How can we improve the criminal justice system?

If future scholars of American history remember 2015 for one defining issue, it may well be the rising public uproar over ugly and often fatal encounters between police and black citizens.

The police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., along with videos of police killings in New York City, Cleveland and Chicago, ignited the Black Lives Matter movement. Equally graphic videos from Texas – of a police officer roughing up teenage girls at a pool party or of the officer who threatened to use a Taser on Sandra Bland after pulling her over for failing to signal a lane change – intensified charges that police unfairly target African Americans and other minorities.

As gripping as such incidents are, they still amount to individual anecdotes that can steer a narrative. To provide an unbiased, data-driven analysis of such issues, researchers at Stanford University's School of Engineering have launched what they call the Project on Law, Order & Algorithms .

The project is led by computational social scientist Sharad Goel , an assistant professor of management science and engineering. He also teaches a course at Stanford Engineering that explores the intersection of data science and public policy issues revolving around policing.

Among other activities, Goel's team is building a vast open database of 100 million traffic stops from cities and towns around the nation. The researchers have already gathered data on about 50 million stops from 11 states, recording basic facts about the stop – time, date and location – plus any available demographic data that do not reveal an individual's identity. These demographics might include race, sex and age of the person.

Based on its work thus far, the Knight Foundation recently awarded the team a $310,000 grant to at least double the size of the database, compiling data from as many as 40 states, going back five to 10 years.

The ongoing project has several purposes. The first and most topical goal is to produce a statistical method to assess whether police discriminate against people on the basis of race, ethnicity, age or gender, and, if so, how frequently and under what circumstances. A second but equally important purpose is to help law enforcement agencies design practices that are more equitable and effective at reducing crime.

Ultimately, Goel and his colleagues plan to take the know-how that they will have gained through their analysis of traffic stops and create a software toolkit that others could use to acquire data from municipal or county governments and perform similar analyses. Their idea is to enable other academic researchers, journalists, community groups and police departments to do the same sort of data mining that today requires the expertise of experienced researchers like the members of Goel's team.

Precinct or prejudice?

The public appetite for accurate and comprehensive data has increased sharply. In the aftermath of Michael Brown's death in Ferguson, the U.S. Justice Department concluded that Ferguson's police had routinely targeted black residents and frequently violated their civil rights. African Americans accounted for two-thirds of Ferguson's population, but 85 percent of all traffic stops, 90 percent of all tickets and 93 percent of all arrests. Statewide, a separate report by Missouri's attorney general, as described in the New York Times, found that police were 75 percent more likely to stop black drivers than white ones.

"Technically, much of this is already public data, but it's often not easily accessible, and even when the data are available, there hasn't been much analysis," Goel said.

When researchers do take a deep dive into the data, the results can be as eye-opening for police departments as they are for community groups.

In "Precinct or Prejudice," a new study of New York City's stop-and-frisk policies, Goel and two colleagues found that police were indeed stopping and searching blacks and Hispanics at disproportionate rates. Focusing on about 760,000 stops in which police officers stopped and frisked people on the suspicion of holding an illegal weapon, the researchers found that African Americans who had been stopped were significantly less likely to have a weapon than whites who had been stopped.

When the researchers analyzed the data to discover why, they found that the biggest reason for the racial disparity was the fact that police focused their stop-and-frisk efforts in high-crime precincts heavily populated by minorities. Yet even after adjusting for the effects of location, they found that blacks and Hispanics were stopped a disproportionate amount of the time.

Perhaps the most important finding in "Precinct or Prejudice," however, was that New York City police could have recovered the majority of the weapons by carrying out only a tiny fraction of stop-and-frisk operations. Analyzing a very long list of factors that police officers cited as reasons for stopping and frisking people, the researchers found that only a handful had any predictive value. Seizing on hints of "furtive movement," for example, was almost useless.

In fact, the researchers concluded, if the police had conducted stop-and-frisk operations based on just three factors – a suspicious bulge, a suspicious object, and the sight or sound of criminal activity – they could have found more than half of all the weapons they did find with only 6 percent as many stops.

Predicting crime

Goel is keenly aware that technologies for "predictive modeling," such as using data to predict whether a person is likely to re-commit a violent crime, can have a chilling side. But he notes that a rigorous randomized control trial of a predictive tool used by Philadelphia parole authorities appeared to make life easier for parolees without increasing their risk of re-violation.

"There are all kinds of ways this can go wrong," Goel cautioned. "On the other hand, this can be a win-win situation. Everybody wants to reduce crime in a way that is supportive of the community. We'd like to help law enforcement agencies make better decisions – decisions that are more equitable, efficient and transparent."

Beyond building the database of traffic stops, Goel and his colleagues are using statistical tools to improve other aspects of the judicial system. In one effort, the researchers are working with the district attorney of a large city to improve pre-trial detention practices. In many cases, people arrested on minor crimes cannot afford to make bail and remain stuck in jail for weeks while they await trial.

"I've been amazed by all the interest on campus in this computational approach to criminal justice," Goel said. "In my Law, Order & Algorithms class, students from departments across the university are working together on projects that address some of the most pressing issues in the criminal justice system, from detecting discrimination to improving judicial decisions."

Related | Sharad Goel , assistant professor of management science and engineering at Stanford University

