Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.5 The Purposes of Punishment

Learning objective.

- Ascertain the effects of specific and general deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, retribution, and restitution.

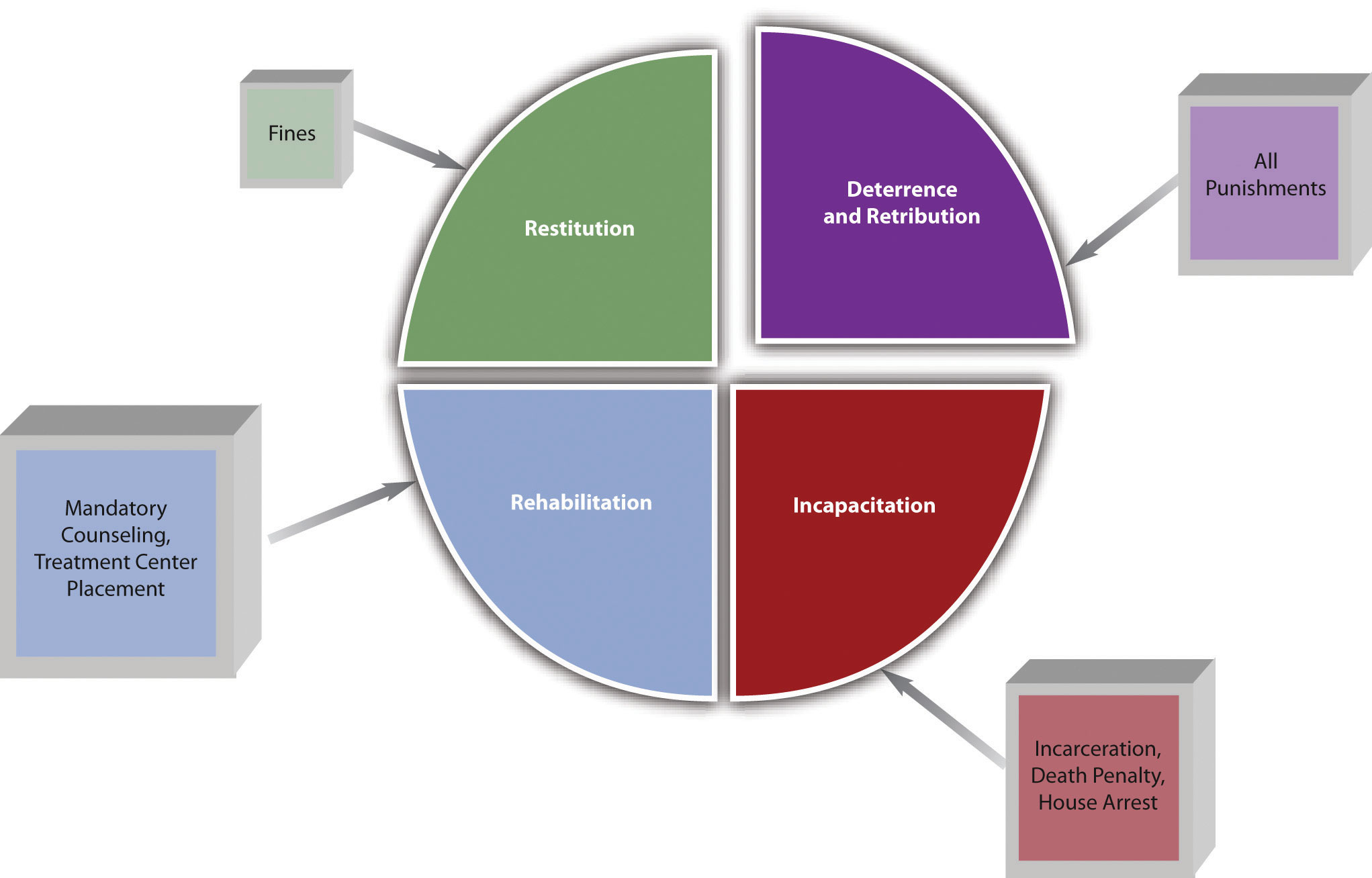

Punishment has five recognized purposes: deterrence , incapacitation , rehabilitation , retribution , and restitution .

Specific and General Deterrence

Deterrence prevents future crime by frightening the defendant or the public . The two types of deterrence are specific and general deterrence . Specific deterrence applies to an individual defendant . When the government punishes an individual defendant, he or she is theoretically less likely to commit another crime because of fear of another similar or worse punishment. General deterrence applies to the public at large. When the public learns of an individual defendant’s punishment, the public is theoretically less likely to commit a crime because of fear of the punishment the defendant experienced. When the public learns, for example, that an individual defendant was severely punished by a sentence of life in prison or the death penalty, this knowledge can inspire a deep fear of criminal prosecution.

Incapacitation

Incapacitation prevents future crime by removing the defendant from society. Examples of incapacitation are incarceration, house arrest, or execution pursuant to the death penalty.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation prevents future crime by altering a defendant’s behavior. Examples of rehabilitation include educational and vocational programs, treatment center placement, and counseling. The court can combine rehabilitation with incarceration or with probation or parole. In some states, for example, nonviolent drug offenders must participate in rehabilitation in combination with probation, rather than submitting to incarceration (Ariz. Rev. Stat., 2010). This lightens the load of jails and prisons while lowering recidivism , which means reoffending.

Retribution

Retribution prevents future crime by removing the desire for personal avengement (in the form of assault, battery, and criminal homicide, for example) against the defendant. When victims or society discover that the defendant has been adequately punished for a crime, they achieve a certain satisfaction that our criminal procedure is working effectively, which enhances faith in law enforcement and our government.

Restitution

Restitution prevents future crime by punishing the defendant financially . Restitution is when the court orders the criminal defendant to pay the victim for any harm and resembles a civil litigation damages award. Restitution can be for physical injuries, loss of property or money, and rarely, emotional distress. It can also be a fine that covers some of the costs of the criminal prosecution and punishment.

Figure 1.4 Different Punishments and Their Purpose

Key Takeaways

- Specific deterrence prevents crime by frightening an individual defendant with punishment. General deterrence prevents crime by frightening the public with the punishment of an individual defendant.

- Incapacitation prevents crime by removing a defendant from society.

- Rehabilitation prevents crime by altering a defendant’s behavior.

- Retribution prevents crime by giving victims or society a feeling of avengement.

- Restitution prevents crime by punishing the defendant financially.

Answer the following questions. Check your answers using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

- What is one difference between criminal victims’ restitution and civil damages?

- Read Campbell v. State , 5 S.W.3d 693 (1999). Why did the defendant in this case claim that the restitution award was too high? Did the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals agree with the defendant’s claim? The case is available at this link: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=11316909200521760089&hl=en&as_sdt=2&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr .

Ariz. Rev. Stat. §13-901.01, accessed February 15, 2010, http://law.justia.com/arizona/codes/title13/00901-01.html .

Criminal Law Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Legal Punishment

The question of whether, and how, legal punishment can be justified has long been a central concern of legal, moral, and political philosophy: what could justify a state in using the apparatus of the law to inflict intentionally burdensome treatment on its citizens? Radically different answers to this question are offered by consequentialist and by retributivist theorists — and by those who seek to incorporate consequentialist and retributivist considerations in ‘mixed’ theories of punishment. Meanwhile, abolitionist theorists argue that we should aim to replace legal punishment rather than to justify it. Among the significant developments in recent work on punishment theory are the characterisation of punishment as a communicative enterprise, greater recognition that punishment’s justification depends on the justification of the criminal law more generally, growing interest in the normative challenges raised by punishment in the international context, and increased concern for the relationship of punishment to the so-called ‘collateral’ consequences of a conviction.

1. Legal Punishment and Its Justification

2. punishment, crime, and the state, 3. consequentialist accounts, 4. retributivist accounts, 5. punishment as communication, 6. mixed accounts, 7. abolition and alternatives, 8. international criminal law and punishment, 9. collateral consequences, 10. further issues, other internet resources, related entries.

