There has been an error on this page. Error Code 000

Please contact the ocio help desk for additional support., your issue id is: 1886394443357365237.

Introductory essay

Written by the educator who created What Makes Us Human?, a brief look at the key facts, tough questions and big ideas in his field. Begin this TED Study with a fascinating read that gives context and clarity to the material.

As a biological anthropologist, I never liked drawing sharp distinctions between human and non-human. Such boundaries make little evolutionary sense, as they ignore or grossly underestimate what we humans have in common with our ancestors and other primates. What's more, it's impossible to make sharp distinctions between human and non-human in the paleoanthropological record. Even with a time machine, we couldn't go back to identify one generation of humans and say that the previous generation contained none: one's biological parents, by definition, must be in the same species as their offspring. This notion of continuity is inherent to most evolutionary perspectives and it's reflected in the similarities (homologies) shared among very different species. As a result, I've always been more interested in what makes us similar to, not different from, non-humans.

Evolutionary research has clearly revealed that we share great biological continuity with others in the animal kingdom. Yet humans are truly unique in ways that have not only shaped our own evolution, but have altered the entire planet. Despite great continuity and similarity with our fellow primates, our biocultural evolution has produced significant, profound discontinuities in how we interact with each other and in our environment, where no precedent exists in other animals. Although we share similar underlying evolved traits with other species, we also display uses of those traits that are so novel and extraordinary that they often make us forget about our commonalities. Preparing a twig to fish for termites may seem comparable to preparing a stone to produce a sharp flake—but landing on the moon and being able to return to tell the story is truly out of this non-human world.

Humans are the sole hominin species in existence today. Thus, it's easier than it would have been in the ancient past to distinguish ourselves from our closest living relatives in the animal kingdom. Primatologists such as Jane Goodall and Frans de Waal, however, continue to clarify why the lines dividing human from non-human aren't as distinct as we might think. Goodall's classic observations of chimpanzee behaviors like tool use, warfare and even cannibalism demolished once-cherished views of what separates us from other primates. de Waal has done exceptional work illustrating some continuity in reciprocity and fairness, and in empathy and compassion, with other species. With evolution, it seems, we are always standing on the shoulders of others, our common ancestors.

Primatology—the study of living primates—is only one of several approaches that biological anthropologists use to understand what makes us human. Two others, paleoanthropology (which studies human origins through the fossil record) and molecular anthropology (which studies human origins through genetic analysis), also yield some surprising insights about our hominin relatives. For example, Zeresenay Alemsegad's painstaking field work and analysis of Selam, a 3.3 million-year old fossil of a 3-year-old australopithecine infant from Ethiopia, exemplifies how paleoanthropologists can blur boundaries between living humans and apes.

Selam, if alive today, would not be confused with a three-year-old human—but neither would we mistake her for a living ape. Selam's chimpanzee-like hyoid bone suggests a more ape-like form of vocal communication, rather than human language capability. Overall, she would look chimp-like in many respects—until she walked past you on two feet. In addition, based on Selam's brain development, Alemseged theorizes that Selam and her contemporaries experienced a human-like extended childhood with a complex social organization.

Fast-forward to the time when Neanderthals lived, about 130,000 – 30,000 years ago, and most paleoanthropologists would agree that language capacity among the Neanderthals was far more human-like than ape-like; in the Neanderthal fossil record, hyoids and other possible evidence of language can be found. Moreover, paleogeneticist Svante Pääbo's groundbreaking research in molecular anthropology strongly suggests that Neanderthals interbred with modern humans. Paabo's work informs our genetic understanding of relationships to ancient hominins in ways that one could hardly imagine not long ago—by extracting and comparing DNA from fossils comprised largely of rock in the shape of bones and teeth—and emphasizes the great biological continuity we see, not only within our own species, but with other hominins sometimes classified as different species.

Though genetics has made truly astounding and vital contributions toward biological anthropology by this work, it's important to acknowledge the equally pivotal role paleoanthropology continues to play in its tandem effort to flesh out humanity's roots. Paleoanthropologists like Alemsegad draw on every available source of information to both physically reconstruct hominin bodies and, perhaps more importantly, develop our understanding of how they may have lived, communicated, sustained themselves, and interacted with their environment and with each other. The work of Pääbo and others in his field offers powerful affirmations of paleoanthropological studies that have long investigated the contributions of Neanderthals and other hominins to the lineage of modern humans. Importantly, without paleoanthropology, the continued discovery and recovery of fossil specimens to later undergo genetic analysis would be greatly diminished.

Molecular anthropology and paleoanthropology, though often at odds with each other in the past regarding modern human evolution, now seem to be working together to chip away at theories that portray Neanderthals as inferior offshoots of humanity. Molecular anthropologists and paleoanthropologists also concur that that human evolution did not occur in ladder-like form, with one species leading to the next. Instead, the fossil evidence clearly reveals an evolutionary bush, with numerous hominin species existing at the same time and interacting through migration, some leading to modern humans and others going extinct.

Molecular anthropologist Spencer Wells uses DNA analysis to understand how our biological diversity correlates with ancient migration patterns from Africa into other continents. The study of our genetic evolution reveals that as humans migrated from Africa to all continents of the globe, they developed biological and cultural adaptations that allowed for survival in a variety of new environments. One example is skin color. Biological anthropologist Nina Jablonski uses satellite data to investigate the evolution of skin color, an aspect of human biological variation carrying tremendous social consequences. Jablonski underscores the importance of trying to understand skin color as a single trait affected by natural selection with its own evolutionary history and pressures, not as a tool to grouping humans into artificial races.

For Pääbo, Wells, Jablonski and others, technology affords the chance to investigate our origins in exciting new ways, adding pieces into the human puzzle at a record pace. At the same time, our technologies may well be changing who we are as a species and propelling us into an era of "neo-evolution."

Increasingly over time, human adaptations have been less related to predators, resources, or natural disasters, and more related to environmental and social pressures produced by other humans. Indeed, biological anthropologists have no choice but to consider the cultural components related to human evolutionary changes over time. Hominins have been constructing their own niches for a very long time, and when we make significant changes (such as agricultural subsistence), we must adapt to those changes. Classic examples of this include increases in sickle-cell anemia in new malarial environments, and greater lactose tolerance in regions with a long history of dairy farming.

