genes and hormones have over brain development.

2 |. HORMONES, GENES AND SEXUAL DIFFERENTIATION OF THE BRAIN AND BEHAVIOUR

The empirical basis for hypothesising that gonadal hormones influence gender identity and sexual orientation is based on animal experiments involving manipulations of hormones during prenatal and early neonatal development. It is accepted dogma that testes develop from the embryonic gonad under the influence of a cascade of genes that begins with the expression of the sex-determining gene SRY on the Y chromosome. 4 , 5 Before this time, the embryonic gonad is “indifferent”, meaning that it has the potential to develop into either a testis or an ovary. Likewise, the early embryo has 2 systems of ducts associated with urogenital differentiation, Wolffian and Müllerian ducts, which are capable of developing into the male and female tubular reproductive tracts, respectively. Once the testes develop, they begin producing 2 hormones, testosterone and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH). In rats, this occurs around day 16–17 of gestation, whereas, in humans, it occurs at about 7–8 weeks of gestation. 6 Testosterone and one of its derivatives, dihydrotestosterone, induce the differentiation of other organs in the male reproductive system, whereas AMH causes the degeneration of the Müllerian ducts. Female ovaries develop under the influence of a competing set of genes that are influenced by expression of DAX1 on the X chromosome and act antagonistically to SRY. The female reproductive tract in the embryo develops in the absence of androgens and later matures under the influence hormones produced by the ovary, in particular oestradiol.

Analogous processes occur during early development for sexual differentiation of the mammalian brain and behaviour. According to the classical or organisational theory, 7 , 8 prenatal and neonatal exposure to testosterone causes male-typical development (masculinisation), whereas female-typical development (feminisation) occurs in the relative absence of testosterone. Masculinisation involves permanent neural changes induced by steroid hormones and differs from the more transient activational effects observed after puberty. These effects typically occur during a brief critical period in development when the brain is most sensitive to testosterone or its metabolite oestradiol. In rats, the formation of oestradiol in the brain by aromatisation of circulating testosterone is the most important mechanism for the masculinisation of the brain; 9 however, as shown below, testosterone probably acts directly without conversion to oestradiol to influence human gender identity and sexual orientation. The times when testosterone triggers brain sexual differentiation in different species correspond to periods when testosterone is most elevated in males compared to females. In rodents and other altricial species, this occurs largely during the first 5 days after birth, whereas, in humans, the elevation in testosterone occurs between months 2 and 6 of pregnancy and then again from 1 to 3 months postnatally. 6 During these times, testosterone levels in the circulation are much higher in males than in females. These foetal and neonatal peaks of testosterone, together with functional steroid receptor activity, are considered to program the male brain both phenotypically and neurologically. In animal models, programming or organising actions are linked to direct effects on the various aspects of neural development that influence cell survival, neuronal connectivity and neurochemical specification. 10 Many of these effects occur well after the initial hormone exposure and have recently been linked to epigenetic mechanisms. 11

The regional brain differences that result from the interaction between hormones and developing brain cells are assumed to be the major basis of sex differences in a wide spectrum of adult behaviours, such as sexual behaviour, aggression and cognition, as well as gender identity and sexual orientation. Factors that interfere with the interactions between hormones and the developing brain systems during gestation may permanently influence later behaviour. Studies in sheep and primates have clearly demonstrated that sexual differentiation of the genitals takes places earlier in development and is separate from sexual differentiation of the brain and behaviour. 12 , 13 In humans, the genitals differentiate in the first trimester of pregnancy, whereas brain differentiation is considered to start in the second trimester. Usually, the processes are coordinated and the sex of the genitals and brain correspond. However, it is hypothetically possible that, in rare cases, these events could be influenced independently of each other and result in people who identify with a gender different from their physical sex. A similar reasoning has been invoked to explain the role of prenatal hormones on sexual orientation.

Although the role of gonadal steroids in the sexual differentiation of reproductive brain function and behaviour is undeniable, males and females also carry a different complement of genes encoded on their sex chromosomes that also influence sexual differentiation of the brain. 14 – 16 As will be discussed, family and twin studies suggest that there is a genetic component to gender identity and sexual orientation at least in some individuals. However, the nature of any genetic predisposition is unknown. The genetic component could be coding directly for these traits or, alternatively, could influence hormonal mechanisms by determining levels of hormones, receptors or enzymes. Genetic factors and hormones could also make separate yet complementary or antagonistic contributions. It should be noted that, although the early hormone environment appears to influence gender identity and sexual orientation, hormone levels in adulthood do not. There are no reports indicating that androgen levels differ as a function of gender identity or sexual orientation or that treatment with exogenous hormones alters these traits in either sex.

