Types of Point of View: The Ultimate Guide to First Person and Third Person POV

by Joe Bunting | 72 comments

In my experience as an editor, point of view problems are among the top mistakes I see new writers make, and they instantly erode credibility and reader trust. Point of view isn't easy though, since there are so many to choose from: first person point of view, third person limited, third person omniscient, and second person.

What do those even mean? And how do you choose the right one for your story?

All stories are written from a point of view. However, when point of view goes wrong—and believe me, it goes wrong often—you threaten whatever trust you have with your reader. You also fracture their suspension of disbelief.

However, point of view is simple to master if you use common sense.

This post will define point of view, go over each of the major POVs, explain a few of the POV rules, and then point out the major pitfalls writers make when dealing with that point of view.

Table of Contents

Point of View Definition The 4 Types of Point of View The #1 POV Mistake First Person Point of View Second Person Point of View Third Person Limited Point of View Third Person Omniscient Point of View FAQ: Can you change POV in a Series? Practice Exercise

Point of View Definition

The point of view, or POV, in a story is the narrator's position in the description of events, and comes from the Latin word, punctum visus , which literally means point sight. The point of view is where a writer points the sight of the reader.

Note that point of view also has a second definition.

In a discussion, an argument, or nonfiction writing, a point of view is an opinion about a subject. This is not the type of point of view we're going to focus on in this article (although it is helpful for nonfiction writers, and for more information, I recommend checking out Wikipedia's neutral point of view policy ).

I especially like the German word for POV, which is Gesichtspunkt , translated “face point,” or where your face is pointed. Isn't that a good visual for what's involved in point of view? It's the limited perspective of what you show your reader.

Note too that point of view is sometimes called narrative mode or narrative perspective.

Why Point of View Is So Important

Why does point of view matter so much?

For a fiction writer, point of view filters everything in your story. Everything in your story must come from a point of view.

Which means if you get it wrong, your entire story is damaged.

For example, I've personally read and judged thousands of stories for literary contests, and I've found point of view mistakes in about twenty percent of them. Many of these stories would have placed much higher if only the writers hadn't made the mistakes we're going to talk about soon.

The worst part is these mistakes are easily avoidable if you're aware of them. But before we get into the common point of view mistakes, let's go over each of the four types of narrative perspective.

The Four Types of Point of View

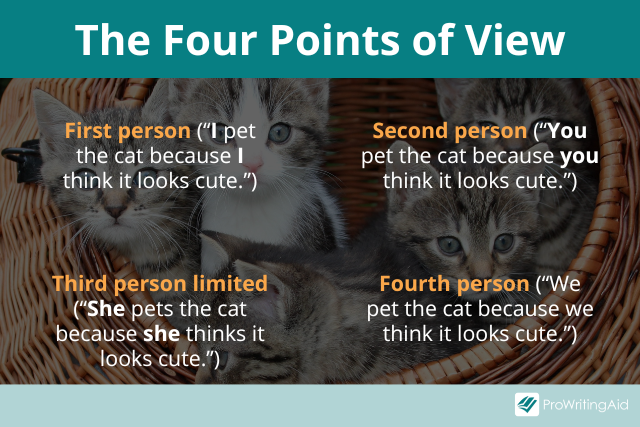

Here are the four primary types of narration in fiction:

- First person point of view. First person perspective is when “I” am telling the story. The character is in the story, relating his or her experiences directly.

- Second person point of view. The story is told to “you.” This POV is not common in fiction, but it's still good to know (it is common in nonfiction).

- Third person point of view, limited. The story is about “he” or “she.” This is the most common point of view in commercial fiction. The narrator is outside of the story and relating the experiences of a character.

- Third person point of view, omniscient. The story is still about “he” or “she,” but the narrator has full access to the thoughts and experiences of all characters in the story. This is a much broader perspective.

I know you've seen and probably even used most of these point of views.

While these are the only types of POV, there are additional narrative techniques you can use to tell an interesting story. To learn how to use devices like epistolary and framing stories, check out our full narrative devices guide here .

Let's discuss each of the four types, using examples to see how they affect your story. We'll also go over the rules for each type, but first let me explain the big mistake you don't want to make with point of view.

The #1 POV Mistake

Do not begin your story with a first person narrator and then switch to a third person narrator. Do not start with third person limited and then abruptly give your narrator full omniscience. This is the most common type of error I see writers make with POV.

The guideline I learned in my first creative writing class in college is a good one:

Establish the point of view within the first two paragraphs of your story.

And above all, don't change your point of view . If you do, it creates a jarring experience for the reader and you'll threaten your reader's trust. You could even fracture the architecture of your story.

That being said, as long as you're consistent, you can sometimes get away with using multiple POV types. This isn't easy and isn't recommended, but for example, one of my favorite stories, a 7,000 page web serial called Worm , uses two point of views—first person with interludes of third-person limited—very effectively. (By the way, if you're looking for a novel to read over the next two to six months, I highly recommend it—here's the link to read for free online .) The first time the author switched point of views, he nearly lost my trust. However, he kept this dual-POV consistent over 7,000 pages and made it work.

Whatever point of view choices you make, be consistent. Your readers will thank you!

Now, let's go into detail on each of the four narrative perspective types, their best practices, and mistakes to avoid.

First Person Point of View

In first person point of view, the narrator is in the story and telling the events he or she is personally experiencing.

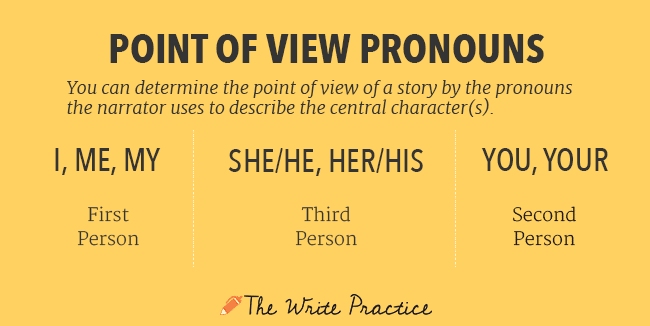

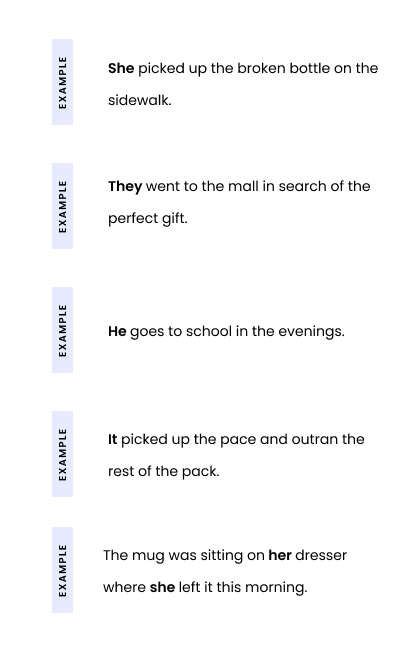

The simplest way to understand first person is that the narrative will use first-person pronouns like I, me, and my.

Here's a first person point of view example from Herman Melville's Moby Dick :

Call me Ishmael. Some years ago—never mind how long precisely—having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world

First person narrative perspective is one of the most common POVs in fiction. If you haven't read a book in first person point of view, you haven't been reading.

What makes this point of view interesting, and challenging, is that all of the events in the story are filtered through the narrator and explained in his or her own unique narrative voice.

This means first person narrative is both biased and incomplete, but it can also deliver a level of intimacy other POVs can't.

Other first person point of view examples can be found in these popular novels :

- The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway

- Twilight by Stephenie Meyer

- Ready Player One by Ernest Cline

- The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brönte

First Person Narrative is Unique to Writing

There's no such thing as first person in film or theater—although voiceovers and mockumentary interviews like the ones in The Office and Modern Family provide a level of first person narrative in third person perspective film and television.

In fact, the very first novels were written in first person, modeled after popular journals and autobiographies which were first-person stories of nonfiction..

First Person Point of View is Limited

First person narrators are narrated from a single character's perspective at a time. They cannot be everywhere at once and thus cannot get all sides of the story.

They are telling their story, not necessarily the story.

First Person Point of View is Biased

In first person novels, the reader almost always sympathizes with a first person narrator, even if the narrator is an anti-hero with major flaws.

