- No menu assigned!

- Submit your history essay

History Hub is a publisher dedicated to providing free and accessible scholarly materials to students and academics around the world. By publishing with us your work can reach a growing audience. We take pride in getting back to authors within 48 hours, and in responding to everyone who sends us content – regardless of our decision.

Before you go forward, please note: • We do not mind what variant of English you write in, but your grammar and spelling must be at a publishable standard upon receipt. • We do not have the editorial resources to translate submissions from other languages into English. • We do not charge our authors any fees. Nor do we pay authors a fee / royalty for anything we publish. • Submissions must not be already published elsewhere. • Submission initiates the expenditure of our time on your behalf – and thereby gives your consent for possible publication. • All submissions are published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-4.0 license. Copyright remains with the author(s).

Ready to submit your essay for publication?

Send your essay to, write@historyhub.info, why publish your history essay on history hub.

History Hub aims to make academic papers freely available to everyone. By publishing your essay on History Hub, you help to build an open access platform designed to help thousands of scholars all around the world. Additionally, you’re able to present your work in front of thousands of monthly website visitors. Once your history essay is published, you can add it to your portfolio and use it as a reference during an interview process.

As History Hub continues to grow it’s fair to assume that the number of scholars and academics reading your essay will also increase. Therefore, you may find it easier to expand your academic network once you begin publishing your work on History Hub.

With that in mind, the best reason to publish your essay here is to help students and scholars deepen their understanding of history.

What makes a great history essay?

Not all essays are created equal. Nevertheless, a few golden rules regarding content and formatting, not only increase your chances of being published on History Hub, but also ensure that your academic work reaches a high standard. Let’s start with the easy stuff:

Perfectly format your history essay

Proper formatting is absolutely crucial for academic papers. Here are a few golden rules to abide by:

- Limit paragraphs to four sentences

- Limit sentences to three lines

- Include a new subheading after 5-6 paragraphs

- Include a Bibliography at the end of your history essay

- Include footnotes

Keeping these five rules in mind will help your readers better understand the heft of your argument. Short sentences and paragraphs help to capture the attention of the reader. On the contrary, long, never ending sentences make readers drift off and lose focus.

Subheadings help the reader to understand the gist of your argument at a glance. Especially in an online environment, readers are often looking for answers to specific questions. By adding subheadings every few paragraphs, you ensure that the content of those paragraphs can be easily ascertained.

Using sources to underline arguments

The study of history is dependent on the proper use of primary and secondary sources. In order for an essay to reach an acceptable academic level, numerous primary and secondary sources should be included throughout the essay.

In this context, a primary source would refer to the account of an individual that was present at the time. Diary entries and newspaper reports are classic primary sources, but many others exist.

Secondary sources refer to interpretations of primary sources. When Ian Kershaw makes inferences about the nature of Nazi Germany for example, he is using the evidence he collected from primary sources to form an opinion. Quoting Kershaw in an essay would be to use a secondary source.

Whenever a source, primary or secondary, is used in a history essay, it is crucial to apply the relevant footnote in order to demarcate it correctly. A complete list of used sources should be included as a Bibliography at the end of the essay.

What’s the publishing process like?

At History Hub we endeavour to maintain a level of excellence both in our communication and in the essays that are published.

Once a history essay is submitted (send to write@historyhub.info), we perform a first, perfunctory review before getting back to the author. In this first step we check if:

- the topic is relevant to the field of History

- the essay is in the correct format (Google Doc or Word Doc)

- the level of English is appropriate

- the essay is long enough (Minimum 1,300 words)

Within 24 hours of receiving your essay, we will get back to you with regards to these four points. If everything looks good we move to the detailed review phase.

The detailed review phase typically takes an additional 48 hours. The essay is proofread multiple times by members of the team and the arguments that are laid out in the essay are examined. Due to our lack of resources, please note that we are unable to check your primary and secondary sources. We therefore urge you to double-check all references before submitting your history essay.

In the detailed review phase we check if:

- the essay makes a coherent argument

- a sufficient number of primary and secondary sources are used

- the essay is divided into an introduction, middle and conclusion

If necessary we will get back to you and ask for revisions and/or clarifications. If the essay makes a coherent argument, uses a sufficient number of primary and secondary sources, and is divided into the correct sections, we will publish the essay.

Once the essay is published, you will receive an email from us with the link. Please note that we may add informative links to the essay whenever relevant.

Example: “…smugglers associated with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) gained traction”, would turn into “…smugglers associated with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) gained traction”.

This is designed to give the reader easy access to additional context, which helps clarify the argument being made in the essay.

Finally, rest assured that you maintain all rights to your work. This means that if you’d like us to make edits to your essay after publication, or remove it from the website, we will endeavour to do so in a timely manner.

Useful links

- Frequently asked questions

- History Essays

Recent posts

- You may submit a paper to The Concord Review if you completed the paper before finishing secondary school.

- You must be the sole author. If at any point during the review process we discover that your work is not an original paper, we will notify your school, which could result in withdrawal of college admissions, among other things.

- The paper must be in English and may not have been previously published except in a publication of a secondary school that you attended.

- Essays should be in the 5,000-9,000 (or more) word range, with Turabian (Chicago) end notes and bibliography (we do not accept papers with footnotes). The average paper that we publish is over 8,000 words and the longest paper we have published was 21,000 words (on the Mountain Meadows Massacre) .

- Essays may be on any historical topic, ancient or modern, domestic or foreign, and must be submitted electronically.

- Essays should have the notes and bibliography placed at the end ( Chicago Style ). Use only Arabic numerals for endnotes, not Roman numerals. URLs in endnotes should have the accessed date noted per Turabian style. All endnotes should end with a period.

- Use only one single font family (e.g., Times or New Baskerville, but not both) throughout. You may use any font styles (bold, italic, superscript, etc.) within that single font family. If you need non-english characters or diacritics not available in your main font, you may use other fonts for the instance of a non-english word or diacritic.

- Do not break any line in the middle using a carriage return. Only use returns to end paragraphs.

- The Concord Review does not publish charts, photos, graphs or other graphics in essays. Please remove them before submitting.

- Files must be in MS Word or RTF format only . We DO NOT accept Apple Pages , GoogleDocs , PDF , etc. You must convert them to MS Word or RTF before submitting.

- The filename of your document should be your first and last name followed by an underscore and the first 3 words (ONLY) of your essay title . Include spaces, etc. Use an underscore in place of a colon in the filename. DO NOT INCLUDE COMMAS or any other punctuation . Your first and last name should be the ones you used in filling out the form .

- For example, if your name is Marie Jones , and your essay is titled, "The Founding Fathers: Some Bicentennial Reflections" then your filename would be:

- Marie Jones_The Founding Fathers .docx

- thefoundingfathers.docx

- historypaperforMrSmith, purposes, methods, and devices through time.PDF

- Submit only one file . Endnotes and Bibliography should be included at the end of the essay document .

- Please complete our online Submission form (below) and then pay the submission fee (see prices below) after completing the form. The author will receive the next four issues of the journal's Electronic Edition. For an additional fee plus shipping and handling, the author can receive the next four issues of the Print Edition.

We will typeset papers in InDesign here.