Today we can, in some ways, evolve ourselves. We can enact biological change through genetic engineering, which operates at an astonishing pace in comparison to natural selection. Medical ethicist Harvey Fineberg calls this "neo-evolution". Fineberg goes beyond asking who we are as a species, to ask who we want to become and what genes we want our offspring to inherit. Depending on one's point of view, the future he envisions is both tantalizing and frightening: to some, it shows the promise of science to eradicate genetic abnormalities, while for others it raises the specter of eugenics. It's also worth remembering that while we may have the potential to influence certain genetic predispositions, changes in genotypes do not guarantee the desired results. Environmental and social pressures like pollution, nutrition or discrimination can trigger "epigenetic" changes which can turn genes on or off, or make them less or more active. This is important to factor in as we consider possible medical benefits from efforts in self-directed evolution. We must also ask: In an era of human-engineered, rapid-rate neo-evolution, who decides what the new human blueprints should be?

Technology figures in our evolutionary future in other ways as well. According to anthropologist Amber Case, many of our modern technologies are changing us into cyborgs: our smart phones, tablets and other tools are "exogenous components" that afford us astonishing and unsettling capabilities. They allow us to travel instantly through time and space and to create second, "digital selves" that represent our "analog selves" and interact with others in virtual environments. This has psychological implications for our analog selves that worry Case: a loss of mental reflection, the "ambient intimacy" of knowing that we can connect to anyone we want to at any time, and the "panic architecture" of managing endless information across multiple devices in virtual and real-world environments.

Despite her concerns, Case believes that our technological future is essentially positive. She suggests that at a fundamental level, much of this technology is focused on the basic concerns all humans share: who am I, where and how do I fit in, what do others think of me, who can I trust, who should I fear? Indeed, I would argue that we've evolved to be obsessed with what other humans are thinking—to be mind-readers in a sense—in a way that most would agree is uniquely human. For even though a baboon can assess those baboons it fears and those it can dominate, it cannot say something to a second baboon about a third baboon in order to trick that baboon into telling a fourth baboon to gang up on a fifth baboon. I think Facebook is a brilliant example of tapping into our evolved human psychology. We can have friends we've never met and let them know who we think we are—while we hope they like us and we try to assess what they're actually thinking and if they can be trusted. It's as if technology has provided an online supply of an addictive drug for a social mind evolved to crave that specific stimulant!

Yet our heightened concern for fairness in reciprocal relationships, in combination with our elevated sense of empathy and compassion, have led to something far greater than online chats: humanism itself. As Jane Goodall notes, chimps and baboons cannot rally together to save themselves from extinction; instead, they must rely on what she references as the "indomitable human spirit" to lessen harm done to the planet and all the living things that share it. As Goodall and other TED speakers in this course ask: will we use our highly evolved capabilities to secure a better future for ourselves and other species?

I hope those reading this essay, watching the TED Talks, and further exploring evolutionary perspectives on what makes us human, will view the continuities and discontinuities of our species as cause for celebration and less discrimination. Our social dependency and our prosocial need to identify ourselves, our friends, and our foes make us human. As a species, we clearly have major relationship problems, ranging from personal to global scales. Yet whenever we expand our levels of compassion and understanding, whenever we increase our feelings of empathy across cultural and even species boundaries, we benefit individually and as a species.

Get started

Zeresenay Alemseged

The search for humanity's roots, relevant talks.

Spencer Wells

A family tree for humanity.

Svante Pääbo

Dna clues to our inner neanderthal.

Nina Jablonski

Skin color is an illusion.

We are all cyborgs now

Harvey Fineberg

Are we ready for neo-evolution.

Frans de Waal

Moral behavior in animals.

Jane Goodall

What separates us from chimpanzees.

Your Article Library

Human evolution: short essay on human evolution.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Man is a product of evolution. Therefore human evolution is intimately related to the origin of life and its development on the face of earth. It is customary to speak of evolution ‘from amoeba to Man’, as if the amoeba is the simplest form of life. But in reality, there are several organisms more primitives than amoeba, say for example viruses. The evolution from a self-replicating organic molecule to a protozoan, like amoeba, is the most complex step in evolution, which might have consumed the same extent of time from protozoan to man.

The term evolution was first applied by the English philosopher Herbert Spencer to mean the historical development of life. Since then evolution denotes a change, although the term may be defined in several ways. In the context of man, the biological evolution started with the ‘Origin of life’. In the beginning, there was nothing. The first successful formation of protoplasm initiated the life and its continuous development proceeded towards complexity to give rise different life forms of evolved type.

About 10 billion years after the formation of Universe, the earth was formed. Life on earth appeared far late, nearly three billion years ago. Of the several evolutionary problems, perhaps the origin of life is the most critical, since there is no record concerning it. Life has been characterized by the capacity of performing certain vital functional activities like metabolism, growth and reproduction. There is no ambiguity regarding this point. But how the first life came on earth is a matter of conjecture.

Ancient thinkers speculated that life originated spontaneously from inorganic components of the environment, just after the formation of earth. A series of physio-chemical processes were perhaps responsible behind this creation. Aristotle (384 BC to 322 BC) was the pioneer in this line of thought and nobody raised any voice against his speculation till seventeenth Century. But in seventeenth Century, an Italian scientist, Francesco Redi (1627 -1697) made an experiment with two pieces of meat.

One of the pieces was kept fully covered and the other piece was kept in an open place. After some days he examined both of the pieces very carefully. He noticed that, flies laid eggs on the uncovered piece of meat and so many new flies had born. But the covered piece of meat had not produced any new fly, as there was absolutely no access of flies.

Redi tried to establish the fact, that living organisms cannot be originated spontaneously from inorganic components. More or less at the same time, Leuwenhock (1632 – 1723) by studying several microorganisms like protozoa, sperm, bacteria etc. under microscope declared that the spontaneous generation was possible for the microorganisms. Later, Louis Pasteur (1822 -1895) also studied much to furnish evidences in support of spontaneous creation.

In fact, scientists of this period were perplexed in finding out how life began spontaneously as a matter of chance. Philosophers, Thinkers and Scientists all had submitted their varied thought and propositions regarding the nature and mechanism of origin of life on earth. Different religions had also put forth different concepts in this connection.

