What Is Reflective Writing? (Explained W/ 20+ Examples)

I’ll admit, reflecting on my experiences used to seem pointless—now, I can’t imagine my routine without it.

What is reflective writing?

Reflective writing is a personal exploration of experiences, analyzing thoughts, feelings, and learnings to gain insights. It involves critical thinking, deep analysis, and focuses on personal growth through structured reflection on past events.

In this guide, you’ll learn everything you need to know about reflective writing — with lots of examples.

What Is Reflective Writing (Long Description)?

Table of Contents

Reflective writing is a method used to examine and understand personal experiences more deeply.

This kind of writing goes beyond mere description of events or tasks.

Instead, it involves looking back on these experiences, analyzing them, and learning from them.

It’s a process that encourages you to think critically about your actions, decisions, emotions, and responses.

By reflecting on your experiences, you can identify areas for improvement, make connections between theory and practice, and enhance your personal and professional development. Reflective writing is introspective, but it should also be analytical and critical.

It’s not just about what happened.

It’s about why it happened, how it affected you, and what you can learn from it.

This type of writing is commonly used in education, professional development, and personal growth, offering a way for individuals to gain insights into their personal experiences and behaviors.

Types of Reflective Writing

Reflective writing can take many forms, each serving different purposes and providing various insights into the writer’s experiences.

Here are ten types of reflective writing, each with a unique focus and approach.

Journaling – The Daily Reflection

Journaling is a type of reflective writing that involves keeping a daily or regular record of experiences, thoughts, and feelings.

It’s a private space where you can freely express yourself and reflect on your day-to-day life.

Example: Today, I realized that the more I try to control outcomes, the less control I feel. Letting go isn’t about giving up; it’s about understanding that some things are beyond my grasp.

Example: Reflecting on the quiet moments of the morning, I realized how much I value stillness before the day begins. It’s a reminder to carve out space for peace in my routine.

Learning Logs – The Educational Tracker

Learning logs are used to reflect on educational experiences, track learning progress, and identify areas for improvement.

They often focus on specific learning objectives or outcomes.

Example: This week, I struggled with understanding the concept of reflective writing. However, after reviewing examples and actively engaging in the process, I’m beginning to see how it can deepen my learning.

Example: After studying the impact of historical events on modern society, I see the importance of understanding history to navigate the present. It’s a lesson in the power of context.

Critical Incident Journals – The Turning Point

Critical incident journals focus on a significant event or “critical incident” that had a profound impact on the writer’s understanding or perspective.

These incidents are analyzed in depth to extract learning and insights.

Example: Encountering a homeless person on my way home forced me to confront my biases and assumptions about homelessness. It was a moment of realization that has since altered my perspective on social issues.

Example: Missing a crucial deadline taught me about the consequences of procrastination and the value of time management. It was a wake-up call to prioritize and organize better.

Project Diaries – The Project Chronicle

Project diaries are reflective writings that document the progress, challenges, and learnings of a project over time.

They provide insights into decision-making processes and project management strategies.

Example: Launching the community garden project was more challenging than anticipated. It taught me the importance of community engagement and the value of patience and persistence.

Example: Overcoming unexpected technical issues during our project showed me the importance of adaptability and teamwork. Every obstacle became a stepping stone to innovation.

Portfolios – The Comprehensive Showcase

Portfolios are collections of work that also include reflective commentary.

They showcase the writer’s achievements and learning over time, reflecting on both successes and areas for development.

Example: Reviewing my portfolio, I’m proud of how much I’ve grown as a designer. Each project reflects a step in my journey, highlighting my evolving style and approach.

Example: As I added my latest project to my portfolio, I reflected on the journey of my skills evolving. Each piece is a chapter in my story of growth and learning.

Peer Reviews – The Collaborative Insight

Peer reviews involve writing reflectively about the work of others, offering constructive feedback while also considering one’s own learning and development.

Example: Reviewing Maria’s project, I admired her innovative approach, which inspired me to think more creatively about my own work. It’s a reminder of the value of diverse perspectives.

Example: Seeing the innovative approach my peer took on a similar project inspired me to rethink my own methods. It’s a testament to the power of sharing knowledge and perspectives.

Personal Development Plans – The Future Blueprint

Personal development plans are reflective writings that outline goals, strategies, and actions for personal or professional growth.

They include reflections on strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

Example: My goal to become a more effective communicator will require me to step out of my comfort zone and seek opportunities to speak publicly. It’s daunting but necessary for my growth.

Example: Identifying my fear of public speaking in my plan pushed me to take a course on it. Acknowledging weaknesses is the first step to turning them into strengths.

Reflective Essays – The Structured Analysis

Reflective essays are more formal pieces of writing that analyze personal experiences in depth.

They require a structured approach to reflection, often including theories or models to frame the reflection.

Example: Reflecting on my leadership role during the group project, I applied Tuckman’s stages of group development to understand the dynamics at play. It helped me appreciate the natural progression of team development.

Example: In my essay, reflecting on a failed project helped me understand the role of resilience in success. Failure isn’t the opposite of success; it’s part of its process.

Reflective Letters – The Personal Correspondence

Reflective letters involve writing to someone (real or imagined) about personal experiences and learnings.

It’s a way to articulate thoughts and feelings in a structured yet personal format.

Example: Dear Future Self, Today, I learned the importance of resilience. Faced with failure, I found the strength to persevere a nd try again. This lesson, I hope, will stay with me as I navigate the challenges ahead.

Example: Writing a letter to my past self, I shared insights on overcoming challenges with patience and persistence. It’s a reminder of how far I’ve come and the hurdles I’ve overcome.

Blogs – The Public Journal

Blogs are a form of reflective writing that allows writers to share their experiences, insights, and learnings with a wider audience.

They often combine personal narrative with broader observations about life, work, or society.

Example: In my latest blog post, I explored the journey of embracing vulnerability. Sharing my own experiences of failure and doubt not only helped me process these feelings but also connected me with readers going through similar struggles. It’s a powerful reminder of the strength found in sharing our stories.

Example: In a blog post about starting a new career path, I shared the fears and excitement of stepping into the unknown. It’s a journey of self-discovery and embracing new challenges.

What Are the Key Features of Reflective Writing?

Reflective writing is characterized by several key features that distinguish it from other types of writing.

These features include personal insight, critical analysis, descriptive narrative, and a focus on personal growth.

- Personal Insight: Reflective writing is deeply personal, focusing on the writer’s internal thoughts, feelings, and reactions. It requires introspection and a willingness to explore one’s own experiences in depth.

- Critical Analysis: Beyond simply describing events, reflective writing involves analyzing these experiences. This means looking at the why and how, not just the what. It involves questioning, evaluating, and interpreting your experiences in relation to yourself, others, and the world.

- Descriptive Narrative: While reflective writing is analytical, it also includes descriptive elements. Vivid descriptions of experiences, thoughts, and feelings help to convey the depth of the reflection.

- Focus on Growth: A central aim of reflective writing is to foster personal or professional growth. It involves identifying lessons learned, recognizing patterns, and considering how to apply insights gained to future situations.

These features combine to make reflective writing a powerful tool for learning and development.

It’s a practice that encourages writers to engage deeply with their experiences, challenge their assumptions, and grow from their reflections.

What Is the Structure of Reflective Writing?

The structure of reflective writing can vary depending on the context and purpose, but it typically follows a general pattern that facilitates deep reflection.

A common structure includes an introduction, a body that outlines the experience and the reflection on it, and a conclusion.

- Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for the reflective piece. It briefly introduces the topic or experience being reflected upon and may include a thesis statement that outlines the main insight or theme of the reflection.

- Body: The body is where the bulk of the reflection takes place. It often follows a chronological order, detailing the experience before moving into the reflection. This section should explore the writer’s thoughts, feelings, reactions, and insights related to the experience. It’s also where critical analysis comes into play, examining causes, effects, and underlying principles.

- Conclusion: The conclusion wraps up the reflection, summarizing the key insights gained and considering how these learnings might apply to future situations. It’s an opportunity to reflect on personal growth and the broader implications of the experience.

This structure is flexible and can be adapted to suit different types of reflective writing.