For issues regarding the application form, file formats, etc. contact [email protected]

For more information about the content of your essay contact [email protected] [email protected] [email protected]

Author Benefits Each author who submits a paper and submission fee, receives the next four issues of the journal in eBook form. For an additional $30 plus shipping costs, authors may receive the Print Edition of the journal. Authors may purchase copies of the issue in which his or her essay is published in our bookstore . Individual reprints of their published essay (TCR Singles) can be created with a minimum order of 12 copies. Many authors have included their reprints with their college application materials. The Concord Review is the first and only journal in the world which publishes the academic work of secondary students, so our reprints usually make a distinctive contribution to an author's college application materials. Academic Standards The best way to judge the quality of the history essays we have published is to read several of the issues of the journal. We have published essays of fewer than 4,000 words, but we also receive and have published essays of 21,000 words. The average is about 8,500 words, with Turabian (Chicago) endnotes and bibliography. We advise that the author should prepare with considerable reading on the topic and that the essay go through at least one draft before it is polished and proofread for submission. We have not yet received essays from history students at all of the perhaps 40,000 eligible secondary schools around the world, but there is already a high level of international competition, and we have published essays from 46 countries so far.

US is for shipping the journal to the US. Choose this if you want the journal shipped inside the US.

International is for shipping outside the US, choose this if you want the journal shipped outside the US.

Select membership level

Home | About | Contact Us | FAQ | Links

Publishing your work

Written in 2014-15 by Professor Peter Mandler (RHS President, 2012-16)

Everyone wants to publish their work, and not only for ‘career progression’; what’s the point of doing your research if no-one reads it? By the same token, you want to publish your work in places and formats that will reach the widest audiences. But if this were all publishing was about, then you would just post your work online (on a site such as academia.edu or on your own webpage or site) and let people come to it.

In fact, publishing isn’t just about disseminating your work – it’s about improving it, and about ‘kitemarking’ it (getting marks of quality attached to it that will suggest to potential readers that it’s worth reading). It is these two additional criteria that cause many historians – especially those just starting out in their publishing career – to submit to journals. There are other ways of publishing article-length papers – notably as chapters in books.

Ultimately, most historians want to tackle a ‘long-form’ publication similar to their PhD thesis – that is, a book of one’s own. These are the main forms of publication, but they hardly exhaust the range of outlets – there are many other formats. If you’re a UK scholar, you’ll also be interested in thinking about how your publications are likely to be assessed for purposes of the REF.

1. Journals

Journals provide a miraculously free and civic-spirited service that aims to improve your work – peer review. When you submit a paper to a journal, the editors ought to send it out to at least two peer reviewers (sometimes several – practices differ). They ought to have some specialist knowledge of your subject. If your subject is controversial, one ought to be ‘on your side’, another perhaps hostile or at least neutral. Ideally, peer-review is ‘double-blind’ – the reviewer doesn’t know your identity, you don’t know theirs. READ MORE

Submitting to a journal

What makes a good journal article? First, it must stand on its own. It may be a version of a chapter of a PhD dissertation, but it has to be self-contained. Second, it ought to have a strong and distinctive argument. The standard way to demonstrate this is by reference to the historiography – but it’s not enough (or even, really, at all persuasive) to say that your subject has been ‘neglected’ by the historiography. READ MORE

Publishing in a journal

Once a journal has accepted your work, you still have some time to polish it up (e.g. by adding references to the most recently published work, or by tinkering with your prose, or by addressing lesser criticisms in your readers’ reports). Most journals now process accepted manuscripts through a software system that will let you upload your final manuscript and will subsequently lead you through the publication process. READ MORE

After publication

Nothing at all may happen. If you’re lucky, a few readers may write to you – expressing interest, asking questions about your sources and methods, perhaps disagreeing with you. Mostly, though, readers read and digest on their own. READ MORE

2. Chapters in books

Unlike the practice of many other disciplines, historians publish a lot in collections of essays – normally not all their own essays, but collections ‘from divers hands’ edited by one or two colleagues. READ MORE

3. A book of one’s own

For good reasons, a book of your own – now sometimes called a ‘monograph’, although this really only means a specialist work by a single author (and so technically could apply to a journal article) – is widely seen as the gold standard of historiography. READ MORE

Publishing a Book (I)

Book publishing remains fairly traditional, not as affected by the digital revolution as journal publishing. As with journals, however, there are a range of book publishers that you can probably array in a quality sequence depending on your own experience of your own field. Generally, though, they break down into three types: i) university presses; ii) big commercial presses; iii) boutique commercial presses. READ MORE

Publishing a book (II)

If an editor has agreed to review a proposal on its own, you may get a response in a month or so, as a short proposal does not receive a lot of scrutiny from reviewers. If you have submitted a complete manuscript, six months is not unusual. It takes a long time for a peer reviewer to find the space to give a full book manuscript the attention it deserves. READ MORE

Unlike with journal articles, you are almost guaranteed to get some feedback, at least within the first year, in the form of book reviews. Your publisher will ask you for a list of journals that are relevant to your book – you’re entitled to give them a reasonably long list, though make sure that they really are relevant and do publish book reviews. READ MORE

4. Other formats

A very large majority of the work published by historians appears in one of these three formats – journal articles, chapters in books, books. These formats allow for the evidence intensive and subject-extensive treatment that history favours. But there are lots of other ways to publish, especially online, and these alternative formats tend to cater to other needs than the simple presentation of research. READ MORE

If you are a UK scholar, or seeking employment in the UK, you will need to pay some minimal attention to the REF (the Research Excellence Framework, the current name for the periodic assessment of academic research undertaken by the UK funding bodies). READ MORE

HEADER IMAGE: A printer’s workshop: on the left a printing press, on the right and centre workmen engaged in various tasks, the scene numbered for a key. Engraving after L.J. Goussier. Wellcome Trust, public domain

The Public Historian, is a quarterly journal sponsored by the National Council on Public History and the University of California, Santa Barbara, and is published by the University of California Press. It is the flagship journal in the field of public history. It emphasizes original research, fresh conceptualizations, and new viewpoints. The journal’s contents reflect the considerable diversity of approaches to the definition and practice of public history.

The Public Historian provides practicing professionals and others the opportunity to report the results of research and case studies and to address the broad substantive and theoretical issues inherent in the practice of public history. The journal aims to provide a comprehensive look at the field.

The Public Historian publishes a variety of article types, including research articles, essays, and reports from the field. Research articles deal with specific, often comparatively framed, public historical issues. They employ public history methodologies (material culture analysis, oral history, participant observation) in addition to traditional historical research to shed new light on historical questions and issues. These articles should be around thirty pages double-spaced, exclusive of footnotes (about 10,000 to 12,000 words). Essays are reflective commentaries on topics of interest to public historians. Their length varies, but they are usually about twenty-five pages. Reports from the Field are intended to convey the real-world work of public historians by highlighting specific projects or activities in which the author is directly involved; these articles may describe new or ongoing projects, introduce or assess new methodologies, or bring in-the-field dilemmas (methodological, ethical, and historical) into print. Reports from the Field vary widely in length (from about fifteen to thirty pages). Additionally, The Public Historian occasionally publishes roundtables, which are shorter essays in conversation with each other about a specific topic.

In its review section, The Public Historian assesses current publications by and of interest to public historians, including government publications, cultural resources management reports, and corporate histories, as well as scholarly and trade press publications. The journal also reviews films and documentaries, digital and electronic media productions, museums, exhibitions, and podcasts. We do not accept unsolicited reviews; we do, however, welcome suggestions for material to review (please email [email protected] ). If you are interested in becoming a reviewer, please visit the Reviewer page.