3 |. GENDER IDENTITY

The establishment of gender identity is a complex phenomenon and the diversity of gender expression argues against a simple or unitary explanation. For this reason, the extent to which it is determined by social vs biological (ie, genes and hormones) factors continues to be debated vigorously. 17 The biological basis of gender identity cannot be modelled in animals and is best studied in people who identify with a gender that is different from the sex of their genitals, in particular transsexual people. Several extensive reviews by Dick Swaab and coworkers elaborate the current evidence for an array of prenatal factors that influence gender identity, including genes and hormones. 18 – 20

3.1 |. Genes

Evidence of a genetic contribution to transsexuality is very limited. 21 There are few reports of family and twin studies of transsexuals but none offer clear support for the involvement of genetic factors. 22 – 24 Polymorphisms in sex hormone-related genes for synthetic enzymes and receptors have been studied based on the assumption that these may be involved in gender identity development. An increased incidence of an A2 allele polymorphism for CYP17A1 (ie, 17ɑ-hydroxylase/17, 20 lyase, the enzyme catalysing testosterone synthesis) was found in female-to-male (FtM) but not in male-to-female (MtF) transsexuals. 25 No associations were found between a 5ɑ-reductase (ie, the enzyme converting testosterone to the more potent dihydrotestosterone) gene polymorphism in either MtF or FtM transsexuals. 26 There are also conflicting reports of associations between polymorphisms in the androgen receptor, oestrogen receptor β and CYP19 (ie, aromatase, the enzymes catalysing oestradiol synthesis). 27 – 29 A recent study using deep sequencing detected three low allele frequency gene mutants (i.e., FBXO38 [chr5:147774428; T>G], SMOC2 [chr6:169051385; A>G] and TDRP [chr8:442616; A>G]) between monozygotic twins discordant for gender dysphoria. 30 Further investigations including functional analysis and epidemiological analysis are needed to confirm the significance of the mutations found in this study. Overall, these genetic studies are inconclusive and a role for genes in gender identity remains unsettled.

3.2 |. Hormones

The evidence that prenatal hormones affect the development of gender identity is stronger but far from proven. One indication that exposure to prenatal testosterone has permanent effects on gender identity comes from the unfortunate case of David Reimer. 31 As an infant, Reimer underwent a faulty circumcision and was surgically reassigned, given hormone treatments and raised as a girl. He was never happy living as a girl and, years later, when he found out what happened to him, he transitioned to living as a man. However, for at least the first 8 months of life, this child was reared as a boy and it is not possible to know what impact rearing had on his dissatisfaction with a female sex assignment. 1 Other clinical studies have reported that male gender identity emerges in some XY children born with poorly formed or ambiguous genitals as a result of cloacal exstrophy, 5ɑ-reductase or 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency and raised as girls from birth. 32 , 33 All of these individuals were exposed to testosterone prenatally emphasising a potential role for androgens in gender development and raising doubts that children are psychosexually neutral at birth. 20 On the other hand, XY individuals born with an androgen receptor mutation causing complete androgen insensitivity are phenotypically female, identify as female and are most often androphilic, indicating that androgens act directly on the brain without the need for aromatisation to oestradiol. 34

3.3 |. Neuroanatomy

Further evidence that the organisational hormone theory applies to development of gender identity comes from observations that structural and functional brain characteristics are more similar between transgender people and control subjects with the same gender identity than between individuals sharing their biological sex. This includes local differences in the number of neurones and volume of subcortical nuclei such as the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, 35 , 36 numbers of kisspeptin and neurokinin B neurones in the infundibulum, 37 , 38 structural differences of gray 39 , 40 and white matter microstructure, 41 – 43 neural responses to sexually-relevant odours 44 , 45 and visuospatial functioning. 46 However, in some cases, the interpretation of these studies is complicated by hormone treatments, small sample sizes and a failure to disentangle correlates of sexual orientation from gender identity. 47 The fact that these differences extend beyond brain areas and circuits classically associated with sexual and endocrine functions raises the possibility that transsexuality is also associated with changes in cerebral networks involved in self-perception.

4 |. SEXUAL ORIENTATION

Research over several decades has demonstrated that sexual orientation ranges along a continuum, from exclusive attraction to the opposite sex to exclusive attraction to the same sex. 48 However, sexual orientation is usually discussed in terms of 3 categories: heterosexual (having emotional, romantic or sexual attractions to members of the other sex), homosexual (having emotional, romantic or sexual attractions to members of one’s own sex) and bisexual (having emotional, romantic or sexual attractions to both men and women). Most people experience little or no sense of choice about their sexual orientation. There is no scientifically convincing research to show that therapy aimed at changing sexual orientation (ie, reparative or conversion therapy) is safe or effective. 3 The origin of sexual orientation is far from being understood, although there is no proof that it is affected by social factors after birth. On the other hand, a large amount of empirical data suggests that genes and hormones are important regulators of sexual orientation. 49 – 51 Useful animal models and experimental paradigms in animals have helped frame questions and propose hypotheses relevant to human sexual orientation.

4.1 |. Animal studies

Sexual partner preference is one of the most sexually dimorphic behaviours observed in animals and humans. Typically, males choose to mate with females and females choose to mate with males. Sexual partner preferences can be studied in animals by using sexual partner preference tests and recording the amount of time spent alone or interacting with the same or opposite sex stimulus animal. Although imperfect, tests of sexual partner preference or mate choice in animals have been used to model human sexual orientation. As reviewed comprehensively by Adkins-Regan 52 and Henley et al, 53 studies demonstrate that perinatal sex steroids have a large impact on organising mate choice in several species of animals, including birds, mice, rats, hamsters, ferrets and pigs. In particular, perinatal exposure to testosterone or its metabolite oestradiol programs male-typical (ie, gynophilic) partner preferences and neonatal deprivation of testosterone attenuates the preference that adult males show typically. In the absence of high concentrations of sex steroid levels or receptor-mediated activity during development, a female-typical (ie, androphilic) sexual preference for male sex partners develops.