The central question asked by philosophers of punishment is: What can justify punishment? More precisely, since they do not usually talk much about punishment in such contexts as the family or the workplace (but see Zaibert 2006; Bennett 2008: Part II), their question is this: What can justify formal, legal punishment imposed by the state on those convicted of committing criminal offences? We will also focus on legal punishment here: not because the other species of punishment do not raise important normative questions (they do), nor because such questions can be answered in terms of an initial justification of legal punishment as being the paradigm case (since it’s not clear that they can be), but because legal punishment, apart from being more dramatically coercive and burdensome than other species of punishment usually are, raises distinctive issues about the role of the state and its relationship to its citizens, and about the role of the criminal law. Future references to ‘punishment’ should therefore be read, unless otherwise specified, as references to legal or criminal punishment.

What then are we to justify in justifying punishment? The search for a precise definition of punishment that exercised some philosophers (for discussion and references, see Scheid 1980; Boonin 2008: 3–28; Zimmerman 2011: ch. 1) is likely to prove futile; but we can say that legal punishment involves the imposition of something that is intended to be both burdensome and reprobative, on a supposed offender for a supposed crime, by a person or body who claims the authority to do so. Two points are worth particular notice here.

First, punishment involves material impositions or exactions that are in themselves typically unwelcome: they deprive people of things that they value (liberty, money, time); they require people to do things that they would not normally want to do or do voluntarily (to spend time on unpaid community labour, to report to a probation officer regularly, to undertake demanding programmes of various kinds). What distinguishes punishment from other kinds of coercive imposition, such as taxation, is that punishment is precisely intended to …: but to what? Some would say that punishment is intended to inflict pain or suffering: but that suggests that what matters is pain or suffering as such (and invites the familiar criticism that we and the state should not be in the business of trying to inflict pain or suffering on people; see Christie 1981 on ‘pain-delivery’), which some penal theorists would reject as a distortion. Others would say that punishment is intended to cause harm to the offender — adding, if they are careful (see Hanna 2014: s. 2) that what is intended is ‘prima facie harm’ rather than ‘all-things-considered harm’, to allow for the possibility that punishment might be, or might be intended to be, on balance beneficial to the offender. But some theorists would deny even this, since they would deny that punishment must be intended to be ‘intrinsically bad’ for the person punished. It is safer to say that punishment must be intended to be burdensome, and that is how punishment will be understood in what follows. (For running debate about this intentionality feature, see Wringe 2013, Hanna 2017, Wringe 2019, Hanna 2020.)

Second, it is widely accepted that what distinguishes punishment from mere ‘penalties’ (see Feinberg 1970) is their reprobative or condemnatory character. Penalties, such as parking tickets, might be imposed to deter the penalised conduct (or to recoup some of the costs that it causes) without being intended to express societal condemnation. But even if a primary purpose of punishment is deterrence (see ss. 3–4 below), its imposition (the conviction and formal sentence that the offender receives in court, the administration of the punishment itself) also expresses the censure or condemnation that the offender’s crime is taken to warrant.

These two features, that punishment is intentionally burdensome and condemnatory, make the practice especially normatively challenging. How can a practice that not only burdens those subjected to it but aims to burden them, and which conveys society’s condemnation, be justified?

We should not assume, however, that there is only one question of justification, which can receive just one answer. As Hart famously pointed out (Hart 1968: 1–27), we must distinguish at least three justificatory issues. First, what compelling reason is there to create and maintain a system of punishment: what good can it achieve, what duty can it fulfil, what moral demand can it satisfy? (Hart termed this the question of punishment’s ‘general justifying aim’, although the term may be misleading in that talk of ‘aims’ may seem to privilege a consequentialist answer to the question, whereas the compelling reason could be a nonconsequentialist one.) Second, who may properly be punished: what principles or aims should determine the allocations of punishments to individuals? Third, how should the appropriate amount of punishment be determined: how should sentencers go about deciding what sentence to impose? (One dimension of this third question concerns the amount or severity of punishment; another, which is insufficiently discussed by philosophers, concerns the concrete modes of punishment that should be available, in general or for particular crimes.) It might of course turn out that answers to all these questions will flow from a single theoretical foundation — for instance, from a unitary consequentialist principle specifying the good that punishment should achieve, or from some version of the retributivist principle that the sole proper aim of punishment is to impose on the guilty the punitive burdens they deserve. But matters might not be as simple as that: we might find that quite different and conflicting values are relevant to different issues about punishment, and that any complete normative account of punishment will have to find a place for these values and offer guidance in how to resolve tensions among them when they conflict (see s. 6).

Even this way of putting the matter oversimplifies it, by implying that we can hope to find a ‘complete normative account of punishment’: an account, that is, of how punishment can be justified. It is certainly an implicit assumption of much philosophical and legal discussion that punishment can, of course, be justified, and that the theorists’ task is to establish and explicate that justification. But it is an illegitimate assumption: normative theorists must be open to the possibility, startling and disturbing as it might be, that this pervasive human practice cannot be justified. Nor is this merely the kind of fantastical scepticism that moral philosophers are sometimes prone to imagine (‘suppose someone denied that killing for pleasure was wrong’): there is a significant strand of ‘abolitionist’ penal theorising (the subject of increasing philosophical attention in recent years) that argues precisely that legal punishment cannot be justified and should be abolished.

We will attend to some abolitionist arguments in section 7. Even if those arguments can be met, even if legal punishment can be justified, at least in principle, the abolitionist challenge is one that must be met, rather than ignored; and it will help to remind us of the ways in which any practice of legal punishment is bound to be morally problematic.

Legal punishment presupposes crime as that for which punishment is imposed, and a criminal law as that which defines crimes as crimes; a system of criminal law presupposes a state, which has the political authority to make and enforce the law and to impose punishments. A normative account of legal punishment and its justification must thus at least presuppose, and should perhaps make explicit, a normative account of the criminal law (why should we have a criminal law at all?) and of the proper powers and functions of the state (by what authority or right does the state make and declare law, and impose punishments on those who break it?). (See generally Duff 2018: ch. 1.)

Recent scholarship has thus seen a growing interest in grounding analysis of the justification of punishment in a political theory of the state. Many of these accounts are based on Rawls’s political theory or on other versions of constructivism (see Matravers 2000 and 2011b; Dolovich 2004; Brettschneider 2007; Flanders 2017; for critiques of such accounts, see Garvey 2004, Dagger 2011b). Several others are based on versions of republicanism (see Pettit 1997; Duff 2001; Dagger 2007 and 2011a; Yankah 2015; for other recent contributions showing the importance of political theory, see Brudner 2009; Brooks 2011; Sigler 2011; Markel 2012; Chiao 2016 and 2018). How far it matters, in this context, to make explicit a political theory of the state depends on how far different plausible political theories will generate different accounts of how punishment can be justified and should be used. We cannot pursue this question here (for two sharply contrasting views on it, see Philips 1986; M. Davis 1989), save to note one central point. For any political theory that takes seriously the idea of citizenship as full membership of the polity, the problem of punishment takes a particularly acute form, since we have now to ask how punishment can be consistent with citizenship (how citizens can legitimately punish each other): if we are not to say that those who commit crimes thereby forfeit their status as citizens (see s. 6 below), we must — if we are to justify punishment at all — show how the imposition of punishment can be consistent with, or even expressive of, the respect that citizens owe to each other. (Punishment is also, of course, imposed on non-citizens who commit crimes within a state’s territory: on the primacy of citizenship in understanding criminal law and its authority, and on the status of non-citizens, see Duff 2013 and 2018: ch. 3; Wringe 2021.)

Before we tackle such theories of punishment, however, we should look briefly at the concept of crime, since that is one focus of the abolitionist critique of punishment.

On a simple positivist view of law, crimes are kinds of conduct that are prohibited, on pain of threatened sanctions, by the law; and for positivists such as Bentham, who combine positivism with a normative consequentialism, the questions of whether we should maintain a criminal law at all, and of what kinds of conduct should be criminalised, are to be answered by trying to determine whether and when this method of controlling human conduct is likely to produce a net increase in good. Such a perspective seems inadequate, however: inadequate both to the claims of the criminal law, which presents its demands as something other or more than those of a gunman writ large — as something other or more than ‘Behave thus, or else!’ — and to the normative issues at stake when we ask what kinds of conduct should be criminalised. For the criminal law portrays crime not merely as conduct which has been prohibited, but as a species of wrongdoing: whether our inquiry is analytical (into the concept of crime) or normative (as to what kinds of conduct, if any, should be criminal), we must therefore focus on that notion of wrongdoing.