The editors welcome the submission of manuscripts by all those interested in the theory, teaching, and practice of public history, both in the United States and internationally. We are looking for manuscripts that make a significant contribution to the definition, understanding, and/or professional and intellectual progress of the field of public history. We conceive of the term public history broadly, as involving historical research, analysis, and presentation, with some degree of explicit application to the needs of contemporary life.

Research articles, essays, and reports from the field are subject to anonymous peer review and revisions will be suggested before the editors will accept an article for publication.

Only manuscripts not previously published will be accepted. Submitted articles must not be under consideration at another journal. Authors must agree not to publish elsewhere, without explicit written consent, an article accepted for publication in The Public Historian.

The Public Historian encourages letters to the editor that expand the discussion of topics covered in the journal. If a letter specifically concerns an article or review published in The Public Historian , the author or reviewer will be invited to respond. Letters responding to reviews may not exceed 250 words; letters responding to articles may not exceed 750 words. The editors reserve the right to refuse to publish any letter whose tone or content are inconsistent with the conventional standards of scholarly discourse expected in a historical journal.

Please note that all authors whose papers are accepted for publication are required to sign an Author Agreement.

Please submit manuscripts and letters to the editors by email to the editor at the address below.

See guidelines here.

Editorial Offices: Sarah H. Case, Editor (UC Santa Barbara) Teresa Barnett, Special Editor (independent historian) Jennifer Dickey, Book Review Editor (Kennesaw State University) Jennifer Scott, Museum and Exhibitions Editor (Urban Civil Rights Museum in Harlem) Taylor Stoermer, Film and Digital Editor (Johns Hopkins University)

Contact: Sarah Case, Editor Department of History University of California Santa Barbara, California 93106 805/893-3667 E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations

- Recent Content

- Browse Issues

- All Content

- Info for Authors

- Info for Reviewers

- Info for Advertisers

- Info for Librarians

- Editorial Team

- Online ISSN 1533-8576

- Print ISSN 0272-3433

- Copyright © 2024

Stay Informed

Disciplines.

- Ancient World

- Anthropology

- Communication

- Criminology & Criminal Justice

- Film & Media Studies

- Food & Wine

- Browse All Disciplines

- Browse All Courses

- Book Authors

- Booksellers

- Instructions

- Journal Authors

- Journal Editors

- Media & Journalists

- Planned Giving

About UC Press

- Press Releases

- Seasonal Catalog

- Acquisitions Editors

- Customer Service

- Exam/Desk Requests

- Media Inquiries

- Print-Disability

- Rights & Permissions

- UC Press Foundation

- © Copyright 2024 by the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Privacy policy Accessibility

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Write a History Essay

Last Updated: December 27, 2022 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Emily Listmann, MA . Emily Listmann is a private tutor in San Carlos, California. She has worked as a Social Studies Teacher, Curriculum Coordinator, and an SAT Prep Teacher. She received her MA in Education from the Stanford Graduate School of Education in 2014. There are 8 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 242,899 times.

Writing a history essay requires you to include a lot of details and historical information within a given number of words or required pages. It's important to provide all the needed information, but also to present it in a cohesive, intelligent way. Know how to write a history essay that demonstrates your writing skills and your understanding of the material.

Preparing to Write Your Essay

- The key words will often need to be defined at the start of your essay, and will serve as its boundaries. [2] X Research source

- For example, if the question was "To what extent was the First World War a Total War?", the key terms are "First World War", and "Total War".

- Do this before you begin conducting your research to ensure that your reading is closely focussed to the question and you don't waste time.

- Explain: provide an explanation of why something happened or didn't happen.

- Interpret: analyse information within a larger framework to contextualise it.

- Evaluate: present and support a value-judgement.

- Argue: take a clear position on a debate and justify it. [3] X Research source

- Your thesis statement should clearly address the essay prompt and provide supporting arguments. These supporting arguments will become body paragraphs in your essay, where you’ll elaborate and provide concrete evidence. [4] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Your argument may change or become more nuanced as your write your essay, but having a clear thesis statement which you can refer back to is very helpful.

- For example, your summary could be something like "The First World War was a 'total war' because civilian populations were mobilized both in the battlefield and on the home front".

- Pick out some key quotes that make your argument precisely and persuasively. [5] X Research source

- When writing your plan, you should already be thinking about how your essay will flow, and how each point will connect together.

Doing Your Research

- Primary source material refers to any texts, films, pictures, or any other kind of evidence that was produced in the historical period, or by someone who participated in the events of the period, that you are writing about.

- Secondary material is the work by historians or other writers analysing events in the past. The body of historical work on a period or event is known as the historiography.

- It is not unusual to write a literature review or historiographical essay which does not directly draw on primary material.

- Typically a research essay would need significant primary material.

- Start with the core texts in your reading list or course bibliography. Your teacher will have carefully selected these so you should start there.

- Look in footnotes and bibliographies. When you are reading be sure to pay attention to the footnotes and bibliographies which can guide you to further sources a give you a clear picture of the important texts.

- Use the library. If you have access to a library at your school or college, be sure to make the most of it. Search online catalogues and speak to librarians.

- Access online journal databases. If you are in college it is likely that you will have access to academic journals online. These are an excellent and easy to navigate resources.

- Use online sources with discretion. Try using free scholarly databases, like Google Scholar, which offer quality academic sources, but avoid using the non-trustworthy websites that come up when you simply search your topic online.

- Avoid using crowd-sourced sites like Wikipedia as sources. However, you can look at the sources cited on a Wikipedia page and use them instead, if they seem credible.

- Who is the author? Is it written by an academic with a position at a University? Search for the author online.

- Who is the publisher? Is the book published by an established academic press? Look in the cover to check the publisher, if it is published by a University Press that is a good sign.

- If it's an article, where is published? If you are using an article check that it has been published in an academic journal. [8] X Research source

- If the article is online, what is the URL? Government sources with .gov addresses are good sources, as are .edu sites.

- Ask yourself why the author is making this argument. Evaluate the text by placing it into a broader intellectual context. Is it part of a certain tradition in historiography? Is it a response to a particular idea?

- Consider where there are weaknesses and limitations to the argument. Always keep a critical mindset and try to identify areas where you think the argument is overly stretched or the evidence doesn't match the author's claims. [9] X Research source

- Label all your notes with the page numbers and precise bibliographic information on the source.

- If you have a quote but can't remember where you found it, imagine trying to skip back through everything you have read to find that one line.

- If you use something and don't reference it fully you risk plagiarism. [10] X Research source

Writing the Introduction

- For example you could start by saying "In the First World War new technologies and the mass mobilization of populations meant that the war was not fought solely by standing armies".

- This first sentences introduces the topic of your essay in a broad way which you can start focus to in on more.

- This will lead to an outline of the structure of your essay and your argument.

- Here you will explain the particular approach you have taken to the essay.

- For example, if you are using case studies you should explain this and give a brief overview of which case studies you will be using and why.

Writing the Essay

- Try to include a sentence that concludes each paragraph and links it to the next paragraph.

- When you are organising your essay think of each paragraph as addressing one element of the essay question.

- Keeping a close focus like this will also help you avoid drifting away from the topic of the essay and will encourage you to write in precise and concise prose.

- Don't forget to write in the past tense when referring to something that has already happened.

- Don't drop a quote from a primary source into your prose without introducing it and discussing it, and try to avoid long quotations. Use only the quotes that best illustrate your point.

- If you are referring to a secondary source, you can usually summarise in your own words rather than quoting directly.

- Be sure to fully cite anything you refer to, including if you do not quote it directly.

