How To Write An Essay In Afrikaans?

Introduction

Writing an essay in Afrikaans is a great way to communicate your thoughts and ideas. It can also be used to demonstrate your knowledge of the language, as well as to reflect on cultural values and issues that are specific to South Africa. Unfortunately, many students struggle with writing essays in this unique language due to its structure and complexity. Fortunately, there are some tips that you can follow which will help make the process easier.

Tips For Writing An Essay In Afrikaans

Understand the language structure.

The first step in writing an effective essay in Afrikaans is understanding the language structure. Unlike English, Afrikaans has two verb forms – present tense (presente tyd) and past tense (verlede tyd). Both forms must be used correctly when constructing sentences during the writing process for it to flow properly. Additionally, there are three main parts of speech: nouns (naamwoorde), verbs (werkwoorde) and adjectives (bijvoeglike naamwoorde). Understanding how these elements should be combined will also help ensure that your essay reads smoothly throughout.

Research Your Topic

Before starting any kind of paper or assignment it is important to research the topic thoroughly so you have a good foundation on which to build upon when developing arguments or formulating opinions about it. There might already be existing literature around what you’re discussing so use this information wisely by reading up on other people’s ideas or theories related to it before forming your own conclusions or making suggestions regarding potential solutions if relevant.. This way you’ll have more facts at hand which can then be integrated into your essays effectively while avoiding any mistakes caused by incorrect assumptions made beforehand based solely off personal opinion rather than fact-based evidence from reliable sources such as academic journals etc…

Plan Out Your Ideas

Once all necessary research has been done, start planning out what points need addressing within each paragraph of your essay accordingto their relevanceand importancein relationto one another; i ewhich ones should comefirstsecondthirdetc.. This helpsyou stay focusedon topicsat handwhile still beingableto expressyourideas freely without getting sidetrackedonto somethingunrelatedor irrelevanthiswayyoucanbetterdevelopargumentsfor examplebybeingabletoshowhowonepointleadsdirectlyintothenextprovidingthereaderwithanextensiveanalysisoftheissueinyourpaper…

Use Appropriate Vocabulary And Grammar Onceyouhaveplannedoutyour outlineit’stimefocusingonlanguageuseWhenwritinganykindofessaybutespeciallyinaforeignlanguagelikeAfrikaansketyouneedtoconsiderthevocabularyusedAsmentionedbeforetherearetwomainverbformsinAfrikansthatneedbeappliedcorrectlywhenconstructingsentencesbothpresenttenseandpasttenseAdditionallytryincorporatingwordsfromotherSouthAfricanlanguageslikeXhozaZuluetcintoessaysmakeitmoreauthenticToavoidmakingmistakeswithgrammartryreadingwhatyouscribealoudsoyoucanpickupanyerrorsquicklyandfix thembeforesubmittingthefinalcopyofyourwork….

Conclusion WritinganessayinAfrikkansaschallengingbutnotimpossibleWithsomecarefulplanningresearchingappropriatevocabularyusageandanunderstandingofthelanguage’sstructuresuccessfullycompletingacademicpapersinafricanwillbesignificantlyeasierGoodluck!

Possible Related Questions:

Latest Questions Answered

Privacy Policy | Terms & Conditions | Cookie Policy | Sitemap

Copyright © 2024 Askly.co.za, All Rights Reserved

- Announcements

- About AOSIS

Reading & Writing

- Editorial Team

- Submission Procedures

- Submission Guidelines

- Submit and Track Manuscript

- Publication fees

- Make a payment

- Journal Information

- Journal Policies

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Reviewer Guidelines

- Article RSS

- Support Enquiry (Login required)

- Aosis Newsletter

Open Journal Systems

The text is about a topic that is familiar enough: pursuit of a personal ambition, involving obstacles that need to be overcome, resulting in character development. However, the first draft ( Figure 2 ) falls short of the four basic stages of narrative (orientation, complication, evaluation, resolution), and has only some of the structural features specified by the RNCS. At 175 words it is also a little short of the required length of 180–200 words for a Grade 9 narrative essay for FAL. It was not marked or commented on in writing by her teacher.

It is therefore unsurprising that Zenobia’s final draft ( Figure 2 ) differs little from the first. The only changes occur in two places in the second paragraph. In the first instance, ‘…would get me a musical lesson or person who will teach to sing…’ has been improved to ‘…would get me a singing teacher like a person who will teach me singing…’ (s5). The second change involves the elaboration of ‘… I got more better’ to ‘I got courage and I sang very well and he was pleased with me’. ‘As he was teaching me, I got better and better’ (s7–8). The second change provides additional information whilst improving cohesion without, however, adding much by way of ideational content. Taken together the changes do little to lift what is essentially a personal recount to the level of the narrative that was required.

The text lacks several crucial structural elements. Firstly, it is divided into only two paragraphs, of which the first can be said to represent the orientation and the second the complication and resolution, when a minimum of three would have been better. The first paragraph begins with a clear opening statement (‘When I was young singing was the only thing I thought about’ – s1). However, the paragraph contains no reference to the title and no connection between the dream and singing, leaving the reader to infer the link. There is little information about setting (time, place), and no awareness of reader expectations. The characterisation is sparse. We learn about Zenobia’s love of (gospel) singing and the pastor’s encouragement, but only superficially. In the second paragraph Zenobia mentions her parents’ sacrifices, and we find out about her dream of becoming a singer. The complication is hinted at (‘I was struggling at first because it was not easy’ – s7) but not expatiated upon as she does not illustrate what was difficult about the task and what she did to emerge victorious. Because there is no real complication the resolution is similarly unsatisfying (‘but as he was teaching me I got courage and I sang very well’ – s7). Although the sequence of events is logical enough, specificity is lacking and could have been achieved by focusing on a particular incident or event. As a result, the story lacks tension and pace, and the putative climax (leading the worship) is a bit flat – as is the conclusion, in which Zenobia shares her joy at having fulfilled her dream. At best, therefore, the narrative structure is only partly realised ( Table 1 ).

The linguistic features of the composition are partially controlled. A clause analysis reveals that Zenobia uses a fairly high number of subordinate clauses (15/38), resulting in a hypotaxis rate of 39.5%. Of these, the majority (10) are adverb clauses, with 6 temporal clauses (‘as I/he…’, ‘when I…’), 2 causal and 2 conditional subordinates. There are also three noun clauses and two adjective (relative) clauses. Zenobia’s use of subordination suggests that her writing has moved beyond beginner level to an intermediate level of proficiency – what Raison, Dewsbury and Rivalland ( 1997 ), on their writing developmental continuum, would term conventional writing. Yet this impression is offset by the frequent use of ‘speech on paper’ (cf. Hendricks 2008 ), such as in the concatenation of clauses resulting in run-on sentences (cf. repeated conjunctive use of ‘and’), the conversational tone, and the limited vocabulary. The heavy use of temporal adverb clauses and the repeated use of ‘and’ index a linear, chronological rendition that is more characteristic of an (oral) recount than a narrative. In this respect her writing can be described as unsophisticated and basic.

With one exception (‘teached’ for ‘taught’, s7), the use of verb forms is accurate. However, use of tenses is patchy. Although Zenobia largely manages to use the past tense in recounting past events, and the present tense when reflecting on her current feelings (beginning with ‘Now I am a worship leading singer’ – s9), her writing is less secure in other places. Thus in ‘I loved singing so much when I was in church, even if I am sad if I sing everything turns out perfect’ (s2), the use of tense is erratic, shifting from past tense (‘loved’, ‘was’) to conjunctive/present (‘if I am sad’). This is compounded by one of several syntax errors. The paucity of punctuation results in sentences which are confusing, necessitating a rereading (s2, s3); others have several ideas lumped together that should have been subdivided (s4, s5, s7, s10). Two sentences (s3, s9) begin with ‘and’, suggesting unfamiliarity with a conventional prohibition in English composition. The probable influence of the HL (Afrikaans) is suggested at syntactical level ( I stand there in front… s10) as well as at lexical level, in the repetition of better in better and better (s8). Although Zenobia’s vocabulary is no more than adequate, her spelling is generally good: the two spelling errors (‘familliar’, ‘my self’) do not disrupt the flow or impede understanding. Overall, therefore, Zenobia’s essay reveals some promise but also several shortcomings in structure as well as at the level of linguistic features. This raises questions about the type and timing of feedback she received.

The impression of a writer caught between early writing and conventional writing is confirmed by an analysis of mode (realised through the textual metafunction) and tenor (interpersonal metafunction) ( Figure 3 ). A theme-rheme analysis reveals a complete absence of interpersonal themes; that is, it signals the writer’s lack of awareness of the reader’s expectation of emotional engagement in what is after all a highly personal topic. Of the 38 topical themes, by far the largest number (17) consist of the first person ‘I’, highlighting the subjective experience of Zenobia the writer and her personal ‘voice’. And yet the tenor of the text is far from monoglot. A considerable number of topical themes introduce ‘significant others’ in Zenobia’s life: her parents (mentioned four times), her singing teacher (five), her pastor (two) and her church mates (two). A closer look at the distribution of topical themes shows that the teller’s ‘I’ is dominant in the first and last thirds of the story, whereas the voices of these significant others dominate the middle third of the text. Their views emerge in several of the respective rhemes, and are interwoven with Zenobia’s own voice; that is, the text uses a noticeable amount of projection, or reported speech. Given the general lack of sophistication in the writing, this structural arrangement produces an overtly heteroglot text, i.e. one which foregrounds sources of attitude in interlocutors other than the writer.

Thus we read about her pastor’s enjoyment of her singing (clause 9), her parents’ supportiveness of her singing (17–22), her teacher’s pleasure at the improvement in her singing (30), and her fellow churchmates’ appraisal of her singing (36–37). This last instance of heteroglossia is particularly interesting for its use of projection: ‘…and my fellow churchmates tell me that they enjoy my singing’. Here the projecting clause ‘tell me’ introduces the projected (noun) clause ‘that they enjoy my singing’. Such heteroglossia indicates a degree of emotional maturity in Zenobia the person, who is aware of her socially networked existence. Unfortunately, this maturity is not fully realised in her writing – mainly, we would argue, as a result of a lack of feedback.