Related Articles:

- Evolution of Plants: Essay on the Evolution of Plants

- Evolution of Human Resources Management – Essay

No comments yet.

Leave a reply click here to cancel reply..

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- Image & Use Policy

- Translations

UC MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY

Understanding Evolution

Your one-stop source for information on evolution

- ES en Español

An introduction to evolution

The definition.

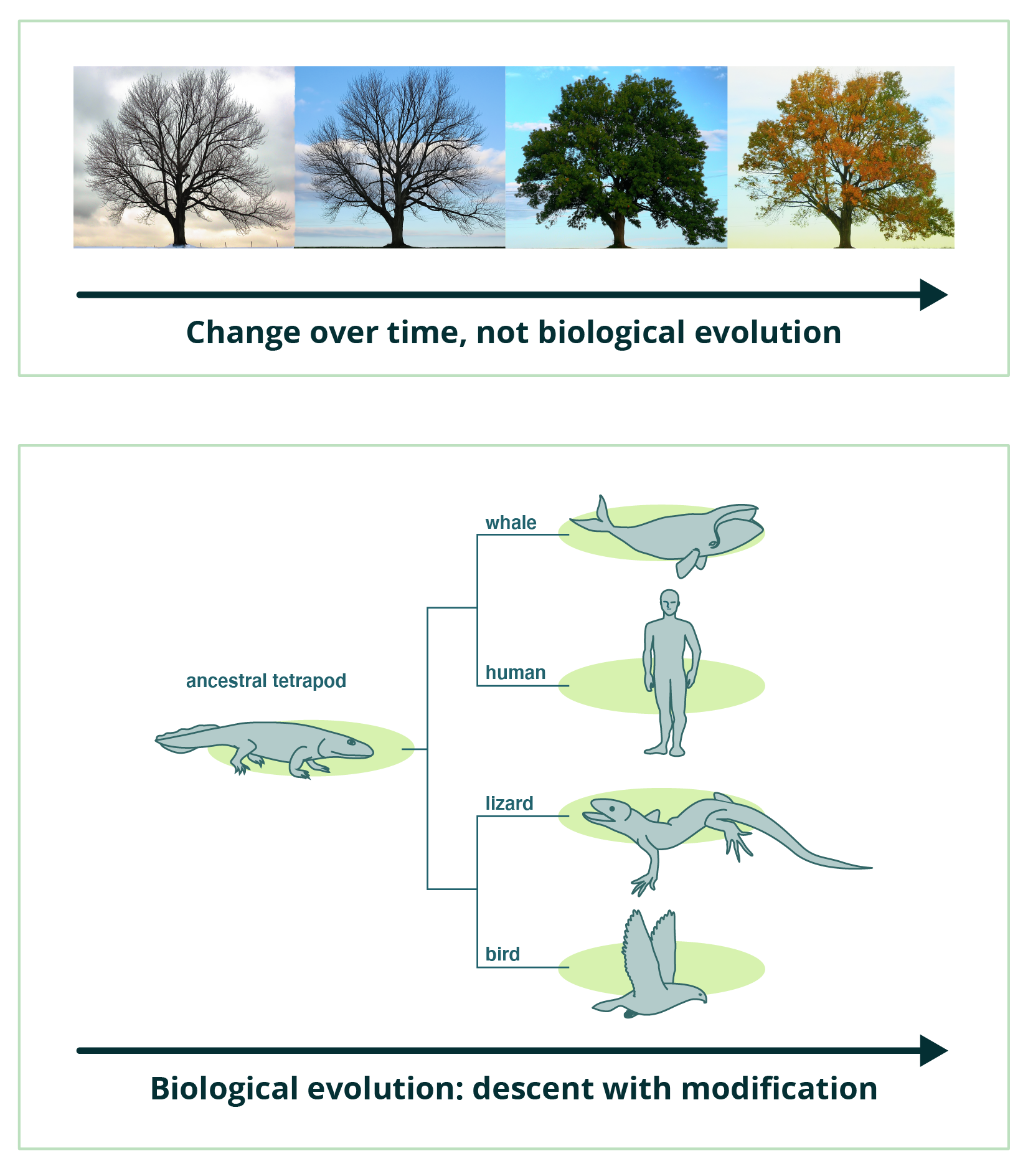

Biological evolution, simply put, is descent with inherited modification. This definition encompasses everything from small-scale evolution (for example, changes in the frequency of different gene versions in a population from one generation to the next) to large-scale evolution (for example, the descent of different species from a shared ancestor over many generations). Evolution helps us to understand the living world around us, as well as its history.

The explanation

Biological evolution is not simply a matter of change over time. Many things change over time: caterpillars turn into moths, trees lose and regrow their leaves, mountain ranges rise and erode, but they aren’t examples of biological evolution because they don’t involve descent with inherited modifications.

All life on Earth shares a common ancestor , just as you and your cousins share a common grandmother. Through the process of descent with modification, this common ancestor gave rise to the diverse species that we see documented in the fossil record and around us today. Evolution means that we’re all distant cousins: humans and oak trees, hummingbirds and whales.

- More Details

- Evo Examples

- Teaching Resources

You can learn lots more about common ancestry in Evo 101: Patterns or in our Tree Room .

Learn about common ancestry in context:

- A fish of a different color

- The legless lizards of LAX

- What has the head of a crocodile and the gills of a fish?

Find additional lessons, activities, videos, and articles that focus on common ancestry.

Reviewed and updated June, 2020.

Evolution 101

The history of life: looking at the patterns

Subscribe to our newsletter

- Teaching resource database

- Correcting misconceptions

- Conceptual framework and NGSS alignment

- Image and use policy

- Evo in the News

- The Tree Room

- Browse learning resources

ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

Theory of evolution.

The theory of evolution is a shortened form of the term “theory of evolution by natural selection,” which was proposed by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace in the nineteenth century.

Biology, Ecology, Earth Science, Geology, Geography, Physical Geography

Young Charles Darwin

Painting of a young Charles Darwin

Photograph by James L. Stanfield

Ideas aimed at explaining how organisms change, or evolve, over time date back to Anaximander of Miletus, a Greek philosopher who lived in the 500s B.C.E. Noting that human babies are born helpless, Anaximander speculated that humans must have descended from some other type of creature whose young could survive without any help. He concluded that those ancestors must be fish, since fish hatch from eggs and immediately begin living with no help from their parents. From this reasoning, he proposed that all life began in the sea.