- Think about the first and last sentence in every paragraph and how they connect to the previous and next paragraph.

- Try to avoid beginning paragraphs with simple phrases that make your essay appear more like a list. For example, limit your use of words like: "Additionally", "Moreover", "Furthermore".

- Give an indication of where your essay is going and how you are building on what you have already said. [15] X Research source

- Briefly outline the implications of your argument and it's significance in relation to the historiography, but avoid grand sweeping statements. [16] X Research source

- A conclusion also provides the opportunity to point to areas beyond the scope of your essay where the research could be developed in the future.

Proofreading and Evaluating Your Essay

- Try to cut down any overly long sentences or run-on sentences. Instead, try to write clear and accurate prose and avoid unnecessary words.

- Concentrate on developing a clear, simple and highly readable prose style first before you think about developing your writing further. [17] X Research source

- Reading your essay out load can help you get a clearer picture of awkward phrasing and overly long sentences. [18] X Research source

- When you read through your essay look at each paragraph and ask yourself, "what point this paragraph is making".

- You might have produced a nice piece of narrative writing, but if you are not directly answering the question it is not going to help your grade.

- A bibliography will typically have primary sources first, followed by secondary sources. [19] X Research source

- Double and triple check that you have included all the necessary references in the text. If you forgot to include a reference you risk being reported for plagiarism.

Sample Essay

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.historytoday.com/robert-pearce/how-write-good-history-essay

- ↑ https://www.hamilton.edu/academics/centers/writing/writing-resources/writing-a-good-history-paper

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/the_writing_process/thesis_statement_tips.html

- ↑ http://history.rutgers.edu/component/content/article?id=106:writing-historical-essays-a-guide-for-undergraduates

- ↑ https://guides.lib.uw.edu/c.php?g=344285&p=2580599

- ↑ http://www.hamilton.edu/documents/writing-center/WritingGoodHistoryPaper.pdf

- ↑ http://www.bowdoin.edu/writing-guides/

- ↑ https://www.wgtn.ac.nz/hppi/publications/Writing-History-Essays.pdf

About This Article

To write a history essay, read the essay question carefully and use source materials to research the topic, taking thorough notes as you go. Next, formulate a thesis statement that summarizes your key argument in 1-2 concise sentences and create a structured outline to help you stay on topic. Open with a strong introduction that introduces your thesis, present your argument, and back it up with sourced material. Then, end with a succinct conclusion that restates and summarizes your position! For more tips on creating a thesis statement, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Lea Fernandez

Nov 23, 2017

Did this article help you?

Matthew Sayers

Mar 31, 2019

Millie Jenkerinx

Nov 11, 2017

Oct 18, 2019

Shannon Harper

Mar 9, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Out of the Classroom and Into the World: 70-Plus Places to Publish Teenage Writing and Art

By Katherine Schulten

- Nov. 15, 2018

June, 2021: Updated with new opportunities.

When we ask teachers why they bring their classes to our site, we always hear one answer first: Posting in our public forums gives young people an “authentic audience” for their voices and ideas.

We’re honored to serve that role, and this week we’ll be talking about it on a panel at the National Council of Teachers of English conference . As a companion to our talk, on the theme of “Why You Should Publish Student Work — and Where and How to Do It,” we’ve compiled this list of opportunities specifically for teenage writers and visual artists. We hope, with your help, to crowdsource even more.

The list begins with our own offerings and those of our N.C.T.E. panel partner, the Scholastic Art & Writing Awards , and goes on to name dozens more that are open to young people in the United States — though many, including ours, also accept work from students around the world.

Please note what we did NOT include: In-person events or competitions; sites that do not seem to be taking submissions now or in the near future; opportunities open only to those from a specific state or region; opportunities open only to members of specific organizations; or competitions that require the use of paid products.

But, of course, we know this list is incomplete. What should we add? Let us know in the comments, or by writing to [email protected], and thank you.

Note: The descriptions below have been taken directly from the sites themselves. Please check the rules and requirements for each to decide if they are right for your students.

Places to Submit Teenage Writing and Visual Art

★ The New York Times Learning Network

Daily writing prompts:

Our Student Opinion question and Picture Prompt offer anyone 13 to 19 years old a place to publicly post writing that is read by our editors and other students around the world. We are not looking for formal work here; instead, we encourage students to use these forums to hone their voices, ideas and opinions; show us their thinking; and participate in civil discussion about issues from politics to pop culture. Each week, we publish a roundup of favorite responses .

Annual contests:

Our annual contests are places to submit more formal work across genres. Here is what we are offering in the 2020-21 school year, but please visit our Contest Calendar to find details, related lesson plans, and links to the work of the winners for each as they are announced: Special Contest: Coming of Age in 2020 Election 2020: Civil Conversation Challenge Personal Narrative Writing Contest Vocabulary Video Contest Review Contest STEM Writing Contest Editorial Contest Podcast Challenge Summer Reading Contest

★ Scholastic Art & Writing Awards

The nation’s longest-running and most prestigious recognition program for creative teenagers in grades 7 to 12. In 2018, students submitted nearly 350,000 works of visual art and writing to the Scholastic Awards; more than 90,000 works were recognized at the regional level and celebrated in local exhibitions and ceremonies. The top art and writing at the regional level were moved onto the national stage, where more than 2,800 students earned National Medals. National Medalists and their educators were celebrated at the National Ceremony at Carnegie Hall in New York City. Categories include: Critical Essay ; Dramatic Script ; Flash Fiction ; Humor ; Journalism ; Novel Writing ; Personal Essay & Memoir ; Poetry ; Science Fiction & Fantasy ; Short Story ; Writing Portfolio (graduating seniors only) ; Architecture & Industrial Design ; Ceramics & Glass ; Comic Art ; Design ; Digital Art ; Drawing & Illustration ; Editorial Cartoon ; Fashion ; Film & Animation ; Jewelry ; Mixed Media ; Painting ; Photography ; Printmaking ; Sculpture ; Video Game Design ; Art Portfolio (graduating seniors only) and Future New .

★ The Adroit Journal

The journal has its eyes focused ahead, seeking to showcase what its global staff of emerging writers sees as the future of poetry, prose and art. We’re looking for work that’s bizarre, authentic, subtle, outrageous, indefinable, raw, paradoxical. We’ve got our eyes on the horizon.

★ Amazing Kids Magazine

The online publication is known for featuring quality, creative, thoughtful and often thought-provoking written and artistic work written and edited by children and teenagers. Accepts writing, art, photography or videography from young people who are 5 to 18 years old.

★ The Apprentice Writer

The best writing and illustrations from entries we receive each year from secondary schools throughout the United States and abroad. Every September we send copies printed by The Patriot News in Mechanicsburg, Pa., to approximately 3,000 schools. Susquehanna University and the Writers Institute invite high school students to submit fiction, memoir, personal essay, photography and/or poetry.

★ The Daphne Review

Publishes the work of high-school-age writers and artists from around the globe. All forms of original writing and art are accepted as submissions for our biannual journal.

★ elementia

elementia is a literary arts magazine published to represent and uplift young adults. We accept original poetry, fiction, nonfiction, graphic stories, photography and illustrations.

Kalopsia is a literary and arts journal run by students from all over the world who aim to promote art and writing among (seemingly) ordinary people.

An international teen anthology of poetry and art. In print for 20 years, we accept submissions from teenagers from around the world. Each year we publish the best of all entries received.