Of course, this is why we love first person narrative, because it's imbued with the character's personality, their unique perspective on the world.

The most extreme use of this bias is called an unreliable narrator. Unreliable narration is a technique used by novelists to surprise the reader by capitalize on the limitations of first person narration to make the narrator's version of events extremely prejudicial to their side and/or highly separated from reality.

You'll notice this form of narration being used when you, as the reader or audience, discover that you can't trust the narrator.

For example, Gillian Flynn's Gone Girl pits two unreliable narrators against one another. Each relates their conflicting version of events, one through typical narration and the other through journal entries. Another example is Fight Club , in which *SPOILER* the narrator has a split personality and imagines another character who drives the plot.

Other Interesting Uses of First Person Narrative:

- The classic novel Heart of Darkness is actually a first person narrative within a first person narrative. The narrator recounts verbatim the story Charles Marlow tells about his trip up the Congo river while they sit at port in England.

- William Faulkner's Absalom, Absalom is told from the first person point of view of Quentin Compson; however, most of the story is a third person account of Thomas Sutpen, his grandfather, as told to Quentin by Rosa Coldfield. Yes, it's just as complicated as it sounds!

- Salman Rushdie's award-winning Midnight's Children is told in first person, but spends most of the first several hundred pages giving a precise third person account of the narrator's ancestors. It's still first person, just a first person narrator telling a story about someone else.

Two Big Mistakes Writers Make with First Person Point of View

When writing in first person, there are two major mistakes writers make :

1. The narrator isn't likable. Your protagonist doesn't have to be a cliché hero. She doesn't even need to be good. However, she must be interesting .

The audience will not stick around for 300 pages listening to a character they don't enjoy. This is one reason why anti-heroes make great first person narrators.

They may not be morally perfect, but they're almost always interesting. (Remember Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye ?)

2. The narrator tells but doesn't show. The danger with first person is that you could spend too much time in your character's head, explaining what he's thinking and how he feels about the situation.

You're allowed to mention the character's mood, but don't forget that your reader's trust and attention relies on what your character does , not what he thinks about doing.

Second Person Point of View

While not used often in fiction—it is used regularly in nonfiction, song lyrics, and even video games—second person POV is still helpful to understand.

In this point of view, the narrator relates the experiences using second person pronouns like you and your. Thus, you become the protagonist, you carry the plot, and your fate determines the story.

We've written elsewhere about why you should try writing in second person , but in short we like second person because it:

- Pulls the reader into the action of the story

- Makes the story personal

- Surprises the reader

- Stretches your skills as a writer

Here's an example from the breakout bestseller Bright Lights, Big City by Jay Mclnerney (probably the most popular example that uses second person point of view):

You have friends who actually care about you and speak the language of the inner self. You have avoided them of late. Your soul is as disheveled as your apartment, and until you can clean it up a little you don't want to invite anyone inside.

Second person narration isn't used frequently, however there are some notable examples of it.

Some other novels that use second person point of view are:

- Remember the Choose Your Own Adventure series? If you've ever read one of these novels where you get to decide the fate of the character (I always killed my character, unfortunately), you've read second person narrative.

- The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemison

- The opening of The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern

There are also many experimental novels and short stories that use second person, and writers such as William Faulkner, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Albert Camus played with the style.

Breaking the fourth wall:

In the plays of William Shakespeare, a character will sometimes turn toward the audience and speak directly to them. In A Midsummer Night's Dream , Puck says:

If we shadows have offended, think but this, and all is mended, that you have but slumbered here while these visions did appear.

This narrative device of speaking directly to the audience or the reader is called breaking the fourth wall (the other three walls being the setting of the story).

To think of it another way, it's a way the writer can briefly use second person in a first or third person narrative.

It's a lot of fun! You should try it.

Third Person Point of View

In third person narration, the narrator is outside of the story and relating the experiences of a character.

The central character is not the narrator. In fact, the narrator is not present in the story at all.

The simplest way to understand third person narration is that it uses third-person pronouns, like he/she, his/hers, they/theirs.

There are two types of this point of view:

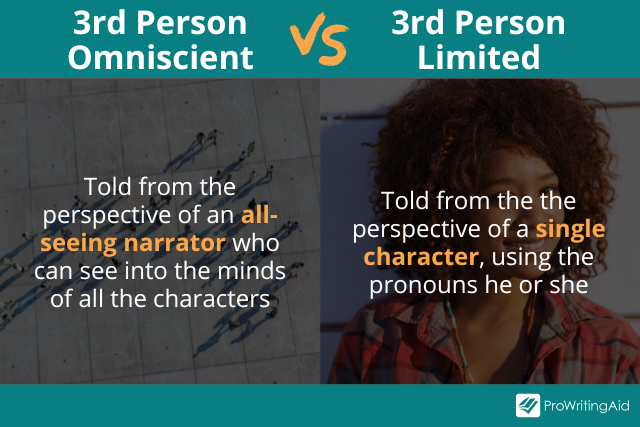

Third Person Omniscient

The all-knowing narrator has full access to all the thoughts and experiences of all the characters in the story.

Examples of Third Person Omniscient:

While much less common today, third person omniscient narration was once the predominant type, used by most classic authors. Here are some of the novels using omniscient perspective today.

- War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

- Middlemarch by George Eliot

- Where the Crawdad's Sing by Delia Owens

- The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway

- Still Life by Louise Penny (and all the Inspector Gamache series, which is amazing, by the way)

- Gossip Girl by Cecily von Ziegesar

- Strange the Dreamer by Laini Taylor

- Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

- Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan (one of my favorites!)

- A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula Le Guin

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

- More third person omniscient examples can be found here

Third Person Limited

The narrator has only some, if any, access to the thoughts and experiences of the characters in the story, often just to one character .

Examples of Third Person Limited

Here's an example of a third person limited narrator from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone by J.K. Rowling:

A breeze ruffled the neat hedges of Privet Drive, which lay silent and tidy under the inky sky, the very last place you would expect astonishing things to happen. Harry Potter rolled over inside his blankets without waking up. One small hand closed on the letter beside him and he slept on, not knowing he was special, not knowing he was famous…. He couldn't know that at this very moment, people meeting in secret all over the country were holding up their glasses and saying in hushed voices: “To Harry Potter—the boy who lived!”

Some other examples of third person limited narration include:

- Game of Thrones s eries by George R.R. Martin (this has an ensemble cast, but Martin stays in one character's point of view at a time, making it a clear example of limited POV with multiple viewpoint characters, which we'll talk about in just a moment)

- For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway

- The Way of Kings by Brandon Sanderson

- The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown

- The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Larsson

- Ulysses by James Joyce

- Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

- 1984 by George Orwell

- Orphan Train by Christina Baker Kline

- Fates and Furies by Lauren Groff

Should You Use Multiple Viewpoint Characters vs. a Single Perspective?

One feature of third person limited and first person narrative is that you have the option of having multiple viewpoint characters.

A viewpoint character is simply the character whose thoughts the reader has access to. This character become the focus of the perspective during the section of story or the story as a whole.

While it increases the difficulty, you can have multiple viewpoint characters for each narrative. For example, Game of Thrones has more than a dozen viewpoint characters throughout the series. Fifth Season has three viewpoint characters. Most romance novels have at least two viewpoint characters.

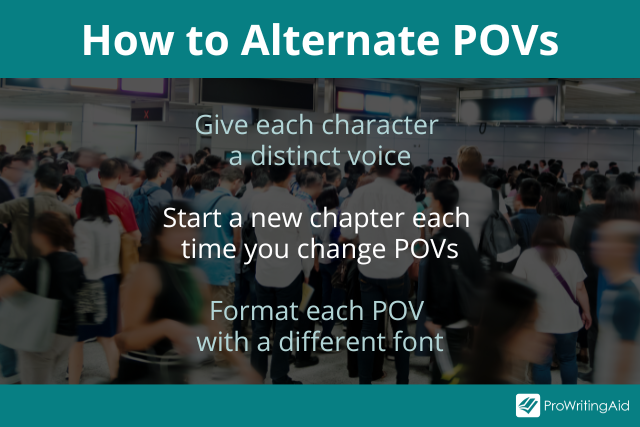

The rule is to only focus on one viewpoint character at a time (or else it changes to third person omniscient).

Usually authors with multiple viewpoint characters will change viewpoints every chapter. Some will change after section breaks. However, make sure there is some kind of break before changing so as to prepare the reader for the shift.

