Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a rhetorical analysis | Key concepts & examples

How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis | Key Concepts & Examples

Published on August 28, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A rhetorical analysis is a type of essay that looks at a text in terms of rhetoric. This means it is less concerned with what the author is saying than with how they say it: their goals, techniques, and appeals to the audience.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Key concepts in rhetoric, analyzing the text, introducing your rhetorical analysis, the body: doing the analysis, concluding a rhetorical analysis, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about rhetorical analysis.

Rhetoric, the art of effective speaking and writing, is a subject that trains you to look at texts, arguments and speeches in terms of how they are designed to persuade the audience. This section introduces a few of the key concepts of this field.

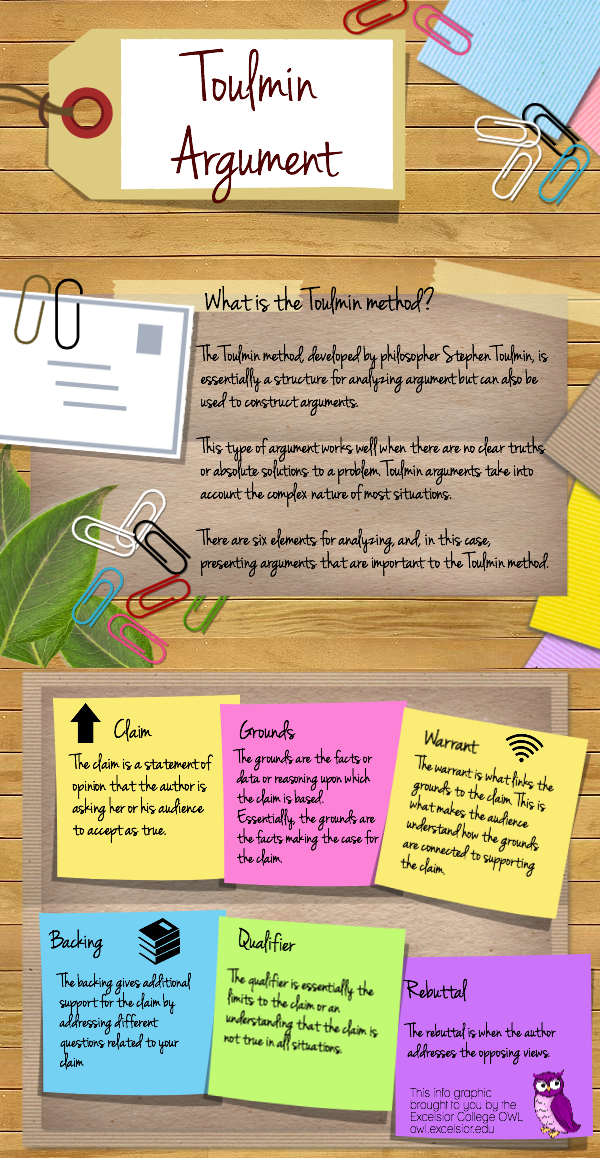

Appeals: Logos, ethos, pathos

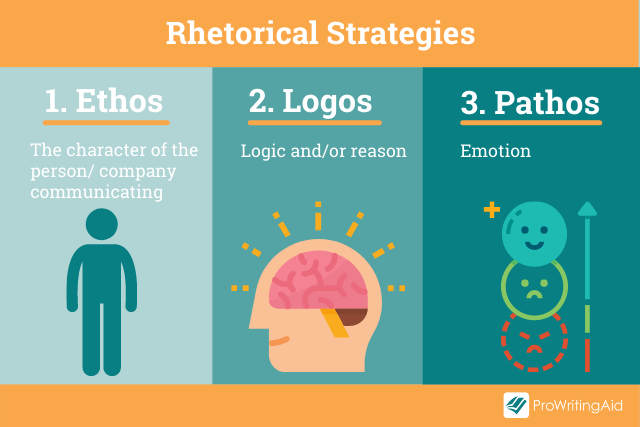

Appeals are how the author convinces their audience. Three central appeals are discussed in rhetoric, established by the philosopher Aristotle and sometimes called the rhetorical triangle: logos, ethos, and pathos.

Logos , or the logical appeal, refers to the use of reasoned argument to persuade. This is the dominant approach in academic writing , where arguments are built up using reasoning and evidence.

Ethos , or the ethical appeal, involves the author presenting themselves as an authority on their subject. For example, someone making a moral argument might highlight their own morally admirable behavior; someone speaking about a technical subject might present themselves as an expert by mentioning their qualifications.

Pathos , or the pathetic appeal, evokes the audience’s emotions. This might involve speaking in a passionate way, employing vivid imagery, or trying to provoke anger, sympathy, or any other emotional response in the audience.

These three appeals are all treated as integral parts of rhetoric, and a given author may combine all three of them to convince their audience.

Text and context

In rhetoric, a text is not necessarily a piece of writing (though it may be this). A text is whatever piece of communication you are analyzing. This could be, for example, a speech, an advertisement, or a satirical image.

In these cases, your analysis would focus on more than just language—you might look at visual or sonic elements of the text too.

The context is everything surrounding the text: Who is the author (or speaker, designer, etc.)? Who is their (intended or actual) audience? When and where was the text produced, and for what purpose?

Looking at the context can help to inform your rhetorical analysis. For example, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech has universal power, but the context of the civil rights movement is an important part of understanding why.

Claims, supports, and warrants

A piece of rhetoric is always making some sort of argument, whether it’s a very clearly defined and logical one (e.g. in a philosophy essay) or one that the reader has to infer (e.g. in a satirical article). These arguments are built up with claims, supports, and warrants.

A claim is the fact or idea the author wants to convince the reader of. An argument might center on a single claim, or be built up out of many. Claims are usually explicitly stated, but they may also just be implied in some kinds of text.

The author uses supports to back up each claim they make. These might range from hard evidence to emotional appeals—anything that is used to convince the reader to accept a claim.

The warrant is the logic or assumption that connects a support with a claim. Outside of quite formal argumentation, the warrant is often unstated—the author assumes their audience will understand the connection without it. But that doesn’t mean you can’t still explore the implicit warrant in these cases.

For example, look at the following statement:

We can see a claim and a support here, but the warrant is implicit. Here, the warrant is the assumption that more likeable candidates would have inspired greater turnout. We might be more or less convinced by the argument depending on whether we think this is a fair assumption.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Rhetorical analysis isn’t a matter of choosing concepts in advance and applying them to a text. Instead, it starts with looking at the text in detail and asking the appropriate questions about how it works:

- What is the author’s purpose?

- Do they focus closely on their key claims, or do they discuss various topics?

- What tone do they take—angry or sympathetic? Personal or authoritative? Formal or informal?

- Who seems to be the intended audience? Is this audience likely to be successfully reached and convinced?

- What kinds of evidence are presented?

By asking these questions, you’ll discover the various rhetorical devices the text uses. Don’t feel that you have to cram in every rhetorical term you know—focus on those that are most important to the text.

The following sections show how to write the different parts of a rhetorical analysis.

Like all essays, a rhetorical analysis begins with an introduction . The introduction tells readers what text you’ll be discussing, provides relevant background information, and presents your thesis statement .

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how an introduction works.

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech is widely regarded as one of the most important pieces of oratory in American history. Delivered in 1963 to thousands of civil rights activists outside the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., the speech has come to symbolize the spirit of the civil rights movement and even to function as a major part of the American national myth. This rhetorical analysis argues that King’s assumption of the prophetic voice, amplified by the historic size of his audience, creates a powerful sense of ethos that has retained its inspirational power over the years.

The body of your rhetorical analysis is where you’ll tackle the text directly. It’s often divided into three paragraphs, although it may be more in a longer essay.

Each paragraph should focus on a different element of the text, and they should all contribute to your overall argument for your thesis statement.

Hover over the example to explore how a typical body paragraph is constructed.

King’s speech is infused with prophetic language throughout. Even before the famous “dream” part of the speech, King’s language consistently strikes a prophetic tone. He refers to the Lincoln Memorial as a “hallowed spot” and speaks of rising “from the dark and desolate valley of segregation” to “make justice a reality for all of God’s children.” The assumption of this prophetic voice constitutes the text’s strongest ethical appeal; after linking himself with political figures like Lincoln and the Founding Fathers, King’s ethos adopts a distinctly religious tone, recalling Biblical prophets and preachers of change from across history. This adds significant force to his words; standing before an audience of hundreds of thousands, he states not just what the future should be, but what it will be: “The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.” This warning is almost apocalyptic in tone, though it concludes with the positive image of the “bright day of justice.” The power of King’s rhetoric thus stems not only from the pathos of his vision of a brighter future, but from the ethos of the prophetic voice he adopts in expressing this vision.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

The conclusion of a rhetorical analysis wraps up the essay by restating the main argument and showing how it has been developed by your analysis. It may also try to link the text, and your analysis of it, with broader concerns.