Sexually dimorphic neural groups in the medial preoptic area of rats and ferrets have been associated with sexual partner preferences. In male rats, a positive correlation was demonstrated between the volume of the sexual dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area (SDN) and the animal’s preference for a receptive female, 54 although this was not replicated in a recent study. 55 Furthermore, in both rats and ferrets, destruction of the SDN caused males to show either neutral or androphilic preferences. 56

Naturally occurring same-sex interactions involving genital arousal have been reported in hundreds of animal species; however, they often appear to be motivated by purposes other than sex and may serve to facilitate other social goals. 57 , 58 Exclusive and enduring same-sex orientation is, however, extremely rare among animals and has only been documented conclusively and studied systematically in certain breeds of domestic sheep. 59 , 60 Approximately 6% to 8% of Western-breed domestic rams choose to exclusively court and mount other rams, but never ewes, when given a choice. No social factors, such as the general practice of rearing in same sex groups or an animal’s dominance rank, were found to affect sexual partner preferences in rams. Consistent with the organisational theory of sexual differentiation, sheep have an ovine sexually dimorphic preoptic nucleus (oSDN) that is larger and contains more neurones in female-oriented (gynophilic) rams than in male-oriented rams (androphilic) and ewes (androphilic). 61 Thus, morphological features of the oSDN correlate with a sheep’s sexual partner preference. The oSDN already exists and is larger in males than in females before sheep are born, suggesting that it could play a causal role in behaviour. 62 The oSDN differentiates under the influence of prenatal testosterone after the male genitals develop, but is unaffected by hormone treatment in adulthood. 63 Appropriately timed experimental exposure of female lamb foetuses to testosterone can alter oSDN size independently of genetic and phenotypic sex. 13 However, males appear to be resistant to suppression of the action of androgen during gestation because the foetal hypothalamic-pituitary-axis is active in the second trimester (term pregnancy approximately 150 days) and mitigates against changes in circulating testosterone that could disrupt brain masculinisation. 64 These data suggest that, in sheep, brain sexual differentiation is initiated during gestation by central mechanisms acting through gonadotrophin-releasing hormone neurones to stimulate and maintain the foetal testicular testosterone synthesis needed to masculinise the oSDN and behaviour. More research is required to understand the parameters of oSDN development and to causally relate its function to sexual partner preferences in sheep. Nonetheless, when considered together, the body of animal research strongly indicates that male-typical partner preferences are controlled at least in part by the neural groups in the preoptic area that differentiate under the influence of pre- and perinatal sex steroids.

4.2 |. Human studies

4.2.1 |. genes.

Evidence from family and twin studies suggests that there is a moderate genetic component to sexual orientation. 50 One recent study estimated that approximately 40% of the variance in sexual orientation in men is controlled by genes, whereas, in women, the estimate is approximately 20%. 65 In 1993, Hamer et al 66 published the first genetic linkage study that suggested a specific stretch of the X chromosome called Xq28 holds a gene or genes that predispose a man to being homosexual. These results were consistent with the observations that, when there is male homosexuality in a family, there is a greater probability of homosexual males on the mother’s side of the family than on the father’s side. The study was criticised for containing only 38 pairs of gay brothers and the original finding was not replicated by an independent group. 67 Larger genome-wide scans support an association with Xq28 and also found associations with chromosome 7 and 8, 68 , 69 although this has also been disputed. 70 Scientists at the personal genomics company 23andme performed the only genome-wide association study of sexual orientation that looked within the general population. 71 The results were presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Human Genetics in 2012, although they have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal. Although no genetic loci reaching genome-wide significance for homosexuality among men or women, the genetic marker closest to significance was located in the same region of chromosome 8 in men as that implicated in linkage studies. Other molecular genetic evidence suggests that epigenetic factors could influence male sexual orientation, although this has yet to be demonstrated. 72 , 73

4.2.2 |. Hormones

The leading biological theory of sexual orientation in humans, as in animals, draws on the application of the organisational theory of sexual differentiation. However, this theory cannot be directly tested because it is not ethical to experimentally administer hormones to pregnant women and test their effect on the sexual orientation of their children. Naturally occurring and iatrogenic disorders of sex development that involve dramatic alterations in hormone action or exposure lend some support to a role for prenatal hormones, although these cases are extremely rare and often difficult to interpret. 74 Despite these limitations, two clinical conditions are presented briefly that lend some support for the organisational theory. More comprehensive presentations of the clinical evidence on this topic can be found in several excellent reviews. 74 – 76

