The Digital Divide Essay: the Challenge of Technology and Equity – Essay Example

Introduction, what is the digital divide, causes of the digital divide, reducing the divide, digital divide: essay conclusion, works cited.

The invention of the computer and the subsequent birth of the internet have been seen as the most significant advances of the 20th century.

Over the course of the past few decades, there has been a remarkable rise in the use of computers and the internet. Sahay asserts that the ability of computing technologies to traverse geographical and social barriers has resulted in the creation of a closer knit global community (36). In addition to this, the unprecedented high adoption rate of the internet has resulted in it being a necessity in the running of our day to day lives.

However, there have been concerns due to the fact that these life transforming technologies are disparately available to people in the society. People in the high-income bracket have been seen to have a higher access to computer and the internet. This paper argues that the digital divide does exist and sets out to provide a better understanding of the causes of the same. Solutions to this problem are also addressed by this paper.

The term divide is mostly used to refer to the economic gap that exists between the poor and richer members of the society. In relation to technology, the OECD defines digital divide as ” the gap between individuals, households, businesses and geographic areas at different socio-economic levels with regard both to their opportunities to access information and communication technologies (ICTs) and to their use of the Internet for a wide variety of activities.” (5). As such, the digital divide refers to the disparities in access of communication technology experienced by people.

While the respective costs of computers and internet access have reduced drastically over the years, these costs still remain significantly expensive for some people in the population. As a result of this, household income is still a large determinant of whether internet access is available at a home.

Income is especially a large factor in developing countries where most people still find the cost of owning a PC prohibitive. However, income as a factor leading to the digital divide is not only confined to developing nations. A report by the NTIA indicated that across the United States, internet access in homes continued to be closely correlated with the income levels (3).

Education also plays a key role in the digital divide. The National Telecommunications and Information Administration indicates that in America, certain groups such as Whites and Asian Americans who possess higher educational levels have higher levels of both computer ownership as well as access to the internet (3). This is because the more educated members of the society are having a higher rate of increased access to computers and internet access as opposed to the less educated.

A simple increase in the access to computer hardware resources through the production of low cost versions of information technology which is affordable to many does not necessarily result in a reduction in the digital divide. This is because in addition to the economic realities there are other prominent factors.

The lack of technological knowhow has been cited as further widening the digital divide. This means that even with access to technology, people might still be unable to make effective usage of the same. Sahay best expresses this problem by asserting that “just by providing people with computers and internet access, we cannot hope to devise a solution to bridge the digital divide.” (37).

Another cause of the digital divide is the social and cultural differences evident in most nations in the world. One’s race and culture have been known to have a deep effect on their adoption and use of a particular technology (Chen and Wellman 42).

This is an opinion which is shared by Sahay who notes that people with fears, assumptions or pre-conceived notions about technology may shy away from its usage (46). As such, people can have the economic means and access to computers and the internet but their culture may retard their use of the same.

The digital divide leads to a loss of the opportunity by many people to benefit from the tremendous economic and educational opportunities that the digital economy provides (NTIA 3). As such, the reduction of this divide by use of digital inclusion steps is necessary for everyone to share in the opportunities provided. As has been demonstrated above, one of the primary causes of the digital divide is the income inequality between people and nations.

Most developing countries have low income levels and their population cannot afford computers. To help alleviate this, programs have been put in place to reduce the cost of computers or even offer them for free to the developing countries. For example, a project by Quanta Computer Inc in 2007 set out to supply laptops to developing world children by having consumers in the U.S. buy 2 laptops and have one donated to Africa (Associated Press).

Studies indicate that males are more likely than females in the comparable population to have internet access at home mostly since women dismiss private computer and internet usage (Korupp and Szydlik 417). The bridging of this gender divide will therefore lead to a reduction in the digital divide that exists.

In recent years, there has been evidence that the gender divide is slowly closing up. This is mostly as a result of the younger generation who use the computer and internet indiscriminately therefore reducing the strong gender bias that once existed. This trend should be encouraged so as to further accelerate the bridging of the digital divide.

As has been illustrated in this paper, there exist non economic factors that may lead to people not making use of computers hence increasing the digital divide. These factors have mostly been dismissed as more attention is placed on the income related divide. However, dealing with this social and cultural related divides will also lead to a decrease in the divide. By alleviating the fears and false notions that people may have about technology, people will be more willing to use computers and the internet.

A divide, be it digital or economic acts as a major roadblock in the way for economic and social prosperity. This paper set out to investigate the digital divide phenomena. To this end, the paper has articulated the issue of digital divide, its causes and solutions to the problem.

While some people do suggest that the digital divide will get bridged on its own as time progresses, I believe that governments should take up affirmative action and fund projects that will result in a digitally inclusive society. Bridging of the digital divide will lead to people and nations increasingly being included in knowledge based societies and economies. This will have a positive impact to every community in the entire world.

Associated Press. Hundred-Dollar Laptop’ on Sale in Two-for-One Deal. 2007. Web.

Chen, Wenhong and Wellman, Barry. The Global Digital Divide- Within and Between Countries . IT & SOCIETY, VOLUME 1, ISSUE 7. 2004, PP. 39-45.

Korupp, Sylvia and Szydlik, Marc. Causes and Trends of the Digital Divide. European Sociological Review Vol. 21. no. 4, 2005.

National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA). Falling Through the Net: Towards Digital Inclusion . 2000. Web.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Understanding the Digital Divide . 2001. Web.

Sahay, Rishika. The causes and Trends of the Digital Divide . 2005. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 30). The Digital Divide Essay: the Challenge of Technology and Equity - Essay Example. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-digital-divide/

"The Digital Divide Essay: the Challenge of Technology and Equity - Essay Example." IvyPanda , 30 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/the-digital-divide/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'The Digital Divide Essay: the Challenge of Technology and Equity - Essay Example'. 30 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "The Digital Divide Essay: the Challenge of Technology and Equity - Essay Example." October 30, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-digital-divide/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Digital Divide Essay: the Challenge of Technology and Equity - Essay Example." October 30, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-digital-divide/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Digital Divide Essay: the Challenge of Technology and Equity - Essay Example." October 30, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-digital-divide/.

- Operating the Process: Process Capability

- Bridging Institution in Sociopolitical Environment

- The Concept of Generation Gap Bridging in the Workplace

- Housing Policy and Bridging the Inequality Gap

- Bridging the Line Between a Human Right and a Worker’s Choice

- Bridging Cultures: Colorado Street Bridge

- The Digital Divide Challenges

- Bridging the Gap in Meeting Customer Expectations

- Artificial Intelligence: Bridging the Gap to Human-Level Intelligence

- Bridging Uncertainty in Management Consulting

- Excess Use of Technology and Motor Development

- People Have Become Overly Dependent on Technology

- Technology and Negative Effects

- The Concept and Effects of Evolution of Electronic Health Record System Software

- Americans and Digital Knowledge

How to build a bridge across the digital divide

Closing the gap. Image: REUTERS/Regis Duvignau

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Joe Myers

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved .chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, davos agenda.

- The latest Agenda Dialogues looked at the issue of the digital divide.

- Panelists explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the role of the private sector and the opportunities for closing the gap.

- Here are some of the key quotes from the session.

The World Economic Forum's latest Agenda Dialogues looked at the challenge of closing the digital divide and ensuring equitable access to the opportunities that internet connectivity affords.

Taking part were: Paula Ingabire , Minister of Information and communications technology and Innovation of Rwanda; Omar bin Sultan Al Olama , Minister of State for Artificial Intelligence, Digital Economy and Remote Work Application of the United Arab Emirates; Achim Steiner , Administrator, United Nations Development Programme; Tan Hooi Ling , Co-Founder, Grab; Robert F. Smith , Founder, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Vista Equity Partners; Adrian Lovett , President and Chief Executive Officer, World Wide Web Foundation.

The session was chaired by Børge Brende , President, World Economic Forum, and moderated by Adrian Monck , Managing Director, World Economic Forum.

Have you read?

Agenda dialogues: bridging the digital divide, take the 1 billion lives challenge to close the digital divide, bridging the digital divide to create the jobs of the future, covid-19 a 'catalyst' for digital transition.

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the digital transition, all the panelists agreed. As Paula Ingabire explained, it's been a 'catalyst' for digital transformation in many countries - both in fighting the pandemic and using digital tools to ensure essential services could continue.

But a digital divide and disparities persist, she added, and the current pace of digital adoption is exaggerating this divide.

And while technology helped tackle many of the challenges thrown up by the pandemic, there are broader issues still to tackle, explained Omar bin Sultan Al Olama. It's not enough to just give a child a tablet - you need to ensure their learning environment is appropriate, he said.

Access, in spite of the acceleration we've seen during the pandemic, remains a major hurdle though, the panel agreed.

A whole-society approach

Inclusion needs to be at the centre of the digital transformation, urged Achim Steiner. You need to consider society as a whole, he said. You need to build digital ecosystems that work for start-ups, for entrepreneurs, for coders and programmers, but also ensure people aren't left behind.

Connection alone isn't enough. Steiner asks: How can we build education systems that will allow young people to thrive in digital economies?

And meaningful connections are important, urged Ingabire and Adrian Lovett. It's not binary said Lovett - whether you're connected or not - it's about ensuring people have infrastructure they can rely on and a connection they can access regularly.

COVID-19 has exposed digital inequities globally and exacerbated the digital divide. Most of the world lives in areas covered by a mobile broadband network, yet more than one-third (2.9 billion people) are still offline. Cost, not coverage, is the barrier to connectivity.

At The Davos Agenda 2021 , the World Economic Forum launched the EDISON Alliance , the first cross-sector alliance to accelerate digital inclusion and connect critical sectors of the economy.

Through the 1 Billion Lives Challenge , the EDISON Alliance aims to improve 1 billion lives globally through affordable and accessible digital solutions across healthcare, financial services and education by 2025.

Read more about the EDISON Alliance’s work in our Impact Story.

The potential of closing the gap

There are enormous opportunities if we can close the divide, from education to employment. There's 'massive economic impact' in uplifting communities, if we can take advantage, summarized Robert F. Smith.

And as Lovett explained, the returns on investment are significant - we just need the resources.

Digital technology also helped those who suffered the disruption caused by the pandemic, said Tan Hooi Ling . Her technology company Grab was able to offer a lifeline to many who had seen other forms of income disappear, she said.

"The economics of this works," summarized Al Olama. We just need people to understand the potential and to encourage the public and private sector to work together to convince investors.

The role of public-private partnerships

The panelists were united on the need for collaboration between the private and public sectors - and civil society, added Lovett .

The involvement of the private sector is already driving progress in the United States, explained Smith. There are already various initiatives underway to improve connectivity in communities around the country. And it's important that US businesses are encouraged to engage with the public sector.

This is true across the world, explained Tan . As a social enterprise, Grab asks itself how can it work together with other companies and with governments to create products and services that are really needed.

A "unified effort" is needed from the public and private sectors, believes Al Olama.

It's not a question of how one is better than the other, concluded Steiner . It's a question of how one can enable the other.

The World Economic Forum's EDISON Alliance is focused on ensuring everyone across the globe is able to affordably participate in the digital economy. You can read more about it here .

EDISON Alliance: What is the Forum doing to close the digital gap?

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Davos Agenda .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Building trust amid uncertainty – 3 risk experts on the state of the world in 2024

Andrea Willige

March 27, 2024

Why obesity is rising and how we can live healthy lives

Shyam Bishen

March 20, 2024

Global cooperation is stalling – but new trade pacts show collaboration is still possible. Here are 6 to know about

Simon Torkington

March 15, 2024

How messages of hope, diversity and representation are being used to inspire changemakers to act

Miranda Barker

March 7, 2024

AI, leadership, and the art of persuasion – Forum podcasts you should hear this month

Robin Pomeroy

March 1, 2024

This is how AI is impacting – and shaping – the creative industries, according to experts at Davos

Kate Whiting

February 28, 2024

Don’t let the digital divide become ‘the new face of inequality’: UN deputy chief

Facebook Twitter Print Email

Without decisive action by the international community, the digital divide will become “the new face of inequality”, UN Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed warned the General Assembly on Tuesday.

Although technologies such as artificial intelligence and blockchain are opening new frontiers of productivity and providing opportunities to people and societies, they pose numerous risks, she said, including exclusion.

Digital technologies are a game-changer. They are critical to achieving the #GlobalGoals and overcoming #COVID19. Yet, we will not see the full benefits of the digital age if we do not address the #DigitalDivide and ensure equitable digital empowerment for all. pic.twitter.com/NvEHSIuLIu UN GA President UN_PGA April 27, 2021

“Almost half the world’s population, 3.7 billion people, the majority of them women, and most in developing countries, are still offline”, Ms Mohammed told ambassadors, tech experts and representatives from civil society groups.

“Collectively, our task is to help design digital environments that can connect everyone with a positive future. This is why we need a common effort, with collaboration among national and local governments, the private sector, civil society, academia and multilateral organizations.”

A fragmented digital space

Ms Mohammed outlined areas for global cooperation, highlighting the key role the UN has in responding to what she characterized as the growing fragmentation in the digital space.

“Geopolitical fault lines between major powers are emerging, with technology as a leading area of tension and disagreement”, she said. At the same time, tech companies are responding in different ways to issues surrounding privacy, data governance and freedom of expression.

The situation is made worse by the deepening digital divide between developed and developing countries, she added, resulting in global discussions on digital issues becoming less inclusive and representative.

‘Global town hall’ needed

“Now more than ever, we need a global townhall to address these issues and to capitalise on technology’s transformational potential to create new jobs, boost financial inclusion, close the gender gap, spur a green recovery and redesign our cities”, she said.

The UN deputy chief underlined the value of engagement, as achieving universal connectivity cannot be left solely to governments or individual tech companies.

She stressed that no single country or company “should steer the course of our digital future”.

Development depends on connectivity

The General Assembly debate sought to generate political commitments to address the widening digital divide as pandemic recovery efforts align with the push to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by the end of the decade.

“In a world of unparalleled innovation, where our loved ones are but a video call away, billions struggle to access even the most basic elements of connectivity or live with none at all. Truly, for billions of people the pace and scale of sustainable development is reliant upon digital connectivity,” said Volkan Bozkir , the General Assembly President.

He stressed that “now is the time to act” as the digital divide, which existed long before COVID-19 , was only made worse by the crisis. However, recovery offers the chance for true transformation.

“As I have frequently stated, we must use the SDGs as a guide to our post-COVID recovery. This means ensuring that no one is left behind, no one is left offline, and that we apply a whole-of-society, multi-stakeholder, and intergenerational approach to our efforts”, he said.

“This is particularly important for the world’s 1.8 billion young people, who must be equipped with the skills and resources to thrive in an ever-changing, tech-driven future.”

Mr Bozkir called for strengthening implementation of initiatives such as the UN Secretary-General’s Roadmap for Digital Cooperation , launched last June. In addition to achieving universal connectivity, its eight objectives include ensuring human rights are protected in the digital era.

- digital divide

Advertisement

Bridging Digital Divides: a Literature Review and Research Agenda for Information Systems Research

- Published: 06 January 2021

- Volume 25 , pages 955–969, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Polyxeni Vassilakopoulou ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5947-4070 1 &

- Eli Hustad ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1150-1850 1

37k Accesses

72 Citations

9 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Extant literature has increased our understanding of the multifaceted nature of the digital divide, showing that it entails more than access to information and communication resources. Research indicates that digital inequality mirrors to a significant extent offline inequality related to socioeconomic resources. Bridging digital divides is critical for sustainable digitalized societies. Ιn this paper, we present a literature review of Information Systems research on the digital divide within settings with advanced technological infrastructures and economies over the last decade (2010–2020). The review results are organized in a concept matrix mapping contributing factors and measures for crossing the divides. Building on the results, we elaborate a research agenda that proposes [1] extending established models of digital inequalities with new variables and use of theory, [2] critically examining the effects of digital divide interventions, and [3] better linking digital divide research with research on sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Digital transformation: a review, synthesis and opportunities for future research

Swen Nadkarni & Reinhard Prügl

Leverage points for sustainability transformation

David J. Abson, Joern Fischer, … Daniel J. Lang

Digital transformation as an interaction-driven perspective between business, society, and technology

Ziboud Van Veldhoven & Jan Vanthienen

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Digital inequalities have emerged as a growing concern in modern societies. These inequalities relate to disparities in access, actual use and use efficacy of digital resources. Digital resources including transformative technologies, such as business analytics, big data and artificial intelligence are key for the transition of societies towards sustainability (Pappas et al. 2018 ; United Nations 2018 ). Reducing digital inequalities is critical for sustainable digitalized societies. At a high level, all types of digital inequalities are encompassed in the term digital divide . One of the first uses of the term is traced back in a US government report published in 1999 referring to the divide between those with access to new technologies and those without (NTIA 1999 ). The term was soon broadened to signify the “gap between those who can effectively use new information and communication tools, such as the Internet, and those who cannot” (Gunkel 2003 ). Overall, the term digital divide includes digital inequalities between individuals, households, businesses or geographic areas (Pick and Sarkar 2016 ; OECD 2001 ). The conceptual broadness of the term aims to capture a multifaceted economic and civil rights issue in an era of continuous efforts to digitalize society. The ongoing digitalization poses a challenge for individuals who are not fully capable of using digital resources and may feel partially excluded or completely left out of the society.

Extant research has contributed insights on the different aspects of the digital divide phenomenon. In the past, the digital divide literature was mostly driven by policy-oriented reports that focused on access. Nevertheless, scientific research expanded to digital inequalities beyond access. Researchers foregrounded digital inequalities related to knowledge, economic and social resources, attributes of technology such as performance and reliability, and utility realization (DiMaggio et al. 2004 ; Van Dijk 2006 ; Van Deursen and Helsper 2015 ). In technologically and economically advanced settings, digital divides seem to be closing in terms of access, but inequalities that affect people’s ability to make good use of digital resources persist (Lameijer et al. 2017 ; Hsieh et al. 2011 ; Bucea et al. 2020 ). As digitalization becomes increasingly pervasive in work and everyday life, concerns are rising about continuing inequalities within societies that are at the digital forefront. At the same time, in low-resource settings there are still significant access issues. For instance, in the least developed countries (as defined by the United Nations) only 19 per cent of individuals had online access in 2019 while in developed countries, close to 87 per cent of individuals access the internet (Int.Telecom.Union 2019 ). Beyond big differences across settings in terms of access, low-resource settings are tormented by particular political, economic and social conditions inflicting digital divides (Venkatesh et al. 2014 ; Srivastava and Shainesh 2015 ; Luo and Chea 2018 ). Overall, prior research has shown that the modalities of digital inequalities are context-specific and it is important to be explicit about the context when researching the digital divide (Barzilai-Nahon 2006 ). This work is focused on digital divide research within settings with advanced technological infrastructures and economies.

The digital divide is an exemplary sociotechnical phenomenon and has attracted the interest of Information System (IS) researchers. IS research examines more than technologies or social phenomena, or even the two side by side; it investigates emergent sociotechnical phenomena (Lee 2001 ). Hence, IS researchers are well-positioned to study the digital divide phenomenon and have been producing a significant volume of related research. Nevertheless, no systematic review of the IS body of literature on the digital divide exists. Our study identifies, analyses, and integrates a critical mass of recent IS research on the digital divide focused on settings where the technological infrastructures and economies are advanced. To ensure a robust result, we performed a systematic literature review (Kitchenham 2004 ) guided by the following question: What are the key findings identified in extant IS research related to the digital divide in contemporary technologically and economically advanced settings?

Our contribution is threefold. First, we identify recurring digital divide factors for population groups threatened by digital inequalities. The factors identified indicate that digital inequalities frequently mirror offline inequalities (for instance, in terms of socioeconomic resources, knowledge and physical abilities). Second, we present measures proposed in the literature and organize them in three key intervention domains that can contribute to closing the gap (related to policies, training initiatives and tailored design). Finally, as a third contribution, we identify areas for future research providing a research agenda.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. First, we present the method used for selecting and analyzing the articles for this review. Then, we offer a synthesis of our findings related to digital divide factors and related measures and present them in a concise concept matrix. We continue by discussing the implications for further research and we end with overall concluding remarks.

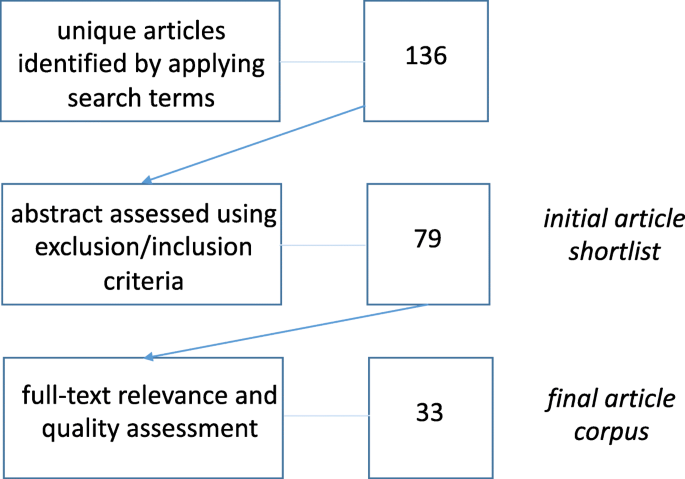

The literature review is conceptual providing a synthesis of prior research and identifying areas for future research (Ortiz de Guinea and Paré 2017 ; Schryen et al. 2015 ). It includes research published during the last decade (2010–2020). The approach followed is based on the three-step structured literature review process proposed by Kitchenham ( 2004 ). Specifically, the three-step process includes: (a) planning the review, where a detailed protocol containing specific search terms and inclusion/exclusion criteria is developed, (b) conducting the review, where the identification, selection, quality appraisal, examination and synthesis of prior published research is performed and (c) reporting the review, where the write-up is prepared. We used these steps as our methodological framework. In addition, we utilized principles suggested by Webster and Watson ( 2002 ) for sorting the articles included in the review. Following these principles, we identified key concepts and created a concept-centric matrix that provides an overview of the literature reviewed.

To identify articles to be reviewed, we searched for “Digital” and “Divide” in the abstract, title or keywords within published Information Systems research. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to reduce selection bias, guarantee the quality of the papers selected and increase the review validity. Peer-reviewed, empirical papers, written in English were included. Conceptual papers that lack empirical evidence and papers focusing on the digital divide in developing countries were excluded. Figure 1 provides an overview of the selection process. To ensure a good coverage of Information Systems research we searched within the eight top journals in the field i.e. the basket of eight (AIS 2019 ). The journals included in the basket are: European Journal of Information Systems, Information Systems Journal, Information Systems Research, Journal of AIS, Journal of Information Technology, Journal of MIS, Journal of Strategic Information Systems and MIS Quarterly. Additionally, we searched within the journal Communications of the Association for Information Systems (CAIS) which has a key role within the IS research community communicating swiftly novel, original research. We also included in our search the journal Information Technology (IT) & People because it focuses on IS research that explores the interplay between technology individuals and society and the journal Information Systems Frontiers because it covers behavioural perspectives on IS research. Both journals are high quality IS outlets especially relevant for research on the digital divide. Furthermore, we included in our search the conferences of the Association of Information Systems (ICIS, ECIS; AMCIS; PACIS) and the Hawaiian International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS). We utilized Scopus as our search engine.

The literature selection process

In Scopus, we searched for papers from the selected journals and conferences excluding books, book chapters, commentaries, letters and short surveys. For the journal article search, the ISSNs of the selected journals were used for filtering the search results in Scopus. In total, 45 journal papers were identified. For the conference article search, the conference names were used in Scopus and 91 conference papers were identified. Overall, the search yielded 136 unique articles in total. The next step was to read the titles and abstracts of the articles identified checking their relevance to the research question. For this step, the exclusion criteria were used. Specifically, we excluded papers that only casually mentioned the digital divide but had a different focus, literature reviews and conceptual papers and papers focused on developing countries. After this step, 79 articles were shortlisted. The full text of each of the shortlisted articles was assessed for relevance applying the inclusion-exclusion criteria to the full content. Additionally, the quality of the research reported was assessed. For the quality assessment, each article´s method description was first checked. At this stage, conference papers reporting early stages of ongoing research were removed. In several cases of conference papers that were removed, we found that more mature and extensive results from the same studies were reported in journal articles that were already included in our shortlist and were published after the conference papers. After this step, a final corpus of 33 articles was defined (Table 1 ). A detailed overview of the reviewed articles is included in an electronic supplementary file that can be accessed in the journal´s web site (see Online Resource 1 ).

After selecting the papers, we analyzed their content. We started with extracting meta-data of the papers such as type of study, year of study, study context, research method and theoretical framework applied. In addition, we identified the study subjects for each paper distinguishing between papers that engage with the general population, or specific groups of people including the elderly and marginalized population groups (e.g. refugees, migrants). We continued with an intra-analysis of the content of the papers by looking for core themes in each paper. The themes that were identified for each paper were registered, and as a next step, we performed an inter-analysis and comparison across papers. Based on the comparison, recurring themes and patterns across the papers were discovered and further categorized. The outcomes of the papers´analysis are presented in the " Results " section that follows.

This section presents the key findings from the literature reviewed. First, we present the theoretical premises and the methodological approaches of extant publications on the Digital Divide within IS research and their evolution from 2010 to 2020. Table 2 provides an overview of the theories and concepts, methods and data sources in the literature reviewed. Then, recurring digital divide factors are presented for population segments that are particularly digitally challenged (the elderly and marginalized population groups) and also, for the general population. Finally, measures for addressing the digital divide are presented and organized in three key intervention domains (policy measures, education/training and design tailoring). The section also includes a concept matrix which provides an overview of digital divide factors and related measures identified in the literature reviewed (Table 3 ).

3.1 Trends, Methods and Theoretical Frames in IS Research on the Digital Divide

The work of Information Systems´ researchers on the digital divide has been influenced by policy-oriented reports that tend to be based on macro-level analyses. This influence is clear in the first half of the 2010–2020 period while in the second half, research extends towards a more complex and contextualized picture of digital divides. Newer papers tend to ask a wider range of questions related to access and use of information technologies and investigate a greater variety of factors. For instance, skill related factors are explored in about half of both earlier and later studies, but, newer studies tend to additionally explore motivation and personality aspects (about half of the newer studies include such aspects). Interestingly, several of the newer papers only focus on technology use. In these papers, researchers explore the second order digital divide and the extent of inclusion or involuntary exclusion of those that already have access to technologies. Furthermore, most earlier papers tend to investigate the general population while the majority of newer studies focus on specific population groups.

Overall, most of the studies employ quantitative research methods utilizing well-established survey instruments adapted for studying digital inequalities for certain groups (e.g. older adults) or re-using existing data sets from organizations like the International Telecommunication Union, the World Bank and the United Nations. A few studies use a mixed-method approach combining interviews with survey data, while the rest employ qualitative approaches. Well-known technology acceptance models such as TAM (Technology Acceptance Model), UTAUT (Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology) and MATH (Model of Adoption of Technology in Households) and theories on motivation and human behavior have been used to explore the digital divide. Typical variables included in the investigations are self-efficacy, performance and effort expectancy. Furthermore, social cognitive theories, social support theories and social capital conceptualizations have been used while some of the papers utilize selectively digital divide conceptualizations combined with constructs from social, sociotechnical or economic research.

3.2 Factors Contributing to the Digital Divide

The digital divide is often characterized as a digital divide cascade which is nuanced into different types of inequalities including unequal capabilities, engagement, and use outcomes in addition to inequalities of access and use. This points to the importance of identifying and aiming to remedy inequalities in what people are actually able to do and achieve with digital technologies (Burtch and Chan 2019 ; Díaz Andrade and Doolin 2016 ). In settings with advanced infrastructures and economy, physical access is not a key source of digital inequalities and IS studies that examine issues of unequal access show that access gaps are closing with the exception of marginalized population groups. Nevertheless, there is still a stark difference between access (first-order divide) and actual use (second-order divide) (Bucea et al. 2020 ). The latter relates to differences in digital skills, autonomy, social support and the aims of digital technology use (Rockmann et al. 2018 ). Going beyond socioeconomic demographics, additional personal contributing factors have been identified in the literature related to: (a) motivation, (b) personality traits (e.g. openness, extraversion, conscientiousness), (c) digital skills. Many of the studies reviewed focus on the elderly who are also referred to as “digital immigrants” (as opposed to digital natives that have been interacting with digital technology since childhood). Additionally, several studies focus on marginalized population groups. In the paragraphs that follow, we present research findings organizing them according to the different groups studied.

Elderly Population

Although digital technologies have been around for several decades, some of the elderly members of society have difficulties familiarizing with and adopting digital tools and services. Nevertheless, although a decade ago age-related underutilization of IT was significant (Niehaves and Plattfaut 2010 ), over the years, information and communication technologies (ICTs) have been gradually better integrated in the lives of elderly adults. A recent study on the digital divide related to mobile phone use among old adults in UK found that more than 70% have adopted smartphones (Choudrie et al. 2018 ). Specifically, research findings indicate that older adults frequently use internet-related smartphone features such as emailing and browsing although only very few use smartphones to access public services such as the National Health Service. One potential reason for the limited use of specialized web-based services among the elderly despite the wide adoption of smartphones, is that their former workplaces may have been characterized by low IT intensity causing a lower exploratory IT behavior when seniors are retiring (Rockmann et al. 2018 ). Niehaves and Plattfaut ( 2014 ) used the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) and the model of adoption of technology in households (MATH) to explain internet acceptance and usage by the elderly. Performance expectancy was found to be the main use driver among senior citizens. These models were able to predict how the elderly could be encouraged to learn to use digital technologies.

When asked, the elderly themselves identified several key impeding factors for their digital involvement: fear and anxiety of using digital technology and services, negative attitude, a sense of feeling too old for learning, lack of knowledge, difficulties understanding digital terminology (Holgersson and Söderström 2019 ). Family support is key for developing mobile internet skill literacy and mobile internet information literacy among older adults (Xiong and Zuo 2019 ). Seniors become better positioned to take advantage of digital resources when they have cognitive and emotional support. Cognitive support from family facilitates learning and digital skills´ development, and also, the development of skills for judging, analyzing and selecting information (Xiong and Zuo 2019 ). Emotional support based on patience, praise, encouragement and comfort can help the elderly avoid computer anxiety and stress (Xiong and Zuo 2019 ). Emotional support is important because unwillingness to adopt advanced digital services by the elderly was found to stem from mistrust, high-risk perceptions, and privacy concerns (Fox and Connolly 2018 ).

Overall, older people are a heterogeneous group, and it is important not to overlook their differences in digital skills and digital practice. Klier and colleagues conducted a survey on older unemployed individulas in Germany and showed that they can be grouped into four different types of digital media users ranging from very active users (digital contributors) to sceptics with limited or no use (digital sceptics) characterised by their negative attitude towards digital media (Klier et al. 2020 ). Digitalization efforts should take into account “the various shades of grey in older adults’ ability to draw on IT-based innovations” (Lameijer et al. 2017 , p. 6).

Marginalized Population Groups

Language barriers as for instance, in the case of refugees and immigrants, and practical resource limitations as in the case of distressed urban areas and remote rural areas can cause social exclusion and hinder the process of digital technologies´ assimilation throughout society. Several researchers have studied specifically issues related to the digital divide within marginalized population groups. Alam and Imram ( 2015 ) found in their research that although refugees and immigrants in the US are motivated to learn about new technology, many are not able to do so because of unaffordable cost, language barriers and lack of skills. Refugees and immigrants realize that technology is helpful for finding new jobs or facilitating social engagement. Digital technologies are of particular value to refugees for multiple reasons: to participate in an information society; to communicate effectively; to understand a new society; to be socially connected; to express their cultural identities (Díaz Andrade and Doolin 2016 ). A study on mobile communications by labor migrants (Aricat 2015 ) showed that mobile phones may also facilitate the development of ghettos and the lack of integration in the new countries by easing communications between the migrants and their home countries. The study identified a visible divide in the framing of the prospects and potentialities of mobile phones related to acculturation.

Enhancing the relationship between citizens and government through digital services requires reaching out to individuals and communities on the unfortunate side of the divide. Digital technology access and use in the context of e-government services were explored within one of the most distressed cities in the US (Sipior et al. 2011 ). This study showed that socioeconomic characteristics (educational level and household income) have significant impact on access barriers, but they also found that employment plays a critical role and is associated both with perceived access barriers and with perceived ease of use. A study conducted among governmental participants representing rural communities in Australia suggests that rural digital exclusion can result from three intertwined layers: availability (elements of infrastructure and connectivity), adoption, and digital engagement (Park et al. 2015 ). Among these layers, availability is probably not as important as one could expect. Similarly, one large household study conducted across the US found that the availability of Internet Supply Providers (ISP) had little impact on Internet adoption, and that Internet adoption can almost exclusively be attached to differences in household attributes and not to ISP availability (Ma and Huang 2015 ).

As access gaps are closing in settings with advanced infrastructures and economy, those who do not have access are easily overlooked (Davis et al. 2020 ). Nevertheless, the first-level digital divide still requires attention for marginalized population groups. Furthermore, socioeconomic factors that were found to affect uptake more than two decades ago (for instance, education level and income) are still relevant in today’s context for particular segments of our societies. Contrary to traditional views, the availability of digital solutions does not always facilitate the resolution of long-standing problems for those that are less well-off in our societies (for instance, immigrants or financially troubled individuals). What people are actually able to do and achieve with digital technologies relates to their greater positioning in society (Burtch and Chan 2019 ) and affects their potential for improvement. As digital technologies are becoming indispensable for participating in the economy and engaging in society, sustained digital divides amplify marginalization.

General Population

A study by Pick and colleagues ( 2018 ) showed the positive influence of managerial/science/arts occupations, innovation, and social capital on the use of digital technologies (Pick et al. 2018 ). Nevertheless, unreasonably high expectations are found to have a negative impact on ICT acceptance (Ebermann et al. 2016 ). Findings from a study conducted within White and Hispanic-owned SMEs in the US (Middleton and Chambers 2010 ) indicate some level of inequality related to ethnicity and age (younger white SME owners being better positioned). Davis and colleagues (Davis et al. 2020 ) analyzed the influence of income, income distribution, education levels, and ethnicity on levels of access to Internet in the US. The findings show that low levels of education and levels of income below the poverty line still tend to lead to higher proportion of people with no Internet access (Davis et al. 2020 ). Even when individuals do have equal access to digital technologies, differences in skills can lead to digital inequalities (Burtch and Chan 2019 ). Taking a differentiated view on skills is needed to understand technology use and no-use (Reinartz et al. 2018 ). Physical skills matter; users with disabilities can be digitally disadvantaged and despite the benefits promised by specialized assistive technologies their adoption rate falls short of expectations (Pethig and Kroenung 2019 ).

Some groups may be challenged because they are too far embedded in older systems, which makes it difficult for them to adopt newer ICTs (Abdelfattah 2012 ). Social capital can trigger ICT awareness changing individual dispositions, thus converting social capital into cultural capital (Reinartz et al. 2018 ). An interesting study on crowdfunding showed that the benefits of medical crowdfunding accrue systematically less to racial minorities and less educated population segments (Burtch and Chan 2019 ). One of the reasons for this is the communication-rich nature of the context: less educated persons are not always capable of producing polished, persuasive pitches to solicit funds. Furthermore, digital inequality manifests on the efficacy of using crowdfunding platforms, due to a lack of critical mass in the number of potential transaction partners (donors). The results show the importance of looking beyond access or connectivity to investigate efficacy (in this case, expressed as success in fundraising), and how it associates with different population segments (Burtch and Chan 2019 ).

At the country level, a number of studies examined socio-economic influences on access and use of particular forms of technologies as for instance, personal computers and broadband internet (Zhao et al. 2014 ; Pick and Azari 2011 ; Dewan et al. 2010 ). A world-wide study found complementarities in the diffusion of PCs and the Internet leading to narrower digital divides (Dewan et al. 2010 ). These findings challenge the dominant understanding of characteristics such as country wealth, education levels and telecommunications infrastructure leading to the widening of the digital divide. Country-level studies are based on the analysis of data from census surveys, national statistics, and datasets from organizations like UNDP and ITO. The use of such datasets is helpful for performing comparisons across countries but due to the generic nature of data the purpose of digital technology use has been scarcely examined in country-level studies. This may be attributed to the fact that comparable data on specific online activities are not easy to collect across countries (Zhao et al. 2014 ). A study conducted by Bucea and colleagues ( 2020 ), is an exception to this. The study assessed specifically the use of e-Services and Social Networks within the 28 member-states of the European Union analyzing four socio-demographic factors (age, education, gender, and income). The findings showed that for e-Services, disparities relate mostly to education while for Social Networks age is the most important factor (Bucea et al. 2020 ). Overall, country level studies are important for assessing disparities across countries and can lead to the identification of factors reinforcing inequalities. At the same time, macro studies can not bring insights about digital inequalities across different population segments within countries.

3.3 Overcoming Digital Divides

Policy-making is considered instrumental for closing the digital gap and a mix of policy measures has been suggested in prior research. In general, policy initiatives can include subsidies targeting specific digitally disadvantaged segments as for instance rural populations (Talukdar and Gauri 2011 ). For instance, governments can apply strong intervention policies to provide equitable ICT access also in rural areas (Park et al. 2015 ). Furthermore, digital divides may be addressed at scale by crafting policies to equip underprivileged groups with better communication skills (reading, writing, and software use) enabling meaningful engagement with digital platforms (Burtch and Chan 2019 ). Government policy makers can collaborate with schools to support students from low-income households through the provision of home computers aiming to reduce the effect of socio-economic inequalities among students (Wei et al. 2011 ). Policies raising the priority of IT, protecting property rights, and enhancing freedom of the press and openness, can help to stimulate educational advances, labor-force participation and income growth, all of which contribute to advancing technology use (Pick and Azari 2011 ). Policy measures should allow room for local adaptations, as contextual and local elements seem to play a role for technology users and could influence policy success (Racherla and Mandviwalla 2013 ). Effective evaluation mechanisms make it easier to develop new policies addressing digital divides (Chang et al. 2012 ) helping policy-makers to refine initiatives targeting certain segments of society, such as elderly people and socio-economically disadvantaged groups (Hsieh et al. 2011 ).

Contemporary workplaces can help by taking greater responsibility for IT education of their employees even when they are close to retirement. Developing the digital skills of seniors while they are still employed is important for preventing digital exclusion after retirement (Rockmann et al. 2018 ). Overall, employment has a pivotal role in explaining citizen usage of e-government initiatives (Sipior et al. 2011 ). As an employee, an individual may have access to the Internet at the place of employment. Furthermore, employment demands may increase the confidence of an individual in performing new tasks. Thinking beyond workplaces, policies that leverage existing communities, social structures, and local actors can also help in reducing digital inequalities (Racherla and Mandviwalla 2013 ). Such policies can stimulate public/private partnerships with grassroots organizations that already have “hooks” in local communities. Moreover, long-term government policies could set a goal of encouraging growth in social capital within communities (Pick et al. 2018 ).

Proper training and education can help mitigate digital inequalities (Van Dijk 2012 ). For instance, platform operators can provide coaching services for underprivileged populations (Burtch and Chan 2019 ). Furthermore, information campaigns also have a significant role to play, digital divides may be narrowed if vendors engage in trust-building campaigns (Fox and Connolly 2018 ). Integrating digital education into curricula can also contribute to reducing digital inequalities (Reinartz et al. 2018 ), and education campaigns can stimulate the adoption and usage of ICTs bridging rural-urban digital gaps. Rural communities typically lag in digital skills, and digital literacy training programs can improve digital engagement in rural communities. Digital literacy programs targeting senior citizens can help them develop the necessary skills and abilities to use digital mobile devices so that they could be part of the Digital Society (Carvalho et al. 2018 ; Fox and Connolly 2018 ; Klier et al. 2020 ). Educational efforts for the elderly must be practically oriented in order to show directly what is to be gained by becoming more digital (Holgersson and Söderström 2019 ). In addition, social networks, friends and family are important for supporting the training of disadvantaged people in technologies; family emotional and cognitive support can increase the elderly’s digital capabilities, reduce computer anxiety and increase trust and motivation for learning (Xiong and Zuo 2019 ).

The design and development of ICT solutions should take into account individual differences for creating proper stimuli to different user groups. For instance, the use of governmental e-services can be improved by making them more engaging, interactive, and personal to address a country’s or region’s cultural norms (Zhao et al. 2014 ). This makes the role of appropriate design for overcoming the digital divide a center of attention. Lameijer et al. ( 2017 ) propose that design-related issues should be considered and evaluated to better understand technology adoption patterns among elderly. Also, the study by Klier and colleagues showed that there is a potential to shift older individuals towards a more active engagement with digital media by ensuring ease of use in the design of digital services (Klier et al. 2020 ). Furthermore, the needs of groups with disabilities ought to be taken into account when designing information systems for the general public (Pethig and Kroenung 2019 ). It is important to integrate assistive functionalities in general IS to emphasize authentic inclusiveness. Overall, research points to the importance of functionalities that suit the needs of specific user groups to stimulate the use of digital technologies.

4 Crossing Digital Divides: a Research Agenda

The evolution of IS research on the digital divide during the last decade shows the richness of this research area. As digitalization becomes pervasive in our societies, digital inequalities emerge in different contexts and communities renewing the interest on digital divide research. In recent years, researchers have been shifting away from macro-level studies and are re-orienting towards developing nuanced and contextualized insights about digital inequalities. The analysis of published research allows the identification of gaps and opportunities for further research. Furthermore, there are specific research directions proposed in several of the reviewed papers. The synthesis of suggestions from the papers reviewed with the results of our analysis led to the identification of three research avenues that bring exciting opportunities for researchers to engage with topics that are highly relevant with our digitalization era. Specifically, we suggest a research agenda that proposes: [1] extending established digital divide models with new variables and use of theory, [2] examining the effects of interventions, and [3] addressing societal challenges and especially sustainability goals through the lens of digital divide. Social inclusion and digital equality are crucial for a sustainable digitalized society.

4.1 Avenue I: Extending Established Digital Divide Models and Use of Theory

Extant research shows that physical access divides are being reduced in technologically and economically advanced societies but, inequalities in use persist (Hsieh et al. 2011 ; Lameijer et al. 2017 ). These use inequalities are found to be related to socioeconomic characteristics and also, personality traits, motivation and digital skills. A better understanding of the complex phenomenon of digital divide is needed combining multiple aspects to form comprehensive models (Choudrie et al. 2018 ) and further explore the concept itself to get more explanatory power (Lameijer et al. 2017 ). The emphasis, to date, has been on describing the digital divide by identifying gaps between actual technology access and use against an ideal situation. Work should be undertaken to investigate different national, social and cultural settings (Niehaves and Plattfaut 2010 ) across geographical contexts (Niehaves and Plattfaut 2014 ) and the influence of institutional and environmental factors on individuals’ ability and motivation to access and use technology (Racherla and Mandviwalla 2013 ). Furthermore, researchers may explore the values and interests of those abstraining from the use of digital resources and the implications of the overemphasis to digital inclusion (Díaz Andrade and Techatassanasoontorn 2020 ).

Further research is also needed to extend established models with new variables. Future investigations may add variables related to social theories (Abdelfattah et al. 2010 ; Hsieh et al. 2011 ; Niehaves and Plattfaut 2014 ), personal traits models (Ebermann et al. 2016 ), and capital theory (Hsieh et al. 2011 ; Reinartz et al. 2018 ). Additionally, future research should consider testing psychological variables (Niehaves and Plattfaut 2010 ) and additional socio-economical aspects (Hsieh et al. 2011 ; Reisdorf and Rikard 2018 ) including support from friends and family (Xiong and Zuo 2019 ; Holgersson and Söderström 2019 ) to develop a more fine-grained understanding of the association between the digital divide phenomenon and contributing variables (Hsieh et al. 2011 ; Niehaves and Plattfaut 2014 ; Fox and Connolly 2018 ). Qualitative research is important for revealing factors that influence inequalities and can become the basis for model building and testing using quantitative data.

Interestingly, fully developed theoretical frameworks that have been extensively used in other streams of exploratory information systems research related to the introduction and use of ICTs were not present in the papers reviewed. For instance, Activity theory and Institutional theory can be used as lenses for understanding and analyzing the digital divide phenomenon. Activity theory (Allen et al. 2011 ; Engeström 1999 ) can help in developing a nuanced understanding of the relationship between ICT artifacts and purposeful individuals taking into account the environment, culture, motivations, and complexity of real-life settings. Institutional theory (Jepperson 1991 ; Scott 2005 ) can contribute to developing insights related to societal structures, norms and routines shifting attention to units of analysis that cannot be reduced to individuals’ attributes or motives. Overall, we observed that digital divide research could benefit from better leveraging theory to extend established digital divide models.

4.2 Avenue II: Examining the Effects of Interventions to Cross the Digital Divide

Measures for crossing digital divides include policy interventions, training and design. Information Systems research can be especially relevant by developing design knowledge for the development and deployment of digital technology artifacts in different settings. Although several measures are proposed in the literature, further work is required to research the effect of interventions to avoid the exclusion of citizens from the digital realm addressing inequalities (Alam and Imran 2015 ; Reisdorf and Rikard 2018 ; Reinartz et al. 2018 ). In particular, appropriate design approaches for digital technologies should be investigated and tested to avoid involuntary exclusion of marginalized groups, elderly people or any other group of individuals affected by digital inequalities (Rockmann et al. 2018 ; Lameijer et al. 2017 ; Alam and Imran 2015 ; Fox and Connolly 2018 ). Additionally, comparative research can be undertaken investigating the effects and attractiveness of different design solutions in different cultural settings (Pethig and Kroenung 2019 ). Overall, although many studies include insights related to measures for bridging digital divides, there is a clear need for studies with a longitudinal research design to investigate the impact of measures over time. Interestingly, little research has been performed up to now on the potentially negative unexpected effects of measures for bridging digital divides (Díaz Andrade and Techatassanasoontorn 2020 ). This is certainly an area that needs to be further developed. The use of technologies might lead to advantages or disadvantages, which are unevenly distributed in society. Focusing only on benefits, researchers miss the opportunity to connect to emerging literature on the dark side of Internet and unexpected outcomes of digitalization including privacy risks. Scholars of information systems can develop novel avenues of critical thinking on the effects of interventions to cross the digital divide.

4.3 Avenue III: Linking Digital Divide Research With Research on Sustainability

There were no studies in our literature review that focused specifically on sustainability topics, and future research should pay attention to this gap. The United Nations´ sustainability goals focus on reducing inequality within and among countries to avoid biased economic development, social exclusion, and environmentally untenable practices. Important dimensions of sustainable development are human rights and social inclusion, shared responsibilities and opportunities (United Nations 2020 ). An essential part of social inclusion in our societies is e-inclusion (Pentzaropoulos and Tsiougou 2014 ). At the same time, it is important to research the risks and ethical implications of depriving individuals from offline choices (Díaz Andrade and Techatassanasoontorn 2020 ). Furthermore, we need to support sustainability in rural areas reducing the urban - rural digital divide. Sustainability researchers have identified the issue pointing to the vulnerabilities of rural communities that are in particular need of bridging inequalities (Onitsuka 2019 ). Future empirical studies on the digital divide should therefore pay attention to sustainability topics in terms of social exclusion and digital inequality to better understand underlying factors and potential remedies.

The covid-19 pandemic made digital inequalities even more evident. In periods of social distancing to minimize infection risks, individuals sustain their connections with colleagues, friends, and family through online connections. Furthermore, people need digital skills to keep updated on crucial information and to continue working when possible using home offices and digital connections. In addition, recent crisis response experiences have shown that switching to digital education may lead to exclusion of the few that cannot afford physical digital tools (Desrosiers 2020 ), or do not have access to sustainable infrastructures and ICT access. This crisis has shown that digital divides can become a great challenge aggravating inequalities experienced by marginalized communities such as urban poor and under-resourced businesses. Digital inequalities are a major factor of health-related and socio-economical vulnerability (Beaunoyer et al. 2020 ).

The role of Information Systems researchers is critical for the development of digital capital contributing to sustainable development. Digital capital refers to the resources that can be utilized by communities including digital technology ecosystems and related digital literacy and skills. General policy measures related to stimulating regional economic growth, strengthening tertiary education, or discouraging early leaving from education can be developed by scientists in other domains. However, thinking about inclusive configurations of digital infrastructures and ecosystems and developing related design principles entails specialized knowledge from the Information Systems domain. Furthermore, Information Systems researchers can provide insights about the development of capabilities required for leveraging digital resources such as digital infrastructures (Hustad and Olsen 2020 ; Grisot and Vassilakopoulou 2017 ), big data and business analytics (Mikalef et al. 2020 ). Innovative approaches for leveraging digital resources will be pivotal for addressing grand challenges related to poverty, healthcare and climate change. Information Systems researchers can contribute insights for bridging digital divides to promote an agenda towards a sustainable future.

5 Conclusions

The present work takes stock of Information Systems research on the digital divide by synthesizing insights from publications in the 2010–2020 period. The review process was performed with rigor while selecting and critically assessing earlier research. Nevertheless, this work is not without limitations. We have confined the literature search within one specific discipline (Information Systems research). This limits the breadth of the review but facilitates comprehensiveness and depth in the development of insights about the body of literature analyzed. Furthermore, focusing on Information Systems research facilitates the development of a research agenda that is relevant to the target discipline through the identification of gaps and extrapolations from previous work.

The review showed that within digital divide research, the attention of Information Systems research has gradually shifted from access to use and now needs to shift further towards better understanding use outcomes. Digital inequalities are a serious threat to civil society in an era where societies are rapidly going digital. For instance, daily activities such as paying bills, filling in application forms, filing tax returns, are all expected to be carried out electronically. There are high expectations for active citizens´ role based on online services (Axelsson et al. 2013 ; Vassilakopoulou et al. 2016 ); hence, we need to be concerned of digital inequalities ensuring fairness and inclusiveness. Furthermore, digital resources such as big data and business analytics are key enablers of sustainable value creation within societies (Pappas et al. 2018 ; Mikalef et al. 2020 ). Bridging digital divides is critical for sustainable digitalized societies. The findings of this literature review can provide a foundation for further research and a basis for researchers to orient themselves and position their own work.

Abdelfattah, B. M. (2012). Individual-multinational study of internet use: the digital divide explained by displacement hypothesis and knowledge-gap hypothesis. In AMCIS 2012 Proceedings . 24. https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2012/proceedings/AdoptionDiffusionIT/24 .

Abdelfattah, B. M., Bagchi, K., Udo, G., & Kirs, P. (2010). Understanding the internet digital divide: an exploratory multi-nation individual-level analysis. In AMCIS 2010 Proceedings . 542. https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2010/542 .

AIS (2019). Association for information systems. Senior scholars’ basket of journals . https://aisnet.org/page/SeniorScholarBasket . Accessed 10 Jan 2019.

Alam, K., & Imran, S. (2015). The digital divide and social inclusion among refugee migrants: A case in regional Australia. Information Technology & People, 28 (2), 344–365.

Article Google Scholar

Allen, D., Karanasios, S., & Slavova, M. (2011). Working with activity theory: Context, technology, and information behavior. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62 (4), 776–788.

Aricat, R. G. (2015). Is (the study of) mobile phones old wine in a new bottle? A polemic on communication-based acculturation research. Information Technology & People, 28 (4), 806–824.

Axelsson, K., Melin, U., & Lindgren, I. (2013). Public e-services for agency efficiency and citizen benefit—Findings from a stakeholder centered analysis. Government Information Quarterly, 30 (1), 10–22.

Barzilai-Nahon, K. (2006). Gaps and bits: Conceptualizing measurements for digital divide/s. The Information Society, 22 (5), 269–278.

Beaunoyer, E., Dupéré, S., & Guitton, M. J. (2020). COVID-19 and digital inequalities: Reciprocal impacts and mitigation strategies. Computers in Human Behavior, 111 , 106424.

Bucea, A. E., Cruz-Jesus, F., Oliveira, T., & Coelho, P. S. (2020). Assessing the role of age, education, gender and income on the digital divide: evidence for the European Union. Information Systems Frontiers . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-020-10012-9 .

Burtch, G., & Chan, J. (2019). Investigating the relationship between medical crowdfunding and personal bankruptcy in the United States: evidence of a digital divide. MIS Quarterly, 43 (1), 237–262.

Carvalho, C. V. d., Olivares, P. C., Roa, J. M., Wanka, A., & Kolland, F. (2018). Digital information access for ageing persons. In ICALT 2018 Proceedings the 8th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies, IEEE, 345–347.

Chang, S.-I., Yen, D. C., Chang, I.-C., & Chou, J.-C. (2012). Study of the digital divide evaluation model for government agencies–a Taiwanese local government’s perspective. Information Systems Frontiers, 14 (3), 693–709.

Choudrie, J., Pheeraphuttranghkoon, S., & Davari, S. (2018). The digital divide and older adult population adoption, use and diffusion of mobile phones: a quantitative study. Information Systems Frontiers, 22 , 673–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-018-9875-2 .

Davis, J. G., Kuan, K. K., & Poon, S. (2020). Digital exclusion and divide in the United States: exploratory empirical analysis of contributing factors. In AMCIS 2020 Proceedings . 1. Fully Online Event. https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2020/social_inclusion/social_inclusion/ .

Desrosiers, M.-E. (2020). As universities move classes online, let’s not forget the digital divide, Policy Options Politiques . https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/march-2020/as-universities-move-classes-online-lets-not-forget-the-digital-divide/ . Accessed 25 Mar 2020.

Dewan, S., Ganley, D., & Kraemer, K. L. (2010). Complementarities in the diffusion of personal computers and the Internet: Implications for the global digital divide. Information Systems Research, 21 (4), 925–940.

Díaz Andrade, A., & Doolin, B. (2016). Information and communication technology and the social inclusion of refugees. MIS Quarterly, 40 (2), 405–416.

Díaz Andrade, A., & Techatassanasoontorn, A. A. (2020). Digital enforcement: Rethinking the pursuit of a digitally-enabled society. Information Systems Journal, 12306 , 1–14.

Google Scholar

DiMaggio, P., Hargittai, E., Celeste, C., & Shafer, S. (2004). Digital inequality: From unequal access to differentiated use. In Social inequality (pp. 355–400). New YorK: Russell Sage Foundation.

Ebermann, C., Piccinini, E., Brauer, B., Busse, S., & Kolbe, L. (2016). The impact of gamification-induced emotions on In-car IS adoption - the difference between digital natives and digital immigrants. In 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS 2016) Proceedings, IEEE, 1338–1347.

Engeström, Y. (1999). Activity theory and individual and social transformation. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, & R. L. Punamäki (Eds.), Perspectives on activity theory (Vol. 19, pp. 19–37). Cambridge: Camebridge University Press.

Fox, G., & Connolly, R. (2018). Mobile health technology adoption across generations: Narrowing the digital divide. Information Systems Journal, 28 (6), 995–1019.

Grisot, M., & Vassilakopoulou, P. (2017). Re-infrastructuring for eHealth: Dealing with turns in infrastructure development. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 26 (1), 7–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-017-9264-2 .

Gunkel, D. J. (2003). Second thoughts: toward a critique of the digital divide. New Media & Society, 5 (4), 499–522.

Holgersson, J., & Söderström, E. (2019). Bridging the gap - Exploring elderly citizens’ perceptions of digital exclusion. In ECIS 2019 Proceedings. https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2019_rp/28 .

Hsieh, J. J., Rai, A., & Keil, M. (2011). Addressing digital inequality for the socioeconomically disadvantaged through government initiatives: Forms of capital that affect ICT utilization. Information Systems Research, 22 (2), 233–253.

Hustad, E., & Olsen, D. H. (2020). Creating a sustainable digital infrastructure: the role of service-oriented architecture. Presented at the Centeris conference 2020, forthcoming in Procedia Computer Science , preprint available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346989191_Creating_a_sustainable_digital_infrastructure_The_role_of_service-oriented_architecture .

Int.Telecom.Union (2019). Facts and figs. 2019: measuring digital development. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/FactsFigures2019.pdf . Accessed 25 Apr 2020.

Jepperson, R. L. (1991). Institutions, institutional effects, and institutionalism. In W. W. Powell, & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 143–163). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kitchenham, B. (2004). Procedures for performing systematic reviews. Keele University Technical Report, UK, TR/SE-0401, 1–26.

Klier, J., Klier, M., Schäfer-Siebert, K., & Sigler, I. (2020). #Jobless #Older #Digital – Digital media user of the older unemployed. In ECIS 2020 Proceedings . Fully Online Event. https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2020_rp/206 .

Lameijer, C. S., Mueller, B., & Hage, E. (2017). Towards rethinking the digital divide–recognizing shades of grey in older adults’ digital inclusion. In ICIS 2017 Proceedings . 11. http://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2017/General/Presentations/11 .

Lee, A. S. (2001). Editor’s comments: What are the best MIS programs in US business schools? MIS Quarterly, 25 (3), iii–vii.

Luo, M. M., & Chea, S. (2018). Internet village motoman project in rural Cambodia: bridging the digital divide. Information Technology & People, 21 (1), 2–20.

Ma, J., & Huang, Q. (2015). Does better Internet access lead to more adoption? A new empirical study using household relocation. Information Systems Frontiers, 17 (5), 1097–1110.

Middleton, K. L., & Chambers, V. (2010). Approaching digital equity: is wifi the new leveler? Information Technology & People, 23 (1), 4–22.

Mikalef, P., Pappas, I. O., Krogstie, J., & Pavlou, P. A. (2020). Big data and business analytics: A research agenda for realizing business value. Information & Management, 57 (1), 103237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2019.103237 .

NTIA. (1999). Falling through the net: Defining the digital divide. A report on the telecommunications and information technology gap in America. National Telecommunications and Information Administration . https://www.ntia.doc.gov/legacy/ntiahome/fttn99/contents.html . Accessed 20 Oct 2019.

Niehaves, B., & Plattfaut, R. (2014). Internet adoption by the elderly: employing IS technology acceptance theories for understanding the age-related digital divide. European Journal of Information Systems, 23 (6), 708–726.