Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a literary analysis essay | A step-by-step guide

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on January 30, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on August 14, 2023.

Literary analysis means closely studying a text, interpreting its meanings, and exploring why the author made certain choices. It can be applied to novels, short stories, plays, poems, or any other form of literary writing.

A literary analysis essay is not a rhetorical analysis , nor is it just a summary of the plot or a book review. Instead, it is a type of argumentative essay where you need to analyze elements such as the language, perspective, and structure of the text, and explain how the author uses literary devices to create effects and convey ideas.

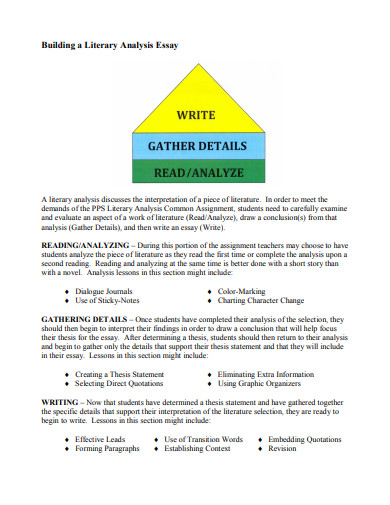

Before beginning a literary analysis essay, it’s essential to carefully read the text and c ome up with a thesis statement to keep your essay focused. As you write, follow the standard structure of an academic essay :

- An introduction that tells the reader what your essay will focus on.

- A main body, divided into paragraphs , that builds an argument using evidence from the text.

- A conclusion that clearly states the main point that you have shown with your analysis.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: reading the text and identifying literary devices, step 2: coming up with a thesis, step 3: writing a title and introduction, step 4: writing the body of the essay, step 5: writing a conclusion, other interesting articles.

The first step is to carefully read the text(s) and take initial notes. As you read, pay attention to the things that are most intriguing, surprising, or even confusing in the writing—these are things you can dig into in your analysis.

Your goal in literary analysis is not simply to explain the events described in the text, but to analyze the writing itself and discuss how the text works on a deeper level. Primarily, you’re looking out for literary devices —textual elements that writers use to convey meaning and create effects. If you’re comparing and contrasting multiple texts, you can also look for connections between different texts.

To get started with your analysis, there are several key areas that you can focus on. As you analyze each aspect of the text, try to think about how they all relate to each other. You can use highlights or notes to keep track of important passages and quotes.

Language choices

Consider what style of language the author uses. Are the sentences short and simple or more complex and poetic?

What word choices stand out as interesting or unusual? Are words used figuratively to mean something other than their literal definition? Figurative language includes things like metaphor (e.g. “her eyes were oceans”) and simile (e.g. “her eyes were like oceans”).

Also keep an eye out for imagery in the text—recurring images that create a certain atmosphere or symbolize something important. Remember that language is used in literary texts to say more than it means on the surface.

Narrative voice

Ask yourself:

- Who is telling the story?

- How are they telling it?

Is it a first-person narrator (“I”) who is personally involved in the story, or a third-person narrator who tells us about the characters from a distance?

Consider the narrator’s perspective . Is the narrator omniscient (where they know everything about all the characters and events), or do they only have partial knowledge? Are they an unreliable narrator who we are not supposed to take at face value? Authors often hint that their narrator might be giving us a distorted or dishonest version of events.

The tone of the text is also worth considering. Is the story intended to be comic, tragic, or something else? Are usually serious topics treated as funny, or vice versa ? Is the story realistic or fantastical (or somewhere in between)?

Consider how the text is structured, and how the structure relates to the story being told.

- Novels are often divided into chapters and parts.

- Poems are divided into lines, stanzas, and sometime cantos.

- Plays are divided into scenes and acts.

Think about why the author chose to divide the different parts of the text in the way they did.

There are also less formal structural elements to take into account. Does the story unfold in chronological order, or does it jump back and forth in time? Does it begin in medias res —in the middle of the action? Does the plot advance towards a clearly defined climax?

With poetry, consider how the rhyme and meter shape your understanding of the text and your impression of the tone. Try reading the poem aloud to get a sense of this.

In a play, you might consider how relationships between characters are built up through different scenes, and how the setting relates to the action. Watch out for dramatic irony , where the audience knows some detail that the characters don’t, creating a double meaning in their words, thoughts, or actions.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

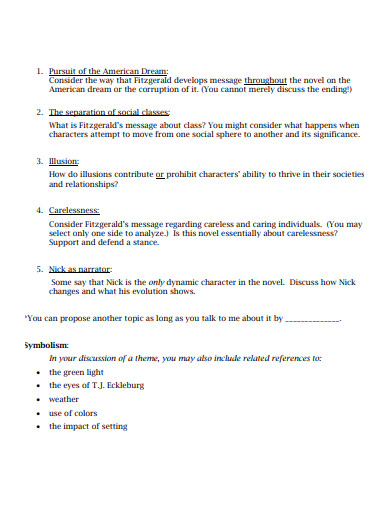

Your thesis in a literary analysis essay is the point you want to make about the text. It’s the core argument that gives your essay direction and prevents it from just being a collection of random observations about a text.

If you’re given a prompt for your essay, your thesis must answer or relate to the prompt. For example:

Essay question example

Is Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” a religious parable?

Your thesis statement should be an answer to this question—not a simple yes or no, but a statement of why this is or isn’t the case:

Thesis statement example

Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” is not a religious parable, but a story about bureaucratic alienation.

Sometimes you’ll be given freedom to choose your own topic; in this case, you’ll have to come up with an original thesis. Consider what stood out to you in the text; ask yourself questions about the elements that interested you, and consider how you might answer them.

Your thesis should be something arguable—that is, something that you think is true about the text, but which is not a simple matter of fact. It must be complex enough to develop through evidence and arguments across the course of your essay.

Say you’re analyzing the novel Frankenstein . You could start by asking yourself:

Your initial answer might be a surface-level description:

The character Frankenstein is portrayed negatively in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein .

However, this statement is too simple to be an interesting thesis. After reading the text and analyzing its narrative voice and structure, you can develop the answer into a more nuanced and arguable thesis statement:

Mary Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as.

Remember that you can revise your thesis statement throughout the writing process , so it doesn’t need to be perfectly formulated at this stage. The aim is to keep you focused as you analyze the text.

Finding textual evidence

To support your thesis statement, your essay will build an argument using textual evidence —specific parts of the text that demonstrate your point. This evidence is quoted and analyzed throughout your essay to explain your argument to the reader.

It can be useful to comb through the text in search of relevant quotations before you start writing. You might not end up using everything you find, and you may have to return to the text for more evidence as you write, but collecting textual evidence from the beginning will help you to structure your arguments and assess whether they’re convincing.

To start your literary analysis paper, you’ll need two things: a good title, and an introduction.

Your title should clearly indicate what your analysis will focus on. It usually contains the name of the author and text(s) you’re analyzing. Keep it as concise and engaging as possible.

A common approach to the title is to use a relevant quote from the text, followed by a colon and then the rest of your title.

If you struggle to come up with a good title at first, don’t worry—this will be easier once you’ve begun writing the essay and have a better sense of your arguments.

“Fearful symmetry” : The violence of creation in William Blake’s “The Tyger”

The introduction

The essay introduction provides a quick overview of where your argument is going. It should include your thesis statement and a summary of the essay’s structure.

A typical structure for an introduction is to begin with a general statement about the text and author, using this to lead into your thesis statement. You might refer to a commonly held idea about the text and show how your thesis will contradict it, or zoom in on a particular device you intend to focus on.

Then you can end with a brief indication of what’s coming up in the main body of the essay. This is called signposting. It will be more elaborate in longer essays, but in a short five-paragraph essay structure, it shouldn’t be more than one sentence.

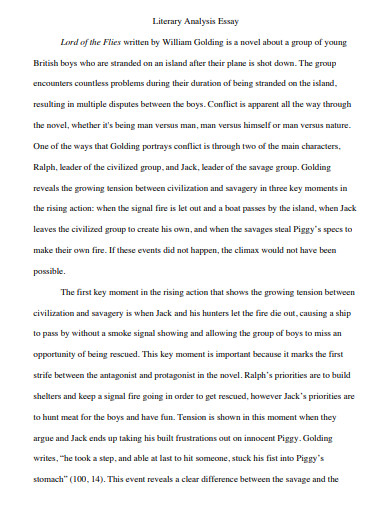

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific advancement unrestrained by ethical considerations. In this reading, protagonist Victor Frankenstein is a stable representation of the callous ambition of modern science throughout the novel. This essay, however, argues that far from providing a stable image of the character, Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as. This essay begins by exploring the positive portrayal of Frankenstein in the first volume, then moves on to the creature’s perception of him, and finally discusses the third volume’s narrative shift toward viewing Frankenstein as the creature views him.