Crimes are, at least, socially proscribed wrongs — kinds of conduct that are condemned as wrong by some purportedly authoritative social norm. That is to say that they are wrongs which are not merely ‘private’ affairs, which properly concern only those directly involved in them: the community as a whole — in this case, the political community speaking through the law — claims the right to declare them to be wrongs. But crimes are ‘public’ wrongs in a sense that goes beyond this. Tort law, for instance, deals in part with wrongs that are non-private in that they are legally and socially declared as wrongs — with the wrong constituted by libel, for instance. But they are still treated as ‘private’ wrongs in the sense that it is up to the person who was wronged to seek legal redress. She must decide to bring, or not to bring, a civil case against the person who wronged her; and although she can appeal to the law to protect her rights, the case is still between her and the defendant. By contrast, a criminal case is between the whole political community — the state or the people — and the defendant: the wrong is ‘public’ in the sense that it is one for which the wrongdoer must answer not just to the individual victim, but to the whole polity through its criminal courts.

It is notoriously difficult to give a clear and plausible account of the distinction between civil and criminal law, between ‘private’ and ‘public’ legal wrongs, whether our interest is in the analytical question of what the distinction amounts to, or in the normative question of which kinds of wrong should fall into which category (see Murphy and Coleman 1984: ch. 3; a symposium in Boston University Law Review vol. 76 (1996): 1–373; Lamond 2007). It might be tempting to say that crimes are ‘public’ wrongs in the sense that they injure the whole community: they threaten social order, for instance, or cause ‘social volatility’ (Becker 1974); or they involve taking unfair advantage over those who obey the law (H. Morris 1968: 477–80; Murphy 1973; Dagger 1993 and 2008); or they undermine the trust on which social life depends (Dimock 1997). But such accounts distract our attention from the wrongs done to the individual victims that most crimes have, when it is those wrongs that should be our central concern: we should condemn the rapist or murderer, we should see the wrong he has done as our concern, because of what he has done to his victim. Another suggestion is that ‘public’ wrongs are those that flout the community’s essential or most basic values, in which all members of the community should see themselves as sharing: the wrong is done to ‘us’, not merely to its individual victim, in the sense that we identify ourselves with the victim as a fellow citizen (see Marshall and Duff 1998; Duff 2007: ch. 6; and see further section 6 of the entry on theories of criminal law ).

Some abolitionists, however, argue that we should seek to eliminate the concept of crime from our social vocabulary: we should talk and think not of ‘crimes’, but of ‘conflicts’ or ‘troubles’ (Christie 1977; Hulsman 1986). One motivation for this might be the thought that ‘crime’ entails punishment as the appropriate response: but that is not so, since we could imagine a system of criminal law without punishment. To define something as a ‘crime’ does indeed imply that some kind of public response is appropriate, since it is to define it as a kind of wrong that properly concerns the whole community; and it implies that that response should be a condemnatory one, since to identify wrongs as wrongs is to mark them out as apt for condemnation: but that public, condemnatory response could consist in nothing more than, for instance, some version of a criminal trial which calls the alleged wrongdoer to answer for her alleged wrongdoing, and condemns her for it, through a criminal conviction, if she is proved guilty. One can of course count a criminal conviction as a kind of punishment: but it does not entail the kind of materially burdensome punishment, imposed after conviction, with which penal theorists are primarily concerned.

Another possible motivation for the abolitionist objection to the concept of crime is a kind of moral relativism that objects to the ‘imposition’ of values on those who might not share them (Bianchi 1994: 71–97): but since abolitionists are very ready to tell us, insistently, how we ought to respond to conflicts or troubles, and how a state ought or ought not to treat its citizens, such an appeal to relativism reflects serious confusion (see Williams 1976: 34–39). More plausibly, the abolitionist claim could be that rather than take wrongdoing as our focus, we should focus on the harm that has been done, and on how it can be repaired; we will return to this suggestion in section 7 below.

Another abolitionist concern is that by defining and treating conduct as ‘criminal’, the law ‘steals’ the conflicts which crime involves from those to whom they properly belong (Christie 1977): instead of allowing, and helping, those who find themselves in conflict to resolve their trouble, the law takes the matter over and translates it into the professionalised context of the criminal justice system, in which neither ‘victim’ nor ‘offender’ is allowed any appropriate or productive role. Now it is a familiar and disturbing truth that our existing criminal processes — both in their structure and in their actual operations — tend to preclude any effective participation by either victims or offenders, although an adequate response to the criminal wrong that was done should surely involve them both. One response is to argue, as some abolitionists do, that our response to crime should consist not in punishment, but in a process of mediation or ‘restoration’ between victim and offender (see s. 7 below); but another is to insist that we should retain a distinctive criminal process of trials, and punishment, in which the polity as a whole, acting on behalf of the victim as well as on its own behalf, calls the criminal wrongdoer to account — but that victims and offenders should be given a more active role in that process (see further Duff et al 2007, esp. chs. 3–5, 7). Such an insistence on the need for a public criminal process reflects two aspects of the concept of crime: first, it is sometimes important to recognise that a situation involves not just people in ‘conflict’, but a victim who has been wronged and an offender who has done the wrong; second, some such wrongs are ‘public’ wrongs in the sense sketched above — wrongs that properly concern not just those directly affected, but all members of the political community. Faced, for instance, by feuding neighbours who persistently accuse each other of more or less trivial wrongs, it might indeed be appropriate to suggest that they should forget about condemning each other and look for a way of resolving their conflict. But faced by a rapist and the person he raped, or by a violent husband and the wife he has been beating up, it would a betrayal both of the victim and of the values to which we are supposedly committed to portray the situation merely as a ‘conflict’ which the parties should seek to resolve: whatever else or more we can do, we must recognise and declare that here is a victim who has been seriously wronged; and we must be collectively ready to censure the offender’s action as a wrong (for a useful discussion of the significance of criminal law in the context of domestic violence, see Dempsey 2009).

However, to argue that we should retain the concept of crime, that we should maintain a criminal law which defines and condemns a category of ‘public’ wrongs, is not yet to say that we should maintain a penal system that punishes those who commit such wrongs; while a system of criminal law might require something like a system of criminal trials that will authoritatively identify and condemn criminal wrongdoers, it does not of its nature require the imposition of further sanctions on such wrongdoers. So, we must turn now to the question of what could justify such a system of punishment.

Many people, including those who do not take a consequentialist view of other matters, think that any adequate justification of punishment must be basically consequentialist. For we have here a practice that inflicts, indeed seeks to inflict, significant hardship or burdens: how else could we hope to justify it than by showing that it brings consequential benefits sufficiently large to outweigh, and thus to justify, those burdens? We need not be Benthamite utilitarians to be moved by Bentham’s famous remark that “all punishment in itself is evil. ... [I]f it ought at all to be admitted, it ought only to be admitted in as far as it promises to exclude some greater evil” (Bentham 1789: ch. XIII.2). However, when we try to flesh out this simple consequentialist thought into something closer to a full normative account of punishment, problems begin to appear.

A consequentialist must justify punishment (if she is to justify it at all) as a cost-effective means to certain independently identifiable goods (for two simple examples of such theories, see Wilson 1983; Walker 1991). Whatever account she gives of the final good or goods at which all action ultimately aims, the most plausible immediate good that a system of punishment can bring is the reduction of crime. A rational consequentialist system of law will define as criminal only conduct that is in some way harmful; in reducing crime we will thus be reducing the harms that crime causes. It is commonly suggested that punishment can help to reduce crime by deterring, incapacitating, or reforming potential offenders (though for an argument that incapacitation is not a genuinely punitive aim, see Hoskins 2016: 260). (There are of course other goods that a system of punishment can bring. It can reassure those who fear crime that the state is taking steps to protect them—though this is a good that, in a well-informed society, will be achieved only insofar as the more immediate preventive goods are achieved. It can also bring satisfaction to those who want to see wrongdoers suffer — though to show that to be a genuine good, rather than merely a means of averting vigilantism and private revenge, we would need to show that it involves something more than mere vengeance, which would be to make sense of some version of retributivism.)