However, the focus should always be on creating a coherent narrative that allows for deep personal insight and learning.

How Do You Start Reflective Writing?

Starting reflective writing can be challenging, as it requires diving into personal experiences and emotions.

Here are some tips to help initiate the reflective writing process:

- Choose a Focus: Start by selecting an experience or topic to reflect upon. It could be a specific event, a general period in your life, a project you worked on, or even a book that made a significant impact on you.

- Reflect on Your Feelings: Think about how the experience made you feel at the time and how you feel about it now. Understanding your emotional response is a crucial part of reflective writing.

- Ask Yourself Questions: Begin by asking yourself questions related to the experience. What did you learn from it? How did it challenge your assumptions? How has it influenced your thinking or behavior?

- Write a Strong Opening: Your first few sentences should grab the reader’s attention and clearly indicate what you will be reflecting on. You can start with a striking fact, a question, a quote, or a vivid description of a moment from the experience.

- Keep It Personal: Remember that reflective writing is personal. Use “I” statements to express your thoughts, feelings, and insights. This helps to maintain the focus on your personal experience and learning journey.

Here is a video about reflective writing that I think you’ll like:

Reflective Writing Toolkit

Finding the right tools and resources has been key to deepening my reflections and enhancing my self-awareness.

Here’s a curated toolkit that has empowered my own reflective practice:

- Journaling Apps: Apps like Day One or Reflectly provide structured formats for daily reflections, helping to capture thoughts and feelings on the go.

- Digital Notebooks: Tools like Evernote or Microsoft OneNote allow for organized, searchable reflections that can include text, images, and links.

- Writing Prompts: Websites like WritingPrompts.com offer endless ideas to spark reflective writing, making it easier to start when you’re feeling stuck.

- Mind Mapping Software: Platforms like MindMeister help organize thoughts visually, which can be especially helpful for reflective planning or brainstorming.

- Blogging Platforms: Sites like WordPress or Medium offer a space to share reflective writings publicly, fostering community and feedback. You’ll need a hosting platform. I recommend Bluehost or Hostarmada for beginners.

- Guided Meditation Apps: Apps such as Headspace or Calm can support reflective writing by clearing the mind and fostering a reflective state before writing.

- Audio Recording Apps: Tools like Otter.ai not only allow for verbal reflection but also transcribe conversations, which can then be reflected upon in writing.

- Time Management Apps: Resources like Forest or Pomodoro Technique apps help set dedicated time for reflection, making it a regular part of your routine.

- Creative Writing Software: Platforms like Scrivener cater to more in-depth reflective projects, providing extensive organizing and formatting options.

- Research Databases: Access to journals and articles through databases like Google Scholar can enrich reflective writing with theoretical frameworks and insights.

Final Thoughts: What Is Reflective Writing?

Reflective writing, at its core, is a deeply personal practice.

Yet, it also holds the potential to bridge cultural divides. By sharing reflective writings that explore personal experiences through the lens of different cultural backgrounds, we can foster a deeper understanding and appreciation of diverse worldviews.

Read This Next:

- What Is a Prompt in Writing? (Ultimate Guide + 200 Examples)

- What Is A Personal Account In Writing? (47 Examples)

- Why Does Academic Writing Require Strict Formatting?

- What Is A Lens In Writing? (The Ultimate Guide)

Reflective writing

Learn how to write a reflective text about a learning experience.

Do the preparation task first. Then read the text and tips and do the exercises.

Preparation

Matching_MjMwMzk=

In January I spent three weeks volunteering as an English teacher in my town. I've been thinking about becoming an English teacher for a while so it was a good opportunity to see what it's like. The students had all just arrived to start a new life in the UK and they had a range of levels from beginner to intermediate. They came from a variety of countries and had very different backgrounds and experiences.

For me, the most important thing was the relationship with the students. I was nervous at first and did not feel confident about speaking in front of people. However, I found it easy to build good relationships with the students as a class and as individuals and I soon relaxed with them. It was a challenge to encourage the lower-level students to speak in English, but at least they understood a lot more at the end of the course.

At first, planning lessons took a really long time and I was not happy with the results. Classes seemed to be too difficult for some students and too easy for others, who finished quickly and got bored. I found it was better to teach without a course book, adapting materials I found online to suit their needs. I learned to take extra activities for students who finished early and that was much better.

I still need to continue improving my lesson planning. I would like more ideas for teaching mixed-ability groups and I want to plan the whole course better next time. That way students have a focus for each lesson and a sense of progress and of what they've covered. I'm also going to put more confident students with beginners when they work in pairs so conversation activities give everyone more chance to speak and students can help each other.

Overall, it was a really positive experience and I learned a lot. I've decided that I would like to become an English teacher in the future.

- Reflective writing is more personal than other types of academic writing. You can use the first person ( I ... , My ... , etc.) and explain how you felt.

- Think about the experience in detail. Explain what went well and what was challenging, and say what you learned in the process.

- Short introduction to the situation

- Evaluate the most important things about the experience, including solutions to problems

- Say what you would do differently next time

- Say what you learned overall.

- Keep the focus on your learning process and what you will do better in future.

TrueOrFalse_MjMwNDA=.xml

Grouping_MjMwNDE=.xml

GapFillTyping_MjMwNDI=.xml

What was your last challenging learning experience?

Language level

My last challenging experience was learning English,because I live with my parents and sister and I dont have own room,so I must learning in living room and it is so difficult.They are constantly going back and forth and I very rarely have some time for learning in calm.

- Log in or register to post comments

Hey guys! I've been trying to learn English since I was a teenager. At that time, even though I took classes and studied a little, I don't think I did my best. I wasn't really motivated. A few years later, I'm trying again to regain that knowledge and go further.

I move to London when I was 16 and I joint to college to learn English. At that time I wasn't really focusing well with learning and I never imagined that I would struggle in the future with this language. The challenging that I face nowadays at work place to complete my patient's notes and at the university to understand the subjects. Finding difficult to put into my own words when I read a context and struggling for my assignments. I choose this platform to improve my writing level and stay more focused with my study. Therefore, I decided to spend everyday at least an hour to improve my English level.

Thank you. Lalitha

when I was going to start learning programming 2 years ago, I spent a vast changing process. At first, I didn't know anything about it. actually, something would attract me to it. at that time I was working as a full-time sales expert in a big company. As a result, I didn't have enough time but I decided to start learning for 30 minutes in the morning.

In the beginning, I would take a lot of time to understand the concepts and also much time to review the concepts which I had learned before. Sometimes It was so tedious and frustrating because I would spend a lot of time trying to understand a concept but after a week I would really forget the details. As it turned out, I found out I had to take notes and make a plan to review them every two days.

Another problem was that I was short of time. I couldn't get around to reviewing the notes steadily. none the less I would use all of my free time including weekends and my two days off in a month. but a situation came up to me caused I had two hours of free time a day at work. this happening was a gift for me for my passion and persistence.

I continued this trend for nine months. My mind had become sharper and faster in learning and analyzing new concepts. my mind had nothing to do with one last year. On the one hand, I had fallen in love with this new skill, and on the other hand, I couldn't find in my heart to resign. What it boils down to is that I was wondering whether I stayed on at my job or put my back into my favorite skill in order to become a specialist in it.

To cut a long story short, I decided to resign and study focused for a while. this decision improved my efficiency and made me use my intellectual capabilities to the maximum. It was one of the best gifts that I had ever given to myself. I allowed myself to do what makes me happy and alive and enjoy doing it.

Hello Ensiye,

I just wanted to thank you for your contribution and applaud you for your efforts. I'm so glad it worked out for you.