Women born with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and exposed to abnormally high levels of androgens in utero show masculinised genitals, play behaviour and aggression. 74 , 77 They also are less likely to be exclusively heterosexual and report more same-sex activity than unaffected women, which suggests that typical female sexual development is disrupted. Although it appears plausible that these behavioural traits are mediated through effects of elevated androgens on the brain, it is also possible that the sexuality of CAH women may have also been impacted by the physical and psychological consequences of living with genital anomalies or more nuanced effects of socialisation. 78 There is also evidence for prenatal androgen effects on sexual orientation in XY individuals born with cloacal exstrophy. It was reported originally that a significant number of these individuals eventually adopt a male gender identity even though they had been surgically reassigned and raised as girls. Follow-up studies found that almost all of them were attracted to females (i.e. gynophilic). 33 , 50 The outcomes reported for both of these conditions are consistent with the idea that prenatal testosterone programs male-typical sexual orientation in adults. However, effects on sexual orientation were not observed across the board in all individuals with these conditions, indicating that hormones cannot be the only factor involved.

4.2.3 |. Neuroanatomy

Additional evidence that supports a prenatal organisational theory of sexual orientation is derived from the study of anatomical and physiological traits that are known to be sexually dimorphic in humans and are shown to be similar between individuals sharing the same sexual attraction. Neuroanatomical differences based on sexual orientation in human males have been found. LeVay 79 reported that the third interstitial nucleus of the anterior hypothalamus (INAH3) in homosexual men is smaller than in heterosexual men and has a similar size in homosexual men and women. Based on its position and cytoarchitecture, INAH3 resembles the sheep oSDN, which has similar differences in volume and cell density correlated with sexual partner preference. This similarity suggests that a relevant neural circuit is conserved between species. A recent review and meta-analysis of neuroimaging data from human subjects with diverse sexual interests during sexual stimulation also support the conclusion that elements of the anterior and preoptic area of the hypothalamus is part of a core neural circuit for sexual preferences. 80

Other neural and somatic biomarkers of prenatal androgen exposure have also been investigated. McFadden 81 reported that functional properties of the inner ear, measured as otoacoustic emissions (OAEs), and of the auditory brain circuits, measured as auditory evoked potentials (AEPs), differ between the sexes and between heterosexual and homosexual individuals. OAEs and AEPs are usually stronger in heterosexual women than in heterosexual men and are masculinised in lesbians, consistent with the prenatal hormone theory. However, OAEs were not different in homosexual males and AEPs appear to be hyper-masculinised. The second digit to fourth digit (2D:4D) ratio, which is the length of the second digit (index finger) relative to that of the fourth digit (ring finger), is another measure that has been used as a proxy for prenatal androgen exposure. The 2D:4D ratio is generally smaller in men than in women, 82 , 83 although the validity of this measure as a marker influenced by only prenatal androgen exposure has been questioned. 84 Nonetheless, numerous studies have reported that the 2D:4D ratio is also on average smaller in lesbians than in hetero-sexual women, a finding that has been extensively replicated 85 and suggests the testosterone plays a role in female sexual orientation. Similar to OAEs, digit ratios do not appear to be feminised in homosexual men and, similar to AEPs, may even be hyper-masculinised. The lack of evidence for reduced androgen exposure in homosexual men (based on OAEs, AEPs and digit ratios) led Breedlove 85 to speculate that there may be as yet undiscovered brain-specific reductions in androgen responses in male foetuses that grow up to be homosexual. No variations in the human androgen receptor or the aromatase gene were found that relate to variations in sexual orientation. 86 , 87 However, Balthazart and Court 88 provided suggestions for other genes located in the Xq28 region of the X-chromosome that should be explored and it remains possible that expression levels of steroid hormone response pathway genes could be regulated epigenetically (11).

4.2.4 |. Maternal immune response

Homosexual men have, on average, a greater number of older brothers than do heterosexual men, a well-known finding that has been called the fraternal birth order (FBO) effect. 89 Accordingly, the incidence of homosexuality increases by approximately 33% with each older brother. 90 The FBO effect has been confirmed many times, including by independent investigators and in non-Western sample populations. The leading hypothesis to explain this phenomenon posits that some mothers develop antibodies against a Y-linked factor important for male brain development, and that the response increases incrementally with each male gestation leading, in turn, to the alteration of brain structures underlying sexual orientation in later-born boys. In support of the immune hypothesis, Bogaert et al 91 demonstrated recently that mothers of homosexual sons, particularly those with older brothers, have higher antibody titers to neurolignin 4 (NLGN4Y), an extracellular protein involved in synaptic functioning and presumed to play a role in foetal brain development.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

The data summarised in the present review suggest that both gender identity and sexual orientation are significantly influenced by events occurring during the early developmental period when the brain is differentiating under the influence of gonadal steroid hormones, genes and maternal factors. However, our current understanding of these factors is far from complete and the results are not always consistent. Animal studies form both the theoretical underpinnings of the prenatal hormone hypothesis and provide causal evidence for the effect of prenatal hormones on sexual orientation as modelled by tests of sexual partner preferences, although they do not translate to gender identity.