★ The NAACP’s Afro-Academic, Cultural, Technological and Scientific Olympics (ACT-SO)

A yearlong achievement program designed to recruit, stimulate, and encourage high academic and cultural achievement among African-American high school students. ACT-SO includes 32 competitions in STEM, humanities, business, and performing, visual and culinary arts. Almost 300,000 young people have participated from the program since its inception.

★ National Young Arts Competition

The National YoungArts Foundation (YoungArts) was established in 1981 to identify and nurture the most accomplished young artists in the visual, literary, design and performing arts, and assist them at critical junctures in their educational and professional development. YoungArts’ signature program is an annual application-based award for emerging artists ages 15 to 18 or in grades 10 to 12 from across the United States in categories that include cinematic arts; classical music; dance; design arts; jazz; photography; theater; visual arts; voice; and writing.

★ Parallax Literary Magazine

Parallax Literary Magazine has been published by the Creative Writing department of Idyllwild Arts Academy since 1997. Idyllwild Arts Academy is a college preparatory boarding high school dedicated to the passion of young artists. Created, designed, and run by students, Parallax has always championed the high school writer by publishing the best of Idyllwild students’ creative writing and visual art. In 2011 Parallax expanded by adding an online component, which accepts submissions from high school students worldwide. The website also showcases student book reviews and writer interviews for the first time.

★ Periphery

A multilingual student-founded magazine for high schoolers living in the outer neighborhoods of cities across America.

★ River of Words: Youth Art and Poetry Inspired by the Natural World

Our free, annual, international youth poetry and art contest — the largest in the world — inspires children ages 5 to 19 to translate their observations into creative expression.

★ Sandpiper

Sandpiper is a journal of literature and art devoted to uplifting the voices of those emerging and underrepresented in the literary scene, including but not limited to those of class, race, ability, gender, sexual orientation, and intersectional identity. However, all submissions are welcome. Sandpiper accepts poetry, prose, art, and photography.

★ Skipping Stones

We are a nonprofit magazine for youth that encourages communication, cooperation, creativity and celebration of cultural and environmental richness. It provides a playful forum for sharing ideas and experiences among youth from different countries and cultures. We are an ad-free, ecologically-aware, literary magazine printed on recycled paper with soy ink. Accepts many kinds of writing, including essays, stories, letters to the editor, riddles and proverbs, as well as drawings, paintings and photos.

A national teen magazine, book series, and website devoted entirely to teenage writing, art, photos, and forums. For over 25 years, Teen Ink has offered teenagers the opportunity to publish their creative work and opinions on issues that affect their lives — everything from love and family to school, current events, and self-esteem. We have no staff writers or artists; we depend completely on submissions from teenagers around the world for our content. Teen Ink has the largest distribution of any publication of its kind.

★ #USvsHate

Students are invited to create public anti-hate messages in any media for their school communities. Our national challenge then amplifies student voices for a nationwide audience. You can submit 5 entries max per class, to each challenge! In 2020-21, our #USvsHate challenge deadlines are December 11 and March 12.

Places to Submit Teenage Writing

Across Genres

★ The Adroit Prizes for Poetry and Prose

The Adroit Prizes are awarded annually to two students of secondary or undergraduate status. We’re fortunate to receive exceptional work from emerging writers in high school and college, and the best of the best will be recognized by the Adroit Prizes.

★ Bennington College Young Writer Awards

Bennington launched the Young Writers Awards to promote excellence in writing at the high school level. Our goal with this competition is to recognize outstanding writing achievement by high school students. Each year, students in the 10th, 11th and 12th grades are invited to enter poetry, fiction or nonfiction.

★ Cathartic Youth Literary Magazine

An open space for youth writing & mental health discussion

★ The Creative Writing Awards

A scholarship program from Penguin Random House, in partnership with We Need Diverse Books, dedicated to furthering the education of students with unique and diverse voices. Open to seniors attending a public high school in the United States, five first-place $10,000 prizes are awarded in the categories of fiction/drama; poetry; personal essay/memoir; and spoken-word poetry, through the Maya Angelou Award. In recognition of the Creative Writing Awards previously being centered in New York City, the competition awards an additional first-place prize to the top entrant from the NYC area. Runners up are also honored.

Ember is a semiannual journal of poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction for all age groups. Submissions for and by readers aged 10 to 18 are strongly encouraged.

★ Ephimiliar

Created and edited by teenagers, Ephimiliar focuses on work by unpublished voices and students of all ages. We publish on a rolling basis at the convenience of everyone’s urgent yet sporadic writing processes. We are open to working with writers to edit a submission that we feel is a near-fit because we know that neither party would benefit from that rejection.

★ Hanging Loose Press

Fiction and poetry for a general audience, but has a regular section devoted to writing by talented high school writers.

★ Hypernova Lit

Hypernova Lit is an online journal dedicated to publishing the writing and visual art of teenagers. We seek to cast light on the brilliant work produced by teenagers. We are deeply committed to honesty and fearlessness in the work we publish, with a particular emphasis on teenagers telling their own difficult truths. Out of respect for our writers and artists, we do not censor for language or content.

★ The Foredge Review

A literary magazine for young writers with a focus on those in Asian countries, The Foredge Review aims to support teen interest in writing and reading by providing a platform for receiving recognition. We welcome submissions of poetry, flash fiction, and creative nonfiction from anyone 13-18.

★ NCTE Achievement Awards in Writing

To encourage high school juniors to write and to publicly recognize the best student writers.

★ The Norman Mailer High School Writing Award

Since 2009, the Norman Mailer Center has collaborated with the National Council of Teachers of English to present the Mailer Student and Teacher Writing Awards. Awards are given for fiction, nonfiction writing, and poetry. National winners in each category receive a cash prize presented at an award ceremony. Recognition is also extended to writers whose work earns top scores in early evaluation rounds.

★ Polyphony Lit

A student-run, international literary magazine for high school writers and editors, which invites submissions of poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction from high school students worldwide. Our student editors provide feedback to all submissions, including the ones we do not accept for publication. In addition, we offer two other opportunities: The Polyphony Lit Cover Art Contest: High school students from around the world are encouraged to submit visual art for the cover of their annual literary magazine. The Claudia Ann Seaman Awards for Young Writers: Annual awards to high school students in poetry, short fiction, and creative nonfiction. Each year, a distinguished panel of professional published authors choose one winner and two honorable mentions in each genre. The winners are awarded a $200 cash prize. Students from around the world are encouraged to submit.

★ Rider University Annual High School Writing Contest

Accepts essays, fiction and poetry. All finalists will receive a Certificate of Honorable Mention. All winners will be considered for publication in Venture, Rider’s literary magazine.

★ Write the World Competitions

We’re a community of young writers (ages 13 to 18), hailing from over 120 countries. Join our global platform, and explore our ever-changing library of prompts as you establish a regular writing practice and expand your repertoire of styles, all while building your portfolio of polished work. Enter competitions for the chance to receive feedback from authors, writing teachers, and other experts in the field.

