A Summary and Analysis of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf is probably the most famous and widely studied American play associated with the Theatre of the Absurd, a movement prominent in the 1950s and 1960s. Edward Albee’s play is about the dysfunctional and self-destructive marriage between a history professor and his wife, witnessed over the course of one night (or, technically, one very early morning) following a party.

But how should we analyse Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf ? Before we come to the question of analysis, here’s a brief recap of the play’s absurdist plot.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf : plot summary

The setting for the play is a professor’s house on the campus of a New England university. At two o’clock in the morning, George, a professor of history, and his wife Martha return home after a party. Martha is the daughter of the president of the university where her husband teaches. Their first names suggest George and Martha Washington, the first President and First Lady of the United States.

George is in his late forties and his wife is six years older, in her early fifties. Where he is somewhat cynical and world-weary, she is fiery and vulgar. She has invited a young couple back with them: Nick, a twenty-something biology lecturer at the university, and his wife Honey, a plain-looking woman also in her twenties.

The first act, ‘Fun and Games’, sees Martha trying to seduce Nick while humiliating both her husband and, to an extent, Honey. As she gets more drunk, Honey grows bolder and asks George and Martha when their son will be coming home.

Doubts are raised over whether George is the biological father of the couple’s son, and Martha reveals that her father had discounted George as a potential candidate to succeed him as president of the university because he isn’t good enough. Honey rushes off to the toilet to be sick, as she has drunk too much.

The second act of the play is titled ‘Walpurgisnacht’, after the witches’ feast or sabbath. Nick confides to George that he only married Honey because she had a phantom pregnancy and he felt he had to do the honourable thing. The two men talk at length, before Nick makes a comment about getting Martha in a corner and ‘mounting’ her.

Martha then seeks to provoke maximum embarrassment in her husband by dancing suggestively with Nick and telling Nick and Honey that her father stopped George from publishing a novel he’d written, about a boy who murders his parents – a book which George insists was autobiographical.

George turns increasingly nasty, decreeing that they should play a party game he calls ‘Get the Guests’. He mockingly re-enacts Honey’s phantom pregnancy, using the information Nick confided in him to taunt them and sow conflict. In response, Martha tries to seduce Nick again, taking him off to the kitchen so they can ‘hump’ there. George confides that his and Martha’s son is, in fact, dead.

The third act, ‘The Exorcism’, begins with Martha alone; when Nick enters, she accuses him of being a ‘flop’ just like her husband. George tells them that there is one more game to play: ‘bringing up baby’.

He and Martha pay tribute to their son, on his twenty-first birthday, before George tells his wife that their son has died in a car crash. When she demands to see the telegram announcing this news, he claims he has eaten it. George sings a song, ‘Who’s afraid of Virginia Woolf’, as the curtain falls.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf : analysis

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf is often analysed as a response to a specific moment in US history: in 1962, when the play premiered, John F. Kennedy was President, and the United States had a confidence in itself as the leading world superpower. At the same time, tensions with the USSR, particularly over Cuba, led to uncertainty over the future.

American life and self-confidence, which had perhaps been at its peak in the 1960s, was beginning to look like a double-edged sword: cosy and comfortable on the outside, but playing host (as it were) to some darker and more worrying secrets and anxieties.

Albee’s play brilliantly dramatises these, reducing them to a domestic setting centred on middle-class America. The names of the two leads, George and Martha, take us back to the founding of the United States and its first President; this further supports the notion that the play should be read as being ‘about’ America, as well as the lives of individual middle-class Americans.

Edward Albee wrote in the New York Times in 1962 that he was ‘deeply offended’ when he learned he was becoming associated with the Theatre of the Absurd. As he argued in an essay, ‘Which Theatre is the Absurd One’, one could argue that absurdist theatre is actually more realist, and closer to reality, than so-called ‘naturalist’ or traditional theatre, which was reliant on conventions which failed to reflect actual life.

So whereas naturalist theatre offers itself as a ‘slice of life’, absurdist drama tends to use dream-like rituals and allegories; whereas naturalist drama follows the rational and logical chain of cause and effect (one character does something; another character reacts as one would expect), absurdist theatre does not have to subscribe to such a rational linearity of plot.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf , with its strange party games and rituals and its refusal to develop in terms of plot and character, is therefore an emblematic example of absurdism. The ritualistic element is even apparent in the pagan and religious titles given to the different acts of the play, e.g., ‘Exorcism’.

Nowhere is this better demonstrated than in the question of whether George and Martha actually have a son at all. Like Honey’s phantom pregnancy, the sense we’re left with, by the end of the play, is that he never existed at all: he, too, was a phantom, conjured by George and Martha as a focal point for their dysfunctional marriage.

And if we view Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf as an absurdist allegory for America at a particular point in its history, the early 1960s, the son that doesn’t exist might be analysed as a symptom of the country’s anxieties over its future.

Just as the couple have no children yet their imaginary son is the heart and soul of their conflicted relationship, so America is looking to its future – the space race which Kennedy had begun the decade by championing – while ignoring the problems and challenges closer to home.

Edward Albee’s original title for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf was ‘Exorcism’, which he ended up using as the title for the final act of the play. The eventual title came from a bar which Albee frequented, where patrons would leave graffiti, written in soap, on a large mirror. Albee saw someone had riffed on ‘who’s afraid of the big bad wolf’ (from ‘ Little Red Riding Hood ’) and daubed ‘who’s afraid of Virginia Woolf’, a reference to the modernist writer, and Albee made a mental note of the phrase, thinking it would make a good title for a play.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from interesting literature.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Drama Criticism › Analysis of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Analysis of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on August 3, 2020 • ( 1 )

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? is in many important respects a “first.” In addition to being the first of Albee’s full-length plays, it is also the first juxtaposition and integration of realism and abstract symbolism in what will remain the dramatic idiom of all the full-length plays. Albee’s experimentation in allegory, metaphorical clichés, grotesque parody, hysterical humor, brilliant wit, literary allusion, religious undercurrents, Freudian reversals, irony on irony, here for the first time appear as an organic whole in a mature and completely satisfying dramatic work. It is, in Albee’s repertory, what Long Day’s Journey into Night is in O’Neill’s; the aberrations, the horrors, the mysteries are woven into the fabric of a perfectly normal setting so as to create the illusion of total realism, against which the abnormal for the first time, the “third voice of poetry” comes through loud and strong with no trace of static.

—Anne Paolucci, From Tension to Tonic: The Plays of Edward Albee

The Broadway opening of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? on October 13, 1962, certainly qualifies as one of the key dates in American drama, comparable to March 31, 1945, and December 3, 1947 (the Broadway premieres of Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie and A Streetcar Named Desire ), February 10, 1949 (the opening of Arthur Miller’s The Death of a Salesman ), and November 7, 1956 (the first U.S. performance of Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night ). A few months before it opened Albee published a scathing attack in the New York Times asserting that Broad-way was the true theater of the absurd because of its slavish devotion to the superficial and the unchallenging. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Albee’s first full-length play and Broadway debut, was a direct assault on a lifeless and shallow commercial American theater, igniting a new excitement and vitality by its radical style and content. With this play American drama, as it had not had since the 1940s, regained its power and importance as an instrument of truth. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , in the words of critic Gilbert Debusscher, “immediately became the subject of the most impassioned controversies, the object of criticism and accusation which recall the storms over the first plays of Ibsen, and, closer to our own time, Beckett and Pinter.” Few other characters on the American stage had ever gone at one another so mercilessly nor exposed their psychological core in language that drama historian Ruby Cohn called “the most adroit dialogue ever heard on the American stage.” Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? propelled Albee into the front rank of American dramatists. He would go on to dominate American drama in the 1960s and 1970s, serving as the link between the previous generation of American dramatists—O’Neill, Williams, and Miller—and the next that followed him, including David Mamet, Sam Shepard, and Tony Kushner. President Bill Clinton at the Kennedy Center’s honors ceremony in 1996 aptly summarized Albee’s achievement by declaring to the playwright, “In your rebellion, the American theater was reborn.”