All the best, Kirk LearnEnglish team

hello Dear Kirk Thanks for your kindness Doing the tasks of the lessons has made my learning process regular I'm glad to be here Best regards Ensiye

My last challenge it was about analyze an international conflict in my major, so I read many books, texts, notes about conflict but isn't easy for me to find information about the topic. Overall it was great, I approve my course with a good grade. (:

Hi everybody. I'm trying to translate my project into English but honestly, it's very hard. I know is better to hire a translator but I want to learn more by translating it. I would like to share the first sentence of my project with you. Is it possible to take a look at it, please? and tell which part is wrong and why? I need to know can you understand it or not. " The global publishing network is a mechanism designed to unite publishers to integrate publishing industry. The network by revolutionizing the publishing process, delivers printed versions of text-based works such as books, articles, and magazines in less than an hour, regardless of the client’s location, and without printing and storing the works beforehand. During this process, if only a few seconds have elapsed since publishing a work in the network, the selling process of its print version starts at such speed. The objective of this mechanism is to remove intermediaries and storehouses, reduce the time of producing and delivering, and provide global access without geographical, cultural, and linguistic barriers. The network also strives to be a global gate for income generation for game, song, and movie companies and producers and sells Blu-Ray versions of their works through this mechanism. The distribution mechanism is the main idea of the network that completes many other features of this project."

Hello aliyaseri,

That sounds like a great idea and I'm sure you'll learn a lot, but I'm afraid we don't correct people's texts.

If you have a specific question about a specific sentence, please let us know.

I started learning English at school, when I was ten. I didn't like this language because i thought it was bored. I didn´t pay attention to the classes so I din't know anything. Now, I have absolutely notion that i should have paid attention. I really started learning English, last year, by myself, because in school, the level of English was already B1 and I was in A1. I started learning randoom things and with that I realize that my main problem was the grammar. I studied all the verb tenses. Right now, I still have difficulties on that but I am improving everyday. I´m going to Turkey next week without anyone that I know and I will spend one week there speaking just in English. Probably that will be a challenge for me but I want to explore my limits. My main problem now is the vocabulary. I have a lack of vocabulary wich doesn't let me maintain a normal conversation. I'm doing my best to pass that but I know it takes time. I'm in the B1 level right, and I'm so happy that I managed to be here. I'm really pround of me.

Online courses

Group and one-to-one classes with expert teachers.

Learn English in your own time, at your own pace.

One-to-one sessions focused on a personal plan.

Get the score you need with private and group classes.

- Academic Skills

- Reading, writing and referencing

Reflective writing

Advice on how to write reflectively.

Reflective writing gives you an opportunity to think deeply about something you've learned or an experience you've had.

Watch the video below for a quick introduction to reflective writing. The video includes an example of reflecting on practice, but the approach is equally useful when reflecting on theory.

Video tutorial

Reflecting on practice.

Reflective writing may ask you to consider the link between theory (what you study, discuss and read about at university) and practice (what you do, the application of the theory in the workplace). Reflection on practical contexts enables you to explore the relationship between theory and practice in an authentic and concrete way.

"Yesterday’s class brought Vygotsky’s concepts of scaffolding and the ‘significant other’ into sharp focus for me. Without instruction, ‘Emily’ was able to scaffold ‘Emma’s’ solving of the Keystone Puzzle without directing her or supplying her with the answer – she acted as the ‘significant other’. It really highlighted for me the fact that I do not always have to directly be involved in students’ learning, and that students have learning and knowledge they bring to the classroom context."

What this example does well:

- Links theory to practice.

- Clearly states where learning occurred.

De-identify actual people you have observed or dealt with on placement or work experience using pseudonyms (other names, job titles, initials or even numbers so that real identities are protected). E.g.:

- "It was great to observe ‘Lee’ try to..."

- "Our team leader’s response was positive…"

- "I observed G’s reaction to this..."

- "Student Four felt that this was…"

"The lectures and tutes this semester have broadened my views of what sustainability is and the different scales by which we can view it . I learned that sustainability is not only something that differs at an individual level in terms of how we approach it ourselves, but also how it differs in scale. We might look at what we do individually to act sustainably, such as in what and how we recycle, but when we think about how a city or state does this, we need to consider pollution, rubbish collection and a range of other systems that point to sustainability on a much larger scale."

- Clearly states where learning occurred

- Elaborates on key issues

- Gives examples.

"On the ward rounds yesterday, I felt Mr G’s mobility had noticeably improved from last week. This may be due to the altered physio program we have implemented and it allowed me to experience a real feeling of satisfaction that I had made a real difference."

Action verbs are usually expressing feelings and thoughts in reflective writing, e.g. felt, thought, considered, experienced, wondered, remembered, discovered, learned.

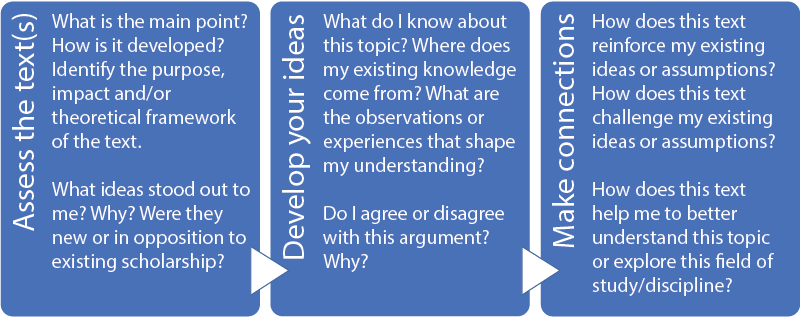

Reflecting on theory

Some reflection tasks are purely theoretical, where you are asked to consider texts you have read, or ideas you may have discussed in tutorials, and reflect on them.

"Comparing the approaches of Mayr and Ulich (2009) and Laevers (2005) to what 'wellbeing' means for the early childhood setting was very illustrative in that I discovered they seek to do similar things but within different frameworks. Analysing the two constructs highlighted that the detail in Mayr and Ulich’s framework provided a much richer framework in defining and measuring wellbeing than Laevers’ does."

- References correctly.

- Considers what the theory has shown.

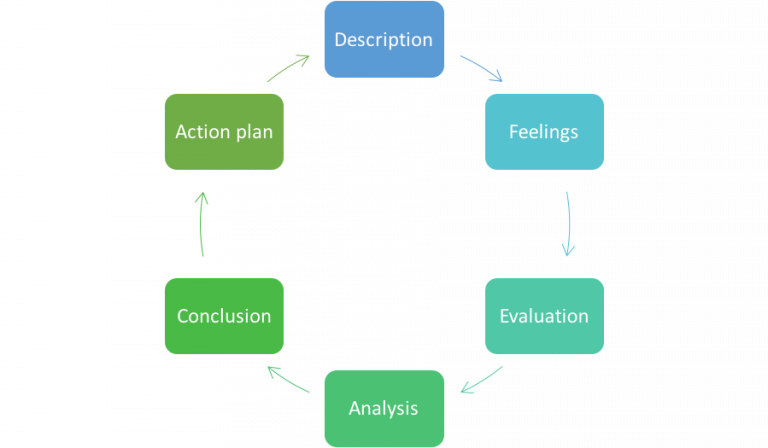

Using the DIEP model

When writing reflectively for the first time, it’s not uncommon to produce a summary or description of the event or experience without deeply reflecting on it.

Reflective writing needs to go beyond simply summarising what happened. Your reader needs to gain an insight into what the experience meant to you, how you feel about it, how it connects to other things you’ve experienced or studied and what you plan to do in response.

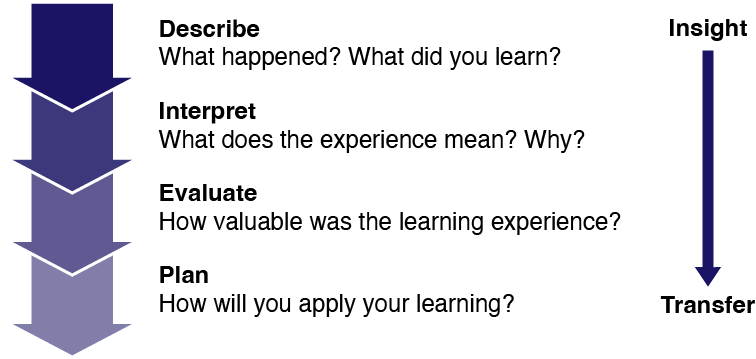

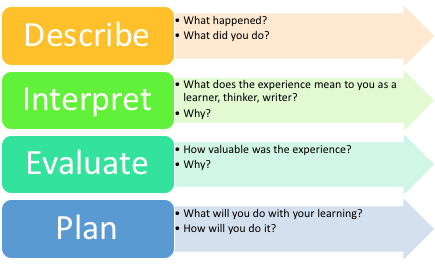

To be sure you don’t leave out any of these critical elements of reflection, consider writing using the describe, interpret, evaluate, plan (DIEP) model to help.