Academic Research

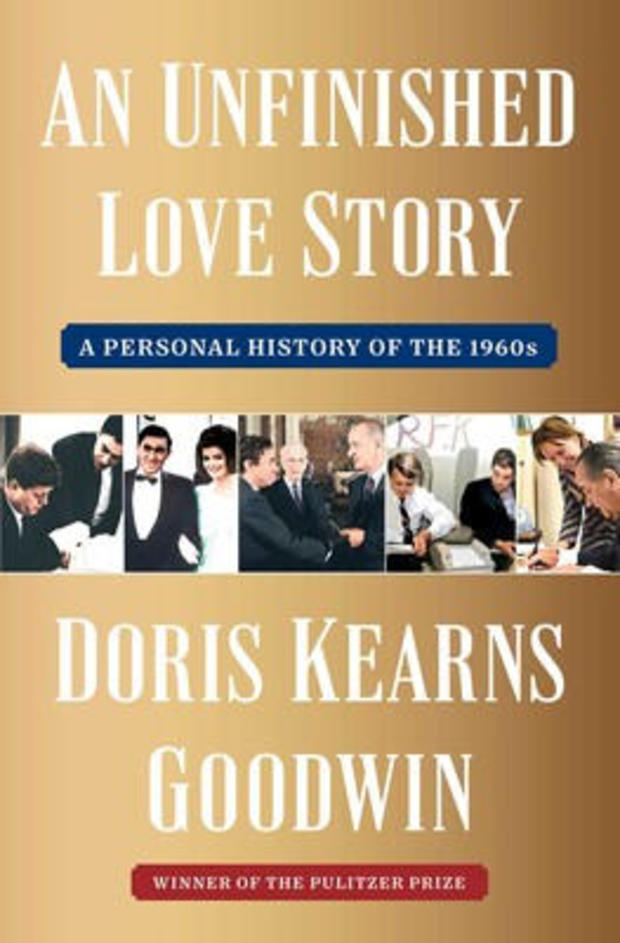

★ The Concord Review

The Concord Review, Inc., was founded in March 1987 to recognize and to publish exemplary history essays by high school students in the English-speaking world. With the Fall Issue (#118), 1,196 research papers (average 7,500 words, with endnotes and bibliography) have been published from authors in 45 states and 40 other countries. The Concord Review remains the only quarterly journal in the world to publish the academic history papers of secondary students.

★ The Curieux Academic Journal

The Curieux Academic Journal is an academic journal written entirely by high school students.

★ National History Day

Each year more than half a million students participate in the National History Day Contest. Students choose a historical topic related to the annual theme, and then conduct primary and secondary research. You will look through libraries, archives and museums, conduct oral history interviews, and visit historic sites. After you have analyzed and interpreted your sources, and have drawn a conclusion about the significance of your topic, you will then be able to present your work in one of five ways: as a paper, an exhibit, a performance, a documentary, or a website.

★ The Scribe Review

A quarterly online journal dedicated to publishing the academic English essays of high school students.

★ The Milking Cat

The Milking Cat is dedicated to providing weekly comedic pieces from a variety of aspiring high school comics. With pieces ranging from comics and movies to stories and satires, The Milking Cat is the place to be for young comedians.

Current Events and Culture

INKspire is a place for youth to share their stories and offer perspectives on relevant, contemporary issues. Young people can learn from one another, share their stories, thoughts and ideas while connecting with other youth around the world.

Please see the description at the top of this list.

★ Teen Opinions

Teenopinions.org is a platform for teens and tweens worldwide to share their opinions, ideas, reflections and perspectives with the world. Our mission is to give every teen and tween an opportunity to freely publish their perspectives in a non-competitive environment.

★ Young Post

Young Post is a teen print news and English-teaching product that is part of the South China Morning Post. While we are a Hong Kong product, we do welcome students from around the world in our pages and on our site. We have a Junior Reporters club , in which students learn reporting skills, and pitch and contribute stories. We have local members who have moved overseas for senior school or university who still contribute, but it would be wonderful to hear from more students interested in sharing stories that matter to them with their Asian peers.

★ Youth Voices Live

We are a site for conversations. We invite youth of all ages to voice their thoughts about their passions, to explain things they understand well, to wonder about things they have just begun to understand, and to share discussion posts with other young people using as many different genres and media as they can imagine!

★ American Foreign Service Association National High School Essay Contest

Why Diplomacy and Peacebuilding Matter: In a 1,000- to 1,250-word essay, identify two cases — one you deem successful and one you deem unsuccessful — where the U.S. pursued an integrated approach to build peace in a conflict-affected country.

★ The American Prospect 2020 Essay Contest

High school juniors and seniors may write 1,000 to 1,600 words on one of these two books: “ Saving Capitalism: For the Many, Not the Few ” by Robert B. Reich or “ The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration ” by Isabel Wilkerson High school freshmen and sophomores may write up to 1,200 words on one of these two books: “ Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City ” by Matthew Desmond or “ Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America ” by Barbara Ehrenreich

★ Goi Peace Foundation International Essay Contest for Young People

Guidelines for the 2019 International Essay Contest for Young People will be announced at the end of January 2019.

★ Profile in Courage Essay Contest

Describe and analyze an act of political courage by a US elected official who served during or after 1917.

★ Represent Magazine

A publication by and for youth in foster care, the stories in Represent give inspiration and information, while offering staff insight into those teenagers’ struggles.

★ We the Students Essay Contest

What are the essential qualities of a citizen in your community in 21st-century America? We encourage you to bring emotion, creativity, specific examples (including current events), and well-researched facts into what you write. A good essay will demonstrate how citizenship is not an abstract idea, but is, in fact, action inspired by constitutional principles. We can’t wait to see what citizenship looks like in your community!

★ NaNoWriMo Young Writer’s Program

National Novel Writing Month is a fun, empowering approach to creative writing. The challenge: draft an entire novel in just one month. For 30 wild, exciting, surprising days, you get to lock away your inner editor, let your imagination take over, and just create! Our Young Writers Program supports under-18 writers and K-12 educators as they participate in our flagship event each November, and take part in smaller writing challenges year-round. Summer Writing: Stay cool and creative all summer long by participating in Camp NaNoWriMo’s July session—either online here or over at Camp NaNoWriMo , or offline by using our writer-friendly, print-out-able Summer Writing Program resources. Choose a project you care about, set an ambitious goal, get feedback on your progress, and receive support from an international community of fellow writers.

★ One Teen Story

An award-winning quarterly literary magazine that features the work of today’s best teen writers (ages 13-19).

★ Ringling College Storytellers of Tomorrow Creative Writing Contest

We’re inviting all high-school age students to submit unpublished, original English-language stories of up to 2,000 words in length for the 4th Annual “Storytellers of Tomorrow” Contest. The criteria for earning prizes in this contest is simply overall quality, meaning that well-edited, engaging, and evocative stories have the best chance of winning over the judges.

★ Columbia Scholastic Press Association Gold Circle Awards

These awards are offered to recognize superior work by student journalists usually as individuals but sometimes as an entire staff working with either print or online media.

★ National Scholastic Press Association Individual Awards

Each year, the National Scholastic Press Association presents the Individual Awards, honoring the best individuals in scholastic journalism. There are six categories. Entries are judged by teams of professionals with experience and expertise in the area of each particular contest. The contests are open to any student on staff of an N.S.P.A. member publication.

★ Quill & Scroll Awards

We encourage, support and recognize individual student initiative and achievement in scholastic journalism, regardless the medium.

★ Dear Poet Project

A multimedia education project that invited young people in grades 5 through 12 to write letters in response to poems written and read by some of the award-winning poets who serve on the Academy of American Poets Board of Chancellors.

★ New York Times Opinion Section Letter to the Editor Contest

A letter-writing competition for high school students that runs from March 31, 2019 to April 8, 2019. We invite you to submit a letter to the editor in response to a Times news article, editorial, column or Op-Ed in the last few days. We will publish a selection of our favorites.