Abandoned shortly after his birth in 1928, Albee was adopted by Reed and Frances Albee, heirs to the Keith-Albee theater chain fortune, founded by the playwright’s adoptive grandfather and namesake, Edward Frances Albee. Growing up in a mansion in Westchester County, New York, the “lucky orphan,” as Albee described himself, was raised, as one magazine reported, in a “world of servants, tutors, riding lessons; winters in Miami, summers sailing on the Sound; there was a Rolls to bring him, smuggled in lap robes, to matinees in the city; an inexhaustible wardrobe housed in a closet big as a room.” Because of the family’s theatrical connections, actors, directors, and producers were frequent house guests. Albee attended performances from the age of six and wrote his first play, a sex farce, when he was 12. Enrolled in and expelled from a number of boarding schools as an undisciplined and indifferent student, Albee eventually graduated from Choate in 1946 where he had begun to distinguish himself by his writing, publishing poems, short stories, and a one-act play in the school literary magazine. After attending Trinity College briefly Albee left home in 1950 determined to pursue a writing career. Supported by a trust fund that provided him with $50 a week, Albee became, in his words, “probably the richest boy in Greenwich Village.” For the next decade, through his 20s, Albee worked in a succession of odd jobs—as an office-boy in an advertising agency, as a luncheonette counterman, writing music programs for a radio station, selling records and books, and delivering messages for Western Union. Most of the poetry and the long novel he wrote during this period have never been published. Searching for direction Albee was encouraged by Thornton Wilder to concentrate on drama. During his “Village decade,” Albee, as his roommate William Flanagan recalled, “was, to be sure, adrift and like most of the rest of us, he had arrived in town with an unsown wild oat or two. But from the beginning he was, in his outwardly impassive way, determined to write. . . . He adored the theatre from the beginning and there can’t have been anything of even mild importance that we didn’t see together.” Through the period, Flanagan remembered, Albee had a “thoroughly unfashionable admiration for the work of Tennessee Williams.” Other influences that would impact his initial dramatic work came from European dramatists of the absurd, such as Samuel Beckett and Eugène Ionesco.

On the eve of his 30th birthday, in despair over his inability to produce anything of importance and “as a sort of birthday present to myself,” Albee completed his first major play, The Zoo Story , a one-act, two-character drama in which two strangers—Jerry and Peter—meet in New York City’s Central Park. Jerry, lonely and desperate for meaningful contact with another, provokes Peter into a fight in which he impales himself, gratefully, on the knife he has given Peter. A tour de force of compression and intensity, The Zoo Story serves as a kind of overture to themes that would dominate Albee’s subsequent work, including the shattering of complacency, the connection between love and aggression, and the relationship between fantasy and reality. Initially rejected by American producers the play was first performed at the Schiller-Theater Werkstatt in West Berlin in 1959. It debuted in the United States in 1960 at the Provincetown Playhouse in Greenwich Village on a double bill with Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape, establishing the connection between Beckett and Albee that marked the younger playwright as an American proponent of the theater of the absurd. The designation initially offended Albee, but he eventually accepted the association with a characteristic contrariness. “The Theatre of the Absurd,” he insisted, “. . . facing as it does man’s condition as it is, is the Realistic theatre of our time; and . . . supposed Realistic theatre . . . pander[ing] to the public need for self-congratulation and reassurance and present[ing] a false picture of ourselves to ourselves is . . . really and truly The Theatre of the Absurd.” He would later define the theater of the absurd as “an absorption-in-art of certain existentialist and post-existentialist philosophical concepts having to do, in the main, with man’s attempt to make sense for himself out of his senseless position in a world which makes no sense—which makes no sense because the moral, religious, political and social structures man has erected to ‘illusion’ himself have collapsed.” Albee’s next three plays ( The Sandbox, The American Dream, and The Death of Bessie Smith ), all produced in 1960–61, are scathing critiques of these collapsed illusions, exposing the absurdity of American family life and racial prejudice. Like The Zoo Story , they counter the dominant realistic mode of American drama with antirealistic techniques derived from the European modernist dramatic tradition.

Albee’s breakthrough drama, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , synthesizes both naturalistic and absurdist theatrical elements such that the realistic American family drama, whose precedents include A Streetcar Named Desire, Death of a Salesman, and Long Day’s Journey into Night , is infused with the methods and existential themes derived from European postwar drama. “Like European Absurdists,” Cohn argues, “Albee has tried to dramatize the reality of man’s condition, but whereas Sartre, Camus, Beckett, Genet, Ionesco, and Pinter present reality in all its alogical absurdity, Albee has been preoccupied with illusions that screen man from reality.” Asked to describe his work in progress that would become Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Albee called his play a “sort of grotesque comedy” concerning “the exorcism of a non-existent child” that deals with “the substitution of artificial for real values in this society of ours.” Albee initially called the play “The Exorcism” (the title later assigned to act 3) but arrived at Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? after discovering the phrase as graffiti in a Greenwich Village bar. Albee has explicated his title with its reference to a writer centrally concerned with the nature of reality, to mean “Who is afraid of facing life without illusions?” The question serves as the play’s repeated refrain and ultimatum. Set in the New England college town of New Carthage, in the living room of a history professor and his wife—George and Martha—the play depicts the boozy, late-night verbal warfare and lacerating revelations that emerge when they entertain a new faculty member and his wife, Nick and Honey.

Act 1, “Fun-and-Games,” introduces the four combatants. George is a 46-year-old associate professor who has failed to realize the expectations of his wife, the daughter of the college’s president, to succeed her father. Martha is “a large, boisterous woman, 52, looking somewhat younger. Ample, but not fleshly.” Their continual and escalating quarrelling, which George calls, “merely . . . exercising,” is rooted in their mutual dependency, frustrations, and guilt. Having returned late from a faculty party, Martha repeats the joke she has heard earlier in the evening in which “ Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? ” is sung to the tune of “Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush” while informing George that she has invited “what’s-their-names” over for a drink. Nick is a new young biology professor married to Honey, a “rather plain” blond, who arrive after George has warned Martha “don’t start in on the bit ’bout the kid” to which Martha responds with a decisive “Screw You!” The act then proceeds with George and Martha’s “exercising” in front of their guests. Warning Martha, who escorts Honey to the “euphemism,” not to talk about “you-know-what,” George evades Nick’s question about whether they have children by responding, “That’s for me to know and you to find out.” Honey, however, returns saying that “I didn’t know until just a minute ago that you had a son.” Martha follows, having changed into a more provocative outfit, and begins to flirt with Nick while disparaging George’s masculinity with a story about how she once boxed with him and knocked him into the huckleberry bushes. “It was funny, but it was awful,” she explains. “I think it’s colored our whole life. . . . It’s an excuse anyway. . . . It’s what he uses for being bogged down anyway.” George responds by retrieving a shotgun and aims it at the back of Martha’s head. As Honey screams, Martha turns to face George, and he pulls the trigger, fi ring a Chinese parasol. “You’re dead! Pow! You’re dead!” George exclaims. Martha, evidently pleased by his performance, demands a kiss, and when George refuses her advances in front of their guests, she shifts her attention back to Nick, saying “You don’t need any props, do you baby? . . . No fake Jap gun for you.” Martha’s taunting of her husband (“You see, George didn’t have much push . . . he wasn’t particularly . . . aggressive. In fact he was a sort of a FLOP!”) prompts George to drown out her needling with the “ Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? ” song. Honey becomes sick and retreats down the hall, pursued by Nick and Martha, as the act ends with George alone on stage, embodying defeat and hopelessness.