DIEP approach adapted from: RMIT Study and Learning Centre. (2010). Reflective writing: DIEP .

You can and should refer to yourself in your reflection using personal pronouns, e.g. I, we...

Begin by describing the situation. What did you see, hear, do, read or see? Be as brief and objective as possible.

Starting phrases:

- The most interesting insight from my lecture this week is ...

- A significant issue I had not realised until now is ...

- I now realise (understand ...) that ...

Interpret what happened. What new insights have you gained? How does this experience connect with other things you’ve learned or experienced before? How did the experience make you feel?

- This experience idea is relevant to me because…

- This reminded me of the idea that…

- A possible implication could be…

Make a judgement. How useful was this experience for you? What is your opinion? Why do you think this might be?

- Having realised the importance of ..., I can now understand…

- This experience will change the way I view ...

- Being able to see… in this way is extremely valuable for me because…

Comment on how this experience might inform your future thoughts or actions. How could you apply what you’ve learned from the experience in the future? How might the experience relate to your degree or future professional life?

- This is beneficial to me as my future career requires…

- In order to further develop this skill…I will…

- Next time…I will…by…

[TS] The most surprising insight I have gained so far is how important recording and distributing succinct and accurate information is to the success of the project. [D] In the first week of my internship, I was asked to record some meeting minutes and distribute them to the project team and the client. [I] I initially felt offended as the task appeared trivial to me; it was something we rarely did during team meetings at university. [E] However, after speaking with my industry supervisor, I began to understand how important it is to keep a clear record of the meaningful points raised during meetings. [I] Making accurate notes of the key outcomes was harder than I expected as the rest of my team was relying on my minutes to know what they needed to do. [D]After reviewing my minutes, my supervisor agreed that they were sufficiently clear and accurate. [I] I’ve realised that poorly recorded minutes could have resulted in missed deadlines, miscommunication and costly implications for our contract. [P] To improve my ability to take notes I plan on reviewing the minutes made by my colleagues for other meetings and to investigate note taking techniques such as mind mapping (Trevelyan, 2014). Mind mapping uses links and annotations to record relationships between words and indicate significance. [I] This will help me to continue to develop my skills in this area and develop my ability to “prepare high quality engineering documents” as part of attaining the Stage 1 competency of written communication (Engineers Australia, 2018).

Trevelyan, J. P. (2014). The making of an expert engineer: How to have a wonderful career creating a better world and spending lots of money belonging to other people . Leiden, The Netherlands: CRC Press/Balkema.

Ask yourself:

- Have I based my reflection on a specific incident, activity, idea or example?

- Have I sufficiently critically analysed the situation?

- Have I integrated theory in a meaningful way? Can I elaborate further to demonstrate the relevance of the idea and my understanding of it?

- Are my plans specific enough? Can I be more concrete?

When editing your draft, try colour coding each element of DIEP to be sure you have a balance of elements.

Looking for one-on-one advice?

Get tailored advice from an Academic Skills Adviser by booking an Individual appointment, or get quick feedback from one of our Academic Writing Mentors via email through our Writing advice service.

Go to Student appointments

Introduction to Reflection

There are many ways to produce reflection in writing. Try using these examples to kick-start your reflective writing.

Open each drop-down to see a different reflective writing example and exercise.

The Six Minute Write (Bolton, 2014)

If you are being asked to write reflectively you may feel that you do not know where to begin. Bolton’s Six Minute Writing exercise is a useful way to help get you started.

Peter has just started a course to train to be a counsellor and his tutor is asking every student to reflect on their learning and the development of their interpersonal skills. Peter is unsure where to start as reflective writing is a new thing for him, so he decides to try the Six Minute Write.

“Well, I’ve never written anything like this before! When I wrote at school I was always told to be really careful – make sure your spelling and grammar are correct, don’t use abbreviations, make it sound formal. This feels quite liberating! But, is it any good? The tutor says ‘Just write what’s in your head’ so here goes.

Today we did our first role play exercises and how scary was that? I always knew that the course would involve this and I do enjoy talking with people, but trying out listening skills and asking open questions is all really difficult. I felt so nervous and forgot what to do. The people I was working with seemed so much better than me – I know I’ve got so much to learn it’s frightening. Will I ever be able to do this? I really don’t know, but I do know I’m going to try.”

Use Bolton’s (2014, p. 136) Six Minute Write exercise to begin any writing exercise, whether academic or reflective, personal or formal.

Here are Bolton’s pointers:

- Write for six minutes without stopping.

- Write whatever comes to mind and let your writing flow freely.

- Keep writing and do not pause to think too much about what you are writing.

- Do not pause to analyse what you have written, otherwise you will be tempted to write what you think you should write rather than what you want to write.

- Keep writing even if it does not make much sense to you.

- Do not worry about spelling, punctuation, grammar or jargon.

- Allow yourself to write anything.

- This is your writing and whatever you write is correct because it is yours. Remember, no-one else needs to read what you have written.

- Stop after six minutes and look at how much you have been able to write.

If we pay attention to how we think, we’ll soon notice that we are often in conversation with ourselves.

We have a kind of internal dialogue as we go about our day, making decisions (“The red top or the blue one?”) observing the world (“Beautiful day. But chilly. Where did I put my gloves?”) and maintaining self-awareness (“Oh goodness, she’s heading this way. You’re nervous? Interesting. Calm down. Be polite.”).

Reflective writing can take the shape of dialogue and be structured as a conversation with different aspects of yourself. We all have multiple identities (child, parent, student, employee, friend etc.) and each aspect of ourselves can take a different perspective on a situation.

Dialogic reflection harnesses these multiple perspectives to explore and inquire about ourselves in a certain situation, often when the purpose or outcome is unknown.

So now they’re encouraging us to try different types of reflective writing. I like the idea of this dialogical writing thing – feels like having a conversation with myself, so I think I’ll have a go. Not sure how it will pan out but I’m going to imagine talking with my organised self (OS) and my critical self (CS) and see how it goes.

OS – so doing really well at the moment, feeling pretty much on track with things and definitely on top.

CS – so how long do you think that will last? I know what you’re like! You always do this – think things are ok, sit back, relax and then get behind.

OS – do I? Umm… suppose you might be right…

CS – what do you mean, might be right?

OS – ok, you are right!

CS – and we know where this ends up, don’t we? Panic mode!

OS – and I need to avoid that. So, let’s think about what I can do. Look at the coming week and month and start planning!

Focus on an issue or concern that you have relating to your studies or practice. Imagine you are having a conversation with a friend about the issue because you want to get their perspective. Write a dialogue with “them” that explores your concerns. Raise any questions you’d like answered.

If need be, write another dialogue on the same issue with another “friend” to explore another perspective.

Once you’ve finished, re-read your conversation. Did your “friend” offer any new perspectives on the issue that hadn’t occurred to you before you began writing? Are any of these worth reflecting on further?