In consequentialist terms, punishment will be justified if it is an effective means of achieiving its aim, if its benefits outweigh its costs, and if there is no less burdensome means of achieving the same aim. It is a contingent question whether punishment can satisfy these conditions, and some objections to punishment rest on the empirical claim that it cannot — that there are more effective and less burdensome methods of crime reduction (see Wootton 1963; Menninger 1968; Golash 2005: chs. 2 and 8; Boonin 2008: 53, 264–67). Our focus here, however, will be on the moral objections to consequentialist accounts of punishment — objections, basically, that crime-reductive efficiency does not suffice to justify a system of punishment.

The most familiar line of objection to consequentialist penal theories contends that consequentialists would be committed to regarding manifestly unjust punishments (the punishment of those known to be innocent, for instance, or excessively harsh punishment of the guilty) to be in principle justified if they would efficiently serve the aim of crime reduction: but such punishments would be wrong, because they would be unjust (see e.g., McCloskey 1957: 468–69; Hart 1968, chs. 1–2; Ten 1987; Primoratz 1999, chs. 2–3; Boonin 2008: ch. 2).

There are some equally familiar consequentialist responses to this objection. One is to argue that such ‘unjust’punishments would be justified if they would really produce the best consequences (see e.g., Smart 1973: 69–72; Bagaric and Amarasekara 2000) — to which the critic will reply that we cannot thus put aside the moral significance of injustice. Another is to argue that in the real world it is extremely unlikely that such punishments would ever be for the best, and even less likely that the agents involved could be trusted reliably to pick out those rare cases in which they would be: thus we, and especially our penal officials, will do best if we think and act as if such punishments are intrinsically wrong and unjustifiable (see e.g., Rawls 1955; Hare 1981, chs. 3, 9.7) — to which the critic will respond that this still makes the wrongness of punishing a known innocent contingent on its effects, and fails to recognise the intrinsic wrong that such punishment does (see e.g., Duff 1986: 151–64; Primoratz 1999, chs. 3.3, 6.5). Another response is to argue that a richer or subtler account of the ends that the criminal law should serve will generate suitable protection against unjust punishments (see Braithwaite and Pettit 1990, especially 71–76, on ‘dominion’ as the end of criminal law); but the objection remains that any purely consequentialist account will make the protection of the innocent against injustice contingent on its instrumental contribution to the system’s aims (on Braithwaite and Pettit, see von Hirsch and Ashworth 1992; Duff 1996: 20–25; Pettit 1997).

Another objection to consequentialist accounts focuses not on potential wrongs done to the innocent but rather on the wrong allegedly done to the guilty. Consequentialist punishment, on this objection, fails to respect the person punished as an autonomous moral agent. In Kantian terms, such punishment treats those punished as mere means to achieving some social good, rather than respecting them as ends in themselves (Kant 1797: 473; Murphy 1973). The Kantian prohibition on treating each other ‘merely as means’ is admittedly unclear in its implications (for a useful discussion of how we should understand ‘the means principle’, see Tadros 2011: ch. 6). One might argue that if punishment is reserved for those who voluntarily break the law, it does not treat them merely as means. Indeed, Kant himself suggested that as long as we reserve punishment only for those found guilty of crimes, then it is permissible to punish with an eye toward potential benefits (Kant 1797: 473). As we have seen, though, insofar as such an approach relies on endorsing prohibitions on punishment of the innocent or disproportionate punishment of the guilty, the challenge remains that such constraints appear to be merely contingent if grounded in consequentialist considerations. Conversely, if the constraints are more than merely contingent, it appears that they will be based on some deontological considerations, in which case the overall theory will no longer be purely consequentialist, but rather a mixed theory (see s. 6).

A more recent objection (Duff 2011: 75–79) charges that consequentialist systems of punishment are inappropriately exclusionary insofar as they treat offenders as dangerous ‘outsiders’ who must be threatened, incapacitated, or reformed to ensure the safety of the law-abiding members of society. The criminal law, and the institution of punishment, in a liberal society should treat offenders as (still) members of the polity who despite having violated its values could, and should, nonetheless (re)commit to these values. A possible response is that a penal system aimed at crime reduction through deterrence need not be exclusionary, as it treats all community members equally, namely as potential offenders (Hoskins 2011a: 379–81). Also, insofar as such a system ‘promotes social cooperation under stable public institutions’, it thus helps to protect the freedom of everyone (Chiao 2018: 36).

Whereas consequentialist accounts regard punishment as justified instrumentally, as a means to achieving some valuable goal (typically crime reduction), retributivist accounts contend that punishment is justified as an intrinsically appropriate, because deserved, response to wrongdoing (but see Berman 2011 for an argument that some recent versions of retributivism actually turn it into a consequentialist theory).

Theorists have distinguished ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ forms of retributivism. Positive retributivism holds that an offender’s desert provides a reason in favour of punishment; essentially, the state should punish those found guilty of criminal offences to the extent that they deserve, because they deserve it. Penal desert constitutes not just a necessary, but an in-principle sufficient reason for punishment (only in principle, however, since there are good reasons — to do with the costs, both material and moral, of punishment — why we should not even try to punish all the guilty). Negative retributivism, by contrast, provides not a positive reason to punish, but rather a constraint on punishment: punishment should be imposed only on those who deserve it, and only in proportion with their desert. Because negative retributivism represents only a constraining principle, not a positive reason to punish, it has been employed in various mixed accounts of punishment, which endorse punishment for consequentialist reasons but only insofar as the punishment is no more than is deserved (see s. 6 below).

A striking feature of penal theorising during the last three decades of the twentieth century was a revival of positive retributivism — of the idea that the positive justification of punishment is to be found in its intrinsic character as a deserved response to crime (see H. Morris 1968; N. Morris 1974; Murphy 1973; von Hirsch 1976; two useful collections of contemporary papers on retributivism are White 2011 and Tonry 2012).

Positive retributivism comes in very different forms (Cottingham 1979). All can be understood, however, as attempting to answer the two central questions faced by any retributivist theory of punishment. First, what is the justificatory relationship between crime and punishment that the idea of desert is supposed to capture: why do the guilty ‘deserve to suffer’ (see L. Davis 1972) — and what do they deserve to suffer (see Ardal 1984; Honderich 2005, ch. 2)? Second, even if they deserve to suffer, or to be burdened in some distinctive way, why should it be for the state to inflict that suffering or that burden on them through a system of criminal punishment (Murphy 1985; Husak 1992 and 2015; Shafer-Landau 1996; Wellman 2009)?

One retributivist answer to these questions is that crime involves taking an unfair advantage over the law-abiding, and that punishment removes that unfair advantage. The criminal law benefits all citizens by protecting them from certain kinds of harm: but this benefit depends upon citizens accepting the burden of self-restraint involved in obeying the law. The criminal takes the benefit of the self-restraint of others but refuses to accept that burden herself: she has gained an unfair advantage, which punishment removes by imposing some additional burden on her (see H. Morris 1968; Murphy 1973; Sadurski 1985; Sher 1987, ch. 5; Adler 1992, chs. 5–8; Dagger 1993, 2008, 2011; Stichter 2010; Duus-Otterström 2017; for criticism, see Burgh 1982; Duff 1986, ch. 8; Falls 1987; Dolinko 1991; Anderson 1997; Boonin 2008: 119–143; Hoskins 2011b).

This kind of account does indeed answer the two questions noted above. What the criminal deserves to suffer is the loss of her unfair advantage, and she deserves that because it is unfair that she should get away with taking the benefits of the law without accepting the burdens on which those benefits depend; it is the state’s job to inflict this suffering on her, because it is the author or guarantor of the criminal law. However, such accounts have internal difficulties: for instance, how are we to determine how great was the unfair advantage gained by a crime; how far are such measurements of unfair advantage likely to correlate with our judgements of the seriousness of crimes? (For a detailed defence of the ‘unfair advantage’ theory as a theory of sentencing, see M. Davis 1992, 1996; for criticism, see Scheid 1990, 1995; von Hirsch 1990.) Furthermore, they seem to misrepresent what it is about crime that makes it deserving of punishment: what makes murder, or rape, or theft, or assault a criminal wrong, deserving of punishment, is surely the wrongful harm that it does to the individual victim — not (as on this kind of account) the supposed unfair advantage that the criminal takes over all those who obey the law (for recent attempts to defend fair play retributivism against these objections, see Stichter 2010 and Duus-Otterström 2017).