Assessing Zenobia’s essay

It is worth recalling that the curriculum explicitly links feedback to formative assessment, or ‘assessment for learning’, in which learners are given ‘thought-provoking questions to stimulate learner thinking and discussion’ (DoE n.d. :2). In keeping with this developmental approach to writing, the teacher is to give constructive feedback to enable the learner to grow (DoE 2002 :114). A key assessment standard for writing in the languages learning area (Grades 7–9) is that the learner ‘uses feedback to revise, edit, and rewrite’ (DoE 2002 :105). Accordingly, the characteristics of continuous assessment are ‘appropriate questioning, focusing the teacher’s oral and written comments on what was intended to be achieved by an assessment activity, and encouragement to a learner’ (DoE 2002 :115). The document adds that ‘feedback is more effective when combined with comments. There is more likely to be an improvement in achievement when learners are given written feedback rather than marks only’ (DoE 2002 :118).

In light of the above, what type of feedback did Zenobia receive on her draft, and at what stage did she receive it? The answer, unfortunately, is too little, too late. The only written comments received were on the final draft, and thus had a summative rather than a formative function. In terms of the process approach to writing, the comments and suggestions should have come earlier, at the drafting stage, as there is relatively little formative value in providing comments to the learner after the fact.

An analysis of the teacher’s markings on Zenobia’s final product ( Figure 3 ) reveals the following:

- P (Punctuation): eight instances identified – mostly missing commas and full stops

- Sp (Spelling): three instances, of which one (‘teached’ for ‘taught’) is more a verb form error than a spelling mistake

- G (Grammar): one instance, pointing to an incomplete clause (‘I stand there in front’)

- L: five instances. Presumably a catch-all ‘language’ category that subsumes inappropriate use of vocabulary/word form (‘a singing teacher’), incorrect tense or aspect (‘who will teach me singing’), the wrong register or inappropriate expression (‘they got me one’; ‘I got better and better’), and inappropriate use of a conjunction (‘and’) to start a sentence.

Thus the in-text corrections were largely limited to punctuation and grammar. As such they constitute inadequate feedback with regard to structure, cohesion, and context. In terms of the genre approach (or what the CAPS curriculum refers to as a text-based approach), written comments on the draft should have gone beyond punctuation (syntax) and spelling to include other assessment criteria such as those identified on the departmental assessment rubric that was attached to the learner’s marked final essay. These include register, tone, audience awareness and purpose; originality; paragraphing and development of topic; vocabulary; planning and coherence; editing; and proofreading. Although the teacher has, in our view, given an appropriate mark of 17/30 to Zenobia’s final product, the mark is more a reflection on the process that was (not) followed than on Zenobia’s ability as a writer. Had Zenobia received feedback at the planning (mind map) and drafting stages, it could well have become formative and she would have learnt more about writing narratives. It is troubling as well as ironic that Ms Petersen’s avowed focus on writing as process, observed at the start of the lesson, was not followed through.

It is evident, therefore, that Zenobia was not given enough guidance on how to write a narrative. In particular, she was denied formative comments and suggestions on her mind map and, crucially, on her first draft – something that serves to disadvantage all but the best-performing learners. Several of the limitations of structure and of linguistic feature could otherwise have been overcome. As we have seen, the assessment standards envisage that learners use feedback to revise and rewrite their text for the final draft (Murray 2009 ); in Zenobia’s case this was not adhered to. It is troubling that the restricted nature of the feedback, and the belated stage at which it was provided, combine to limit opportunities for the learner to develop her critical thinking, structure her ideas, and thus improve her writing.

Constraints on feedback

Two main reasons for the lack of feedback when assessing writing suggest themselves. The first has to do with an unwinnable numbers game involving teacher–pupil (learner) ratios in relation to the quantity of assessment tasks. When asked about class size in relation to learner performance, Ms Petersen states matter-of-factly:

‘’Because I have such a lot of learners, I have about 60 in each class, so for me to take in the rough draft and mark it, it is going to be hard for me to mark’.

Ms Petersen’s point is simply that excessively large classes undermine the possibility of providing formative feedback. The absence of essential scaffolding at the drafting stage renders the process approach to writing inoperable. What is implied, rather than stated explicitly is that the number of assessment tasks is unrealistic under conditions of overcrowding 1 . The teacher has to rush through her marking to keep pace with the curriculum demands.

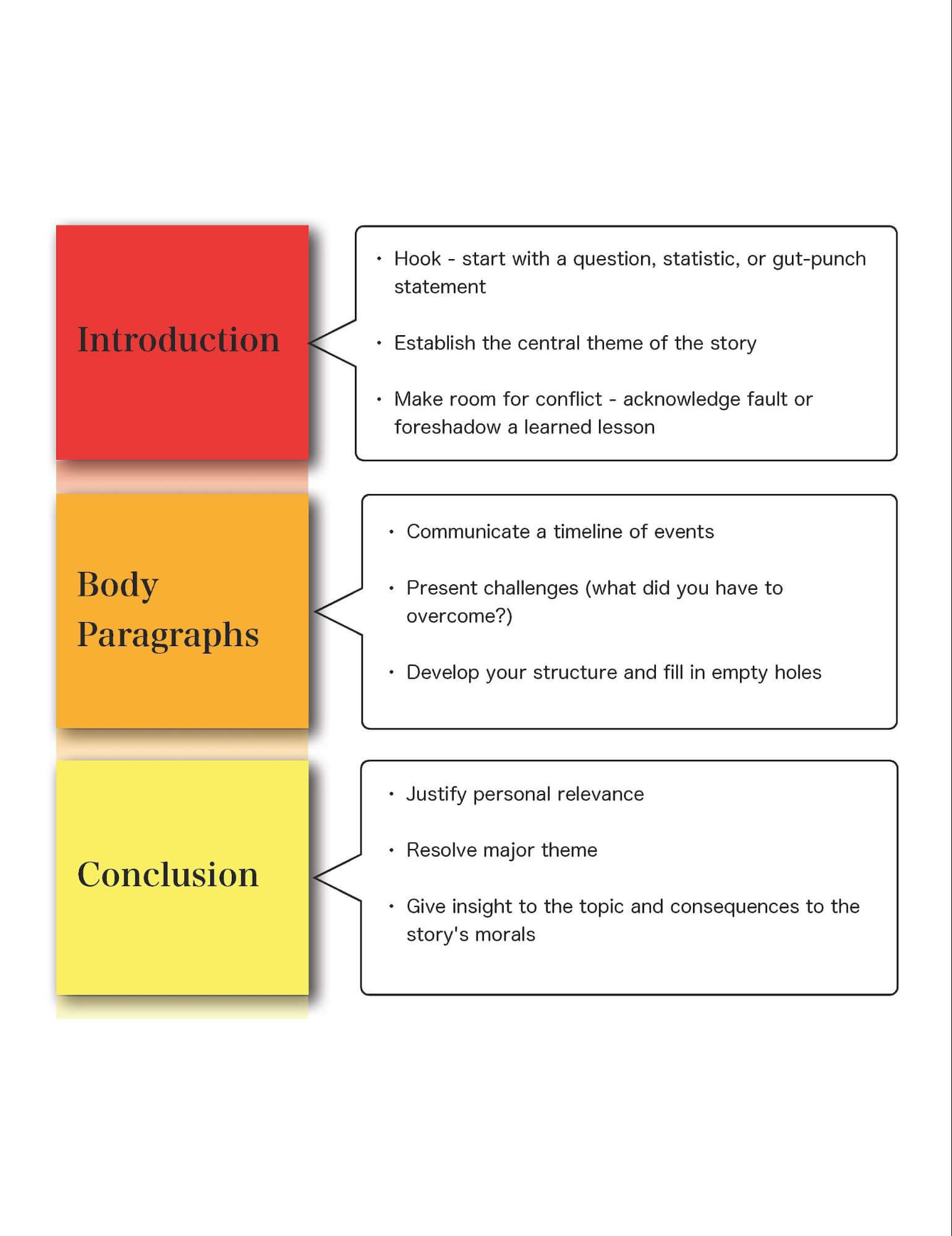

A second constraint, we would argue, is the teacher’s own (partial) understanding of approaches to writing outlined in the curriculum. This is hardly surprising, given that the policy is incomplete, patchy, with insufficient explanation of the social purpose, organisational structure, and linguistic features of the different genres (cf. Hendricks 2008 ). Small wonder, therefore, that Ms Petersen tends to emphasise the time-honoured but limited concepts of introduction, body, and conclusion:

‘okay before you give them a whole lot of writing let them first practice and do introduction and conclusion before they start on the body before they start to do the main part of the essay and obviously then you are done with the text’.

These views suggest that the genre-based approach is unfamiliar. Ms Petersen’s tried-and-tested approach to writing was borne out by lesson observations. At no stage was the schematic structure of narrative explicitly taught, nor was the modelling stage of the curriculum cycle used (cf. Derewianka 1990 ). For example, in her teaching of ‘story’ the terms orientation, complication, evaluation, and resolution were not used, nor was the concept of narrative formally introduced. It is our contention that the overt teaching of the schematic structures of the different genres and their social purpose, through the metalanguage, is a precondition for meaningful writing (see also Kerfoot & Van Heerden 2015 ).

There is thus a glaring disparity between the curriculum requirements with regard to process and genre (or what are termed text-based) approaches to writing, on the one hand, and the teacher’s understanding of these and her classroom practice, on the other. In view of the problems involved in the interpretation and implementation of the curriculum, as outlined above, teachers cannot be held solely responsible for the poor performance of their learners in English additional-language writing.

In this article we have provided evidence of the potential of as well as the constraints on language teaching at a time of curriculum change, with particular reference to the teaching and assessment of narrative writing at Grade 9 level. As Cross, Mungadi and Rouhani ( 2002 ) have pointed out, one of the flaws of the curriculum change in the post-apartheid era was its indifference over the issue of overcrowded learning spaces, which created limited possibilities for learning in the classroom. This failure of educational provision undoubtedly contributes to the mediocrity of learners’ writing. The required pace of curriculum coverage, combined with virtually unmanageable learner–teacher ratios in some schools constrain teachers from giving sufficient individual attention to struggling learners. It is easy to see Ms Petersen’s point that learner performance is negatively affected by the lack of individualised attention the teacher is able to provide during writing lessons. However, a better-trained teacher may well have been able to overcome some of these constraints. It is our contention that as a result of having only a superficial understanding of the theories that underpin the teaching of writing, the teacher in this study is unable to realise the required combination of genre-based and process approaches to writing advocated in the language curriculum. This has self-evident implications for in-service as well as pre-service teacher development, for which government and the universities have respective responsibility.