Explore the example below to get a sense of the conclusion.

It is clear from this analysis that the effectiveness of King’s rhetoric stems less from the pathetic appeal of his utopian “dream” than it does from the ethos he carefully constructs to give force to his statements. By framing contemporary upheavals as part of a prophecy whose fulfillment will result in the better future he imagines, King ensures not only the effectiveness of his words in the moment but their continuing resonance today. Even if we have not yet achieved King’s dream, we cannot deny the role his words played in setting us on the path toward it.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

The goal of a rhetorical analysis is to explain the effect a piece of writing or oratory has on its audience, how successful it is, and the devices and appeals it uses to achieve its goals.

Unlike a standard argumentative essay , it’s less about taking a position on the arguments presented, and more about exploring how they are constructed.

The term “text” in a rhetorical analysis essay refers to whatever object you’re analyzing. It’s frequently a piece of writing or a speech, but it doesn’t have to be. For example, you could also treat an advertisement or political cartoon as a text.

Logos appeals to the audience’s reason, building up logical arguments . Ethos appeals to the speaker’s status or authority, making the audience more likely to trust them. Pathos appeals to the emotions, trying to make the audience feel angry or sympathetic, for example.

Collectively, these three appeals are sometimes called the rhetorical triangle . They are central to rhetorical analysis , though a piece of rhetoric might not necessarily use all of them.

In rhetorical analysis , a claim is something the author wants the audience to believe. A support is the evidence or appeal they use to convince the reader to believe the claim. A warrant is the (often implicit) assumption that links the support with the claim.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis | Key Concepts & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/rhetorical-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an argumentative essay | examples & tips, how to write a literary analysis essay | a step-by-step guide, comparing and contrasting in an essay | tips & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2 Rhetorical Analysis

Elizabeth Browning

For many people, particularly those in the media, the term “rhetoric ” has a largely negative connotation. A political commentator, for example, may say that a politician is using “empty rhetoric” or that what that politician says is “just a bunch of rhetoric.” What the commentator means is that the politician’s words are lacking substance, that the purpose of those words is more about manipulation rather than meaningfulness. However, this flawed definition, though quite common these days, does not offer the entire picture or full understanding of a concept that is more about clearly expressing substance and meaning rather than avoiding them.

This chapter will clarify what rhetorical analysis means and will help you identify the basic elements of rhetorical analysis through explanation and example .

1. What is rhetorical analysis?

2. What is rhetorical situation?

3. What are the basic elements of rhetorical analysis?

3.1 The appeal to ethos.

3.2 The appeal the pathos.

3.3 The appeal to logos.

3.4 The appeal to kairos.

4. Striking a balance?

1. What is rhetorical analysis?

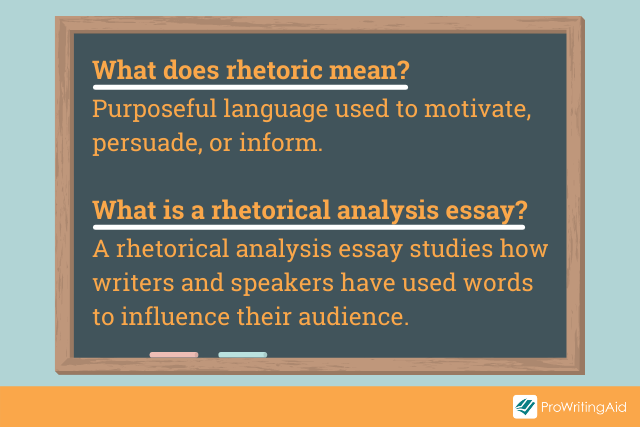

Simply defined, rhetoric is the art or method of communicating effectively to an audience, usually with the intention to persuade; thus, rhetorical analysis means analyzing how effectively a writer or speaker communicates her message or argument to the audience.

The ancient Greeks, namely Aristotle, developed rhetoric into an art form, which explains why much of the terminology that we use for rhetoric comes from Greek. The three major parts of effective communication, also called the Rhetorical Triangle , are ethos , patho s, and logos , and they provide the foundation for a solid argument. As a reader and a listener, you must be able to recognize how writers and speakers depend upon these three rhetorical elements in their efforts to communicate. As a communicator yourself, you will benefit from the ability to see how others rely upon ethos, pathos, and logos so that you can apply what you learn from your observations to your own speaking and writing.

Rhetorical analysis can evaluate and analyze any type of communicator, whether that be a speaker, an artist, an advertiser, or a writer, but to simplify the language in this chapter, the term “writer” will represent the role of the communicator.

2. What is a rhetorical situation?

Essentially, understanding a rhetorical situation means understanding the context of that situation. A rhetorical situation comprises a handful of key elements, which should be identified before attempting to analyze and evaluate the use of rhetorical appeals. These elements consist of the communicator in the situation (such as the writer), the issue at hand (the topic or problem being addressed), the purpose for addressing the issue, the medium of delivery (e.g.–speech, written text, a commercial), and the audience being addressed.

Answering the following questions will help you identify a rhetorical situation :

- Who is the communicator or writer?

- What is the main argument that the writer is making?

- To provoke, to attack, or to defend?

- To push toward or dissuade from certain action?

- To praise or to blame?

- To teach, to delight, or to persuade?

- What is the structure of the communication; how is it arranged?

- What oral or literary genre is it?

- What figures of speech (schemes and tropes) are used?

- What kind of style and tone is used and for what purpose?

- Does the form complement the content?

- What effect could the form have, and does this aid or hinder the author’s intention?

- Who is the intended audience?

- What values does the audience hold that the author or speaker appeals to?

- Who have been or might be secondary audiences?

- If this is a work of fiction, what is the nature of the audience within the fiction?

Figure 2.1 A Balanced Argument

3. What are the basic elements of rhetorical analysis?

3.1 the appeal to ethos.

Literally translated, ethos means “character.” In this case, it refers to the character of the writer or speaker, or more specifically, his credibility. The writer needs to establish credibility so that the audience will trust him and, thus, be more willing to engage with the argument. If a writer fails to establish a sufficient ethical appeal , then the audience will not take the writer’s argument seriously.

For example, if someone writes an article that is published in an academic journal, in a reputable newspaper or magazine, or on a credible website, those places of publication already imply a certain level of credibility. If the article is about a scientific issue and the writer is a scientist or has certain academic or professional credentials that relate to the article’s subject, that also will lend credibility to the writer. Finally, if that writer shows that he is knowledgeable about the subject by providing clear explanations of points and by presenting information in an honest and straightforward way that also helps to establish a writer’s credibility.

When evaluating a writer’s ethical appeal , ask the following questions:

Does the writer come across as reliable?

- Viewpoint is logically consistent throughout the text

- Does not use hyperbolic (exaggerated) language

- Has an even, objective tone (not malicious but also not sycophantic)

- Does not come across as subversive or manipulative

Does the writer come across as authoritative and knowledgeable?

- Explains concepts and ideas thoroughly

- Addresses any counter-arguments and successfully rebuts them

- Uses a sufficient number of relevant sources

- Shows an understanding of sources used

What kind of credentials or experience does the writer have?

- Look at byline or biographical info

- Identify any personal or professional experience mentioned in the text

- Where has this writer’s text been published?

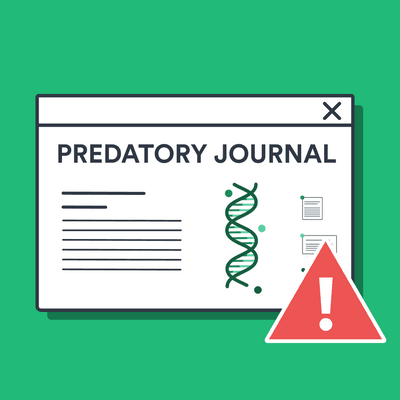

Recognizing a Manipulative Appeal to Ethos:

In a perfect world, everyone would tell the truth, and we could depend upon the credibility of speakers and authors. Unfortunately, that is not always the case. You would expect that news reporters would be objective and tell news stories based upon the facts; however, Janet Cooke, Stephen Glass, Jayson Blair, and Brian Williams all lost their jobs for plagiarizing or fabricating part of their news stories. Janet Cooke’s Pulitzer Prize was revoked after it was discovered that she made up “Jimmy,” an eight-year old heroin addict ( Prince, 2010 ). Brian Williams was fired as anchor of the NBC Nightly News for exaggerating his role in the Iraq War.