Related Departments

The future of computer music

- Artificial Intelligence

- Technology & Society

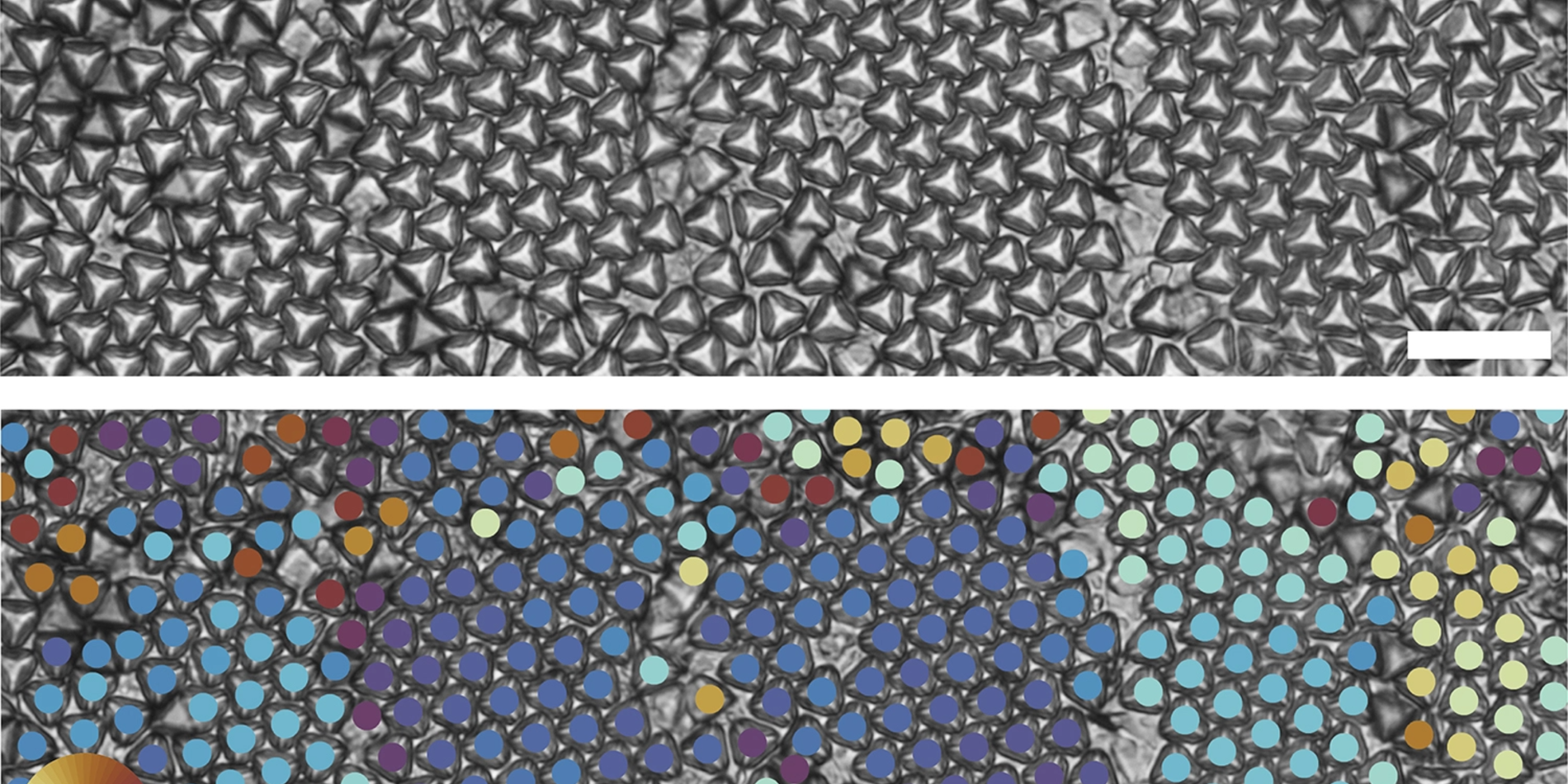

Elusive 3D printed nanoparticles could lead to new shapeshifting materials

The future of pediatric pain

- Social Policy

How can we improve our criminal justice system?

Legal scholar Herbert L. Packer described two models of the criminal justice system: the crime-control model and the due-process model. The crime-control model focuses on harsh policies, laws and regulations. Its goal is to create swift and severe punishments for offenders. The due-process model, on the other hand, aims to promote policies that focus on individual rights. It tends to focus on fairness, justice and rehabilitation.

The dynamics of the crime-control model continue to reinforce prison as the default response to crime – an approach which is inadequate and deficient. A more restorative-justice/healing process for offenders would help foster human dignity, respect and well-being. That’s why Canada should move away from the crime-control model in favour of a restorative-justice model.

It is important to understand how the concept of punishment is linked to broader social theories and phenomena. Émile Durkheim , a well-known French sociologist, emphasizes how punishment is functional for society as it reaffirms the collective conscience and social solidarity. His theory provides an explanation for how moral panics and the public’s mass consumption of prison images in the media justify prisons and make people believe that they are the only way to deter crime and rehabilitate offenders.

Moving restorative justice into the mainstream

Marxist theory offers a holistic approach to the explanation of social life. It argues that society has a definite structure, as well as a central dynamic, which patterns social practices in specific and describable ways that connect various areas of social life. Marxist theory argues that the way economic and political activity is organized and controlled tend to shape the rest of society. These ideals are different from the legal and technical aspects of punishment, which tend to focus solely on deterring future criminal activity through laws that are retributive.

Retributive laws and policies focus on deterrence, denunciation and incapacitation. The truth is that crime-control, zero-tolerance and harsh policies do not work . The dominant retributive model of justice does not allow for healing the offenders because the purpose of incarceration is solely to punish them. Crime-control policies and harsh punishments lead to the increased racialization of prison populations, as well as the high levels of the marginalized and mentally ill in prisons. Crime-control policies and the punitive model of crime fail to look at how social and economic factors can make a person more prone to offend and ultimately get funneled into the criminal-justice system.

On the other hand, restorative-justice objectives look at how institutional and interpersonal relationships can address the issues of social domination that permeate through class, race, gender, culture, physical and mental ability, and sexual orientation. Restorative justice is a healing process, which focuses on social arrangements that foster human dignity, respect and well-being. The purpose of restorative justice is to address underlying systemic issues, provide victim-offender reintegration, restore harmony and address harm through various legal orders. This system further tries to help those marginalized individuals who are most vulnerable to experiencing discrimination and human rights violations to reintegrate back into society in a positive way.

Although restorative justice tries to move away from the punitive model of justice, there are some criticisms associated with restorative-justice policies as well. Many argue that the ideals associated with restorative justice can be implemented in society only once we start to question norms and alter existing social structures that make crime-control policies and the prison-punishment system necessary in the first place. There is a need for a new system of restorative justice that is based on social and economic justice, respect for all and restoration. Such a system is hard to implement in a social society where power and equality are not equally structured or equally distributed among members of the community. These inequalities and power differences legitimize the use of crime-control policies and the prison-punishment system, and pull the marginalized into the criminal justice system with the use of harsh laws and policies.

Given the failures of crime-control objectives and its exploitation of the most vulnerable populations in our society, Canada should move away from such harsh crime-control policies. We need restorative justice and a radical transformation in the way that we conceive justice and punishment. This is important because inmates need sustainable justice and rehabilitation. Alternative methods are needed to help the marginalized, those suffering from violence, mental health issues and drug addiction.

You are welcome to republish this Policy Options article online or in print periodicals, under a Creative Commons/No Derivatives licence.

Republish this article

by Navjot Kaur, Bavneet Chauhan. Originally published on Policy Options December 8, 2021

This <a target="_blank" href="https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/december-2021/how-can-we-improve-our-criminal-justice-system/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://policyoptions.irpp.org">Policy Options</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img id="republication-tracker-tool-source" src="https://policyoptions.irpp.org/?republication-pixel=true&post=101145&ga4=G-GR919H3LRJ" style="width:1px;height:1px;">

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

Related stories

Failure to protect: the criminalization of survivors of intimate-partner violence

Policing women’s sexuality in the name of protection

Why do young offenders return to prison?

GetGoodEssay

how to improve the criminal justice system essay

The criminal justice system is a complex network of laws, institutions, and individuals responsible for ensuring that justice is served in society. However, despite the best efforts of many dedicated professionals, the criminal justice system is not without its flaws, and there is ample room for improvement. This essay will explore some of the most pressing issues facing the criminal justice system today, and suggest strategies for improvement.

Discrimination and Bias

One of the most persistent problems facing the criminal justice system is discrimination and bias. Research has shown that individuals from minority communities, such as African Americans and Latinos, are more likely to be arrested, convicted, and sentenced to longer terms than their white counterparts, even when the circumstances of their crimes are similar. This bias is often rooted in systemic issues such as racial profiling, unequal enforcement of the law, and unequal representation in the criminal justice system.

Addressing Discrimination and Bias

To address discrimination and bias in the criminal justice system, it is important to take a multi-faceted approach that includes changes at the legislative, institutional, and individual levels.

Legislative Changes: The first step in addressing discrimination and bias in the criminal justice system is to pass laws that explicitly prohibit racial profiling and other forms of discrimination. In addition, legislation can be passed to promote diversity and equality in hiring and training within criminal justice organizations.

Institutional Changes: Institutions can work to address discrimination and bias through policies and procedures that promote fairness and impartiality in the criminal justice system. This can include providing diversity and sensitivity training for employees, conducting regular reviews of case outcomes to identify and address any patterns of discrimination, and implementing strategies to increase diversity in leadership and decision-making positions.

Individual Changes: Individuals within the criminal justice system can play a key role in promoting fairness and impartiality. This can include embracing a growth mindset, being aware of personal biases and taking steps to mitigate them, and advocating for changes within the system that promote equality and fairness.

Alternative Approaches to Punishment

Another issue facing the criminal justice system is the reliance on punishment as the primary response to crime . While punishment may be necessary in some cases, research has shown that alternative approaches, such as rehabilitation and restorative justice, can be more effective in reducing recidivism and promoting public safety.

Rehabilitation: Rehabilitation programs aim to help individuals who have committed crimes to understand the root causes of their behavior and develop the skills and support they need to turn their lives around. These programs can include therapy, job training, and education, and can be particularly effective for individuals who have committed non-violent crimes.

Restorative Justice: Restorative justice approaches aim to repair the harm caused by criminal behavior, and to restore relationships between individuals and communities. This can include programs such as mediation, community service, and victim-offender reconciliation, and can be an effective alternative to traditional punishment for many individuals who have committed crimes.