Anaximander was correct; humans can indeed trace our ancestry back to fish. His idea, however, was not a theory in the scientific meaning of the word, because it could not be subjected to testing that might support it or prove it wrong. In science, the word “ theory ” indicates a very high level of certainty. Scientists talk about evolution as a theory , for instance, just as they talk about Einstein’s explanation of gravity as a theory .

A theory is an idea about how something in nature works that has gone through rigorous testing through observations and experiments designed to prove the idea right or wrong. When it comes to the evolution of life, various philosophers and scientists, including an eighteenth-century English doctor named Erasmus Darwin, proposed different aspects of what later would become evolutionary theory. But evolution did not reach the status of being a scientific theory until Darwin’s grandson, the more famous Charles Darwin, published his famous book On the Origin of Species . Darwin and a scientific contemporary of his, Alfred Russel Wallace, proposed that evolution occurs because of a phenomenon called natural selection .

In the theory of natural selection, organisms produce more offspring than are able to survive in their environment. Those that are better physically equipped to survive, grow to maturity, and reproduce. Those that are lacking in such fitness, on the other hand, either do not reach an age when they can reproduce or produce fewer offspring than their counterparts. Natural selection is sometimes summed up as “survival of the fittest” because the “fittest” organisms—those most suited to their environment—are the ones that reproduce most successfully, and are most likely to pass on their traits to the next generation.

This means that if an environment changes, the traits that enhance survival in that environment will also gradually change, or evolve. Natural selection was such a powerful idea in explaining the evolution of life that it became established as a scientific theory . Biologists have since observed numerous examples of natural selection influencing evolution . Today, it is known to be just one of several mechanisms by which life evolves. For example, a phenomenon known as genetic drift can also cause species to evolve. In genetic drift , some organisms —purely by chance—produce more offspring than would be expected. Those organisms are not necessarily the fittest of their species, but it is their genes that get passed on to the next generation.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

Evolution: A Very Short Introduction (1st edn)

Author webpage

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Less than 150 years ago, the view that living species were the result of special creation by God was still dominant. The recognition by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace of the mechanism of evolution by natural selection has completely transformed our understanding of the living world, including our own origins. Evolution: A Very Short Introduction provides a summary of the process of evolution by natural selection, highlighting the wide range of evidence, and explains how natural selection gives rise to adaptations and eventually, over many generations, to new species. It introduces the central concepts of the field of evolutionary biology and discusses some of the remaining questions regarding evolutionary processes.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

External resource

- In the OUP print catalogue

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Frontiers for Young Minds

- Download PDF

A Brief Account of Human Evolution for Young Minds

Most of what we know about the origin of humans comes from the research of paleoanthropologists, scientists who study human fossils. Paleoanthropologists identify the sites where fossils can be found. They determine the age of fossils and describe the features of the bones and teeth discovered. Recently, paleoanthropologists have added genetic technology to test their hypotheses. In this article, we will tell you a little about prehistory, a period of time including pre-humans and humans and lasting about 10 million years. During the Prehistoric Period, events were not reported in writing. Most information on prehistory is obtained through studying fossils. Ten to twelve million years ago, primates divided into two branches, one included species leading to modern (current) humans and the other branch to the great apes that include gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and orangutans. The branch leading to modern humans included several different species. When one of these species—known as the Neanderthals—inhabited Eurasia, they were not alone; Homo sapiens and other Homo species were also present in this region. All the other species of Homo have gone extinct, with the exception of Homo sapiens , our species, which gradually colonized the entire planet. About 12,000 years ago, during the Neolithic Period, some (but not all) populations of H. sapiens passed from a wandering lifestyle of hunting and gathering to one of sedentary farming, building villages and towns. They developed more complex social organizations and invented writing. This was the end of prehistory and the beginning of history.

What Is Evolution?

Evolution is the process by which living organisms evolve from earlier, more simple organisms. According to the scientist Charles Darwin (1809–1882), evolution depends on a process called natural selection. Natural selection results in the increased reproductive capacities of organisms that are best suited for the conditions in which they are living. Darwin’s theory was that organisms evolve as a result of many slight changes over the course of time. In this article, we will discuss evolution during pre-human times and human prehistory. During prehistory, writing was not yet developed. But much important information on prehistory is obtained through studies of the fossil record [ 1 ].

How Did Humans Evolve?