Others have become infamous for claiming academic degrees that they didn’t earn as in the case of Marilee Jones. At the time of discovery, she was Dean of Admissions at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). After 28 years of employment, it was determined that she never graduated from college ( Lewin, 2007 ). However, on her website (http://www.marileejones.com/blog/) she is still promoting herself as “a sought after speaker, consultant and author” and “one of the nation’s most experienced College Admissions Deans.”

Beyond lying about their own credentials, authors may employ a number of tricks or fallacies to lure you to their point of view. Some of the more common techniques are described in the next chapter . When you recognize these fallacies, you should question the credibility of the speaker and the legitimacy of the argument. If you use these when making your own arguments, be aware that they may undermine or even destroy your credibility.

Exercise 1: Analyzing Ethos

Choose an article from the links provided below. Preview your chosen text, and then read through it, paying special attention to how the writer tries to establish an ethical appeal. Once you have finished reading, use the bullet points above to guide you in analyzing how effective the writer’s appeal to ethos is.

“Why cancer is not a war, fight, or battle ” by Xeni Jordan (https://tinyurl.com/y7m7bnnm)

“Relax and Let Your Kids Indulge in TV” by Lisa Pryor (https://tinyurl.com/y88epytu)

“Why are we OK with disability drag in Hollywood?” by Danny Woodburn and Jay Ruderman (https://tinyurl.com/y964525k)

3.2 The appeal to pathos

Literally translated, pathos means “suffering.” In this case, it refers to emotion, or more specifically, the writer’s appeal to the audience’s emotions. When a writer establishes an effective pathetic appeal , she makes the audience care about what she is saying. If the audience does not care about the message, then they will not engage with the argument being made.

For example, consider this: A writer is crafting a speech for a politician who is running for office, and in it, the writer raises a point about Social Security benefits. In order to make this point more appealing to the audience so that they will feel more emotionally connected to what the politician says, the writer inserts a story about Mary, an 80-year-old widow who relies on her Social Security benefits to supplement her income. While visiting Mary the other day, sitting at her kitchen table and eating a piece of her delicious homemade apple pie, the writer recounts how the politician held Mary’s delicate hand and promised that her benefits would be safe if he were elected. Ideally, the writer wants the audience to feel sympathy or compassion for Mary because then they will feel more open to considering the politician’s views on Social Security (and maybe even other issues).

When evaluating a writer’s pathetic appeal , ask the following questions:

Does the writer try to engage or connect with the audience by making the subject matter relatable in some way?

- Does the writer have an interesting writing style?

- Does the writer use humor at any point?

- Does the writer use narration , such as storytelling or anecdotes, to add interest or to help humanize a certain issue within the text?

- Does the writer use descriptive or attention-grabbing details?

- Are there hypothetical examples that help the audience to imagine themselves in certain scenarios?

- Does the writer use any other examples in the text that might emotionally appeal to the audience?

- Are there any visual appeals to pathos, such as photographs or illustrations?

Recognizing a Manipulative Appeal to Pathos:

Up to a certain point, an appeal to pathos can be a legitimate part of an argument. For example, a writer or speaker may begin with an anecdote showing the effect of a law on an individual. This anecdote is a way to gain an audience’s attention for an argument in which evidence and reason are used to present a case as to why the law should or should not be repealed or amended. In such a context, engaging the emotions, values, or beliefs of the audience is a legitimate and effective tool that makes the argument stronger.

An appropriate appeal to pathos is different from trying to unfairly play upon the audience’s feelings and emotions through fallacious, misleading, or excessively emotional appeals. Such a manipulative use of pathos may alienate the audience or cause them to “tune out.” An example would be the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) commercials (https://youtu.be/6eXfvRcllV8, transcript here ) featuring the song “In the Arms of an Angel” and footage of abused animals. Even Sarah McLachlan, the singer and spokesperson featured in the commercials, admits that she changes the channel because they are too depressing (Brekke).

Even if an appeal to pathos is not manipulative, such an appeal should complement rather than replace reason and evidence-based argument. In addition to making use of pathos, the author must establish her credibility ( ethos ) and must supply reasons and evidence ( logos ) in support of her position. An author who essentially replaces logos and ethos with pathos alone does not present a strong argument.

Exercise 2: Analyzing Pathos

In the movie Braveheart , the Scottish military leader, William Wallace, played by Mel Gibson, gives a speech to his troops just before they get ready to go into battle against the English army of King Edward I.

See clip here (https://youtu.be/h2vW-rr9ibE, transcript here ). See clip with closed captioning here .

Step 1 : When you watch the movie clip, try to gauge the general emotional atmosphere. Do the men seem calm or nervous? Confident or skeptical? Are they eager to go into battle, or are they ready to retreat? Assessing the situation from the start will make it easier to answer more specific, probing rhetorical questions after watching it.

Step 2 : Consider these questions:

- What issues does Wallace address?

- Who is his audience?

- How does the audience view the issues at hand?

Step 3 : Next, analyze Wallace’s use of pathos in his speech.

- How does he try to connect with his audience emotionally? Because this is a speech, and he’s appealing to the audience in person, consider his overall look as well as what he says.

- How would you describe his manner or attitude?

- Does he use any humor, and if so, to what effect?

- How would you describe his tone?

- Identify some examples of language that show an appeal to pathos: words, phrases, imagery, collective pronouns (we, us, our).

- How do all of these factors help him establish a pathetic appeal?

Step 4 : Once you’ve identified the various ways that Wallace tries to establish his appeal to pathos, the final step is to evaluate the effectiveness of that appeal.

- Do you think he has successfully established a pathetic appeal? Why or why not?

- What does he do well in establishing pathos?

- What could he improve, or what could he do differently to make his pathetic appeal even stronger?

3.3 The appeal to logos

Literally translated, logos means “word.” In this case, it refers to information, or more specifically, the writer’s appeal to logic and reason. A successful logical appeal provides clearly organized information as well as evidence to support the overall argument. If one fails to establish a logical appeal, then the argument will lack both sense and substance.

For example, refer to the previous example of the politician’s speech writer to understand the importance of having a solid logical appeal. What if the writer had only included the story about 80-year-old Mary without providing any statistics, data, or concrete plans for how the politician proposed to protect Social Security benefits? Without any factual evidence for the proposed plan, the audience would not have been as likely to accept his proposal, and rightly so.

When evaluating a writer’s logical appeal , ask the following questions:

Does the writer organize his information clearly?

- Choose the link for examples of common transitions (https://tinyurl.com/oftaj5g).

- Ideas have a clear and purposeful order

Does the writer provide evidence to back his claims?

- Specific examples

- Relevant source material

Does the writer use sources and data to back his claims rather than base the argument purely on emotion or opinion?

- Does the writer use concrete facts and figures, statistics, dates/times, specific names/titles, graphs/charts/tables?

- Are the sources that the writer uses credible?

- Where do the sources come from? (Who wrote/published them?)

- When were the sources published?

- Are the sources well-known, respected, and/or peer-reviewed (if applicable) publications?

Recognizing a Manipulative Appeal to Logos:

Pay particular attention to numbers, statistics, findings, and quotes used to support an argument. Be critical of the source and do your own investigation of the facts. Remember: What initially looks like a fact may not actually be one. Maybe you’ve heard or read that half of all marriages in America will end in divorce. It is so often discussed that we assume it must be true. Careful research will show that the original marriage study was flawed, and divorce rates in America have steadily declined since 1985 (Peck, 1993). If there is no scientific evidence, why do we continue to believe it? Part of the reason might be that it supports the common worry of the dissolution of the American family.

Fallacies that misuse appeals to logos or attempt to manipulate the logic of an argument are discussed in the next chapter .

Exercise 3: Analyzing Logos

The debate about whether college athletes, namely male football and basketball players, should be paid salaries instead of awarded scholarships is one that regularly comes up when these players are in the throes of their respective athletic seasons, whether that’s football bowl games or March Madness. While proponents on each side of this issue have solid reasons, you are going to look at an article that is against the idea of college athletes being paid.