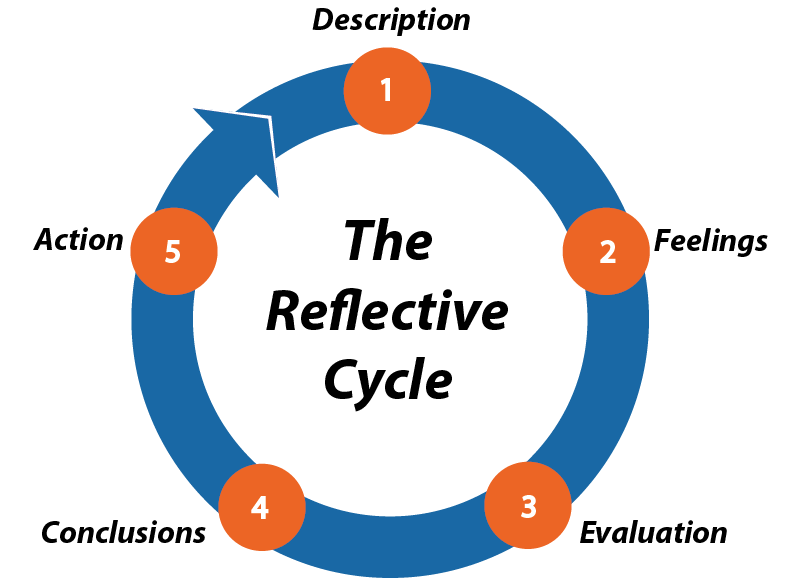

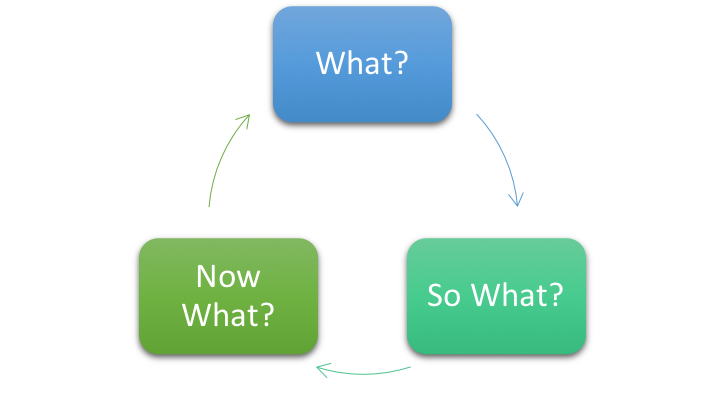

Driscoll (2007) What?, So what?, Now what?

Driscoll’s (2007) ‘What?’ model is a straightforward reflective cycle of 3 parts. Evolved from Borton’s (1970) Developmental Framework, it has 3 stages that ask us to consider What?, So what?, and Now what?

Step 1 – What? – involves writing a description of an event or an experience.

Step 2 – So what? – here we reflect on the event or experience and start to analyse selected aspects of it, considering why they were important and how they impacted the whole.

Step 3 – Now what? – a range of proposed action points are devised following the experience, focusing on what has been learned.

Dan is training to be a nurse in elderly care and wants to reflect on the experiences he is gaining on his placement. Dan decides to use the questions in Driscoll’s model to help him to begin to analyse what he is learning.

Step 1 – What?

Today I was observing an experienced community nurse change a dressing on a man’s leg that is badly infected. The man was nervous and became very distressed – he has had dressings replaced regularly and knows that the process is very painful. I felt awful about causing him more pain. The community nurse seemed very calm and spoke to him in a reassuring way. She asked him if he would like some pain relief and he said yes. She sat with him for ten minutes to make sure that the pain relief was working and spoke with him about his grandson’s visit that he was looking forward to at the weekend. This definitely seemed to put him at ease.

Step 2 – So what?

She made it all look so easy. How would I cope if I had to do this? As a nurse I am meant to relieve pain not cause it. She focused on the patient while I focused on myself.

Step 3 – Now what?

I learned a lot from the community nurse. She was very caring but firm. She knew the man’s dressing needed to be changed but did everything in a very calm and kind way. She distracted him and helped him to relax. These are all strategies that I can try in the future if I have to do this. Nursing isn’t only about my clinical skills; my interpersonal skills are vital, as is compassion and understanding for my patients.

Driscoll has formulated some useful questions to help us to use the model effectively, including:

Step 1 – What? – how did I react and what did others do who were involved?

Step 2 – So what? – do I feel troubled in any way, and if so, how?

Step 3 – Now what? – how can I change my approach if I face a similar situation again and what are my main learning points? What different options are there for me?

Write some notes about an experience you have had recently where you feel you have learned a lot. Can you use the stages of Driscoll’s cycle to develop this into a short reflection?

Note: Driscoll’s model is useful when you are new to professional practice and it seems like there is so much to learn. In particular, the question ‘Do I feel troubled in any way?’ is useful as our feelings can act as a prompt to deeper thinking. However, after a while you may find that you want to explore at a more complex level and move on to other approaches. It’s important to allow space for your reflective skills to develop in the same way as your professional skills.

Some small scale reflective questions :

- What were 3 things that went well today/this week? How do you know?

- What was a situation today/this week where I could have done better? How?

- What was your biggest challenge today/this week? How did you overcome it?

- What was the predominant feeling you had today/this week? Why?

- What made you happy/sad/frustrated/angry/etc today/this week? Can you find some way of having more or less of the identified aspects?

Some larger scale reflective questions :

- Am I optimising my time, energy and performance according to my values, goals and objectives?

- Am I making the most of opportunities available to me? Am I working effectively within any fixed restrictions? Where there are barriers, am I identifying them and tackling or circumventing them where possible?

- Do my values, goals and objectives still align with each other? Is this reflected in how I am spending my time?

- Are my goals still the right ones to deliver on my values? Should/Can I refine or revise the strategies I am using for fulfilling my values and goals?

Where you have been

Where you are now, related links, © 2021. this work is licensed under a cc by-nc-sa 4.0 license..

- Cambridge Libraries

Study Skills

Reflective practice toolkit, introduction.

- What is reflective practice?

- Everyday reflection

- Models of reflection

- Barriers to reflection

- Free writing

- Reflective writing exercise

- Bibliography

Many people worry that they will be unable to write reflectively but chances are that you do it more than you think! It's a common task during both work and study from appraisal and planning documents to recording observations at the end of a module. The following pages will guide you through some simple techniques for reflective writing as well as how to avoid some of the most common pitfalls.

What is reflective writing?

Writing reflectively involves critically analysing an experience, recording how it has impacted you and what you plan to do with your new knowledge. It can help you to reflect on a deeper level as the act of getting something down on paper often helps people to think an experience through.

The key to reflective writing is to be analytical rather than descriptive. Always ask why rather than just describing what happened during an experience.

Remember...

Reflective writing is...

- Written in the first person

- Free flowing

- A tool to challenge assumptions

- A time investment

Reflective writing isn't...

- Written in the third person

- Descriptive

- What you think you should write

- A tool to ignore assumptions

- A waste of time

Adapted from The Reflective Practice Guide: an Interdisciplinary Approach / Barbara Bassot.

You can learn more about reflective writing in this handy video from Hull University:

Created by SkillsTeamHullUni

- Hull reflective writing video transcript (Word)

- Hull reflective writing video transcript (PDF)

Where might you use reflective writing?

You can use reflective writing in many aspects of your work, study and even everyday life. The activities below all contain some aspect of reflective writing and are common to many people:

1. Job applications

Both preparing for and writing job applications contain elements of reflective writing. You need to think about the experience that makes you suitable for a role and this means reflection on the skills you have developed and how they might relate to the specification. When writing your application you need to expand on what you have done and explain what you have learnt and why this matters - key elements of reflective writing.

2. Appraisals

In a similar way, undertaking an appraisal is a good time to reflect back on a certain period of time in post. You might be asked to record what went well and why as well as identifying areas for improvement.

3. Written feedback

If you have made a purchase recently you are likely to have received a request for feedback. When you leave a review of a product or service online then you need to think about the pros and cons. You may also have gone into detail about why the product was so good or the service was so bad so other people know how to judge it in the future.

4. Blogging

Blogs are a place to offer your own opinion and can be a really good place to do some reflective writing. Blogger often take a view on something and use their site as a way to share it with the world. They will often talk about the reasons why they like/dislike something - classic reflective writing.

5. During the research process

When researchers are working on a project they will often think about they way they are working and how it could be improved as well as considering different approaches to achieve their research goal. They will often record this in some way such as in a lab book and this questioning approach is a form of reflective writing.

6. In academic writing

Many students will be asked to include some form of reflection in an academic assignment, for example when relating a topic to their real life circumstances. They are also often asked to think about their opinion on or reactions to texts and other research and write about this in their own work.

Think about ... When you reflect

Think about all of the activities you do on a daily basis. Do any of these contain elements of reflective writing? Make a list of all the times you have written something reflective over the last month - it will be longer than you think!