Should You Use Third Person Omniscient or Third Person Limited

The distinction between third persons limited and omniscient is messy and somewhat artificial.

Full omniscience in novels is rare—it's almost always limited in some way—if only because the human mind isn't comfortable handling all the thoughts and emotions of multiple people at once.

The most important consideration in third person point of view is this:

How omniscient are you going to be? How deep are you going to go into your character's mind? Will you read their thoughts frequently and deeply at any chance? Or will you rarely, if ever, delve into their emotions?

To see this question in action, imagine a couple having an argument.

Tina wants Fred to go to the store to pickup the cilantro she forgot she needed for the meal she's cooking. Fred is frustrated that she didn't ask him to pick up the cilantro on the way home from the office, before he had changed into his “homey” clothes (AKA boxer shorts).

If the narrator is fully omniscient, do you parse both Fred and Tina's emotions during each back and forth?

“Do you want to eat ? If you do, then you need to get cilantro instead of acting like a lazy pig,” Tina said, thinking, I can't believe I married this jerk. At least back then he had a six pack, not this hairy potbelly . “Figure it out, Tina. I'm sick of rushing to the store every time you forget something,” said Fred. He felt the anger pulsing through his large belly.

Going back and forth between multiple characters' emotions like this can give a reader whiplash, especially if this pattern continued over several pages and with more than two characters. This is an example of an omniscient narrator who perhaps is a little too comfortable explaining the characters' inner workings.

“ Show, don't tell ,” we're told. Sharing all the emotions of all your characters can become distraction. It can even destroy any tension you've built.

Drama requires mystery. If the reader knows each character's emotions all the time, there will be no space for drama.

How do You Handle Third Person Omniscient Well?

The way many editors and many famous authors handle this is to show the thoughts and emotions of only one character per scene (or per chapter).

George R.R. Martin, for example, uses “ point of view characters ,” characters whom he always has full access to understanding. He will write a full chapter from their perspective before switching to the next point of view character.

For the rest of the cast, he stays out of their heads.

This is an effective guideline, if not a strict rule, and it's one I would suggest to any first-time author experimenting with third person narrative. Overall, though, the principle to show, don't tell should be your guide.

The Biggest Third Person Omniscient Point of View Mistake

The biggest mistake I see writers make constantly in third person is head hopping .

When you switch point of view characters too quickly, or dive into the heads of too many characters at once, you could be in danger of what editors call “head hopping.”

When the narrator switches from one character’s thoughts to another’s too quickly, it can jar the reader and break the intimacy with the scene’s main character.

We've written about how you can get away with head hopping elsewhere , but it's a good idea to try to avoid going into more than one character's thoughts per scene or per chapter.

Can You Change POV Between Books In a Series?

What if you're writing a novel series? Can you change point of view or even POV characters between books?

The answer is yes, you can, but whether you should or not is the big question.

In general, it's best to keep your POV consistent within the same series. However, there are many examples of series that have altered perspectives or POV characters between series, either because the character in the previous books has died, for other plot reasons, or simply because of author choice.

For more on this, watch this coaching video where we get into how and why to change POV characters between books in a series:

Which Point of View Will You Use?

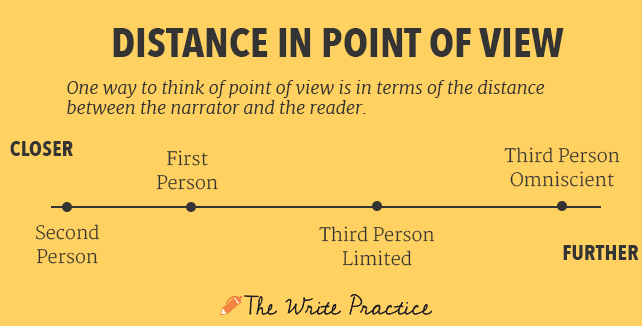

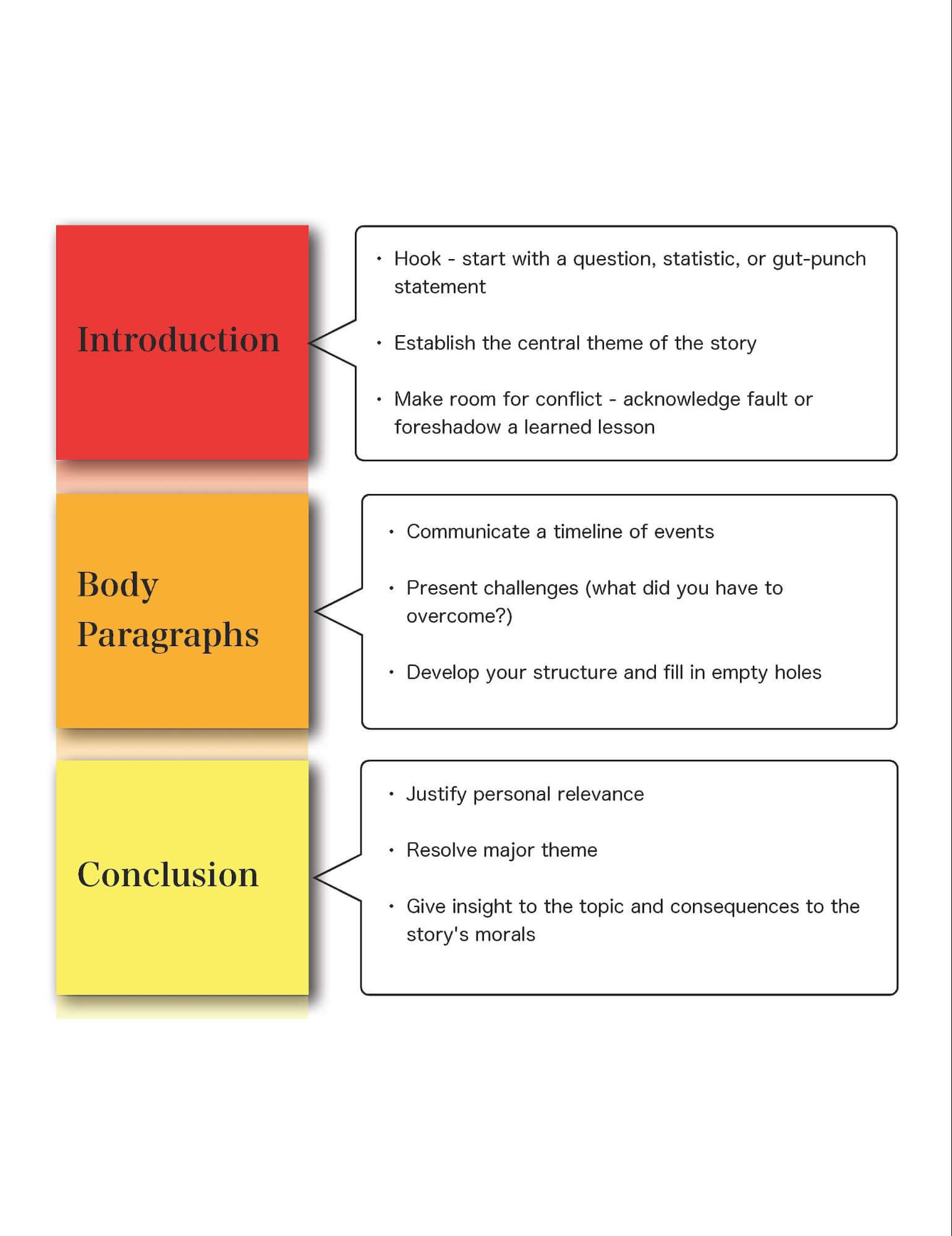

Here's a helpful point of view infographic to help you decide which POV to use in your writing:

Note that these distances should be thought of as ranges, not precise calculations. A third person narrator could conceivably draw closer to the reader than a first person narrator.

Most importantly, there is no best point of view. All of these points of view are effective in various types of stories.

If you're just getting started, I would encourage you to use either first person or third person limited point of view because they're easy to understand.

However, that shouldn't stop you from experimenting. After all, you'll only get comfortable with other points of view by trying them!

Whatever you choose, be consistent. Avoid the mistakes I mentioned under each point of view.

And above all, have fun!

How about you? Which of the four points of view have you used in your writing? Why did you use it, and what did you like about it? Share in the comments .