Sexual differentiation of the genitals takes place before sexual differentiation of the brain, making it possible that they are not always congruent. Structural and functional differences of hypothalamic nuclei and other brain areas differ in relation to sexual identity and sexual orientation, indicating that these traits develop independently. This may be a result of differing hormone sensitivities and/or separate critical periods, although this remains to be explored. Most findings are consistent with a predisposing influence of hormones or genes, rather than a determining influence. For example, only some people exposed to atypical hormone environments prenatally show altered gender identity or sexual orientation, whereas many do not. Family and twin studies indicate that genes play a role, but no specific candidate genes have been identified. Evidence that relates to the number of older brothers implicates maternal immune responses as a contributing factor for male sexual orientation. All of these mechanisms rely on correlations and our current understanding suffers from many limitations in the data, such as a reliance on retrospective clinical studies of individuals with rare conditions, small study populations sizes, biases in recruiting subjects, too much reliance on studies of male homosexuals, and the assumption that sexuality is easily categorised and binary. Moreover, none of the biological factors identified so far can explain all of the variances in sexual identity or orientation, nor is it known whether or how these factors may interact. Despite these limitations, the existing empirical evidence makes it clear that there is a significant biological contribution to the development of an individual’s sexual identity and sexual orientation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank Charles Estill, Robert Shapiro and Fred Stormshak for their thoughtful comments on this review. This work was supported by NIH R01OD011047.

Funding information

This work was supported by NIH R01OD011047 (CER)

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

15.4: Development of Gender Identity

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 24690

- Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson

- College of the Canyons via College of the Canyons

From birth, children are assigned a gender and are socialized to conform to certain gender roles based on their biological sex. “ Sex ,” refers to physical or physiological differences between males, females, and intersex persons, including both their primary and secondary sex characteristics. “ Gender ,” on the other hand, refers to social or cultural distinctions associated with a given sex.

When babies are born, they are assigned a gender based on their biological sex—male babies are assigned as boys, female babies are assigned as girls, and intersex babies are born with sex characteristics that do not fit the typical definitions for male or female bodies, and are usually relegated into one gender category or another. Scholars generally regard gender as a social construct , meaning that it doesn’t exist naturally but is instead a concept that is created by cultural and societal norms. From birth, children are socialized to conform to certain gender roles based on their biological sex and the gender to which they are assigned.22

A person’s subjective experience of their own gender and how it develops, or gender identity , is a topic of much debate. It is the extent to which one identifies with a particular gender; it is a person’s individual sense and subjective experience of being a man, a woman, or other gender. It is often shaped early in life and consists primarily of the acceptance (or non-acceptance) of one’s membership into a gender category. In most societies, there is a basic division between gender attributes assigned to males and females. In all societies, however, some individuals do not identify with some (or all) of the aspects of gender that are assigned to their biological sex.

Those that identify with the gender that corresponds to the sex assigned to them at birth (for example, they are assigned female at birth and continue to identify as a girl, and later a woman) are called cisgender . In many Western cultures, individuals who identify with a gender that is different from their biological sex (for example, they are assigned female at birth but feel inwardly that they are a boy or a gender other than a girl) are called transgender . Some transgender individuals, if they have access to resources and medical care, choose to alter their bodies through medical interventions such as surgery and hormonal therapy so that their physical being is better aligned with their gender identity.

Recent terms such as “genderqueer,” “genderfluid,” “gender variant,” “androgynous,” “agender,” and “gender nonconforming” are used by individuals who do not identify within the gender binary as either a man or a woman. Instead they identify as existing somewhere along a spectrum or continuum of genders, or outside of the spectrum altogether, often in a way that is continuously evolving.

The Gender Continuum

Viewing gender as a continuum allows us to perceive the rich diversity of genders, from trans-and cisgender to gender queer and agender. Most Western societies operate on the idea that gender is a binary , that there are essentially only two genders (men and women) based on two sexes (male and female), and that everyone must fit one or the other. This social dichotomy enforces conformance to the ideals of masculinity and femininity in all aspects of gender and sex—gender identity, gender expression, and biological sex.

According to supporters of queer theory , gender identity is not a rigid or static identity but can continue to evolve and change over time. Queer theory developed in response to the perceived limitations of the way in which identities are thought to become consolidated or stabilized (for instance, gay or straight) and theorists constructed queerness in an attempt to resist this. In this way, the theory attempts to maintain a critique rather than define a specific identity. While “queer” defies a simple definition, the term is often used to convey an identity that is not rigidly developed but is instead fluid and changing. 24

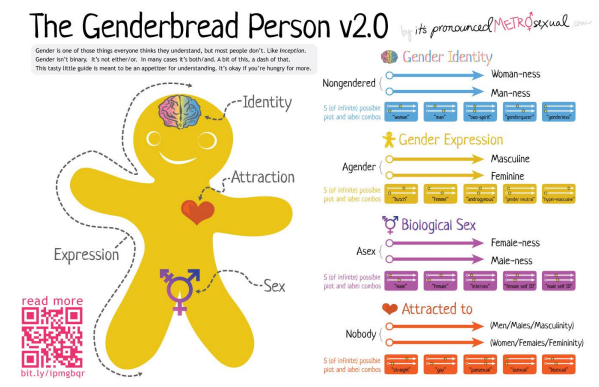

The Genderbread Person

In 2012, Sam Killerman created the Genderbread Person as an infographic to break down gender identity, gender expression, biological sex, and sexual orientation. 25 In 2018, he updated it to version 2.0 to be more accurate, and inclusive. 26

Gender Pronouns

Pronouns are a part of language used to refer to someone or something without using proper nouns. In standard English, some singular third-person pronouns are "he" and "she," which are usually seen as gender-specific pronouns, referring to a man and a woman, respectively. A gender-neutral pronoun or gender-inclusive pronoun is one that gives no implications about gender, and could be used for someone of any gender.