A different retributivist account appeals not to the abstract notion of unfair advantage, but to our (normal, appropriate) emotional responses to crime: for instance, to the resentment or ‘retributive hatred’, involving a desire to make the wrongdoer suffer, that crime may arouse (see Murphy and Hampton 1988, chs. 1, 3); or to the guilt, involving the judgement that I ought to be punished, that my own wrongdoing would arouse in me (see Moore 1997, ch. 4). Such accounts try to answer the first of the two questions noted above: crime deserves punishment in the sense that it makes appropriate certain emotions (resentment, guilt) which are satisfied by or expressed in punishment. They do not yet show, however, why it should be the state’s task to satisfy or provide formal expression for such emotions (but see Stephen 1873: 152); and their answers to the first question are also problematic. Criminal wrongdoing should, we can agree, provoke certain kinds of emotion, such as self-directed guilt and other-directed indignation; and such emotions might typically involve a desire to make those at whom they are directed suffer. But just as we can agree that anger is an appropriate response to wrongs done to me, while also arguing that we should resist the desire to hit back that anger often, even typically, involves (see Horder 1992:194–7), so we could argue that although guilt, resentment and indignation are appropriate responses to our own and others’ wrongdoing, we should resist the desire for suffering that they so often involve. At the least we need to know more than we are told by these accounts about just what wrongdoers deserve to suffer, and why the infliction of suffering should be an appropriate way to express such proper emotions. (For critical discussions of Murphy, see Murphy and Hampton 1988, ch. 2; Duff 1996: 29–31; Murphy 1999. On Moore, see Dolinko 1991: 555–9; Knowles 1993; Murphy 1999. See also Murphy 2003, 2012.)

More recently, critics of emotion-based retributivist accounts have contended that the emotions on which retributive (and other deontological) intuitions are based have evolved as mechanisms to stabilise cooperation; given that we have retributive emotions only because of their evolutionary fitness, it would be merely a coincidence if intuitions based on these emotions happened to track moral truths about, e.g., desert (see especially Greene 2008; also Singer 2005). A problem with such accounts is that they appear to prove too much: consequentialist accounts also rely on certain evaluation intuitions (about what has value, or about the proper way to respond to that which we value); insofar as such intuitions are naturally selected, then it would be no less coincidental if they tracked moral truths than if retributive intuitions did so. Thus the consequentialist accounts that derive from these intuitions would be similarly undermined by this evolutionary argument (see Kahane 2011; Mason 2011; but see Wiegman 2017).

A third version of retributivism holds that when people commit a crime, they thereby incur a moral debt to their victims, and punishment is deserved as a way to pay this debt (McDermott 2001). This moral debt differs from the material debt that an offender may incur, and thus payment of the material debt (returning stolen money or property, etc.) does not settle the moral debt: punishment is needed to pay the moral debt, by denying the ill-gotten moral good to the perpetrator. Among the challenges for this account are to explain the nature of the moral good, how the offender takes this moral good from the victim, how punishment denies this good to the offender, and how doing so thereby pays the offender’s debt to the victim.

Perhaps the most influential version of retributivism in recent decades seeks the meaning and justification of punishment as a deserved response to crime in its expressive or communicative character. (On the expressive dimension of punishment, see generally Feinberg 1970; Primoratz 1989; for critical discussion, see Hart 1963: 60–69; Skillen 1980; M. Davis 1996: 169–81; A. Lee 2019.) Consequentialists can of course portray punishment as useful partly in virtue of its expressive character (see Ewing 1927; Lacey 1988; Braithwaite and Pettit 1990); but a portrayal of punishment as a mode of deserved moral communication has been central to many recent versions of retributivism.

The central meaning and purpose of punishment, on such accounts, is to convey the censure or condemnation that offenders deserve for their crimes. On some versions of this type of theory, punishment serves to express to the community generally (including the offender and victim) the society’s denunciation of or dissociation from the crime (see Bennett 2008; Wringe 2016). On other such accounts, the primary intended audience of the condemnatory message is the offender himself, although the broader society may be a secondary audience (see Duff 2001: secs. 1.4.4, 3.2; Markel 2011).

Once we recognise that punishment can serve this communicative purpose, we can see how such accounts begin to answer the two questions that retributivists face. First, there is an obviously intelligible justificatory relationship between wrongdoing and condemnation: whatever puzzles there might be about other attempts to explain the idea of penal desert, the idea that it is appropriate to condemn wrongdoing is surely unpuzzling. Second, it is appropriate for the state to ensure that such censure is formally administered through the criminal justice system: if crimes are public wrongs, breaches of the political community’s authoritative code, then they merit public censure by the community. (For other examples of communicative accounts, see especially von Hirsch 1993: ch.2; Markel 2012. For critical discussion, see M. Davis 1991; Boonin 2008: 171–80; Hanna 2008; Matravers 2011a.)

Two crucial lines of objection face any such justification of punishment as a communicative enterprise. The first line of critique holds that, whether the primary intended audience is the offender or the community generally, condemnation of a crime can be communicated through a formal conviction in a criminal court; or it could be communicated by some further formal denunciation issued by a judge or some other representative of the legal community, or by a system of purely symbolic punishments which were burdensome only in virtue of their censorial meaning. It can, of course, also be communicated by ‘hard treatment’ punishments of the kinds imposed by our courts — by imprisonment, by compulsory community service, by fines and the like, which are burdensome independently of their censorial meaning (on ‘hard treatment’, see Feinberg 1970): but why should we choose such methods of communication, rather than methods that do not involve hard treatment (see Christie 1981: 98–105; Boonin 2008: 176–79; Hanna 2008; Königs 2013; Tadros 2011: 103)? Is it because they will make the communication more effective (see Falls 1987; Primoratz 1989; Kleinig 1991)? But one might think that an account that relies on punishment’s contingent effectiveness in communicating the desired message begins to look more like the sort of consequentialist account of which retributivists are critical (but see Glasgow 2015: 611–20). And anyway, one might worry that the hard treatment will conceal, rather than highlight, the moral censure it should communicate (see Mathiesen 1990: 58–73).

One sort of answer to this first line of critique explains penal hard treatment as an essential aspect of the enterprise of moral communication itself. Punishment, on this view, should aim not merely to communicate censure to the offender, but to persuade the offender to recognise and repent the wrong he has done, and so to recognise the need to reform himself and his future conduct, and to make apologetic reparation to those whom he wronged. His punishment then constitutes a kind of secular penance that he is required to undergo for his crime: its hard treatment aspects, the burden it imposes on him, should serve both to assist the process of repentance and reform, by focusing his attention on his crime and its implications, and as a way of making the apologetic reparation that he owes (see Duff 2001, 2011b; see also Garvey 1999, 2003; Tudor 2001; Brownless 2007; Hus 2015; for a sophisticated discussion see Tasioulas 2006). This type of account faces serious objections (see Bickenbach 1988; Ten 1990; von Hirsch 1999; Bagaric and Amarasekara 2000; Ciocchetti 2004; von Hirsch and Ashworth 2005: ch. 7; Bennett 2006, 2015): in particular that it cannot show penal hard treatment to be a necessary aspect of a communicative enterprise which is still to respect offenders as responsible and rational agents who must be left free to remain unpersuaded; that apologetic reparation must be voluntary if it is to be of any real value; and that a liberal state should not take this kind of intrusive interest in its citizens’ moral characters.

The second line of objection to communicative versions of retributivism — and indeed against retributivism generally — charges that the notions of desert and blame at the heart of retributivist accounts are misplaced and pernicious. One version of this objection is grounded in scepticism about free will. Free will scepticism holds that people’s behaviour is the product of determinism, luck, or chance, and thus that we are not morally responsible for our behaviour in the respects that would justify the ideas that those who commit crimes are blameworthy and deserve punishment (see Pereboom 2013; Caruso 2018). In response, retributivists may point out that only if punishment is grounded in desert can we provide more than contingent assurances against punishment of the innocent or disproportionate punishment of the guilty, or assurances against treating those punished as mere means to whatever desirable social ends (see s. 3 above; but see Vilhauer 2013).