Using a point of view you've never used before, write a brief story about a teenager who has just discovered he or she has superpowers.

Make sure to avoid the POV mistakes listed in the article above.

Write for fifteen minutes . When your time is up, post your practice in the Pro Practice Workshop (if you’re not a member yet, you can join here ). And if you post, please be sure to give feedback to your fellow writers.

We can gain just as much value giving feedback as we can writing our own books!

Happy writing!

Joe Bunting

Joe Bunting is an author and the leader of The Write Practice community. He is also the author of the new book Crowdsourcing Paris , a real life adventure story set in France. It was a #1 New Release on Amazon. Follow him on Instagram (@jhbunting).

Want best-seller coaching? Book Joe here.

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

Now, Take Your Idea and Write a Book!

Enter your email to get a free 3-step worksheet and start writing your book in just a few minutes.

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

Get the POV Cheatsheet for Writers

Enter your email for a free cheatsheet for the top two point of views!

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Looking to publish? Meet your dream editor, designer and marketer on Reedsy.

Find the perfect editor for your next book

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Nov 14, 2022

Point of View: The Ultimate Guide to Writing Perspectives

Point of view (POV) is the narrative perspective from which a story is told. It’s the angle from which readers experience the plot, observe the characters’ behavior, and learn about their world. In fiction, there are four types of point of view: first person, second person, third person limited, and third person omniscient.

This guide will look at each point of view, and provide examples to help you understand them better. Let’s dive in.

Which POV is right for your book?

Take our quiz to find out! Takes only 1 minute.

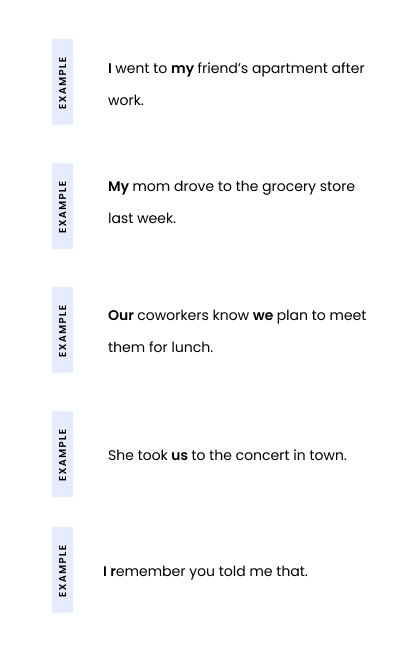

First person

First person narratives are quite common and relatively intuitive to write: it’s how we tell stories in everyday life. Sentences written in first person will use the pronouns I , we , my , and our . For example:

I told my mother that we lost our passports.

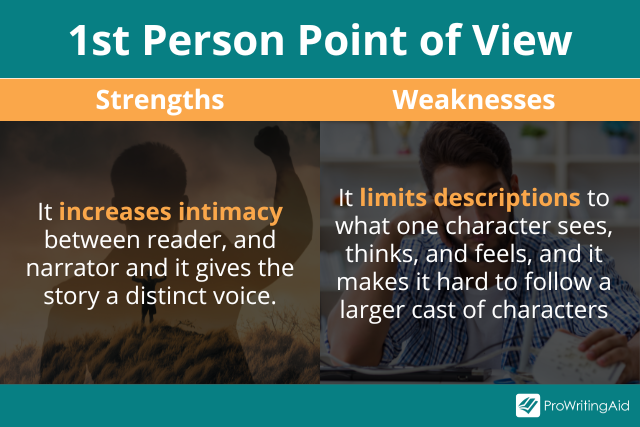

First person can create intimacy between the reader and the characters, granting us direct access to their emotions, psyches and inner thoughts. In stories where the protagonist’s internal life is at the fore, you will often find a first-person narrator.

FREE COURSE

Understanding Point of View

Learn to master different POVs and choose the best for your story.

Having a single fixed narrator can limit the scope of a story 一 the reader can only know what the narrator knows. It’s also said that a first person narrator is biased, since they provide a subjective view of the world around them, rather than an objective one. Of course, this isn’t necessarily a bad thing, and intentionally unreliable narrators are fascinating literary creatures in their own right.

Genres that commonly use a first person POV

Young Adult . Introspective coming-of-age narratives often benefit from a first-person narrative that captures the protagonist’s voice and (often mortifying) internal anxieties. Some examples are novels like The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins , The Fault in Our Stars by John Green , and The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger.

Science Fiction . In sci-fi novels, a first person perspective can nicely convey the tension and awe associated with exploring unfamiliar environments and technologies. Some examples of this approach include Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir, Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes, and Ready Player One by Ernest Cline.

Memoir . The first person is perfect for memoirs, which allow readers to relive life events with the author. Some pageturners in this genre are Open by Andre Agassi, Educated by Tara Westover, and Becoming by Michelle Obama.

As you might expect, after first person comes…

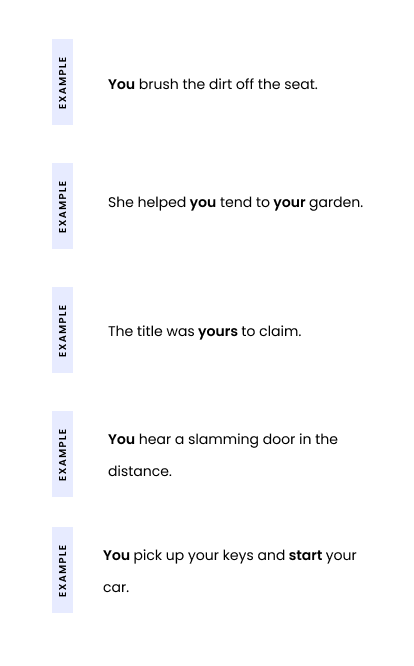

Second person

Second person narratives are far less common in literature — but not entirely unheard of. The pronouns associated with second person include you , your , and yours , as in:

You instruct the chief of police to bring the prisoner to your office.

Second person POV is all about putting the reader directly in the headspace of a particular character: either the protagonist or a secondary figure. When mishandled, this POV can alienate readers — but when executed well, it can create an intimate reading experience like no other.

Since this POV requires quite a lot of focus for most readers, it’s often suited to shorter, lyrical pieces of writing, like poetry. It can also be used alongside other points of view to provide variety in a longer novel, or to indicate a change of character (see: The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin).

GET ACCOUNTABILITY

Meet writing coaches on Reedsy

Industry insiders can help you hone your craft, finish your draft, and get published.

Genres that commonly use a second person POV

Creative Fiction . Short stories, poetry, and screenplays can benefit from the immediacy and intimacy of the second person. Two examples are The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz, or Pants are Optional by Aeris Walker 一 a brilliant piece from Reedsy’s Short Story competition.

Nonfiction . In self-help in particular, the second person can be used to ‘enter the reader's mind’, establish rapport, and guide them through a transformation process. For example, in Eckhart Tolle's The Power of Now many teachings are conveyed through a series of questions and answers written in second person.

Now that you have seen how second person narratives work, let’s meet some third person limited narrators and see how they handle things.

Third person limited

Everyone has read a third person limited narrative, as literature is full of them. This POV uses third-person pronouns such as he , his , she , hers , they , their , to relate the story:

She told him that their assessment of the situation was incorrect.

Third person limited is where the narrator can only reveal the thoughts, feelings, and understanding of a single character at any given time — hence, the reader is “limited” to that perspective. Between chapters, many books wrote in this POV switch from character to character, but you will only hear one perspective at a time. For instance:

“ She couldn't tell if the witness was lying.”

The limited third person POV portrays characters from a bit of distance, and asks the readers to engage and choose who they’re rooting for 一 but this POV poses a challenge for authors when trying to create truly compelling characters . A limited perspective definitely adds intrigue, but writers should bear in mind that being able to tell only one side of the story at a time can limit their ability to reveal important details.

Genres that commonly use a third person limited POV

Romance . A love story always has two sides, and the third person point of view is ideal for authors who wish to convey both. Examples in this genre include Shadow and Bone by Leigh Bardugo, Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell, and The Grand Sophy by Georgette Heyer.

Thriller . In suspense-driven plots the limited third person POV works well, since it’s fun to try and solve a mystery (or mysterious characters) alongside the protagonists. Two examples are Murder on the Orient Express by Agatha Christie, or Nine Perfect Strangers by Moriarty Liane.