Take note : Your aim in this rhetorical exercise is not to figure out where you stand on this issue; rather, your aim is to evaluate how effectively the writer establishes a logical appeal to support his position, whether you agree with him or not.

See the article here (https://time.com/5558498/ncaa-march-madness-pay-athletes/).

Step 1 : Before reading the article, take a minute to preview the text, a critical reading skill explained in Chapter 1 .

Step 2 : Once you have a general idea of the article, read through it and pay attention to how the author organizes information and uses evidence, annotating or marking these instances when you see them.

Step 3 : After reviewing your annotations, evaluate the organization of the article as well as the amount and types of evidence that you have identified by answering the following questions:

- Does the writer use transitions to link ideas?

- Do ideas in the article have a clear sense of order, or do they appear scattered and unfocused?

- Was there too little of it, was there just enough, or was there an overload of evidence?

- Were the examples of evidence relevant to the writer’s argument?

- Were the examples clearly explained?

- Were sources cited or clearly referenced?

- Were the sources credible? How could you tell?

3.4 The Appeal to Kairos

Literally translated, Kairos means the “supreme moment.” In this case, it refers to appropriate timing, meaning when the writer presents certain parts of her argument as well as the overall timing of the subject matter itself. While not technically part of the Rhetorical Triangle, it is still an important principle for constructing an effective argument. If the writer fails to establish a strong Kairotic appeal , then the audience may become polarized, hostile, or may simply just lose interest.

If appropriate timing is not taken into consideration and a writer introduces a sensitive or important point too early or too late in a text, the impact of that point could be lost on the audience. For example, if the writer’s audience is strongly opposed to her view, and she begins the argument with a forceful thesis of why she is right and the opposition is wrong, how do you think that audience might respond?

In this instance, the writer may have just lost the ability to make any further appeals to her audience in two ways: first, by polarizing them, and second, by possibly elevating what was at first merely strong opposition to what would now be hostile opposition. A polarized or hostile audience will not be inclined to listen to the writer’s argument with an open mind or even to listen at all. On the other hand, the writer could have established a stronger appeal to Kairos by building up to that forceful thesis, maybe by providing some neutral points such as background information or by addressing some of the opposition’s views, rather than leading with why she is right and the audience is wrong.

Additionally, if a writer covers a topic or puts forth an argument about a subject that is currently a non-issue or has no relevance for the audience, then the audience will fail to engage because whatever the writer’s message happens to be, it won’t matter to anyone. For example, if a writer were to put forth the argument that women in the United States should have the right to vote, no one would care; that is a non-issue because women in the United States already have that right.

When evaluating a writer’s Kairotic appeal , ask the following questions:

- Where does the writer establish her thesis of the argument in the text? Is it near the beginning, the middle, or the end? Is this placement of the thesis effective? Why or why not?

- Where in the text does the writer provide her strongest points of evidence? Does that location provide the most impact for those points?

- Is the issue that the writer raises relevant at this time, or is it something no one really cares about anymore or needs to know about anymore?

Exercise 4: Analyzing Kairos

In this exercise, you will analyze a visual representation of the appeal to Kairos. On the 26 th of February 2015, a photo of a dress was posted to Twitter along with a question as to whether people thought it was one combination of colors versus another. Internet chaos ensued on social media because while some people saw the dress as black and blue, others saw it as white and gold. As the color debate surrounding the dress raged on, an ad agency in South Africa saw an opportunity to raise awareness about a far more serious subject: domestic abuse.

Step 1 : Read this article (https://tinyurl.com/yctl8o5g) from CNN about how and why the photo of the dress went viral so that you will be better informed for the next step in this exercise:

Step 2 : Watch the video (https://youtu.be/SLv0ZRPssTI, transcript here )from CNN that explains how, in partnership with The Salvation Army, the South African marketing agency created an ad that went viral.

Step 3 : After watching the video, answer the following questions:

- Once the photo of the dress went viral, approximately how long after did the Salvation Army’s ad appear? Look at the dates on both the article and the video to get an idea of a time frame.

- How does the ad take advantage of the publicity surrounding the dress?

- Would the ad’s overall effectiveness change if it had come out later than it did?

- How late would have been too late to make an impact? Why?

4. Striking a Balance:

Figure 2.3 An Unbalanced Argument

The foundations of rhetoric are interconnected in such a way that a writer needs to establish all of the rhetorical appeals to put forth an effective argument. If a writer lacks a pathetic appeal and only tries to establish a logical appeal, the audience will be unable to connect emotionally with the writer and, therefore, will care less about the overall argument. Likewise, if a writer lacks a logical appeal and tries to rely solely on subjective or emotionally driven examples, then the audience will not take the writer seriously because an argument based purely on opinion and emotion cannot hold up without facts and evidence to support it. If a writer lacks either the pathetic or logical appeal, not to mention the kairotic appeal, then the writer’s ethical appeal will suffer. All of the appeals must be sufficiently established for a writer to communicate effectively with his audience.

For a visual example, watch (https://tinyurl.com/yct5zryn, transcript here ) violinist Joshua Bell show how the rhetorical situation determines the effectiveness of all types of communication, even music.

Exercise 5: Rhetorical Analysis

Step 1 : Choose one of the articles linked below.

Step 2 : Preview your chosen text, and then read and annotate it.

Step 3 : Next, using the information and steps outlined in this chapter, identify the rhetorical situation in the text based off of the following components: the communicator, the issue at hand, the purpose, the medium of delivery, and the intended audience.

Step 4 : Then, identify and analyze how the writer tries to establish the rhetorical appeals of ethos, pathos, logos, and Kairos throughout that text.

Step 5 : Finally, evaluate how effectively you think the writer establishes the rhetorical appeals, and defend your evaluation by noting specific examples that you’ve annotated.

BBC News , “ Taylor Swift Sexual Assault Case: Why is it significant ? ” (https://tinyurl.com/ybopmmdu)

NPR , “ Does Cash Aid Help the Poor–Or Encourage Laziness ? ” (https://tinyurl.com/y8ho2fhw)

Key Takeaways

Understanding the Rhetorical Situation:

- Identify who the communicator is.

- Identify the issue at hand.

- Identify the communicator’s purpose.

- Identify the medium or method of communication.

- Identify who the audience is.

Identifying the Rhetorical Appeals:

- Ethos = the writer’s credibility

- Pathos = the writer’s emotional appeal to the audience

- Logos = the writer’s logical appeal to the audience

- Kairos = appropriate and relevant timing of subject matter

- In sum, effective communication is based on an understanding of the rhetorical situation and on a balance of the rhetorical appeals.

CC Licensed Content, Shared Previously

English Composition I , Lumen Learning, CC-BY 4.0.

English Composition II , Lumen Learning, CC-BY 4.0.

Image Credits

Figure 2.1 “A Balanced Argument,” Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0.

Figure 2.2, “ Brian Williams at the 2011 Time 100 Gala ,” David Shankbone, Wikimedia, CC-BY 3.0.

Figure 2.3 “An Unbalanced Argument,” Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0.

Brekke, Kira. “ Sarah McLachlan: ‘I Change The Channel’ When My ASPCA Commercials Come On .” Huffington Post . 5 May 2014.

Lewin, Tamar. “ Dean at M.I.T. Resigns, Ending a 28-Year Lie .” New York Times . 27 April 2007, p. A1,

Peck, Dennis, L. “The Fifty Percent Divorce Rate: Deconstructing a Myth.” The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare . Vol. 20, no.3, 1993, pp. 135-144.

Prince, Richard. “ Janet Cooke’s Hoax Still Resonates After 30 Years .” The Root . October 2010.

Rhetorical Analysis Copyright © 2021 by Elizabeth Browning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Get 25% OFF new yearly plans in our Spring Sale

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

What Is a Rhetorical Analysis and How to Write a Great One

Helly Douglas

Do you have to write a rhetorical analysis essay? Fear not! We’re here to explain exactly what rhetorical analysis means, how you should structure your essay, and give you some essential “dos and don’ts.”

What is a Rhetorical Analysis Essay?

How do you write a rhetorical analysis, what are the three rhetorical strategies, what are the five rhetorical situations, how to plan a rhetorical analysis essay, creating a rhetorical analysis essay, examples of great rhetorical analysis essays, final thoughts.

A rhetorical analysis essay studies how writers and speakers have used words to influence their audience. Think less about the words the author has used and more about the techniques they employ, their goals, and the effect this has on the audience.