In this article we have argued that several converging factors are responsible for Zenobia’s under-developed essay. The pivotal ones appear to be a less-than-coherent language curriculum and inadequately trained teachers, exacerbated by unmanageable learner–teacher ratios and the consequent lack of time available for individualised attention during the writing process. Until all three issues are addressed, the undoubted potential of writers such as Zenobia and the generation she represents is unlikely to be realised.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests.

The authors confirm that they have no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors’ contributions

This article is based on the completed M.Ed thesis of C.A. (University of the Western Cape) supervised by P.P. (University of the Western Cape). For this article, additional contextualisation and analysis was provided by P.P., in consultation with C.A.

Akinyeye, C., 2013, ‘Investigating approaches to the teaching of writing in English as a second language in senior phase classrooms in the Western Cape’, MEd dissertation, University of the Western Cape.

City of Cape Town, 2013, City of Cape Town – 2011 Census Suburb Delft , City of Cape Town, viewed n.d., from http://www.capetown.gov.za/en/stats/2011CensusSuburbs/2011_Census_CT_Suburb_Delft_Profile.pdf

Cope, B. & Kalantzis, M., 1993, ‘The power of literacy and the literacy power’, in B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (eds.), The powers of literacy: A genre approach to teaching writing , pp. 63–89, Falmer Press, London.

Cross, M., Mungadi, R. & Rouhani, S., 2002, ‘From policy to practice: Curriculum reform in South African Education’, Comparative Education 38(2), 171–187.

Department of Basic Education (DBE), 2011, Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statements (CAPS) Grades 7–9 English first additional language , DBE, Pretoria.

Department of Basic Education (DBE), 2013, Report on the Annual National Assessment of 2013 , DBE, Pretoria.

Department of Education (DoE), 2002, Revised National Curriculum Statement Grades R-9 (schools) languages English – First additional language , Gazette No.: 23406, Vol 443, May 2002, DoE, Pretoria.

Department of Education (DoE), n.d., National Curriculum Statement assessment guidelines for general education and training (intermediate and senior phases) languages , DoE, Pretoria.

Derewianka, B., 1990, Exploring how texts work , Primary English Teaching Association, Sydney.

Dornbrack, J. & Dixon, K., 2014, ‘Towards a more explicit writing pedagogy: The complexity of teaching argumentative writing’, Reading and Writing 5(1), 1–8.

Eggins, S., 2004, An introduction to systematic functional linguistics , 2nd edn., Continuum, London.

Fleisch, B., 2008, Primary education in crisis: Why South African schoolchildren. Underachieve in reading and mathematics , Juta, Cape Town.

Hendricks, M., 2008, ‘“Capitalising on the dullness of the data”: A linguistic analysis of a Grade 7 learner’s writing’, Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 26(1), 27–42.

Henning, E., van Rensburg, W. & Smit, B., 2004, Finding your way in qualitative research , Van Schaik Publishers, Pretoria.

Heugh, K., 2013, ‘Multilingual education policy in South Africa constrained by theoretical and historical disconnections’, Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 33, 215–237.

Hyland, K., 2007, ‘Genre pedagogy: Language, literacy and L2 writing instruction’, Journal of Second Language Writing 16, 148–164.

Jansen, J.D., 1999, ‘Why outcomes based education will fail: An elaboration’, in J. Jansen & P. Christie (eds.), Changing the curriculum: Studies on outcomes-based education in South Africa , pp. 145–156, Juta, Cape Town.

Kerfoot, C. & Van Heerden, M., 2015, ‘Testing the waters: Exploring the teaching of genres in a Cape Flats Primary School in South Africa’, Language Education 29(3), 235–255.

Macken-Horarik, M., 2002, ‘Something to shoot for: A systemic functional approach to teaching genre in secondary school science’, in A.M. Johns (ed.), Genre in the classroom: Applying theory and research to practice , pp. 17–42, Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah.

Martin, J.R., Christie, F. & Rothery, J., 1987, ‘Social processes in education. A reply to Sawyer Watson (and others)’, in I. Reid (ed.), The place of genre in learning: Current debates , pp. 58–82, Deakin University Press, Geelong, VIC.

Martin, J.R. & White, P.R.R., 2005, The language of evaluation. Appraisal in English , Palgrave MacMillan, Houndmills.

Murray, S., 2009, ‘Making sense of the new curriculum: Understanding how the curriculum works and what it means for language teachers’, in A. Ferreira (ed.), Teaching language , pp. 11–24, Macmillan, South Africa.

Raison, G., Dewsbury, A. & Rivalland, J., 1997, Writing: Developmental continuum , Heinemann, Melbourne.

Suter, W.N., 2012, An introduction to educational research , 2nd edn., Sage, CA.

Vygotsky, L.S., 1978, Mind and society: The development of higher mental processes , Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Wright, L., 2012, ‘Rural teachers, reading, and the social imagination’, in L. Wright (ed.), South Africa’s education crisis. Views from the Eastern Cape , pp. 72–85, NISC, Grahamstown.

1. For the Grade 9 year, the current curriculum for First Additional Language stipulates 10 assessment tasks, 2 tests, a mid-year exam and a final exam.

Crossref Citations

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get specific, domain-collection newsletters detailing the latest CPD courses, scholarly research and call-for-papers in your field.

Reading & Writing   |   ISSN: 2079-8245 (PRINT)   |   ISSN: 2308-1422 (ONLINE)

ISSN: 2308-1422

Services on Demand

Related links, tydskrif vir geesteswetenskappe, on-line version issn 2224-7912 print version issn 0041-4751, tydskr. geesteswet. vol.61 n.3 pretoria sep. 2021, http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2224-7912/2021/v61n3a8 .

NAVORSINGS- EN OORSIGARTIKELS / RESEARCH AND REVIEW ARTICLES (1)

Die waarde van persoonlike vertelling in Afrikaans Huistaal in die Nasionale Kurrikulum en Assesseringsbeleidsverklaring

The value of personal storytelling in Afrikaans Home Language in the National Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement

Corné Van Der Vyver

Fakulteit Opvoedkunde, Skool vir Taalonderwys, Lektor in Afrikaans vir Onderwys, Noordwes-Universiteit, Potchefstroom, Suid-Afrika. E-pos: [email protected]

Storievertelling word wêreldwyd aangewend om individue op 'n informele wyse te onderrig. Persoonlike vertellings of lewensverhale is 'n onderafdeling van storievertelling as groter fenomeen en hierdie persoonlike lewensverhale kan suksesvol as onderrigstrategie ingespan word. In hierdie verband het McAdams (2001:101) bevind dat lewensverhale veral belangrik is as uitdrukking van die individu se identiteit en hom of haar sodoende help om sin te maak van persoonlike ervarings. Storievertelling is dus 'n uitdrukking van identiteit , want om die storie van 'n mens se lewe te vertel, help jou om sin te maak van jou ervarings en kweek 'n gevoel van self, oftewel "wie ek is". Dit is gevolglik baie belangrik dat leerders van 'n vroeë ouderdom af blootgestel word aan en opleiding ontvang in lewensverhaalvertellings. Hierdie blootstelling lei daartoe dat leerders geleidelik daaraan gewoond gemaak word om as 't ware die storie van hul lewe aan ander te vertel. Op hierdie manier verseker blootstelling aan die deel van persoonllike lewensverhale dat individuele leerlinge nie geïntimideer sal voel deur dergelike aktiwiteite wanneer hulle die ouderdom bereik waar die stories van hul persoonlike belewenisse met vertroue vertel kan word nie. Daar is daarom veral gekyk na die Kurrikulum en Assesseringsbeleidsverklaring (KABV) om vas te stel of daar in die KABV voldoende ruimte geskep is om leerders vanaf 'n vroeë ouderdom bloot te stel aan lewensverhale. Daar is ook ondersoek ingestel of hierdie blootstelling en opleiding in die vertel van lewensverhale toeneem totdat leerders in vroeë adolessensie spontaan en met selfvertroue hulle persoonlike stories aan ander kan vertel.

Trefwoorde : Afrikaans Huistaal, dokumentontleding, Kurrikulum en Assesseringsbeleidsverklaring (KABV), lewensverhale, literatuurontleding, McAdams se lewensverhaalteorie, outobiografiese stories, persoonlike vertellings, rol van storievertelling, storievertelling, storievertelvaardighede