A solid story structure will help you maintain a coherent point of view. Build it with our free book development template.

FREE RESOURCE

Get our Book Development Template

Use this template to go from a vague idea to a solid plan for a first draft.

If you’re done with the intimacy of “close” viewpoints, perhaps we can interest you in one final POV — a God’s-eye view of storytelling.

Third person Omniscient

The third person omniscient is as popular as the limited one, and uses the same pronouns. The difference, however, is that the narrator is “all knowing” — meaning that they’re not limited to one character’s perspective, but instead can reveal anything that is happening, has happened, or will happen in the world of the story. For example:

He thought the witness was honest, but she didn't think the same of him .

It’s a popular point of view because it allows a writer to pan out beyond the perspective of a single character, so that new information (beyond the protagonist’s comprehension) can be introduced. At the same time, it heavily relies on the voice and authority of the narrator, and can therefore take some focus away from the character.

Genres that commonly use a third person omniscient POV

Fantasy fiction . In elaborate fantasy worlds, being unencumbered from a character’s personal narrative means that the narrator can provide commentary on the world, or move between characters and locations with the flick of a pen. You’ll see this approach in action in Reaper Man by Terry Pratchett, Howl's Moving Castle by Diana Wynne Jones, and The Chronicles of Narnia by C. S. Lewis.

Literary fiction . An all-encompassing perspective can allow authors to explore different character quirks, but also interpersonal dynamics between characters. Leo Tolstoy does this masterfully in his great classics Anna Karenina and War and Peace .

Now that we have established the basics of the major points of view, let’s dig a little deeper. If you’re ready for a closer look at POV, head over to the next post in this guide to learn more about first person perspective.

5 responses

Aysha says:

19/04/2020 – 19:56

The Book Thief would be considered First Person POV, similar to Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes, right? Thank you for the wonderful information. It gave a lot of insight into choosing which POV would be most suitable for a particular story. Pretty clear-cut.

Sasha Anderson says:

31/05/2020 – 10:41

I sometimes have difficulty telling the difference between third person limited and omniscient. For example, in the quote from I am Legend, the sentence "If he had been more analytical, he might have calculated the approximate time of their arrival" sounds very omniscient to me, because Robert wasn't, and didn't. Is there an easy way to tell that this is limited rather than omniscient, or does it not really matter as long as it reads well?

Lilian says:

18/06/2020 – 05:15

This was a very helpful piece and I hope it's okay to share the link for reference.

↪️ Martin Cavannagh replied:

18/06/2020 – 08:51

Of course! Share away :)

18/06/2020 – 05:44

It deal with the challenges associated with POV in writing. I like that it clearly distinguishes between third person limited POV and third person omniscient POV as most beginner writers are guilty of abrupt and inconsistent interchange in the two leading to head hopping. Greattach piece, I muse confess.

Comments are currently closed.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Choose the right POV. The first time.

Demystify the secrets of writing in different points of view with this guide for writers.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Point of View

Point of View Definition

What is point of view? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

Point of view refers to the perspective that the narrator holds in relation to the events of the story. The three primary points of view are first person , in which the narrator tells a story from their own perspective ("I went to the store"); second person , in which the narrator tells a story about you, the reader or viewer ("You went to the store"); and third person , in which the narrator tells a story about other people ("He went to the store"). Each point of view creates a different experience for the reader, because, in each point of view, different types and amounts of information are available to the reader about the story's events and characters.

Some additional key details about point of view:

- Each different point of view has its own specific qualities that influence the narrative. It's up to the author to choose which point of view is best for narrating the story he or she is writing.

- Second person point of view is extremely rare in literature. The vast majority of stories are written in either the first or third person.

- You may hear "point of view" referred to simply as "perspective." This isn't wrong, it's just another way of referring to the same thing.

The Three "Modes" of Point of View

Stories can be told from one of three main points of view: first person, second person, or third person. Each of the different modes offers an author particular options and benefits, and the point of view that an author chooses will have a tremendous impact on the way that a reader engages with a story.

First Person Point of View

In first person point of view, the narrator tells the story from his or her own perspective. You can easily recognize first person by its use of the pronouns "I" or "We." First person offers the author a great way to give the reader direct access to a particular character's thoughts, emotions, voice, and way of seeing the world—their point of view about the main events of the story. The choice of which character gets to have first person point of view can dramatically change a story, as shown in this simple scenario of a thief snatching a lady's purse

- Thief's POV: "I was desperate for something to eat. Judging by her expensive-looking shoes, I figured she could afford to part with her purse."

- Victim's POV: "He came out of nowhere! Too bad for him, though: I only had five dollars in my bag."

Consider also one of the most famous examples of first person point of view, the very first line of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick :

Call me Ishmael.

Melville uses first person here because he wants to establish a confessional tone for the protagonist. He wants the reader to feel like Ishmael has just sat down next to him on a bar stool, and is about to tell him his life's story. Only first person can have this colloquial and intimate effect. Saying, "His name was Ishmael," for instance, would insert more distance between the reader and the character Ishmael, because the third person narrator would sit between the reader and Ishmael. First person, in this way, can have the effect of connecting the reader directly with the story.

First Person Point of View and the Protagonist

In a story told in the first person, the character who acts as narrator will often also be the protagonist of the story. However, some stories told from the first person do not make the narrator the protagonist:

- First person in which the narrator is the protagonist: In The Catcher in the Rye , the first person narrator Holden Caulfield is the clear protagonist of the story. His voice dominates the story, and the story he tells is his own.

- First person in which the narrator is not the protagonist: The novel The Great Gatsby is narrated by Nick Carraway, but the protagonist of the novel is Jay Gatsby. Nick Carraway tells the story, and the reader is limited to understanding the story through what Nick himself sees, knows, and thinks, but nevertheless the story that Nick tells is not his own but rather Gatsby's.

Second Person Point of View

Second person point of view uses the pronoun "you" to immerse the reader in the experience of being the protagonist. It's important to remember that second person point of view is different from simply addressing the reader. Rather, the second person point of view places the reader "on the playing field" by putting them in the position of the protagonist—the one to whom the action occurs. Few stories are appropriate for such a perspective, but occasionally it is quite successful, as in Jay McInerney's Bright Lights, Big City , a novel in which the reader is taken on a wild night through Manhattan.

Eventually you ascend the stairs to the street. You think of Plato's pilgrims climbing out of the cave, from the shadow world of appearances toward things as they really are, and you wonder if it is possible to change in this life. Being with a philosopher makes you think.

Of the three points of view, second person is the most rarely used, primarily because it doesn't allow the narrator as much freedom as first person and third person, so it's hard to sustain this style of narration for very long.

Third Person Point of View

In third person point of view, the narrator is someone (or some entity) who is not a character in the story being told. Third person point of view uses the pronouns "he," "she," and "they," to refer to all the characters. It is the most common point of view in writing, as it gives the writer a considerable amount of freedom to focus on different people, events, and places without being limited within the consciousness of a single character. Below is an example of dialogue written in third person by Joseph Heller in his novel Catch-22 :

"What are you doing?" Yossarian asked guardedly when he entered the tent, although he saw at once. "There's a leak here," Orr said. "I'm trying to fix it." "Please stop it," said Yossarian. "You're making me nervous."

The exchange above is narrated by a narrator who is outside the interaction between Yossarian and Orr; such distance is the hallmark of third person point of view.

Third Person and Degree of Distance

The third person mode is unique from first and second person in another way as well: third person has different variants. These variants depend on how far removed the narrator is from the events of the story, and how much the narrator knows about each character:

- Third Person Omniscient Point of View: "Third person omniscient" means that the narrator knows all the thoughts and feelings of every character and can dip in and out of the the internal life of anyone, as needed. Omniscient just means "all-knowing." This type of narrator is more god-like than human, in the sense that their perspective is un limited.

- A story like Young Goodman Brown , which follows one character closely and reports on that character's thoughts and feelings (but not the thoughts and feelings of others), is an example of third person limited point of view. This type of story gives the reader the feeling that they are inside one person's head without using first person pronouns like "I."

Alternating Point of View

Many stories are told from alternating points of view—switching between different characters, or even between different modes of storytelling.