Improving Access to Justice

Another challenge facing the criminal justice system is ensuring that all individuals have access to justice, regardless of their financial means. This can be particularly difficult for individuals who cannot afford to pay for legal representation, and who may be forced to navigate the criminal justice system on their own.

Improving Access to Legal Representation: One of the most effective ways to improve access to justice is to provide individuals with access to quality legal representation. This can include programs that provide free or low-cost legal services, as well as initiatives that work to increase the number of public defenders available to represent individuals in court.

Expanding Access to Alternative Dispute Resolution: Alternative dispute resolution (ADR) processes, such as mediation and arbitration, can provide individuals with an alternative to the traditional court system, and can be less costly and time-consuming than going to court. Expanding access to ADR can also help to reduce the burden on the criminal justice system, allowing it to focus its resources on the most serious cases.

Improving Police-Community Relations

Another important issue facing the criminal justice system is improving police-community relations. This includes building trust between law enforcement and the communities they serve, and addressing issues of excessive use of force and discrimination by police officers.

Community Policing: Community policing is a strategy that emphasizes partnerships between law enforcement and the communities they serve. By working together, police and community members can identify and address the underlying issues that contribute to crime, and develop effective solutions to these problems.

Training and Professional Development: Providing law enforcement officers with ongoing training and professional development can help to address issues of excessive use of force and discrimination. This can include training on de-escalation techniques, cultural competency, and crisis management.

The criminal justice system is facing a number of challenges, including discrimination and bias, a reliance on punishment as the primary response to crime, limited access to justice, and strained police-community relations. However, by taking a multi-faceted approach and implementing evidence-based solutions, it is possible to make meaningful improvements to the criminal justice system, and to ensure that justice is served in society.

- Recent Posts

- Essay on Criminological Theories in ‘8 Mile’ - September 21, 2023

- Essay on Employment Practices in South Africa: Sham Hiring for Compliance - September 21, 2023

- Essay on The Outsiders: Analysis of Three Deaths and Their Impact - September 21, 2023

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Listen Live

Here and Now

Here! Now! In the moment! Paddling in the middle of a fast moving stream of news and information. Here & Now is a daily news magazine, bringing you the news that breaks after "Morning Edition" and before "All Things Considered."

- Courts & Law

- Criminal Justice

If more people attended criminal court, we could advance criminal justice. Here’s how

Court-watching makes our justice system fairer and builds an educated public, writes jeremy isard..

- Jeremy Isard

(JanPietruszka/Bigstock)

Related Content

Pa.’s ChildLine Registry does more harm than good for children of color

Attorney Jamie Gullen, who has spent a decade representing youth at Community Legal Services, takes aim at the state’s ChildLine Registry for violating due process rights.

2 years ago

I’ve worked at Community Legal Services of Philadelphia for 10 years. Here’s why I’m angry — and why I want big change

For 10 years, Caitlin Nagel has fought for Philadelphians at Community Legal Services. When it comes to justice, she says we need more than “Band-Aid solutions.”

Court-watching programs to enhance courtroom fairness exist across the country. In Atlanta, for example, the Southern Center for Human Rights uses court watching to combat the criminalization of poverty. On one recent morning , their investigator witnessed a 56-year-old Black man in a wheelchair jailed for pedestrian walking in the roadway. There are similar initiatives in Philadelphia , New Orleans , Chicago , New York City, and Nashville .

In addition to election-year fear-mongering, too much of our public legal education comes from television. “Law and Order” remains among the most-watched TV shows in the country. Scholars have long tried to quantify the “ CSI Effect ,” the impact of TV dramas on real-life jury verdicts.

Meanwhile, many Americans steer clear of jury service, people of color are underrepresented on juries across the country, and all-white juries make worse decisions.

Court-watching makes our justice system fairer and builds an educated public. Getting a complete cross-section of society into the courtroom as spectators will reduce the alienation felt by many of us when we report for jury duty.

It will help the court feel like a community institution. Most importantly, it will present the public with a real portrait of what occurs, which in turn may make for better jurors and a voting public better equipped to champion a more equitable judicial system.

I encourage you to walk into any big city criminal courthouse any day of the week. It will cost you nothing but an afternoon.

Jeremy Isard is a public defender and trial attorney in Philadelphia, where he represents clients charged with felony offenses. He grew up in Drexel Hill.

Your go-to election coverage

Sign up for Your Vote 2022 , a free email newsletter breaking down the 2022 midterm elections in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

You may also like

‘The most dangerous place to be in America right now is a prison or jail’: Philly lawyer discusses situation for those incarcerated during pandemic

Morning Edition host Jennifer Lynn speaks with Philadelphia trial lawyer Joe Oxman about COVID-19’s effect on the legal system in Pennsylvania.

3 years ago

Expect different courtroom arrangements when criminal jury trials resume in city

Come Sept. 8, jurors will listen from the gallery, Plexiglas will separate witnesses from prosecutors and defense attorneys. Public, press will be on Zoom.

4 years ago

Federal judge: Philly courts must record bail hearings

Historically, these proceedings have effectively occurred off-the-record. There’s no stenographer and the public isn’t allowed to record what happens.

Want a digest of WHYY’s programs, events & stories? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Together we can reach 100% of WHYY’s fiscal year goal

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Reflections on Criminal Justice Reform: Challenges and Opportunities

Pamela k. lattimore.

RTI International, 3040 East Cornwallis Road, Research Triangle Park, NC 27703 USA

Associated Data

Data are cited from a variety of sources. Much of the BJS data cited are available from the National Archive of Criminal Justice Data, Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research. The SVORI data and the Second Chance Act AORDP data are also available from NACJD.

Considerable efforts and resources have been expended to enact reforms to the criminal justice system over the last five decades. Concerns about dramatic increases in violent crime beginning in the late Sixties and accelerating into the 1980s led to the “War on Drugs” and the “War on Crime” that included implementation of more punitive policies and dramatic increases in incarceration and community supervision. More recent reform efforts have focused on strategies to reduce the negative impacts of policing, the disparate impacts of pretrial practices, and better strategies for reducing criminal behavior. Renewed interest in strategies and interventions to reduce criminal behavior has coincided with a focus on identifying “what works.” Recent increases in violence have shifted the national dialog from a focus on progressive reforms to reduce reliance on punitive measures and the disparate impact of the legal system on some groups to a focus on increased investment in “tough on crime” criminal justice approaches. This essay offers some reflections on the “Waged Wars” and the efforts to identify “What Works” based on nearly 40 years of work evaluating criminal justice reform efforts.

The last fifty-plus years have seen considerable efforts and resources expended to enact reforms to the criminal justice system. Some of the earliest reforms of this era were driven by dramatic increases in violence leading to more punitive policies. More recently, reform efforts have focused on strategies to reduce the negative impacts of policing, the disparate impacts of pretrial practices, and better strategies for reducing criminal behavior. Renewed interest in strategies and interventions to reduce criminal behavior has coincided with a focus on identifying “what works.” Recent increases in violence have shifted the national dialog about reform. The shift may be due to the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 epidemic or concerns about the United States returning to the escalating rise in violence and homicide in the 1980s and 1990s. Whichever proves true, the current rise of violence, at a minimum, has changed the tenor of policymaker discussions, from a focus on progressive reforms to reduce reliance on punitive measures and the disparate impact of the legal system on some groups to a focus on increased investment in “tough on crime” criminal justice approaches.

It is, then, an interesting time for those concerned about justice in America. Countervailing forces are at play that have generated a consistent call for reform, but with profound differences in views about what reform should entail. The impetus for reform is myriad: Concerns about the deaths of Black Americans by law enforcement agencies and officers who may employ excessive use of force with minorities; pressures to reduce pretrial incarceration that results in crowded jails and detention of those who have not been found guilty; prison incarcerations rates that remain the highest in the Western world; millions of individuals who live under community supervision and the burden of fees and fines that they will never be able to pay; and, in the aftermath of the worst pandemic in more than a century, increasing violence, particularly homicides and gun violence. This last change has led to fear and demands for action from communities under threat, but it exists alongside of other changes that point to the need for progressive changes rather than reversion to, or greater investment in, get-tough policies.