Act 2, “Walpurgisnacht”—the witches’ orgiastic Sabbath—both increases George’s torment and creates the conditions that make a recovery possible. Locked into their marital mutually assured destruction and sustained by the illusion of a son as an embodiment of their relationship, George and Martha move toward the recognition of painful truths. Proposing a new series of games—“Humiliate the Host,” “Hump the Hostess,” and “Get the Guests”—George begins with the last, betraying Nick’s confidence about his courtship and marriage to Honey motivated by her family fortune and a false pregnancy. Upset, Honey rushes out to pass out in the bathroom. As Nick and Martha dance and kiss, George ignores them by reading a book, but when they leave together, he flings the book hitting the door chimes. The noise rouses Honey who asks who is at the door. This gives George the idea that a messenger has come announcing the death of their son.

Analysis of Edward Albee’s Plays

Act 3, “Exorcism,” represents the play’s dramatic turn, the casting out of the various devils—jealousy, frustration, anger, and remorse—that have condemned George and Martha to their marital hell in which their mutual destruction has replaced self-recognition. Martha enters the living room upbraiding Nick, who she renames “Houseboy,” for his failed sexual performance. George arrives carrying a bouquet for Martha, echoing a scene from Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire (“ flores para los muertos ”) as a prelude to announcing the death of their son. He calls for one final game (“we’re going to play this one to the death”). As Martha rapturously talks about their “beautiful, beautiful boy,” George intones liturgical Latin before declaring “Our son is dead!” Martha reacts with horror, screaming “You cannot do that!” She demands to know why he has killed their imaginary child, and George answers that she has broken the rules by mentioning him to another. Martha responds: “I mentioned him . . . all right . . . but you didn’t have to push it over the EDGE. You didn’t have to . . . kill him.” To which George replies with the benediction from the mass and the words, “It will be dawn soon. I think the party’s over.”

After Nick and Honey have gone, George and Martha are left alone on stage. Martha persists in asking George “did you . . . have to.” He insists that “It was . . . time,” and that their lives will be better for the truth. Martha is doubtful.

Martha: Just . . . us? George: Yes. Martha: I don’t suppose, maybe, we could . . . George: No, Martha. Martha: Yes. No. George: Are you all right? Martha: Yes. No. George: [ Puts his hands gently on her shoulder, she puts her head back and he sings to her, very softy. ] Who’s afraid of Virginia Woolf Virginia Woolf Virginia Woolf? Martha: I . . . am . . . George. . . . George: Who’s afraid of Virginia Woolf. . . . Martha I . . . am . . . George. . . . I . . . am. . . . [ George nods, slowly. Silence, tableau. ]

Having divested themselves of the fantasies that have ruled and sustained them, George and Martha confront themselves and their reality with sorrow for their loss and uncertainty about their future. After the preceding Sturm und Drang, the play reaches a stunned silence, and George and Martha, who have played role after role in their marital battle, settle into a final resemblance: Adam and Eve after the fall, contemplating a life without illusions. Their brave new world of existential reality is matched by the new departure for American drama that Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? made possible, in which unrelentingly honest dialogue and characterization unite to explore key human and existential issues.

Share this:

Categories: Drama Criticism , Literature

Tags: American Literature , Analysis of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Bibliography of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Character Study of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Criticism of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Drama Criticism , Edward Albee , Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Essays of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Literary Criticism , Man and Superman Essay , Notes of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Plot of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Simple Analysis of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Study Guides of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Summary of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Synopsis of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Themes of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Analysis , Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Criticism , Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Guide , Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Lecture , Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? PDF , Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Summary , Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Themes

Related Articles

This was an amazing analysis!! Such a great read 🙂

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Summary, Characters and Themes

“Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” is a play by Edward Albee first staged in 1962. This intense and gripping drama explores the complexities of marriage, the pain of illusion versus reality, and the destructive nature of personal and social expectations.

The play is set in the home of a middle-aged couple, George and Martha, who, after a university faculty party, invite a younger couple, Nick and Honey, to their home for late-night drinks. This setup serves as the stage for an evening of brutal honesty and psychological warfare.

Act 1: Fun and Games

The play opens with George and Martha returning from a faculty party at the small New England college where George works as a history professor and Martha’s father is the president. It’s clear from the beginning that their relationship is fraught with tension, characterized by bitter and sarcastic exchanges.

Despite the late hour, Martha informs George that she has invited a young biology professor, Nick, and his wife, Honey, over for drinks.

When the guests arrive, they quickly become entangled in George and Martha’s toxic games of humiliation and one-upmanship.

The act is filled with sharp wit, dark humor, and a palpable sense of unease as the older couple exposes their guests—and each other—to cruel and manipulative behavior.

Act 2: Walpurgisnacht

The second act delves deeper into the psychological underpinnings of the characters. Named after a European festival associated with witches and the supernatural, this act underscores the night’s descent into chaos and revelation.

As the night progresses, George and Martha’s attacks on each other become more vicious and personal. It becomes apparent that their marriage is built on a foundation of illusions and lies, particularly concerning their son, whose existence is hinted at but remains ambiguous.

Nick and Honey’s own secrets start to unravel, revealing Nick’s career ambitions and Honey’s fears about pregnancy and her marriage.

The act ends with George preparing to reveal his most devastating game yet, signaling a climax to the night’s cruelty.

Act 3: The Exorcism

The final act brings the emotional and psychological conflict to a head.

George announces a game called “Bringing Up Baby,” where he reads from a book that mirrors the childlessness of him and Martha, exposing the deepest and most painful illusion of their lives: the son they often speak of does not actually exist. This revelation is George’s attempt to confront and exorcise the lies that have poisoned their marriage.

Martha, devastated and stripped of her defenses, confronts the reality of her relationship with George and the emptiness of their lives without their imagined child.

The play concludes with George and Martha, in a moment of rare tenderness and vulnerability, facing the harsh dawn of a new day and the possibility of beginning again, freed from their delusions.

George is a history professor at a small college, characterized by his passive-aggressive demeanor and biting wit. He appears to be the more submissive partner in his marriage to Martha, often the target of her scorn. However, his seemingly passive exterior masks a deep resentment and a cunning ability to manipulate.

George uses his intelligence and knowledge of personal secrets to control and undermine others, particularly Martha. His complex character reveals a man disillusioned with his career, embittered by his failures, and desperate to maintain some sense of power within his tumultuous marriage.

Martha, the daughter of the college president, is loud, boisterous, and deeply unhappy. Her aggressive and domineering personality often overshadows George’s more subdued nature.

Martha’s behavior reflects her frustration with her unfulfilled life, her marriage’s failures, and her unmet desires for affection and success.

She engages in the verbal and emotional demolition of George as a way to vent her frustrations and disappointments, yet it becomes clear that her cruelty is a twisted form of dependence on him. Martha’s vulnerability ultimately surfaces, exposing the pain and longing beneath her brash exterior.

Nick is a young biology professor who, along with his wife Honey, becomes entangled in George and Martha’s night of psychological warfare. Ambitious and somewhat shallow, Nick represents the new generation aiming to ascend the academic ladder by any means necessary.

His interactions with George and Martha reveal his opportunistic nature and his discomfort with the depth of the older couple’s dysfunction.

Nick’s character serves as a foil to George, highlighting themes of youth versus aging, ambition versus disillusionment, and the superficial versus the authentic.

Honey is Nick’s naive and fragile wife, whose backstory unfolds to reveal deeper layers of complexity and sadness. Initially presented as a somewhat dim and hysterical character, Honey’s own secrets—her fear of pregnancy, her hysterical pregnancies, and her marriage’s foundation on pretenses—gradually surface.

She embodies the themes of illusion versus reality and the personal costs of maintaining appearances.

Honey’s character highlights the destructive impact of secrets and the pervasive nature of dysfunction, not just in George and Martha’s marriage, but in the seemingly younger, more naive generation represented by her and Nick.

1. Illusion vs. Reality

One of the most striking themes in Albee’s play is the tension between illusion and reality.

George and Martha, trapped in a web of their own lies and fantasies, epitomize the human tendency to fabricate personal narratives that shield them from their unpalatable truths. Throughout the night, they engage in games that blur the lines between what is real and what is imagined, particularly with the existence of their son.