Some students prefer to write the introduction later in the process, and it’s not a bad idea. After all, you’ll have a clearer idea of the overall shape of your arguments once you’ve begun writing them!

If you do write the introduction first, you should still return to it later to make sure it lines up with what you ended up writing, and edit as necessary.

The body of your essay is everything between the introduction and conclusion. It contains your arguments and the textual evidence that supports them.

Paragraph structure

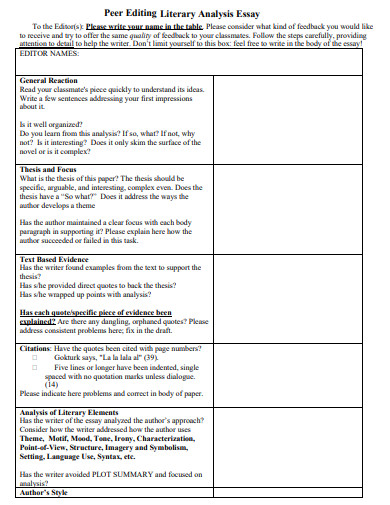

A typical structure for a high school literary analysis essay consists of five paragraphs : the three paragraphs of the body, plus the introduction and conclusion.

Each paragraph in the main body should focus on one topic. In the five-paragraph model, try to divide your argument into three main areas of analysis, all linked to your thesis. Don’t try to include everything you can think of to say about the text—only analysis that drives your argument.

In longer essays, the same principle applies on a broader scale. For example, you might have two or three sections in your main body, each with multiple paragraphs. Within these sections, you still want to begin new paragraphs at logical moments—a turn in the argument or the introduction of a new idea.

Robert’s first encounter with Gil-Martin suggests something of his sinister power. Robert feels “a sort of invisible power that drew me towards him.” He identifies the moment of their meeting as “the beginning of a series of adventures which has puzzled myself, and will puzzle the world when I am no more in it” (p. 89). Gil-Martin’s “invisible power” seems to be at work even at this distance from the moment described; before continuing the story, Robert feels compelled to anticipate at length what readers will make of his narrative after his approaching death. With this interjection, Hogg emphasizes the fatal influence Gil-Martin exercises from his first appearance.

Topic sentences

To keep your points focused, it’s important to use a topic sentence at the beginning of each paragraph.

A good topic sentence allows a reader to see at a glance what the paragraph is about. It can introduce a new line of argument and connect or contrast it with the previous paragraph. Transition words like “however” or “moreover” are useful for creating smooth transitions:

… The story’s focus, therefore, is not upon the divine revelation that may be waiting beyond the door, but upon the mundane process of aging undergone by the man as he waits.

Nevertheless, the “radiance” that appears to stream from the door is typically treated as religious symbolism.

This topic sentence signals that the paragraph will address the question of religious symbolism, while the linking word “nevertheless” points out a contrast with the previous paragraph’s conclusion.

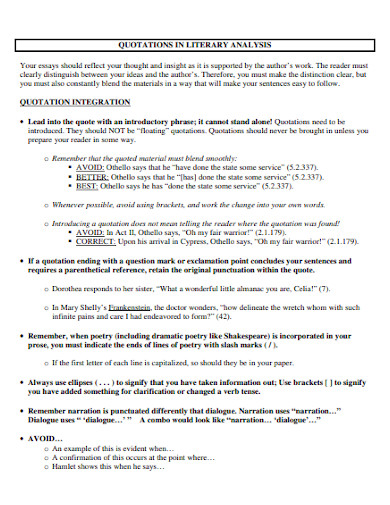

Using textual evidence

A key part of literary analysis is backing up your arguments with relevant evidence from the text. This involves introducing quotes from the text and explaining their significance to your point.

It’s important to contextualize quotes and explain why you’re using them; they should be properly introduced and analyzed, not treated as self-explanatory:

It isn’t always necessary to use a quote. Quoting is useful when you’re discussing the author’s language, but sometimes you’ll have to refer to plot points or structural elements that can’t be captured in a short quote.

In these cases, it’s more appropriate to paraphrase or summarize parts of the text—that is, to describe the relevant part in your own words:

The conclusion of your analysis shouldn’t introduce any new quotations or arguments. Instead, it’s about wrapping up the essay. Here, you summarize your key points and try to emphasize their significance to the reader.

A good way to approach this is to briefly summarize your key arguments, and then stress the conclusion they’ve led you to, highlighting the new perspective your thesis provides on the text as a whole:

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

By tracing the depiction of Frankenstein through the novel’s three volumes, I have demonstrated how the narrative structure shifts our perception of the character. While the Frankenstein of the first volume is depicted as having innocent intentions, the second and third volumes—first in the creature’s accusatory voice, and then in his own voice—increasingly undermine him, causing him to appear alternately ridiculous and vindictive. Far from the one-dimensional villain he is often taken to be, the character of Frankenstein is compelling because of the dynamic narrative frame in which he is placed. In this frame, Frankenstein’s narrative self-presentation responds to the images of him we see from others’ perspectives. This conclusion sheds new light on the novel, foregrounding Shelley’s unique layering of narrative perspectives and its importance for the depiction of character.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, August 14). How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved March 27, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/literary-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to write a narrative essay | example & tips, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

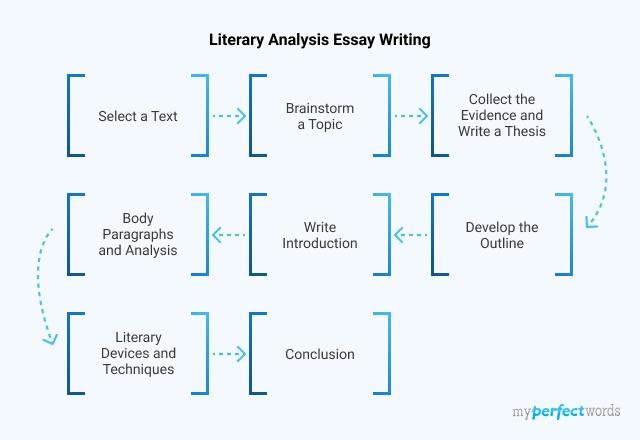

Literary Analysis Essay Writing

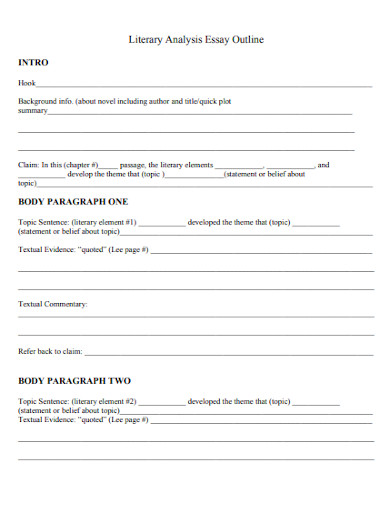

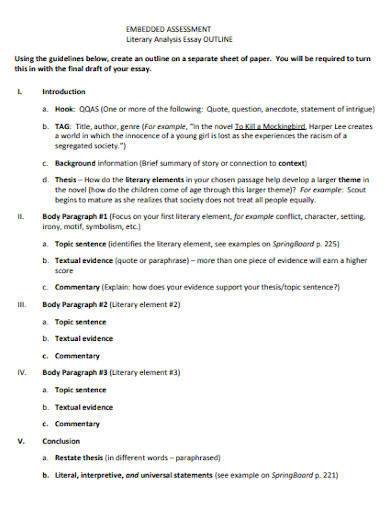

Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Literary Analysis Essay Outline - A Step By Step Guide

People also read

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay - A Step-by-Step Guide

Interesting Literary Analysis Essay Topics & Ideas

Have you ever felt stuck, looking at a blank page, wondering what a literary analysis essay is? You are not sure how to analyze a complicated book or story?

Writing a literary analysis essay can be tough, even for people who really love books. The hard part is not only understanding the deeper meaning of the story but also organizing your thoughts and arguments in a clear way.

But don't worry!

In this easy-to-follow guide, we will talk about a key tool: The Literary Analysis Essay Outline.

We'll provide you with the knowledge and tricks you need to structure your analysis the right way. In the end, you'll have the essential skills to understand and structure your literature analysis better. So, let’s dive in!