How did we get here? What have we learned from more than 50 years of efforts at reform? How can we do better? In this essay, I offer some reflections based on my nearly 40 years of evaluating criminal justice reform efforts. 1

Part I: Waging “War”

The landscape of criminal justice reform sits at the intersection of criminal behavior and legal system response. Perceptions of crime drive policy responses. Perceptions of those responsible for crime also drive responses. And perceptions of those responses result in demands for change. To establish context for the observations that follow, this section describes trends in crime, the population of justice-involved individuals, and the expenditures supporting the sprawling criminal justice enterprise in the United States since the mid-to-late twentieth century.

But first, my perspective: Over the last nearly 40 years, I have observed justice system reform efforts since working, while a first-year graduate student in 1983, on a National Institute of Justice (NIJ) grant that funded a randomized control trial of what would now be termed a reentry program (Lattimore et al., 1990 ). After graduate school, I spent 10 years at NIJ, where I was exposed to policy making and the relevance of research for both policy and practice. I taught for several years at a university. And, for most of my career, I have been in the trenches at a not-for-profit social science research firm. Throughout my career, I have conducted research and evaluation on a broad array of topics and have spent most of my time contemplating the challenges of reform. I’ve evaluated single programs, large federal initiatives, and efforts by philanthropies to effect reform. I’ve used administrative data to model criminal recidivism to address—to the degree statistical methods allow—various dimensions of recidivism (type, frequency, and seriousness). I’ve developed recidivism models for the practical purpose of assessing risk for those on community supervision and to explore the effects of covariates and interventions on recidivism and other outcomes. I’ve participated in research attempting to understand the shortcomings of and potential biases in justice data and the models that must necessarily use those data. While most of my work has focused on community corrections (e.g., probation and post-release interventions and behavior) and reentry, I have studied jail diversion programs, jail and pretrial reform, and efforts focused on criminal record expungement. These experiences have illuminated for me that punitiveness is built into the American criminal justice system—a punitiveness that traps many people from the time they are first arrested until they die.

Crime and Correctional Population Trends

The 1960s witnessed a dramatic rise in crime in the United States, and led to the so-called “War on Crime,” the “War on Drugs,” and a variety of policy responses, culminating with the passage of the Violent Offender Incarceration and Truth-in-Sentencing Act of 1994 (“The 1994 Crime Act”; Pub. L. 103–322). Figure 1 shows the violent crime rate in the United States from 1960 to 1994. 2 In 1960, the violent crime rate in the United States was 161 per 100,000 people; by 1994 the rate had increased more than four-fold to nearly 714 per 100,000. 3 As can be seen, the linear trend was highly explanatory (R-square = 0.96)—however, there were two obvious downturns in the trend line—between 1980 and 1985 and, perhaps, between 1991 and 1994.

US Violent Crime Rate, 1960–1994

Homicides followed a similar pattern. Figure 2 shows the number of homicides each year between 1960 and 1994. In 12 years (1960 to 1972), the number of homicides doubled from 9,100 to 18,670. By 1994, the number had grown to 23,330—but it is worth noting that there were multiple downturns over this period, including a drop of more than 4,000 between 1980 and 1984. These figures show the backdrop to the “War on Drugs” and the “War on Crime” that led reformers to call for more punitive sentencing, including mandatory minimum sentences, “three-strikes laws” that mandated long sentences for repeat offenders, and truth-in-sentencing statutes that required individuals to serve most of their sentences before being eligible for release. This was also the period when the 1966 Bail Reform Act, which sought to reduce pretrial detention through the offer of money bond, was supplanted in 1984 by the Pretrial Reform Act, which once again led to increased reliance on pretrial detention.

United States Murder and Non-negligent Manslaughter Rate, 1960–1994

The 1994 Crime Act, enacted during the Clinton Administration, continued the tough-on-crime era by enabling more incarceration and longer periods of incarceration that resulted in large increases in correctional populations. In particular, the Violent Offender Incarceration and Truth-in-Sentencing (VOI/TIS) Incentive Grant Program, funded by the Act, provided $3 billion to states to expand their jail and prisons capacities between FY1996 and FY2001 and to encourage states to eliminate indeterminate sentencing in favor of laws that required individuals to serve at least 85% of their imposed sentences.

Figure 3 shows the dramatic rise in the number of state and federal prisoners prior to passage of the 1994 Crime Act—the number of prisoners more than tripled between 1980 and 1994. 4 The increase in numbers of prisoners was not due to shifts from jail to prison or from probation to prison, given that all correctional populations increased dramatically over this 14-year period—jail populations increased 164% (183,988 to 486,474), probation increased 166% (1,118,097 to 2,981,022), and parole increased 213% (220,438 to 690,371).

State and Federal Prisoners in the US, 1960–1994

So, what happened after passage of the 1994 Crime Act? Fig. 4 shows the violent crime rate from 1960 through 2020. As can be seen, the decrease in the violent crime rate that began prior to passage of the 1994 Crime Act continued. And, notably, it preceded the influx of federal funding to put more police on the streets, build more jails and prisons, and place more individuals into the custody of local, state, and federal correctional agencies. Even with a small increase between 2019 and 2020, the violent crime rate in 2020 was 398.5 per 100,000 individuals, well below its 1991 peak of 758.2. 5

United States Violent Crime Rate (violent crimes per 100,000 population), 1960–2020

Figure 5 shows the US homicide rate from 1960 to 2020. Consistent with the overall violent crime rate, the homicide rate in 2020 remained well below the peak of 10.2 that occurred in 1981. (Rates also may have risen in 2021—as evidenced by reports of large increases in major U.S. cities—but an official report of the 2021 number and rate for the U.S. was not available as of the time of this writing.) The rise in this rate from 2019 to 2020 was more than 27%— worthy of attention and concern. It represents the largest year-over-year increase between 1960 and 2020. However, there have been other years where the rate increased about 10% (1966, 1967, 1968, 2015, and 2016), only then to drop back in subsequent years. Further, it is difficult to determine whether the COVID-19 pandemic, which has caused massive disruptions, is a factor in the increase in homicides or to know whether the homicide rate will abate as the pandemic ebbs. Finally, it bears emphasizing that during this 60-year period there have been years when the homicide rate fell by nearly 10% (e.g., 1996, 1999). From a policy perspective, it seems prudent to be responsive to increases in crime but also not to over-react to one or two years of data—particularly during times of considerable upheaval.

United States Murder and Nonnegligent Manslaughter Rate, 1960–2020

The growth in correctional populations, including prisoners, that began in the 1970s continued well into the twenty-first century—in other words, long after the crime rate began to abate in 1992. Figure 6 shows the prison population and total correctional population (state and federal prison plus jail, probation, and parole populations summed) between 1980 and 2020. Both trends peaked in 2009 at 1,615,500 prisoners and 7,405,209 incarcerated or on supervision. Year-over-year decreases, however, have been modest (Fig. 7 ), averaging about 1% (ignoring the steep decline between 2019 and 2020). The impact of factors associated with COVID-19, including policy and practice responses, resulted in a 15% decrease in the numbers of state and federal prisoners and a 14% decrease in the total number of adults under correctional control. Based on ongoing projects in pretrial and probation, as well as anecdotal evidence related to court closures and subsequent backlogs, it is reasonable to assume that some, if not most, of the decline in populations in 2020 was due to releases that exceeded new admissions as individuals completed their sentences and delays in court processing reduced new admissions. To the extent that these factors played a role, it is likely that in the immediate near term, we will see numbers rebound to values closer to what prevailed in 2019.