Reflective terminology

A common mistake people make when writing reflectively is to focus too much on describing their experience. Think about some of the phrases below and try to use them when writing reflectively to help you avoid this problem:

- The most important thing was...

- At the time I felt...

- This was likely due to...

- After thinking about it...

- I learned that...

- I need to know more about...

- Later I realised...

- This was because...

- This was like...

- I wonder what would happen if...

- I'm still unsure about...

- My next steps are...

Always try and write in the first person when writing reflectively. This will help you to focus on your thoughts/feelings/experiences rather than just a description of the experience.

Using reflective writing in your academic work

Many courses will also expect you to reflect on your own learning as you progress through a particular programme. You may be asked to keep some type of reflective journal or diary. Depending on the needs of your course this may or may not be assessed but if you are using one it's important to write reflectively. This can help you to look back and see how your thinking has evolved over time - something useful for job applications in the future. Students at all levels may also be asked to reflect on the work of others, either as part of a group project or through peer review of their work. This requires a slightly different approach to reflection as you are not focused on your own work but again this is a useful skill to develop for the workplace.

You can see some useful examples of reflective writing in academia from Monash University , UNSW (the University of New South Wales) and Sage . Several of these examples also include feedback from tutors which you can use to inform your own work.

Laptop/computer/broswer/research by StockSnap via Pixabay licenced under CC0.

Now that you have a better idea of what reflective writing is and how it can be used it's time to practice some techniques.

This page has given you an understanding of what reflective writing is and where it can be used in both work and study. Now that you have a better idea of how reflective writing works the next two pages will guide you through some activities you can use to get started.

- << Previous: Barriers to reflection

- Next: Free writing >>

- Last Updated: Jun 21, 2023 3:24 PM

- URL: https://libguides.cam.ac.uk/reflectivepracticetoolkit

© Cambridge University Libraries | Accessibility | Privacy policy | Log into LibApps

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Reflective writing

What is reflective writing?

Reflective writing is the process of putting your intentional reflective thinking into text and documenting the thinking and learning that has taken place. It also involves reflecting on an experience, interpreting and evaluating what happened, and planning how the lessons you’ve learnt can be applied in the future. Reflective writing might be for a wide audience, a specific reader, or undertaken as a personal activity.

Why is reflective writing important?

Reflective writing isn’t just venting your feelings, or something that needs to be done for the sake of paperwork or assessment. It also helps develop your critical thinking and metacognitive skills, giving you a lot more control over your own learning and professional development. These are skills which improve the more you put them into practice, so working on your reflective writing skills is an investment in your present and future self.

Reflective writing tasks help you work through the reflective process, and the documents you create through this process are evidence that reflection has occurred. They demonstrate the knowledge you have gained and how you have done so to the reader, who might be your university tutor, your professional mentor, or your present or future employer. It shows them that you are able to reflect, analyse, and come to relevant and logical conclusions based on your experience. Reflective writing documents your conscious improvement and awareness of your strengths and weaknesses and how that affects your personal, academic and professional life. It can provide rich evidence that you no longer need study or guidance to continue improving in your field and that you are ready to move on to a new challenge or opportunity.

You have probably already done some form of reflective writing; it could have been for your studies, your job, or just your personal learning or enjoyment. Can you think of anything you’ve written that involved describing events, interpreting, and evaluating them?

- What type of text was it?

- Why did you write the text?

- Did anyone read it? Who?

- Was it helpful? Did you learn anything from it?

Where might you use reflective writing?

Now have a look through the slideshow to see some different types of reflective tasks and read about how they are used.

Characteristics of reflective academic writing

As you have seen, there are many forms of reflective writing, and the type of reflective writing you do will usually depend on why you’re writing it, your intended audience, and your discipline or profession. In higher education, reflective writing coursework and assessments vary in content across multiple disciplines, but most share some common characteristics.

L anguage and structure

Academic reflective writing is almost always written in the first person. As it’s for an academic audience, the language should be formal or semi-formal and you should use key terminology and vocabulary from the related discipline (e.g., the language you use for a reflection related to teaching practice, will be different to a scientific research reflection).

The text should be in logical paragraphs and generally follows a set structure with three main parts:

- a description of the experience and the writer’s thoughts and feelings (describe)

- the reflection on the experience – interpreting why the writer felt or acted a particular way (interpret and evaluate)

- the result of the experience – the writer’s plans based on the experience and what they have learnt (plan).

The DIEP model is one example of a structure you can use to organise a reflective writing task. This model requires you to Describe (what happened? what did you learn?), Interpret (what does the experience mean? why?), Evaluate (how valuable was the learning experience?) and Plan (how will you apply your learning?). Find out more about the DIEP model on RMIT’s Learning Lab

Although the subject of a written reflection will change across disciplines, the expectations of the content will remain the same:

- it should express the writer’s personal experiences, thoughts, and feelings, but show objective reasoning when reflecting on the event.

- the descriptions of events and experiences should be succinct, with a greater focus on the why and how of the experience.

- the reflection should demonstrate how the writer has learnt from what happened and how it will inform their future practice.

Reflective writing tasks for coursework or assessment will generally read by an educator. Tasks that are graded will have instructions and criteria explaining what should be included. This gives the writer a clear idea of how they will be graded and what they need to focus on.

Academic reflections often require the writer to connect personal experiences to academic theory studied in class, and to cite sources to give credibility. If you have used academic sources, you’ll need to include references, but you don’t need to reference your own thoughts and opinions.

Useful language for reflective writing

When doing academic reflective writing, it’s crucial for the reader to be able to follow your thought process easily. That’s why using language that effectively communicates your ideas is so important. Take a look at the expandable sections below to see specific types of vocabulary and sentence structures that can be useful when writing reflectively.

For a useful overview of reflective thinking and reflective writing, check out this video from the University of Hull:

Now that you have an understanding of reflective thinking and writing, it’s time to see how these skills are used in specific contexts. The following pages contain information on how reflective practice is used in education, healthcare, business, and design.

This page includes content adapted from:

- Reflective Writing by University of York Library licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

- Reflective Practice Toolkit by Cambridge University Libraries licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Skills Team Hull Uni . (2013). Reflective Writing. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QoI67VeE3ds

Key Transferable Skills Copyright © 2024 by RMIT University Library is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.18: Reflective Writing

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 58227

- Lumen Learning

Learning Objectives

- Examine the components of reflective writing

Reflective Writing

Reflective writing includes several different components: description, analysis, interpretation, evaluation, and future application. Reflective writers must weave their personal perspectives with evidence of deep, critical thought as they make connections between theory, practice, and learning. The steps below should help you find the appropriate balance among all these factors.

1st Step: Review the assignment

As with any writing situation, the first step in writing a reflective piece is to clarify the task. Reflective assignments can take many forms, so you need to understand exactly what your instructor is asking you to do. Some reflective assignments are short, just a paragraph or two of unpolished writing. Usually the purpose of these reflective pieces is to capture your immediate impressions or perceptions. For example, your instructor might ask you at the end of a class to write quickly about a concept from that day’s lesson. That type of reflection helps you and your instructor gauge your understanding of the concept.

Other reflections are academic essays that can range in length from several paragraphs to several pages. The purpose of these essays is to critically reflect on and support an original claim(s) about a larger experience, such as an event you attended, a project you worked on, or your writing development. These essays require polished writing that conforms to academic conventions, such as articulation of a claim and substantive revision. They might address a larger audience than you and your instructor, including, for example, your classmates, your family, a scholarship committee, etc. It’s important before you begin writing, that you can identify the assignment’s purpose, audience, intended message or content, and requirements.