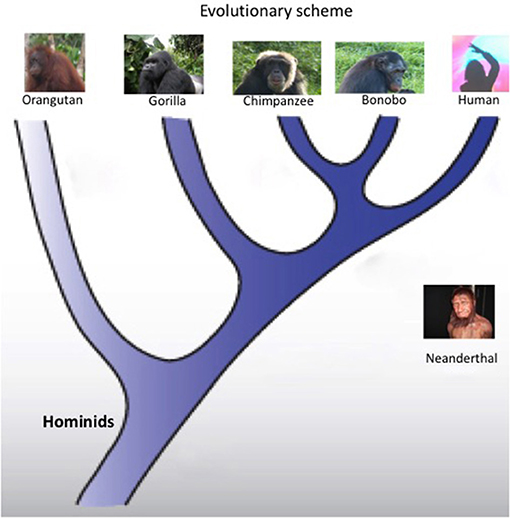

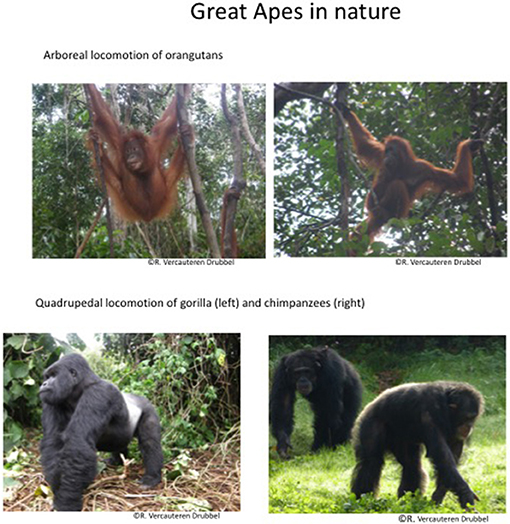

Primates, like humans, are mammals. Around ten to twelve million years ago, the ancestral primate lineage split through speciation from one common ancestor into two major groups. These two lineages evolved separately to become the variety of species we see today. Members of one group were the early version of what we know today as the great apes (gorillas, chimpanzees, and bonobos in Africa, orangutans in Asia) ( Figures 1 , 2 ); that is, the modern great apes evolved from this ancestral group. They mostly remained in forest with an arboreal lifestyle, meaning they live in trees. Great apes are also quadrupeds which means they move around with four legs on the ground (see Figure 2 ). The other group evolved in a different way. They became terrestrial, meaning they live on land and not in trees. From being quadrupeds they evolved to bipeds, meaning they move around on their two back legs. In addition the size of their brain increased. This is the group that, through evolution, gave rise to the modern current humans. Many fossils found in Africa are from the Australopithecus afarensis, Homo sapiens ."> genus named Australopithecus (which means southern ape). This genus is extinct, but fossil studies revealed interesting features about their adaptation toward a terrestrial lifestyle.

- Figure 1 - Evolutionary scheme, showing that great apes and humans all evolved from a common ancestor.

- The Neanderthal picture is a statue designed from a fossil skeleton.

- Figure 2 - Great Apes in nature.

- (above) Arboreal (in trees) locomotion of orangutans and (under) the quadrupedal (four-foot) locomotion of gorillas and chimpanzees.

Australopithecus afarensis and Lucy

In Ethiopia (East Africa) there is a site called Hadar, where several fossils of different animal species were found. Among those fossils was Australopithecus afarensis . In 1974, paleoanthropologists found an almost complete skeleton of one specimen of this species and named it Lucy, from The Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” The whole world found out about Lucy and she was in every newspaper: she became a global celebrity. This small female—only about 1.1 m tall—lived 3.2 million years ago. Analysis of her femurs (thigh bones) showed that she used terrestrial locomotion. Lucy could have used arboreal and bipedal locomotion as well, as foot bones of another A. afarensis individual had a curve similar to that found in the feet of modern humans [ 2 ]. Authors of this finding suggested accordingly that A. afarensis was exclusively bipedal and could have been a hunter-gatherer.

Homo habilis , Homo erectus , and Homo neanderthalensis

Homo is the genus (group of species) that includes modern humans, like us, and our most closely related extinct ancestors. Organisms that belong to the same species produce viable offspring. The famous paleoanthropologist named Louis Leakey, along with his team, discovered Homo habilis (meaning handy man) in 1964. Homo habilis was the most ancient species of Homo ever found [ 2 ]. Homo habilis appeared in Tanzania (East Africa) over 2.8 million years ago, and 1.5 million years ago became exinct. They were estimated to be about 1.40 meter tall and were terrestrial. They were different from Australopithecus because of the form of the skull. The shape was not piriform (pear-shaped), but spheroid (round), like the head of a modern human. Homo habilis made stone tools, a sign of creativity [ 3 ].

In Asia, in 1891, Eugene Dubois (also a paleoanthropologist) discovered the first fossil of Homo erectus (meaning upright man), which appeared 1.8 million years ago. This fossil received several names. The best known are Pithecanthropus (ape-man) and Sinanthropus (Chinese-man). Homo erectus appeared in East Africa and migrated to Asia, where they carved refined tools from stone [ 4 ]. Dubois also brought some shells of the time of H erectus from Java to Europe. Contemporary scientists studied these shells and found engravings that dated from 430,000 and 540,000 years ago. They concluded that H. erectus individuals were able to express themselves using symbols [ 5 ].

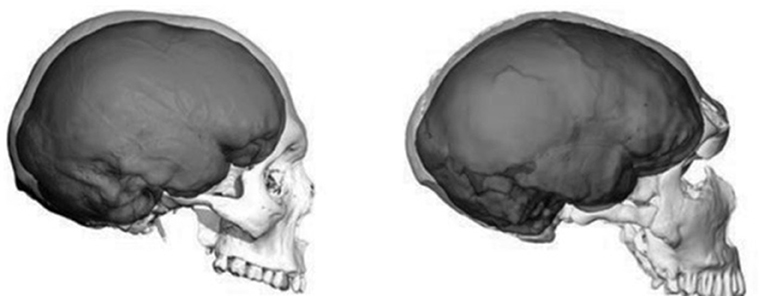

Several Homo species emerged following H. erectus and quite a few coexisted for some time. The best known one is Homo neanderthalensis ( Figure 3 ), usually called Neanderthals and they were known as the European branch originating from two lineages that diverged around 400,000 years ago, with the second branch (lineage) Homo sapiens known as the African branch. The first Neanderthal fossil, dated from around 430,000 years ago, was found in La Sima de los Huesos in Spain and is considered to originate from the common ancestor called Homo heidelbergensis [ 6 ]. Neanderthals used many of the natural resources in their environment: animals, plants, and minerals. Homo neanderthalensis hunted terrestrial and marine (ocean) animals, requiring a variety of weapons. Tens of thousands of stone tools from Neanderthal sites are exhibited in many museums. Neanderthals created paintings in the La Pasiega cave in the South of Spain and decorated their bodies with jewels and colored paint. Graves were found, which meant they held burial ceremonies.

- Figure 3 - A comparison of the skulls of Homo sapiens (Human) (left) vs. Homo neanderthalensis (Neanderthal) (right).

- You can see a shape difference. From Scientific American Vol. 25, No. 4, Autumn 2016 (modified).

Denisovans are a recent addition to the human tree. In 2010, the first specimen was discovered in the Denisova cave in south-western Siberia. Very little information is known on their behavior. They deserve further studies due to their interactions with Neandertals and other Homo species (see below) [ 7 ].