★ YCteen Writing Contest

YCteen is written by a staff of teen writers who work in our New York City newsroom. But writing is a form of conversation, and we want you to join in. We invite you to submit letter to the writer, responding to their story. This is an opportunity to express your opinion or present your own point of view on a story you’ve read.

Playwriting

★ Princeton University Ten-Minute Play Contest

Eligibility for this annual playwriting contest is limited to students in the 11th grade in the U.S. (or international equivalent of the 11th grade).

★ VSA Playwright Discovery Program Competition

Young writers with disabilities and collaborative groups that include students with disabilities, in the U.S. grades 6-12 (or equivalents) or ages 11-18 for non-U.S. students, are invited to explore the disability experience through the art of writing for performance — in the form of plays, screenplays, or music theater. Writers are encouraged to craft short (10 minute) works from their own experiences and observations in the style of realism, through the creation of fictional characters and settings, or writing metaphorically or abstractly about the disability experience.

★ Writopia Lab’s 10th AnnualWorldwide Plays Festival

An annual Off-Broadway festival of one-act plays written by playwrights ages 6 to 18 and produced, designed, directed, and acted by New York theater professionals.

★ Young Playwrights Festival

The Young Playwrights Festival takes place each spring at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center. If your play is selected for the festival, you will work with a creative team composed of National Theater Institute alumni — a director, dramaturg, designer, and actors to develop and stage your script.

★ Youth Plays New Voices One-Act Competition

We welcome submissions of challenging, entertaining plays and musicals that are appropriate for teen and younger actors and/or audiences.

★ Nancy Thorp Poetry Contest

Sponsored by Hollins University, the Nancy Thorp Poetry Contest provides scholarships, prizes, and recognition for the best poems submitted by high-school-aged women.

★ The Patricia Grodd Poetry Prize for Young Writers

Recognizes outstanding young poets and is open to high school sophomores and juniors throughout the world. The contest winner receives a full scholarship to the Kenyon Review Young Writers workshop.

★ Poetry Matters Project Lit Prize

Whether you are a published poet, have never written a poem, or have the writing of a poem on your bucket list, the Poetry Matters Project invites you to take the “ Poetry Month Challenge” where participants challenge their friends, and family to write a poem of no more than 30 lines in 30 days. Entries can be posted at You can send your entry as an audio recording, document file, mp3, or video file.

★ Princeton University High School Poetry Prize

The Leonard L. Milberg ’53 High School Poetry Prize recognizes outstanding work by student writers in the 11th grade in the U.S. or abroad.

Science Writing

★ curiousSCIENCEwriters

An innovative, extracurricular program that trains creative high school communicators to bring complex science to the general public through the power of story. Science and technology are advancing exponentially, yet fewer than 7 percent of American adults are scientifically literate. With growing medical, environmental and social issues facing us all, it is essential that the next generation of communicators be prepared to help people make sense of emerging science that affects their personal health and well-being, as well as that of the world around them.

★ EarthPlex

EarthPlex is the climate platform for teens founded by a fourteen-year-old. Any teenager can submit a post about climate change or read quality content about the environment, ways we can protect it, the impact of corporations, and more. Our mission is to give those under eighteen a voice in the battle against climate change.

★ EngineerGirl Writing Contest

Every year, the EngineerGirl website sponsors a contest dealing with engineering and its impact on our world. The topic and detailed instructions for the contest are posted in the fall with a deadline for submissions early the following year. Winners are announced in the spring.

THINK is an annual science research and innovation competition for high school students. Rather than requiring students to have completed a research project before applying, THINK instead caters to students who have done extensive research on the background of a potential research project and are looking for additional guidance in the early stages of their project. The program is organized by a group of undergraduates at MIT.

Places to Submit Teenage Visual Arts

★ Congressional Art Competition

Each spring, the Congressional Institute sponsors a nationwide high school visual art competition to recognize and encourage artistic talent in the nation and in each congressional district. Since the Artistic Discovery competition began in 1982, more than 650,000 high school students have participated. Students submit entries to their representative’s office, and panels of district artists select the winning entries. Winners are recognized both in their district and at an annual awards ceremony in Washington. The winning works are displayed for one year at the U.S. Capitol.

★ Doodle 4 Google

Calling all K-12 students — bring your creativity to life in a Doodle of the Google logo, using any medium you choose for the chance to be a Doodle 4 Google winner. The National Winner’s artwork will be featured on the Google home page.

★ The Gutenberg Award

The Gutenberg Award recognizes exceptional achievement in the field of graphic arts. Awards are available for printed items, websites, and photographs. Entries may be submitted by graphic arts students at any educational level including those in university, college, community-college, postsecondary technical school, high school vocational, high school technology education, and junior high/middle school technology education programs. There are three different Gutenberg competitions: print, website, and photography.

★ N.S.H.S.S. Visual Arts Competition

High school students may submit visual art and photography, painting, drawing, ceramics, glass, sculpture, mixed media, printmaking, weaving, digital and 35mm photography.

Film, Video and GIFs

★ All American High School Film Festival

The All American High School Film Festival is the largest student film festival in the world. Our festival offers an unparalleled experience designed specifically to promote and empower the future of film. Each October, thousands of student filmmakers join us in New York City for an action-packed weekend of resources and entertainment, including our Teen Indie Awards Show, where we hand out over $400,000 in prizes and scholarships.

★ American Youth Film Festival

The American Youth Film Festival is an opportunity for the youth to showcase their movie making skills. Categories include animation; comedy; commercials; documentary; feature; music video; public service announcements; science fiction; and short.

★ Boulder International Film Festival

The Boulder International Film Festival is currently accepting entries of short films made by teenagers (ages 12-18) for the Boulder International Film Festival Youth Pavilion. Winners must be present at Teen Opening Night the evening of March 1.

★ Breakthrough Junior Challenge

Make a three-minute video explaining a big idea in physics, life sciences, mathematics or the science of the Covid-19 pandemic.

★ CineYouth Festival

Cinema/Chicago’s CineYouth Film Festival is designed to encourage youth filmmakers in their creative endeavors. CineYouth provides opportunities for young filmmakers to articulate themselves artistically, and have their voice heard. Held annually in Chicago, CineYouth is a three-day festival celebrating and fostering the creativity of filmmakers 22 years old and younger by screening officially selected work and encouraging their creative endeavors by presenting a filmmaking workshop, discussions and panels.

★ GIF IT UP

GIF IT UP is an annual international gif-making campaign that encourages people to create new, fun, and unique gif artworks from digitized cultural heritage materials. Entrants are invited to search, discover, adapt, and reuse public domain and openly licensed video clips, images, art, documents, or other materials found in D.P.L.A . or international partner libraries Europeana, Trove, and DigitalNZ.

★ Heartland High School Film Competition

The High School Film Competition encourages tomorrow’s filmmakers to create films that inspire filmmakers and audiences through the transformative power of the art form. Students may submit short films under 15 minutes in length that are documentary or narrative; live-action or animated.

★ Live Más Scholarship

The Live Más Scholarship is not based on your grades or how well you play sports. No essays, no test scores, no right or wrong answers. We’re looking for the next generation of innovators, creators and dreamers who want to make a difference in the world.Submit a video (2 minutes or less in length) that tells us the story of your life’s passion. It could be a short film, animation or just a simple testimonial. This is not about how well you can make a film – we just want you to show us your passion and explain why you should be considered for a Live Más Scholarship.

★ Nashville Film Festival

An international competition for narrative, nonfiction and animated films under 40 minutes in length created by filmmakers aged 18 and under.