In your analysis essay, you break a piece of text (including cartoons, adverts, and speeches) into sections and explain how each part works to persuade, inform, or entertain. You’ll explore the effectiveness of the techniques used, how the argument has been constructed, and give examples from the text.

A strong rhetorical analysis evaluates a text rather than just describes the techniques used. You don’t include whether you personally agree or disagree with the argument.

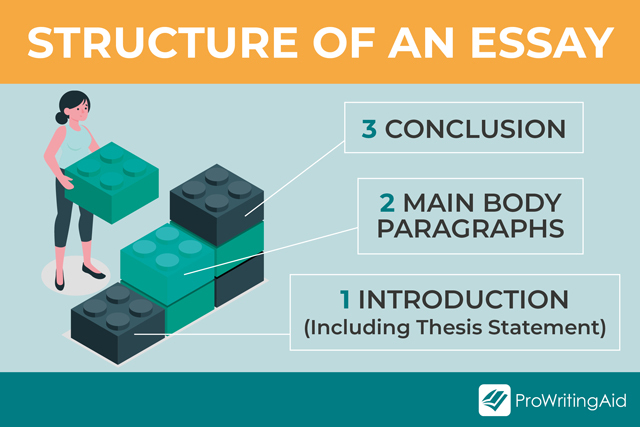

Structure a rhetorical analysis in the same way as most other types of academic essays . You’ll have an introduction to present your thesis, a main body where you analyze the text, which then leads to a conclusion.

Think about how the writer (also known as a rhetor) considers the situation that frames their communication:

- Topic: the overall purpose of the rhetoric

- Audience: this includes primary, secondary, and tertiary audiences

- Purpose: there are often more than one to consider

- Context and culture: the wider situation within which the rhetoric is placed

Back in the 4th century BC, Aristotle was talking about how language can be used as a means of persuasion. He described three principal forms —Ethos, Logos, and Pathos—often referred to as the Rhetorical Triangle . These persuasive techniques are still used today.

Rhetorical Strategy 1: Ethos

Are you more likely to buy a car from an established company that’s been an important part of your community for 50 years, or someone new who just started their business?

Reputation matters. Ethos explores how the character, disposition, and fundamental values of the author create appeal, along with their expertise and knowledge in the subject area.

Aristotle breaks ethos down into three further categories:

- Phronesis: skills and practical wisdom

- Arete: virtue

- Eunoia: goodwill towards the audience

Ethos-driven speeches and text rely on the reputation of the author. In your analysis, you can look at how the writer establishes ethos through both direct and indirect means.

Rhetorical Strategy 2: Pathos

Pathos-driven rhetoric hooks into our emotions. You’ll often see it used in advertisements, particularly by charities wanting you to donate money towards an appeal.

Common use of pathos includes:

- Vivid description so the reader can imagine themselves in the situation

- Personal stories to create feelings of empathy

- Emotional vocabulary that evokes a response

By using pathos to make the audience feel a particular emotion, the author can persuade them that the argument they’re making is compelling.

Rhetorical Strategy 3: Logos

Logos uses logic or reason. It’s commonly used in academic writing when arguments are created using evidence and reasoning rather than an emotional response. It’s constructed in a step-by-step approach that builds methodically to create a powerful effect upon the reader.

Rhetoric can use any one of these three techniques, but effective arguments often appeal to all three elements.

The rhetorical situation explains the circumstances behind and around a piece of rhetoric. It helps you think about why a text exists, its purpose, and how it’s carried out.

The rhetorical situations are:

- 1) Purpose: Why is this being written? (It could be trying to inform, persuade, instruct, or entertain.)

- 2) Audience: Which groups or individuals will read and take action (or have done so in the past)?

- 3) Genre: What type of writing is this?

- 4) Stance: What is the tone of the text? What position are they taking?

- 5) Media/Visuals: What means of communication are used?

Understanding and analyzing the rhetorical situation is essential for building a strong essay. Also think about any rhetoric restraints on the text, such as beliefs, attitudes, and traditions that could affect the author's decisions.

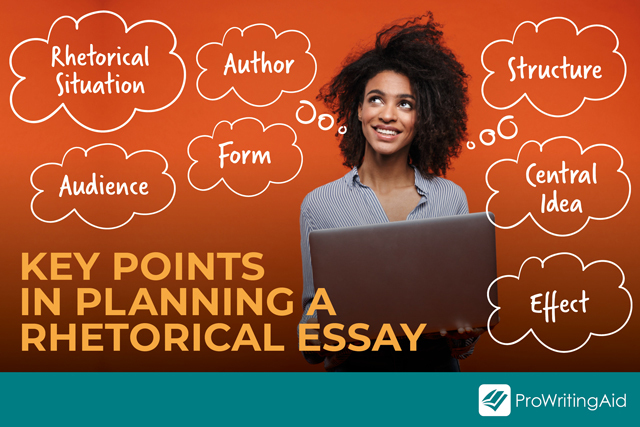

Before leaping into your essay, it’s worth taking time to explore the text at a deeper level and considering the rhetorical situations we looked at before. Throw away your assumptions and use these simple questions to help you unpick how and why the text is having an effect on the audience.

1: What is the Rhetorical Situation?

- Why is there a need or opportunity for persuasion?

- How do words and references help you identify the time and location?

- What are the rhetoric restraints?

- What historical occasions would lead to this text being created?

2: Who is the Author?

- How do they position themselves as an expert worth listening to?

- What is their ethos?

- Do they have a reputation that gives them authority?

- What is their intention?

- What values or customs do they have?

3: Who is it Written For?

- Who is the intended audience?

- How is this appealing to this particular audience?

- Who are the possible secondary and tertiary audiences?

4: What is the Central Idea?

- Can you summarize the key point of this rhetoric?

- What arguments are used?

- How has it developed a line of reasoning?

5: How is it Structured?

- What structure is used?

- How is the content arranged within the structure?

6: What Form is Used?

- Does this follow a specific literary genre?

- What type of style and tone is used, and why is this?

- Does the form used complement the content?

- What effect could this form have on the audience?

7: Is the Rhetoric Effective?

- Does the content fulfil the author’s intentions?

- Does the message effectively fit the audience, location, and time period?

Once you’ve fully explored the text, you’ll have a better understanding of the impact it’s having on the audience and feel more confident about writing your essay outline.

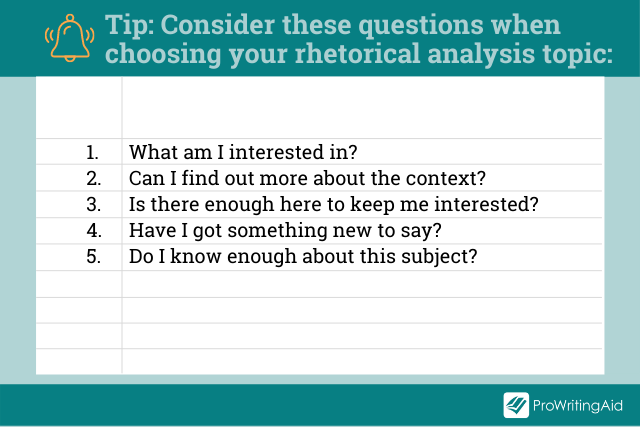

A great essay starts with an interesting topic. Choose carefully so you’re personally invested in the subject and familiar with it rather than just following trending topics. There are lots of great ideas on this blog post by My Perfect Words if you need some inspiration. Take some time to do background research to ensure your topic offers good analysis opportunities.

Remember to check the information given to you by your professor so you follow their preferred style guidelines. This outline example gives you a general idea of a format to follow, but there will likely be specific requests about layout and content in your course handbook. It’s always worth asking your institution if you’re unsure.

Make notes for each section of your essay before you write. This makes it easy for you to write a well-structured text that flows naturally to a conclusion. You will develop each note into a paragraph. Look at this example by College Essay for useful ideas about the structure.

1: Introduction

This is a short, informative section that shows you understand the purpose of the text. It tempts the reader to find out more by mentioning what will come in the main body of your essay.

- Name the author of the text and the title of their work followed by the date in parentheses

- Use a verb to describe what the author does, e.g. “implies,” “asserts,” or “claims”

- Briefly summarize the text in your own words

- Mention the persuasive techniques used by the rhetor and its effect

Create a thesis statement to come at the end of your introduction.

After your introduction, move on to your critical analysis. This is the principal part of your essay.