United States Prison and Total Correctional Populations, 1980–2020

Year-over-Year Change in Prison and Total Correctional Populations, 2981–2020

Responding with Toughness (and Dollars)

The increase in crime beginning in the 1960s led to a political demand for a punitive response emphasized by Richard Nixon’s “War on Crime” and “War on Drugs.” In 1970, Congress passed four anticrime bills that revised Federal drug laws and penalties, addressed evidence gathering against organized crime, authorized preventive detention and “no-knock” warrants, and provided $3.5 billion to state and local law enforcement. 6 Subsequent administrations continued these efforts, punctuated by the Crime Act of 1994. As described by the U.S. Department of Justice:

The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 … is the largest crime bill in the history of the country and will provide for 100,000 new police officers, $9.7 billion in funding for prisons and $6.1 billion in funding for prevention programs …. The Crime Bill provides $2.6 billion in additional funding for the FBI, DEA, INS, United States Attorneys, and other Justice Department components, as well as the Federal courts and the Treasury Department. 7

Much of the funding went to state and local agencies to encourage the adoption of mandatory minimum sentences, “three strikes” laws, and to hire 100,000 police officers and build prisons and jails. This funding was intended to steer the highly decentralized United States criminal justice “system” towards a more punitive approach to crime; this system encompasses all levels of government (local, state, and federal) and all branches of government (executive, judicial, legislative).

The nation’s crime rate peaked in 1992. So, this “largest crime bill in the history of the country” began a dramatic increase in funding for justice expenditures just as crime had already begun to decline. Figure 8 shows that expenditures increased roughly 50% in real dollars between 1997 and 2017—from $188 billion to more than $300 billion dollars (Buehler, 2021 ). 8 More than half of that increase-—$65.4 billion additional—went to police protection. Roughly $50 billion additional went to the judiciary and corrections.

United States Justice Expenditures, 1997–2017

So, what did these increases buy? Dramatically declining crime rates (Figs. (Figs.4 4 and and5) 5 ) suggest that numbers of crimes also declined. That can be seen in Fig. 9 , which shows offenses known and an estimate of offenses cleared for selected years between 1980 and 2019. 9 In 1991, there were 11,651,612 known property offenses and 1,682,487 known violent offenses—these numbers declined 47% and 34% by 2019.

Offenses Known and Cleared in the US, Selected Years 1980–2019

Declining numbers of crimes and dramatic increases in expenditures on policing and justice system operation would suggest that there should have been improvements in offense clearance rates during this time. This did not happen. Crime clearance rates stayed roughly constant, which means that the numbers of offenses cleared declined by percentages like declines in the number of offenses over this period—49% for property offenses and 33% for violent offenses. More than 750,000 violent offenses and more than 2 million property offenses were cleared in 1991 compared to about 500,000 violent offenses and 1 million property offenses in 2019.

Presently, as violent crime ticks up, we are hearing renewed calls for “tough-on-crime” measures. Some opinion writers have compared 2022 to Nixon’s era. Kevin Boyle noted:

[Nixon] already had his core message set in the early days of his 1968 campaign. In a February speech in New Hampshire, he said: “When a nation with the greatest tradition of the rule of law is torn apart by lawlessness, when a nation which has been the symbol of equality of opportunity is torn apart by racial strife … then I say it’s time for new leadership in the United States of America.” There it is: the fusion of crime, race and fear that Nixon believed would carry him to the presidency. 10

Responding to the recent increase in violent crime, President Joseph Biden proposed the Safer America Plan to provide $37 billion “to support law enforcement and crime prevention.” 11 The Plan includes more than $12 billion in funds for 100,000 additional police officers through the Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) program. This proposal echoes the “100,000 cops on the street” that was a centerpiece of the 1994 Crime Act, which created the COPS office and program. Unlike the 1994 Crime Act, however, the Safer America Plan does not include funding for prisons and jails. Both the 1994 Crime Act and the Safer America Plan address gun violence, strengthen penalties for drug offenses, and provide support for programs and interventions to make communities safer and to address criminal recidivism.

The previous 50 or 60 years witnessed reforms efforts other than these that largely focused on bolstering the justice system infrastructure. The 1966 Bail Reform Act sought to reduce pretrial detention through the offer of money bond, but subsequently was supplanted by the 1984 Pretrial Reform Act that once again promoted pretrial detention. 12 This century—as jail populations exceeded 700,000, with most held prior to conviction—there has been considerable attention to eliminate money bond, which disproportionately leads to pretrial detention for poor and marginalized individuals (and release for the “well-heeled”). Private philanthropy has led much of this focus on pretrial and bail reform. For example, the MacArthur Foundation has spent several hundred million dollars on their Safety and Justice Challenge since 2015 with a goal of reducing jail populations and eliminating racial and ethnic disparity. 13 The Laura and John Arnold Foundation (LJAF) took a different approach and has invested substantial sums in the development and validation of a pretrial assessment instrument (the Public Safety Assessment or PSA) that provides assessments of the likelihood an individual will fail to appear to court or be arrested for a new crime or new violent crime if released while awaiting trial. 14 Although assessment algorithms have been criticized for lack of transparency and for perpetuating racial bias, the PSA scoring algorithm is publicly available and has not shown evidence of racial bias in a series of local validations conducted by RTI for LJAF. New York and New Jersey are among the states that have attempted to reduce reliance on money bond. However, as violent crime has increased, these efforts have faced considerable pushback.

The bail bonds industry has been a vocal opponent of efforts to reduce or eliminate the use of money bond. This industry is not the only one that profits from the imposition of punishment. As Page and Soss ( 2021 ) recently reported, “Over the past 35 years, public and private actors have turned US criminal justice institutions into a vast network of revenue-generating operations. Today, practices such as fines, fees, forfeitures, prison charges, and bail premiums transfer billions of dollars from oppressed communities to governments and corporations.” Fines, fees, and forfeitures generally profit the governments and agencies that impose them—although supervision fees to private probation services benefit businesses, as do fees for electronic monitoring, and drug testing. The Prison Policy Institute reports that there are more than 4,000 companies that profit from mass incarceration. 15 Court and supervision fees can quickly add up to hundreds or even thousands of dollars, burdening people with crushing debt and the threat of jail if they don’t pay. 16 There can be other consequences as well. After Florida passed a constitutional amendment to restore voting rights to individuals once they had completed their carceral or community sentence, the State specified that the right to vote would not be restored until an individual had paid all outstanding fees and fines. In addition, mistakenly voting with outstanding fees and fines is a felony. 17

Other work to reform pretrial justice includes early provision of defense counsel, and implementation of diversion programs for individuals charged with low-level offenses or who have behavioral health issues. The sixth amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees criminal defendants in the United States a right to counsel. In some jurisdictions (and the Federal court system), this is the responsibility of an office of public defense. In others, private defense counsel is appointed by the Court. Regardless, public defense is widely understood to be poorly funded. As noted by Arnold Ventures, a philanthropy currently working to improve access to defense, “The resulting system is fragmented and underfunded; lacks quality control and oversight; and fails to safeguard the rights of the vast majority of people charged with crimes who are represented by public defenders or indigent counsel.” 18

Mental health problems are prevalent among individuals incarcerated in local jails and prisons. The Bureau of Justice Statistics, in a report by Bronson and Berzofsky ( 2017 ), reported that “prisoners and jail inmates were three to five times as likely to have met the threshold for SPD [serious psychological distress] as adults in the general U.S. population.” Bronson and Berzofsky further reported that 44% of individuals in jail reported being told they had a mental disorder. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration’s GAINS Center has been at the forefront of efforts to implement jail diversion programs for individuals with mental health or substance use disorders and has also played a significant role in the establishment of treatment courts. 19 Crisis Intervention Training (CIT) for law enforcement to improve interaction outcomes between law enforcement and individuals in crisis. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) notes that “The lack of mental health crisis services across the U.S. has resulted in law enforcement officers serving as first responders to most crises. A Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) program is an innovative, community-based approach to improve the outcomes of these encounters.” 20 Non-law enforcement responses—such as the CAHOOTS program that was developed in Eugene, Oregon—to certain calls for service are also being tested in multiple communities. 21 Despite multiple efforts to identify appropriate alternatives to jail, individuals with mental health disorders continue to disproportionately fill the nation’s jails.