- Stories can switch between third person points of view: Many novels switch between different third person points of view. For instance, the chapters of George R.R. Martin's The Song of Ice and Fire books are all named after characters, and each chapter is told from the limited third person point of view of the named character.

- Stories can switch between first person points of view: William Faulkner's novel As I Lay Dying is structurally similar to the Song of Ice and Fire books in the sense that each chapter is named after a character. However, each chapter is told in the first person by the named character. The Darl chapters are told in the first person by Darl, the Cash chapter are narrated by Cash, the Vardamon chapters by Vardamon, and so on.

- Stories can even switch between modes of storytelling: Though less common than other sorts of alternating points of view, some stories can shift not only between different character's points of view, but between actual modes of storytelling. For example, Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury has four parts. The first three parts are all narrated in the first person, with the first part narrated by Benjy, the second part by Quentin, and the third part by Jason. But the fourth part is told in the third person omniscient and follows a bunch of different characters at different times.

Point of View Examples

Every work of literature has a point of view, and so there are essentially endless examples of point of view in literature. The examples below were chosen because they are good examples of the different modes, and in the case of The Metamorphosis the the subtle shift in the nature of the narrator's point of view also shows how an author can play with point of view to suit the themes and ideas of a story.

Third Person Point of View in Kafka's Metamorphosis

A great example of third person point of view in literature is the first line from Kafka's The Metamorphosis .

As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.

For the remainder of the book, Kafka follows the protagonist, Gregor Samsa, in a limited third person point of view as he struggles to come to terms with his sudden transformation into an insect. For as long as Gregor remains alive, the third person narrator remains limited by Gregor's own consciousness—the story is told in the third person, but the narrator never knows or sees any more than Gregor himself does.

However, in the few pages of the story that continue after Gregor dies, the narrator shifts into a third person omniscient point of view , almost as if Gregor's death has freed the narrator in a way not so dissimilar to how his death tragically relieves a burden on his family.

Point of View in Tolstoy's Anna Karenina

Leo Tolstoy's Anna Karenina is a great example of the omniscient third person point of view. In the novel, the narrator sees and knows all, and moves around between the lives of the different characters, dipping into their internal lives and thoughts, and commenting on the narrative as a whole. In Part 5, Chapter 6, the internal lives of two characters are commented on at once, in the moment of their marriage to one another:

Often and much as they had both heard about the belief that whoever is first to step on the rug will be the head in the family, neither Levin nor Kitty could recall it as they made those few steps. Nor did they hear the loud remarks and disputes that, in the observation of some, he had been the first, or, in the opinion of others, they had stepped on it together.

Point of View in Thoreau's Walden

Henry David Thoreau's transcendental meditations on isolation were based on his actual lived experience. It makes sense, then, that Walden (his account of time spent alone in the woods) is written in the first person point of view :

When I wrote the following pages, or rather the bulk of them, I lived alone, in the woods, a mile away from any neighbor, in a house which I had built myself, on the shore of Walden Pond, in Concord, Massachusetts, and earned my living by the labor of my hands only. I lived there two years and two months. At present I am a sojourner in civilized life again.

What's the Function of Point of View in Literature?

Point of view is the means by which an author relays either one or a multiplicity of perspectives about the events of their story. It is the lens crafted by the writer that allows the reader to see a story or argument unfold. Depending on how much information the writer wants to give the reader, this lens will be constructed differently—or in other words, a different mode of point of view will be chosen:

- If the writer wants the reader to have full access to a particular character's internal life, then they might choose either first person or a closely limited third person point of view.

- If the writer wants the reader to know select bits and pieces about every character, they might choose an omniscient third person point of view.

- If the writer wants the reader to know about the rich internal lives of multiple characters, they might choose an alternating first person point of view.

- Lastly, if the writer wants the reader to feel like they themselves are in the center of the action, they might choose a second person point of view.

Other Helpful Point of View Resources

- The Wikipedia Page on Point of View: An overview of narration with a focus on literary point of view.

- The Dictionary Definition of Point of View: A very basic definition of the term point of view.

- Examples of Second Person: A page with some examples of writing in the less common second person point of view.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1895 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 39,904 quotes across 1895 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Onomatopoeia

- Common Meter

- Formal Verse

- Juxtaposition

- Climax (Figure of Speech)

- Extended Metaphor

- Deus Ex Machina

- Figurative Language

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

Point of View: What Is It? (With 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th POV Examples)

Hannah Yang

One of the most powerful tools in a writer’s toolkit is point of view.

So, what is point of view in literature, and why is it important?

The short answer is that point of view, also called POV, refers to the angle from which a story is told. It includes the specific character who’s telling the story, as well as the way the author filters the story through that character to the reader.

This article will discuss the different points of view you can use in writing, including their strengths, weaknesses, and examples from literature.

What Is Point of View in Writing and Literature?

The importance of point of view, summary of the different points of view, first person point of view, second person point of view, third person point of view, fourth person point of view, what about alternating point of view, conclusion on point of view.

Point of view refers to the perspective through which a story is told.

To understand point of view, try this quick exercise. Imagine you’re telling a story about a well-traveled stranger who enters a small, rural town.

What are all the different perspectives you could tell this story from?

You might tell it from the perspective of the stranger who has never seen this town before and views all of its buildings and streets through fresh eyes.

You might tell it from the collective perspective of the townspeople, who are curious about who this stranger is and why he’s come to this part of the world.

You might even tell it from the perspective of an all-seeing entity, who can see into the minds of both the stranger and the townspeople, all at the same time.

Each of these options centers a different point of view—a different angle for the reader to approach the same story.

Point of view is one of the most important aspects of your story that you must decide before putting pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard). It can have an enormous impact on the tone, style, and even plot of the story.

Each point of view has its own strengths and limitations. In order to choose the right POV, you have to know what you want your story to accomplish.

For example, if you choose first person POV, you’ll be able to immerse the reader in a single character’s voice, humor, and worldview. On the other hand, you also have to show the world with that character’s biases and flawed observations.

The right POV can also completely change the way the story feels. POV is a matter of choice, but one that affects every part of your story or novel.

F. Scott Fitzgerald had to rewrite The Great Gatsby because he initially wrote it in Gatsby’s voice. He decided it would be much more powerful coming from Nick’s more naïve point of view. Imagine that masterpiece with a different point of view—it wouldn’t have the same objective, reliable feeling that it has now.

There are four main points of view that we’ll be discussing in this article: first person, second person, third person (with two subtypes: limited and omniscient), and fourth person.

- First person (“ I pet the cat because I think it looks cute.”)

- Second person (“ You pet the cat because you think it looks cute.”)

- Third person limited (“ She pets the cat because she thinks it looks cute.”) and third person omniscient (“ She pets the cat because she thinks it looks cute. Little does she know, this cat is actually an alien in disguise.”)

- Fourth person (“ We pet the cat because we think it looks cute.”)

Read on to learn the strengths and weaknesses of each of these points of view.

With first person point of view, everything is told intimately from the viewpoint of a character, usually your protagonist. The author uses the first person pronouns I and me to show readers what this character sees and thinks.

First person is the best way to show the story from one person’s point of view because you have an individual person telling you her story directly in her own words. It’s also the easiest way to tell a story that uses a distinct, quirky voice.

The limitations of first person point of view, however, restrict you to only describing what this character sees, thinks, and feels, and sometimes that narrator can be unreliable.

First Person POV Examples

One great example of first person POV is The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath. The narrator is a flawed character, but we see the world entirely through her eyes, complete with her own faults and sorrows. Here’s a short excerpt:

“I began to think vodka was my drink at last. It didn’t taste like anything, but it went straight down into my stomach like a sword swallowers’ sword and made me feel powerful and godlike.”

Compare that with the intimacy you get when reading Scout’s view of things in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird . She speaks with a childlike innocence, giving the reader that same feeling, even if we understand the racism of her town better than she does herself.

“We lived on the main residential street in town—Atticus, Jem and I, plus Calpurnia our cook. Jem and I found our father satisfactory: he played with us, read to us, and treated us with courteous detachment.”

Second person point of view, which uses the pronoun you , is one of the least used POVs in literature because it places the reader in the hot seat and is hard to manage for a full-length novel. It’s used in experimental literature to try out new styles of writing.

In the wrong hands, it just feels gimmicky. But when done well, second person point of view can accomplish a range of wonderful effects.