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

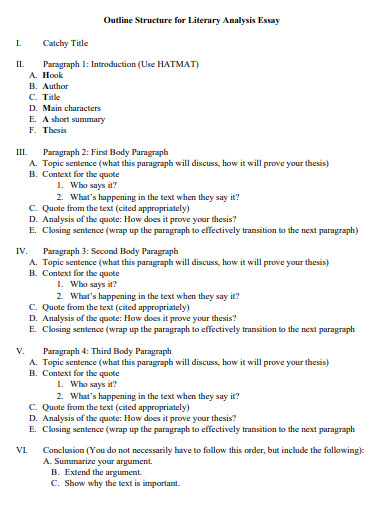

- 1. How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay Outline?

- 2. Literary Analysis Essay Format

- 3. Literary Analysis Essay Outline Example

- 4. Literary Analysis Essay Topics

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay Outline?

An outline is a structure that you decide to give to your writing to make the audience understand your viewpoint clearly. When a writer gathers information on a topic, it needs to be organized to make sense.

When writing a literary analysis essay, its outline is as important as any part of it. For the text’s clarity and readability, an outline is drafted in the essay’s planning phase.

According to the basic essay outline, the following are the elements included in drafting an outline for the essay:

- Introduction

- Thesis statement

- Body paragraphs

A detailed description of the literary analysis outline is provided in the following section.

Literary Analysis Essay Introduction

An introduction section is the first part of the essay. The introductory paragraph or paragraphs provide an insight into the topic and prepares the readers about the literary work.

A literary analysis essay introduction is based on three major elements:

Hook Statement: A hook statement is the opening sentence of the introduction. This statement is used to grab people’s attention. A catchy hook will make the introductory paragraph interesting for the readers, encouraging them to read the entire essay.

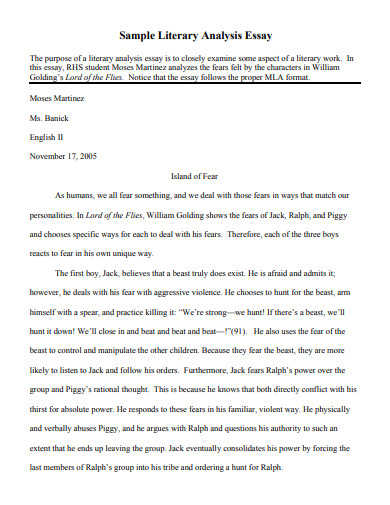

For example, in a literary analysis essay, “ Island Of Fear,” the writer used the following hook statement:

“As humans, we all fear something, and we deal with those fears in ways that match our personalities.”

Background Information: Providing background information about the chosen literature work in the introduction is essential. Present information related to the author, title, and theme discussed in the original text.

Moreover, include other elements to discuss, such as characters, setting, and the plot. For example:

“ In Lord of the Flies, William Golding shows the fears of Jack, Ralph, and Piggy and chooses specific ways for each to deal with his fears.”

Thesis Statement: A thesis statement is the writer’s main claim over the chosen piece of literature.

A thesis statement allows your reader to expect the purpose of your writing. The main objective of writing a thesis statement is to provide your subject and opinion on the essay.

For example, the thesis statement in the “Island of Fear” is:

“...Therefore, each of the three boys reacts to fear in his own unique way.”

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

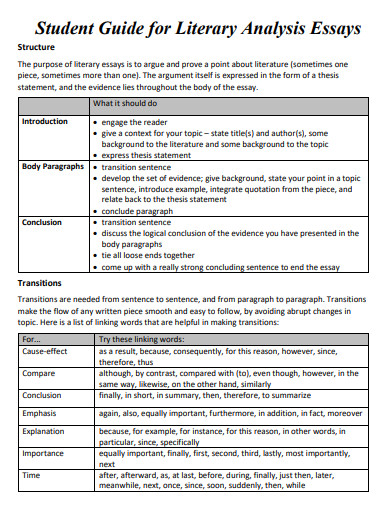

Literary Analysis Essay Body Paragraphs

In body paragraphs, you dig deep into the text, show your insights, and build your argument.

In this section, we'll break down how to structure and write these paragraphs effectively:

Topic sentence: A topic sentence is an opening sentence of the paragraph. The points that will support the main thesis statement are individually presented in each section.

For example:

“The first boy, Jack, believes that a beast truly does exist…”

Evidence: To support the claim made in the topic sentence, evidence is provided. The evidence is taken from the selected piece of work to make the reasoning strong and logical.

“...He is afraid and admits it; however, he deals with his fear of aggressive violence. He chooses to hunt for the beast, arms himself with a spear, and practice killing it: “We’re strong—we hunt! If there’s a beast, we’ll hunt it down! We’ll close in and beat and beat and beat—!”(91).”

Analysis: A literary essay is a kind of essay that requires a writer to provide his analysis as well.

The purpose of providing the writer’s analysis is to tell the readers about the meaning of the evidence.

“...He also uses the fear of the beast to control and manipulate the other children. Because they fear the beast, they are more likely to listen to Jack and follow his orders...”

Transition words: Transition or connecting words are used to link ideas and points together to maintain a logical flow. Transition words that are often used in a literary analysis essay are:

- Furthermore

- Later in the story

- In contrast, etc.

“...Furthermore, Jack fears Ralph’s power over the group and Piggy’s rational thought. This is because he knows that both directly conflict with his thirst for absolute power...”

Concluding sentence: The last sentence of the body that gives a final statement on the topic sentence is the concluding sentence. It sums up the entire discussion held in that specific paragraph.

Here is a literary analysis paragraph example for you:

Literary Essay Example Pdf

Literary Analysis Essay Conclusion

The last section of the essay is the conclusion part where the writer ties all loose ends of the essay together. To write appropriate and correct concluding paragraphs, add the following information:

- State how your topic is related to the theme of the chosen work

- State how successfully the author delivered the message

- According to your perspective, provide a statement on the topic

- If required, present predictions

- Connect your conclusion to your introduction by restating the thesis statement.

- In the end, provide an opinion about the significance of the work.

For example,

“ In conclusion, William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies exposes the reader to three characters with different personalities and fears: Jack, Ralph, and Piggy. Each of the boys tries to conquer his fear in a different way. Fear is a natural emotion encountered by everyone, but each person deals with it in a way that best fits his/her individual personality.”

Literary Analysis Essay Outline (PDF)

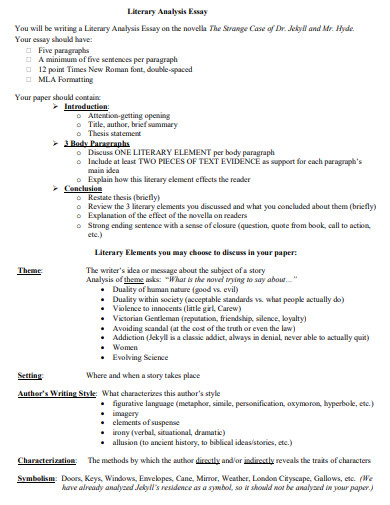

Literary Analysis Essay Format

A literary analysis essay delves into the examination and interpretation of a literary work, exploring themes, characters, and literary devices.

Below is a guide outlining the format for a structured and effective literary analysis essay.

Formatting Guidelines

- Use a legible font (e.g., Times New Roman or Arial) and set the font size to 12 points.

- Double-space your essay, including the title, headings, and quotations.

- Set one-inch margins on all sides of the page.

- Indent paragraphs by 1/2 inch or use the tab key.

- Page numbers, if required, should be in the header or footer and follow the specified formatting style.