A Recapitulation

The 1970 crime bills that passed early in Nixon’s presidency set the stage for the infusion of federal dollars that has provided billions of dollars in funding for police and prisons. Between 1970 and 1994, the number of adults in state and federal prisons in the United States increased from less than 200,000 to nearly 1 million. In 2019, that number stood at more than 1.4 million down from its peak in 2009. Another 734,500 individuals were in jail and more than 4.3 million were in the community on probation or parole. Although representing a dramatic decline since these populations peaked about 2009, this still means that more than 6 million adults were under the supervision of federal, state, and local corrections agencies in 2019.

Thus, it is important to recognize that we are at a very different place from the Nixon era. Today, the numbers (and rates) of individuals who are “justice-involved” remain at near record highs. As the progressive efforts of the twenty-first century encounter headwinds, it is worth waving a caution flag as the “remedies” of the twentieth century—more police, “stop and frisk,” increased pretrial detention—are once again being proposed to address violent crime.

Part II: Finding “What Works”

The 1994 Crime Act and subsequent reauthorizations also included funding for a variety of programs, including drug courts, prison drug treatment programs, and other programs focused on facilitating reentry and reducing criminal recidivism. Subsequent legislation authorized other Federal investments that resurrected rehabilitation as a goal of correctional policy. The Serious and Violent Offender Reentry Initiative (SVORI) provided $100 million (and some limited supplements) to agencies to develop programs that began in prison and continued into the community and were intended to improve outcomes across a range of domains—community reintegration, employment, family, health (including mental health), housing, substance abuse, supervision compliance and, of course, recidivism (see Lattimore et al., 2005b ; Winterfield et al., 2006 ; Lattimore & Visher, 2013 , 2021 ; Visher et al., 2017 ). Congress did not reauthorize SVORI but instead authorized the Prisoner Reentry Initiative (PRI) managed by the U.S. Department of Labor; PRI (now the Reintegration of Ex-Offenders or RExO program) provides funding for employment-focused programs for non-violent offenders. In 2006, a third reentry-focused initiative was funded—the Marriage and Incarceration Initiative was managed by the Department of Health and Human Services and focused on strengthening marriage and families for male correctional populations. In 2008, Congress passed the Second Chance Act (SCA) to provide grants for prison and jail reentry programs. The SCA grant program administered by the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) was reauthorized in 2018; it continues to provide reentry grants to state and local agencies (see Lindquist et al., 2021 ). These initiatives all primarily focused on supporting efforts at the state and local level. The First Step Act of 2018 focused on reforms for the federal prison system. These efforts signified a substantial increase in efforts aimed at determining “what works” to reduce criminal behavior—and provided an opportunity to rebut the “nothing works” in correctional programming that followed the publication of research by Lipton ( 1975 ).

Elsewhere, I have summarized some of the research into Federal initiatives that I have conducted over the years (Lattimore, 2020 ). These studies comprise work in dozens of states, involving thousands of individuals and have included studies of drug treatment, jail diversion, jail and prison reentry, and probation. Some involved evaluation of a substantial Federal investment, such as the multi-site evaluation of SVORI.

These evaluations, as has been largely true of those conducted by others, have produced mixed results. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses focusing on the effectiveness of adult correctional programming have yielded findings of modest or negligible effects (e.g., Aos et al., 2006 ; Bitney et al., 2017 ; Lipsey & Cullen, 2007 ; MacKenzie, 2006 ; Sherman, et al., 1997 ). In an updated inventory of research- and evidence-based adult programming, the Washington State Institute for Public Policy (Wanner, 2018 ) identified a variety of programs for which evidence suggests significant if modest effect sizes. As has been identified by others (e.g., MacKenzie, 2006 ), the most effective programs focused on individual change, including, for example, cognitive behavior therapy (estimated effect size of -0.11). Treatment-oriented intensive supervision programs were found to reduce recidivism by about 15%, while surveillance-oriented intensive supervision was found to have no demonstrated effects. Several types of work and educational programs (correctional industries, basic adult education, prison-based vocational education, and job training and assistance in the community) were found to reduce recidivism between 5 and 22%. Most non-zero treatment effect sizes were between about 5% and 15%. Lipsey and Cullen ( 2007 ) also suggest 14% to 22% reductions in recidivism for adult rehabilitation treatment programs.

Two thoughts about these small effects warrant consideration. The first, of course, is why reducing criminal behavior appears to be so difficult. Second, however, is that, in recognizing the first, perhaps we should adapt more realistic expectations about what can be achieved and acknowledge that even small effects can have a meaningful impact on public safety.

Challenges: Why Is Effective Criminal Justice Reform So Difficult?

One issue with most federal funding streams is “short timelines.” For example, typical of grant programs of this type, SVORI grantees were given three years of funding. During this time, they had to develop a programmatic strategy, establish interagency working arrangements, identify program and service providers, develop a strategy for identifying potential participants, and implement their programs. Three years is a very short time to develop a program that incorporates needs assessment, provides a multiplicity of services and programs within an institution, and creates a path for continuation of services as individuals are released to various communities across a state.

The “short timelines” problem underlies, and contributes to, a variety of other considerations that can plague efforts to identify “what works.” Based on my experiences, these considerations, which I discuss further below, include the following:

- People: Justice-involved individuals have multiple needs and there is an emerging question as to whether addressing these needs is the best path to desistance.

- Programs: Interventions often lack adequate logic models and are poorly implemented.

- Methods: Evaluations frequently are underpowered and unlikely to scale the alpha 0.05 hurdle typically used to identify statistically significant effects.

First, it is important to recognize that justice-involved individuals face serious and complex challenges that are difficult to remedy. Many scholars have highlighted the myriad of challenges faced by individuals returning to the community from prison (e.g., see Petersilia, 2003 ; Travis, 2005 ; Travis & Visher, 2005 ). In interviews conducted with 1,697 men and 357 women who participated in the SVORI multisite evaluation, 95% of women and 94% of men said at the time of prison release that they needed more education. Nearly as many—86% of women and 82% of men—said they needed job training. More than two-thirds indicated that they needed help with their criminal thinking and three-quarters said they needed life skills training. They were somewhat less likely to report needing substance use disorder or mental health treatment but still—at the time of prison release—66% of the women and 37% of the men reported needing substance use treatment and 55% of the women and 22% of the men reported needing mental health treatment.

Half of these individuals had participated in SVORI programs while incarcerated and the proportions reported reflect their self-assessment of need after in-prison receipt of programming. Figure 10 shows the percentages of SVORI and non-SVORI groups who reported receiving a select set of services and programs during their incarceration. Several things standout: (1) The receipt of programs and services during incarceration was much less than the indicated need at the time of release; and (2) SVORI program participants were more likely to report receiving services than the comparison group members who were not in SVORI programs.

Self-reported service receipt during incarceration for SVORI program evaluation participants. Note: * = p < = 0.05. Educ = educational programming, EmplSrv = employment-related services, CrimAtt = programs for criminal attitudes including cognitive behavior therapy, LifeSk = life skills, AODTx = substance abuse treatment, and MHTx = mental health treatment. Sample sizes were SVORI men (863), non-SVORI men (834), SVORI women (153) and non-SVORI women (204).