2nd Step: Generate ideas for content

As you generate ideas for your reflection, you might consider things like:

- Recollections of an experience, assignment, or course

- Ideas or observations made during that event

- Questions, challenges, or areas of doubt

- Strategies employed to solve problems

- A-ha moments linking theory to practice or learning something new

- Connections between this learning and prior learning

- New questions that arise as a result of the learning or experience

- New actions taken as a result of the learning or experience

3rd Step: Organize content

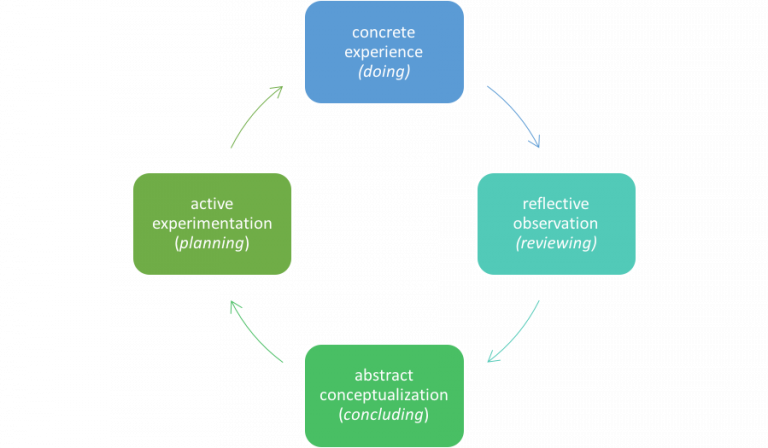

Researchers have developed several different frameworks or models for how reflective writing can be structured. For example, one method has you consider the “What?” “So what?” and “Now what?” of a situation in order to become more reflective. First, you assess what happened and describe the event, then you explain why it was significant, and then you use that information to inform your future practice. [1] [2] Similarly, the DIEP framework can help you consider how to organize your content when writing a reflective piece. Using this method, you describe what happened or what you did, interpret what it means, evaluate its value or impact, and plan steps for improving or changing for the future.

The DIEP Model of reflective writing

The DIEP model (Boud, Keogh & Walker,1985) organizes the reflection into four different components:

Remember, your goal is to make an interpretive or evaluative claim, or series of claims, that moves beyond obvious statements (such as, “I really enjoyed this project”) and demonstrates you have come to a deeper understanding of what you have learned and how you will use that learning.

In the example below, notice how the writer reflects on her initial ambitions and planning, the a-ha! moment, and then her decision to limit the scope of a project. She was assigned a multimodal (more than just writing) project, in which she made a video, and then reflected on the experience:

Student Example

Keeping a central focus in mind applies to multimodal compositions as well as written essays. A prime example of this was in my remix. When storyboarding for the video, I wanted to appeal to all college students in general. Within my compressed time limit of three minutes, I had planned to showcase numerous large points. It was too much. I decided to limit the scope of the topic to emphasize how digitally “addicted” college students are, and that really changed the project in significant ways.

4th Step: Draft, Revise, Edit, Repeat

A single, unpolished draft may suffice for short, in-the-moment reflections, but you may be asked to produce a longer academic reflection essay, which will require significant drafting, revising, and editing. Whatever the length of the assignment, keep this reflective cycle in mind:

- briefly describe the event or action;

- analyze and interpret events and actions, using evidence for support;

- demonstrate relevance in the present and the future.

The following video, produced by the Hull University Skills Team, provides a great overview of reflective writing. Even if you aren’t assigned a specific reflection writing task in your classes, it’s a good idea to reflect anyway, as reflection results in better learning.

You can view the transcript for “Reflective Writing” here (opens in new window) .

Check your understanding of reflective writing and the things you learned in the video with these quick practice questions:

https://h5p.cwr.olemiss.edu/h5p/embed/60

- Driscoll J (1994) Reflective practice for practise - a framework of structured reflection for clinical areas. Senior Nurse 14 (1):47–50 ↵

- Ash, S.L, Clayton, P.H., & Moses, M.G. (2009). Learning through critical reflection: A tutorial for service-learning students (instructor version). Raleigh, NC. ↵

Contributors and Attributions

- Process of Reflective Writing. Authored by : Karen Forgette. Provided by : University of Mississippi. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Reflective Writing. Provided by : SkillsTeamHullUni. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QoI67VeE3ds&feature=emb_logo . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Frameworks for Reflective Writing. Authored by : Karen Forgette. Provided by : University of Mississippi. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Practice-based and reflective learning

- Reflective thinking

- Introduction

Key features

Using academic evidence, selecting the content, getting the language right, useful links for reflective learning.

- Reflective writing video tutorial (University of Hull) A clear explanation of things to think about when you are writing reflectively.

- Study Advice Helping students to achieve study success with guides, video tutorials, seminars and one-to-one advice sessions.

- Academic Phrasebank Use this site for examples of linking phrases and ways to refer to sources.

- Academic writing LibGuide Expert guidance on punctuation, grammar, writing style and proof-reading.

- Essay writing LibGuide Expert guidance on writing essays for university.

- Report writing LibGuide Expert guidance on planning, structuring and writing reports at university.

- Dissertations and major projects LibGuide Expert guidance on planning, researching and writing dissertations and major projects.

Follow the guidelines for your course. There is likely to be a word limit: you cannot write about everything, so select what will illustrate your discussion best. Remember that most of the marks awarded for your work are likely to be for the reflective insights and not for the description of events, so keep your descriptions brief and to the point.

- Reflective writing (Study Guide) You can also print off an abridged PDF version of this guide. This is designed to be printed double-sided on A4, then folded to make an A5 guide.

Reflective writing is a way of processing your practice-based experience to produce learning. It has two key features:

1) It integrates theory and practice. Identify important aspects of your reflections and write these using the appropriate theories and academic context to explain and interpret your reflections. Use your experiences to evaluate the theories - can the theories be adapted or modified to be more helpful for your situation?

2) It identifies the learning outcomes of your experience. So you might include a plan for next time identifying what you would do differently, your new understandings or values and unexpected things you have learnt about yourself.

You are aiming to draw out the links between theory and practice. So you will need to keep comparing the two and exploring the relationship between them.

Analyze the event and think about it with reference to a particular theory or academic evidence:

- Are your observations consistent with the theory, models or published academic evidence?

- How can the theories help you to interpret your experience?

- Also consider how your experience in practice helps you to understand the theories. Does it seem to bear out what the theories have predicted?

- Or is it quite different? If so, can you identify why it's different? (Perhaps you were operating in different circumstances from the original research, for instance.)

Collecting evidence

There are two sources of evidence which need to be used in reflective writing assignments:

1) Your reflections form essential evidence of your experiences. Keep notes on your reflections and the developments that have occurred during the process.

2) Academic evidence from published case studies and theories to show how your ideas and practices have developed in the context of the relevant academic literature.

1) Write a log of the event. Describe what happened as briefly and objectively as possible. You might be asked to include the log as an appendix to your assignment but it is mostly for your own benefit so that you can recall what occurred accurately.

2) Reflect . You should reflect upon the experience before you start to write, although additional insights are likely to emerge throughout the writing process. Discuss with a friend or colleague and develop your insight. Keep notes on your thinking.

3) Select . Identify relevant examples which illustrate the reflective process; choose a few of the most challenging or puzzling incidents and explore why they are interesting and what you have learnt from them.

Start with the points you want to make, then select examples to back up your points, from your two sources of evidence:

ii) theories, published case studies, or academic articles.

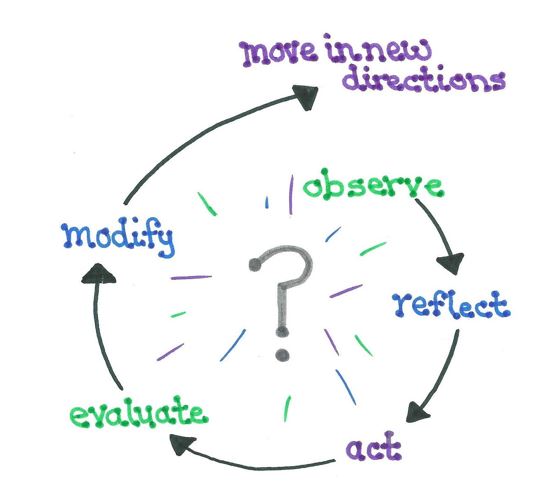

Use the reflective learning cycle to structure your writing:

- plan again etc.

This will make sure you cover the whole process and explain not just what happened, but why it happened and what improvements can be made based on your new understanding.