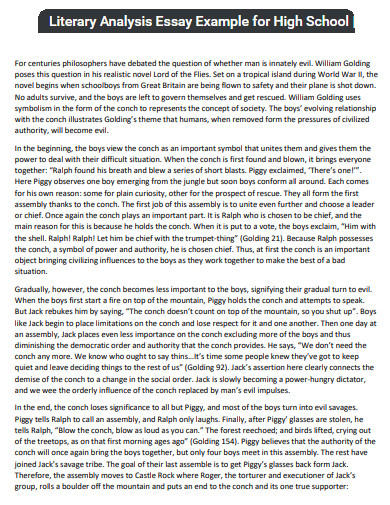

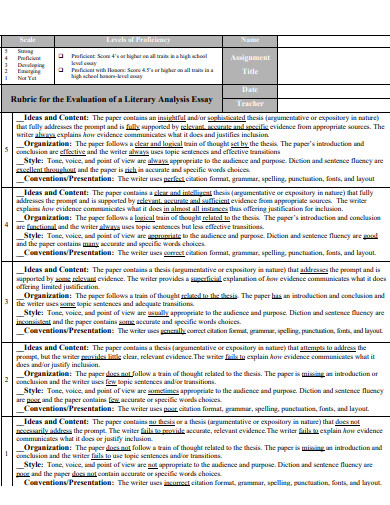

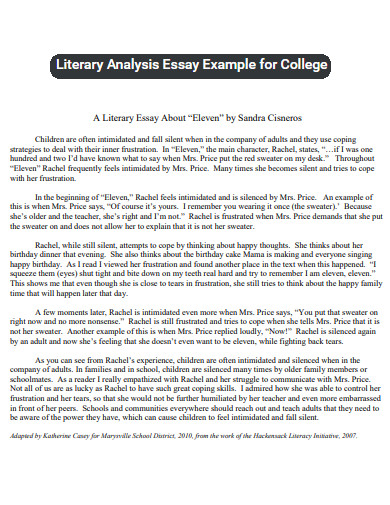

Literary Analysis Essay Outline Example

To fully understand a concept in a writing world, literary analysis outline examples are important. This is to learn how a perfectly structured writing piece is drafted and how ideas are shaped to convey a message.

The following are the best literary analysis essay examples to help you draft a perfect essay.

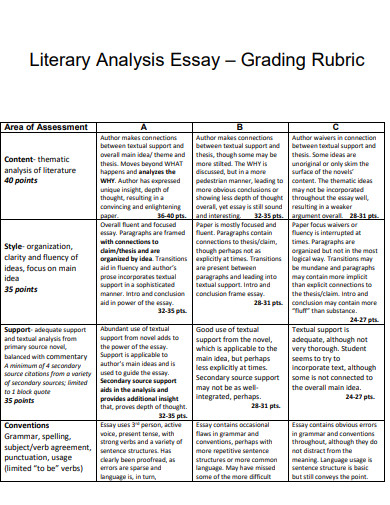

Literary Analysis Essay Rubric (PDF)

High School Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Literary Analysis Essay Outline College (PDF)

Literary Analysis Essay Example Romeo & Juliet (PDF)

AP Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Literary Analysis Essay Outline Middle School

Literary Analysis Essay Topics

Are you seeking inspiration for your next literary analysis essay? Here is a list of literary analysis essay topics for you:

- The Theme of Alienation in "The Catcher in the Rye"

- The Motif of Darkness in Shakespeare's Tragedies

- The Psychological Complexity of Hamlet's Character

- Analyzing the Narrator's Unreliable Perspective in "The Tell-Tale Heart"

- The Role of Nature in William Wordsworth's Romantic Poetry

- The Representation of Social Class in "To Kill a Mockingbird"

- The Use of Irony in Mark Twain's "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn"

- The Impact of Holden's Red Hunting Hat in the Novel

- The Power of Setting in Gabriel García Márquez's "One Hundred Years of Solitude"

- The Symbolism of the Conch Shell in William Golding's "Lord of the Flies"

Need more topics? Read our literary analysis essay topics blog!

All in all, writing a literary analysis essay can be tricky if it is your first attempt. Apart from analyzing the work, other elements like a topic and an accurate interpretation must draft this type of essay.

If you are in doubt to draft a perfect essay, get professional essay writing assistance from expert writers at MyPerfectWords.com.

We are a professional essay writing company that provides guidance and helps students to achieve their academic goals. Our qualified writers assist students by providing assistance at an affordable price.

So, why wait? Let us help you in achieving your academic goals!

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Cathy has been been working as an author on our platform for over five years now. She has a Masters degree in mass communication and is well-versed in the art of writing. Cathy is a professional who takes her work seriously and is widely appreciated by clients for her excellent writing skills.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Literary Analysis Essay

Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Literary Analysis Essay Outline Guide with Examples

Published on: Aug 22, 2020

Last updated on: Mar 25, 2024

People also read

Literary Analysis Essay - Step by Step Guide

Interesting Literary Analysis Essay Topics & Ideas

Share this article

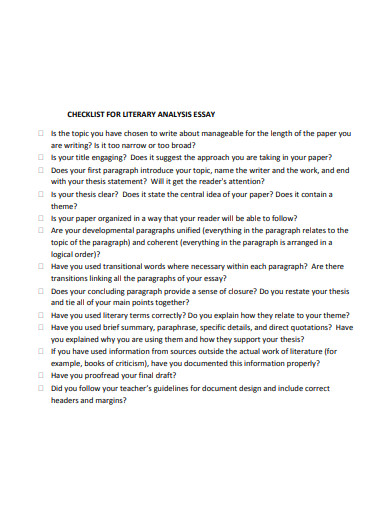

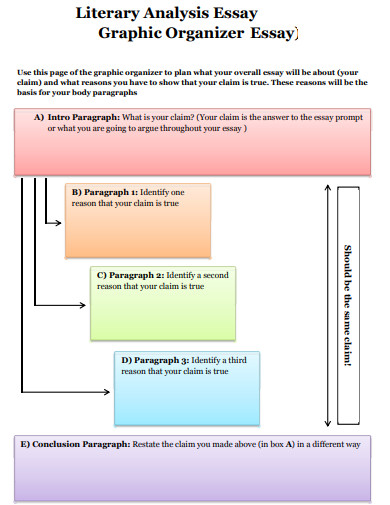

Writing a literary analysis essay may seem intimidating at first, but we're here to simplify the process for you. In this guide, we'll walk you through the steps of creating an effective outline that will enhance your writing and analytical abilities.

Whether you're a seasoned student or new to literary analysis, mastering the art of outlining will help you organize your thoughts and express your ideas with clarity and precision.

Let's dive in!

On This Page On This Page -->

The Basics of Literary Analysis Writing

Before diving into the specifics of the outline, let's grasp the fundamental elements of a literary analysis essay .

At its core, this type of essay requires a thoughtful examination and interpretation of a literary work. Whether it's a novel, poem, or play, the aim is to analyze the author's choices and convey your insights to the reader.

The Significance of an Outline

An outline is important for two reasons: It helps you organize your ideas and allows readers to follow along easily.

Think of it as a map for your essay. Without structure, essays can be confusing. By using an outline, you ensure that your writing is clear and logical, keeping both you and your readers on track.

Literary Analysis Essay Format

Letâs take a look at the specific and detailed format and how to write a literary analysis essay outline in simple steps:

Outline Ideas for Literary Analysis Essay

Here are sample templates for each of the outlined ideas for a literary analysis essay:

Five Paragraph Essay

This format is a traditional structure for organizing essays and is often taught in schools. It consists of an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Each body paragraph focuses on one main point or argument.

MLA Formatted Graphic Organizer

This format is designed to help organize your ideas according to the Modern Language Association (MLA) formatting guidelines. It ensures that your essay is properly structured and formatted according to MLA standards.

Compare and Contrast Essay on Two Texts

This format compares and contrasts two texts, highlighting similarities and differences. This is a common method used to analyze literature. There are two common methods: point by point and block method.

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Literary Analysis Essay Examples Outline

Letâs take a look at the literary analysis essay outline examples in easily downloadable PDF format:

Literary Analysis Essay Outline Middle School

Literary Analysis Outline Graphic Organizer

Critical Analysis Essay Outline Example

Character Analysis Essay Outline

Literary Analysis Essay Topics

Here are some literary analysis essay topics you can take inspiration from:

- Analyze the corrupting influence of power in Shakespeare's "Macbeth."

- Explore the symbolism of the green light in "The Great Gatsby" and its connection to the American Dream.

- Examine Holden Caulfield's journey of self-discovery and identity in "The Catcher in the Rye."

- Understand the use of magical realism in "One Hundred Years of Solitude" and its reflection of Latin American culture.

- Unravel the impact of race, class, and social hierarchy on moral justice in "To Kill a Mockingbird."

- Investigate feminist themes and gender roles in "Jane Eyre": Independence, equality, and the quest for autonomy.

- Examine the theme of fate versus free will in Sophocles' "Oedipus Rex" and its tragic consequences.

- Analyze the allegorical critique of totalitarianism in George Orwell's "Animal Farm."

- Explore survival and resilience in "Life of Pi" through the protagonist's journey of faith and self-discovery.

- Understand existential themes in "The Stranger": Absurdity, alienation, and the search for meaning in an indifferent world.

Need more topic ideas? Check out our â literary analysis essay topics â blog and get unique ideas for your next assignment.

In conclusion, crafting a literary analysis essay outline is a critical step in the writing process. By breaking down the essay into manageable sections and organizing your thoughts effectively, you'll create a compelling and insightful analysis that engages your readers.