Source: Lattimore & Visher (2009)

More recently, Lindquist et al. ( 2021 ) completed a seven-site evaluation of Second Chance Act reentry programs that were a mix of jail- and prison-based programs. About half of the study participants reported having received substance use disorder treatment and about one-third reported having received mental health treatment. At release, they reported limited-service receipt. For example, there was no significant difference between receipt of educational programming (23% of SCA program participants compared with 17% for comparison group members). SCA program participants were more likely to report receiving any employment services (60% versus 40%), which included job assistance, employment preparation, trade or job training programs, vocational or technical certifications, and transitional job placement or subsidized employment. SCA program participants were also more likely to report receiving cognitive behavioral services (58% versus 41%). But, again, not all program participants received services despite needing them and some comparison subjects received services.

Limited access to treatment by program participants and some access to treatment by comparison subjects were also observed in a multi-site study of pre- and post-booking jail diversion programs for individuals with co-occurring substance use disorder and serious mental illness (Broner et al., 2004 ; Lattimore et al., 2003 ). Across eight study sites, 971 diverted subjects and 995 non-diverted subjects were included in this evaluation; the research found only modest differences in the receipt of services and treatment at 3- and 12-months follow-up. For example, at the 3-month interview, 26% of both groups reported receiving substance abuse counseling, and at the 12-month interview, 0.7% of those diverted versus no non-diverted participant received two or more substance abuse counseling sessions. At 3 months, 38% of the diverted subjects and 30% of the non-diverted reported mental health counseling versus 41% and 38% at 12 months, respectively.

The service needs expressed by these individuals reflect their lack of education, job experience, vocational skills, and life skills, as well as the substance abuse and mental health issues identified among justice-involved individuals. The intervention response to these needs is reflected in the variety of services prescribed in the typical “reentry program bucket.” These involve the services and programs shown in Fig. 10 , as well as case management and reentry planning to coordinate services with respect to needs.

The identification of needs followed by efforts to meet those needs underlies the Risk-Needs-Responsivity (RNR) approach to addressing justice-involved populations (e.g., Andrews & Bonta, 1994 , 2006 ; Latessa, 2020 ). The RNR approach to addressing criminal behavior is premised on the assumption that if you address identified needs that are correlated with criminal behavior, that behavior will be reduced. In other words, recidivism can be addressed by providing individuals the education and job skills and treatment they need to find gainful employment, reduce substance use, and mitigate symptoms of mental illness. Latessa ( 2020 ) recently discussed the RNR approach, reiterating the importance of assessing individual criminogenic and non-criminogenic needs to improve reentry programs. He also reiterated the importance of focusing resources on those identified as high (or higher) risk by actuarial risk assessment instruments—pointing to important work he conducted with colleagues that found that interventions reduced recidivism among high-risk individuals and increased it among low-risk individuals (Lowenkamp & Latessa, 2002 ; Latessa et al., 2010 ). This approach to reentry programming is reflected in the requirements of most federal grants—like the SVORI and SCA—that require programs to incorporate reentry planning that includes needs assessment and services that address criminogenic and non-criminogenic needs.

As noted, most justice-involved individuals have limited education and few job skills, and many have behavioral health issues, anger management issues, and limited life skills. But if addressing these deficits is the key to successfully rehabilitating large numbers of individuals caught in the carceral and community justice system, the meager results of recent research suggests two possibilities. First, this is the right approach, but poor or incomplete implementation has so far impeded findings of substantial effects (a common conclusion since the Martinson report). Second, alternatively, this approach is wrong (or insufficient), and new thinking about the “what and how” of rehabilitative programming is needed. I address the second idea next and turn to the first idea shortly.

MacKenzie ( 2006 ) and others (e.g., Andrews and Bonta, 2006 ; Andrews et al., 1990 ; Aos et al., 2006 ; Lipsey, 1995 ; Lipsey & Cullen, 2007 ) have stressed that programs focused on individual change have been found to be effective more often than those providing practical services. The SVORI evaluation also found support for this conclusion. Services we classified as “practical” (e.g., case manager, employment services, life skills, needs assessment, reentry planning, and reentry program) were associated with either no or a deleterious impact on arrest chances—although few were statistically different from a null effect. Individual-change services (e.g., anger management, programs for criminal attitudes including cognitive behavior therapy, education, help with personal relationships, and substance abuse treatment) were associated with positive impacts on arrest. The original SVORI evaluation had a follow-up period of about 2 years and findings suggested that the overall impact of SVORI program participation on rearrest and reincarceration were positive but not statistically significant. In contrast to these findings, a longer follow-up that extended at least 56 months showed participation in SVORI programs was associated with longer times to arrest and fewer arrests after release for both men and women. For the men, SVORI program participation was associated with a longer time to reincarceration and fewer reincarcerations, although the latter result was not statistically significant ( p = 0.18). For the women, the reincarceration results were mixed and not significant.

Support for positive impacts of programs focused on individual change are consistent with theories associated with identity transformation and desistance from criminal activity. Bushway ( 2020 ) has recently discussed two alternative views of desistance, contrasting the implications of desistance either as a process (i.e., the gradual withdrawal from criminal activity) or reflective of an identify shift towards a more prosocial identity. In examining these two ideas, Bushway posits that the second suggests that individuals with a history of a high rate of offending may simply stop (as opposed to reducing the frequency of criminal acts). If individuals do (or can or will) stop, the implication is clear: policies that focus on an individual’s criminal history (e.g., for employment or parole decisions) may fail to recognize that the individual has changed. This change may be evidenced by in-prison good behavior (e.g., completing programs and staying out of trouble) or positive steps following release (e.g., actively seeking meaningful employment or engaging in positive relationships). Tellingly, Bushway ( 2020 ) notes: “Individuals involved in crime get information about how they are perceived by others through their involvement in the criminal justice system. Formal labels of ‘criminal’ are assigned and maintained by the criminal justice system. As a result, identity models are much more consistent theoretically with an empirical approach that revolves around measures of criminal justice involvement rather than criminal offending per se.” He goes on to discuss the relationship of identity-based models of stark breaks and criminal career models. In short, reflecting insights that labeling theorists have long emphasized, the labels the criminal justice system and society place on individuals may impede the desistance process that is the supposed goal of the system.

The second consideration are concerns about program design and implementation—What is the underlying logic model or theory of change? Is there adequate time to develop the program and train staff to implement it appropriately? Is the resulting program implemented with fidelity? The two or three years usually provided to implement complex programs suggest that these goals are unlikely to be met. The “notorious” findings of Martinson (1975) that “nothing works” was more appropriately interpreted as “nothing was implemented.” Unfortunately, nearly 50 years later, we largely observe something similar—not “nothing” but “something” that is far short of what was intended.

As discussed in detail by Taxman (2020), the usual approach to program development and testing skips over important formative steps, doesn’t allow time for pilot testing, and provides little opportunity for staff training or for achievement and maintenance of program fidelity (if there is even a program logic model). From an evaluator’s perspective, this short timeline imposes multiple challenges. An evaluator must identify study participants (and control or comparison subjects), follow them largely while they are in the program, and hope to have at least one year of post-program follow-up—generally without being able to accommodate the impact of likely weak implementation on evaluation power to detect effects.

Thus, it may not be surprising that effects are generally small. However, these small effects may not be negligible from a public safety perspective. In a study of the effects of non-residential drug treatment for a cohort of probationers, Lattimore et al. ( 2005a ) found that treatment reduced the number of probationers with a felony arrest by 23% during the first year and 11% over the first two years. The total number of arrests was also reduced by 17% over 12 months and 14% over 24 months. “Back of the envelope” calculations suggested that if treatment cost $1,000 per individual, it would have been cost effective to provide treatment to all members of the cohort as long as the (average) cost of arrest (and all related criminal justice processing and corrections) exceeds about $6,463.