Second Person POV Examples

“Story of Your Life” by Ted Chiang is a fantastic example of second person POV. It takes the form of a story a mother tells her daughter to explain the circumstances of the daughter’s life. Because the mother is speaking directly to the daughter, the story is imbued with an extra sense of intimacy.

“Right now your dad and I have been married for about two years, living on Ellis Avenue; when we move out you’ll still be too young to remember the house, but we’ll show you pictures of it, tell you stories about it.”

The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin is a Hugo-winning fantasy novel that uses many different POVs, including second person. The second person point of view serves to provide a feeling of disorientation, like the protagonist needs to talk to herself to remind herself what’s going on. Here’s a short excerpt from the very beginning of the story:

“You are she. She is you. You are Essun. Remember? The woman whose son is dead.”

Third person point of view uses pronouns like he , she , and it . This POV allows the reader to follow a character, or multiple characters, from a more distanced perspective than first or second person.

Third Person Limited vs Third Person Omniscient

There are two subtypes of third person point of view: limited and omniscient.

In third person limited, the story follows only one character’s viewpoint throughout the entire piece. This means your reader sees only what the third person narrator sees and learns things at the same time the third person narrator does.

You can show what your main character thinks, feels, and sees, which helps close the emotional distance between your reader and the main character.

This is an excellent POV to use when your story focuses on a single character. In many ways, third person limited is quite similar to first person, even though it involves different pronouns.

The drawback with third person limited POV is that you can only follow one character. Showing other characters’ thoughts and feelings is a no-no.

The other type of third person POV is third person omniscient. In this POV, the story is told from the perspective of an omniscient narrator, who can see inside the heads of all the characters in the story.

This is a great POV to use when you have multiple characters, each with their own plot line to follow, and you want your reader to see everything as it unfolds. It’s also useful for imparting universal messages and philosophies, since the narrator can draw conclusions that no character would be able to on its own.

The downside to third person omniscient is that it can be emotionally distant from the story. Because you’re constantly jumping around to different characters and their story arcs, it’s harder for your reader to get as emotionally involved with your characters.

Third Person POV Examples

Examples of the third person limited POV are the Harry Potter novels. The reader sees everything that’s going on, but is limited to Harry’s point of view. We’re surprised when Harry is surprised, and we find out the resolution at the ending when Harry does. Here’s a short excerpt from the seventh book, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows:

“Harry sat up and examined the jagged piece on which he had cut himself, seeing nothing but his own bright green eye reflected back at him.”

An excellent example of third person omniscient POV is Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables . The reader sees everything that is happening in the story and gets a vivid lesson in politics and society in France’s history.

“He was cunning, rapacious, indolent and shrewd, and by no means indifferent to maidservants, which was why his wife no longer kept any.”

Fourth person is a newer POV that only recently started to be recognized as a distinct POV. It involves a collective perspective, using the plural pronouns we and us .

This POV allows you to tell a story from the perspective of a group, rather than an individual. Since there’s no singular narrative, this option is great for critiquing larger institutions and social norms. Fourth person is even rarer than second person, but when it’s done well, it can be very powerful.

Fourth Person POV Examples

“A Rose for Emily” by William Faulkner is told from the perspective of an entire town.

“We did not say she was crazy then. We believed she had to do that. We remembered all the young men her father had driven away, and we knew that with nothing left, she would have to cling to that which had robbed her, as people will.”

The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides is told from the perspective of a group of teenage boys.

“They were short, round-buttocked in denim, with roundish cheeks that recalled that same dorsal softness. Whenever we got a glimpse, their faces looked indecently revealed, as though we were used to seeing women in veils.”

You might choose to write a novel or story with multiple different points of view.

Some books have two main characters and switch back and forth between their perspectives—this is very common in the romance genre, for instance. Others rotate between three or more characters.

Alternating POV is a great option if your story features multiple main characters, all of whom play an equally important role in the story. The biggest drawback is that you risk confusing your reader when you switch back and forth.

Make sure your reader knows when you’re switching POVs. One common solution is to include a chapter break each time the perspective changes. Some books change the font for each POV, or even the color of the typeface.

It’s also important to make sure each character has a distinct voice. For example, maybe one character writes with short, brusque sentences, while another writes with long, flowery sentences. Keeping the different POVs distinct is crucial for success.

There you have it—a complete guide to point of view and how to choose the right POV for your story.

Before you start experimenting with point of view, get comfortable with the basics first. Read works by authors who use these different POVs with great success to understand how each POV changes the narrative arc of the story.

Happy writing!

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

The Art of Narrative

Learn to write.

Point of View: The Ultimate Guide

Answer all your questions about how to write in first, second, and third person point of view. Every point of view is covered including how to use tense.

I’ve been staring at my screen for ten minutes trying to come up with a hook that somehow, someway will lead off an article about literary point of view. I’ve come to a definite conclusion: you can’t. To do so would subvert the laws of man, physics and God. It’s impossible. I defy you to try it.

Anyway, let’s talk about POV.

If you’re a beginning writer you might not think much about point of view. But, you should.

All writers should spend significant time considering what POV they’ll use for a story, and why. POV is as important to a story as is your plot , characters , setting , etc.

What is point of view in writing?

Point of view tells your reader who is important in your story. It affects the relationship your reader builds with your characters. And, if done poorly, the point of view can ruin an otherwise perfect story.

You’d like to avoid that, wouldn’t you? Of course! So, for your consideration, I bring to you the ultimate guide to point of view.

(Is it really the ultimate guide to POV? Probably not, but it makes for a good title, right?)

In this article I will explain every type of POV you could possibly use in your writing, and when to use each one. I’ll also answer all your burning questions about POV. You know the ones you’ve always wondered about but didn’t want to ask.

More importantly, I’ll cover some of the common POV mistakes and how to avoid them.

But first, let’s start with the basics-

Point of view is the term used to describe who the author chooses to tell their story. But really, and more importantly, it’s who your reader is engaging with.

When we talk about point of view we’re talking about the narrator. An author might have the main character or a secondary character speak directly to the reader as if you are reading that character’s journal.

Or, the narrator might not be in the story at all, but a voice above the fray who can describe the action of a story.

The narrator may also know certain characters’ thoughts and feelings about the events unfolding. While some POVs will insert the reader directly into the action of the story.

The point is, point of view is an important consideration for any story, and mistakes in POV can ruin a story. So, it’s important to choose your POV carefully and avoid the common pitfalls.

With that said, let’s discuss the different types of POV, why they are used, and the common POV mistakes that you need to avoid.

What are the different types of point of view?

Point of view can be divided into three categories- first person, second person, and third person. Third person point of view can be broken down further into limited, omniscient, and objective.

All POVs can be written either in the past or present tense.

Let’s take a look at each of these individually.

First Person Point of View

What is First Person Point of View?

You’re the reader and the character is telling you the story. You and the character are like old friends; they’re very open with you about their thoughts and feelings. It’s as if you’re reading their journal. Usually, the perspective character is the main character of the story, but not always.

Take, for instance, The Great Gatsby which is written in the first person, but the perspective character is Nick Caraway. Nick takes part in the events of the story and relays them to the reader, but he is not the main character.

However, this is an exception, not the rule. Your point of view character should be the protagonist unless you have a good reason for them not to be.

You’ll know your reading a story in the first person when you see pronouns like I, me, or my. The character is the narrator, so they will be speaking directly to the reader.

How to write First Person Point of View

Writing from a first person point of view is a solid choice if your beginning writer. It’s a straightforward perspective that isn’t too difficult to work with. Choose a character, like your protagonist, and write the story as if they are retelling the events to the reader.

If you choose the first person perspective you’ll need to know your character intimately. You want their personality to remain consistent throughout the narrative. That is unless they’re a dynamic character . Even then, changes in the character will need to have a cause that develops from your plot.

Interview your point of view character. Know their background, what their fears are, and what motivates them. The challenge of the first-person perspective is keeping your character’s voice, actions, and reactions consistent and believable.

In other words, don’t change your character’s personality for the needs of the plot. What does that mean? If your character has been even-keeled and calm throughout the story don’t force them to blow up in anger because you need to inject some tension into a scene.

Know your perspective character, and don’t deviate from the personality that you’ve established, unless that change is earned through the narrative. Your reader will notice otherwise.