This theme is not just limited to the personal level but extends to a broader critique of societal norms and expectations, where appearances often overshadow truth.

The play meticulously unravels how these illusions are not mere fabrications but serve as coping mechanisms for deeper, unaddressed pain, leading the audience to question the very nature of truth and the realities we choose to accept or deny.

2. The Nature of Marriage

Albee scrutinizes the institution of marriage through the volatile relationship of George and Martha.

Their marriage, marked by bitterness, resentment, and mutual deception, serves as a dark mirror reflecting the complexities and sometimes the hidden agonies of matrimonial bonds.

Through their interactions, the play explores how marriage can become a battleground for power, identity, and validation. Yet, in their moments of vulnerability, George and Martha reveal a deep, albeit twisted, dependence on each other that suggests marriage can also be a source of comfort and understanding, however perverse it may appear.

This duality presents marriage as a multifaceted institution, capable of both destruction and profound, if unconventional, companionship.

3. Impact of Societal Expectations

The characters in the play are all, in one way or another, victims of societal expectations.

Martha is burdened by her father’s success and the expectation to have a similarly illustrious marriage and career, while George feels the pressure of not fulfilling the traditional role of a successful academic.

Nick and Honey, too, are emblematic of the American Dream’s promise and its underlying pressures — the ambition for success, the ideal of a perfect marriage, and the desire for offspring.

These societal norms and expectations exacerbate the characters’ personal failures and insecurities, driving them into further despair and disillusionment.

Albee uses these dynamics to critique the social constructs that dictate personal worth and success, highlighting the alienation and conflict they engender within personal relationships and within oneself.

Final Thoughts

“Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” is a powerful exploration of the illusions people create to cope with their disappointments and the brutal reality that ensues when those illusions are stripped away.

Through the night’s dark journey, Albee examines themes of identity, reality, and the destructive force of illusions in personal relationships.

The title itself, a play on the song “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” and the famous writer Virginia Woolf, hints at the fear of facing harsh truths lurking beneath the surface of everyday life.

Sharing is Caring!

A team of Editors at Books That Slay.

Passionate | Curious | Permanent Bibliophiles

Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf

Edward albee, everything you need for every book you read..

- Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf

Edward Albee

- Literature Notes

- The Significance or Implications of the Titles of the Acts

- Edward Albee Biography

- About Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf

- Character List

- Summary and Analysis

- Act 1: Fun and Games: Scene i

- Act 1: Fun and Games: Scene ii

- Act 1: Fun and Games: Scene iii

- Act 1: Fun and Games: Scene iv

- Act 1: Fun and Games: Scene v

- Act 1: Fun and Games: Scene vi

- Act 1: Fun and Games: Scenes vii-ix

- Act 1: Fun and Games: Scenes x-xi

- Act II: Walpurgisnacht: Scenes i-iii

- Act II: Walpurgisnacht: Scene iv

- Act II: Walpurgisnacht: Scenes v-vi

- Act II: Walpurgisnacht: Scenes vii-x

- Act II: Walpurgisnacht: Scenes x-xi

- Act III: The Exorcism: Scene i

- Act III: The Exorcism: Scene ii

- Act III: The Exorcism: Scene iii

- Act III: The Exorcism: Scene iv

- Act III: The Exorcism: Scene v

- Act III: The Exorcism: Scene vi

- Character Analysis

- Critical Essay

- Essay Questions

- Cite this Literature Note

Critical Essay The Significance or Implications of the Titles of the Acts

Most dramatists do not give titles to the individual acts within a drama. When we encounter a drama in which each act has an individual title, we must consider whether or not the dramatist is making a further statement about the nature of his drama. In Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, the titles of each of the three acts seem to reinforce the content of each act and also to call attention to some of the central motifs in the play itself.

Act I of any drama introduces the characters, themes, subjects, and ideas that will be prominent both in the first act and throughout the drama. The title of Act I, "Fun and Games," suggests part of the theme of the entire drama — George and Martha's complex game of avoiding reality and creating illusions. Therefore, the title of the first act introduces the use of games as a controlling idea for not only the first act, but also for the entire drama with the last game, "Killing the Kid," being the game that also ends the drama.

Even though it is not the first use of a game, the first mention of the word "game" comes from Nick. In fact, perhaps Nick's most astute perception of the entire night occurs immediately after his and Honey's arrival. After being "joshed" about the oil painting, and after being trapped in a semantic exchange about why Nick entered the teaching profession, George asks Nick if he likes the verb declension "Good, better, best, bested." Nick perceptively responds: " . . . what do you want me to say? Do you want me to say it's funny, so you can contradict me and say it's sad? Or do you want me to say it's sad so you can turn around and say no, it's funny. You can play that damn little game any way you want to, you know!" The use of the word "game" calls our attention to the concept of games in the play. In the game of "Good, better, best, bested", Nick realizes that the game is one in which one person manipulates another person. However, teasing, criticizing, ridiculing and humiliating another person is a one-sided game, and after a point, there is a revolt. Nick revolted early against George's teasing and toying with him. George will also later revolt against his own humiliation at the hands of Martha. In a later scene, Nick, in a moment of confusion, tells George and Martha that he can't tell any more when they are playing games and when they are serious. Because of this, it is a long while before Nick "sees through the game" and realizes that George and Martha's child is imaginary. Thus in one way or another, most of the behavior of the evening can be classified as a game whether names and rules for the games are established or not.

Implicit also in the term "game" is the idea that a game must have a set of rules. When the rules are violated, then the game takes on other characteristics. George and Martha's life together has been one in which they have consistently played games, but the rules have often been changed. Martha's great reliance on George is that he "keeps learning the games we play as quickly as I can change the rules." Until this night, their game about their kid has been one in which there was only one rule — that is, that the entire game must remain completely private between them. Between themselves, they have often changed the rules (Was it an easy delivery or a difficult delivery? Were his eyes blue, grey, or green with brown specks?), but the rule of privacy has never been violated until now. Martha's violation of this rule, then, affects the remainder of the drama.

In addition to the above mentioned types of games, the following types of games illustrate how completely Albee has used the concept of "game-playing" as a controlling metaphor of his play.

The play opens with a guessing game in which Martha tries to get George to identify a line from a movie they have seen. Variations of guessing games or identification games are found in every echelon of American society from television to academic surroundings.

The early announcement of a party implies fun and games since a party is a type of game, especially since Martha screams with childish delight "party, party" with the doorbell chimes.

The use of the nursery rhyme or game of "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf" is first mentioned by George and Martha, mentioned again by Martha to Nick and Honey and then is used to close the act as a raucous duet by George and Honey amid crashing violence. The game is emphasized as a central motif throughout the first act and, of course, the drama itself closes with George softly crooning "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?" to Martha.

It is a type of game when George, who has been forced to play the role of houseboy, has so manipulated Martha that as he opens the door, she screams "Screw You" toward Nick and Honey. The many attempts to "screw" one another in one way or another become a type of a game.

Fun and games are again the subject of conversation when each recalls the party at Martha's father's house where Nick and Honey "certainly had fun."

The incessant interplay or demonstration of wit, whether between Nick and George or between George and Martha pervades the entire act. The game of guessing who painted Martha's picture, or the game of "good, better, best, bested" are word games that are basic to the human personality. In the declension game, as with other games, the game itself implies other things since George himself has been somewhat "bested" by life and certainly by Martha. The various uses of wit throughout the act and especially the unintentionally comic comments by Honey continue throughout the act.

Throughout the act, from George's first warning Martha not to "start on the bit about the kid," George and Martha's most intimate and private game — that of their imaginary son — is significantly hinted at and becomes the central idea of the play. For example, when Nick asks George if they have any children, George answers as would a child in fun and games: "That's for me to know and you to find out."

The faculty sport "Musical Beds" is a satiric take-off on the old parlor game "Musical Chairs" and, as the name implies, becomes an adult game by way of the sexual allusions.