Remember, practice makes perfect, so don't hesitate to revise and refine your outline until it reflects your ideas cohesively.

In case you are running out of time you can reach out to our essay writing service. At CollegeEssay.org , we provide high-quality college essay writing help for various literary topics. We have an extensive and highly professional team of qualified writers who are available to work on your assignments 24/7.

Get in touch with our customer service representative and let them know all your requirements.

Also, do not forget to try our AI writing tool !

Barbara P (Literature, Marketing)

Barbara is a highly educated and qualified author with a Ph.D. in public health from an Ivy League university. She has spent a significant amount of time working in the medical field, conducting a thorough study on a variety of health issues. Her work has been published in several major publications.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Terms of Use

- Refunds & Cancellations

- Our Writers

- Success Stories

- Our Guarantees

- Affiliate Program

- Referral Program

- AI Essay Writer

Disclaimer: All client orders are completed by our team of highly qualified human writers. The essays and papers provided by us are not to be used for submission but rather as learning models only.

Literary Analysis Essay

Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Last updated on: May 21, 2023

Write a Perfect Literary Analysis Essay Outline

By: Cordon J.

Reviewed By: Rylee W.

Published on: Jan 25, 2022

Writing a great essay can seem daunting. The best way to make your writing more interesting is by making sure that every word counts. Also, the structure becomes important for a good essay. All parts must include appropriately--but it's worth spending time wisely.

The importance of understanding the different types of essays is essential for all students. A literary analysis essay allows the essay writer to analyze the piece of literature. Also, understand the author's thoughts, feelings, and ideas that are expressed in it.

Its main goal is to explore the written work further. With the help of this type of essay, students know how to examine different parts of the text.

To write a good essay, you need to have an outline. An outline will help provide a proper framework for your work; also guide readers through what they're reading. It will also make your writing process easy and fast.

This blog will teach how to write an effective literary essay outline. So, continue reading this blog and get complete information about it.

On this Page

What is a Literary Analysis Essay Outline?

An outline is the most important thing in writing a literary analysis essay. To make writing readable and engaging for readers, writers often use an outline. An outline organizationally distributes information in a way that helps them convince people about what they believe.

One of the most enjoyable forms of essays is a "literary analysis" essay. Analyze a novel; it’s critical to know what each detail means. This kind of writing often includes an outline that helps students organize their thoughts and ideas. Find deeper meaning in books they read for pleasure or study purposes.

In order to create an engaging piece of work that leaves your audience wanting more, you should create a proper outline.

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay Outline?

The outline is a very important part of your essay. It should be planned and organized to help you with:

- Comprehension

- Organization

- The Flow of Ideas

The first step to writing a good literary analysis essay outline is understanding the information you need for your essay. You must include the necessary details, so it makes sense for someone to read your essay. They know what topic you discuss and what you are trying to say in your essay.

An outline is important when writing an analysis essay, especially for longer pieces of work. It's always best to have a plan in place that will help you stay on track with your writing.

Three main elements need to be included when writing the literary essay outline, such as:

- Literary Analysis Essay Introduction

- Literary Analysis Essay Body Paragraphs

- Literary Analysis Essay Conclusion

Let’s discuss them in detail.

1. Literary Analysis Essay Introduction

The introductory paragraph is the first thing that catches your reader’s attention in an essay. It should be creative and attention-grabbing. Though not too boring or technical for someone who isn't familiar with what you're writing about.

The introduction is an essential part of any written work. It provides the reader with information about what they will be reading and why it’s interesting for them.

Writing a successful analysis essay begins with figuring out how you want your essay to start. In most cases, this starts by posing an important question that is answered through the thesis statement.

When you are writing an introduction, it is important to start with the hook statement. A good way of doing this would be by starting your opening sentence in an interesting manner that entices readership. And has them interested from their first line all along through what will come next.

The thesis statement is the essence of an entire essay. It should summarize what your entire essay will contain and be written in very simple language that anyone can understand. Also, it should include persuasive tactics to get people on board with agreeing with you.

The best way to write an engaging analysis is by making sure that your thesis statement and background information are short. Your intro should be one paragraph, but it could contain up to five important sentences.

2. Literary Analysis Essay Body Paragraphs

When you finish writing the introduction, move on to start writing body paragraphs. The body paragraphs are the main building blocks of your essay. They provide detailed information about the chosen literary analysis essay topic. And help hold it together by presenting ideas about what you believe to be analyzed in a novel, movie, book, etc.

The body of an essay typically consists of three paragraphs. Each paragraph starts with a topic sentence that presents an interesting idea from literature. Also, it is related to both overall contexts and the specific thesis statement. Textual evidence is used to provide evidence for the topic sentence.

Make sure that you do not drag out any unnecessary data, as it will make your essay extraneous. Instead, stick to the point and only mention relevant information to avoid being boring. Use literary devices and make the essay body paragraphs more interesting.

When writing the essay body paragraphs, make sure that your essay ends with an engaging final sentence. This will give readers some idea of what's coming next in their reading experience.

3. Literary Analysis Essay Conclusion

Now that you know how to write a body paragraph, it's time for the conclusion. A good conclusion should end energetically and with an enthusiastic review of all elements discussed in previous paragraphs or sections.

The last paragraph should summarize the main points of your essay. This section needs to use emotional language, make a strong ending argument, and restate the thesis statement.

For your better understanding, we gathered an outline sample that you can use for your help.

SAMPLE LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY OUTLINE

Literary Analysis Essay Outline Examples

One of the best ways to understand anything is by using examples. To give your analysis essay a unique voice and avoid mistakes. You must look at some good examples before starting your writing phase.

Here are some great examples that our professional experts write. Take a look and know how to write a perfect outline of this kind of essay without any difficulty.

HIGH SCHOOL LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY OUTLINE

LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY OUTLINE COLLEGE

Tips for Writing the Literary Analysis Essay

Here are some tips that you should follow when writing a literary analysis essay.

- Follow the proper essay outline format.

- Start a body paragraph with a concise topic sentence.

- Answer the question in the body paragraphs and explain why you chose that particular topic.

- Use poetic language.

- Create an excellent thesis statement.

- Pick a good topic after knowing your audience’s interest.

- Use transition sentences to make a flow between sentences.

- Provide some background information related to the topic in the introduction section.

- Explain the purpose of the essay in-depth.

- Show your understanding of the authors’ methods and goals.

- Gather data from credible sources.

- Write in your own words.

- Support all your main points with quotes and paraphrases.

- Conclude the essay properly by summarizing the main points and restating the thesis statement.

- Avoid writing a simple summary.

- Never forget to proofread your essay before submitting it.

The process of writing a literary analysis outline is not only tricky but also challenging and time-consuming. However, if you want to complete this task well, it needs thorough planning and preparation.

If you're struggling with writing that perfect essay, look no further. Get professional help from the qualified writers of 5StarEssays.com, and we will make sure your order delivers on time.

So, contact us now and get high-quality write my essay services at the best rates.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the 5 components of literary analysis.

The main five components of a literary analysis essay are:

- Point of view

- Figurative language

What is the main purpose of literary analysis?

A literary analysis is used to show that an author has a particular point of view. It is a way to understand the author's purpose, meaning, and message.

Law, Finance Essay

Cordon. is a published author and writing specialist. He has worked in the publishing industry for many years, providing writing services and digital content. His own writing career began with a focus on literature and linguistics, which he continues to pursue. Cordon is an engaging and professional individual, always looking to help others achieve their goals.

Was This Blog Helpful?

Keep reading.

- Literary Analysis Essay - Ultimate Guide By Professionals

- Interesting Literary Analysis Essay Topics for Students

People Also Read

- definition essay topics

- sociology research topics

- informative essay outline

- analytical essay writing

- annotated bibliography example

Burdened With Assignments?

Advertisement

- Homework Services: Essay Topics Generator

© 2024 - All rights reserved

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction

You’ve been assigned a literary analysis paper—what does that even mean? Is it like a book report that you used to write in high school? Well, not really.

A literary analysis essay asks you to make an original argument about a poem, play, or work of fiction and support that argument with research and evidence from your careful reading of the text.

It can take many forms, such as a close reading of a text, critiquing the text through a particular literary theory, comparing one text to another, or criticizing another critic’s interpretation of the text. While there are many ways to structure a literary essay, writing this kind of essay follows generally follows a similar process for everyone

Crafting a good literary analysis essay begins with good close reading of the text, in which you have kept notes and observations as you read. This will help you with the first step, which is selecting a topic to write about—what jumped out as you read, what are you genuinely interested in? The next step is to focus your topic, developing it into an argument—why is this subject or observation important? Why should your reader care about it as much as you do? The third step is to gather evidence to support your argument, for literary analysis, support comes in the form of evidence from the text and from your research on what other literary critics have said about your topic. Only after you have performed these steps, are you ready to begin actually writing your essay.