Another example is to consider that the impact of a treatment effect in the 10% range applied across all prison releases would imply the aversion of many crimes. For example, assuming 750,000 prison releases each year over a five-year period and a 66% rearrest rate within 3 years (and no additional arrests after 3 years), then 3.75 million prisoners will be released over the five years; of these individuals, 2.475 million will be arrested at least once during the three years following release. A 10% reduction in first-time rearrests would mean 247,500 fewer first-time rearrests. To the extent that many offenders are arrested multiple times, this figure represents a lower bound on the number of averted arrests. A similar analysis could be conducted assuming 2,000,000 probation admissions each year and a 39% rearrest rate within 3 years. In this case, there would be 10,000,000 probation admissions that would generate 3.9 million first-time arrests over the three years after admission to probation. A 10% reduction in first-time rearrests would mean 390,000 fewer arrests. In total, therefore, reducing recidivism—as measured by rearrest by 10% for these hypothetical correctional populations—would translate into 637,500 averted arrests. Extrapolating further and assuming that roughly 10% of the arrests were for violent crime and 90% for property crime, and applying the inverse of the crime clearance rates for these two types of crime to generate a “crimes averted” count, we find that a 10% reduction in recidivism for these two populations would translate into 140,110 violent and 3,519,939 property crimes averted. 22 Thus, “modest” improvements in recidivism may provide substantial public benefits—in crimes averted, and lower demands on law enforcement, prosecution, and correctional resources. 23

The third consideration is the adequacy of the evaluation methods we routinely apply to this complex problem of inadequate interventions that are partially and sometimes poorly implemented. At minimum, we need to explicitly recognize the impacts of the following:

- Programs partially implemented and partially treated control conditions.

- Recidivism outcomes conditioned on an intermediate outcome.

- Follow-up periods too short to accommodate short-term failure followed by long-term success.

- Focusing on a binary indicator of recidivism ignores frequency and seriousness of offending.

The impact of partial treatment of both treatment and control groups on effect sizes and the consequential impact on statistical power is seldom discussed—either in initial estimates of needed sample sizes or in subsequent discussions of findings. As shown earlier and is true for most justice evaluations, the control or comparison condition is almost never “nothing.” Instead, it is generally “business as usual” (BAU) that means whatever the current standard of treatment entails. Thus, the treatment group may receive some services that aren’t available to the control group, but in many cases both groups have access to specific services and programs although the treatment group may get priority.

As we saw in Fig. 10 , treatment was reported by some individuals in both the SVORI and non-SVORI groups. Table Table1 1 shows the implications of partial treatment using data from the SVORI evaluation. 24 The percent treated for the SVORI and non-SVORI men are shown in columns three and four. Column 2 presents the effect sizes for four interventions as identified by Wanner ( 2018 ). If we assume that the recidivism rate without treatment is 20%, 25 the observed recidivism rate for the SVORI and non-SVORI men as a result of receiving each treatment is shown in columns four and five. Column six shows that the observed differences in recidivism between the two groups in this “thought experiment” are less than two percent—an effect size that would never be detected with typical correctional program evaluations. 26

Hypothetical treatment effects with incomplete treatment of the treatment group and partial treatment of the comparison group, assuming untreated recidivism rate is 20 percent

* Estimates from Wanner ( 2018 ).

Similar findings emerge when considering the effects on recidivism of interventions such as job training programs that are intended to improve outcomes intermediate to recidivism. Consider the hypothetical impact of a prison job training program on post-release employment and recidivism. The underlying theory of change is that training will increase post-release employment and having a job will reduce recidivism. 27 Suppose the job training program boosts post-release employment by 30% and that, without the program, 50% of released individuals will find a job. A 30% improvement means that 65% of program participants will find employment. Randomly assigning 100 of 200 individuals to receive the program would result in 50 of those in the control group and 65 of those in the treatment group to find employment. (This outcome assumes everyone in the treatment group receives treatment.) Table Table2 2 shows the treatment effect on recidivism under various assumptions about the impact of employment on recidivism. The table assumes a 50% recidivism rate for the unemployed so, e.g., if the effect of a job is to reduce recidivism by 10% employed individuals will have a recidivism rate of 45%. If there is no effect—i.e., recidivism is independent of being employed—we observe 50% failure for both groups and there is no effect on recidivism rates even if the program is successful at increasing employment by 30%. On the other hand, if being employed eliminates recidivism, no one who is employed will be recidivists and 50% of those unemployed will be recidivists—or 25 of the control group and 17.5 of the treated group. The last column in Table Table2 2 shows the conditional effect of job training on recidivism under the various effects of employment on recidivism shown in column 1. The effects shown in the last column are the same regardless of the assumption about the recidivism rate of the unemployed. So, employment must have a very substantial effect on the recidivism rate to result in a large effect on the observed recidivism rate when, as is reasonable to assume, some members of the control group who didn’t have the training will find employment. As before, this finding underscores the need to carefully consider the mechanism affecting recidivism and potential threats to effect sizes and statistical power.

Hypothetical effects of job training on employment and recidivism assuming job training increases employment by 30% and control (untreated) employment is 50%

A third concern is that follow-up periods which typically are 2 years or less may be too short to observe positive impacts of interventions (Lattimore & Visher, 2020). Although this may seem counterintuitive, it is what was observed for the SVORI multisite evaluation. The initial SVORI evaluation focused on the impact of participation with at least 21 months of follow-up following release from prison and showed positive but insignificant differences in rearrests for the SVORI and non-SVORI groups. A subsequent NIJ award provided funding for a long-term (at least 56 months) examination of recidivism for 11 of the 12 adult programs (Visher et al., 2017 ; also see Lattimore et al., 2012 ). In contrast to the findings in the original study, participation in SVORI programs was associated with longer times to arrest and fewer arrests after release for both men and women during the extended follow-up period of at least 56 months. Although untestable post hoc, one plausible hypothesis is that the early period following release is chaotic for many individuals leaving prison and failure is likely. Only after the initial “settling out period” are individuals in a position to take advantage of what was learned during program participation. In any event, these findings suggest the need to conduct more, longer-term evaluations of reentry programs.

A final consideration is the indicator of recidivism used to judge the success of a program. Recidivism, which is a return to criminal behavior, is almost never observed. Instead, researchers and practitioners rely on proxies that are measures of justice system indicators that a crime has occurred—arrest, conviction, and incarceration for new offenses—and, for those on supervision, violation of conditions and revocation of supervision. A recent National Academy of Sciences’ publication ( 2022 ) highlights some of the limitations of recidivism as a measure of post-release outcomes, arguing that indicators of success and measures that allow for the observation of desisting behavior (defined by the panel as a process—not the sharp break advanced by Bushway) should be used instead. These are valid points but certainly in the short run the funders of interventions and those responsible for public safety are unlikely to be willing to ignore new criminal activity as an outcome.

It is worth highlighting, however, some of the limitations of the binary indicator of any new event that is the usual measure adopted by many researchers (e.g., “any new arrest within x years”) and practitioners (e.g., “return to our Department within 3 years”). These simple measures ignore important dimensions of recidivism. These include type of offense (e.g., violent, property, drug), seriousness of offense (e.g., homicide, felony assault, misdemeanor assault), and frequency of offending (equivalent to time to the recidivism event). As a result, a typical recidivism outcome treats as identical minor acts committed, e.g., 20 months following release, and serious crimes committed immediately. Note too that this binary indicator fails in terms of being able to recognize desisting behavior, that is, where time between events increases or the seriousness of the offense decreases. Survival methods and count or event models address the frequency consideration. Competing hazard models allow one to examine differences between a few categories of offending (e.g., violent, property, drug, other). The only approach that appears to have tackled the seriousness dimension is the work by Sherman and colleagues (Sherman et al., 2016 ; also, see www.crim.cam.ac.uk/research/thecambridgecrimeharminde ) who have developed a Crime Harm Index that is based on potential sentences for non-victimless crimes. To date, statistical methods that can accommodate the three dimensions simultaneously do not, to my knowledge, exist. At a minimum, however, researchers should use the methods that are available to fully explore their recidivism outcomes. Logistic regression models are easy to estimate and the results are easily interpretable. But an intervention may be useful if it increases the time to a new offense or reduces the seriousness of new criminal behavior.