- Explain the methods used by the author to inform, entertain, and/or persuade the audience using Aristotle's rhetorical triangle

- Use quotations to prove the statements you make

- Explain why the writer used this approach and how successful it is

- Consider how it makes the audience feel and react

Make each strategy a new paragraph rather than cramming them together, and always use proper citations. Check back to your course handbook if you’re unsure which citation style is preferred.

3: Conclusion

Your conclusion should summarize the points you’ve made in the main body of your essay. While you will draw the points together, this is not the place to introduce new information you’ve not previously mentioned.

Use your last sentence to share a powerful concluding statement that talks about the impact the text has on the audience(s) and wider society. How have its strategies helped to shape history?

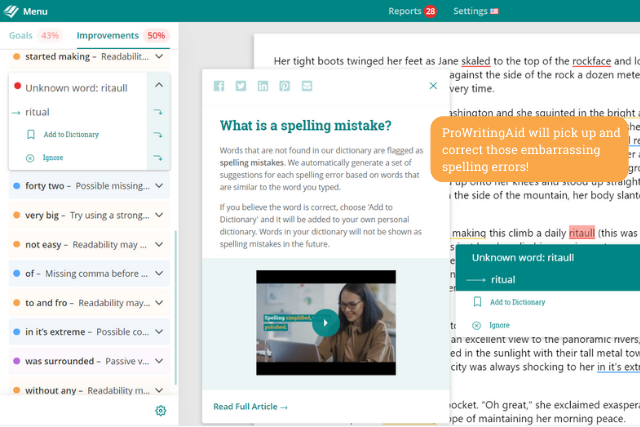

Before You Submit

Poor spelling and grammatical errors ruin a great essay. Use ProWritingAid to check through your finished essay before you submit. It will pick up all the minor errors you’ve missed and help you give your essay a final polish. Look at this useful ProWritingAid webinar for further ideas to help you significantly improve your essays. Sign up for a free trial today and start editing your essays!

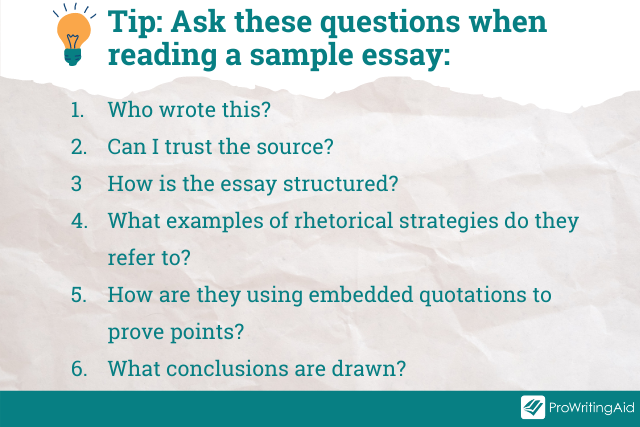

You’ll find countless examples of rhetorical analysis online, but they range widely in quality. Your institution may have example essays they can share with you to show you exactly what they’re looking for.

The following links should give you a good starting point if you’re looking for ideas:

Pearson Canada has a range of good examples. Look at how embedded quotations are used to prove the points being made. The end questions help you unpick how successful each essay is.

Excelsior College has an excellent sample essay complete with useful comments highlighting the techniques used.

Brighton Online has a selection of interesting essays to look at. In this specific example, consider how wider reading has deepened the exploration of the text.

Writing a rhetorical analysis essay can seem daunting, but spending significant time deeply analyzing the text before you write will make it far more achievable and result in a better-quality essay overall.

It can take some time to write a good essay. Aim to complete it well before the deadline so you don’t feel rushed. Use ProWritingAid’s comprehensive checks to find any errors and make changes to improve readability. Then you’ll be ready to submit your finished essay, knowing it’s as good as you can possibly make it.

Try ProWritingAid's Editor for Yourself

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Helly Douglas is a UK writer and teacher, specialising in education, children, and parenting. She loves making the complex seem simple through blogs, articles, and curriculum content. You can check out her work at hellydouglas.com or connect on Twitter @hellydouglas. When she’s not writing, you will find her in a classroom, being a mum or battling against the wilderness of her garden—the garden is winning!

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a rhetorical analysis

What is a rhetorical analysis?

What are the key concepts of a rhetorical analysis, rhetorical situation, claims, supports, and warrants.

- Step 1: Plan and prepare

- Step 2: Write your introduction

- Step 3: Write the body

- Step 4: Write your conclusion

Frequently Asked Questions about rhetorical analysis

Related articles.

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion and aims to study writers’ or speakers' techniques to inform, persuade, or motivate their audience. Thus, a rhetorical analysis aims to explore the goals and motivations of an author, the techniques they’ve used to reach their audience, and how successful these techniques were.

This will generally involve analyzing a specific text and considering the following aspects to connect the rhetorical situation to the text:

- Does the author successfully support the thesis or claims made in the text? Here, you’ll analyze whether the author holds to their argument consistently throughout the text or whether they wander off-topic at some point.

- Does the author use evidence effectively considering the text’s intended audience? Here, you’ll consider the evidence used by the author to support their claims and whether the evidence resonates with the intended audience.

- What rhetorical strategies the author uses to achieve their goals. Here, you’ll consider the word choices by the author and whether these word choices align with their agenda for the text.

- The tone of the piece. Here, you’ll consider the tone used by the author in writing the piece by looking at specific words and aspects that set the tone.

- Whether the author is objective or trying to convince the audience of a particular viewpoint. When it comes to objectivity, you’ll consider whether the author is objective or holds a particular viewpoint they want to convince the audience of. If they are, you’ll also consider whether their persuasion interferes with how the text is read and understood.

- Does the author correctly identify the intended audience? It’s important to consider whether the author correctly writes the text for the intended audience and what assumptions the author makes about the audience.

- Does the text make sense? Here, you’ll consider whether the author effectively reasons, based on the evidence, to arrive at the text’s conclusion.

- Does the author try to appeal to the audience’s emotions? You’ll need to consider whether the author uses any words, ideas, or techniques to appeal to the audience’s emotions.

- Can the author be believed? Finally, you’ll consider whether the audience will accept the arguments and ideas of the author and why.

Summing up, unlike summaries that focus on what an author said, a rhetorical analysis focuses on how it’s said, and it doesn’t rely on an analysis of whether the author was right or wrong but rather how they made their case to arrive at their conclusions.

Although rhetorical analysis is most used by academics as part of scholarly work, it can be used to analyze any text including speeches, novels, television shows or films, advertisements, or cartoons.

Now that we’ve seen what rhetorical analysis is, let’s consider some of its key concepts .

Any rhetorical analysis starts with the rhetorical situation which identifies the relationships between the different elements of the text. These elements include the audience, author or writer, the author’s purpose, the delivery method or medium, and the content:

- Audience: The audience is simply the readers of a specific piece of text or content or printed material. For speeches or other mediums like film and video, the audience would be the listeners or viewers. Depending on the specific piece of text or the author’s perception, the audience might be real, imagined, or invoked. With a real audience, the author writes to the people actually reading or listening to the content while, for an imaginary audience, the author writes to an audience they imagine would read the content. Similarly, for an invoked audience, the author writes explicitly to a specific audience.

- Author or writer: The author or writer, also commonly referred to as the rhetor in the context of rhetorical analysis, is the person or the group of persons who authored the text or content.

- The author’s purpose: The author’s purpose is the author’s reason for communicating to the audience. In other words, the author’s purpose encompasses what the author expects or intends to achieve with the text or content.

- Alphabetic text includes essays, editorials, articles, speeches, and other written pieces.

- Imaging includes website and magazine advertisements, TV commercials, and the like.

- Audio includes speeches, website advertisements, radio or tv commercials, or podcasts.

- Context: The context of the text or content considers the time, place, and circumstances surrounding the delivery of the text to its audience. With respect to context, it might often also be helpful to analyze the text in a different context to determine its impact on a different audience and in different circumstances.

An author will use claims, supports, and warrants to build the case around their argument, irrespective of whether the argument is logical and clearly defined or needs to be inferred by the audience:

- Claim: The claim is the main idea or opinion of an argument that the author must prove to the intended audience. In other words, the claim is the fact or facts the author wants to convince the audience of. Claims are usually explicitly stated but can, depending on the specific piece of content or text, be implied from the content. Although these claims could be anything and an argument may be based on a single or several claims, the key is that these claims should be debatable.