Some languages only have gender-neutral pronouns, whereas other languages have difficulty establishing any that aren't gender-specific. People with non-binary gender identities often choose new third-person pronouns for themselves as part of their transition. They often choose gender-neutral pronouns so that others won't see them as female or male. 28

Here is a table based on the Rainbow Coalition of Yellowknife’s Handy Guide to Pronouns:

Factors that Influence Gender Identity

Although the formation of gender identity is not completely understood, many factors have been suggested as influencing its development. Biological factors that may influence gender identity include pre- and post-natal hormone levels and genetic makeup. Social factors include ideas regarding gender roles conveyed by family, authority figures, mass media, and other influential people in a child’s life. According to social-learning theory, children develop their gender identity through observing and imitating the gender-linked behaviors of others; they are then “rewarded” for imitating the behaviors of people of the same gender and “punished” for imitating the behaviors of another gender. For example, male children will often be rewarded for imitating their father’s love of baseball but punished or redirected in some way if they imitate their older sister’s love of dolls. Children are shaped and molded by the people surrounding them, who they try to imitate and follow.

Gender Roles

The term “gender role” refers to society’s concept of how men and women are expected to act. As we grow, we learn how to behave from those around us. In this socialization process, children are introduced to certain roles that are typically linked to their biological sex. The term “gender role” refers to society’s concept of how men and women are expected to act and behave. Gender roles are based on norms, or standards, created by society. In American culture, masculine roles have traditionally been associated with strength, aggression, and dominance, while feminine roles have traditionally been associated with passivity, nurturing, and subordination.

Gender Socialization

The socialization process in which children learn these gender roles begins at birth. Today, our society is quick to outfit male infants in blue and girls in pink, even applying these color-coded gender labels while a baby is in the womb. It is interesting to note that these color associations with gender have not always been what they are today. Up until the beginning of the 20th century, pink was actually more associated with boys, while blue was more associated with girls—illustrating how socially constructed these associations really are.

Gender socialization occurs through four major agents: family, education, peer groups, and mass media. Each agent reinforces gender roles by creating and maintaining normative expectations for gender-specific behavior. Exposure also occurs through secondary agents, such as religion and the workplace. Repeated exposure to these agents over time leads people into a false sense that they are acting naturally based on their gender rather than following a socially constructed role.

Gender Stereotypes, Sexism, and Gender-Role Enforcement

The attitudes and expectations surrounding gender roles are not typically based on any inherent or natural gender differences, but on gender stereotypes , or oversimplified notions about the attitudes, traits, and behavior patterns of males and females. We engage in gender stereotyping when we do things like making the assumption that a teenage babysitter is female.

While it is somewhat acceptable for women to take on a narrow range of masculine characteristics without repercussions (such as dressing in traditionally male clothing), men are rarely able to take on more feminine characteristics (such as wearing skirts) without the risk of harassment or violence. This threat of punishment for stepping outside of gender norms is especially true for those who do not identify as male or female.

Gender stereotypes form the basis of sexism or the prejudiced beliefs that value males over females. Common forms of sexism in modern society include gender-role expectations, such as expecting women to be the caretakers of the household. Sexism also includes people’s expectations of how members of a gender group should behave. For example, girls and women are expected to be friendly, passive, and nurturing; when she behaves in an unfriendly or assertive manner, she may be disliked or perceived as aggressive because she has violated a gender role (Rudman, 1998). In contrast, a boy or man behaving in a similarly unfriendly or assertive way might be perceived as strong or even gain respect in some circumstances. 31

Contributors and Attributions

24. Boundless Psychology - Gender and Sexuality references Curation and Revision by Boundless Psychology, which is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

25. The Genderbread Person by Sam Killermann is in the public domain

26. The Genderbread Person v2.0 by Sam Killermann is in the public domain

28. Pronouns by Nonbinary Wiki is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

31. Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

5 Powerful Essays Advocating for Gender Equality

Gender equality – which becomes reality when all genders are treated fairly and allowed equal opportunities – is a complicated human rights issue for every country in the world. Recent statistics are sobering. According to the World Economic Forum, it will take 108 years to achieve gender parity . The biggest gaps are found in political empowerment and economics. Also, there are currently just six countries that give women and men equal legal work rights. Generally, women are only given ¾ of the rights given to men. To learn more about how gender equality is measured, how it affects both women and men, and what can be done, here are five essays making a fair point.

Take a free course on Gender Equality offered by top universities!