Storytelling, in general, is used worldwide as a strategy in informal education. Telling one's personal life story, a subdivision of the encompassing phenomenon, is a valuable educational tool. In this regard storytelling on an individual level possesses important characteristics that can be used to enhance teaching strategies. McAdams (2001:101) found that life stories are especially important in expressing an individual's identity, thereby enabling them to make sense of their experiences. It is therefore very important that learners receive exposure to and training in telling life stories from an early age. This exposure guides learners in gradually becoming familiar with different storytelling activities, thereby enabling them to participate confidently in sharing their life stories upon reaching the age when such activity may be practised successfully. Given the fact that telling life stories is a subdivision of storytelling as a larger global phenomenon, it was important to have a closer look at the functions of storytelling in general. Storytelling as a general educational tool supports the value of learning the art of telling one's life story, especially when considering the influence of storytelling with regard to the neuro-development and associated processes and changes in learners. According to Gazzaniga (2011:75), storytelling reflects a basic ability of the memory to organise, helping a person to present memory thoughts coherently. Particular attention was therefore paid to the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) to determine whether the CAPS underlines Gazzaniga's findings on storytelling and memory functions. It is generally accepted that most people learn best by means of their own meaningful experiences that enable them to connect new knowledge to that which they already believe or understand (Killen 2019:3). The guidelines in the CAPS support the notion that storytelling represents the way in which people use spoken language (discourse) and written language (text) in coherent and meaningful ways (Department of Basic Education 2011:14). It is necessary to determine whether enough time has been allocated in the CAPS to expose learners to storytelling from an early age. Since McAdams found that life stories can only be told successfully in early adolescence, it was necessary to determine whether this exposure to and training in storytelling skills accumulate until learners in early adolescence have reached the point where they are able to participate spontaneously and with confidence in telling their life stories. In this study, the CAPS documents were analysed by means of document analysis to see what kind of storytelling is encouraged, how much time is allocated to storytelling from Grade R to Grade 12 and which skills are acquired, according to the CAPS, for learners to be able to successfully participate in personal storytelling (listening and speaking). Findings in this article show that although learners are exposed to storytelling at a young age, the time allocated in the CAPS for storytelling is not enough to establish a storytelling culture. Also, the time spent on storytelling in class decreases as learners grow older, instead of increases, as would be expected. It is recommended that a partnership be established between the school and the community to address this issue. Teachers do not have enough time in the classroom for personal storytelling to take place, and therefore such a partnership will make a positive contribution in this regard. Moreover, the class situation is not always a safe environment in which to engage in personal storytelling - a problem that can, however, also be addressed by means of a partnership. When storytelling is learnt in the community, it should not be a strange concept for the individual when he or she encounters it in class. In this way, storytelling should facilitate the teacher's task in the classroom. It is important that trustworthiness be established in a partnership in order for it to become the medium through which the participants may safely expose their identity, thereby also assisting others in engaging in a similar activity. In this way such a partnership will be mutually beneficial to all the role players.

Keywords : Afrikaans Home Language, autobiographical stories, Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS), document analysis, life stories, literature analysis, McAdams's life story theory, personal stories, role of storytelling, storytelling, storytelling skills

1. INLEIDING, KONTEKSTUALISERING EN PROBLEEMSTELLING

Wêreldwyd vertel mense van alle kulture en agtergronde stories, want 'n betekenisvolle storie kan potensieel die wêreld ten goede verander. Die meeste van ons word ontroer deur 'n betekenisvolle storie. Vanaf kindsbeen hou mense daarvan om na stories te luister. Storievertelling was nog van altyd af 'n baie belangrike onderrigmedium, want mense verstaan en onthou inligting wat deur middel van stories aan hulle meegedeel word (Gallo 2019:269). Wanneer iemand in 'n soortgelyke situasie beland as waarvan daar in 'n storie vertel is, kan die episode wat die aanhoorder van die storie onthou, daartoe lei dat 'n vergelykbare probleem makliker opgelos word.

Devereaux en Griffin (2013:1) het bevind dat storievertelling 'n relatief groot persentasie van mense se daaglikse aktiwiteite beslaan. Menslike kommunikasie vertoon dikwels dieselfde eienskappe as stories, naamlik doelgerigtheid om gedagtes oor te dra, identifisering en ontwikkeling van 'n storielyn asook die struktuur en doel van 'n tipiese storielyn. 'n Storie vorm 'n eenheid deur die verbinding van 'n samehangende reeks opeenvolgende gebeurtenisse (die dele van die storie word met ander woorde opgeneem in 'n groter geheel). Die afleiding kan daarom gemaak word dat kommunikasie binne 'n spesifieke struktuur 'n manier word waarvolgens gebeure oorgedra kan word. Daarom is dit belangrik dat kinders van kleins af aan die vertel van stories blootgestel word, sodat hulle die kuns kan aanleer om hulle gedagtes op 'n samehangende manier te orden en uit te druk.

Die doel van hierdie artikel is om die belangrikheid van persoonlike storievertelling in die verskillende stadiums van 'n kind se lewe te bespreek, aangesien navorsing daarop dui dat storievertelling baie belangrik is vir kinders se ontwikkeling en opvoeding (Parfitt 2019:7). Kinders wat uit gesinne kom waar daar baie stories vertel word, is geneig om oor beter taal- en interpersoonlike vaardighede te beskik en ook emosioneel sterker te wees (Parfitt 2019:8). Gevolglik moet die belangrikheid van storievertelling, wat stories oor die familie insluit, nie onderskat word in kinderopvoeding binne gesins- of skoolverband nie. McAdams (2001:101) se biografiese lewensverhaalbenadering benadruk hoe individue hul identiteit konstrueer deur die vertel van lewensverhale en daarom is sy biografiese lewensverhaalbenadering gebruik om die fokus van hierdie artikel te verhelder.

Fiese, Hooker, Kotary, Schwagler en Rimmer (1995:764) redeneer dat storievertellingsaktiwiteite iemand se betekenis en identiteit binne die gesinsverband en breër gemeenskap help konstrueer. Storievertelling is gevolglik 'n belangrike strategie om kinders voor te berei vir die lewe. Eerstens, vanuit die perspektief van die verteller, kan stories 'n metode wees om ervarings te integreer in 'n persoonlike identiteit, op 'n soortgelyke manier as 'n outobiografie (Fiese et al. 1995:783). Tweedens help stories om die toehoorders se gevoel van sosiale identiteit te vorm, aangesien hulle deur die gedeelde sin van die geskiedenis hul idees van groeplidmaatskap kan versterk. Siende dat die gemeenskap al hoe meer die plek van die ouers in hul afwesigheid inneem, toon navorsing dat stories kinders help sosialiseer op die gebied van familiewaardes (Fiese et al. 1995:768). Die morele boodskap is 'n belangrike deel van groeperfenis. Stories hou dus belangrike implikasies vir die konstruksie van sosiale identiteit in, aangesien die stories die kind se persepsie van wat "ons" definieer, versterk. Rich (2014:16) toon aan dat stories betekenisvol is ter bevordering van 'n gevoel van groepserfenis en dus 'n rol speel in die vorming van 'n individu se sosiale identiteit. Die feit dat die deelnemers aan storievertelling hul herinneringe dokumenteer, verskaf 'n diskrete korpus geskrewe materiaal wat gebruik kan word as 'n bron van ontleding van die verband tussen lewensverhale en identiteit (Rich 2014:14). Die belangrikheid van lewensverhale word dan ook versterk deur Breen (2015) se bevinding dat diegene wat hul begrip van hulleself kan verander, positiewe veranderings in hul lewens kan bewerkstellig.

Storievertelling is daarom nie net 'n kindertyd-tydverdryf nie; trouens, die belangrikheid van storievertelling tydens volwassenheid word beklemtoon. Storievertelling word beskou as 'n middel om 'n individu te definieer (Breen 2015) en word byvoorbeeld as 'n terapeutiese hulpmiddel in sielkunde aangewend. Identiteit word gebou deur stories, en spesifiek die stories wat 'n persoon van hom- of haarself vertel (McAdams 2001:101). Nuwe ervarings en mense in 'n persoon se lewe verander sy storie of lewensverhaal. Persoonlike stories kommunikeer nie net wie 'n individuele persoon is nie, maar help hom ook om sy eie identiteit beter te begryp. Breen (2015) het ook bevind dat persoonlike storievertelling die storieverteller beïnvloed, veral diegene wat nie geborge en veilig voel nie. Wanneer hulle hul stories met ander deel, laat die aktiwiteit daardie individue voel asof hulle gehoor en erken word. Dit help leerlinge ook om te luister na die stories van hul portuurgroep, sodat hulle kan voel dat hulle êrens behoort en dat hul lewe sin het.

Die deelnemers aan storievertelling is beter voorbereid op gebeure, omdat hulle hierdie gebeure of soortgelyke situasies al in hul verbeelding oordink het. Volgens Van Hulst (2012:312) bestaan enige storie hoofsaaklik uit 'n oorsaak en gevolg - een gebeurtenis lei tot 'n ander. Die mens se brein interpreteer alles en stel "hoekom-vrae" daaroor. So word die storie waarna iemand luister dan geïnterpreteer (Burger 2018:7). Individue verwerk die inligting deur byvoorbeeld self beelde te skep (prentjies te maak) van die gebeure waarvan hulle hoor en denkpatrone in verband daarmee te ontwikkel (Van der Vyver 2018:52).

Zuber-Skerritt (2011:6) beklemtoon dat 'n denkpatroon, 'n gevoel en 'n leefwyse mense se waardes, wêreldbeskouing, leerparadigmas, onderrig en navorsing beïnvloed. Die bepaalde denkwyse wat storievertelling bewerkstellig, beïnvloed dus gedrag, strategieë, metodes en dus kapasiteit ter verbetering van die praktyk in die gemeenskap waar storievertelling beoefen word. Indien storievertelling so beoefen word, dat dit iemand se denkpatroon rig, sal storievertelling 'n rol speel as onderrigstrategie om sodoende die kapasiteit van die storievertelpraktyk in die gemeenskap te vergroot. Gevolglik is dit belangrik dat mense die vaardighede aanleer om hul eie lewensverhale te konstrueer, maar dit is eweneens belangrik dat hulle oor die kennis beskik oor waar en wanneer dit gepas is om hul lewensverhale te vertel.

Teen hierdie agtergrond is dit belangrik om ondersoek in te stel na wat die waarde van lewensverhale (persoonlike vertellings) in Afrikaans Huistaal in die Nasionale Kurrikulum en Assesseringsbeleidsverklaring (KABV) is.

Die antwoord op hierdie vraag word gerig deur die volgende sub-navorsingsvrae:

• Watter rol speel persoonlike storievertelling volgens McAdams se teorie in kinders se ontwikkeling en opvoeding?

• Watter soort storievertelling word in die KABV aangemoedig?

• Hoeveel tyd word in die KABV vir graad R tot graad 12 aan persoonlike storievertelling toegedeel?

• Watter vaardighede word volgens die KABV aangeleer om suksesvol aan persoonlike storievertelling te kan deelneem (luister en praat)?