★ Newport Beach Film Festival

Celebrates the cinematic works, visions, and perspectives of young people from around the world. Through the exhibition of youth-created media, the festival seeks to create a forum for young filmmakers and encourage freedom of expression through cinema. The free event features a screening of short films created by filmmakers 18 years and younger.

★ Seattle International Film Festival

Filmmakers who are age 18 and under can send work to FutureWave Shorts.

★ World of 7 Billion Student Video Contest

Create a short video – up to 60 seconds – about human population growth that highlights one of the following global challenges: Preserving Biodiversity, Sustainable Resource Use, Protecting Human Rights.

Photography

★ High School Physics Photo Contest

The A.A.P.T. High School Physics Photo Contest is an international competition for high school students. For many years this contest has provided teachers and students an opportunity to learn about the physics behind natural and contrived situations by creating visual and written illustrations of various physical concepts. Students compete in an international arena with more than 1,000 of their peers for recognition and prizes.

★ Natural History Museum Wildlife Photographer of the Year

Wildlife Photographer of the Year uses photography to challenge perceptions about the natural world, helping to promote sustainability and the conservation of wildlife. We celebrate biodiversity, evolution and the origins of life, and aim to inspire a greater understanding of nature. We champion ethical wildlife photography. This means we advocate faithful representations of the natural world that are free from excessive digital manipulation, accompanied by honest captions and that display total respect for animals and their environments.

★ Rocky Mountain School of Photography High School Photo Contest

Rocky Mountain School of Photography trains students of all ages to become passionate image-makers through practical, hands-on learning environments for all skill levels. The R.M.S.P. High School Photo Contest is an annual opportunity for students aged 14-18 to submit their best images for the chance to win a new camera and other prizes. The contest opens Dec. 1 and closes Feb. 28.

★ SONY World Photography Awards Youth Competition

We are looking for the next generation of talented photographers! The Youth competition, for everyone aged 12-19, recognizes that a love for photography often starts at a young age. The competition helps young photographers grow and flourish into the next stages of their careers. Judges are looking for good composition, creativity and clear photography. The 2019 theme is “Diversity”: In one single image show the judges an example of diversity. To be understood in its widest sense, the image of diversity could concern people, culture or environment and could be of a local or global concern. All techniques and styles are welcomed, and judges will particularly reward creativity.

Do you have an opportunity to add? Let us know by posting a comment or writing to us at [email protected].

How to Write a History Essay with Outline, Tips, Examples and More

Before we get into how to write a history essay, let's first understand what makes one good. Different people might have different ideas, but there are some basic rules that can help you do well in your studies. In this guide, we won't get into any fancy theories. Instead, we'll give you straightforward tips to help you with historical writing. So, if you're ready to sharpen your writing skills, let our history essay writing service explore how to craft an exceptional paper.

What is a History Essay?

A history essay is an academic assignment where we explore and analyze historical events from the past. We dig into historical stories, figures, and ideas to understand their importance and how they've shaped our world today. History essay writing involves researching, thinking critically, and presenting arguments based on evidence.

Moreover, history papers foster the development of writing proficiency and the ability to communicate complex ideas effectively. They also encourage students to engage with primary and secondary sources, enhancing their research skills and deepening their understanding of historical methodology.

History Essay Outline

.png)

The outline is there to guide you in organizing your thoughts and arguments in your essay about history. With a clear outline, you can explore and explain historical events better. Here's how to make one:

Introduction

- Hook: Start with an attention-grabbing opening sentence or anecdote related to your topic.

- Background Information: Provide context on the historical period, event, or theme you'll be discussing.

- Thesis Statement: Present your main argument or viewpoint, outlining the scope and purpose of your history essay.

Body paragraph 1: Introduction to the Historical Context

- Provide background information on the historical context of your topic.

- Highlight key events, figures, or developments leading up to the main focus of your history essay.

Body paragraphs 2-4 (or more): Main Arguments and Supporting Evidence

- Each paragraph should focus on a specific argument or aspect of your thesis.

- Present evidence from primary and secondary sources to support each argument.

- Analyze the significance of the evidence and its relevance to your history paper thesis.

Counterarguments (optional)

- Address potential counterarguments or alternative perspectives on your topic.

- Refute opposing viewpoints with evidence and logical reasoning.

- Summary of Main Points: Recap the main arguments presented in the body paragraphs.

- Restate Thesis: Reinforce your thesis statement, emphasizing its significance in light of the evidence presented.

- Reflection: Reflect on the broader implications of your arguments for understanding history.

- Closing Thought: End your history paper with a thought-provoking statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

References/bibliography

- List all sources used in your research, formatted according to the citation style required by your instructor (e.g., MLA, APA, Chicago).

- Include both primary and secondary sources, arranged alphabetically by the author's last name.

Notes (if applicable)

- Include footnotes or endnotes to provide additional explanations, citations, or commentary on specific points within your history essay.

History Essay Format

Adhering to a specific format is crucial for clarity, coherence, and academic integrity. Here are the key components of a typical history essay format:

Font and Size

- Use a legible font such as Times New Roman, Arial, or Calibri.

- The recommended font size is usually 12 points. However, check your instructor's guidelines, as they may specify a different size.

- Set 1-inch margins on all sides of the page.

- Double-space the entire essay, including the title, headings, body paragraphs, and references.

- Avoid extra spacing between paragraphs unless specified otherwise.

- Align text to the left margin; avoid justifying the text or using a centered alignment.

Title Page (if required):

- If your instructor requires a title page, include the essay title, your name, the course title, the instructor's name, and the date.

- Center-align this information vertically and horizontally on the page.

- Include a header on each page (excluding the title page if applicable) with your last name and the page number, flush right.

- Some instructors may require a shortened title in the header, usually in all capital letters.

- Center-align the essay title at the top of the first page (if a title page is not required).

- Use standard capitalization (capitalize the first letter of each major word).

- Avoid underlining, italicizing, or bolding the title unless necessary for emphasis.

Paragraph Indentation:

- Indent the first line of each paragraph by 0.5 inches or use the tab key.

- Do not insert extra spaces between paragraphs unless instructed otherwise.

Citations and References:

- Follow the citation style specified by your instructor (e.g., MLA, APA, Chicago).

- Include in-text citations whenever you use information or ideas from external sources.

- Provide a bibliography or list of references at the end of your history essay, formatted according to the citation style guidelines.

- Typically, history essays range from 1000 to 2500 words, but this can vary depending on the assignment.

How to Write a History Essay?

Historical writing can be an exciting journey through time, but it requires careful planning and organization. In this section, we'll break down the process into simple steps to help you craft a compelling and well-structured history paper.

Analyze the Question

Before diving headfirst into writing, take a moment to dissect the essay question. Read it carefully, and then read it again. You want to get to the core of what it's asking. Look out for keywords that indicate what aspects of the topic you need to focus on. If you're unsure about anything, don't hesitate to ask your instructor for clarification. Remember, understanding how to start a history essay is half the battle won!

Now, let's break this step down:

- Read the question carefully and identify keywords or phrases.

- Consider what the question is asking you to do – are you being asked to analyze, compare, contrast, or evaluate?

- Pay attention to any specific instructions or requirements provided in the question.

- Take note of the time period or historical events mentioned in the question – this will give you a clue about the scope of your history essay.

Develop a Strategy

With a clear understanding of the essay question, it's time to map out your approach. Here's how to develop your historical writing strategy: