- Advanced Search

Version 1.0

Last updated 15 august 2019, alliance system 1914.

Alliances were an important feature of the international system on the eve of World War I. The formation of rival blocs of Great Powers has previously considered a major cause of the outbreak of war in 1914, but this assessment misses the point. Instead of increased rigidity, it was, rather, the uncertainty of the alliances’ cohesion in the face of a casus foederis that fostered a preference for high-risk crisis management among decision-makers.

Table of Contents

- 1 Introduction: Alliances and Great Power relations in Europe, 1815-1871

- 2 Dual Alliance and Triple Alliance

- 3 Franco-Russian Alliance and Triple Entente

- 4 Great Power Alliances on the Eve of War

- 5 Conclusion: 1914 - Have Alliances Failed?

Selected Bibliography

Introduction: alliances and great power relations in europe, 1815-1871 ↑.

Alliances were nothing new to international relations in modern Europe. The patterns of cooperation in the first half of the 18 th century had become so familiar that switching strategic partners in preparation for the Seven Years War was dubbed as “ renversement des alliances ”. However, with religious and ideological issues only of marginal relevance to the cabinets of Europe, war-time alliances could be overturned quite easily. The French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802) and Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) put Great Britain and France in the role of perennial adversaries, both of them forging alliances with other powers if useful and possible. Paul W. Schroeder has argued that the anti-Napoleonic coalition of 1813-1814 proved to be a turning point in international relations, because the four major coalition partners - Great Britain, Russia , Austria , and Prussia - decided to put their alliance on a peace footing after the end of war in 1814 and the Vienna Settlement of 1815. The Quadruple Alliance was meant to guarantee the peace of Europe by keeping a watchful eye on France and to cooperate closely to thwart any threat to international stability on the continent, while the Holy Alliance (originally consisting of Russia, Austria and Prussia) added glamorous rhetoric to this idea. According to Schroeder, traditional balance of power policy gave way to a collective effort among the Great Powers to defend the rights and mutual obligations of all sovereign states, big or small. With France co-opted in 1818, the five Great Powers became known as the Pentarchy. The Pentarchy discussed problems related to the situation of smaller states and decided on solutions to them, a de-facto privilege of the Great Powers in a Europe of sovereign states with different level of strategic clout. Although conflicts among the Great Powers would set limits to their close cooperation in the following decades, the Concert of Europe was still at play in the debates about Balkan crises in the years and months prior to the outbreak of war in 1914. [1]

At its heyday, in the first years after the Congress of Vienna, the new consensus among the Great Powers was strong enough to make separate alliance treaties between some of them seem irrelevant. In the 1820s, with disputes over the future of Spain and her former colonies in Latin America and divergent intentions in the Eastern Question, Great Power relations were transformed. New alliances were forged between Britain and France and between the conservative monarchies of Russia, Prussia, and Austria. The latter was perceived as a bulwark anti-revolutionary policy, the former as a cooperation of more liberal-minded cabinets. With regard to the decline of the Ottoman Empire and its geopolitical consequences, different patterns of alignment emerged in 1840. It was this Eastern Question that sparked the first war between Europe’s Great Powers after the defeat of Napoleon I, Emperor of the French (1769-1821) . His nephew, Napoleon III, Emperor of the French (1808-1873) , was instrumental in the formation of an anti-Russian war coalition in 1853-1854. The Crimean War was a decisive blow to the Vienna Settlement, although the peace treaty of Paris in 1856 reiterated the idea of a Concert of Europe. It left Russia reeling from defeat and encouraged further revision of the international system. Alliances became important tools in the ensuing transformation of Europe. Secret treaties between France and Sardinia and Italy and Prussia, respectively, were crucial in the preparation for the wars of 1859 and 1866, and Prussia’s treaties with the southern German states came to bear in 1870-1871. The so-called Wars of Italian Independence and of German Unification changed the map of Europe by creating new nation states. They also left the Habsburg Monarchy and France in a much weaker position. The creation of Germany under Prussian leadership and the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine was the most obvious shift in the balance of power. [2]

Dual Alliance and Triple Alliance ↑

With the creation of nation states in Germany and Italy completed, 1871 marked a turning point in the development of Europe’s international order. In a series of three victorious wars, Prussia had forged the economically and militarily strong German Empire, which now held a particularly powerful position on the continent. After a crisis in the mid-1870s, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898) settled on a course of securing the empire ’s position by isolating France and engaging with the other Great Powers, in particular Austria-Hungary and Russia. Ever the skillful diplomat, Bismarck was able to achieve this much, but he left a difficult legacy to his successors after his dismissal in 1890. It turned out to be particularly difficult to maintain close ties with Russia without encouraging St. Petersburg to wage a policy of expansion on the Balkans . Several times, Bismarck tried to build on the traditional pattern of anti-revolutionary cooperation between the monarchies of the Romanovs, the Hohenzollern, and the Habsburgs. The Three Emperors’ League was agreed upon in a treaty between Alexander II, Emperor of Russia (1818-1881) , Wilhelm I, German Emperor (1797-1888) , and Francis Joseph I, Emperor of Austria (1830-1916) in September 1873. It evoked the spirit of the Holy Alliance, but would not survive the clash of interests between Austria-Hungary and Russia that developed just a few years later over the expansion of Russian influence in South East Europe and the creation of a Greater Bulgaria in the 1878 San Stefano peace treaty between Russia and the Ottoman Empire. [3]

The Balkan Crisis of the 1870s and the Congress of Berlin in 1878, at which Bismarck did not save Russia from international pressure to give up on the project of Greater Bulgaria, rattled the foundations of the cooperation between the three conservative monarchies of the Hohenzollerns, the Romanovs, and the Habsburgs. An Austrian initiative led to the so-called Dual Alliance, a defensive alliance between the German Empire and the Habsburg Monarchy. The secret alliance treaty of 7 October 1879 assured Austria-Hungary of German military assistance in case of a Russian attack on the Dual Monarchy. Austria-Hungary also committed herself to come to the rescue of her ally in case of a Russian attack on Germany, a highly unlikely scenario. The Germans would get little in return, since the Austrians were under no obligation to come to their ally’s rescue in the case of a French attack on the German Empire. Benevolent neutrality was all they had to promise, unless France would be fighting alongside Russia. [4]

Bismarck wanted to shield the Habsburg Monarchy from Russian aggression and to get a say in Austria’s foreign policy. Without German consent, any diplomatic or military action taken by the Austrians that led to Russian countermeasures might jeopardize Germany’s commitment to the alliance. The casus foederis , Bismarck made clear in the 1880s, would only be triggered if Austria’s actions were first cleared with Berlin and the subsequent Russian attack labeled “unprovoked”. In this way, Bismarck avoided a situation in which the weaker of the allies would be able to steer the stronger one towards war. The German chancellor was not only trying to commit Vienna to close coordination of its Balkan policy with Berlin; he also hoped to make the Dual Alliance the cornerstone of cooperation in other fields and to tie the Habsburg Monarchy to the German Reich in a way reminiscent of the Holy Roman Empire. Gyula Andrássy (1860-1929) , Bismarck’s opponent, refused to have the treaty ratified by parliaments , and it would be kept secret until 1889, when Bismarck published it to deter Russia at the height of the Dual Crisis. [5]

Nevertheless, the Dual Alliance was not considered to be just another international treaty, but rather the foundation and symbol of a special relationship between the German Empire and the Dual Monarchy. The very basis of Austro-Hungarian dualism, the dominating influence of the Germans in Austria and the Magyars in Hungary, was seen as non-negotiable in Berlin, in order to keep Slav aspirations in Europe at bay. German diplomats and politicians would not shy away from telling their counterparts so, but up to a point, the underlying Teutonic, anti-Slav rhetoric also limited Germany’s freedom of action. The term “ Nibelungentreue ”, applied to German-Austrian relations by Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow (1849-1929) in 1909, put a name to the cultural underpinnings of the Dual Alliance that had to be accounted for by German politicians. With Italy staying out of the fray in 1914, the Dual Alliance became the nucleus of what would be called the war coalition of the Central Powers. [6]

The Dual Alliance would be renewed on a regular basis and still existed in 1914, but by that time, most contemporaries had begun to use the term Triple Alliance when they were talking about Germany’s and Austria-Hungary’s most important alliance treaty. As in the case of Germany, the creation of Italy as a nation state had come at the expense of the Habsburg Monarchy. But unlike Germany, where the idea of uniting the German-speaking parts of Austria with the German Empire enjoyed almost no support, the vision of an Italy that included the Italian-speaking regions of the Habsburg Monarchy held considerable appeal for the Italian elites. In addition, the aspiring new – and still not very strong – Great Power Italy was vying with Austria-Hungary for control in the Adriatic. The potential for conflict between both powers notwithstanding, Italy had reasons to cover her back while she was striving for colonial expansion in the Mediterranean. With France blocking Italy’s path by seizing Tunisia in 1881, the government in Rome had to turn to Vienna and Berlin in search of protection in case of future colonial conflicts.

In the Triple Alliance Treaty of 20 May 1882 between Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy, Italy and Germany were promised military support in case of an unprovoked attack by France. If two or more of the Great Powers attacked one of the three alliance partners, the other two would also be required to intervene by force. If only one Great Power forced one of the allies to resort to war, the others were obliged to keep a neutral stance, unless they decided to help militarily. [7] Romania , whose king was a member of the Hohenzollern dynasty, acceded in October 1883. [8] The treaty was meant to be secret, but in 1883 an Italian politician made the existence of the alliance public. Its text would be kept secret, as would the articles that were to be added in later years when the treaty was up for renewal. From an Italian point of view, her allies’ pledge of support in case of a war with France was essential; for Bismarck, the alliance helped to keep France isolated and would, in combination with the Dual Alliance, allay Austrian fears of Russian dominance in South East Europe. Vienna’s intention to preserve the status quo on the Balkan peninsula resonated with British priorities in the Eastern Mediterranean. It was also in Berlin’s interest to see the emergence of an alignment of Italy, Great Britain, and Austria-Hungary. This was formalized in a set of agreements brokered by Bismarck that culminated in a treaty between Great Britain and Italy in February 1887, with Austria-Hungary in March 1887 and with Spain in May 1887. The so-called Mediterranean Entente defused conflicts between Austria-Hungary and Italy, but most importantly, it contained Russia in the Eastern Mediterranean quite successfully in the late 1880s and early 1890s.

In 1891, when the Triple Alliance was to be renewed for the second time, the Austrian minister of foreign affairs suggested to the Italians that an agreement between the two allies should be included, which aimed to preserve the status quo in the Balkans and the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire. But if the status quo “collapsed”, any temporary or permanent occupation of territories in the area should, according to Article VII, “take place only after a previous agreement between the two Powers, based upon the principle of a reciprocal compensation for every advantage, territorial or other.” This article would be part of the renewed and extended versions of the treaty agreed upon in 1902 and 1912. [9] In 1914-1915, Italy would use Article VII to gain leverage in her negotiations with Austria-Hungary over Trentino and Trieste. In the years before, the article kept a lid on Austro-Italian rivalry in Albania . But with Italy seeking British, French and Russian support between 1899 and 1911, the Triple Alliance was no longer essential for Italy’s colonial aspirations in North Africa and in the Eastern Mediterranean. During the Italo-Turkish War of 1911-1912, Rome could count on the tacit support or at least acquiescence of the other Great Powers. As the Ottoman Empire, weakened by the Italian attack on its North African possessions and the ensuing war, came close to collapse in 1912 in its fight against the Balkan League, which had been forged by Russian diplomacy, the Great Powers set up the London conference. The Concert of Europe was meant to contain the shockwaves and to help find viable solutions to territorial disputes when the spoils of war were divided up. The Triple Alliance was renewed for the last time in December 1912, in the wake of the First Balkan War, with tensions between the Great Powers at crisis level. [10]

Although contemporaries were still using the term Triple Alliance, the cabinets in Berlin and Vienna were no longer convinced of Rome’s attachment to the alliance. In Austria-Hungary, suspicions of Italian duplicity were widespread. Rivalry between both allies in the Adriatic and fear of Italian plans to grab Habsburg territory fueled anxieties and inspired military build-up and heavy-handed policing along the border. A naval armaments race between the allies ensued in the early 1900s that would slow down only on the eve of war. By that time, support for the Triple Alliance in Italy’s political elite had waned. Whereas the alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary had been pivotal to Italian efforts to become a modern, respected great power in the 1880s and most of the 1890s, in the early 20 th century, ties to Vienna and Berlin had become a matter of weighing strategic opportunities. [11] Consequently, uncertainties about Italian policy played a significant role in British, French, German and Austro-Hungarian calculations.

Italy was not the only one about to jump ship and seek closer relations with Britain, France, and Russia; Romania was, as well. In both cases, Austria-Hungary stood in the way of the possibility of expanding influence and gaining territories in the Balkans. In the case of Romania, Vienna’s stance during and after the Second Balkan War soured relations. Both in Italy and in Romania, the hope of annexing parts of the Habsburg Monarchy that had a majority population of co-nationals started to gain more traction among publicists and politicians. Fears of such a policy among the political elites in Vienna and Budapest were not without justification, but greatly exaggerated. Nevertheless, those fears fed into a growing sense of instability and imminent threat to the very existence of the Habsburg Monarchy. By 1914, the future of the Triple Alliance seemed to be in question, but many decision-makers in Vienna and in Berlin who started the July Crisis hoped to keep the Triple Alliance – including Romania – together in case of a European war, or at least to be able to count on Italian and Romanian neutrality. Compared to the days of Bismarck’s chancellorship, the German Empire looked more and more isolated in Europe, with only the declining Habsburg Monarchy left as a weak, but reliable ally. [12]

Franco-Russian Alliance and Triple Entente ↑

Until the late 1880s, the French Republic held a rather isolated position among the Great Powers. Colonial disputes with Britain and Italy played a role, but so did the perception of France as a standard-bearer of revolution . Republicanism and revolution were considered deadly threats to Europe in general and to Russia in particular, especially by the tsar and his government . Bismarck had successfully appealed to the tsar’s conservatism in 1873 and did so again in 1881, when Russia, Germany and Austria-Hungary signed treaties that followed the traditions of the Holy Alliance. With the secret Reinsurance Treaty of 1887 between Germany and Russia, [13] Bismarck tried to keep Russia engaged, but a tariff dispute and Germany’s decision to ban the floating of Russian state loans on German markets in 1887 proved counterproductive. After Bismarck’s fall in 1890, the German decision to let the Reinsurance Treaty expire, and the assertive policy of Berlin’s partners in the Eastern Mediterranean in 1891, furthered the alienation between Germany and Russia. French politicians sensed an opening for closer relations with the only strategic partner left on the continent that might help to counter Germany. The detention of Russian anarchists in France made the republic more palatable to the tsar. Financial support was something the French Republic had to offer, but it also had sizable military capabilities. The visit of a French naval squadron to the Russian harbor of Kronstadt 1891 and a Russian return visit to Toulon in 1893 made the realignment public.

It was the French who insisted on a written agreement. In August 1892, the two general staffs signed a military convention that would be endorsed by an exchange of diplomatic notes. Thus, on 4 January 1894, the agreement between the general staffs gained the status of an alliance treaty. Just as in the case of the Dual Alliance, the Franco-Russian alliance was a defensive one. Russia promised support with all her forces available in case of an attack on France by Germany or by Italy with German assistance. The French would do the same if Russia were attacked by Germany or by Austria with German support. Unlike the Dual Alliance or the Triple Alliance treaties, the Franco-Russian agreement was more specific in terms of military aspects. Article 2 regulated mobilization and deployment:

In Article 3, the text even mentioned troop numbers and defined the basic strategic concept of coalition warfare :

Little wonder that Article 4 called for close cooperation between the two general staffs in order to allow for coordinated campaigns in case of war. [14]

Throughout the following years, the allies discussed strategy, operations, and logistics. France supported armaments and the construction of strategic railways in Russia. [15] In 1899, due to a French initiative, the allies agreed to support French aspirations in Alsace-Lorraine and Russian ones on the Balkans. At the time, Russo-Austrian relations had taken a turn for the better and a French conquest of Alsace-Lorraine in the context of a general war seemed farfetched. After she had suffered defeat at the hands of the Japanese in Manchuria and at Tsushima in 1904-1905, and in the wake of revolutionary turmoil in 1905, Russia needed to rebuild her military capabilities. French support and rapid economic modernization allowed for fast rearmament, but not fast enough to save Russia from humiliation in 1909, when a German ultimatum forced St. Petersburg to abandon Serbia in the conflict with Austria-Hungary over the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. But the Bosnian Crisis also indicated a massive change in French and Russian strategic options, because Britain had openly abandoned her commitment to the defense of the Habsburg Monarchy’s role as a Great Power on the Balkan peninsula. Compared to the late 1880s and early 1890s, British policy had changed profoundly under Edward Grey (1862-1933) , who had become foreign secretary in 1905. [16]

As a means to contain Russian expansionism in the Far East, Britain had abandoned her previous policy of “splendid isolation” and signed an alliance treaty with Japan in January 1902 when the Second Boer War was drawing to a close. After three years of fierce fighting, the war in South Africa inspired dystopian visions of decline in Britain. To protect the empire and the United Kingdom, alliances would be useful, or even necessary. In early 1904, at a time when a Russo-Japanese war seemed imminent and threatened to draw the belligerents’ respective allies into the fray, Britain was willing to form closer diplomatic ties with France, her long-standing competitor in overseas expansion. On 8 April 1904, Foreign Secretary Lord Lansdowne (1845-1927) and the French ambassador to London signed a declaration that was meant to resolve conflicts concerning colonial interests in Morocco, Egypt , and other territories overseas. [17] This agreement would become known as the Entente Cordiale.

What initially looked like a low-level deal about more or less far-flung places marked the beginning of a major realignment among the Great Powers. Withstanding German pressure with regard to the Moroccan Question in 1905 and 1911, the Entente Cordiale proved its mettle as a tool in crisis diplomacy. It was no formal alliance and therefore neither a casus foederis nor a military commitment were part of the agreement. Nevertheless, army leaders on both sides of the Channel gave thought to coalition warfare against the Triple Alliance on the continent. In secret negotiations, they agreed on a British Expeditionary Force of 100,000 to 120,000 troops, to be deployed alongside the French army. Revealed to the British cabinet only in 1912, the military plans still did not have the same binding character as the Franco-Russian Alliance. In addition, the naval agreement between Britain and France in 1912 would provide for burden-sharing between both fleets, with the French focusing on the Mediterranean and the British being in charge of the North Sea and the Channel. [18]

Grey inherited the Entente Cordiale from his predecessor, but he would give it broader significance. This was in line with efforts to improve relations with Russia, not least to safeguard British interests in India and the Persian Gulf. In a long-term perspective, Russia seemed much more of a challenge to the British Empire than Germany, and from this point of view, it made perfect sense to foster close relations with her. [19] The Anglo-Russian Convention of 31 August 1907 dealt with spheres of influence in Persia , Afghanistan , and Tibet. [20] But the agreement opened the way for a general alignment of British and Russian interests in Asia, including the Near East, and closer relations between the signatories. The convention was the capstone of a new pattern of cooperation between France, Britain, and Russia, which was called the Triple Entente by contemporaries. As in the case of the Triple Alliance, it was not easy to foresee the coherence and effectiveness of the Triple Entente in the event of a major European war. The possibility that another revolution in Russia might overturn the balance of power could not be dismissed. From the French point of view, there was also reason to doubt Russia’s commitment to concentrate her army against Germany, not Austria-Hungary. And it was quite unclear how Britain would act in case of a European war, not only because of divisions in the cabinet, but also because of the unpredictable mood of parliament and of the British public. [21] Nevertheless, the Triple Entente was an element of European politics to be reckoned with.

Great Power Alliances on the Eve of War ↑

By 1912, both the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente had become established features of international relations. The public had become used to debating Great Power politics in Europe in this mould. The same held true for diplomats, officials, and ministers. Scrutinizing the coherence of both alliance systems was a common topic in memoranda and official correspondence, but also in letters and diaries of experts and decision-makers. Whenever a crisis arose in international relations, the current situation of alliances and possible repercussions on their future would be considered. This pattern of thought did not necessarily lead to an escalation of crises. Alliances could even restrain the assertiveness of a Great Power in a conflict scenario. Austria-Hungary’s stance in the First Moroccan Crisis and its effect on her ally Germany; Russia’s backing off in 1909 after British and French signals of disengagement; and Germany’s disapproval of the Habsburg Monarchy’s gamble in the Winter Crisis of 1912-1913 were the most important examples of alliances helping to deescalate a crisis in the last decade before 1914. The alliance between the perennial rivals on the eastern shore of the Adriatic, Austria-Hungary and Italy, made it easier to contain their competition for dominance in Albania and thereby allowed for collective – albeit inefficient - Concert-of-Europe-style intervention on the ground and in the negotiations about the country’s future. In this respect, alliances did not necessarily hasten the sequence of crises that characterized European Great Power politics from 1904 until 1914. They could even be used to frame policies of détente. [22]

But from the First Moroccan Crisis in 1904-1905 onwards, all the major conflicts that dominated the agenda of diplomats and politicians over the course of a decade were perceived as tests of the stability of alliances. The outcome of any given crisis was judged accordingly; as a sign of alliances’ coherence, of their usefulness in times of conflict, and of their credibility as a deterrent. To be sure, not being isolated and having reliable partners among the Great Powers was important for prestige. This mattered, because any gain or loss of prestige would not go unnoticed by the public at home and decision-makers abroad. But it only became such a pressing issue because the stability or instability of alliances could overturn the calculus of military capabilities so dramatically. Since the collapse of her navy and army in 1904, Russia’s efforts to regain her military power had become key to the assessment of Europe’s strategic situation. With Russia out of the picture, Germany and her allies were in a comfortable, almost inviolable, position. With Russia rebuilding her navy and army (with support from the French), German superiority was fading away. How strong Russia was in military terms at any given moment and how strong she would be in the future was a primary concern of military experts, not just in Berlin or Vienna, but also in Paris and London. Striving for security and strategic leverage, the Great Powers, Italy included, joined armaments races at sea, but more importantly on land, which gripped Europe in the final years before the July Crisis. Technological change and shifting notions of quality at the tactical level of operations added another set of “known unknowns” concerning a coming Great Power war. [23]

Under these conditions, the impact of Italy or Romania switching sides or of Britain backing out of her informal alliances on the equation of military capabilities in Europe would be enormous. So it made perfect sense to look for signs of erosion, consolidation or extension of Great Power alliances. By 1914, things had become even more complex because of the growing relevance of alliance patterns in South East Europe. Whether Romania could still be counted upon to honour her obligations under the terms of the Triple Alliance was doubtful. This question was closely intertwined with expectations with regard to Bulgaria’s stance in a major war. The answer mattered immensely, because the Balkan peninsula had once again become the hot spot of Great Power conflict. As became obvious in the Winter Crisis of 1912-1913, this put Austria-Hungary and Russia in the front row of a possible general conflagration. The balance of military power on the Balkans had become an important factor in any war scenario. Therefore, perceptions of an impending regional realignment fed into the overall assessment of changes in the strategic situation on the continent. Short of a diplomatic coup that would both attach Bulgaria to the Triple Alliance and keep Romania as an ally, Austria-Hungary’s foreign office expected the end of the Habsburg Monarchy’s status as a Great Power sooner rather than later. By the early summer of 1914, the Germans had come to similar conclusions. From this perspective, time was on the side of the Triple Entente, provided Russia continued to build up her military and was able to shield client Serbia from Austrian pressure with the assistance of France and Britain. [24]

After the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863-1914) in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914, the debates about the Habsburg Monarchy’s response among a small circle of Austria-Hungary’s leaders reflected their experience with the pitfalls of alliance politics. Unwilling to offer Italy any say in the future settlement of affairs in Serbia and distrustful of its loyalty, they tried to keep Rome in the dark about their plans and negotiations with Berlin during the early stages of the July Crisis. As it turned out, Italian sources passed German hints about impending Austrian action against Serbia on to Russia. With regard to Germany, there was no alternative to vetting Berlin’s stance in advance. Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) had, on previous occasions, forgone Germany’s right to judge on the appropriateness of Austrian policy that might trigger the casus foederis , something Bismarck had always refused to do. Nevertheless, in 1912-1913, Vienna had been left in the lurch by Germany as soon as the crisis with Russia escalated. So, in July 1914, it was essential to get German approval in advance and to make sure that it would not be withdrawn later. The German “blank cheque” was the necessary precondition for Austria-Hungary’s policy in the July Crisis. As Berlin’s efforts to keep the Triple Entente from meddling with the Austro-Serbian conflict failed and Russian military measures alerted the German general staff to a possible Great Power war, Germany’s belated attempts to ask for more flexible Austrian crisis management evoked fears of a second 1912 in Vienna. They were as telling as they proved to be unfounded.

By the end of July 1914, with Russia mobilizing her army, strategic concerns shaped the policies of Germany. After the renewal of the Triple Alliance in 1912, plans for the deployment of Italian troops along the German front against France had been made by the German and Italian general staffs, but since Italy opted for neutrality, these preparations were useless. In the context of the Dual Alliance, only very general strategic and operational concepts had been shared by the general staffs in Vienna and Berlin. The Austrian general staff had promised to launch a major offensive against Russia, while the bulk of the German army would fight against France in the early stages of war. Since 1909, this idea of burden-sharing in case of a European war had been the basis of Austrian and German war planning . When the general staffs faced Russian mobilization at the end of July 1914, they had to come to a decision: whether to follow through with plans suitable for a general war or just deter Russia from intervention in the Austro-Serbian conflict. The political situation and strategic considerations suggested that the Franco-Russian alliance would aim at a two-front war against Germany. [25] In fact, France assured the Russians of her commitment to the alliance and reminded them to do the same. The lingering sense of uncertainty about Britain’s role did not help to contain the crisis. [26] In the end, alliances didn’t restrain the drift to brinkmanship and Britain did not back away. [27] The Dual Alliance and the Triple Entente were at war.

Conclusion: 1914 - Have Alliances Failed? ↑

Alliances had been a fixture of Europe’s international system for centuries. For almost 100 years, from 1814/1815 until 1914, they were used to manage Great Power politics. Alliances could bolster cooperation among all or at least most of the Great Powers, as in the case of the Quadruple Alliance, which would form the basis of the European Pentarchy and the Concert of Europe. They could also become instruments designed to wage war, as in the case of France and Sardinia in 1858 or Prussia and Italy in 1866. After 1871, the alliances of the Great Powers provided some sense of security in an age that was still shaped by the concept of war as a legitimate political tool. The formalized, treaty-based defensive alliances and Britain’s less formal alignment with France and Russia on the basis of agreements about colonial issues gave structure to international relations, changing rapidly due to economic, social, and cultural developments. The relative decline of Britain in economic terms and the corresponding ascent of the United States , the rising fear of social unrest and even revolution, and the emergence of public debate about foreign policy in most European countries, questioned traditional notions of diplomacy and vital interests. To perceive Great Power relations in terms of alliances offered some predictability in the case of an international crisis and could offer an opportunity to contain conflicts. In the Winter Crisis of 1912-1913, when Germany reined in her ally Austria, the de-escalating potential of defensive alliances was demonstrated again. The conference in London about the future of Albania bears witness to Great Power cooperation between states in opposing alliance blocs. But as the military experts got used to including assumptions about the evolving international situation in their strategic analyses, diplomats and politicians paid increasing attention to shifts in military capabilities. Thus, reflecting on the strengths and weaknesses of alliances fostered a militarization of security policy in the cabinets of Europe.

As such, neither the Triple Alliance nor the Triple Entente were incompatible with efforts to keep the peace of Europe. What turned them into destabilizing forces in European politics was a combination of inherent problems of alliance politics and other factors. Keeping the existing alliance together became a driving motivation for the British Foreign Office and, up to a point, also for its French counterpart. The same holds true for Germany and Austria-Hungary, in particular with respect to Italy and Romania. The urgency given to defending one’s alliance’s coherence limited the scope for compromise in a crisis. In the case of the Triple Alliance, Austrian and – to a lesser degree – German fears about Rome’s and Bucharest’s reliability fostered the perception that time was on the side of the Triple Entente. This mattered immensely to the decision-makers in the major European capitals, because the sequence of crises that had begun in 1904 had taught them the ever-increasing relevance of military power in international relations. Alliances were means to increase this power. They could embolden foreign policy makers or – depending on expectations about the stability of one’s own alliance and that of one’s future adversaries – challenge international status. In this way, the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente had a negative impact on crisis management in July 1914.

Alliances failed to keep the peace in 1914 and, in combination with the militarized perception of security that had emerged among decision-makers and large parts of the public in Europe, even played a role in bringing about war. But is it correct to judge them as a complete failure in 1914? The answer depends on an assumption about the purpose of alliances in the early 20 th century. They certainly did not stop the escalation towards war in the summer of 1914. Germany did not even try to brake Austria-Hungary’s high-risk course until the very end of July 1914, whereas France and finally even Great Britain underwrote Russia’s strategy of escalation. More importantly, both alliances did not work as effective deterrents. Consequently, they failed as a means to avoid war. However, they made sure that none of the Great Powers would have to face isolation. Although the Triple Alliance fell apart in the summer of 1914, as Italy decided to stay neutral, Berlin and Vienna were able to fall back on their treaty of 1879 as a foundation on which to build a wartime coalition. Due to Britain’s decision to declare the infringement of Belgium’s territorial integrity a casus belli , the Triple Entente effectively became a reliable alliance. Since the Great War would be shaped by coalitions, making it perniciously hard to overcome adversaries who were able to use a pool of combined resources in order to counter setbacks, the alliances would provide the belligerent powers of 1914 with the most crucial asset of all: partners in coalition warfare. The pre-war alliances did not help to extend Europe’s long peace, but they made it easier to fight a long war.

Günther Kronenbitter, Universität Augsburg

Section Editors: Annika Mombauer ; William Mulligan

- ↑ Schroeder, Paul W.: Systems, Stability, and Statecraft. Essays on the International History of Modern Europe, New York et al. 2004, pp. 37-57, 195-199, 223-241.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 199-208; Bridge, Francis Roy / Bullen, Richard: The Great Powers and the European State System, 1814-1914, Harlow et al. 2005, pp. 1-174.

- ↑ Canis, Konrad: Bismarcks Außenpolitik 1870-1890. Aufstieg und Gefährdung, Paderborn et al. 2004, pp. 39-140.

- ↑ Dual Alliance with Austria (October 7, 1879), issued by German History in Documents and Images (GHDI), online: http://ghdi.ghi-dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=1856 (retrieved: 25 June 2019).

- ↑ Canis, Bismarcks Außenpolitik 2004, pp. 141-159; Baumgart, Winfried: Europäisches Konzert und nationale Bewegung 1830-1878, Paderborn et al. 2007, pp. 416-428; Canis, Konrad: Der Zweibund in der Bismarckschen Außenpolitik, in: Rumpler, Helmut / Niederkorn, Jan Paul (eds.): Der “Zweibund” 1879. Das deutsch-österreichisch-ungarische Bündnis und die europäische Diplomatie, Vienna 1996, pp. 41-67.

- ↑ Angelow, Jürgen: Kalkül und Prestige. Der Zweibund am Vorabend des Ersten Weltkrieges, Cologne et al. 2000. For the intellectual and cultural underpinnings of the Dual Alliance and their wartime effects, see Vermeiren, Jan: The First World War and German National Identity, Cambridge et al. 2016.

- ↑ Triple Alliance with Austria and Italy (May 20, 1882), issued by German History in Documents and Images (GHDI), online: http://ghdi.ghi-dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=1860 (retrieved: 26 June 2019).

- ↑ Austro-Hungarian / Rumanian Accord, issued by The World War I Document Archive, online: https://wwi.lib.byu.edu/index.php/Austro-Hungarian_/_Rumanian_Accord (retrieved: 26 June 2019).

- ↑ Expanded version of 1912 (In English), issued by The World War I Document Archive, online: https://wwi.lib.byu.edu/index.php/Expanded_version_of_1912_(In_English) (retrieved: 26 June 2019).

- ↑ Afflerbach, Holger: Der Dreibund. Europäische Großmacht- und Allianzpolitik vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Vienna et al. 2002.

- ↑ Afflerbach, Holger: Der Dreibund als Instrument der europäischen Friedenssicherung vor 1914, in: Rumpler / Niederkorn, Der “Zweibund” 1996, pp. 87-118.

- ↑ Canis, Konrad: Der Weg in den Abgrund. Deutsche Außenpolitik 1902-1914, Paderborn et al. 2011, pp. 611-655.

- ↑ Secret Reinsurance Treaty with Russia (June 18, 1887), issued by German History in Documents and Images (GHDI), online: http://ghdi.ghi-dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=1862 (retrieved: 26 June 2019).

- ↑ The Franco-Russian Alliance Military Convention. August 18, 1892, issued by Lillian Goldman Law Library, online: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/frrumil.asp (retrieved: 26 June 2019).

- ↑ Kennan, George F.: The Fateful Alliance. France, Russia, and the Coming of the First World War, New York et al. 1984; Snyder, Glenn H.: Alliance Politics, Ithaca et al. 1997, pp. 109-124, 261-296.

- ↑ Rose, Andreas: Between Empire and Continent. British Foreign Policy before the First World War, New York et al. 2017, pp. 273-305.

- ↑ The Franco British Declaration, 1904, issued by Lillian Goldman Law Library, online: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/entecord.asp (retrieved: 26 June 2019).

- ↑ Williamson, Samuel R., Jr.: The Politics of Grand Strategy. Britain and France Prepare for War, 1904-1914, Cambridge, MA 1969.

- ↑ Neilson, Keith: Britain and the Last Tsar. British Policy and Russia, 1894-1917, Oxford 1995.

- ↑ The Anglo-Russian Entente. 1907, issued by Lillian Goldman Law Library, online: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/angrusen.asp (retrieved: 26 June 2019).

- ↑ Lieven, Dominic: Towards the Flame. Empire, War and the End of Tsarist Rusia, London 2015, pp. 182-224; Schmidt, Stefan: Frankreichs Außenpolitik in der Julikrise 1914. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Ausbruchs des ersten Weltkrieges, Munich 2009, pp. 246-288.

- ↑ Kießling, Frieder: Gegen den “großen Krieg”? Entspannung in den internationalen Beziehungen 1911-1914, Munich 2002; Otte, T. G.: Détente 1914. Sir William Tyrrell’s Secret Mission to Germany, in: The Historical Journal 56/1 (2013), pp. 175-204.

- ↑ Stevenson, David: Armaments and the Coming of War. Europe, 1904-1914, Oxford et al. 1996; Mulligan, William: The Origins of the First World War, Cambridge et al. 2010, pp. 49-91.

- ↑ Soutou, Georges-Henri: La Grande Illusion. Quand la France perdait la paix 1914-1920, Paris 2015, pp. 15-42.

- ↑ Kronenbitter, Günther: “Krieg im Frieden”. Die Führung der k.u.k. Armee und die Großmachtpolitik Österreich-Ungarns 1906-1914, Munich 2003, pp. 369-519.

- ↑ Clark, Christopher: The Sleepwalkers. How Europe Went to War in 1914, London et al. 2012, pp. 242-358; Otte, T. G.: Entente diplomacy v. détente, 1911-1914, in: Geppert, Dominik / Mulligan, William / Rose, Andreas (eds.): The Wars Before the Great War, Cambridge et al. 2015, pp. 264-282.

- ↑ Otte, T. G.: July Crisis: The World’s Descent into War. Summer 1914, Cambridge 2014.

- Afflerbach, Holger: Der Dreibund. Europäische Grossmacht- und Allianzpolitik vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg , Vienna 2002: Böhlau.

- Angelow, Jürgen: Kalkül und Prestige. Der Zweibund am Vorabend des Ersten Weltkrieges , Cologne et al. 2000: Böhlau.

- Bridge, Francis Roy / Bullen, Roger J.: The great powers and the European states system 1814-1914 , Harlow 2005: Pearson Longman.

- Geppert, Dominik / Mulligan, William / Rose, Andreas (eds.): The wars before the Great War. Conflict and international politics before the outbreak of the First World War , Cambridge et al. 2015: Cambridge University Press.

- Kennan, George F.: The fateful alliance. France, Russia, and the coming of the First World War , Manchester 1984: Manchester University Press.

- Mulligan, William: The origins of the First World War , Cambridge 2010: Cambridge University Press.

- Rose, Andreas: Between empire and continent. British foreign policy before the First World War , New York 2017: Berghahn Books.

- Rumpler, Helmut / Niederkorn, Jan Paul (eds.): Der 'Zweibund' 1879. Das deutsch-österreichisch-ungarische Bündnis und die europäische Diplomatie , Vienna 1996: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Schroeder, Paul W., Wetzel, David / Jervis, Robert / Levy, Jack S. (eds.): Systems, stability, and statecraft. Essays on the international history of modern Europe , New York 2004: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Snyder, Glenn H.: Alliance politics , Ithaca 1997: Cornell University Press.

- Stevenson, David: Armaments and the coming of war. Europe, 1904-1914 , Oxford; New York 1996: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press.

- Williamson, Jr., Samuel R.: The politics of grand strategy. Britain and France prepare for war, 1904-1914 , Cambridge 1969: Harvard University Press.

Kronenbitter, Günther: Alliance System 1914 , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2019-08-15. DOI : 10.15463/ie1418.11398 .

This text is licensed under: CC by-NC-ND 3.0 Germany - Attribution, Non-commercial, No Derivative Works.

Related Articles

External links.

The Major Alliances of World War I

The pacts resulted from the countries' hope for a balance of power

ThoughtCo./Emily Roberts

- World War I

- Battles & Wars

- Key Figures

- Arms & Weapons

- Naval Battles & Warships

- Aerial Battles & Aircraft

- French Revolution

- Vietnam War

- World War II

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- M.A., Medieval Studies, Sheffield University

- B.A., Medieval Studies, Sheffield University

By 1914, Europe's six major powers were split into two alliances that would form the warring sides in World War I . Britain, France, and Russia formed the Triple Entente, while Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy joined in the Triple Alliance. These alliances weren't the sole cause of World War I, as some historians have contended, but they did play an important role in hastening Europe's rush to conflict.

The Central Powers

Following a series of military victories from 1862 to 1871, Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck formed a German state out of several small principalities. After unification, Bismarck feared that neighboring nations, particularly France and Austria-Hungary, might act to destroy Germany. Bismarck wanted a careful series of alliances and foreign policy decisions that would stabilize the balance of power in Europe. Without them, he believed, another continental war was inevitable.

The Dual Alliance

Bismarck knew an alliance with France wasn’t possible because of lingering French anger over Alsace-Lorraine, a province Germany had seized in 1871 after defeating France in the Franco-Prussian War. Britain, meanwhile, was pursuing a policy of disengagement and was reluctant to form any European alliances.

Bismarck turned to Austria-Hungary and Russia. In 1873, the Three Emperors League was created, pledging mutual wartime support among Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia. Russia withdrew in 1878, and Germany and Austria-Hungary formed the Dual Alliance in 1879. The Dual Alliance promised that the parties would aid each other if Russia attacked them or if Russia assisted another power at war with either nation.

The Triple Alliance

In 1882, Germany and Austria-Hungary strengthened their bond by forming the Triple Alliance with Italy. All three nations pledged support should any of them be attacked by France. If any member found itself at war with two or more nations at once, the alliance would come to their aid. Italy, the weakest of the three, insisted on a final clause, voiding the deal if the Triple Alliance members were the aggressor. Shortly after, Italy signed a deal with France, pledging support if Germany attacked them.

Russian 'Reinsurance'

Bismarck was keen to avoid fighting a war on two fronts, which meant making some form of agreement with either France or Russia. Given the sour relations with France, Bismarck signed what he called a "reinsurance treaty" with Russia, stating that both nations would remain neutral if one was involved in a war with a third party. If that war was with France, Russia had no obligation to aid Germany. However, this treaty lasted only until 1890, when it was allowed to lapse by the government that replaced Bismarck. The Russians had wanted to keep it. This is usually seen as a major error by Bismarck's successors.

After Bismarck

Once Bismarck was voted out of power, his carefully crafted foreign policy began to crumble. Eager to expand his nation's empire, Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm II pursued an aggressive policy of militarization. Alarmed by Germany's naval buildup, Britain, Russia, and France strengthened their own ties. Meanwhile, Germany's new elected leaders proved incompetent at maintaining Bismarck's alliances, and the nation soon found itself surrounded by hostile powers.

Russia entered into an agreement with France in 1892, spelled out in the Franco-Russian Military Convention. The terms were loose but tied both nations to supporting each other should they be involved in a war. It was designed to counter the Triple Alliance. Much of the diplomacy Bismarck had considered critical to Germany's survival had been undone in a few years, and the nation once again faced threats on two fronts.

The Triple Entente

Concerned about the threat rival powers posed to the colonies, Great Britain began searching for alliances of its own. Although Britain had not supported France in the Franco-Prussian War, the two nations pledged military support for one another in the Entente Cordiale of 1904. Three years later, Britain signed a similar agreement with Russia. In 1912, the Anglo-French Naval Convention tied Britain and France even more closely militarily.

When Austria's Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife were assassinated in 1914 , the great powers of Europe reacted in a way that led to full-scale war within weeks. The Triple Entente fought the Triple Alliance, although Italy soon switched sides. The war that all parties thought would be finished by Christmas 1914 instead dragged on for four long years, eventually bringing the United States into the conflict. By the time the Treaty of Versailles was signed in 1919, officially ending the Great War, more than 8.5 million soldiers and 7 million civilians were dead.

DeBruyn, Nese F. " American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics ." Congressional Research Service Report RL32492. Updated 24 Sept. 2019.

Epps, Valerie. " Civilian Casualties in Modern Warfare: The Death of the Collateral Damage Rule ." Georgia Journal of International and Comparative Law vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 309-55, 8 Aug. 2013.

- Causes of World War I and the Rise of Germany

- World War 1: A Short Timeline Pre-1914

- The Causes and War Aims of World War One

- Causes of World War II

- The Fourteen Points of Woodrow Wilson's Plan for Peace

- The Consequences of World War I

- World War I's Mitteleuropa

- World War I Timeline: 1914, The War Begins

- The Diplomatic Revolution of 1756

- World War I: Opening Campaigns

- The Seven Years War 1756 - 63

- World War II: Munich Agreement

- America and World War II

- The Countries Involved in World War I

- Biography of Otto Von Bismarck, Iron Chancellor Who Unified Germany

- Origins of the Cold War in Europe

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

- 20th Century

The 4 M-A-I-N Causes of World War One

Alex Browne

28 sep 2021.

It’s possibly the single most pondered question in history – what caused World War One? It wasn’t, like in World War Two, a case of a single belligerent pushing others to take a military stand. It didn’t have the moral vindication of resisting a tyrant.

Rather, a delicate but toxic balance of structural forces created a dry tinder that was lit by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo . That event precipitated the July Crisis, which saw the major European powers hurtle toward open conflict.

The M-A-I-N acronym – militarism, alliances, imperialism and nationalism – is often used to analyse the war, and each of these reasons are cited to be the 4 main causes of World War One. It’s simplistic but provides a useful framework.

The late nineteenth century was an era of military competition, particularly between the major European powers. The policy of building a stronger military was judged relative to neighbours, creating a culture of paranoia that heightened the search for alliances. It was fed by the cultural belief that war is good for nations.

Germany in particular looked to expand its navy. However, the ‘naval race’ was never a real contest – the British always s maintained naval superiority. But the British obsession with naval dominance was strong. Government rhetoric exaggerated military expansionism. A simple naivety in the potential scale and bloodshed of a European war prevented several governments from checking their aggression.