“Countries With Less Gender Equity Have More Women In STEM — Huh?” – Adam Mastroianni and Dakota McCoy

This essay from two Harvard PhD candidates (Mastroianni in psychology and McCoy in biology) takes a closer look at a recent study that showed that in countries with lower gender equity, more women are in STEM. The study’s researchers suggested that this is because women are actually especially interested in STEM fields, and because they are given more choice in Western countries, they go with different careers. Mastroianni and McCoy disagree.

They argue the research actually shows that cultural attitudes and discrimination are impacting women’s interests, and that bias and discrimination is present even in countries with better gender equality. The problem may lie in the Gender Gap Index (GGI), which tracks factors like wage disparity and government representation. To learn why there’s more women in STEM from countries with less gender equality, a more nuanced and complex approach is needed.

“Men’s health is better, too, in countries with more gender equality” – Liz Plank

When it comes to discussions about gender equality, it isn’t uncommon for someone in the room to say, “What about the men?” Achieving gender equality has been difficult because of the underlying belief that giving women more rights and freedom somehow takes rights away from men. The reality, however, is that gender equality is good for everyone. In Liz Plank’s essay, which is an adaption from her book For the Love of Men: A Vision for Mindful Masculinity, she explores how in Iceland, the #1 ranked country for gender equality, men live longer. Plank lays out the research for why this is, revealing that men who hold “traditional” ideas about masculinity are more likely to die by suicide and suffer worse health. Anxiety about being the only financial provider plays a big role in this, so in countries where women are allowed education and equal earning power, men don’t shoulder the burden alone.

Liz Plank is an author and award-winning journalist with Vox, where she works as a senior producer and political correspondent. In 2015, Forbes named her one of their “30 Under 30” in the Media category. She’s focused on feminist issues throughout her career.

“China’s #MeToo Moment” – Jiayang Fan

Some of the most visible examples of gender inequality and discrimination comes from “Me Too” stories. Women are coming forward in huge numbers relating how they’ve been harassed and abused by men who have power over them. Most of the time, established systems protect these men from accountability. In this article from Jiayang Fan, a New Yorker staff writer, we get a look at what’s happening in China.

The essay opens with a story from a PhD student inspired by the United States’ Me Too movement to open up about her experience with an academic adviser. Her story led to more accusations against the adviser, and he was eventually dismissed. This is a rare victory, because as Fan says, China employs a more rigid system of patriarchy and hierarchy. There aren’t clear definitions or laws surrounding sexual harassment. Activists are charting unfamiliar territory, which this essay explores.

“Men built this system. No wonder gender equality remains as far off as ever.” – Ellie Mae O’Hagan

Freelance journalist Ellie Mae O’Hagan (whose book The New Normal is scheduled for a May 2020 release) is discouraged that gender equality is so many years away. She argues that it’s because the global system of power at its core is broken. Even when women are in power, which is proportionally rare on a global scale, they deal with a system built by the patriarchy. O’Hagan’s essay lays out ideas for how to fix what’s fundamentally flawed, so gender equality can become a reality.

Ideas include investing in welfare; reducing gender-based violence (which is mostly men committing violence against women); and strengthening trade unions and improving work conditions. With a system that’s not designed to put women down, the world can finally achieve gender equality.

“Invisibility of Race in Gender Pay Gap Discussions” – Bonnie Chu

The gender pay gap has been a pressing issue for many years in the United States, but most discussions miss the factor of race. In this concise essay, Senior Contributor Bonnie Chu examines the reality, writing that within the gender pay gap, there’s other gaps when it comes to black, Native American, and Latina women. Asian-American women, on the other hand, are paid 85 cents for every dollar. This data is extremely important and should be present in discussions about the gender pay gap. It reminds us that when it comes to gender equality, there’s other factors at play, like racism.

Bonnie Chu is a gender equality advocate and a Forbes 30 Under 30 social entrepreneur. She’s the founder and CEO of Lensational, which empowers women through photography, and the Managing Director of The Social Investment Consultancy.

You may also like

15 Great Charities to Donate to in 2024

15 Quotes Exposing Injustice in Society

14 Trusted Charities Helping Civilians in Palestine

The Great Migration: History, Causes and Facts

Social Change 101: Meaning, Examples, Learning Opportunities

Rosa Parks: Biography, Quotes, Impact

Top 20 Issues Women Are Facing Today

Top 20 Issues Children Are Facing Today

15 Root Causes of Climate Change

15 Facts about Rosa Parks

Abolitionist Movement: History, Main Ideas, and Activism Today

The Biggest 15 NGOs in the UK

About the author, emmaline soken-huberty.

Emmaline Soken-Huberty is a freelance writer based in Portland, Oregon. She started to become interested in human rights while attending college, eventually getting a concentration in human rights and humanitarianism. LGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights, and climate change are of special concern to her. In her spare time, she can be found reading or enjoying Oregon’s natural beauty with her husband and dog.

Ontario Human Rights Commission

Language selector, ohrc social links.