There are also frequent references to various types of sporting games or sporting events such as handball or football, but more importantly, there is Martha's narration of the boxing contest between her and George and much of the entire act can be viewed as a verbal sparring match between George and Martha with Martha being the victor by the end of the first act.

George's trick with the toy pop gun which shoots out a Chinese parasol is a fun type of party game. It fits in with George's earlier comment when he finds out that Martha has invited someone over, in that Martha is always "springing things on me." The surprise of the pop gun, then, is George's "springing something" on Martha.

Act I also introduces the various imaginative, alliteratively named games that will be played — "Humiliate the Host," "Hump the Hostess," "Bringing up Baby," "Get the Guest," "The Bouncey Boy," and "Kill the Kid." Later on, other games such as "Snap the Dragon" and "Peel the Label" will also be played.

Early in the act when Nick threatens to leave because he fears that he has intruded upon a private family argument, George tells him it's all a game — that we are "merely . . . exercising . . . we're merely walking what's left of our wits."

When Martha changes her clothes, it is so that she can make a deliberate play for Nick. As George points out, Martha hasn't changed for him for years, so her actions must have significance in that she "plays" on Nick's ambitions.

The entire first act and the entire drama "plays" before an audience as though it was one gigantic game in which no one really knows the rules.

The titles of the second and third acts make a rather direct comment on the action of each act. The title of Act II, "Walpurgisnacht," refers to the night of April 30 which is the time of the annual gathering of the witches and other spirits at the top of Brocken in the Harz Mountains located in Southern Central Germany. It is sometimes referred to as the Witches' Sabbath. During this night, witches and other demons dance, sing, drink, and become involved in all sorts of orgies. This is a night where any type of behavior can be found among the participants, and in literature, or in general language, the term "Walpurgis Night" has come to refer to any situation which possesses a nightmarish quality or which becomes wild and orgiastic. Thus, in Act II, as Honey proceeds to get extremely drunk, the others, especially Martha and Nick, dance in an obvious sensual, semi-orgiastic manner. The scene ends in a bizarre manner — a fifty-two-year-old woman takes a twenty-eight-year-old man upstairs for a seduction while her husband quietly reads a book with full knowledge of what is happening upstairs.

In Act III, "The Exorcism," we see the meaning of the term "exorcism" being applied to Martha. During the course of the act George eerily recites the Kyrie Elieson and uses incantations, adjurations, and other necessary devices in order to free Martha of the illusion that their "child" exists and to bring her back to a world free of fantasy.

Previous Honey

Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf Edward Albee

Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf by Edward Al...

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Material

- Study Guide

- Lesson Plan

Join Now to View Premium Content

GradeSaver provides access to 2357 study guide PDFs and quizzes, 11005 literature essays, 2763 sample college application essays, 926 lesson plans, and ad-free surfing in this premium content, “Members Only” section of the site! Membership includes a 10% discount on all editing orders.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Essays

The hidden wish of words: albee's who's afraid of virginia woolf and three tall women anonymous, who's afraid of virginia woolf.

A reader reading Albee will not fail to notice tricks of language in operation; a more interesting analysis is to consider how the characters themselves are aware of language, of reading and being read, as a text, by other characters. AlbeeÃÂÂs...

Truth or Illusion? Hadeel Asaad

Truth or illusion? When the fantasy world people create in order to cope with the absurdity of life is brought too far into reality, it becomes hard to distinguish between authenticity and fiction. This ambiguity is apparent in both Edward Albee's...

The War of the Women Geoff Cowper-Smith

Many of Edward Albee's plays are "overrun with devouring mothers, castrating wives, and remote husbands. . ." (Hirsch 18). As a result, a typical Albee marriage is one of domestic warfare. The women endlessly battle with their men in order to...

Appearance Versus Reality in Three Contemporary American Novels Anonymous College

Appearance versus reality is a major theme of contemporary American fiction. The characters of American Pastoral, We Were the Mulvaneys, and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf may appear to be living one way, or portray a strong public face, but the...

Keeping Up With the American Family; Analyzing the Superficial Pursuit of the American Dream in Edward Albee’s Work Anonymous College

Our founding fathers were committed to creating a perfect society, free from the “corruption and oppression of the west they left behind” (Holtan). As America aged, this idea of American perfection developed into an image, The American Dream. By...

The Character Who Wasn't There: Daddy in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Miriam Fernando 12th Grade

In the drama Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Edward Albee meticulously constructs Daddy as a character who is both ever present and tied to the representation of major themes in the play. Albee uses the looming yet absent presence of Daddy to...

Truth and Illusion Themes Sophie Thomas 12th Grade

As an Absurdist, Albee believed that a life of illusion was wrong as in consideration it created a false content for life, it is therefore not surprising that the theme of ‘truth and illusion’ throughout Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf plays a...

Skilled with Words, for Better or Worse: An Assessment of George's Character Reilly Salmon 11th Grade

“Of the four characters in the play, George is the character most adept at ‘doing things with words’” How far do you agree with this statement?

The phrase, ‘doing things with words,’ can be interpreted in different ways; one effective way to...

“We Complete Each Other in the Nastiest, Ugliest Way Possible”: The Incorporation of Flawed Marriage in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, The Great Gatsby, and Gone Girl Matt Rosenthal 11th Grade

Marriage will always have its share of imperfections, subtle and explicit, but the espoused in Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, and Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl suffer from a bundle of...

Now You See Me Lindsay Talley College

David Kotkin, more commonly known as David Copperfield, was the world’s highest-paid magician in 2017; his net worth is over $850 million (Cuccinello). It is impossible to become as successful as him without providing a good or service that is in...

The use of barriers and their significant effect on the progress and impact of "Who's afraid of Virginia Woolf" and "A Streetcar Named Desire" Arianne Flit 12th Grade

In many dramatic works, the use of barriers is crucial - they determine the play’s developments and how much it will affect the audience. This is certainly the case of “A Streetcar Named Desire” and “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”. The former,...

Study Like a Boss

Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf

In Albee’s play, he reveals the shallowness and meaninglessness of contemporary society, and exposes the falsity of “The American Dream”. In doing this he refers to many different facets of society such as alcohol, social conventions, measures of success and corruption on a number of levels. Violence manifested in both language and action, reflect the frustration of the characters in not being able to live up to society’s expectations. “The America Dream” is a life lived to, or close to, perfection.

In brief, this perfect life is achieved by having a good education, go into a well paying career of which you enjoy, raising a family with the 2. 5 children, and then finally dying in piece without ever having to look back on your life with disappointment. It is said that whoever has goals and sets them are capable of achieving them as long as they are willing to work hard for it. But “The American Dream” is just what is says, it is just a “Dream”. It is a dream dreamt by many. An immigrant coming to America or any western civilization has these dreams.

The dream of being able to live a life of perfection, a life of freedom. Edward Albee takes this “American Dream” and conveys it in it’s true form in his play, Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?. In writing this play, he exposes the falseness of “The American Dream” and shows the audience of what this “Dream” really consists of. When asked of what exactly “The American Dream” is, people often reply with uncertainty and doubt in their answers. “The American Dream” does have it’s definition, but since it is only a “dream”, reality in comparison is almost an exact opposite.

Persons who are not familiar with this reality and still dream this dream, has been falsely informed, and do not know what the reality is. This reality is full of illusion, falseness, and deceit. In his play, Albee takes western society as a whole and places it under one household. He shows what western society is through his characters. He shows “The American Dream” in it’s true form and not as it has been put out to be. In just one night, factors of western society are conveyed – violence, alcohol, lies, deceit, conflict, – along with those who participate.

Through his characters, Albee was able to reveal the different types of people who make up society today. Each character represents the different approaches people have taken towards reality and life. Those who are still young and have not really experienced life and are therefore kind of clueless is represented by Honey while those who have had a good education, has a bright looking future ahead of them, and looks to become very successful, those who have been named “yuppies” are represented by Nick. He is “the wave of the future”.