A web of alliances developed in Europe between 1870 and 1914 , effectively creating two camps bound by commitments to maintain sovereignty or intervene militarily – the Triple Entente and the Triple Alliance.

- The Triple Alliance of 1882 linked Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy.

- The Triple Entente of 1907 linked France, Britain and Russia.

A historic point of conflict between Austria Hungary and Russia was over their incompatible Balkan interests, and France had a deep suspicion of Germany rooted in their defeat in the 1870 war.

The alliance system primarily came about because after 1870 Germany, under Bismarck, set a precedent by playing its neighbours’ imperial endeavours off one another, in order to maintain a balance of power within Europe

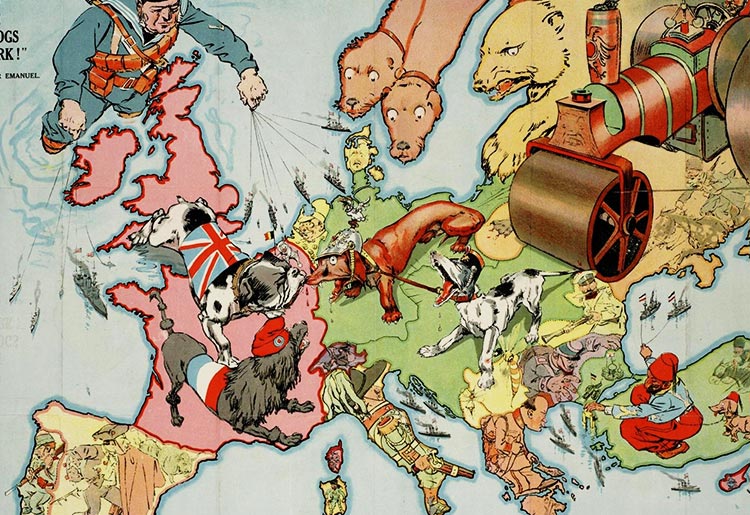

‘Hark! hark! the dogs do bark!’, satirical map of Europe. 1914

Image Credit: Paul K, CC BY 2.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Imperialism

Imperial competition also pushed the countries towards adopting alliances. Colonies were units of exchange that could be bargained without significantly affecting the metro-pole. They also brought nations who would otherwise not interact into conflict and agreement. For example, the Russo-Japanese War (1905) over aspirations in China, helped bring the Triple Entente into being.

It has been suggested that Germany was motivated by imperial ambitions to invade Belgium and France. Certainly the expansion of the British and French empires, fired by the rise of industrialism and the pursuit of new markets, caused some resentment in Germany, and the pursuit of a short, aborted imperial policy in the late nineteenth century.

However the suggestion that Germany wanted to create a European empire in 1914 is not supported by the pre-war rhetoric and strategy.

Nationalism

Nationalism was also a new and powerful source of tension in Europe. It was tied to militarism, and clashed with the interests of the imperial powers in Europe. Nationalism created new areas of interest over which nations could compete.

For example, The Habsburg empire was tottering agglomeration of 11 different nationalities, with large slavic populations in Galicia and the Balkans whose nationalist aspirations ran counter to imperial cohesion. Nationalism in the Balkan’s also piqued Russia’s historic interest in the region.

Indeed, Serbian nationalism created the trigger cause of the conflict – the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

The spark: the assassination

Ferdinand and his wife were murdered in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip, a member of the Bosnian Serbian nationalist terrorist organization the ‘Black Hand Gang.’ Ferdinand’s death, which was interpreted as a product of official Serbian policy, created the July Crisis – a month of diplomatic and governmental miscalculations that saw a domino effect of war declarations initiated.

The historical dialogue on this issue is vast and distorted by substantial biases. Vague and undefined schemes of reckless expansion were imputed to the German leadership in the immediate aftermath of the war with the ‘war-guilt’ clause. The notion that Germany was bursting with newfound strength, proud of her abilities and eager to showcase them, was overplayed.

The first page of the edition of the ‘Domenica del Corriere’, an Italian paper, with a drawing by Achille Beltrame depicting Gavrilo Princip killing Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in Sarajevo

Image Credit: Achille Beltrame, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The almost laughable rationalization of British imperial power as ‘necessary’ or ‘civilizing’ didn’t translate to German imperialism, which was ‘aggressive’ and ‘expansionist.’ There is an on-going historical discussion on who if anyone was most culpable.

Blame has been directed at every single combatant at one point or another, and some have said that all the major governments considered a golden opportunity for increasing popularity at home.

The Schlieffen plan could be blamed for bringing Britain into the war, the scale of the war could be blamed on Russia as the first big country to mobilise, inherent rivalries between imperialism and capitalism could be blamed for polarising the combatants. AJP Taylor’s ‘timetable theory’ emphasises the delicate, highly complex plans involved in mobilization which prompted ostensibly aggressive military preparations.

Every point has some merit, but in the end what proved most devastating was the combination of an alliance network with the widespread, misguided belief that war is good for nations, and that the best way to fight a modern war was to attack. That the war was inevitable is questionable, but certainly the notion of glorious war, of war as a good for nation-building, was strong pre-1914. By the end of the war, it was dead.

You May Also Like

The Peasants’ Revolt: Rise of the Rebels

10 Myths About Winston Churchill

Medusa: What Was a Gorgon?

10 Facts About the Battle of Shrewsbury

5 of Our Top Podcasts About the Norman Conquest of 1066

How Did 3 People Seemingly Escape From Alcatraz?

5 of Our Top Documentaries About the Norman Conquest of 1066

1848: The Year of Revolutions

What Prompted the Boston Tea Party?

15 Quotes by Nelson Mandela

The History of Advent

The Princes in the Tower: Solving History’s Greatest Cold Case

- Modern History

The four MAIN causes of World War I explained

The First World War was the first conflict that occurred on a staggering scale. World War I (WWI) was unprecedented in its global impact and the extent of its industrialization.

However, the reason why the war originally began is incredibly complex. To try and explain the causes of the war, historians have tried to simplify it down to four main causes.

They create the acronym: MAIN.

Imperialism

Nationalism.

This simplified acronym is a useful way to remember the four MAIN causes of the war.

However, we will explain each of these concepts out of order below.

One of the most commonly discussed causes of WWI was the system of alliances that existed by 1914, the year the war started.

An 'alliance' is an agreement made between two countries, where each side promises to help the other if required.

Most of the time, this involves military or financial assistance. When an alliance is created, the countries involved are known as 'allies'.

By the dawn of the First World War, most European countries had entered into one or more alliances with other countries.

What made this an important cause of WWI, was that many of these alliances were military in nature: that if one country attacked or was attacked, all of their allies had promised to get involved as well.

This meant, that if just one country attacked another, most of Europe would immediately be at war, as each country jumped in to help out their friends.

Imperialism, as a concept, has been around for a very long time in human history. Imperialism is the desire to build an empire for your country.

This usually involves invading and taking land owned by someone else and adding it to your empire.

By the 19th century, many European countries had been involved in imperialism by conquering less advanced nations in Asia, the Americas or Africa.

By 1900, the British Empire was the largest imperial power in the world. It controlled parts of five different continents and owned about a quarter of all land in the world.

France was also a large empire, with control over parts of south-east Asia and Africa.

By 1910, Germany had been trying to build its own empire to rival that of Britain and France and was interested in expanding its colonial holdings.