As a large proportion of your reflective account is based on your own experience, it is normally appropriate to use the first person ('I'). However, most assignments containing reflective writing will also include academic writing. You are therefore likely to need to write both in the first person ("I felt…") and in the third person ("Smith (2009) proposes that …"). Identify which parts of your experience you are being asked to reflect on and use this as a guide to when to use the first person. Always check your guidelines if you are not sure. If guidelines are not available then, in your introduction, explain when and why you are going to use "I" in your writing.

You will produce a balance by weaving together sections of 'I thought… 'I felt,…' and the relevant academic theories in the same section or paragraph. This is more effective than having a section which deals with the theory and a separate section dealing with your experiences.

Try to avoid emotive or subjective terms. Even though you are drawing on your experiences (and they may well have been emotional), you are trying to communicate these to your reader in an academic style. This means using descriptions that everyone would understand in the same way. So rather than writing, "The client was very unhappy at the start of the session", it might be better to write, "The client was visibly distressed", or "The client reported that he was very unhappy". This shows that you are aware that the client's understanding of 'unhappiness' may be quite different from yours or your reader's.

When writing about your reflections use the past tense as you are referring to a particular moment (I felt…). When referring to theory use the present tense as the ideas are still current (Smith proposes that...).

- << Previous: Reflective thinking

- Last Updated: Jan 29, 2024 11:24 AM

- URL: https://libguides.reading.ac.uk/reflective

Module 1: Success Skills

Reflective writing, learning objectives.

- Examine the components of reflective writing

Reflective writing includes several different components: description, analysis, interpretation, evaluation, and future application. Reflective writers must weave their personal perspectives with evidence of deep, critical thought as they make connections between theory, practice, and learning. The steps below should help you find the appropriate balance among all these factors.

1st Step: Review the assignment

As with any writing situation, the first step in writing a reflective piece is to clarify the task. Reflective assignments can take many forms, so you need to understand exactly what your instructor is asking you to do. Some reflective assignments are short, just a paragraph or two of unpolished writing. Usually the purpose of these reflective pieces is to capture your immediate impressions or perceptions. For example, your instructor might ask you at the end of a class to write quickly about a concept from that day’s lesson. That type of reflection helps you and your instructor gauge your understanding of the concept.

Other reflections are academic essays that can range in length from several paragraphs to several pages. The purpose of these essays is to critically reflect on and support an original claim(s) about a larger experience, such as an event you attended, a project you worked on, or your writing development. These essays require polished writing that conforms to academic conventions, such as articulation of a claim and substantive revision. They might address a larger audience than you and your instructor, including, for example, your classmates, your family, a scholarship committee, etc. It’s important before you begin writing, that you can identify the assignment’s purpose, audience, intended message or content, and requirements.

2nd Step: Generate ideas for content

As you generate ideas for your reflection, you might consider things like:

- Recollections of an experience, assignment, or course

- Ideas or observations made during that event

- Questions, challenges, or areas of doubt

- Strategies employed to solve problems

- A-ha moments linking theory to practice or learning something new

- Connections between this learning and prior learning

- New questions that arise as a result of the learning or experience

- New actions taken as a result of the learning or experience

3rd Step: Organize content

Researchers have developed several different frameworks or models for how reflective writing can be structured. For example, one method has you consider the “What?” “So what?” and “Now what?” of a situation in order to become more reflective. First, you assess what happened and describe the event, then you explain why it was significant, and then you use that information to inform your future practice. [1] [2] Similarly, the DIEP framework can help you consider how to organize your content when writing a reflective piece. Using this method, you describe what happened or what you did, interpret what it means, evaluate its value or impact, and plan steps for improving or changing for the future.

The DIEP Model of reflective writing

The DIEP model (Boud, Keogh & Walker, 1985) organizes the reflection into four different components:

Figure 1 . The DIEP model for reflective thinking and writing has you first describe the situation, interpret it, evaluate it, then plan what to do with that new information.

Remember, your goal is to make an interpretive or evaluative claim, or series of claims, that moves beyond obvious statements (such as, “I really enjoyed this project”) and demonstrates you have come to a deeper understanding of what you have learned and how you will use that learning.

In the example below, notice how the writer reflects on her initial ambitions and planning, the a-ha! moment, and then her decision to limit the scope of a project. She was assigned a multimodal (more than just writing) project, in which she made a video, and then reflected on the experience:

Student Example

Keeping a central focus in mind applies to multimodal compositions as well as written essays. A prime example of this was in my remix. When storyboarding for the video, I wanted to appeal to all college students in general. Within my compressed time limit of three minutes, I had planned to showcase numerous large points. It was too much. I decided to limit the scope of the topic to emphasize how digitally “addicted” college students are, and that really changed the project in significant ways.

4th Step: Draft, Revise, Edit, Repeat

A single, unpolished draft may suffice for short, in-the-moment reflections, but you may be asked to produce a longer academic reflection essay. This longer reflection will require significant drafting, revising, and editing. Whatever the length of the assignment, keep this reflective cycle in mind:

- briefly describe the event or action;

- analyze and interpret events and actions, using evidence for support;

- demonstrate relevance in the present and the future.

The following video, produced by the Hull University Skills Team, provides a great overview of reflective writing. Even if you aren’t assigned a specific reflection writing task in your classes, it’s a good idea to reflect anyway, as reflection results in better learning.

You can view the transcript for “Reflective Writing” here (opens in new window) .

Check your understanding of reflective writing and the things you learned in the video with these quick practice questions:

Contribute!

Improve this page Learn More

- Driscoll J (1994) Reflective practice for practise - a framework of structured reflection for clinical areas. Senior Nurse 14 (1):47–50 ↵

- Ash, S.L, Clayton, P.H., & Moses, M.G. (2009). Learning through critical reflection: A tutorial for service-learning students (instructor version). Raleigh, NC. ↵

- Process of Reflective Writing. Authored by : Karen Forgette. Provided by : University of Mississippi. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Reflective Writing. Provided by : SkillsTeamHullUni. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QoI67VeE3ds&feature=emb_logo . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Frameworks for Reflective Writing. Authored by : Karen Forgette. Provided by : University of Mississippi. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

TEP Guide: Reflective Writing

- Finding Resources

- Evaluating Information Sources

- Referencing

Reflective Writing

- TEP021 Foundations for Success

- TEP022 Academic Language and Learning

- TEP023 Foundation Maths

- TEP025 BioScience

- TEP026 Perspectives in Humanities

Reflective writing IS:

- documenting your response to experiences, opinions, events or new information

- communicating your response to thoughts and feelings

- a way of exploring your learning

- an opportunity to gain self-knowledge

- a way to achieve clarity and better understanding of what you are learning

- a chance to develop and reinforce writing skills

- a way of making meaning out of what you study

Reflective writing is NOT:

- just conveying information, instruction or argument

- pure description, though there may be descriptive elements

- straightforward decision or judgement, e.g. about whether something is right or wrong, good or bad

- simple problem-solving

- a summary of course notes

- a standard university essay.

(University of New South Wales, n.d.)

Types of Reflective Writing

A journal requires you to write weekly entries throughout a semester. May require you to base your reflection on course content.

A learning diary is similar to a journal, but may require group participation. The diary then becomes a place for you to communicate in writing with other group members.

A logbook is often used in disciplines based on experimental work, such as science. You note down or 'log' what you have done. A log gives you an accurate record of a process and helps you reflect on past actions and make better decisions for future actions.

A reflective note is often used in law. A reflective note encourages you to think about your personal reaction to a legal issue raised in a course.

An essay diary can take the form of an annotated bibliography (where you examine sources of evidence you might include in your essay) and a critique (where you reflect on your own writing and research processes).

A peer review usually involves students showing their work to their peers for feedback.

A self-assessment task requires you to comment on your own work.

Reflective Writing - YouTube Videos

How do I write reflectively using DIEP?

DIEP* is a strategy to help with writing a critical or academic reflection in four paragraphs. The four steps are to describe an insight (new understanding), to interpret and evaluate it, and to plan how it might transfer to future practice or learning. First, select an experience or insight to reflect on.

Then attempt to:

• analyse your learning and deepening understanding

• evaluate your successes in understanding and development, while keeping in mind any challenges