Another version of the objection is not grounded in free will scepticism: it allows that people may sometimes merit a judgement of blameworthiness. But it contends that the ‘affective’ aspect of blame — its realisation in negative reactive attitudes such as anger, hatred, and contempt — has pernicious effects when manifested in the criminal law: such emotion-laden blame fosters all-encompassing condemnations of offenders, rather than condemnation merely of their crimes; and it has contributed to overcriminalisation, overly harsh sentencing, and mass incarceration. On this line of objection, the state’s response to crimes should focus not on retribution but on rehabilitation, treating offenders as morally responsible agents but not blaming them (see Lacey and Pickard 2013, 2015, 2018, 2021; for similar accounts, see Kelly 2018; Nussbaum 2016: ch. 6).

To this second version of the objection to retributivist blame, retributivists may respond that although emotions associated with retributive blame have no doubt contributed to various excesses in penal policy, this is not to say that the notion of deserved censure can have no appropriate place in a suitably reformed penal system. After all, when properly focused and proportionate, reactive attitudes such as anger may play an important role by focusing our attention on wrongdoing and motivating us to stand up to it; anger-tinged blame may also serve to convey how seriously we take the wrongdoing, and thus to demonstrate respect for its victims as well as its perpetrators (see Cogley 2014; Hoskins 2020). What’s more, on the sort of communicative retributivist account sketched above, treating offenders as responsible agents involves pointing out when they have done wrong and expecting them to take responsibility for their wrongful actions. If taking responsibility for one’s wrongdoing requires that one acknowledge it as wrongdoing, commit to reforming one’s behaviour, and begin to reconcile with one’s community by making reparation for the wrongdoing, then one might argue that emotions associated with self-blame (guilt, remorse) and others’ blame (anger, resentment) play a central role in such a process.

Given the challenges faced by pure consequentialist and pure retributivist accounts, some theorists have sought to make progress on the question of punishment’s justification by incorporating consequentialist and nonconsequentialist elements into their accounts.

Perhaps the most influential example of a mixed account begins by recognizing that the question of punishment’s justification is in fact several different questions, which may be answered by appeal to different considerations. In particular, Hart (1968: 9–10) pointed out that we may ask about punishment, as about any social institution, what compelling rationale there is to maintain the institution (that is, what values or aims it fosters) and also what considerations should govern the institution. The compelling rationale will itself entail certain constraints: e.g., the rationale of deterrence would rule out punishments that had no deterrent effect or, worse, tended to exacerbate crime levels. What distinguishes hybrid theories such as Hart’s, however, is the claim that there may be constraining considerations that do not flow from punishment’s rationale. On Hart’s account, the compelling rationale for punishment (what he termed its ‘general justifying aim’) lies in its beneficial effects, but our pursuit of that aim must be constrained by nonconsequentialist principles that preclude the kinds of injustice alleged to flow from a purely consequentialist account: principles that forbid, for instance, the deliberate punishment of the innocent, or the excessively harsh punishment of the guilty. (See most famously Hart 1968, and Scheid 1997 for a sophisticated Hartian theory; on Hart, see Lacey 1988: 46–56; Morison 1988; Primoratz 1999: ch. 6.6.)

Although analysis of ‘the hybrid theory’ of punishment has tended to focus on Hart’s version of it, one might endorse hybrid views that vary significantly from Hart’s. For example, whereas Hart endorsed a consequentialist rationale for punishment and nonconsequentialist side-constraints, one might instead endorse a retributivist rationale constrained by consequentialist considerations (punishment should not tend to exacerbate crime, or undermine offender reform, etc.), or constrained by nonconsequentialist (but not retributivist) considerations such as human rights or respect for persons. Alternatively, one might endorse an account on which both consequentialist and retributivist considerations features as rationales but for different branches of the law: on such an account, the legislature determines crimes and establishes sentencing ranges with the aim of crime reduction, but the judiciary makes sentencing decisions based on retributivist considerations of desert (M. C. Altman 2021; Rawls’s account (1955) has also been characterised as a hybrid view of this sort, but in fact it is a version of rule utilitarianism; on the variety of hybrid views, see Hoskins 2021).

Critics have charged that hybrid accounts are ad hoc or internally inconsistent (see Kaufman 2008: 45–49). In addition, retributivists argue that hybrid views that integrate consequentialist rationales with retributivist side-constraints thereby relegate retributivism to a merely subsidiary role, when in fact giving offenders their just deserts is a (or the) central rationale for punishment (see Wood 2002: 303).

Also, because hybrid accounts incorporate consequentialist and retributivist elements, they may be subject to some of the same objections raised against pure versions of consequentialism or retributivism. For example, insofar as they endorse retributivist constraints on punishment, they face the thorny problem of explaining the retributivist notion of desert (see s. 4 above): but it is not clear whether they can be justified without such an appeal to retributivist desert (see Hart 1968: 44–48; Feinberg 1988: 144–55; Walker 1991, ch. 11). Even if such side-constraints can be securely grounded, however, consequentialist theories of punishment face the broadly Kantian line of objection discussed earlier (s. 3), that punishing with the aim of serving some desirable social ends treats those punished merely as means to those further ends, which denies them the respect, the moral standing, that is their due as responsible agents.

Some have contended that punishment with a consequentialist rationale does not treat those punished merely as means as long as it is constrained by the retributivist prohibitions on punishment of the innocent and disproportionate punishment of the guilty (see Walker 1980: 80–85; Hoskins 2011a). Still, a critic may argue that if we are to treat another with the respect due to her as a rational and responsible agent, we must seek to modify her conduct only by offering her good and relevant reasons to modify it for herself. Punishment aimed at deterrence, incapacitation, or offender reform, however, does not satisfy that demand. A reformative system treats those subjected to it not as rational, self-determining agents, but as objects to be re-formed by whatever efficient (and humane) techniques we can find. An incapacitative system does not leave those subjected to it free, as responsible agents should be left free, to determine their own future conduct, but seeks to preempt their future choices by incapacitating them. And although a deterrent system does, unlike the others, offer potential offenders reason to obey the law, it offers them the wrong kind of reason: instead of addressing them as responsible moral agents, in terms of the moral reasons which justify the law’s demands on them, it addresses them as merely self-interested beings, in the coercive language of threat; deterrence treats ‘a man like a dog instead of with the freedom and respect due to him as a man’ (Hegel 1821: 246. For these objections, see Lewis 1953; H Morris 1968; Duff 1986: 178–86; von Hirsch 1993: 9–14; von Hirsch and Ashworth 1998, chs. 1, 3).

One strategy for dealing with them is to posit a two-step justification of punishment. The first step, which typically appeals to nonconsequentialist values, shows how the commission of a crime renders the offender eligible for, or liable to, the kinds of coercive treatment that punishment involves: such treatment, which is normally inconsistent with the respect due to us as rational agents or as citizens, and inconsistent with the Kantian means principle, is rendered permissible by the commission of the offence. The second step is then to offer positive consequentialist reasons for imposing punishment on those who are eligible for it or liable to it: we should punish if and because this can be expected to produce sufficient consequential benefits to outweigh its undoubted costs. (Further nonconsequentialist constraints might also be placed on the severity and modes of punishment that can be permitted: constraints either flowing from an account of just what offenders render themselves liable to, or from other values external to the system of punishment.)

Thus, for instance, some argue that those who voluntarily break the law thereby forfeit at least some of the rights that citizens can normally claim: their wrongdoing therefore legitimises kinds of treatment (reformative or incapacitative treatment, for instance, or deterrent punishment) that would normally be wrong as violating citizens’ rights (see Goldman 1982; C Morris 1991; Wellman 2012; for criticisms, see Lippke 2001a; Boonin 2008: 103–19). We must ask, however, whether we should be so quick to exclude fellow citizens from the rights and status of citizenship, or whether we should not look for an account of punishment (if it is to be justified at all) on which punishment can still be claimed to treat those punished as full citizens. (The common practice of denying imprisoned offenders the right to vote while they are in prison, and perhaps even after they leave prison, is symbolically significant in this context: those who would argue that punishment should be consistent with recognised citizenship should also oppose such practices; see Lippke 2001b; Journal of Applied Philosophy 2005; see also generally s. 9.)