Writing a Literary Analysis Essay

How to create a topic and conduct research:.

Writing an Analysis of a Poem, Story, or Play

If you are taking a literature course, it is important that you know how to write an analysis—sometimes called an interpretation or a literary analysis or a critical reading or a critical analysis—of a story, a poem, and a play. Your instructor will probably assign such an analysis as part of the course assessment. On your mid-term or final exam, you might have to write an analysis of one or more of the poems and/or stories on your reading list. Or the dreaded “sight poem or story” might appear on an exam, a work that is not on the reading list, that you have not read before, but one your instructor includes on the exam to examine your ability to apply the active reading skills you have learned in class to produce, independently, an effective literary analysis.You might be asked to write instead or, or in addition to an analysis of a literary work, a more sophisticated essay in which you compare and contrast the protagonists of two stories, or the use of form and metaphor in two poems, or the tragic heroes in two plays.

You might learn some literary theory in your course and be asked to apply theory—feminist, Marxist, reader-response, psychoanalytic, new historicist, for example—to one or more of the works on your reading list. But the seminal assignment in a literature course is the analysis of the single poem, story, novel, or play, and, even if you do not have to complete this assignment specifically, it will form the basis of most of the other writing assignments you will be required to undertake in your literature class. There are several ways of structuring a literary analysis, and your instructor might issue specific instructions on how he or she wants this assignment done. The method presented here might not be identical to the one your instructor wants you to follow, but it will be easy enough to modify, if your instructor expects something a bit different, and it is a good default method, if your instructor does not issue more specific guidelines.You want to begin your analysis with a paragraph that provides the context of the work you are analyzing and a brief account of what you believe to be the poem or story or play’s main theme. At a minimum, your account of the work’s context will include the name of the author, the title of the work, its genre, and the date and place of publication. If there is an important biographical or historical context to the work, you should include that, as well.Try to express the work’s theme in one or two sentences. Theme, you will recall, is that insight into human experience the author offers to readers, usually revealed as the content, the drama, the plot of the poem, story, or play unfolds and the characters interact. Assessing theme can be a complex task. Authors usually show the theme; they don’t tell it. They rarely say, at the end of the story, words to this effect: “and the moral of my story is…” They tell their story, develop their characters, provide some kind of conflict—and from all of this theme emerges. Because identifying theme can be challenging and subjective, it is often a good idea to work through the rest of the analysis, then return to the beginning and assess theme in light of your analysis of the work’s other literary elements.Here is a good example of an introductory paragraph from Ben’s analysis of William Butler Yeats’ poem, “Among School Children.”

“Among School Children” was published in Yeats’ 1928 collection of poems The Tower. It was inspired by a visit Yeats made in 1926 to school in Waterford, an official visit in his capacity as a senator of the Irish Free State. In the course of the tour, Yeats reflects upon his own youth and the experiences that shaped the “sixty-year old, smiling public man” (line 8) he has become. Through his reflection, the theme of the poem emerges: a life has meaning when connections among apparently disparate experiences are forged into a unified whole.

In the body of your literature analysis, you want to guide your readers through a tour of the poem, story, or play, pausing along the way to comment on, analyze, interpret, and explain key incidents, descriptions, dialogue, symbols, the writer’s use of figurative language—any of the elements of literature that are relevant to a sound analysis of this particular work. Your main goal is to explain how the elements of literature work to elucidate, augment, and develop the theme. The elements of literature are common across genres: a story, a narrative poem, and a play all have a plot and characters. But certain genres privilege certain literary elements. In a poem, for example, form, imagery and metaphor might be especially important; in a story, setting and point-of-view might be more important than they are in a poem; in a play, dialogue, stage directions, lighting serve functions rarely relevant in the analysis of a story or poem.

The length of the body of an analysis of a literary work will usually depend upon the length of work being analyzed—the longer the work, the longer the analysis—though your instructor will likely establish a word limit for this assignment. Make certain that you do not simply paraphrase the plot of the story or play or the content of the poem. This is a common weakness in student literary analyses, especially when the analysis is of a poem or a play.

Here is a good example of two body paragraphs from Amelia’s analysis of “Araby” by James Joyce.

Within the story’s first few paragraphs occur several religious references which will accumulate as the story progresses. The narrator is a student at the Christian Brothers’ School; the former tenant of his house was a priest; he left behind books called The Abbot and The Devout Communicant. Near the end of the story’s second paragraph the narrator describes a “central apple tree” in the garden, under which is “the late tenant’s rusty bicycle pump.” We may begin to suspect the tree symbolizes the apple tree in the Garden of Eden and the bicycle pump, the snake which corrupted Eve, a stretch, perhaps, until Joyce’s fall-of-innocence theme becomes more apparent.

The narrator must continue to help his aunt with her errands, but, even when he is so occupied, his mind is on Mangan’s sister, as he tries to sort out his feelings for her. Here Joyce provides vivid insight into the mind of an adolescent boy at once elated and bewildered by his first crush. He wants to tell her of his “confused adoration,” but he does not know if he will ever have the chance. Joyce’s description of the pleasant tension consuming the narrator is conveyed in a striking simile, which continues to develop the narrator’s character, while echoing the religious imagery, so important to the story’s theme: “But my body was like a harp, and her words and gestures were like fingers, running along the wires.”

The concluding paragraph of your analysis should realize two goals. First, it should present your own opinion on the quality of the poem or story or play about which you have been writing. And, second, it should comment on the current relevance of the work. You should certainly comment on the enduring social relevance of the work you are explicating. You may comment, though you should never be obliged to do so, on the personal relevance of the work. Here is the concluding paragraph from Dao-Ming’s analysis of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest.

First performed in 1895, The Importance of Being Earnest has been made into a film, as recently as 2002 and is regularly revived by professional and amateur theatre companies. It endures not only because of the comic brilliance of its characters and their dialogue, but also because its satire still resonates with contemporary audiences. I am still amazed that I see in my own Asian mother a shadow of Lady Bracknell, with her obsession with finding for her daughter a husband who will maintain, if not, ideally, increase the family’s social status. We might like to think we are more liberated and socially sophisticated than our Victorian ancestors, but the starlets and eligible bachelors who star in current reality television programs illustrate the extent to which superficial concerns still influence decisions about love and even marriage. Even now, we can turn to Oscar Wilde to help us understand and laugh at those who are earnest in name only.

Dao-Ming’s conclusion is brief, but she does manage to praise the play, reaffirm its main theme, and explain its enduring appeal. And note how her last sentence cleverly establishes that sense of closure that is also a feature of an effective analysis.

You may, of course, modify the template that is presented here. Your instructor might favour a somewhat different approach to literary analysis. Its essence, though, will be your understanding and interpretation of the theme of the poem, story, or play and the skill with which the author shapes the elements of literature—plot, character, form, diction, setting, point of view—to support the theme.

Academic Writing Tips : How to Write a Literary Analysis Paper. Authored by: eHow. Located at: https://youtu.be/8adKfLwIrVk. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

BC Open Textbooks: English Literature Victorians and Moderns: https://opentextbc.ca/englishliterature/back-matter/appendix-5-writing-an-analysis-of-a-poem-story-and-play/

Literary Analysis

The challenges of writing about english literature.

Writing begins with the act of reading . While this statement is true for most college papers, strong English papers tend to be the product of highly attentive reading (and rereading). When your instructors ask you to do a “close reading,” they are asking you to read not only for content, but also for structures and patterns. When you perform a close reading, then, you observe how form and content interact. In some cases, form reinforces content: for example, in John Donne’s Holy Sonnet 14, where the speaker invites God’s “force” “to break, blow, burn and make [him] new.” Here, the stressed monosyllables of the verbs “break,” “blow” and “burn” evoke aurally the force that the speaker invites from God. In other cases, form raises questions about content: for example, a repeated denial of guilt will likely raise questions about the speaker’s professed innocence. When you close read, take an inductive approach. Start by observing particular details in the text, such as a repeated image or word, an unexpected development, or even a contradiction. Often, a detail–such as a repeated image–can help you to identify a question about the text that warrants further examination. So annotate details that strike you as you read. Some of those details will eventually help you to work towards a thesis. And don’t worry if a detail seems trivial. If you can make a case about how an apparently trivial detail reveals something significant about the text, then your paper will have a thought-provoking thesis to argue.

Common Types of English Papers Many assignments will ask you to analyze a single text. Others, however, will ask you to read two or more texts in relation to each other, or to consider a text in light of claims made by other scholars and critics. For most assignments, close reading will be central to your paper. While some assignment guidelines will suggest topics and spell out expectations in detail, others will offer little more than a page limit. Approaching the writing process in the absence of assigned topics can be daunting, but remember that you have resources: in section, you will probably have encountered some examples of close reading; in lecture, you will have encountered some of the course’s central questions and claims. The paper is a chance for you to extend a claim offered in lecture, or to analyze a passage neglected in lecture. In either case, your analysis should do more than recapitulate claims aired in lecture and section. Because different instructors have different goals for an assignment, you should always ask your professor or TF if you have questions. These general guidelines should apply in most cases:

- A close reading of a single text: Depending on the length of the text, you will need to be more or less selective about what you choose to consider. In the case of a sonnet, you will probably have enough room to analyze the text more thoroughly than you would in the case of a novel, for example, though even here you will probably not analyze every single detail. By contrast, in the case of a novel, you might analyze a repeated scene, image, or object (for example, scenes of train travel, images of decay, or objects such as or typewriters). Alternately, you might analyze a perplexing scene (such as a novel’s ending, albeit probably in relation to an earlier moment in the novel). But even when analyzing shorter works, you will need to be selective. Although you might notice numerous interesting details as you read, not all of those details will help you to organize a focused argument about the text. For example, if you are focusing on depictions of sensory experience in Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale,” you probably do not need to analyze the image of a homeless Ruth in stanza 7, unless this image helps you to develop your case about sensory experience in the poem.

- A theoretically-informed close reading. In some courses, you will be asked to analyze a poem, a play, or a novel by using a critical theory (psychoanalytic, postcolonial, gender, etc). For example, you might use Kristeva’s theory of abjection to analyze mother-daughter relations in Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved. Critical theories provide focus for your analysis; if “abjection” is the guiding concept for your paper, you should focus on the scenes in the novel that are most relevant to the concept.

- A historically-informed close reading. In courses with a historicist orientation, you might use less self-consciously literary documents, such as newspapers or devotional manuals, to develop your analysis of a literary work. For example, to analyze how Robinson Crusoe makes sense of his island experiences, you might use Puritan tracts that narrate events in terms of how God organizes them. The tracts could help you to show not only how Robinson Crusoe draws on Puritan narrative conventions, but also—more significantly—how the novel revises those conventions.

- A comparison of two texts When analyzing two texts, you might look for unexpected contrasts between apparently similar texts, or unexpected similarities between apparently dissimilar texts, or for how one text revises or transforms the other. Keep in mind that not all of the similarities, differences, and transformations you identify will be relevant to an argument about the relationship between the two texts. As you work towards a thesis, you will need to decide which of those similarities, differences, or transformations to focus on. Moreover, unless instructed otherwise, you do not need to allot equal space to each text (unless this 50/50 allocation serves your thesis well, of course). Often you will find that one text helps to develop your analysis of another text. For example, you might analyze the transformation of Ariel’s song from The Tempest in T. S. Eliot’s poem, The Waste Land. Insofar as this analysis is interested in the afterlife of Ariel’s song in a later poem, you would likely allot more space to analyzing allusions to Ariel’s song in The Waste Land (after initially establishing the song’s significance in Shakespeare’s play, of course).

- A response paper A response paper is a great opportunity to practice your close reading skills without having to develop an entire argument. In most cases, a solid approach is to select a rich passage that rewards analysis (for example, one that depicts an important scene or a recurring image) and close read it. While response papers are a flexible genre, they are not invitations for impressionistic accounts of whether you liked the work or a particular character. Instead, you might use your close reading to raise a question about the text—to open up further investigation, rather than to supply a solution.

- A research paper. In most cases, you will receive guidance from the professor on the scope of the research paper. It is likely that you will be expected to consult sources other than the assigned readings. Hollis is your best bet for book titles, and the MLA bibliography (available through e-resources) for articles. When reading articles, make sure that they have been peer reviewed; you might also ask your TF to recommend reputable journals in the field.

Harvard College Writing Program: https://writingproject.fas.harvard.edu/files/hwp/files/bg_writing_english.pdf

In the same way that we talk with our friends about the latest episode of Game of Thrones or newest Marvel movie, scholars communicate their ideas and interpretations of literature through written literary analysis essays. Literary analysis essays make us better readers of literature.

Only through careful reading and well-argued analysis can we reach new understandings and interpretations of texts that are sometimes hundreds of years old. Literary analysis brings new meaning and can shed new light on texts. Building from careful reading and selecting a topic that you are genuinely interested in, your argument supports how you read and understand a text. Using examples from the text you are discussing in the form of textual evidence further supports your reading. Well-researched literary analysis also includes information about what other scholars have written about a specific text or topic.

Literary analysis helps us to refine our ideas, question what we think we know, and often generates new knowledge about literature. Literary analysis essays allow you to discuss your own interpretation of a given text through careful examination of the choices the original author made in the text.

ENG134 – Literary Genres Copyright © by The American Women's College and Jessica Egan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Writing A Literary Analysis Essay

- Library Resources

- Books & EBooks

- What is an Literary Analysis?

- Literary Devices & Terms

- Creating a Thesis Statement This link opens in a new window

- Using quotes or evidence in your essay

- APA Format This link opens in a new window

- MLA Format This link opens in a new window

- OER Resources

- Copyright, Plagiarism, and Fair Use

Video Links

Elements of a short story, Part 1

YouTube video

Elements of a short story, Part 2

online tools

Collaborative Mind Mapping – collaborative brainstorming site

Sample Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Paper Format and Structure

Analyzing Literature and writing a Literary Analysis

Literary Analysis are written in the third person point of view in present tense. Do not use the words I or you in the essay. Your instructor may have you choose from a list of literary works read in class or you can choose your own. Follow the required formatting and instructions of your instructor.

Writing & Analyzing process

First step: Choose a literary work or text. Read & Re-Read the text or short story. Determine the key point or purpose of the literature

Step two: Analyze key elements of the literary work. Determine how they fit in with the author's purpose.

Step three: Put all information together. Determine how all elements fit together towards the main theme of the literary work.

Step four: Brainstorm a list of potential topics. Create a thesis statement based on your analysis of the literary work.

Step five: search through the text or short story to find textual evidence to support your thesis. Gather information from different but relevant sources both from the text itself and other secondary sources to help to prove your point. All evidence found will be quoted and analyzed throughout your essay to help explain your argument to the reader.

Step six: Create and outline and begin the rough draft of your essay.

Step seven: revise and proofread. Write the final draft of essay

Step eight: include a reference or works cited page at the end of the essay and include in-text citations.

When analyzing a literary work pay close attention to the following:

Characters: A character is a person, animal, being, creature, or thing in a story.

- Protagonist : The main character of the story

- Antagonist : The villain of the story

- Love interest : the protagonist’s object of desire.

- Confidant : This type of character is the best friend or sidekick of the protagonist

- Foil – A foil is a character that has opposite character traits from another character and are meant to help highlight or bring out another’s positive or negative side.

- Flat – A flat character has one or two main traits, usually only all positive or negative.

- Dynamic character : A dynamic character is one who changes over the course of the story.

- Round character : These characters have many different traits, good and bad, making them more interesting.

- Static character : A static character does not noticeably change over the course of a story.

- Symbolic character : A symbolic character represents a concept or theme larger than themselves.

- Stock character : A stock character is an ordinary character with a fixed set of personality traits.

Setting: The setting is the period of time and geographic location in which a story takes place.

Plot: a literary term used to describe the events that make up a story

Theme: a universal idea, lesson, or message explored throughout a work of literature.

Dialogue: any communication between two characters

Imagery: a literary device that refers to the use of figurative language to evoke a sensory experience or create a picture with words for a reader.

Figures of Speech: A word or phrase that is used in a non-literal way to create an effect.

Tone: A literary device that reflects the writer's attitude toward the subject matter or audience of a literary work.

rhyme or rhythm: Rhyme is a literary device, featured particularly in poetry, in which identical or similar concluding syllables in different words are repeated. Rhythm can be described as the beat and pace of a poem

Point of view: the narrative voice through which a story is told.

- Limited – the narrator sees only what’s in front of him/her, a spectator of events as they unfold and unable to read any other character’s mind.

- Omniscient – narrator sees all. He or she sees what each character is doing and can see into each character’s mind.