When to use First Person Point of View

There are times when using the first person perspective is axiomatic like when writing a memoir or a personal essay. The first person POV is a good choice for writers who are just starting out. The limited nature of first person will help beginning writers avoid some common POV mistakes such as head-hopping. But, more on that later.

Because of its natural limits, the first person is a good choice if there are details of the plot that you want to hide from the reader. Take the example of an unreliable narrator who is lying about the events of the story. Discovering new information a narrator has kept hidden can be an exciting revelation for your reader.

Or, because your writing from the perspective of one character, the reader can discover story details as your character does. This works to great effect in the genres of mystery, horror, and romance. These genres require the character, and reader to work through the details of an event slowly to discover startling truths.

Lastly, the first person POV is a good choice if you’re writing a small, character-driven plot with a limited cast. However, it’s not the best choice for your epic, world-building fantasy.

Example of First Person Point of View

“I couldn’t forgive him or like him, but I saw that what he had done was, to him, entirely justified. It was all very careless and confused. They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

― F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

Learn about first-person point of view here!

What is Second Person Point of View?

You, the reader, are now in the story. You are the protagonist. You’re taking part in the action. Not literally, obviously. Not yet anyway. Until some advances in VR second person will remain figurative.

The writer uses pronouns like you and your. In fiction, this is not a very common practice. But, you will find the second person POV a lot in non-fiction works. Instructional texts like cookbooks are written in second-person. Think, “You’ll need to preheat your oven to 450 degrees. ”

Why isn’t Second Person Point of View popular?

The limitation of the second person perspective is that you’re asking your readers to put themselves directly into the story. This takes considerable suspension of disbelief on their part. And, it may put your reader off as they’re not used to reading this kind of narrative.

The second person point of view tells your reader that they are someone they’re not. That the events of the story are happening to them, the reader. It’s a funky style, let’s be honest. Reserved, mostly, for those “choose your adventure” books we read as children.

However, when executed well, this funkiness is the secret strength of the second-person perspective. What better way to encourage your reader to empathize with a character and experience a new perspective.

While not traditional, a story written in the second-person perspective could be a great way to set your work apart from the pack. But, only if you put in the effort to make it work. Know that an editor will ask the question- “Why did you choose second person POV?” If you don’t have an obvious answer, revealed in the text, this may be a weakness.

When it comes to digital storytelling though, second person POV could be the dominant perspective. Maybe we should start practicing…

Example of Second Person Point of View

“Things happen, people change,’ is what Amanda said. For her that covered it. You wanted an explanation, and ending that would assign blame and dish up justice. You considered violence and you considered reconciliation. But what you are left with is a premonition of the way your life will fade behind you, like a book you have read too quickly, leaving a dwindling trail of images and emotions, until all you can remember is a name.”

― Jay McInerney, Bright Lights, Big City

Third Person Limited Point of View

What is Third Person Limited Point of View?

Take one step above the story. The narrator is no longer in the fray and action. They are on the outside looking in, commenting on the action. The narrator tells the reader what is happening, and what the perspective character is thinking and feeling.

A third person limited perspective means that we are limited (get it?) to a single character at a time. So, it’s like the first person perspective, but rather than a character speaking directly to us, the narrator is telling us what the character is doing, thinking and feeling.

How to write Third Person Limited Point of View

The first thing you want to do is choose a character to limit yourself to. More than likely, this will be your protagonist. You may also switch to another perspective character in your story.

However, don’t switch character perspectives within the confines of a single scene, or even a chapter. In truth, you may want to keep your perspective limited to the same character throughout the narrative.

There are examples of rotating perspective when using third person limited. Authors who do this will change the perspective characters from one character to the next. For clarity, chapters are usually named after the point of view character in that chapter.

How to describe characters in Third Person Limited Point of View

This is a question that comes up when writing from a limited point of view. Character descriptions can be tricky because overtly describing a non-POV character’s emotions would count as a slip in POV. You don’t want that.

Rely on the old adage- show, don’t tell. If a non-POV character is upset then have them slam a door, throw a punch, or break a window. Demonstrate emotion through action, not through adverbs.

Remember that your narration is limited physically, as well. Your narration can’t describe anything the point of view character isn’t able to see, touch, taste, hear or smell directly. The character’s eyes are your window into the world of the story. Keep this in mind when describing the different aspects of your story.

When to use Third Person Limited Point of View

Much like first person point of view, the third person is used when you want to limit the reader’s perspective. Use this POV when you want your readers to spend time with, and become very familiar with a character or cast of characters. When you want your reader to become attached to your protagonist(s). Third person POV is perfect for your character-driven story arcs.

Choose third person POV over first person when your story has several character arcs to explore. An example would be the Harry Potter series. Sure, Harry is important, but we care about Hermione and Ron too.

Also, the third person limited POV works well in mysteries, horrors, and crime stories. This is because you can easily hide information from your reader like you can with first person POV.

Because of its versatility, third person limited is the most popular POV in modern fiction. Readers and editors are used to reading in third person limited POV. In most cases, third person limited POV will be a good choice for your story. .

Example of Third Person Limited Point of View

“For the first time, he heard something that he knew to be music. He heard people singing. Behind him, across vast distances of space and time, from the place he had left, he thought he heard music too. But perhaps, it was only an echo.”

― Lois Lowry, The Giver

Third Person Omniscient Point of View

What is Third Person Omniscient Point of View?

You’re the reader, and the narrator is God. They can give you access to every character’s thoughts and feelings, at the same time. Third person omniscient is like third person limited in that the narrator is separate from the story.

However, the narrator is not limited to one character’s viewpoint when describing the story. The narrator has full knowledge of all the characters and has no preference for any single character. Common pronouns used with third person omniscient are “he,” and “she.”

How to write in Third Person Omniscient Point of View

Third person omniscient can be challenging as you have a lot of characters to keep up with. Each major character will need the same attention from the narrator. It can also be difficult to keep your narrative focused with the POV spread out like this.

Use this perspective to insert your own authorial voice into the narrative. As the narrator, you can comment on the action of the story, or the characters. But, beware that this is not a style of writing that is currently in vogue.

The third person omniscient POV does provide a lot of creative freedom, though. Because of the “God-like” presence of the narrator, you’re not hemmed in by a lot of rules. The author can describe anything that a character is thinking, wearing, doing, seeing, etc.

When to use Third Person Omniscient Point of View

Never. Just kidding, but keep this in mind:

The third person omniscient perspective, while once omnipresent, is not very popular anymore. It’s a good choice if you have a plethora of characters in your story. This is because this perspective gives you the ability to inhabit any character in the story. However, realize this will make developing any single character difficult.

Choose the third person omniscient POV when you have a very strong voice, and you want the narrative commentary to take the center stage of your story.

Example of Third Person Omniscient Point of View

“A man’s at odds to know his mind cause his mind is aught he has to know it with. He can know his heart, but he don’t want to. Rightly so. Best not to look in there. It ain’t the heart of a creature that is bound in the way that God has set for it. You can find meanness in the least of creatures, but when God made man the devil was at his elbow. A creature that can do anything. Make a machine. And a machine to make the machine. And evil that can run itself a thousand years, no need to tend it.”

― Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West

Third Person Objective Point of View

What is Third Person Objective Point of View?

In the third person objective POV, the reader does not have access to any character’s thoughts or feelings. The narrator is completely objective.

How and when to use Third Person Objective POV

Again, show don’t tell.

With third person objective, a writer will have to convey all the characters’ emotions through action alone. If you’re a beginning writer try and write at least one story in the third person objective POV. It’s good for practice.

In order to master this POV, a writer must be a keen observer of people in the real world. How do people show their emotions- on their face, in their body language, with words?

How does someone demonstrate they’re angry with their boss? A real person wouldn’t act out dramatically. They wouldn’t flip a table or punch a hole in the drywall (hopefully). Because acting like that would get them fired, probably arrested. They may, instead, make a snide remark, purse their lips, or cross their arms.

The point is, people can be very subtle in how they display their inward feelings. Many people do their best to mask emotions. Others act out for attention. As a writer, you should be able to identify these subtle tells and insert them into your story. Especially if you plan on using the third person objective.

Third person objective POV is also useful in non-fiction. A biographer can’t always comment on the thoughts of feelings of their subject. Especially if the subject has been dead for hundreds of years. In that case, they can only convey a sense of emotion through their subject’s words or actions.

Example of Third Person Objective POV