Main Navigation

- The Ontario Human Rights Code

- The Human Rights System

- The Ontario Human Rights Commission

- The Human Rights Legal Support Centre

- The Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario

- Frequently asked questions

- Family and marital status

- Gender identity and gender expression

- Race and related grounds

- Receipt of public assistance

- Record of offences

- Sexual orientation

- Goods, services and facilities

- Membership in vocational associations and trade unions

- Teaching human rights in Ontario

- Public education requests

- The OHRC at 60

- Backgrounders and research

- Brochures, fact sheets and guides

- Papers and reports

- Policies and guidelines

- Submissions

You are here

4. bias and prejudice, page controls, page content.

Trans people and other gender non-conforming individuals are often judged by their physical appearance for not fitting and conforming to stereotypical norms about what it means to be a “man” or “woman.” They experience stigmatization, prejudice, bias and fear on a daily basis. While some may see trans people as inferior, others may lack awareness and understanding about what it means to be trans.

“The notion that there are two and only two genders is one of the most basic ideas in our binary Western way of thinking. Transgender people challenge our very understanding of the world. And we make them pay the cost of our confusion by their suffering.” [12]

Bias and prejudice, or simply ignorance, can lead to isolation, vulnerability, disadvantage and discrimination at school, at work, in stores and other services, or even where people live. Trans people living in smaller towns or rural communities may even be more isolated.

4.1 Stereotyping

Many situations of discrimination happen because of negative attitudes, biases and stereotypes about people who are trans or gender non-conforming. Stereotyping is when assumptions are made about individuals based on assumptions about qualities and characteristics of the group they belong to. [13] When people stereotype others, they do not see the real person. Stereotypes are often unfounded generalizations that come from misconceptions and incomplete or false information about people. Anyone can stereotype and not even realize it, even those who are well meaning.

There are widespread stereotypes about trans people in society that often go unquestioned. These include wrong ideas that trans people are “abnormal” or “unnatural,” that they are “frauds,” deceptive and or misrepresent themselves. They may be seen as more likely to take part in criminal activity, be pedophiles, or have mental health problems. Some believe trans women to be a threat to other women. [14]

Anyone who engages in illegal activity including threatening or harassing behavior or assault should be dealt with accordingly under the law. This should not detract in any way from the rights of trans people.

False and harmful stereotypes are rooted in fear and uninformed attitudes and can lead to discrimination against trans people because of their gender identity or expression.

4.2 Transphobia

”Transphobia” is the aversion to, fear or hatred of trans people and communities. Like other prejudices, it is based on stereotypes that are used to justify discrimination, harassment and violence toward trans people.

Many trans Ontarians experience transphobia according to the Ontario-based Trans PULSE survey:

- 98% of trans Ontarians reported at least one experience of transphobia

- Nearly 75% of trans people have been made fun of for being trans

- Over 25% have experienced physical violence because they were trans

- Nearly 25% reported being harassed by police

- Trans women experience transphobia more often than trans men. [15]

4.3 Cisnormativity

“Cisnormativity” (“cis” meaning “the same as”) refers to the commonplace assumption that all people are “cisgender” (not trans). In other words, their gender identity is in line with or “matches” the sex they were assigned at birth, and everyone accepts this as “the norm.”

The term is used to describe stereotypes, negative attitudes and prejudice towards trans people that are more widespread or systemic in society and its institutions. This form of prejudice may even be unintentional and unrecognized by the person or organization responsible, making it all the more entrenched and difficult to address.

“Cisnormative assumptions are so prevalent that they are difficult at first to even recognize… Cisnormativity disallows the possibility of trans existence or trans visibility. As such, the existence of an actual trans person within systems such as healthcare is too often unanticipated and produces a social emergency of sorts because both staff and systems are unprepared for this reality.” [16]

Society’s bias that there is only one right, normal or moral expression of gender underpins this form of prejudice and the discrimination that can result from it. Also see section 7.6 of this policy: Systemic discrimination.

[12] Barbara Findlay, as cited in John Fisher & Kristie McComb , Outlaws & In-laws: Your Guide to LGBT Rights, Same-sex Relationships and Canadian Law (Ottawa: Egale Canada Human Rights Trust, 2003), at 46.

[13] The Supreme Court of Canada has recently said that “Stereotyping, like prejudice, is a disadvantaging attitude, but one that attributes characteristics to members of a group regardless of their actual capacities.” Quebec (Attorney General) v. A , [2013] 1 S.C.R. 61 at para. 326.

[14] For more information see the OHRC’s 1999 Discussion paper: Towards a Policy on Gender Identity , online: OHRC www.ohrc.on.ca/en/discussion-paper-toward-commission-policy-gender-identity .

[15] R. Longman et al ., Experiences of Transphobia among Trans Ontarians. Trans PULSE e-Bulletin, 7 March, 2013. 3 (2), online: Trans PULSE www.transpulseproject.ca .

[16] Greta Bauer et al., “I Don’t Think This Is Theoretical; This Is Our Lives’’: How Erasure Impacts HealthCare for Transgender People” (2009) 20(5) Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 348 at 356, online: Trans PULSE http://webctupdates.wlu.ca/documents/39345/Trans_PULSE._How_erasure_impacts_HC_for_TG_people._JANAC_2009.pdf

Book Prev / Next Navigation

COMMENTS