This meant that when an opportunity for a war of conquest became available, Germany was very keen to take advantage of it.

Militarism is the belief that a country's army and navy (since air forces didn't exist at the start of WWI) were the primary means that nations resolved disagreement between each other.

As a result, countries like to boast about the power of their armed forces.

Some countries spent money improving their land armies, while others spent money on their navies.

Some countries tried to gain the advantage by having the most number of men in their armies, while others focused more on having the most advanced technology in their forces.

Regardless of how they approached it, countries used militarism as a way of gaining an edge on their opponents.

An example of this competition for a military edge can be seen in the race between Britain and Germany to have the most powerful navy.

Britain had recently developed a special ship known as a 'dreadnought’. The Germans were so impressed by this, that they increased their government spending so that they also had some dreadnoughts.

The final of the four causes is 'nationalism'. Nationalism is the idea that people should have a deep love for their country, even to the extent that they are willing to die for it.

Throughout the 19th century, most countries had developed their own form of nationalism, where they encouraged a love of the nation in their citizens through the process of creating national flags and writing national anthems.

Children at schools were taught that their country was the best in the world and that should it ever be threatened, that they should be willing to take up arms to defend it.

The growing nationalist movements created strong animosity between countries that had a history of armed conflict.

A good example of this is the deep anger that existed between Germany and France.

These two countries had a recent history of war and struggling over a small region between the two, called Alsace-Lorraine.

Germany had seized control of it after the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, which the French were deeply upset by.

As a result, France believed that they should be willing to fight and die to take it back.

Conflicts and Crises

In the two decades before WWI started in 1914, there were a number of smaller conflicts and crises that had already threatened to turn into global conflicts.

While these didn't eventually start the global war, it does show the four causes mentioned above and how they interacted in the real world.

The Moroccan Crisis

In 1904, Britain recognized France's sphere of influence over Morocco in North Africa in exchange for France recognizing Britain's sphere of influence in Egypt.

However, the Moroccans had a growing sense of nationalism and wanted their independence.

In 1905, Germany announced that they would support Morocco if they wanted to fight for their freedom.

To avoid war, a conference was held which allowed France to keep Morocco. Then, in 1911, the Germans again argued for Morocco to fight against France.

To again avoid war. Germany received territorial compensation in the French Congo in exchange for recognizing French control over Morocco.

The Bosnian Crisis

In 1908, the nation of Austria-Hungary had been administrating the Turkish regions of Bosnia and Herzegovina since 1878, but they formally annexed it in 1908, which caused the crisis.

The country of Serbia was outraged, because they felt that it should have been given to them. As a result, Serbia threatened to attack Austria-Hungary.

To support them, Russia, who was allied to Serbia, prepared its armed forces. Germany, however, who was allied to Austria-Hungary, also prepared its army and threaten to attack Russia.

Luckily, war was avoided because Russia backed down. However, there was some regional fighting during 1911 and 1912, as Turkey lost control of the region.

Despite this, Serbia and Austria-Hungary were still angry with each other as they both wanted to expand into these newly liberated countries.

Further reading

What do you need help with, download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

World History Project AP®

Course: world history project ap® > unit 7, read: what caused the first world war.

- BEFORE YOU WATCH: How World War I Started – Crash Course World History #209

- WATCH: How World War I Started

- READ: The First World War as a Global War

- BEFORE YOU WATCH: Britain and World War I

- WATCH: Britain and World War I

- BEFORE YOU WATCH: Southeast Asia and World War I

- WATCH: Southeast Asia and World War I

- BEFORE YOU WATCH: The Middle East and World War I

- WATCH: The Middle East and World War I

First read: preview and skimming for gist

Second read: key ideas and understanding content.

- Who killed Franz Ferdinand? Why did they kill him?

- How did the European alliance system help start the war?

- How did imperialism help start the war?

- Why does the author argue that industrialization made the war inevitable once preparations were started?

- How might the First World War have happened on accident?

Third read: evaluating and corroborating

- To what extent does this article explain the causes and consequences of World War I?

- This article gives three broad explanations for the origins of the First World War. Which view, or argument, do you agree with the most, and why? Why not the others?

What Caused the First World War?

World war why, one shot: the assassination of archduke franz ferdinand, deeper trends: help me help you help me, accidental war: missed the memo, hit the target.

- Yes, these terms can get confusing. Nationalism was introduced to you as the idea that a state should govern itself, and not have some empire as its boss. But at some point, that feeling that you should get to govern yourself can turn into the idea that you are better than other nations, and becomes a kind of extreme patriotism. We call that nationalism as well. As we will see, nationalism is a pretty flexible thing, and it can be used for lots of different purposes.

- Top map by Joe Mabel, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_the_German_Empire_-_1914.PNG

- Bottom map by Andrew0921, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:British_Empire_in_1914.png

Want to join the conversation?

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Alliances are possibly the best known cause of World War I. An alliance is a formal political, military or economic agreement between two or more nations. Military alliances usually contain promises that in the event of war or aggression, one signatory nation will support the others. The terms of this support is outlined in the alliance ...

Alliance System 1914. Alliances were an important feature of the international system on the eve of World War I. The formation of rival blocs of Great Powers has previously considered a major cause of the outbreak of war in 1914, but this assessment misses the point. Instead of increased rigidity, it was, rather, the uncertainty of the ...

ThoughtCo./Emily Roberts. By. Robert Wilde. Updated on January 28, 2020. By 1914, Europe's six major powers were split into two alliances that would form the warring sides in World War I. Britain, France, and Russia formed the Triple Entente, while Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy joined in the Triple Alliance.

9. Tanks are one of the most significant weapons to emerge from World War I. Investigate and discuss the development, early use and effectiveness of tanks in the war. 10. The Hague Convention outlined the ‘rules of war’ that were in place during World War I. Referring to specific examples, discuss where and how these ‘rules of war’ were ...

World War I, an international conflict that in 1914–18 embroiled most of the nations of Europe along with Russia, the United States, the Middle East, and other regions. The war pitted the Central Powers —mainly Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey —against the Allies—mainly France, Great Britain, Russia, Italy, Japan, and, from 1917 ...

However, when Germany executed the Schlieffen Plan on August 3rd 1914 and crossed the Belgian border, Britain decided to act upon the violation of Belgium’s neutrality. This map of Europe clearly shows the surrounding of the Central Powers by the Allies. Timeline. 20th Century, World War One.

Alliances. A web of alliances developed in Europe between 1870 and 1914, effectively creating two camps bound by commitments to maintain sovereignty or intervene militarily – the Triple Entente and the Triple Alliance. The Triple Alliance of 1882 linked Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy. The Triple Entente of 1907 linked France, Britain and ...

Causes. Over the course of the 19th century, rival powers of Europe formed alliances. Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy formed the Triple Alliance. Great Britain, France, and Russia formed the Triple Entente. Political instability and competition threatened those alliances. (Italy, for example, eventually entered World War I in opposition to ...

Alliances. One of the most commonly discussed causes of WWI was the system of alliances that existed by 1914, the year the war started. An 'alliance' is an agreement made between two countries, where each side promises to help the other if required. Most of the time, this involves military or financial assistance.

The other was the Triple Alliance, which included Austro-Hungary, Germany and Italy, and later the Ottoman Empire, eventually becoming known as the Central Powers. These opposing alliances pretty much guaranteed that if Russia and Austro-Hungary went to war, they could drag in their allies, making the conflict much larger than the two enemies ...