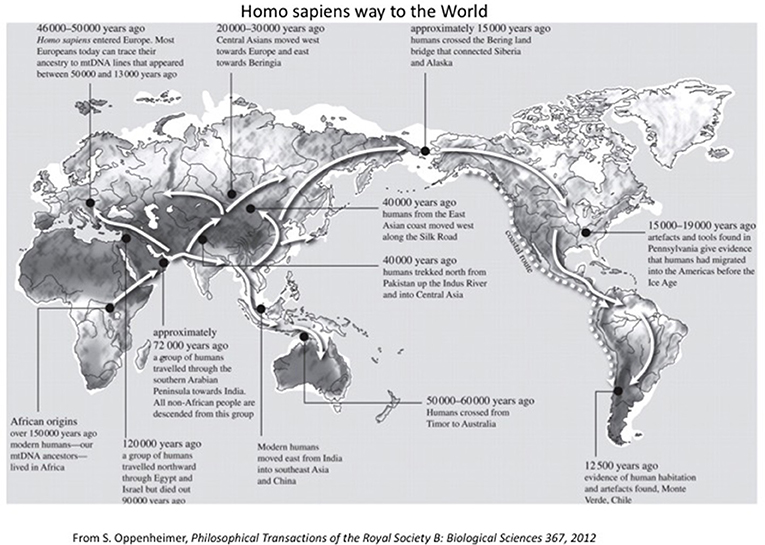

Homo sapiens

Fossils recently discovered in Morocco (North Africa) have added to the intense debate on the spread of H. sapiens after they originated 315,000 years ago [ 8 ]. The location of these fossils could mean that Homo sapiens had visited the whole of Africa. In the same way, the scattering of fossils out of Africa indicated their migrations to various continents [ 9 ]. While intensely debated, hypotheses focus on either a single dispersal or multiple dispersals out of the African continent [ 10 , 11 ]. Nevertheless, even if the origin of the migration to Europe is still a matter of debate [ 12 ], it appears that H. sapiens was present in Israel [ 13 ] 180,000 years ago. Therefore, it could be that migration to Europe was not directly from Africa but indirectly through a stay in Israel-Asia. They arrived about 45,000 years ago into Europe [ 14 ] where the Neanderthals were already present (see above). Studies of ancient DNA show that H. sapiens had babies with Neanderthals and Denisovans. Nowadays people living in Europe and Asia share between 1 and 4% of their DNA with either Neanderthals or Denisovans [ 15 ].

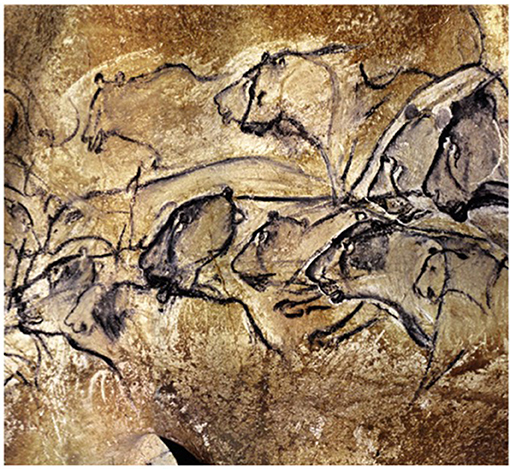

Several thousand years ago H. sapiens already made art, like for example the wall painting in the Chauvet cave (36,000 years ago) ( Figure 4 ) and the Lascaux cave (19,000 years ago), both in France. The quality of the paintings shows great artistic ability and intellectual development. Homo sapiens continued to prospect the Earth. They crossed the Bering Land Bridge, connecting Siberia and Alaska and moved south 12,500 years ago, to what is now called Chile. Homo sapiens gradually colonized our entire planet ( Figure 5 ).

- Figure 4 - The lions in the Chauvet cave (−36,000 years).

- In this period wild lions were present in Eurasia . Photo: Bradshaw foundation.com. Note the lively character of the picture.

- Figure 5 - Homo sapiens traveled in the world at various periods as shown on the map.

- They had only their legs to move!

The Neolithic Revolution

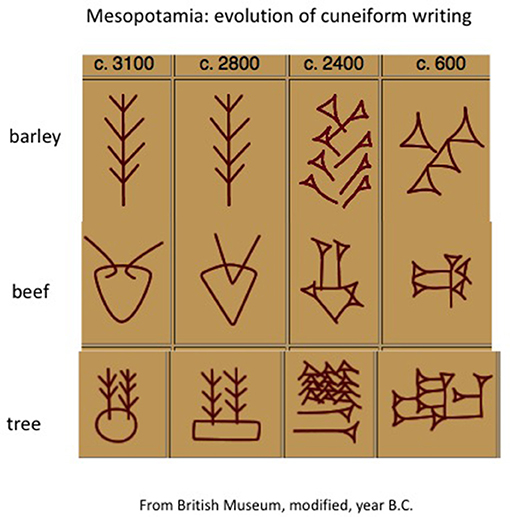

Neolithic Period means New Stone Age, due to the new stone technology that was developed during that time. The Neolithic Period started at the end of the glacial period 11,700 years ago. There was a change in the way humans lived during the Neolithic Period. Ruins found in Mesopotamia tell us early humans lived in populated villages. Due to the start of agriculture, most wandering hunter-gatherers became sedentary farmers. Instead of hunting dogs familiar with hunter-gatherers, farmers preferred sheepdogs [ 16 ]. In the Neolithic age, humans were farming and herding, keeping goats and sheep. Aurochs (extinct wild cattle), shown in the paintings from the Lascaux cave, are early ancestors of the domesticated cows we have today [ 17 ]. The first produce which early humans began to grow in Mesopotamia (a historical region in West Asia, situated between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers) was peas and wheat [ 18 ]. Animals and crops were traded and written records were kept of these trades. Clay tokens were the first money for these transactions. The Neolithic Period saw the creation of commerce, money, mathematics, and writing ( Figure 6 ) in Sumer, a region of Mesopotamia. The birth of writing started the period that we call “history,” in which events are written down and details of big events as well as daily life can easily be passed on. This tremendous change in human lifestyle can be called the Neolithic Revolution .

- Figure 6 - From the beginning to final evolution of cuneiform writing.

- Writing on argil support showed changes from pictograms to abstract design. Picture modified from British Museum. Dates in year BC.

From the time of Homo erectus , Homo species migrated out of Africa. Homo sapiens extended this migration over the whole planet. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Europeans explored the world. On the various continents, explorers met unknown populations. The Europeans were wondering if those beings were humans or not. But actually, those populations were also descendants of the men and women who colonized the earth at the dawn of mankind. In much earlier times, there was a theory that there were several races of humans, based mostly on skin color, but this theory was not supported by science. Current studies of DNA show that more than seven billion people who live on earth today are not of different races. There is only one human species on earth today, named Homo sapiens .