In a sense, “The American Dream” is actually represented by Martha’s farther who does not actually appear in the play but is frequently brought up into conversation by George and Martha. “The American Dream” is something everyone wants and to get to it they must follow a blueprint. This blueprint is Martha’s father. He is someone who is looked up to by others and these others try to replicate him. His steps should be followed directly and if so, there you have “The American Dream”. But followers aren’t always successful in the following of the blueprint.

Their inability to do so may include many factors. Not many people know that “The American Dream” require more than just pure effort. There are other things which cannot be controlled. It is said that as long as you give all of yourself, you will succeed. But what if your all is not enough. This is the case with George. “… he was … A great big flop” As the daughter of “The American Dream”, Martha has taken life and reality very lightly. She is without real care and believes that she does not need to follow the blueprint of “The American Dream”.

She doesn’t put in the effort and therefore lives life and reality with a lot of instability. She is only able to go through life without failure because she is daughter of her father. Without the fact of being her father’s daughter, Martha would have lived a very very poor and unhealthy life. Nick and Honey have only recently arrived into town and are just still settling in getting to know the place. Nick and Honey represent the many young couples in today’s society. They were married at a young age, and married for a non traditional reason.

They know from what they have been told through their education but they still do not have knowledge from their own experience to life. In only recently coming to town, Albee uses this to convey the message that Nick and Honey have only recently arrived to life and reality. They have just recently arrived and are trying to get settled in and learn the ropes of life and reality. As the night continues, more and more do Nick and Honey learn just like how any teenager today would learn about life and society as it is today. They learn about the falseness about “The American Dream” and what it truly is.

As the play continues through the night, more of today’s western society is implemented into this micro-society that Albee has created within the play. Violence, conflict, and the use of alcohol are more of the important ones that Albee has implemented. The use of alcohol throughout the play is very extensive. This shows that Albee feels very strong about the subject of alcohol abuse in today’s western society. Albee shows that the true “American Dream” as a reality can be so bad that people who are not able to cope with it resort to the use of alcohol as a way of release from reality.

Along with alcohol, those who aren’t able to cope use fantasy to escape from the pressures of life. Instead of facing up to reality, people create their own “reality”. They create these false realities to help them cope with or just totally escape true reality. This is a path taken by many because it is an easy way out. This “reality” that they have created is very malleable and can be shaped to meet their needs. This is the case with Martha. Martha has not taken life and reality as it is and just tried to live with it.

She is unable to cope with reality and so creates he own “reality”. But with creating her own reality, she has not been totally fictional but has blended both reality and her “reality” into one. She took her life problems and copes with them in her own little way – by creating her own world in which she can more easily cope. In creating her own reality, she becomes very involved into her made up world and almost nearly forgets about reality. As long as more problems come into her life, instead of facing them head on, she quickly converts them to snugly fit into her own “reality”.

Her son, for example, has been manifested to use as a kind of tool for her and George to use. “… he’s a bean bag. ” Martha uses her son to cope with her problems with George a lot easier. Both Martha and George use their son to get at each other’s throats instead of having to do it directly. But Martha becomes so immensely involved in her “reality” that she has created which has combined true reality with hers that in the end, she has confused herself in that she is no longer to tell the difference between the true reality around her and the reality that she has created.

Truth and illusion. Who knows the difference? ” Through the play. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? , Albee has been successful in conveying the falseness of “The American Dream”. He has taken western society as it is today as whole and has shown his audience the reality of “The American Dream” in it’s true form. He has stated that ‘The American Dream” is only an illusion. The play is his, “demonic urge to expose what he takes to be the falseness of the American Dream” (Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? study guide).

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Related posts:

- Thematic Concerns Of Whos Afraid of Virginia Woolf

- Edward Albees play Whos Afraid of Virginia Woolf

- Religion In ‘Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?’

- The Satire in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf

- Edward Albee Biography

- the novel, To the Lighthouse, Virginia Woolf

- To The Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf

- Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse

- Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf

- The Life Of Virginia Woolf

- Inside Virginia Woolf

- A Life Virginia Woolf Shared

- The Two-Dimensional Character of Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse

- One of the greatest female authors of all time, Virginia Woolf

- Romeo And Juliet – Whos To Blame

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

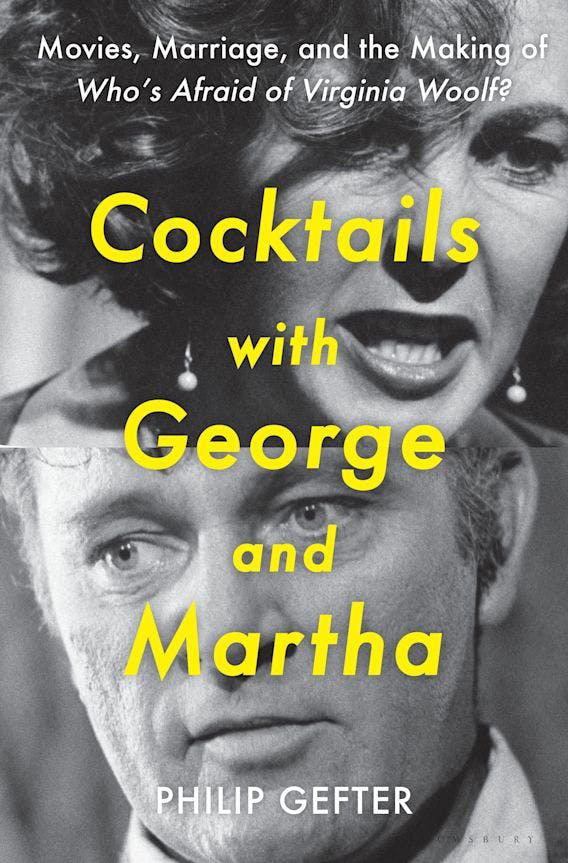

The Drama of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Spilled Into Real Life

M any of us who grew up in America’s middle-class suburbs of the 1950s and ’60s rarely experienced the ideal families encountered on television sitcoms—the Cleavers, Petries, and Father Knows Bests who just didn’t suffer serious emotional conflicts beyond minor disagreements about redecorating the den or locating a misplaced homework assignment. Where were all those wise and always-patient dads who hung around the living room with a tidily unfolded newspaper? Or the mothers who wore pearls in the kitchen while cooking meat loaf? Most chaotic homes, schools, and neighborhoods just didn’t match up with these well-regulated and geometrically laid-out open-plan kitchens and playgrounds.

My younger brother and I first saw Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? in the company of our fairly inebriated, Martha-like mother at the Serra Theater in Daly City, California, not long after my parents separated for the third and final time. I was 11 or so, and my brother three years younger; it was a theater where our mother often dragged us to see “grown-up” movies she didn’t want to see on her own, and while it was a perplexing movie (to say the least), it certainly made a lot more sense than other movies she dragged us to during those years. (I’m still not sure what actually happened in Antonioni’s Blow-Up. ) And later, it was one of the few “grown-up” books I actually took down from the shelves of my parents and read for myself.

For while the references to people like Bette Davis or even Virginia Woolf didn’t mean anything to us, the intense, psychodrama-laden scenes did. It opened the window on lives I recognized, however dimly. And the parade of emotions—rage, tenderness, passion, vengefulness, and jealousy—were a lot more interesting than the superficially emotionless range of my own life, where nobody really hated anybody; they were only trying to do what “was right for the kids.” It may have been the first adult movie that made me realize that adults had no better idea how to live their lives than us kids. And that given half a chance, they could loudly articulate their dissatisfaction to anybody who would stick around long enough to listen.