Another view holds that punishment does not violate offenders’ rights insofar as they consent to their punishment (see Nino 1983). The consent view holds that when a person voluntarily commits a crime while knowing the consequences of doing so, she thereby consents to these consequences. This is not to say that she explicitly consents to being punished, but rather than by her voluntary action she tacitly consents to be subject to what she knows are the consequences. Notice that, like the forfeiture view, the consent view is agnostic regarding the positive aim of punishment: it purports to tell us only that punishing the person does not wrong her, as she has effectively waived her right against such treatment. The consent view faces formidable objections, however. First, it appears unable to ground prohibitions on excessively harsh sentences: if such sentences are implemented, then anyone who subsequently violates the corresponding laws will have apparently tacitly consented to the punishment (Alexander 1986). A second objection is that most offenders do not in fact consent, even tacitly, to their sentences, because they are unaware either that their acts are subject to punishment or of the severity of the punishment to which they may be liable. For someone to have consented to be subject to certain consequences of an act, she must know of these consequences (see Boonin 2008: 161–64). A third objection is that, because tacit consent can be overridden by explicit denial of consent, it appears that explicitly nonconsenting offenders could not be justifiably punished on this view (ibid.: 164–165; but see Imbrisevic 2010).

Others offer contractualist or contractarian justifications of punishment, grounded in an account not of what treatment offenders have in fact tacitly consented to, but rather of what rational agents or reasonable citizens would endorse. The punishment of those who commit crimes is then, it is argued, rendered permissible by the fact that the offender himself would, as a rational agent or reasonable citizen, have consented to a system of law that provided for such punishments (see e.g., Dolovich 2004; Brettschneider 2007; Finkelstein 2011; for criticism, see Dagger 2011; see also Matravers 2000). Still others portray punishment (in particular deterrent punishment) as a species of societal (self-) defence — and it seems clear that to defend oneself against a wrongful attack is not to use the attacker ‘merely as a means’, or to fail to show him the respect that is his due. (For versions of this kind of argument, see Alexander 1980; Quinn 1985; Farrell 1985, 1995; Montague 1995; Ellis 2003 and 2012. For criticism, see Boonin 2008: 192–207. For a particularly intricate development of this line of thought, grounding the justification of punishment in the duties that we incur by committing wrongs, see Tadros 2011; for critical responses, see the special issue of Law and Philosophy , 2013.)

One might argue that the Hegelian objection to a system of deterrent punishment overstates the tension between the types of reasons, moral or prudential, that such a system may offer. Punishment may communicate both a prudential and a moral message to members of the community. Even before a crime is committed, the threat of punishment communicates societal condemnation of an offense. This moral message may help to dissuade potential offenders, but those who are unpersuaded by this moral message may still be prudentially deterred by the prospect of punishment. Similarly, those who actually do commit crimes may be dissuaded from reoffending by the moral censure conveyed by their punishment, or else by the prudential desire to avoid another round of hard treatment. What’s more, even if punishment itself did provide solely prudential reasons not to commit crimes, the criminal legal system more generally may communicate with citizens in moral terms. Through its criminal statutes, a community declares certain acts to be wrong and makes a moral appeal to community members to comply, whereas trials and convictions can communicate a message of deserved censure to the offender. Thus even if a system of deterrent punishment is itself regarded as communicating solely in prudential terms, it seems that the criminal law more generally can still communicate a moral message to those subject to it (see Hoskins 2011a).

A somewhat different attempt to accommodate prudential as well as moral reasons in an account of punishment begins with the retributivist notion that punishment is justified as a form of deserved censure, but then contends that we should communicate censure through penal hard treatment because this will give those who are insufficiently impressed by the moral appeal of censure prudential reason to refrain from crime; because, that is, the prospect of such punishment might deter those who are not susceptible to moral persuasion. (See Lipkin 1988, Baker 1992. For a sophisticated revision of this idea, which makes deterrence firmly secondary to censure, see von Hirsch 1993, ch. 2; Narayan 1993. For critical discussion, see Bottoms 1998; Duff 2001, ch. 3.3. For another subtle version of this kind of account, see Matravers 2000.) This kind of account differs from the accounts just discussed, on which retributivist prohibitions on punishment of the innocent or excessive punishment of the guilty constrain the pursuit of consequentialist aims, since in the current account the (retributivist) imposition of deserved censure is part of the positive justifying aim of punishment; and it can claim, in response to the Hegelian objection to deterrence, that it does not address potential offenders merely ‘like dogs’, since the law’s initial appeal to the citizen is in the appropriate moral terms: the prudential, coercive reasons constituted by penal hard treatment as deterrence are relevant only to those who are deaf, or at least insufficiently attentive, to the law’s moral appeal. It might be objected that on this account the law, in speaking to those who are not persuaded by its moral appeal, is still abandoning the attempt at moral communication in favour of the language of threats, and thus ceasing to address its citizens as responsible moral agents: to which it might be replied, first, that the law is addressing us, appropriately, as fallible moral agents who know that we need the additional spur of prudential deterrence to persuade us to act as we should; and second, that we cannot clearly separate the (merely) deterrent from the morally communicative dimensions of punishment — that the dissuasive efficacy of legitimate punishment still depends crucially on the moral meaning that the hard treatment is understood to convey.

One more mixed view worth noting holds that punishment is justified as a means of teaching a moral lesson to those who commit crimes, and perhaps to community members more generally (the seminal articulations of this view are H. Morris 1981 and Hampton 1984; for a more recent account, see Demetriou 2012; for criticism, see Deigh 1984, Shafer-Landau 1991). Like standard consequentialist accounts, the moral education view acknowledges that punishment’s role in reducing crime is a central part of its rationale (see, e.g., Hampton 1984: 211). But education theorists also take seriously the Hegelian worry discussed earlier; they view punishment not as a means of conditioning people to behave in certain ways, but rather as a means of teaching them that what they have done should not be done because it is morally wrong. Thus although the education view sets offender reform as an end, it also implies certain nonconsequentialist constraints on how we may appropriately pursue this end. Another distinctive feature of the moral education view is that it conceives of punishment as aiming to confer a benefit on the offender: the benefit of moral education. Critics have objected to the moral education view on various grounds, however. Some are sceptical about whether punishment is the most effective means of moral education. Others deny that most offenders need moral education; many offenders realise what they are doing is wrong but are weak-willed, impulsive, etc. Also, may liberal theorists object that the education view is inappropriately paternalistic in that it endorses coercively restricting offenders’ liberties as a means to confer a benefit on them.

Each of the theories discussed in this section incorporates, in various ways, consequentialist and nonconsequentialist elements. Whether any of these is more plausible than pure consequentialist or pure retributivist alternatives is, not surprisingly, a matter of ongoing philosophical debate. One possibility, of course, is that none of the theories on offer is successful because punishment is, ultimately, unjustifiable. The next section considers penal abolitionism.

Abolitionist theorising about punishment takes many different forms, united only by the insistence that we should seek to abolish, rather than merely to reform, our practices of punishment. (Classic abolitionist texts include Christie 1977, 1981; Hulsman 1986, 1991; de Haan 1990; Bianchi 1994.) An initial question is precisely what practices should be abolished. Some abolitionists focus on particular modes of punishment, such as capital punishment (see, e.g., Brooks 2004; Yost 2019) or imprisonment (see, e.g., A. Y. Davis 2003). What’s more, a prominent strand of abolitionism focuses on incarceration as practiced in the U.S. context, with links drawn between imprisonment and the American legacy of slavery, Jim Crow, and segregation (see, e.g., Adelsberg et. al. 2015; McLeod 2019; Roberts 2019). Insofar as such critiques are grounded in concerns about racial disparities, mass incarceration, police abuses, and other features of the U.S. criminal justice system, they may have implications for other U.S. criminal justice practices in addition to incarceration. At the same time, insofar as the critiques are based on particular features of the U.S. system, it may be less clear what implications they have for imprisonment as it is implemented in other polities. By contrast, other abolitionist accounts focus not on some particular mode(s) of punishment, or on a particular mode of punishment as administered in this or that legal system, but rather on criminal punishment in any form (see, e.g., Golash 2005; Boonin 2008; Zimmerman 2011). It is important to be clear about the target of critique: to endorse the abolition of imprisonment, or even of criminal punishment in any form, as it is currently practiced allows for the possibility that a suitably reformed system of imprisonment or punishment in some other form could be justified (and here it may be difficult, as with Theseus’s ship, to distinguish between radically rebuilding an existing practice and abolishing it in favour of an alternative practice).