Suggested Reading

Species and Speciation. What defines a species? How new species can arise from existing species. https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/her/tree-of-life/a/species-speciation

Speciation : ↑ The formation of new and distinct species in the course of evolution.

Genus : ↑ In the classification of biology, a genus is a subdivision of a family. This subdivision is a grouping of living organisms having one or more related similarities. In the binomial nomenclature, the universally used scientific name of each organism is composed of its genus (capitalized) and a species identifier (lower case), for example Australopithecus afarensis, Homo sapiens.

Eurasia : ↑ A term used to describe the combined continental landmass of Europe and Asia.

Clay : ↑ Fine-grained earth that can be molded when wet and that is dried and baked to make pottery.

Revolution : ↑ Fundamental change occurring relatively quickly in human society.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Emma Clayton (Frontiers) for her advice and careful reading. Photo of Neanderthal statue was from Stephane Louryan, one of the designers of Neanderthal’s statue project [Faculty of Medicine, Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB), Brussels, Belgium].

[1] ↑ Godfraind, T. 2016. Hominisation et Transhumanisme . Bruxelles: Académie Royale de Belgique.

[2] ↑ Ward, C. V., Kimbel, W. H., and Johanson, D. C. 2011. Complete fourth metatarsal and arches in the foot of Australopithecus afarensis. Science 331:750–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1201463

[3] ↑ Harmand, S., Lewis, J. E., Feibel, C. S., Lepre, C. J., Prat, S., Lenoble, A., et al. 2015. 3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya. Nature 521:310–5. doi: 10.1038/nature14464

[4] ↑ Carotenuto, F., Tsikaridze, N., Rook, L., Lordkipanidze, D., Longo, L., Condemi, S., et al. 2016. Venturing out safely: the biogeography of Homo erectus dispersal out of Africa. J. Hum. Evol. 95:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.02.005

[5] ↑ Joordens, J. C., d’Errico, F., Wesselingh, F. P., Munro, S., de Vos, J., Wallinga, J., et al. 2015. Homo erectus at Trinil on Java used shells for tool production and engraving. Nature 518:228–31. doi: 10.1038/nature13962

[6] ↑ Arsuaga, J. L., Martinez, I., Arnold, L. J., Aranburu, A., Gracia-Tellez, A., Sharp, W. D., et al. 2014. Neandertal roots: cranial and chronological evidence from Sima de los Huesos. Science 344:1358–63. doi: 10.1126/science.1253958

[7] ↑ Vernot, B., Tucci, S., Kelso, J., Schraiber, J. G., Wolf, A. B., Gittelman, R. M., et al. 2016. Excavating Neandertal and Denisovan DNA from the genomes of Melanesian individuals. Science 352:235–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9416

[8] ↑ Richter, D., Grun, R., Joannes-Boyau, R., Steele, T. E., Amani, F., Rue, M., et al. 2017. The age of the hominin fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, and the origins of the Middle Stone Age. Nature 546:293–6. doi: 10.1038/nature22335

[9] ↑ Vyas, D. N., Al-Meeri, A., and Mulligan, C. J. 2017. Testing support for the northern and southern dispersal routes out of Africa: an analysis of Levantine and southern Arabian populations. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol . 164:736–49. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.23312

[10] ↑ Reyes-Centeno, H., Hubbe, M., Hanihara, T., Stringer, C., and Harvati, K. 2015. Testing modern human out-of-Africa dispersal models and implications for modern human origins. J. Hum. Evol . 87:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.06.008

[11] ↑ Templeton, A. 2002. Out of Africa again and again. Nature 416:45–51. doi: 10.1038/416045a

[12] ↑ Arnason, U. 2017. A phylogenetic view of the Out of Asia/Eurasia and Out of Africa hypotheses in the light of recent molecular and palaeontological finds. Gene 627:473–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.07.006

[13] ↑ Callaway, E. 2018. Israeli fossils are the oldest modern humans ever found outside of Africa. Nature 554:15–6. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-01261-5

[14] ↑ Benazzi, S., Douka, K., Fornai, C., Bauer, C. C., Kullmer, O., Svoboda, J., et al. 2011. Early dispersal of modern humans in Europe and implications for Neanderthal behaviour. Nature 479:525–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10617

[15] ↑ Vernot, B., and Akey, J. M. 2014. Resurrecting surviving Neandertal lineages from modern human genomes. Science 343:1017–21. doi: 10.1126/science.1245938

[16] ↑ Ollivier, M., Tresset, A., Frantz, L. A. F., Brehard, S., Balasescu, A., Mashkour, M., et al. 2018. Dogs accompanied humans during the Neolithic expansion into Europe. Biol. Lett. 14:20180286. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2018.0286

[17] ↑ Gerling, C., Doppler, T., Heyd, V., Knipper, C., Kuhn, T., Lehmann, M. F., et al. 2017. High-resolution isotopic evidence of specialised cattle herding in the European Neolithic. PLoS ONE 12:e0180164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180164

[18] ↑ Revedin, A., Aranguren, B., Becattini, R., Longo, L., Marconi, E., Lippi, M. M., et al. 2010. Thirty thousand-year-old evidence of plant food processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A . 107:18815–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006993107

Science and Creationism: A View from the National Academy of Sciences, Second Edition (1999)

Chapter: human evolution, human evolution.