As Philip Gefter writes in the introduction to Cocktails with George and Martha , Edward Albee’s most notorious play didn’t simply affect theater and moviegoers as a night’s entertainment; it barged into their lives and made a home of them. And the relationships it forged with audiences would last decades. It acted as both shock and revelation. It embraced both love and hate at significant volumes. It featured glamorous actors playing unglamorous parts, and its humor was often indistinguishable from its emotional horrors, and vice versa. It was a “big,” expensive movie set in a shabby on-campus faculty home, in a low-budget roadhouse, and on a leaf-strewn country road late at night. And the characters didn’t achieve great things or suffer great losses. They simply endured one another and, to an equally large extent, enjoyed one another. They were people without a mission living their lives without any purpose but each other.

Like many of his generation, Gefter recalls his teenage experience of watching Woolf as a sort of open secret, and while he “couldn’t really make sense of it,” he “recognized his parents in it, as well as the parents of my friends.” It was like making contact with a “rumbling beneath the polite surface of those suburban marriages.” Unlike previous family dramas, these “rumblings” weren’t driven solely by alcohol (as in Eugene O’Neill) or the hard day’s work of men and women coming home every night to nothing (Arthur Miller and Clifford Odets). In Albee, these strong emotions and dissatisfactions emerged from the marrow of intelligent, passionate, sometimes monstrous (and very often hilarious) men and women.

Albee’s upbringing made him the perfect person to write about the deep pathological weirdness of American family relationships. Born in Washington, D.C., in 1928, Albee never knew the identity of his biological parents (“I’m sure my father wasn’t a president or anything like that”), and was adopted in infancy by a wealthy Wasp-ish couple who took him off to their “stately mansion” in Larchmont, New York, where he learned to make Old Fashioneds for his grandmother and to treat expensive leather-bound books as interior decor rather than, you know, things you actually read. Albee’s adopted parents raised him to be so thoroughly acceptable to their world that he soon felt unwelcome in his own body, the mother spouting “cracks” about ethnic minorities and homosexuals while the father slumped more and more deeply into a distant, angry complacency.

Even the headmaster at a private school where Albee spent one of his truncated, Holden Caulfield–like tenures, sympathized with this “pathologically shy” (as Albee recalled himself) boy more than with his awful parents: “Ed is an adopted child and, very confidentially, he dislikes his mother with a cordial and eloquent dislike which I consider entirely justified.… She is, in my opinion, a selfish, dominating person, whereas Ed is a sensitive, perceptive, and intelligent boy.” The parents continually denounced homosexuals throughout the years when Albee was beginning to understand himself as one. Everything about him seemed to disgust and offend them.

In possibly his funniest play, a 1961 one-act titled An American Dream, a template-like family of “Mommy,” “Daddy,” and “Grandma,” is so disturbed by the intractable unpleasantness of their adopted baby that they begin whittling off offensive parts until there’s nothing left. For Albee, the nuclear family was as rich with destructive potential as the nuclear bomb. This early play, Albee later wrote, served as “an attack on the substitution of artificial for real values in our society, a condemnation of complacency, cruelty, emasculation and vacuity; it is a stand against the fiction that everything in this slipping land of ours is peachy-keen.”

Like the horrible family in this early play, there would be nothing “artificial” or “peachy-keen” about George and Martha. They would be true to everything about themselves with all the passion, recriminations, and rage they could muster.

As a young man, Albee flew far and fast from the upper-crust home where he was raised, and soon found a new family (and perhaps a firmer, less perilous sense of identity) with the ’50s-era Greenwich Village art crowd, where being gay wasn’t considered an act of class treachery. His friends included Ned Rorem, Kenneth Koch, Frank O’Hara, Terence McNally, and Albee’s first long-term lover and roommate, composer and music critic William Flanagan. (Their often tempestuous relationship was later noted by friends as one of several inspirations for George and Martha.) But even while these new living arrangements liberated him from the world of his parents, it took several years to discover where he wanted to go creatively, and it wasn’t until Thornton Wilder suggested he try his hand at theater that Albee’s creative abilities took off.

With his first one-act play, The Zoo Story, he found his groove by depicting the randomly confrontational Jerry, who verbally assaults a total stranger on a park bench; Jerry was the first of Albee’s wild, unconventional characters who brought a lawless rage everywhere he went. Considered one of America’s first proponents of “absurd” theater (Albee learned his craft while attending performances of Beckett, Brecht, and Pirandello), his characters didn’t strive against the world’s absurdities but rather launched themselves absurdly against the dull, passive nature of suburban reality. The world wasn’t absurd enough, they seemed to argue. Americans needed to wake up to the fact that they weren’t any better than the animals they visited in zoos, and should probably be caged up themselves.

Zoo Story, initially performed in Berlin in 1959 and only appearing in New York many months later, staged one of Albee’s first dialogues-to-destruction between his principal characters. But as in everything he wrote, the dialogues were rendered in profound, emotive, beautifully written prose, almost musical in its rhythms, brooding resonances, and lyrical dislocations. As his friends Ned Rorem and Terence McNally pointed out, Albee wrote like a composer.

In retrospect, one of the most peculiar aspects of Albee’s early career was how shocking his work seemed to sensibilities at the time; it was as if Americans were asleep to their own contradictions until Albee transformed them into such stirring theater. Not only was his first full-length play, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, greeted as profane and sui generis at its New York premier in October 1962, but it attracted two major theatrical stars of the time, Uta Hagen and Arthur Hiller; and even some of the major actors who turned down the leads weren’t happy about it. (Katherine Hepburn claimed she wasn’t a good enough actress to play Martha; and when Henry Fonda learned the part of George had been turned down by his agent, he fired his agent.)

On its premier, Woolf received the sort of strongly negative and strongly positive reviews that made it clear something important was happening—it’s just that nobody agreed on what that important thing was. It was both hailed and condemned as a “cause célèbre,” and eventually criticized for representing something referred to as “homosexual theater,” even while Albee was refusing offers to stage the play with men in all four parts. Then, after a sold-out first few months on Broadway, it was turned down for the Pulitzer when at least one judge confessed (somewhat proudly) that he hadn’t seen the play. He just didn’t like what he heard about it.

Among those to see the play’s first stage production was Ernest Lehman, the man who would go on to produce and write the screenplay for its film adaptation. Best known at the time for emotionally uncomplicated hits, such as Hitchcock’s North by Northwest or Robert Wise’s The Sound of Music , Lehman almost reluctantly attached himself to the project after being dragged by his wife to the L.A. production: “I was totally destroyed in that audience with people I knew seated all around me … trying to conceal sobs that were coming out of me.”

The play’s raucous, near-Bedlam intensities went on to infect its filming and production, where George and Martha’s dinner party “games” such as “Get the Guest” were soon transformed into their studio equivalents, such as “Get the Producer” or “Get the Director.” With such a varied assortment of talents, it’s surprising anything ever got done at all. First there was the young and weirdly successful Mike Nichols as director, already twice divorced at 33, suffering from lifelong alopecia that caused him to wear a wig every day of his life; he had already enjoyed two successful careers—as half of an eccentric, hilarious comedy team with Elaine May and subsequently as a Tony award–winning director of Neil Simon comedies Barefoot in the Park and The Odd Couple . He had just the right sense of humor to recognize that Woolf was, to a large extent, funny. (He later said that there were so many jokes coming along so fast it convinced him to use overlapping dialogue, which at the time was a Hollywood taboo.)

With the support of his friends Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, who were already well anointed by the tabloid press as simply “Dick and Liz,” Nichols quickly insinuated himself into the production as a first-time film director, where he managed to bring in one of the most over-budget movies in Hollywood history. With a reputation for brilliance (it’s hard to find anybody who knew Nichols refer to him as anything less than a “genius”), he learned to make movies by directing one, bringing on board other young mavericks, such as cinematographer Haskell Wexler—who spent much of his time building huge contraptions to track intimate close-ups of the always-moving principal actors—not to mention new-to-film youngsters like Sandy Dennis and George Segal.

Then of course there were Liz and Dick themselves, already notorious for leaving their spouses on the set of Cleopatra —where, when the director shouted “Cut!” during a kissing scene, they carried on without him. They came to Woolf with a combined passion for the material, Burton’s sometimes disruptive concern about his pockmarked face during close-ups, and an extra 30 pounds added to Liz to bring her up to Martha-like proportions. Taylor was so excited by the opportunity to play the part that she even agreed, for the first time in her career, to rehearse scenes. (As it turned out: She loved it.) With a pair of huge contracts that limited their on-set work to five days per week between 10 and six, they were often disappearing into four-hour lunches or midday chats with visiting celebrities, such as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor; at other times they were off making love, or getting drunk and buying one another lavish gifts whenever the mood struck them.

Meanwhile, when Nichols wasn’t conspiring to keep them in character for the next scene, he was name-dropping the principals in his social calendar, just to annoy Lehman, or trying to overcome Jack Warner’s latest resistance to filming the movie in black and white. At one point, when Warner was “apoplectic” about an upcoming “Decency Code” decision at the Catholic Office of Motion Pictures, Nichols flashed his Rolodex and arranged for his friend Jacqueline Kennedy to sit behind Monsignor Thomas Little at the screening, and voilà. To everyone’s surprise (especially Jack Warner’s), the film was approved.

“Mike’s a very disturbing man,” Burton informed journalists during filming, with his tongue very firmly stuck in at least one of his cheeks:

You cannot charm him—he sees right through you. He’s among the most intelligent men I’ve ever known, and I’ve known most of them. I dislike him intensely—he’s cleverer than I am. But, alas, I tolerate him.

It was just the sort of creative aggression mixed with genuine affection that informed Albee’s play.

In many ways, both the play and film adaptation of Woolf established themselves in the collective psychology of ’60s America as a sort of primal family romance of Mommy and Daddy and Sonny and Sis that wasn’t as ugly as it might at first seem. Certainly it brought the representation of American family dysfunction a little closer to reality. Next came along PBS’s An American Family, in which the photogenically smiling Brady Bunch–like Mom, Dad, and kids slowly dissolved (before our weekly eyes) into George and Martha–like scenes of sadness, embitterment, and loss. From which point the nightmare of American familyhood was the only game in town—whether it was Archie Bunker perorating about race from his antimacassar-adorned armchair, or Homer Simpson belching out beer and donuts, or the Addams family colonizing suburbia with happy monsters.

For as Gefter makes clear in his charming book, filled with enjoyable anecdotes and recollections of how Hollywood accidentally makes great movies from time to time, the saga of George and Martha isn’t really a tragedy of failure, in which (like Richard Yates’s Wheelers in Revolutionary Road ) a marriage falls apart; rather it’s a comedy in which the principal characters almost inevitably go upstairs to bed together in a nightly reiteration of the marriage ceremony. As Martha confesses in her penultimate monologue—and in Taylor’s unforgettable performance—the only man who ever made her happy was always and forever the endlessly tormented and tormenting George:

George , who is out there somewhere in the dark. Who is good to me, who I revile. Who can keep learning the games we play as quickly as I can change them. Who can make me happy—and I do not wish to be happy. I do wish to be happy. George and Martha, sad, sad, sad. Whom I will not forgive for having come to rest, having seen me, and having said, yes , this will do. Who has made the hideous, the hurting, the insulting mistake of loving me. I must be punished for it. George and Martha, sad, sad, sad …

It’s almost like hearing one of Schubert’s Lieder with the dark undercurrent of sadness and remembered happiness all rising and subsiding together with the rhythms of words and emotions. George and Martha. Sad, sad, sad.

Like Gefter, I have rewatched this movie many times over the decades with an always-increasing affection for George and Martha, two monstrous images from my childhood who seem so much less monstrous to me now. I’ve even spent some interesting evenings with couples who remind me of them—utterly human people who were unpredictable, surprising, and thoroughly unashamed of their own rages and passions and the often bizarre lives they lived together. (There have even been times when I felt a bit George and Martha–like myself.) Most of all, they were people who were never boring and who rarely pretended to be anybody but themselves.

Which is probably why so many of us are at least a bit intimidated by the idea of going for post-midnight cocktails with George and Martha. And why, if given half a chance, we’d probably jump at the opportunity to go again.

Spotlight: WHO'S AFRAID OF VIRGINIA WOOLF? at Flint Repertory Theatre

Flint Repertory Theatre presents Edward Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf Mar 22 - Apr 7

It’s 2AM and George and Martha are just getting started. The middle-aged married couple, a once-promising historian and his boss’s frustrated daughter, welcome a younger professor and his wife for a nightcap—only to ensnare them in increasingly dangerous rounds of fun and games.

An unblinking portrait of two American marriages, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf ? is Edward Albee ’s explosively comedic and harrowingly profound masterpiece. S

cenic and Costume Design by Scott Penner . Lighting Design by Mike Billings . Sound Design by Taylor J. Williams. Fight & Intimacy Direction by Alexis Black . Stage Managed by Ernie Fimbres .

Genesee County residents receive 30% off – discount applied at checkout.

Flint Repertory Theatre’s production of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf ? contains adult themes. Recommended for middle school students and up. Understanding that sensitivities vary from person to person, patrons are advised to contact the FIM Ticket Center at 810.237.7333 or tickets.thefim.org if you have any questions about program content.

Michigan SHOWS

Recommended For You

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Joe Flaherty, ‘SCTV’ and ‘Freaks and Geeks’ Actor, Dies at 82

Mr. Flaherty first became known for playing a series of oddball characters on one of TV’s most influential sketch shows. He was later a familiar face in film and on TV.

By Amanda Holpuch

Joe Flaherty, the comedic actor best known for his work on the influential sketch comedy series “SCTV” and as a father on the short-lived NBC ensemble series “Freaks and Geeks,” died on Monday. He was 82.

His death was confirmed by his daughter, Gudrun Flaherty, who said that he died after a “brief illness.” She did not specify a cause or say where he died.

Mr. Flaherty played a variety of characters on “SCTV” as part of an ensemble that over the years included John Candy, Martin Short, Rick Moranis, Andrea Martin, Catherine O’Hara, Eugene Levy, Dave Thomas and Harold Ramis. The concept of the series, which aired in the 1970s and ’80s, was that its sketches were shows, or previews of shows, on a low-rent TV station in a fictional town called Melonville.

Among Mr. Flaherty’s characters were Guy Caballero, the sleazy president of the station, and Sammy Maudlin, an unctuous late-night talk show host. His character Count Floyd wore a cheap vampire costume while hosting a horror movie show, “Monster Chiller Horror Theater.” The joke was that the movies the program showed — for example, “ Dr. Tongue’s Evil House of Pancakes ” — were seldom very scary, leaving Floyd holding the bag and often having to apologize to viewers.

Gudrun Flaherty said in a statement that her father had an “unwavering passion for movies from the ’40s and ’50s,” which influenced his comedy, including his time on “SCTV.”

Mr. Flaherty was also known for roles on television shows and in films that were cherished by fans.

He played Harold Weir, the no-nonsense father of two awkward teenagers, on the cult television series “Freaks and Geeks,” which premiered in 1999 and ran for only one season, but helped launch the careers of several young actors, including James Franco, Seth Rogen, Busy Philipps, Jason Segel and Linda Cardellini.

In the 1996 film “Happy Gilmore,” Mr. Flaherty had a small but memorable role as a man who taunts the title character, a golfer played by Adam Sandler, from the crowd.

Joseph O’Flaherty was born on June 21, 1941, in Pittsburgh, the eldest of seven children, according to a 2004 profile in The Globe and Mail . His father was a production clerk at Westinghouse Electric, and the family struggled financially. “I still remember nuns from the church bringing us food,” he said.

After graduating from Central Catholic High School, he joined the Air Force at 17. He had taken a class at Pittsburgh Playhouse before enlisting, and after leaving the Air Force, he returned to the theater to take more classes, he told WESA Pittsburgh , the city’s NPR station, in 2016.