- Support: The supports are used by the author to back up the claims they make in their argument. These supports can include anything from fact-based, objective evidence to subjective emotional appeals and personal experiences used by the author to convince the audience of a specific claim. Either way, the stronger and more reliable the supports, the more likely the audience will be to accept the claim.

- Warrant: The warrants are the logic and assumptions that connect the supports to the claims. In other words, they’re the assumptions that make the initial claim possible. The warrant is often unstated, and the author assumes that the audience will be able to understand the connection between the claims and supports. In turn, this is based on the author’s assumption that they share a set of values and beliefs with the audience that will make them understand the connection mentioned above. Conversely, if the audience doesn’t share these beliefs and values with the author, the argument will not be that effective.

Appeals are used by authors to convince their audience and, as such, are an integral part of the rhetoric and are often referred to as the rhetorical triangle. As a result, an author may combine all three appeals to convince their audience:

- Ethos: Ethos represents the authority or credibility of the author. To be successful, the author needs to convince the audience of their authority or credibility through the language and delivery techniques they use. This will, for example, be the case where an author writing on a technical subject positions themselves as an expert or authority by referring to their qualifications or experience.

- Logos: Logos refers to the reasoned argument the author uses to persuade their audience. In other words, it refers to the reasons or evidence the author proffers in substantiation of their claims and can include facts, statistics, and other forms of evidence. For this reason, logos is also the dominant approach in academic writing where authors present and build up arguments using reasoning and evidence.

- Pathos: Through pathos, also referred to as the pathetic appeal, the author attempts to evoke the audience’s emotions through the use of, for instance, passionate language, vivid imagery, anger, sympathy, or any other emotional response.

To write a rhetorical analysis, you need to follow the steps below:

With a rhetorical analysis, you don’t choose concepts in advance and apply them to a specific text or piece of content. Rather, you’ll have to analyze the text to identify the separate components and plan and prepare your analysis accordingly.

Here, it might be helpful to use the SOAPSTone technique to identify the components of the work. SOAPSTone is a common acronym in analysis and represents the:

- Speaker . Here, you’ll identify the author or the narrator delivering the content to the audience.

- Occasion . With the occasion, you’ll identify when and where the story takes place and what the surrounding context is.

- Audience . Here, you’ll identify who the audience or intended audience is.

- Purpose . With the purpose, you’ll need to identify the reason behind the text or what the author wants to achieve with their writing.

- Subject . You’ll also need to identify the subject matter or topic of the text.

- Tone . The tone identifies the author’s feelings towards the subject matter or topic.

Apart from gathering the information and analyzing the components mentioned above, you’ll also need to examine the appeals the author uses in writing the text and attempting to persuade the audience of their argument. Moreover, you’ll need to identify elements like word choice, word order, repetition, analogies, and imagery the writer uses to get a reaction from the audience.

Once you’ve gathered the information and examined the appeals and strategies used by the author as mentioned above, you’ll need to answer some questions relating to the information you’ve collected from the text. The answers to these questions will help you determine the reasons for the choices the author made and how well these choices support the overall argument.

Here, some of the questions you’ll ask include:

- What was the author’s intention?

- Who was the intended audience?

- What is the author’s argument?

- What strategies does the author use to build their argument and why do they use those strategies?

- What appeals the author uses to convince and persuade the audience?

- What effect the text has on the audience?

Keep in mind that these are just some of the questions you’ll ask, and depending on the specific text, there might be others.

Once you’ve done your preparation, you can start writing the rhetorical analysis. It will start off with an introduction which is a clear and concise paragraph that shows you understand the purpose of the text and gives more information about the author and the relevance of the text.

The introduction also summarizes the text and the main ideas you’ll discuss in your analysis. Most importantly, however, is your thesis statement . This statement should be one sentence at the end of the introduction that summarizes your argument and tempts your audience to read on and find out more about it.

After your introduction, you can proceed with the body of your analysis. Here, you’ll write at least three paragraphs that explain the strategies and techniques used by the author to convince and persuade the audience, the reasons why the writer used this approach, and why it’s either successful or unsuccessful.

You can structure the body of your analysis in several ways. For example, you can deal with every strategy the author uses in a new paragraph, but you can also structure the body around the specific appeals the author used or chronologically.

No matter how you structure the body and your paragraphs, it’s important to remember that you support each one of your arguments with facts, data, examples, or quotes and that, at the end of every paragraph, you tie the topic back to your original thesis.

Finally, you’ll write the conclusion of your rhetorical analysis. Here, you’ll repeat your thesis statement and summarize the points you’ve made in the body of your analysis. Ultimately, the goal of the conclusion is to pull the points of your analysis together so you should be careful to not raise any new issues in your conclusion.

After you’ve finished your conclusion, you’ll end your analysis with a powerful concluding statement of why your argument matters and an invitation to conduct more research if needed.

A rhetorical analysis aims to explore the goals and motivations of an author, the techniques they’ve used to reach their audience, and how successful these techniques were. Although rhetorical analysis is most used by academics as part of scholarly work, it can be used to analyze any text including speeches, novels, television shows or films, advertisements, or cartoons.

The steps to write a rhetorical analysis include:

Your rhetorical analysis introduction is a clear and concise paragraph that shows you understand the purpose of the text and gives more information about the author and the relevance of the text. The introduction also summarizes the text and the main ideas you’ll discuss in your analysis.

Ethos represents the authority or credibility of the author. To be successful, the author needs to convince the audience of their authority or credibility through the language and delivery techniques they use. This will, for example, be the case where an author writing on a technical subject positions themselves as an expert or authority by referring to their qualifications or experience.

Appeals are used by authors to convince their audience and, as such, are an integral part of the rhetoric and are often referred to as the rhetorical triangle. The 3 types of appeals are ethos, logos, and pathos.

Chapter 6: Thinking and Analyzing Rhetorically

6.3 What is Rhetorical Analysis?

Rhetoric: The art of persuasion

Analysis: Breaking down the whole into pieces for the purpose of examination

Unlike summary, a rhetorical analysis does not only require a restatement of ideas; instead, you must recognize rhetorical moves that an author is making in an attempt to persuade his or her audience to do or to think something. In the 21st century’s abundance of information, it can sometimes be difficult to discern what is a rhetorical strategy and what is simple manipulation; however, an understanding of rhetoric and rhetorical moves will help you become more savvy with the information surrounding you on a day-to-day basis. In other words, rhetorical moves can be a form of manipulation, but if one can recognize those moves, then one can be a more critical consumer of information rather than blindly accepting whatever one reads, sees, hears, etc.

The goal of a rhetorical analysis is to explain what is happening in the text, why the author might have chosen to use a particular move or set of rhetorical moves, and how those choices might affect the audience. The text you analyze might be explanatory, although there will be aspects of argument because you must negotiate with what the author is trying to do and what you think the author is doing. Edward P.J. Corbett observes, rhetorical analysis “is more interested in a literary work for what it does than for what it is” (qtd. in Nordqvist).

One of the elements of doing a rhetorical analysis is looking at a text’s rhetorical situation. The rhetorical situation is the context out of a which a text is created.

- The questions that you can use to examine a text’s rhetorical situation are in Chapter 6.2 .

Another element of rhetorical analysis is simply reading and summarizing the text. You have to be able to describe the basics of the author’s thesis and main points before you can begin to analyze it.

- The questions that you can use to summarize a text are in Chapter 5.1

A third element of rhetorical analysis requires you to connect the rhetorical situation to the text. You need to go beyond summarizing and look at how the author shapes his or her text based on its context. In developing your reading and analytical skills, allow yourself to think about what you’re reading, to question the text and your responses to it, as you read. Use the following questions to help you to take the text apart—dissecting it to see how it works:

- Does the author successfully support the thesis or claim? Is the point held consistently throughout the text, or does it wander at any point?

- Is the evidence the author used effective for the intended audience? How might the intended audience respond to the types of evidence that the author used to support the thesis/claim?

- What rhetorical moves do you see the author making to help achieve his or her purpose? Are there word choices or content choices that seem to you to be clearly related to the author’s agenda for the text or that might appeal to the intended audience?

- Describe the tone in the piece. Is it friendly? Authoritative? Does it lecture? Is it biting or sarcastic? Does the author use simple language, or is it full of jargon? Does the language feel positive or negative? Point to aspects of the text that create the tone; spend some time examining these and considering how and why they work. (Learn more about tone in Section 4.5 “ Tone, Voice, and Point of View . ”)

- Is the author objective, or does he or she try to convince you to have a certain opinion? Why does the author try to persuade you to adopt this viewpoint? If the author is biased, does this interfere with the way you read and understand the text?