The more powerful abolitionist challenge is that punishment cannot be justified even in principle. After all, when the state imposes punishment, it treats some people in ways that would typically (outside the context of punishment) be impermissible. It subjects them to intentionally burdensome treatment and to the condemnation of the community. Abolitionists find that the various attempted justifications of this intentionally burdensome condemnatory treatment fail, and thus that the practice is morally wrong — not merely in practice but in principle. For such accounts, a central question is how the state should respond to the types of conduct for which one currently would be subject to punishment. In this section we attend to three notable types of abolitionist theory and the alternatives to punishment that they endorse.

Most prominently, many abolitionists look to ‘restorative justice’ as an alternative to punishment. (‘Restorative’ practices and programmes also play an increasingly significant, although still somewhat marginal, role within the criminal process of trial and punishment; but our concern here is with restorative justice as an alternative to punishment.) The restorative justice movement has been growing in strength: although there are different and conflicting conceptions of what ‘restorative justice’ means or involves, one central theme is that what crime makes necessary is a process of reparation or restoration between offender, victim, and other interested parties; and that this is achieved not through a criminal process of trial and punishment, but through mediation or reconciliation programmes that bring together the victim, offender and other interested parties to discuss what was done and how to deal with it (see generally Matthews 1988; Daly and Immarigeon 1998; von Hirsch and Ashworth 1998, ch. 7; Braithwaite 1999; Walgrave 2002; von Hirsch et al 2003; von Hirsch, Ashworth and Shearing 2005; London 2011; Johnstone 2011, 2012).

Advocates of restorative justice often contrast it with ‘retributive’ justice; they argue that we should look for restoration rather than retribution or punishment, and seek to repair harms caused rather than to inflict punitive suffering for wrongs done. But one might regard this as a false dichotomy (see Allais 2011; Duff 2011a). For when we ask what it is that requires ‘restoration’ or repair, the answer must refer not only to whatever material harm was caused by the crime, but to the wrong that was done: that was what fractured the relationship between offender and victim (and the broader community), and that is what must be recognised and ‘repaired’ or made up for if a genuine reconciliation is to be achieved. A restorative process that is to be appropriate to crime must therefore be one that seeks an adequate recognition, by the offender and by others, of the wrong done—a recognition that must for the offender, if genuine, be repentant; and that seeks an appropriate apologetic reparation for that wrong from the offender. But those are also the aims of punishment as a species of secular penance, as sketched above. A system of criminal punishment, however improved it might be, is of course not well designed to bring about the kind of personal reconciliations and transformations that advocates of restorative justice sometimes seek; but it could be apt to secure the kind of formal, ritualised reconciliation that is the most that a liberal state should try to secure between its citizens. If we focus only on imprisonment, which is still often the preferred mode of punishment in many penal systems, this suggestion will appear laughable; but if we think instead of punishments such as Community Service Orders (now part of what is called Community Payback) or probation, it might seem more plausible.

This argument does not, of course, support that account of punishment against its critics. What it might suggest, however, is that although we can learn much from the restorative justice movement, especially about the role that processes of mediation and reparation can play in our responses to crime, its aim should not be the abolition or replacement of punishment: ‘restoration’ is better understood, in this context, as the proper aim of punishment, not as an alternative to it (see further Duff 2001, ch. 3.4–6, but also Zedner 1994).

A similar issue is raised by the second kind of abolitionist theory that we should note here: the argument that we should replace punishment by a system of enforced restitution (see e.g., Barnett 1977; Boonin 2008: ch. 5 — which also cites and discusses a number of objections to the theory). For we need to ask what restitution can amount to, what it should involve, if it is to constitute restitution not merely for any harm that might have been caused, but for the wrong that was done; and it is tempting to answer that restitution for a wrong must involve the kind of apologetic moral reparation, expressing a remorseful recognition of the wrong, that communicative punishment (on the view sketched above) aims to become.

More generally, advocates of restorative justice and of restitution are right to highlight the question of what offenders owe to those whom they have wronged — and to their fellow citizens (see also Tadros 2011 for a focus on the duties that offenders incur). Some penal theorists, however, especially those who connect punishment to apology, will reply that what offenders owe precisely includes accepting, undertaking, or undergoing punishment.

A third alternative approach that has gained some prominence in recent years is grounded in belief in free will scepticism, the view that human behaviour is a result not of free will but of determinism, luck, or chance, and thus that the notions of moral responsibility and desert on which many accounts of punishment (especially retributivist theories) depend are misguided (see s. 5). As an alternative to holding offenders responsible, or giving them their just deserts, some free will sceptics (see Pereboom 2013; Caruso 2021) instead endorse incapacitating dangerous offenders on a model similar to that of public health quarantines. Just as it can arguably be justified to quarantine someone carrying a transmissible disease even if that person is not morally responsible for the threat they pose, proponents of the quarantine model contend that it can be justified to incapacitate dangerous offenders even if they are not morally responsible for what they have done or for the danger they present. One question is whether the quarantine model is best understood as an alternative to punishment or as an alternative form of punishment. Beyond questions of labelling, however, such views also face various lines of critique. In particular, because they discard the notions of moral responsibility and desert, they face objections, similar to those faced by pure consequentialist accounts (see s. 3), that they cannot in principle rule out disproportionate punishment, or that they are inconsistent with respect for persons and with human dignity (see, e.g., Smilansky 2011).

Theoretical discussions of criminal punishment and its justification typically focus on criminal punishment in the context of domestic criminal law. But a theory of punishment must also have something to say about its rationale and justification in the context of international criminal law: about how we should understand, and whether and how we can justify, the punishments imposed by such tribunals as the International Criminal Court. For we cannot assume that a normative theory of domestic criminal punishment can simply be read across into the context of international criminal law (see Drumbl 2007). Rather, the imposition of punishment in the international context raises distinctive conceptual and normative issues.

One key question is which crimes rise to the level of ‘international crimes’ and are thus rightly subject to prosecution and punishment by international rather than domestic institutions. One prominent answer to this question (May 2005) holds that when a state fails to assure its citizens’ safety and security, it thus has no right to prevent international bodies from infringing its sovereignty. Such international intervention is only justified, however, in cases of serious harm to the international community, or to humanity as a whole. Crimes harm humanity as a whole, on this account, when they are group-based either in the sense that they are based on group characteristics of the victims or are perpetrated by a state or another group agent. Such as account has been subject to challenge focused on its harm-based account of crime (Renzo 2012) and its claim that group-based crimes harm humanity as a whole (A. Altman 2006). One response to this sort of account, then, is to reject the international harm requirement and to contend, instead, that a state’s failure to protect its members’ rights is sufficient to justify international intervention (Altman and Wellman 2004), or that international criminal tribunals can be justified if they provide fair procedures for trials and punishments in response to sufficiently heinous crimes (Luban 2010).

We might think, by contrast, that the heinousness of a crime or the existence of fair legal procedures is not enough. We also need some relational account of why the international legal community — rather than this or that domestic legal entity — has standing to call perpetrators of genocide or crimes against humanity to account: that is, why the offenders are answerable to the international community (see Duff 2010). For claims of standing to be legitimate, they must be grounded in some shared normative community that includes the perpetrators themselves as well as those on behalf of whom the international legal community calls the perpetrators to account. (For other discussions of jurisdiction to prosecute and punish international crimes, see W. Lee 2010; Wellman 2011; Giudice and Schaeffer 2012; Davidovic 2015.)