2. NAVORSINGSMETODOLOGIE

In hierdie studie is dokumentontleding sowel as literatuurontleding gebruik om die waarde wat in die KABV aan persoonlike storievertelling in Afrikaans Huistaal geheg word, vas te stel. Dokumentontleding is 'n sistematiese prosedure vir die hersiening of evaluering van dokumente - sowel gedrukte as elektroniese materiaal. Soos ander ontledingsmetodes in kwalitatiewe navorsing, vereis dokumentontleding dat data ondersoek en geïnterpreteer word om betekenis voort te bring, begrip te verkry en empiriese kennis te ontwikkel (Corbin & Strauss 2008; Rapley 2007). Die analitiese prosedure behels die vind, seleksie, evaluering, ontleding en sintese van data wat in dokumente bestaan. Dokumentontleding lewer data op uit uittreksels, aanhalings of volledige gedeeltes van bronne. Hierdie data word dan verdeel in kategorieë en voorbeelde deur middel van inhoudsontleding (Labuschagne 2003:30).

Die dokumente wat in hierdie studie gebruik is, is al die amptelike KABV-dokumente vir Afrikaans Huistaal, graad R tot 12 (Departement van Basiese Onderwys 2011, hierna na verwys as KABV 2011a-d). Hierdie dokumente is ondersoek om 'n duidelike beeld van persoonlike storievertelling in die Afrikaans Huistaal-kurrikulum, soos voorgeskryf deur die Departement van Onderwys, te verkry. Sodoende is dokumentanalise gebruik om die waarde van persoonlike storievertelling in die KABV ten opsigte van agtergrond en konteks vas te stel (vgl. Bowen 2009:30).

Die volgende stappe is gevolg in die dokumentontleding (Labuschagne 2003:32): vluglees (oppervlakkige ondersoek), lees (deeglike ondersoek) en interpretasie. Hierdie iteratiewe proses kombineer elemente van inhoudsontleding en literatuurontleding. Inhoudsontleding is die proses om inligting in kategorieë wat met die sentrale vrae van die navorsing verband hou, te organiseer (Labuschagne 2003:32). Dit is verder noodsaaklik om toepaslike inligting te identifiseer en te skei van inligting wat nie relevant is nie (Corbin & Strauss 2008).

Gevolglik is besluit om die literatuur te ontleed met die doel om die hoofonderwerpe wat storievertelling behels, te identifiseer (vgl. Gonzales, Gasco & Llopis 2006:821). Bevindings uit die literatuuroorsig is eers saamgevat, wat 'n basiese uiteensetting bied van die wyse waarop Suid-Afrikaanse skole storievertelling volgens die KABV verstaan en beoefen. Soortgelyk aan die oorsig van York-Barr en Duke (2004) wat sleutelterme gebruik wat na die onderwerp verwys wat ondersoek word, is die KABV-dokumente ontleed deur gebruik te maak van sleutelterme wat na storievertelling verwys. Die sleutelterme "gesproke taal", "luister- en praatstrategieë", "praatvaardighede" en "mondelinge kommunikasie" is gebruik om die nodige voorskrifte ten opsigte van storievertelling op te spoor. Die resultate van hierdie ontleding is onder die volgende temas gekategoriseer: die oorsig van taalvaardighede vir die onderrig in Huistaal; inhoud, vaardighede, strategieë en verspreiding van tekste; voorgestelde duur van tekste wat vir mondelinge kommunikasie toegestaan moet word; voorgestelde lengte van mondelinge kommunikasie; en die onderrigplanne van veral graad 10 tot 12.

3. TEORETIESE EN KONSEPTUELE RAAMWERK

Soos reeds gestel, is storievertelling 'n belangrike strategie om individuele persone voor te berei op die lewe. Enigiemand is dan beter voorbereid, omdat hulle die gebeure of situasie al oordink het in hul fiktiewe lewe (verbeelding). Die stories wat mense vertel, bied insig in die wyse waarop die vertellers sin maak van hulleself en hul sosiale wêreld. Vanuit hierdie standpunt kan stories beskou word as nie alleen die gebeure waarvan mense vertel nie, maar ook wat mense beleef (Polletta, Chen, Gardner & Motes 2011:113). In hierdie studie is veral die onderafdeling van storievertelling, naamlik die lewensverhaal (ook genoem "persoonlike vertelling" of "outobiografiese storie") bestudeer as 'n uitdrukking van identiteit, want om die storie van 'n mens se lewe te vertel, help 'n individuele persoon om sin te maak van sy of haar ervarings en bewerkstellig 'n gevoel van self (wie is ek) (McAdams 2001:100; Pollinghorne 1988:258). McAdams (2001:101) se biografiese lewensverhaalbenadering fokus op hoe individue hul identiteit konstrueer deur die proses van vertelling van hul lewensverhale en is gevolglik juis om hierdie rede as teoretiese raamwerk vir die studie gekies. Deurleefde ervarings, 1 wat bestaan uit episodiese oomblikke uit die verlede, kan as die boublokke vir hierdie lewenstories dien. Stories kan 'n beduidende en blywende invloed op 'n persoon hê, omdat stories as boustene van identiteit dien (Ghaempanah & Khapova 2020: 686). Stories is die individu se manier om te verstaan wie hy of sy is en ook wat hy of sy is vergeleke binne 'n groter bestaan. Die verband tussen stories en identiteit is daarom 'n belangrike fokus van die lewensverhaal of persoonlike vertelling.

3.1 McAdams se teorie

Volgens McAdams (2006a:26) se lewensverhaalbenadering begin mense wat in moderne samelewings woon hul lewens organiseer volgens hul persoonlike verhale tydens jong volwassenheid. Met ander woorde, mense herskep hul verlede en antisipeer hul toekoms ooreenkomstig geïnternaliseerde lewensverhale wat oor tyd heen ontwikkel. In hierdie lewensverhaal leer die individu uit 'n storie van sy of haar eie milieu, tonele, karakter, plot en tema. Die lewensverhaal dek nie elke besonderheid van 'n persoon se lewe nie, maar bevat belangrike en prominente tonele daarvan. Die betekenis en waardes toegeskryf aan die tonele in die lewensverhaal is grootliks afhanklik van die individu self en die kultuur waarin hy of sy woon. Wat elke individu se interpretasie van die tonele uit sy/haar lewensverhaal anders maak, is subjektiewe interpretasie van vorige ervarings en selektiewe integrasie daarvan met die spesifieke kultuur waarbinne die persoon woon (McAdams 2006a:76). Daarom sal geen twee lewensverhale presies dieselfde wees nie, alhoewel dit mag wees dat die stories dieselfde gebeure insluit wat op dieselfde tydstip plaasgevind het. Wat elke individu gelykstel aan 'n ander, dit wil sê die wyse waarop gemeenskaplikheid tussen mense verklaar word, lê in die ooreenstemmende temas wat in hulle lewensverhale voorkom. McAdams (2006a:76) wys daarop dat ten spyte van die uniekheid van individuele lewensverhale, daar algemene temas waarneembaar is in die stories wat grootliks deur 'n betrokke persoon se kultuur beïnvloed word. Hy tref onderskeid tussen twee tipes temas in mense se lewensverhale:

• Agentskap teenoor gemeenskap

Mense wat uit kulture, soos byvoorbeeld China en Japan, kom wat voorstanders is van kollektivisme, is geneig om hul stories te ontwikkel rondom 'n gemeenskapstema waarin hulle meer fokus op die ooreenkomste van sosiale norme en groepwerk in hul lewensverhale. Aan die ander kant is mense uit individualistiese kulture, soos byvoorbeeld Europa en Noord-Amerika, meer geneig om hul stories rondom die tema van agentskap te ontwikkel, waarin hulle hul individuele doelwitte en prestasies beklemtoon (McAdams 2006a:277-278).

• Verlossing teenoor kontaminasie

Die kontaminasie-tema manifesteer wanneer 'n baie goeie of affektief positiewe lewensverhaaltoneel gevolg word deur 'n baie slegte, affektief negatiewe uitkoms. In teenstelling met kontaminasie word die verlossingstema waargeneem wanneer 'n slegte, affektief negatiewe lewensverhaaltoneel gevolg word deur 'n baie goeie, affektief positiewe lewensverhaaltoneel. Oorwinning staan sentraal in hierdie tema. McAdams (2006a:278-279) dui aan dat dit die tipe tema is wat meestal verband hou met 'n kultuur waarin die idee beklemtoon word dat daar altyd 'n kans is dat sekere gebeure, gewaarwordinge en denke meewerk om die persoon te bevry uit sy problematiese omstandighede. Sodoende kry 'n persoon die geleentheid om probleme te oorkom.

Die basiese uitgangspunt van McAdams se lewensverhaalmodel is dat die lewensverhaal altyd besig is om te ontwikkel. Die rede vir die bou van 'n lewensverhaal is om 'n psigososiale eenheid en 'n doel binne die hedendaagse wêreld te hê. Individue se lewensverhale vertel daarom nie net hoe hulle hul vorige ervarings interpreteer nie, maar ook hoe hulle verwag hul toekomstige lewens sal wees (McAdams 2013:425).

Lewensverhale is vol gebeure wat die self en ander se konseptuele perspektiewe kan beïnvloed. Die storieverteller vertel van gebeure wat die toehoorder dalk ook beleef het en daag die toehoorder se konsep of teorie oor die saak uit. Indien die toehoorder hierdie storie herhaaldelik hoor, word hy of sy herhaaldelik gekonfronteer met sy of haar eie konseptuele perspektiewe en kan die storievertelling veroorsaak dat die toehoorder die gebeure anders sien en sy of haar ervaring verhelder, wat dan tot 'n veranderde perspektief kan lei. Hierdie nuwe perspektief op die gebeure kan ook die toehoorder se konsep of teorie oor die gebeure beïnvloed, sodat die toehoorder hierdie gebeure in 'n nuwe lig sien; sodoende beïnvloed storievertelling ook die toehoorder se identiteit. Storievertelling skep dus ruimte vir 'n verskeidenheid akteurs (McAdams 1997:64), almal met hul eie ondervinding en ervaring en hul eie gevoelswêrelde. Hierdie aktiwiteit stel akteurs in staat om saam te bou aan gedeelde begrip van hul situasie en wat daaraan gedoen kan word. Storievertelling is gevolglik 'n bruikbare onderrigstrategie, want daarmee kan die verteller aan die toehoorders oordra wat hy of sy uit eie ervarings geleer het. Storievertelling kan daarom beskou word as 'n aktiwiteit wat "Situasie A + Situasie B = Situasie C" dikwels uitvoer in woorde en beelde, improvisasie of simbole. Storievertelling akkommodeer op hierdie manier 'n verskeidenheid akteurs wat hul eie ervarings en emosies deel in die storielyn, sodat gedeelde begrip en oplossings met betrekking tot die aktiwiteit verleen kan word. Op hierdie manier word kennis en identiteit in 'n sosiale konteks geskep en onderhandel (Van der Vyver 2018: 53).

Deur na ander se stories te luister, word die toehoorder in staat gestel om die blik na binne te draai en stories te "besit" in ander stemme as slegs teoretiese taal (Aveling 2001:43). So bied die storieverteller nie slegs stories aan vanuit die oogpunt van 'n opvoeder nie, maar ook die konstruksie van die eie self word ter insae ingespan (Anderson 1995:35). Byvoorbeeld: Hoe het 'n persoon geword wat die wêreld hom of haar gemaak het? Die storieverteller wil die gehoor uitdaag om wesenlike aannames oor kultuur en identiteit te bevraagteken, aangesien opvoeders, volgens Giroux en Mclaren (1994:32), op alle vlakke die idee van kultuur as 'n belangrike bron moet opneem vir die ontwikkeling van identiteit, gemeenskap en pedagogie. Kritiese storievertelling begin dus deur identiteit te dekonstrueer, verbindings met die gemeenskap te maak en uiteindelik pedagogiese moontlikhede te bied (Aveling 2001:46).

Persoonlike vertellings of lewensverhale het met ander woorde groot waarde in die vorming van die individu se identiteit, asook in die toerusting en onderrig van die individu as iemand wat sy of haar plek in die gemeenskap kan volstaan. Persoonlike vertellings of lewensverhale is 'n onderafdeling van storievertelling as groter fenomeen, en storievertelling beskik oor waardevolle funksies. Dit het derhalwe belangrik geword om te kyk oor watter funksies storievertelling beskik en waarom dit so belangrik is dat individue opgelei word om aan persoonlike vertellings of lewensverhale deel te neem (Merril, Booker & Fivush 2018:752).

3.2 Funksies van storievertelling

Linabary et al. (2017:435) wys daarop dat storievertelling drie primêre funksies het, naamlik epistemologies, transformatief en metodologies. Volgens die epistemologiese funksie is storievertelling 'n manier om kennis te skep en te deel, identiteit te vorm en sosialisering te bewerkstellig. Betekenis word geskep in die storievertelproses, óf deur toehoorders se eie interpretasies óf deur deelname aan die storievertelproses. As 'n gedeelde proses kan storievertelling wedersydse erkenning en die vorming van gedeelde identiteit fasiliteer. Stories kan gebruik word om sin te maak van komplekse kwessies deur hierdie kwessies te verduidelik. Storievertelling kan begrip vir konflik bevorder deur die oorsprong van die konflik te verduidelik, 'n stem en empatie aan 'n sekere standpunt te gee en sodoende versoening te bewerkstellig.

Storievertelling beskik ook oor die potensiaal om die deelnemers aan die aktiwiteit te verander of te vernuwe. Deur storievertelling deel die verteller sy of haar eie ervaring en maak die gehoor betrokke by die storie deur die bemagtiging van 'n individu - die aanhoorder leer uit die verteller se ervaring. Kirkwood (soos aangehaal deur Linabary et al . 2017:435) beweer dat storievertelling 'n manier is van selfkonfrontasie, waar individuele persone gevra word om hul eie oortuigings en ingesteldhede of houdings krities te oorweeg. As gevolg daarvan veroorsaak die betrokkenheid by storievertelling ook in sommige gevalle weerstand- en paradigmaverskuiwings. Persoonlike en biografiese storievertelling, in die besonder, word gebruik as deel van vredespogings, postkonflikversoening en genesingspogings (Jayakumar 2015). Stories kan ingespan word om kreatiewe moontlikhede te skep wanneer die stories mense se waardes en oortuigings oordra. Volgens Linabary et al . (2017:441) skep storievertelling ook ruimte vir dialoog, waar deelnemers die konflik in hul gemeenskappe kan bespreek. Voorts sien Linabary et al . (2017:443) storievertelling as 'n impuls vir kritiese nadenke, wanneer dit deur deelnemers gebruik word om hul eie rol in die gemeenskap te bedink. Wanneer toehoorders na 'n storie luister waarmee hulle kan identifiseer of waarmee hulle hul kan vereenselwig, selfs wanneer die storieverteller na sy of haar eie storie luister of kritiese vrae moet bedink om sy of haar eie storie te konstrueer, veroorsaak hierdie aktiwiteit dat die deelnemers hul eie interpretasies van die storie moet bedink en krities moet nadink oor hoe dit verband hou met hul spesifieke situasie. Volgens Linabary et al . (2017:444) is dit die moment wanneer deelnemers bewus word van wat hul eie rol in die samelewing is. Deelnemers identifiseer met 'n storie en kan sodoende aansluiting vind by die storie en hulleself in verhouding tot ander sien. Sodoende maak die storie 'n dialoog oop vir die deelnemers en 'n verdere konstruktiewe gesprek oor hul eie probleme word gevolglik moontlik gemaak (Çetin 2020:2). Hierdie eienskap van storievertelling bevorder ook die gevoel van gemeensaamheid onder deelnemers, asook die gevoel dat hulle êrens behoort (identiteit) (Putman & Kolb 2000:76-104).

Storievertelling beskik ook oor metodologiese nut. Storievertelling as metode vereis geen spesifieke opleiding of toerusting nie (Senehi 2002:43, 2009:201) en is buigsaam en toeganklik. Storievertelling kan verskeie vorme aanneem wat gebaseer is op die situasie. Voorts is geletterdheid ook nie 'n vereiste om stories te kan vertel nie (Senehi 2009:44). Soos reeds opgemerk, is storievertelling 'n draer van kulturele relevansie. In sekere kontekste kan spesifieke vorme van storievertelling (bv. gelykenisse, spreekwoorde en metafore) algemeen voorkom in die alledaagse gesprek of binne bepaalde instellings as 'n middel om inligting oor te dra, te sosialiseer of selfs konflik op te los.

Volgens Senehi (2010:112) word die storieverteller vermenslik wanneer daar na sy of haar storie geluister word en word verhoudings sodoende in 'n gemeenskap opgebou wat as basis vir vrede kan dien. Stories ontwapen dikwels dié wat daarna luister en kan 'n paradigmaskuif by die luisteraar ontlok. Stories kan mense egter ook bemagtig omdat enigiemand 'n storie kan vertel; daarom het stories 'n invloed op die sosiale konstruksie en betekenis van 'n persoon se leefwêreld (Dolan 2021). Storievertelling is een van die uitgebreidste maniere met behulp waarvan 'n mens kan skep of herskep en kultuur kan oordra (Zwack et al . 2016:595). Storievertelling is 'n magtige medium waardeur kruiskulturele ontmoetings kan plaasvind. Wanneer toehoorders fokus op die persoon wat van sy of haar ervarings vertel, eerder as op die interpretasie bemagtig dit hulle om die legitimiteit van die spreker se ervarings te aanvaar en kan hulle gevolglik empatie met die persoon toon (Senehi 2010:112; Linabary, Krishna & Connaughton 2017:436).

Stories betrek gelyktydig die gedagtes en emosies van 'n persoon, wat albei elemente is wat noodsaaklik is om ander te motiveer (Gowln 2011). Die proses waar luister en praat afgewissel word tydens storievertelling, kan geniet word en skep sodoende 'n positiewe hulpbron vir emosies in situasies van konflik en geweld. Storievertelling bevorder verder sosiale insluiting, omdat dit min of geen tegnologiese toerusting, geld of hulp vereis nie. Mense kan aan hierdie kulturele storievertelproduksie deelneem ongeag hul finansiële of ander omstandighede (Senehi 2010:113).

Stories is intellektueel toeganklik vir almal, want almal verstaan stories en kan aan storiegebaseerde ingryping deelneem ongeag hul ouderdom, kulturele agtergrond of behoeftes (Senehi 2010:113). Wanneer jongmense aan die kuns van storievertelling blootgestel word, sal hulle die maniere waarop stories gekonstrueer word, beter herken, met die gevolg dat hulle minder kwesbaar sal wees vir misleidende of manipulerende temas en kulturele stereotipes makliker sal kan weerstaan. Mense se selfbeeld word bevorder wanneer hulle stories van hul eie kultuur hoor en die verband daarmee met ander kulture kan herken (Van der Vyver et al . 2019:245).

Die ontwikkeling van 'n storieverteltegniek is 'n effektiewe manier om openbare redevoering te bevorder, wat weer noodsaaklik is vir demokrasie. Storievertelling mag 'n persoon in staat stel om voorsiening te maak vir die artikulasie van 'n gesamentlike geskiedenis, wat 'n gevoel van herstellende geregtigheid sowel as hernuwing voorsien wanneer diverse kulturele verhale nie meer die hele groep uitsluit of verdraai nie, maar eerder die verlede in die kollektiewe geheue eer deur middel van die geskrewe rekord, kulturele produksie, rituele en interpretatiewe gebiede (Senehi 2010:113).

3.3 Storievertelling en die brein

Garland (2016) het bevind dat storievertelling die brein op verskillende wyses beïnvloed. (1) Tydens storievertelling word dele van die brein geaktiveer deur neurale koppeling en die toehoorder word daardeur in staat gestel om die storie in sy of haar eie idees en ervarings te verander. (2) Verder veroorsaak storievertelling dat die brein spieëlbeelde maak; dit is makliker vir die individu om aansluiting te vind by 'n storie wanneer hy hom kan vereenselwig met die ervarings, wat bekendstaan as spieëlbeeld. (3) Die brein stel dopamien vry wanneer 'n emosioneel gelaaide gebeurtenis ervaar word, wat dit makliker maak om die gebeure te onthou en ook met groter akkuraatheid te berg. Die toehoorder sal daarom onthou dat die gebeure wat hy of sy ervaar, by iemand anders gehoor is en dat die storieverteller sekere uitkomste of oplossings aanbeveel het. (4) Wanneer die feite van die storie wat aangehoor word deur die toehoorder verwerk word, word twee areas van die brein geaktiveer (Broca en Wernicke se areas). Hierdie areas word vereenselwig met die verwerking van taal (vergelyk Figuur 1 ). Enige storie (bv. Gouelokkies en die drie bere) wat goed vertel word, kan baie ander bykomende areas betrek, waaronder die volgende: (1) die motoriese korteks: wanneer die toehoorder byvoorbeeld skrik vir iets wat in die storie gebeur; (2) die sensoriese korteks: die toehoorder voel byvoorbeeld dat die pap warm is of ruik dit brand of sien die papbakkie is leeg (die toehoorder kan hom of haar met ander woorde in die skoene van die karakter plaas deur gebruik te maak van die ervarings wat die toehoorder en die storieverteller deel); en (3) die frontale korteks: die toehoorder voel byvoorbeeld die vrees vir die bere wat teruggekom het en rekenskap eis van alles wat in hul huisie verkeerd geloop het. Stories kan aan die einde daarvan vir die individu gerusstelling gee. So onbenullig as wat dit mag lyk, is daardie gevoel van sekuriteit noodsaaklik vir 'n persoon se oorlewing (Garland 2016).

Gazzaniga (2011:75) het bevind dat die linkerhemisfeer 'n funksie het wat die "interpreteerder" genoem kan word. Hierdie funksie stel die individu in staat om die gapings van die geheue in te vul met aanneemlike dele sodat die vertelling kontinuïteit behou. Om 'n storie te kan vertel, is dus 'n basiese vermoë van die geheue om te kan organiseer. Vanaf die individu se vroeë kinderjare vertel hy of sy stories oor aksies en ervarings. Akkuraatheid is nie die hoofdoelwit nie; samehang is. As dit nodig is, sal die verteller gedagtes van gebeure uitdink wat nog nooit gebeur het nie of mense wat nie bestaan nie, net om die samehang van die narratief te behou (McAdams 2019:2).

Aveling (2001:40) is van mening dat inligting wat deur middel van storievertelling verkry word, beter onthou word as deur 'n formele voorstelling, want storievertelling illustreer grafies hoe eienskappe soos kultuur, geslag, sosiale klas en armoede die lewens van werklike mense beïnvloed. Dit is derhalwe duidelik dat 'n individuele persoon grootliks baat by die beoefening van persoonlike vertellings of die vertel van sy of haar lewensverhaal.

Vervolgens word daar gekyk of daar genoeg waarde geheg word in die KABV aan persoonlike vertellings of die vertel van 'n lewensverhaal, sodat Afrikaanssprekende skoolgaande kinders genoegsaam opgelei kan word in hierdie belangrike kuns van storievertelling.

4. BEVINDINGS EN BESPREKING

Samevattend is uit die ontleding van relevante literatuur bevind dat die manier waarop kinders hulleself verstaan en hoe hulle van hulself en hul lewens vertel, 'n belangrike rol speel in hoe hulle die wêreld waarin hulle grootword, verstaan. Elke kind se storiestem word gevorm en verander deur die mense rondom hulle (Anon 2015). Almal is inherent storievertellers en raak maklik betrokke by storievertelling wanneer dit in 'n geborge en veilige omgewing 2 geskied. Wanneer storievertellers toegelaat word om hul liefde vir stories uit te leef en betrokke te raak by storievertelpraktyke, in en buite die klaskamer, verstaan hulle dat leer in baie vorme kan plaasvind. Hulle ervaar ook deur stories dat onderrig pret kan wees en daarom as 'n positiewe aktiwiteit ervaar kan word en nie altyd die aktiwiteit is wat dikwels met formele onderrig vereenselwig word nie. Daarbenewens staan die genot van stories daarvoor bekend dat dit stres verminder en dat dit 'n mens meer ontvanklik en empaties maak (Kucirkova 2019).

Die KABV (2011c:11) dui aan dat storievertelling as strategie oorkoepelend voorgeskryf word in die KABV veral ten opsigte van die onderrig van taal, asook die vaardigheid van lees en luister -

Fokus op betekenisvolle aktiwiteite. Verwerwing van die grammatikale reëls van die taal stel nie noodwendig die leerder in staat om die taal op 'n samehangende en betekenisvolle wyse te gebruik nie. Die gebruik van taal gaan oor meer as die gebruik van struktuur en funksie van die betrokke sin, byvoorbeeld die wyse waarop mense óf gesproke taal (diskoers) óf geskrewe taal (teks) op samehangende en betekenisvolle wyses gebruik.

Storievertelling is niks anders as die wyse waarop mense gesproke taal (diskoers) en geskrewe taal (teks) in samehangende en betekenisvolle wyses gebruik nie.

Luister en praat is die middelpunt van leer in alle vakke. Deur effektiewe luister- en praatstrategieë kan leerders inligting insamel en sintetiseer, kennis opbou, probleme oplos, idees uitdruk en menings uitspreek. Kritiese luistervaardighede stel leerders in staat om waardes en houdings in tekste te herken, en manipulerende taal waar te neem en aan te spreek. (KABV 2011c:14)

Luister- en praatstrategieë staan sentraal in storievertelling.

Die KABV (2011c:14) is ook voorskriftelik ten opsigte van praatvaardigheid: Leerders moet in staat wees om die vaardighede van beplanning, navorsing en organisering vir mondelinge aanbiedings te demonstreer deur die volgende: • gebruik gepaste register, styl en toon volgens die gehoor, doel, konteks en tema; • gebruik toepaslike taal (keuse van woorde).

Hierdie vaardighede word aangeleer wanneer leerders aan storievertelling blootgestel word sonder dat hulle voel dat hulle formeel onderrig word, veral as daar 'n kultuur van storievertelling in die gemeenskap geskep is.

Die voorgestelde duur van tekste wat vir mondelinge kommunikasie gelewer moet word, word soos volg in die KABV aangedui vir onder andere graad 7 tot 9:

Gesprekke, debatte, forum-/groep-/paneelbesprekings 15 - 20 minute; dialoë 4 - 6 minute; aanwysings en instruksies 2 - 4 minute; onderhoude 8 - 10 minute; voorbereide lees 2 - 3 minute; voorbereide mondelinge aanbieding, verslag, resensies 2 - 3 minute; onvoorbereide mondelinge aanbieding 2 - 3 minute; storievertel 5 - 7 minute; vergadering en prosedures 7 - 10 minute. (KABV 2011c:25)

Hieruit kan afgelei word dat alhoewel storievertelling voorgeskryf word van graad R tot graad 12, daar oor die algemeen min tyd in die klas daaraan afgestaan word. Om hierdie rede kan die kultuur van storievertelling in die gemeenskap des te meer 'n positiewe bydrae lewer tot alle partye in die gemeenskap.

Met die ontleding van die KABV se beskrywing van die werkswyse van storievertelling volgens skoolfases is die volgende bevind:

Graad R tot 3

Die KABV (2011a:24) ( Tabel 1 ) voldoen aan die voorskrif om individue van jongs af aan storievertelling bloot te stel. Die kurrikulum skryf voor dat leerders van graad R tot graad 3 na stories moet luister, stories moet dramatiseer, hul mening daaroor moet uitspreek en oop vrae daaroor moet beantwoord. Leerders moet ook stories vertel met 'n eenvoudige storielyn en verskillende karakters. Verder leer leerders die etiket rakende storievertelling, byvoorbeeld dat elkeen 'n beurt moet kry om te praat en dat die verteller nie in die rede geval mag word nie. Leerders word met ander woorde op 'n vroeë ouderdom aan stories en storievertelling blootgestel.

Dit is egter die deel waar leerders oor persoonlike ervarings en gevoelens praat wat van kardinale belang is om identiteit te versterk. Dit is belangrik om daarop te let dat hierdie aspek van storievertelling veral voorgeskryf word vir graad 1 en 2 in die KABV (2011a:24), maar navorsing (McAdams 2006a:76) het getoon dat individue op hierdie ouderdom nog nie hierdie soort storievertelling kan bemagtig nie. Volgens McAdams en Manczak (2015:429) is sekere vaardighede nodig om 'n narratiewe identiteit te konstrueer, maar op hierdie ouderdom beskik kinders nog nie oor dié vaardighede nie. Om byvoorbeeld 'n geïntegreerde lewensverhaal te konstrueer, moet die persoon weet hoe 'n tipiese lewe gestruktureer is, byvoorbeeld wat gebeur wanneer iemand die huis verlaat, die verwagte progressie van die huwelik en gesinsvorming en wat mense doen wanneer hulle aftree. Hierdie soort normatiewe verwagtinge bied 'n kulturele manuskrip vir 'n outobiografie. Habermas en Bluck (2000:749) het bevind dat mens op 'n jong ouderdom hierdie faktore, wat tot die lewensmanuskrip bydra, begin internaliseer, maar eers regtig begin leer oor hierdie deel van jou lewensmanuskrip in die vroeë volwasse stadium. Namate adolessensie bereik word, raak kinders al hoe beter toegerus om narratiewe te verskaf wat verduidelik hoe een gebeurtenis daaropvolgende gebeurtenisse in die lewe veroorsaak het, daartoe gelei het, daarin getransformeer het of op die een of ander manier betekenisvol daaraan verwant is. Verder het Habermas en De Silveira (2008:708) bevind dat die meer volwasse persoon 'n oorkoepelende tema, waarde of beginsel identifiseer wat die verskillende episodes van sy lewe integreer en die kern vorm van wie hy is en waaroor sy biografie handel. Hierdie vermoë van die storieverteller om te kan integreer is wat Habermas en Bluck (2000:749) "tematiese samehang" noem. Habermas en De Silveira (2008:718) het in hul ontleding van lewensverhale tussen die ouderdomme van agt en twintig jaar getoon dat kousale en tematiese koherensie relatief skaars is in outobiografiese vertellings vanaf die laat kinderjare en vroeë adolessensie, maar substansieel toeneem deur die tienerjare tot in vroeë volwassenheid. Daarbenewens het Habermas en De Silveira (2008:718) ook bevind dat ouer adolessente geneig is om duidelike en meer verhelderende inleidings en eindes in hul lewensverhale op te stel. Dit sluit in voorskoue, retrospektiewe besinning en ander merkers van volwasse outeurskap.

Graad 4 tot 6

Uit Tabel 2 blyk dit duidelik dat leerders in graad 4 tot 6 al die korrekte vaardighede aangeleer word om stories te vertel en daarna te luister. Die aanbevole tekstipes is egter kontemporêre, realistiese fiksie, tradisionele stories (mites en legendes, volksverhale en fabels), avontuurverhale, wetenskapfiksie, biografieë en historiese fiksie (KABV 2011b:17). Persoonlike vertellings kom met ander woorde nie hier voor nie. Leerders in hierdie grade word met ander woorde nie aan persoonlike vertellings blootgestel nie.

Wanneer Tabel 3 , waar die verspreiding van tekste vir graad 4 tot 6 aangedui word, egter bestudeer word, sien die leser dat stories wat persoonlike vertellings bevat, wel voorgeskryf word vir graad 4 en 5, maar nie vir graad 6 nie. Soos reeds opgemerk, is dit egter belangrik dat leerders op hierdie ouderdom reeds ingelei word om persoonlike vertellings te bemeester, want die kuns om persoonlike vertellings te beoefen, moet kumulatief toeneem soos wat leerders ouer word.

Graad 7 tot 9 en graad 10 tot 12

Tabelle 4 en 5 toon aan dat storievertel vir graad 7 tot 9 en graad 10 tot 12 onderskeidelik vyf tot sewe en agt tot tien minute moet duur. Daar kan egter nie 'n tydsduur aan persoonlike vertellings gekoppel word nie, omdat die persoon wat die storie vertel dalk van gebeure kan vertel wat sensitief van aard is en dit ongevoelig sal wees om die vertelling te onderbreek. Die klas kan moontlik ook nie 'n veilige omgewing wees om persoonlike vertellings uit te voer nie. Daar is egter ook nie plek in die voorgeskrewe kurrikulum om meer tyd aan storievertelling te bestee nie.

Die waarde van storievertelling lê in die volgende uittreksel uit die KABV Afrikaans Huistaal vir Graad 10-12 (2011d:10) opgesluit. Hierin word beklemtoon dat die luister- en praatvaardigheid sentraal staan in die leer van alle vakke, omdat dit die vaardigheid om inligting in te samel en te sintetiseer, kennis te konstrueer, probleme op te los en idees en menings te lug, ontwikkel. Volgens Vygotsky (1978) ondergaan kinders sekere stadiums van taal- en kognitiewe ontwikkeling. Wanneer kinders taal verwerf, verbeter hul vermoë om geredelik aan dialoë met ander deel te neem, terwyl die bemeestering van kultureel gewaardeerde vaardighede ook verbeter (Berk 2010:23). Hierdie vaardighede word met ander woorde tydens storievertelling opgeskerp en vasgelê, en storieverteltegnieke kan moontlik 'n invloed hê op leerders se algemene akademiese prestasies.

Dat storievertelling wat identiteit versterk (McAdams 2006b:84) eers effektief in vroeë volwassenheid aangeleer word, kan nie genoeg beklemtoon word nie. Daar word byvoorbeeld nie van kinders verwag om konkrete besluite te neem nie - hulle hoef nog nie beroepskeuses uit te oefen nie; dit word eers van jong volwassenes verwag. Storievertelling kan egter gebruik word sodat kinders wat in 'n negatiewe konteks grootword, weer kan droom of kan ontvlug, al is dit net in 'n fantasiewêreld waar dit beter gaan as in die werklike wêreld waarin hulle hulself bevind. In 'n fantasiewêreld is enigiets moontlik; daar kan die kind wat magteloos voel in sy of haar omstandighede, of oor iemand in sy of haar omstandighede, die kwade (bv. 'n boelie) oorwin. Rooikappie kan byvoorbeeld die wolf doodkap met 'n byl; Gouelokkies kan weghardloop vir die bere vir wie sy bang is of die drie varkies kan 'n pot kookwater kook en die wolf kan daarin val en doodgaan. Al is dit onrealisties, skep storievertelling 'n deur vir ontsnapping (McAdams 2006a:84).

In Tabelle 6 en 7 sien die leser dat storievertelling vir graad 10 en 11 onderskeidelik een uur in die skooljaar onderrig word, en dan is storievertelling ook nie deel van formele assessering nie. Die belangrike bevinding van McAdams (2006b:84) dat storievertelling eers in die tydperk van jong volwassenheid (graad 10-12) effektief aangeleer kan word, word met ander woorde glad nie in hierdie fase van jong volwassenes geïmplementeer nie. Volgens Arnett (2007:68) verwys jong volwassenes na persone van ongeveer 18 tot 25 jaar oud, wanneer hulle nie meer adolessente is nie, maar ook nog nie ten volle as volwassenes beskou kan word nie.

Storievertelling word in dieselfde asem as prysliedere genoem in Tabel 7 , wat daarop dui dat storievertelling handel oor tradisionele of kulturele stories en nie soseer oor persoonlike storievertelling nie. Alhoewel kulturele storievertelling waarde inhou en die leerder se identiteit versterk ten opsigte van die kulturele konteks waarbinne hy of sy tuishoort (Edwards 2009:20), versterk kulturele storievertelling nie noodwendig iemand se persoonlike identiteit nie. Dit is egter belangrik dat storievertelling by die self begin en later uitkring na die gemeenskap, en nie andersom nie (Van der Vyver 2018:65). Dus, indien ek nie weet wie ek is nie, kan ek myself nie plaas in die groter kulturele omgewing nie en gaan ek makliker saam met die stroom eerder as om my eie identiteit te laat geld wanneer nodig. In graad 12 se onderrigplan (KABV 2011d) kan daar geen teken van voorgeskrewe storievertelling gevind word nie; dus het die frekwensie van alle storievertelling verdwyn, en die belangrike aspek van persoonlike storievertelling wat juis in hierdie stadium van die leerder se lewe moet figureer, kom glad nie hier voor nie.

5. SAMEVATTING EN AANBEVELINGS

Uit McAdams (2006a:76) se benadering tot storievertelling is bevind dat jonger kinders nie hul lewensverhale met sukses kan vertel nie en dat die vertel van lewensverhale eers in vroeë adolessensie met sukses uitgevoer kan word.

Storievertelling beskik oor belangrike onderrigwaarde; onder andere leer leerders op 'n informele wyse hoe om beter te presteer, en bekom ook waardevolle kommunikasietegnieke. Daar kan dus tereg verklaar word dat storievertelling as 'n belangrike instrument aangewend kan word om identiteit te versterk.

Uit die bestudering van die KABV-dokumente vir graad R tot 12 kan die afleiding gemaak word dat daar wel 'n leemte ten opsigte van storievertelling en veral lewensverhaalvertellings in die kurrikulum voorkom. Hierdie leemte moet dan êrens ander s in die leerder se opvoeding ondervang word, omdat die lewensverhaal so 'n belangrike instrument is in die versterking van die individu se identiteit. Volgens die KABV word algemene storievertelling veral aangemoedig en aangeleer in die jonger grade. Persoonlike storievertelling of lewensverhale moet egter meer aandag geniet namate leerders ouer word.

Aangesien die klas nie altyd 'n veilige omgewing is vir persoonlike storievertellings nie en die onderwyser nie altyd in die klas tyd het om aandag aan storievertelling te gee nie, is 'n moontlike kreatiewe oplossing om storievertelling te akkommodeer in vennootskap met die gemeenskap. Fasiliteerders kan moontlik opgelei word om veilige storievertelomgewings te skep waar stories vertel kan word. Die gemeenskap skep sodoende 'n platform buite die skoolure, wanneer leerders hul stories ongehinderd kan vertel en 'n kultuur van storievertelling terselfdertyd in die gemeenskap gevestig kan word, aangesien dit ook op 'n meer gereelde basis kan geskied. Tog, om storievertelling volhoubaar te maak en as kultuur te vestig, moet die saadjie al van kleins af gesaai word en kinders op 'n jong ouderdom gedurig daaraan blootgestel word totdat hulle die waarde daarvan besef en spontaan aan storievertelling wil deelneem in vroeë volwassenheid. Die KABV slaag daarin om leerders vanaf 'n vroeë ouderdom aan die vaardighede van storievertelling bloot te stel. Daar word egter meer tyd aan persoonlike storievertelling afgestaan op 'n ouderdom waar leerders nog nie volwasse genoeg is om dit ten volle te benut nie. Persoonlike storievertelling moet kumulatief toeneem van graad R tot 12, maar in die KABV vind die teenoorgestelde plaas.

Wanneer persoonlike storievertelvaardighede egter in die regte volgorde van belangrikheid plaasvind, sal vertellers aan toehoorders kan oordra wat hulle uit eie ervaring geleer het. Dit is daarom belangrik om leerders aan alle komponente van storievertelling bloot te stel in die laer grade, sodat persoonlike storievertelling 'n natuurlike uitvloeisel sal word vanaf graad 10. Wanneer storievertelling in vennootskap met die gemeenskap aangeleer word, behoort dit nie 'n vreemde konsep te wees vir 'n leerder wat in die klaskamer daarmee gekonfronteer word nie (Van der Vyver 2020:854). Sodoende behoort storievertelling die onderwyser se taak in die klas te vergemaklik. Storievertelling behoort daarom as kultuur in vennootskap in die gemeenskap gevestig te word, sodat dit as bate kan dien vir al die rolspelers in die vennootskap tussen die drie vernaamste invloedsfere (familie, skool en gemeenskap). Dié vennootskap moet met ander woorde van so 'n aard wees dat dit die medium word waardeur die deelnemer se identiteit blootgelê word. Dit is egter belangrik dat die deelnemer in staat gestel word om andere tot dieselfde blootlegging van identiteit te lei, sodat die vennootskap wedersydse voordeel vir al die rolspelers sal inhou.

BIBLIOGRAFIE

Anon. 2015. Storytelling: the crucial curriculum. https://www.nalibali.org/storytelling-the-crucial-curriculum-2 [4 August 2015]. [ Links ]

Arnett, JJ. 2007. Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives , 1(2):68-73. [ Links ]