- Do you feel like the author knows who you are? Does the text seem to be aimed at readers like you or at a different audience? What assumptions does the author make about their audience? Would most people find these reasonable, acceptable, or accurate?

- Does the text’s flow make sense? Is the line of reasoning logical? Are there any gaps? Are there any spots where you feel the reasoning is flawed in some way?

- Does the author try to appeal to your emotions? Does the author use any controversial words in the headline or the article? Do these affect your reading or your interest?

- Do you believe the author? Do you accept their thoughts and ideas? Why or why not?

It is also a good idea to revisit Section 2.3 “How to Read Rhetorically.” This chapter will compliment the rhetorical questions listed above and help you clearly determine the text’s rhetorical situation.

Once you have done this basic, rhetorical, critical reading of your text, you are ready to think about how the rhetorical situation ( Section 6.2 ) – the context out of which the text arises – influences certain rhetorical appeals ( Section 6.4 ) that appear in it.

Attributions

This chapter contains material from “The Word on College Reading and Writing” by Monique Babin, Carol Burnell, Susan Pesznecker, Nicole Rosevear, Jaime Wood , OpenOregon Educational Resources , Higher Education Coordination Commission: Office of Community Colleges and Workforce Development is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing by Melanie Gagich & Emilie Zickel is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Feedback/Errata

Comments are closed.

Rhetorical Analysis Definition and Examples

The analysis can be used on any communication, even a bumper sticker

- An Introduction to Punctuation

Sample Rhetorical Analyses

Examples and observations, analyzing effects, analyzing greeting card verse, analyzing starbucks, rhetorical analysis vs. literary criticism.

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Rhetorical analysis is a form of criticism or close reading that employs the principles of rhetoric to examine the interactions between a text, an author, and an audience . It's also called rhetorical criticism or pragmatic criticism.

Rhetorical analysis may be applied to virtually any text or image—a speech , an essay , an advertisement, a poem, a photograph, a web page, even a bumper sticker. When applied to a literary work, rhetorical analysis regards the work not as an aesthetic object but as an artistically structured instrument for communication. As Edward P.J. Corbett has observed, rhetorical analysis "is more interested in a literary work for what it does than for what it is."

- A Rhetorical Analysis of Claude McKay's "Africa"

- A Rhetorical Analysis of E.B. White's "The Ring of Time"

- A Rhetorical Analysis of U2's "Sunday Bloody Sunday"

- "Our response to the character of the author—whether it is called ethos, or 'implied author,' or style , or even tone—is part of our experience of his work, an experience of the voice within the masks, personae , of the work...Rhetorical criticism intensifies our sense of the dynamic relationships between the author as a real person and the more or less fictive person implied by the work." (Thomas O. Sloan, "Restoration of Rhetoric to Literary Study." The Speech Teacher )

- "[R]hetorical criticism is a mode of analysis that focuses on the text itself. In that respect, it is like the practical criticism that the New Critics and the Chicago School indulge in. It is unlike these modes of criticism in that it does not remain inside the literary work but works outward from the text to considerations of the author and the audience...In talking about the ethical appeal in his 'Rhetoric,' Aristotle made the point that although a speaker may come before an audience with a certain antecedent reputation, his ethical appeal is exerted primarily by what he says in that particular speech before that particular audience. Likewise, in rhetorical criticism, we gain our impression of the author from what we can glean from the text itself—from looking at such things as his ideas and attitudes, his stance, his tone, his style. This reading back to the author is not the same sort of thing as the attempt to reconstruct the biography of a writer from his literary work. Rhetorical criticism seeks simply to ascertain the particular posture or image that the author is establishing in this particular work in order to produce a particular effect on a particular audience." (Edward P.J. Corbett, "Introduction" to " Rhetorical Analyses of Literary Works ")

"[A] complete rhetorical analysis requires the researcher to move beyond identifying and labeling in that creating an inventory of the parts of a text represents only the starting point of the analyst's work. From the earliest examples of rhetorical analysis to the present, this analytical work has involved the analyst in interpreting the meaning of these textual components—both in isolation and in combination—for the person (or people) experiencing the text. This highly interpretive aspect of rhetorical analysis requires the analyst to address the effects of the different identified textual elements on the perception of the person experiencing the text. So, for example, the analyst might say that the presence of feature x will condition the reception of the text in a particular way. Most texts, of course, include multiple features, so this analytical work involves addressing the cumulative effects of the selected combination of features in the text." (Mark Zachry, "Rhetorical Analysis" from " The Handbook of Business Discourse , " Francesca Bargiela-Chiappini, editor)

"Perhaps the most pervasive type of repeated-word sentence used in greeting card verse is the sentence in which a word or group of words is repeated anywhere within the sentence, as in the following example:

In quiet and thoughtful ways , in happy and fun ways , all ways , and always , I love you.

In this sentence, the word ways is repeated at the end of two successive phrases, picked up again at the beginning of the next phrase, and then repeated as part of the word always . Similarly, the root word all initially appears in the phrase 'all ways' and is then repeated in a slightly different form in the homophonic word always . The movement is from the particular ('quiet and thoughtful ways,' 'happy and fun ways'), to the general ('all ways'), to the hyperbolic ('always')." (Frank D'Angelo, "The Rhetoric of Sentimental Greeting Card Verse." Rhetoric Review )

"Starbucks not just as an institution or as a set of verbal discourses or even advertising but as a material and physical site is deeply rhetorical...Starbucks weaves us directly into the cultural conditions of which it is constitutive. The color of the logo, the performative practices of ordering, making, and drinking the coffee, the conversations around the tables, and the whole host of other materialities and performances of/in Starbucks are at once the rhetorical claims and the enactment of the rhetorical action urged. In short, Starbucks draws together the tripartite relationships among place, body, and subjectivity. As a material/rhetorical place, Starbucks addresses and is the very site of a comforting and discomforting negotiation of these relationships." (Greg Dickinson, "Joe's Rhetoric: Finding Authenticity at Starbucks." Rhetoric Society Quarterly )

"What essentially are the differences between literary criticism analysis and rhetorical analysis? When a critic explicates Ezra Pound's Canto XLV , for example, and shows how Pound inveighs against usury as an offense against nature that corrupts society and the arts, the critic must point out the 'evidence'—the 'artistic proofs' of example and enthymeme [a formal syllogistic argument that is incompletely stated}—that Pound has drawn upon for his fulmination. The critic will also call attention to the 'arrangement' of the parts of that argument as a feature of the 'form' of the poem just as he may inquire into the language and syntax. Again these are matters that Aristotle assigned mainly to rhetoric...

"All critical essays dealing with the persona of a literary work are in reality studies of the 'Ethos' of the 'speaker' or 'narrator'—the voice—source of the rhythmic language which attracts and holds the kind of readers the poet desires as his audience, and the means this persona consciously or unconsciously chooses, in Kenneth Burke's term, to 'woo' that reader-audience." (Alexander Scharbach, "Rhetoric and Literary Criticism: Why Their Separation." College Composition and Communication )

- Definition and Examples of Explication (Analysis)

- Audience Analysis in Speech and Composition

- Definition and Examples of Ethos in Classical Rhetoric

- Stylistics and Elements of Style in Literature

- A Rhetorical Analysis of U2's 'Sunday Bloody Sunday'

- Definition of Belles-Lettres in English Grammer

- Definition of Audience

- Invented Ethos (Rhetoric)

- What is a Rhetorical Situation?

- Rhetoric: Definitions and Observations

- Critical Analysis in Composition

- Definition and Examples of the Topoi in Rhetoric

- What Is the Second Persona?

- Feminist Literary Criticism

- What Is Phronesis?

- Quotes About Close Reading

Table of Contents

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process, rhetorical analysis.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida , Julie Staggers - Washington State University

How can I use rhetorical analysis of texts, people, events, and situations as an interpretive method? Learn how rhetorical analysis can help you understand why people say and do what they do.

Rhetorical Analysis refers to

- the practice of analyzing a rhetorical situation

- a mode of reasoning that informs composing and interpretation.

- a heuristic, an invention practice , that helps writers use to kickstart invention

- a method of analysis used to understand and critique texts .

Rhetorical Analysis is a vital workplace, academic, and personal competency–a way of producing rhetorical knowledge