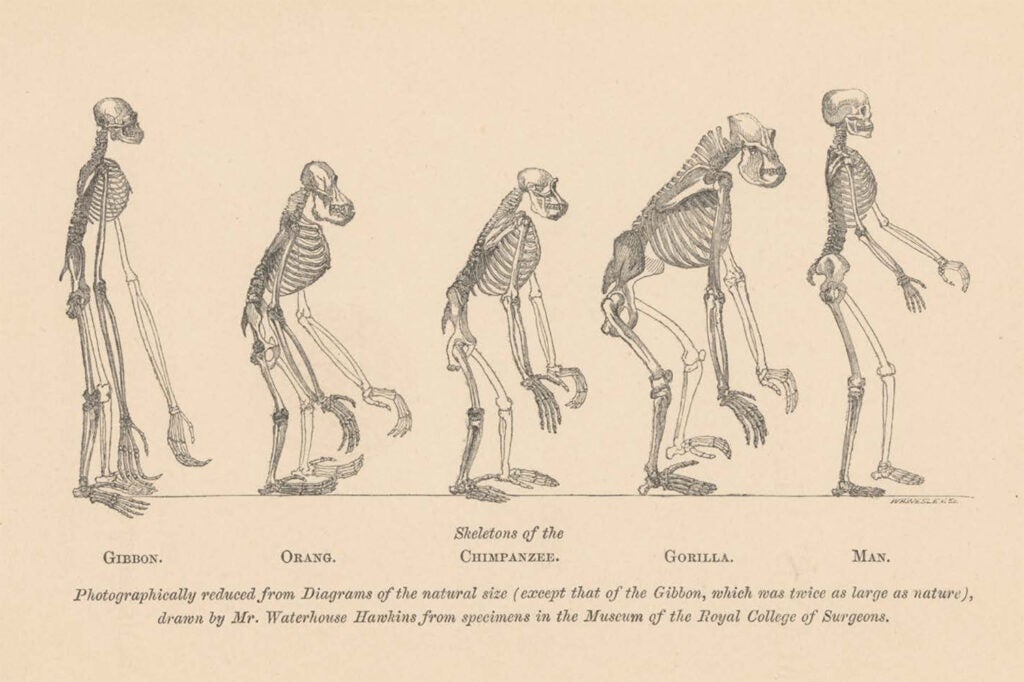

Studies in evolutionary biology have led to the conclusion that human beings arose from ancestral primates. This association was hotly debated among scientists in Darwin's day. But today there is no significant scientific doubt about the close evolutionary relationships among all primates, including humans.

Many of the most important advances in paleontology over the past century relate to the evolutionary history of humans. Not one but many connecting links—intermediate between and along various branches of the human family tree—have been found as fossils. These linking fossils occur in geological deposits of intermediate age. They document the time and rate at which primate and human evolution occurred.

Scientists have unearthed thousands of fossil specimens representing members of the human family. A great number of these cannot be assigned to the modem human species, Homo sapiens. Most of these specimens have been well dated, often by means of radiometric techniques. They reveal a well-branched tree, parts of which trace a general evolutionary sequence leading from ape-like forms to modem humans.

Paleontologists have discovered numerous species of extinct apes in rock strata that are older than four million years, but never a member of the human family at that great age. Australopithecus, whose earliest known fossils are about four million years old, is a genus with some features closer to apes and some closer to modem humans. In brain size, Australopithecus was barely more advanced than apes. A number of features, including long arms, short legs, intermediate toe structure, and features of the upper limb, indicate that the members of this species spent part of the time in trees. But they also walked upright on the ground, like humans. Bipedal tracks of Australopithecus have been discovered, beautifully preserved with those of other extinct animals, in hardened volcanic ash. Most of our Australopithecus ancestors died out close to two-and-a-half million years ago, while other Australopithecus species, which were on side branches of the human tree, survived alongside more advanced hominids for another million years.

Distinctive bones of the oldest species of the human genus, Homo, date back to rock strata about 2.4 million years old. Physical anthropologists agree that Homo evolved from one of the species of Australopithecus. By two million years ago, early members of Homo had an average brain size one-and-a-half times larger than that of Australopithecus, though still substantially smaller than that of modem humans. The shapes of the pelvic and leg bones suggest that these early Homo were not part-time climbers like Australopithecus but walked and ran on long legs, as modem humans do. Just as Australopithecus showed a complex of ape-like, human-like, and intermediate features, so was early Homo intermediate between Australopithecus and modem humans in some features, and dose to modem humans in other respects. The earliest

Early hominids, such as members of the Australopithecus afarensis species that lived about 3 million years ago, had smaller brains and larger faces than species belonging to the genus Homo, which first appeared about 2.4 million years ago. White parts of the skulls are reconstructions, and the skulls are not all on the same scale.

stone tools are of virtually the same age as the earliest fossils of Homo. Early Homo, with its larger brain than Australopithecus, was a maker of stone tools.

The fossil record for the interval between 2.4 million years ago and the present includes the skeletal remains of several species assigned to the genus Homo. The more recent species had larger brains than the older ones. This fossil record is complete enough to show that the human genus first spread from its place of origin in Africa to Europe and Asia a little less than two million years ago. Distinctive types of stone tools are associated with various populations. More recent species with larger brains generally used more sophisticated tools than more ancient species.

Molecular biology also has provided strong evidence of the close relationship between humans and apes. Analysis of many proteins and genes has shown that humans are genetically similar to chimpanzees and gorillas and less similar to orangutans and other primates.

DNA has even been extracted from a well-preserved skeleton of the extinct human creature known as Neanderthal, a member of the genus Homo and often considered either as a subspecies of Homo sapiens or as a separate species. Application of the molecular clock, which makes use of known rates of genetic mutation, suggests that Neanderthal's lineage diverged from that of modem Homo sapiens less than half a million years ago, which is entirely compatible with evidence from the fossil record.

Based on molecular and genetic data, evolutionists favor the hypothesis that modem Homo sapiens, individuals very much like us, evolved from more archaic humans about 100,000 to 150,000 years ago. They also believe that this transition occurred in Africa, with modem humans then dispersing to Asia, Europe, and eventually Australasia and the Americas.

Discoveries of hominid remains during the past three decades in East and South Africa, the Middle East, and elsewhere have combined with advances in molecular biology to initiate a new discipline—molecular paleoanthropology. This field of inquiry is providing an ever-growing inventory of evidence for a genetic affinity between human beings and the African apes.

Opinion polls show that many people believe that divine intervention actively guided the evolution of human beings. Science cannot comment on the role that supernatural forces might play in human affairs. But scientific investigations have concluded that the same forces responsible for the evolution of all other life forms on Earth can account for the evolution of human beings.

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Books Received

- Published: 08 June 1946

Essays on Human Evolution

- A. D. RITCHIE

Nature volume 157 , pages 749–750 ( 1946 ) Cite this article

48 Accesses

Metrics details