- Limited Omniscient – narrator can only see into one character’s mind. He/she might see other events happening, but only knows the reasons of one character’s actions in the story.

- First person: You see events based on the character telling the story

- Second person: The narrator is speaking to you as the audience

Symbolism: a literary device in which a writer uses one thing—usually a physical object or phenomenon—to represent something else.

Irony: a literary device in which contradictory statements or situations reveal a reality that is different from what appears to be true.

Ask some of the following questions when analyzing literary work:

- Which literary devices were used by the author?

- How are the characters developed in the content?

- How does the setting fit in with the mood of the literary work?

- Does a change in the setting affect the mood, characters, or conflict?

- What point of view is the literary work written in and how does it effect the plot, characters, setting, and over all theme of the work?

- What is the over all tone of the literary work? How does the tone impact the author’s message?

- How are figures of speech such as similes, metaphors, and hyperboles used throughout the text?

- When was the text written? how does the text fit in with the time period?

Creating an Outline

A literary analysis essay outline is written in standard format: introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. An outline will provide a definite structure for your essay.

I. Introduction: Title

A. a hook statement or sentence to draw in readers

B. Introduce your topic for the literary analysis.

- Include some background information that is relevant to the piece of literature you are aiming to analyze.

C. Thesis statement: what is your argument or claim for the literary work.

II. Body paragraph

A. first point for your analysis or evidence from thesis

B. textual evidence with explanation of how it proves your point

III. second evidence from thesis

A. textual evidence with explanation of how it proves your point

IV. third evidence from thesis

V. Conclusion

A. wrap up the essay

B. restate the argument and why its important

C. Don't add any new ideas or arguments

VI: Bibliography: Reference or works cited page

End each body paragraph in the essay with a transitional sentence.

Links & Resources

Literary Analysis Guide

Discusses how to analyze a passage of text to strengthen your discussion of the literature.

The Writing Center @ UNC-Chapel Hill

Excellent handouts and videos around key writing concepts. Entire section on Writing for Specific Fields, including Drama, Literature (Fiction), and more. Licensed under CC BY NC ND (Creative Commons - Attribution - NonCommercial - No Derivatives).

Creating Literary Analysis (Cordell and Pennington, 2012) – LibreTexts

Resources for Literary Analysis Writing

Some free resources on this site but some are subscription only

Students Teaching English Paper Strategies

The Internet Public Library: Literary Criticism

- << Previous: Literary Devices & Terms

- Next: Creating a Thesis Statement >>

- Last Updated: Jan 24, 2024 1:22 PM

- URL: https://wiregrass.libguides.com/c.php?g=1191536

- Skip to content

Davidson Writer

Academic Writing Resources for Students

Main navigation

Literary analysis: applying a theoretical lens.

A common technique for analyzing literature (by which we mean poetry, fiction, and essays) is to apply a theory developed by a scholar or other expert to the source text under scrutiny. The theory may or may not have been developed in the service literary scholarship. One may apply, say, a Marxist theory of historical materialism to a novel, or a Freudian theory of personality development to a poem. In the hands of an analyst, another’s theory (in parts or whole) acts as a conceptual lens that when brought to the material brings certain elements into focus. The theory magnifies aspects of the text according to its special interests. The term theory may sound rarified or abstract, but in reality a theory is simply an argument that attempts to explain something. Anytime you go to analyze literature—as you attempt to explain its meanings—you are applying theory, whether you recognize its exact dimensions or not. All analysis proceeds with certain interests, desires, and commitments (and not others) in mind. One way to define the theory—implicit or explicit—that you bring to a text is to ask yourself what assumptions (for instance, about how stories are told, about how language operates aesthetically, or about the quality of characters’ actions) guide your findings. A theory is an argument that attempts to explain something.

Let’s turn again to the insights about using theories to analyze literature provided in Joanna Wolfe’s and Laura Wilder’s Digging into Literature: Strategies for Reading, Analysis, and Writing (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016).

Here’s a brief example of a writer using a theoretical text as a lens for reading the primary text :

In her book, The Second Sex , the feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir describes how many mothers initially feel indifferent toward and estranged from their new infants, asserting that though “the woman would like to feel that the new baby is surely hers as is her own hand,. . . she does not recognize him because. . .she has experienced her pregnancy without him: she has no past in common with this little stranger” (507). Sylvia Plath’s “Morning Song” exemplifies the indifference and estrangement that de Beauvoir describes. However, where de Beauvoir asserts that “a whole complex of economical and sentimental considerations makes the baby seem either a hindrance or a jewel” (510), Plath’s poem illustrates how a child can simultaneously be both hindrance and jewel. Ultimately, “Morning Song” shows us how new mothers can overcome the conflicting emotions de Beauvoir describes.

Daniel DiGiacomo. From Mourning Song to “Morning Song”: The Maturation of a Maternal Bond.

Notice that in this brief passage, the writer fairly represents de Beauvoir’s theory about maternal feelings, then goes on to apply a portion of that theory to Plath’s poem, a focusing move that establishes the writer’s special interest in an aspect of Plath’s text. In this case, the application yields new insight about the non-universality of de Beauvoir’s theory, which Plath’s poem troubles. The theory magnifies a portion of the primary text, and its application puts pressure on the soundness of the theory.

Applying a Theoretical Lens: W.E.B. Du Bois Applied to Langston Hughes

Experienced literary critics are familiar with a wide range of theoretical texts they can use to interpret a primary text. As a less experienced student, your instructors will likely suggest pairings of theoretical and primary texts. We would like you to consider the writerly workings of the theory-primary text application by examining a student’s paper entitled “Double-consciousness in ‘Theme for English B,” an essay which uses W.E.B. Du Bois’s theory (of double-consciousness ) to elucidate and interpret Langston Hughes’s poem (“Theme for English B”). W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963) was an American sociologist, civil rights activist, author, and editor. Langston Hughes (1902-1967) was an American poet, activist, editor, and guiding member of the group of artists now known as the Harlem Renaissance.

But before you can make sense of that student’s essay, we ask that you read both a synopsis of the theoretical text and the primary text .

Primary Text

The instructor said,

Go home and write a page tonight.

And let that page come out of you—

Then, it will be true.

I wonder if it’s that simple?

I am a twenty-two, colored, born in Winston-Salem.

I went to school there, then Durham, then here

to this college on the hill above Harlem,

I am the only colored student in my class.

The steps from the hill lead down into Harlem through a park, then I cross St. Nicholas,

Eighth Avenue, Seventh, and I come to the Y,

the Harlem Branch Y, where I take the elevator

up to my room, site down, and write this page:

It’s not easy to know what is true for you or me

at twenty-two, my age. But I guess I’m what

I feel and see and hear, Harlem, I hear you:

hear you, hear me—we two—you, me, talk on this page.

(I hear New York, too.) Me—who?

Well, I like to eat, sleep, drink, and be in love.

I like to work, read, learn, and understand life.

I like a pipe for a Christmas present,

or records—Bessie, bop, or Bach.

I guess being colored doesn’t make me not like

the same things other folks like who are other races.

So will my page be colored that I write?

Being me, it will not be white.

But it will be a part of you, instructor.

You are white—

yet a part of me, as I am a part of you.

That’s American.

Sometimes perhaps you don’t want to be a part of me.

Nor do I often want to be a part of you.

But we are, that’s true!

As I learn from you,

I guess you learn from me—

although you’re older—and white—

and somewhat more free.

Theoretical Text

W.E.B. Du Bois

Of Our Spiritual Strivings

O water, voice of my heart, crying in the sand,

All night long crying with a mournful cry,

As I lie and listen, and cannot understand

The voice of my heart in my side or the voice of the sea.

O water, crying for rest, is it I, is it I?

All night long the water is crying to me.

Unresting water, there shall never be rest

Till the last moon drop and the last tide fall,

And the fire of the end begin to burn in the west;

And the heart shall be weary and wonder and cry like the sea,

All life long crying without avail

As the water all nigh long is crying to me.

—Arthur Symons

Between me and the other world there is an unasked question: unasked by some through feelings of delicacy; by others through the difficulty of rightly framing it. All, nevertheless, flutter round it. They approach me in a half-hesitant sort of way, eye me curiously or compassionately, and then, instead of saying directly, How does it feel to be a problem? they say, I know an excellent colored man in my town; or I fought at Mechanicsville; or Do not these Southern outrages make your blood boil? At these I smile, or am interested, or reduce the boiling to a simmer, as the occasion may require. To the real question, How does it feel to be a problem? I answer seldom a word.